1 Introduction

… the enhancement of human freedom is both the main object and primary means of development.

Why do well-intentioned developmental policies so often fail? Consider the recent collapse of a well-constructed peace agreement between Colombia’s government and FARC guerrillas. In Russia, the rapid privatization of Soviet assets fostered authoritarian kleptocracy. Consider the eruption of Hindu-Muslim violence and mass dislocation following the 1947 partition of India from Pakistan – a tragic aftermath of the decades-long struggle for independence from Britain. In Indonesia, transnational palm oil companies adopted socially responsible company policies banning deforestation and observing local rights to free, prior, and informed consent. Yet, implementation failed due to the cooptation of village leaders, secret deals, and intimidation (Afrizal and Berenschot, Reference Afrizal and Berenschot2020).

Why such failure? Powerful agents intervene. Others follow.

Functional development entails resolving social dilemmas embedded within myriad collective-action problems. The overarching developmental dilemma concerns how to create a sustainable path to inclusive political and economic development. How might a society establish and nurture broadly distributed political and economic capabilities when powerful agents so often benefit from non-inclusive extractive interactions founded in persistent socially wasteful, exploitative, and repressive relationships? Multiple embedded dilemmas apply. Here are three:

1. Limiting violence in areas with sharp social cleavages, such as inter-ethnic acrimony, when powerful actors benefit from continued conflict. A common dilemma in transitional times. Consider the post-1990 emergence of civil war in the former Yugoslavia. President Marshall Tito, who died in 1980, had successfully suppressed ethnic rivalry between Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks, and ethnic Albanians.Footnote 1 Subsequently, with prompting by opportunistic regional leaders – notably Slobodan Milosevic in Serbia and Franjo Tudjman in Croatia – inter-ethnic violence emerged and escalated into civil war. Reflecting the conformity-inducing influence of such charismatic divisive leaders, a young Croatian man offered the following comment on his choice between violence and ostracization by his community: “I really don’t hate Muslims – but because of the situation I want to kill them all.” (Bardhan, Reference Bardhan2005, 187, citing Block, Reference Block1993, 10.) How then might multiethnic societies encourage ethnic autonomy and recognition without provoking undue social cleavage?

2. Limiting developmental impasses imposed by systemic corruption without undermining stability. Competing elites – patrons – distribute rents to various clients, in return for political support. Political leaders use rents to attain political support and maintain stability (Haber et al., 2003). Such exchanges become an informal foundation of persistent asymmetric power relationships that spawn entrenched reliance on short-term distributions of benefits – rather than investments in long-term development (Khan, Reference Khan2010; Bebbington et al. Reference Bebbington, Abdulai, Bebbington, Hinfelaar and Sanborn2018; Bardhan and Mookerjee, Reference Bardhan and Mookherjee2018). Furthermore, patronage-based distributions often underlie relative social peace by coopting potential adversaries. For example, in 1870–1910 Mexico, the corrupt Diaz dictatorship ended decades of civil violence that followed Mexico’s struggle for independence from Spain, achieved in 1821. Similarly, after 1920, the systemic corruption of Mexico’s dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party (the PRI) largely quelled the decade-long violence of the Mexican Revolution (la Guerra Civil Mexicana).

Moreover, after studying 18 “pockets of effectiveness” in five countries, Hickey and Sen (Reference Hickey and Sen2024, 4) state: “organizational effectiveness required a mix of political loyalty and bureaucratic competence rather than the displacement of patronage by pure forms of meritocracy.” Often, the social provision of benefits relies on patron-client politics as well as formal democracy (Carbone, Reference Carbone2009).

A related dilemma: How to achieve political-economic liberalization without fostering oligarchy and corruption. Divesting state assets creates uncertainty regarding their value. Transfers of wealth to oligarchs often follow, as in Russia. Liberalizing product markets often enhances the value of land and natural resources, opening opportunities for capturing rents. Practicing competitive populism, political elites can distribute private or club goods in return for support. In “India – corruption is perceived to have gone up in recent post-reform decades.” (Bardhan, Reference Bardhan2018, 116).

3. Managing contestable resources to achieve stable, inclusive, and productive utilization. Point-source resources, such as gold, minerals, and oil, or lucrative exportable agricultural commodities, such as sugar, cotton, tobacco, and opioids, often facilitate a resource curse. Domestic and transnational producers extract rents, dominate politics via clientelist distributions, and truncate economic development. The presence of subsoil resources “defines the terrain on which settlements are constituted, negotiated, and contested.” (Bebbington 223). Developmental challenges include diversifying the economy, fostering long-term investment, structural transformation, and achieving a more equitable distribution.Footnote 2

For over a century, Zambia’s copper-belt elites have dominated politics. The population has not shared the benefits of this extensive resource. Moreover, few alternative sources of income exist in industry, and the agricultural sector lacks dynamism. Fluctuations in international copper prices have compounded developmental obstacles. (Levy Reference Levy, North, Wallis, Webb and Weingast2013; Bebbington et al., Reference Bebbington, Abdulai, Bebbington, Hinfelaar and Sanborn2018).

Peru’s endowments of oil, copper, silver, zinc, lead, and gold – over 50 percent of its exports – have facilitated a more limited resource curse. Export dependence has left Peru vulnerable to transnational political influence and international price fluctuations. Between 1968 and 1980, attempting to unwind such dependence, Peru’s left-wing military government nationalized mines and pursued agrarian reform. Violence, hyperinflation, and isolation from the global financial system undermined the regime. The locus of foreign influence shifted from US mining companies to international creditors (Bebbington et al., Reference Bebbington, Abdulai, Bebbington, Hinfelaar and Sanborn2018). Yet, after 1990, government technocrats reduced inflation and foreign debt. Between 2004 and 2014, annual GDP grew at 6.4 percent, and the government distributed benefits. Poverty fell from 60 percent to 33 percent. After 2014, however, annual growth slowed to 2.3 percent, due to “institutional deterioration, a less favorable external economic context …, the effects of COVID-19, and marked political instability since 2018” (World Bank).Footnote 3

A resource curse, however, is not inevitable. In negotiations with international oil firms, Uganda insisted that extracted oil first go to domestic refineries rather than immediate export. Uganda achieved 38–50 percent share of oil profits and insulated oil technocrats from political influence (Hickey and Sen, Reference Hickey and Sen2024).

Dilemmas 1–3 often work in tandem. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC; formerly Zaire), extensive mining and oil resources presented a “curse” infused with deep corruption and intense ethnic violence. The conflict involves the government, rebels, and troops sponsored by Rwanda.Footnote 4

How then might developing countries limit disruptive, often violent, social cleavage, unravel systemic corruption, and curb the political influence of extractive elites? How might they achieve inclusive distribution with productive utilization of mineral and human resources that support broader investment and structural transformation?

Alas, achieving inclusive development entails resolving complex collective-action problems of forging cooperation among agents with disparate interests, capabilities, norms, identities, and policy ideas. Resolution, moreover, depends on functional configurations of informal and formal institutions, with supportive constituencies. Yet, powerful actors, pursuing their own political-economic agendas, shape institutional evolution in their favor – because they can. Distributions of power thus shape the emergence and functioning of institutions and, by extension, developmental trajectories that condition prospects for functional policy and reform.

A systematic approach to power theory, as it relates to agency, collective action, and institutional evolution thus offers a lens for critical inquiry into the roots and consequences of developmental dilemmas, as well as a theoretical foundation for policy analysis. Accordingly, this Element outlines a conceptual framework for analyzing how developmental dilemmas that emerge from context-specific distributions of power, malleable understandings, and associated CAPs undermine prospects for inclusive development. Functional development policy depends on understanding these principles.

Readers may approach this text from several angles. Those less interested in mathematical representation can grasp the principles without focusing on models and equations. Those more interested in modeling can find more detailed, yet approachable, game-theoretic models in several on-line appendices. Intended audiences include advanced undergraduates in economics and political science; graduate students in applied masters, master’s, MSc, or Ph.D. programs related to political economy, development, and policy analysis. Post-doctoral researchers, policy analysts at think tanks, NGOs, and government agencies, and established scholars in these fields may also find my systematic integrative approach useful.

1.1 Related Literature

Existing development and political economy literature points to important relationships and mechanisms, but it often fails to offer sufficiently comprehensive analysis. For example, the principal-agent literature addresses implications of asymmetric information, yielding insight into economic and political interactions, including labor-management, supplier-producer, and citizen-government. Even so, it focuses too narrowly on bilateral relationships and abstracts from the varied influences of social norms, group identities, and complex power relationships involving third parties.

In contrast, this Element synthesizes diverse components of often-separate literatures. It builds on overlapping approaches to the political economy of power, institutions, and development that appear in six related literatures:

1. Collective Action Theory: Following paths developed by Mancur Olson (Reference Olson1965) and Elinor Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1990), this Element poses collective-action problems as a critical obstacle to functional development. “What is missing from the policy analyst’s tool kit – and from the set of accepted, well-developed theories of human organization – is an adequately specified theory of collective action whereby a group of principals can organize themselves voluntarily to retain the residuals of their own effort” (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990, 22).

2. New institutionalism (e.g., North, Reference North1990; Greif, Reference Greif2006; Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012): a rational-choice approach, with a historical perspective, that addresses institutions as “the rules of the game in society.” Institutions shape incentives, preferences, information flows, and common understandings of social environments. The underappreciated and too often ignored cognitive thread of institutional influence implies an interactive connection between incentives and shared understandings – or, equivalently, interests and ideas. Configurations of informal and formal institutions thus condition interactions among individuals and organizations and so underlie developmental obstacles and potential.

3. The foundational role of informal institutions (e.g., Elster, Reference Elster1989; North, Reference North1990; Basu, Reference Basu2000). Social norms constitute important elements of social equilibria that mediate the effectiveness and functionality of formal institutions and policies. Laws and formal rules that do not point to social equilibria are not institutions; they are just words on paper (Basu, Reference Basu2000).

4. Social conflict theory of institutions (Knight, Reference Knight1992; Bowles, Reference Bowles2004; Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2005; Hall and Thelen, Reference Hall and Thelen2009; Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney and Thelen2009; Tilly and Tarrow, Reference Tilly and Tarrow2015). Incorporating both history and current interactions, this approach posits an ecology of conflict among distinct strategic agents. Organizations and individuals employ coordinated efforts to advance distinct claims that affect others’ interests. Underlying beliefs and distributions of power shape the emergence and demise of powerful coalitions that influence institutional trajectories. Agents test the limits of cooperative agreements and processes of mobilization that bring other actors in line with those agreements’ (Hall and Thelen, Reference Hall and Thelen2009, 13). Institutions thus “represent relatively durable yet continuously contested settlements based on specific coalitional dynamics” (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney and Thelen2009, 8). Within such dynamics, the impetus for institutional innovation arises from grievances over distribution and participation. Methods of innovation, however, evolve from reinforcing adaptive feedback as rules and patterns become increasingly established. At given points in time, institutional configurations emerge from pre-games. Pre-games establish rules of subsequent games, which then condition interactions and ensuing political-economic outcomes (Aoki, Reference Aoki2001). Institutions thus arise and operate as both outcomes of power relations and as sources of power that shape incentives, understandings, behavior, and political-economic development.

5. Political settlement analysis (PSA: e.g., Di John and Putzel, Reference Di John and Putzel2009; Khan, Reference Khan2010; Kelsall et al., Reference Kelsall, Schulz, Ferguson, Hickey and Levy2022). PSA extends and formalizes institutional conflict theory. This approach facilitates analyzing the foundational role of distributions of power in shaping the emergence and operation of institutions, with corresponding impact on distribution, information flows, agents’ motivations, and understandings of social context. A political settlement is “an ongoing agreement among a society’s most powerful groups over a set of political and economic institutions expected to generate for them a minimally acceptable level of benefits, which thereby ends or prevents generalized civil war and/or political and economic disorder” (Kelsall et al., Reference Kelsall, Schulz, Ferguson, Hickey and Levy2022). In this approach, a typology of settlements combines two spectra:Footnote 5

i. The social foundation, meaning the groups that possess sufficient disruptive power to merit inclusion in the settlement: insiders. The social foundation ranges from relatively broad (many groups) to narrow (a few exclusive groups).

ii. The configuration of power among insiders ranges from coherent (or unipolar) to incoherent (or multipolar). A coherent configuration of power implies resolution of basic organizational CAPs regarding how to allocate authority, with corresponding (rough) agreement on major issues, such as relationships between the state and the market or the state and religion. An incoherent configuration implies no such coherence, with a corresponding need to continuously renegotiate initiatives and policies.

6. Interests, Ideas, and political entrepreneurs (Mukand and Rodrik, Reference Mukand and Rodrick2018; Ash et al., Reference Ash and Rodrik2024): This supply-side approach to politics addresses the joint influence of ideas and interests on politics, merging often separately discussed topics. Ideas influence perceptions of interests. Interests provide incentives to acquire, hold, and propagate ideas. Ideas are “hooks on which politicians hang their objectives and further their interests” (Shepsle and Noll, Reference Shepsle, Noll and Noll1985). Ideational politics combines ideas and interests, using an evolutionary dynamic. Political entrepreneurs introduce memes.Footnote 7 Memes are narratives, symbols, and actions that operate like evolutionary genes (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins1976). Their propagation responds to social selection by voters, interests, and policymakers. Ideas that appear to foster successful outcomes spread. Others fail. There are two types of ideational politics: Worldview politics focuses on political-economic understandings of interests. Identity politics focuses on norms and concepts of group identity, with corresponding ideas of inclusion and exclusion. Political-economy dynamics thus reflect combined and evolving influences of interests, worldview, and identity politics. Shifting degrees of meme acceptance and rejection signal understandings of interests, obligations, and group identities that condition prospects for cooperation and conflict in political-economic development.

