Introduction: The Death of Destiny

The future is of interest to everyone. This is because we are all headed there, whether we like it or not. So, too, is the concept of contingency of interest to everyone. We all apply it every day, every time we commit to a decision.

For example, I understand that, if I hadn’t stopped to buy a coffee, I would not have missed my bus. This is an application of the concept of contingency: of the understanding that things don’t have to play out the way they in fact do, that events can go otherwise hinging on chance or choice.

This notion underwrites – at the most fundamental level – our understanding of what it even is to be an agent. Without it, the idea of freedom and responsibility makes no sense. We impute culpability when we acknowledge that the culprit could have acted otherwise, and, if they had done so, their crime – and the consequent harm – would not have been committed.

These twin concepts, of contingency and futurity, are amongst the most important concepts we have. Historically speaking, their combined application has been responsible for the sparking of every single progressive movement, reformation, or renovation. It is only by understanding that the way of the world is not inevitable, and can thus be otherwise, that anyone has ever intentionally attempted to make it otherwise. Understanding this sits beneath all of history’s attempts to make the future a better, more just, place; it foments all attempts to overcome the errors and prejudices of the past.

This way, the concepts of contingency and futurity are also inextricably linked. In our personal lives, we care about our future because our decisions and actions influence that future. And actions only matter, or exert influence, if the consequences they unleash would not otherwise have happened. That is, if they are contingent. Their influence rests in the recognition that, had they not taken place, then everything afterward would have unfolded differently too. Moreover, they matter more in proportion to how lasting these impacts are – and peerlessly so if they cannot be reversed. Or, in other words are indelible.

Sometimes, applying these concepts is matter of life or death. I understand that if I injure myself severely enough, I may die prematurely, which is an outcome which cannot be reversed. Because I know such an outcome is not inevitable, I daily endeavour to avoid it.

We are very fluent with these concepts – of indelibility and contingency as applied to the future – when it comes to our own biographies. But, as we enter the so-called Anthropocene, our wider societies are increasingly struggling with the fact that they now undeniably must be applied much further beyond, to the biography of the planet itself.

That is, our societies now daily struggle with the fact that what happens now has the potential to alter the future for Earth’s entire biosphere. In forms of nuclear waste, climate disruption, resource extraction, and mass extinction, we now recognise the arena – wherein what comes before can influence everything coming after, in ways that aren’t inevitable – has expanded far beyond the traditional remit of human affairs: having spilt into the deeper past, and further future, of Earth’s unfolding biosphere. Humankind now has the power to indelibly scar the planet’s future. The concepts of ‘contingency’ and ‘consequence’ have, by awful necessity, been stretched to the scale of globe and giga-annum.

These are the stakes, providing a backdrop against which all our private aspirations and anxieties must unfold. Putting such stakes into further relief, science now has a firm sense of how much past is behind, and how much future could be left ahead, for life on Earth.

We now understand the universe itself is roughly 14 billion years old and the Earth around 4 billion years old. Though life appears to have begun shortly thereafter, complex life – with skeletons for mobility and nervous systems to sense – has been around for something like half a billion years. Homo sapiens, by contrast, has only existed for something like three hundred thousand years. Recorded history, following the invention of writing, is even shorter, spanning only around five millennia so far. The radiometric dating techniques that produced all these estimates have only been around for a century or so.

By contrast, experts today predict that the future for complex life on Earth is something on the order of one to one and a half billion years.Footnote 1 On this view, compared to the past required to produce us, our species has only just appeared; but, already, the deleterious effects of our activities are being projected over a potentially protracted future.

Entering the third millennium, it is not just facts about human existence, or the wider biosphere, that are acknowledged to be contingent: the fact of human existence, and a thriving biosphere, has also become contingent.Footnote 2

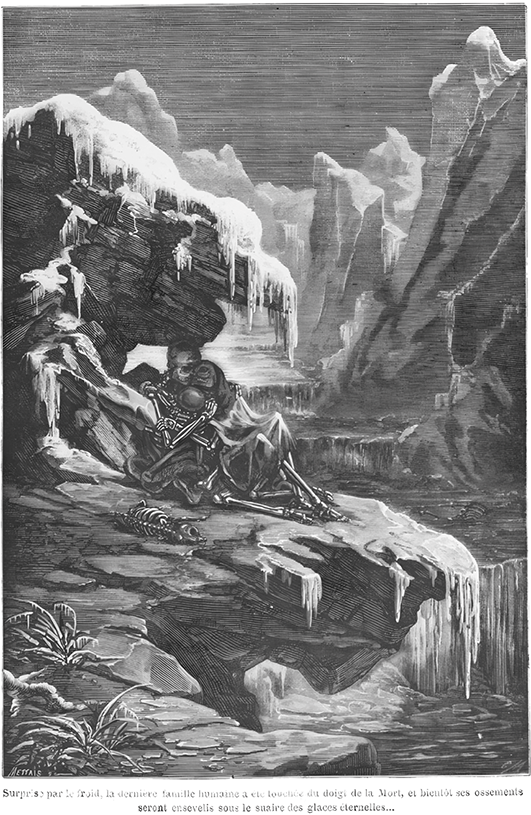

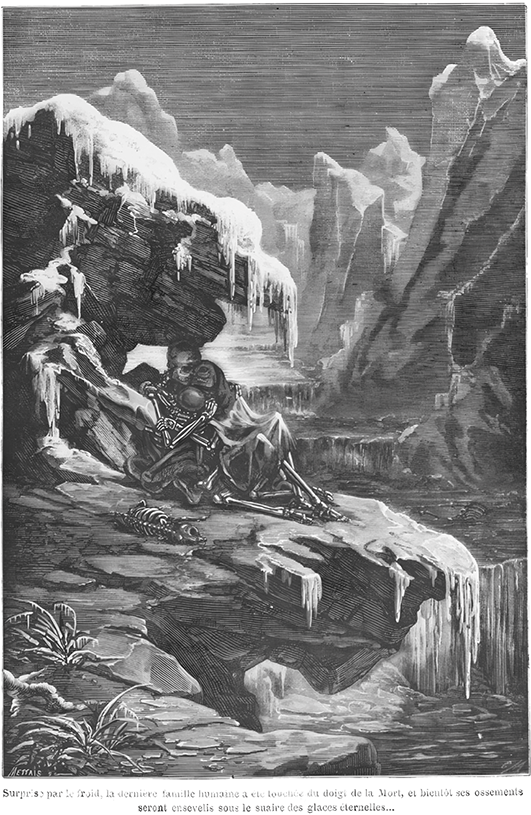

There could be a lengthy, vibrant future for biology on Earth. Or, in the absolute worst case, no future at all. The aeons-long evolutionary epic that produced us, alongside all our fellow species, could produce more diversity and grandeur. Or it could end within a lifetime.

We must now acknowledge that the events in the present, going one way rather than any other, may alter the planet’s entire future: permanently filtering all that comes after, in irreversible, yet entirely contingent, ways.

What follows is the story of how we got here. Even being aware of our predicament is a vast intellectual achievement, millennia and generations in the making. As with all concepts, our modern notions of contingency and futurity did not emerge from nowhere nor did they arrive fully formed. Concepts, like creatures, evolve: in that they are products of cumulated intricacy, and never arrive sui generis. Their evolution takes trial and error, and cumulation and constellation of evidence, which, in turn, takes time.Footnote 3

Though humans now comfortably apply the concept of contingency beyond their own lives, onto a future stretching far beyond, this has not always been so. The reason is simple. For most of history, the evidence to prove such concepts apply beyond our own lives was lacking. It remained underdetermined as to whether nature, at scales larger than our own personal biographical bookends, exhibits contingency and irreversibility. There wasn’t yet the evidence to decide, conclusively and collectively, either way: it hadn’t yet been uncovered.

This underdetermination applied everywhere on the globe prior to its circumnavigation, for obvious reasons. Nonetheless, it should be noted that – despite spanning Europe and the Middle East – the following focuses on how this underdetermination was undone within the Western, scientific tradition. Other notions of contingency and futurity exist in other traditions: from the Indigenous Kulin tribes of South-Eastern Australia, who believed their universe would end if they didn’t maintain their axe exchanges; to Ancient Egyptian claims it is “good to speak to posterity”; to the traditional Chinese belief in “Tian”, as a cosmic principle maintaining moral order in the world, over and above human agency and volition. Richly divergent, historical developments of notions in these traditions will have taken very different lines to those recounted below, but given confines of the Element a truly global treatment cannot be explored here.

