1 Setting the Stage

1.1 Background

Long-term economic development depends critically on productivity growth. A key mechanism behind this growth is the movement of workers from less productive to more productive activities. Historically, the manufacturing sector has played a central role in this process of structural transformation. Manufacturing offered abundant opportunities for capital deepening, economies of scale, and technological advancement. Many studies show that countries that successfully narrowed the income gap with richer nations did so through sustained industrialization. Typically, these successful economies began by exporting labor-intensive goods from light industries, such as textiles, and over time shifted toward exporting capital- and skill-intensive goods from heavy industries, such as machinery. In contrast, countries that failed to industrialize (or whose industrialization stalled) have struggled to achieve lasting income growth.Footnote 1 These patterns have fueled persistent policy debates about the weak pace of industrialization in many low- and middle-income countries, and have led to a renewed focus on industrial policy, trade integration, and the expansion of manufacturing as potential engines of economic growth.

However, it is increasingly recognized that industrialization and manufacturing exports are no longer the exclusive pathways to development. Gollin and Kaboski (Reference Gollin and Kaboski2023) argue that not all recent episodes of economic growth have been driven by industrialization, and that manufacturing booms do not automatically lead to sustained progress. Similarly, Newfarmer, Page, and Tarp (Reference Newfarmer, Page and Tarp2018) highlight the potential of “industries without smokestacks” – sectors like agro-processing, horticulture, tourism, and business services – that can create productive jobs, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Meanwhile, advances in digital technology have made many services more tradable across borders, creating new opportunities for export-led growth (Baldwin and Forslid, Reference Baldwin and Forslid2019). Gollin (Reference Gollin2018) further argues that modern service sectors increasingly exhibit characteristics once thought to be unique to manufacturing, including knowledge spillovers, economies of scale, and agglomeration effects. Baccini et al. (Reference Baccini, Fiorini, Hoekman and Sanfilippo2023) add that services play a growing and substantial role in employment, skills development, and broader economic progress in Africa. As Gollin (Reference Gollin2018) concludes, “Although manufacturing exports have been an important source of growth for the ‘miracle’ economies of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, there is little reason to believe that this is an exclusive pathway to growth and poverty reduction.”Footnote 2

At the same time, the traditional link between export success and structural transformation has weakened. Global trade opportunities have radically changed. Improved information and communication technologies allow lower-income countries to participate in global markets by specializing in discrete stages or “tasks” of production. Industrialization through exporting now appears easier than before, often requiring fewer domestic capabilities from firms and relying more on macroeconomic stability and access to international markets (Baldwin, Reference Baldwin2016; World Development Report, 2020).

Yet while entering export markets may have become easier, the developmental payoff of exports has diminished. Increasingly, exports rely heavily on imported intermediates, reducing the share of domestic value added. Lall (Reference Lall2000) noted this trend early on, pointing out that while “high-technology” products like semiconductors appear identical in trade statistics, the underlying domestic activities differ dramatically: sophisticated processes in the United States contrast with basic assembly work in Malaysia. Traditional trade data does not capture these differences because they record only the final product, not the complexity or value added at each stage of production. Since products do not map cleanly onto specific tasks, understanding the trade-structure-growth relationship now calls for a focus on tasks.

Investigating this task-based view of structural transformation and trade is the central goal of this Element.

1.2 Scope and Aims of This Element

The central premise of this Element is that structural change is best understood through the lens of tasks. This idea echoes the classical model of Lewis (Reference Lewis1954), which describes structural transformation as the movement of labor from traditional to more productive modern activities. Importantly, Lewis emphasized that modern, productive activities could be found outside of manufacturing, and also noted that significant pockets of low-productivity, often informal, work persisted even within the manufacturing sector itself (Lewis, Reference Lewis1979; Diao and McMillan, Reference Diao and McMillan2018). These insights suggest the need for a deeper understanding of the types of activities countries perform, and how specialization in different tasks evolves as economies develop.

We demonstrate the usefulness of a task-based perspective by presenting new empirical evidence on trade and development. To do this, we introduce new data and analysis that reveal the heterogeneity of tasks within exports across industries and countries. We show how trade in tasks can be measured using recently developed data from internationally harmonized statistics, which we have built over the past decade. Throughout this Element, we employ a consistent methodology and dataset to ensure the comparability and coherence of the empirical findings across sections. Where appropriate, we draw on our own previously published research, updating results and discussions to reflect new evidence and developments.

A task-oriented approach to trade and structural change is essential for improving our understanding of economic development and the role of policy. The distinction between an industry or product perspective and a task perspective becomes particularly salient in discussions about industrial policy. Industrial policy seeks to avoid the risk of economies becoming trapped in suboptimal equilibria, often due to externalities and production spillovers. This concern is central to the product space framework (Hausmann et al., Reference Hausmann, Hidalgo, Bustos, Coscia and Simoes2014), which has gained popularity in evaluating a country‘s growth potential and in shaping trade and industrial policies for lower-income countries (Hidalgo et al., Reference Hidalgo, Klinger, Barabási and Hausmann2007; Hausmann and Klinger, Reference Hausmann and Klinger2007; Hausmann et al., Reference Hausmann, Hidalgo, Bustos, Coscia and Simoes2014; Coniglio et al., Reference Coniglio, Vurchio, Cantore and Clara2021).

According to the product space paradigm, policymakers should pursue a gradualist strategy by promoting the introduction of new products that are “close” to the country’s existing capabilities, thus minimizing the risk of failure. Introducing radically new products would require capabilities that are scarce and difficult to build. However, industrial policies can also play a role in overcoming information spillovers associated with discovering new profitable activities, as Hausmann and Rodrik (2003) argue. Because the cost structures of new products are unknown, countries’ latent comparative advantages remain hidden and must be uncovered through costly experimentation – experimentation whose social benefits exceed private returns. In such contexts, policies that promote discovery and diversification can boost productivity and growth (Harrison and Rodríguez-Clare, Reference Harrison, Rodríguez-Clare, Rodrik and Rosenzweig2010).

Historically, mainstream economists viewed industrial policy with skepticism, largely because it was associated with inward-looking, protectionist trade strategies. However, recent research calls for a more nuanced and context-specific understanding of industrial policy’s practice and effects (Juhász, Lane, and Rodrik, 2023). Similarly, Sen (Reference Sen2023) argues for a rethinking of traditional views on structural transformation and calls for greater creativity in developing countries’ policy choices today.

In this Element, we argue that adopting a task perspective enhances our understanding of how trade, structural change, and economic growth are linked, and clarifies the role of policy in these processes.

Our main aim is to demonstrate the versatility of the task perspective in offering new insights into long-standing debates. Structural transformation and growth are broad subjects, touching multiple fields, including growth and development economics, international trade, labor economics, economic geography, and international business. Our task-based approach connects these fields and highlights their interrelationships. Nevertheless, given the rapid pace at which research in these areas is evolving, we cannot cover all relevant debates comprehensively. Throughout this Element, we aim to offer a focused and coherent discussion, while directing readers to related literatures for further exploration.

1.3 Structure of the Element

The remainder of this Element is organized into six sections.

