1 Introduction

The global economy lay in ruins at the end of the Second World War. More than five years of conflict had decimated economies and societies across the world, whether through direct military bombardment or through pervasive shortages of key goods as international trade was severely disrupted in some places, and ground to a halt in others. With the end of the war, national and global efforts were redirected from waging war or simply surviving the conflict, to reconstruction and development. The challenges, while monumental, were similar across most spaces. Yet there was significant uncertainty about the optimal economic policy approach to chart a way forward, both to rebuild war-ravaged economies, particularly those at the center of the European and Asian war theatres, and to restructure newly emerging economies that were breaking free from colonial control and declaring independence as part of the decolonization wave that was sweeping across the world. The challenges facing developing countries were particularly compelling with the collective recognition that countries in the “periphery” faced a novel set of challenges with navigating a transformed geopolitical world order. Yet despite the commonalities in the economic policy problems that these countries faced, there were striking differences in the range of approaches that were adopted. Why was this so? Why do policymakers facing similar challenges make different economic policy choices?

Brazil and India Compared

Brazil and India serve as excellent cases for comparative analysis of the variation that arises in approaches to economic policy and development strategy. Postwar India and Brazil are both considered as epitomes of the statist developmentalist and nationalist economic policies that characterized much of the developing as well as advanced industrialized world in the wake of the Second World War (1945–1960). Both countries were intent on promoting rapid industrial development as a means of raising national incomes and establishing economic sovereignty in a neo-imperialist global political economy, and they also faced similar challenges with accessing finance and technology that were the keys to developing a modern industrial economy. As such, policymakers in both countries recognized that foreign direct investment (FDI) could play an important role in national development programs to promote economic growth and structural transformation. However, despite occupying similar structural positions in the global economy, facing similar material constraints, and being exposed to similar economic ideas and development strategies, India and Brazil pursued strikingly different approaches to regulating foreign investment. This variation is thus inadequately explained by conventional pluralist, structural-materialist, and even most constructivist approaches.

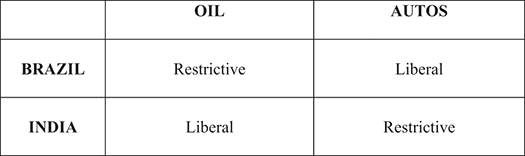

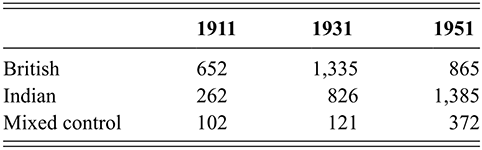

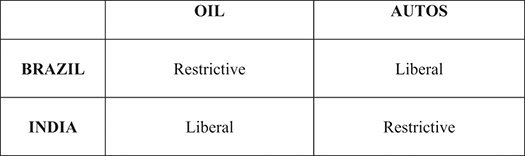

This Element analyzes this variation by comparing FDI policy approaches to sectoral development in natural resource extraction and manufacturing in both countries. India restricted FDI in manufacturing industries such as automobiles in order to facilitate the establishment of domestic business, but allowed multinationals corporations to establish dominant positions in natural resource-based sectors like petroleum. In contrast, Brazil welcomed foreign companies to launch its nascent automobile industry, but strongly prohibited FDI in oil. This was so even as policymakers in both countries were exposed to the same prevailing economic theories and policy ideas about how to promote industrial development and economic growth. This pattern of variation within and across both countries is summarized in Figure 1.Footnote 1 This Element thus addresses the following puzzle: Why did India and Brazil regulate FDI in such strikingly different ways?

Figure 1 Contrasting patterns of foreign direct investment policy in Brazil and India

This Element argues that Brazil and India developed distinct forms of economic nationalism. These were outcomes of social and political contestation arising from their contrasting colonial and early independence experiences. In Brazil, a “natural resource” form of economic nationalism emerged from a deep-seated belief in the existence of vast mineral riches, including oil, coupled with a powerful sense that neo-imperial forces were ruthlessly seeking to control them.Footnote 2 By contrast, in India a “manufacturing” form of economic nationalism emerged from the belief that British colonialism deindustrialized India, derailing it from its natural path to industrial development. This was based on the idea that Indian artisans had world-renowned technical skills in areas such as textiles and dyes that were superior to those in the West well before the arrival of the British East India Company. In this view, it was the imposition of British “free trade” policies under colonial rule that destroyed these skills and stymied the development of Indian industry. These contrasting sources of nationalist beliefs had crucial importance for the regulation of key industries in the postwar period when the industrial foundation of both countries was being established. These are briefly previewed next and elaborated throughout the Element.

