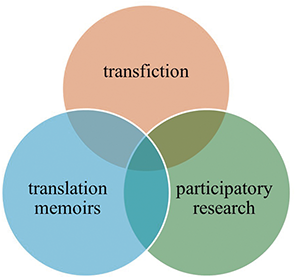

1 Introduction

In her novel The Extinction of Irena Rey (2024), translator and author Jennifer Croft stages a group of eight translators, each named after the language they translate into, gathering reverentially around and working in close collaboration with their author, titular Irena Rey. The plot takes an unexpected turn when Irena disappears, and is found to be writing The Translators, a novel within the novel about the translator-protagonists of Croft’s story, based on confidential information collected without their consent.

Much like the first few lines of this Element, examples of stories where translators and interpreters are featured as characters, or forms of language mediation become a theme, are often used anecdotally as a curious coincidence to introduce disparate subjects in academic literature, within and outside Translation Studies. John Keats’s poem ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’ prompts discussions on the pressure exerted by past poetic models (Lowe Reference Lowe2015); scenes from Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time are used as an example of how certain translations come to be seen as classics superior to new retranslations of the same source (Bandia, Hadley, and McElduff Reference Bandia, Hadley, McElduff, Bandia, Hadley and McElduff2025, 1–2); and peculiar forms of animalist activism in Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead are mentioned to introduce complex concepts, such as eco-translation (Cronin Reference Cronin, Beattie, Bertacco and Soldat-Jaffe2023, 8–9).

Although they may not be immediately identifiable, since they are not marketed as a distinct literary genre, narratives pivoting on translator figures or thematising language mediation abound. The ways in which they have been referred to in academic literature have varied in time, ranging from descriptive phrases, such as ‘translator fictions’ (Thiem Reference Thiem1995, 213), ‘fictional representations’ (Delabastita and Grutman Reference Delabastita and Grutman2005), and ‘racconti di traduzione’ [stories of translation] (Lavieri Reference Lavieri2007/2016), to more condensed and creative solutions, such as ‘transmesis’ (Beebee Reference Beebee2012) and ‘Übersetzungsfiktionen’ [translation fictions] (Babel Reference Babel2015). They are denoted here as ‘transfiction’, a portmanteau word coined by Kaindl and Spitzl (Reference Kaindl, Spitzl and Gambier2014) which joins ‘translation’ and ‘fiction’ together, and has been the term most frequently used for this phenomenon in recent publications (e.g., Miletich Reference Miletich2024b; Spitzer and Oliveira Reference Spitzer and Oliveira2023). The fictional component in transfiction is broadly conceived as encompassing written narratives, forms of life writing, audiovisuals, electronic literature, and all sorts of creative texts (Kaindl Reference Kaindl, D’hulst and Gambier2018a, 51–52).

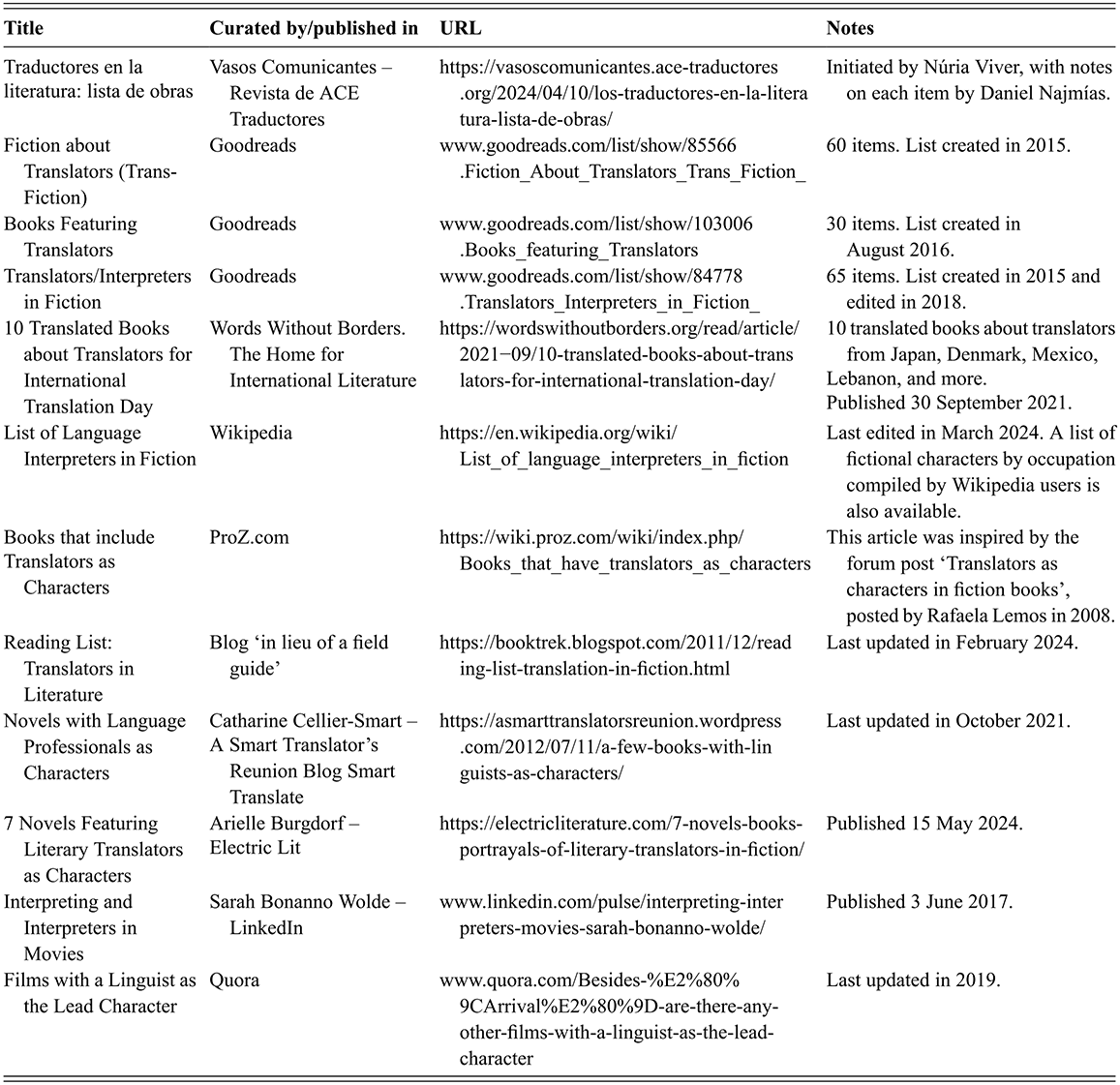

Whether a single translation scene is enough for a work of literature to be categorised as transfiction or the entire text has to revolve around a translator-character is open to debate. Ben-Ari (Reference Ben-Ari2010, 225) and Wakabayashi (Reference Wakabayashi2011, 88), for instance, point out that scenes of translation in their sources were often found in passing. In any case, scenes of translation span across the centuries as they do across different literary traditions and continents, ranging from classics such as Don Quixote and Jorge Luis Borges’s short stories (Reference Borges1939/1998) to the work of contemporary authors like Rebecca Kuang (Reference Kuang2022), Haruki Murakami (Reference Murakami2015), and Elena Ferrante (Reference Ferrante2013, Reference Ferrante2014). Translation scenes, however, are not a prerogative of written narratives. They are also found in films and sitcoms like Arrival (Villeneuve Reference Villeneuve2016)Footnote 1 and Father Ted (Lowney Reference Lowney1996),Footnote 2 plays, such as Brian Friel’s Translations (Reference Friel1980/2012), advertisements and online content (Abend-David Reference Abend-David2019).

Despite being a centuries-old phenomenon (Kaindl Reference Kaindl, Kaindl and Spitzl2014, 4–8), the fictional representations of language mediators started attracting scholarly attention only in the early 2000s (see, e.g., Delabastita Reference Delabastita, Baker and Saldanha2009; Delabastita and Grutman Reference Delabastita and Grutman2005; Strümper-Krobb Reference Strümper-Krobb2003). At this point, Pagano (Reference Pagano, Tymoczko and Gentzler2002, 81) reported the ‘fictional turn’ in Translation Studies, which had been inaugurated by Else Vieira (Reference Vieira1995) seven years before in ComTextos, a somewhat obscure journal, which by now appears to be unretrievable.

The academic scrutiny of translation scenes has typically revolved around one or a small group of examples, with case studies populating transfiction research. The case study design, along with its characteristics and the inherent limitations it comes with, prompts the research questions of this Element. Charting Transfiction asks:

1) What patterns can be identified in existing transfiction research?

2) How can transfiction research diversify the design and methodologies that have traditionally informed this area of enquiry? And what benefits could this diversification bring?

3) How can transfiction be made useful for neighbouring research subfields of Translation Studies?

Accordingly, the overarching aims of this Element are to provide both the phenomenon and the research area of transfiction with a higher degree of visibility and systematisation than it has achieved to date, as well as inspiring other researchers, not only to consider this phenomenon, but also to investigate it following novel methodological approaches. The ultimate objective of the Element is thus to provide future researchers with a reference point that synthesises the practices of knowledge building employed by existing transfiction studies, while also making a pathway for transferability and opening new research avenues.

There are both contextual and methodological reasons that make these questions worth asking. Literature that makes use of translation as a motif and translators as characters continues to be published (e.g., Calleja Reference Calleja2023; Croft Reference Croft2024; Kuang Reference Kuang2022; Milkova Reference Milkova2022; Rossari Reference Rossari2023; Xhoga Reference Xhoga2025). This kind of literature has been the object of sustained academic engagement (e.g., Kripper Reference Kripper, Blakesley and Large2023; Miletich Reference Miletich2024b; Spitzer and Oliveira Reference Spitzer and Oliveira2023), ‘foreground[ing] aspects of literary texts that might otherwise pass unnoticed’ (Spitzer Reference Spitzer, Spitzer and Oliveira2023, 3). In addition, translators who also write non-translated narratives often fictionalise themselves in different forms of prose (e.g., Bianciardi Reference Bianciardi1962/2019; Lahiri Reference Lahiri2015; NíGhríofa Reference NíGhríofa2020), and this phenomenon prompts further questions on literary translation processes, translators’ (self-)perceptions, and Translator Studies. These reasons are accompanied by translation and translators becoming increasingly visible in contexts where they have historically been marginalised, ranging from prestigious literary award ceremonies to dedicated book clubs, social networks and other digital spaces. These factors may have an impact on more or less lay imaginaries of translators and translation, which in turn may inform transfiction. On the methodological level, these questions can be answered by adopting a research design that is more comprehensive than and, hence, transcends the small-scale scope of the case study design.

