1 Introduction

Existing institutions are deeply challenged by many long-standing and emerging changes in contemporary political life. This leads to weaknesses and failures that are being increasingly witnessed across a variety of domains. In particular, climate change stands out as a manifest example, given the urgent need for climate action across the globe. We need to understand how existing institutions can be “remade” in order to address institutional breakdown, particularly in the domestic political sphere. Yet, doing so requires developing a suitable analytical foundation for studying institutional intervention as a political endeavor.

This Element develops an original approach to understanding how political systems can move beyond institutional failure in turbulent but gridlocked contemporary governance contexts. It does so by investigating the political dynamics that occur during attempts to remake political institutions, considering multiple coexisting “areas of institutional production.” The notion of remaking institutions is proposed as a way of apprehending the intentional and ongoing work involved in contesting, rethinking, and redeploying institutions, and the challenges of doing so within complex existing institutional settings. Thereby, it emphasizes the unfolding and open-ended character of such activities, which are often, as a result, provisional and indeterminate. An exploratory conceptual argument is presented, which probes existing theory and empirical experience (drawing on climate change as an illustrative example), to develop an analytical foundation for studying institutional remaking.

Importantly, the practice of institutional remaking is not in itself a new phenomenon; it is of course the reality of institutional life that intentional changes are almost always pursued within a historical context as well as a larger system of cognate rules. However, what is lacking is appropriate conceptualization of what exactly occurs during such processes, particularly when end states are not necessarily known a priori, or are sharply contested (or both). This issue takes on particular significance in the context of multiplying institutional weaknesses and failures in contemporary society, as well as the (often urgent) imperative for prospective improvement looking forward into the future.

1.1 Institutions in a Changing World

Institutions provide stability for political affairs, but in a rapidly changing world, we increasingly expect institutions to change in order to cope with new pressures, and even anticipate new challenges. Climate change brings this problem into stark relief, as institutions of domestic and global politics are central for not only enabling wise societal decision-making in the face of unprecedented (and even existential) threat, but are also themselves undermined by the changing circumstances brought about by climate change, which are beginning to reverberate throughout human societies. For example, climate impacts threaten not only lives, infrastructure, and ecosystems but also property rights, social stability, and faith in politics. Elsewhere, institutional shortcomings are also at the center of many other major issues facing societies across the globe, such as migration, economic change, digitization, and aging societies. Altogether, these issues expose weaknesses and failures in contemporary political systems that seem increasingly incapable, and often were simply not built for, the new and emerging pressures they now face. Yet, understanding how political institutions can be reformed, renewed, and reinvented – in other words, “remade” – is a major challenge.

1.2 The Case of Climate Change

In the case of climate change, political institutions are central to addressing and responding to the profound risks posed. Scientists and policymakers argue evermore strongly that societies must embark on major reorganizations – commonly described as “societal transformations” – in order to mitigate and adapt to climate change (IPCC, 2018; NCE, 2018; Reference Patterson, Schulz, Vervoort, van der Hel, Widerberg, Adler, Hurlbert, Anderton, Sethi and BarauPatterson et al., 2017; Reference PellingPelling, 2011; Reference Scoones, Leach and NewellScoones et al., 2015). This is especially vital for constraining temperature rises to globally agreed targets of 1.5–2°C, beyond which unstoppable or runaway climate impacts are likely to be triggered.Footnote 1 It requires “decarbonizing” systems of production and consumption across all sectors and levels of human activity, and adapting social, political, and economic systems to fundamentally shifting boundary conditions in a climate-changed world. Such transformations may relate to a particular goal (e.g., decarbonization, adaptation), policy sector (e.g., energy, mobility, water, food, built environment), or aspect of society (e.g., technology, economy, culture). As climate change impacts grow in magnitude and severity across the globe, these impacts themselves are likely to become a structural cause of transformation in human societies, at the same time as being driven by human societies. This leads to a curious situation where societal transformation is now bound to occur one way or another: Either transformation is pursued intentionally in order to limit and curtail climate change or transformation is forced on societies as a result of failing to limit climate change with profound disruption triggered as a result (Reference Fazey, Moug, Allen, Beckmann, Blackwood, Bonaventura, Burnett, Danson, Falconer, Gagnon, Harkness, Hodgson, Holm, Irvine, Low, Lyon, Moss, Moran, Naylor, O’Brien, Russell, Skerratt, Rao-Williams and WolstenholmeFazey et al., 2018).

However, while intentional transformations are urgently called for,Footnote 2 understanding how they may come about – beginning from the imperfect conditions of the present and in the face of often intense contestation – is deeply challenging. Among scholars, the focus so far has mostly been either, on the one hand, describing problems and the need for transformation or, on the other hand, advocating normative visions for a sustainable future. However, the processes of change by which such transformations could actually be realized remain vastly under-theorized, a gap that is especially significant for institutions given their central role in structuring political decision-making.

The problem structure of climate change creates a vexing political challenge. The diffuse nature of climate change impacts across societies and over time, as well as the dilemma that rapid and ambitious climate action requires societies to accept concentrated costs now in exchange for avoiding uncertain and dispersed costs in the future, has proven to be a critical barrier to domestic climate change action over decades (Reference JacobsJacobs, 2016; Reference StokesStokes, 2016; Reference VictorVictor, 2011). Crucially, this is not just a question of aggregate interests, preferences, and social choice. It is also rooted more fundamentally in the political institutions that structure and channel political decision-making. Political institutions that are implicated include not only those specifically concerned with climate change governance but also broader political institutions that influence social choices about climate change. The resulting sets of incentives/sanctions, norms/goals, and practices/behaviors cultivated by political institutions shape the ways in which societies make decisions and conduct climate action.

Realizing societal transformations under climate change, therefore, involves changes in political institutions in response to, as well as in anticipation of, climate change destabilization. For example, Reference Hausknost and HammondHausknost and Hammond (2020, p. 4) argue that “a rapid, purposeful, and comprehensive decarbonization of modern society without the force of law and without adequate institutions of deliberation, will-formation, decision-making, policy coordination, and enforcement seems highly unlikely.” Changes in political institutions are needed in three key areas:

1. Political institutions in a given society need to adapt to changing circumstances, including material-environmental boundary conditions and their related social, economic, and geopolitical impacts.

2. “Specific” political institutions of climate change governance (e.g., policies, programs, law/regulation) need to support anticipatory climate action that is rapid and ambitious.

3. “General” political institutions (e.g., policy-making processes, legislatures, systems of representation and deliberation, authorities, constitutions) need to support long-term decision-making capable of addressing systemic challenges and avoiding short-termism.

The first point concerns primarily reactive changes to develop institutions that are fit for purpose within profoundly changing circumstances. The second and third points concern anticipatory changes to develop institutions that are fit for navigating the future. The key question, of course, is how such changes can be realized.

1.3 “Remaking” Institutions

The need to remake institutions in a rapidly changing world is a core challenge for contemporary governance. For example, Reference BusbyBusby (2018) observes that “the world seems to be in state of permanent crisis,” which brings issues of institutional weakness and failure to the forefront of debates about how societies may cope with ongoing disruption. Yet, while institutional shortcomings are increasingly identified, scholars and policymakers alike seem equally puzzled about how solutions may be found and realized.

Climate change impacts are already occurring with increasing intensity and frequency,Footnote 3 including extreme floods, droughts and hurricanes, more severe and widespread wildfires, and rapidly melting glaciers in mountain regions across the globe. Yet climate change governance, both domestically and globally, remains sluggish. Second-order pressures on institutions are also likely due to destabilization of societal and political systems, such as in regard to loss of property rights (Reference Freudenberger and MillerFreudenberger and Miller, 2010; Reference McGuire, Zavattaro, Peterson and DavisMcGuire, 2019), impacts on health (Reference Sellers, Ebi and HessSellers et al., 2019; Reference Whitmee, Haines, Beyrer, Boltz, Capon, de Souza Dias, Ezeh, Frumkin, Gong, Head, Horton, Mace, Marten, Myers, Nishtar, Osofsky, Pattanayak, Pongsiri, Romanelli, Soucat, Vega and YachWhitmee et al., 2015), disrupted global supply chains (Reference Ghadge, Wurtmann and SeuringGhadge et al., 2020), forced migration (Reference Berchin, Valduga and GarciaBerchin et al., 2017), contribution to intra- or inter-state conflict (Reference Devlin and HendrixDevlin and Hendrix, 2014; Reference GleickGleick, 2014; Reference Nardulli, Peyton and BajjaliehNardulli et al., 2015), impacts on access to food (Reference Ericksen, Ingram and LivermanEricksen et al., 2009), new geopolitical tensions (Reference BusbyBusby, 2018; Reference Hommel and MurphyHommel and Murphy, 2013), and even an erosion of trust by citizens in democratic political systems themselves due to the failure of governments to tackle climate change over many years (Reference Brown, Adger and CinnerBrown et al., 2019).