My approach merges and extends perspectives from these six literatures. I incorporate a rational choice/historical take on collective action (#1) with institutions as rules of the game (#2); reflecting the influences of norms on social equilibria (#3); all conditioned by social conflict theory of institutions (#4). I add political settlements analysis (#5) and dynamic feedback between interests and ideational politics (#6). Additionally, utilizing a boundedly rational approach, I incorporate cognitive and behavioral relations between social norms and social identities, along with four specific types of agency: leadership, following, brokerage, and institutional entrepreneurship.Footnote 8 I address these relations with a systematic approach to conceptualizing power.

Finally, I incorporate complementary influences from two sets of authors:

Set 1: Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson (with or without Simon Johnson; hereafter, A &R) offer three pertinent arguments.

1. Institutions, growth, and power (AJR, Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2005): Institutions structure incentives that underlie long-run growth. Distributions of power, arising from three sources – resource access, institutionally designated positions, and resolved collective-action problems – shape the formation and longevity of political and economic institutions. Ensuing political positions and economic outcomes confer power in the next period, which shapes subsequent trajectories: feedback. Furthermore, absent institutional constraint, powerful actors cannot credibly commit to refraining from using their power for their own future advantage.Footnote 9 Thus, functional development entails achieving credible commitments to limit exercises of power – or, as I will elaborate, resolving second-order CAPs.

2. Extractive vs. Inclusive institutions (A&R, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012). This work contrasts the developmental implications of extractive – exploitative and hierarchical – institutions as opposed to inclusive institutions. Initial conditions, such as resource geography and distributions of power during periods of early colonization, generate critical junctures that indicate two path-dependent longue-durée trajectories:Footnote 10

i. Narrow elite coalitions establish extractive institutions that truncate development

ii. Broader coalitions foster (relatively) inclusive institutions and growth.

3. A narrow pathway to development (A&R, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2018). This work focuses on the inherent conflict between a Leviathan state, which seeks despotic hegemony, and civil society, which seeks to “control and shackle” the state – a collective-action problem. Fruitful development emerges along a “narrow corridor” reflecting a delicate balance of these forces. Herein, competing coalitions make investments in power, with increasing returns, generating three possible steady states:

I. Strong society/weak state: restrictive norms produce a “cage” of informal governance by social elites that inhibits innovation.

II. Strong state/weak society: a despotic state restricts freedom of thought and action, inhibiting economic progress.

III. Shackled Leviathan: Within a narrow corridor, civil society limits state power without destroying it, and limited state power curbs “cage” excesses. Liberty and economic growth follow.

I incorporate and revise components of A&R’s three arguments. I adopt the 2005 approach to power, institutional evolution, and credibility, but with far greater attention to power’s third source: resolution of collective-action problems. I consider their 2012 extractive and inclusive institutions as an opening take on institutional configurations, but I offer more categories and relations, with attention to underlying distributions of power – notably the more nuanced approach of political settlements analysis.

Regarding A&R Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2018, I find the narrow corridor’s delicate balance and role for coalitions instructive. I appreciate their assertion that a normative “cage” restricts opportunity and development – a useful counter to over-glorifying civil society. Nevertheless, as Avanish Dixit recommends, scholars should extend and modify A&R’s approach to address “fissures within each of their two players … and coalitions across subgroups,” along with roles for culture, identity, ideology, and non-rational actors (2021, 24). My framework’s mix of power, bounded rationality, informal and formal institutions, and social identities – with distinct types of agency – offers a conceptual foundation for addressing Dixit’s concerns.

Set 2: Scholars related to the (former) Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre of the Global Development Institute at the University of Manchester. These scholars, including Bebbington, Behuria, Hickey, Kelsall, Leftwich, Levy, Pritchett, Schultz, Sen, Werker, Whitfield, and vom Hau, extend the political-settlement approaches of Khan (Reference Khan2010) and Di John and Putzel (Reference Di John and Putzel2009).Footnote 11 Hickey and Sen (Reference Hickey and Sen2024) summarize and augment these contributions, emphasizing five areas:

A social configuration of power–that is, the social foundations of political settlements (Kelsall et al., Reference Kelsall, Schulz, Ferguson, Hickey and Levy2022).

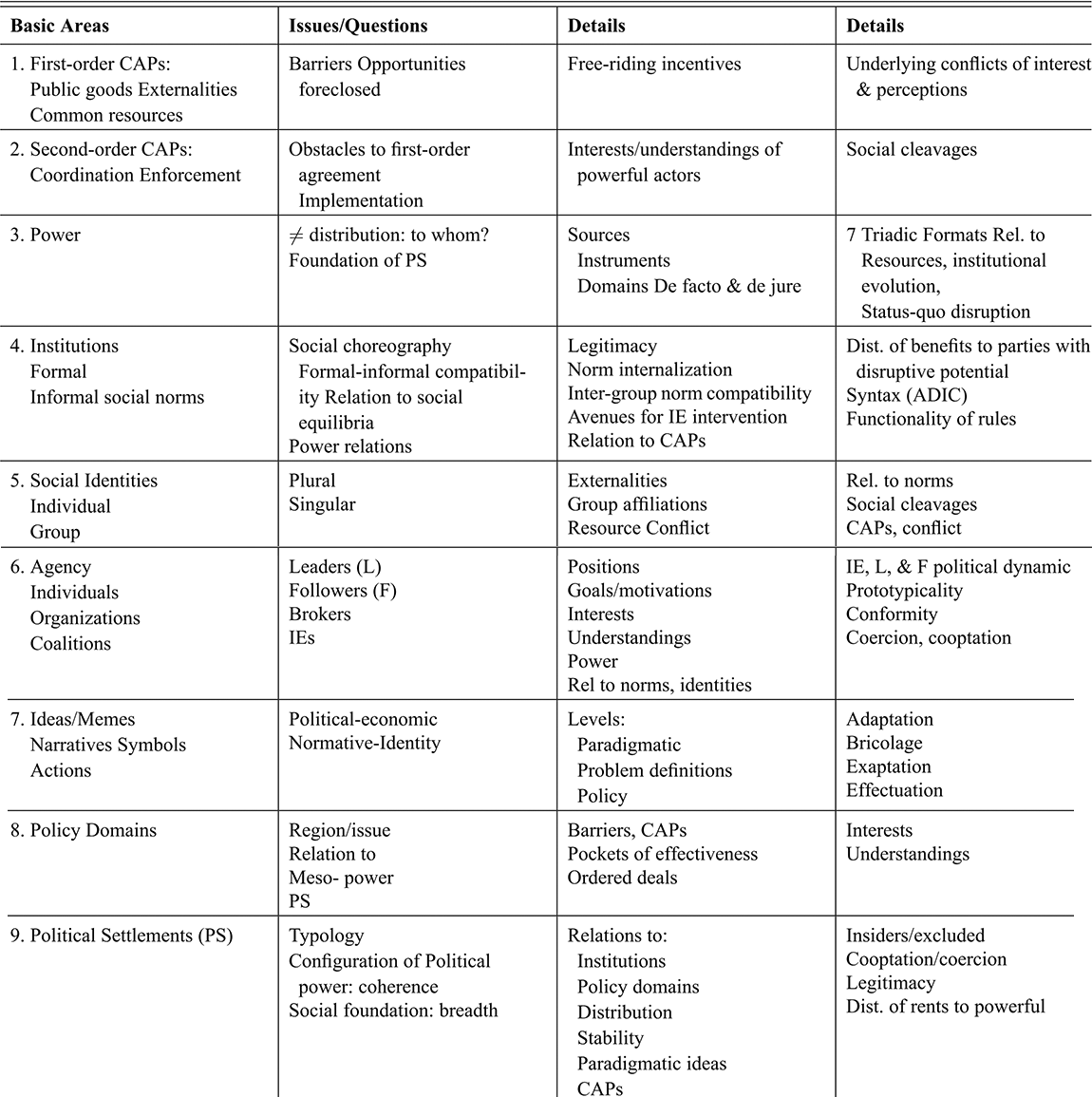

Three sets of ideas: paradigmatic/philosophy; problem definitions; and policy ideas/solutions – noting their normative and cognitive elements.

Policy domains: how distinct policy problems (e.g., service provision, resource management) operate within different meso-level regions and distributions of power, as well as macro-level interactions between policy domains and political settlements.

Pockets of effectiveness: domains of local success in regions with substantial developmental dilemmas.

Ordered deals: informal, yet credible, exchange agreements.

These authors bridge two conceptual gaps:

i. That between a long-durée history based on critical junctures and contemporary institutional configurations. Political settlements tend to persist over medium-term time horizons, and they are subject to sometimes dramatic shifts (punctuation of equilibria).

ii. That between macro-and meso-level analysis. Political settlements operate largely at a macro level. Policy domains operate at meso-levels based on regions and policy areas.

I largely utilize their approach, with greater emphasis on detailed power theory, types of agency, collective-action problems, and game-theoretic reasoning, but fewer specifics on policy domains, pockets of effectiveness, and ordered deals.Footnote 12

1.2 Related Debates and My Approach

My integrated approach sheds light on several related debates, without taking a “side.” I pursue a middle ground that depends on the social context. A few such debates:

1. The relative roles of the state and market in economic development. They are inextricably linked, even in “liberal” economic settings.

2. The political-economic importance of non-state actors. I highlight roles for unofficial agents who influence the legitimacy of formal institutions and corresponding abilities of formal actors to implement policy.Footnote 13

3. Material interests vs. ideas. They are complementary. Informal and formal institutions establish cognitive frameworks that condition understandings of interests. Institutional entrepreneurs propagate narratives, symbols, and actions that influence understandings of political-economic interests, norms, and social identities. Combinations of ideas and perceived interests motivate strategic responses.

4. Structure and agency: To what degree do institutional structures shape agents’ understandings and actions, and to what extent do agents – individuals or organized groups – shape the emergence and evolution of structures? Evolutionary feedback combines both.

5. A “top-down” as opposed to “bottom-up” approach to policy analysis. Both operate simultaneously. Institutional entrepreneurs work at both levels. The feasibility of either depends on social context.Footnote 14

To address these issues, this Element relies on four underlying concepts.

First, following Amartya Sen (2001), I define development as the sustainable, broad-based enhancement of human capabilities and achievements. Capabilities provide sets of feasible alternatives for the realization of human agency. Developmental achievements include the following: growth, equity, education, health care, infrastructure, government capacity, rule-of-law, accountability, and broad political and economic access.

Second, Collective-action problems (CAPs) arise when individuals or organizations, following their interests and inclinations, generate undesirable outcomes for larger groups. Examples include pollution, crime, war, corruption, and climate change. There are two basic types. First-order CAPs concern variations of free-riding with respect to providing public goods, addressing externalities, and/or limiting uses of common resources – all broadly defined to include economic, political, and social interactions. Social peace is a public good. Excess conflict generates negative externalities. Within organizations, managerial time is a common resource. Resolving first-order CAPs entails negotiating distributions of the costs and benefits of achieving cooperation. Will the participants honor such agreements? Second-order CAPs concern arranging sufficient coordination and enforcement to render first-order agreements credible and thus implementable. Why should parties follow stated commitments, such as contributing to public goods or limiting pollution, when cutting corners costs less? The Kyoto climate accords foundered on this very problem.Footnote 15

The under-utilized concept of second-order CAPs links economic and political reasoning. It provides a conceptual foundation for political economy. Exchange requires credible enforcement of agreements, and enforcement entails exercising power. Second-order CAPs thus underlie developmental dilemmas and policy failures – because distributions of power influence prospects for enforcing agreements. Indeed, if power were not embedded in these dynamics, there would be no need for policy.Footnote 16

Third, I define power as follows: Party A’s power is its ability to influence the incentives facing one or more other parties (B) and/or alter B’s understanding of such incentives – doing so in a manner that tilts B’s activities in directions favorable to A.Footnote 17 Incentives may be material (money, time, goods, services), social (reputation), or political (position).

Fourth, as “rules of the game” institutions are mutually understood behavioral prescriptions that convey expectations of relatively broad adherence.Footnote 18 Institutions may be informal, as in conventions and social norms, or formal, as in regulations and laws.

On these grounds, this Element offers the following core statement: resolving developmental dilemmas entails addressing myriad first- and second-order CAPs. Resolution, across hundreds, thousands, even millions of agents, relies on complex combinations of functional informal and formal institutions. Powerful agents, who derive their positions from prior institutional history as well as recent political contestation, endeavor to shape the operation and evolution of institutions in their favor – because they can. Indeed, institutions affect the material, political, and social outcomes they care about. Compounding CAPs of unequal influence and skewed distribution follow. Dynamic concoctions of power, agency, rules, responses, and understandings of interests, propriety, and identity thus shape and emerge from developmental dilemmas.

Functional developmental policy builds on understanding the principles of power and agency that drive such dilemmas, with attention to specific social contexts. How can we remove developmental barriers without first comprehending them?

This Element’s discussion proceeds as follows.

