1 Introduction: Why Corporate Adaptation Matters

Heat waves, wildfires, water scarcity, and extreme rainfall illustrate the wide-ranging and often devastating impacts of climate change on both human societies and ecosystems (Begum et al. Reference Begum, Lempert, Ali, Benjaminsen, Pörtner, Roberts and Tignor2022: 144). Adapting to these risks is increasingly recognized as one of the most pressing problems of our time. According to the World Economic Forum’s 2022 annual survey of business and government leaders, climate action failure is the greatest anticipated threat companies face in the coming decade (World Economic Forum 2022). Companies and policymakers alike tend to frame climate adaptation narrowly as a physical risk to individual firms that could reduce productivity and disrupt supply chains. As a result companies typically address adaptation as an internal matter of business resilience, rather than as a societal risk (TCFD 2017). In contrast, the failure of companies to decarbonize at the scale and speed required to avoid socio-environmental harm has been framed as a critical societal concern in both scholarly and policymaking debates.

In this Element, we challenge the conventional view that corporate adaptation is solely, or primarily, a matter of business resilience, as corporate adaptation (or lack thereof) has far-reaching consequences for nature and society. Failure by companies to effectively adapt to climate change can have catastrophic socio-environmental consequences. Consider the example of the Arctic oil spill caused by the Russian company Nornickel in 2020 – recognized as the worst Arctic oil spill in history (The Moscow Times 2020). The company had not implemented any adaptation measures despite well-documented climate risks associated with melting permafrost. In the words of a Greenpeace representative working in the Arctic region, Nornickel’s responsibility for its impacts on society and the environment are clear: “It is a powerful company […] We have known about the melting permafrost for at least 10 years. There should be monitoring systems, there should be special constructions that takes climate risks into consideration in the work it carries out in areas like this” (Interview 33).

This Element defines corporate adaptation as “the process of adjustment by companies to actual or expected climate change and their associated effects through changes in business strategies, operations, practices, and/or investment decisions” (cf. IPCC Reference Pörtner, Roberts and Tignor2022: 5). Companies have often relied on “technical fixes,” such as air-condition installations, back-up power installations, early warning systems, and water infrastructure to adapt to climate change (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Turner, Gladstone and Hole2019; cf. Nightingale et al. Reference Nightingale, Eriksen, Taylor and Forsyth2020). While these may appear to be simple technological adjustment aimed at climate-proofing facilities, they are often highly complex and may carry unforeseen societal consequences. Even when companies engage in climate adaptation, their actions can fall short of addressing the full magnitude of these risks and may not reflect or even conflict with societal priorities and needs (Grabs et al. Reference Grabs2026).

For example, wine producers have started relocating vineyards to higher elevations to maintain their production, which in turn has reduced freshwater availability (Hannah et al. Reference Hannah, Roehrdanz, Ikegami and Hijmans2013). In Brazil, large-scale agricultural producers have implemented irrigation schemes to cope with climate-induced water stress that have led to conflicts with local communities over water access and food security (Gustafsson et al. Reference Gustafsson, Schilling-Vacaflor and Pahl-Wostl2024). In Chile, mining companies and local communities have suffered from unprecedented megadroughts, leading companies to invest billions of dollars in desalination plants using seawater. While these plants have helped reduce hydrological insecurity and mitigate social conflicts at mining sites, they have also created new environmental problems and social unrest in coastal areas (Odell Reference Odell2021). These examples underscore how corporate adaptation (or the absence thereof) can exacerbate vulnerabilities and produce socio-environmental harms.

This Element asks how companies address the societal risks associated with their business activities in a context of climate change and what motivates them to do so. We develop a theoretical framework that, firstly, conceptualizes responsible business conduct (RBC) in the context of adaptation and, secondly, identifies central regulatory and political factors that shape RBC in adaptation. We explore the framework in the mining sector, which is especially vulnerable to climate impacts, and where RBC is crucial for preventing and mitigating the negative socio-environmental consequences of multinational corporate activity.

1.1 A Framework for Analyzing Corporate Responsibility in Adaptation

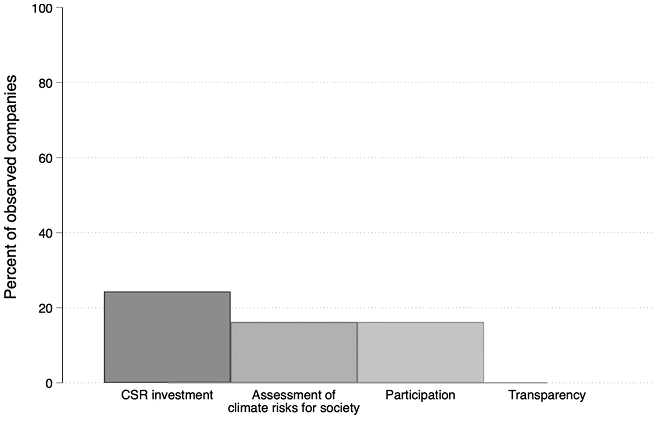

Our argument begins with the premise that companies can reduce climate-related harms associated with their business activities by integrating principles of RBC. In line with the OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct (OECD 2023), we refer to RBC as the behavior of businesses to avoid and address adverse impacts of their operations, while contributing to sustainable development in the countries where they operate. In this Element, we focus on four RBC principles central to climate adaptation: assessments of climate risks to society, stakeholder participation, transparency, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) investments in public adaptation goods. In doing so, we build and advance on insights from CSR, Business and Human Rights, and climate adaptation governance scholarship.

Despite growing attention to RBC in relation to environmental matters in general, climate adaptation continues to be only marginally addressed in emerging voluntary and mandatory frameworks. For instance, the voluntary OECD guidelines (2023: 37) stipulate that “enterprises should avoid activities, which undermine climate adaptation for, and resilience of, communities, workers and ecosystems,” leaving it unclear what this means in practice. Recent Human Rights and Environmental Due Diligence (HREDD) legislations, such as the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) and the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (LkSG) law, make RBC obligations legally binding. However, these legislations do not cover climate adaptation, meaning this conduct is currently not mandated by law.

Further, scholars have not yet systematically examined RBC in the area of adaptation. We suspect that there are two reasons for this. First, there is a lack of a common understanding of what adaptation means for corporations (Averchenkova et al. Reference Averchenkova, Crick, Kocornik‐Mina and Leck2016), and the concept is often used to refer to a variety of measures to address climate-related risks. Second, we argue that, compared to other RBC issues, corporate responsibilities vis-á-vis society are particularly ambiguous when it comes to adaptation. Climate-related risks can intersect with and exacerbate the impacts of business activities (Odell et al. Reference Odell, Bebbington and Frey2018). In such situations of “double exposure” to both climate impacts and economic activities, the potential socio-environmental consequences are not only likely to be particularly severe (Leichenko and O’Brien Reference Leichenko and O’Brien2008), but it is also more difficult to define the boundaries of corporate responsibilities in addressing these intersecting impacts. As climate-related impacts become more frequent and severe, we argue that companies must be better prepared and held accountable for how they respond to these intersecting impacts.

This Element seeks to remedy this shortcoming in the existing literature. The remainder of this section lays out the argument and introduces the research design. In the following two subsections, we briefly summarize our theoretical framework, which will be discussed in greater detail in Section 2.

Conceptualizing Corporate Responsibility in the Context of Climate Adaptation

This Element identifies central procedural and distributive RBC principles in the context of adaptation. These principles can help to prevent, or at least mitigate, the adverse effects of business activities amid climate change. Clarifying these responsibilities is important, as it facilitates more transparent and inclusive corporate responses to climate risks and supports the development of robust public policies and accountability mechanisms that align corporate adaptation strategies with societal needs. We begin by discussing the three procedural principles, followed by the distributive principle.

Assessments of climate risks to society enable companies to identify, prevent, and develop measures to address potential climate-related harms associated with their business activities before they occur, rather than merely reacting after the damage has already been done. Such climate risk assessments for society refer to an adequate evaluation of the societal risks associated with companies’ activities in a context of climate change, which may lead to restrictions of business activities. While many companies already assess their own exposure to climate risks, RBC requires a shift in focus toward the socio-environmental risks stemming from their business activities and adaptation strategies. Companies can achieve this by integrating climate adaptation into existing risk management processes, such as Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) and HREDD. More generally, human rights and environmental risk assessments are a core component of soft and hard law frameworks on RBC, such as the United Nations Guidelines for Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) (OHCHR 2011), the OECD Guidelines (2023), as well as binding laws building on these frameworks.

Through meaningful stakeholder participation, affected groups can influence how their perspectives and adaptation needs are integrated into corporate adaptation responses. By participation we mean the engagement of relevant, affected stakeholders at various stages of adaptation interventions (Eriksen et al. Reference Eriksen, Schipper, Scoville-Simonds and Vincent2021), including the assessments of climate risks, the planning of responses, and the implementation of adaptation interventions. In the context of the extractive industries, companies can, for example, integrate climate adaptation into EIAs and participatory water monitoring, thereby leveraging their existing institutionalized processes for stakeholder involvement. Stakeholder involvement throughout the process of assessing and addressing environmental and human rights risks is a cornerstone of the soft law frameworks of RBC, such as the UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines.