Section 2 introduces our task perspective on trade and development. We define the concept of a task, provide an illustrative example, and explain how a task-based view relates to traditional product-based perspectives on trade and structural change. Task exports are estimated by measuring the value-added contribution of workers, cross-classified by occupational class and industry of employment. A detailed mathematical exposition of the measurement methodology, along with a description of the new task dataset we developed, is provided in the Appendix.

Sections 3 and 4 present the basic descriptive evidence.

Section 3 characterizes long-term shifts in the international division of tasks within the global production network for manufactured goods. It offers a stylized overview of how countries’ contributions have evolved over recent decades, distinguishing between low-skilled production tasks and high-skilled knowledge tasks. Put simply, it addresses the question of “who has been doing what” in the so-called “global factory.”

Section 4 zooms in on how the structure of exported tasks changes with economic development. Using detailed data that identifies 455 distinct tasks for each economy-year, cross-classified by occupation and industry, we describe how task specialization evolves both across industries (e.g., from textiles to electronics) and within industries (e.g., from craft workers to engineers). This approach provides a richer and more nuanced picture than traditional analyses focused solely on sectoral shifts.

The next two sections provide more formal empirical analysis.

Section 5 examines the path dependence of task specialization. We introduce a task specialization index that measures a country’s comparative advantage in specific tasks, and analyze how task specialization patterns evolve over time within countries. Using a probit model, we test for the degree of path dependence in countries’ specialization trajectories.

Section 6 explores the relationship between economic growth and the introduction of radically new tasks. We measure the appearance of new task specializations in countries’ export structures and incorporate this concept into growth regressions to assess whether diversifying into new types of tasks is associated with better economic performance.

Finally, Section 7 summarizes the main findings of this Element and discusses future research directions. We reflect on how the task perspective sheds new light on long-standing debates in development economics and trade policy.

2 A Task Perspective on International Trade, Structural Change, and Economic Development

A country’s specialization evolves over time, resulting in new products being added to the country’s export basket. Lack of export development is a long-standing concern as it appears to be linked with slower structural change and productivity growth. We argue that analyzing what a country does in trade (i.e., the tasks it performs) provides additional insights vis-à-vis analyzing the products that a country trades. This section presents key concepts of our task perspective and will be useful for proper interpretation of our findings in the remainder of the Element.

2.1 Development of Data on Trade in Value Added

The study of international trade specialization traditionally relies on analyzing countries’ gross export flows. A country’s specialization in a product is determined by comparing its share in the country’s overall exports to its share in global exports, known as the Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) index. RCA values above 1 reveal that the country is better at producing a product compared to other countries (Balassa, Reference Balassa1965). RCA indices are used to test various trade theories, in particular those relying on differences in factor endowments in the tradition of Heckscher-Ohlin.Footnote 3 To that end, products are often categorized based on their industries’ factor input intensities, for example, whether the production process of the product makes intensive use of natural resources, (un)skilled labor, or capital. Endowment differences used to help explain product specialization patterns between regions, particularly between rich and poor countries as the latter specialize in less skill and capital-intense products (Leamer, Reference Leamer1984; Hanson, Reference Hanson2012). Schott (Reference Schott2004) further refined this understanding by analyzing US import data, revealing specialization at an even more granular level. His work suggests that developed countries tend to specialize in higher-quality goods within narrow product categories, while developing countries focus on lower-quality alternatives.

Clearly, the rise of global production networks and the integration of emerging economies like China and India into the world economy pose a challenge to traditional trade analysis based on products. Lall (Reference Lall2000) pioneered the recognition that the international division of labor complicates the interpretation of trade statistics based solely on product descriptions. He laments that product export data “ … does not indicate the process involved in making the same product in different locations. Thus, a high technology product like semiconductors can involve genuinely high-tech processes in the United States and relatively simple assembly in Malaysia. In our data, both would appear equally technologically advanced. … we cannot deal with this in any consistent manner” (Lall, Reference Lall2000, p. 340).

Subsequent research has shown that this problem became more profound in the 2000s with further international slicing of production. Yet trade researchers also responded to Lall’s challenge on the ability of trade statistics to capture the new situation. His pessimism appeared to be overstated. Hummels et al. (Reference Hummels, Ishii and Yi2001) introduced the concept of “vertical specialization in trade,” which measures the extent of international production fragmentation by calculating the share of domestic value added (DVA) in gross exports. Domestic value can be added in production by the exporting industry as well as other so-called upstream domestic industries that provide inputs. The DVA concept builds on Leontief’s (Reference Leontief1953) work using information on input-output linkages between local industries. Essentially, DVA captures how much of a country’s export value is actually produced domestically versus how much value is imported and subsequently re-exported.

Johnson (Reference Johnson2014) highlighted the growing gap between a country’s gross exports and value-added contributions across different sectors. He emphasized the importance of considering upstream production stages, as these stages often involve substantial value addition that is not captured when looking solely at the industry that is exporting. Koopman, Wang, and Wei (Reference Koopman, Wang and Wei2012) provide a concrete example of this phenomenon by examining Chinese exports of complex goods, such as electronic devices. They find that these exports had a relatively low domestic value-added content because China relied heavily on imported components for their production in the early 2000s. This reliance on imported inputs meant that a substantial part of the value of these exports was actually created outside of China at the time. Koopman, Wang and Wei (2014) showed how domestic value added measures impacted traditional measures of revealed comparative advantage.

Johnson and Noguera (Reference Johnson and Noguera2012, Reference Johnson and Noguera2017) expanded on this idea by documenting the rise of vertical specialization across thirty-six out of thirty-seven countries they studied. Countries were increasingly participating in global value chains, where production processes are spread across multiple countries. They found that the global ratio of value added to gross exports declined by 10 percentage points from 1970 to 2008, with a notable acceleration in this trend after 1990. This phenomenon was dubbed the emergence of trade in value added. Further research in trade in value added has created a broader set of global value chain (GVC) measures, facilitated by multicountry input-output data initiatives that are grounded in national accounts,Footnote 4 like the World Input-Output Database (ggdc.net), the OECD-WTO Trade in Value Added (TiVA) project (oe.cd/tiva), and the ADB MRIOTs (kidb.adb.org/mrio), as reviewed in Johnson (Reference Johnson2018).

2.2 The Need for Data on Trade in Tasks

The new research findings on trade in value added implied that countries may specialize in different stages of production, with different factor intensities, even when they appear to be exporting similar products. A small value-added contribution in exports could signify either low-tech assembly or high-tech manufacturing of complex components. For instance, a developing country might engage in the assembly of electronic products, importing components like circuit boards, casings, and wiring, and focusing on assembling these parts into final products. In contrast, a high-income country might be involved in the production of semiconductors, which requires advanced skills and precision engineering, importing all other components. Although the share of domestic value added in exports might be small in both cases, the nature of the tasks performed is vastly different. Moreover, a country can specialize in tasks without altering its domestic value-added ratio. For example, consider the United States, which initially produced entire cars domestically. If the United States shifts its focus to exporting only car parts to Mexico, where these parts are assembled into complete vehicles and then re-exported, the domestic value-added share in US exports remains at 100%. This is because the value added by the United States in producing the car parts is fully captured in the export value, even though the final assembly occurs elsewhere. This scenario illustrates how a country can specialize in upstream production stages – such as manufacturing components – without changing the proportion of domestic value added in its exports. These examples show that trade in value added potentially severs the link between domestic factor endowments and the type of products exported, the hallmark of old-style empirical trade research (Baldwin and Robert-Nicoud, Reference Baldwin and Robert-Nicoud2014).