Institutional challenges also abound beyond climate change. For example, irregular migration has tested global systems of migration and human rights protections in recent years, as global conflicts and/or repressive regimes have triggered waves of refugee movements, with sometimes volatile political reactions such as rising populist sentiments. In Europe, for example, current arrangements allocating responsibility for sharing refugee arrivals are tenuous, and further stresses (including as a result of climate impacts) could be untenable (Reference Werz and HoffmanWerz and Hoffman, 2016). More broadly, economic insecurity of citizens is a growing source of anxiety in many countries, linked to both domestic economic policies and global economic changes, such as economic restructuring over decades under globalization (e.g., offshoring of jobs, deindustrialization, automation), raising questions about the durability of labor and social welfare institutions (Reference BregmanBregman, 2018; Reference WrightWright, 2010). Additionally, aging societies create large slow-moving future challenges with growing mismatches between state pension liabilities and the productive base of workers needed to sustain them, especially in many industrialized countries, which has implications for social security and healthcare institutions (Reference BloomBloom, 2019; Reference de Mooijde Mooij, 2006). Together, this indicates a critical need to understand how institutions in many areas of political affairs can be intentionally remade over the coming years and decades.

Yet, while institutional solutions are needed for many problems, exactly how such solutions can be realized in practice – even when prescribed – is not well understood. Most broadly, institutions refer to “the rules of the game in a society”Footnote 4 (Reference NorthNorth, 2010, p. 3), “established and prevalent social rules that structure social interactions” (Reference HodgsonHodgson, 2006, p. 2), or “persistent rules that shape, limit, and channel human behavior” (Reference FukuyamaFukuyama, 2014, p. 6). More specifically, institutions are defined as “clusters of rights, rules and decision-making procedures that give rise to social practices, assign roles to the participants in these practices, and guide interactions among occupants of these roles” (Reference Young, King and SchroederYoung et al., 2008, p. xxii). In other words, institutions refer to the rules mediating interactions among actors in a given decision-making arena,Footnote 5 including both formal and informal aspects (Reference OstromOstrom, 2005). Importantly, such rules are not solely instrumental but are also “embedded in structures of meaning” (Reference March, Olsen, Rhodes, Binder and RockmanMarch and Olsen, 2008, p. 3) and communication (Reference Patterson, Betsill, Gerlak and BenneyBeunen and Patterson, 2019; Reference SchmidtSchmidt, 2008). Hence, cultures, routines, and habits also matter (Reference HodgsonHodgson, 2006; Reference March and OlsenMarch and Olsen, 1983). The overall effect of political institutions is to channel individual and collective agency of social actors, and structure procedures of political decision-making. However, institutions are typically understood to be complex, persistent, and difficult to intentionally change. Indeed, by definition, institutions provide stability and emerge from past circumstances, which make them inherently conservative.

What does this mean for remaking institutions to address climate change and other twenty-first-century governance problems? First, it is important to note that intentional action to remake institutions may be pursued at different levels of institutional order.Footnote 6 This can include a programmatic level (e.g., policies, plans, agreements), a legislative level (e.g., laws, regulations), and a “constitutional” level (e.g., formal constitutions, courts, electoral and representative systems, fundamental political norms) (following Reference OstromOstrom, 2005; Reference Rhodes, Binder and RockmanRhodes et al., 2008). Action at each respective level may be more or less readily achievable: Programmatic actions are typically easier to realize than legislative action, whereas constitutional action is typically difficult and rare. Changes at each level may also proceed over differing timescales (e.g., years, decades, several decades). Second, attempts to realize intentional institutional change are not only instrumental but also normative and communicative. For example, political justifications, argumentation and legitimation (Reference BeethamBeetham, 2013), and buy-in between rule takers and rule enforcers are vital for securing durable changes. Third, institutions are connected to other aspects of society, such as behaviors and practices of social actors, and materiality of technologies and infrastructures (Reference Seto, Davis, Mitchell, Stokes, Unruh and Ürge-VorsatzSeto et al., 2016). For example, Reference Bernstein, Hoffmann, Jordan, Huitema, van Asselt and ForsterBernstein and Hoffman (2018a, p. 248) point out that decarbonization (i.e., the removal of fossil fuels from all systems within society) confronts the problem of “carbon lock-in,” which “arises from overlapping technical, political, social, and economic dynamics that generate continuing and taken-for-granted use of fossil energy.” Hence, attempts to intentionally change institutions, even when geared toward solving pressing societal problems such as climate change, inevitably involve political contestation and struggle in heterogeneous societies where different social actors hold varying preferences, interests, values, and worldviews. Consequently, for socio-technical shifts such as decarbonization, the ways in which new systems come to be adopted depends on “how they are assembled and congealed through particular arrangements” (Reference Stripple and BulkeleyStripple and Bulkeley, 2019, p. 54), in other words, institutions.

1.4 Domestic Political Sphere

The domestic political sphere (encompassing national, subnational, and local climate action) is crucial to realizing societal transformations to meet global climate targets. Current global climate policy relies on nations delivering on their commitments made under the 2015 Paris Agreement. Under this agreement, nations are expected to set commitments and undergo reviews on a cyclical basis, to support progressive ratcheting up of ambitions over time, while allowing scrutiny from other nations and civil society along the way (Reference FalknerFalkner, 2016). Consequently, the success of global climate action now depends on robust action in the domestic political sphere to translate global commitments, navigate complex societal changes, and advance ambitious climate action.Footnote 7 At the same time, the domestic sphere is where climate policies are most directly enacted but also challenged. For example, climate policies may be accepted by societies, but they also may face intense resistance or even backlash (e.g., undermining or repealing of policy, institutional dismantling, social protests, and resistance). Importantly, the domestic (sovereign) sphere is where the authority and capability for remaking many political institutions are ultimately grounded.

Institutional remaking already occurs, or is at least debated, in a variety of ways in domestic politics. Examples include the creation of comprehensive policy frameworks (e.g., measures to structurally support the uptake of renewable energy) (Reference BuchanBuchan, 2012), regulation to steer public and private choices (e.g., planning and zoning, building standards, vehicle emissions standards) (Reference SachsSachs, 2012), sectoral and society-wide legislation (e.g., climate change acts, legislated targets for decarbonization, ratification of national emissions reduction commitments) (Reference Lorenzoni and BensonLorenzoni and Benson, 2014), creation of new authorities (e.g., agencies/departments, coordination bodies, independent advisory agencies) (Reference Lorenzoni and BensonLorenzoni and Benson, 2014; Reference Patterson, Voogt and SapiainsPatterson et al., 2019), economic restructuring (e.g., active investment policies, removal of fossil fuel subsidies)Footnote 8 (Reference Brown and GranoffBrown and Granoff, 2018), experimentation with new forms of decision-making (e.g., deliberative forums) (Reference Dryzek, Bowman, Kuyper, Pickering, Sass and StevensonDryzek et al., 2019), and the emergence of climate litigation and its institutional consequences (Reference Peel and OsofskyPeel and Osofsky, 2018; Reference SharpSharp, 2019). These changes span the three imperatives for remaking institutions under climate that were identified in Section 1.1 (i.e., adapting to changing structural conditions, supporting ambitious climate action, and encouraging comprehensive and long-term political decision-making).