Transparency is important, as it can empower affected groups and governmental agencies to critically evaluate the risks associated with business activities in a context of climate change. This is particularly important in high-risk situations, where such activities may expose surrounding communities and environments to severe risks. We define transparency as companies’ obligation to inform affected groups and governmental agencies about their exposure to climate risks and the adaptive measures they have taken to address them (cf. OECD 2023). Along with risk assessment and stakeholder participation, transparency about risks associated with business activities and how companies monitor and respond to them is another core component of the soft law frameworks of RBC.

Finally, CSR investments can enable companies to move beyond a “do no harm” approach and make positive contributions to adaptation in the countries where they operate. This principle falls into the category of resource distribution, rather than the procedurally oriented principles outlined in HREDD frameworks. CSR investments typically involve the provision of public adaptation goods such as early warning systems, capacity building, and water infrastructure. When channeled through partnerships with public authorities and civil society organizations (CSOs), CSR can help build institutional capacity and support the implementation of adaptation plans (cf. UNEP 2021). However, companies often use CSR investments as strategic tools to legitimize their business activities and buy off opponents. In such cases, CSR can lead to the fragmentation of CSOs and the closure of public debates on climate-related risks and adaptation solutions that companies perceive as threatening to their interests (cf. Amengual Reference Amengual2018; Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson2018).

In sum, if meaningfully integrated into corporate adaptation responses, these four RBC principles promise preventing, or at least mitigating, the adverse impacts of corporate adaptation, and clarifying where restrictions of business activities are needed. As we elaborate in Section 2, our framework leaves out RBC principles in international frameworks, such as corporate governance and access to remedy, which are important in general but which is beyond the scope of our inquiry. Instead, we focus on those principles that are particularly relevant for preventing harm and developing regulatory policies addressing the intersecting impacts of climate change and business activities. Companies are unlikely to integrate these principles and change their behavior unless there are strong external incentives and/or regulatory pressures in place.

Regulatory and Political Factors Shaping Responsible Business Conduct in Adaptation

The second part of our theoretical framework explains how regulatory and political factors shape RBC in adaptation. We privilege three factors: public governance, civil society advocacy, and participation in voluntary adaptation initiatives. The private governance literature has highlighted that these factors matter for companies’ more general sustainability practices (Bartley Reference Bartley2018b; Lambin and Thorlakson Reference Lambin and Thorlakson2018; Thorlakson et al. Reference Thorlakson, Hainmueller and Lambin2018a, Reference Thorlakson, De Zegher and Lambin2018b), but to date they have not been examined in relation to climate adaptation. We build on this debate by theorizing how these external factors, both individually and in combination, affect how companies incorporate RBC into their responses to climate risks.

Public governance can influence RBC through soft steering and legal requirements. We refer to public governance as any hard or soft regulatory activities aimed at fostering RBC. For example, governments can introduce legal requirements to assess and address climate risks in different types of sectoral policy instruments, such as EIAs and water licenses. In some cases, this may lead to restrictions for business activities linked to substantial socio-environmental risks (cf. Bartley Reference Bartley2018a; Odell et al. Reference Odell, Bebbington and Frey2018). Governments tend to be reluctant to enforce stringent regulatory controls on businesses and instead use partnerships, support, and soft steering to influence company behavior (cf. Abbott and Snidal Reference Abbott and Snidal2009; Eberlein Reference Eberlein2019). To effectively steer and regulate company behavior, public authorities require capacity and robust monitoring systems to be able to assess the impacts of business activities in the context of climate change (cf. Lambin and Thorlakson Reference Lambin and Thorlakson2018).

In the absence of robust governance frameworks, voluntary adaptation standards can contribute to diffusing norms and contribute to learning about RBC in adaptation (cf. Grabs Reference Grabs2020). Such standards include multistakeholder initiatives, certification schemes, and private standards that set requirements for RBC (cf. Marx et al. Reference Marx, Depoorter, Fernandez de Cordoba and Verma2024). Yet, a large body of research shows that these standards frequently lack stringency, are unevenly applied, and are poorly incorporated into firms’ management structures (Bartley Reference Bartley2018b; LeBaron et al. Reference LeBaron, Lister and Dauvergne2017). Unlike climate mitigation, adaptation is covered by relatively few voluntary standards, and it remains unclear to what extent and how effectively these existing standards require companies to incorporate RBC principles into their adaptation responses.

Civil society advocacy can influence RBC by pressuring companies to develop more transparent and inclusionary adaptation responses. We refer to civil society advocacy as a civil society-based form of regulation of companies (cf. Newell Reference Newell2008), in which different types of CSO actors rely on campaigns, partnerships, and public scrutiny to compel companies to address socio-environmental risks in their adaptation strategies. Civil society has played a key role in compelling companies to comply more meaningfully with human rights and environmental standards (Bartley Reference Bartley2018b; Thorlakson et al. Reference Thorlakson, Hainmueller and Lambin2018a). However, it has often proved challenging for civil society to gather solid evidence of corporate impacts in the area of adaptation (Gustafsson et al. Reference Gustafsson, Schilling-Vacaflor and Pahl-Wostl2024). Additionally, unlike the large-scale protests against fossil-fuel emissions, mobilization around climate adaptation remains relatively rare (de Moor Reference de Moor2022).

We do not claim that these are the only factors likely to influence RBC in adaptation. Existing corporate adaptation research has also highlighted the role of biophysical risk exposure (Averchenkova et al. Reference Averchenkova, Crick, Kocornik‐Mina and Leck2016; Mbanyele and Muchenje Reference Mbanyele and Muchenje2022) and firm characteristics (Klein et al. Reference 75Klein, Käyhkö, Räsänen and Groundstroem2022; Pinkse and Gasbarro Reference 78Pinkse and Gasbarro2019). In contrast, our theoretical framework is embedded in the private governance literature and privileges regulatory and political factors, which to date remain under-researched in the context of adaptation. Next, we lay out our research design to empirically examine our account.

1.2 Evidence from the Mining Sector

We examine our theoretical framework by using a new quantitative and qualitative dataset on corporate adaptation in the mining sector. This sector suits our inquiry for several reasons. First, the mining sector is extremely vulnerable to different types of environmental hazards and climate-related risks. Extreme weather events can cause floods and droughts that can damage mining infrastructure containing highly toxic waste and in turn lead to land and water contamination (Phillips Reference Phillips2016). Additionally, mining is one of the most water-intensive industries. Unless companies adequately adapt to climate risks like these by climate-proofing their infrastructure and reducing their water consumption, surrounding communities can be severely affected by water stress.