The following, then, is the story of how the modern scientific worldview’s notion of contingency was pieced together, thus ballooning not only our sense of how much time might be ahead, but also our estimation of how divergently it might permanently play out.

Indeed, properly grappling with the future is never just about gauging how much further time could be ahead. It also involves uncovering how divergently everything about the present would be if events in the past, which didn’t need to have happened, had played out differently. Because, only by coming to terms with this, do we grapple with just how open and contingent what’s ahead might also be.

Let’s call this the Horizon of Contingency, though it could just as well be called the Horizon of Consequence. This describes that arena of space and time wherein people acknowledge history matters because what can happen in the future is not independent of what’s happened in the past. That is, that arena where what comes after is recognised as contingent upon what came before, in the sense that, had previous events gone otherwise, then everything afterward would have played out differently also.

This arena – this horizon – extends, from the present moment, outward into both the past and the future: making up the tapestry of influences, without which the present wouldn’t be what it is; alongside the cascade of downstream impacts, dictating the direction in which all future moments flow.

It also extends outward, from the human perspective, into space. Because knowledge is tethered to observation, we only know so far as we – or our tools – can see. This way, before humans invented clever ways to survey scales greater than the immediate, it was impossible to disqualify hunches that – beyond the purview of what’s humanly tangible – time exhibits reversibility and all possibilities eternally recur.

This is why this shared horizon, though it is set by knowledge’s shifting frontiers, is materially important. It informs behaviour. How far people have acknowledged it to stretch – beyond our individual biographies – has itself changed over time, as our species has increasingly gained our bearings within time.

So, what lies beyond the acknowledged Horizon of Contingency, at least in the estimation of those doing the acknowledging? Here, things aren’t necessarily assumed timeless or static. Things here can and do change – grow and decay – but just not in a way that is thought to have persisting direction in time.

On one level, this is to do with estimation of the range of contingency, or the scope of unrealised possibility. Counterintuitively, history is interesting – and exerts its influence on the future – because of all the things that didn’t actually happen. It is the entrenching of certain prior possibilities, to the exclusion of others, that explains why the present is the way it is rather than any other way. It is this that makes decisions or events consequential. They only matter when not every possible outcome will eventually come to pass regardless.

But, for most of human history, it could be legitimately assumed that the space of historic possibility was small enough, and the time or space available comparatively large enough, that – beyond the known Horizon of Contingency – all possibilities would exhaustively manifest and thereafter recur and repeat. At the very least, until recently, there wasn’t yet the evidence to satisfactorily disqualify such assumption, beyond scales much more encompassing than the singular human lifespan.

Another way to flesh this out is by borrowing two concepts from physics. There are two types of systems, ergodic ones and non-ergodic ones. An example of an ergodic system is one which reliably visits and revisits all its possible states with a null likelihood of never returning to any one of them. Given enough time, its past and future will eventually look indistinguishable. In technical parlance, it is memoryless.

Contrarily, an example of a non-ergodic system is one which will not pass through all its possible states, because the manifestation of certain possibilities in the past – to the permanent exclusion of others – irreversibly constrains everything that can possibly happen thereafter. Such systems exhibit absorbing states: regions of the system’s possibility space which, upon entry, can never be exited. Accordingly, once it has entered such a region, the system’s entire future will end up looking fundamentally and irreversibly different from its extended past – no matter how much time is available. This way, such systems exhibit irreversibility and memory. Applied to evolution, extinction is a brilliant example of an absorbing state for a species.

The ergodic and non-ergodic distinction is crucial, again, because history only enters the picture – and is able to contingently and irreversibly influence the future – when not everything that can happen does eventually happen. Beyond the horizon of the measured and recorded, it has long been assumed that the spans of space and time are effectively boundless, such that nature’s entire space of possibility is exhaustively manifested and limitlessly remanifested. After all, given enough rolls of a many-sided dice – either sequentially or simultaneously – all possibilities will be made manifest and reliably repeat.

What’s at stake throughout the following is the question of whether nature, beyond familiar and tangible scales, exhibits history, irreversibility, memory, and non-ergodicity in this sense, such that events in the expanded and extended past can indelibly and contingently influence the expanded and extended future. Answers to this question, as we will soon see, have drastically changed over the centuries.

This matters practically because, beyond the acknowledged Horizon of Contingence, all influence of the past and present on the future therefore eventually washes away: the legacy of things going on track, rather than any other, will eventually become irrelevant, because the alternate paths and possibilities remain accessible and will, given enough time, inevitably recur limitlessly.

Over the longer run, there is thus no direction, no persistence, no memory. All impacts, eventually, are reversed, washing out into their opposites. All losses are eventually recouped and compensated, as what is lost is returned. Beyond the established Horizon of Contingency, it is possible to believe that all processes are memoryless and meandering, thus neutering any acknowledged impact of what happens here and now at this larger, non-local scale.

This is of crucial consideration. Within the Horizon, the course of past events matters practically; beyond it, the course of past events is absolved of mattering, at least permanently or persistently. Everything returns in eternity and infinity. It is only in bounded time, time with known dimensions or extremities, that death or loss can be forever.

So, whilst you can feel avoidable losses or local damages keenly within what you acknowledge as the Horizon of Contingency, you can always point beyond it – to that larger scale or interval wherein you assume what’s lost must be returned – in order to remedy or diminish the sense of immediate damage.

For the longest time, this is precisely what people have done – when it comes to scales of space and time beyond the observable – in order to assuage themselves of fear that accidents and losses really matter. For example, people used to palliate the potential for humanity’s extinction on Earth by claiming that our species must inevitably return throughout the cosmic vastitudes of time and space.

Indeed, the Horizon of Contingency is the arena within which concepts like ‘loss’, ‘extinction’, and ‘squander’ gain their full bite: because, beyond it, they are defanged by cycling returns, wherein everything lost is later regained.

Indeed, as we shall see, following the Copernican revolution, from roughly the 1600s up until sometime in the earlier 1900s, many people presumed everything happening on Earth was bound to repeat elsewhere, such that what happened next for our planet didn’t really matter. They pronounced that we cannot be the first, nor last, exemplar of humankind in this universe. At least, such a proposal had not yet been satisfactorily disconfirmed. But science, as will later be explored, has lately demonstrated it almost certainly false.

It did so by putting bookends on cosmic time. What follows is the story of how gauging the placement of the present within this unfolding volume – at increasingly encompassing scales – proves what happens next might just be of significance, not only locally, but far further afield.

Demonstrating this took millennia of inquiry. It took confirming that, in this universe, there was a beginning and will be an end to all things. Only by determining this has modern science thrown into crisp relief the truth that what we do might resonate everlastingly. Because, if time has extremities, then history will never repeat; and if what’s happening here and now will never reoccur, certain decisions can never be taken back or reversed.

On another level, this has also all flowed from increasing appreciation that what’s unrealised far outstrips what’s been realised. Again, historically, given available evidence, it was legitimate to assume that nature’s range of possibilities is comparatively small, and the time or space available comparatively large, such that all potentials will necessarily have already played out, somewhere or somewhen, and will be returned to. This, of course, removes indelibility and contingency from the picture, beyond local scales. Again, history only matters – and alters its future – when not everything that can happen does happen. It is this that makes contingency resonate, as not all outcomes will play out regardless.

Of course, this historic assumption makes perfect sense. Millennia ago, there wasn’t a global archaeological and fossil record collated, such that it was impossible to falsify suspicion that human possibilities haven’t simply been exhaustively cycling since time immemorial. Or, that everything happening right now has already happened before and will recur again on unknown landmasses. And this, as we shall soon see, is precisely what premodern people largely assumed. Later, when such a view began becoming untenable during the Renaissance, the size of the universe radically expanded thanks to telescopes, such that it became plausible to now suppose everything happening here and now had already happened – or was concurrently unfolding – on other planets in the infinity of space.

