1 Political and Fiscal Development in the American South

1.1 Introduction

The story of the American South as an unequal, politically repressive, violent, exploitative, and backward society has been widely told.Footnote 1 Yet the fiscal history of this region over the long run has never been thoroughly examined. This Element fills this void. We study the evolution of political institutions and public finances across Southern states from 1820 to the eve of the adoption of the federal income tax in 1913 and the onset of World War I. The beginning of this period saw the rising use of enslaved labor to grow the cash crops demanded by rapidly industrializing Western economies, which led to the enrichment of a relatively small planter elite. The second half of this period witnessed the destruction of chattel slavery with the Confederacy’s defeat in the American Civil War, the federal government’s attempt to “reconstruct” the political systems of these states with the extension of suffrage to the newly emancipated, and the ultimate removal of these rights through the use of extensive violence. The period ends with the creation of the “One-Party South,” which resulted in the continued political domination by a small elite well into the mid-twentieth century. As we will show, these momentous political and economic developments altered the power and preferences of the South’s rural elites, setting in motion major changes in fiscal systems across and within states.

In seeking to explain and document the within- and cross-state fiscal patterns over this ninety-year period, we focus primarily on property taxes. Not only did property taxes comprise the vast majority of tax revenues in each of the fourteen states over this period, but they were borne most heavily by the same landed elites who dominated Southern politics. We have a secondary focus on alternative forms of tax revenue and on key investment-related expenditures, notably education and railroads. Taken together, these variables capture the most important elements of state-level finances in the American South during this period.

This Element has several key distinguishing features. First, we adopt a theoretically driven approach, building on a growing literature in political economy that seeks to explain variation across the world in taxation and state capacity (Reference Meltzer and RichardMeltzer and Richard 1981; Reference BoixBoix 2003; Reference Sokoloff and ZoltSokoloff and Zolt 2006; Reference Scheve and StasavageScheve and Stasavage 2010; Reference Besley and PerssonBesley and Persson 2011; Reference Ansell and SamuelsAnsell and Samuels 2014; Reference Scheve and StasavageScheve and Stasavage 2016; Reference DinceccoDincecco 2017; Reference Beramendi, Dincecco and RogersBeramendi, Dincecco, and Rogers 2019; Reference Suryanarayan and WhiteSuryanarayan and White 2021). While providing a parsimonious account of state-level finances is challenging due to the substantial heterogeneity across and within states throughout this period, we contend that a fiscal-exchange lens, focusing on the preferences and power of the landed elite, can help illuminate the historical record. The fiscal-exchange tradition posits that the most efficient, sustainable means of raising revenue is for states to trade services and goods for taxes, as long as three assumptions hold. First, collecting taxes purely through force is costly. Second, citizens are willing to accept taxes commensurate with coveted services – that is, they engage in what Reference LeviLevi (1988) called quasi-voluntary compliance. Third, commitment mechanisms – e.g., political representation via assemblies or political parties – ensure taxpayers that their money will be spent appropriately. The fiscal-exchange tradition thus links quasi-voluntary tax compliance to spending through formal representation, and argues that deviations from such an arrangement are likely to generate significant resistance and attempts to change the institutions that govern representation and fiscal policy.

We extend this framework to outline the conditions under which rural elites in an agricultural setting characterized by high levels of inequality and labor coercion would support or reject progressive taxation, and explain why they could not impose onerous taxes on other groups in society, notably low-income Whites. Given the agrarian structure of the Southern state economies and the concentration of assets and income in the hands of the plantation class, rural elites constituted the most obvious potential source of government revenue during the nineteenth century. As such, their willingness to comply with tax demands would determine in substantial part the amount of taxes raised, the costs of enforcement, and the sustainability of the fiscal pathway. Specifically, we argue that rural elites will support taxation on themselves and build fiscal capacity under three conditions. The first key driver is exclusive political control. If rural elites control politics in the present period and this control is likely to persist into the future, their willingness to increase taxation on themselves rises. Political control in the present period is necessary, as this determines how state fiscal resources are spent. Future control is also critical, as tax capacity, once established, can have a long half-life (Reference D’arcy and NistotskayaD’arcy and Nistotskaya 2018). Without the expectation of future control, elites fear increasing the state’s ability to extract, as power over taxation and spending could shift toward social groups with different preferences (e.g., urban residents or lower-income voters). Yet these two conditions are not sufficient on their own. We argue that in addition to political control, both in the present and into the future, rural elites must have demand for collective goods that will benefit their economic interests and are difficult to provision privately. By contrast, agricultural elites will seek to stymie progressive taxation under most other circumstances—i.e., when they are out of power or their dominance is contested, when there is uncertainty over future political control, or when demand for collective goods is weak or fragmented.

Explaining when and why rural elites accept self-taxation (and refrain from coercive taxation of others) adds fresh insights to the rich literature about the rise and fall of progressive taxes and the role of various elites in driving changes in fiscal systems. The existing literature has shown that rural elites may actively undermine the capacity for progressive taxation when power is uncertain or contested (Reference Suryanarayan and WhiteSuryanarayan and White 2021); that rural elites may support progressive taxation when they can pass the burden onto emerging competitors, notably the manufacturing sector (Reference Mares and QueraltMares and Queralt 2015; Reference Mares and Queralt2020); and that urban elites may accept progressive taxes on themselves when they desire spending on human capital that will facilitate industrialization (Reference Beramendi, Dincecco and RogersBeramendi et al. 2019; Reference HollenbachHollenbach 2021). The prevailing view, however, is that rural elites generally oppose fiscal extraction, especially when the burden could fall on them, and that polities controlled by rural elites eschew investments in fiscal capacity and adopt regressive tax systems (e.g., Reference Lizzeri and PersicoLizzeri and Persico 2004; Reference Galor and MoavGalor and Moav 2006; Reference Galor, Moav and VollrathGalor, Moav, and Vollrath 2009; Reference Baten and HippeBaten and Hippe 2018; Reference Beramendi, Dincecco and RogersBeramendi et al. 2019; Reference HollenbachHollenbach 2021).Footnote 2

Our analysis thus offers a nuanced challenge to existing accounts using an unlikely case, and also contributes several ideas to the fiscal-exchange literature – notably that quasi-voluntary compliance by rural elites rests on exclusive political control in the present and into the future. Specifically, we argue that merely having political representation in the present period, the standard minimal threshold for fiscal bargains, is insufficient, suggesting that high rural elite taxation is incompatible with shared state control. Second, instead of an exchange between rulers and economic elites over taxation and representation, we consider the consequences for taxation when the rulers and the primary target for taxation – due to their control of society’s resources/assets – are the same. Although coercive taxation of non-elite groups by elites remains an option in these settings, collecting taxes from low-income groups in agrarian economies tends to be costly and conflictual and to produce a low “tax take” (Reference Moore, Deborah Braütigam, Fjeldstad and MooreMoore 2008). Thus, rural elites interested in the provision of capital-intensive public goods have incentives to refrain from imposing excessive tax burdens on other social groups if doing so has the potential to stimulate rebellion, exit, or demands for representation that could upend their exclusive control – especially if the tax yield would be low.

Critically, the South’s rural elites were neither benevolent, nor did their actions trigger widely shared long-run development. They increased taxation on themselves to fund public spending that would benefit them disproportionately, rather than to provide public goods that would improve broader welfare or generate long-term development. The coexistence in the American South of greater investments in state capacity in the absence of broad-based development is consistent with claims found elsewhere (e.g., Reference QueraltQueralt 2017).