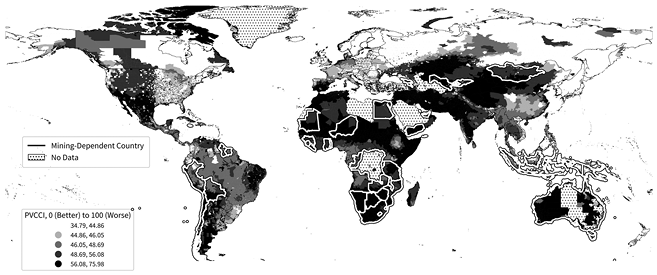

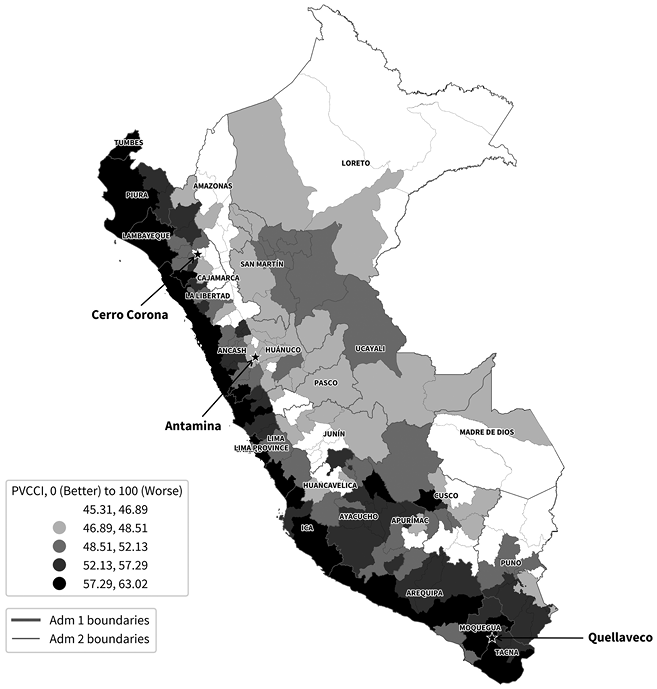

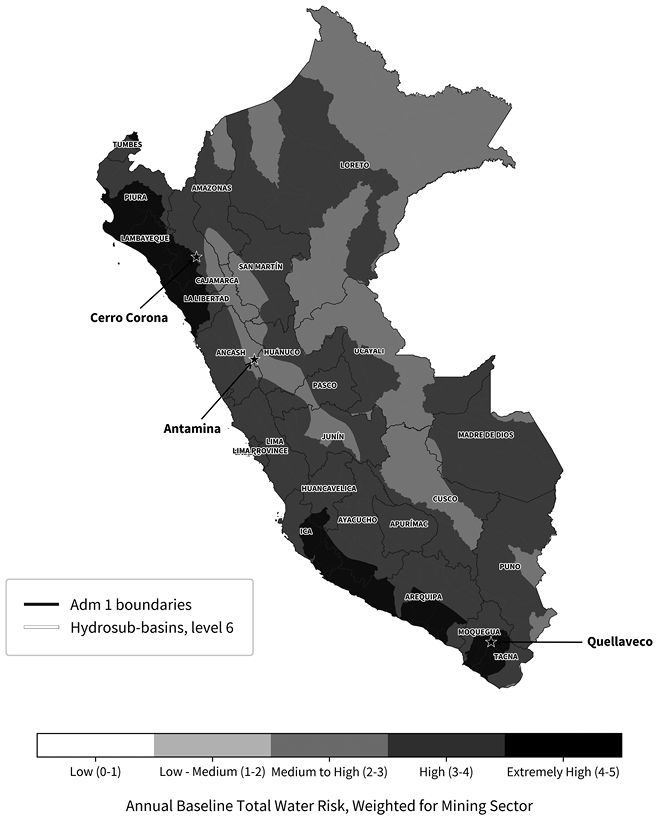

To illustrate the mining sector’s vulnerability to climate-related risks, we created data to visualize the context in which corporate adaptation in the mining sector unfolds. Figure 1 is a map showing both mining dependency and climate vulnerability. “Mining dependency” applies to countries where metals and minerals account for more than 20 percent of exports by value and mineral rents constitute more than 10 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). The data is drawn from the Mining Contribution Index compiled by the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), a leading industry association. We measure climate vulnerability by using the Physical Vulnerability to Climate Change Index. This index captures the main structural and physical consequences of climate change that are likely to affect both local communities and mining operations, underlining the centrality of RBC in adaptation in the affected areas. The climate index captures major risks for livelihoods posed by flooding, aridity, temperature shocks, rainfall shocks, and cyclones (Feindouno et al. Reference Feindouno, Guillaumont and Simonet2020; FERDI 2022; Goujon et al. Reference 73Goujon, Santoni and Wagner2022).

The map also shows the overlap of mining dependency and climate vulnerability, delineated by the occurrence of mining dependence in the darker-shaded geographical areas. In several mining-dependent countries, such as Namibia, South Africa, and Yemen, the entire country is characterized by high levels of climate vulnerability. In other mining-dependent countries, such as Australia, Mongolia, and Peru, subnational areas are varyingly vulnerable to climate change. Taken together, this information clearly supports the argument that the mining industry is a high-risk sector where RBC in adaptation is critical to prevent and mitigate severe socio-environmental harm.

Moreover, the mining sector is an important case, as many companies have voluntarily adopted RBC policies to manage their relationships with host communities. While practices vary widely across companies, the most advanced companies usually have policies and procedures for socio-environmental risk assessment, information disclosure, participation, and often make CSR investments to showcase their positive contribution to local development. Thus, we expect companies to build upon and integrate climate adaptation into existing RBC policies and procedures developed to govern interactions with local communities and state agencies concerning the management of socio-environmental risks. At the same time, a substantial body of literature has found that RBC principles are often poorly implemented in the mining sector. For example, EIAs and participatory processes have frequently failed to provide local communities either with access to relevant information about socio-environmental risks or meaningful participation in decision-making processes involving large-scale mining projects (Murguía and Bastida Reference Murguía and Bastida2024). Furthermore, companies have used CSR investments to buy off opponents, aiming to avoid costly conflicts with local communities (Amengual Reference Amengual2018; Franks et al. Reference 72Franks, Davis, Bebbington and Scurrah2014).

Consequently, the mining sector represents a case where companies can build on existing RBC policies, but at the same time where there are significant barriers related to poor public governance and ineffective voluntary standards. By investigating how companies in the mining sector implement the RBC principles in adaptation, we provide important lessons with applicability to other sectors. To analyze RBC in adaptation, we developed a new qualitative and quantitative dataset.

Mapping Responsible Business Conduct in Adaptation through a Quantitative Dataset

To explore the first part of our theoretical framework, we descriptively map the extent to which companies have integrated the RBC principles into their adaptation responses. For this purpose, we compiled a dataset based on a qualitative coding of documents from the world’s thirty-seven largest mining companies according to their market capitalization in 2019 (PWC 2019; see Appendix A; Table A1). An inductive coding of all available documents from 2017 to 2019 resulted in a company-level dataset with the capacity to descriptively map companies’ perceptions of climate risks, adaptation responses, and RBC (see Appendix B; Tables B1, B2, and B3). The corporate documents we compiled for our research include annual reports, sustainability reports, reports to the Carbon Disclosure Project, Global Reporting Initiative reports, as well as policies and reports available on the companies’ websites. The time period covered begins in 2017, prior to which the observed companies disclosed little or no information on their adaptation responses, conditions that rendered them ill-suited for analysis.

To operationalize the RBC principles, we confronted the challenge that many companies do not explicitly label their responses to climate risks as “adaptation.” Rather, they tend to use several terms, like flood risk management, risk assessments, and resilience, somewhat interchangeably (see also Averchenkova et al. Reference Averchenkova, Crick, Kocornik‐Mina and Leck2016). This makes it difficult – but not impossible – to identify different types of activities that would here be classified as “adaptation” (Dupuis and Biesbroek Reference Dupuis and Biesbroek2013). Thus, we examined the documents in conjunction with the interviews described later to operationalize the four principles (see also Section 3). More specifically, we coded whether companies adhered to the four RBC principles, as we describe in detail in Section 3 and Appendix B; Table B3. We also used the documents to measure a range of other aspects, including whether companies framed climate-related risks as economic and/or societal, and how they responded to these risks organizationally. This is useful information to set the stage for the mapping of the RBC principles.

Relying on company self-reporting of corporate adaptation has the advantage that we can generate this quantitative dataset, but as with any measurement approach, it also has limitations. Companies’ reporting is often fragmented, biased, and vague and it should, therefore, be treated as a strategic communication tool employed by companies to present themselves as leaders in upholding voluntary sustainability standards. Therefore, the quantitative document analysis may overestimate RBC in adaptation and must be interpreted with caution.

To provide a more balanced analysis, we complement the quantitative data with eighty-seven semi-structured interviews with representatives of companies, business associations, civil society, and the public sector during the period 2020–2022. We transcribed and coded all interviews in Atlas.ti. We conducted forty-one of the eighty-seven interviews in relation to our dataset of the world’s largest mining companies (see Appendix C). The main aim of these interviews was to contextualize the quantitative coding of the RBC principles. In this way, this Element offers a context-sensitive and critical analysis of how corporate actors perceive climate risks, adapt their practices, and adhere to RBC principles when adapting to climate risks (Section 3).

Explaining Responsible Business Conduct in Adaptation through Case Studies

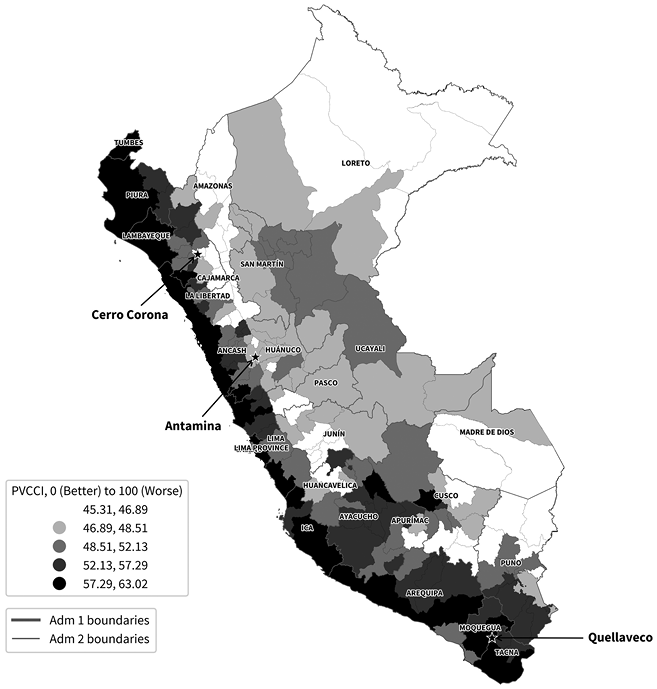

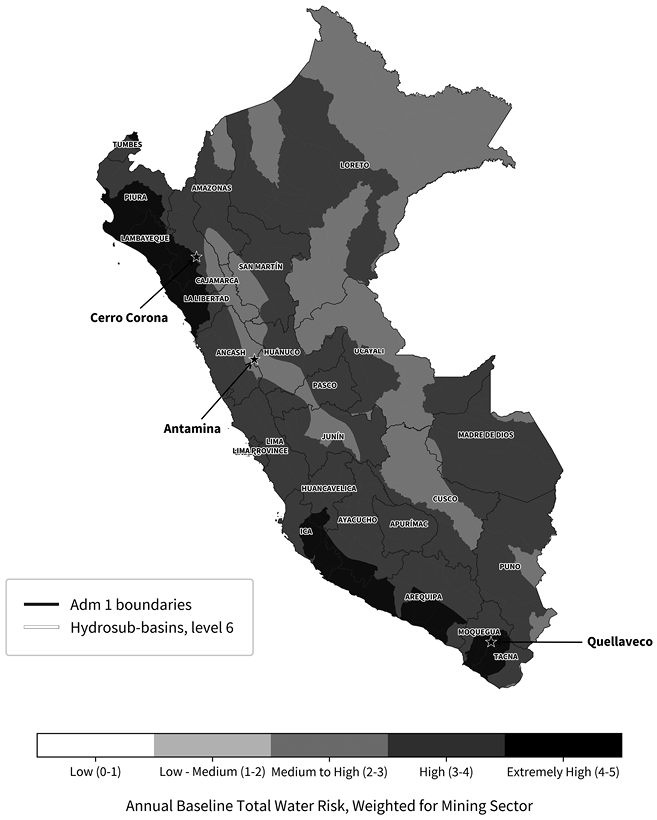

To explore the second part of our theoretical framework laying out the factors that may explain RBC in adaptation, we conducted qualitative case studies on three mining projects in Peru. The selected mines in Peru include Antamina, Cerro Corona, and Quellaveco. Figure 1 indicates that these three projects are situated in Peruvian provinces, which are highly vulnerable to climate risks. Generally, Peru is not among the most vulnerable mining-dependent countries, but climate vulnerability is unevenly distributed across its provinces.