Darwin’s great insight was that, of all the organisms terrestrially possible, only a select few have and will exist. It is this that allowed him to explain why life looks the way it does today rather than any other way: because certain animals reproduced in the past, to the permanent exclusion of other possible lineages. Nonetheless, of course, the role of chance and contingency in the origin of life itself seemingly remained obscured until the mid-1900s. Up until then, people assumed it would pop up wherever possible in the cosmos. What’s more, it took a while for the scope of contingency in its basic building blocks – that is, the latitude for other plausible architectures – to also bed in.

Which is all to say, the tenor and tone of much scientific advance over the centuries can be seen as a further throwing into relief of the fact that there’s far more possible than is actual, or, there’s far more unrealised than is realised. And, of course, the degree to which we have accepted this is also the degree to which we’ve realised that Earth’s life is cosmically unique (and, thus, cosmically endangered). There may be life elsewhere, but will be unimaginably different. This is a shockingly modern insight. It is why we should care the future of life on Earth, because it won’t be repeating anywhere, ever again. The future is in our hands. There won’t be retries.

This way, the degree to which accumulating insight has expanded the Horizon of Contingency, from our own bookended biographies outward into the cosmos, is the extent to which the stakes – of what unfolds next, here and now – have heightened. It is this knowledge – about the wider universe and its workings – which, as we shall see, has brought home the truth to us that extinction is truly forever.

This way, increasing sensitivity to contingency is a unifying theme of modern science, often providing the leading edge of inquiry’s expanding shockfront against the unknown and uncertain. As the telescope dethroned our sense of space in the 1500s and 1600s, and the geologist’s hammer decentred us in time in the 1700s and 1800s, much of modern knowledge is revealing everything locally actual to be a tiny island within a much wider space of what’s unrealised. This gives contingency bite. We talk of the discovery of Deep Time, and of Deep Space; the following is the story of how we discovered what I call Deep Possibility.

Deep Possibility is the recognition that there’s far more that is possible than is actual. Science’s expansion of the acknowledged space of the possible over the actual is heavily tied, in recent times, to the development of the electronic computer and the birth of computer-dependent fields like chaos theory. Like the telescope before it, the introduction of the computer – and of simulation – in the 1900s made new vistas visible. Because simulation makes tangible that what actually happens is often a tiny subset within the much wider space of what can. Accordingly, just as humankind’s sense of ‘here’ and ‘now’ has been decentred within progressively vaster volumes of space and time, so too is everything ‘actual’ being revealed to be a tiny archipelago within an increasingly vast ocean of possibilities unrealised.

Though this contemporary sense of Deep Possibility is clearly resultant upon science’s increasingly sophisticated capacities for simulation, it can be nonetheless seen as the culmination of a much longer process of inquiry: a process wherein inquirers – across the generations – have had to come to terms with contingency at increasingly encompassing scales of time and of space. What follows is an account of how that unfolded.

1 Contingency’s Gestation

1.1 Palaeolithic: The first counterfactual

In 1939, J.R.R. Tolkien defined what he called a ‘eucatastrophe’, articulating it as an unexpected yet joyous turn: ‘a sudden and miraculous grace’. Like a catastrophe, being an unprecedented break from the prior course of events – but for the better.Footnote 4

Eighteen years later, the Harvard astronomer Harlow Shapley similarly spoke of the ‘Great Moments’ of history, defining them similarly. His candidates included the Big Bang – which led to the formation of the matter we are made from – alongside the evolution of photosynthesis on Earth and the accumulated accidents allowing the first animals to leave the ocean for the land.Footnote 5

Here’s another candidate for a eucatastrophe, or, a great turning in the course of the world. Somewhere within Africa, probably tens of thousands of years ago, potentially hundreds of thousands, a string of sounds fell from the lips of one of our forebears. It expressed, for the first time, what properly could be called a counterfactual.

It might have been expressed in awe, in urgency, in annoyance. We will never know. The utterer will forever remain nameless and unsung. But it was the first linguistic utterance, articulated on this planet, describing something not currently actual. Instead, it was about something else: the way world could be or could become. It was the entrance of the future into our linguistic world. It was the birth of all our tomorrows.

Counterfactuals are part of modal discourse. Modal discourse is the family of locutions expressing states of affairs that are not currently actual, or, in other words are irrealis. They empower a language to express modalities: phrases tracking which things are possible or impossible, contingent or necessary, permissible or impermissible, and conditional one upon another.

Of course, anticipation exists across life’s tree, with evidence of prevision stretching from horse to hymenopteran. In one sense, a nervous system just is a machine for predicting one’s environment. Forms of foresight clearly have evolved piecemeal and multiply across life’s tree. But humans are uniquely empowered when it comes to predicting the future.

Psychologists talk about ‘mental time travel’: the ability to recall the past and predict the future.Footnote 6 This affords us capacity not only to keep track of our biographies, but, also, to a degree, to actively author them. It allows us to learn from yesterday, so as to pursue preferable tomorrows. Our unique aptitude at ‘mental time travel’ rests, almost certainly, on human language and its unique capacity to talk about a world that is otherwise than the one currently, immediately perceived.Footnote 7

Inventing the whole suite of linguistic aptitudes required for this would not have been one clean event. Nonetheless, though anatomically modern humans have existed for something like 300,000 years, behaviourally modern humans emerged around 70,000 years ago. The former looked like us; the latter acted like us. They planned, danced, created symbols, told stories, and began accumulating traditions. Nobody today knows exactly why this happened, but it’s easy to imagine it was caused by – or itself helped cause – an expansion in what our language was capable of expressing.

Perhaps hominids had long been accumulating rich vocabularies of declaration and denotation: anchored purely in the here and now, picking out immediately present objects or events. Perhaps innovations were thereafter made, enabling the embedding of such denotive exclamations within modal constructions. Any shared, complex language presumably needs such constructions, because they allow rules – and, thus, what’s correct and incorrect, or grammatical and ungrammatical – to be articulated and maintained. Rules express what ought to be: in excess of what’s actual, irrespective of whether they are always followed; and no amount of declarations of fact can capture this unique, motivating aspect to their meaning.

Such irrealis constructions, moreover, would have initiated our species into a world of right and wrong – or, at least, where these are recognisable concepts, in addition to guttural feelings, because they are now explicable. The difference between what ‘ought’ and ‘is’ rests, after all, in the fact that former doesn’t need to exist to be meaningful. Norms will have existed long before creatures could talk about them – in some diffuse way, as appetites or conventions – but now they could be discussed, contested, disputed, discarded. Pragmatically, this would have impressively empowered those vocabularies of diplomacy necessary for better cooperation: for resolution of dispute and division of labour.

What’s more, being able to talk about what isn’t (yet) real is likely attached to ‘mental synthesis’: the capacity for stitching together images in one’s imagination, into a combination not previously perceived. Combining a wooden stick with a knapped stone, for example, plucks a hatchet from inexistence.Footnote 8

Investing in better tools and cooperating more fluidly mean more surplus time and energy. This diminishes current pressures on survival, opening room for luxuries such as planning more and further ahead, freeing up more resources for further invention. It’s a loop. Thinking about the future caused more thinking about the future.

By the point this delaminates imaginative horizons from a single lifetime, this would also galvanise the precept of passing recipes and techniques forward – via teaching and tutelage. A stock of insight starts building across generations, rather than resetting with the passing of each one, meaning wisdom instead becomes an intergenerationally building stock. Anthropologists call this ‘cumulative culture’.Footnote 9

By being able to talk about how things ought to be – in excess of how they merely are – human beings could come not only to declare things about the world but also to assess the accuracy of such declarations. A totalitarianism of sensation became accountability to a reality. Indeed, if an utterance or internal state cannot even be said to be wrong, how can it purport to have a world in view: to describe it by being held accountable to it?

Whenever and wherever all this came fell into place, our species dislocated itself from the barricades of the cloistered present – from the absolutism of the actual – in a fashion more intense than any species before. Our kind stepped forth into the spacious world of what’s merely possible: of what-could-have-been; of what-could-yet-be.