1.1 Methodology

Recent publications (Kripper Reference Kripper, Blakesley and Large2023; Miletich Reference Miletich2024b; Spitzer and Oliveira Reference Spitzer and Oliveira2023) show that, in contrast to what Ben-Ari (Reference Ben-Ari, Kaindl and Spitzl2014, 122) concluded, the fictional turn has not ‘exhausted itself’. However, this turn has developed in close dependence on relatively isolated cases. This tendency has arguably kept fictional enquiry in translation from having a considerable impact on Translation Studies as a whole in terms of how research is carried out, as opposed to the materials researchers can act on. In 2014, when the term ‘transfiction’ appeared, Ben-Ari asked rhetorically ‘[h]ow many more novels about frustrated translators/interpreters? Past parody, what remains is tedious repetition’ (ibid.). More than ten years later, the same repetition is still apparent, but in the form that most transfiction research has taken, rather than in creative work featuring translators. In her review of Cleary’s The Translator’s Visibility (Reference Cleary, Baer and Woods2021), Strümper-Krobb (Reference Strümper-Krobb2022, 345) notes how ‘Cleary’s observations about the way in which the theme of translation is mobilized’ in Latin American literature ‘echo what has been argued by scholars like Klaus Kaindl, Dirk Delabastita and Rosemary Arrojo with regard to texts from a wide range of literatures’. Strümper-Krobb’s comments on Cleary’s monograph are far from diminishing its contribution to knowledge and, in fact, point to the transferability of existing findings. At the same time, however, these comments may be taken as indicative of a certain repetition in how transfiction research has been designed (see also Bergantino Reference Bergantino2024, 237). One way of advancing research in this field in a more systematic and productive way, therefore, is to map how knowledge has been produced in transfiction studies, as opposed to focusing on specific instances of the phenomenon. Meta-research would provide a comprehensive picture of transfiction studies that concentrated engagement with individual texts could not.

While meta-research – or research on research – has gained traction across a variety of scientific domains (Hoon Reference Hoon2013, 526; Ioannidis Reference Ioannidis2024, 2; Timulak and Creaner Reference Timulak, Creaner and Flick2022, 555), Translation Studies does not appear to follow suit.Footnote 3 As observed by Du and Salaets (Reference Du and Salaets2025, 2), in their meta-study of collaborative learning in translation and interpreting, in Translation and Interpreting Studies, ‘there has been a lack of efforts to synthesise existing literature, including methodological approaches, empirical findings, and limitations, and to explore their implications for future research’. This state of affairs also applies to transfiction research, which has relied heavily, if not exclusively, on case studies and qualitative methods, without necessarily bringing existing studies into conversation. Therefore, to reach the aims outlined earlier, Charting Transfiction adopts a meta-analytical research style. In other words, it does not provide another in-depth analysis of one or multiple primary sources that happen to have a transfictional component. Instead, it collates existing studies to capture the state of the art of transfiction research as a whole. To reach this aim, it catalogues the practices of this area of enquiry, namely ‘the research methods and procedures used to conduct the research activities’ (Causadias et al. Reference Causadias, Korous, Cahill and Rea-Sandin2023, 88), as well as the materials underpinning these activities and the related dissemination strategies. This way, gaps in existing research are found, and new research avenues are identified that could be experimented with in future transfiction studies to bridge these gaps.

Case studies are a common research design in Translation Studies in general (Borg Reference Borg, Blakesley and Large2023, 35; Hadley Reference Hadley2023, 12; Susam-Sarajeva Reference Susam-Sarajeva2009, 37). Yet literature focusing on their use in translation research specifically is not particularly rich. Case studies have been shown to be an applicable approach to ‘illustrat[e] and problematis[e] findings’ (Hadley Reference Hadley2023, 10), as well as generating hypotheses (Saldanha and O’Brien Reference Saldanha and O’Brien2013, 209). However, as noted in other Translation Studies subfields like indirect translation, this research style ‘may not be the likely means by which the topic comes to be fully integrated within Translation Studies to the extent that its methods and findings inspire research in other topics’ (Hadley Reference Hadley2023, 10). Further complications are given by the different understandings of what counts as a case, and whether cases are to be taken as a specific method, a general methodology, or a flexible research style, as well as what each of these alternatives is supposed to look like. In addition, the extent to which the context-bound findings of individual case studies can be generalised is controversial (Flyvbjerg Reference Flyvbjerg2006, 226–228; Saldanha and O’Brien Reference Saldanha and O’Brien2013, 209; Susam-Sarajeva Reference Susam-Sarajeva2009, 44).

In this context, case studies are understood as ‘a particular design of research, where the focus is on an in-depth study of one or a limited number of cases’ in the context of which ‘particular methods may then be adopted’ (Tight Reference Tight2017, 6, 21). Saldanha and O’Brien (Reference Saldanha and O’Brien2013, 207) explain that in Translation Studies ‘a case can be anything from an individual person (translator, interpreter, author) or text …, to a whole organization, such as a training institution or a translation agency, and even a literary system’. In transfiction research, these options have been restricted to texts that contain a transfictional element.

1.1.1 Bibliographic Search, Inclusion, and Exclusion Criteria

The phenomenon that here is referred to as ‘transfiction’ has been labelled in a variety of ways – or has not been mentioned at all – over the last thirty years, as pointed out earlier. This variety of labels can be subsumed under the ‘terminological inflation’ observed by Gambier (Reference Gambier2023, 319) in Translation Studies more generally. It also has practical consequences for conducting a meta-study, bedevilling the search for appropriate primary sources. First, no single term (e.g., ‘transmesis’) or string (e.g., ‘fictional representations’) can be used in isolation to identify all transfiction-related publications. Second, opting for a specific term may lead to results that are not necessarily relevant to the study. ‘Transfiction’ and its permutations, for instance, are also used in connection to fiction authored by trans writers and to phenomena pertaining to Transmedia Studies (Miletich Reference Miletich and Miletich2024a, xv). ‘Transmesis’, instead, encapsulates several phenomena that go beyond and/or are not necessarily connected with the fictional representations of translators as characters, such as code-switching and pseudotranslation (Beebee Reference Beebee2012, 6). Thus, the starting point for the bibliographic search underpinning this meta-study is the literature review of the recent PhD thesis on transfiction, Translators in Fabula, Bridging Transfiction and Translator Studies through a Comparative Analysis of Contemporary Italian Narratives (Bergantino Reference Bergantino2024). Although anchored to the Italian context, this thesis takes stock of transfiction research and its development in general, identifying its main publication spaces and terminological developments, including special issues of specific journals, monographs, edited collections, and book chapters. While not all items in a certain publication venue mentioned in the thesis may be relevant to the thesis itself, each publication venue identified in the thesis and all its related items have been considered for this meta-analysis to ensure a high level of systematisation and exhaustiveness. For example, while not all articles belonging to a given special issue are reviewed in the thesis, that same special issue was searched for this meta-analysis. Although this approach does not rely on systematically searching online databases, it ensures that all publications captured are relevant to transfiction research, reducing the risk of false positives. It also excludes research outputs that use ‘transfiction’ to refer to different topics and phenomena or happen to cite publications that include this word in their bibliography or in the researcher’s biographical note, while bearing no or very little relevance to the publication itself.

The language of publication has been restricted to English in the attempt to strike a balance between personal limitations and linguistic equity. Why include publications in English, German, and Italian – the languages I happen to speak – but not those in Portuguese, Spanish, and Turkish, of which I have partial understanding or no command at all? The choice of English also ensures that most recent publications in transfiction, which have appeared in this language, are included.Footnote 4 It has to be acknowledged that transfiction publications in other languages, especially German, are highly represented – in fact, foundational – in transfiction research (e.g., Babel Reference Babel2015; Kaindl and Kurz Reference Kaindl and Kurz2010b; Kaindl and Kurz Reference Kaindl and Kurz2008, Reference Kaindl and Kurz2005; Strümper-Krobb Reference Strümper-Krobb2009; Wilhelm Reference Wilhelm2010). Despite possibly different rhetorical traditions in academic writing, however, research designs, methods, and primary sources used in non-English publications might not differ substantially from those used in English-language publications.

Another criterion for inclusion and exclusion is of a thematic nature. While transfiction is understood in this context as creative texts featuring language mediators, academic scrutiny of translation fictions has actively tried to stretch the borders of this definition to encompass other phenomena, such as pseudotranslation and self-translation (Ben-Ari and Levin Reference Ben-Ari and Levin2016; Woodsworth Reference Woodsworth and Roberto2018). For this study, these two phenomena are not automatically considered to be transfiction, unless existing studies have engaged with a narrative that stages a pseudotranslator or a self-translator as a character.

1.1.2 Corpus and Categories of Analysis

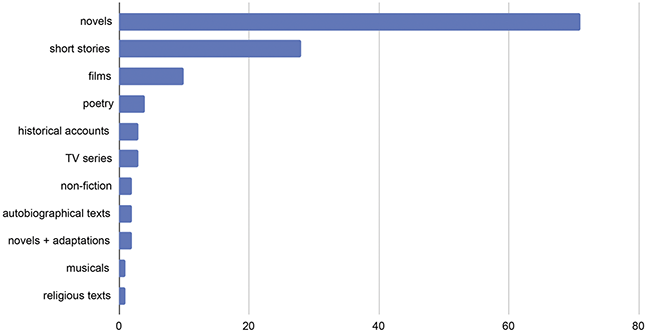

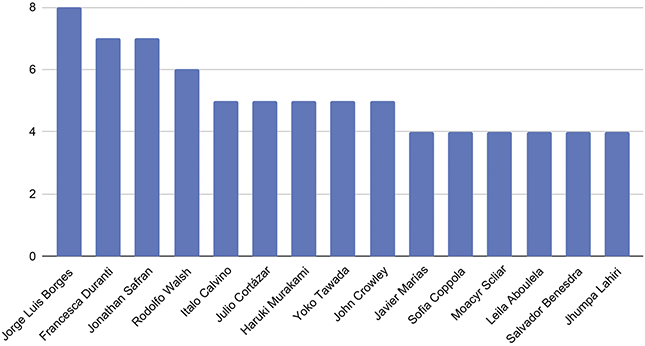

Keeping these criteria in mind, a total of 113 publications were found and listed in a spreadsheet, so as to create a structured, tabular dataset, and consequently conduct a descriptive analysis of it, as well as visualising its patterns by means of charts and tables (see McDonough Dolmaya Reference Dolmaya, Julie, Walker and Federici2024, 143–146). The bibliographic search gathered publications from 1995 to 2025, thus covering the last thirty years. To answer the first two research questions of this Element, each publication was read with a view to identifying features that were then grouped into predetermined categories. These categories are ‘author’, ‘year of publication’, ‘type of publication’, ‘research design’, ‘methodology’, ‘statement of purpose’, ‘materials’, ‘key words’, and ‘authors of primary sources’. While author details are easily found in the title page of each publication, information pertaining to the other categories of analysis was retrieved from the abstracts and the introduction section of each publication. This choice is due to these two spaces being expected to contain and describe essential components of a research output, such as methodologies and primary sources. After this first categorisation process, more categories were established a posteriori in relation to research design and methodologies, specifically, based on observable patterns emerging from the first phase.

1.2 The Fictional Turn: An Overview

While analyses of individual literary texts in transfiction research abound, the number of comprehensive overviews of this subfield is quite modest. Publications providing a reference point in the field might be expected to be found in encyclopaedias and handbooks, along with introduction chapters. The corpus of this study includes only two encyclopaedia entries, two handbook chapters, and seven publications with the function of introducing edited collections and special issues. Collectively, these are 11 publications out of 113, constituting 12.4% of the corpus. This section synthesises this subgroup of publications, together with other landmark publications, to provide an overview of the recurrent themes, functions, and types of narratives that fictional translators have been found to appear with, contextualising them within the fictional turn in Translation Studies.