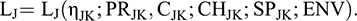

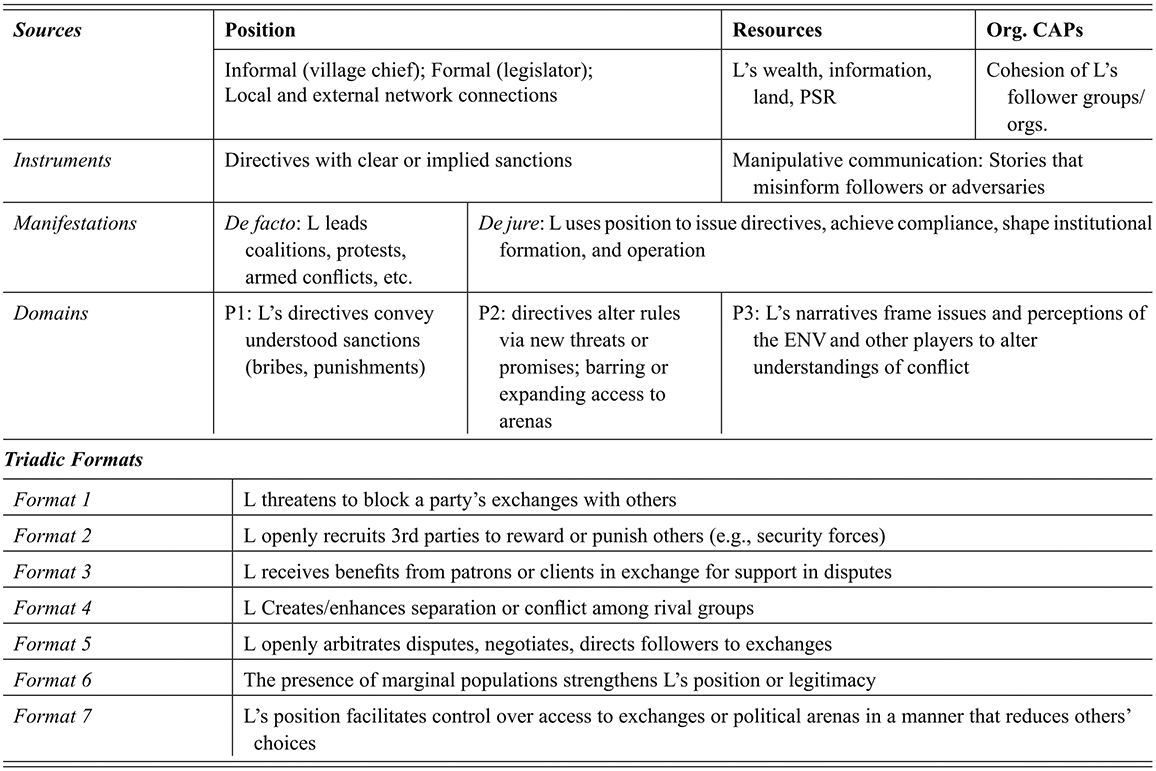

Section 2 outlines a systematic theory of power. It notes power’s sources, instruments, manifestations, and three domains of exercise (or faces; Lukes, Reference Lukes1974). It proceeds to triadic power – that is, power involving at least three poles of interaction or categories of participants, such as labor, management, and finance. A triadic approach facilitates understanding subtle power asymmetries and attendant externalities. Powerful agents exercise triadic power by using seven basic triadic formats (strategic templates), such as divide-and-rule (Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2020, Reference Ferguson2024).

Section 3, after relating structure to agency, focuses on three overlapping types of agency: leadership, following, and brokerage. It notes characteristics, activities, and relations to social context – including distributions of power – along with interactions, such as those between leaders and followers.

Section 4 discusses a fourth, broader type of agency: institutional entrepreneurship, which combines leadership and brokerage within two overlapping modes of operation. Political-economic entrepreneurship strives to change the rules of political-economic engagement, such as the definitions and implications of property rights and rules of participation and associated understandings of interests. Normative-identity entrepreneurship strives to alter interpretations of and/or the evolution of social norms and corresponding concepts of social identity. Internalized norms influence identities, and group identities foster group-specific norms. Norms and identities shape understandings of social environments, including social roles and perceptions of permitted or proscribed behavior. The section concludes by noting that singular, as opposed to pluralistic social identities, generate social cleavages and inter-group conflict.