The cumulation of the first modal utterances embarked our species on an adventure. Though they couldn’t have foreseen it, the heirloom they bequeathed hoisted Homo sapiens out of the pressing present, eventually coaxing the human mind not only into the deepest past and furthest future but also towards reverse engineering the very workings of the world. And knowing how to imagine the world otherwise is the first step towards making it otherwise. The future is made from motivation as much as prediction.

Our ancestors, when they first started talking this way, began drifting from somewhere and somewhen towards less parochial vantages, and we have been drifting ever since – becoming disoriented and dislocated from the concrete present, but freer in the process. The Horizon of Contingency could begin to expand beyond the fleeting present, forcing unfolding encounters with the truth that the world is chancy and its future is undecided, in ways applying outside the confines of a single, fleeting life.

At the limit, being able to discuss the contingent truth of our claims ultimately opened out into acknowledgement of the contingency of truth-seeking and claim-making itself: eventually flowing into modern awareness that nothing about the human mind is a necessary feature of independent nature. Or, in other words, awareness our species – and everything it cares about – can go extinct, never to return.

Whether all this proves a ‘eucatastrophe’ or a ‘catastrophe’ is yet to be decided. The decision, in the main, is down to us and those coming next.

1.2 Ancient: That the World Is All It Can Be

Piercing the absolutism of immediacy, seeing a world of expanded possibility beyond, modal speak bequeathed to our ancestors a way of negotiating the world that wasn’t governed by the exigencies of sensation nor tethered to the overwhelming present. It cleaved open the room to step back from what is, in order to assess what could – and should – be.

This explains why humans developed agriculture, eventually encouraging urban centres to tumesce, sometime around 10,000 years ago. These advances can be seen as amongst the first widescale, albeit ad hoc, attempts at mitigating and distributing risk – oriented, by definition, at protecting tomorrow’s interests.

Efforts to predict, and thus control, the future remained limited to related techniques for the majority of recorded history. That is, as extemporaneous buffers against unpredictable nature: dams and dikes to protect against flooding; stockpiling and crop rotations to prevent famine; city walls and guards to defend against invasions. This, for the longest time, was the cutting-edge technology for manipulating the future.

During the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom, Amenemhat III dammed the entire Nile. After fires in Rome in AD 6, Emperor Augustus set up a citywide force of firefighters. These evidence anticipation of risks and coordinated attempts to mitigate them. But these were all post hoc preparations for familiar catastrophes: calamities already within the record; disasters that were known to have happened. They evince responsivity to the precedented, not yet the unprecedented.

This connects to a truth summarised by the American historian Robert Heilbroner. He reflected, of the ‘first stratified societies’, that ‘dynastic dreams were dreamt and visions of triumph or ruin entertained’:

but there is no mention in the papyri and cuneiform tablets on which these hopes and fears were recorded that they envisaged, in the slightest degree, changes in the material conditions of the great masses, or for that matter, of the ruling class itself.Footnote 10

This observation appears to be true. It seems odd to us now: but the idea humanity’s future could be not only radically different but also different in unpredictable ways is a shockingly recent addition to worldviews.

One plausible explanation for this is simple. There just wasn’t yet enough recorded history for anyone to notice such change can happen. It is, after all, the historic record that provides determinate proof that human values and views transform over time. But, without a sufficient evidential chronicle available, it wouldn’t be clear this happens.

Sometimes called the oldest book in the world, the Ancient Egyptian Instructions of Ptahhotep, composed 4000 years ago, makes it clear that it ‘is good to speak to posterity’.Footnote 11

Ancient Egyptians argued the best accomplishments are those that become lasting monuments. With their towering pyramids, they evidently aimed to leave a lasting impression. This implies concern for an extended future. However, it is unclear whether they fretted much about whether distant future generations – that is, us – would look upon these monuments the same way they looked upon them. It’s unlikely the architects of the pyramids considered posterity might come to scrutinise and study their works – to interpret or misinterpret them – through the unfamiliar eyes of an unrecognisably alien epoch. There’s scant evidence they suffered any anxiety of interpretation: angst about their beliefs not standing the test of time. Such monuments, indeed, can be read as evidence of precisely the opposite.

Point being, in the long millennia since, humanity’s collective memory has expanded. With the cumulative increase in chronicling and compiling of records, people have progressively come to appreciate the past really is a foreign country. It’s very simple. As recorded time has gone on, there’s been more evidence for the truth of this: and building recognition that things have been different dovetails into building anticipation that they may become different again. (Which nurtures awareness – and anxiety – that the future might look back on your present with very different eyes.)

Relatedly, before a global archaeological and fossil record was compiled, cross-referenced, and communicated across continents – rather than remaining constrained within one – it wasn’t possible to falsify hunches that human history has been cycling on Earth, without definitively beginning, throughout boundless ages.

As we shall later see, such a planetwide record would only begin being pieced together much later: throughout the 1700s and 1800s. Accordingly, for most of human history, people were liable to assume that human history has been going, much in the same way, forever, and would so continue. That everything they were witnessing on their landmass had already been chronicled or achieved elsewhere, on uncontacted continents, or in forgotten aeons. Again, there was not yet evidence to disqualify such assumption.

Accordingly, the Ancient Greeks and Romans, for example, tended to assume that time was eternal and that the future would thus, in the longer term, look like the past. It was invariably assumed that humanity’s combined possibilities – the total space of human potential – were small enough, and the time or space available comparatively large enough, that this entire set of possibilities would exhaustively manifest and thereafter recur and repeat without limit.

This is why Thucydides, writing around 400 BC, thought that chronicling his local history was indefinitely instructive for the future: precisely because possibilities are ‘repeated’, such that ‘human nature’ never truly changes.Footnote 12

But another explanation for Heilbroner’s observation rests in language itself. After all, accumulating insight about the world comes not only from accumulated encounters with it but from clarifications in the ways we talk about it. Refinements in our awareness of what it is our languages are doing when we describe the world, and what they aren’t doing, allow our languages to better model that world. And, as with all other forms of discovery, this takes time.

Thucydides’s sentiment can be tied, that is, to a conception of possibility prevalent throughout the premodern world, which defined it as ‘that which sometimes happens’. This was by contrast to necessity, defined as ‘that which always happens’, and impossibility, as ‘that which never happens’.

This has been called the ‘statistical interpretation of modality’. It tethers modal definitions to ‘temporal frequency’, or, concrete realisation in time.Footnote 13 Put differently, it’s the same as saying ‘nothing that’s possible never happens’. Though this basic assumption pre-existed him, it was first made explicit by Aristotle, who was the first to attempt to clarify what we actually mean when we deploy modal language.Footnote 14 In the Metaphysics, for example, Aristotle evidenced his assumption by declaring that ‘evidently it cannot be true to say ‘this is capable of being but will not be’’.Footnote 15 This formulation thus limits possibility to what is called a ‘diachronic’ conception: tethering it to what actually happens in time, thus blunting conception of entirely unrealised possibilities. Across his corpus, Aristotle consistently defines ‘impossible’ as what is never the case; ‘necessary’, as what is always the case; and ‘possible’, as what is sometimes the case.Footnote 16

Though elegantly intuitive, this formulation obstructs articulation of possibilities that have never once happened before.Footnote 17 It blunts sensitivity, in other words, to entirely unprecedented potentials. Writing in De Caelo, Aristotle revealingly reasoned that nothing which has always existed can be ‘destructible’, because the possibility of its destruction would, necessarily, have already come to pass.Footnote 18 Combined with his belief in the eternity of the past, this becomes the uninspected assumption that there is no such thing as a genuine unprecedented possibility.

Aristotle – and other premodern thinkers – readily applied this to wider nature as much as to human history, assuming things simply cycle limitlessly, and everything that can happen already has happened.Footnote 19 Hence, they lacked the idea that the further future – at the largest and most systemic scales – could come to look drastically different from the extended past. This, understandably, would have gelled comfortably with their lived experience: wherein material conditions didn’t visibly alter – in undeniably novel ways – during a single lifetime.