The fictional turn has relied on two overarching principles, one of a theoretical nature and the other of a methodological one. The first principle is condensed by Pagano (Reference Pagano, Tymoczko and Gentzler2002, 80–81) in the argument that ‘fictional works contain a theoretical component’ and, hence, fiction can be incorporated in Translation Studies ‘as a medium of theoretical speculation’ and ‘translation theorization’. This idea of fiction being complementary to traditional academic research has been reiterated by several transfiction scholars, becoming a recurrent justification for research engaging with fictional representations despite conspicuous terminological diversity (e.g., Arrojo Reference Arrojo, Kaindl and Spitzl2014; Gentzler Reference Gentzler2008; Lavieri Reference Lavieri2007/2016; Spitzer Reference Spitzer, Spitzer and Oliveira2023; Spitzl Reference Spitzl, Kaindl and Spitzl2014). The fictional turn does not operate under the illusion of using fiction as a source of evidence or crystallised factual information on translation theory and practice. Giraldo and Piracón (Reference Giraldo, Piracón, Spitzer and Oliveira2023, 112) remain cognisant of this logical complication when they explain that

the connections we establish between fiction and theory are always contingent, constructed by readers, so we will not be appealing to a notion of an idealized, accessible intention in which authors may have purposefully been articulating their own works using the key of an outside theory, or even to the possibility that they may have been at all interested in offering insights on translation or translators.

Fiction does not necessarily overlap or aim to reproduce reality (John Reference John and Hagberg2016, 36; Kaindl Reference Kaindl, Spitzer and Oliveira2023, 25; Reference Kaindl and Woodsworth2018b, 164). Thus, rather than proposing ‘a complete postmodern fictionalization of the world’, transfiction is used as a basis to reflect on ‘points of intersection’ between fiction and reality, ‘points that can contribute to a fruitful exchange and the discovery of new ideas’ (Kaindl Reference Kaindl and Woodsworth2018b, 159). The fictional turn harnesses the potential of fictional representations to offer ‘a comment on the socio-cultural values and the state of the world we live in’ (Delabastita and Grutman Reference Delabastita and Grutman2005, 24), a point raised about fictional characters more generally (Carroll Reference Carroll and Hagberg2016, 84; John Reference John and Hagberg2016, 46; Schoeneborn and Cornelissen Reference Schoeneborn, Cornelissen, Neesham, Reihlen and Schoeneborn2022, 140, 152). Fictional representations of translators, in particular, are argued to provide a ‘mimetic treatment’ of ‘those ‘black-box’ aspects of the translational process that translations as finished products obscure’ (Beebee Reference Beebee2012, 3), such as affective elements (Anderson Reference Anderson2005, 181). Moreover, they have been used to deconstruct clichés traditionally associated with translation and translators, including the nebulous notions of ‘original’, ‘equivalence’, ‘fidelity’, ‘authorship’, along with their related dichotomies (Arrojo Reference Arrojo, Cronin and Inghilleri2018, 18; Kaindl Reference Kaindl and Woodsworth2018b, 161; Lavieri Reference Lavieri2007/2016, 63–82).

While theorisation based on fictional representations has been widely justified, the ways in which this can happen in practice have not been outlined in great detail. Hagedorn (Reference Hagedorn2006, 11) was probably one of the first scholars to provide a broad description of how research on the theme of translation can be done. Hagedorn identified an underlying methodological principle in the ‘inversión de la perspectiva traductológica’ [inversion of the translational perspective]. Accordingly, this kind of research is not concerned with finding out what happens when a text is translated into another language and the related strategies adopted by the translator, but with how writers represent translators and translation in their narratives, and what characteristics and implications these representations may have (see also Wilson Reference Wilson2007, 382).

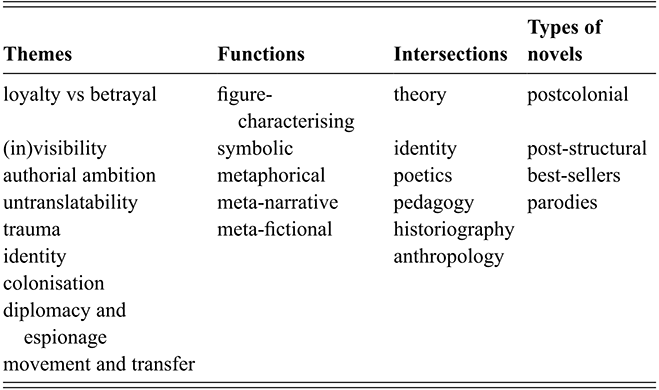

Scholarly engagement with ‘the triad fiction-theory-translation’, as Pagano (Reference Pagano, Tymoczko and Gentzler2002, 81) puts it, has resulted in the identification of thematic constellations, recurrent functions of translations as a narrative element, and points at which fiction and academic enquiry can meet. Delabastita and Grutman list possible themes accompanying the fictional representations of multilingualism and translators, namely trust, loyalty versus betrayal, invisibility and authorial ambition, untranslatability, trauma, and identity (Reference Delabastita and Grutman2005, 23; emphasis in the original). Because it is often used metaphorically, as opposed to an act of linguistic transfer, translation can also be used because of its ‘expressive, symbolic, and representative potential … to address themes of movement, such as migration, flight, displacement, wandering, restlessness, or uprooting’ – in sum, ‘a whole plethora of transfer processes’ (Kaindl Reference Kaindl, Kaindl and Spitzl2014, 2, 4; emphasis added). Many of these topics, by now, have become recurrent talking points both in transfictional texts and academic literature more broadly. Delabastita (Reference Delabastita, Baker and Saldanha2020, Reference Delabastita, Baker and Saldanha2009) goes on to describe some of the contexts in which fictional language mediators are likely to be encountered. These range from the transmission of divine messages in sacred texts to science fiction, from narratives of conflict, broadly conceived, to those of colonisation and espionage. Ben-Ari (Reference Ben-Ari, Kaindl and Spitzl2014, 114–116), instead, proposes a tentative typology of novels with translator-protagonists, identifying four categories: postcolonial novels, post-structural novels, best-sellers that capitalise on translation as a fashionable theme, and novels that parody the same theme and/or genre.

Moving on from the themes to the roles performed by translation as a narrative element, Kaindl (Reference Kaindl, Gambier and van Doorslaer2012, 146–147) identifies five main functions:

1. The figure-characterizing function assigns certain characteristics to fictional language mediators, which often take the form of translatorial clichés, such as betrayers, uprooted subjects, and facilitators. Associated with this function is the hypothesis that transfiction may be taken as indicative of how specific cultures think of translators and interpreters, a hypothesis which builds on ‘Lévi-Strauss’ (1985, 9) thesis that societies frequently ascribe certain traits to certain professions’ (Kaindl Reference Kaindl, Kaindl and Spitzl2014, 17).

2. When the topic of translation works as an allusion to wider philosophical matters and societal and historical concerns it performs a symbolic function.

3. Similarly, the metaphorical function shifts translation from a text-based act to a metaphor, such as cultural translation.

4. The meta-narrative function occurs when the entire narrative hinges on the theme of language mediation itself. Kaindl (Reference Kaindl, Gambier and van Doorslaer2012, 147) notes elsewhere that this function is privileged by authors who are also translators and use fiction as a site to reflect on their profession.

5. The meta-fictional function occurs when translation is used as a narrative device conducive to the unfolding of the plot, typically in the form of mysterious manuscripts and their (pseudo)translation. This function overlaps with those described by Hagedorn (Reference Hagedorn2006) in his anatomy of fictitious translations, as well as those traditionally ascribed to pseudotranslation, such as the introduction of stylistic novelties, mechanisms to deflect authorship, as well as the responsibility it comes with, and parody (Bergantino Reference Bergantino2023; Kupsch-Losereit Reference Kupsch-Losereit, Kaindl and Spitzl2014; Maher Reference Maher, Washbourne and Van Wyke2019; Rath Reference Rath, Bandia, Hadley and McElduff2024; Strümper-Krobb Reference Strümper-Krobb and Woodsworth2018).

While the identification of these themes and functions offers reference points for transfiction research, it does not deal with the complications arising from the fact that the ways in which fiction and academic literature describe the world are, by definition, distinct. In the context of the fictional turn, this discrepancy is perceived as an advantage for research. Pagano (Reference Pagano, Tymoczko and Gentzler2002, 97), for instance, explains that ‘fiction represents a genre that informs translation thinking from a comprehensive perspective, sensitive to relationships and movements difficult to capture through more orthodox analyses that do not consider fictional texts’. What these relationships and movements might look like and what implications they may have for translation theory-building and hypotheses, however, is often left to interpretation and philosophical observations. An attempt at pinpointing these relationships between (trans)fiction and academic enquiry is presented in a chapter of A History of Modern Translation Knowledge, where Kaindl (Reference Kaindl, D’hulst and Gambier2018a, 53–54) lists four points of intersections:

1. The first point is theory. Fictional representations are seen as a potential starting point to develop theoretical understandings of translation, thematising concerns that are resonant with academic issues, such as the relationship between translations and their sources, authorship and translatorship, in a way that is often reminiscent of translation theories originating in deconstructive and postmodern approaches.

2. Identity follows, being thematised in transfiction in a variety of ways, ranging from the individual to the national level, while also considering migration and translingual and transcultural identities.

3. Poetics is the third intersection. Reference is made here to Lavieri’s Translatio in Fabula (Reference Lavieri2007/2016), where it is argued that ‘[l]a valorizzazione del traduttore e del suo lavoro diventano possibili soltanto attraverso il riconoscimento di una poetica che gli sia propria’ [the valorisation of translators and their work becomes possible only through the acknowledgement of their own poetics] (Lavieri Reference Lavieri2007/2016, 51).

4. Pedagogy refers to ‘the potential of fictional texts for translator and interpreter training’ (Kaindl Reference Kaindl, D’hulst and Gambier2018a, 54). Cronin (Reference Cronin2009, xi) had already encouraged the pedagogical use of transfictional materials, pointing to films featuring language mediation as valid teaching and learning resources. Recent pedagogical applications of transfiction are found in Cleary (Reference Cleary, Baer and Woods2021) and Kripper (Reference Kripper, Blakesley and Large2023).

In ‘The Remaking of the Translator’s Reality. The Role of Fiction in Translation Studies’, Kaindl (Reference Kaindl and Woodsworth2018b, 162–168) extends this list of intersections, adding historiography and anthropology to theory, identity, poetics, and pedagogy. These intersections are presented here in light of ‘the epistemological knowledge that can be gained from fictional representations of translators and interpreters’ (ibid., 158).

5. Historiography, like fiction, is seen as far from providing bare facts because ‘the depiction of historical events inevitably involves narrative emplotments’ (Kaindl Reference Kaindl, D’hulst and Gambier2018a, 163). This connection between fiction and historiography is also teased out by Spitzer (Reference Spitzer2017, 15), who explains that when ‘narrating events from a distant past, … a fictionality resounds from the very possibility of writing such a narrative with direct speech and an interiority assigned to characters’. A famous example is the story of Doña Marina, also known as la Malinche, the interpreter of Hernán Cortés who is often invoked in transfiction research (e.g., Cleary Reference Cleary, Baer and Woods2021; Gentzler Reference Gentzler2008; Valdeón Reference Valdeón2011).

6. Finally, Kaindl (Reference Kaindl and Woodsworth2018b, 164–168) argues that fictional representations intersect with anthropology because authors of transfiction draw from a society’s imagery of translation as a context-bound phenomenon. Fictional representations, therefore, are ‘rooted in a collective translatorial memory of a society’ (ibid., 165; emphasis in the original). Accordingly, analysing transfiction would imply dealing with the conceptualisations of translation proper to specific cultures and traditions in space and time.

