1 Introduction

It seems like there’s a kind of national conversation going on right now about those who are paid to protect us, who sometimes end up inflicting lethal harm upon us. But for me, this conversation is old, and I’m sure for many of you the conversation is quite old. It’s the cameras that are new. It’s not the violence that’s new.

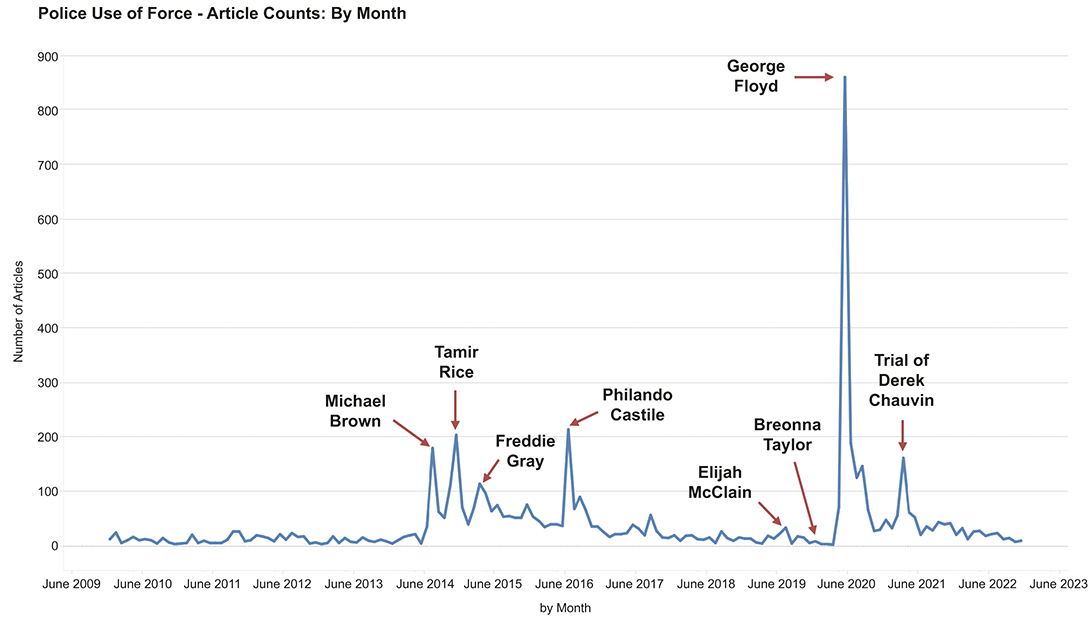

In 2014, and again in 2020, US news media lurched their attention to the issue of police use of deadly force, specifically against unarmed Black people. A count of New York Times articles, for example, shows that in the decade before 2014, news coverage of the issue was consistently low, averaging just over 100 articles per year. In August 2014, however, coverage surged following the death of Michael Brown, an unarmed Black eighteen-year-old man who was shot and killed by a police officer in Ferguson, MO, and whose body was left uncovered in the street for hours. The New York Times published 179 articles related to police use of deadly force that month alone, and 705 articles in total that year. Coverage in the Times and other news outlets stayed high for a couple years but then declined to pre-2014 levels. In 2020, though, coverage spiked again following the gruesome murder of George Floyd, a forty-six-year-old unarmed Black man killed in Minneapolis, MN, on May 25 as a police officer kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes, while bystanders watched. In June 2020 alone, the Times article count was 860, with 1,525 articles that year. Both Michael Brown’s and George Floyd’s stories were instances of what past work has labeled “media storms,” formally defined as a sudden, high-level surge of news coverage for at least a week, but better understood as the type of news coverage around an item that is so sudden and so pervasive that even people not paying attention to the news have heard about the story.

The much lower levels of news coverage about police use of deadly force in the time periods before, between, and after the media storms surrounding Michael Brown’s and George Floyd’s deaths did not mean there were fewer people (or fewer Black people) in the US being killed by police in those periods. Although perfect data on lethal police encounters do not exist, available data collected by the Fatal Encounters collectiveFootnote 1 and The Washington PostFootnote 2 suggest that more than 1,000 people are killed in America each year during encounters with police – with Black people representing a near-consistent 25% of the fatalities. (Accounting for overall representation in the US, Black people are 3.23 times more likely to be killed by police compared to White people (Schwartz and Jahn Reference Schwartz and Jahn2020)). Since 2010 specifically, the estimated yearly number of people killed by police has varied from about 1,300 to 2,100, with Black people representing 27% of these fatalities.Footnote 3 Together, these statistics suggest that each week of low media coverage hides a week in which, on average, police in the US kill between six and eleven Black people.

In this way, news media not only reflect reality but also shape our perception of it. Although it is impossible for news outlets to cover all the policy problems in the world all the time, in moments when an ongoing problem fails to make the news, this inattention is a form of misrepresentation. As Lawrence says, the news media capture “an arena of struggle over the meaning of events, the existence of problems, and the search for solutions” (Reference Lawrence2022: 23). Thus, when a media storm does erupt, it shines a spotlight on an otherwise underattended problem.

Yet despite the significance of media storms, no research to date has identified the precise factors needed to prompt a media storm. For example, Michael Brown and George Floyd became household names because of the media storms that followed their deaths. But if their deaths did not mark any changes in the underlying problem of police use of deadly force, then why did their deaths spark media storms when so many other cases do not? Put more broadly, what conditions are required for a media storm to occur?

This question is important because media storms are important. When a media storm is underway, the news agendas of various news outlets become more congruent, sending people a more unified signal about what to pay attention to (Gruszczynski Reference Gruszczynski2020). This unified signal is effective. For instance, news coverage has a statistically stronger effect on Congressional attention when that coverage occurs as part of a media storm (Walgrave et al. Reference Walgrave, Boydstun, Vliegenthart and Hardy2017). And anecdotally, there is much evidence to suggest that media storms can serve as windows of opportunity for societal change. As just one example of many, consider the media storm surrounding the sexual abuse of children by Catholic priests and the church’s systemic cover-up of these instances of abuse. This media storm was initiated by a series of Boston Globe articles published in 2002, following months of investigative journalism. Of the thousands of cases of alleged sexual assault by Catholic priests in the US in the preceding four decades, less than 0.5% occurred in 2002 (the year the story broke). Yet 32% of the survivors of these abuses came forward in 2002 during, and in the wake of, the media storm (Boydstun Reference Boydstun2013). This data point suggests that by highlighting the underlying problem of sexual assault at such a high volume of attention, the media storm helped destigmatize the act of making an allegation, thereby encouraging more survivors to come forward. Increased allegations acted as a catalyst for policy changes, which in turn prompted more media coverage, creating a positive feedback loop of media attention and societal change. Because media storms are important, it is important to understand when and why they happen.

In this Element, we investigate the conditions that tend to mark, perhaps even portend, a media storm. From these markers, we can infer a set of necessary conditions under which a media storm will erupt. We use a mixed-methods approach, starting with a rich set of eighty-six in-depth case studies of events that did (and didn’t) become media storms in policy areas spanning police use of deadly force to water quality, immigration policy to airplane safety, and many more in between. Quantitative analysis allows us to validate which items were media storms and which were not, and qualitative analysis allows us to identify the common factors that differentiate events that became media storms from those that did not. We do not offer a predictive model of media storms here, per se; indeed, our conclusion is that they are largely unpredictable because their component parts are so hard to control or anticipate. Rather, we identify the correlates of media storms – the combination of factors that are collectively present in the case of media storms and not collectively present when media storms do not materialize. The result is a theorized set of conditions that are necessary for a media storm to occur.

