Method of Citation

All references to Heidegger’s writings are to the standard edition of Being and Time (Sein und Zeit) or to the respective volume of the Complete Edition (Gesamtausgabe) of his writings. References to Sein und Zeit are cited as “SZ” followed by the page number, for example, “SZ: 15”; references to volumes of the Gesamtausgabe are cited as “GA” followed by the volume number, colon, and page number, for example, “GA55: 19.” Most English translations include the pagination of the German original, making it possible to dispense with citing the translations’ pagination. Any exceptions are flagged in footnotes, in which case the German pagination is given followed by a slash and the pagination of the English translation, for example, “Reference von HerrmannGA9: 106/84.” A full list of these primary texts can be found at the beginning of the References section.

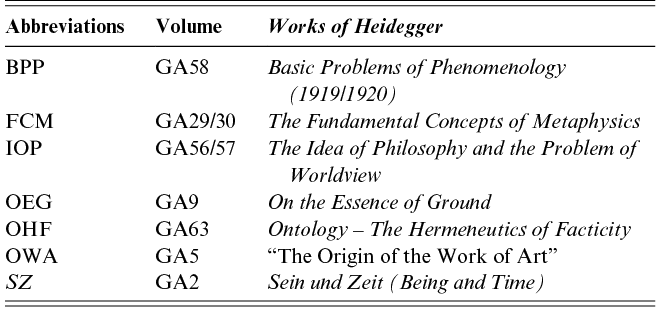

The following abbreviations are used to refer to works of Heidegger that figure centrally in the discussion:

| Abbreviations | Volume | Works of Heidegger |

|---|---|---|

| BPP | Reference GanderGA58 | Basic Problems of Phenomenology (1919/1920) |

| FCM | Reference von HerrmannGA29/30 | The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics |

| IOP | Reference HeimbüchelGA56/57 | The Idea of Philosophy and the Problem of Worldview |

| OEG | Reference von HerrmannGA9 | On the Essence of Ground |

| OHF | Reference Bröcker-OltmannsGA63 | Ontology – The Hermeneutics of Facticity |

| OWA | Reference von HerrmannGA5 | “The Origin of the Work of Art” |

| SZ | GA2 | Sein und Zeit (Being and Time) |

Introduction

The topic of this Element is being-in-the-world, a central concept in the central work of Heidegger’s early philosophy: Being and Time (hereafter SZ), which was published in 1927.Footnote 1 Although Heidegger continued to think and write for nearly fifty more years after the work’s appearance (he died in 1976) and although his thinking and style of writing changed dramatically over that time, SZ remained a touchstone throughout. A case can thus be made that having a good grip on this concept is crucial for understanding any phase of Heidegger’s philosophy.Footnote 2

Although Heidegger does not use the exact phrase being-in-the-world until the opening pages of Division One of SZ, he alludes to it in his remarks very early on. In § 4, after noting how the sciences involve Dasein’s relating to entities other than itself, Heidegger writes:

But to Dasein, being in a world is something that belongs essentially. Thus Dasein’s understanding of being pertains with equal primordiality both to an understanding of something like a ‘world’, and to the understanding of the being of those entities which become accessible within the world

That being in a world “belongs essentially” to Dasein, in effect to beings who exemplify our way of being, indicates the centrality of the concept: Being in a world is not in any way optional or contingent. The phrase “Sein in einer Welt” (being in a world) points toward the more canonical In-der-Welt-sein that appears later and that forms part of the title for the second chapter of Division One (“Being-in-the-world in General as the Basic State of Dasein”). We will have occasion shortly for considering that longer discussion (the interplay between Heidegger’s talk of a world and the world will receive considerable attention). For now, I want to note how this passage connects the idea of being in a world with another central concept in SZ: Dasein. This term is generally left untranslated, which indicates its standing as a kind of technical term for Heidegger. The term Dasein in ordinary German simply means existence. That is important for Heidegger, but his more technical use of the term exploits the structural elements of the word: Da-, which means there, and -sein, which means being. So Dasein means there-being, which points to the idea that Dasein is something for whom its existence is there for it, and for whom being is there more generally. To say that they are there for Dasein is to say that they are understood in some way. These ideas are evident in the two explicative formulations of Dasein he offers early on:

i. Dasein has an understanding of being

ii. Dasein is a being whose being is an issue for itFootnote 4

Although they by no means sound equivalent, it is important not to read these as two separate claims. What I mean here is that (i) and (ii) should not be considered as independent of one another in the sense that something might be characterized by (i) without being characterized by (ii), and vice-versa. As a being with an understanding of being, Dasein – the kind of beings we are – can raise and pursue the question of being, which further means that it can question its own being, that is, its own being is, for it, a question.

Very roughly, we can say that Dasein can ask about itself, “Who am I?” and furthermore appreciate the open-ended character of that question: As long as I exist, I can continue to raise this question, and what strikes me as even a definitive answer can change over time (moreover, anything resembling a final answer to the question will only be available when I am no longer around to appreciate it, but that is a topic for another occasion). If we think further about this question that we can pose of and to ourselves, we can get a glimmer of how being-in-the-world is likewise not separate from (i) and (ii) in the sense that to be a being whose way of being is being-in-the-world is to be a being marked by those first two claims. Consider one thing that I might say about myself by way of trying to answer the “Who am I?” question: I am a professor. Understanding myself as a professor is not a matter of affixing a label to myself, or having an identification card in my wallet attesting to my being one. Beyond labels and ID cards, being a professor means having a particular institutional status. Insofar as I understand myself as a professor I understand myself as having that status with respect to an institution – the university where I work – and I understand that status as involving various obligations and responsibilities, such as teaching classes, grading papers, writing articles and books, and attending conferences. I also understand that status as intertwined with other institutional statuses: deans and provosts, for example, but also students, departmental administrators, and so on. Notice that even with just this much we can see that understanding myself as a professor enlists an understanding of all manner of things: universities, classrooms, students, syllabi, referee requests, and so on. Self-understanding is in this way worldly: I cannot understand myself as a professor – I cannot be a professor – without a considerably wider range of understanding that locates my existence in a broader setting, that is, a world.

When I was a teenager – long before I became a professor – I went on a fieldtrip to a museum of holography in New York City (a quick Google search suggests that it is still there). A hologram is a special kind of photographic image. What is special about it is revealed when a laser is shined through the image on film, which is projected as a three-dimensional image that appears to be there, but in a ghostly way. One particularly striking thing I remember from the fieldtrip is being told – and shown – how the full three-dimensional image can be projected from even one small piece of the holographic image on film: The parts of the film image somehow manage to encode the whole. It is a good idea to keep in mind this special feature of holograms when reading Heidegger. SZ has a kind of holographic structure in that any particular claim Heidegger enters – any particular piece of the project he lays out – can with the proper illumination project an image of the whole. What we’ve just seen about Heidegger’s two claims pertaining to Dasein and their revealing already the outline of being-in-the-world illustrates this idea. Further illustration will be made when we consider Heidegger’s claim that being-in-the-world is a unitary phenomenon that can nonetheless be considered from different angles. In each case, the aspect under consideration – if considered properly – should lead us back to the whole phenomenon.

This Element will consider being-in-the-world from a number of different angles. Section 1 takes a genealogical approach that considers examples of Heidegger’s attempt to thematize the phenomenon of world on the way to his more canonical formulations in SZ. Section 2 considers that formulation in more detail. I there follow Heidegger’s lead in treating the phenomenon aspectually, that is, as having mutually implicating aspects or dimensions rather than independently characterizable parts. In Section 3, I step back – as Heidegger does in the last chapter of Division One – to assess the broader philosophical significance of being-in-the-world by considering its impact on our understanding of skepticism, realism, and idealism. Finally, in Section 4, I look briefly at some of Heidegger’s work in the aftermath of SZ where he revisits the idea of being-in-the-world in ways that both correct and expand our understanding of it.