The findings of existing transfiction research presented in this section, in terms of themes transfiction has been found to appear with, the types of novels featuring translator-characters, the functions of translation within fiction, and the intersections of (trans)fiction and other fields of academic enquiry are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1Long description

The table consists of 4 columns: Themes, Functions, Intersections, and Types of novels. It is arranged in rows, and the items in each column stand alone without any intended associations to items in other columns. Themes: loyalty versus betrayal; (in)visibility; authorial ambition; untranslatability; trauma; identity; colonisation; diplomacy and espionage; movement and transfer. Functions: figure-characterising; symbolic; metaphorical; meta-narrative; meta-fictional. Intersections: theory; identity; poetics; pedagogy; historiography; anthropology. Types of novels: postcolonial; post-structural; best-sellers; parodies.

Identifying these themes, functions, and intersections in conjunction with transfiction as a phenomenon and a research area is conducive to a better mapping of transfiction and transfiction research, which have both been largely unsystematised. Existing literature does not suggest that these functions and intersections are in a relation of mutual exclusion. The difference between symbolic function and metaphorical function, for instance, is very nuanced. Likewise, historical narratives about translator figures in a specific context may feed not only into historiography, but also anthropology and pedagogy. Kripper (Reference Kripper, Blakesley and Large2023, 43) exemplifies this possibility, anchoring her area-specific analysis of Latin American transfiction to a culture of ‘mistranslation and other digressive approaches [that] disrupt official historical discourses in contrapuntal narratives that reread and rewrite history’. In addition, Kripper (Reference Kripper, Blakesley and Large2023) uses her case studies of transfiction for pedagogical purposes, proposing questions for class discussion at the end of each chapter of her monograph. Therefore, while this categorisation represents a valid reference point when navigating transfiction and its publishing landscape, it may well be the case that the fabric of functions, intersections, and themes of transfiction is much more fine-spun than it appears here.

2 Transfiction Research: The Bigger Picture

2.1 Themes in Transfiction and Transfiction Research

When it comes to themes, in particular, the identification of clear-cut thematic areas can be far from straightforward within and outside transfiction research, for several reasons. First, subjective interpretations of a narrative can easily result in somewhat arbitrary thematic categories. Second, themes themselves are often hard to tell apart, so matters of identity could be closely bound up with the phenomenon of self-translation, and the act of writing could be perceived as encapsulating that of translating, as opposed to the two being completely different processes. Similarly, the idea of transfer can play out on a linguistic level, as well as on an existential or physical one. Third, methodological complications can influence this identification. Hadley (Reference Hadley2023, 13) notes that ‘[p]articularly for topics that could be seen as contentious, it may be especially problematic to rely on forms of analysis that do not have any obvious means of accounting and control for confirmation bias, such as close reading’. Even when conducting a meta-analytical study, nevertheless, it is complicated to tell apart the themes found in each publication from the themes of their respective primary sources, especially because this research design zooms out to a wide, comprehensive view of existing research, as opposed to offering a detailed review of each item in the dataset.

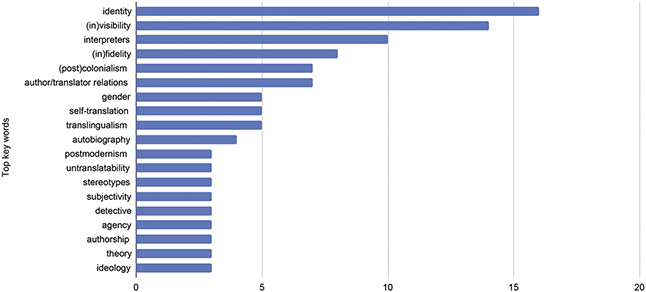

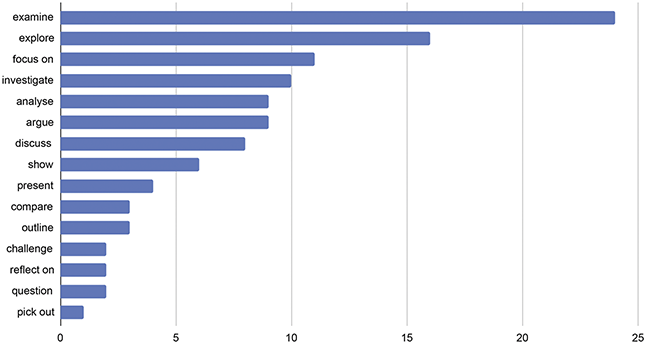

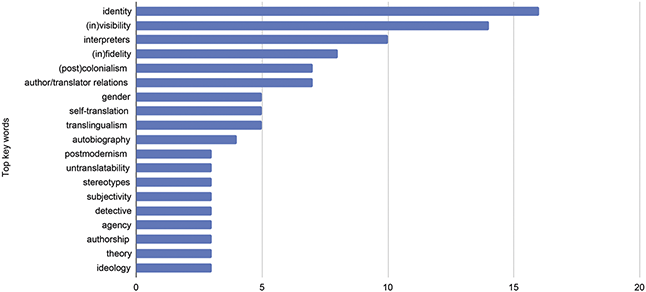

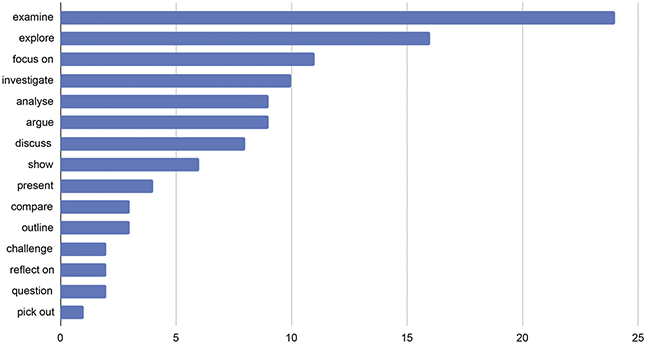

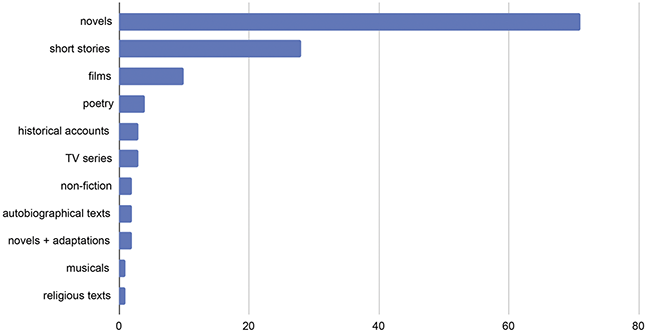

To provide a thematic overview trying to curb subjective interpretivism, while also accounting for more than a hundred publications, key words were extracted from each publication whenever available, being taken as indicative of the main themes with which the publications engage. When no key word was indicated explicitly, words appearing in section titles were used. These were filtered further to identify those key words and the related themes that appear with the highest frequency in the dataset. Further filtering was applied to those concepts that tend to appear in pairs, typically with one concept being the counterpart of or closely related to the other, such as ‘invisibility’ and ‘visibility’ or ‘infidelity’ and ‘fidelity’, as well as ‘colonialism’ and ‘postcolonialism’. The results of these procedures are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Top key words

‘Identity’ was found to be the most represented topic in the corpus (14.8%), followed by ‘(in)visibility’ (13%), research dealing explicitly with ‘interpreters’ (9.3%), rather than translators in general, ‘(in)fidelity’ (7.4%), and ‘(post)colonialism’ (6.5%) at the same place as ‘author/translator relations’ (also 6.5%). ‘Gender’, ‘self-translation’, and ‘translingualism’ follow, sharing the same frequency (4.6%). ‘Autobiography’ is represented in 3.7% of the corpus. Other topics ranging from ‘postmodernism’ to ‘ideology’ appear less frequently, with each accounting for 2.8% of the corpus.

Figure 1 confirms identity as one of the underlying topics in transfiction research. Identity stands out as a multifaceted and complex concept, as it can refer to single individuals or groups, as well as nations and even larger geographical areas and cultural traditions (Cronin Reference Cronin2000; Gentzler Reference Gentzler2008; Godbout Reference Godbout, Kaindl and Spitzl2014), spanning postcolonial and migratory configurations (Polezzi Reference Polezzi2012, 354) and globalisation (Cronin Reference Cronin2003, 73; Kaindl Reference Kaindl, Gambier and van Doorslaer2012, 145). The increase in the number of narratives featuring fictional translators, in fact, has often been traced back to globalisation and the challenges it has posed for individuals, translation, and society in general (Delabastita Reference Delabastita, Baker and Saldanha2009; Kaindl Reference Kaindl, Angelelli and Baer2016; Kaindl and Kurz Reference Kaindl, Kurz, Kaindl and Kurz2010a; Strümper-Krobb Reference Strümper-Krobb2003).

Other high-frequency themes shown in Figure 1 have been the subject of ongoing debate not only in transfiction research, but in Translation Studies more broadly. Invisibility epitomises this pattern, being ‘one of the most ubiquitous concepts in contemporary translation studies’ (Freeth Reference Freeth, Freeth and Treviño2024, 7). Much research in transfiction has engaged with this topic to argue that fictional representations may contribute to elevating translators from their notorious state of invisibility. This pattern in transfiction research, which has been labelled as ‘compensation theory’ (Bergantino Reference Bergantino2024, 118-119), emerges from studies on both transfiction in general and individual cases (Beebee Reference Beebee2012, 217; Cronin Reference Cronin2009, x–xi; Kaindl Reference Kaindl, Kaindl and Spitzl2014, 4; Kripper Reference Kripper, Blakesley and Large2023, 111; Strümper-Krobb Reference Strümper-Krobb2009, 14–21; Wilhelm Reference Wilhelm2010, 88–93; Wilson Reference Wilson2007, 381–382). To date, there has been little challenge to this theory of augmented translator visibility through fictional representation (Ben-Ari Reference Ben-Ari, Kaindl, Kolb and Schlager2021, 159; Reference Ben-Ari, Kaindl and Spitzl2014, 122; Reference Ben-Ari2010, 235–236).

Likewise, the notion of (in)fidelity is by now a cliché in translation theory, in close connection to the idea of equivalence. The myth of translation as a sameness-driven practice has been dispelled as one of ‘the innumerable fictions’ in Translation Studies (Kaindl Reference Kaindl and Woodsworth2018b, 161), an ‘untruth’ (Cronin Reference Cronin2000, 109). Lavieri (Reference Lavieri2007/2016, 67–69) counts equivalence, faithfulness, and literality among common misconceptions of translating, and Venuti (Reference Venuti, Abel and Végső2019, ix) explicitly traces the qualifier ‘faithful’ back to ‘the simplistic, clichéd thinking that has limited our understanding of it [translation] for millennia’. The fact that much effort has been put into demonstrating the fallacies on which the narrative of translation as simplistic replication is based is significant. It indirectly shows that the assumption under which translators operate is often that of translation conceived not as a transformative endeavour, but as an unvaried replication of its sources. The ‘equivalence supermeme’, in Chesterman’s words, ‘has continued to flourish’ (Reference Villeneuve2016, 14; emphasis in the original). This might indicate that the nebulous notion of ‘equivalence’ – and the expectations it comes with – is still a deeply rooted idea in the lay imagery of translation, which may subsequently percolate through fiction.