We develop and apply our model in the context of national media storms in the US news media, as an important example of a competitive media marketplace. Yet we hope our model will be useful in other contexts as well (see our discussion on Media Storms of Different Scope in Section 2). Media storms are phenomena familiar to anyone living in a democratic media system – and probably nondemocratic media systems, too. Examples from other nations include, in Portugal, the 2007 disappearance of three-year-old Madeleine McCann from a holiday apartment where she was staying with her family while on vacation from England, with the McCann family serving as a Patient Zero target of widespread trolling on the newly released Twitter social media platform, then just a year old; in Germany, the 2016 New Year’s Eve sexual assaults in Cologne and other cities, with this media storm prompting the German Parliament to pass the “No Means No” law that among other things lowered the bar of non-consent from actively defending oneself to verbally saying “no” and made it easier to deport a migrant convicted of a sex crime; and in the UK, the 2020/2021 “partygate” scandal about government and Conservative Party gatherings in violation of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, with this media storm adding to the forces that prompted the then prime minister Boris Johnson to resign. Understanding the necessary conditions of media storms is important in every geographical and political context. As we discuss in Section 7, we expect our model would apply comparatively, at least to other democratic media systems, although with key conditioning factors such as the competitiveness of the media system and the party structure of the government.

In Section 2, we give more definition to and background about the concept of “media storms.” In Section 3, we recount the methods we used to identify the factors that demarcate events that prompt media storms from those that do not. We then turn to our main discussion in Sections 4–6, where we use fire as an analogy to discuss the three core elements that we argue are necessary conditions for media storms.Footnote 4 In the case of real fires, the “fire triangle” is a simple model designed to help the average person understand the conditions needed to create most fires, and its most well-known application is in the prevention of wildfires (Ballard et al. 2012). The fire triangle is made up of three ingredients: heat, fuel, and oxygen (Bear Reference Bear2019).Footnote 5 We borrow this triangle imagery to offer a model of the ingredients needed to trigger media storms (as illustrated in Figure 1): the “heat” of the newsworthiness of an event, the “fuel” of historical and current political landscape against which that event is (or is not) relevant and cognitively accessible, and the “oxygen” of available media agenda space as well as amplifying attention the event receives beyond the traditional news media (e.g., from politicians and the public).Footnote 6 We posit that only a news item that has high levels of all three ingredients will prompt a media storm.Footnote 7 In other words, strong levels of heat, fuel, and oxygen are individually necessary conditions on their own, but only in combination are they jointly sufficient to prompt a media storm. Finally, in Section 7, we close by highlighting some of the very real effects of media storms on public opinion and public policy in recent years, underscoring the importance of understanding the necessary conditions of future media storms.

Figure 1 The media storm fire triangle model

Figure 1Long description

The fire triangle model is composed of heat (event), fuel (issue landscape), and oxygen (amplification and agenda capacity) in mutually-reinforcing relationships with one another.

In short, we argue that media storms are not easily predictable; it is not simply the case that when an extraordinary event occurs, media respond with extraordinary levels of coverage. Media storms also do not simply happen; they are the product of human beings – news editors, news consumers, policymakers, policy activists, and many others – making decisions about which events and issues to prioritize. The result of this complex system of human attention allocation is that media storms occur only when (1) the right event (i.e., perceived to be highly newsworthy) occurs, (2) at the right time (when there is available media agenda space and when previous and current items in the news offer the story a relevant hook), and (3) gets talked about by the right people (amplifying the story beyond the mainstream news). But when the political stars align and a media storm erupts, it can prompt lasting effects, establishing a new media equilibrium – and, often, a new policy equilibrium – that will likely hold until the next media storm in that policy space occurs.

2 What We Know About Media Storms

Before we turn to addressing our core question about the necessary conditions of media storms, we need to lay some groundwork for the concept of media storms and how they arise from the journalistic news generation process. Let’s start with the definition. Boydstun, Hardy, and Walgrave define a “media storm” as “a sudden surge in news coverage of an item, producing high attention for a sustained period” (Reference Boydstun, Hardy and Walgrave2014: 509). Their concept of a media storm builds on prior work surrounding media dynamics, including examination of “media hypes,” which are functionally synonymous with “media storms” (e.g., Vasterman Reference Vasterman2005; Wien and Elmelund-Præstekær Reference Wien and Elmelund-Præstekær2009). In essence, media storms are instances where a key event occurs in such a way as to draw competing and imitating coverage from multiple news organizations, becoming a “self-reinforcing news wave” (Vasterman Reference Vasterman2005). This line of research is unified by the core phenomenon of news coverage exploding around an unfolding news item, such that the average person in that news market is aware of the item even if they themselves are not carefully tracking the news.

Empirically, Boydstun, Hardy, and Walgrave (Reference Boydstun, Hardy and Walgrave2014) define a media storm as occurring when news coverage of an item meets three criteria: (1) a sudden surge in news coverage, (2) at a very high level, (3) lasting for at least a week.Footnote 8 In addition to these three criteria, they posit a fourth criterion, saying, “we conceptualize true media storms as being those that meet our three formal criteria and that register as such across multiple news outlets in a given media system” (Reference Boydstun, Hardy and Walgrave2014: 512). True media storms at the national level, then, are those that erupt, in part, from competing news outlets clamoring to get the next fresh take on an unfolding storyline. In practice, it appears that most, if not all, events that reach media storm status in one national news outlet also satisfy this fourth criterion of capturing the attention of multiple outlets. For example, Litterer, Jurgens, and Card (Reference Litterer, Jurgens, Card, Bouamor, Pino and Bali2023) find that the mean number of US news outlets covering a typical storm was seventy-six (the median was seventy-four). One inference from this finding is that, at least in terms of national news outlets, a media storm that erupts in one news outlet is almost certainly erupting across that portion of the media ecosystem.

Importantly, media storms do not just happen. As we will discuss more in Section 5, media storms are the results of political actors of many stripes making decisions about how to spend their attention.

How Do Media Storms Unfold?

Although research to date does not identify the specific conditions under which a media storm is likely to erupt, past work does offer insight into the dynamic patterns observed in media storms as they unfold, as well as the journalistic mechanisms that underly them. Scholars have discussed the notion of media storm dynamics (although not by that name) for decades. For example, we know that some policy problems tend to follow what Downs (Reference Downs1972) calls the “issue attention cycle.”Footnote 9 For these problems, attention cycles through different phases: first, a period of little or no attention to the policy problem, even though the problem is ongoing and in need of attention; second, a sudden discovery of the problem by the media and the public, accompanied by a sense of urgency to address it; third, a realization of how complex and hard to solve the problem is; fourth, a gradual decline in public interest in the problem; and fifth, a period of “post-problem” inattention that feeds back into the first stage of the next cycle. Other work adds texture to the notion of an issue attention cycle. Whereas Downs talks about the second stage of the cycle as a period of positive enthusiastic problem-solving, for instance, Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1960) talks about the kind of cases where the sudden “discovery” of a problem is met with a more negative, accusation-based form of urgency.

Common across these and other scholars is the notion that the public agenda, the media agenda, and the policymaking agenda all move through cycles of attention to ongoing policy problems. In each case, it takes a confluence of multiple forces to produce major agenda overhaul. Focusing on the policymaking process, Kingdon offers a “multiple streams” model to explain the interconnected factors that need to align in order for policy change to occur. He explains that a “window of opportunity” for policy change to occur opens only when a policy problem (1) is identified and defined as a problem by the media, citizens, issue groups, and so on (the “problem stream”), and (2) potential policy solutions are proposed (the “policy stream”), (3) in the context of a hospitable political climate (the “politics stream”). One key contribution of Kingdon’s policy streams model, also consistent with past research on media attention, is that eruptions of policy change and media attention are highly serendipitous, and thus very difficult to predict.