1 On the Way to Being and Time

1.1 Heidegger’s Early Lectures

The phrase that is central to this Element – being-in-the-world – can be found prior to SZ. The phrase figures prominently in his 1924 Basic Concepts of Aristotelian Philosophy and close approximations appear in his 1923 Ontology – The Hermeneutics of Facticity lectures, where he uses “being ‘in’ the world” without hyphens, as well as “being-‘in’-a-world,” “being-‘within’-a-world,” and “to-be-‘in’-the-world.” However, the ideas that come to be condensed into this hyphenated expression can be traced back even further, to some of Heidegger’s earliest lecture courses starting in 1919. In this section, I want to examine some of Heidegger’s explorations in these very early lectures that initially point to – and begin to deploy – the notion of being-in-the-world. In accordance with the preliminary status of this early material – and in keeping with the brevity of this Element – this section will contain only a series of sketches to prepare the way for our examination of SZ.Footnote 5 But these samplings from lectures ranging from 1919 to 1923 provide important insights that will assist us in understanding his more refined ideas; of interest as well are tentative formulations that did not make the cut, so to speak. Conjecturing as to why will prove useful as well.

1.2 1919: Es Weltet (It Worlds)

At the outset of Part Two of his 1919 course, The Idea of Philosophy and the Problem of Worldview (IOP),Footnote 6 Heidegger promises his students that they will “for the first time … make the leap into the world as such” (Reference HeimbüchelGA56/57: 63). Heidegger’s vow follows a series of false starts and dead ends in a quest to characterize what he refers to as a “primordial science.” By primordial, Heidegger is trying to determine what serves as originary in relation to the numerous specialized sciences – natural and otherwise – such as physics, biology, and history. A primordial science “will not be a science of separate object domains, but of what is common to them all, the science not of a particular, but of universal being” (GA56/67: 26).Footnote 7 None of the special sciences has the requisite generality to account either for their own possibility or for the possibility of the others.

A great deal of the first part of the lecture course is devoted to explaining why psychology is ill-suited to serve as a primordial science. Although psychology promises a general account of experience, as well as of the subject who has experiences, Heidegger complains that psychology misconceives the character of what he calls lived-experience. Whereas psychology characterizes experience as a kind of psychic process that occurs within the subject, Heidegger thinks that more careful attention to the character of a subject’s lived-experience points away from anything characterizable in terms of inner processes: “When we simply give ourselves over to this experience, we know nothing of a process passing before us, nor of an occurrence” (Reference HeimbüchelGA56/57: 65). When we conceive of – and talk about – experience, there is a danger of objectifying that experience, treating “it” as a something that occurs in the manner of a process or sequence of events whose relation to anything else is obscure. As Heidegger sees it, the challenge is to describe experience without thereby objectifying it.Footnote 8

Heidegger’s lead-up to the leap begins with an interrogation of what presents itself as the barest, most general, and in this way, most primordial form of experience: the experience of “there is,” which he considers more expansively as “there is something.” The generality of such an interrogative gesture risks emptiness, but Heidegger’s point here is that even this bare “there is something” goes beyond the model of internal psychic processes whose connection to anything external has not been clarified. Even in the experience only of “there is something,” we can already discern something “non-thingly” about it: “The ‘relating to’ is not a thing-like part, to which some other thing, the ‘something’ is attached. The living and the lived of experience are not joined together in the manner of existing objects” (Reference HeimbüchelGA56/57: 69–70). Relating to is comportment toward something, an active encountering – and making sense – of something. In this way, it is already beyond any kind of internal psychic process.

To illustrate this, Heidegger pivots to a more concrete example, which both he and the students to whom he is lecturing can enact and attend to without having to look any further than where they already are. The “there is something” can be filled in – given definite content – by considering the lectern Heidegger is currently using. What Heidegger wants his students to notice here is the familiarity and immediacy in play in the experience of the lectern. The experience of the lectern is not pieced together from a series of sensory processes that involve the awareness of something less than the lectern; he and the students do not infer that what they see is a lectern on the basis of something they initially discern or have, such as sensations of colors and shapes. There are, Heidegger contends, no such prior processes: The lectern is seen directly by both him and his students when they enter the room, and in more or less the same way. Both Heidegger and the students see it as the place where the lecturer stands. As the lecturer, Heidegger sees it as the place for him, while the students see it as the place in the classroom toward which they are expected to look. When the students enter the classroom, they take in the lectern as playing a particular role in what they are up to – attending a class meeting – and the same is true for Heidegger. They thus do not experience the lectern as an isolated thing that then might be understood as standing in relation to other things that are likewise initially experienced as isolated. The lectern is instead experienced from out of and against the backdrop of a broader environment: the classroom, the university building that houses the classroom, the university, and so on. The lectern is “given … from out of an immediate environment” (Reference HeimbüchelGA56/57: 72). This environment should be understood as an “environmental milieu” that “does not just consist of things, which are then conceived of as meaning this and this.” Instead, “the meaningful [das Bedeutsame]Footnote 9 is primary” and this fullness of meaning is “immediately given to me without any mental detours across thing-oriented apprehension” (Reference HeimbüchelGA56/57: 73). Although the example of seeing the lectern involves attending to just one item – the lectern – seeing it as a lectern involves grasping its significance in relation to the environment in which it has its place. We can think of that environment both narrowly and widely: narrowly, as the immediate environment of the lecture hall and the university, but more broadly as the public realm within which the university is situated. Hence Heidegger’s characterizing the environmental milieu as involving “lectern, book, blackboard, notebook, fountain pen, caretaker, student fraternity, tram-car, motor-car, etc.” (Reference HeimbüchelGA56/57: 72). Tram-cars and motor-cars are not typically found in lecture halls, but the environment within which lecture halls are found is not cut off from the broader surroundings of roadways and traffic.

Heidegger’s appeal to seeing the lectern culminates with his noting that “living in an environment, it signifies to me everywhere and always, everything has the character of world. It is everywhere the case that ‘it worlds,’ which is something different from ‘it values’” (Reference HeimbüchelGA56/57: 73). Heidegger’s use of weltet as a verb formed from the German Welt is nonstandard, just as it is in English (even though “verbing” has become commonplace, especially in American English). Heidegger’s “it worlds” here indicates – and emphasizes – the kind of signifying that pervades our lived-experience, the “everywhere and always” wherein the lectern is apprehended. Seeing the lectern as a lectern involves seeing it within that “environmental milieu;” the milieu is prior in that an understanding of it informs the seeing of the lectern, rather than the other way around. That is, we do not first see the lectern, the seats, the walls, and so on, and from all that piece together the idea of a university as composed of such things. While it is no doubt true that the university’s facilities include such items, their significance flows from university to item. Seeing the lectern as a something-for-teaching-in-a-classroom is an instance of such worlding. The primacy of “it worlds” is further emphasized by Heidegger’s differentiating it from “it values.” To conceive of the lectern as something with the value of being used for lecturing invites the kind of model of understanding Heidegger wants to avoid: We first apprehend the thing – the wooden box, the brown rectangular object, or what have you – and then assign to that the value of being good for lecturing. Heidegger rejects this model not just because it starts with a collection of initially value-less objects, but because it relies on a conception of value-assigning subjects who are initially isolated or cut off from the world.