More broadly, intentional efforts to “remake institutions” can also be seen in other domains of political life, both past and present. For example, economic liberalization has been pursued through domestic and global policies over several decades, and domestic spheres have in turn been reshaped by the resulting forces of globalization. Labor, social welfare, agriculture and tax policies have been other major areas of reform and restructuring over recent decades. Democratization has also occurred in a variety of countries (e.g., post-soviet, post-dictatorship, post-conflict). All these changes involve intentional activities to remake political institutions. So far, profound reforms have largely not been emulated for climate change, where institutional remaking has remained relatively nascent. Yet climate change differs from previous analogues because it, at least so far, lacks a singular normative objective which a durable majority of social actors buy into (e.g., as for democratization or liberalization), and it is also highly open-ended without a clear end point for reforms. Lessons from the study of policy reform are also instructive. In examining the post-adoption politics of policy reforms, Reference PatashnikPatashnik (2014) argues that “the passage of a reform does not settle anything” and the “sustainability of reforms turns on the reconfiguration of political dynamics” (p. 3, emphases in original). Hence, contestation is central to both introducing but also embedding institutional changes over time. This brings attention to the provisional and indeterminate character of institutional change, and the ongoing political struggles that it entails.

1.5 Focus of This Element

This Element investigates the political dynamics that occur during attempts to remake political institutions, through considering multiple coexisting “areas of institutional production.” This begins with viewing institutional intervention as an ongoing political activity, rather than a once-off intervention moment (especially under climate change), which has several implications. First, political institutions act as distributional instruments which generate sites of contestation, leading to a focus on “rule-making” rather than only “rule-taking.”Footnote 9 Second, institutional remaking is an unfolding process, which may often lack a clear start and end point (e.g., end states are not necessarily known a priori), which implies a need for studying unfolding processes rather than snapshots. Third, given its provisional and indeterminate nature, evaluation of the “success” of institutional remaking at any given moment must recognize partial and incomplete outcomes.

Most broadly, this Element contributes to understanding how societies pursue and realize societal transformations through choice rather than collapse. In other words, how can solutions to institutional problems be found proactively without waiting for catastrophic failure? The problem of climate change is unprecedented in this regard.Footnote 10 It demands that societies act in anticipatory ways to take account of systemic, irreversible, and largely future impacts, which extend far beyond any single existing polity. As prominent institutional scholars Reference March, Olsen, Rhodes, Binder and RockmanMarch and Olsen (2008, p. 12) observe: “In spite of accounts of the role of heroic founders and constitutional moments, modern democracies also seem to have limited capacity for institutional design and reform and in particular for achieving intended effects of reorganizations.” Consequently, “we know a lot about polities but not how to fix them” (Reference NorthNorth, 2010, p. 67). Yet the importance and urgency of addressing climate change can hardly be overstated. Decisions made now are immensely consequential for the future, in a way that overwhelms existing political institutions and defies easy analogy. The challenge of remaking political institutions is both instrumentally and normatively significant. The overall motivation and theoretical terrain for studying institutional remaking, with a focus here on climate change, are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Situating the theoretical challenge of remaking institutions under climate change

Theoretically, we have rich repertoire of institutional theory to draw on, including a growing range of approaches for explaining institutional change. Nevertheless, our understanding of how institutions can be intentionally remade remains opaque. Institutional theory is typically backward looking as it focuses on explaining past changes (e.g., comparative historical analysis). There is often also a mismatch between narrow empirical explanations (e.g., focusing on single rules) and the reality of institutional multiplicity within real-world decision-making arenas (i.e., complex clusters of rules). Scholars now need to engage with theorizing how institutional solutions are, or could be, enacted within complex and nonideal real-world settings.

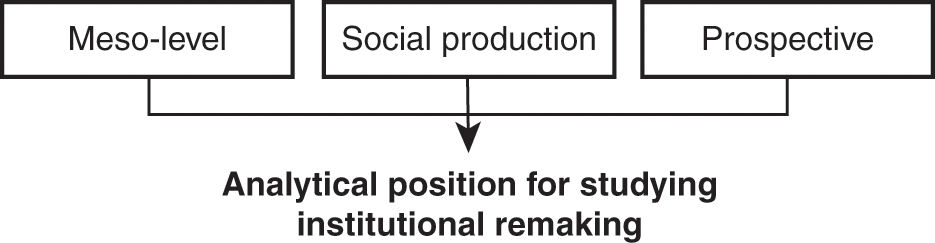

To this end, the departure point for the approach developed here combines: (i) a meso-level scalar focus, (ii) a social production ontology, and (iii) a prospective temporal orientation (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Analytical positioning of the approach to studying institutional remaking

First, a meso-level scalar focus refers to concern for rule clusters structuring collective decision-making arenas, over timeframes of several years to a decade. It contrasts against a micro-level perspective focusing on the dynamics of individual social actors operating on a day-to-day timeframe and a macro-level perspective focusing on large institutional changes over decadal timeframes; yet it nonetheless recognizes the influence of both micro- and macro-level forces. Micro-level forces (such as change agents) and macro-level forces (such as overarching political structures and paradigms) may both influence meso-level institutional remaking. A meso-level perspective also focuses on institutions and their interactions with human-technological-ecological systems within a polity that has the ability to reshape these institutions to some meaningful extent. For example, such a polity may be delineated at the level of a city, state/province, or a nation. Overall, this challenges us to focus on change in aggregate rule clusters linked to a particular issue.

Second, a social production ontology focuses on the activities through which social actionFootnote 11 is generated in attempts to address a specific problem. In other words, it locates the analytical challenge at hand as one of understanding how, why, and under which conditions institutional remaking occurs. The notion of social production has been described in urban governance literature as “the power to accomplish tasks” (Reference Mossberger and StokerMossberger and Stoker, 2001, p. 829), where “the power struggle concerns, not control and resistance, but gaining and fusing a capacity to act – power to, not power over” (Reference StoneStone, 1989, cited in Reference Stoker and MossbergerStoker and Mossberger 1994, p. 197). Hence this perspective reflects a conception of power as generative. Reference PartzschPartzsch (2017) identifies three ideal-type conceptions of power in sustainability transformations: “power with” (cooperation, learning, coaction), “power over” (coercion, manipulation, domination), and “power to” (resistance, empowerment, potential for action by certain agents). A social production perspective mainly aligns with a conception of “power to,” as it aims to understand processes of action and change (including resistance).

Third, a prospective temporal orientation refers to a focus on unfolding changes (i.e., both those that are “in-the-making” and those that “could be”) and how their future form is shaped by actions in the present. This includes understanding contemporary and past dynamics, which set certain trajectories of change in motion and/or constrain the potential for future changes. Such a perspective challenges institutional scholars to think about how it may be possible to prospectively address complex societal problems. This is vital for understanding how social and political changes, and ultimately transformations, might come about in practice. Crucially, this is not about advocacy, but about analytically understanding how a particular institutional change deemed desirable by certain social actors might be realized. If elucidating the nature and effects of institutions is a “first order” problem and explaining institutional change is a “second order” problem (following Reference Hall, Mahoney and ThelenHall, 2010), then understanding prospective institutional improvement might usefully be seen as a “third order” problem for institutional scholarship.