Past research also reveals several things about the nature and dynamics of media storms once they begin. For example, examining front-page coverage of the New York Times in the US and De Standaard in Belgium, Boydstun, Hardy, and Walgrave (Reference Boydstun, Hardy and Walgrave2014) show that media storm coverage is a fundamentally different kind of dynamic species than non-storm coverage. As predicted by the punctuated equilibrium model of policy agenda dynamics (Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones2009), non-storm news coverage moves in fits and starts, fluctuating between almost no change (equilibria) and sudden but short-lived bursts of change (punctuations). But media storm coverage is quite different. Unlike other bursts of change, media storms, by definition, erupt into a much higher level of news coverage and last for a longer period. But, once in storm mode, media attention tends to change much more gradually, fluctuating moderately around the high level of attention before dying down more slowly than the staccato of non-storm punctuations (Litterer, Jurgens, and Card Reference Litterer, Jurgens, Card, Bouamor, Pino and Bali2023).

The pattern by which media storms erupt matches the power law dynamics of other tipping point scenarios in the context of complex systems, including avalanches, financial crashes, and fashion fads (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1978). In these scenarios and in the case of media storms, a series of independent but mutually reinforcing factors combine to build momentum, increasing the likelihood that the next action will be one that reinforces rather than counteracts the trend. The result in the case of a media storm tends to be an initial low level of news coverage that suddenly surges into a flurry of attention before gradually dying back down.

As for the duration of media storms, Litterer, Jurgens, and Card (Reference Litterer, Jurgens, Card, Bouamor, Pino and Bali2023) find that the typical media storm peaks quite early (in the first few days), and then declines gradually over time, usually lasting at least two weeks both in terms of total amount of coverage and in the number of outlets covering it each day. They find this pattern to be especially true for storms precipitated by unexpected events, such as a celebrity death. At the same time, a subset of media storms in their study were more predictable, such as the outcome of a court trial, where there was much more news coverage laying the groundwork in anticipation of the main event, resulting in a more gradual incline in coverage.

Media storm dynamics are born in part through journalistic patterns of news coverage. Boydstun (Reference Boydstun2013) explains how media storms erupt within the “police” model of news generation coined by earlier authors (e.g., Bennett Reference Bennett2003; Zaller Reference Zaller2003). Table 1 summarizes Boydstun’s alarm/patrol hybrid model of news generation. News outlets often operate in “patrol” mode, whereby for any “neighborhood” surrounding a given issue or topic (e.g., immigration, crime, health care, sports, weather patterns, etc.) reporters assigned to that beat drive up and down the figurative streets of that neighborhood and report on anything important they find. At other times, news outlets operate in “alarm” mode, waiting back at the figurative police station until a major event, a whistleblower, or something else triggers an “alarm” that alerts them to a newsworthy item. Of course, there are many one-off stories that result from neither one of these styles of reporting. But of key interest here, media storms (highlighted in the top-left quadrant of Table 1) occur when journalists shift from alarm mode to patrol mode, or vice versa. For example, in 2005 news outlets raced to cover the alarm of Hurricane Katrina but then shifted into patrol mode, in many cases embedding reporters in the area for weeks. In patrol mode, these reporters investigated back-alley items such as racial inequities in housing and inefficiencies in FEMA’s administration. These patrol-based stories helped to amplify and sustain news coverage following the hurricane, producing the high and prolonged coverage necessary to qualify as a media storm (Haider-Markel, Delehanty, and Beverlin Reference Haider-Markel, Delehanty and Beverlin2007).

An example of the flip case, where news outlets move from patrol mode to alarm mode, was the aforementioned Catholic priest abuse scandal. The scandal broke not because of any sudden “alarm” event but rather because journalists at the Boston Globe (specifically the Spotlight team of journalists, highlighted in the 2015 movie of the same name) had spent months patrolling the figurative neighborhood of allegations of sexual abuse by Catholic priests and indications of institutional-level coverup by the Catholic church, before publishing their findings in a series of news articles. These news articles, in turn, served as an alarm for the rest of the media system, and other news outlets raced to cover the story, prompting a media storm (Boydstun Reference Boydstun2013). Thus, the alarm/patrol hybrid model helps explain the journalistic forces that combine to produce media storms.

Table 1Long description

When patrol-mode reporting (where news outlets dig into the details of a story, looking for new aspects of the story to cover) combines with alarm-mode reporting (where news outlets rush to cover a hot new story), the result is a media storm. Alarm-mode reporting alone results in a momentary media surge in news coverage but not at a high enough level and/or for long enough to qualify as a media storm. Patrol-mode reporting alone results in low-level sustained coverage or high-level sustained coverage. Finally, reporting in neither patrol mode nor alarm mode produces low-level coverage for a brief period.

Media Storms of Different Scope

Past empirical work on media storms has been conducted mostly within the specific parameters of individual national news outlets (e.g., the New York Times). But past research also makes clear that the concept of media storms could be studied in contexts that might encourage researchers to adjust one or more of these parameters (i.e., expanding beyond a single source, shifting from a national level to a different level, and/or considering sources beyond traditional news). We mention these three parameters in the hopes that readers will keep them in mind in the sections that follow as we examine the necessary conditions of media storms. Whether the established findings about media storms – including those we present here – would apply under different parameter definitions of a media storm is an open question, one we invite the reader to consider.

First, media storms could be studied across the scope of a news media marketplace. That is, scholars could expand their definition of media storms to those news items that meet the three criteria from Boydstun, Hardy, and Walgrave (Reference Boydstun, Hardy and Walgrave2014) – a sudden increase in attention, a very high level of attention, and lasting for an extended time – and their fourth criterion of needing to meet these three thresholds across a certain number of news sources. The true notion of a media storm, as we and other scholars have envisioned it, is a dramatic surge in coverage that ripples through the entire national news media marketplace (and beyond). Again, work by Litterer, Jurgens, and Card (Reference Litterer, Jurgens, Card, Bouamor, Pino and Bali2023) suggests that a media storm in one national news outlet generally means a media storm across news outlets nationwide. In the case study findings we introduce in Section 3 and discuss in Section 6, we use data from the five most prominent US newspapers (Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post), and each case that met our criteria of a media storm overall also presented as a media storm within each of the five outlets. While we expect that the findings we present here would hold in a broader study that encapsulates the entire national marketplace (newspapers, magazines, TV, radio), we cannot know for sure.

Second, although media storms as defined by Boydstun, Hardy, and Walgrave (Reference Boydstun, Hardy and Walgrave2014) are those instances where national media coverage explodes around a news item, the concept of media storms could be applied geographically either more broadly or more narrowly – or to non-geographic spaces, such as a Reddit community. For example, the 2023 escalation of the conflict between Israel and Hamas likely met the criteria of a media storm as on a global scale. Other examples of global media storms might include the reactor explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine in 1986 or the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the US in 2001. Yet, to date, no studies of media storms have used as an empirical criterion the spread of the story across news media marketplaces around the world. There is important work, however, on the phenomenon of a media storm that begins local and spreads across a national media marketplace; Usher and Hagman (Reference Nik and Hagman2025) provide a meticulous case study of the media storm that began local but then caught fire nationally surrounding Darren Bailey, a Republican Illinois State Senator who in 2020 sued the Illinois Governor for the stay-at-home order put in place during the pandemic. At the other end of the geographical spectrum, no scholarship that we know of has examined the questions of media storms we tackle here from an exclusively local perspective, focused on media storms that erupt at (but stay within) the local or regional level.Footnote 10 Such an approach would be useful in examining the dynamic news signals that people in a particular area receive. In addition to knowing about any national (and global) media storms that occur, people are also aware – perhaps even more acutely aware – of media storms at the local level, for example involving local government scandal, a contentious local election, the firing of a beloved high school principal, and so on. In the spring of 2023, for example, the close-knit community of Davis, CA, was jolted by a string of stabbing attacks that killed two beloved members of the community and severely wounded a third. Few people outside of Davis would have heard this news (which received a single article in the New York Times), but the stabbings certainly caused a media storm in the local media system, occupying near-daily headline space in the local and regional newspapers and on the regional network television stations, as well as in local groups on social media networks like Nextdoor and Facebook. In the case of global and local media storms (as well as media storms in a non-geographic space), we have no strong theoretical grounding on which to assume that existing research about media storms would (or would not) apply. The theories and findings we put forward here might generalize to these other contexts, but they also might not, underscoring the importance of future work in these areas.