The case studies enabled a more nuanced and context-sensitive analysis of how each of the three factors shaped companies’ integration of the RBC principles. These mining companies rank among the most socially and environmentally responsible in the sector (RMI 2022). Studying how they implement the principles at the operational level enables us to identify important barriers to fostering greater RBC in adaptation (Section 4). We conduct the analysis of the three cases on the basis of material collected during four weeks of fieldwork conducted in the three mining localities and in the capital, Lima, in November and December 2022. We conducted forty-six interviews with representatives of the three mining companies, state agencies at both the national and subnational levels, and civil society and grass-roots organizations who work on climate adaptation, mining, or both (see Appendix C). We use these interviews to operationalize the three theorized explanatory factors and offer a context-sensitive analysis of the three cases.

To analyze public governance in Peru, we analyzed national-level legal requirements to integrate RBC into key sectoral policies, including EIAs, water licenses, the design of tailing dams, and closure plans. We also relied on the interviews to investigate subnational and national authorities’ attempts to influence the companies through soft steering, such as partnerships, dialogues, and production of data on climate risks. Regarding the role of voluntary adaptation standards in shaping RBC in adaptation, we used both the quantitative dataset described earlier and interviews with company representatives to identify the most commonly used standards and then used documents describing the standards to analyze the extent to which these standards covered RBC principles. Subsequently, we interviewed representatives of the three companies to understand how they perceived the influence of these standards on their adaptation responses. Finally, we interviewed representatives from civil society and the three companies to investigate how civil society advocacy mattered RBC in adaptation. In summary, the case studies enabled us to systematically explore the theoretical framework in a context-sensitive manner.

1.3 Findings and Contributions

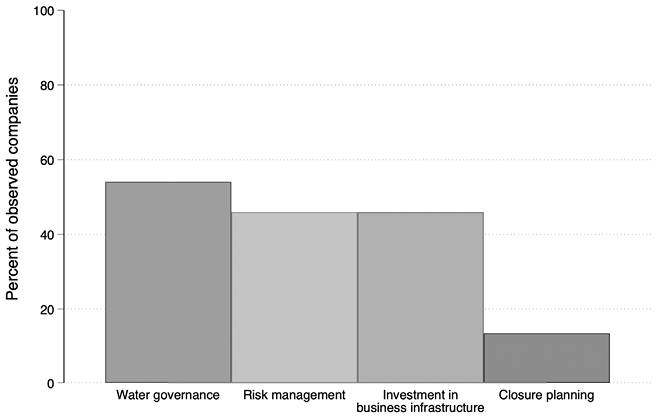

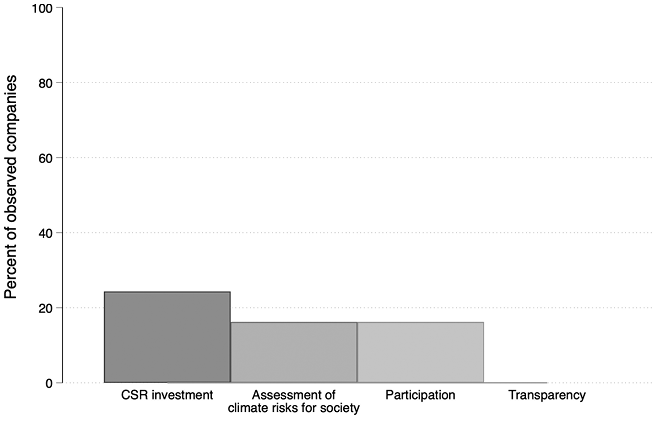

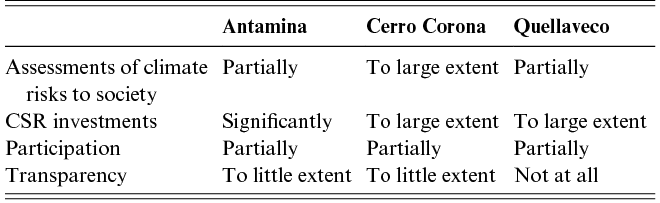

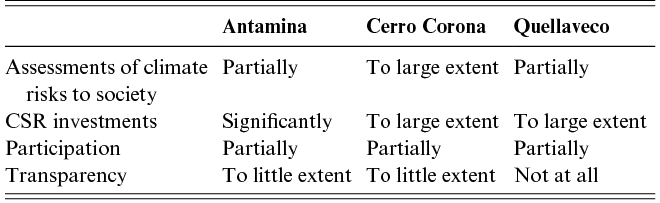

The central findings are twofold. First, both the quantitative and qualitative evidence suggest that companies have primarily addressed climate adaptation through conventional CSR, rather than more meaningfully incorporating other more procedurally oriented components of RBC. While 24 percent of the companies reported upon having made CSR investments in adaptation, 16 percent of the companies reported upon assessing climate risks to society and set up stakeholder participation processes in adaptation interventions. None of the companies lived up to the transparency principle and disclosed information to affected groups and governmental agencies about their adaption responses. Consequently, while there appears to be a group of sustainability frontrunners that have begun to integrate RBC principles into their adaptation strategies, most companies are found to continue to approach adaptation primarily as a matter of business resilience.

Second, based on the qualitative case studies from Peru, our findings underpin the theoretical expectations regarding the combined impact of public governance, private voluntary standards, and CSO advocacy on RBC in adaptation. Our analysis shows that these factors have primarily incentivized companies to make CSR investments, rather than pressuring them to integrate the procedurally oriented principles (risk assessments for society, stakeholder participation, and transparency). Regarding the influence of public governance on RBC, the Peruvian government has primarily encouraged companies to form partnerships to secure CSR investments in water infrastructure, rather than imposed legal requirements for companies to integrate the RBC principles in key sectoral policies.

Similarly, civil society advocacy has largely focused on demanding CSR investments to help affected communities to cope with the combined effects of mineral extraction and climate change. Companies in the three cases have adopted voluntary adaptation standards, which have contributed to spreading norms about RBC principles. However, the lack of strong enforcement mechanisms and in the absence of the countervailing power of public governance and civil society advocacy, these standards have had limited effects on company behavior. Taken together, we see some indications of an emerging discourse on RBC in adaptation. But companies have to date only made half-hearted attempts to change their behavior by more meaningfully incorporating the RBC principles in adaptation responses at an operational level.

Although these findings are based on analyses of the mining sector, we expect them to be generalizable mainly to two contexts. First, our findings are particularly relevant for land- and water-intensive sectors, such as energy, food, oil, gas, hydropower, and large-scale agriculture. In these sectors, corporate adaptation is likely to influence local ecosystems and communities. The findings may also be relevant for working conditions in other industries increasingly exposed to heat waves, where climate adaptation is i recognized as essential for protecting workers (Judd et al. Reference Judd, Bauer, Kuruvilla and Stephanie2023). Second, our findings are also likely to apply to climate-vulnerable countries reliant on key commodities, where economic dependence may make governments hesitant to enforce stricter regulatory controls on businesses.

With these considerations in mind, our findings contribute to two ongoing debates related to corporate adaptation governance and public–private sector interactions, as discussed at length in Section 5. First, they engage with an emerging and growing literature on the role of the business actors in adaptation (e.g., Averchenkova et al. Reference Averchenkova, Crick, Kocornik‐Mina and Leck2016; Berkhout Reference 70Berkhout2012; Gasbarro and Pinkse Reference Gasbarro and Pinkse2016; Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Turner, Gladstone and Hole2019; Grabs et al. Reference Grabs2026; Gustafsson et al. Reference Gustafsson, Rodriguez-Morales and Dellmuth2022; Linnenluecke et al. Reference Linnenluecke, Stathakis and Griffiths2011; Mbanyele and Muchenje Reference Mbanyele and Muchenje2022; Shi and Moser Reference Shi and Moser2021). While several of these studies have concluded that companies rarely take societal impacts into account when addressing climate risks (e.g., Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Turner, Gladstone and Hole2019; Shi and Moser Reference Shi and Moser2021), this behavior is, as Averchenkova and colleagues (Reference Averchenkova, Crick, Kocornik‐Mina and Leck2016) point out, an under-researched topic. This study advances emerging debates about the role of companies in adaptation governance by conceptualizing, explaining, and providing for the first systematic analysis of RBC in the context of adaptation.