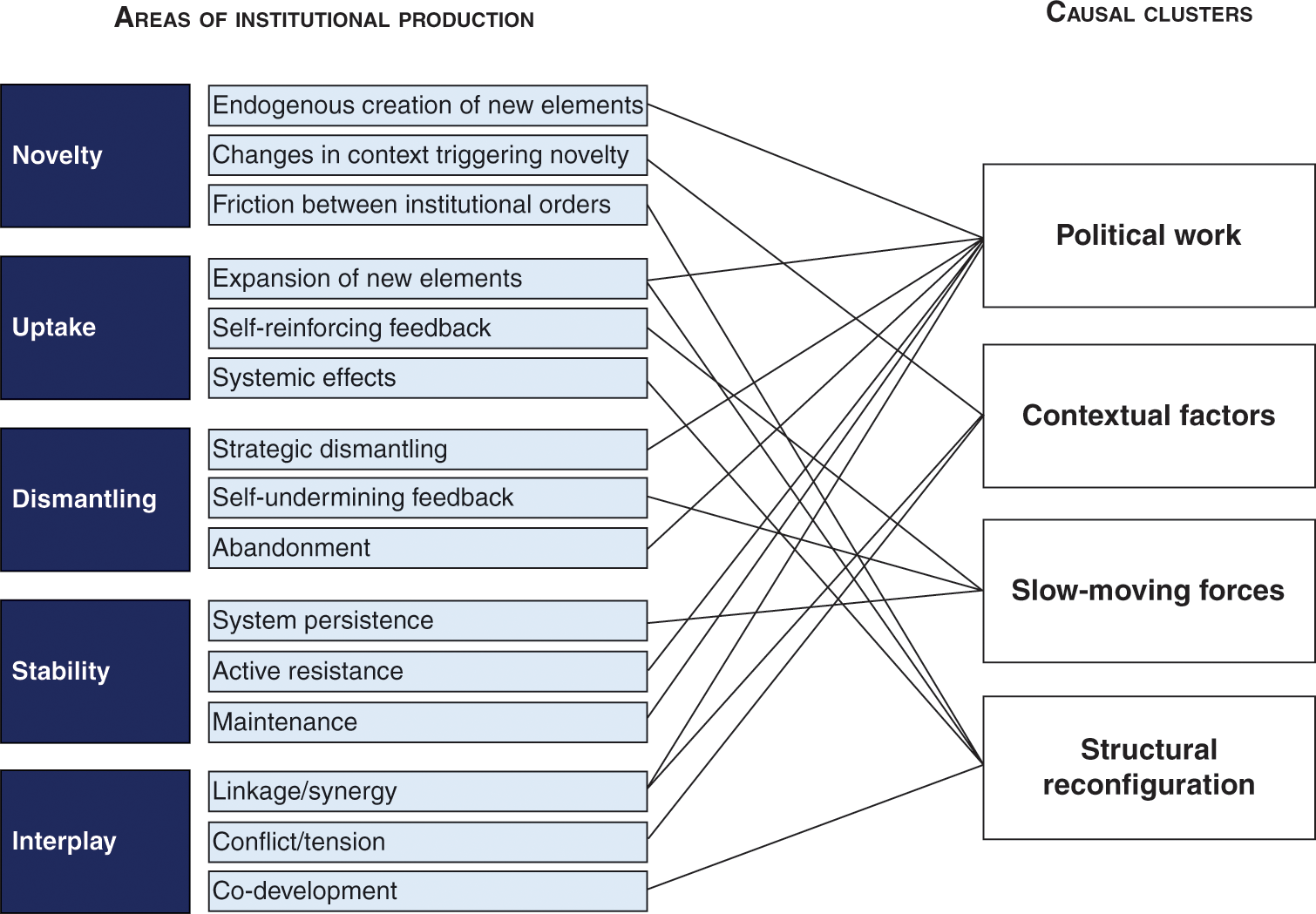

From this tripartite starting point, this Element develops an original approach to understanding how political systems can move beyond institutional failure in turbulent but gridlocked contemporary governance contexts. It develops an analytical foundation for studying institutional remaking and its political dynamics, including (i) an evaluation frame to observe institutional remaking and (ii) a heuristic typology comprising multiple key areas of institutional production expected to occur within processes of institutional remaking (i.e., novelty, uptake, dismantling, stability, and interplay). The approach draws on scholarship from political science, environmental studies, and sociology, and fields of research spanning institutional analysis, environmental governance, and sustainability transformations. Altogether, this opens up a new research agenda on the politics of responding to institutional breakdown, to support scholars in finding institutional solutions to contemporary governance problems. It also brings sustainability scholarship into closer dialogue with broader lines of thinking about processes of institutional change and development.

1.6 Overall Argument

The overall argument of this Element is that we need to better understand the processes by which political institutions are remade vis-à-vis weaknesses and failures in order to address many urgent challenges such as climate change. A key challenge is to probe prospective institutional development in order to not only explain (past) political change, but also to contribute to finding constructive (future) solutions to real-world problems. Political science typically focuses on explaining changes which have already occurred, rather than considering how future changes (and especially improvements, however conceived) might, or could, come about.Footnote 12 To engage with future developments often invokes ideas about design, foresight, and anticipation which – while practically useful and theoretically rich – tend to view the future through a metaphor of pathways to be pursued or avoided, arguably implying undue consensus and knowability. An alternative approach, as developed here, is to focus on the production of social action in the present, situated within a broader historical trajectory of past experience and future possibility, anchored in unfolding activities that shape the form and directionality of future outcomes.

This locates the problem of institutional remaking as one of understanding how intentional intervention is generated through interactions among a multiplicity of actors within complex institutional arenas. Institutional remaking involves political jockeying and struggle and is entangled with heterogeneous societies, material infrastructures, and changing environmental conditions. Studying it involves grappling with unfolding processes and partial outcomes; accepting that it is, in the fullest sense,Footnote 13 ongoing and in-the-making rather than a discrete event. This may be uncomfortable analytical territory for scholars seeking bounded, testable short-term relations. However, there is no inherent reason why institutional remaking cannot be studied from a variety of methodological standpoints, leaning toward theory-testing or theory-building, qualitative/interpretive or quantitative/objective analysis, and exploratory or explanatory reasoning. But to begin with, we must first develop a robust analytical foundation, which is the task of this Element.

The structure of the argument is as follows. Section 1 introduces the notion of institutional remaking and the need for it, both in regard to climate change and more broadly, and outlines key starting points for the argument. Section 2 elucidates pressures on institutions along with barriers to change and synthesizes current thinking about how and why institutional change occurs, which highlights the need for a focus on institutional remaking. Section 3 defines and delineates institutional remaking, situating it as a processual phenomenon, and reflecting on the role of intentionality and how this differs compared to institutional design. Section 4 develops a comprehensive frame for observing and evaluating institutional remaking. Section 5 develops a heuristic typology comprising five key areas of institutional production that are expected to play out during processes of institutional remaking, drawing on both sustainability governance and institutional theory. Section 6 identifies insights about processes of intentional institutional change, contributions to broader institutional theory, and research priorities. Section 7 concludes with distilling the overall contributions of the argument.

2 Institutional Pressure, Institutional Change?

Contemporary political institutions experience growing pressures, and yet they do not automatically adjust to cope with these pressures. A variety of barriers to institutional change occur. In response, the topic of institutional change has been an area of major interest among scholars in recent years, with a variety of insights put forward by different communities. However, this is not fully sufficient to understand how institutions can be (intentionally) remade.

2.1 Pressures on Contemporary Institutions

The problem of institutional weakness and/or failure, on climate change as well as a range of other issues, is a core motivation for studying institutional remaking. Here, institutional weakness and/or failure refers to the inadequate performance of actually existing institutions for addressing a certain issue confronting society. For example, in environmental governance, Reference Newig, Derwort and JagerNewig et al. (2019) identify empirical examples of institutional failure including institutional deficiencies contributing to environmental pollution incidents, costly performance of endangered species legislation, and inadequacy for decarbonizing electricity production. In the context of political decentralization reform, Reference Koelble and SiddleKoelble and Siddle (2014) identify examples of institutional failure such as lacking municipal service delivery and democratic deficit due to mismatched municipal capacity. More broadly, Reference PetersPeters (2015) identifies governance failures characterized by poor cooperation either among political elites or between bureaucracies, particularly in the face of issues that are sectorally crosscutting, long term, and/or containing entrenched ideological aspects, which result in “either limited governance outputs, or outputs that are incapable of addressing more than a portion of the problem confronting the public sector and the society” (pp. 263–264). Reference Prakash and PotoskiPrakash and Potoski (2016, pp. 118–120) classify several types of institutional failure: failures of design (where the initial setup is unsuitable to regulate the problem), mismatch and obsolescence (where new or altered actors evade existing regulation), failure to adapt (where institutions remain too static over time), and capture (where certain actors gain undue influence over regulation).

Yet a variety of contemporary pressures on political institutions suggest that these risks are unlikely to dissipate anytime soon and in fact are only likely to grow. Such pressures include political stagnation, shifting environmental boundary conditions, and burgeoning societal heterogeneity.