Third, the established work on media storms treats social media coverage as positive feedback for traditional news coverage and thus defines media storms strictly in terms of newspaper, television, and online (e.g., Politico.com) journalism-based coverage of a news item. Following this line of conceptualization, in this Element we categorize social media coverage as part of the “oxygen” required to ignite and sustain a media storm in mainstream news. But the concept of a media storm can be applied to social media itself, with attention on social media being the primary phenomenon of interest and attention in mainstream news helping to amplify it (Vasterman et al. Reference Vasterman, Auch and Beyer2018). As a whimsical example, in 2015 a picture of a striped dress went viral on social media, with people divided in their perceptions of whether the colors of the dress were black and blue or white and gold. This debate spilled over into traditional news as well, with sources like the New York Times publishing stories first about the social media buzz and then follow-up articles such as science-based reporting explaining the difference in color perceptions (Fleur Reference Fleur2015), but it failed to become a media storm in the traditional news. Yet it undoubtedly constituted a media storm in the context of social media. Future research could include or focus exclusively on media storms that erupt on social media, whether or not they also meet the criteria of a media storm in the traditional news. Another question for future research is whether less serious media storms that erupt on social media, such as “the dress” debate in 2015, or the “Barbenheimer” trend of pairing the Barbie and Oppenheimer movies in the summer of 2023, are more likely to occur when there is a lull in the traditional news cycle. Again, we don’t necessarily expect that the established findings (including those we present here) would hold if applied to media storms on social media.

In all the potential modifications we have discussed here, and in others we have not explicitly called out, we can imagine researchers making theory-driven decisions to adjust the empirical criteria of a media storm as needed for different contexts.

Media Storms Matter

Finally, we know from past research that media storms matter. Using Google search data, for example, Boydstun, Hardy, and Walgrave (Reference Boydstun, Hardy and Walgrave2014) show that the public pays quick attention – and a lot of it – to news items at the heart of media storms, compared to paying much less (if any) attention to news items that, while substantively similar, do not erupt into media storms. In follow up work, Walgrave and colleagues (Reference Walgrave, Boydstun, Vliegenthart and Hardy2017) show that a one-story increase in news coverage around a policy issue has a significantly stronger effect on Congressional attention to that issue if the story occurs as part of a media storm rather than outside of a storm. And a key finding from research on agenda setting (including from Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1960) and Downs (Reference Downs1972), mentioned earlier) is that when media and public attention turns to an issue, even a short period of high attention can be enough to produce some kind of change, akin to Kingdon’s “windows of opportunity” in the policy realm (Reference Kingdon2010).

In the case of news coverage, media storms indeed provide “windows of opportunity” for changes in public opinion, policy, and cultural norms, as we discuss more in Section 7. These windows of opportunity are likely facilitated not only by the sheer volume of news coverage during a media storm but also because of the aforementioned finding from Gruszczynski (Reference Gruszczynski2020) that during a media storm the individual news agenda of outlets across the media system become more congruent. Another mechanism that might help pry open these windows is how news outlets talk about, or frame, an event or issue while in media storm mode. For instance, Baumgartner, De Boef, and Boydstun (Reference Baumgartner, De Boef and Boydstun2008) document the dramatic shift in media framing of the death penalty that occurred during media storms in the 1990s, changing from a predominant narrative of crime and punishment to one of fairness and innocence. This finding suggests that media storms coincide with changes in issue framing, as news outlets clamor to establish fresh perspectives and angles on the same topic in a competitive news marketplace, thereby expanding the norms of how that issue is discussed.

In thinking about the effects of media storms, it is important to note that events that ignite a media storm are not always spontaneous or “accidental,” as in the case of most media attention around the issue of police use of deadly force (Lawrence Reference Lawrence2022). Many media storm events are “institutional,” coordinated by political elites as planned or staged events. Examples of these types of media storm events are UN climate speeches from important leaders or arguments in front of the Supreme Court. However, the accidental or spontaneous events can disrupt news outlets’ status quo and make even bigger waves than the anticipated events, reshaping journalistic patterns in the process. As Lawrence writes, “some accidental events become the centerpieces of struggles to designate and define public problems, as other groups vie to provide journalists with frames and claims to define these events. As journalists try to make sense of troubling news events, news routines may extend to underutilized news sources and marginalized perspectives” (Lawrence Reference Lawrence2022: 22).

Although these findings help us understand what media storms are, how and why they unfold, and what effects they can have, the question remains: What are the conditions needed to prompt a media storm in the first place? Is the media landscape a “survival of the fittest” environment, where the events that trigger media storms are simply the most newsworthy items? Or is there more involved?

3 Methodology: Identifying the Correlates of Media Storms

Previous scholarship has laid strong groundwork for exploring how and when societal problems come to be spotlighted in the news. In a parallel to the George Floyd case, Lawrence (Reference Lawrence2022) examines the media storm surrounding the 1991 brutal beating of Rodney King by police, juxtaposing other contemporary cases that received little or no media coverage. Lawrence explains that journalists covering these stories act as “mediators” in their choice of stories to focus on, and she links these decisions to the considerable constraints that govern and generally limit media coverage of police use of force. Informational constraints, in particular, can be mitigated when video of the incident is available, as when a bystander on a balcony videotaped police officers brutally beating Rodney King (Lawrence Reference Lawrence2022).

In this light, part of the explanation of why one event or story gets highlighted above others might seem obvious. In the case of George Floyd’s murder, bystander Darnella Frazier used her cellphone to capture video of the shocking cruelty of a White police officer kneeling on Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and forty-six seconds as Floyd struggled to breathe, called out to his deceased mother, and ultimately lost consciousness and died (Arango, Dewan, and Bogel-Burroughs Reference Arango, Dewan and Bogel-Burroughs2021). In Michael Brown’s case, however, there was no video. This discrepancy alone suggests that the explanation of why some events catch the media’s attention, while others don’t, is more complex than the event itself or even the presence or absence of graphic video evidence.

What, then, are the conditions of, or surrounding, an event that tend to herald a media storm? We tackled this question using a mixed methodological approach. We started by examining a massive original dataset of two decades’ worth of news coverage of six policy issues (capital punishment, climate change, gun control, immigration, same-sex marriage, and smoking/tobacco) that we compiled for a different project, totaling some 100,000 news articles (Card et al. Reference Card, Boydstun, Gross, Resnik and Smith2015). Using this dataset, we identified all media storms using three quantitative criteria in line with past research: an increase in coverage of at least 150%, occupying a large portion of the media agenda,Footnote 11 and maintaining that level of coverage for at least a week. As for the fourth criterion (coverage across multiple news outlets), in practice every one of the media storms we identified using the other three criteria also met this fourth criterion, with high levels of coverage spanning the different news outlets in the dataset. In all, across twenty years of news coverage of six different issues, these criteria yielded forty-four media storms. A qualitative deep dive revealed that many of these storms surrounded events that were predictably newsworthy (e.g., the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012), but it also revealed other events that in isolation were not nearly as newsworthy, at least at a national level (e.g., state legislative efforts to pass new gun control laws in Connecticut). These qualitative findings offered face validity to the idea that the newsworthiness of an event is not alone sufficient to predict whether a media storm will occur.