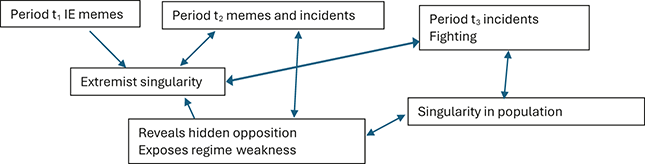

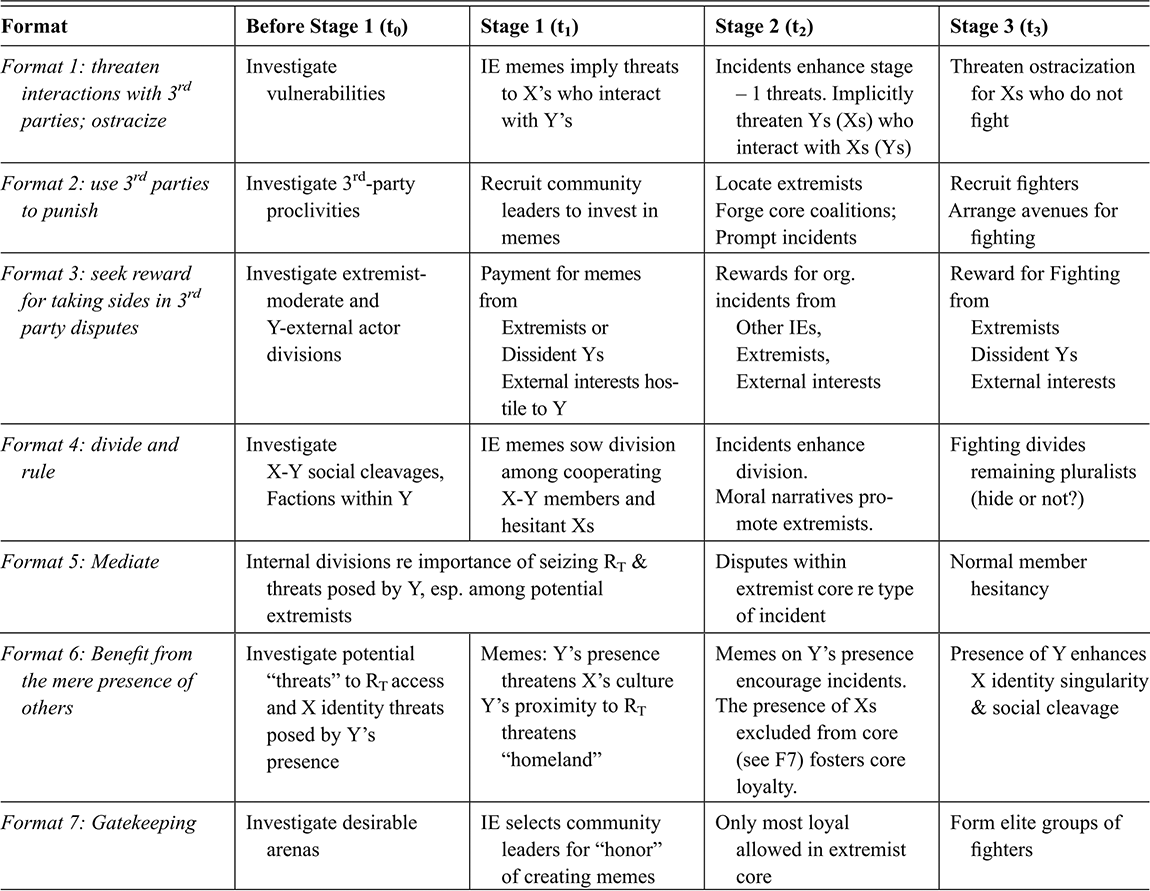

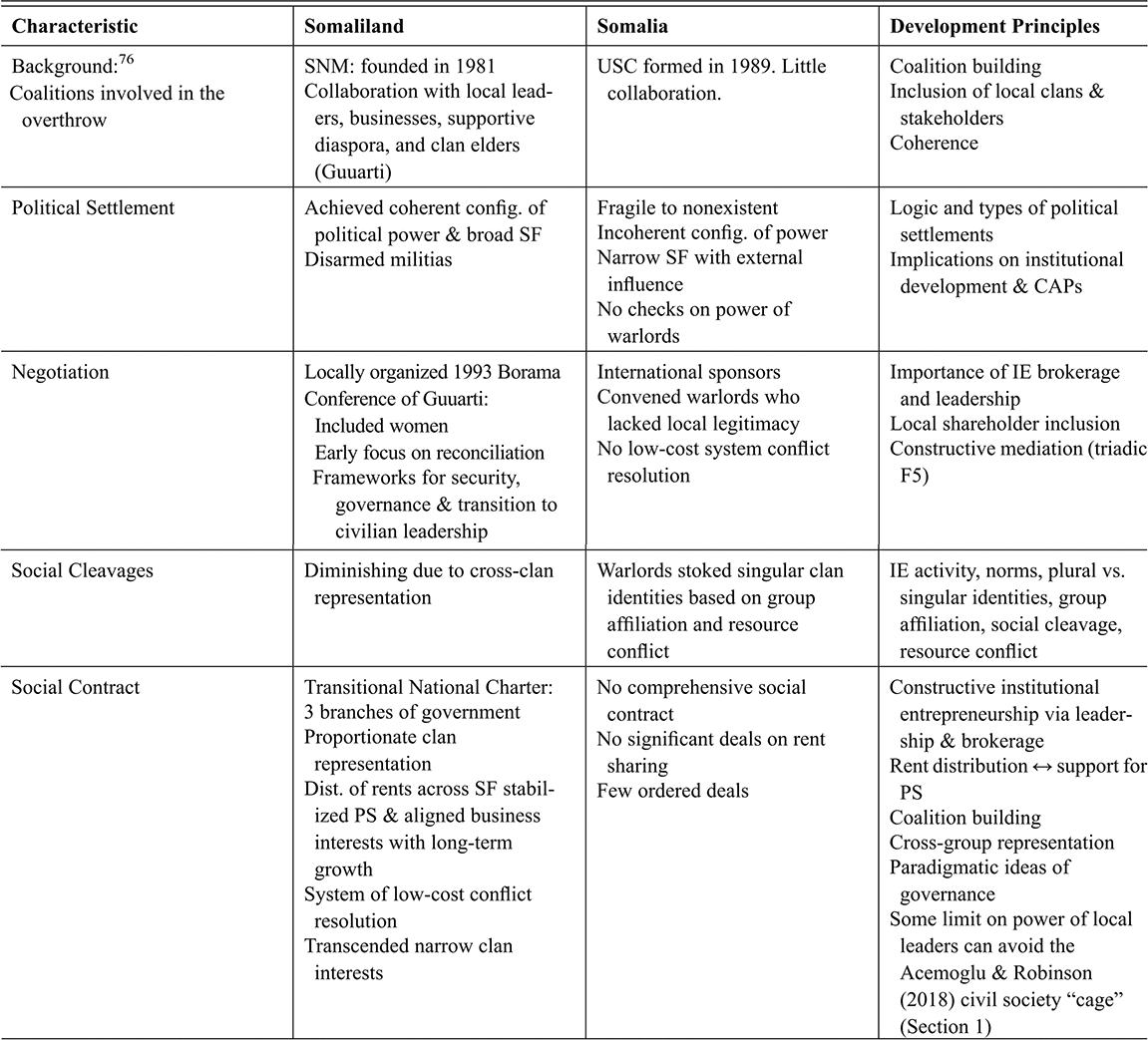

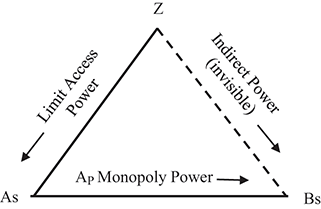

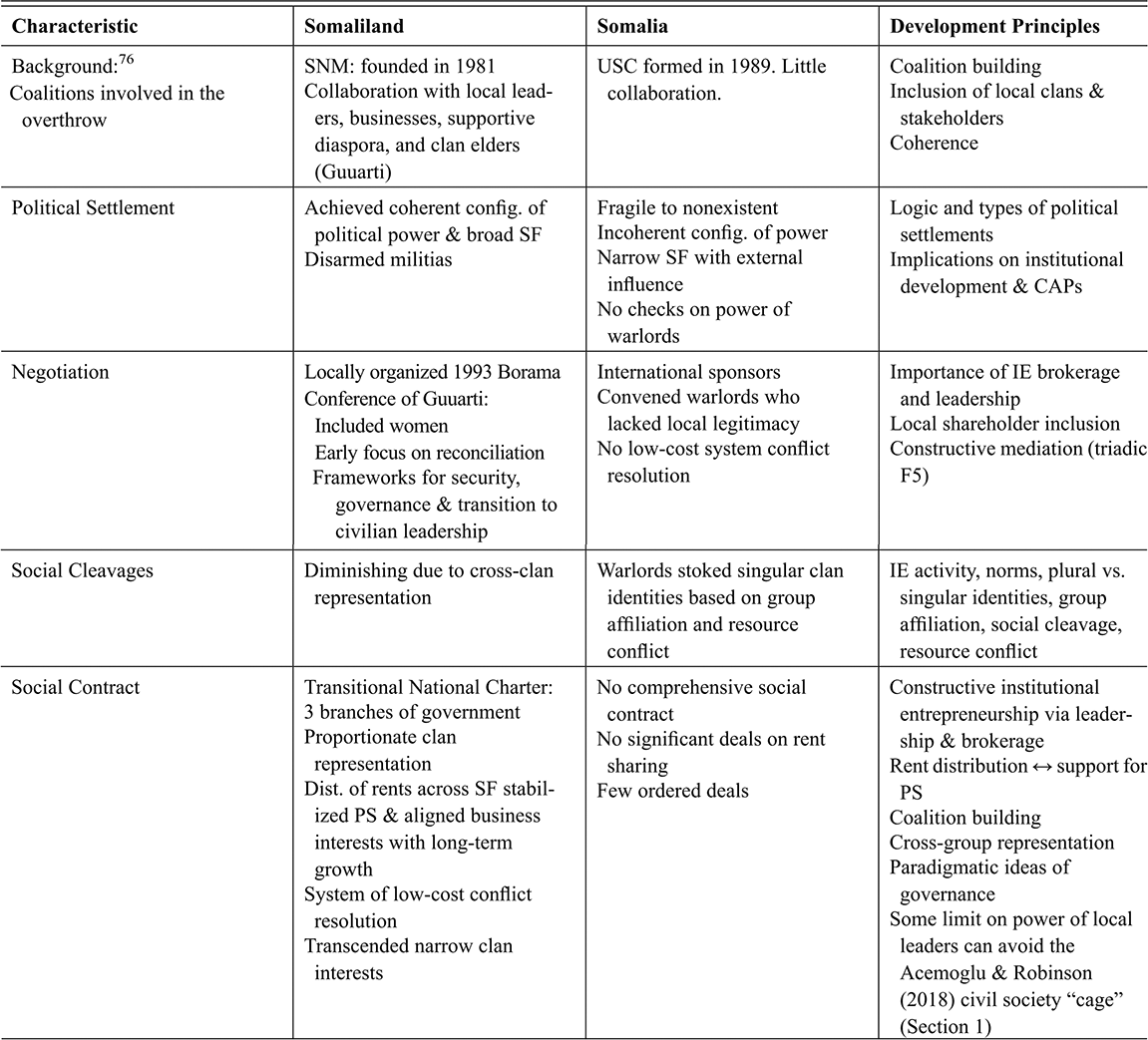

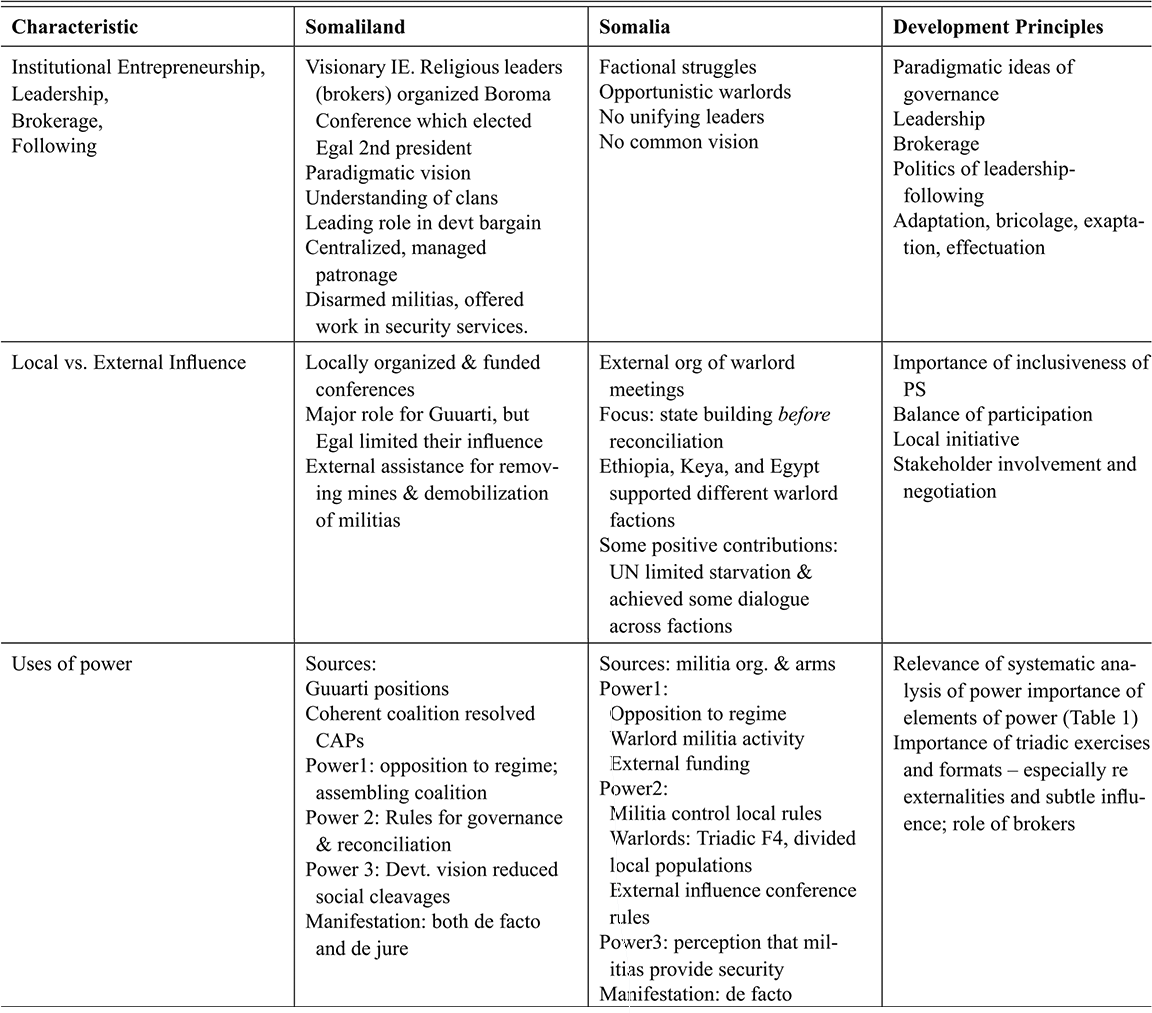

Section 5 opens by considering how institutional entrepreneurs exercise power to promote social cleavage and conflict, using a stylized sequence and model. It follows with a rough script for countermeasures that could improve developmental outcomes. Subsequent discussion contrasts the developmental experiences of Somaliland and Somalia, as an illustration of how this Element’s core principles relate to developmental policy. The conclusion reviews how this systematic approach to power and agency facilitates inquiry into the roots and consequences of developmental dilemmas operating within specific areas and social contexts: a conceptual foundation for developmental policy analysis and inclusive developmental policy.

2 Institutions and Principles of Power

Why would self-interested political and economic elites expend scarce resources to construct the complex institutions required to implement initiatives in areas such as technical education and R and D?

After the Second World War, development in Thailand stalled because fractured elites, already divided over relations to the prior collaborationist government, faced no compelling reasons to unify. They experienced no commonly understood threat to their political survival. Consequently, they encountered little incentive to undertake the difficult steps of establishing coherent administrative, political, and economic institutions. Instead, they relied on short-term distributions of benefits, such as low taxes and cheap electricity, to placate and sow division among local populations (Slater, Reference Slater2010).

Many developing countries, including Malaysia, Thailand, Mexico, Argentina, and Turkey, have encountered a middle-income trap – an extended period over which prevalent standards of living fail to surpass $10,000 (2005 purchasing power parity; Gil and Kharas (Reference Gil and Kharas2015); Spence (Reference Spence2011)). Such economies depend on large informal sectors, wherein ad hoc personalistic identity politics undermines class solidarity, provokes ethnic populism, and discourages investing in human capital. Entrenched political-economic inequality incentivizes and facilitates clientelism and stasis. Ultimately, the “trap” reflects developmental collective-action problems (CAPs). It exhibits political disarticulation based on unequal power combined with a failure to establish cross-coalition collective action that could motivate investments in functional institutions and structural transformation (Rodrik, Reference Rodrik, Allen, Behrman and Birdsall2014).

Resolving developmental dilemmas and associated collective-action problems (CAPs) relies on configurations of informal and formal institutions – and responses of myriad variously placed agents. New CAPs, such as those related to reform, ensue. In all such cases, powerful agents endeavor to tilt the evolution and operation of institutions in directions they believe match their goals – because they can. And others follow. Political elites – that is, agents with disproportionate power and influence on political-economic development – seek political survival (Doner et al., Reference Doner, Ritchie and Slater2005). Elite survival requires building supporting coalitions that may facilitate resolving second-order CAPs of coordination and enforcement. For given levels of influence, elites strive to minimize coalition size to economize on distributing benefits (Riker, Reference Riker1962). Accordingly, the power dynamics of political survival and distribution, as they interact with informal and formal institutions, shape developmental trajectories.

Because distributions of power underlie institutional evolution and developmental prospects, potential beneficiaries of inclusive development face multiple CAPs. Second-order CAPs of establishing credible enforcement undermine the credibility of inclusive contractual, political, and policy arrangements or agreements – and implementation. Crafting credible commitments relies on the workings and often ambiguous viability of multifaceted layers of informal and formal institutions interacting with exercises of power by variously placed agents.

A systematic approach to the elusive concept of power can, therefore, shed light on these developmental dilemmas. Following a brief discussion of institutions, this section develops such an approach. Sections 3 and 4 relate these dynamics to agency.

2.1 Institutions

Recall, institutions are “the rules of the game” in society. They are mutually understood behavioral prescriptions with anticipated observance among relevant groups. As such, institutions accomplish three basic social tasks – all related to exercising and channeling power:Footnote 19

i. Institutions shape motivation by providing incentives and by influencing preferences. A cigarette tax can reduce smoking. Social norms that prescribe fair behavior often alter preferences.

ii. Institutions shape sources and transmissions of information. Who writes and who receives the treasurer’s report?

iii. Institutions shape cognition. Their understood behavioral prescriptions outline shared mental models. Institutions establish common conceptual frameworks that facilitate interpreting social contexts (Denzau and North, Reference Denzau and North1994).Footnote 20 Who can or cannot, should or should not do what, when, and how? A simple norm against cutting in line frames understandings of how to behave when approaching a queue of, say, 100 strangers at an office or theatre. Go to the back, as those arriving before you did.

The motivational, informational, and cognitive sway institutions offer inviting avenues of influence for those able to harness and modify their prescriptions. Powerful agents thus endeavor to slant institutional evolution in directions that favor their agendas and interests, albeit sometimes mistakenly. Accordingly, skewed distributions of power condition multiple contested interactions that influence the viability, reach, and inclusiveness of political and economic institutions – along with political-economic outcomes, such as allotments of opportunity and benefit. Indeed, developmental trajectories follow cycles of disproportionate influence, contestation, and response. Sections 3–5 elaborate. I now outline a systematic approach to conceptualizing power.

2.2 Power

Recall that power is the ability of one party (A; an individual, organization, or functional coalition) to influence the incentives facing one or more others (B) and/or alter their understanding of such incentives – in a manner that affects their activities in directions favorable to A.Footnote 21 Bs include individuals, groups, organizations, coalitions, and populations. The incentives may be material (money, time, goods, and services), social (reputation), or political (attainment of political position).

Power has the following properties (Bowles and Gintis, Reference Bowles, Gintis, Durlauf and Blume2008):

It is social, not individual.

Its exercise constitutes a strategic (Nash) equilibrium. For relevant agents, exercising power or submitting to it is at least as good as perceived feasible alternatives.

Power is normatively indeterminate. It can generate positive-sum gains (Pareto improvement) or exploit victims. Parental exercises of power (e.g., no dessert unless you eat your vegetables) can benefit children. Likewise, when professors grade students, they exert power. This positive vs. zero-sum distinction is important. Zero-sum perceptions of power and interests underlie debilitating social cleavages and inter-group conflict (Levy and Fukuyama, Reference Levy and Fukuyama2010).