Second, this study offers insights into the relationship between businesses and the state in the area of adaptation. While a substantial literature has analyzed private–public sector relations in sustainability governance more broadly (Cashore et al. Reference Cashore, Knudsen, Moon and van der Ven2021; Eberlein Reference Eberlein2019; Lambin and Thorlakson Reference Lambin and Thorlakson2018), there are relatively few studies focused on adaptation (notable exceptions are Klein et al. Reference Klein, Araos, Karimo and Heikkenen2018; Pauw and Pegels Reference Pauw and Pegels2013). Our findings reveal that, to date, Peruvian public authorities have relied on soft steering to incentivize companies to fund adaptation infrastructure, rather than imposing regulatory controls. However, without strict legal requirements, such soft regulatory approaches have proven ineffective in promoting significant change in corporate behavior.

1.4 The Structure of the Element

This Element is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces our theoretical framework on RBC in climate adaptation. Section 3 explores the first part of this framework, mapping how the world’s largest mining companies understand climate risks, engage in adaptation, and integrate the four RBC principles, based on our quantitative database. In turn, Section 4 turns to the second part of our framework and analyzes how regulatory and political factors shape RBC in adaptation based on the case studies in Peru. Section 5 summarizes our key findings, discusses those findings against the backdrop of previous research, and outlines their broader implications for the future of climate adaptation governance.

2 A Theoretical Framework for Studying Responsible Business Conduct in Adaptation

As Section 1 established, gaining a deeper understanding of how firms approach RBC principles in adaptation is critical in the context of increasingly severe climate impacts. In this section, we provide a detailed account of our two-part theoretical framework, which was briefly introduced in Section 1. In the first part (Section 2.1), we conceptualize the principles, which cover both procedural and distributive aspects of RBC. Drawing on literatures on private governance, Business and Human Rights, and climate adaptation, we discuss how these general principles manifest in the adaptation context and why we regard them as critical. In the second part (Section 2.2), we discuss different regulatory and political factors which are likely to shape RBC in the context of adaptation. We zoom in on public governance, private voluntary standards, and civil society advocacy and discuss how each is likely to influence business behavior.

2.1 Corporate Responsibility Principles in Climate Adaptation

We define RBC as the behaviors of companies which avoid and address the negative impacts of their activities, while also fostering sustainable development in the countries where they have operations (cf. OECD n.d.). Although it is a central concept in the literatures on CSR and Business and Human Rights, it has not yet been transposed to the context of climate adaptation. The RBC principles we elaborate on in the following section cover the procedural and distributive dimensions that enable us to go beyond the “do no harm” approach of proceduralist approaches and include principles which could potentially capture distributive outcomes. We do not claim that this constitutes a comprehensive overview of all RBC principles embedded in international soft and hard law. For example, we do not include corporate governance and access to remedy, both of which are central components of HREDD. However, we argue that the selected principles together capture the initial expressions of central principles that are particularly relevant for preventing socio-environmental harm and for developing regulatory policies addressing the intersecting impacts of climate change and business activities on society.

Assessments of Climate Risks to Society

Assessing climate risks to society enables companies to identify and address potential harms linked to their operations, making it an important procedural principle for preventing harms before they occur. We understand assessments of climate risks to society as the obligation of companies to adequately evaluate the societal risks associated with their business activities in a context of climate change. Climate risk assessments involve a technical analysis of the likelihood, responses, and consequences tied to climatic impacts, and the options available to redress them (see also Adger et al. Reference Adger, Brown and Surminski2018). While many companies have procedures to assess their own risk exposure, including those ensuing from climate impacts, addressing socio-environmental risks requires shifting the focus toward the external risks posed by their own activities.

To gather sufficiently rigorous data, companies must conduct a complex technical analysis that will yield reliable data showing how climate impacts could exacerbate, or even create, new socio-environmental risks linked to their business activities. In the mining sector, companies must ensure that tailings dams withstand intense rains (Hopkins and Kemp Reference 74Hopkins and Kemp2021). In the agroindustry, companies also must assess the short- and long-term effects of their water use (cf. Rattis et al. Reference Rattis, Brando, Macedo and Spera2021). Meanwhile, in the apparel industry, the effects of extreme heat and floodings on workers’ health and safety must be carefully analyzed (Judd et al. Reference Judd, Bauer, Kuruvilla and Stephanie2023).

To carry out climate risk assessments, companies can integrate climate risks into existing forms of risk assessments. For example, in the case of major projects, companies in most countries are legally required to conduct EIAs and are thereby already assessing their potential impacts on the environment and, in some cases, on society (Lawrence and Kløcker Larsen Reference Lawrence and Kløcker Larsen2017). Moreover, HREDD frameworks give companies tools to ascertain the human rights and environmental risks associated with their business activities, though climate change, and environmental issues more broadly, have often been poorly integrated in such procedures (Bernaz Reference Bernaz2016; Macchi Reference Macchi2022). Hence, companies could integrate climate adaptation into existing methods of risk assessment rather than developing new ones.

Despite the potential to integrate climate adaptation into existing risk management procedures, barriers hinder companies from carrying out such assessments. One major challenge lies in the complexity and uncertainty of these assessments, which can reduce companies’ motivation to conduct them. Climate impacts can have immediate, short-term, and long-term consequences. In some cases, the impacts do not arise until after a company has ceased its operations. In addition, companies must contend with the uncertainty surrounding future climate projections, specifically in assessing long-term impacts and the effectiveness of adaptation interventions (Adger et al. Reference Adger, Brown and Surminski2018). Research shows that perceived uncertainty influences how much attention companies allocate to climate impacts and whether they adopt more rigorous adaptation responses (Pinkse and Gasbarro Reference 78Pinkse and Gasbarro2019).

In sum, assessing climate risks to society is a procedural principle that enables companies to address harms before they occur and can often be integrated into existing risk assessment procedures. But significant challenges remain due to the complexity of analyzing how business activities might interact with climate change. That these assessments also support other procedural principles such as participation and transparency makes them even more essential for RBC in adaptation.

Participation

Meaningful participation ensures that affected groups can influence how their perspectives and adaptation needs are integrated into corporate adaptation responses. Specifically, we refer to participation as the engagement of relevant stakeholders in the planning and implementation of adaptation interventions (Eriksen et al. Reference Eriksen, Schipper, Scoville-Simonds and Vincent2021; Shi et al. Reference Shi, Chu, Anguelovski and Aylett2016). According to the UNGPs (OHCHR 2011) and the OECD Guidelines (2023), companies shall consult stakeholders throughout the process of assessing and addressing environmental and human rights risks. Companies can consult affected stakeholders regarding climate risk assessments and the implementation of adaptation activities. This is especially important when corporate adaptation efforts impact the land and water that local communities rely on for their livelihoods (cf. OECD 2023: 20).

Depending on their purpose, quality, and outcomes, participatory processes may give vulnerable and marginalized groups greater voice and influence (Dellmuth and Gustafsson Reference Dellmuth and Gustafsson2023; Gustafsson and Schilling-Vacaflor Reference Gustafsson and Schilling-Vacaflor2022). To foster meaningful stakeholder consultations, the OECD Guidelines stipulate that companies shall set up participatory processes that are “timely, accessible, appropriate and safe for stakeholders” (OECD 2023: 20). They further underscore the importance of identifying and removing potential barriers to engagement with vulnerable and marginalized groups (OECD 2023: 19).

However, participatory processes have often not enabled the influential participation of marginalized groups. For example, adaptation interventions led by public actors have often suffered from shortcomings when it comes to setting up inclusionary participatory processes (Eriksen et al. Reference Eriksen, Schipper, Scoville-Simonds and Vincent2021). Similarly, company-led participatory processes in large-scale projects are often beset by shortcomings such as limited information, time, and influence on decision-making (Lawrence and Kløcker Larsen Reference Lawrence and Kløcker Larsen2017). Consequently, if companies formally involve affected groups in implementing adaptation interventions but fail to provide adequate and accessible information about climate risks, they undermine their ability to voice their concerns and influence corporate adaptation strategies.

Transparency

As the final procedural principle, access to information on climate risk assessments and corporate adaptation responses equips affected groups and public authorities with tools to critically evaluate how companies address climate-related risks arising from their operations. We conceive of transparency as companies’ duty to inform society more broadly about the societal risks associated with their business activities in the context of climate change and of the adaptive measures they have taken to address them (cf. OECD 2023). Access to such information is particularly important in cases where business activities may expose communities and ecosystems to severe risks. For instance, if a company builds a pipeline to transport toxic materials, it must inform local communities of any increased risks for dangerous accidents.

There has been a proliferation of voluntary initiatives and legislation mandating that companies report on their sustainability performance, particularly regarding climate change. Initiatives like the Carbon Disclosure Project and the Global Reporting Initiative have significantly enhanced companies’ reporting about their decarbonization strategies (cf. Pinkse and Gasbarro Reference 78Pinkse and Gasbarro2019). In contrast, few initiatives require companies to disclose information about their adaptation strategies.

Corporations tend to be very cautious in disclosing information about their adaptation interventions (Gustafsson et al. Reference Gustafsson, Rodriguez-Morales and Dellmuth2022). Unless required to do so, those operating in high-risk sectors, such as extractive industries or agroindustry, generally have few incentives to be transparent about the risks they face, as doing so could provoke conflicts that disrupt their operations. This situation is very different in the climate mitigation space, where companies are strongly motivated to showcase their contributions to the low-carbon transition (Jernnäs and Lövbrand Reference Jernnäs and Lövbrand2022).