Next, we employed the help of many thoughtful and talented undergraduate research assistants with a diverse array of background experiences to identify and compare events that prompted media storms with comparable events that did not prompt media storms. We used the following structured methodology:

1. We started by brainstorming major news items that seemed likely to have met the empirical criteria of a media storm (a sudden surge in coverage, at a very high level, lasting for at least a week), based on internet searching as well as our own memories and conversations with others. We were careful in this stage not to share with the research team the list of verified media storms from the earlier dataset of news coverage across six issues, but the team brainstormed several media storms that were also included in that list. The result of this brainstorming process: eighty-one potential media storm events.

To check whether each potential media storm met the quantitative criteria, we used the ProQuest US Major Dailies archive, which chronicles coverage (including online coverage) from five major US newspapers (Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post). We applied the established criterion of a sudden increase in attention (Boydstun, Hardy, and Walgrave Reference Boydstun, Hardy and Walgrave2014) by requiring an increase in coverage of 150% or more from the pre-storm week to the week where the candidate storm erupted. For the second criterion of a high volume of coverage, we required the first week of the storm to have at least 100 news articles (meaning roughly 3 articles a day, on average, for each of the five major national newspapers in the database).Footnote 12 For the duration criterion, we required that the level of coverage stay high throughout at least the first week. Again, in practice, all items that met these three media storm criteria also met the fourth, with high levels of coverage across the news outlets in the US Major Dailies archive. Our online appendix contains the keyword search strings we used. Of the eighty-one potential media storms we had brainstormed, seventy-five turned out to satisfy the quantitative media storm criteria.

2. For each validated media storm event, we did our best to find a parallel event with roughly the same qualitative characteristics as the media storm event but where we estimated the parallel event did not become a media storm – a task akin to finding the dog that did not bark. Some storms (e.g., the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, or the 2020 global pandemic) were so unparalleled that there simply was no counterpart non-storm event in the modern era. Other cases were difficult to pair for other reasons. For instance, Rose McGowan had long voiced to friends her account of being sexually assaulted by Harvey Weinstein but did not make her accusations public until 2017 when the #MeToo media storm ignited around sexual assault and harassment. We simply could not find a parallel non-storm event (i.e., a celebrity of McGowan’s status making public accusations of sexual assault before the #MeToo movement took off), presumably because prior to the #MeToo movement, even celebrities of her status did not risk making public accusations. Of the seventy-five verified media storm events, we were able to match forty-three with parallel non-storm counterparts (eighty-six events in all).

3. For each media storm and non-storm event, we qualitatively evaluated and then documented the attributes of the event itself, as well as the surrounding context. This lengthy list of events and their attributes revealed three conditions, or elements, that were consistently present to a strong degree in the case of every media storm, but at least one of which was weak or missing from each non-storm event. We label these three elements “heat,” “fuel,” and “oxygen,” as described more in Sections 4–6.

4. For each storm and non-storm event, we rated the event according to each element (heat, fuel, and oxygen) from Very Low to Very High based on comprehensive research, including reading news articles, social media posts, and Google Trends data, where applicable.

○ Heat: The newsworthiness of the event, including factors like scope of impact, shock value, and availability of evidence.

○ Fuel: The historical and current political, cultural, and economic context that amplifies the event’s relevance.

○ Oxygen: The amount of available media agenda space, as well as attention and amplification from beyond traditional news sources, such as social media, politicians, and activist groups.

While our decisions about how high or low each element was in each case are inherently subjective, we used a set of guidelines to standardize our categorizations (see online appendix). For example, for the heat of an event to be rated as “Very High,” the event needed to have a high degree of newsworthiness (see Sidebar in the Section 6, Heat) and compelling photographic/video evidence to assist in virality. “Very High” fuel required that the event be one that was already salient for the average American and could be easily framed in a way to hook into a salient touchpoint. “Very High” oxygen required available media agenda space (i.e., the absence of a major competing media storm) and significant amplification of the event by at least three distinct types of non-news sources (e.g., celebrities, politicians, state or federal legislation, international organizations, public protests, viral hashtags, etc.), such that an average person not tuned into the traditional news but paying attention to other channels of communication like social media would likely hear about it.

Our online appendix showcases eighteen of these pairs of media storm versus non-storm events (labeled in each header with the year it was most prominent in the news), with categorizations and brief descriptions of the heat, fuel, and oxygen for each, along with the following empirics:

The week of the highest level of news coverage for the event

Number of news stories in the week prior to the week of highest coverage

Number of news stories in the week of highest coverage

Number of news stories in the month of highest coverage

We also describe key outcomes (e.g., policy shifts) that occurred at least in part because of the media storm within each pair. We feature four of these eighteen comparisons in Figure 2 (Israel–Hamas war versus Sudan war), Figure 3 (Greta Thunberg versus Mari Copeny), Figure 4 (H.R. 4437 versus Secure Fence Act), and Figure 5 (Titan submersible disaster versus Messenia migrant disaster).

Figure 2 Israel–Hamas war versus Sudan war

Figure 3 Greta Thunberg versus Mari Copeny

Figure 4 H.R. 4437 versus Secure Fence Act

Figure 5aLong description

The Titan submersible disaster prompted a media storm, with high or very high levels of heat, fuel, and oxygen.

Figure 5bLong description

The Messenia migrant disaster did not prompt a media storm, with low to medium levels of heat, fuel, and oxygen.

Figure 5 Titan submersible disaster versus Messenia migrant disaster

Readers may surely quibble with some of the subjective evaluations we have made in selecting and categorizing the items in each comparison. We welcome these quibbles as part of the valuable discourse to be gained by applying our theoretical fire triangle model to very real items in the news.

4 The Fire Triangle Model of Media Storms

The research process described in the previous section allows us to see the observed correlates of media storms versus non-media storms. In every case of a confirmed media storm we examined, there were three conditions – heat, fuel, and oxygen – that were present at strong levels (specifically, a categorization of “High” or “Very High” according to our guidelines; see online appendix). And in every case of a parallel event that did not become a media storm, at least one of these conditions was weak or lacking (a categorization of “Medium Low” or lower). Based on these correlates, we offer a theoretical model of the necessary conditions for an event (by which we mean a single event, a string of events, a discovery of new information about old events, etc.) to result in a media storm.

We use fire as an analogy. In the case of real fires, the “fire triangle,” championed in the US by Smokey Bear, is a simple model designed to help the average person understand the conditions needed to create most fires (Bear Reference Bear2019). Borrowing this fire triangle imagery, we offer a model of the three necessary conditions for media storms to occur.

The “heat” in our model is the spark that sets off the media storm, namely an event or the discovery of information that is dramatic and often tragic. Every event is a spark, of course, but media storms spring from sparks that are especially hot. The factors that go into what makes something “hot” is, put plainly, the perceived newsworthiness of the event: the population affected, the unexpectedness (or “shock value”) of the occurrence, and so on, as well as the availability of evidence (like video, photo, or audio).

The “fuel” is the current and historical state of the political and cultural landscape against which the event occurs that might increase the salience and/or cognitive accessibility of that event. For wildfires, we can think of fuel as the amount and type (e.g., dry/wet) of flammable wood and brush in a forest. In the case of media storms, the fuel is the recent or current state of any public discussions that would increase the resonance of a given event. More specifically, the fuel in our model can take one or both of two forms: first, an existing societal awareness of the underlying issue left over from previous media coverage and, second, active debates in other policy areas or in the cultural zeitgeist that allow news outlets to frame the event in question in a way that will resonate against the current landscape.

The “oxygen” is the available attention space in the news media in the first place (i.e., whether the current media agenda is already at capacity with other big stories), as well as attention the event receives beyond traditional news outlets, such as by activist groups, politicians, and/or people on social media.