Using world as a verb – “es weltet” – further underscores a categorical difference between the particulars that populate an environment and the world comprising those particulars. The world is not one more such item, the largest or most general thing, “inside” of which all these particulars can be located. To say that these particulars – and the experience of them – world does not mean that they are all located in a common space (even if they happen to be), but instead that they signify one another in ways that show their interconnections, their fitting together into – and within – a common way of life. They are connected in the way that the words of a language are connected to one another (in contrast to the words making up other languages). It worlds is akin to saying something like it Englishes for everything that I say or write, insofar as I am speaking or writing in English. Whenever I speak, I am not doing two different things – saying the particular thing I am saying and speaking English – but that what I am saying is in English is indicated every time I speak. Being-in-English is not a further word or bit of grammar in addition to particular words and grammatical structures, but the holding together of all of that into a whole language set off from other whole languages such as German, French, and Chinese.Footnote 10

1.3 1919/1920: Life and the Threefold Sense of “World”

Not surprisingly, given its proximity to the lecture course just considered, Heidegger’s 1919–1920 Basic Problems of Phenomenology is guided by many of the same questions and concerns that animated the IOP lectures. The guiding question of the lecture is succinctly stated early on: “How do we wish to establish a strict science in this constantly flooding fullness of life and worlds” (Reference GanderGA58: 37–38)? Again we see a desire for a new kind of science – an originary, primordial, and now strict or rigorous science – whose target is life as it is most basically or fundamentally experienced. Central to these lectures is the interplay between the pair of concepts he invokes in articulating his basic question, the interplay between life and worlds (in the plural). Life and worlds for Heidegger are only notionally separable from one another: “All life lives in a world. Overall, what happens to worlds and to parts of the world happens in the living stream and pull of life” (Reference GanderGA58: 36).

In these lectures, Heidegger pluralizes world in more than one way. First, world is categorically plural. He distinguishes among three senses of world: the environing-world, the with-world, and self-world. Second, what belongs to these categories – particular worlds – likewise admits of pluralization: There are as many self-worlds, for example, as there are selves (living individuals), but even world in the other two senses admits of multiplicity as well. At the same time, we should not think of world in these three senses as designating freestanding, independent notions; on the contrary, the three permeate one another.Footnote 11 Heidegger characterizes “life in the environing world” as an “unstable circumstantiality” that involves “a peculiar self-permeating of the environing world, with-world, and self-world, not out of their mere aggregation.” He adds that “the relations of the self-permeating are absolutely of a nontheoretical, emotional kind. I am not the observer and least of all am I the theorizing knower of myself and of my life in the world” (Reference GanderGA58: 39).Footnote 12

Heidegger’s talk here of self-permeation follows on from an illustrative description of worldly life that moves freely among the three senses of world. The passage is worth quoting at length:

Thus, all kinds of things, which lie in the circle of each one of us, and in the circle that is always going along with life streaming forth: our environing-world – landscapes, regions, cities and coasts; our with-world – parents, siblings, acquaintances, superiors, teachers, students, officials, strangers, the man there with the crutch, the woman over there with the elegant hat, the little girl here with the doll; our self-world – insofar as that directly encounters me in such and such a way and directly imparts upon my life this, my personal rhythm. We live in this environing world, with-world, self-world (generally environing-) world. Our life is our world, which we seldom see, but rather always, if also in a way that is wholly inconspicuous and hidden, “are by it”: “captivated,” “repelled,” “enjoying,” “renouncing.” “We are always somehow encountering.” Our life is the world, in which we live, into which and in each case within which the tendencies of life flow. And our life is only lived as life insofar as it lives in a world.

Living in – or having – a self-world is not something I do separately from living in a with-world or in an environing-world. In living in – or having – any one of them, I thereby also live or have the others: The self-world designates the “personal rhythm” of my life, which I live out in a broader array of places and regions (environing-) in which I encounter myriad others (with-world ) likewise navigating these places and regions with their own personal rhythms. In the second chapter of the lecture course – starting at § 9 – Heidegger introduces another image that develops “the peculiar self-permeation” he noted previously: What he here refers to as factical life comprises a “multiplicity of telescoping layers of manifestation.” The word translated (appropriately) as telescoping is ineinanderschiebender, which could be clunkily rendered as pushing-into-one-another. The clunky rendering helps us to see that Heidegger is not talking primarily about the optical properties of telescopes that allow us to see things up close that are very far away. Rather, he is playing off of the physical structure found not so much with telescopes proper but with instruments such as an old-fashioned seafarer’s spyglass whose differently sized cylindrical segments nest into one another (we might also here think of telescoping antennas of the kind found on older cars and transistor radios). Worlds in Heidegger’s three senses are related to one another in this telescoping manner: Each “segment” is another “layer of manifestation,” a different way in which the worldliness of life is evident. If we compress the telescoping segments completely, we get a broad sense of a public world, but we can expand the telescoping segments by narrowing our gaze to consider the smaller segments: First, we can consider the environing-world at more fine-grained levels. Heidegger’s example in his earlier lecture of the way the lectern worlds illustrates this: The environing world from out of which things such as trams and trolleys are encountered can be “expanded” to reveal the academic world of the university, which is nested within that broader environs. The sense of nestingFootnote 13 here is not physical containment, but a nesting of senses: The sense of the academic world borrows from – and depends upon – the sense of the broader environing world. In keeping with Heidegger’s appeal to permeation, we can appreciate how the kind of sense things make in the academic world are permeated by more broadly applicable senses. Although academia has its own specialized range of activities and paraphernalia, much of what goes on in this world carries over from more general and generic ways of living: chalkboards are for-writing-on just as much outside the halls of a university as they are within them.

The environing-world at both levels of description points toward the with-world, which again admits of finer- and coarser-grained levels of description: for Heidegger’s audience, one’s instructors and fellow students are integral to life within the university, but all of them are related to other others; these relations vary considerably in terms of the level of personal connection or intimacy. One’s family and friends make up a dimension of the with-world, but also more or less anonymous others that contribute to the hustle and bustle of life in any particular community (all those (almost faceless) others on the tram-car, for example). We can think of the self-world as referring to the narrowest segment of this telescoping structure, which refers to the particular rhythms and flows of an individual life: my life in contrast to the lives of everyone else. I have a biography that pertains to me exclusively and I correspondingly have a pattern of living that is marked by a particular combination of habits, routines, priorities, interests, aspirations, thoughts, fears, anticipations, recollections, and so on. The surroundings that are familiar to me – where I feel most at home – are not familiar in that way to more than a handful of other people (my wife and children, in my case) and even so, my familiarity is differently inflected even from theirs: My activities within our shared residence, for example, center upon different tasks and in some cases involve items that no one else in the house uses (or even knows how to use). That my familiarity is inflected differently does not relegate my self-world to a realm of Cartesian privacy: What is familiar to me are worldly spaces and places, populated by things that are used and spoken of in ways that are common across individuals. “I live in the vital direction of pull into a world, and I live it out” (Reference GanderGA58: 96). I can try to describe this “pull” – the contours and rhythms of my life – which I might preface by saying, “Welcome to my world.” But the “I” does not exclude the “we.” “We are standing in our factical life, and we speak and understand in the circle of our understandability” (Reference GanderGA58: 98). Heidegger’s emphasis here on our indicates the way the myriad self-worlds found telescoped within the with- and environing-world are informed by and relate to those broader senses of world: “I live factically always caught into meaningfulness, and every meaningfulness has its encirclement of new meaningfulnesses: horizons of occupation, sharing, application, and fate” (Reference GanderGA58: 104–105).