To gain a better understanding of a country’s position in global production networks and its development potential, information on the types of tasks carried out in exporting is needed. Therefore we developed new measures and data that gave empirical content to the task perspective on trade. To this end we had to bring in new information on the type of activities performed in the economy. Traditional distinctions along the industry dimension (e.g., agriculture, textile manufacturing, electronics manufacturing) no longer served the purpose as tasks tend to vary both across and within industries.Footnote 5 A prominent example is the trend known as the “servicification of manufacturing.” Administrative data typically classifies establishments by their primary activity, which contributes most to value added. However, establishments often perform multiple activities, both material and service-like. For instance, some manufacturing firms in rich countries were shifting toward service exports, such as machinery installation and maintenance, as noted by Kelle (Reference Kelle2013). These firms not only produce goods but also offer complementary services that enhance the value of their products and meet the evolving needs of their customers. This shift allows manufacturing firms to diversify their revenue streams and leverage their expertise in new ways. This trend highlights the increasing integration of services into traditional manufacturing processes and the blurring of industry classifications.

Additionally, the rise of so-called factory-less goods producers represents another important development. These firms, as described by Bernard and Fort (Reference Bernard and Fort2015), design products and manage production networks without engaging in the actual fabrication process. Instead, they outsource the manufacturing to third-party producers, often located in different countries. This allows factory-less goods producers to focus on tasks with high returns to factor inputs such as research and development, design, and supply chain management, while leveraging the manufacturing capabilities of specialized partners.

These examples illustrate the dynamic nature of modern industrial activities, where the boundaries between manufacturing and services are increasingly blurred. The servicification of manufacturing and the emergence of factory-less goods producers underscore the importance of understanding the diverse range of tasks that establishments perform, beyond their primary industry classification. A task perspective on trade needs information on the type of activities that takes place in the domestic economy in the production for exports. In this Element we show how various administrative statistical sources can be combined in order to measure trade in tasks, building upon the methodological approach of trade in value added.

2.3 Definition and Measurement of Trade in Tasks

How to measure the task content of trade? A useful starting point is to examine the occupations of the workers involved in exporting. Why? Because an individual’s occupation provides insight into the specific activities they perform, such as assembly, engineering, or sales, and, by extension, the nature of the country’s contribution to global value chains. As argued earlier, activities will vary across and also within industries. Therefore, in this Element we use data on workers that is cross-classified by occupational class as well as industry of work and call this industry-occupation pair a “task.” This in line with the terminology in the international trade literature (see, e.g., Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg, Reference Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg2008; Baldwin and Robert-Nicoud, Reference Baldwin and Robert-Nicoud2014). Information on tasks provide a natural way to bridge a country’s endowments in terms of skills and capital with the factor content of its export basket.

This subsection outlines the measurement of trade in tasks and provides an illustrative example. Box 1 provides a summary of the key terms used.

Product. A unique final good or service that is produced through a series of tasks. Tasks may be carried out in different countries due to international production fragmentation.

Industry. A person’s regular industry of work, classified using the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC).

Occupation. A person’s regular profession, classified using the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO).

Task. The expression “task” is used to indicate the activity of a worker as identified by the industry of a person’s regular work (ISIC) cross-classified by the person’s profession (ISCO).

Trade specialization in tasks. A country is said to specialize in a particular task when the task income share in its overall income from exporting is higher than the corresponding share for other countries (Timmer et al. Reference Timmer, Miroudot and de Vries2019). This is a variant of the Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) index of Balassa (Reference Balassa1965).