Figure 1 offers a representation of the model, our homage to Smokey Bear. This figure summarizes the parts of each element and provides a visual reminder of the interconnected nature of the elements. Akin to Kingdon’s (2010) policy streams model, all three elements are required for a window of opportunity – in this case, a media storm – to occur. Also as with Kingdon’s model, the three elements of the fire triangle model are complex and interdependent. As one element rises, the other elements tend to rise as well. The more sensational an event (heat), for example, the more likely it is to draw attention on social media (oxygen). And the more an event taps into issues already on the political and public radar (fuel), the greater its newsworthiness (heat) will generally be. Thus, although in theory we could imagine a trade-off relationship between these elements, such that a media storm could erupt with only “Medium” levels of one element as long as the other elements were “Very High,” in practice the three elements tend to all be fairly high or all be fairly low. And just as with real fires, the levels of the elements determine not only whether a media storm erupts but also how big it is and how long it lasts.

Are these three conditions of heat, fuel, and oxygen jointly sufficient to produce a media storm? That is, if an event has strong levels of all three, will a media storm definitely result? It’s hard to say. In our research, we have not found any instances of an event that has strong levels of all three elements (again, at least “High” according to our categorization) but did not catch fire in the news. We present our fire triangle model of heat, fuel, and oxygen as the minimum conditions to prompt a media storm. If pressed, however, we would argue that strong levels of all three elements are jointly sufficient to prompt a media storm, at least in the case of US national news coverage.

Still, we can imagine scenarios where, by pure luck, even high levels of all three elements do not result in a full-blown media storm. Indeed, many of the media storms we have examined came very close to not catching fire in the national news. For example, on February 26, 2012 in Sanford, FL, Trayvon Martin – a Black seventeen-year-old boy – was walking home from the local 7-Eleven, with an iced tea and Skittles candy in his pocket, when George Zimmerman (a neighbor member of the local community watch) shot and killed him. Ultimately, the story became a media storm, but not immediately. As New York Times reporter Brian Stelter writes:

“It was not until mid-March, after word spread on Facebook and Twitter, that the shooting of Trayvon by George Zimmerman, 28, was widely reported by the national news media, highlighting the complex ways that news does and does not travel in the Internet age.

“That Trayvon’s name is known at all is a testament to his family, which hired a tenacious lawyer to pursue legal action and to persuade sympathetic members of the news media to cover the case. Just as important, family members were willing to answer the same painful questions over and over at news conferences and in TV interviews.” (Stelter Reference Stelter2012)

As another example, if President Obama had not declared the Flint, MI water crisis a national emergency in January 2016 (an action that definitely did not go without saying, since the crisis had been ongoing for nearly two years at that point), it is likely the media storm would not have erupted even though elements of heat, fuel, and oxygen were all already present to some degree. See Figure 6 for a chronicling of the Flint water crisis media storm.

Figure 6 Timeline of media storm surrounding Flint, MI water crisis.

The main takeaway point from our model is that media storms are not easily predictable; the occurrence of a profoundly important event is not alone sufficient. And as with real fires, media storms can prove harmful to the people or groups in the path of the flames (e.g., to police departments during the Black Lives Matter protests) but can also, at least sometimes, prove beneficial in the long run by clearing pent-up old brush from years of neglect, making way for new growth.

Of course, our model is not perfect. We present it with at least four cautionary notes. First, the three elements of the model are interdependent (just as heat, fuel, and oxygen are interdependent in the fire triangle model), such that in some instances it might be challenging to know exactly which of the three elements to use in labeling a given aspect of a news item. Second, to avoid confusion, we should not interpret the mechanisms of media storms too literally in comparison to real fires, where combustion occurs through specific physical processes and “fire occurs whenever combustible fuel in the presence of oxygen at an extremely high temperature becomes gas” (Bear Reference Bear2019). Instead, we apply the fire triangle as a useful analogy to describe the dynamic and interacting features of media storms that are often hard to discern or describe. Third, while media storms are, by definition, moments where news coverage has reached a tipping point, they are not an all-or-nothing phenomenon; some storms are bigger and last longer than others. The strength of the three elements of heat, fuel, and oxygen help determine not only whether an event prompts a media storm but also the size, scope, and duration of that storm. And even when news coverage does not reach the full tipping point of a media storm, there is important variance in how much coverage non-storm items get. Some events start to build momentum in the news and come close to catching fire but then peter out before meeting the full criteria for a media storm; we refer to these near misses as “storm fronts,” discussed more in Section 7. Fourth, readers will doubtless be able to think of cases where a media storm ignited without all three criteria or needed some extra ingredient that does not fit neatly in any of the three conditions of our model to push it to media storm levels.

As the statistician George Box is attributed as saying, “all models are wrong, but some are useful” (Reference Box, Launer and Wilkinson1979). We hope our fire triangle model offers a useful mental structure for thinking about media storms.

5 The Role of Political Actors in the Fire Triangle Model

We will turn to a more detailed discussion of the heat, fuel, and oxygen elements in Section 6. But first, in this section, we animate the media storm fire triangle model by talking about the many political actors – from journalists to politicians to everyday people – whose actions help drive (or hinder) the media storm process.Footnote 13 Specifically, we’ll talk about journalistic gatekeeping and muckraking; attention fatigue; activism and political maneuvering; and the importance of slogans and hashtags. The individuals behind these actions are motivated by different sets of incentives, sometimes clashing and diverging from one another. For example, a politician or official may seek to tamp down coverage of a Black person killed by police, while an activist works to increase the coverage around the same event (Lawrence Reference Lawrence2022).

We position this discussion before detailing the heat, fuel, and oxygen elements because political actors are at the core of our model and must be accounted for in evaluating the level of each element within a given case. Media storms do not simply happen; they are the result of different people in different roles with different motivations, all making decisions about whether or not (and if so, how) to engage with a potential news item. As Lawrence states, “These occasional openings in the news, moreover, illuminate the underlying factors that drive the construction of public problems in the news” (Reference Lawrence2022: 154).

Journalistic Gatekeeping and Muckraking

Arguably, the most important political actors in the media storm process are journalists, editors, and newsrooms more broadly. They serve as gatekeepers, deciding which items make it into the news and which don’t – as well as how much agenda space and what type of narratives to give those items they choose to cover (Lawrence Reference Lawrence2022). But news values are not formulaic calculations (see Section 6, Heat for more). Journalists individually make subjective decisions about what to value and, thus, what not to value. In addition to gatekeeping, journalists can also seek to influence politics through their news coverage – a practice called “muckraking” (Chalmers Reference Chalmers1959; Maloy Reference Maloy2020). In both cases, journalists use their own perspective, either subconsciously or consciously, to decide which stories to cover and how to cover them.

Thus, in our fire triangle model, we can think of the heat of an event as being its generic newsworthiness. Yet we also need to understand that journalists and editors serve as a kind of fuse governing how much to amplify or suppress the inherent heat (Zai n.d.). In making these decisions, journalists and editors put more value on some people and stories than others in ways that align with journalists’ interests (Kepplinger, Brosius, and Staab Reference Kepplinger, Brosius and Staab1991) or simply with their world views. These journalistic decisions often heighten the structural biases that are embedded in news values, such as giving greater priority to White women in cases of missing people and to the perspectives of more wealthy people in general (Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs, Matthews, Hicks and Merkley2021; Jacobs and Van Spanje Reference Jacobs and Van Spanje2023; Slakoff and Fradella Reference Slakoff and Fradella2019; van Dalen Reference van Dalen2012). These judgments serve to validate some voices over others.

In the case of police use of deadly force, for example, news outlets have historically validated police perspectives over Black community activists, prioritizing law enforcement as information sources and quoting them more frequently (Lawrence Reference Lawrence2022). George Floyd’s murder uncovered a wide gap in perceptions of newsworthiness between White and non-White journalists. As Washington Post media correspondents reported in June 2020, “Like the nation itself, news organizations across the country are facing a racial reckoning, spurred by protests from their own journalists over portrayals of minority communities and the historically unequal treatment of nonwhite colleagues” (Farhi et al. Reference Farhi and Ellison2020).