Although I warned against hearing Heidegger’s talk of telescoping as referring to the optical properties of telescopes, there is something in the image of how telescopes are used that is applicable here.Footnote 14 If we consider further the nesting cylinders of a telescope – or spyglass – one looks through it from the narrowest or smallest cylinder, the eyepiece. Although what one sees from that vantage-point is crucially affected by the optics found in the larger cylinders, nothing is really apparent without looking (and looking from just there). In Heidegger’s taxonomy of worlds in these lectures, the self-world corresponds to what in the spyglass is the eyepiece: The self-world is the locus of life in the most fundamental sense. Living individuals are what populate and animate worlds in the other two senses and worlds in the other two senses are accessed through the self-worlds of individuals. Although self-worlds are permeated by the other- and environing-world – just as what I see through the spyglass is determined by the optical properties of the larger cylindrical segments – without selves, worlds would be lifeless. We might here adapt Kant’s famous dictum about concepts and intuitionsFootnote 15 and say: Worlds without selves would be empty, while selves without worlds would be blind.

1.4 1923: A Tale of Two Tables

As the title to his 1923 lecture course – Ontology – the Hermeneutics of Facticity – suggests, Heidegger here continues, and develops considerably, ideas that had been in play as far back as 1919. The IOP course ends with an appeal to “hermeneutical intuition” as an alternative to Husserl’s conception of phenomenology as essentially reflective. And as just seen, factical life is central to his BPP lectures. The two notions work hand in hand: “The expression ‘hermeneutics’ is used here to indicate the unified manner of the engaging, approaching, arresting, interrogating, and explicating of facticity” (Reference Bröcker-OltmannsGA63: 9).Footnote 16 The approach is hermeneutical insofar as it works from factical life (the forehaving) and back to it: “The fate of our approach to phenomena and our execution of concrete hermeneutical descriptions of them hangs on the level of the primordiality of the forehaving into which Dasein as such (factical life) has been placed” (Reference Bröcker-OltmannsGA63: 80).

How do these “hermeneutical descriptions” involve a sense of world ? In the second part of the lecture course, Heidegger offers what he calls a formal indication of the “forehaving” that serves as the starting point for the interpretive development of any hermeneutical descriptions.Footnote 17 We can understand formal here as provisional in the sense that the initial pointing leaves open the content of what has been indicated. Formal indications require some kind of “filling in.” But even without filling in, formal indications – as indications – point toward what is to then be interpreted, but also – and importantly – point away from conceptions of factical life that amount to misinterpretations. Both the positive and negative moments deserve consideration. Here is Heidegger’s formal, provisional characterization of the forehaving operative in factical life: “The forehaving in which Dasein (in each case our own Dasein in its being-there for a while at the particular time) stands for this investigation can be expressed in a formal indication: the being-there of Dasein (factical life) is being in a world” (Reference Bröcker-OltmannsGA63: 80). As formal, this indication needs “to be demonstrated in intuition.” Doing so involves addressing the following three questions: “What is meant by ‘world’? What does ‘in’ a world mean? And what does ‘being’ in a world look like?” (Reference Bröcker-OltmannsGA63: 85).

We can work toward answers to these questions by considering the example Heidegger develops at length. Rather than a lectern in the lecture hall, Heidegger instead considers a table in his home. I said before that Heidegger’s formal indication points both toward and away; his handling of the example of a table incorporates these negative and positive dimensions of his gesture. Heidegger especially wants to exclude two prevalent ways of describing the experience of the table and, by extension, factical life more generally. He refers to both in the lectures as misunderstandings, that is, ways of mischaracterizing or outright missing what pertains to factical life. The first such misunderstanding is what he calls the subject-object schema: according to this schema, to experience a table is to become aware of one object among others in one’s experiential field. The table is experienced as a spatial, material thing possessing various properties: a particular weight, shape, hardness, color, and so on. These properties are experienced perspectivally by the perceiving subject: At any given time, I see the table from a particular angle. As I move around the table, I see it from a multiplicity of angles; in each case, the table has a slightly different apparent shape, but the changes can be understood as a function of the table’s actual shape and my spatial location (along with facts about my height, the direction of my gaze, and so on). The changing apparent shapes thus form a series; the orderliness of the series conveys to me the stability and persistence of the table as an object with a constant shape. I don’t see that constant shape directly, but I can infer it from the way the series of apparent shapes holds together. Similar considerations pertain to my seeing the table as having a constant color, which I likewise don’t see directly, but infer from the various ways the color appears from different angles (some of which produce patches of glare on the table, for example, thereby making those bits of the table’s surface appear nearly pure white), along with facts about the lighting conditions, and so on.

Seeing the table as one object among others divests from the table any and all of its practical value. The second misunderstanding Heidegger wants to avoid is evident here: the prejudice of freedom from standpoints. The idea here is to insist upon the primacy of the most neutral characterization of the table. The table is manifest as merely an object – one object among others – that possesses in itself a range of properties. Anything pertaining to its practical value is secondary, something that the perceiving subject projects into or onto the table. Considered apart from the perceiving subject’s interests and values, it is a particularly shaped arrangement of matter and no more. That is what the table really is, while everything else we might want to say about the table is subjective imposition.

The key question here is whether we recognize in these descriptions the way tables are manifest in everyday experience. Heidegger wants us to see just how artificial these schemata are. Notice first that these schemata direct our attention to a table, a single something-or-other divorced from any kind of setting or context. But in our everyday experience, we do not experience some table or other – or tables in general – but this or that table, such as the one found in this room in this house and used for these activities.Footnote 18 The table is experienced as part of the room, as having been on that side of the room before, but now closer to the window to take advantage of the sunlight that shines into the room in the afternoon. The table has chairs around it where the different members of the family sit, perhaps for meals but also for various activities such as doing homework, writing letters, and working on an arts-and-crafts project. Different members of the family might have their respective places to sit: The elder brother sits there, while the younger brother sits across from him, and the parents sit at each of the narrower ends. The daily traffic through the room involves the table and takes account of its presence: Members of the family walk in and out of the room without bumping into the table, various items are placed onto and taken off the table throughout the day, and so on. At the same time, the table is scarcely noticed, but relied upon without anyone’s stopping to pay any particular attention to it (no one usually walks around the table to attend to the changes in its apparent shape unless someone has signed up for a drawing class). The table bears the history of the family who uses it: Various scratches record a child’s mischievous moment; the discoloration in one corner indicates the injudicious use of paint thinner; a scorch mark in the middle testifies to a toppled candle. “That is the table – as such it is there in the temporality of everydayness” (Reference Bröcker-OltmannsGA63: 90).

Heidegger’s first question for developing his formal indication is, “What is meant by ‘world’?” We can work toward an answer to this question by reflecting on the kind of description of the table Heidegger favors as truer to how such things are experienced in everyday life. That kind of description locates the table within a broader setting – the room, the house, and so on – and describes its role or place in the ongoing lives of the family whose table it is, who are familiar with the table and make use of it as they go about their lives. How the table is experienced – what the table primarily is – is as situated in the world of that family. World in this sense “shows itself as that wherefrom, out of which, and on the basis of which factical life is lived” (Reference Bröcker-OltmannsGA63: 86). The key notion for understanding the sense of world here, as with his earlier lectures, is significance (Bedeutsamkeit): “The as-what and how of [the world’s] being-encountered lie in what will be designated significance” (Reference Bröcker-OltmannsGA63: 93). We will consider Heidegger’s more developed account of significance in SZ shortly. For now, let us just consider how he answers the two other questions he raises to fill out the formal indication of being in a world. The second of these three questions is: “What does ‘in’ a world mean?” The table is something found in a world, in this case, in the world of a particular family. The sense of “in” is a spatial sense, but that sense is not captured by giving the table’s GPS coordinates or the like. To say that the table is in that world means that it has a place in that world and a role within that family’s ongoing life. The members of the family are also in the world, not just by being located in a particular geographical space (although that is true about them just as much as it is for the table). Rather, the members of the family live in that world. The members of the family are in the world in a way that is related to, but importantly different from, the way the table is in the world. The table is significant – and has the significance it has – because of its significance to and for the family. Nothing is significant to or for the table: The table is found in that world, but the table doesn’t live there. Nothing matters to the table, but the table does matter for the people who use it, who care for it or neglect it as the case may be. This asymmetry between the table and the people who use it points toward the beginnings of an answer to the third question: “And what does ‘being’ in a world look like?” The table is just there in the world, but those who live in the world are the ones for whom the table has whatever significance it has. Again, the table matters to the people who use it: Mattering is the registering of significance, which is why Heidegger says that the “being of the world and that of human life are designated in the same manner with the term ‘being-there’” (Reference Bröcker-OltmannsGA63: 86). More on this in Section 2.