Given assumption of a limitless past, Aristotle therefore concluded ‘each art and science has often been developed as far as possible and has again perished’, such that the ‘same opinions appear in cycles among men’. He held this had happened ‘not once nor twice nor occasionally but infinitely often’.Footnote 20 Within ‘the multitude of years’, he insisted, ‘everything has been found out’.Footnote 21 Aristotle even elsewhere claimed the aim of inquiry is merely to rectify ‘defects’ in knowledge – that is, the recollection of what’s forgotten.Footnote 22 Tellingly, the Greek word ‘encyclopaedia’ contains the word ‘cylcos’, implying knowledge is a returning circle.

Assuming time is ‘vast and immeasurable’, Plato also claimed the past is of ‘an infinitely long period of time’: such that, in his eyes, countless civilisations have ‘come into existence’, and just ‘as many’ have ‘perished’. From this, he reasoned, their social and political arrangements have been of every possible kind. Every permutation of human ‘goodness’ and ‘badness’, he assumed, must have already been passed through innumerably many times.Footnote 23

By the same token, he believed all possibilities would, inevitably, be manifested again, unceasingly throughout the measureless future, regardless of what happens now. Assuming this meant assuming that no human potentials can ever be permanently lost, or irreversibly disappear from existence, including the potential for human existence as such. Indeed, Plato spoke of the

… periodic destruction at long intervals of the surface of the earth by massive conflagrations …

But he also clarified that ‘the human race has often been destroyed in various ways – as it will be in the future too’.Footnote 24 The supposition therefore being that, even if humankind should be entirely extinguished, it would simply endlessly return. Other thinkers, like Xenophanes, had already made similar claims.Footnote 25

This is why the premodern world lacked our modern concept of extinction: which, by definition, involves irreversibility. There simply wasn’t yet the collated evidence to determine that once species are wiped out to the final member, they are gone forever. In absence of contrary proof – which, again, wouldn’t arrive until a global picture of the fossil record was pieced together – it was, again, impossible to banish presumption that eradicated species would simply, eventually, always return. Given ancient definitions of modality, after all, all possibilities – including species themselves – sometimes are not and sometimes are.Footnote 26

More precisely, on this view, no genuine influences from the present persist into the further future, because the future will be a repeat of the past regardless of what happens now. Nothing can be lost, nothing gained. It was for this reason that, around 50 BC, Cicero claimed there was little point in seeking to impart legacies that are ‘diuturnam’, or durable, much less ones that are indelible.Footnote 27

Indeed, Cicero and many others, following Plato’s initial conjectures, believed that catastrophes regularly destroyed civilisation – wiping away all accumulated learning – such that human history could all play out again, in unending cycle. This is why Lucretius entertained the possibility that everything he was witnessing in his own life – all unfolding achievements – were ‘things’ which had ‘happened before’: it’s simply that countless earlier ‘races of human beings perished in great conflagration’ and their achievements ‘were razed by a mighty convulsion of the world’.Footnote 28 Once more, ahead of sizeable evidence to the contrary, there wasn’t yet the combined evidence to disprove such suspicion.

But what of Plato’s Republic? Surely, he was thinking of something unprecedented when delineating his utopian vision for ideal society. Not so: midway through the dialogue, Plato has Socrates explicate he is envisioning a situation that ‘has been’ in the ‘infinite time past’ – or, otherwise, is ‘now’ in some ‘region far beyond our ken’ – such that we can also be sure it will inevitably return again ‘hereafter’.Footnote 29

For the ancient world, therefore, given limitations of compiled evidence as much as limitations of language, possibility was inherently tethered to prior manifestation, such that cogently articulating the entirely unprecedented was stymied. This is why, as Heilbroner observed, the premodern universe lacked our modern conception of the future: as undecided and undetermined and populated by what’s unprecedented and unpredictable. Indeed, Aristotle readily affirmed that ‘it is of actual things already existing that we acquire knowledge’: which is the same as denying we concretely can know anything about things which haven’t yet existed.Footnote 30 If we can’t talk of things that aren’t already actual, then the only way we can talk of the future is as a loop of the past.

Given available knowledge, on balance, it was – back then – safer to assume time was eternal and all possibilities simply cycle, such that the future would, in the longer term, be a repeat of the past and all present influences be laundered away. The Horizon of Contingency was, thus, limited in scope to one’s own lifetime and, at most, one’s own polis or nation. Beyond that, it was impossible to verify new things can happen and old things can be irreversibly lost across an undetermined, undecided future. The future remained shallow.

1.3 Medieval: That the World Could Have Been Otherwise

Similar definitions of possibility – and, thus, assumptions about the future – persisted well into the Medieval Era. Glossing Aristotle around AD 1100, the Arabic philosopher Ibn Rushd explained that ‘the term ‘possible’ is used’ to talk either of that which ‘happens more often than not’ or ‘less often than not’.Footnote 31 Modality remained tied to diachronic definitions and to manifestation in time: subtly precluding the possibility of the entirely unprecedented; reducing contingency to variations upon what’s already been.

This keyed into a wider feature of much premodern belief: the assumption that the world is inherently reasonable. For if all possibilities at some point come to pass, the only things that are never actual must be so for demonstrable reasons of logical incoherence or contradiction – rather than by dint of brute facticity or arbitrariness. This is the same as assuming that our world is maximally rational. Or, that things are the way they are for entirely demonstrable reasons – exhaustively amenable to deductive analysis – such that they couldn’t justifiably have been made otherwise than they are. (Note that this is incompatible with the modern notion of a ‘law of nature’: as a parameter or constraint that could plausibly have been otherwise; or, is the way it is for weaker reasons than lack of logical contradiction.)Footnote 32 This, in turn, underwrote a perennial Scholastic platitude: ‘ens est bonum convertuntur’, or, ‘being and good are convertible terms’. As Aristotle originally had it, ‘in all things, we affirm, nature always strikes for the better’.Footnote 33

In a yet broader sense, such belief was again consequent upon narrow definitions of modal terms. Insofar as their usage was restricted to straightforward descriptions of events within the world, their more subtle application – as evaluations of our conceptual frame upon that world – remained implicit and undeployed. Put simply, if contingency narrowly refers only denotatively to things, it has not yet been critically applied to our concepts about things. Prior to the elaboration, explication, and deployment of this meta-descriptive dimension of concepts like contingency, as picking out the limitations and uncertainties of rational judgement itself, it was thus natural for thinkers to fail to catch sight of the distinction between our moral expectations and independent reality.Footnote 34

Nonetheless, the introduction – and eventual ascendency – of Abrahamic religion had introduced an ‘alien intrusion’ within the pagan worldview.Footnote 35 With the spread of Christianity and, later Islam, across the European and Arabic worlds, there arrived a sense of crisp direction in time: stretched between the twin extremities of Genesis and Judgement. The Hellenistic sense of eternalism was eventually toppled by Abrahamic belief in universal chronology.

On the one hand, eternity still saturates these creeds. Worldly time was conceived of as but a brief hiatus, environed by two eternities: a vanishing ‘vale of tears’ cleft between the boundless precedent of an uncreated divinity and, afterward, the unending afterlife promised for the souls He created.

On the other hand, the ‘intrusive’ element was immense. Jesus’s crucifixion on Golgotha split history in two. For his disciples, at least, it introduced a crisp ‘before’ and ‘after’: absolving all humans of their sins – everywhere – thus being incapable of precedent, reversal, or repetition. Everything afterward – that is, the future – would be different.

Previously, there was no universal reference point against which to orient ‘now’. Indeed, Aristotle had once reasoned that, if history cycles, we cannot properly say we come after our ancestors, because, in another sense, we also come before them.Footnote 36 For believers in the new Abrahamic creeds, such reasoning could no longer apply. God can only sacrifice himself once, after all. If one time was not enough to get the job done then the act – of universal salvation, of the saving of the souls of everyone, everywhere – wouldn’t have been fulfilled. Divinity, being omnipotent, doesn’t work in half-measures.

Which is to say, Jesus’s crucifixion was, to his disciples, undeniably an event that had never once happened before. Precisely the same applied, for early Muslims, to the arrival of the Prophet Muhammad’s teachings around a half-millennium later.

These beliefs would – slowly but surely – disband elder conviction that the future must also be a closed-off repeat of the extended past. But this, as yet, was far from an acceptance of historic contingency: that is, sensitisation to the fact that the past could have played out differently, thus leading up to an unrecognisable present; nor that the future can play out multiply, depending upon what happens now.