A common thread between these three topics is that, while attracting notable scholarly attention, they are not particularly well-defined and/or accompanied by detailed, interoperable descriptions. Consequently, they might appeal to both transfiction researchers and researchers in other areas of specialisation within Translation Studies precisely because they are flexible concepts, lending themselves to a variety of understandings. (In)fidelity, for example, has been used in connection to gendered roles in writing and translating (Arrojo Reference Arrojo, Cronin and Inghilleri2018, 133; Wilson Reference Wilson2009, 189), as well as being taken as a purposefully deviating strategy of mistranslation (Kripper Reference Kripper, Blakesley and Large2023, 6–7).

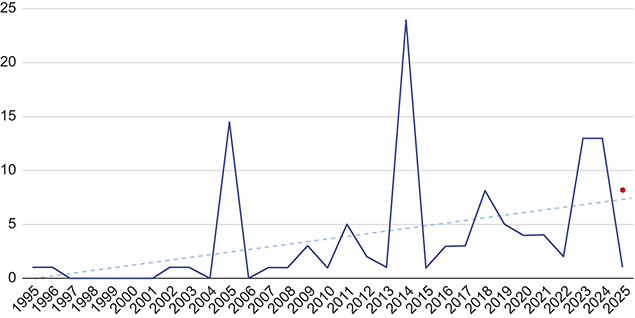

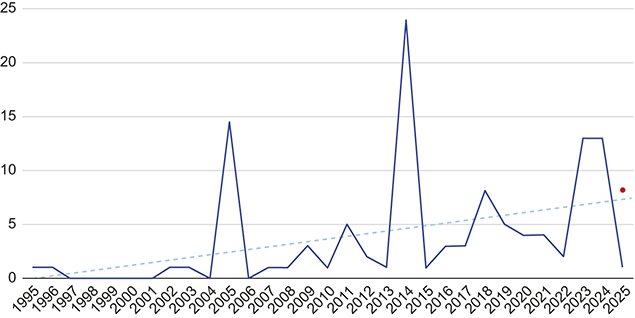

2.2 Transfiction Research in Time

The distribution of English-language publications in transfiction research in the time frame 1995–2025 is shown in Figure 2. The figure illustrates the development of this research line, which moved from scattered publications between 1995 and 2004 to a notable peak in 2005, followed by the highest concentration of publications in 2014. This number then drops considerably, to rise again more recently, between 2023 and 2024. The evolution of transfiction research in time captured in the figure is far from being gradual. The number of publications does not increase steadily. Instead, three main upward trends can be noticed, accompanied by periods of relatively little growth.

Figure 2 Distribution of transfiction publications in time

These trends are found in connection with 2005 (fourteen publications, equal to 12.4% of the corpus), 2014 (twenty-four publications, equal to 21.2% of the corpus), and 2023–2024 (thirteen publications each, and each equal to 11.5% of the corpus). Another increase can be seen in 2018 (eight publications, equal to 7.1% of the corpus). These peaks correspond to the years in which landmark studies in transfiction research were published.

The first attempt at systematically exploring what would later be called ‘transfiction’ was the fourth volume of Linguistica Antverpiensia edited by Delabastita and Grutman (Reference Delabastita and Grutman2005) under the title ‘Fictionalising Translation and Multilingualism’. This volume focused on ‘the two possible outcomes of language contact’, namely multilingualism and translation (Delabastita and Grutman Reference Delabastita and Grutman2005, 12), as opposed to considering the representations of translator-characters as a distinct phenomenon. At this stage, therefore, transfiction was conflated with the ‘fictional representations’ of both topics (ibid., 14). This special issue, which challenged strict disciplinary boundaries to embrace linguistics, history, and sociology, arguably resulted in enhanced visibility of fictional translators as a phenomenon worth exploring, as well as in enhanced systematisation. The general and descriptive terminology used by Delabastita and Grutman was then also used in other book chapters and articles (e.g., Kaindl Reference Kaindl, D’hulst and Gambier2018a, Reference Kaindl, Angelelli and Baer2016; Wakabayashi Reference Wakabayashi2011). It is significant that the first time the Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies included an entry dedicated to fictional representations was in 2009, four years after the 2005 thematic issue of Linguistica Antverpiensia, reiterated in its latest edition (Delabastita Reference Delabastita, Baker and Saldanha2009, Reference Delabastita, Baker and Saldanha2020).

Acknowledging the work of Delabastita and Grutman, Cronin drew attention ‘to translators not so much as agents of representation but as objects of representation’ in films (Cronin Reference Cronin2009, x). Beebee’s notion of ‘transmesis’ followed (Reference Beebee2012), and it arguably contributed to consolidating this subfield, straddling Translation Studies and Literary Studies. ‘Transmesis’, nevertheless, does not refer precisely or solely to the representation of translators in fiction. Instead, it denotes ‘the mimesis of the interrelated phenomena of translation, multilingualism, and code-switching’ (Beebee Reference Beebee2012, 6). The collection Transfiction: Research into the Realities of Translation Fiction, edited by Kaindl and Spitzl (Reference Spitzl, Kaindl and Spitzl2014), was published two years later. In its introduction chapter, Kaindl (Reference Kaindl, Kaindl and Spitzl2014, 4) contextualises the phenomenon of transfiction, as well as providing its definition along with a description of the collection’s scope:

[o]n its journey through different contexts and uses, translation now has become a central motif and topic of the narrative arts, of literature and film. This development is doubtlessly rooted in the mobility of the concept, its changeability and its many layers of meaning. Thus, this present volume focusses on transfiction, i.e. the introduction and (increased) use of translation-related phenomena in fiction. It investigates what this development means for translation studies, what theoretical and methodological issues it raises, and how we might respond to them.

Since then, the term transfiction has been used regularly to denote the phenomenon under discussion, becoming entrenched in academic usage via international conferences and the publications originating from them (Ben-Ari and Levin Reference Ben-Ari and Levin2016, 339; Kolb, Pöllabauer, and Kadrić Reference Kolb, Pöllabauer, Kadrić, Kadric, Kolb and Pöllabauer2024, 12; Kripper Reference Kripper, Blakesley and Large2023, 5; Miletich Reference Miletich and Miletich2024a, xvii; Woodsworth Reference Woodsworth, Kaindl, Kolb and Schlager2021, 293; Woodsworth and Lane-Mercier Reference Woodsworth, Lane-Mercier and Woodsworth2018, 3). In the same foundational volume, Spitzl (Reference Spitzl, Kaindl and Spitzl2014, 364–365) summarises Kaindl’s definition of transfiction as ‘an aestheticized imagination of translatorial action’, placing an emphasis on the embodied experience of translation, as opposed to the ‘dehumanization of theories and concepts’. It was not until 2014, therefore, that fictional representations of translators and language mediation were taken as research topics not necessarily dependent on or interwoven with forms of multilingualism (cf. Sternberg Reference Sternberg1981), and in purely abstract terms.

To date, the highest number of publications in transfiction research occurred in 2014, which is reflective of the edited collection, Transfiction (Kaindl and Spitzl Reference Kaindl, Spitzl and Gambier2014) being a designated space for the establishment and dissemination of transfiction research, gathering a total of twenty-four contributions. Other book-length publications followed, with some of them intentionally trying to go beyond transfiction. These publications included contributions on translation phenomena that problematise traditional dichotomies between ‘original’ and translation, author and translator, and other ‘fictions of translation’ as opposed to transfiction (Woodsworth and Lane-Mercier Reference Woodsworth, Lane-Mercier and Woodsworth2018, 4). This research trend can be summarised in the following question, asked by Rosenwald (Reference Rosenwald2016, 358): ‘What model of the relation between author and translator would we create if we acknowledged from the start that there was no way to distinguish in essence between the two persons, roles, activities, speech acts?’

In 2023 and 2024, where the latest upward trends in the number of publications can be observed, three other book-length publications appeared, a monograph (Kripper Reference Kripper, Blakesley and Large2023) and two edited collections (Miletich Reference Miletich2024b; Spitzer and Oliveira Reference Spitzer and Oliveira2023). Rather than continuing to push the boundaries of the definition of transfiction, these publications went back to the idea of fictional representations of translators and translation, while also conceptualising transfiction as an ‘approach to theorizing translation’ that ‘foregrounds aspects of literary texts that might otherwise pass unnoticed or without sufficient interpretive scrutiny’ (Spitzer Reference Spitzer, Spitzer and Oliveira2023, 3; emphasis in the original).

As shown in Figure 2, the number of publications drops suddenly in 2025. This sharp drop is likely due to this research being conducted in the same year and the time constraints this implies. It is possible that more transfiction research will be published in 2025, but these publications are not captured here because the data collection phase of this meta-analysis was completed prior to their release. Figure 2 shows a trend line signifying an average calculated based on the count of publications per year, as well as a data point in relation to 2025. This point represents a forecasted value taking into account the trend over the last thirty years and projecting this trend into the future. This projection estimates that the number of transfiction publications in 2025 will be approximately eight, subject to the continuation of current trajectories. Irrespective of exact numbers, the number of publications is expected to drop again, which reinforces the fluctuating pattern observed over the last thirty years.

Collectively, the publications which appeared in conjunction with the peaks illustrated in Figure 2 can be taken as research-defining because they marked a shift in the study of transfiction from a vastly unsystematic, anecdotal, and incidental approach to establishing a subfield with its own specificity. However, it would be simplistic to assume that a higher number of publications is directly connected to the impact or significance of the same publications. Fewer publications may have been published in periods which do not constitute an upward trend in the number of published research outputs, while still being significant for the development of the field. Further hypotheses on this situation can be made based not only on the number of publications, but also on the forms they have taken.

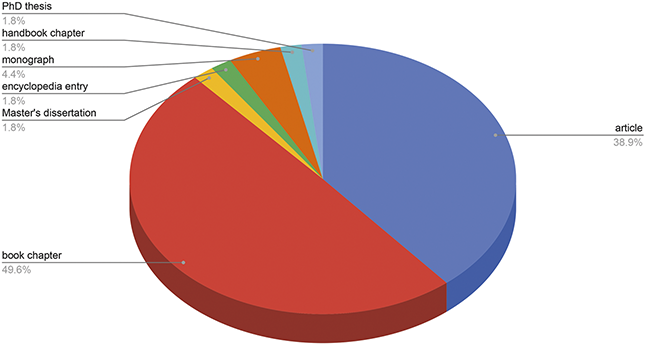

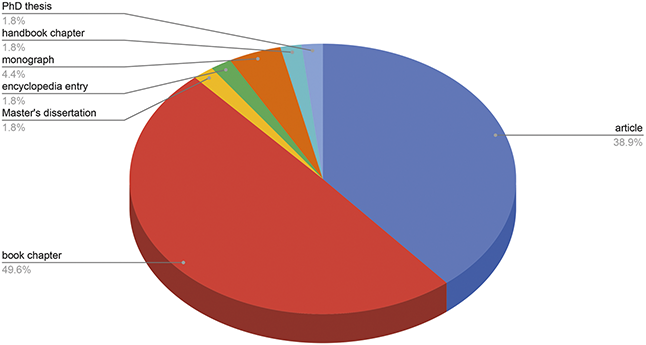

2.3 Types of Publication

Book chapters represent the most frequent type of publication in transfiction research over the last thirty years, as is apparent in Figure 3. The bibliographic search identified fifty-six book chapters, constituting almost half (49.6%) of the publishing landscape in transfiction research. The second most frequent publication type is journal articles: forty-four articles were identified, accounting for 38.9% of the corpus. Four monographs, that is, book-length publications authored by a single researcher, instead, make up 4.4% of the corpus. References like encyclopaedia entries and handbook chapters constitute 3.6% of the corpus, with the same percentage being represented by student work, including master’s dissertations and PhD theses. The underrepresentation of student work might depend on its lesser visibility on research engines like Google Scholar than those of research articles, as it is typically stored in institutional repositories. Another reason might be the notably peripheral position of fictional representations in Translation Studies syllabi, which results in students not being exposed to this topic as much as they are to core translation theories. It is indicative, for example, that fictional representations are not dealt with in classic reference points of the Translation Studies class, such as the various editions of Introducing Translation Studies (Munday, Pinto, and Blakesley Reference Munday, Pinto and Blakesley2022) and The Translation Studies Reader (Venuti Reference Venuti2012).