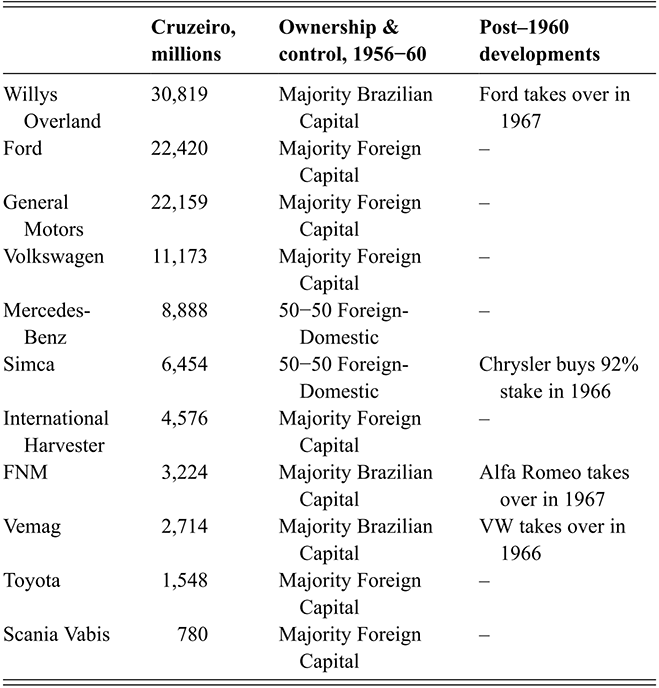

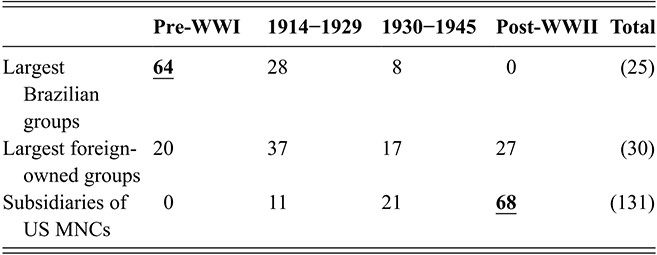

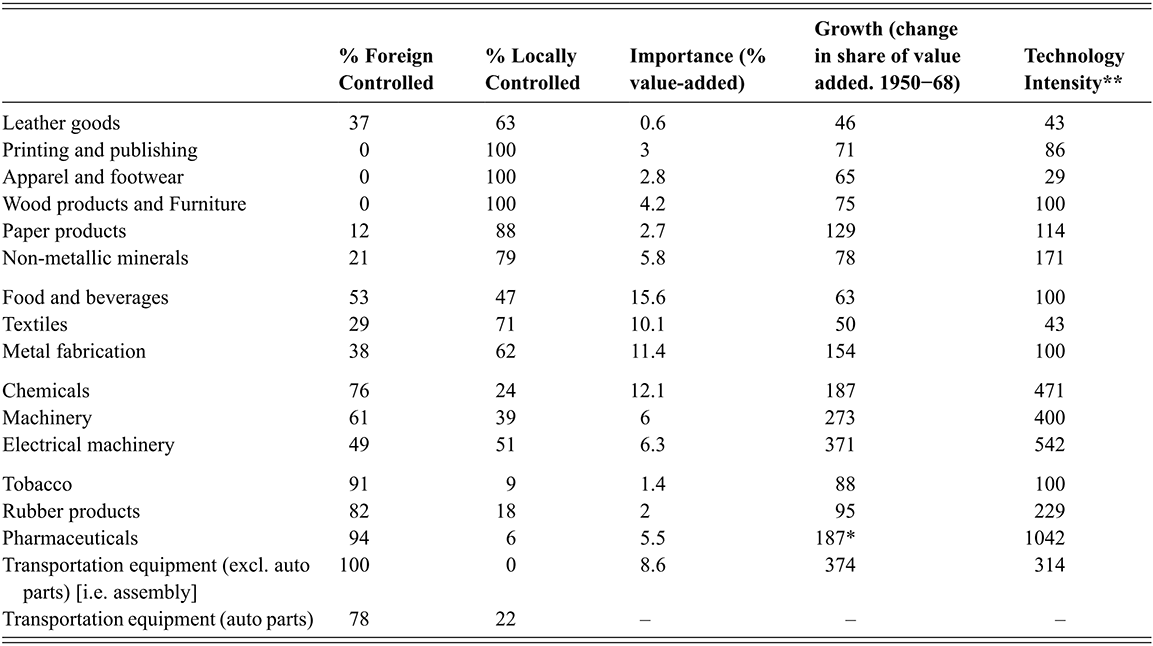

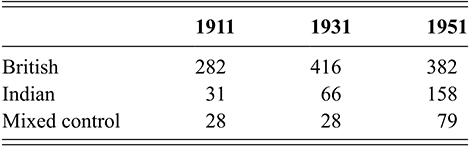

Automobiles

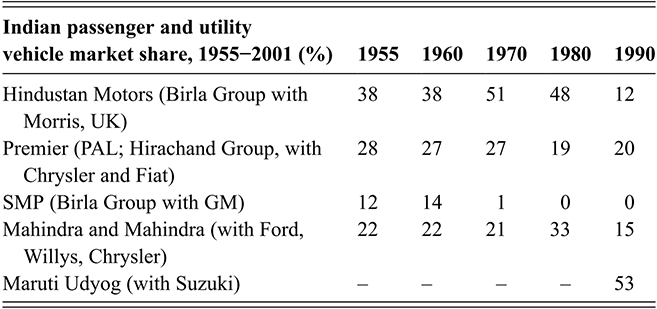

Brazil is well known to have actively encouraged foreign firm entry as a central part of its strategy to establish a motor vehicle industry. However, this approach involved suprisingly little effort to promote domestic firms as lead assemblers. Instead, multinational corporations were encouraged to establish dominant positions at the apex of the industry while Brazilian firms were incorporated in subordinate roles either as minority investment partners in assembly firms or as component suppliers, typically in minority joint ventures with foreign firms. By contrast, foreign firms were important participants in the nascent Indian automobile industry, but were not allowed to establish positions of managerial control. Even a major multinational firm like General Motors, which had been operating in India from as early as the 1920s, was forced to exit India after independence as private domestic firms such as Hindustan Motors, Tata Motors, and Premier Motors were promoted as vehicle assemblers and as component suppliers. Foreign firms were only allowed to be minority joint venture partners with private Indian firms.

Oil

Comparative analysis of the development of the petroleum sector reveals entirely different approaches to engaging with foreign capital. While the Brazilian state welcomed foreign firms into the automobile industry, multinationals were excluded from the petroleum sector, albeit after extensive political wrangling over foreign firms’ role involving political elites, military officers, and societal groups, including labor and students. Instead, the state-owned Petrobrás was created with exclusive monopoly rights in exploration and refining, even though widely held optimism about the possible existence of large oil reserves was completely unfounded as there was no evidence of proven reserves at the time.

India took precisely the opposite approach. Conventional perspectives of India as a bastion of anti-foreign sentiment fail to explain why Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s government allowed the overseas oil “majors” – widely considered to be the most nefarious of the multinationals – to occupy a lead role in exploration, refining, and distribution of its petroleum resources.Footnote 3 Further, India took this surprisingly liberal approach to the oil multinationals at the same time that it was touting its role as a leader among newly independent states asserting the right to economic sovereignty and self-determination in settings like the 1955 Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung. Even more surprising is that India took these steps in a moment when the oil majors were being chastened by waves of expropriation and nationalization in other developing countries.

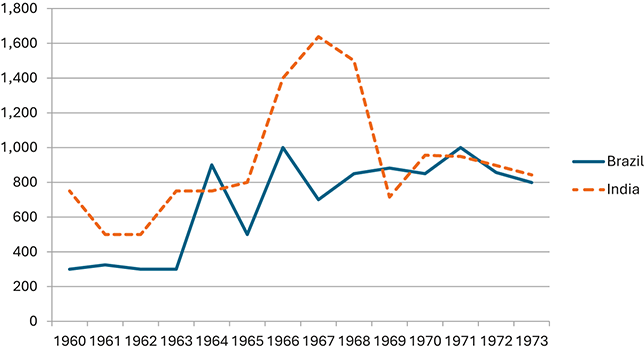

Petroleum may seem like an unusual case through which to compare industrial development in Brazil and India. Today, Brazil is well known as a global petroleum producer, while India rarely figures in conversations about oil. Yet this is somewhat misleading. India is currently ranked 24th in global proven reserves, while Brazil is 15th. In fact, India has greater proven reserves than well-known oil producing nations such as Indonesia and Oman, and India’s reserves are a more than half those of major global producers such as Mexico. Even more relevantly for this comparative study of the immediate postwar period, unlike Brazil, there was evidence that India might have oil reserves dating back to the nineteenth century and crucially, India had higher levels of proven oil reserves than Brazil for the first few decades of the postwar period. By contrast, Brazil’s major petroleum discoveries are largely a late twentieth-century phenomenon. Why then would postwar India be more open to foreign investment in the oil sector than Brazil? And conversely, why was Brazil willing to cede control of the auto industry to foreign firms while India sought to establish its own national producers?

To make sense of this puzzle this Element traces the emergence of contrasting economic nationalisms in both countries from the late nineteenth century through the early postwar period. This approach centers the role of colonial experience in shaping economic nationalist beliefs and ensuing economic policy outcomes. It does so by developing an explanatory framework that avoids privileging culture over materiality by recognizing the duality of subjective-cultural and objective-material determinants of foreign investment policy preferences, as well as the role of societal contestation in shaping the emergence of distinct forms of economic nationalisms in India and Brazil.

Economic Nationalism

Many observers see the recent return of economic nationalism as a paradox of neoliberal globalization. While economic nationalism had long been recognized as a fundamental feature of the global economy, until recently it was considered an artifact of nineteenth-century imperial rivalries that led to twentieth-century wars. In this view, the final flickering flames of economic nationalism were extinguished as the anti-colonial euphoria of the postwar decolonization wave of the 1950s–1960s met the grim realities of the twin oil shocks in the 1970s. This marked the beginning of an era of economic crisis, structural adjustment, and globalization that constituted the neoliberal turn. Economic nationalism was thus consigned to the dustbin of history.

Yet, a few decades later, economic nationalism is once again recognized as a defining characteristic of the contemporary global political economy. Nationalist fervor is raging across large and small countries in both the developing and industrialized world. Contemporary economic nationalism has taken on several distinct forms, ranging from nativist and ethnocentric nationalism in diverse settings across Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the United States, to neo-mercantilist nationalisms driven by escalating geopolitical rivalries between emerging and declining global powers. Indeed, these forms of economic nationalism are not mutually exclusive. They combine different ideas, ideals, and beliefs, often creating novel – if seemingly convoluted and often contradictory – forms of economic nationalism.

Twenty-first-century economic nationalist fervor was initially activated by the global financial crisis of 2007–8, which was characterized by national-level responses to what was fundamentally a crisis of the deeply interconnected global economy. Nationalist ferment grew through the 2010s with growing reactions to deeper structural features of the globalized world economy that was constructed in the 1980s and 1990s through neoliberal international trade and investment policies. These tensions reached crisis points with the sudden disruption created by the COVID-19 pandemic and deep societal inequalities that the pandemic laid bare, and persist with the growing range of social, political, and economic tensions and conflicts that are manifesting across the globe due to the climate crisis. Finally, all these have been exacerbated by the rise and pervasive use of digital technologies, which have created spaces for nationalist sentiment to grow, seemingly unchecked, as efforts to moderate online discourse are diluted or outright abandoned.

These developments have had concrete impacts on economic policymaking, making clear the need to understand contemporary economic nationalism in all its various manifestations. But our conceptual and analytic tools are not adequate for the task. Existing theories of economic nationalism provide oversimplified analyses that risk producing misleading conclusions about the role of nationalist beliefs in the economic policymaking process. This Element offers a different approach.