The second key distinguishing feature of this Element is the abundance of original, archival data upon which it rests. We collected a nearly complete data set of annual state tax revenues, including specifically the amount of property taxes, for each state between 1820 and 1910. We complement these data with several additional measures, including the amount of regressive poll taxes levied for each state and ad valorem property tax rates over the same period. For a subset of states, we are also able to test whether rural elites “passed on” taxation by decomposing the share of property taxes levied on each sector (e.g., rural vs. urban). We also have the amount of substate (county, municipal, etc.) property taxes levied once every ten years between 1860 and 1910. This allows us to test whether there was substitution between state and substate taxes that could weaken our argument. Finally, we have data for key expenditure items, notably education and railroads. The comprehensive nature of our data not only allows us to test our argument vis-à-vis other arguments, but presents for the first time a relatively complete picture of Southern fiscal history at the state level over this period.Footnote 3

Using these data and three distinct temporal shocks to the political institutions of Southern states, we find substantial support for our argument. In the prewar period between roughly 1820 and the early 1840s, we observe relatively low progressive taxation across all of these states. Yet the onset of a boom in international demand for Southern cash crops such as cotton, which increased the demand for land to be cultivated, combined with technological improvements in railroads that could unlock millions of acres of land that was far from navigable water, substantially increased the demand from Southern slaveholders for the construction of railroads – collective goods. We show that the shock had differential effects depending on the extent of planter control: only in states in which contemporary and future slaveholder political control was higher – due to legislative malapportionment that persistently overrepresented highly enslaved counties – did property taxes, which fell overwhelmingly on slaveholders, rise substantially. We show that these states also allocated significantly more state financing toward railroads and as a result constructed substantially more miles of railroad track. Importantly, rural elites in malapportioned states did not impose higher taxes on poorer Whites to finance state expansion.

The second period, Reconstruction (1867–77), was marked by emancipation from slavery, the extension of the franchise to all adult male former slaves, and its enforcement by Congress in the aftermath of the Civil War: the victorious federal government used the US Army to register Black voters and uphold their newly granted political rights. The presence of the Army, particularly in plantation areas, allowed for the imposition of higher property taxes, triggering a significant backlash against the fiscal policies and political institutions that facilitated such extraction (Reference FonerFoner 2014; Reference LoganLogan 2020; Reference Suryanarayan and WhiteSuryanarayan and White 2021). However, the short-run fiscal effects of the federal intervention were substantial, especially in places where rural elites’ formal political representation was disproportionately small. Progressive taxes rose the most in places where rural elites had the least political recourse for resisting taxation due to federal protection of Black voters and officeholders – that is, where the US military limited Southern elites’ ability to use their disproportionate de facto power to prevent the expanded electorate from levying and collecting large amounts of progressive taxation. Property taxes rose the least in the four Southern states that were not occupied by federal troops.

The Reconstruction Southern tax boom lasted only as long as the federal intervention, which eroded across these states until finally ending with the Compromise of 1877. Once the federal government stopped subsidizing the costs of enforcing these policy changes, taxes across all of the previously occupied states converged to a lower level. In the absence of a powerful external enforcer, and facing intense political contestation, rural elites began to effectively curtail progressive taxation.

The third and final burst of property taxes occurred at the beginning of the “Jim Crow” period (circa 1890), during which eleven of the fourteen states adopted suffrage restrictions that disenfranchised their Black populations and some low-income Whites. With the decline in political contestation and rural elites once more gaining a firm control over state politics, the prospects of present and future cross-class and cross-race redistribution declined, and elite taxes increased – as did spending on selective public goods, such as universities. In the states without voting restrictions, by contrast, property taxes and higher education spending lagged. Once again, rural elites in more protected political positions did not impose higher taxes on poorer Whites to finance state expansion.

In short, we contend, Southern fiscal development during this period largely reflects the power and preferences of the plantation class, whose members embraced progressive taxation when and where they wanted collective goods and had a secure grip on power but behaved contrastingly toward property taxes in circumstances where their dominance was contested.

This Element makes several contributions to at least two literatures. First, it contributes to the political economy of taxation literature by identifying precise and simple conditions that facilitate taxation of the rural rich, by the rural rich, and for the rural rich. Our framework not only establishes a higher minimal threshold for a bargain to emerge between rural elites and rulers than one commonly finds in the fiscal-exchange literature; it also suggests that some bargains may preclude others, making control of the state zero-sum. Second, it makes an important contribution to the historical American political economy literature. For one, our framework provides important analytical insights that distinguish our work from other explanations of Southern taxation, even those focusing on smaller, specific periods of time (Reference SeligmanSeligman 1969; Reference WallisWallis 2000; Reference EinhornEinhorn 2006). More broadly – and while much is known about individual Southern states, time periods, and particular dimensions of fiscal development – to our knowledge no work has tried to explain Southern fiscal developments across these fourteen states for this length of time, nor has any study drawn upon a nearly as complete annual data set of state taxation, or tried to put together both the revenue and spending sides of government accounts for each Southern state over these three different eras. Furthermore, the fact that our long-run analysis leverages exogenous shocks and considerable variation in both the input and output variables should lend confidence to the inferences.

This Element proceeds as follows. We begin with a brief historical overview of this period. In Section 2, we outline a theoretical framework for understanding Southern taxation and situate this within the existing literature on the political economy of taxation. In Section 3, we describe our data collection efforts and resulting data set in detail. In Section 4, we examine the prewar period (1820–60). We follow this in Section 5 by examining the postwar period (1868–1910).

1.2 Historical Context

The fourteen states that comprise our study are not called Southern states due simply to their geographic position relative to other states that made up the United States. Rather, their primary defining feature between the seventeenth and mid-twentieth centuries was the reliance on and exploitation of enslaved and later politically repressed agricultural laborers who descended from Africans brought against their will to the British North American colonies by a relatively small White rural elite.Footnote 4 While slavery was legal in each of the thirteen British colonies on the eve of the American Revolution (1775–83), only in the Southern coastal colonies from Maryland to Georgia was a quarter to half of the population enslaved (1790 Census).Footnote 5 As the US territory expanded westward and new states were admitted to the Union, slavery thrived in the Southern states, especially with the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 and the massive increase in international demand for cotton from industrializing Europe. At the same time, each Northern state successively abolished or severely restricted slavery.Footnote 6 By 1850, 99 percent of the approximately 3.2 million enslaved people lived in the fourteen states we study. Table 1 reports key variables of interest for each state and period of our study between 1820 and 1910. Column 1 reports the share of the total population who were enslaved in 1820, the first year of our study, and column 2 shows the same in 1860, the year before the American Civil War began.

Table 1 The fourteen Southern states, 1820–1910

| Enslaved pop. share 1820 (%) (1) | Enslaved pop. share 1860 (%) (2) | Black share 1868 (%) (3) | Black share pop. reg. voters 1900 (%) (4) | Prewarmalappor-tioned state (5) | Recon-struction state (6) | Type of suffrage restriction (7) | Year enacted (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 33 | 45 | 63 | 45 | 0 | 1 | LT, PT | 1901 |

| Arkansas | 26 | 35 | 28 | 0 | 1 | PT | 1892 | |

| Florida | 44 | 58 | 44 | 1 | 1 | PT | 1889 | |

| Georgia | 44 | 44 | 50 | 47 | 1 | 1 | LT, PT | 1906* |

| Kentucky | 23 | 19 | 13 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| Louisiana | 45 | 47 | 65 | 47 | 1 | 1 | LT, PT | 1898 |

| Maryland | 26 | 13 | 20 | 1 | 0 | None | ||

| Mississippi | 44 | 55 | 56 | 59 | 0 | 1 | LT, PT | 1890 |

| Missouri | 15 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| N. Carolina | 32 | 33 | 41 | 33 | 1 | 1 | LT, PT | 1900 |

| S. Carolina | 51 | 57 | 63 | 58.4 | 1 | 1 | LT, PT | 1895 |

| Tennessee | 19 | 25 | 40 | 24 | 0 | 0 | PT | 1889 |

| Texas | 30 | 46 | 22 | 0 | 1 | PT | 1902 | |

| Virginia | 40 | 31 | 47 | 36 | 1 | 1 | LT, PT | 1901 |

Note: Arkansas (1836), Florida (1845), and Texas (1845) were admitted as states after 1820. LT = Literacy Test. PT = Poll Tax. *Georgia enacted the literacy test in 1906 and the poll tax in 1877.