Figure 3 Publication types

It is noteworthy that Figures 2 and 3 would both look quite different, were German-language publications added to the corpus. These include collections edited by Kaindl and Kurz (Kaindl and Kurz Reference Kaindl and Kurz2010b, Reference Kaindl and Kurz2008, Reference Kaindl and Kurz2005), each gathering between twenty-two and twenty-five chapters authored by different contributors. Adding these publications to the English-language dataset would have a significant impact on the quantification process and the related results, leading to a more homogenous distribution of publications in the five-year period 2005–2010. This addition would also confirm that book chapters are by far the prevailing form of publication in transfiction research. Counting handbook chapters together with the more general category of ‘book chapters’ would also lead to similar consequences. Including non-English-language work by Hagedorn (Reference Hagedorn2006), Lavieri (Reference Lavieri2007/2016), Strümper-Krobb (Reference Strümper-Krobb2009), Wilhelm (Reference Wilhelm2010), and Babel (Reference Babel2015), instead, would lead to a higher number of monographs, while confirming the dominance of books over articles.

The fact that book chapters, along with articles, constitute the majority of publications in transfiction research reflects trends in the Translation Studies publishing ecosystem. A discipline-specific analysis conducted on BITRA (the Bibliography of Interpreting and Translation) reveals that ‘journal articles are … the most numerous research output in TS … However, books and book chapters together account for 53.6% of the outputs from 1951 up to the present [2019], whereas journal articles account for 46.3% in the same period’ (Rovira-Esteva, Aixelá, and Olalla-Soler Reference Rovira-Esteva, Aixelá and Olalla-Soler2019, 163). In addition, while journal articles are the most frequent type of publication in Translation Studies, ‘books and book chapters together are the document types cited the most’ (ibid., 168).

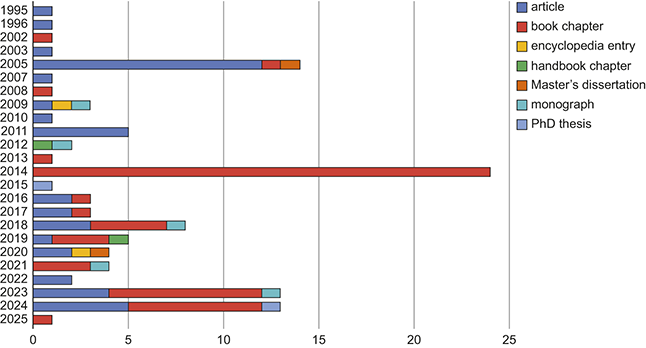

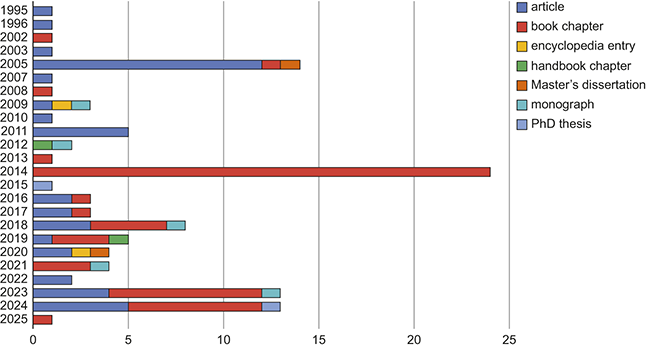

The distribution of publication types over the last thirty years is illustrated by Figure 4.

Figure 4 Publication types 1995–2025

Correlating the year of publication with the type of publication, Figure 4 shows that 2005 and 2014 saw the highest number of articles and book chapters published, respectively. As discussed earlier, a dedicated volume of Linguistica Antverpiensia (Delabastita and Grutman Reference Delabastita and Grutman2005) and the edited collection Transfiction (Kaindl and Spitzl Reference Kaindl, Spitzl and Gambier2014) appeared in these years. The same pattern can be observed in 2023 and 2024, with two other edited collections being released (Miletich Reference Miletich2024b; Spitzer and Oliveira Reference Spitzer and Oliveira2023).

Another observable pattern is that most articles and book chapters tend to appear in clusters. This tendency raises questions about the dissemination dynamics of transfiction research, not only in terms of publication venues, but also on the nature of this research per se. These grouped patterns, whereby the highest concentration of articles and book chapters appear in the same year, might be indicative of some sort of dependence of transfiction research on special occasions, rather than pointing to transfiction being an object of widespread scholarly engagement. The peaks shown in Figure 2 and the distribution of publication types over the last thirty years shown in Figure 4 might suggest that transfiction research depends on variables, such as a journal’s special issues, conferences, and calls for chapters. In turn, this supposed dependence might imply that research in the field has been driven by a relatively small group of researchers, as opposed to transfiction being of general interest in the Translation Studies community at large.

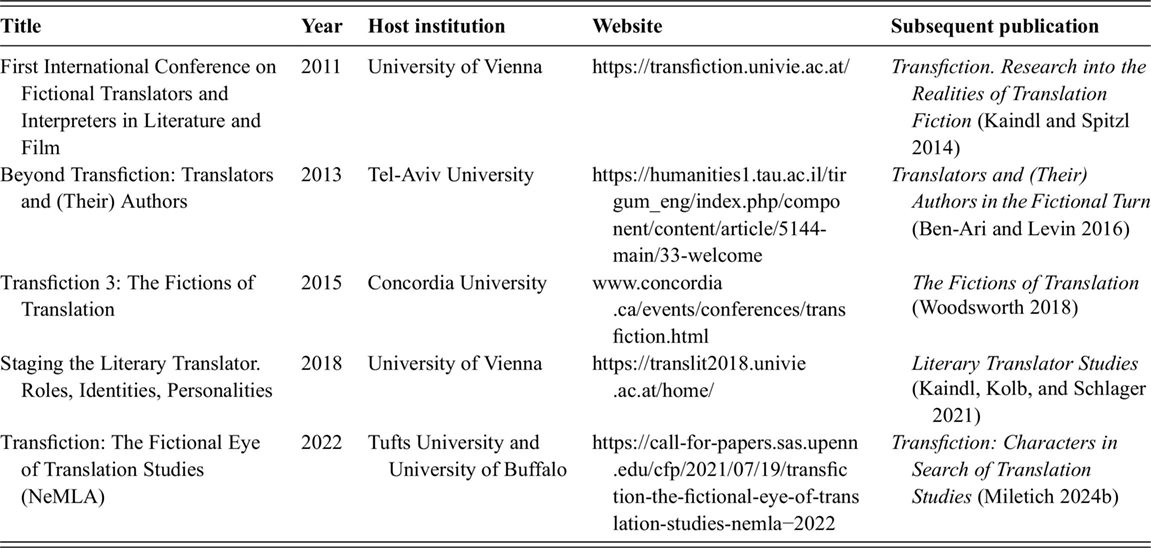

There have been at least five conferences either entirely dedicated to transfiction or showcasing transfiction research to a lesser extent, and as many research outputs (edited collections and special issues), which are more or less explicitly related to them (Ben-Ari and Levin Reference Ben-Ari and Levin2016, 339; Kolb, Pöllabauer, and Kadrić Reference Kolb, Pöllabauer, Kadrić, Kadric, Kolb and Pöllabauer2024, 12; Kripper Reference Kripper, Blakesley and Large2023, 5; Miletich Reference Miletich and Miletich2024a, xvii; Woodsworth Reference Woodsworth, Kaindl, Kolb and Schlager2021, 293; Woodsworth and Lane-Mercier Reference Woodsworth, Lane-Mercier and Woodsworth2018, 3). These are shown in chronological order in Table 2.

| Title | Year | Host institution | Website | Subsequent publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First International Conference on Fictional Translators and Interpreters in Literature and Film | 2011 | University of Vienna | https://transfiction.univie.ac.at/ | Transfiction. Research into the Realities of Translation Fiction (Kaindl and Spitzl Reference Spitzl, Kaindl and Spitzl2014) |

| Beyond Transfiction: Translators and (Their) Authors | 2013 | Tel-Aviv University | https://humanities1.tau.ac.il/tirgum_eng/index.php/component/content/article/5144-main/33-welcome | Translators and (Their) Authors in the Fictional Turn (Ben-Ari and Levin Reference Ben-Ari and Levin2016) |

| Transfiction 3: The Fictions of Translation | 2015 | Concordia University | www.concordia.ca/events/conferences/transfiction.html | The Fictions of Translation (Woodsworth Reference Woodsworth and Roberto2018) |

| Staging the Literary Translator. Roles, Identities, Personalities | 2018 | University of Vienna | https://translit2018.univie.ac.at/home/ | Literary Translator Studies (Kaindl, Kolb, and Schlager Reference Kaindl, Kolb, Schlager and Valdeón2021) |

| Transfiction: The Fictional Eye of Translation Studies (NeMLA) | 2022 | Tufts University and University of Buffalo | https://call-for-papers.sas.upenn.edu/cfp/2021/07/19/transfiction-the-fictional-eye-of-translation-studies-nemla−2022 | Transfiction: Characters in Search of Translation Studies (Miletich Reference Miletich2024b) |

While publications resulting from these events do not focus exclusively on transfiction, the concentration of most journal articles and book chapters in this subfield within the three-year period following each of them supports the hypothesis that transfiction research has tended to rely on specific initiatives, rather than being a mainstream area of study. Further evidence for this hypothesis can be drawn from a large-scale thematic analysis of topics recurring with high frequency in Translation Studies in the period 1972–2021, where there is no room for transfiction and/or other terms referring to the same phenomenon (Olalla-Soler, Aixelá, and Rovira-Esteva Reference Olalla-Soler, Aixelá, Rovira-Esteva, Aixelá and Olalla-Soler2022, 24). Another bibliometric analysis of Translation Studies from 2014 to 2018 reinforces this hypothesis, as transfiction as a phenomenon is not listed among the most frequently explored research topics (Huang and Liu Reference Huang and Liu2019, 41–43).