This was because, for Muslims and Christians alike, the arc of events – from Creation to Judgement – was exhaustively orchestrated, from outside worldly time, by divine diktat. In its broadest brushstrokes, history’s unfolding was considered predetermined, which, again, was highly compatible with a solely ‘diachronic’ conception of possibility. The things that can happen exhaust the things that will happen: hence, determinism.

Apocalypse was thus conceived of as the ultimate – unavoidable – culmination of God’s infallible judgement, inscrutable though this may remain for mortals. It is important here to note that apocalyptic prophecy is distinct from the modern art of prediction, though they both are oriented towards the future, in that only the latter embeds awareness of its own corrigibility. The former does not – indeed, this is its very appeal – such that it cannot be sensitive to possibilities beyond its ken, or, indeed, assent.

This, again, appealed to the wider belief that ours is a maximally rational universe: where everything is the way it is – and not otherwise – for revealable reasons. Such conviction was inherited from Aristotelianism and sustained into Christian Scholasticism and Islamic Kalām. As Anselm of Canterbury proclaimed around 1080 AD: ‘whatever is, is right’.Footnote 37

But it also played into to a view that, though worldly things could change, they couldn’t do so in meaningful nor multifarious ways. In the words of Nicholas of Autrecourt, ‘nothing in the universe, either in particular or in general, can be useless, for, if it were, then it would be better for it not to be than to be’.Footnote 38 Such conviction, again, prohibits irreversible loss. Because, if any existent thing ceases to be permanently, it leaves a gratuitous gap in creation, where something could be, but simply never is again. This was simply incompatible with underlying conviction the universe itself is maximally just, as it would introduce an unjustifiable chasm in creation’s fabric. By the same token, a genuine novelty would reveal what was previously an imperfection – a vacuity of value, an empty vessel.

The uninspected assumption was that what seems morally unjustifiable must be naturally impossible. Thus, having declared that ‘we feel displeasure when we believe that a thing has become non-existent’, Nicolas of Autrecourt further reasoned that the universe must, across time, contain an equal amount of its possibilities, insofar as it needs to be ‘always perfect to the same extent’. It must, over time, house an invariant ‘complement of good’.Footnote 39 Variation in overarching ‘good’, after all, would introduce imperfection into creation. In other words, the aggregate ‘goodness’ in the universe is not contingent, is not a variable that can alter contingent upon local events or happenstances. If something bad happens here, something good happens over there, balancing out the whole. Again, this ties into definitions of possibility as that which sometimes happens and sometimes doesn’t, which block appreciation of irreversibly wasted opportunities, frustrated potentials, and irrecoverable harms. Put simply, on such a view, the world, at large, cannot get better, or worse, in the same way we now acknowledge it can. Indelible stains on the human record or unprecedented progressions over past oppressions were unthinkable.

Evidently, this also made the extinction of species – and, even more so, of mind – inconceivable. As Saint Bonaventure, again glossing Aristotle around 1200 AD, declared: the cosmos ‘cannot exist without men, for in some sense all things exist for the sake of man’.Footnote 40 Writing later, Aquinas likewise claimed that it is an ‘impossible supposition’ to envisage a world without intellects in it.Footnote 41

But, more profoundly, it stultified all sense of meaningful world-historical change – or, large-scale historic shifts for better or worse. Given ours was considered a maximally rational world, God was on pains to maintain its invariant goodness over time, throughout all its shifting permutations. The total ‘bonum’ in the universe was considered indestructible and invariable: globally conserved through all interactions and local shifts. Again, limiting possibility to narrowly ‘diachronic’ usage – as describing that which comes and goes, but only ever as a return of what’s come or gone before – means that it can only describe trivial rearrangements rather than irrecuperable losses or genuine novelty.

As Augustine put it, ‘variable good’ is governed, in the last instance, by ‘immutable good’.Footnote 42 Meaning that the ‘goodness’ of created beings can, locally, ‘be augmented and diminished’; but, globally speaking, all variations must ultimately average out as ‘good because their author is supremely good’.Footnote 43 This, again was essentially continuous with the elder, pagan view, which was aptly summed up by Lucretius, who claimed that the ‘aggregate of things palpably remains intact’, because every death or disappearance is necessarily matched by compensatory birth or renewal:

no visible object ever suffers total destruction, since nature renews one thing from another, and does not sanction the birth of anything unless she receives the compensation of another’s death.Footnote 44

Thus, beyond the implacable and divinely orchestrated countdown to apocalypse, when it came to secular affairs and to human expectation, the medieval outlook – by and large – wasn’t too far from the elder view of cycling stasis. Local changes of fate were feasible, but never any shift from the view of the globe: nothing irreversibly destroyed, nothing genuinely novel; always a revolving, never a rupture. Indeed, certain – albeit heterodox – believers happily made pagan eternalism compatible with their Christian faith, such as Siger of Brabant, who in the 1200s professed that nothing is truly unprecedented, such that

the same species which were, return in a cycle; and so also opinions and laws [and] all other things, although because of the antiquity there is no memory of the cycle of these.Footnote 45

Though deemed heretical, Siger’s opinion was not far from the words of Ecclesiastes:

What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.Footnote 46

Indeed, despite the fact that Abrahamic religion taught of a crisp beginning to worldly time, there was no consensus during the Middle Ages about the span from then until the present.Footnote 47 Many assumed this duration was, to all intents and purposes, immeasurable: and, thus, readily compatible with Classical teaching that everything humanly achievable must, by necessity, have already been achieved, such that our future could not come to look drastically divergent from its past.

This outlook came to be embodied in the Medieval metaphor of the ‘wheel of fortune’ – the Rota Fortunae made popular by Boethius – whose attraction was adroitly captured by Reinhart Koselleck. The ‘circling wheel’, Koselleck wrote, ‘pointed to the iterability of all occurrence, which in spite of all ups and downs could not introduce anything which was, in principle, new to the world before the time of the Last Judgement’.Footnote 48

But this outlook would begin being dissolved from within by the acidic notion of divine omnipotence. During the later Middle Ages, a string of theologians – both Islamic and Christian – became eager to buttress their conviction that Deity was free to have made our world completely otherwise. This motivated them to develop logical definitions of possibility unmoored and unanchored from all precedent, or, manifestation within time. Indeed, in buttressing Divinity’s omnipotence this way, they were led to rejecting that our world exhausts all the ways it could be. This not only evacuated our world of rational structure – where everything is the way it is for a deducible reason – but also opened the door to sensitisation to all the ways our world itself could become otherwise, in ways unprecedented. The future began trickled into the frame, eventually becoming a torrent, then a deluge.

Scholasticism made it to the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age, dating roughly from AD 700 to 1300. Here it blossomed into the teachings of the Muʿtazilite falāsifa (i.e. philosophers) who sought to elucidate the rational necessity of the cosmos along Aristotelian lines. This triggered a counter-reaction from what came to be known as Ashʿarism. The Ashʿarites instead foregrounded God’s limitless will, forging a position known as voluntarism. They reproached the Aristotle-inspired encroachments of the Muʿtazilites, for leveraging chains of logical and deductive demonstration over divine decision. In order to exalt God’s freedom and omnipotence over such rationalist straightjacketing, they asserted the centrality of divine will in every worldly happenstance and sought to strip the cosmos of any inherent, indwelling rational order.

A prominent example comes from al-Ghazālī and his Tahāfut al-Falāsifah of 1095. Here, the Sunni theologian wanted to dismantle the Peripatetic faith in the demonstrability of the connection between cause and effect. As such, he presaged Hume, by saying that the link could not be logically demonstrated.Footnote 49 He did this by conjuring up unrealised, yet logically plausible, events that could disrupt regular causality.Footnote 50 This, in many ways, may have been philosophy’s first true conception of catastrophe: a grasp of the purely unprecedented, based upon a higher order acceptance of the disunity of human reason and wider existence.