Whereas slavery was the main defining feature of the Southern economy and society, two other crucial features need highlighting.Footnote 7 First, the South, especially the more heavily enslaved states that later formed the Confederacy, was overwhelmingly rural and agrarian. Figure 1 provides a comparative perspective, showing the urbanization rate every ten years between 1820 and 1910 for the US South, the first fifteen Northern US states, England and Wales, and the German Empire over the same period.Footnote 8 The Southern urbanization rate in 1910 is roughly half the value of England’s in 1820, and just barely above the US North’s figure for 1850. Figure 2 shows the agricultural share of output (comprising agricultural and manufacturing activities). The share of manufacturing output in the average Northern state in 1850 exceeds the same share in the average Southern state in 1910.

Figure 1 Urbanization rate across regions, 1820–1910

Figure 2 Agriculture share of output (agriculture and manufacturing), 1840–1910

Second, Southern states were characterized by extreme levels of economic inequality, as the ownership of the enslaved was heavily concentrated in a small minority. The average enslaver in 1860, for example, had approximately fourteen times the wealth of the average non-slaveholder (Reference WrightWright 1978, p. 36), and the Southern wealth Gini coefficient was estimated to be 0.71 (Reference RansomRansom 2001, pp. 63–64).Footnote 9 Furthermore, due to the low levels of economic integration between the high-enslaved (“lowland”) and low-enslaved (“highland/upland”) areas across the South (Reference WrightWright 1978, p. 39), the economic spillovers of Southern slavery were fairly low to most of the majority nonslaveowner White population.

Not only was economic inequality between enslaver and non-enslaver Whites high, poor Whites also experienced substantial political inequality as a result of slavery. While enslavers were unlikely to have ever comprised a majority of the adult White male population in any Southern colony or state, the historical record leaves little doubt that slaveholders dominated colonial and later state politics (Reference GreenGreen 1966; Reference WoosterWooster 1969, 1975; Reference JohnsonJohnson 1999; Reference McCurryMcCurry 2012; Reference ThorntonThornton 2014; Reference MerrittMerritt 2017; Reference Chacón and JensenChacón and Jensen 2020c). Their dominance stemmed from substantial advantages in not only de facto but de jure powerFootnote 10 – for example, during colonial times they used their dominance to structure political institutions, including the malapportionment of state legislatures to systematically overrepresent districts with greater enslaved density (Reference GreenGreen 1966; Reference Chacón and JensenChacón and Jensen 2020a).

Enslaver dominance of Southern state governments was critical because states played the primary role in the promotion of economic development and the provision of public goods in the prewar period (Reference WallisWallis 2000; Reference Wallis and WeingastWallis and Weingast 2018). Thus the promotion of economic development, including publicly supported systems of education and infrastructure, as well as the choice on the system of taxation to finance these public expenditures, was substantially influenced by a small rural elite.

The 1860 election of the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln, to the presidency led to the rapid secession of eleven Southern states and the formation of the Confederate States of America in February 1861.Footnote 11 The Confederacy’s defeat in the American Civil War (1861–5) and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, abolishing slavery, resulted in the permanent emancipation of nearly 4 million enslaved Southerners (out of a total population of roughly 12 million).

Congressional Republicans sought to use the South’s defeat as an opportunity to transform each state’s political system with the goal of diminishing the power of the small planter elite (Reference FonerFoner 2014).Footnote 12 With the passage of several Military Reconstruction Acts in 1867 and 1868, “radical Reconstruction” would entail the use of the military to register all adult Black males to vote and then protect their access to the ballot box in the ten Reconstruction states.Footnote 13 Furthermore, the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments would, in principle, offer the recently enfranchised equal protection under the law, guaranteed citizenship, and the prohibition of racial disenfranchisement.

For a brief period, Southern politics was completely upended. Table 1, column 3 shows the share of each state’s registered voters who were Black in 1867–8.Footnote 14 This led to the election for the first time in American history of thousands of Blacks to local, state, and federal office across the ten Reconstruction states (Reference FonerFoner 1993). There was a fundamental expansion in the role of the Southern state, especially with respect to public education. This fiscal expansion was financed primarily by raising property taxes that fell most heavily on the small, landed elite.Footnote 15

The rising tax burden quickly emerged as a focal point for Reconstruction’s opponents. In several states, Democratic leaders organized taxpayers’ conventions, whose supporters demanded a reduction in spending and called for a return to rule by men of property – which entailed denying Blacks, as well as some Whites, any role in Southern public affairs (Reference FonerFoner 2014). From the outset, this largely elite-driven backlash against Radical Republican rule used highly organized terrorist groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan, to restore Democratic Party rule and limit Black political power. Despite the promise to use the federal military to enforce these newly granted civil and political rights, the occupation was never extensive enough to protect a largely rural Black population, thinly distributed across the vast South.Footnote 16 Furthermore, with western expansion making greater demands on federal resources, the size of the occupation decreased throughout the period of Congressional Reconstruction (1867–77). The extensive use of violence eventually resulted in the return to power of the Democratic Party, termed “Redemption” by the conservative elites who had been restored to office.Footnote 17 Federal military enforcement of Black political rights ended with the so-called Compromise of 1877.Footnote 18

While the end of Reconstruction saw Black political power fall substantially, the political control of the planter class was by no means uncontested. For one, Blacks formally retained the right to vote and therefore remained a threat to the political dominance of Southern Democratic elites (Reference KousserKousser 1974; Reference PermanPerman 2003; Reference ValellyValelly 2009). In terms of future power, the possibility remained that the federal government would intervene on behalf of Black voters. Moreover, elections continued to be highly contested affairs: the period between 1880 and 1900 saw opposition parties routinely win more than a third of the state legislative seats, and non-Democratic Party candidates often won more than 40 percent of the popular vote for governor (Reference DubinDubin Reference Dubin2007, Reference Dubin2010).

These working-class electoral threats to Democratic Party rule largely ceased between 1889 and 1907 with the adoption of suffrage restrictions, such as poll taxes and literacy tests, in eleven Southern states, which had the consequence of formally disenfranchising most Black voters. At the same time, the threat of federal intervention on behalf of Black rights receded substantially after 1890. The defeat of the Lodge Federal Elections Bill of 1890, which would have provided for the federal regulation of congressional elections, ended Congress’ efforts to protect Southern Black voters until the 1960s. That states would be largely left to their own devices was largely confirmed in May 1896 and April 1898, when the Supreme Court handed down two decisions that ratified developments in the South. Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) confirmed the federal government’s inability to protect individual rights within the states, and Williams v. Mississippi (1898) removed any remaining uncertainty that the methods of disfranchisement employed in the South would be declared unconstitutional (Reference PermanPerman 2003). These factors contributed to the creation of the “One-Party South,” which would reign through much of the twentieth century.

Table 1 shows some key demographic and political features of this final period of our study – the onset of “Jim Crow” (1889–1910). Column 4 reports the share of each state’s population who were Black in 1900,Footnote 19 and columns 7 and 8 show the date and type of suffrage restrictions adopted.