Beyond journalists’ perceptions of the inherent heat of a story, they also serve to interpret and filter the oxygen and fuel elements of our fire triangle model. For example, in our model social media attention is categorized under the element of oxygen. Yet this oxygen operates in part through journalists’ decisions to cover what’s happening on social media in the first place, thereby allowing social media discussions to fan the flames of preexisting news coverage, leading to more coverage in a self-reinforcing cycle (Staab Reference Staab1990). Journalists also lean on social media to inform them about stories as well as evolving public values and priorities (Walters Reference Walters2022; Weaver and Willnat Reference Weaver and Willnat2016). In this way, social media shapes journalists’ approach to the elements of heat and fuel.

For example, Figure 4 describes the media storm following H.R. 4437, the Border Protection, Antiterrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005. News outlets across the country could have decided to give a large volume of coverage to this bill when it passed the House in December of 2005. Yet the media storm did not hit until nationwide protests erupted in the spring of 2006 – captured in part through widespread discussion on social media. We argue that the oxygen from these protests was a necessary element in generating the media storm, but only because of how journalists and newsrooms operate. We can imagine a different reality, one in which a piece of legislation like H.R. 4437 would be deemed an important enough event to prompt a media storm on its own.

As a counterexample, consider again the Boston Globe journalists who made the intentional choice to focus countless hours of investigative reporting to uncover cases of child sexual abuse by Catholic priests. These journalists did their work in the face of aggressive pushback. The same can be said for the New York Times journalists who pursued the sexual assault and rape allegations against Harvey Weinstein. They could have chosen at many points to let the story drop, but their dogged reporting helped prompt a media storm with wide-reaching consequences.

Attention Fatigue

In general, there is a self-reinforcing relationship between the size and momentum of a media storm and how much fuel and oxygen are fed back into the storm. Regarding fuel, the eruption of a media storm puts the underlying policy issue front and center in people’s minds, making it more likely that related events also get news coverage, further fueling the ongoing media storm. Regarding oxygen, as a story rises in the news, it is more likely to make its way into the conversations outside of the news media (by politicians, late-night talk shows, and people on social media, as well as issue activists). In turn, as the attention outside the news media increases, it increases the media storm itself because news outlets report on people’s reactions to the news: front-page articles covering partisan responses to the story, culture pieces dissecting the significance of a Saturday Night Live parody of the story, and so on.

Yet we expect there is a limit to the self-reinforcing nature of fuel and oxygen in propelling media storms. Why? Because humans have a difficult time sustaining attention to a single issue over an extended period. After enough coverage of the same type of event, even talked about in different ways, attention fatigue (also called issue fatigue) can set in, signaling an information overload of news about a particular subject, or overexposure of news more generally (Gurr and Metag Reference Gurr and Metag2022; Neuman Reference Neuman1990). As Gurr and Metag summarize, “Issue fatigue denotes an individual’s negative state that emerges from overexposure to an issue that is covered intensively by the news media during weeks or months” (Reference Gurr and Metag2022: 18). Attention fatigue is especially likely to occur when the subject matter is distressing, and the underlying problems are hard to solve (as in the case of George Floyd or mass school shootings) or are hard for many to connect to their everyday lives (as in the case of climate change disasters or immigrant deportations).

Attention fatigue may affect different types of news consumers differently. For example, Tewksbury, Hals, and Bibart identify two main kinds of consumers: selectors, who “confine the majority of their news exposure to specific topics,” and browsers, who use “news media to obtain information on a range of topics” (Reference David, Hals and Bibart2008: 257). We can imagine that in the case of selectors for whom a media storm falls within their topics of interest (e.g., a media storm involving a celebrity for a person who seeks out celebrity news), attention fatigue will take longer to set in, if it ever does. By contrast, browsers may be more susceptible to attention fatigue, especially in cases where a media storm drags on, such as with the COVID-19 global pandemic (Ford, Douglas, and Barrett Reference Ford, Douglas and Barrett2023), when information overload could lead them to satisfice in their search for additional information and knowledge (Prabha et al. Reference Chandra, Connaway, Olszewski and Jenkins2007). Research is needed on how news consumption styles interact with – and further drive – the dynamics of media storms.

The result of attention fatigue can be issue avoidance, where people actively avoid the news about a particular issue (e.g., the war in Ukraine, ongoing since 2014 and especially since Russia’s invasion in 2021, or the Syrian refugee crisis, ongoing since 2011) (Skovsgaard and Andersen Reference Skovsgaard and Andersen2020). And during prolonged and sustained coverage or an overexposure where avoidance is less of an option (e.g., news coverage of the global pandemic starting in 2020), people may respond to information overload by adopting a “the news will find me” approach, especially if they have low trust in the traditional media (Goyanes, Ardèvol-Abreu, and Gil De Zúñiga Reference Goyanes, Ardèvol-Abreu and De Zúñiga2023). This behavior can heighten people’s exposure to misinformation and disinformation (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Merolla and Shah2021). News outlets, savvy to the ebbs and swells of audience attention, will respond to – or proactively anticipate – people’s attention fatigue in a given issue area by giving less coverage to that issue and related events.

The shift that can occur over time from self-reinforcing media coverage to attention fatigue is nicely captured in Downs’ (Reference Downs1972) issue-attention cycle mentioned in Section 2, where the realization of the complexities of a problem give way directly to declining interest in the problem. In our fire triangle model, the duration of a media storm hinges upon the interplay of oxygen, fuel, and heat, but not necessarily in a linear manner. At least in the case of fuel, we theorize a parabolic correlation between the continued fuel of an event and the amount and duration of news coverage the event receives: initially in an upward direction but then in a downward direction if/when attention fatigue sets in.

Activism and Political Maneuvering

Scholars measure media storms by the level of news coverage a story receives, but in many ways news coverage is an endpoint in the activism and political process. Beneath any news coverage paid to an issue – and beneath periods of time when the issue receives no news coverage – are activist groups, lobbyists, and other political actors constantly at work to promote their issues of concern, framed from their perspective, and sometimes to keep items out of the news. Activism and political maneuvering around a policy issue can lay the groundwork to capitalize on the spark from an event to ignite a media storm. Activism, in this context, functions as both the fuel to be ignited and the oxygen of amplification that can help produce and sustain a media storm, and the two elements can be so entwined as to make it difficult to differentiate what constitutes fuel versus oxygen.

Activism can provide fuel for a media storm through the cumulative activity within an issue area. Prior media storms and even non-storm coverage (including storm fronts) contribute to this fuel, shaping the landscape against which new events unfold. But if the issue landscape has a robust activist environment, it can make it easier for a related event to catch fire in the news. This activist environment can span small ad hoc grassroots efforts to the strategic efforts of long-established interest groups. In 2014, for example, the protests and Black Lives Matter movement organization that followed Michael Brown’s killing were populated not only by people in the local community of Ferguson, MO. Many activists and protestors traveled from around the country to help fuel the movement (Altman Reference Altman2014). The 2014 organization and codification of the Black Lives Matter movement meant that when George Floyd was murdered in 2020, the movement’s infrastructure was already strongly established. This preexisting network allowed mobilization to occur within hours of the video of Floyd’s murder being released, with marches and rallies organized across the country (Dunivin et al. Reference Dunivin, Yan, Ince and Rojas2022). Mobilization could not have happened so quickly without those networks and structures already in place. The fuel activism can provide for a media storm that extends beyond activists themselves and into the networks that activists establish with journalists, politicians, and other political actors (Lawrence Reference Lawrence2022; Litterer, Jurgens, and Card Reference Litterer, Jurgens, Card, Bouamor, Pino and Bali2023; Montpetit and Harvey Reference Montpetit and Harvey2018). Additionally, by strategically framing an issue, activists can broaden the scope of information and lend a sense of legitimacy to the activist groups and the causes they champion. In doing so, activists provide additional fuel for potential future media storms (Houston, Pfefferbaum, and Rosenholtz Reference Houston, Pfefferbaum and Rosenholtz2012).