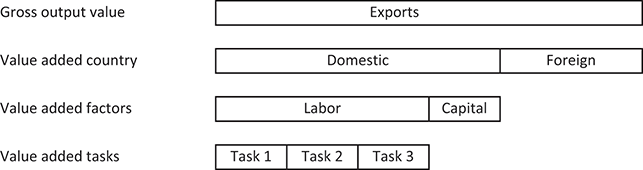

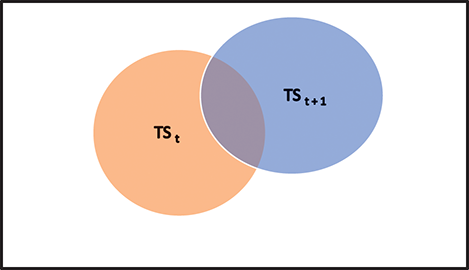

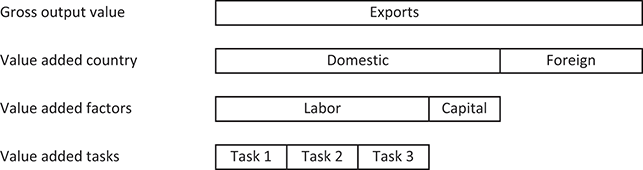

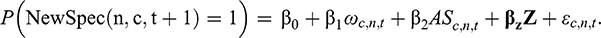

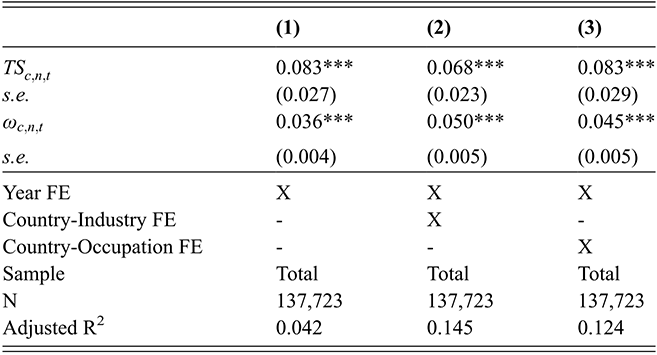

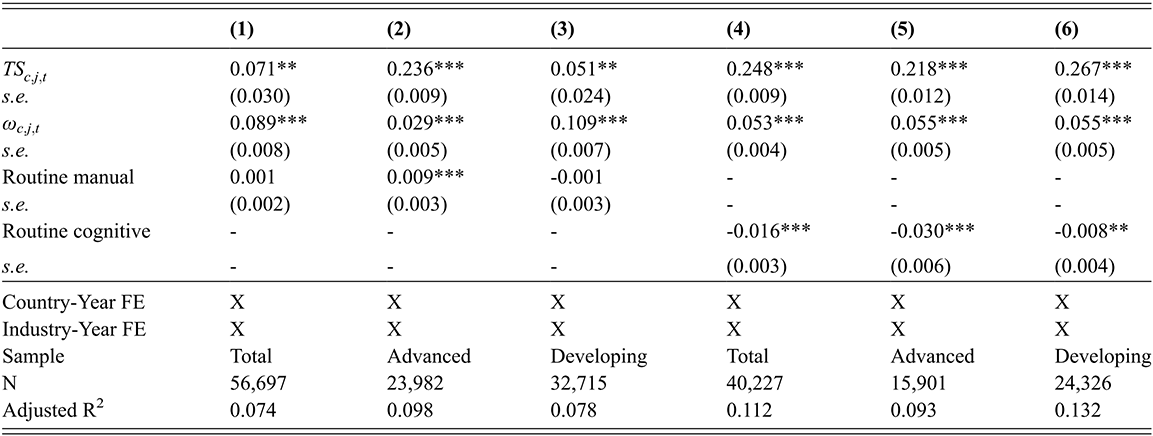

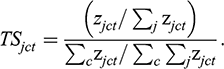

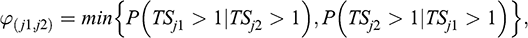

To give empirical content to the trade in task concept, we built upon the earlier work on trade in value added. Hummels et al. (Reference Hummels, Ishii and Yi2001) introduced a novel metric for measuring “vertical specialization in trade.”Footnote 6 This metric is defined as the share of domestic value added in gross exports. A share of one indicates that all tasks required to produce exports are conducted within the exporting country. To accurately track this share, it is necessary to supplement product export statistics with information on value added. This value added encompasses contributions from both the exporting industry and other domestic industries involved in upstream stages of production. To achieve this, Hummels et al. (Reference Hummels, Ishii and Yi2001) utilize a methodology originally developed by Leontief (Reference Leontief1953).Footnote 7 Building on this framework, we follow Timmer et al. (Reference Timmer, Miroudot and de Vries2019) and Kruse et al. (Reference Kruse, Timmer, de Vries and Ye2024) by further distinguishing the value added by different types of workers, cross-classified by occupation and industry, enabling the analysis of trade in tasks. Basically, we break down domestic value added into domestic value added of various tasks; see Figure 1.

Figure 1 Decomposition of gross output value of exports into value added contributions

The measurement involves two major steps. In the first step, we track domestic value added in exports, encompassing contributions not only from the exporting industry but also from other domestic sectors indirectly involved through intermediate inputs. To accurately account for these indirect contributions, input-output tables are essential as these track intermediate input flows across industries. In the second step, we further develop this approach by identifying the types of workers, characterized by occupation and industry of work, involved in the production process. Thus we break down domestic value added in exports into value added in various tasks, using information on the income of workers involved. Appendix A provides the mathematical formulation of input-output analysis used to measure trade in tasks.

In total 455 tasks are identified for each country in each year, cross classifying workers not only by their occupational class but also by their industry of work (455 = 13 occupational classes x 35 industries; see Appendix B for a description of the data). Bringing in this granularity is important as the addition of an industry dimension enhances the ability of occupational statistics to capture different types of activities. Compare for example the activities performed by machine operators in textiles and in electronics. Detailed O*NET data indicates that “making decisions and solving problems” is a very important activity for machine operators in electronics, while it is much less important for machine operators in textiles manufacturing.Footnote 8

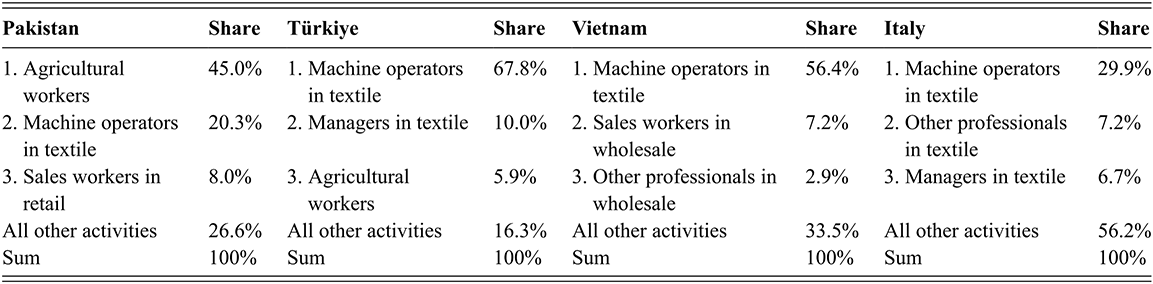

Table 1 provides an illustrative example from Kruse et al. (Reference Kruse, Timmer, de Vries and Ye2024) to aid intuition on the type of data that is used in this Element. The table shows the contribution of various domestic tasks in exports of textile for four countries at different levels of development. Note that tasks can be carried out by different occupational classes of workers in the textile industry, such as machine operators, managers or other professionals. In addition, tasks can also be carried out by workers in other industries producing material or service inputs for the textile industry, such as workers in agriculture or in wholesale and retail trade. The use of input-output linkage information ensures that these indirect contributions are taken into account as well. Referring to Figure 1, tasks can also be imported, which represents foreign value added in exports. Hence, the task contributions in Table 1 are expressed as shares of total domestic value added in a country’s exports.

| Pakistan | Share | Türkiye | Share | Vietnam | Share | Italy | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Agricultural workers | 45.0% | 1. Machine operators in textile | 67.8% | 1. Machine operators in textile | 56.4% | 1. Machine operators in textile | 29.9% |

| 2. Machine operators in textile | 20.3% | 2. Managers in textile | 10.0% | 2. Sales workers in wholesale | 7.2% | 2. Other professionals in textile | 7.2% |

| 3. Sales workers in retail | 8.0% | 3. Agricultural workers | 5.9% | 3. Other professionals in wholesale | 2.9% | 3. Managers in textile | 6.7% |

| All other activities | 26.6% | All other activities | 16.3% | All other activities | 33.5% | All other activities | 56.2% |

| Sum | 100% | Sum | 100% | Sum | 100% | Sum | 100% |

Notes: Entries show for each country the contribution of the top-3 tasks in the exports of textiles in 2018 (in percentages of total export value). Tasks are classified by industry of work and occupational class of workers. The penultimate line reports the contribution of the other tasks outside the top-3. Contributions to the textiles exports are based on the labor income of domestic workers involved in each task. Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Task specialization differs widely across the four selected countries. Tasks by machine operators in the textile industry make up more than two-thirds of domestic value-added exports in Türkiye. In Vietnam machine operators in textiles also contribute the most, but there is also a sizeable contribution from sales workers and other professionals in the wholesale trade industry. Textile workers accounts for less than one third in Italy. The value of Italian textile exports is mostly generated outside the textile industry by workers in services sectors such as distribution and marketing. Yet, different again, in Pakistan agricultural workers account for the largest share in textile exports as local cotton is a major input. Clearly, the task content of textile exports vary widely across countries and there is no unique mapping of exported products into exported tasks.Footnote 9

This is suggesting potential for new insights on trade, structural change and development when using a task perspective. The task trade statistics inform directly on the use of a country’s factor inputs and their returns. And more generally, they point at the potential for knowledge spillovers and the likelihood of productivity growth in trade activities. As such, our research is part of an emerging literature that examines macro issues of structural change and growth while taking account of heterogeneity of individuals, households, firms and locations within economies (Gollin and Kaboski, Reference Gollin and Kaboski2023). The next sections provide descriptive evidence and formal analysis of trade in tasks. The final section in this Element will discuss how a task perspective on trade and structural change may initiate several interesting lines of research, and inform current development debates.

2.4 Further Clarifications

A proper understanding of task trade measures is instrumental for prudent use and interpretation in research. This subsection provides a number of general remarks concerning the definition and measurement of trade in tasks. Other more technical remarks have been relegated to Appendix C.