First, scholars highlight worrying patterns of political stagnation in recent years. This is described in a variety of ways, including as gridlock and political decay. For example, at a global level, scholars observe gridlock on a variety of transborder problems (e.g., climate change, trade, finance) hindering global problem-solving (Reference Hale, Held and YoungHale et al., 2013). At a domestic level, the historical development of core political institutions now points toward decay in some countries such as the United States linked to fragmentation, polarization, and abundant opportunities for veto, calling into question the ability of such systems to function effectively (Reference FukuyamaFukuyama, 2014). Furthermore, rising populism in many countries in recent years (e.g., Reference Norris and InglehartNorris and Inglehart, 2019; Reference Schaller and CariusSchaller and Carius, 2019) has implications for climate change. For example, critiques of cosmopolitanism may make it harder to generate public support for ambitious climate action since benefits are questioned, and due to a lack of trust that other countries are also taking commensurate action, even despite the presence of the Paris Agreement as a global coordination arrangement. On the other hand, lack of climate action could erode trust in democratic political systems over time, due to failure of governments to meaningfully address climate change (Reference Brown, Adger and CinnerBrown et al., 2019).

Second, the impacts of climate change are many and varied across global and local geographies, including exposure to climate disasters (e.g., droughts, floods, wildfires, heatwaves) and long-term climate shifts (e.g., changing patterns of rainfall, sea level, and temperatures), and their interaction with human systems (e.g., cities, agriculture, infrastructures). These changes are ongoing and nonlinear. Seemingly small changes may produce large effects (e.g., small changes in atmospheric moisture may have major impacts on the likelihood of floods or droughts). Altogether, this results in shifting environmental boundary conditions for human societies, a problem that has been labelled “nonstationarity.” Nonstationarity refers to underlying shifts in long-term climate patterns (i.e., mean, variance), which implies that expected conditions upon which political institutions have developed over decades, and even centuries, no longer apply (Reference CraigCraig, 2010; Reference Milly, Betancourt, Falkenmark, Hirsch, Kundzewicz, Lettenmaier and StoufferMilly et al., 2008). Political institutions linked to the production and distribution of resources and even basic rights are threatened. For example, property rights may become devalued or untenable (e.g., water, land, infrastructures) (Reference Freudenberger and MillerFreudenberger and Miller, 2010; Reference McGuire, Zavattaro, Peterson and DavisMcGuire, 2019). Implications for political stability are unknown and undoubtably troubling.

Third, societal heterogeneity in contemporary human societies (e.g., in terms of interests, preferences, beliefs, values) deeply challenges the ability of political systems to respond to complex problems such as climate change. Diverging political demands and reactions to policy proposals, and fragmented and polarized public opinion make far-sighted political renewal seem almost like an anachronism in contemporary politics. At the same time, governance itself becomes increasingly multiple. For example, there are now a wide range of non-state and subnational actors involved in climate change governance across domestic, transnational, and global spheres (Reference AbbottAbbott, 2012; Reference Bulkeley, Andonova, Betsill, Compagnon, Hale, Hoffman, Newell, Paterson, Roger and VandeveerBulkeley et al., 2014; Reference Chan, van Asselt, Hale, Abbott, Beisheim, Hoffmann, Guy, Höhne, Hsu, Pattberg, Pauw, Ramstein and WiderbergChan et al., 2015; Reference HaleHale, 2016). Some lines of thinking emphasize difficulties of fragmentation that can result (Reference Biermann, Pattberg, van Asselt and ZelliBiermann et al., 2009; Reference Zelli and van AsseltZelli and van Asselt, 2013). On the other hand, scholars within a pluralist tradition view heterogeneity as a social fact (Reference AligicaAligica, 2014). In this line, the notion of polycentricity has been taken up recently to try to make sense of dispersed centers of authority in climate change governance (Reference Jordan, Huitema, van Asselt and ForsterJordan et al., 2018). Such a view would suggest that institutions are potentially remade in diverse and interdependent ways within complex institutional arenas. Yet it also raises questions about the performance of institutions “in an increasingly interdependent world of diverse and conflicting views, beliefs, preferences, values, and objectives” (Reference AligicaAligica, 2014, p. xiv).

2.2 Barriers to Institutional Change

Despite the pressures identified in Section 2.1, institutions are unlikely to adjust automatically to new circumstances and objectives. Institutions are embedded in historical, political, cultural, and material/environmental settings. The weight of the past constrains change because patterns of coordination in political systems tend to persist over time. Institutional change is also typically contested and may be driven by endogenous actors (Reference Mahoney and ThelenMahoney and Thelen, 2010), rapid and slow-moving external forces (Reference PiersonPierson, 2004), and friction with neighboring institutional orders (Reference Orren and SkowronekOrren and Skowronek, 1996). As a result, a variety of barriers to institutional change arise, including path dependency, inefficiency, materiality, and opportunity structures (Table 1). Sustainability scholars typically emphasize path dependency and materiality, while institutional scholars typically emphasize path dependency, inefficiency, and opportunity structures. Climate change brings all four into focus.

Table 1 Barriers to institutional change

| Barrier | Description | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Path dependency | Commitments and incentives lead actors to maintain status quo | Institutions develop mechanisms that reinforce their own stability |

| Inefficiency | Weak mechanisms of competition, learning, and adaptation | Institutions are inefficient at adjusting to changing circumstances and objectives |

| Materiality | “Lock-in” of institutions due to socio-material linkages | Institutions are interconnected with environments, infrastructures, and practices |

| Opportunity structures | Heterogeneous and ephemeral opportunity structures | Institutions are not equally open to change in all areas or moments in time |

Perhaps the most commonly cited reason for a lack of institutional adjustment is that of path dependency. This explains how existing institutions contribute to creating incentive and payoff structures that tend to reinforce and perpetuate their own existence; societal actors reconfigure their expectations and capabilities and become invested due to accumulating benefits over time (Reference PiersonPierson, 2004). This creates a dynamic of “increasing returns” where benefits accumulate to actors who are already set up to take advantage of existing arrangements, the costs of switching paths are relatively high, and, therefore, early departure points have persistent consequences down the line (Reference PiersonPierson, 2000a). The reasons why this is difficult to overcome include coordination challenges for those defecting from the existing setup, veto points available at a more fundamental level than the particular arena in question, and commitments built up over time in relation to the current setup such as “relationships, expectations, privileges, knowledge of procedures” (Reference PiersonPierson, 2004, pp. 142–148). Yet, at the same time, the inherent “stickiness” conferred by institutions is helpful to social actors because it allows to “reduce uncertainty and enhance stability, facilitating forms of cooperation and exchange that would otherwise be impossible” (Reference PiersonPierson, 2004, p. 43). Thus, path dependency “is not a story of inevitability in which the past neatly predicts the future” (Reference PiersonPierson, 2004, p. 52) and “is not ‘inertia’, rather it is the constraints on the choice set in the present that are derived from historical experiences of the past” (Reference NorthNorth, 2010, p. 52). But altogether, it leads to strong commitments and incentives, especially among incumbent actors, to maintain the status quo.

In the face of path dependency, sustainability scholars often point to the potential for institutional change through mechanisms of competition, learning, and adaptation. However, these mechanisms have all been critiqued as weak in practice for various reasons. Competition is typically assumed to occur within and between decision-making arenas (e.g., cities, nations) over approaches to responding to climate change, a view that is rooted in an evolutionary economics frame. However, political institutions are rarely subject to competition in a classical sense since they “often have a monopoly over a particular part of the political terrain” (Reference PiersonPierson, 2000b, p. 488). Learning is typically assumed to occur within and between decision-making arenas through direct experience (e.g., climate change impacts, changes understood to be needed) or indirect experiences (e.g., observing other decision-making arenas), a view rooted in a sociological frame of interactive social action. However, the relation between new ideas (stemming from learning) and institutional change is not direct (Reference HallHall, 1993), and therefore learning is not synonymous with actual changes in governance but should be seen as a separate step (Reference PiersonPierson, 2000b, p. 490). Adaptation is typically assumed to occur when faced with changing circumstances (e.g., experienced or expected climate change impacts), a view rooted partly in a frame of rational response to problems, but also partly in a complexity frame that emphasizes the need for continuous adaptability within dynamic circumstances. However, there is no guarantee that actors will want to adjust to changing circumstances, especially when uncertainties or ambiguities afford cover for retaining existing political positions. Moreover, “because political reality is so complex and the tasks of evaluating public performance and determining which options would be superior are so formidable, such self-correction is often limited” (Reference PiersonPierson, 2000b, p. 490). Altogether, these inefficiencies mean that institutions do not automatically adjust to changing circumstances or societal objectives.