2 Canonical Formulations

2.1 Looking Ahead by Looking Back

In Section 1, we considered three of Heidegger’s early lecture courses from 1919 to 1923. Here are some of the key ideas:

i. World as a wherein or from out of which

ii. World as a space or structure of significance or meaningfulness (both translations of Bedeutsamkeit)

iii. World as coordinate or correlative with life

iv. World as multidimensional, encompassing self, others, and environment

v. World as both categorically and concretely plural

In his 1924 lectures on Aristotle, Heidegger begins using the hyphenated phrase being-in-the-world with far greater frequency. As before, life is a fundamental concept: Only what is alive can be said to have a world. This is true for animals as much as for human beings:

Ζωή is a concept of being; ‘life’ refers to a mode of being, indeed a mode of being-in-a-world. A living thing is not simply at hand, but is in a world in that it has its world. An animal is not simply moving down the road, pushed along by some mechanism. It is in the world in the sense of having it.

To say that an animal has a world means that an animal is oriented toward – and responsive to – its environment in ways that reflect its needs and capacities. Primarily, there are things that an animal typically does – and has to do – in order to keep itself alive (and also reproduce, thereby keeping its species alive).Footnote 19 What shows up to or for the animal is conditioned by those demands: The animal’s environment is carved up, so to speak, in terms of opportunities and obstacles for it and what counts as an opportunity and what counts as an obstacle varies in accordance with the animal’s nature. What shows up as something to eat, for example, will be very different for a snake than for a deer; likewise, for what shows up as a threat. What counts as a good place to hide, a safe place to sleep, a suitable mate, and so on will all vary in accordance with the kind of animal we are considering. In this way, we can think of the world of the snake and the world of the deer as different worlds, even if they are located in more or less the same place.

Although Heidegger here includes animal life within the range of what has a world, in the Aristotle lectures, he marks out human existence as distinctive in terms of the form that having a world takes: “The being-in-the-world of the human being is determined in its ground through speaking. The fundamental mode of being in which the human being is in its world is in speaking with it, about it, of it” (Reference MichalskiGA18: 18).Footnote 20 That speaking and language are fundamental here preserves the interplay Heidegger registers in his earlier lectures of self and others: In speaking, I talk about the world, and I talk with and to others.

While the Aristotle lectures underscore the connection between being-in-the-world and life, such that the “basic mode of the being of life” just is “being-in-a-world,” in SZ, the category of life is hardly mentioned and when it is, it is relegated to a decidedly secondary position in relation to an ontology of Dasein:

The ontology of life is accomplished by way of a privative interpretation; it determines what must be the case if there can be anything like mere-aliveness [Nur-noch-leben]. Life is not a mere being-present-at-hand, nor is it Dasein. In turn, Dasein is never to be defined ontologically by regarding it as life (in an ontologically indefinite manner) plus something else.

Whereas the early lectures generally were saturated with talk of life – the flow of life, sympathy with life, lived-experience, the intensification of life – SZ is largely purged of all such talk. What motivates the purge is Heidegger’s conception of his project in SZ as a formal and transcendental project. As a development of a fundamental ontology, it is necessary to steer clear of any contingent, empirical dimensions of human existence (human existence is his only available – but not necessarily the onlyFootnote 21 – instance of Dasein). Even though it is true that we are biological beings, what pertains to our biology is in no way essential to – or necessary for – being a being with Dasein’s way of being.

2.2 Dasein’s Worldly Existence

In the introductory remarks prior to the start of Division One, Heidegger says that being-in-the-world is “a fundamental structure of Dasein” (SZ: 41), adding that this structure is a priori. He also refers to it – in the title to the second chapter of Division One – as “the basic stateFootnote 22 of Dasein.” A further point in his opening remarks bears emphasizing: After noting its a priori character, Heidegger adds that being-in-the-world “is not pieced together,” but rather “is primordially and constantly a whole” (SZ: 41). This is in keeping with his characterizing it as a unitary phenomenon. Rather than consisting of separate – and separable – parts that are independent of one another, as a unitary phenomenon, it should be thought of as having non-separable moments or aspects that can be variously emphasized, albeit without losing sight of the phenomenon as a whole. This exemplifies what I referred to in the Introduction as the holographic structure of SZ: While Heidegger, in the course of his investigation, concentrates on one aspect or another of what is designated by his hyphenated expression, the account that emerges always implicates – and so brings into view – the other aspects. Illuminating any one aspect ultimately gives us an impression of the whole.

The exposition of Division One accordingly concentrates serially on different aspects of being-in-the-world, segmented (roughly)Footnote 23 as follows:

i. -in- (Chapter Two)

ii. -the-world (Chapter Three)

iii. Being- (Chapter Four)

iv. Being-in- (Chapter Five)

The first chapter gives a preliminary explication of Dasein, which, as indicated earlier, emphasizes the way this account should not be construed as a chapter of – or relying upon – any kind of psychology, anthropology, or biology. Put more positively, Heidegger develops further ideas first mentioned in the opening sections of the work: that Dasein’s “‘essence’ lies in its existence;” that Dasein “has in each case mineness” (SZ: 42); and that Dasein has its being “as an issue,” and so “comports itself towards it” (SZ: 44).Footnote 24 These ideas are, among other things, preparatory for Heidegger’s explication of the sense of “in” in the phrase being-in-the-world: Since Dasein is “never to be taken ontologically as an instance or special case of some genus of entities as things that are present-at-hand” (SZ: 42), the sense of “in” at issue in Dasein’s being in the world is not a matter of spatial-material containment. Dasein is not in the world in the way that water is in a glass or my desk is in my study (see SZ: 53–54). Even though it is true that each and every one of us is materially located in that way (e.g. I’m spatially located inside my house as I write this), fixation on that spatial sense of in only obscures the phenomenon Heidegger wants to explicate.

Rather than any kind of spatial containment, the sense of “in” is here one of involvement. Heidegger traces the German in to innan, where the an designates being accustomed to something, familiar with it, or looking after it (SZ: 54). Dasein is in the world in the sense of being familiar with it and feeling at home in it. The sense of “in” can be understood here along the lines of the way we say in English that someone is in business or in academia, which primarily designates a principal locus of that person’s activities regardless of where spatially those activities take place (and even if they are often engaged in at particular locations, such as office towers or college campuses). Keeping this sense of “in” at the forefront is crucial for understanding how Heidegger explicates the notions of world and worldhood.