Chapter Organization

The rest of this Element is organized as follows. Section 2 offers a rigorous treatment of the relationship between economic interests and policy preferences, highlighting the strengths and limitations of currently dominant approaches. Section 3 builds on this foundation with a reconsideration of economic nationalism as a concept and a discussion of how the interdisciplinary scholarship on economic nationalism has evolved. A key element of economic nationalism is, of course, how nationalist beliefs are translated into economic policy preferences. With this foundation in theories of economic nationalism and policy preferences in place, Section 4 discusses the rationale for the case selection and the comparative approach that is adopted, highlighting the advantages of leveraging the Brazilian and Indian cases in the study of economic nationalism. The Element then turns to the sources of differing economic nationalisms in Brazil and India and the implications for the regulation of foreign direct investment and multinational firms in Section 5. It does so by providing a historical analysis of the origins and evolution of contrasting economic nationalisms in Brazil and India, highlighting the role of colonial experience in shaping different nationalist beliefs in both countries. This provides the foundation for the contrasting cases of the development of the oil and automobile industries in both countries, which are presented in Sections 6 and 7 respectively. The analysis in these two sections utilizes primary archival materials, particularly from diplomatic communiques between American consular and embassy officials in Brazil and India and their counterparts in the State Department in Washington DC. Consular officials played key roles in observing and assessing the investment climate in the countries where they were stationed, submitting frequent commentaries and reports and often serving as intermediaries between American businesses and local companies and government officials. As such, these documents provide a rich insight into the views of Indian policy and business elites, as well as the perspectives of American multinational firms that were considering investing in those countries or had active operations. Section 8 provides conclusions, including brief consideration of why economic nationalism leads to statist ownership in some country-industry cases, and private control in others using the example of the formation of the steel industry in both countries. It discusses some of the implications for understanding the role of economic nationalism in contemporary global developments and identifies important areas for future research.

2 Conceptualizing Economic Policy Preferences

Political science still asks all too rarely why an actor believed the means he adopted would have the effects he anticipated and where those beliefs originated. When we say that an actor, whether an individual or a government, took a particular set of actions to further his interests, even if we know what his interests were, we need to know why he had any reason to believe such actions would serve those interests well.Footnote 4

Preferences, interests, and ideas are key analytic concepts used to explain economic policy decisions and outcomes in comparative and international political economy and the political economy of development. This is especially so in the “new” institutionalisms, whether the rational choice, historical institutional, or sociological variants that simultaneously re-emerged as distinct paradigms in the 1980s and 1990s (Hall and Taylor, Reference Hall and Taylor1996). This renewed interest in the study of institutions – defined as rules and norms that shape social and individual behavior – has produced an increasingly fruitful interdisciplinary exchange in the social sciences.Footnote 5 This recognition revealed commonalities among the competing paradigmatic approaches to institutions that in turn has led to growing theoretical dialogue (Immergut, Reference Immergut1998; Thelen, Reference Thelen1999; Campbell and Pederson, Reference Campbell and Pederson2001; North, Reference North2005; Katznelson and Weingast, Reference Katznelson, Weingast, Katznelson and Weingast2005; Scott, Reference Scott2008; Hall, Reference Hall, Mahoney and Thelen2010). It has also become increasingly apparent in empirical work (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2000; Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2005; Greif, Reference Greif2006; Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2010).Footnote 6

The literature sees preferences, interests, institutions, and ideas playing an important role in shaping human action. Yet competing paradigms disagree on the constitution of actors, interests, and institutions, and the nature and direction of the causal relationship between them. This reveals a twin tension in what Immergut (Reference Immergut1998) referred to as the “theoretical core” of the new institutionalisms. There is a tension between materialist and constructivist sources of preferences and interests, and a tension between structure and agency. The location of different institutional approaches on each of these intersecting dimensions provides distinct theoretical predictions of the sources of interests and preferences that shape economic agents’ political behavior and produces policy and economic outcomes.

This Element focuses on the role of nationalist beliefs in shaping the institutions governing foreign direct investment (FDI) policy in postwar Brazil and India. Institutions and ideas play an important role in shaping actors’ FDI policy preferences by ascribing different roles to foreign and domestic firms in the Brazilian and Indian economies. But institutions themselves are created through dynamic and contested sociopolitical processes as actors struggle to shape the rules, norms, and beliefs that govern economic life.

Analyzing the role of economic nationalism in FDI policy reveals how competing theories predicting that economic and political actors’ policy preferences are naturally endowed, are determined by socioeconomic structural position, or are produced by rational calculation are misleading. Preferences toward FDI are neither fixed nor structurally determined; they are malleable and are created through ideas and beliefs that emerge from historical processes of social construction and political contestation.

Theorizing Preferences and Interests in Political Economy

Economic interests and policy preferences are fundamental conceptual building blocks in political economic analysis of the policymaking process. Preferences are central to accounts of purposive action, but leading scholars from different analytic traditions nevertheless lament that “preferences remain a relatively primitive category of analysis” (Katznelson and Weingast, Reference Katznelson, Weingast, Katznelson and Weingast2005). The challenges appear to be fundamental: “scholarly attention to the sources of national or sub-national interests – or, as we call them, preferences – is wrought with confusion” (Frieden, Reference Frieden, Lake and Powell1999: 39).Footnote 7 As such, it is critical to establish clear definitions of interests and preferences as distinct, though related, concepts at the outset of this analysis of economic nationalism and foreign investment policy.

In his rich intellectual history, The Passions and the Interests, Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1977) interrogates the rise of material interests as a historically specific political construct. The concept of “interests” served to facilitate the capitalist transition by taming the destructive “passions” of the sovereigns and promoting their “interests” in material gains through peaceful commerce. Hirschman defines interests as “valued ends.” Interests reflect the ultimate outcomes or states of being that economic actors want to achieve. Preferences and interests are intimately related: Preferences refer to economic actors’ conceptions of available alternatives that they believe will allow them to achieve their desired ends.Footnote 8 Ideas and beliefs about means–ends relationships, such as those positing a linkage between foreign investment policies and development outcomes, are thus central to the substantive content of policy preferences.

This content is provided by economic theories that posit causal relationships between FDI and development outcomes.Footnote 9 However, there are competing theories and ideas at play in the scholarly and policy literature on the developmental role of FDI. This reflects a crucial ambiguity that has long been at the heart of FDI policy conflicts: is foreign capital good or bad for development? This ambiguity creates space for political contestation between economic and political actors wielding competing ideas as they battle to shape the policy and institutional environment in their favor (Beland and Cox, Reference Beland, Cox, Beland and Cox2011). The process through which actors acquire those beliefs underpins the always-contested sociopolitical dynamics of preference formation (Hall, Reference Hall, Katznelson and Weingast2005: 155).Footnote 10

Structural Weaknesses: Deducing Policy Preferences from Structural Position

The conventional approach to determining policy preferences in comparative and international political economy – whether its rational choice or historical institutional variants – is to derive economic actors’ policy preferences from their structural position.

The widely held proposition that domestic incumbent firm preferences will lead them to lobby against FDI liberalization draws support from neoclassical economics. Neoclassical theory predicts that “supernormal” monopoly profits come from imperfectly competitive industries (Tirole, Reference Tirole1988). This provides incumbent producers in profitable concentrated industries with an incentive to prevent entry of competitors to protect their monopoly profits (Stigler, Reference Stigler1971). Private interests are thus expected to organize and lobby for the private non-welfare maximizing benefits of protection (Olson, Reference Olson1965; Stigler, Reference Stigler1971; Peltzman, Reference Peltzman1976; Grossman and Helpman, Reference Grossman and Helpman1994).

In this view, multinational corporations (MNCs) pose a serious competitive threat to domestic incumbents, particularly those located in developing countries. MNCs are conceptualized as an organizational manifestation of transnational capital that is seeking higher returns on firm-specific assets, that is, resources that a given firm owns or controls, including physical assets such as land, machinery, and buildings as well as intangible assets such as knowledge, technologies, capabilities, and organizational routines and practices. While international portfolio capital expects to capture returns via the theory of factor price equalization (the process by which the prices of factors of production are expected to equalize across countries through international trade), owners of firm-specific capital are vulnerable to incomplete contracting problems (where contracts between firms may not account for all possible contingencies) and thus avoid arms-length market transactions. Establishing a physical presence in foreign markets through FDI is an organizational solution to securing returns on firm-specific assets such as proprietary technology, production capabilities, or brand name. Multinational firms thus set up operations in foreign countries and “go it alone.”