2 Theoretical Framework

2.1 The Existing Literature

We know that some polities are better at raising revenue than others and that the incidence of taxation varies significantly across space and time. The existing scholarship on this topic is sufficiently broad and multifaceted that our coverage of the literature will necessarily be limited. Generally speaking, extant theories emphasize the role of four broad factors to explain tax patterns, particularly the emergence of progressive taxation: temporary contextual factors, especially war (e.g., Reference Tilly and Charles TillyTilly 1975; Reference Scheve and StasavageScheve and Stasavage 2010), structural conditions that determine actor incentives as well as the technical feasibility of particular fiscal arrangements, such as geography or the structure of the economy (Reference Moore, Deborah Braütigam, Fjeldstad and MooreMoore 2008; Reference RossRoss 2015; Reference Mayshar, Moav and NeemanMayshar, Moav, and Neeman 2017), the specific constellation of social and political groups, such as ethnic or class solidarity or the nature of political coalitions (e.g., Reference LiebermanLieberman 2003; Reference Ansell and SamuelsAnsell and Samuels 2014; Reference SaylorSaylor 2014; Reference Mares and QueraltMares and Queralt 2015, 2020; Reference Beramendi, Dincecco and RogersBeramendi et al. 2019; Reference Suryanarayan and WhiteSuryanarayan and White 2021), and the institutions that govern the relationship between citizens and the state (e.g., Reference LeviLevi 1988; Reference North and WeingastNorth and Weingast 1989; Reference StasavageStasavage 2007; Reference TimmonsTimmons 2010). Additionally, within each of these categories, there are two basic approaches for explaining variation in the form of taxation: the coercive approach, which underscores the extractive power of governments to impose taxes regardless of the preferences of taxpayers, and the fiscal contract perspective, which emphasizes mutually agreed-upon bargains between state leaders and resource holders.

Coercion-based models of taxation are predicated on the absence of a negotiated exchange between state leaders and social actors: taxpayers lack representation, and there is no guarantee that policy decisions will reflect their preferences. Coercive extraction explicitly allows for a disjuncture between the incidence of taxes and spending – that is, for relatively unfettered redistribution.Footnote 20 Much of the recent work focusing on elite taxation follows a coercion-based logic.Footnote 21 The canonical median-voter model (Reference Meltzer and RichardMeltzer and Richard 1981) and its myriad offshoots (e.g., Reference BoixBoix 2003; Reference Acemoglu, Naidu, Restrepo and RobinsonAcemoglu et al. 2015), for example, contend that elites will be taxed more heavily in democratic societies, particularly when inequality is high. More recent scholarship has instead stressed various forms of intra-elite conflict as a potential trigger for progressive direct taxation, in which one elite group successfully shifts the tax burden onto another elite group in an effort to restrict the latter’s de facto political or economic power (Reference Mares and QueraltMares and Queralt Reference Mares and Queralt2015, Reference Mares and Queralt2020).

By contrast, contractual models of taxation posit the existence of a negotiated exchange based on mutual interests of governments and social actors in which taxes are traded for goods and services. According to these models, people will engage in what Reference LeviLevi (1988) called quasi-voluntary compliance when public spending reflects their preferences. Spending that deviates from taxpayer desires, by contrast, engenders resistance to taxes and the political arrangement that generated them.Footnote 22 Mechanisms of voice and accountability solve commitment problems between rulers and taxpayers, facilitating tax increases and investments in fiscal capacity (Reference Bates and LienBates and Lien 1985; Reference North and WeingastNorth and Weingast 1989).Footnote 23 Because tax collection costs are endogenous to how governments raise revenue and how they spend it, high levels of cross-group redistribution (e.g., from rich to poor and vice versa) is difficult to sustain, barring some type of compensation along the lines identified by Reference LiebermanLieberman (2003) and Reference Scheve and StasavageScheve and Stasavage (2016). These authors show that redistribution can emerge in equilibrium as a side payment for ethnic solidarity (e.g., in Lieberman, a cross-class alliance among Whites to repress Blacks in South Africa), or for the differential costs of war (e.g., in Scheve and Stasavage, the wealthy disproportionately fund warfare while the masses bear the brunt of the fighting). In both cases, taxes on the rich represent a form of compensatory redistribution tied together by shared identities and/or sacrifices.

Even though trading services for revenue is a more efficient and sustainable means of raising revenue than coercive extraction, a fiscal contract between elites and rulers may not always emerge. Negotiated exchanges are more attractive in the presence of specific conditions: namely, when members of (potential) taxpaying groups have similar material interests and policy preferences;Footnote 24 the public sector has a comparative advantage in the production of the desired collective good or service (Reference LeviLevi 1988); and there are commitment mechanisms ensuring taxpayers that their money will be well spent (Reference Bates and LienBates and Lien 1985; Reference LeviLevi 1988; Reference DinceccoDincecco 2011; Reference GarfiasGarfias 2019; Reference Flores-MacíasFlores-Macías 2022). Commitment mechanisms include assemblies (Reference North and WeingastNorth and Weingast 1989; Reference Hoffman and NorbergHoffman and Norberg 1994) that guarantee at least a voice, if not an explicit veto, over fiscal decisions, and political parties (Reference StasavageStasavage 2007; Reference TimmonsTimmons 2010), who act as agents for groups of taxpayers. Beyond the factors affecting the likelihood of emergence of fiscal contracts, there are also contextual elements that can influence the parameters of these bargains, some of which we develop in what follows.

Changes in the economy, notably industrialization, have been associated with increased prospects for progressive taxation. One reoccurring claim is that urban elites benefit more from public expenditures than rural elites (e.g., Reference Lizzeri and PersicoLizzeri and Persico 2004; Reference Beramendi, Dincecco and RogersBeramendi et al. 2019; Reference HollenbachHollenbach 2021): spending on education, sanitation, and infrastructure raises returns to industrial capital and draws labor to cities, potentially harming agrarian interests (e.g., Reference Baten and HippeBaten and Hippe 2018; Reference Galor, Moav and VollrathGalor et al. 2009). Hence, rising urban elites may be willing to shoulder a higher tax burden through progressive direct taxation in order to fund public goods that increase industrial output (Reference Ansell and SamuelsAnsell and Samuels 2014; Reference Beramendi, Dincecco and RogersBeramendi et al. 2019; Reference HollenbachHollenbach 2021). However, the spending pressures caused by industrialization do not always result in the expansion of taxation. Rather, an increase in tax revenue is possible only where new capitalist elites can translate their economic power into political influence (e.g., Reference Emmenegger, Leemann and WalterEmmenegger, Leemann, and Walter 2021).Footnote 25

Likewise, the nature of the tax base may influence the incentives for both rulers and taxpayers to bargain around exchanging representation for resources. Actors with more mobile assets, for example, are more likely to be granted government benefits and a voice in government decisions in exchange for revenue (Reference Bates and LienBates and Lien 1985), while actors with less mobile assets, notably agriculture and mining, may find themselves held hostage: the fixed nature of their assets means they cannot withdraw if the exchange with the state becomes unfavorable (Reference ZolbergZolberg 1980). Historically, in fact, rural elites have been rather successful at blocking unilateral extraction on the part of the state – a capability attributed to both de jure political institutions that overweight their preferences and de facto forms of power that impede meaningful political change (Reference Acemoglu and RobinsonAcemoglu and Robinson 2006; Reference Alston and FerrieAlston and Ferrie 2007; Reference ZiblattZiblatt 2009; Reference Albertus and MenaldoAlbertus and Menaldo 2014).

The emergence of fiscal bargains also depends, in part, on the availability of alternative sources of revenue. Rulers enjoying large nontax incomes from natural resource rents, access to loans, large inflows of aid, or the exploitation of state property – such as railways, post offices, or mines – may be less compelled to exchange representation for resources (as summarized in Reference RossRoss [Reference Ross2015]).