2.3 A New Typology: Worlds from “A” to “The”

Our examination of Heidegger’s early lectures in Section 1 documented how the idea of world figures prominently throughout. Moreover, we saw how Heidegger in different courses tries out different ways of talking about, and characterizing different senses of, world – world as a verb (“es weltet”); a threefold taxonomy of self-world, other-world, and environing-world related through “telescoping layers of manifestation;” and being in a (rather than the) world – before finally settling on the terminology of being-in-the-world. In Chapter Three of Division One of SZ, he offers a new taxonomy of the senses of “world” that does not correspond to any of his prior terminological and conceptual ventures. This is not to say that all of what precedes SZ has been abandoned. Far from it: many of his earlier ideas persist, albeit without always being designated with dedicated terms, and it will be helpful at various points to refer back to these earlier discussions.

The taxonomy Heidegger offers in SZ now distinguishes among four senses of “world.” These four senses can be sorted into two categories: a categorical sense, which Dreyfus in his commentaryFootnote 25 helpfully construes as an inclusive sense of world, and an existentiell-existential sense, which Dreyfus glosses as designating involvement. The pairs in each of these two categories can be further sorted into an ontical sense, that is, a sense pertaining to particular entities and their arrangement, and an ontological sense, which pertains to the way of being of those particulars. Here is how Heidegger himself marks out the different senses:

1. “World” is used as an ontical concept, and signifies the totality of those entities that can be present-at-hand within the world.

2. “World” functions as an ontological term and signifies the being of those entities that we have just mentioned. And indeed “world” can become a term for any realm that encompasses a multiplicity of entities: For instance, when one talks of the “world” of the mathematician, “world” signifies the realm of possible objects of mathematics.

3. “World” can be understood in another ontical sense – not, however, as those entities that Dasein essentially is not and which can be encountered within the world, but rather as that “wherein” a factical Dasein as such can be said to “live.” “World” has here a pre-ontological existentiell signification. Here again there are different possibilities: “world” may stand for the “public” we-world or one’s “own” closest (domestic) environment.

4. Finally, “world” designates the ontological-existential concept of worldhood. Worldhood itself may have as its modes whatever structural wholes any special ‘world’ may have at the time; but it embraces in itself the a priori character of worldhood in general. We shall reserve the expression “world” as a term for our third signification. If we should sometimes use it in the first of these senses, we shall mark this with single quotation marks (SZ: 64–65).

We do not need to worry overly about the first two notions of world, as they are indicated primarily to be set aside. They are not, we might say, where the action is as far as Heidegger is concerned. Indeed, Heidegger says that he will reserve the term world as primarily designating the third of the four senses he delineates. Still, that there are four senses in play indicates a certain unruliness in the notion of world, and that is perhaps as it should be. Even without yet entering into Heidegger’s ontological project, our ordinary uses of “world” are varied and not entirely systematic: We talk about the world of stock-car racing, a particular loved one being the whole world to someone, a trip to a neighboring state (or county, or even just a neighbor) as entering a different world, and so on. Some of these uses are no doubt figurative, but we should not lump all of them into that category. Heidegger’s own more systematic regimentation absorbs rather than eliminates this unruliness: His third sense of world, the very sense he favors, freely admits of pluralization and is naturally spoken of in the singular with the indefinite article – “a world” – rather than the definite. Just why this should be thought of as unruliness will become clear as we proceed further: Demarcating worlds and distinguishing them from one another is anything but cut and dry.

In exploring Heidegger’s taxonomy more fully, we need to confront a question that has been lurking throughout: How, if at all, are we to understand talk about the world in contrast to talk about a world (and likewise worlds in the plural)? Notice already that this one question actually contains several. For example, we can ask about the singularity of the world in relation to the first sense. I take it that there is an issue to be raised there, but that is an issue as to the propriety of talk of a (physical) universe, as opposed to, say, a multiverse, about which I get the sense some scientists see fit to speculate.Footnote 26 That sense of unity and singularity is accordingly a scientific question, which does not properly arise within the project of SZ. And to ask about unity when it comes to the second and especially the fourth sense is to ask about the unity of a category: does what it means for something to be a world admit of a unified account? Whereas in the case of the second category, I don’t think we should expect a unified account, as the principles of inclusion will vary in accord with whatever kinds of entities are at issue, Heidegger is (clearly) committed to an affirmative answer to this question in the case of the fourth sense – the worldhood or worldliness of the world – as indicated by his talk in his taxonomy of the “a priori character of worldhood in general.” That leaves the third category, the very one that Heidegger privileges for using the term world. In what sense does this sense of world admit of a sense of the world?

Rather than try to answer this question directly,Footnote 27 let’s consider more closely a number of aspects of world in the third sense in order to see how a question of unity or singularity might come into view. World in the third sense designates “that ‘wherein’ a factical Dasein as such can be said to ‘live,’” which freely admits of pluralization. Such plurality is readily seen in the ease with which we differentiate among the variety of historical worlds – the world of ancient Egypt; the world of the Romans; the world of the Han Dynasty; and so on – but even more so if we consider Heidegger’s appeal to one’s own “closest (domestic) environment.” In his gloss on Heidegger’s four senses, Dreyfus warns against “beginning with my world” (Dreyfus Reference Dreyfus1991: 90), as it risks miring us in a more traditional – and problematic – conception of subjectivity. For now, I want to flout that warning. It will turn out that doing so will only reinforce the point Dreyfus wants to make in issuing it. Domestic environments can be understood as worlds. They typically involve a range of various kinds of places – rooms, yards, entryways, and so on – as well as a range of various kinds of entities – furnishings, utensils, machines, devices, and so on. Worlds in this sense have various patterns of activities on the part of those who live there: departing for work and returning at the end of the day (unless one works at home); preparing meals; sleeping and rising; leisure time; and so on. Such patterns of activity can also be divided into everyday patterns, as well as exceptional patterns, such as those for holidays and celebrations, as well as periods of crisis and disruption (illness, severe weather, power outages, and, as we’ve learned in recent years, pandemics).

These patterns are familiar to those who live within a particular domestic environment. I know my way around my house, for example, as do my wife and children (and even our dogs). I don’t have to invest much – if any – thought in how to get from one part of the house to the other, and I (often) know where things are, and even when I don’t, I typically know where to look. Someone visiting my house does not have such knowledge, although for reasons that we will get to, most people visiting my house can make pretty reasonable guesses. Domestic environments are idiosyncratic in various respects, so that we can think of certain forms of knowledge as shared by those who live in that environment that observers and visitors lack. Consider the stock example of cooking in someone else’s kitchen. Doing so typically involves far more in the way of opening and closing drawers, cabinets, and cupboards than when cooking at home. In my own kitchen, I know where things are, both in a cognitive sense (I can tell you if you ask me) and in a more embodied, practical sense in that I can reach and rummage for various things without giving it too much thought.

Roughly speaking, it makes sense to talk about a world whenever we can delineate a totality of practices that are bound together and set apart from other such totalities. My own domestic environment is one such totality; the academic world in which I also travel is another. Talk of worlds in this way resists the sweep of Occam’s Razor, as the number of worlds it makes sense to delineate is difficult to reign in. Wherever there is a factical Dasein, it makes sense to talk about that factical Dasein as living in at least a world, but most likely multiple insofar as that factical life admits of multiple dimensions or sets of patterns that are bounded off from one another. In explicating the fourth sense of world, Heidegger refers to “whatever structural wholes any special ‘worlds’ may have at the time” as modes of worldhood. We shall return to this shortly.