2.4 Research Designs and Methodologies

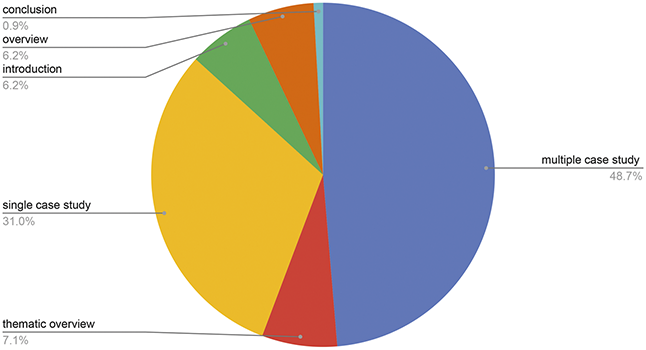

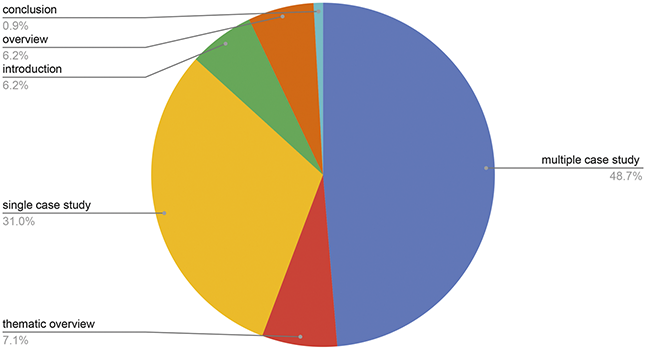

Figure 5 leaves little room for interpretation as to what the most frequent research design is in transfiction research, with case studies constituting almost 80% of the corpus. While the ‘introduction’ (seven publications) and ‘conclusion’ (one publication) designs are self-explanatory, this may not be the case for the other categories of research designs. So, before discussing the overwhelming majority of case studies, the other three research designs included in the figure are described.

‘Case studies’ (90 publications) of transfiction are understood here as in-depth analyses of one or a small group of literary texts featuring language mediators, in the context of which qualitative methods and philosophical argumentation are typically adopted to substantiate the analysis. Their titles tend to follow formulaic patterns, which can be summarised as ‘phenomenon being considered’ + ‘in’ + ‘name of author(s)’ + ‘titles of primary sources’ or ‘qualifier + fiction’.

Much like ‘introductions’, the category ‘overviews’ (seven publications) refers mostly to reference publications, such as handbook chapters and encyclopaedia entries, which offer a digest and background information in terms of chronological developments and main topics within the subfield, with the function of contextualising transfiction as a phenomenon and object of enquiry. Unlike ‘introductions’, they do not introduce edited collections or a journal’s special issue.

‘Thematic overviews’ (eight publications) differ from general ‘overviews’ in that they do not aim to outline the different connotations of transfiction as a general phenomenon or the history of its development. Instead, they outline and discuss a number of topics emerging from their primary sources, without producing a concentrated analysis of any of them, specifically. This concentrated analysis, instead, is what characterises case studies.

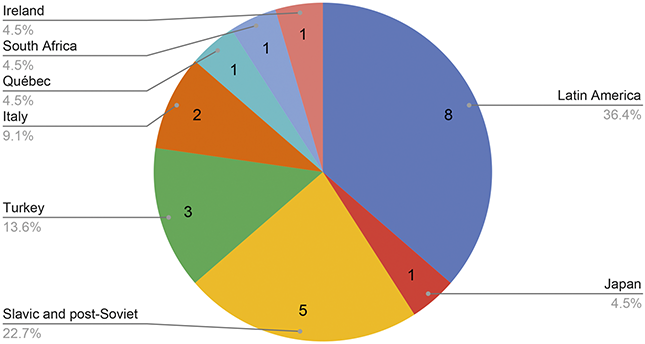

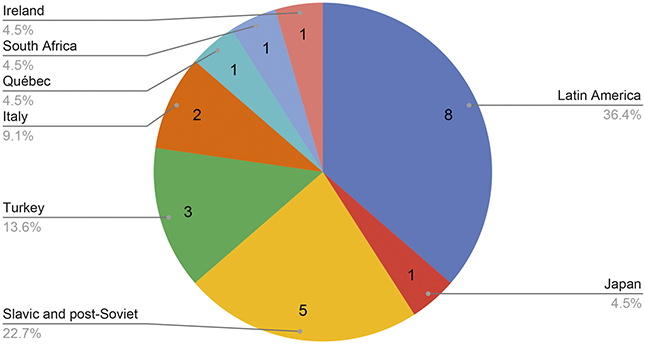

Another design emerging from the corpus is represented by a subgroup of twenty-one ‘area-specific studies’, in the context of which a case can be represented both by literary texts and/or the areas being explored. These studies embed their primary sources into a wider geographical region, contextualising these texts in the culture and literary tradition of this area, instead of selecting sources across diverse contexts based on their thematic analogies. A breakdown of these studies is provided by Figure 6, where the percentages refer to this subgroup of twenty-one publications, as opposed to the entire corpus. Publications were assigned to this subgroup not solely based on the country or language of origin of the author of the primary sources being examined, or on the setting of these sources. This choice would have led to all publications being somehow specific to a certain area. Instead, area-specific studies were grouped together based on the researcher’s explicit aim to investigate transfiction originating in specific contexts and contextualising their analysis in the histories and cultures of those contexts. It is not surprising to see Latin American transfiction being the most frequently investigated case in this subgroup (36.4% of area-specific studies). The paramount importance of translation in Latin American cultures has been addressed by several scholars (Arrojo Reference Arrojo, Kaindl and Spitzl2014; Cleary Reference Cleary, Baer and Woods2021; Gentzler Reference Gentzler2008; Giraldo and Piracón Reference Giraldo, Piracón, Spitzer and Oliveira2023; Kripper Reference Kripper, Blakesley and Large2023; Pagano Reference Pagano, Tymoczko and Gentzler2002; Strümper-Krobb Reference Strümper-Krobb2022; Valdeón Reference Valdeón2011), with translation being held to be ‘not a trope but a permanent condition in the Americas’ (Gentzler Reference Gentzler2008, 5). ‘[I]t was in Brazil’, as Woodsworth and Lane-Mercier (Reference Woodsworth, Lane-Mercier and Woodsworth2018, 1) point out, ‘that attention was first drawn to a new ‘turn’ in translation studies’, which was then labelled ‘fictional turn’.

Figure 5 Research designs

Figure 6 Area-specific studies

2.4.1 Why Cases?

When a case study of transfiction focuses on one text, it is referred to here as ‘single-case study’, whereas when two or more sources are taken into consideration, a case study is described as ‘multiple’, following the terminology proposed by Susam-Sarajeva (Reference Susam-Sarajeva2009). The corpus includes fifty-five publications presenting multiple case studies of transfiction and thirty-five publications presenting single cases. The dominance of case-based research in transfiction reflects ‘the way that much translation studies research takes place today’ (Hadley Reference Hadley2023, 12). A characteristic of the corpus of transfiction publications under scrutiny that does not align with existing patterns in Translation Studies is the specific type of case studies. While Susam-Sarajeva (Reference Susam-Sarajeva2009, 43) noted that multiple case studies are rarely conducted in the field, 48.7% of the corpus under analysis is made up of multiple case studies. These come with more advantages than single cases ‘in terms of the rigour of the conclusions which can be derived from them’ (Susam-Sarajeva Reference Susam-Sarajeva2009, 44).

Whereas the reasons behind an introduction or a handbook chapter may be more directly identifiable with contextualising the research area and introducing or justifying a special issue or a book-length publication, the choice of the case study design in the corpus is often left unjustified. Therefore, even remaining cognisant of the different understandings and consequent implementations of case studies, the question remains: why cases?

A more or less conscious appeal to tradition, whereby researchers in transfiction continue to produce case studies simply because this has historically been the most frequently adopted design in this specific subfield and in Translation Studies in general might help answer this question. However, it would be, at the same time, quite a facile solution, as well as a logical fallacy on the part of the researchers involved.

A more likely reason could be found in the scope of the phenomenon. Despite the ‘veritable boom of translation and interpreting as literary themes and of translators and interpreters as characters that is no longer limited to certain literary or cinematographic genres’ (Kaindl Reference Kaindl, Kaindl and Spitzl2014, 4), the actions of translator-characters in creative texts can be more or less apparent and/or pivotal in the unfolding of a plot. In this respect, Wakabayashi points out that relevant passages in her sources were ‘fairly isolated references’ in comparison to the initial corpus of texts she had identified (Reference Wakabayashi2011, 88). Ben-Ari (Reference Ben-Ari2010, 225) makes a similar observation, noting how passages dedicated to translation in her corpus of transfictional sources can be limited to ‘a few passing remarks’. If combined with the fact that transfiction is not marketed as a distinct genre, it could be the case that, at least in the early stages of this research area, finding instances of transfiction was enough to ignite researchers’ curiosity. It is perhaps this often ‘serendipitous stumbling’ (Wakabayashi Reference Wakabayashi2011, 101) into translation scenes that has resulted in most transfiction research developing as a long series of more or less scattered case studies. In other words, scenes of translations might be perceived as curious cases worth investigating in isolation or in small groups precisely for their perceived singularity. If these hypotheses are correct, transfiction researchers would follow the rationales behind single case studies outlined by Susam-Sarajeva (Reference Susam-Sarajeva2009, 44), who justifies them when they are ‘necessary to disprove a theory’, or considered to be ‘extreme’ or ‘unique’, or somehow ‘revelatory’. However, as pointed out earlier, the reasoning behind the choice of the case design is hardly ever explained in the corpus.

Another factor that may have influenced researchers to examine transfiction by means of case studies is the legacy of Comparative Literature in Translation Studies as a ‘polydiscipline’ cross-fertilised by a wide gamut of neighbouring, mostly text-based fields (Gambier Reference Gambier, D’hulst and Gambier2018, 182). The tendency to focus on cases is directly linked to the use of methods that can facilitate the interpretation of a relatively small amount of text, such as those passages of a narrative where translators are portrayed. In Literary Studies ‘the practices of close reading have operated … not as one method among others but as virtually definitive of the field’ (Herrnstein Smith Reference Herrnstein Smith2016, 58). This state of affairs is arguably reflected in Translation Studies as far as small-scale contrastive analyses between source and target texts are concerned, as well as transfiction research, where primary sources may not revolve entirely around translators. Close reading of literary texts has resulted in researchers grappling with the peculiarities of individual texts containing scenes of translation and taking them as cases, rather than identifying the underlying characteristics of transfiction as a phenomenon per se. This observation leads the discussion on to the methodologies employed in transfiction research over the last thirty years.

2.5 Methodologies

In the final chapter of the area-defining volume Transfiction, Spitzl (Reference Spitzl, Kaindl and Spitzl2014, 366) justifies a flexible methodological approach in researching transfiction, ‘an undisciplined encounter of approaches and methods, of bricolage (cf. Levi-Strauss Reference Levi-Strauss1966: 19), and multimodal eclecticism’. The same flexibility was echoed more recently by Delabastita (Reference Delabastita, Baker and Saldanha2020, 194), who recommends researchers resist ‘any undue striving for mono-disciplinary isolation’, because ‘[n]either the recourse to fictional texts nor the acute awareness of multilingualism and interculturality is an exclusive property of translation studies. Hence the need for a permanent dialogue with neighbouring fields such as literary studies, film studies, contact linguistics and multilingualism studies’.