First, our use of the term tasks is closely related to terms like “business functions,” a term used often, for example, in international business and economic geography literature to denote activities in global value chains, such as R&D, sales, or logistics activities; see for example Duranton and Puga (Reference Duranton and Puga2005), Defever (Reference Defever2012), Timmer et al. (Reference Timmer, Miroudot and de Vries2019), and Cirera et al. (Reference Cirera, Comin and Cruz2023). Multinational firms typically organize their activities around these functions due to internal economies of scale (Porter, Reference Porter1985); hence, it constitutes a relevant level of both firm- and country- analysis as we argue in Section 3. Leading economic models of production, such as Acemoglu and Autor (Reference Acemoglu, Autor, Ashenfelter and Card2011), tend to favor the term task to describe units of work within firms and we follow this practice.

Second, the trade in task approach offers opportunities to further characterize and assess the demand for particular workers given ongoing developments in automation and digitalization (Acemoglu and Restrepo, Reference Acemoglu and Restrepo2019). A common and useful approach is to classify the duties of workers according to the level of routineness. Routine tasks are typically repetitive, predictable, and codifiable, making them particularly vulnerable to automation and offshoring. In contrast, nonroutine tasks involve problem-solving, creativity, and adaptability, often requiring interpersonal interaction and autonomous decision-making. Accordingly, this strand of research emphasizes the degree of routineness in work of laborers in a particular occupational class (Autor et al. Reference Autor, Murnane and Levy2003). Labor demand models typically simplify this relationship by assuming a one-to-one mapping between occupations and tasks, whereby each task corresponds to a single occupation, and each occupation performs only that task (see, e.g., Goos et al. Reference Goos, Manning and Salomons2014). Under this assumption, occupations are treated as either entirely routine or entirely nonroutine. The task-based definition used in this Element, constructed at the occupation cross industry level, provides the opportunity to follow this logic in further research. In Section 5 we explore this idea.Footnote 10

Third, task trade measures are constructed on the basis of existing official administrative sources which were not specifically designed for that goal.Footnote 11 Value added includes compensation for workers and a gross operating surplus that accrues as income to the owners of capital assets, both tangible and intangible assets (see Timmer et al., Reference Timmer, Erumban, Los, Stehrer and de Vries2014; and section 3). Yet, capital assets cannot be straightforwardly allocated to functions, in contrast to workers. For example, a computer can be utilized in many tasks, and we have no information on its particular use. Therefore the task trade measures in this Element are based only on income data for labor. Another caveat is in the territorial interpretation of the task-trade measures. We track the value added by factor inputs in a specific geographical area, which does not necessarily coincide with the income earned by workers and entrepreneurs in that particular area. The rise of global production networks has led to large cross-border investment flows and tracking the ultimate recipients of this income is notoriously difficult (Lipsey, Reference Lipsey2010; Guvenen et al., Reference Guvenen, Mataloni, Rassier and Ruhl2017).Footnote 12 The trade in tasks measures is much less susceptible to this issue than the trade in value added measures as the former are based solely on labor income. Labor income is more likely to accrue to domestic workers than capital income is to local capital owners.

Fourth, task trade measures do not substitute for, but complement the traditional product trade statistics that are much more detailed. For example the official Harmonized System Nomenclature for imports and exports comprises about 5,000 commodity groups which are identified by a six-digit code. Task and product trade statistics can be used in conjunction to deepen our understanding. Thus, part of the differences in the task composition of textile exports as shown in Table 1 might be related to the detailed makeup of the textile product export basket, for example in the shares of low-end versus high-end market products. This granularity is currently not well represented in the task measures. More generally, industry categories in input-output tables are often too broad to capture the specific product-level dynamics critical to global value chains (Antràs and Chor, Reference Antrás and Chor2022). Greater product granularity is essential for policy analysis, for example, to assess chain vulnerability where input markets are highly concentrated and substitution is limited (Ossa, Reference Ossa2015). For instance, while automakers may source paint from various suppliers, these suppliers might all depend on a single pigment producer, creating a supply chain vulnerability (Wheatley and Ramsay, Reference Wheatley and Ramsay2011). Addressing these issues requires a combination of more data sources, an issue we return to in Section 7.

3 The Global Factory: Trends in the International Division of Tasks

3.1 Phases in the International Fragmentation of Production

Since the 1960s, the world economy has been characterized by a (then) “new” international division of labor where firms in advanced countries off-shore manual production activities to low-wage regions, while retaining more skilled headquarter activities at home. A theoretical underpinning of this unbundling process can be based on differences in factor endowments as provided in classic work on multinational production (e.g., Markusen, Reference Markusen2002). Baldwin (Reference Baldwin2016) emphasizes the acceleration and changing nature of the unbundling process from the mid-1980s onward. Geographically separating various production stages became more attractive as the North–South productivity-adjusted wage gap grew, and separation became less costly with declining communication, transport, and coordination costs. The interaction of lower trade and communication costs and the opening up of labor-abundant economies such as India and China played a decisive role in accelerating this process and the emergence of the “global factory” (Buckley, Reference Buckley2018).

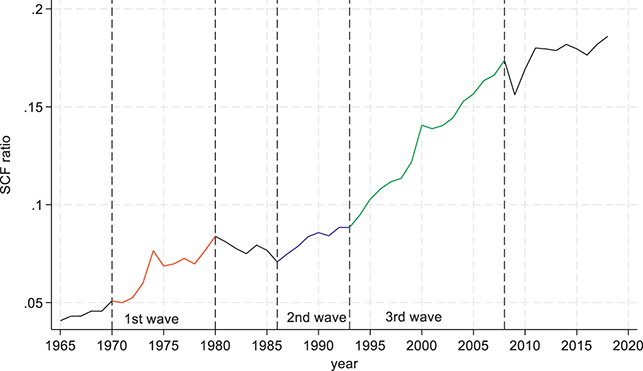

In Timmer et al. (Reference Timmer, Los, Stehrer and de Vries2021) we introduced a novel measure of cross-border supply chain fragmentation (SCF) to trace the speed and scale of the fragmentation process. The SCF ratio is based on a summation of all imports along a particular supply chain divided by the output value of the end-product. It takes account of imports by the country in which the product is finalized as well as imports by other countries in upstream stages of production. The SCF ratio is different from, and complements, other measures that capture different aspects of global value chain production and trade, as surveyed in Johnson (Reference Johnson2018). In particular it extends the measure of offshoring introduced by Feenstra and Hanson (Reference Feenstra and Hanson1999) and of vertical specialization introduced by Hummels, Ishii, and Yi (Reference Hummels, Ishii and Yi2001). Both these measures are insensitive to fragmentation in upstream stages of production that takes place outside the country that produces the end-product. Importantly, the SCF ratio is based on changes in volumes while other measures of fragmentation are based on changes in nominal values, confounding price, and volume effects. This is particularly important in periods when price differentials between raw materials and fabricated products arise, such as in the natural resource booms in the early 1970s and 2000s.