Worlds can be understood as totalities, but the delineation of such totalities is a complicated matter, as worlds do not divide neatly. Worlds such as my domestic environment are totalities, but they are open-ended totalities. In keeping with Heidegger’s earlier idea of telescoping layers of manifestation, my domestic world corresponds to a narrower telescoping segment that points toward, and is nested within, larger segments that bring others and a broader environment into view. That there are always telescoping layers of manifestation means that my domestic world is accessible from without. More generally, a world is accessible insofar as it includes routines, patterns, practices, and artifacts that are recognizable from the standpoint of a perspective that lies outside of it. Not everything pertaining to a world’s routines, patterns, practices, and artifacts must be immediately recognizable; accessing them can include learning what they are, how they work, and so on, as happens when we – the we who inhabit this world – come across radically unfamiliar customs and practices. Such learning is abundantly evident in the efforts needed to understand the language of the world being accessed: translation affords one avenue of access, but there is also the possibility of mastering the language in a way that surpasses translating. A corollary of Dreyfus’ rejection of the idea of a “private sphere of experience and meaning” (Dreyfus Reference Dreyfus1991: 90) is that no world is private in an essential sense. Any world no matter how idiosyncratic and exclusive – a domestic environment with only one inhabitant, say – is nonetheless accessible. Sometimes, this accessibility is assured owing to the nesting of that idiosyncratic world in a common contemporary world shared by its inhabitant and whoever is accessing it. Something like this happens anytime we meet new people or walk into a new home, although it will only be jarring to the extent that the idiosyncrasies are pronounced. But access can also be secured without such contemporaneous nesting, as happens when historians and archaeologists strive to learn more about past worlds that are not nested within any contemporary world (owing to their being no longer up and running at all ). Even the untrained eye can identify a great deal when it comes to ancient and foreign artifacts: utensils for cooking, weapons for hunting or fighting, dwelling places, various tools, and so on.

So far, we have considered, following Heidegger’s remarks about the third sense of world, examples that encourage the use of both the indefinite article (a world) and the plural (worlds). How does world in the sense we have so far explored hang together with a sense of world as singular, as, that is, involving the definite article (the world) and resisting pluralization? In his commentary, Dreyfus provides a succinct answer: “Such worlds as the business world, the child’s world, and the world of mathematics, are ‘modes’ of the total system of equipment and practices that Heidegger calls the world” (Dreyfus Reference Dreyfus1991: 90). What Dreyfus says here does not quite hew to what Heidegger actually writes about ontical worlds as modes. They are not modes of the world, but of worldhood or worldliness (Weltlichkeit): “Worldhood itself may have as its modes whatever structural wholes any special ‘worlds’ may have at the time.” If there is indeed a “total system of equipment and practices,” then it too is a world in the third, ontical sense, which means that it too – just like my own domestic environment – can be characterized ontologically in terms of worldhood. This in turn implies that such a total system would itself be a mode of worldhood in just the same way as the business world or the world of the child. Although Heidegger says that worldhood “embraces in itself the a priori character of worldhood in general,” that would not make it a mode of itself. Dreyfus’ identifying more local or regional totalities as modes of a larger totality appears to conflate the ontical with the ontological.

What Dreyfus refers to as a “total system of equipment and practices” might count as the world in the third, ontical sense, even while it would be a bit of a fudge to refer to other, “smaller” ontical worlds as modes of it. But should we be at all wary of the idea of a “total system of equipment and practices?” How is the idea of a totality – a kind of maximal totality – meant to be spelled out here and in what sense is “it” a system? At any given time, there are myriad ontical worlds up and running, so to speak, ranging from any given factical Dasein’s own domestic environment to broader, more public worlds. Many of these worlds are systematically related via permeation and by involving telescoping layers, but worlds in general do not form an obvious system even if they are accessible from other worlds. Consider as an especially pertinent analogy the variety of human languages: Different languages comprise different systems. Just what to include in such systems is a delicate matter, but for starters, we might consider a vocabulary and a grammar. English is one such system (or perhaps a family of systems, depending on how one counts dialects and the like); German is another, as is Chinese, Japanese, Swahili, Finnish, and so on. What holds for worlds in Heidegger’s third sense would appear to hold in this case (hence the pertinence of the analogy): It makes good sense to talk about languages in the plural and to use the indefinite article (English is a language). Moreover, all of them can be regarded as modes of language, in parallel to the way ontical worlds are modes of worldhood. That is, ontologically, the various human languages are on a par as all being languages, just as all the many ontical worlds are equally worlds. At the ontical level, however, there is no total system – the language – of which the many human languages are modes. There are just different languages that are all equally languages. They can be made to be systematically related to one another through translation: the different human languages are thus accessible to one another, but this can be true without there being a singular language to which all the many human languages belong. This in turn suggests that the sense of talk about the world where “world” is understood in Heidegger’s third sense is far from obvious.

Worlds are systematic totalities. If they are to be understood as modes, they are not modes of some greater systematic totality. They are instead modes or instantiations of systematicity. Systematicity is not itself a system, just as worldhood is not itself a (or the) world. If we wish, as Heidegger clearly does, to persist in referring to worldhood as a sense of world – he does, after all, mark it off as a fourth sense of the term – then it would be best glossed as lacking any kind of article, definite or indefinite, just as in EnglishFootnote 28 we leave off any kind of article, definite or indefinite, when talking about language: English, German, Chinese, and so on are languages (in the plural) and each of them instantiates or is an ontical manifestation of language. It would be a kind of category mistake to ask about the grammar and vocabulary of language, although it might be worthwhile to ask if such things as having a vocabulary or having a grammar belong essentially to language. Rather than say that various ontical worlds are modes of the world, understood as a kind of all-encompassing total system, it would be less misleading – less inviting of the charge of a category mistake – to think of these various ontical worlds as modes of world (no article).

According to the third sense of world, then, there are many ontical worlds, all of which exemplify the phenomenon of world. That is, the phenomenon of world (no article) can, via the practice of phenomenology, be brought to manifestation by reflecting in the right way on any such world. Doing so would not be a matter of cataloging the details of any particular world,Footnote 29 but delineating the structures essential to anything’s being a world. The key idea here is significance (Bedeutsamkeit): A world is primarily a structure of significance and primarily for the inhabitants of that world. As I noted at the outset, the unity of Heidegger’s account of the structure of significance – that signification has a unitary structure that every ontical world instantiates such that it is a world – means that worldhood is a unified ontological category. This is a nontrivial claim on Heidegger’s part, to say the least, but it does not amount to the unity of the world in his third sense of world; indeed, it almost encourages a disunity through the idea of a multiply-instantiated ontological structure.

In the 1924 Aristotle lectures where being-in-the-world figures prominently, Heidegger appeals to a sense of nature as the “already-there” ground for any particular human worlds, rather than another region alongside other particular worlds: “Nature is not a being-region standing alongside this world, but rather is the world itself such as it shows itself in the environing world in a definite way” (Reference MichalskiGA18: 266). And further: “Nature is the always-already-being-there of the world” (Reference MichalskiGA18: 266). Nature – the natural world – can be thus understood as the site for all the many particular human and historical worlds. Although traces of this idea of the world as the natural world (or nature) persist in SZ, the view laid out in his Aristotle lectures cannot be reconciled with much of what Heidegger says in the ensuing years. His references to nature in SZ are far more muted and qualified. He says, for example, that in using equipment, “‘Nature’ is discovered along with it by that use – the ‘Nature’ we find in natural products.” Nature is here encountered within the world and as something ready-to-hand: “The wood is a forest of timber, the mountain a quarry of rock; the river is water-power, the wind is wind ‘in the sails’. As the ‘environment’ is discovered, the ‘Nature’ thus discovered is encountered too” (SZ: 70). Furthermore, if we look just slightly beyond SZ, to his 1927 Basic Problems of Phenomenology, Heidegger is even more clear there that nature is something discovered within the world: “An example of an intraworldly entity is nature” (Reference von HerrmannGA24: 240). World here “devolves” upon nature, but as something foreign to it in the sense that nature can be as it is regardless of its having been uncovered, as “being within the world does not belong to the being of nature” (Reference von HerrmannGA24: 240). This is in sharp contrast to Dasein, since “to exist means to be in a world” (Reference von HerrmannGA24: 241). Notice, however, the indefinite article.