Sustainability scholars emphasize how institutions are closely bound up in assemblages comprising environments, infrastructure/technology, and practices/behaviors. For example, Reference YoungYoung (2010a) examines the dynamics of international environmental regimes from the perspective of interactions between endogenous factors and exogenous biophysical and socioeconomic factors, emphasizing their combined role in explaining regime performance. Reference OstromOstrom (2005, Reference Ostrom1990) famously developed a view of institutions as inherently bound up with environmental and social conditions, making clear the need to analyze these dimensions as a package. Elsewhere, the field of sustainability transitions is premised on inseparable links between people, infrastructures, and institutions. For example, Reference Andrews-SpeedAndrews-Speed (2016, p. 217) suggests that “the energy sector can be envisaged as a particular type of socio-technical regime comprising an assemblage of institutions which develop around a particular set of technologies and support the development and use of those technologies,” and Reference Stripple and BulkeleyStripple and Bulkeley (2019, p. 52) argue that “decarbonisation politics are socio-materially constituted.” Indeed, this is an area in which sustainability scholarship enriches broader institutional theory, which often tends to underplay the causal connections between institutions and their material/environmental context by focusing primarily on political and historical explanatory factors. Crucially, what this means is that institutions can be subject to “lock-in,” not only for endogenous reasons (such as path dependency and inefficient adjustment), but also because of relations with broader environmental-social-material factors (Reference Monstadt and WolffMonstadt and Wolff, 2015; Reference Seto, Davis, Mitchell, Stokes, Unruh and Ürge-VorsatzSeto et al., 2016; Reference UnruhUnruh, 2000).

Opportunities for institutional change are typically heterogeneous and ephemeral because of changes in the exogenous context, differences across levels of institutional order, and endogenous dynamism within institutions themselves. Abrupt changes in the exogenous context can impact an institution, as in the famous punctuated equilibrium model whereby radical institutional change occurs due to an exogenous shock (Reference Baumgartner and JonesBaumgartner and Jones, 2009). Related to this is the notion of a “window of opportunity” for intentional institutional change, which could be a shock or simply other political factors such as electoral cycles, changes in discourse, public mood, and domestic and international events that create moments of attention (Reference SabatierSabatier, 2007). On the other hand, changes in context can also occur gradually, leading to slow-moving shifts, which may not appear to be causally significant for long stretches of time until a threshold is reached where a seemingly sudden effect appears (Reference PiersonPierson, 2004), for example, socioeconomic or demographic changes that play out over long timeframes leading to changes in political constituencies and preferences. Across levels of institutional order (e.g., programmatic, legislative, constitutional) institutions are likely to show different degrees of durability and persistence over time (Section 1.3). For example, programmatic institutions may permit change over relatively short timeframes (e.g., several years), legislative institutions may permit change over longer timeframes (e.g., years to decades), and constitutional institutions may only permit change over even longer timeframes (e.g., decades to centuries). Moreover, rules at one level can be seen as “nested” in deeper rules (Reference OstromOstrom, 2005), which means that veto points or other forces of stability may be present at a deeper level than the level at which a particular change is sought. Yet scholars have recently argued that there is often much endogenous dynamism within institutions, which may not be immediately obvious, but which may permit ongoing gradual changes (Reference Mahoney and ThelenMahoney and Thelen, 2010). Yet this by no means implies complete flexibility for endogenous actors to reshape institutions, and they will often still be highly constrained. Altogether, this implies that even when subjected to pressures (Section 2.1), there are many reasons why institutions do not necessarily adjust accordingly.

2.3 Existing Theory on Institutional Change

Even though pressures on institutions do not automatically lead to institutional change, institutions do still change, sometimes intentionally and sometimes unintentionally. Indeed, the topic of institutional change has become prominent in recent years among not only institutional scholars (e.g., Reference Mahoney and ThelenMahoney and Thelen, 2010; Reference Streeck and ThelenStreeck and Thelen, 2005), but also sustainability scholars (Reference Patterson, Betsill, Gerlak and BenneyBeunen and Patterson, 2019; Reference Lorenzoni and BensonLorenzoni and Benson, 2014; Reference Patterson, Voogt and SapiainsPatterson et al., 2019; Reference YoungYoung, 2010a). Therefore, in building a foundation for studying how institutions can be remade, it is important to first interrogate what is known about institutional change and its mechanisms more generally.

When examining institutional change, scholars commonly look to agency-structure interplay, that is, the ways in which certain actors exert influence on institutional structures, and the ways in which institutional structures shape and condition the actions of agents. Indeed, Reference GoodinGoodin (1998) argues that the core argument of the overall “new institutionalist” paradigm, which emerged from approximately the 1980s onward in reaction to a behavioral paradigm,Footnote 14 is essentially “the recognition of the need to blend both agency and structure in any plausibly comprehensive explanation of social outcomes.” This overall new institutionalist paradigm continues as the foundation of contemporary institutional analysis, albeit in a variety of guises emphasizing different causal features (e.g., rational choice, historical, sociological, discursive variants), both in political science generally (e.g., Reference Hall, Mahoney and ThelenHall, 2010; Reference Hall and TaylorHall and Taylor, 1996) and in sustainability (e.g., Reference Betsill, Benney and GerlakBetsill et al., 2020; Reference Patterson, Betsill, Gerlak and BenneyBeunen and Patterson, 2019; Reference Burch, Gupta, Inoue, Kalfagianni, Persson, Gerlak, Ishii, Patterson, Pickering, Scobie, Van der Heijden, Vervoort, Adler, Bloomfield, Djalante, Dryzek, Galaz, Gordon, Harmon, Jinnah, Kim, Olsson, Van Leeuwen, Ramasar, Wapner and ZondervanBurch et al., 2019; Reference Young, King and SchroederYoung et al., 2008). These various traditions suggest a variety of ways in which institutional change might occur (Table 2).

Table 2 Implications about institutional change within core institutionalist approaches

| Attribute | Institutionalism variant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical | Rational choice | Sociological | Discursive | |

| Scale | Macro | Micro | Micro, Meso | Macro-Micro |

| Interactions | Conflictual | Coordinative | Cultural | Communicative |

| Presence of equilibria | No – Institutions are the outcome of historical processes | Yes – Benefit-seeking to optimize within structural contexts of rules | Partial – Cultural norms and values confer stability but are also fluid | Indeterminate – Discourses carry stability but can be challenged |

| Causes of institutional change |

|

|

| Agents act within and outside their institutions to persuade and influence others (Reference SchmidtSchmidt, 2008) |

| Timeframe | Gradual or rapid | Stepwise | Gradual | Sporadic |

Of central importance across these traditions is the ways in which agents are presumed to behave. Historical institutionalism emphasizes contestation and conflict linked to power struggles, rational choice institutionalism emphasizes strategic behavior and coordination linked to calculation around self-interest, sociological institutionalism emphasizes culturally appropriate behavior linked to norms and practices, and discursive institutionalism emphasizes communicative behavior linked to reflexivity and deliberation. When it comes to thinking about attempts to (intentionally) remake institutions, all of these aspects are likely to be relevant. First, intentional change will inevitably be contested and trigger political struggles (historical institutionalism). Second, it will involve coordination around presumed joint interests to address a problem (rational choice institutionalism). Third, it will be driven at least partially by existing or changing norms and concerns over legitimacy (sociological institutionalism). Fourth, it will also be driven by deliberation among agents seeking to step outside of existing institutions and persuade others of the need for change (discursive institutionalism).

But all these behaviors occur within inherited institutional structures that constrain the range of possible action and the types of change that can be accomplished from one moment to the next. Institutions almost never provide a blank slate for action but carry legacies of rules, expectations, arrangements, investments, and norms from prior moments. Even in cases where new institutions are created, this will probably not be in a vacuum but will be linked with existing institutions in some way, whether as a challenge to existing institutions or in some way connected to neighboring institutions. Hence, what matters for institutional remaking is understanding how agents are conditioned by institutional structures, at the same time as they act (for possibly multiple reasons) within these settings, and the overall consequences for (ongoing) institutional development over time.