Finally, another relevant strand in the literature explains the rise and fall of progressive taxation as a function of ethnic solidarity in a context of salient class and racial cleavages – conditions that clearly characterized the American South. Reference LiebermanLieberman (2003), for example, argues that the political exclusion of Blacks in apartheid South Africa prompted the emergence of a cross-class coalition among Whites in which progressive taxes and spending went hand in hand. Reference Suryanarayan and WhiteSuryanarayan and White (2021), by contrast, set forth the conditions that generate intra-ethnic solidarity with the aim of undermining taxation and bureaucratic capacity. Specifically, they contend that the expansion of the franchise to African Americans in the United States threatened the prevailing vertical racial order and gave rise to a cross-class coalition among Whites that weakened taxation and state capacity where the legacy of slavery was strongest. In particular, the authors claim that intra-White inequality was a key determinant of tax patterns following the Civil War. Our empirical analysis will engage with Lieberman’s alternative explanation and address the threat to inference posed by the potential omitted variable highlighted by Reference Suryanarayan and WhiteSuryanarayan and White.

Missing in this rich literature, however, is an explanation for (and examples of) rural elites’ support for (self-)taxation in contexts where they already have representation, and indeed may be the uncontested incumbent power holders with no challengers on the horizon, something our analysis provides.

2.2 The Argument

We argue that three conditions are pivotal to determining rural elites’ preferences over public finance and, in particular, their willingness to tax themselves when they are in power. First, rural elites must value some “public good” that the state can produce at a lower cost than they can provide privately.Footnote 26 While obtaining benefits from spending is a necessary condition for self-taxation, as others have highlighted (e.g., Reference TimmonsTimmons 2005; Reference Beramendi, Dincecco and RogersBeramendi et al. 2019; Reference HollenbachHollenbach 2021), we claim it is not sufficient.

Second, unlike other groups, rural elites must have relatively exclusive control over, if not an outright monopoly on, political power, rather than just representation. Their reluctance to accept taxes amidst shared governance stems from several factors. Their assets are highly specific, visible, not particularly mobile, and disproportionately valuable. They thus have fewer exit options and are more exposed to taxation and expropriation. Furthermore, their preferences over spending are often vastly different from that of other groups in society. Specific goods, such as public education, sanitation, or urban infrastructure, could undermine the economic system that undergirds their rent generation. Finally, because they are a numerically small group, many sets of voting rights can prove unfavorable. Given these characteristics, governing coalitions may find it challenging to credibly commit to not expropriating rural elites, especially in the event of an exogenous shift in power.

Third, besides exclusive political control in the present, elites must believe that their power will remain unchallenged: assured future political dominance minimizes the chances that the enhanced extractive tools of the state will be used to expropriate their wealth later. Our logic is similar to that of Reference Besley and PerssonBesley and Persson (2011), in that political stability lengthens rulers’ time horizon. However, where their model predicts that stability leads to investments via taxation on non-ruling groups (“redistributive state”), our argument posits that when political elites are asset owners with strong demands for public goods, stability eliminates the commitment problem, paving the way to increase self-taxation.

In other words, rural elites may be less likely to rely on the state for collective goods and, as economic actors that derive power from the control of valuable economic resources that are especially vulnerable to taxation, they may be more attuned to time-consistency problems. However, if they desire public goods in which the state has a comparative advantage, and they feel secure about their monopoly on power, they have incentives to tax themselves.Footnote 27 These empirical conditions mean that rural elites’ threshold for agreeing to voluntary taxation will be relatively high.

A corollary of our argument is that elites have self-enforcing incentives to refrain from imposing hefty taxes on other social groups, so long as such taxes could generate counter-reactions that might threaten their monopoly on power.Footnote 28 We contend that Southern elites did, in fact, face formidable technical and political barriers to shifting an increased burden onto other groups. First, the urban/manufacturing sector was small, even by the end of the period. At the same time, netting tax revenue from yeoman farmers and peasants is notoriously daunting (Reference Moore, Deborah Braütigam, Fjeldstad and MooreMoore 2008): the lack of formal records of economic transactions, the seasonality and instability of farm production, the generally low levels of cash income, and the paucity of wealth outside of the plantation economy meant, in all likelihood, that a considerable amount of revenue would have been absorbed by the collection costs.

Second, coercive taxation, especially if arbitrary and capricious, should stimulate tax resistance, migration toward less extortionate jurisdictions, demands for representation, and pressure to change the institutions that determine fiscal policies. Thanks to the work of historians (e.g., Reference FonerFoner 2014), and social scientists (e.g., Reference Chacón and JensenChacón and Jensen 2020b; Reference LoganLogan 2020; Reference Suryanarayan and WhiteSuryanarayan and White 2021), we know that redistributive taxes and spending during Reconstruction generated a violent elite-led backlash that undermined the tax system by targeting the electoral and bureaucratic institutions from which it emerged.

Coercive taxation on non-elite groups in the South presented its own complications. First, non-elite Southern Whites were sufficiently mobile and numerous to pose problems if angered. Indeed, the threat of migration was not just hypothetical. According to the 1860 Census, approximately 25 percent of the Whites born in the original Southern states, as well as those born in later-admitted slave states, such as Alabama, Kentucky, and Tennessee, had migrated out of these states. Furthermore, outside of large cities, such as Baltimore, New Orleans, and St. Louis, Southern states received few European immigrants during the various waves of immigration. Out-migration of both Blacks and Whites accelerated after the Civil War, with White migration especially intense in the first two decades following the conflict. Second, anti-elite political movements were a recurring phenomenon (Reference KousserKousser 1974; Reference HymanHyman 1989; Reference HahnHahn 2006; Reference Gailmard and JenkinsGailmard and Jenkins 2018), which culminated in the 1880s and 1890s when populists threatened Democratic Party rule in many Southern states (e.g., Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia). Excessive taxes on lower-income Whites or urban areas could have enhanced prospects of a class-based Black-White alliance after the Civil War, which would have eroded uncontested planter political control. In fact, these are not mere conjectures: working-class Black-White coalitions did win control of state governments in Virginia (early 1880s) and North Carolina (mid-1890s) and fell just short in several other states (Reference PermanPerman 2003). In sum, in certain places and time periods, Southern rural elites had the capacity and motivation to embrace self-taxation; in other places and time periods, they had the incentive and power to fight redistributive taxes.

3 Data and Empirical Strategy

We created an original annual data set of state-level taxation between 1820 and 1910 across fourteen Southern states to assess our hypothesis about the relationship between rural elite power and fiscal outcomes.Footnote 29 We located auditor, comptroller, and US Treasury reports for as many years as possible from each state. We intentionally excluded the Civil War and pre-Congressional Reconstruction years from 1861 to 1867.Footnote 30 With these years omitted and accounting for the three states that entered after 1820, our sample comprises 1,146 possible state-years. From these reports, we extracted the total tax revenues collected into the state treasury, as well as tax revenues by type. These include property taxes, poll taxes, occupation and licensing fees, business taxes (e.g., on banks and insurance companies), and miscellaneous taxes, such as those on the sale of liquor and fertilizer.

3.1 Property Taxes between 1820 and 1910

Our primary variable of interest is the annual amount of property taxes levied and collected. We focus on this particular tax for two reasons. First, property taxes accounted for the majority of tax revenues for most state-years in our data set, especially after 1840. In a sample of approximately 800 state-years in which we have both property taxes and total tax revenues, property taxes accounted for roughly 74 percent of total state tax revenues.Footnote 31 Second, unlike regressive taxation such as liquor taxes, poll (capitation) taxes, and occupational licenses, these taxes fell most heavily on the same small, rural, planter elite that dominated Southern politics (Reference WrightWright 1978; Reference Thornton, J. Morgan Kousser and JamesThornton 1982; Reference Ransom and SutchRansom and Sutch 2001). We provide additional support for this claim, as well as a short overview of property tax liabilities, assessment, and collection.