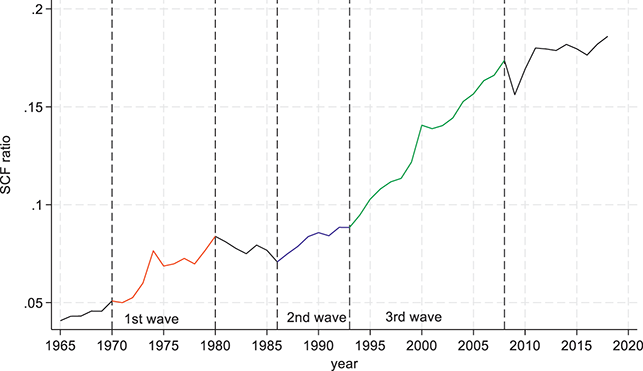

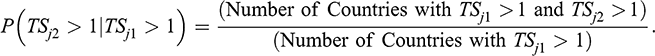

Figure 2 shows the aggregate SCF ratio for all goods and services in the world economy from 1965 onward. Various phases in the global fragmentation process can be distinguished. This process accelerated first in the 1960s. The SCF ratio appears to be more or less constant from the mid-1970s onward, before strongly accelerating again at the end of the 1980s. Yet, Pahl and Timmer (Reference Pahl and Timmer2019) show that the global trend hides substantial variation in the timing and strength not only across individual countries but also across industries. They showed that the first wave of vertical specialization in the world economy (1970–1980) involved almost all rich countries and various countries in East and South Asia as well as sub-Saharan Africa in their data set. In East Asia, Japanese industry started to unbundle, profiting from vast wage differences in the region (Fukao, Ishito, and Ito, Reference Fukao, Ishido and Ito2003). The second wave (1986–1993) was more widespread also involving countries in South and Central America. In North America the Maquiladora program boomed, integrating the US and Mexican border regions at a fast pace (Feenstra, Reference Feenstra1998). The third wave (1993–2008) revealed a concentration of the vertical specialization process as there was a sharp drop for countries in East and South Asia as well as in South and Central America. On the other hand, countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia became more involved through large scale cross-border investments from the European Union. Importantly, increasingly value is added outside the region to which the country-of-completion belongs, suggesting a transition from regional production systems to a truly “Factory World” during this period (Los et al., Reference Los, Timmer and de Vries2015). On the other hand, countries in the Middle East and North Africa experienced relatively few periods of vertical specialization at any time. All industries (except oil refining) participated in the unbundling process albeit at different speeds. The trend was particularly strong for production of durable goods like machinery and transport equipment as well as for chemical products. Exports of textiles became gradually more import intensive from the 1960s onward, whereas exports of machinery (including electronics) were below-average intensive in imports in 1970, but rapidly becoming more import-intensive over time in the 1980s.

Figure 2 Phases in the international unbundling of production

Note: Supply Chain Fragmentation (SCF) ratio at constant prices as defined in Timmer et al. (Reference Timmer, Los, Stehrer and de Vries2021). Annually chained Laspeyres volume index with 1995 as base. The ratio sums the volume of imports by all countries that participate in a particular supply chain, aggregated across all chains of goods and services in the world economy. Higher value signifies higher degree of international fragmentation of production.

The unbundling trend was halted in 2009, coinciding with the great global trade slowdown in the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2008 (see Figure 2). The drop in 2009 appeared to have been a short-run phenomenon. This is partly a reflection of sizeable inventory adjustments with unusually low purchases of intermediate inputs (Alessandria et al., Reference Alessandria, Kaboski and Midrigan2010; Bems et al., Reference Bems, Johnson and Yi2013). In 2010, the ratio was almost back at the 2008 level and leveled of afterward, resonating with a modest increase in import protection arising from temporary trade barriers as documented in Bown (Reference Bown2018). An important development is that the fragmentation process stalled for many goods production processes after 2010. This is strongly related to the increased ability of China, the major producer of these final goods, to substitute imports of sophisticated intermediates by domestically produced inputs. This substitution reflects the increasing ability of China to substitute its imports of intermediates by domestics production, with local firms spanning more and more stages of production (Kee and Tang Reference Kee and Tang2016; Chor et al., Reference Chor, Manova and Yu2021). Timmer et al. (Reference Timmer, Los, Stehrer and de Vries2021) find also that various final services “products” started to fragment in this period, albeit from a low level, such as construction services, logistics, and various professional services.

All in all, it can be concluded that the fragmentation process continued for three decades, but stalled in the Great Recession. The fallout of the financial and economic crises that engulfed the world in 2008 and 2009 hid the ending of the fragmentation process of goods production. With hindsight it can be concluded that the period from the end of the 1980s up to 2008 was a special period in global economic history.

Moving forward, digital infrastructure and automation technologies are likely to continue to reshape how firms structure what they do and where. Robotics and AI enable some tasks to be brought back in-house if machines outperform offshore labor, while cloud computing and digital platforms reduce coordination costs, allowing firms to outsource even complex business tasks. But these technological developments interact with other global trends, such as rising geopolitical tensions.

3.2 Specialization in the Global Factory

We delve deeper into the changing nature of the division of labor in the Global Factory since the mid-1990s. In particular, we are interested in what types of activities are carried out and in which countries. We aggregate the 455 tasks in this section to differentiate between knowledge-intensive (KI) and fabrication tasks. Fabrication tasks involve physical transformation processes, such as machine operation and assembly. KI tasks encompass a wide range of pre-fabrication (conceptualization, R&D, design, engineering) and post-fabrication tasks (marketing, branding, distribution). We measure Global Value Chain (GVC) income in these tasks by identifying the location and income of workers in the global factory of final manufacturing goods.Footnote 13 Note that workers in KI tasks are employed across manufacturing and services industries. The allocation of workers into KI and fabrication tasks is both exclusive (each worker belongs to one category) and exhaustive (all workers are categorized).Footnote 14 We focus on differences in specialization across countries and changes in GVC income, and also explore the importance of intangible income in the global factory.

For intuition, it is helpful to realize that this method is the macro-economic counterpart of the well-known micro case-study approach by Dedrick, Kraemer, and Linden (Reference Dedrick, Kraemer and Linden2010), who analyzed the income and job distribution in the production of the Apple iPod around 2006. The iPod’s production exemplified the unbundling of the production process, with components sourced globally and assembled in China. “Teardown” reports provided insights into the inputs and their market prices, allowing the authors to trace value captured by various participants like Broadcom, Toshiba, and Samsung. The iPod’s global production network involved over 41,000 jobs, with 98% of fabrication jobs in Asia and 65% of higher-paid engineering jobs in the United States. Consequently, nearly three-quarters of the labor income went to US workers, while Chinese workers earned less than 2.5% (Linden, Dedrick and Kraemer, Reference Linden, Dedrick and Kraemer2011). Similar studies were conducted for other electronics, such as mobile phones by Dedrick et al. (Reference Dedrick, Kraemer and Linden2010) and Ali-Yrkkö et al. (Reference Ali-Yrkkö, Rouvinen, Seppälä and Ylä-Anttila2011), with Kaplan and Kaplinsky (Reference Kaplan and Kaplinsky1999) contributing on the distribution of value in South African peaches. While product-level studies are insightful, they don’t capture the aggregate macro trends. This subsection offers therefore an overview of GVC income trends.