At the same time, activism can provide the oxygen for a media storm by amplifying news coverage of a related event throughout these established networks, for example by posting and engaging with followers on social media, emailing established listservs of supporters and enlisting their engagement, and lobbying politician contacts to make statements in support of the activists’ aims (Brown, Block Jr, and Stout Reference Brown, Ray and Christopher2020; Reny and Newman Reference Reny and Newman2021). For example, by the time of George Floyd’s murder, the Black Lives Matter activists had already constructed networks beyond the activists themselves via an engaged audience on social media and established connections with journalists – the latter facilitated in part through an increase in resources in newsrooms available to devote to coverage of police use of deadly force (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Barthel, Perrin and Vogels2022; Cowart, Blackstone, and Riley Reference Cowart, Blackstone and Riley2022).

These network links between activists and journalists can create a positive feedback loop of information and reaction, especially during media storms, when journalists are especially likely to reach out to activist groups for their perspectives on unfolding events (Montpetit and Harvey Reference Montpetit and Harvey2018; Ploughman Reference Ploughman1995). The media storm also lowers the media’s gatekeeping threshold in the drive for more coverage, allowing the entrance of new viewpoints (Litterer, Jurgens, and Card Reference Litterer, Jurgens, Card, Bouamor, Pino and Bali2023). The collaborative efforts between activists and journalists create a fertile ground for the growth of organizations associated with the cause. This growth, in turn, facilitates increased funding and elevates the profiles of the activists involved (McAdam Reference McAdam2017; Montpetit and Harvey Reference Montpetit and Harvey2018). This added credibility helps meet what Lawrence (Reference Lawrence2022) describes as the “threshold of power,” which reflects the influence of institutional and social power structures on media coverage. Raising the profile of activist networks lends new legitimacy and credence to their cause, and this power dynamic can enable (or in some cases force) journalists to cover events and perspectives they might have otherwise ignored.

We must also consider the actions that activists and other political actors, including crisis management teams, often take toward influencing whether an event becomes a media storm. To extend our fire analogy, activist groups may try to increase the chances of a policy issue they care about catching fire in the news by strategically adding their own heat, fuel, and/or oxygen to the situation, as was the case in the Civil Rights Movement where activists staged high-profile sit-ins and members like Rosa Parks defied local laws in order to be arrested (Mazumder Reference Mazumder2018). Similarly, the Gay Rights Movement effectively used symbolic actions, such as same-sex couples applying for marriage licenses in states where it was illegal, to provoke legal battles and ensuing media coverage. In the lead-up to the 2015 Supreme Court decision on marriage equality (Obergefell v. Hodges), activists strategically framed these acts of civil disobedience to highlight the injustice of marriage bans, forcing the issue into the public and legal discourse. In our fire triangle model, efforts like these (whether by activists or other political actors) serve to heighten an already smoldering fire. We invite the reader to consider whether some tactics by issue activists or other political actors might be appropriately labeled “arson” in the fire triangle analogy.

However, not all groups actively seek media attention during the unfolding of events related to their cause. For instance, organizations like the National Rifle Association (NRA) may strategically avoid media coverage to prevent the escalation of a media storm that could be detrimental to their goals. These groups may even implement obstacles to dampen potential media attention and control the narrative surrounding specific events, such as school shootings (Gammon Reference Gammon2018). In the world of crisis management, often the strongest strategy in the wake of a scandal involving a political figure or a company is to issue a denial, even in the face of strong evidence of wrongdoing (Huang Reference Huang2006). Another strategy employed by politicians as well as interest groups is to “wag the dog” by offering to the media another juicy item far afield from the news item of concern. Applying the fire triangle analogy, we can think of these actions as fire prevention or containment measures, akin to clear cutting or trench digging in a given issue area or muffling flames with a blanket or water once a fire breaks out.

Whatever the form of the activity surrounding a specific event, activism and other political maneuvering can have long-reaching effects by changing the very landscape of an issue area. For example, just as the removal of vegetation in a forest sets the stage for rapid regeneration of highly flammable conditions, political interventions can create even more combustible environments.

Slogans and Hashtags

For activists and all other political actors, strategic messaging is important for both amplifying problems of concern (oxygen) and laying the groundwork to make these problems and perspectives readily accessible going forward (fuel). Slogans have always been a powerful tool in the strategic messaging toolbox (Van De Velde Reference Van De Velde2022). For example, the 1960s youth protest movement includes pithy slogans like “My Generation,” and more action-oriented ones like Timothy Leary’s “Turn on, tune in, drop out,” which were successful in pulling together people toward common goals (Kent Reference Kent2001). In the changing media landscape, messaging strategies have evolved from letters to the editor or phone calls to a local TV news station to become more nationalized and more visual. Social media platforms in particular have become the new arena for activists and issue publics (i.e., people who care strongly about single issues like abortion or gun control) to fight for relevancy about a cause and to compete for attention from the media and the public (Johann Reference Johann2022; Mortensen and Neumayer Reference Mortensen and Neumayer2021).

In this arena, slogans in the form of hashtags have become the coin of the realm, allowing communities to build around them online (Peters and Allan Reference Peters and Allan2022). Hashtags serve as both fuel and oxygen, providing a throughline for discussions of related events, past and present, and making it easier to amplify those events when they happen.

Hashtags are powerful not only for fostering and sustaining media storms but also for “exploiting” a crisis event that has prompted a media storm. For example, Hunt (Reference Hunt2022) examines the competing ways in which proabortion and antiabortion activists used social media, including hashtags, to capitalize on the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., #SheMakesHerSafeChoice versus #AbortionIsNotEssential). Through social media, the two sides exhibited “movement-countermovement” dynamics in their competition to frame abortion against the context of the ongoing pandemic (Hunt Reference Hunt2022).

Memes can serve a similar function to hashtags, providing culturally relevant visual information that creates a sense of community using irony or playfulness to impart a message (McVicker Reference McVicker2021). If the meme connects with enough people online, that group then becomes a new audience giving attention to an item, breathing oxygen into a potential or ongoing media storm. Hashtags and memes are easily accessible for average people to use and create on social media, broadening the scope of potential fuel and oxygen for media storms in the modern era.

Consider, for example, the success of the #MeToo hashtag posted by celebrity Alyssa Milano on Twitter on October 15, 2017. This hashtag went viral in the wake of two in-depth investigative pieces about Harvey Weinstein written by the New York Times on October 5 and The New Yorker on October 10. Those stories made huge waves, erupting into a media storm, with the #MeToo hashtag going viral on social media. This social media oxygen in turn helped amplify the story and helped create the environment that took down several powerful men perpetuating the offenses. However, the hashtag of #MeToo was born nearly eleven years earlier on MySpace (an early social media platform) by survivor and activist Tarana Burke in 2006. Burke’s efforts, though impactful in grassroots advocacy aimed at marginalized communities, did not catch fire in the mainstream media. The hashtag lay relatively dormant until it was picked up by Milano, whose celebrity status added heat along with the oxygen of her social media post. This discrepancy in impact can be attributed in part to structural inequalities within media and public attention: Burke, as a Black woman and noncelebrity, did not have access to the same platform or perceived status needed to amplify the message to mainstream audiences. Conversely, Milano was able to leverage her celebrity to push the hashtag into the public consciousness. The hashtag, in turn, gave the media storm more oxygen (and sustained fuel). This case illustrates how racial and social hierarchies often shape which voices and narratives gain traction in broader movements, despite the foundational work of activists like Burke (Garcia Reference Garcia2017).

6 Necessary Elements of Media Storms: Heat, Fuel, and Oxygen