Once established in a new country context, particularly when characterized by an underdeveloped industrial sector such as in most newly independent countries, multinationals can have major disruptive effects on the existing market structure. The question is, will those disruptive effects be net negative or positive? And how will the gains and losses be distributed between foreign and domestic capital, and other societal groups such as labor and the communities in which the firms operate? Scholars of international business have tended to address these distributional questions through analysis of structural dynamics. MNCs tend to operate in oligopolistic industries, where a few firms produce the majority of output and capture most of the market (Caves, Reference Caves1996). Their deep pockets and superior access to technology allow them to overcome foreign market entry barriers and the “liability of foreignness” or disadvantages that arise from their unfamiliarity with the cultural, political, and economic features of the local environment as well as their outsider status (Zaheer, Reference Zaheer1995). However, once established, MNCs’ firm-specific resources and capabilities are translated into competitive advantages that threaten to reduce domestic incumbents’ income and market share, increase competition in labor and product markets, and pressure domestic incumbents to exit (Barney, Reference Barney1991; Caves, Reference Caves1996).Footnote 11

Once again, this raises the issue of power relations between foreign and domestic firms. Yet the role of geopolitics, states, and economic nationalism is strikingly absent in this rational characterization of the behavior of multinational capital, a point to which this Element will return. Instead, dominant analytic approaches for determining domestic firms’ policy preferences in the rational-materialist tradition have largely relied on deduction from theoretical expectations of changes in firm income and profits arising from the implementation of alternative policy options. The main divide, broadly applied in the politics of international economic relations, is between factor-and sector-based approaches in neoclassic trade theory. Factor-based approaches rely on the assumptions of the Stolper-Samuelson (Reference Stolper and Samuelson1941) theorem, which suggests that when factors of production can move freely between sectors, policy shifts from protection to liberalization will increase the income of owners of factors that are relatively abundant in the economy (i.e. those in which the economy is well endowed) and lower the income of owners of the relative scarce factors (i.e. those in which the economy is poorly endowed). In developing country contexts like postwar India and Brazil, owners and intensive users of scarce factors (usually capital) will be expected to support protection while owners and intensive users of abundant factors (usually labor) will be expected to support liberalization. Policy conflicts are expected to emerge from differences in preferences between broad class coalitions, which in turn are based on a given country’s factor endowments (cf. Rogowski, Reference Rogowski1989; Scheve and Slaughter, 1998).

By contrast, sector-based approaches rely on the Ricardo-Viner model. It assumes that at least one factor is fixed such that factors associated with sectors facing foreign competition lose from liberalization. Following this model, and to the extent they are immobile, both capital and labor in import-substituting manufacturing sectors will be expected to oppose liberalization. Thus, as an example, capital and labor in the protected postwar Indian or Brazilian automobile industries should both oppose FDI reforms. Political conflicts are expected to occur across sectors with cross-class coalitions of capital, labor, and landowners who stand to benefit from liberalization on one side, pitted against cross-class coalitions that stand to lose on the other. The key is factor specificity, that is, the extent to which factors are closely tied to their sectors (cf. Milner, Reference Milner1988).

In summary, both theories predict – albeit via different mechanisms – that industrial capital in developing countries such as India will resist liberalization and lobby for protection. How then can we explain similarly situated Indian and Brazilian government and firm actors’ contrasting preferences for FDI in the immediate postwar period, when Indian automobile firms sought limitations on foreign capital participation in India while their Brazilian counterparts were far more welcoming to multinationals? Not only do both these structural-material frameworks fail to explain this sort of cross-national variation, these static approaches face challenges in explaining preference change, such as many Indian manufacturers’ growing preferences for FDI reforms in the post-1991 liberalization era, which contrasted with greater resistance to foreign capital entry during the import substitution era. As Mark Blyth (Reference Blyth2003) pithily noted, “structures do not come with an instruction sheet.”

Open-economy Politics

The exclusive focus on material sources of preferences in the literature merits further attention. In many respects, Peter Gourevitch’s (Reference Gourevitch1986) claim that “what people want depends on where they sit” might be seen as the early forerunner of material interest-based approaches in comparative and international political economy (Blyth, Reference Blyth, Lichbach and Zuckerman2009). However, the analytic move to combine political analysis with economic theory as described in the previous section aimed to provide parsimony and predictive power, albeit at the cost of Gourevitch’s richness (Blyth, Reference Blyth, Lichbach and Zuckerman2009). David Lake argues that deducing interests is the essential innovation of “open economy politics,” which “begins with sets of individuals – firms, sectors, factors of production – that can reasonably be assumed to share (nearly) identical interests” and derives preferences over economic policy from each actor’s structural location (Lake, Reference Lake2009: 50). Indian firms’ FDI policy preferences would thus be deduced from their structural position relative to multinational competitors in the global economy. These assumptions are vigorously defended as the standard for comparative and international political economy (Frieden and Martin, Reference Frieden and Martin2002; Lake, Reference Lake2009).

The conundrum of economic nationalism lies at the core of these approaches. It led to the development of the open economy politics (OEP) approach in the 1970s, which sought to explain the significant variation in protectionism that was observed across countries and industries, and over time. It was rooted in dissatisfaction with earlier political economic analyses that were seen as unsystematic and lacking rigor. By contrast, the adoption of deductive economic approaches such as those based on “rigorous” Ricardo-Viner and Stolper-Samuelson trade theories produced testable hypotheses and generalizable results thus underpinning a revolution in approaches to determining economic interests, policy preferences, and political economic outcomes (cf. Alt and Gilligan, Reference Alt and Gilligan1994). Concrete materialist interests displaced what were seen to be fuzzy cultural and ideational objectives and motivations, particularly those characterized as economic nationalism.

While this analytic approach grew out of trade analyses such as Rogowski’s (Reference Rogowski1989) well-known study of the sources of cleavages in political coalitions, it has been widely applied as the standard approach to non-trade areas of international economic relations, including international financial and monetary policy (Frieden, Reference Eden1991, Reference Frieden1994, Reference Frieden2006), product markets (Keohane and Milner, Reference Keohane and Milner1996; Bates, Reference Bates1998), labor markets (Rodrik, 1997; Iverson, 2005), and foreign direct investment (Pinto, Reference Pinto2003). Theoretical and empirical developments in OEP later led scholars to incorporate the impact of domestic and international political institutions as mechanisms of preference aggregation and sites of bargaining among competing societal interests at the domestic and interstate levels (Lake and Powell, Reference Lake and Powell1999; Milner, Reference Milner1999; Frieden and Lake, Reference Frieden and Lake2005).Footnote 12

Once again, the enigma of economic nationalism served as a motivating force. Much of this research was conducted by economists and was driven by a normative question that puzzled many of its proponents who wondered, “Given that freer markets and economic liberalization is clearly good for countries, ‘Why don’t governments do what is obviously best for their societies?’” (Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2008). By contrast, political scientists saw “protection as the norm” and sought to explain why countries would liberalize at all: “Politically, protection seem[ed] eminently reasonable” (Milner, Reference Milner1999).

In economics, this question became a topic of interest for the voluminous public choice literature that applied neoclassical market analytic tools to non-market domains of social and political life. The mood of the time is best summarized by Gary Becker’s pronouncement that “the [neoclassical] economic approach is a comprehensive one that is applicable to all human behavior” (Becker, Reference Becker1976: 8). Economic policies were the outcome of the political influence of powerful rent-seeking interest groups rather than idiosyncratic nationalism (Buchanan and Tullock, Reference Buchanan and Tullock1962; Stigler, Reference Stigler1971; Buchanan, Tollison and Tullock, Reference Buchanan, Tollison and Tullock1980; Grossman and Helpman, Reference Grossman and Helpman1994).Footnote 13 Policy arenas characterized by diffuse costs and concentrated benefits such as trade and FDI were seen as particularly vulnerable to the rent-seeking activities of well-organized groups. Despite important criticisms, especially of the strict behavioral assumptions upon which it rested, the literature served to orient theorists to the distributional effects of economic policy and the implications for political action. We now turn to consider these three issues – behavioral assumptions, distribution considerations, and sociopolitical outcomes – in greater detail.