As such, Islamic and Christian voluntarist theologians moved away from elder definitions of ‘contingent’ as that which doesn’t happen at one moment but does happen another. Instead, it began being deployed to express plausible alternates to what happens at one moment, which thus never have to otherwise come to pass. In so doing, they divorced the concept of possibility from realisation within time, emancipating and liberating its range from the known, familiar, and established course of events.

Though it was already tacit in Augustine’s fifth-century proclamation that ‘potuit sed noluit’ – that is, there are worlds God could have made, but simply didn’t – this new, properly ‘synchronic’ definition of possibility was first explicitly articulated by Duns Scotus. Writing near the opening of the fourteenth century, Scotus announced:

I do not call something contingent because it is not always or necessarily the case, but because the opposite of it could be actual at the very moment it occurs.

Scotus here made explicit what was implicit in prior thinkers from al-Ghazālī to Peter Damian, finally consummating a separation of possibility from precedent or eventual manifestation. ‘In the late medieval modal theory’, writes Hintikka, ‘the domain of possibility is accepted as an a priori area of conceptual consistency [which is then] divided into different classes of compossible states of affairs of which the actual world is one’. In other words, this new conception explained possibility as delineating a space of conceptual consistency carved up by abstract relations of compatibility, rather than barricaded and gerrymandered by the fickle horizons of established human experience. Duns Scotus, in other words, had unwittingly provided the logical seedbed of the modern sense of the future as the domain of the entirely unprecedented.

Bewitched by omnipotence, late Medieval theologians started excitedly pondering the ways in which this world could be otherwise. The historian Amos Funkenstein wrote of ‘schoolmen [driven] by an almost obsessive compulsion [to] devise orders of nature [different] from the one admittedly existing’.Footnote 51 This became ensconced in the popular distinction between ‘potentia dei absoluta et ordinata’ – or, between God’s absolute power and ordained power – an important bifurcation baptised by Alexander of Hales, to describe the order God upholds within this world (‘potentia ordinata’), as opposed to the totality of what he could make manifest (‘potentia absoluta’).

Buttressing God’s freedom in selecting between worlds involved pushing the claim that it is not the way it is for any binding reason nor logical necessity, but is so purely because of arbitrary choice. This eventually led to the claim, articulated most prominently by William of Ockham in the 1300s, that none of the dictates of reason could restrict what reality can be. Motivated by conviction that our mental categories (universals, abstractions, sensations, species, propositional structures) cannot place limits upon what God can do, Ockham imagined existence completely voided of all such mental contents. He did this by deploying the recently strengthened modal logic to put this evacuation into counterfactual relief. That is, arguing that only singulars truly exist, because categorial structures cannot impinge on God’s will, Ockham imagined counter-to-fact worlds wherein all such mental categories are procedurally eliminated from the universe, thus abrading reality to its mind-independent kernel. Referring to this as the ‘Principle of Annihilation’, he imagined universes where everything is removed – ‘toto mundo destructo’ – except for one singular object, in pure autonomy of all cognitive generalisations or phenomenal contents.Footnote 52 This way, Ockham became the first to properly propose a possible world entirely without intellects within it.

In other words, this was the origin of our modern conception of ‘scientific realism’ or ‘robust mind independence’. It’s no coincidence that, writing centuries later, Galileo deployed a similar vocabulary of annihilation, pondering the counterfactual erasure of experience: ‘I think that tastes, odours, colours, and so on are no more than mere names so far as the object [is] concerned … Hence, if the living creature were removed, all these qualities would be wiped away and annihilated.’Footnote 53 Again, by definition, putting reality’s mind-independence into relief requires the emancipation of conceptions of possibility from prior human experience. The fact existence will continue without minds like ours can only be articulated counterfactually – that is, insofar as mind like us persist. Hence, why such articulations would have to wait for the late Medieval liberation of possibility from precedent. Ockham’s thought experiments – providing the first robust benchmark of mind independence – are the primal scene of all future articulations of our potential extinction.

Much has been written on how this provided the crucible for the birth of modern science.Footnote 54 The ‘compulsion’ of earlier theologians to imagine worlds entirely otherwise than the apparent one was prologue to the later discovery of scientists that the world in fact is otherwise than it intuitively appeared.

Indeed, as already hinted at, imagining hypothetical objects entirely outside of all conceptual or experiential relations, as Ockham did, lies at the root of the Early Modern distinction between ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’, or mind-independent and mind-dependent qualities. Funkenstein, moreover, notes Galileo’s employment of entirely counterfactual scenarios, analogous to Ockham’s own, to arrive at the unobservable, and because physically impossible, limit cases (i.e. a frictionless plane) that were required to formulate counterintuitive laws like that of inertia.Footnote 55 Oakley and Milton point out the centrality of such thought to the discovery of the modern idea of a ‘law of nature’ itself.Footnote 56 That is, as a parameter that could have been otherwise, in ways blind to the demonstrative approach of Scholasticism, but nonetheless carves up the limits of what can happen within this world. Such regularities, being arbitrary and contingent, cannot be rationally deduced from afar, but instead must be investigated by close-up encounters with the world – or, in other words, empirically and inductively.

In this way, modern science can be seen as a fortuitous ‘exaptation’ of late Medieval obsession with omnipotence. (Where an exaptation is a trait evolved for one purpose, potentially now defunct, fortuitously becomes adaptive for another.)Footnote 57 But, aside from generating the intellectual conditions enabling scientific inquiry, it also fomented a growing sense of the future. The two go hand in hand: by enabling the vocabularies required to reverse engineer the nomological structure of the universe, and thus beginning technoscience’s accelerating transformation and restructuring of our material conditions, these same vocabularies allowed people to capture the burgeoning sense that genuine change was afoot within one’s own lifetime.

Ultimately, in making the world arbitrary, omnipotence stripped it of indwelling reason. Hans Blumenberg called this the ‘Ordungsschwund’, or, loss-of-order, that stood at the late Medieval threshold to modernity. The laceration of the old, traditional worldview is what opened the floodgates on the future.

It should be noted here, also, that the late Medieval invention of ‘synchronic’ possibility, as the selection between simultaneous alternates, may also have been upstream of the development of both of the major modern systems of ethics: utilitarianism and deontology. Ancient and Medieval normative theories were broadly aretalogical, or, centred on performing the virtues. This again was often rooted in precedent, or replicating the habits and prior example of admirable people. This, clearly, fits with a ‘diachronic’ conception of possibility: wherein, as all possibilities eventually come to pass regardless, and can never become forever frustrated, the aggregate of good in the universe over time cannot be affected. Utilitarianism appeals to the idea that the aggregate of good in the cosmos is variable, in potentially unprecedented ways, and teaches that we should select between our actions based on maximising that aggregate. Selecting between alternate actions, some of which may remain forever unrealised, thus plausibly alters that aggregate – in meaningful and lasting ways – because not all possible permutations are guaranteed to come to pass regardless. Deontology, likewise, appeals to a rule of conduct which is meaningful even though it may have never been fully obeyed by any limited, finite being. It is very consciously not rooted in precedent or prior actions. This way, the late Medieval development of new modal logics may have paved the way for, centuries later, the invention of modern systems of ethics too.Footnote 58

What’s more, by stripping reality of dependence on mental structures, this inculcated sensitivity to things and events falling beyond all current conceptual categorisation. This lubricated responsivity to the cosmos’s non-responsivity to semantic capture and moral expectation: manifesting as new openness to the unexpected, inexplicable, catastrophic, and anomalous. Of course, humans have always dealt with these things, but now new concepts had been developed through which to express and model them.Footnote 59

In short, by starting to encourage ways of thinking about how the universe could have been otherwise than they believed, people started to realise it already is otherwise, the realisation of which – snowballing into an undeniable break with the past – lent momentum to a burgeoning sense things can and will become otherwise in ways unscripted by Deity’s predetermination.

Of course, this would not happen overnight. Expectations on the future remained shallow. This was, primarily, because of widespread belief that history was much nearer its end than its beginning. Each generation assumed it might be the last. Jesus himself had told his disciples as much. Indeed, most believers, during the Middle Ages, actively wanted the end to come. It would liberate them, they believed, of their Earthly suffering and consecrate the final sorting of Good from Evil. Existence was considered irredeemably alloyed with sin; the only way to purify it was to end it.