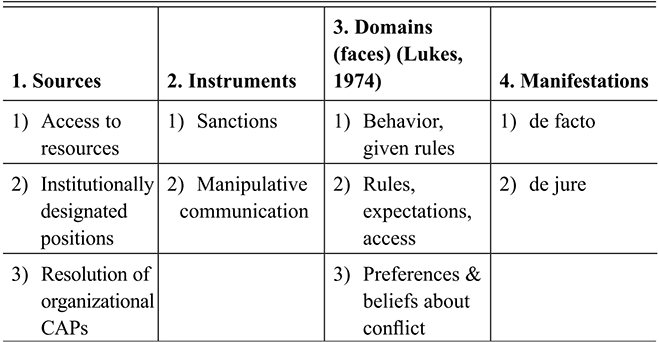

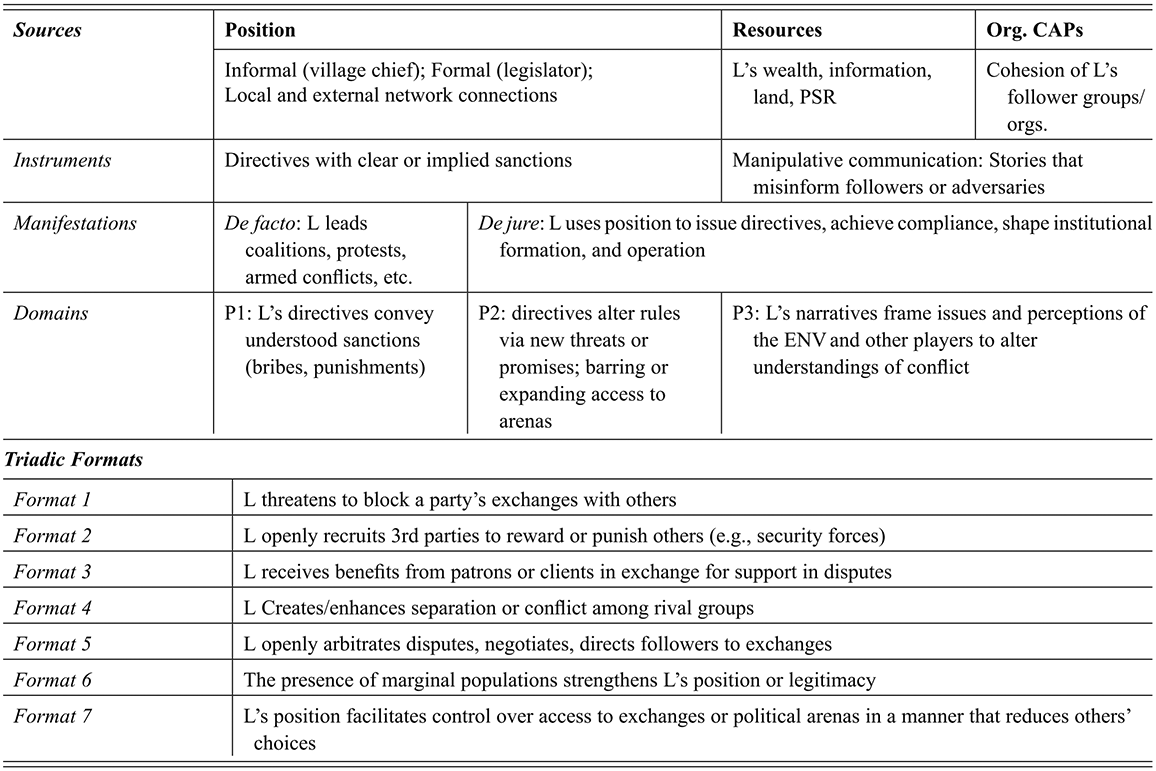

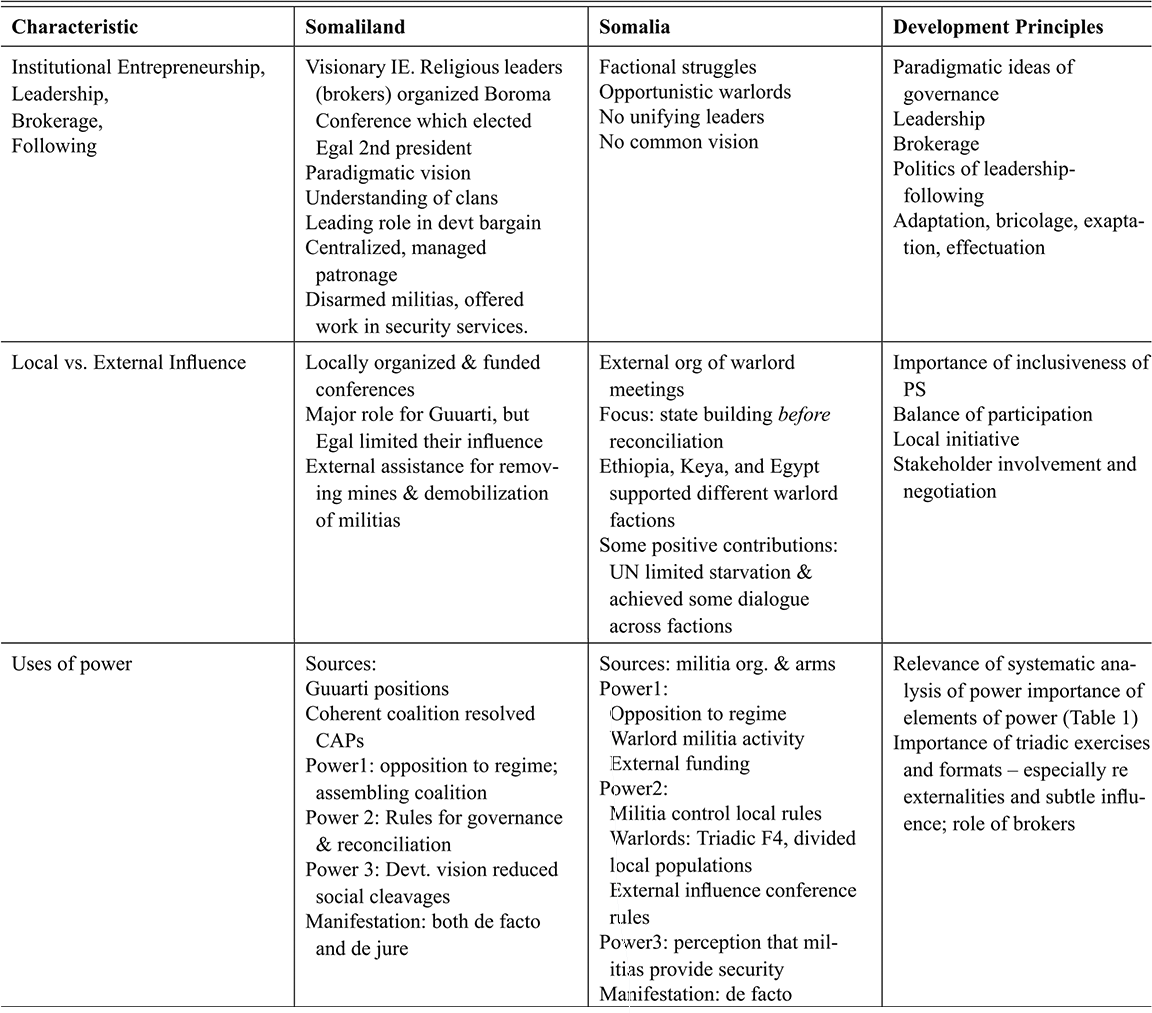

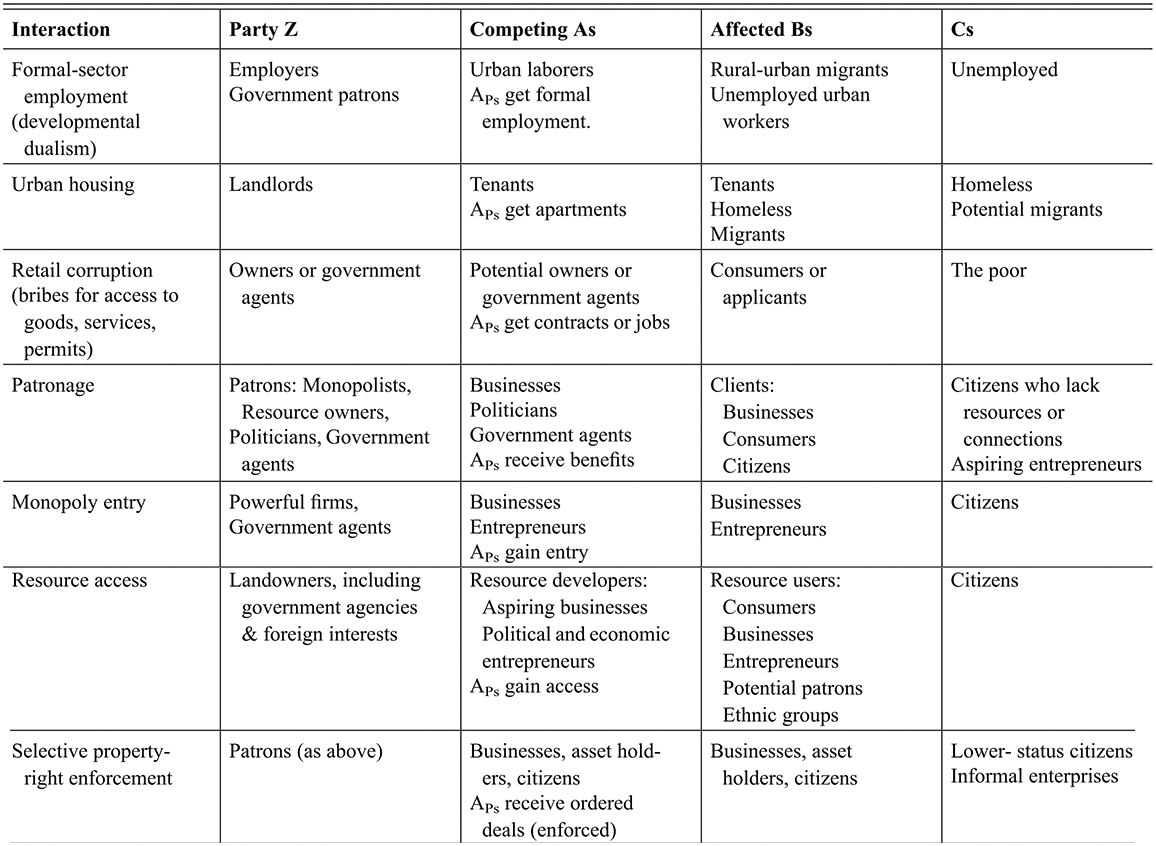

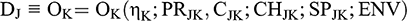

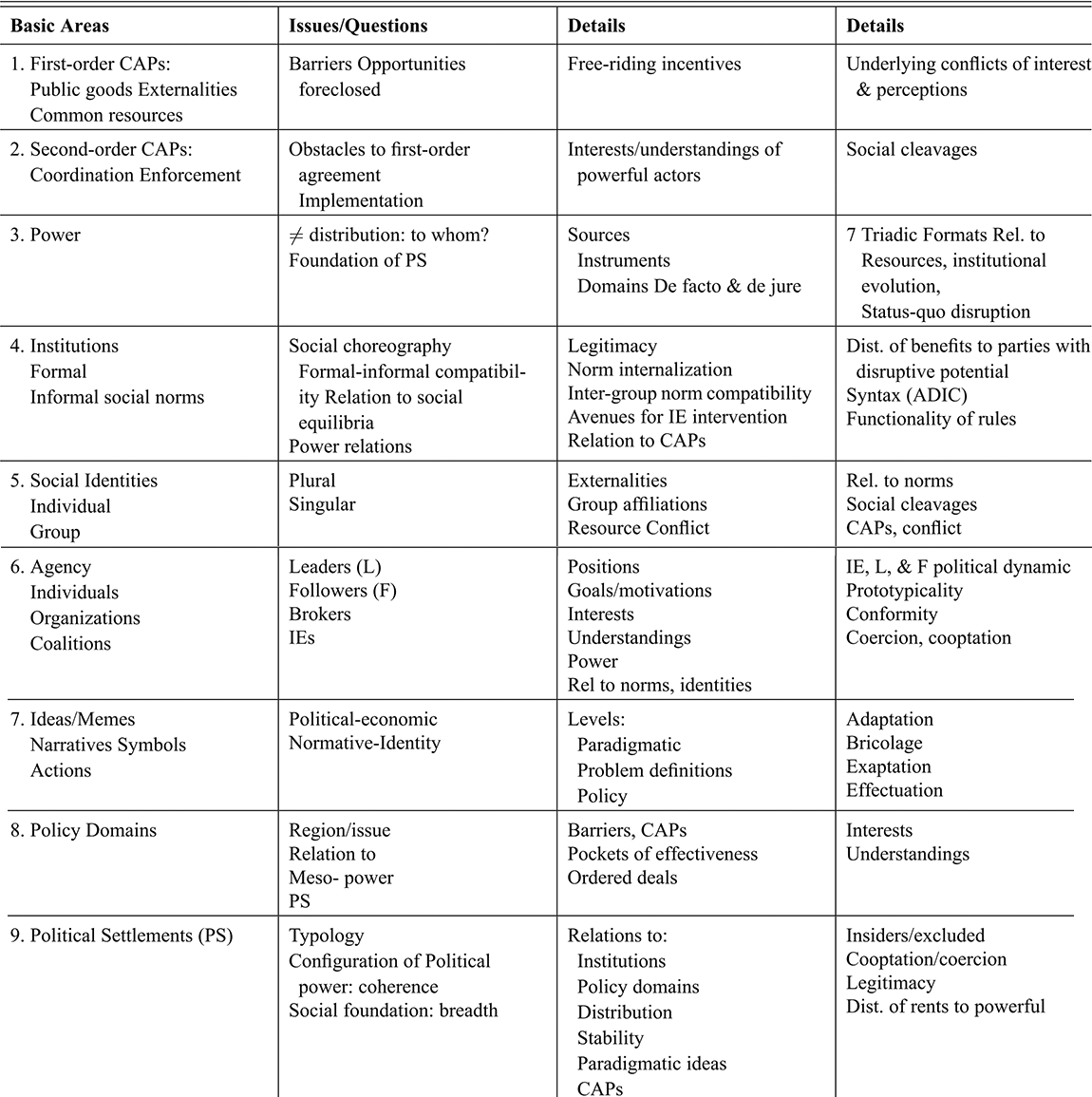

Table 1 outlines four core elements of power relations:

Table 1Long description

Column headings: 1. Sources; 2. Instruments; 3. Domains (faces) (Lukes 1974); 4. Manifestations. Under Sources, the rows list 1) Access to resources; 2) Institutionally designated positions; 3) Resolution of organizational CAPs. Under Instruments, the rows list 1) Sanctions; 2) Manipulative communication. Under Domains (faces), the rows list 1) Behavior, given names; 2) Rules, expectations, access; 3) Preferences & beliefs about conflict. Under Manifestations, the rows list 1) de facto; 2) de jure.

Elaborating on Column 1’s Sources of power:Footnote 22 Resources include money, goods, services, and information. Institutional positions may be informal, as community leaders or village chiefs, or formal, as in chairs of legislative committees or CEOs. Regarding the resolution of organizational CAPs, coherent organizations exert more power than dysfunctional ones.

Regarding Column 2’s Instruments of power: Sanctions may be positive (rewards) or negative (punishments), and either implicit from preexisting context or newly introduced, as in promises and threats. Manipulative communication connotes forms of deception, such as lying.

Regarding Column 3’s Domains of power: Power1 entails assembling force or bargaining strength in a context with given, understood rules. It directly impacts behavior. Examples include the size of already engaged Russian and Ukrainian armies, the size of established voting blocs, or the amounts of money offered in already announced bribes. Power2 alters various rules of engagement and corresponding expectations concerning responses of other parties. Power2 is equivalent to strategic moves in game theory (Schelling, Reference Schelling1960). Examples include issuing unanticipated threats, barring access to meetings, limiting or expanding rights of participation or voting, and altering agendas.Footnote 23 Power3: alters understandings and preferences regarding conflict. Party A may convince B that B wants what A wants; that a person or group in B’s position should never challenge one of A’s position (how dare you!); or that another party (C) is the culprit for B’s problems.

Regarding Column 4’s Manifestations of Power: de facto power signifies immediate on-the-ground power, such as the number of Russian troops facing Ukrainian troops in the Donbas in June 2023 or the number of protesters in Tahrir Square, Cairo, on 21 January 2011. In contrast, de jure power tends to endure, at least over medium-term time horizons. It is institutionalized, based on accepted law, regulations, or established procedures. South Korea’s post-Second World War land reform altered both agricultural production and the distribution of power.