Preference Ambiguity

The core of the debate is about the nature and source of economic policy preferences. Structural deductive theories, either separately or in combination (e.g. Hiscox, Reference Hiscox2002), have done much to advance scholarly understanding of the sources of economic policy preferences in comparative and international political economy. Nevertheless, they have important limitations. Deduced preferences do not explain what in reality are far more ambiguous responses to liberalization (Helleiner, Reference Helleiner2002; Helleiner and Pickel, Reference Helleiner and Pickel2005). Economic actors reveal complex preferences that are a priori difficult to ascertain, even within a particular social class (e.g. capital or labor), sector (e.g. manufacturing or services), or industry (e.g. automobiles or pharmaceuticals). This has been demonstrated by empirical studies across a variety of country contexts (Schneider, Reference Schneider2004). Kingstone (Reference Kingstone1999) reveals how, contrary to expectations, Brazilian industrialists did not resist external liberalization in the late 1980s and 1990s. Segments of domestic capital that had earlier opposed liberalization changed positions and joined reformist politicians in a powerful coalition for free trade, despite decades of privileges under import substitution policies. Similarly, in Mexico, large domestic firms played a crucial role in supporting Mexico’s trade reforms in the late 1980s and early 1990s (Thacker, Reference Thacker2000). In both cases, entrenched domestic incumbents that had reaped significant gains from protection appeared to act against their structurally determined preferences, resulting in quite varied approaches to market liberalization.

Preference ambiguity is not limited to developing country contexts. Woll (Reference Woll2008) shows how major US and European telecommunications firms like AT&T, Deutsche Telekom, and France Telecom were uncertain of their policy positions over liberalization of the global telecommunications industry. She details how their preferences evolved over the course of the negotiations from resistance to active support. The same findings hold when examining firm preferences in other realms of business politics. Martin (Reference Martin1995, Reference Martin2006) reveals the striking indeterminacy of US firms’ preferences for healthcare and labor market policies in the 1990s and 2000s. She is joined by Swenson (Reference Swenson1991) and Mares (Reference Mares2003) in a now well-established critique of approaches that read business preferences off structural capital-labor cleavages, instead showing how capital has in many cases pushed for pro-labor policies.

This Element builds on these scholars’ work by pushing the critique of structural determinants of policy preferences one step further through the cases of Brazil and India. It shows how radically different preferences emerged from historically rooted variation in beliefs about the role of foreign versus domestic firms in the industrial development process and wider modernization project. These beliefs informed the development of distinct ideas linking FDI with industrial development outcomes. These economic ideas were underpinned by historical experiences that ascribed salient social meanings to the role of foreign capital in the pursuit of industrial modernity. Brazilian business and government actors welcomed multinational corporations as collaborative partners who could play a central role in capital accumulation and industrialization in the manufacturing sector. Their Indian counterparts also recognized that foreign firms were crucial sources of technology, but viewed them as potential neo-imperialist instruments, and hence were much more wary of engaging with multinationals.

Foreign capital was thus placed in contrasting categories in both countries. These policy positions were reversed when dealing with oil. The role of foreign capital was thus interpreted in different ways across industries in both countries. The upcoming sections provide empirical support for the view that economic actors’ policy preferences cannot be deduced based on assumptions of material interests and structural position. Preferences are shaped by economic ideas that are imbued with historically salient social and political meaning. In the Brazilian and Indian cases these arise from colonial experiences that shape nationalist beliefs. Economic interests and policy preferences are not automatically given; preferences are formed through historically embedded sociopolitical processes that shape the experiences and beliefs of economic and political actors.

The Substantive Content of Policy Preferences: Role of Economic Ideas and Economic Nationalist Beliefs

The previous section argued that ideas drawn from economic theory are essential constitutive elements of economic policy preferences. Economic ideas provide the causal connection between a given policy and its economic outcomes and distributional effects. Hall (Reference Hall, Katznelson and Weingast2005: 141) argues that these theories are “indispensable in the economic sphere since we do not see the economy with the naked eye but live in the imagined economies constructed by economic theory.” Preferences thus turn heavily on the cause-effect relationships that are posited in prevailing economic theories (ibid.). This is reflected in the twentieth-century historical movement between theoretical paradigms of Keynesianism and Monetarism in the advanced industrialized countries, as well as from import substituting industrialization to economic liberalization in the developing world. These epochal movements between techno-economic institutional arrangements reflected shifts in distinct belief-systems based on competing economic technologies. The rise and fall of Keynesianism in the United States and Western Europe was the outcome of changing policy preferences (Blyth, Reference Blyth2002). So too were European governments’ decisions to enter into monetary union (Hall, Reference Hall, Katznelson and Weingast2005). As was many developing countries’ adoption of trade and investment policy packages associated with neoliberal globalization and the Washington Consensus. Further, governments are not alone in being susceptible to the ideas that drive these types of macro-institutional shifts; they also occur at the firm level as studies by Fligstein (Reference Fligstein1990) and Dobbin and Zorn (Reference Dobbin and Zorn2005) on shifting logics of corporate governance showed, and to which the findings of this Element attest.

These theories are not simply technical artifacts, but rather function as mechanisms of distribution, power, and control. Just as the shift from Keynesianism to Monetarism is seen as having momentous distributional effects between capital and labor – by weakening labor union power, increasing inequality, and undermining the welfare state – so too have the predictions from economic theory about the effects of FDI policy provided the rationale for economic agents’ belief that a liberal FDI policy regime will be either good or bad for a given sector, industry, or firm. These theories and the policies they imply directly determine distributional outcomes between foreign and domestic firms in Brazil and India. Preference formation is an inherently contentious and political process: it is a high-stakes game. However, the central role of economic theory in preference formation introduces an element of indeterminacy as economic theory itself often provides ambiguous policy direction to economic agents, particularly under conditions of uncertainty. This provides opportunities for economic agents to persuade others to pursue the courses of action that they believe will best allow them to achieve their interests. It also provides an explanation for why we see radically different policy approaches that are nevertheless underpinned by economic nationalist beliefs, whether in the postwar period, as I will show through the cases of Brazil and India, or in the period of neoliberalism and globalization as Helleiner (Reference Helleiner2002), Pickel (2021), and others have argued.

The indeterminacy of economic theory is well recognized in empirical studies of policymaking. Hall (Reference Hall, Katznelson and Weingast2005) showed how after fifteen years of debate British officials were unsure of whether joining the European Monetary Union would advance the nation’s interests. Even after inception the effects remained unclear. Certainly, in the context of FDI theory the relationship between FDI liberalization and economic outcomes for domestic firms has long been ambiguous. FDI liberalization may either lead to displacement of local companies as more efficient MNCs enter the market, or it may lead to increases in domestic firm productivity and market competitiveness through technological spillovers. These are the competing theories that shape FDI policy preferences and contestation between actors in the policy arena.

As previously discussed, arguments against FDI liberalization rest on the expected distributional effects of FDI reforms, where efficient MNCs threaten to outcompete and ultimately displace their inefficient domestic counterparts. By contrast, the main argument in favor of liberalizing FDI in a developing country context sees MNCs’ superior technology as a potential advantage, suggesting that FDI facilitates productivity spillovers that domestic firms can capture. A brief review of the literature serves to highlight this issue. In early scholarship on FDI, Caves (Reference Caves1974) used sector-specific data to find positive productivity spillovers from MNCs to local firms. FDI was held to provide benefits through three distinct mechanisms: allocative efficiency through pro-competitive effects, technical efficiency through demonstration effects, and technology transfer by providing access to know-how on favorable terms (Caves, Reference Caves1974). These and similar pro-FDI mechanisms were heavily promoted by powerful global actors such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank as they pushed developing countries to adopt neoliberal economic reforms, including deregulated FDI regimes, from the 1980s onward.