In recent years, scholars have sought to theorize the mechanisms by which institutional change occurs. Past explanations of institutional change leaned particularly on exogenous factors under the punctuated equilibrium model, whereby periods of stasis are punctuated by moments of shock that trigger abrupt changes (Reference Baumgartner and JonesBaumgartner and Jones, 2009). This is also reflected in the notion of critical junctures in historical institutionalism, where path dependency is redirected at key moments (often due to an exogenous shock). Among climate change scholars, it is sometimes suggested that climate-related disasters may provide “focusing events” (Reference BirklandBirkland, 1998) capable of spurring political responses (e.g., Reference Kates, Travis and WilbanksKates et al., 2012; Reference PrallePralle, 2009). However, there may be no reason to expect that a crisis will automatically trigger reform due to a range of possible barriers to institutional change (Section 2.2).Footnote 15

Contemporary political science shows skepticism toward exogenous factors as a sole explanation for institutional change. For example, Reference LiebermanLieberman (2002, p. 697) argues that a “reliance on exogenous factors” limits a fuller understanding of institutional change. Instead, endogenous explanations of institutional change have been proposed, whereby institutions are seen to have the potential to change gradually as a result of ongoing political struggles over their meaning, interpretation, and enforcement, which introduces deviations that accumulate over time (Reference Mahoney and ThelenMahoney and Thelen, 2010; Reference Streeck and ThelenStreeck and Thelen, 2005). These scholars propose mechanisms of displacement (the introduction of new rules, which directly replace previous rules), layering (the introduction of new rules on top of or attached to existing rules), conversion (new interpretations or enactments of existing rules), and drift (the altered impact of rules within changing circumstances) (Reference Mahoney and ThelenMahoney and Thelen, 2010). The key insight here is to recognize that while the degrees of freedom available to agents are constrained in many ways, there are often also many ambiguities and openings present, which generate ongoing struggles and afford opportunities for flexibility (Reference Mahoney and ThelenMahoney and Thelen, 2010).

On the other hand, sustainability scholars often place significant emphasis on the relation between institutions and their exogenous context. For example, Reference YoungYoung (2010a, Reference Young2010b) argues that institutional change in international environmental regimes is driven, to a significant extent, by pressure from environmental changes, mediated by the extent to which an institution is capable of managing the imposed stresses. This is suggested to occur through mechanisms such as market adjustment, learning, reauthorization of political authority, and amendment procedures (Reference YoungYoung, 2010b). Broadly, this reflects a focus on the “fit” of institutions in their context. But such fit may not just involve material/environmental contexts, but also cognitive/discursive contexts, which are not necessarily aligned. This is especially relevant for climate change, where anticipatory action is grounded in knowledge and norms about unfolding and expected climatic shifts which have not yet (fully) manifested, at the same time that material climate impacts may also be occurring and stressing institutions in new ways.Footnote 16 In this light, Reference YoungYoung (2013) identifies a need to integrate instrumental and interpretive explanations of institutional action, which also alludes to the relation between institutions and their ideational context (Reference LiebermanLieberman, 2002; Reference Patterson and HuitemaPatterson and Huitema, 2019).

More generally, Reference PiersonPierson (2004) emphasizes the need to pay attention to both short and long timeframes in examining mechanisms of institutional change, particularly due to threshold behavior, whereby slow-moving factors (e.g., socioeconomic or demographic shifts) go unnoticed until eventually producing a rapid change when a certain threshold is exceeded. This resonates with Reference YoungYoung (2010a) in the environmental domain, considering the buildup of “stress” within institutions over time. As a result of slow-moving factors, “what may seem like a relatively rapid process of reform is in fact only the final stage of a process that has in fact been underway for an extended period” (Reference PiersonPierson, 2004, p. 141). This is relevant for climate change because slow-moving environmental shifts could cause institutional failures (Section 2.1). More subtly, various slow-moving socioeconomic and political factors could condition a society in ways that make institutional failure more or less likely under an abrupt climate impact. For example, growing social inequality, inadequate knowledge and preparedness, or erosion of political trust could raise the likelihood of catastrophic institutional failure under a major event such as a flood, drought, or storm.

Altogether, this suggests that understanding the (intentional) remaking of institutions requires considering both endogenous and exogenous factors and paying attention to unfolding processes of change over time. Attempts to remake institutions are likely to be inherently political and, therefore, unable to be accomplished without work and struggle. For example, while some agents may seek to change institutions, others may react against changes by seeking to block or manipulate them (Reference CapocciaCapoccia, 2016), or to maintain existing institutions (Reference Lawrence, Suddaby and LecaLawrence et al., 2009), or simply carry on with existing routines (Reference Patterson, Betsill, Gerlak and BenneyBeunen and Patterson, 2019). Thus, institutional remaking will involve active “work” on the part of agents attempting to realize institutional changes. Mechanisms of institutional change are not likely to be straightforward or singular, especially for prospective (e.g., anticipatory) interventions, and may involve both instrumental and interpretive aspects. Moreover, we should expect that attempts to remake institutions will trigger complex political dynamics that play out against the backdrop of existing institutional orders within a particular social and material/environmental context.

3 The Notion of Institutional Remaking

Institutional remaking involves intentional activities undertaken by agents in light of institutional weaknesses or failures. Studying it requires adopting a processual perspective of politics, recognizing partial and unfolding action, and indeterminate and provisional outcomes. Intentionality is central but requires careful elaboration. Institutional remaking is distinct from typical notions of institutional design.

3.1 Defining Institutional Remaking

Institutional remaking is defined here as: the activities by which agents intentionally develop political institutions in anticipation of, or in response to, institutional weaknesses and failures. Hence, it is a political activity that seeks to influence certain type(s) of political institutions, motivated by experience or perceptions of institutional shortcomings. The term “remaking” encompasses both the “making” of new elements and the “remaking” of existing elements, while emphasizing that this (almost always) occurs within an existing (possibly already crowded) institutional setting. Thus, there is always a large degree of working with, and building on, what already exists, rather than the unproblematic introduction of new institutional designs.

Therefore, institutional remaking is distinguished from the notion of institutional design through an emphasis on unfolding processes, embeddedness, and political contestation. Yet it carries the same core interest in understanding how institutions may be intentionally improved. On the other hand, institutional remaking is a subset of the broader notion of institutional change, through its core focus on understanding activities that seek to intentionally bring about institutional change. The notion of institutional change encompasses a wider scope of interest in discovering and explaining processes of change occurring for all sorts of intentional and unintentional reasons. Hence, institutional remaking carves out a distinct focus combining the intentionality concern of institutional design scholars, with the process concern of institutional change (and especially institutional development) scholars. This is further discussed in Section 3.4.

Notably, the definition of institutional remaking proposed does not include a specific end or objective toward which institutional remaking is oriented. In the case of climate change and other pressing governance challenges (Section 1), institutional remaking is oriented toward improving the public good, where public good refers to ends which are, by some reasonable justification, aimed toward benefitting a broad public. This distinguishes institutional remaking from actions that are focused on advancing the private interests of a particular social actor only. Of course, there is no single public good in heterogeneous societies due to the presence of varying and even contradicting interests, preferences, and worldviews. Nonetheless, as an intentional activity, institutional remaking is always done by certain social agents toward certain ends, which should be made explicit when studying it. The public good end is best defined with reference empirically to values and goals articulated by social actors within a given context.

Notably, by not pegging institutional remaking to a particular end, this allows it to be generalized as an analytical approach, which could also be applied to developments deemed negative by some social actors. For example, various political reform agendas favored by one political persuasion but disfavored by another could still readily be studied through a lens of institutional remaking. However, this is beyond the scope here.

3.2 A Processual Lens

The study of institutional remaking requires a processual lens focusing on the interactions by which institutional changes develop (or not). Of course, institutional scholarship contains rich processual insights and leanings, especially in lines of thinking on institutional development (Reference PiersonPierson, 2004, Reference Pierson2000a, Reference Pierson2000b, Reference Pierson1993) and comparative historical analysis (Reference Mahoney and ThelenMahoney and Thelen, 2015).Footnote 17 Elsewhere, much institutional scholarship focuses on static snapshots where initial and final states (e.g., State A, State B) take the foreground, and processes of change are secondary. However, studying institutional remaking requires embracing process as ontology, partly because of the inherently interactional and historically encumbered basis on which institutional changes develop, and partly because when we look forward in time we simply cannot know (or easily assume) what an end state (State B) may be, and therefore explaining change from State A to State B is difficult. We need to find ways to leverage existing insights about processes of institutional change (e.g., drawing on insights from rational, historical, sociological, and discursive lines of thinking; see Section 2.3), in an open-ended way looking forward in time.