Property tax systems evolved considerably during the period under study. The systems that emerged during the colonial and early postindependence periods were rudimentary (Reference EinhornEinhorn 2006; Reference RabushkaRabushka 2010). While property taxes were a sizeable portion of tax revenues, they rarely entailed an attempt to assess systematically each individual household’s value of real estate and personal property. Instead, certain taxable property (e.g., farm animals and equipment, slaves, etc.) was assessed on a fixed per-item basis, meaning that items with very different economic values could face similar liabilities. Land was typically assigned to a few categories based primarily on its geographic location (i.e., soil, access to navigable water, etc.) and then charged a differential per-acre rate.

Following developments that began in Missouri in the 1820s, Southern states began adopting property tax systems in which the same ad valorem rate (uniformity) was applied to all private property (universality). This entailed the creation of a much more sophisticated tax collection infrastructure that could assess the value of all taxable property. As Reference EinhornEinhorn (2006): p. 242 details, the transition to uniform property tax systems was politically contested, as rural elites (successfully) fought “to limit the taxes that majorities could impose on them.”Footnote 32 By 1860, all fourteen states had adopted an ad valorem property tax system for land and other non-enslaved personal property and only five continued to use capitation taxes for slaves. The new state governments created by the Reconstruction Acts each adopted a uniform property tax system for all taxable property, and this system remained in place throughout the remainder of the period of our study.

As property tax systems became more sophisticated, and the structure of the economy developed, more classes of assets were included in assessed wealth. By the 1840s, most states included the value of money (deposits in banks), bonds (and to a lesser extent stocks), the value of commercial merchandise, and household items, such as jewelry, gold and silver watches, and furniture. In the postwar period, the property tax system enlarged to include the value of capital in banks, the assessed value of railroads, and manufacturing; there were even attempts to include intangible assets, such as patents and copyrights. Small exemptions (e.g., church property, the first $200–500, or 100 head of cattle) were common throughout the period.

The assessment of the value of taxable property was in the hands of local officials, and these valuations were used for property taxes at all levels (state, county, municipality, and special-purpose, such as school and levee districts). While local officials had the incentive to undervalue the assessments compared to true market values, the strategic under-assessment of property values was not a South-specific problem; it was endemic across the entire United States (e.g., Reference SeligmanSeligman 1969; Reference VollrathVollrath 2013).

3.1.1 Empirical Measures of Property Taxes

Our main measure of property taxes uses a combination of property taxes levied and collected. For the prewar period, the reports were much less detailed and few provided the amount of property taxes levied. Given the paucity of data on prewar property taxes levied (not to mention assessments of the value of taxable property), our prewar property taxes are primarily those collected into the treasury each year. For the postwar years, we generally use the amount of property taxes levied. This information is commonly provided in each report, and tables of annual property taxes levied for long periods (which increase our coverage) are often included. More importantly, it became typical that some state property taxes, especially those levied specifically for common schools (as pre-high school public schools were then called), were not received by the state treasury and therefore not recorded in our measure of property taxes collected. We think it is important to include all property taxes levied by the state government. We believe our measure of property taxes is comparable across states and periods, since we know of no instances in the prewar period in which state-levied property taxes did not go into the state treasury.

In general, we have excellent coverage across states and time in annual property taxes. For the 1,146 possible state-years in our sample, we have collected property taxes for 919 of them. For the eleven states that existed in 1820, there are 87 possible state-years each. We have at least 54 observations for each of them.Footnote 33 Unsurprisingly, the completeness of data improves over time. In the 1820s, we have property taxes for 45 of 110 possible state-years.Footnote 34 We have 64 of the possible 114 state-years in the 1830s. For the 1850s, we have 117 of 140 possible data points. We have 133 of 140 possible state-years in the last decade of our sample.

The period of our study, especially after the Panic of 1873, was characterized by substantial deflation. As a result, our measure of property taxes (as well as all variables collected in nominal dollars) is reported in deflated values.Footnote 35 Figure 3 shows the total property taxes in each state between 1820 and 1910. We smooth it using a three-year rolling average.

Figure 3 Total property taxes by state (million, real $), 1820–1910 three-year moving average

We normalize this measure of property taxes in two ways. First, we divide it by each state’s White population. We use White population rather than total population because even in the post-emancipation period, Whites owned almost all of the taxable property in Southern states.Footnote 36 The denominator is created using census data for each decade from 1820 to 1910 and performing linear interpolation for the intervening years.

Figure 4 shows the average across these fourteen states for property taxes per White capita (PWC) from 1820 to 1910. Initially, property taxes PWC were low, especially in the 1830s. They rose rapidly between the early 1840s and the onset of the Civil War in 1861. We see that they continued to rise during Reconstruction only to decline significantly once Reconstruction ends. The post–Black disenfranchisement or Jim Crow period saw the resumption of rapidly rising property taxes PWC. Figure 5 shows the amount of property taxes PWC by state from 1820 and 1910.

Figure 4 Property taxes per White capita (real $), 1820–1910 three-year moving average

Figure 5 Property taxes per White capita by state (real $), 1820–1910

Our second measure normalizes property taxes by the value of total agricultural and manufacturing output, as collected by each census between 1840 and 1910.Footnote 37 This attempts to measure taxes as a share of economic output.Footnote 38 As with the White population, we perform linear interpolation for the values between each census observation.

Figure 6 shows the average across these fourteen states for this measure. The primary difference is that rising taxation at the end of our period only keeps pace with rising economic output. Figure 7 shows property taxes as a share of output in each state.

Figure 6 Property taxes/agricultural and manufacturing output, 1840–1910 three-year moving average

Figure 7 Property taxes/agricultural and manufacturing output by state, 1840–1910

3.1.2 Ad Valorem Property Tax Rates

We complement our main measure of property taxes levied or collected with the ad valorem rates applied each year to taxable property. In the postwar period, this measure is straightforward. The Reconstruction conventions of 1867/8 established equal and uniform property tax systems in each Southern state. The ad valorem rate, therefore, is just the annual ad valorem rate as determined by the state government.Footnote 39 We use this annual rate for each year in the postwar period.

It is more difficult to report a consistent measure of property tax rates across each Southern state between 1820 and 1860. As mentioned, most states began the period setting fixed amounts to taxable property (e.g., land taxed by category, capitation taxes on slaves based on gender and age, fixed amounts for farm animals). By 1860, nine of the fourteen states had adopted systems that closely resembled the uniform property tax systems implemented during Reconstruction. We exclude states prior to their establishing uniform and universal property tax systems, so some states are not included in this measure during the prewar period. Furthermore, some changes over time in the average property tax rate during this period reflect composition effects, as states enter the data set only when they established a uniform property tax system.

Figure 8 shows the average ad valorem property tax rates across states between 1840 and 1910.Footnote 40 The pattern is strongly consistent with property taxes PWC and as a share of output as shown in Figures 4 and 6, respectively. It suggests that the increases in property taxes observed in the immediate prewar, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow periods, respectively, were due to the choice to increase property taxes; this is similarly true for the periods of declining property taxes.

Figure 8 Ad valorem property rate, 1840–1910 three-year moving average

3.1.3 Property Tax Incidence

The extreme wealth inequality of the South, combined with exemptions and the fact that most wealth was tied to slaves (pre-1860) and land meant that property taxes were probably mildly to extremely progressive, with much of the burden falling on planters (Reference WrightWright 1978; Reference Thornton, J. Morgan Kousser and JamesThornton 1982; Reference RansomRansom 2001). Although we lack the individual-level data necessary to confirm this supposition, we were able to decompose the property tax burden by economic sectors and by geographic regions within states to get a sense of whether the tax burden was shifted to urban areas or to rural areas disproportionately inhabited by poor Whites.