These policies were promoted despite increasingly ambiguous evidence of the beneficial effects of FDI, even within mainstream economics. Aitken and Harrison (1999) critique studies using sectoral data by pointing to an identification problem: Studies focus on industries where domestic total factor productivity (TFP) is already high. They use Venezuelan plant-level panel data and a fixed effects model to show that FDI does not generate significant intra-industry productivity spillovers. Other studies have increasingly found negative effects across factor and product markets. Aitken, Harrison, and Lipsey (Reference Aitken, Harrison and Lipsey1996) found that domestic TFP was negatively impacted as foreign competitors bid up wages and hired away talented workers. Markussen and Venables (1999) found that local firm sales were hurt by MNC entry leading to productivity decreases from the effects of adjustment costs on input usage or the ability to capture scale economies. Later studies only increased the ambiguity by identifying contingent effects: Javorcik (Reference Javorcik2004) found vertical spillovers arising from backward linkages from MNC customers to their local suppliers, but no intra-industry effects through horizontal spillovers or forward linkages. Buckley et al. (Reference Buckley, Clegg and Wang2007) illustrated a potential temporal effect through an inverted U-shaped relationship, with TFP rising with small levels of MNC entry and then falling as more MNCs enter the market.Footnote 14 Finally, in addition to these findings by mainstream international economists that cast doubt on the benefits of FDI, heterodox development economists like Alice Amsden (Reference Amsden2001, Reference Amsden, Dosi, Cimoli and Stiglitz2009) strenuously argued that multinational corporations pose a significant threat to domestic firms, crowding them out of the types of underdeveloped or “imperfect” markets that characterized developing economies.

This theoretical and empirical ambiguity in the scholarly literature raised serious questions about the actual economic effects of foreign investment, yet this uncertainty and ambiguity hardly deters economic agents from drawing on these arguments in their efforts to convince others of their preferred FDI strategy. On the contrary, these opposing economic arguments constitute valuable resources that are used by competing actors in their efforts to shape FDI rules to their liking, as the upcoming discussions of the Brazilian and Indian industry cases show. Ambiguity creates a space for politics that would likely be foreclosed if causal economic relationships were unquestioned. This policy contest to influence preferences and outcomes takes place in a variety of public and private spaces. The domain of public discourse through the media has been an especially brutal battleground alongside closed-door discussions between individual firms, industry associations, lobbyists, and different representatives of the government. Domestic firms that believe they can benefit from technology transfer from MNCs push for joint venture rules that mandate local-foreign firm partnerships through joint ventures or local content requirements that stipulate the use of domestic suppliers. Other domestic firms that are skeptical of MNCs’ positive impact on local players utilize theoretical arguments of market stealing effects to make their case. Foreign firms are also important players in this arena. They deploy theories purporting that FDI provides broad efficiency gains at the industry level and has implications for employment and economic growth that shape key actors’ preferences and wider public opinion. In the absence of a scholarly and policy consensus, the legitimacy of these competing theoretical arguments relies on factors that are beyond the merits of the causal ideas themselves, including the social, economic, and political resources – which is to say the power – of economic agents striving to shape the field of FDI policy (Fligstein, Reference Fligstein2008).Footnote 15 It also heavily relies on the extent to which competing actors are able to imbue these causal ideas with historically salient social meaning, such as compelling nationalist narratives, symbols, and tropes (Jackson, 2025).

Nationalist Narratives: Historical Salience and Social Meaning

Salient and socially meaningful symbols and narratives play a key role in shaping economic actors’ policy preferences. Narratives are socially embedded cultural devices. They allow economic actors to make sense of the economic world by providing intersubjectively held interpretations of important events. These interpretations imbue the abstract causal relationships provided by economic theory with social meaning. Economic development and modernization can be viewed as a series of “societal projects” (Dobbin, Reference Dobbin and Dobbin2004) that are based on a specific set of ideas – economic growth, industrialization, democracy – which are operationalized in the policy realm by following the prescriptions of prevailing social and economic theories that spell out the means to achieve them. In this respect “policy is only partly driven by material forces … Its route also depends on sequence of events a nation faces and grand narratives devised to explain what it should do in the face of such events” (Hall, Reference Hall, Katznelson and Weingast2005: 137). History and the interpretation and social meaning of past events are thus central in understanding the policy preferences that actors hold.

Economic theory, nationalist narratives, and cultural symbols thus play mutually reinforcing roles in policymaking processes. Actors try to comprehend otherwise technical and ethereal economic policies by linking them to a larger sense of nation and history (Abdelal, Reference Abdelal2001). As I have argued elsewhere, how else to make sense of the murky modalities of technological learning and the confusing prescriptions of contradictory economic theories than to connect it with stories of travail and triumph of entrepreneurial domestic firms? (Jackson, 2025: 25) Tata Steel’s late nineteenth-century struggle to establish a domestic steel industry against strident foreign opposition before eventually prevailing against both the colonial government and British competitors and rescuing India’s nascent railroad construction projects during the steel shortages of the First World War provides an excellent example. A century later at the beginning of the new millennium, popular conceptions of “new economy” IT giant Infosys redefined how India was viewed in the global economy and, even more importantly, how Indian firms were viewed at home (ibid.).

Analyzing how narratives are interpreted and reinterpreted over time provides insights to the contested nature of history. It allows for “discerning how one account comes to be accepted as ‘what really happened’ while other plausible stories are rejected” and provides a perspective from the worldview of actors of why, in a given context, certain actions are taken while others are either rejected or not considered at all (Ross, Reference Ross, Lichbach and Zuckerman2009: 149). Narratives are infused with symbols and metaphors that capture the imagination, galvanize potentially fractious groups, and motivate action; they imbue actors with “social purpose” (Abdelal, Reference Abdelal2001). And just as economic theories are not mere technical artifacts, symbols, and narratives are not just stories. They are resources to be utilized by economic agents seeking to convey a particular understanding of the world and courses of actions that should be pursued.

We now turn to deeper consideration of the role of economic nationalism in industrial policy and economic development.

3 Reconsidering the Role of Economic Nationalism in Development

“ … [we are witnessing] the re-emergence of a spectre from the darkest period of modern history … Economic nationalism … . If it is not buried again forthwith, the consequences will be dire.”

Theories of economic nationalism are a mainstay of comparative and international political economy, historical sociology, and international management (Hymer, 1960; Abdelal, Reference Abdelal2001; Gilpin, Reference Gilpin2001; Helleiner, Reference Helleiner2002; Helleiner and Pickel, Reference Helleiner and Pickel2005; Bonikowski, Reference Bonikowski2016). However, while economic nationalism is regularly deployed to explain external economic policies by academics, policy analysts, and the media, with few exceptions it is often ambiguously conceptualized and in the worst instances, such as The Economist quote earlier, merely serves as shorthand for protectionism. Even among leading scholars in the field, conceptions of economic nationalism have teetered between fuzzy perspectives of economic policymaking as emotional and irrational, to perspectives of economic nationalism as reflecting the rational pursuit of material interests. Economic historian Charles Kindleberger provided an excellent articulation of the latter view in describing policymakers as rationally responding to opposition to FDI arising from the “peasant, the populist, the mercantilist, or the nationalist which each of us harbors in his breast” by instituting protectionist economic policies that benefit domestic interests.Footnote 17 By contrast, economist Harry Johnson, a leading contributor to the growing field of international economics in the postwar period, “famously [and dismissively] ascribed many countries’ protectionism to a ‘taste for nationalism,’ [and] a willingness to ‘direct economic policy toward the production of psychic income in the form of nationalistic satisfaction, at the expense of material income’.”Footnote 18

These contradictory perspectives on economic nationalism are clearly unsatisfactory. While the conceptualization of economic nationalism has been sharpened over time, economic nationalism is still often posited as either romantically emotional or ideological, as with the Johnson quote, or are materialistic and hyperrational, as with Kindleberger’s contribution. As noted in the previous section, competing theories of economic nationalism have benefited from developments in rational-deductive political economy as well as from the interpretive “cultural turn,” both of which have brought analytic rigor to these earlier formulations. Nevertheless, contemporary approaches still tend to offer relatively simple and unidimensional conceptions of nationalism that fail to explain diverse policy responses in the face of common external economic phenomena. This constitutes a major challenge across a range of disciplines, as current approaches may generate misleading explanations of economic policy processes and inaccurate predictions about ensuing regulatory and market outcomes. This Element offers an alternative approach that historically grounds economic nationalism in the sociopolitical processes through which distinct varieties of anti-colonial nationalisms are formed, contested, and institutionalized, as well as in the economic ideas that offer a sense of causality and rationality. Together, these sociopolitical processes and economic ideas co-constitute economic nationalism and give it rigor and meaning.