In the thirteenth century, towards the end of the Middle Ages, the English polymath Roger Bacon recorded his hopes for the future. He believed ‘individuals, cities, and whole regions can be changed for the better’ through study and education. But, nonetheless, Bacon still assumed he was living nearer the end, adding that ‘it is believed by all the wise that we are not far from the times of the antichrist’.Footnote 60

In 1493, the German writer Hartmann Schedel set out to compile a chronicle of time in its total compendium – stretching from creation to apocalypse. At the end of the book, he left blank pages for his readers to fill in and record history’s remaining episodes themselves. The entire volume was roughly three hundred pages long. Schedel left only six blank pages for time’s remaining episodes.Footnote 61

What’s more, again, what unfolded over those remaining blank pages was considered prewritten and predetermined. Even the voluntarists believed that God had selected ours as the best of all possible worlds, wherein value and life are invariant and indestructible qualities, sealed away from vicissitude. Though local change could be affected, the aggregate ‘bonum’ of the universe was maintained by God and couldn’t be meaningfully altered by humans. ‘Mind’ and ‘life’ were not yet subsumed within the Horizon of Contingency as historical variables: they were not thought of as emerging from nature nor of as potentially disappearing from it. Instead, all the regions of the premodern cosmos were thought of as populated with spiritual agents – whether angelic or demonic or human – across time and space. The Ptolemaic universe had no unoccupied regions. There was no acknowledgement that nature has an autonomous history, wherein vast regions in time and space can be unpopulated and abiotic. Whether through deity or directionless repeats, an invariant baseline of ‘justice’ or ‘life’ was thought of as maintained from start to end.

But then, by good chance, someone discovered how to measure chance, thus allowing the unpredictable nature of the future to – finally – become an object of study.

2 Future’s Dawn

2.1 Early Modern: That We Can Make the World Otherwise

The historian of ideas Ian Hacking once remarked at how curious it is that, despite the fact almost all other fields of mathematics find their first flourishing in the ancient world, the study of probability remained a ‘absent’ until the dawn of modernity.Footnote 62 There is long-running mystery over probabilism’s belated birth: or, why ‘probability calculus was so long developing’.Footnote 63

One reason for this, which has yet to be noticed, is the lack of ‘synchronic’ definitions of possibility prior to Duns Scotus. Conceiving of each throw of the dice as the expression of a wider space of simultaneous alternatives is requisite for grasping probability. Without grasp of ‘synchronic’ possibility, there could be no such understanding.

Of course, in sortition, divination, casting of lots, and astragali (heel bones used as dice), and cleromancy, there is a ‘prehistory of randomness’ and ‘luck epistemics’ going back deep into the ancient world.Footnote 64 Yet this was apprehended as inscrutable ‘fortuna’, rather than anything formally tractable: until, that is, Gerolamo Cardano’s Liber de Ludo Aleae, which was written around 1550 and published posthumously in 1663.Footnote 65

In this pathbreaking work, Cardano – a polymath who often resorted to gambling to support himself financially – conducted the ‘first real experiments in the mathematics of chance’.Footnote 66 Cardano’s breakthrough, now deceptively intuitive yet at the root of the entire edifice of the modern world, was in conceptualising each dice-throw as the expression of a larger set of possibilities, thus developing the notion of a synchronic possibility space (which Cardano entitled the ‘circuit’ of the die). In deploying numeral notations to track frequencies within this reference class, Cardano invented the modern field of probability and made the future enumerable. Indeed, by 1654, Pascal – in his correspondence with Fermat – deployed the method to robustly measure future outcomes: computing the cascading number of possible results from an interrupted game of chance so as to properly allot winnings between players, given likelihoods each player would have won had the game concluded.Footnote 67

This, in important ways, provided the threshold of ‘advanced modernity’, leading the way to our modern ‘world of speed, power, instant communication, and sophisticated finance’.Footnote 68 Indeed, the word ‘risk’ first entered the English language throughout the 1600s, percolating first through the professional vocabulary of maritime traders and their insurance underwriters. With the coincident explosion of financial markets, and speculation thereof, futures had become profitable and risk a lucrative business. The future began bleeding into the present, by being carved at the joints – and thus made tangible and tradeable – by Cardano’s seismic innovation.

By this time, moreover, worldly time was swelling beyond the bookends prescribed by apocalyptic prophecy. The promised end kept failing to arrive. The more the years continued to accumulate, and the more frustrated their apocalyptic conclusion became, the more there could arrive a growing sense of the autonomy of secular history from divine dictatorship. As apocalyptic expectation became increasingly frustrated, that is, worldly time began to seem increasingly untouched by orchestrations from beyond.

This fed into, and was fed by, building conviction that genuinely unprecedented things were being invented and wrought by human agency and activity. History seemed on the move, with human ingenuity – rather than divinity – increasingly with its hands on the rudder. This led some to begin asking, in new ways, where they stand within this story. None other than Gerolamo Cardano, writing around 1570, remarked that his position in the generations seems improbable given he appeared to have been born during an uncommonly pacey time of innovation: wherein printing, gunpowder, and the compass had all become widespread in Europe.Footnote 69

But many Renaissance thinkers continued to assume that, though there might be local direction to human history – applying within one’s nation or continent – there may be only aimless cycling and recurrence at the level of the globe. They tended to assume that all novel inventions had already been invented elsewhere and elsewhere, and, by implication, will be discovered again should their civilisation be lost or forgotten. Again, there was not yet the evidence sufficient to disprove this: in absence of a global fossil record it remained underdetermined as to whether human history had a proper beginning such that it can admit of genuine novelties and irreversible transitions.

For example, in 1651’s Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes spoke of the shift from a warring ‘State of Nature’ to that of the ‘Social Contract’. This might now sound like what we understand as the transition from prehistory to history. We envision a time before which no humans, anywhere, practised farming or writing, and a time after which some started. But this wasn’t what Hobbes had in mind. He clarified he believed the precivilisational state ‘was never generally so, over all the world’.Footnote 70

This betrays assumption that human history – at the level of the globe – could simply represent the cycling of a set of states simultaneously manifested in space, rather than a chronology of genuine firsts and lasts irreversibly punctuating time. A revolving, never a rupture. Regions might slither between states, but, from the global perspective, nothing genuinely novel ever happens or is permanently lost. Every ‘civilised’ region will have previously been in the ‘State of Nature’ and every wild region will previously have experienced ‘Social Contracts’, potentially without limit.

Hobbes’s view was far from unorthodox. Many other Early Modern thinkers also understandably erred cautiously when it came to the question of extremities to human history. Writing in his 1513 Discourses, Machiavelli again entertained the possibility there have been countless human civilisations, its just the records of them have been ‘blotted out by various causes’. Like Plato before him, he endorsed a cyclical view wherein civilisation repeatedly grows to a certain point – that is, ‘when human craft and malice have gone as far as they can go’ – before everything is destroyed, clearing the way for a reset.Footnote 71

Various commentators remarked that, though new things appeared to be being invented, they couldn’t disprove lingering suspicion all these feats hadn’t already been innumerably achieved before – by forgotten civilisations, in unknown regions, throughout time immemorial.

Accordingly, by the Early Modern period, the Horizon of Contingency still didn’t extend far beyond one’s landmass or continent. Nonetheless, this didn’t deter growing feeling that human ingenuity – rather than divine dictatorship from the heavens – seemed, increasingly, to be steering history’s course. So, too, did a suspicion begin building that time is open-ended: that is, that it can take various different tracks, depending on accident and agency flowing from human affairs.

So mused the French polymath Blaise Pascal sometime around 1650: had ‘Cleopatra’s nose’ been different, making her less attractive, then ‘the whole face of the earth would have been different’.Footnote 72 That is, should Mark Antony not have fallen for Cleopatra’s distinctive visage, subsequent events would have also been unrecognisable. With this clever quip – bundled with a pleasing pun – Pascal captured an emerging, very modern attitude towards time.

We may be accustomed to such counterfactual conjectures at global scale now; back then, however, they were newfangled. Our grasp of history’s contingencies, and of the future’s forking paths, has continued growing ever since: an ever-expanding halo of unrealised possibilities fanning out from the merely actual.