Although climate risk assessments are technically complex and their results uncertain, companies must find a way to present the information they gather in a format that is relevant and easily accessible to affected groups (cf. Gardner et al. Reference Gardner, Benzie, Börner and Dawkins2019; OECD 2023). Without such information, local populations and public institutions will struggle to evaluate corporate adaptation responses. In turn, this may undermine local and public actors’ attempts to hold companies accountable and hinder the establishment of a democratic dialogue on the impacts of business activities within the context of climate change.

CSR Investments

CSR investments can enable companies to move beyond a “do no harm” approach and make positive contributions to adaptation in the countries where they operate. In our framework, CSR investments are understood as the provision of public adaptation goods by companies (cf. Tompkins and Eakin Reference Tompkins and Eakin2012). Companies can invest in early warning systems, cooling systems, water infrastructure, and capacity building to help affected stakeholders to cope with climate change. Such investments could expand access to public adaptation goods in countries where governments lack the resources to fund the implementation of adaptation plans. The problem is particularly urgent in developing countries, where the annual adaptation costs are expected to reach 140 to 300 billion USD in 2030 and 280 to 500 billion USD in 2050 (UNEP 2021: xiv). According to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), private adaptation funding is essential to reducing this gap (UNEP 2021: xiv).

Against this background, companies could partner with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and state institutions to invest in essential public adaptation goods such as water infrastructure, climate-proofing infrastructure, and capacity building. By channeling CSR investments through institutionalized partnerships that benefit broad swaths of the populations, companies could contribute both through financial support and by expanding state capacity to implement adaptation plans.

At the same time, companies are often unwilling to make CSR investments unless there is a business case (Auld et al. Reference Auld, Bernstein and Cashore2008). CSR investments in the mining sector tend to be aimed at preventing or mitigating conflicts with local communities that could disrupt their economic activities (Franks et al. Reference 72Franks, Davis, Bebbington and Scurrah2014). To defuse opposition, companies sometimes make targeted investments that benefit smaller groups, but create dependency which often undermines long-term local development, civil society organizations, and institutional reforms (Amengual Reference Amengual2018; Bebbington Reference Bebbington, Ravi and Lipschutz2010; Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson2018). In such situations, the existence of CSR investment might reduce local communities’ demands for the procedurally oriented principles. Consequently, it is important to monitor how companies channel these investments, be it either through institutionalized partnerships or bilateral exchanges with small groups or individuals as tools for gaining political support.

2.2 Explaining Corporate Responsibility in Climate Adaptation

Next, having laid out the first part of our theoretical framework, we turn to the second part, where we explain how the three factors external to the firm – public governance, private voluntary standards, and civil society advocacy – shape RBC in adaptation. These factors have been shown to affect corporate behavior more broadly (Bartley Reference Bartley2018a; Lambin and Thorlakson Reference Lambin and Thorlakson2018; Thorlakson et al. Reference Thorlakson, Hainmueller and Lambin2018a), underlining their potential relevance in the specific context of adaptation. While previous studies have analyzed how companies’ exposure to physical climate change (Mbanyele and Muchenje Reference Mbanyele and Muchenje2022) and internal perceptions of these risks (Berkhout Reference 70Berkhout2012; Pinkse and Gasbarro Reference 78Pinkse and Gasbarro2019; see Gasbarro and Pinkse Reference Gasbarro and Pinkse2016) influence corporate adaptation, we focus on how these regulatory and political factors shape RBC in adaptation.

Public Governance

We expect public governance to influence corporate behavior through both legal requirements and soft steering. Public governance refers to the system of organizations, institutions, and networks at domestic and global levels that develop and implement rules and norms for handling societal problems (Weiss and Wilkinson Reference Weiss and Wilkinson2019). We analyze how domestic institutions at both the national and subnational levels require or encourage RBC in adaptation through hard and soft regulatory activities. These forms of governance are important because they can strongly influence corporate behavior by shaping incentives and enforcing compliance.

Legal requirements are central to influence business behavior. For instance, governments can institute legal requirements that climate risks be considered within key sectoral regulatory instruments such as concessions, water licenses, and EIAs. These instruments can act as “market-restricting rules” that governments could employ to limit or prohibit business activities likely to undermine societal and ecosystemic adaptation (cf. Bartley Reference Bartley2018a). In developed countries, the prospect of governmental regulation has been an important driver of corporate climate action, particularly in the area of mitigation (Newell and Daley Reference Newell and Daley2024; Sakhel Reference Sakhel2017). However, legal requirements in the area of adaptation tend to be weaker (Klein et al. Reference Klein, Araos, Karimo and Heikkenen2018), especially in countries in the Global South (Pulver and Benney Reference Pulver and Benney2013; Purdon and Thornton Reference Purdon, Thornton, Keskitalo and Preston2019).

Still, most countries have EIA legislation in place, which can serve as an important instrument for governments to require companies to conduct impact assessments, disclose information, and enable stakeholder participation. Furthermore, EIAs could lead to stricter rules or the suspension of major projects where the negative impacts are deemed too high. While EIA legislation increasingly includes climate mitigation, legal requirements that climate adaptation be taken into account are rare, reflecting that adaptation is not yet institutionalized in sectoral policies (Mayembe et al. Reference Mayembe, Simpson, Rumble and Norton2023). However, some governments have also used EIAs as an instrument to restrict activities deemed to have a negative impact on climate adaptation. For example, in 2017, the Salvadoran government conducted a Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment to evaluate the impacts of mining under conditions of increased water scarcity and climate-related disaster. That assessment resulted in a national ban on metal mining (Odell et al. Reference Odell, Bebbington and Frey2018).

Governments can also use support and soft steering mechanisms, like funding, scientific information, endorsement, partnership, or multistakeholder initiatives to influence companies’ adaptation behavior (cf. Abbott and Snidal Reference Abbott and Snidal2009; Eberlein Reference Eberlein2019). For example, some countries have developed voluntary guidelines on how companies should assess physical climate risks in EIA processes (Strindevall et al. Reference 79Strindevall, Gustafsson and Dellmuth2022). Since knowledge and expertise are often important barriers to tackling climate impacts, clear guidelines can encourage companies to undertake risk assessments for society by making them less costly. Moreover, partnerships and multistakeholder initiatives can provide companies with institutionalized channels through which they can channel CSR investment in public adaptation goods, disclose information, and engage important stakeholders in dialogues on adaptation. However, soft steering processes are often ineffective in changing company behavior unless backed up by a viable threat of mandatory regulation (Börzel et al. Reference Börzel, Hönke and Thauer2012).

To effectively steer or regulate company behavior, public institutions must involve robust monitoring systems capable of assessing the impacts of climate change and evaluating the extent to which companies responsibly assess and redress manifest risks (cf. Lambin and Thorlakson Reference Lambin and Thorlakson2018). While many governments have adopted National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), the quality of the data that emerges is a significant limitation. NAPs are often too generic to capture risks in specific geographic and social contexts (Dolšak and Prakash Reference Dolšak and Prakash2018). Without robust data on climate risks, public authorities cannot provide companies with relevant data or evaluate the adequacy of corporate responses.

Adaptation is often not prioritized by political and economic actors. Where national or subnational economies heavily depend on particular economic activities, the adaptation agenda may become more responsive to corporate interests than to the rights and needs of marginalized groups. In Brazil, for instance, adaptation policies have enabled large-scale agricultural producers to cope with water stress through irrigation infrastructure, often at the expense of marginalized communities who face severe water insecurity as a result (Gustafsson et al. Reference Gustafsson, Schilling-Vacaflor and Pahl-Wostl2024; Milhorance et al. Reference Milhorance, Sabourin, Chechi and Mendes2022a). Overall, it is important to consider the underlying political priorities, power dynamics, and monitoring capacities that shape how legal requirements and soft steering influence company behavior.

Voluntary Adaptation Standards

We expect voluntary adaptation standards to matter for RBC in adaptation through the diffusion of norms about RBC. Voluntary adaptation standards refer to any type of multistakeholder initiative, certification scheme, or private standard that sets requirements designed to increase the sustainability of corporate adaptation responses (cf. Marx et al. Reference Marx, Depoorter, Fernandez de Cordoba and Verma2024). More generally, voluntary sustainability standards typically define specific foundational principles, which are then translated into measurable indicators for monitoring and compliance (Marx et al. Reference Marx, Depoorter, Fernandez de Cordoba and Verma2024: 3). However, standards differ in terms of their institutional design, and although they usually rely on enforcement mechanisms such as audits, they can also rely on market incentives and capacity building to generate compliance (Depoorter and Marx Reference Depoorter and Marx2024). When public governance is weak or lacking, companies are more likely to rely on voluntary standards (cf. Potoski and Prakash Reference Potoski and Prakash2013). This is likely to be the case in adaptation.

While there are no comprehensive voluntary adaptation standards, several standards have integrated climate adaptation to some extent, notably those developed by the Alliance for Water Stewardship, the Sustainable Agriculture Initiative, and the Responsible Business Initiative. In the mining sector, ICMM and the Global Tailings Review have developed industry-specific standards which include adaptation (Hopkins and Kemp Reference 74Hopkins and Kemp2021). Such standards can contribute to learning and thereby facilitate businesses uptake of RBC principles (cf. Depoorter and Marx Reference Depoorter and Marx2024).