Agency vs Modularity in the Global Rise of Nationalisms

While economic nationalism is regularly used in scholarly and policy discourse, surprisingly, it is rarely well defined. Remarkably, this definitional lacuna also holds for scholarship on the broader concept of nationalism. It is thus important to establish clear definitions of both of these closely related concepts. Mylonas and Tudor (Reference Mylonas and Tudor2023: 4) argue that, despite the dramatic resurgence of nationalism in the second decade of the twenty-first century, “scholars of nationalism are surprisingly inconsistent in their definitional and conceptual approaches,” utilizing a wide array of definitions, but often without directly engaging with each other. They offer a path forward by describing nationalism as having three core attributes: (1) an intersubjective recognition and celebration of an “imagined community” as a locus of loyalty and solidarity; (2) a drive for sovereign self-rule over a distinct territory that is pursued by a significant segment of a group’s elite; and (3) a repertoire of symbols, practices and narratives that embody the nation (Mylonas and Tudor, Reference Mylonas and Tudor2023: 5). I build on this framing that centers Benedict Anderson’s (Reference Anderson2006) notion of nation as “imagined community,” the importance of territorial sovereignty and elite control (which is especially important in the case of oil in Brazil), and the centrality of cultural symbols and narratives (particularly striking in the case of manufacturing in India).

In order to develop a working definition of economic nationalism, I couple this attention to imagined community, territoriality, symbolism, and narratives with what Rawi Abdelal describes as the intersubjective “content” of nationalism. Abdelal (Reference Abdelal2001: 1) defines nationalism as a “proposal of the content of national identity” that reflects society’s collective – though often contested – interpretations of the social meaning of the nation, the path it should follow, and the policies that societal actors believe will achieve those goals. I build on Abdelal and Mylonas and Tudor by defining economic nationalism as an elite project of sovereign control of physical territory, society, and economy through a constructed notion of community animated by a set of historically rooted symbols, narratives, and practices. To paraphrase Abdelal, economic nationalism is an attempt to link the idea of a nation to specific economic goals. These goals are defined in relation to both: retrospectively, to a sense of national history, and prospectively, to a sense of national purpose. This framework for understanding the relationship between policy preferences and economic nationalism provides significant analytic room for agency and contestation. While the social meaning of nationalism is intersubjectively held, the “content” of every national “proposal” is hotly debated and contested by groups and individuals across a given society. There are always competing nationalist projects with political battles determining which will prevail.

Finally, nationalisms do not emerge within a vacuum; they arise in interaction with and often in opposition to other nationalisms in the international state system and the global political economy. Nationalisms are relational and are often imagined having an “other” both within and outside of the state (for example, in India, Hindu nationalists as distinct from secular nationalists often see both Indian Muslims as well as the “West” as others). It is variation in this “content” as deployed by competing nationalist actors that gives rise to contestation between competing national goals and identities in a given society as well as across countries. This variation in content and contestation ultimately produces differences in economic policies and market outcomes.

There is a tension between the unique cultural construct of the nation that nationalist actors must create to successfully oppose the imperialist “other,” and the homogenizing forces of the global political economy. Brazil and Indian nationalists were not alone in their efforts to imagine a unified nation in the late nineteenth century. After all, this was the period of the first globalization, a time when the Westphalian system of nation-states was coming into being. The global political environment was characterized by nationalist struggles to consolidate territories, peoples, and economies in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America and the Caribbean. This was also the moment when “late-developing” states such as the United States and Germany sought to establish domestic industrial capacity within the wider institutional context of globally dominant British manufacturing and a free trade regime enforced by the combined might of British capital, the British navy, and British theories of classical political economy.

These efforts by late-developing states provided institutional templates for the colonies that Anderson (Reference Anderson2006 [1983]) has referred to as “modular,” providing a valuable framework for the construction of nationalist proposals. Anderson showed that nationalist imaginaries cannot be analyzed in isolation; they are part of wider sociohistoric dynamics in both their material and cultural dimensions. Economic nationalisms are products of global economic and technological processes as well as the cultural meanings and practices that accompany them. Anderson identified the new discourse of nationalism and the mechanisms through which it was transplanted across space and time, allowing nascent conceptions of nationalism to spread through Asia, Europe, and Latin America in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. Brazil and India were no exceptions: the processes occurring within India and Brazil in the late nineteenth century cannot be divorced from political developments in other regions of the world. Indeed, anti-colonial nationalist figures were keen participants in global circuits in the early-mid-twentieth century from metropolitan locations such as London, Paris, New York, and Berlin to new convening spaces in the Global South such as Arusha and Bandung (cf. Getachew, Reference Getachew2019). Nevertheless, despite the availability of nationalist ideas in the global environment, the construction of Indian economic nationalism, for example, required strategic efforts by emergent nationalist actors to reformulate “modular” ideas for the Indian context. This is the very definition of agency – “the capacity to transpose and extend schemas to new contexts” – that Sewell (Reference Sewell1992: 19) argues is required to facilitate structural transformation.

Thus, despite its attractiveness, Goswami (Reference Goswami2002: 780) suggests that modular diffusion may be conceptually delinked from the material context of new socioeconomic relations of late nineteenth-century global capitalist production. While Anderson’s (Reference Anderson2006 [1983]) modular nationalism and theory of nations as imagined communities provide rich insights, they do so at the cost of privileging ‘subjective’ cultural accounts over ‘objective’ material explanations. Anderson’s (Reference Anderson2006 [1983]) emphasis on the subjective is strategic – aiming to correct what he perceived as overly positivistic understandings of the nation through a discursive approach that revealed the subjectivity of nationalism – but his modular approach may nevertheless universalize mimetic processes. This approach risks sacrificing the context-specificity arising from “[material] socio-historical processes and institutional constraints that attend the production and circulation of meaning” (Goswami Reference Goswami2002: 780). The material and cultural dimensions of sociohistorical processes require equal analytic weight.

While this Element challenges the structural-material assumptions that underpin dominant conceptions of economic interests and policy preferences, the framework that is developed avoids privileging culture over materiality by recognizing the duality of subjective-cultural and objective-material determinants of preferences in shaping the institutional foundations of nationalism in late colonial India and early independent Brazil. Sewell’s (Reference Sewell1992) theory of duality facilitates a conception of structure as simultaneously material and cultural. For example, it stresses the importance of agency in understanding how Indian actors both interpreted nationalist ideas that they were exposed to in their reading or travels to Europe and East Asia through their own sociohistorical lens and then reformulated these models to the Indian political-economic context, and how Brazilian elites similarly struggled to distinguish their identities from Europe. This agency-oriented approach to nationalism challenges not only Anderson’s modularity but also the world polity approach of Meyer et al. (Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez1997). The world polity perspective suggests that ideas diffuse via mimetic processes through elite networks and are adopted wholesale by recipients. The contrasting Brazilian and Indian cases provide a direct empirical challenge to this view (see also Go, 2021).

Indeed, Getachew (Reference Getachew2019) provides one of the most powerful articulations of this alternate perspective highlighting the agency of anti-colonial nationalists. She challenges the standard liberal account of decolonization that sees the transition from empire to independent nation and the concomitant expansion of international society to include new postcolonial states “as a seamless and inevitable development” (Getachew, Reference Getachew2019: 14). This conventional view of decolonization sees anticolonial nationalists utilizing the language of liberal self-determination associated with Woodrow Wilson and, like Meyer et al. (Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez1997) would hold, mimicking the existing institutional forms of the nation-state. Getachew argues that characterizing decolonization “as a process of [mimetic] diffusion, in which a gradual ‘Westernization’ of the world took place, blunts anticolonial nationalism’s radical challenge to the four-century-long project of European imperial expansion.” However, “Rather than a seamless and inevitable transition from empire to nation, anticolonial nationalists refigured decolonization as a radical rupture – one that required a wholesale transformation of the colonized and a reconstitution of the international order” (Getachew, Reference Getachew2019:16). Instead, anti-colonial economic nationalists such as W.E.B DuBois, Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyere, George Padmore, and Eric Williams sought to challenge the entrenched inequality of the international system through processes of “worldmaking.” Nkrumah articulated this inequality in stark neocolonial terms, highlighting the widely held concern that foreign interests sought to continue to exploit the labor force and natural resources of newly independent countries: “practically all our natural resources, not to mention trade, shipping, banking, building … have remained in the hands of foreigners seeking to enrich alien investors, and to hold back local economic initiative” (cited in Getachew, Reference Getachew2019). These new leaders sought to upend this unequal global economic structure by gaining sovereign control of their national economies.