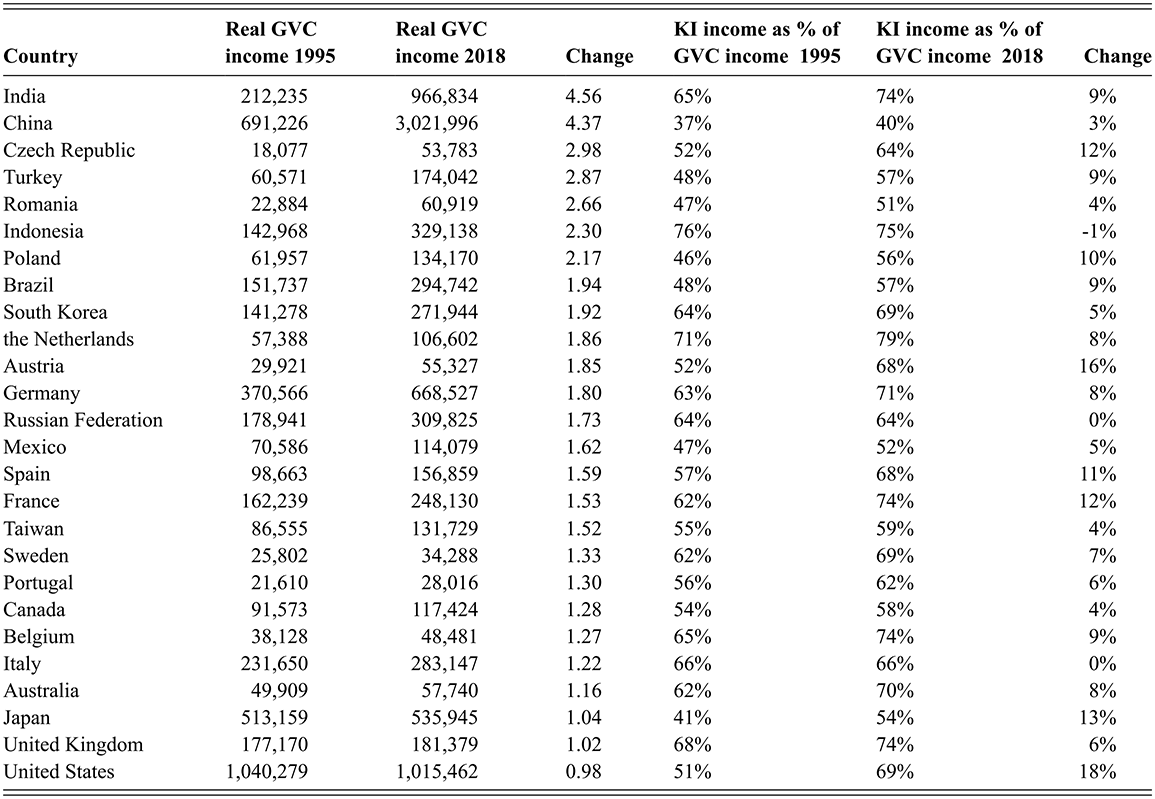

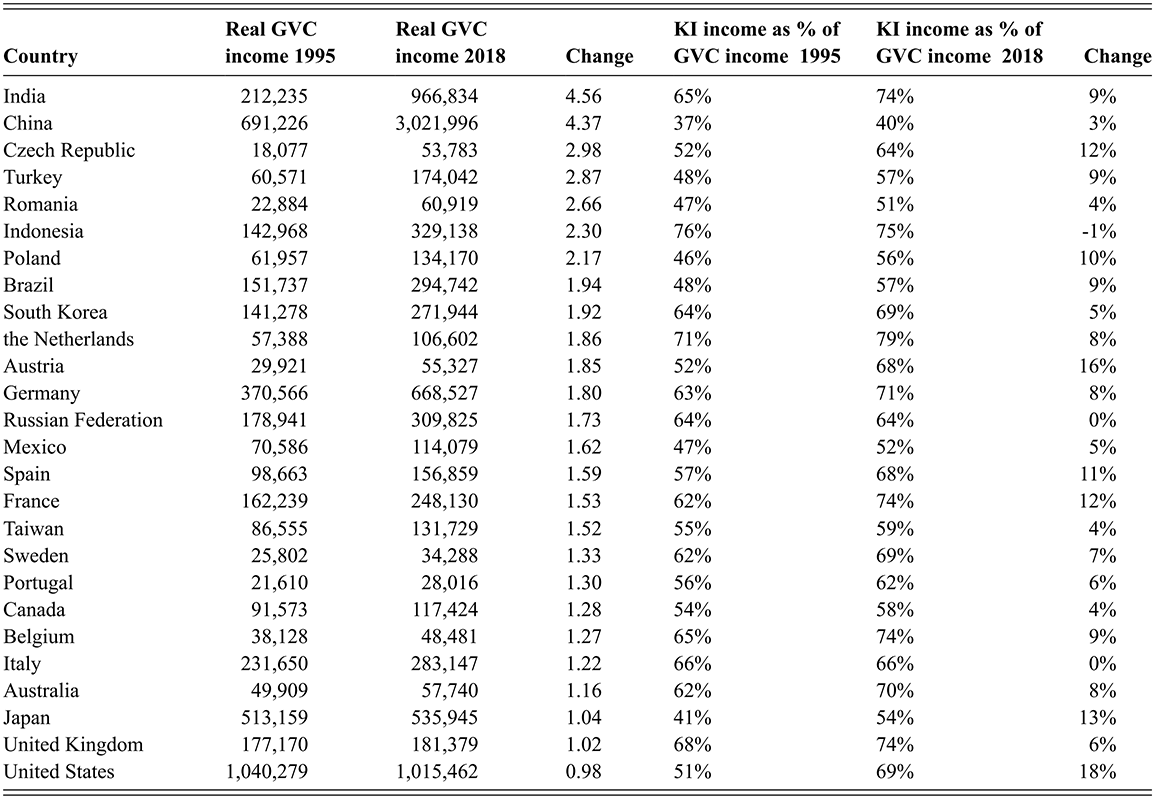

Table 2 highlights changes in real GVC incomes for major countries, ranked by growth. Overall earnings in the global factory increased rapidly driven by the rising global demand for manufacturing goods. This demand was fueled by the emergence of a new global middle-class boosting GVC incomes in emerging economies without significantly reducing incomes in advanced economies. China and India saw remarkable increases, quadrupling their incomes from 1995 to 2018. Brazil, Turkey, and smaller economies like the Czech Republic, Latvia, and Slovakia also more than doubled their incomes. Conversely, real GVC incomes hardly changed in major advanced economies such as Great Britain, Italy, the United States, and Japan. Germany and South Korea are interesting exceptions, as they saw increases of 80% and 92%, respectively.

Notes: GVC and KI (knowledge-intensive) incomes calculated as described in main text. Change in GVC income is measured as GVC income in 2018 divided by level in 1995. Change in KI specialization is measured as share in 2018 minus the share in 1995. All income values are expressed in US$ at constant 2011 PPPs.

Table 2Long description

The table has 6 columns: Country, Real GVC income 1995, Real GVC income 2018, Change, KI income as percentage of G V C income 1995, and K I income as percentage of GVC income 2018.

It reports the evolution of global value chain (G V C) income and the share of knowledge-intensive (K I) activities in total GVC income for 25 economies between 1995 and 2018. The Change in G V C income is measured as the 2018 value divided by the 1995 level, while the Change in K I specialization is measured as the difference in percentage points between 2018 and 1995. All income values are expressed in constant 2011 P P P U S dollars.