Efforts to reform, reconstruct, create, or abolish institutions utilize powers 2 and 3 with hopes to achieve de facto manifestation by institutionalizing certain behavioral prescriptions. Section 4 addresses the role of institutional entrepreneurs in such endeavors.

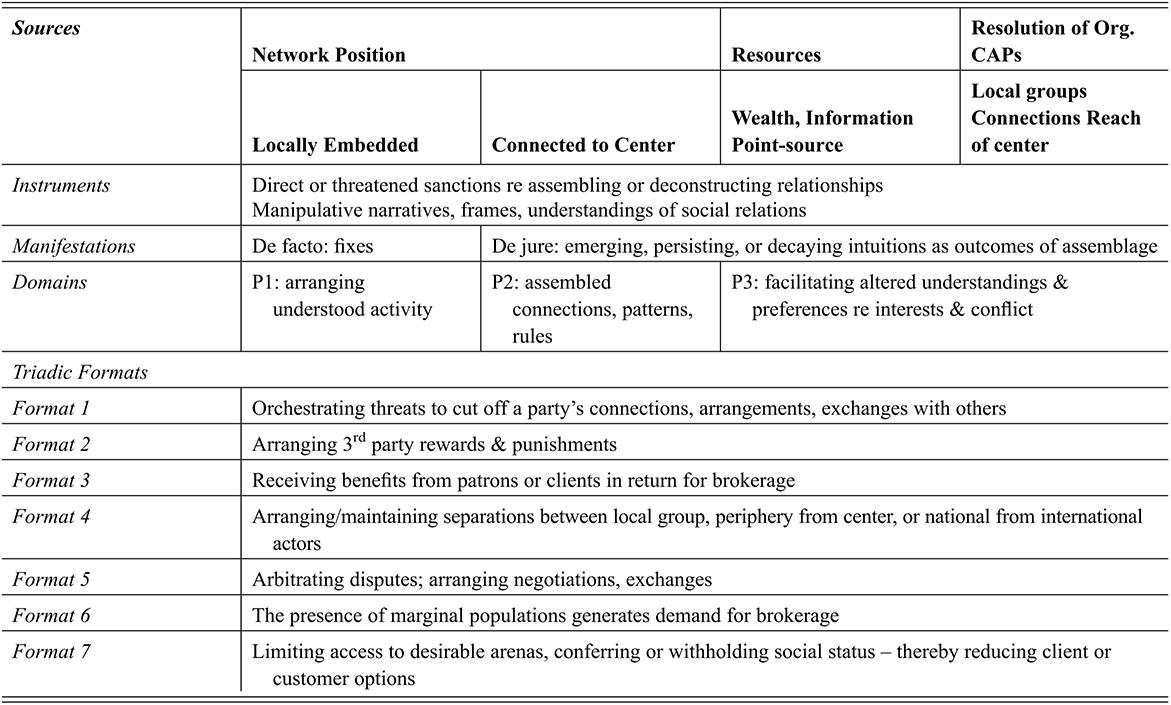

Because power resides in engagements, conceptualizing its exercise requires positing relevant axes or poles of interaction. Traditional approaches assume dyadic relationships. Herein, A’s power influences B and vice versa without involving or affecting other parties (C). Many treatments of union-management bargaining envision dyadic exchanges. While useful, such approaches often understate power asymmetries and ignore subtle relations to third parties.Footnote 24

In contrast, triadic conceptions of power involve at least three poles of interaction – three categories of participants, such as landlord, tenant-laborer, and merchant (Basu, Reference Basu2000). Here, A↔B interactions involve, affect, or respond to the presence of third parties (Cs): power externalities. Dyads thus become bilateral components of triadic relations (A↔B; B↔C, C↔A). Triadic approaches permit the following elements (Simmel, Reference Simmel1902):

Potential majorities

Unclear attribution of responsibility. With incomplete observation, each party could blame the consequences of its actions on another party

Roles for intermediaries: mediators, facilitators, “middlemen”

Strategic manipulation of dyadic relations, whereby A (B or C) influences dyadic interactions B↔C, C↔A, or A↔B.

Exercises of triadic power operate via seven, sometimes overlapping strategic templates or triadic power formats. These are:Footnote 25

F1: Threatening to disrupt interactions between others.

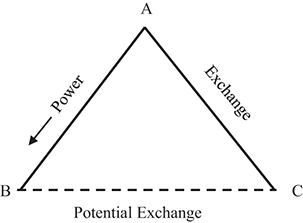

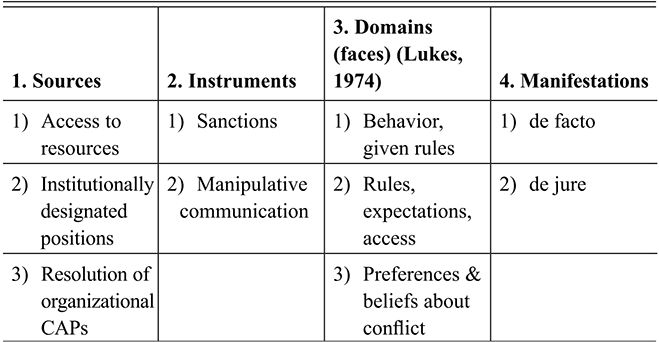

Landlord A threatens to block tenant-laborer B’s exchanges with merchant C unless B accepts a wage below its reservation wage (Basu, Reference Basu2000). Figure 1 illustrates. A thus exploits B, paying less than a minimal non-coerced wage offer. More generally, A may threaten to ostracize B for refusing an offer or directive. For example, community leaders may credibly threaten members with expulsion for violating local norms or commands. This dynamic also operates in areas with a single large employer, such as a mine or factory (“one-company towns”), informal employment relationships, or political coercion.

Following the July 2016 failed coup in Turkey, President Erdoğan’s government fired and blacklisted thousands of civil servants accused of sympathies with the Gülen movement, effectively denying them employment and access to many economic relationships.

F2: Using a 3rd party to punish or reward an adversary.

Dictator A hires security agents (Cs) to punish dissidents (Bs). Politician A hires assistants (Cs) to reward loyalists (Bs).

Vladimir Putin enlisted the Wagner Group to fight in Ukraine and to promote Russian interests in African countries.

F3: Demanding a return for taking sides.

Small party or coalition A demands a powerful post, such as a ministry, in exchange for tipping the balance between larger parties B and C. This dynamic can apply to ethnic or regional conflicts.

South Sudanese prophet Nyachol sided with former South Sudanese vice president Riek Machar and General James Koahg as they fought against President Salva Kirr’s government. In return, Koang gave her cattle “as a sign of his support and allegiance” (Hutchinson and Pendle, 2015, 427).

F4: Divide and rule.

Colonist or dictator A incites ethnic, racial, religious, ideological, or resource conflict between groups B and C to undermine, control, or coerce them.Footnote 26

In northern Uganda, the central government undercuts locally based power by practicing institutional arbitrariness. It promotes local armed security groups, giving them ambiguous responsibility for maintaining order, and it randomly punishes them for undefined excesses. This arbitrary use of violence shifts rules of engagement (power2), “thereby fragmenting resistance and reinforcing its authority” (Tapscott, Reference Tapscott2017, 264).

F5: Mediation.

Party A arbitrates B↔C disputes or negotiations. A’s approach ranges from impartial to biased. Impartial mediation can benefit a larger group (D) by reducing disruptive conflict – a positive-sum outcome. Yet, the greater A’s bias, the more likely it will tilt its mediation to its own advantage, reducing or eliminating positive-sum gains.Footnote 27

In Pakistan’s Panj province, business agents, unions, and civic organizations – acting as intermediaries between political patrons and local populations – engage in isomorphic activism. They not only make themselves indispensable and benefit from access to various services, they also undermine democratic potential as they truncate opportunities and discourage practices of broader participation (Kirk, Reference Kirk2024).

F6: Benefiting from the mere presence of third parties.

Parties A and B engage in an exchange for which uninvolved Cs would replace Bs, given the opportunity. Here, A can use the existence of Cs as leverage in negotiations with Bs. For example, unemployment allows employers to credibly threaten workers with dismissal should they demand higher wages. This dynamic indicates the short-side power conferred by occupying certain positions in contested exchange relations, such as that of employers (Bowles and Gintis, Reference Bowles and Gintis1992).Footnote 28

A similar short-side power dynamic applies to attaining formal employment in settings of developmental dualism with rural-urban migration (Harris and Todaro, Reference Harris and Todaro1970) and to the power of financiers, positioned as creditors (Bowles, Reference Bowles1985; Stiglitz, Reference Stiglitz1987). Likewise, F6, perhaps combined with F3 or F4, can influence political bargaining.

F7: Gatekeeping (Oleinik, Reference Oleinik2016).

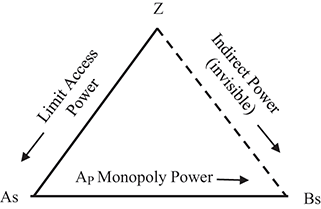

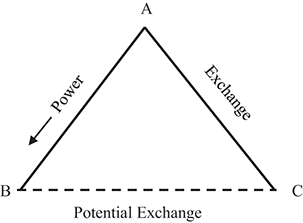

Gatekeeper, Z, limits access to desirable positions within economic, political, or social arenas. Remaining agents fit triadic categories A–C. Qualified agents (As) compete for access, but only some achieve privileged entry (Aps); the remainder (Aus) become either Bs or Cs. Bs, such as consumers, voters, or political clients, desire transactions with As. Cs, lacking sufficient wealth, privilege, connection, or status, cannot transact in the arena. Figure 2 illustrates.

Gatekeeping power enters in three distinct fashions. First, gatekeeper Z directly exerts powers 1 and 2 over the As, as in forcefully blocking entrance into a political-economic arena or altering the rules of access. Second, by limiting the number of Aps, Z truncates Bs’ choice sets among transactions with potentially competing As. This limit alters various rules of exchange: power2. Moreover, such gatekeeping often reflects invisible power: the Bs may not even know of Z’s existence. Third, privileged APs apply F6 short-side power as they interact with Bs, who now face a combination of limited choice sets and the presence of many Cs who would gladly replace them.

The northern Uganda example noted under F4’s divide and rule also exhibits F7 gatekeeping. The Ugandan government (Z) arbitrarily limits access to permitted enforcement activities: randomized gatekeeping. Local security groups (alternately Aps and Aus) thus operate in an unpredictable arena that prevents them from organizing opposition to the government. Local residents, arbitrarily Bs or Cs, face unpredictably limited choices among security arrangements (Tapscott, Reference Tapscott2017).

Figure 1 A format 1 power triad

Figure 2 A format 7 power triad

Figure 2Long description

Segment Z-As is labeled “Limit Access Power”, with an arrow pointing towards As. Segment As-Bs is labeled “Ap, Monopoly Power,” with an arrow pointing towards Bs. Segment Z-B s is a dashed segment labeled “Indirect Power (invisible),” with an arrow also pointing towards Bs.

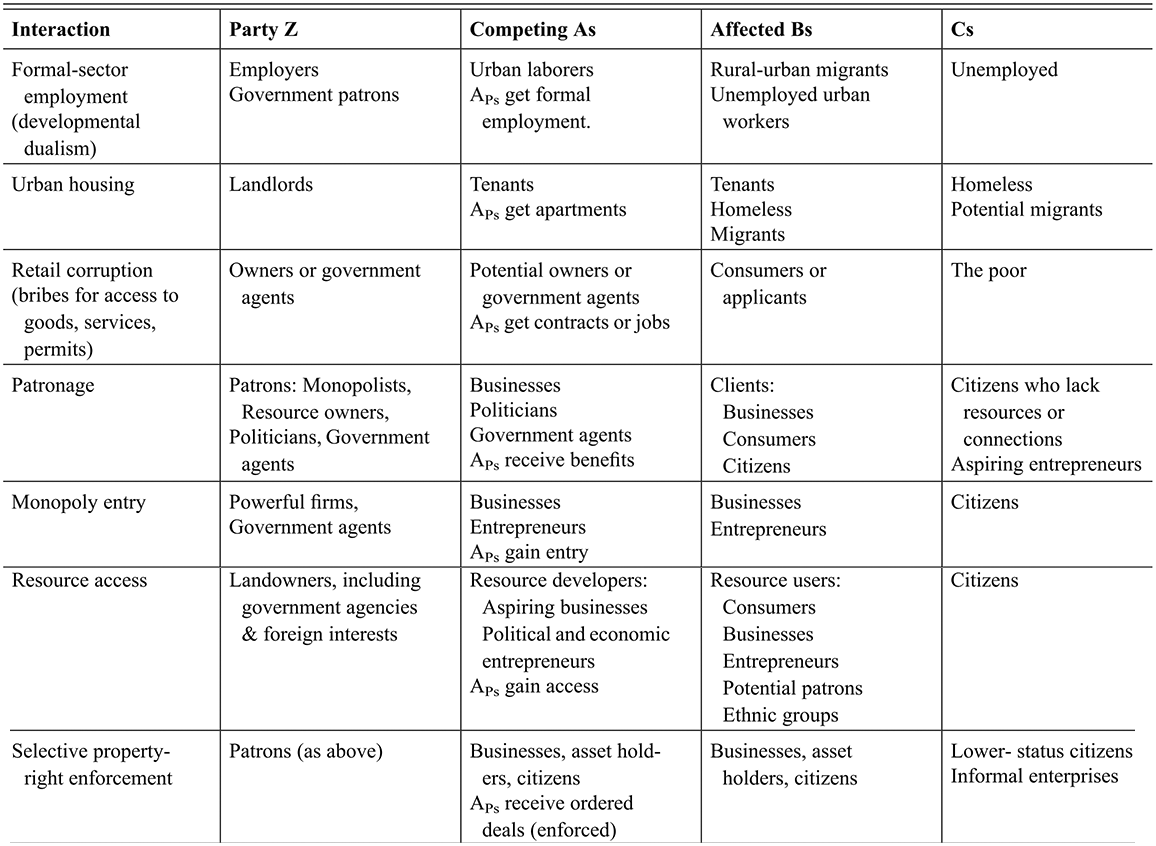

More broadly, gatekeeping applies to multiple developmental relationships. Table 2 lists several.

a These transactions exhibit both positive- and zero-sum properties, depending on the axis of exchange.