Figure 9 shows the proportion of total property taxes paid by the rural sector between the mid-1840s and 1910 for the eight states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee) where we can decompose tax burdens by sector – urban, rural, or undefined – across time.Footnote 41 The figure includes the rural tax share and a second line for the agricultural share of total output (comprising agricultural and manufacturing activities). Several things are worth noting. First, taxes on rural land and slaves alone exceeded 75 percent of the prewar property tax take on average across the eight states. Second, while the average share of agricultural output in these eight states falls from almost 90 percent in 1850 to less than 50 percent by 1910, the share of property taxes paid by the rural sector in these states closely mirrors its share of output throughout the entire period. Third, the rural share of property taxes diverges the most from the output share line when the planters are at their least powerful politically (during Reconstruction).

Figure 9 Agricultural output and exclusively rural share of property taxes (%) eight-state average 1846–1910

Figure 10 shows the share of total property taxes falling explicitly on urban/industrialist assets together with the manufacturing share of total output. While the share of property taxes borne by this emerging sector rises over time, it clearly does not keep pace with the industrial share of output, particularly after rural elites regain uncontested control in the late nineteenth century. Furthermore, the urban sector pays its highest share (and the rural sector its lowest share) relative to the trends in output shares during Reconstruction, precisely the period in which rural elites’ control was weakest. Combined, these two figures give no indication that changes in the levels of property taxes can be attributed to the ability of rural elites to disproportionately pass the burden onto the emerging industrial sector.

Figure 10 Manufacturing output and exclusively urban share of property taxes (%) eight-state average, 1846–1910

In a separate test, we examine the distribution of state property taxes levied in each county. We find that the association between Black population share and these taxes is not only consistently positive and statistically significant in each decade between 1860 and 1910, but also remarkably stable over time. The fact that the coefficients are strongly positive (and not negative or indistinguishable from zero) indicates that the spatial distribution of the tax burden remained skewed toward areas with a higher Black population share, which were also the areas inhabited by relatively wealthier rural Whites.

Finally, one concern may be that enslavers used the adoption of a uniform tax system to pass the incidence of taxation onto the assets of non-rural elites. We have the property tax by sector for three states before and after they switched to a full ad valorem uniform/universal property tax system (Florida, Georgia, and Louisiana). The rural sector’s share of property taxes increased from 82 percent to 92 percent in Florida, and from 69 percent to 77 percent in Georgia; in Louisiana, the share remained unchanged at exactly 79 percent.Footnote 42

3.2 Other Measures of Taxation

As mentioned, we also collected several other measures of taxation. Specifically, we include the total amount of tax revenues collected annually into the state treasury (1820–1910), poll tax rates levied (1820–1910), and total state and local property taxes levied between 1860 and 1910. These data show us the importance of focusing on property taxes to understand the incidence of taxation in the South between 1820 and 1910. We describe each of these measures in this section.

3.2.1 Total State Tax Revenues Collected

The first measure is the total amount of tax revenues collected each year into each state treasury. In addition to property taxes, this measure often includes poll taxes, occupation and licensing taxes (i.e., a license to operate a billiards hall or sell pianos), liquor taxes, and bank, insurance, and business taxes, among others. As stated, we prefer to focus on property taxes for two interdependent reasons. For one, we are interested in the incidence of direct taxation borne primarily by the rich, which included the relatively small planter elite that dominated Southern politics. Focusing on property taxes is also appropriate because they comprised most of total state taxes in this period (roughly 74 percent of total tax revenues).Footnote 43

3.2.2 Total State and Local Property Taxes Levied

We are, however, interested in the amount of property taxes levied by substate governments as well (i.e., counties, municipalities, and school districts). Unlike Northern states, where local taxation was much higher than state taxes (and was rising throughout the period of our study), taxation was much more centralized in Southern states, presumably reflecting the influence the small planter elite had not only over Southern politics but also over state constitutional design (Reference MargoMargo 2007; Reference Sun and LindertGo and Lindert 2010; Reference Chacón and JensenChacón and Jensen 2020a). The amount of local taxation was strictly limited, and in many cases prohibited (e.g., for school purposes).

Nonetheless, the levying of local property taxes occurred in each state. Unfortunately, no Southern state provided the amount of local taxation levied, especially not in a consistent, complete, or systematic way. We therefore rely on US Census Wealth, Debt, and Taxation reports from 1860 to 1912 for the amount of property taxes levied at the substate level approximately once every ten years. While much less complete than our state-level data, these data can tell us whether substitution effects contribute to the observed patterns in our state-level property tax data, rather than the factors emphasized by our argument. In general, during this period, local taxes rose rapidly in the rest of the United States while state taxation either stagnated or even declined (Reference WallisWallis 2000). Thus, it is plausible that our argument for why state-level property taxes declined in some periods may be capturing national trends.

As before, we normalize this measure of total property taxes levied by the White population and by agricultural and manufacturing output. The figures for each measure between 1860 and 1910 are shown in Figures 11 and 12, respectively. While we are unable to assess the prewar trends, postwar total state and local property taxes levied PWC and as a share of output, strongly resemble the patterns witnessed in state property taxes. Thus, despite growing urbanization and industrialization – especially in a few states with rapidly growing urban areas, such as Louisiana (New Orleans), Maryland (Baltimore), and Missouri (St. Louis, Kansas City) – it appears that the factors influencing state taxation were likely similar to those determining local property taxation.

Figure 11 Local and state taxes/White population (real $, fourteen-state average), 1860–1910

Figure 12 Local and state taxes as a share of agricultural and manufacturing output (fourteen-state average), 1860–1910

3.2.3 Poll Tax Rates

Last, we collected the poll tax rate levied on eligible adult males in each state between 1820 and 1910, which we use as a generic proxy for taxes on lower-income groups. Poll or capitation taxes are highly regressive (as an equal tax is levied on each eligible resident regardless of means), and a few states (e.g., Maryland) constitutionally forbid them.Footnote 44 During the period under consideration, most states constitutionally required that poll tax revenues be used only on common schools in the county in which they were collected (except Texas, which allowed one-third of poll tax revenues to be used for general revenue). In most states, state treasurers did not collect the tax, and in no case did we include them with property or state tax totals. In the 1890s (Jim Crow), Southern states began instituting specific links between poll tax payments and voting rights, disenfranchising thousands of potential voters, notably Blacks.Footnote 45

Importantly, the types of tax-vote links that emerged in the South during Jim Crow are fundamentally different from those observed in other settings, such as the Prussian case studied by Reference Mares and QueraltMares and Queralt (2015), as are their implications for elite incentives. During the period of our study (1820–1910), most Southern states did not have electoral rules that conditioned voting rights on tax payments and, when they did, the right to vote was tied to the payment of the poll tax – which is not a property tax, and therefore not part of our dependent variable.Footnote 46 According to Mares and Queralt, the presence of a vote-tax link increases the incentives of elites to raise those taxes that condition political participation in order to disenfranchise the poor. In the US South, rural elites restricted political participation of low-income groups, targeting Blacks in particular, through a variety of mechanisms unrelated to the property tax. Furthermore, the poll tax was a trivial source of revenue.Footnote 47 In other words, our argument and evidence elucidate why agrarian elites increased taxation on themselves even when these taxes could not be used as barriers to political participation.

This measure of poll tax rates attempts to capture whether rises or declines in property taxes, which are borne primarily by a small elite, accompany changes in poll taxes, which fall most heavily on the electorate more broadly. Since the rate reflects a monetary value, we deflate this measure. States that did not levy a poll tax are coded as zero.

Figure 13 shows the average poll tax across these states from 1820 to 1910. Poll taxes on Whites are significantly lower in the prewar period. In the postwar period, when these taxes were primarily allocated to common schools, they are higher but unchanging.Footnote 48 It is evident that changes in poll tax rates do not follow the patterns exhibited by property taxes, ad valorem property tax rates, or total tax revenues.