Getachew (Reference Getachew2019) thus shows how, contrary to the view of economic nationalism as autarkic, anti-colonial nationalists in Africa and the Caribbean sought to reform, rather than reject, the unequal international system through processes of “worldmaking.” These included an array of institutional innovations such as the formation of regional economic federations in Africa and the Caribbean. Anti-colonial figures such as Michael Manley also participated in the development of broader formations of postcolonial solidarity such as the New International Economic Order (NIEO). These would serve as bulwarks against neo-imperialism, including forms of neo-imperialism carried out by new instruments of postwar empire: international institutions that facilitate unfettered capital flows as well as the organization that replaced the trading companies of the previous era by embodying private foreign capital in the newly decolonized world, the multinational corporation.

Advancing New Conceptions of Economic Nationalism: Content and Contestation

There has been a revival of literature on economic nationalism over the past two decades. These works have in common a rejection of simplistic views associated with earlier, often narrowly materialistic and economistic, literatures discussed in the previous section. This new scholarship began with an initial wave of work in international political economy that challenged the “end of history” notion that neoliberalism and globalization had rendered economic nationalism obsolete (Helleiner, Reference Helleiner2002; Helleiner and Pickel, Reference Helleiner and Pickel2005). Instead, these scholars showed how economic nationalism was not necessarily about protectionism, but in fact could be consistent with economic liberalization of the form that swept through the developing (and industrialized) world in the 1980s and 1990s. This was followed by a more recent round of scholarship that went further in highlighting, often in similarly counterintuitive and surprising ways, the historical importance and continued legacy of anti-colonial nationalisms of the 1930s–1970s. For example, Slobodian (Reference Slobodian2018) showed how the perceived threat of anti-colonial nationalism to the liberal international economic order prompted the genesis of neoliberal ideas in the 1930s by reactionary intellectuals associated with the Walter Lippman Colloquium and the Mont Pelerin Society who sought to “encase” global markets through international law. These important scholarly developments are further elaborated next.

The revival of the literature on economic nationalism in the early 2000s showed how economic nationalism remained a useful analytic concept in the context of globalization and neoliberalism, despite weaknesses in earlier formulations. Helleiner (Reference Helleiner2002) challenged the conventional wisdom that “economic nationalism is an outdated ideology in this age of globalization and economic liberalization … [an] assertion [that] usually assumes that the ideology of economic nationalism has a coherent nonliberal policy program which governments no longer endorse.” He also rejected the assumption that the 1980s–2000s were “uniformly liberal,” given the heterodox path of countries like China (cf. Weber, Reference Weber2021). Helleiner did so by making two key claims about the nature of economic nationalism in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. First, he argued that economic nationalism is not simply a form of protectionism or strand of statist realism, but is best defined by its nationalist content, a position that resonates with Abdelal (Reference Abdelal2001). Second, Helleiner showed how contemporary economic nationalism can be compatible with a range of policy approaches and projects, including liberal ones. Economic nationalism thus remains both powerful as an ideology and ambiguous with respect to policy goals and cultural content.Footnote 19

Helleiner further posited economic nationalism as a rival to economic liberalism and neoliberalism in the wake of the late twentieth-century collapse of communism and the Marxist political project. In the nineteenth century, economic liberalism was a powerful force with Marxism and economic nationalism as its main rivals. Yet, as illustrated earlier by the Johnson and Kindleberger quotes, economic nationalism became the subject of analytic confusion in much of the twentieth century, ranging from characterizations of irrational protectionism to conflations of statism with nationalism. The latter view sought to locate “state-centric realism” in a tradition dating back to seventeenth- to eighteenth-century mercantilism (Gilpin, Reference Gilpin1987). Yet others challenged this perspective, arguing that statism is about state interests as separate from society, and social distributions of power, while economic nationalism is about the role of national identities and economic ideas inspired by nationalist beliefs in shaping economic policy (Abdelal, Reference Abdelal2001). These beliefs should be clearly defined before examining “foreign economic policy preference theoretically and empirically” (Shulman, Reference Shulman2000).

Recent literature has sharpened the economic nationalism analytic by showing how traditional conceptions ignore nationalist content. Helleiner (Reference Helleiner2002) argues that much of the problem can be traced back to (mis)readings of the seminal work of Friedrich List. List (Reference List1841 [1904]) was best known for his arguments in favor of infant industry protection. However, what was less well-known was that List himself did not define economic nationalism in policy terms but rather in terms of the “nationalist theoretical content of his ideas” (Helleiner, Reference Helleiner2002). List stressed nationalism as key to his arguments in National System of Political Economy and was critical of the “dead materialism” of classical (liberal) political economists in their failure to take nationalism seriously, instead of focusing on either individuals or humanity as a whole.

The goal of this work was to show that, contra the idea that economic nationalism was an outdated ideology in the context of the collapse of communism and the rise (and seemingly inevitable domination) of globalization and economic liberalization, economic nationalism remained a powerful force in shaping economic policy, albeit often in radically different directions. Economic nationalism does not necessarily represent illiberal policies that fewer governments appeared to endorse in the era of globalization and liberalization. Instead, some contemporary strands of economic nationalism may run counter to economic liberalization, such as what Helleiner refers to in recently published work as “neo-mercantilist economic nationalism” (Helleiner, Reference Helleiner2021) while others may (seemingly paradoxically) not.

Anti-Colonial Economic Nationalism and the Roots of Neoliberalism

This new strand of critical literature on economic nationalism thus gained traction as a response to neoliberalism and globalization. Indeed, the relationship between economic nationalism and neoliberalism has an important genealogy. This is important to present. First, to understand the interrelated set of political and ideational developments that led to the rise of different economic nationalisms in the mid-century. Second, to make sense of the ways in which those economic nationalisms shaped the later rise of neoliberalism in the late twentieth century (and the return of economic nationalism in the twenty-first). In Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism, Quinn Slobodian (Reference Slobodian2018) shows how anti-colonial economic nationalism lies at the root of neoliberalism itself. Slobodian argues that it was the fear of rising economic nationalism that served as the central motivating force for early neoliberals such as Freidrich von Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, Wilheim Röpke, and other members of the Walter Lippman Colloquium and the Mont Pelerin Society. Their ideas were explicitly developed in reaction to the perceived threat of rising economic nationalism, impending democracy, and statist economic planning in Eastern Europe and the decolonizing world. Further, and paradoxically, they sought to constrain demands for economic and political sovereignty in colonized spaces by privileging the sovereignty of multinational firms and private capital flows. Their proposal was to “encase” the global economy through an international legal architecture that would supersede the dangerous inclinations of soon-to-be independent states that were challenging forms of neocolonialism that Getachew (Reference Getachew2019) and others discuss.

Meeting and writing in Europe in the midst of rising fascism in the 1930s, these architects of neoliberalism believed that “The greatest danger [facing the world] is the new business cycle policy: the policy of economic autonomy, the policy of economic nationalism, combined with the planned economy and autarchy” (Slobodian, Reference Slobodian2018: 21–22). A key element of their concerns lay with the new techniques of economic governance that were rising to the fore during this period, not least Keynesian macroeconomic management as well as New Deal-style industrial, infrastructural, and social welfare policies. These technocratic tools of economic planning offered new ways of “seeing” the economy and thus rendering economy and society manipulable in ways that could conform to the needs and demands of anti-colonial actors (Scott, Reference Scott1998; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2002). Hayek and others feared that “Seeing economics through statistics and cycles had fostered fantasies of management at the scale of the nation that threatened to pave the way to global disorder” (Slobodian, Reference Slobodian2018: 89). The underlying issues in intellectual debates such as the socialist calculation controversy, as well as much of Hayek’s critiques of “the impossibility of planning,” were directed toward averting what they saw as an impending disaster of economic planning (Hayek, Reference Hayek1937, Reference Hayek1945). The market was seen as a superior means of coordinating economic activity. The key innovation that Hayek and others proposed was to use the supranational legal system to constrain the scope of economic management by sovereign states, thus enabling capital to move freely but also limiting the possibilities for more equitable and democratically governed national and global systems (Slobodian, Reference Slobodian2018).