Table 2Long description

Column headings: Interaction, Party Z, Competing As, Affected Bs, Cs.

The first interaction: Formal-sector employment (developmental dualism).

Party Z: Employers, government, patrons.

Competing As: Urban laborers, Aps get formal employment.

Affected Bs: Rural-urban migrants, unemployed urban workers.

Cs: Unemployed.

The second interaction: Urban housing.

Party Z: Landlords.

Competing As: Tenants; APS get apartments.

Affected Bs: Tenants, homeless, migrants.

Cs: Homeless, potential migrants.

The third interaction: Retail Corruption (bribes for access to goods, services, permits).

Party Z: Owners or government agents.

Competing As: Potential owners or government agents; APS get contracts or jobs.

Affected Bs: Consumers or applicants.

Cs: The poor.

The fourth interaction: Patronage.

Party Z: Patrons: Monopolists, resource owners, politicians, government agents.

Competing As: Businesses, politicians, government agents; APS receive benefits.

Affected Bs: Clients: Businesses, consumers, citizens.

Cs: Citizens who lack resources or connections, Aspiring entrepreneurs.

The fifth interaction: Monopoly Entry.

Party Z: Powerful firms, government agents.

Competing As: Businesses, entrepreneurs; APS gain entry.

Affected Bs: Businesses, entrepreneurs.

Cs: Citizens.

The sixth interaction: Resource Access.

Party Z: Landowners, including government agencies & foreign interests.

Competing As: Resource developers: Aspiring businesses, political and economic entrepreneurs; APS gain access.

Affected Bs: Resource users: Consumers, businesses, entrepreneurs, potential patrons, ethnic groups.

Cs: Citizens.

The seventh interaction: Selective property-right enforcement.

Party Z: Patrons (as above).

Competing As: Businesses, asset holders, citizens; APS receive ordered deals (enforced).

Affected Bs: Businesses, asset holders, citizens.

Cs: Lower-status citizens, informal enterprises.

The seven formats often overlap and interact. They unfold in various combinations and sequences. For example, interlocked credit and tenancy markets merge agricultural tenancy, sharecropping, and debt-peonage (Stiglitz and Weiss, Reference Stiglitz and Weiss1981). Landholders and merchants restrict access to credit (F7) either by occupying a dual role as financiers or, as in F1, by blocking exchanges with financiers for tenants who fail to accept exploitative remuneration. A combination of low remuneration and external events, such as natural disasters or reduced commodity prices, pushes tenants into debt that must be repaid with labor and produce, indicating bonded labor and debt-peonage. Moreover, the presence of unemployed rural laborers reinforces landholder short-side power (F6). Furthermore, the presence of unemployment may allow landholders, financiers, and formal employers to sow division between the employed and the unemployed or between those with better and worse land or jobs – often exacerbating social cleavages along ethnic, racial, and/or regional lines (F4). Finally, bonded labor and other exploitative arrangements may be enforced by hired managers, police, or local vigilantes (F2).

A related example illustrates long-term developmental consequences. In the post-bellum US South’s system of sharecropping, [the] “merchant forced the farmer into exclusive production of cotton by refusing credit to those who sought to diversify production.” The merchant’s local land monopoly underlay its power to influence political and economic relationships, establishing “the roots of Southern poverty” (Ransom and Sutch Reference Ransom and Sutch2001, 127, 149–199).

These exercises of the seven triadic formats rely on asymmetric access to power’s three sources – resources, institutional positions, and the ability to resolve organizational CAPs. To secure and sustain economic and political advantage, political and business elites utilize power’s instruments of sanctions and manipulative communication – with short-term de facto and longer-term de jure manifestations. They utilize power2 alterations of rules, and power3 reinterpretation of conflict – often exercised via combinations of triadic formats. Such maneuvers establish conditions for concurrent or subsequent direct application of force (power1). Combined exercises of power shape institutional trajectories, developmental dilemmas, associated CAPs, and ultimately, political settlements – by applying agency to structure. Section 3’s topic.

3 Foundations of Structural Change: Three Types of Agency

He who wishes to be obeyed must know how to command.

Niccolo Machiavelli

‘… others mediated between these figures [patrons] and those lower down, bridging these separate worlds while simultaneously deriving benefits from keeping them some distance apart.’

How did South Africans resolve the dilemma of transforming the apartheid system into a multi-racial democracy? They organized opposition. Their escape from apartheid emerged from the combined and evolving influences of many participants, including leadership from Nelson Mandela and Desmund Tutu; militant opposition with broad following; additional leadership, organizing, and brokerage, from the African National Congress (ANC), Confederation of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), and the South African Anglican Church; international sanctions; and F.W. de Klerk’s willingness to negotiate with Mandela. Multidimensional agency overturned structure.

Section 2 established a systematic approach to conceptualizing how powerful agents influence developmental trajectories. Recall, powerful agents may be individuals, organizations, or functional coalitions. Their influence operates within evolving contexts of institutions, common understandings, and patterns of behavior. Well-positioned and resourced elites operating within historically inherited structures pursue political-economic goals using power to exercise agency that can – intentionally or not – transform structure.

This section’s discussion proceeds as follows. Section 1 relates agency to structure. Section 2 addresses cognitive foundations of agency based on bounded rationality and shared mental models. Section 3 discusses three basic types of agency: leadership, following, and brokerage, with attention to basic concepts, activities, and interactions. On this basis, Section 4 will address a hybrid type of agency: institutional entrepreneurship.

3.1 Agency and Structure

Agency is simply the exercise of rationalizable choice concerning intentional action in pursuit of goals (Battilana et al. Reference Battilana, Leca and Boxenbaum2014; Corbett, Reference Corbett2019; Grillitsch and Sotaruta, Reference Grillitich and Sotaratua2020). How do agents perceive, make sense of, or justify their decisions within specific contexts populated with myriad actors, actions, practices, and anticipated responses? They may consider ethical principles and consequences regarding material gain, desired positions, and reputation. Structure refers to the relatively durable contours of contexts within which agents interact, including informal and formal institutions, established habits, and corresponding culturally inherited conceptual frameworks that shape understandings of social and physical environments.

Structure and agency coevolve. Structure establishes both constraints on and opportunities for individual and group activity and thought. Agency shapes the contentious and disjointed evolution of structure via complex shifting, competing, conflicting, and cooperative activities of multiple participants – endowed with different understandings, capabilities, interests, and unequal power (Leftwich, Reference Leftwich2010). Powerful agents exert disproportionate influence. They employ power’s three domains and seven triadic formats in efforts to shape political-economic outcomes and the contested trajectories of institutional change. Yet, outcomes frequently evade intention. Deliberate structural change, as in political-economic reform, thus presents formidable collective-action problems (CAPs).

“Institutions are the rules of the game in a society” (North, Reference North1990, 3). Accordingly, game theory can illustrate the co-evolution of structure and agency as a foundation for understanding the shaping of institutions and developmental consequences. The rules of a game specify who plays, possible actions, the timing of moves, what players know or do not know, all possible outcomes, and the payoffs at each. Payoffs can be material (money, time, goods, services), social (reputation), and political (access to position). Establishing structure constitutes a pre-game whose outcome depends on applications of agency within various deliberate, unintended, and random interactions among agents with different motivations and unequal influence (Aoki, Reference Aoki2001). Pre-games create rules (structure) for subsequent games within which more broadly dispersed and less scripted applications of agency generate proximate outcomes – such as distributions of resources and benefits. Over time, accumulated reactions spawn new pre-games: new structures for future encounters. The process repeats. A mix of unequal exercises of agency based on asymmetric distributions of power and chance thus shapes the creation, sustenance, alteration, and abolition of institutional structures – often with unintended consequences. Developmental dilemmas with varying prospects for resolution follow.

Macro structures condition these dynamics. Here are two conceptualizations. First, institutional systems are interactive combinations of institutions and organizations: institutions as rules; organizations as players. Institutions prescribe behavioral patterns that, when adopted, configure arenas for interaction. Organizations act. Organizations are structured groupings that operate roughly as a unit. They pursue sets of negotiated goals using evolving decision rules to understand and coordinate key operations (Cyert and March, Reference Cyert and March1963). Institutional prescriptions point to resolutions of first-order CAPs by indicating who should contribute how much, and so forth. But, due to second-order CAPs, institutions alone do not generate cooperation. Organizations coordinate activity and dispense enforcement that can resolve second-order CAPs. Institutional systems thus deliver behavioral outcomes, albeit imperfectly, with unintended consequences. Between 1947 and 1990, the institutional system of Eastern European communism employed multiple rules, such as state ownership of productive facilities, with enforcement via security organizations, such as East Germany’s Stasi.

Second, at a more foundational level, political settlements shape institutional evolution and attendant dilemmas. As ongoing, often informal, mutual understandings among powerful actors to rely on politics rather than organized violence for addressing internal disputes, political settlements shape institutional development and distributions of benefits. They condition prospects for resolving developmental CAPs – and create new ones.Footnote 29 For example, a settlement with a broad social foundation and an incoherent configuration of power indicates rough amalgams of disparate insider groups who, having failed to resolve internal organizational CAPs, pursue disjointed agendas. An ensuing developmental dilemma concerns how to coherently allocate policy authority without narrowing the social foundation’s breadth by excluding formerly included groups. India offers an example. A broad social foundation has included Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs – albeit with unequal influence – interacting with disjointed authority, and no consensus on major issues such as the role of religion in the state. The current government appears to be concentrating power and narrowing the social foundation by marginalizing Muslims (Mody, Reference Mody2023).

Agency thus operates within macro structures of institutional systems based on political settlements that, to varying degrees, shape and constrain meso-level regional, sectoral, and policy structures.

3.1.1 Cognitive Foundations of Agency

Exercising agency relies on understandings of environments, potential responses, and concurrent rationalizations. How might analysts conceptualize such reliance? In contrast to the self-centered, outcome-oriented, material-focused rationality of many economic models – or even game theory’s substantive-rationality approach, which can incorporate social preferences – I ground agency in bounded-rationality. As they pursue goals, agents make choices not only based on incomplete, asymmetric information, as in many economic models; they do so with limited and costly cognition.

How then might agents understand their shifting, uncertain social environments? They construct, utilize, and copy mental models. Mental models combine physical and social categories (e.g., tall, short, old, young, Black, White, Hindu, Muslim) with basic notions of causality. If I water a plant, it will grow. Arising from prior exposure and experience, mental models combine intuitive understandings with deliberate reasoning to generate judgments.Footnote 30 They establish conceptual underpinnings of agency.

People share mental models. Ideas that appear useful travel via narratives and symbols. Shared mental models exhibit common vocabularies, categories, perceived patterns, causal relationships, and implied expectations. By adopting shared mental models, individuals avoid the cognitive costs of mental innovation. Shared models spread across populations with an evolutionary selection dynamic. People copy ideas that appear good or successful and discard apparently bad, unsuccessful ones. Appearances, however, can deceive. Cognitive efficiency notwithstanding, shared mental models often underlie systematic error and bias.

Even so, mental models foster two types of adaptive learning. First, agents engage in hypothesis testing. They utilize causal relations from given mental models to evaluate outcomes. Second, following sufficient inconsistencies, they engage in difficult re-evaluative learning. They discard old and develop new mental models (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2003). Because reevaluation requires costly cognitive effort, mental models exhibit a punctuated-equilibrium dynamic: relatively long periods of stability based on hypothesis testing with occasional bursts of reevaluation. Before a revolution, dissidents may experiment with efforts at reform. Sufficient failure can, however, shift their conceptions of social change.

Shared mental models coordinate understandings in uncertain environments. They resolve cognitive free-rider problems of constructing conceptual frameworks that underlie collective behavioral responses. Institutions and ideologies are shared mental models (Denzau and North, Reference Denzau and North1994). As noted in Section 2, institutions frame understandings of social contexts, in addition to offering incentives and shaping conduits of information. Ideologies are shared mental models with ethical content that convey a vision of a “good” society that could, with sufficient effort and devotion, replace a dysfunctional (or “evil”) status quo. Ideologies express paradigmatic ideas that convey challenge and motivate action. Examples include a Marxist vision of a classless society and a libertarian vision of unregulated free enterprise.

Common behavioral responses rely on the cognitive frameworks provided by shared mental models. Institutions, as shared mental models, indicate social choreography (Gintis, Reference Gintis2009; Ferguson, Reference Ferguson2019). Accordingly, the act of sharing mental models provides a conduit for exercising power. Well-positioned agents use narratives and symbols to direct group activity. Compelling narratives can become shared mental models that invoke power2 influence on rules and expected responses, along with power3 influence on understandings of conflict.

Broadly speaking, there are four interacting types of agency: leadership, following, brokerage, and institutional entrepreneurship. Any individual may exercise several types in various roles, interactions, and circumstances. This section focuses on the first three as background for Section 4’s institutional entrepreneurs.