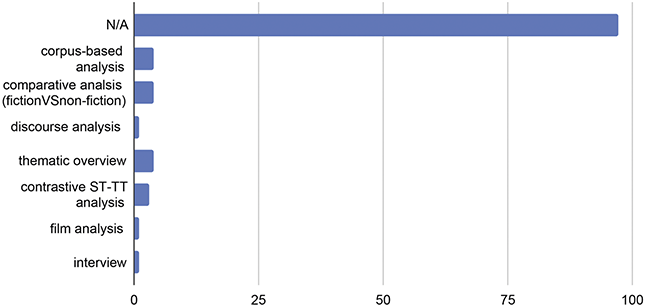

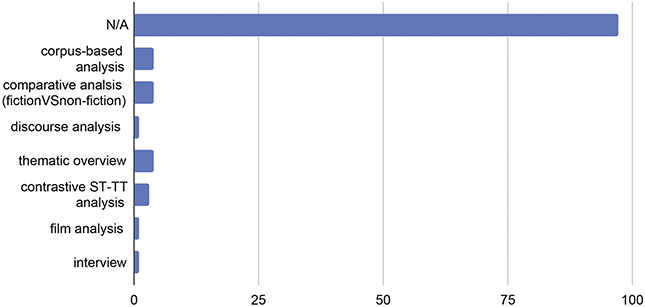

Although this methodological eclecticism has been theoretically justified, during the categorisation process of this research the fact emerged that methodological approaches and specific methods are hardly ever spelled out. So, readers are not given a reason as to what the affordances of this eclecticism may be and, consequently, how or in what other cases it may prove useful. This issue has been observed in other Translation Studies meta-research, too. In their meta-analysis of collaborative learning in translation and interpreting, Du and Salaets (Reference Du and Salaets2025, 7) note that ‘about half of the studies did not specify which specific analysis method was followed’. This percentage is dramatically higher in the corpus of transfiction research analysed here, where 97 research outputs (84.3%) do not specify what their methodological approaches and/or procedures are. These are labelled ‘N/A’, as illustrated in Figure 7, because no straightforward methodology or set of methods were identifiable either in the abstract or in the introduction section of the respective publication.

Figure 7 Methodologies

Before finding possible explanations for the distinct lack of clearly defined methodologies, the other categories represented in Figure 7 are introduced:

‘Corpus-based analyses’ (3.5%) are labelled this way because their respective authors explicitly mention the term ‘corpus’, as they all draw on a body of literature appearing to count at least thirty transfictional sources. Whether computational methods were used in analysing these sources, as the use of the term ‘corpus’ may suggest, is left to interpretation, as the authors do not disclose or reflect on the specific methods they employed. Likewise, they do not systematically provide forms of quantification. So, ‘corpus-based’ is likely to refer to a relatively large number of primary sources, as opposed to methods derived from corpus linguistics.

While comparison in general can be taken as an inherent component of multiple case studies, ‘comparative analysis (fiction VS non-fiction)’ (3.5%) refers to publications that compare the fictional treatment of translation and translators with their non-fictional representations.

‘Thematic overviews’ (3.5%) as a methodological approach differ from the ‘thematic overview’ as a research design. As a design, thematic overviews discuss a series of themes found in conjunction with transfiction without engaging closely with individual primary sources. As a methodology, ‘thematic overviews’ are provided in the context of case studies, which are typically multiple case studies where each source is examined in detail. Therefore, these publications present the researchers’ argumentation propped up by examples. This approach is flagged as problematic by Susam-Sarajeva (Reference Susam-Sarajeva2009, 41), who explains that ‘when a unit of analysis is treated as an example, it serves the general claims of the scholarly publication, as the author ‘filters out’ those examples which best support his/her main arguments’.

‘Contrastive ST-TT analyses’ (2.6%) include research comparing transfiction sources and their translations.

‘Discourse analysis’, ‘film analysis’, and ‘interview’ each represent 0.9% of the corpus, with each approach being found in 1 publication. In particular, ‘film analysis’ does not refer only to films being primary sources, but to the use of methods derived from Film Studies.

2.5.1 Wading the N/A

The fact that the vast majority of publications in the corpus do not directly describe any specific methodological procedures raises a series of questions. Is a missing methodology indicative of researchers not considering it as an essential part of an abstract and/or an introduction section? Or does transfiction research follow a certain methodology that has become so entrenched over time that it does not need an explicit description? Are primary sources taken as more relevant than the methods used to examine them? What could N/A look like, in practice?

A methodological approach that is not captured explicitly, but can be inferred from the overview of research designs is ‘comparison’. 48.7% of the corpus is made up of multiple case studies that engage with two or more primary sources. In bringing multiple sources together, a phenomenon is observed from the different perspectives offered by each source, so that a comparison of some kind between these materials is unavoidable, whether this is directly addressed or not.

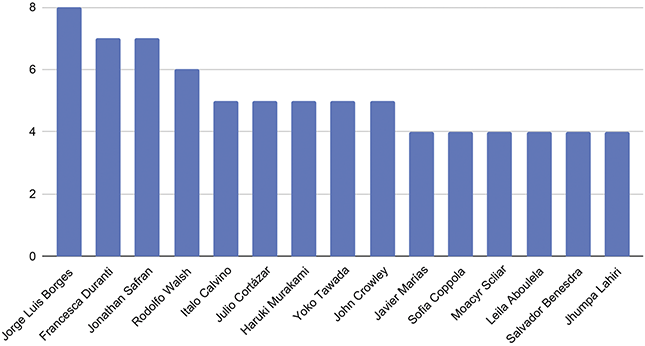

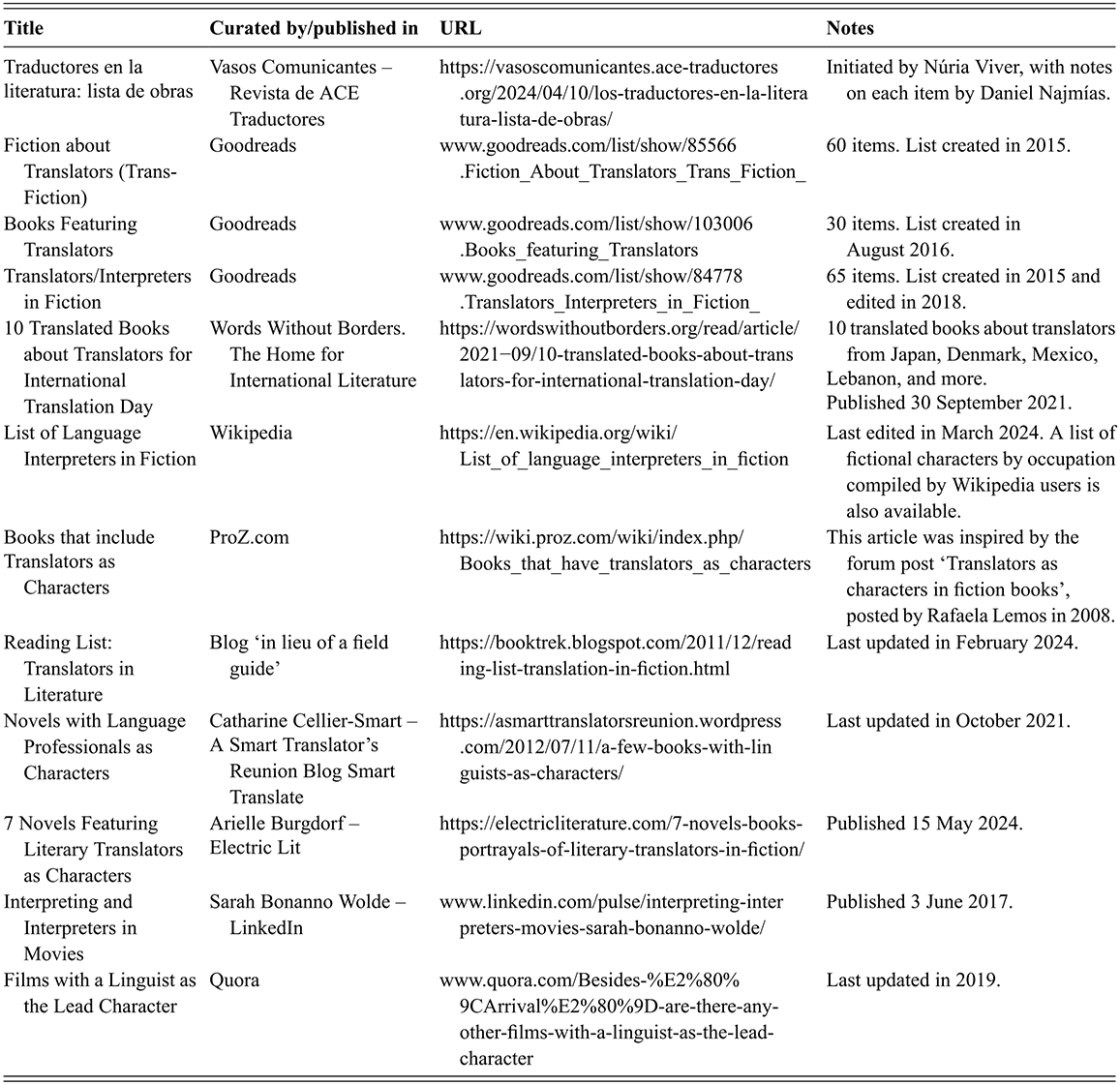

Kaindl (Reference Kaindl, D’hulst and Gambier2018a, 52) observes that ‘[m]uch like translation is seen as a multi-disciplinary concept …, the question of its fictional representation is also the subject of various disciplinary approaches – each with their own research questions and methodologies’. Considering the influence of Literary Studies on transfiction research, it might follow that close reading has also had a strong impact on the way transfiction has been examined. If close reading has been ‘virtually definitive of the field’ (Herrnstein Smith Reference Herrnstein Smith2016, 58), then researchers straddling Comparative Literature and Translation Studies might have resorted to close reading techniques by default when analysing translator stories. Cronin (Reference Cronin2009, 94) reports that ‘[i]t is generally accepted in translation pedagogy that all good translation involves close reading’. In this scenario, close reading appears to be a tacit methodological agreement in transfiction research. This seems to be the case even when transfiction research operates on a relatively large body of materials, rather than employing distant reading or other methods, as hypothesised for the ‘corpus-based analysis’ category. This seemingly automatic approach is not exclusive to the research areas considered here. ‘[H]owever, this particular methodology is often exempt from discussion when we reflect upon our methods’, even though it is ‘closely connected to the development of hermeneutics’ and how we glean meaning out of texts (Ohrvik Reference Ohrvik2024, 240, 242). Existing definitions of close reading revolve around ‘the practice of … examining closely the language of a literary work or a section of it’ (Culler Reference Culler2010, 20), with a focus on paratexts, stylistic idiosyncrasies, intertextuality, multiple meanings, and other rhetorical devices (Culler Reference Culler2010, 22; Klarer Reference Klarer2004, 86; Ohrvik Reference Ohrvik2024, 250; Rigney Reference Rigney, Wurth and Rigney2019, 109). This diverse set of indications suggests that the umbrella term ‘close reading’ conflates a series of understandings and procedures hinging on the scrutiny of text. Some of these procedures are laid out by Kaindl (Reference Kaindl, Kaindl and Spitzl2014, 15–16), who pins down one aspect around which the organisation and analysis of materials can then revolve. These pivotal aspects include genre, historical and cultural contexts, single authors or groups of writers, and topics and functions associated with translation as a theme.