Despite Heidegger’s movement away from a more naturalistic conception of world – in keeping with his movement away from the category of life – SZ retains certain naturalistic elements that provide another avenue for thinking about the unity of the world. These elements appear in his discussion of world-time very late in SZ.Footnote 30 Heidegger’s exceedingly complex ideas on time and temporality are well beyond the scope of this Element. I will restrict myself here to noting that his appeal here to world-time allows us to make a sense of a unity – a sense of the world – that does not just mean a big world made up of all the smaller or “special” worlds somehow aggregated into a totality. A fundamental feature of world-time is time-reckoning, which has what Heidegger calls “astronomical and calendrical” dimensions. This astronomical and calendrical form of time-reckoning points to elements and dimensions that all worlds have in common: passing from day to night; the accumulation of such days; the marking off of those accumulations into further units; the passing of the seasons; and so on. Moreover, these patterns and markers allow for coordination across different worlds. What we might call natural world-time points toward a sense of the world as a temporal “wherein” for the myriad historical worlds there are, have been, and will be. But the world in the sense of a temporal “wherein” is not itself a further ontical world of the kind we considered above. “It” is not one more “segment” of the telescoping layers of manifestation, but something more like the principles in virtue of which telescopes have the structure they have. World-time is marked by a kind of transcendence, indeed the same kind of transcendence as Heidegger accords to the world:

That time ‘wherein’ entities within-the-world are encountered, we know as “world-time”. By reason of the ecstatico-horizonal constitution of the temporality which belongs to it, this has the same transcendence as the world itself. With the disclosedness of the world, world-time has been made public, so that temporally concernful being alongside entities within-the-world understands these entities circumspectively as encountered ‘in time’.

Note here Heidegger’s talk of “the world itself ” as what is transcendent. Dasein is always in one or more ontical world – always familiar and involved with a meaningful milieu – but Dasein transcends toward the world, which is not one more world in Heidegger’s third sense of world. What this means is that Dasein is never just in a world in the third sense; its particular world as one world among others, one world among indefinitely many possible worlds. (To think – or live out one’s life – otherwise is symptomatic of inauthenticity.) This notion of transcendence is retained and developed further in many of his writings and lectures immediately following SZ. These writings will be explored in Section 4.

2.4 Worldhood, Significance, and Publicity

From the very first lectures we considered, from 1919, wherein Heidegger tried out the verb-phrase, “es weltet,” he repeatedly characterizes the sense of “world” (along with those of “worlding” and “worldhood”) that interests him in terms of meaningfulness or significance (Bedeutsamkeit). In Chapter Three of Division One of SZ, Heidegger provides a detailed account of significance and its structure. Many of the important elements in Heidegger’s account have been touched upon or mentioned in passing since the start of Section 1, but it is important to see how they all come together in SZ.

Let’s start, more or less as Heidegger does, by considering the kinds of things we encounter and make use of in our everyday dealings. Rather than mere material objects of various dimensions and with various properties – what Heidegger refers to here as simply things – we encounter what he refers to as equipment: pens, paper, laptops, coffee mugs, screwdrivers, backpacks, lawnmowers, and so on. Importantly, Heidegger says that “taken strictly, there ‘is’ no such thing as an equipment” (SZ: 68). This is evident already in the barest characterization of any item of equipment, namely, that it is something-for-something: The pen is for writing, the backpack is for holding my stuff for the camping trip, the coffee mug is for holding my coffee, and so on. Considering any one item – or kind – of equipment leads us toward other things: other items of equipment (consider the interconnection between hammers and nails, screws and screwdrivers, and so on), but also various ranges of tasks and activities (pounding in nails, drinking coffee, jotting down a note), along with a variety of projects (building something, writing an article, getting away from it all). Holding among this constellation of equipment, tasks, and projects are relations of reference: a hammer refers to nails, as well as to hammering, and fastening pieces of wood together, building a house or piece of furniture, and so on. These are relations that Heidegger designates as with-which, in-order-to, and toward-which: a hammer is something with-which one hammers in nails, in-order-to fasten pieces of wood, toward the building of something.

Implicit in all of these relations of reference is, of course, Dasein: what establishes and sustains these constellations of equipment, tasks, purposes, and projects is their being understood and put to use in those ways. Concernful Dasein is the animating principle of these various contexts of equipment: what makes a hammer a hammer lies in its being used as a hammer; divorced from – or divested of – that use, the hammer is no longer equipment, but only a mere thing. Heidegger makes this animating principle explicit in the final referential relation that holds all the other relations together – for-the-sake-of – which refers explicitly to Dasein’s self-understanding, what it takes itself to be up to or doing in putting equipment to use in various ways. Heidegger calls the for-the-sake-of the “primary ‘towards-which,’” which “pertains to the being of Dasein, for which, in its being, that very being is essentially an issue” (SZ: 84). All the other referential relations are subordinate to – and dependent upon – this principal relation. Equipment is constituted by its involvement in this web of relations – involved in these ways and for these purposes – and equipment is thereby, as Heidegger puts it, “freed” for this involvement through – and in relation to – Dasein’s concernful activity. We can think of this talk of freeing as operative at different levels: When I head downstairs to the kitchen for a cup of coffee, my trusty coffee mug stands out, along with the coffee pot, as most salient for what I am up to; in that way, it is freed for its involvement in my drinking a cup of coffee, in contrast to the many other things that populate my kitchen but mostly lurk in the background as I pour myself a cup. But this kind of episodic freeing does not stand alone. When I walk into the kitchen to get a cup of coffee, I am not starting from scratch in terms of what might be put to use for my purposes.Footnote 31 When I reach for the cup, I am not thereby making it be a coffee cup, as though for the first time; rather, my actions are determined in relation to a prior freeing up of meaningful items of equipment that are involved in various activities. Freeing up the cup is not something I do on that occasion except in the sense of its now standing out that it has been so freed.

Coffee cups are involved in the making and consuming of coffee. As such they refer back ultimately to coffee drinkers, those of us who enjoy such beverages. Being a coffee drinker is a role that any of us can take up, and in doing so, I understand myself as having that role, as being, among many other things, a coffee drinker. As so assigned, different aspects of my environment stand out as salient in ways that they largely do not for those who do not drink coffee: coffee beans, grinders, mugs, and so on all become relevant in virtue of my occupying that role. Heidegger calls this way of occupying a role assigning: I assign myself the role of being a coffee drinker. The idea of assignment – in contrast with involvement – hangs together with the special status of the for-the-sake-of. It is not up to the coffee mug to play the role it does in our everyday lives, but I can decide to give up coffee, either because I’ve lost the taste for it or my doctor urged me to do so or for some other reason.

Heidegger’s analysis of the structure of significance in terms of involvements and assignments leads ultimately to the phenomenon of world:

That wherein Dasein understands itself beforehand in the mode of assigning itself is that for which it has let entities be encountered beforehand. The “wherein” of an act of understanding which assigns or refers itself, is that for which one lets entities be encountered in the kind of being that belongs to involvements and this “wherein” is the phenomenon of world.

To which he adds: “And the structure of that to which Dasein assigns itself is what makes up the worldhood of the world” (SZ: 86).