Political institutions both cause and constitute struggles over climate change and societal transformation. Institutions are partially autonomous features of political life, which have casual influence on social and political activity but, at the same time, are themselves shaped by social and political activity (Reference March and OlsenMarch and Olsen, 1983). Moreover, institutions involve inherent dynamism (Reference Patterson, Betsill, Gerlak and BenneyBeunen and Patterson, 2019; Reference Lawrence, Suddaby and LecaLawrence et al., 2009; Reference Mahoney and ThelenMahoney and Thelen, 2010), and their production and reproduction is “a dynamic political process” (Reference Streeck and ThelenStreeck and Thelen, 2005, p. 6) emerging from interactions among endogenous actors, and responses to exogenous circumstances.

Institutional remaking, in the fullest sense, is likely to often be an ongoing process, one that is “in-the-making” over extended timeframes and hence needs to be analyzed in ways that recognize this unfolding character. A key departure point is to move from a focus on institutional choice to a focus on institutional development: “To shift our focus from explaining moments of institutional choice to understanding processes of institutional development” (Reference PiersonPierson, 2004, p. 133, emphasis added). This is also important when treating institutional change as a dependent variable, where “established institutions modify the prospects for further institutional change” (Reference PiersonPierson, 2004, pp. 131–132).

However, sustainability scholars often treat institutions in a static way, as either inputs or outputs. As inputs, institutions are frequently invoked to explain performance failures in governance (e.g., success or failure of certain actions) or to explain difficulties in advancing climate change responses more generally (e.g., Reference Biagini, Bierbaum, Stults, Dobardzic and McNeeleyBiagini et al., 2014; Reference Carter, Cavan, Connelly, Guy, Handley and KazmierczakCarter et al., 2015; Reference Eakin and LemosEakin and Lemos, 2010; Reference Gupta, Termeer, Klostermann, Meijerink, van den Brink, Jong, Nooteboom and BergsmaGupta et al., 2010). This approach treats institutions as an independent variable to explain other social, political, and environmental outcomes. As outputs, institutions are examined either in their actuality such as the institutionalization of new norms or practices (e.g., Reference Anguelovski and CarminAnguelovski and Carmin, 2011; Reference AylettAylett, 2015; Reference Carmin, Anguelovski and RobertsCarmin et al., 2012) or in their ideal such as normative prescriptions concerning what “should” be implemented or changed in order to advance climate action. This is an approach that treats institutions as a dependent variable resulting from other causal forces. However, what is still missing is explicit theorization of the processes of change themselves. In other words, institutional change itself needs to be a dependent variable (following Reference Mahoney and ThelenMahoney and Thelen, 2010). This is crucial to understanding how existing institutions are, or could be, remade.

3.3 The Role of Intentionality

Until now, institutional remaking has been defined as an intentional activity. However, this warrants careful elaboration to situate the analytical role of intentionality. Potential pitfalls must be addressed regarding (i) the degree to which intentionality is possible given institutional complexity and (ii) whether or not functionalist arguments are invoked by the notion of institutional remaking.

First, intentionality captures the idea of actors attempting to address perceived institutional weaknesses or failures. On the one hand, it is clear that intentional institutional intervention is urgently required for problems such as climate change. Yet on the other hand, institutional intervention is notoriously challenging and plagued by unintended consequences (Reference GoodinGoodin, 1998; Reference PiersonPierson, 2004, Reference Pierson2000b; Reference Young, King and SchroederYoung et al., 2008). Institutions are typically encumbered by their past. For example, as Pierson (Reference PiersonPierson, 2000b, p. 493) observes: “Actors do not inherit a blank slate that they can remake at will when their preferences shift or unintended consequences become visible. Instead, actors find that the dead weight of previous institutional choices seriously limits their room to maneuver.” Furthermore, societal heterogeneity means that consensus toward any particular course of action is unlikely. Thus, institutional remaking, concerned as it is with prospective changes, recognizes the need for intentionality but also its problems. How can this be reconciled?

The answer here is to relax the expectation that intentional intervention actually leads to the foreseen ends. The outcomes of institutional remaking will always depend on many factors within and outside the scope of control of any particular actor or coalition. However, the substantive problems at hand, and the desired directionality of improvement, nevertheless orient actions taken by actors. Moreover, it should not be expected that the goals of actors/coalitions remain fixed. Negotiation and compromise, pragmatic judgments under bounded rationality, and difficulties realizing collective goals in practice may all modify the goals of actors attempting to remake institutions as these activities unfold over time.

Second, a more subtle, but potentially theoretically fraught (Reference PiersonPierson, 2000b) question arises about whether institutional remaking invokes functionalist arguments. Functionalism refers to a form of argumentation that “explains the origins of an institution largely in terms of the effects that follow from its existence. [however] … [b]ecause unintended consequences are ubiquitous in the social world, one cannot safely deduce origins from consequence” (Reference Hall and TaylorHall and Taylor, 1996, p. 952). Functionalism would assume that pressures on institutions are acknowledged and addressed to enable a system to return to serving a predefined purpose. However, as has been previously noted, mechanisms such as learning, competition, and adaptation (which would be expected to kick in automatically under functionalism) are often likely to be weak (Section 2.2).

Reference PiersonPierson (2004) critiques both an “actor-centered functionalism” (which assumes that actors choose an institutional design in order to meet certain objectives) and a “societal functionalism” (which assumes institutional evolution through competitive selection driven by environmental pressures). While not denying their potential ubiquity, he argues that “they suggest a world of political institutions that is far more prone to efficiency and continuous refinement, far less encumbered by the preoccupations and mistakes of the past, than the world we actually inhabit” (Reference PiersonPierson, 2004, p. 131). Yet concerns about institutional weaknesses and failures may nonetheless motivate certain actors to attempt interventions, even while they are unable to escape the difficult realties of institutional politics (Section 2.2). The key point is that these motivations may not be singular or analytically sufficient for explanation. Doing away entirely with such reasoning obscures the potential to study intentional institutional changes at all (which indeed, some scholars may argue for). Yet this is exactly the challenge with which contemporary sustainability and political science scholarship must do better to engage with (Section 1.6). Moreover, there is no reason to assume that outcomes match objectives; the degree of “success” (however defined) can be assessed empirically.

Working with sustainability problems, such as climate change, raises murky questions about normative goals (and therefore assumed system purposes) and the relationship of institutions to their environmental contexts. For example, addressing climate change is, by definition, concerned with impacts and shifts in natural systems and their effects on human systems. This might make traditional institutional theorists wary of overreliance on functionalist argumentation. Sustainability scholars have approached this challenge through employing concepts such as the “fit” between human and natural systems (Reference Young, King and SchroederYoung et al., 2008). For example, Reference YoungYoung (2013, p. 91) contends that “the success of environmental and resource regimes is a function of the fit or match between the principal elements of these institutional arrangements and the major features of the biophysical and socioeconomic settings in which they operate.” This helps to avoid functionalist oversimplifications by locating the degree of alignment between an institution and its context as an empirical question. It also connotes a problem-grounded focus, where a given sustainability governance problem must be recognized as embedded in both material/environmental and normative (e.g., public good) contexts.

This can be further sharpened by considering the type of question being asked. When asking an ex post explanatory question, what matters is what did happen and how and why (hence excessive functionalism is a risk to constructing a valid or convincing explanation). However, when asking an exploratory question grounded in the present and with a view toward the future (which is a key focus when studying institutional remaking), then what matters is what is happening, and what could happen, and how and why (without presuming what outcomes might actually be produced). Arguably, if scholars are to put theory to work in helping to address pressing institutional problems, rather than wait for changes to play out in the world before venturing an explanation, then there is no choice but to engage with this murky middle ground.Footnote 18

3.4 Design versus Remaking

Intentional intervention is often treated as institutional design and assumed to be rationally carried out toward instrumental ends. But there is no reason conceptually why institutional intervention cannot also be seen as an interpretive activity, conducted by actors toward their own (instrumental and interpretive) ends, within a particular context. This view of institutional intervention – as a contingent political activity with provisional and unfolding effects – remains undertheorized. This is the focus of institutional remaking.