The private governance literature yields mixed evidence about whether voluntary standards lead to meaningful improvements in the sustainability practices of firms (Marx et al. Reference Marx, Depoorter, Fernandez de Cordoba and Verma2024; Thorlakson et al. Reference Thorlakson, Hainmueller and Lambin2018a). A study by Thompson and colleagues (Reference Thompson, Davis, Mosley-Thompson and Porter2021) on the effects of certifications on the climate resilience of cocoa farmers in Ghana showed some positive impacts on farm management practices, but found significantly weaker effects on more complex adaptation measure. This is likely due to the continued lack of clarity regarding what constitutes adaptation, which makes it challenging for standard setters to develop and monitor appropriate measures. More generally, numerous studies have shown that voluntary standards are often insufficient for preventing or rectifying serious problems due to limited uptake, lack of stringency, poor-quality auditing, and a tendency toward symbolic compliance (Bartley Reference Bartley2018b; LeBaron et al. Reference LeBaron, Lister and Dauvergne2017).

Companies usually adopt voluntary standards for utilitarian reasons (de Bakker et al. Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019). Retailers with high-profile consumer brands, who are more exposed to CSO scrutiny, have shown a greater tendency to adopt sustainability standards compared to business-to-business firms (Thorlakson et al. Reference Thorlakson, Hainmueller and Lambin2018a). Additionally, researchers have concluded that the use of public monitoring systems and legal enforcement mechanisms contribute to more meaningful compliance with voluntary standards (Lambin and Thorlakson Reference Lambin and Thorlakson2018). In sum, while voluntary standards can contribute to learning about RBC in adaptation, meaningful adoption and compliance by profit-maximizing firms tends to depend on incentives or external pressures, with civil society advocacy often playing an important role.

Civil Society Advocacy

Finally, we expect CSO advocacy to influence RBC not only by pressuring them to adopt voluntary adaptation standards but also to develop more inclusionary and transparent adaptation responses.

Here, civil society advocacy refers to a civil society-based form of corporate regulation (cf. Newell Reference Newell2008), in which NGOs, social movements, grassroots organizations, labor unions, and other civil society actors pressurize companies to change their behavior (cf. Dellmuth and Bloodgood Reference Dellmuth, Bloodgood, Dellmuth and Bloodgood2023). CSOs have often played a critical role in scrutinizing companies and incentivizing companies to disclose information, to reduce the negative impacts of their business activities, to invest in CSR, to adopt voluntary sustainability standards (Bartley Reference Bartley2018b; Franks et al. Reference 72Franks, Davis, Bebbington and Scurrah2014; Thorlakson et al. Reference Thorlakson, Hainmueller and Lambin2018a), and to comply with legal requirements (Kramarz et al. Reference Kramarz, Mason and Partzsch2023).

CSOs pursue a range of advocacy strategies, such as generating and disseminating alternative data about the impacts of business activities (Kramarz et al. Reference Kramarz, Mason and Partzsch2023), engaging in highly visible naming-and-shaming campaigns (Balsiger Reference Balsiger2014), and interacting closely with companies through multistakeholder initiatives (Gustafsson Reference Gustafsson2018). In particular, the deployment of visible campaigns could pressure companies to integrate RBC. Campaigns that show the consequences of failing to address climate risks can lead to consumer boycotts, investor demands for action, and other potential consequences that reputation-sensitive businesses usually seek to avoid (Balsiger Reference Balsiger2014). Concerns about reputational harm might lead companies to improve climate risk assessments, develop their adaptation responses in a more transparent and inclusionary way, and support societal adaptation through CSR investments.

However, civil society advocacy in the field of climate adaptation has been relatively weak, in part because adaptation is often framed as a technical and depoliticized problem. In sharp contrast to civil society campaigns against carbon-intensive industries (Boulianne et al. Reference Boulianne, Lalancette and Ilkiw2018), activists have rarely engaged in open protests to pressure governments and corporations to intensify their efforts to promote climate adaptation (de Moor Reference de Moor2022). Social movement scholars have stressed that CSO mobilization around systemic issues, where responsibility is diffuse and specific attribution challenging, is generally less likely to occur (Carpenter Reference Carpenter2007). This is certainly the case with corporate adaptation, where it can be difficult to provide robust evidence on a given corporation’s impact on community and ecosystem resilience. At the same time, local protests over climate-related impacts are common – especially in industries that require the intensive use of land and water – even if they are not explicitly framed in terms of climate change (Leme da Silva et al. Reference Leme da Silva, Eloy, Oliveira and Coelho Filho2023; Odell Reference Odell2021; Urkidi Reference Urkidi2010).

Overall, while CSO advocacy has the potential to pressure companies to integrate RBC principles into their adaptation responses, its role in shaping corporate behavior depends on the ability of civil society actors to mobilize collectively and articulate concrete, actionable demands regarding corporate responsibilities in the face of climate risks.

2.3 Conclusion

This section has developed a theoretical framework for understanding the main outcome of interest, RBC in the context of climate adaptation. Drawing on literatures on private governance, Business and Human Rights, and climate adaptation governance, we proceeded in two steps. First, we conceptualized four RBC principles in adaptation, each of which is essential for preventing and mitigating the socio-environmental harms associated with business activities under climate change and foster more coordinated private and public governance of such impacts. To move beyond a “do no harm” approach, we also included one distributive principle: CSR investments in public adaptation goods. Second, we developed an argument about three regulatory and political factors that we expect to explain how companies integrate these principles into their adaptation responses. Our explanation privileges public governance, voluntary adaptation standards, and civil society advocacy.

The empirical analysis in the next section will draw on the first part of this framework, while the subsequent section will apply the full framework.

3 Mapping Responsible Business Conduct in Adaptation

This section explores the first part of our theoretical framework by descriptively mapping the extent to which the world’s largest mining companies have integrated the RBC principles into their adaptation responses. For this purpose, we draw on the dataset introduced in Section 1, which is based on a content analysis of corporate documents from the world’s thirty-seven largest mining companies and on semi-structured interviews.

To set the stage for the descriptive mapping, we begin by providing contextual information about mining companies’ perceptions of climate risks and their organizational responses to adaptation problems (Section 3.1). We then proceed to mapping the variation in the main outcome of our theoretical framework, RBC in adaptation, operationalized as the extent to which firms adhere to the four conceptualized principles for RBC in adaptation (Section 3.2). The section concludes with a brief summary and a discussion of the evidence in light of our argument (Section 3.3).

3.1 Firms’ Perceptions of Adaptation Problems

Before mapping companies’ adherence to the RBC principles, we begin by describing how mining companies make sense of climate risks in the first place. More specifically, we analyze whether companies perceive climate change as an economic risk or as one with implications for both the economy and society. Relying on the notion of “risk” makes sense here, as companies’ conventional methods of risk management are typically focused on their own exposure; risks for business resilience tend to be incorporated into a company’s risk management framework (Higham Reference Higham, Olsen, Juhl, Lindoe and Engen2019). In contrast, approaching climate risks from a societal perspective reflects a more comprehensive and context-sensitive understanding of how biophysical processes and economic activities interact to produce societal climate vulnerability (cf. Bassett and Fogelman Reference Bassett and Fogelman2013; Odell et al. Reference Odell, Bebbington and Frey2018).

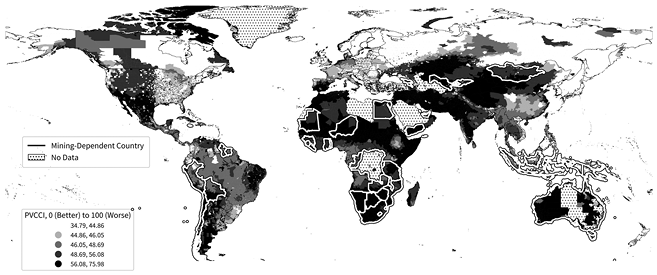

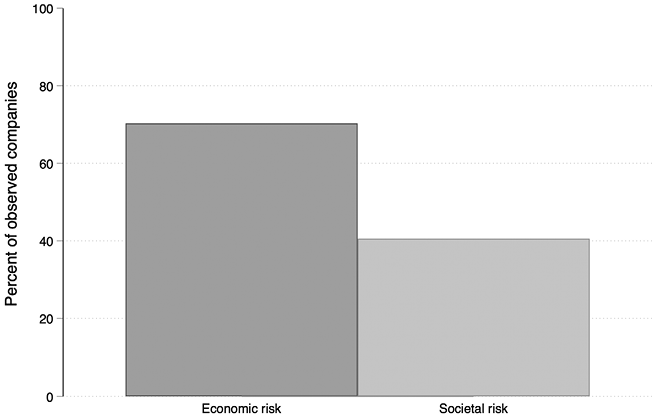

Climate adaptation, for the majority of companies in our sample, is at least not primarily aimed at mitigating societal climate vulnerability, but a strategic response to the economic risks it poses to their operations and long-term profitability. Figure 2 shows that among the thirty-seven companies in our sample, 70.3 percent portrayed climate impacts as an economic risk to their business operations (N = 26). Company reports describe how floodings, increased storm intensity, and high temperatures could damage mining infrastructure, exacerbate water stress, disrupt production processes, and result in costly litigation. However, only half of the companies identified climate impacts as a “critical” or “principal risk.” The extent to which companies prioritize adaptation is also shaped by the extent of their risk exposure. For instance, some, like Antofagasta, have all their operations in water-stressed areas, while others, like Anglo American, have a majority of their operations in such regions (Anglo American 2019; Antofagasta 2019).