Figure 13 Poll tax rate (fourteen-state average), 1820–1910 three-year moving average

3.3 Other Data

We briefly describe other data used to assess our argument.

3.3.1 Public Spending and Collective Goods

Our argument states that elites will support increasing property taxation if they have political control and valuable collective goods exist that can further their economic interests. Thus, any test of our argument must include evidence on the types of spending in which the state was engaged. While not as complete as our taxation data, we include two measures of collective goods that elites clearly valued in particular periods of our study. For the prewar period, we examine public spending on railroads. In the post-Reconstruction period, we use an original data set of state public spending on colleges and universities between 1880 and 1910. We contrast this with public spending on a redistributive good that should be more coveted by poorer residents: state spending on common schools. We describe each of these measures in more detail in what follows.

3.3.2 Demographic, Economic, and Political Variables

We use several additional demographic, economic, and political variables primarily as controls. Most controls come from the various decennial censuses between 1820 and 1910. These include once-a-decade values for population (White, Black, and enslaved until 1860), the urbanization rate (share of a state’s residents living in cities of 2,500 or more people), and economic output (agriculture and manufacturing). For each measure, we use linear interpolation for the non-decennial years. From Reference DubinDubin (2007), we created several measures of partisan competition and composition of each state’s legislature over time. Appendix B details each variable (i.e., sources and operationalization).

4 Property Taxes before the Civil War

We first test our argument about the importance of political control for elites and their demand for collective goods in the prewar period. We exploit the presence of a lasting international commodity price shock, which increased the value of production and therefore the demand for capital-intensive infrastructure by slaveholding elites. The key to increasing production was constructing a railroad network that would allow for the cultivation of lands that were too far from navigable water to profitably use enslaved labor. This would require extensive increases in public revenues to finance such a network in the vast and sparsely populated South. We contend that elites will support increasing taxation only if they control spending and this control of political power is likely to persist. We argue that variation across states in state legislative apportionment rules – which gave disproportionate influence to large slaveholders in the legislatures of some states but not others – meant that elites in the malapportioned states enjoyed greater political control and would therefore have stronger incentives to support increasing taxation.

Indeed, we show that: 1) the rise in property tax revenues PWC and as a share of output, respectively, were substantially higher in states where legislative malapportionment provided the plantation class with a firmer grip on enduring political power; 2) property tax rates in the malapportioned states (MS) rose faster than those in the non-malapportioned states (NMS); 3) regressive poll taxes, which were levied more broadly across the White population, did not increase faster in the MS; and 4) increased revenue was allocated toward collective goods that furthered the economic interests of slaveholders (railroads) and not toward goods (public education) that would benefit the White population more generally.Footnote 49

4.1 Property Taxes between 1820 and 1860

Our period begins in the 1820s, at which point there were eleven Southern states. As chattel slavery moved westward into the Southwest Territory (area won in the 1783 Treaty of Paris from the UK) and the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase (area acquired from France in 1803), the original five coastal British colonies were joined as states by Kentucky (1792), Tennessee (1796), Louisiana (1812), Mississippi (1816), Alabama (1819), and Missouri (1821). As shown in Figure 4, property taxes PWC collected in the 1820s were low compared to any time after 1845. Beyond some critical functions, such as courts and the enforcement of enslaved property rights (i.e., regulation of slave patrols and the state militia), the infrastructural capacity of these states was minimal and the governments did relatively little. There was very little systematic funding for public education or infrastructure such as canals and turnpikes.Footnote 50

Yet, even at this low level of public spending, property taxes on average would decline even further in the 1830s. In an economic boom spurred on by substantial land speculation and a commodity bubble, state governments found alternative nontax sources of revenue. In particular, states successfully used their monopoly power on the incorporation of banks to generate rent profits that poured into the state treasury as dividends (Reference WallisWallis 2005). In addition to revenues gained from taxes on and dividends from state banks, substantial additional revenues came from land sales, loans, and even briefly the surplus revenue paid out by the federal government in 1836. These temporary windfalls even led some states, such as Alabama, Georgia, and Maryland, to eliminate property taxes altogether. The loans taken on by Southern states in particular financed so-called land banks, used primarily by enslavers to finance the speculative boom in land and slaves of this period (Reference WallisWallis 2005).

The Panic of 1837 ushered in roughly seven years of deflationary and economically depressed conditions. The long-lasting downturn caused debt defaults across the economy, including on the state debt of four Southern states (Arkansas, Louisiana, Maryland, and Mississippi), as well as the territory of Florida. Sources of nontax revenue evaporated and states needed to raise tax revenues to finance their debts and fund government operations.

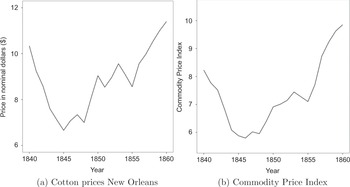

While the increase in property taxes between the mid-1840s and the onset of the Civil War that is apparent in Figures 4 and 6 may capture some of the need to finance debts, this period also coincided with a substantial increase across Southern states in public spending on railroads (Reference HeathHeath 1950; Reference FishlowFishlow 1965; Reference GoodrichGoodrich 1974). In turn, this period witnessed a sustained boom in the international demand for Southern cash crops that relied on enslaved labor, notably cotton. In both New Orleans and Liverpool, the primary international market for cotton, the price of “Middling American cotton” and sugar more than doubled between the mid-1840s and late 1850s. Tobacco prices in Liverpool rose more than threefold between 1843 and 1857 (Reference Gray and ThompsonGray and Thompson 1933, p. 492, 1026, 1033–1038). Figure 14 shows how the rising demand for Southern export crops affected commodity prices between 1840 and 1860. Specifically, Figure 14 (a) shows the five-year moving average of cotton prices in New Orleans from 1840 and 1860; Figure 14 (b) shows the five-year moving average of a commodity index reflecting variation in cotton, sugar, and tobacco prices over the same period.

Figure 14 Cotton prices ($) and Commodity Price Index, 1840–1860 (five-year moving average)

These price increases coincided with a production boom in these crops. Southern cotton production exceeded 2.2 billion pounds in 1860, up from less than 800 million in 1840. Sugar production also nearly tripled over this period (Reference Gray and ThompsonGray and Thompson 1933, p. 1033), while tobacco exports rose almost fivefold (Reference Gray and ThompsonGray and Thompson 1933, pp. 1033–1036).

Surging international prices and rapidly rising production enriched the relatively small group of Southern enslavers. For instance, the value of cotton exports rose from approximately $50,000,000 in 1846 to nearly $200,000,000 by 1860 (Reference NorthNorth 1960, p. 233).Footnote 51 As stated by Reference RansomRansom (2001), “There could be little doubt that the prosperity of the slave economy rested on its ability to produce cotton more efficiently than any other region of the world.” In turn, international demand for cash crops and the increased ability of Southern enslavers to meet this demand strongly influenced the value of their enslaved property. To wit, the late 1830s and 1840s depression in cotton prices was followed by declines in the average value of slaves, as captured by prices of major Southern slave auctions. As shown in Figure 15, the surge in international prices for cash crops was similarly followed by rapid increases in the value of slaves.

Figure 15 Average prices of enslaved persons

While the desire to meet rising international demand for these cash crops was clearly in enslavers’ economic interest, the limitations of the existing infrastructure network severely constrained their ability to do so. Millions of acres of otherwise fertile land went uncultivated due to their distance from navigable waters, rendering the use of expensive enslaved labor unprofitable. As was the case for non-slaveholders across the United States, substantial investments in infrastructure, such as canals and railroads, were necessary to connect vast amounts of potential farmland to markets. Furthermore, the lack of investment in infrastructure was an important source for Southern underdevelopment compared to the North (Reference WrightWright 2022).