3.2 Leaders and Followers

Leaders are agents with a following. They openly mobilize people and resources to pursue their goals. Their motivations include material gain, power, a cause or ideology, a sense of obligation, recognition, redemption, and addressing a challenge or problem. Leaders see opportunities where others do not. They break rules (Bailey, Reference Bailey1969).Footnote 31 They provide and withhold services and information. Exercising powers 2 and 3, they issue directives, define issues, and shape understandings by converting their perceptions and proclivities into shared mental models. To exercise power 1, they often recruit others (triadic power format 3).

How does one become a leader? By attracting followers via physical or cognitive influence. Leaders need backing and legitimacy, based on roughly congruent goals, such as avoiding bad outcomes or compatible identities. Leadership capacity depends on personal characteristics, relations to followers, prior actions, and access power’s three sources, notably positions in social networks – all conditioned by historically inherited social context, understandings, and chance. Leaders may make history, but not under conditions they choose. Gandhi did not choose British colonialism.

Followers obey, imitate, conform to, or acquiesce to various directives, commands, signaled expectations, or actions of leaders, rules, or systems. They are members of populations – often victims – and sometimes rule enforcers or visible operators within middle layers of hierarchies. Security services play this dual role. Follower motivations include loyalty, material and social benefit, and self-preservation. They respond to cues, including subtle signals, force, threats, and the framing of issues and contexts in shared mental models – as well as their own inclinations. Yet, even their preferences respond to leader signals, anticipated responses from other followers, and social rules or expectations.Footnote 32 Followers internalize behavioral patterns and prescriptions garnered from prior experience, social context, and leader-follower activity. Followers also choose between competing leaders. These acts of following, even submission to coercion, involve agency.

How does one become a follower? By deciding to obey, copy, conform, or refrain from criticism. Followers make choices under constraints related to feasible action and the perceived consequences of not following. Understandings of such alternatives influence propensities to follow – as opposed to resisting, ignoring, or leading. These interactions, moreover, reflect positions in social networks, associated hierarchies, and power relationships.

3.2.1 Leader-Follower Dynamics

Leader-follower relationships are political. Leaders need to attract followers. Followers exercise discretion.

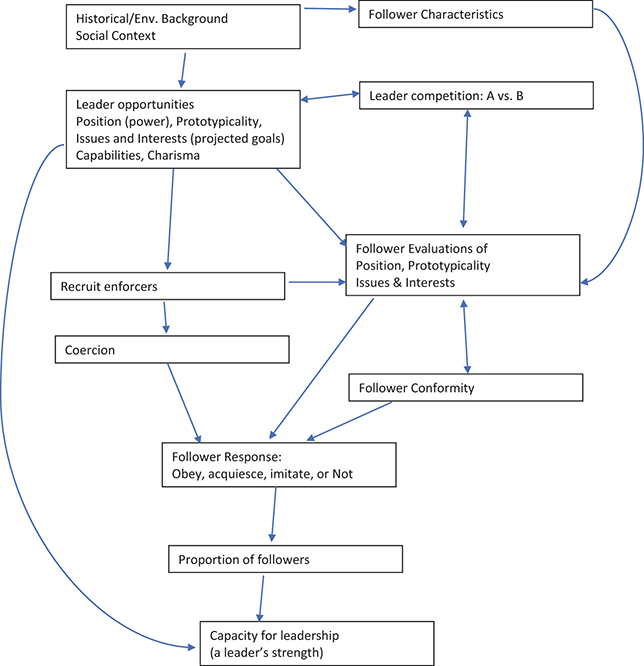

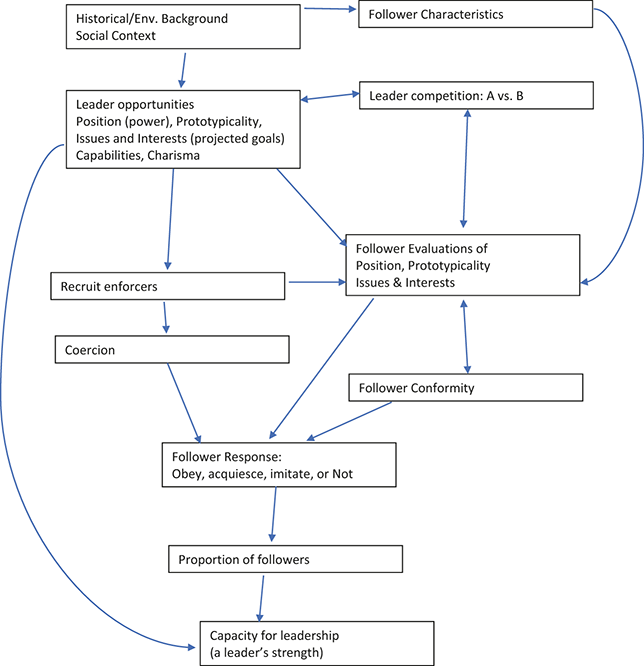

Figure 3 illustrates several pathways of leader-follower interactions.

Figure 3 Leader-follower interactions

Figure 3Long description

Box 1 is labeled Historical or Environmental Background; Social Context. Two arrows point from it to Box 2 (labeled Follower Characteristics) and Box 3 (labeled Leader opportunities; Position (power), Prototypicality, Issues and Interests (projected goals); Capabilities, Charisma). From Box 3, there are 3 arrows. The first is a double-headed arrow leading to Box 4 (labeled Leader competition: A versus B). The second arrow points to Box 5 (labeled Recruit enforcers), and the third arrow points to Box 6 (labeled Follower Evaluations of Position, Prototypicality; Issues and Interests). A double-headed arrow connects Boxes 4 and 6. Two arrows come out of Box 5; the first points to Box 6, and the other points to Box 7 (labeled Coercion). A double-headed arrow leads from Box 6 to Box 8 (labeled Follower Conformity). Boxes 6, 7, and 8 have arrows pointing to Box 9 (labeled Follower Response: Obey, acquiesce, imitate, or Not). An arrow points from Box 9 to Box 10 (labeled Proportion of followers). Another arrow from Box 10 points to Box 11 (labeled Capacity for leadership, or a leader’s strength). An arrow from Box 3 points to Box 11. An arrow from Box 2 points to Box 6.

First, consider leaders. Two types of relationships arise:

1. Potential leaders (A and B) compete for followers. They signal their qualifications as well as directives to followers in response to anticipated follower reactions.

2. Powerful agents, including leaders, rely on others to enforce directives because they lack the physical capability for sanctioning broad disobedience (Hobbes, Reference Hobbes and Booke1668). Enforcement becomes a type of following that sustains leaders.

A feedback dynamic ensues. Leaders act. Followers observe, evaluate, and respond. Leaders observe, evaluate, and respond, and so forth. Reciprocal relationships and exchange obligations develop. Herein, followers may or may not express and act on their preferences. Leaders may or may not face incentives to respond.

Now consider three interacting follower dynamics: coercion, conformity, and assessments of competing leaders. I address these in order.

First dynamic, coercion: Leaders, often via enforcers (triadic format 2), coerce followers. They employ or arrange direct sanctions (power1), threatened sanctions (power2), and manipulative communication that alters perceptions of potential leader-follower conflict and related preferences (power3).

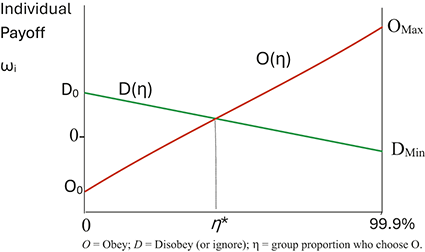

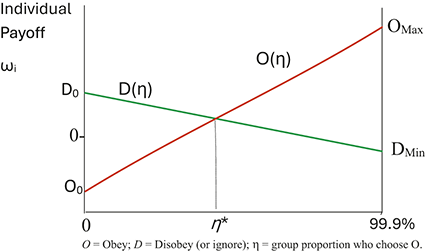

Second dynamic, conformity: Social pressure to conform arises from observed or expected following among others in similar contexts (Hume). Figure 4, a multiplayer game of assurance, illustrates. Here, an expected group proportion of followers (η) influences an agent’s social/material payoffs (ωi) that accompany two possible strategies: obey the leader’s directive (O(η)), or disobey (D(η)).

Figure 4 Multiplayer following game

Figure 4Long description

The x-axis ranges from 0 to 99.9 percent. The y-axis, unlabeled, is present on both sides. The first line moves from from O0 (low in the y-axis) to OMax The second line moves from D0 (high in the y-axis) to DMin (low in the y-axis). The point at which the lines intersect is marked as 0 on the y-axis and η* on the x-axis. The line segment from D0 to DMino is labeled D(η), while that from O0 to OMax is labeled O(η). The section of the y-axis above D0 is labeled Individual Payoff, or Ωi. A note at the bottom states that O means Obey, D means Disobey (or ignore), and η means the group proportion who choose O.

Assume homogeneous members of group G. The O(η) and D(η) curves depict how a marginal individual’s payoff (ωi) responds to strategies D and O as η increases. With an initial equilibrium at η = 0, the D(η) intercept (D0) sits above the O(η) intercept O0. Current social/material incentives discourage following. The negative D(η)) and positive O(η) slopes, however, imply that increases in η enhance the net social pressure to obey. Value η*, an unstable Nash equilibrium, signifies a tipping point: the minimum expected proportion of followers that would incentivize obedience. Below η*, social incentives motivate O, and vice versa. Additionally, both curves shift in response to changes in social context as well as leader influence on follower expectations and understandings of conflict – via powers2 and 3. Notably, given other factors, any η > η* engenders leadership.

Combined pressure from coercion and conformity often induces preference falsification. Followers confront tradeoffs between their private goals, on the one hand, and the perceived net social/material benefits from public expression of conformist activity, on the other (Kuran, Reference Kuran1995). Might one publicize one’s opposition to a leader or regime?

Third dynamic, evaluation: Following relies on assessments of the characteristics and influence of potential leaders within pertinent social contexts. Evaluations respond to four leader attributes: position, interests, issues, and identity.Footnote 33

i. Position: Connections with influential public-and private-sector actors and access to resources underlie a leader’s potential impact.

ii. Interests: The degree to which followers believe a leader cares about their interests.

iii. Issues: Visible pursuit of issues followers care about can foster trust.

iv. Prototypicality: The degree to which a potential leader shares a group’s social identity (e.g., ethnicity) bolsters trust and creates margins for error. Prototypical leaders enjoy leeway to fail, break rules, and even compromise follower interests – without loss of authority. In contrast, non-prototypical leaders may lack legitimacy, even after success. Gandhi’s successful inclusive approach to opposing British colonialism did not appeal to sectarian Hindus – as evidenced by his assassination and the subsequent partition of India and Pakistan.

Russian President Vladimir Putin exhibits prototypical leadership. By projecting a vision of Russian ethnic/national social identity, he has garnered the appearance of concern for popular interests and issues. He enjoys leeway. War casualties and Ukrainian drone strikes within Russia have not diminished public expressions of support. Regarding coercion, Putin has punished evaders (power1), introduced legal conscription (power2), and blamed the Ukraine war on the West – with implied disloyalty for not following his directives (power3).

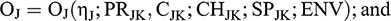

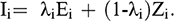

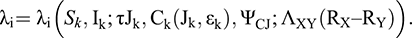

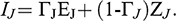

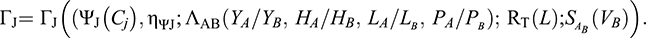

Now consider a general model. Applying a few equations to Figure 4 can illustrate leader-follower interactions. In addition to conformity pressure denoted by the slopes of the O(η) and D(η) curves, follower tradeoffs respond to coercion and follower assessments of competing leaders. In Figure 4, the D0 and O0 intercepts become variables that respond to leader prototypicality, coercion, charisma, and sources of power (position) within a given environment. Assume competing leaders J and K. Disobeying leader J connotes obeying K. We have:

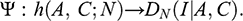

(1)

(1)

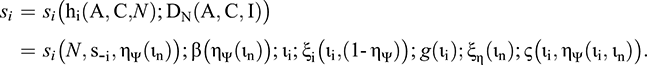

(2)

(2)

ηJ = J’s proportionate following; PRJK, CJK, CHJK, and SPJK respectively signify relative J/K prototypicality, coercion, charisma, and sources of power (position); ENV = social environment.

Changes in these arguments shift D0 and O0, moving the η* tipping point, altering the minimal required following for effective leadership.

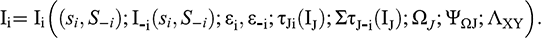

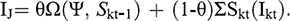

Reflecting this logic, equation (3) illustrates leader J’s potential influence, i.e., leadership capacity:

(3)

(3)

The arguments of (1)–(3) interact and depend on the strategies of all involved. A feedback dynamic arises. An increase in ηJ enhances conformity pressure for OJ, shown as movement along D(η) and O(η). Increases in PRJK, CJK, CHJK, and SPJK shift both O(ηJ) and D(ηJ) leftwards, pushing ηJ* closer to the origin. These impacts both rely on and enhance SPJK. Over time, CHJK may increase, generating reinforcing feedback. Concurrent or subsequent impacts on ENV may amplify or diminish these effects. Whenever these interactions push ηJ above ηJ*, leader J attains a self-enforcing Nash equilibrium among potential followers as obedience levels approach OMax.

A more complicated model could incorporate distinctions between follower groups J and K, heterogeneity among each group’s members, and allow for recruitment within the other group. Additionally, conflict could augment either or both leaders’ claims to prototypicality, solidifying their following, reinforcing or further enhancing conflict incentives.Footnote 34 Society may face corresponding developmental CAPs.

More comprehensively, leaders interact with followers in large social games with multiple equilibria that reflect distinct cultural practices. Applying game-theoretic reasoning to Hobbes and Hume, Basu (Reference Basu2021) asserts that, within such environments, sustainable leader influence relies on attaining a deviation-proof Nash equilibrium. Followers must perceive no feasible alternative actions that could augment their anticipated returns to following. Otherwise, leadership would unravel over time.