Interestingly, companies’ perceptions of economic risks differ significantly between adaptation and mitigation, suggesting that adaptation is not the main priority for many companies. Our document analysis reveals that a majority of the companies recognize that the failure to reduce their own greenhouse gas emissions is a critical risk likely to have significant financial impacts. Yet concerns of this kind appear less salient in the adaptation context. Interviewees in the companies highlighted several reasons for mining companies’ seeming reluctance to recognize climate impacts as a critical risk for their own operations, including the inability to accurately assess the magnitude of future climate-driven impacts, the cost of adaptation, and the absence of strict regulatory controls (Interviews 9, 10, 45).

Some mining companies have begun to frame climate change as a societal risk, recognizing that harm to surrounding communities can lead to reputational damage for the company. Returning to Figure 2, our research demonstrates that 40.5 percent of the thirty-seven companies see climate impacts as a societal risk (N = 15). These companies expressed particular concern regarding the possibility that climate change could lead to water stress and tailings dam failures, events that could affect their reputations and lead to local protests. As one company representative stated: “If we don’t have water available for the affected communities and we don’t meet our commitments, the operation will shut down. Just like that. I mean water is as important as gold” (Interview 2).

To address the economic and social risks associated with climate change, effective water management is generally considered a key adaptation intervention (ICMM 2017; Interviews 2, 41). Water is one of the most important drivers of community protests against mining projects. Several mining-dependent countries, most prominently Bolivia, Chile, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mongolia, Namibia, Peru, and South Africa, face high or extreme levels of water stress (Strindevall et al. Reference 79Strindevall, Gustafsson and Dellmuth2022). Moreover, intense rainfalls can lead to dangerous accidents and severely harm surrounding communities and environments. A case in point is the catastrophic failure of Vale’s tailings dam in Brumadinho, Brazil, in 2019, which cost over 250 people their lives and caused significant material destruction (Hopkins and Kemp Reference 74Hopkins and Kemp2021).

In sum, while most mining companies perceive climate impacts primarily as an economic risk to their operations, far fewer recognize the broader societal dimensions of climate vulnerability. Water stress, in particular, emerges as a critical issue – both as a driver of community conflict and as a fundamental challenge to long-term operational resilience.

Figure 2 Company perceptions of adaptation problems.

Notes: N = 37 companies. Pooled data for the period 2017–2019 from company documents. The indicators were coded Yes = 1/No = 0 for each company based on the following questions. Economic risk: Do companies recognize climate change as a risk for business performance and continuity? Societal risk: Do companies recognize the physical impacts of climate change as a societal risk? See Appendix B (Table B1) for the detailed coding scheme.

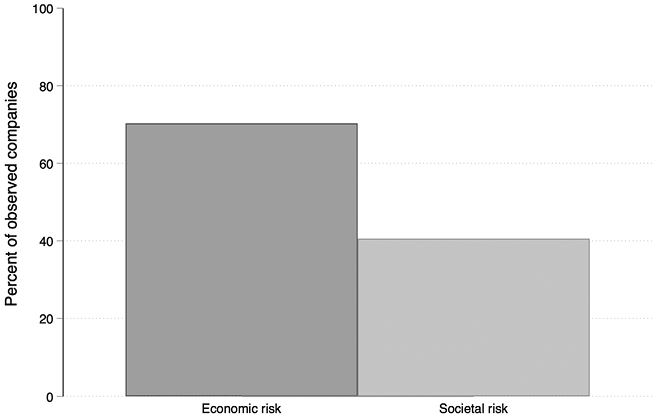

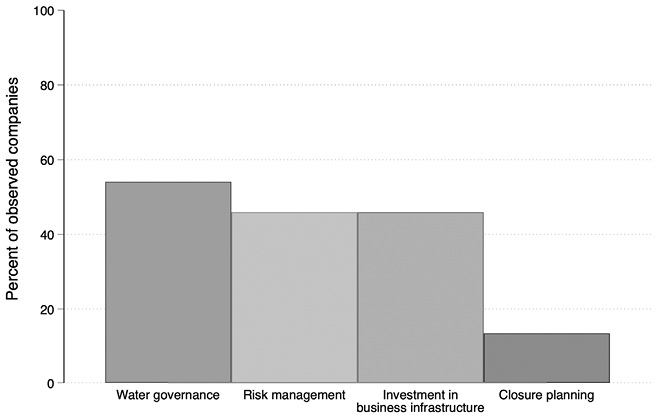

Next, we deem it necessary to analyze how companies have responded to climate risks, before turning to the main outcome of interest, how they considered the societal consequences of their business activities in a context of climate change. In our document analysis, we inductively identified four broad organizational responses to climate risks: water governance, risk management, investments to climate-proof infrastructure, and mine closure. Figure 3 shows that 54.1 percent of companies integrated climate risks into water governance (N = 20), 48.4 percent incorporated climate risks into risk management (N = 18), 46.0 percent made investments to climate-proof their infrastructure (N = 17), and 13.5 percent sought to redress climate risks in their plans for mine closures (N = 5).

In the following, we briefly discuss each of these four organizational responses, beginning with the most frequently observed type of response: water governance. First, organizational responses to water stress represent an important adaptation response in the mining sector, with 54.1 percent of companies taking steps to monitor and set targets for reducing their water consumption. Several of these companies report using screening tools developed by NGOs, such as the World Wildlife Fund for Nature and the World Resources Institute, to make initial assessments and identify areas under severe water stress. Based on these screening tools, companies have developed water balance models that consider climate impacts, set targets to reduce their consumption of freshwater, and increase water recycling or use of seawater in water-stressed areas. However, an interviewee experienced with global-level screening pointed out the need to complement this information with more granular local data on water resources and usage (Interview 87). Indeed, a water expert working at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) office in Peru emphasized that it is almost impossible to discern the water footprint of mining companies from the outside, as they do not disclose the indicators they use. Neither are companies inclined to be transparent about water pollution (Interview 31), which is a severe and longstanding problem for local communities (Lèbre et al. Reference Lèbre, Stringer, Svobodova and Owen2020). Consequently, it is difficult to assess whether the measures taken to improve water governance adequately address the climate change-related challenges associated with water stress.

Second, to develop adaptation responses, companies need a solid understanding of climate risks. Mineral extraction is extremely sensitive to different types of climate-related risks such as droughts, flooding, and rising temperatures (Phillips Reference Phillips2016). Reflecting companies’ need for understanding such risks, 48.4 percent of the companies have incorporated climate impacts into their conventional risk assessment and management frameworks. All but one of them report having conducted site-based climate risk assessments and integrated climate risks in their risk management procedures. Most companies have developed internal capacities within their environmental units to monitor climate risks, sometimes in partnership with external consultants. Several interviewees working with climate risk assessments within the mining companies highlighted that a major challenge was combining the IPCC’s five global climate scenarios with their own local data to make reliable predictions about short- and long-term climate impacts (Interviews 6, 7, 36).

All companies that reported integrating climate adaptation into their risk management procedures stated that their board had oversight of climate-related risks, making it almost certain that the topic is discussed at senior management levels and within the board. This not only indicates the companies’ recognition of the problem’s importance but also that climate-related risks are likely to be integrated into business strategies, even if our data do not reveal how much priority companies actually give to climate adaptation.

Figure 3 Company responses to adaptation problems.

Notes: N = 37 companies. Pooled data for the period 2017–2019 from company documents. The indicators were coded Yes = 1/No = 0 for each company based on the following questions: Water governance: Do companies integrate climate risks in water governance? Risk management: Do companies integrate climate risks in their procedures for risk assessment and management and business plans? Infrastructure investment: Do companies invest in climate-proofing their own infrastructure? Closure planning: Do companies consider climate change in their mine closure plans? See Appendix B (Table B2) for the coding scheme.

Third, in response to the growing impact of droughts and extreme weather events on mining operations, 46.0 percent of the companies reported making investments to climate-proof their infrastructure. The most common investments were in measures to ensure that tailings dams could withstand intense rainfalls, and technological adjustments and water storage infrastructure to cope with water stress. While these companies often provided specific examples of technical solutions to climate-proof their infrastructures, they tended not to disclose the total amount spent on these investments. Newmont is an exception. The company reported that it cost “tens of millions of dollars” to update its infrastructure over the prior three years (Newmont 2019: 34). However, this information cannot be readily verified, and it is impossible to determine the significance of the investment in relation to the identified climate risks.

Fourth and finally, after mining activities have ended, they often leave behind dangerous waste that can pollute land and water, making mine closure a critical process for preventing long-term environmental harm – especially as future climate impacts like heavy rainfall or flooding could make these risks even worse (Macklin et al. Reference Macklin, Thomas, Mudbhatkal and Brewer2023). Yet only 13.5 percent of companies reported accounting for climate change in their closure planning. Failing to do so could expose surrounding communities and ecosystems to serious and lasting harm.