It reads as follows.

India: GVC income rose from 212,235 to 966,834 (a 4.56-fold increase); KI share rose from 65% to 74% (plus 9 percentage points).

China: from 691,226 to 3,021,996 (4.37×); KI share from 37% to 40% (plus 3).

Czech Republic: from 18,077 to 53,783 (2.98×); KI share from 52% to 64% (plus 12).

Turkey: from 60,571 to 174,042 (2.87×); KI share from 48% to 57% (plus 9).

Romania: from 22,884 to 60,919 (2.66×); KI share from 47% to 51% (plus 4).

Indonesia: from 142,968 to 329,138 (2.30×); KI share fell from 76% to 75% (minus 1).

Poland: from 61,957 to 134,170 (2.17×); KI share from 46% to 56% (plus 10).

Brazil: from 151,737 to 294,742 (1.94×); KI share from 48% to 57% (plus 9).

South Korea: from 141,278 to 271,944 (1.92×); KI share from 64% to 69% (plus 5).

The Netherlands: from 57,388 to 106,602 (1.86×); KI share from 71% to 79% (plus 8).

Austria: from 29,921 to 55,327 (1.85×); KI share from 52% to 68% (plus 16).

Germany: from 370,566 to 668,527 (1.80×); KI share from 63% to 71% (plus 8).

Russian Federation: from 178,941 to 309,825 (1.73×); KI share unchanged at 64%.

Mexico: from 70,586 to 114,079 (1.62×); KI share from 47% to 52% (plus 5).

Spain: from 98,663 to 156,859 (1.59×); KI share from 57% to 68% (plus 11).

France: from 162,239 to 248,130 (1.53×); KI share from 62% to 74% (plus 12).

Taiwan: from 86,555 to 131,729 (1.52×); KI share from 55% to 59% (plus 4).

Sweden: from 25,802 to 34,288 (1.33×); KI share from 62% to 69% (plus 7).

Portugal: from 21,610 to 28,016 (1.30×); KI share from 56% to 62% (plus 6).

Canada: from 91,573 to 117,424 (1.28×); KI share from 54% to 58% (plus 4).

Belgium: from 38,128 to 48,481 (1.27×); KI share from 65% to 74% (plus 9).

Italy: from 231,650 to 283,147 (1.22×); KI share steady at 66%.

Australia: from 49,909 to 57,740 (1.16×); KI share from 62% to 70% (plus 8).

Japan: from 513,159 to 535,945 (1.04×); KI share from 41% to 54% (plus 13).

United Kingdom: from 177,170 to 181,379 (1.02×); KI share from 68% to 74% (plus 6).

United States: from 1,040,279 to 1,015,462 (0.98×); KI share from 51% to 69% (plus 18).

Notes below the table read:

GVC and KI (knowledge-intensive) incomes are calculated as described in the main text. The Change in GVC income is measured as the ratio of 2018 to 1995 income. The Change in KI specialization is the difference between the KI shares in 2018 and 1995. All income values are expressed in 2011 PPP-adjusted US dollars. Source: Buckley et al. (2020), updated using estimates by Gentile and de Vries (2024).

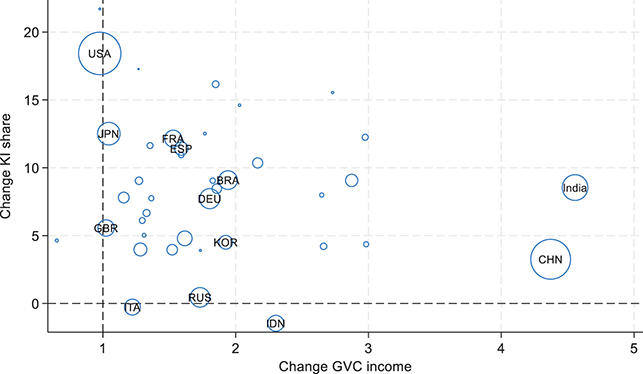

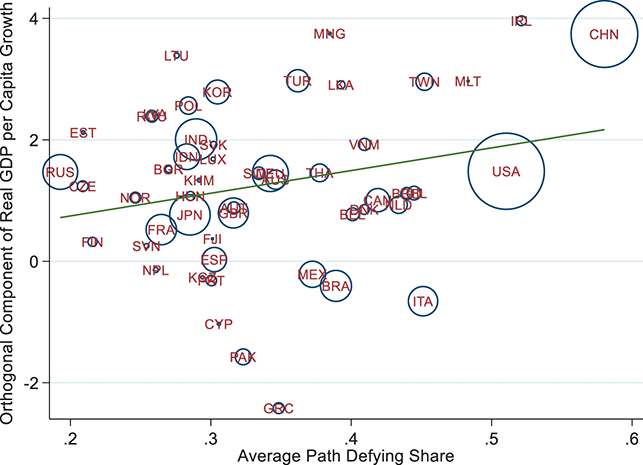

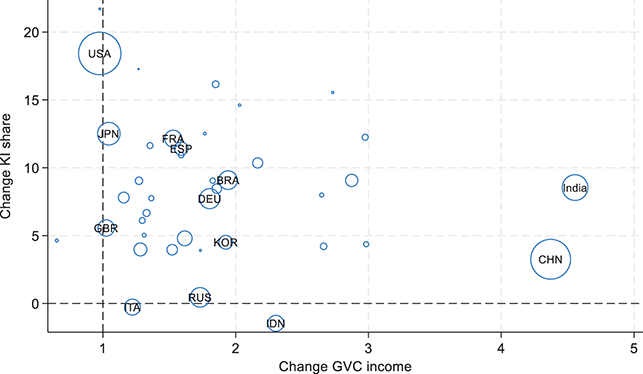

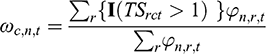

Countries varied not only in the growth of real GVC income but also in the type of tasks performed. The last columns of Table 2 show the share of knowledge-intensive tasks in overall GVC income, revealing a clear pattern of specialization from 1995 to 2018. Emerging economies are generally less specialized in KI tasks compared to advanced market economies. Figure 3 summarizes country-level data, plotting changes in GVC income on the horizontal axis (2018 GVC income divided by 1995 levels) and changes in specialization on the vertical axis (KI income share in 2018 minus the share in 1995). Countries on the south-east side of the graph experienced rapid GVC income growth, while those on the north-west side saw KI specialization in the Global Factory. While China’s KI tasks grew faster than fabrication, its overall share of fabrication remained high globally, creating substantial employment opportunities and lifting many out of poverty. India, already specialized in KI tasks in 1995, maintained this specialization, with 74% of GVC income from KI tasks compared to China’s 40%. Japan and the United States saw substantial increases in the share of KI tasks, with real income from KI tasks remaining stable while fabrication income declined. This contributed to labor market polarization and lower relative wages for less skilled workers in routine fabrication jobs (Autor and Handel, Reference Autor and Handel2013). France, Germany, and South Korea successfully capitalized on the expanding global consumer market, increasing tasks for both skilled workers in KI tasks and less skilled workers in fabrication. They were differently impacted by the “China shock” compared to Anglo-Saxon countries.

Figure 3 Change in GVC income and KI specialization, by country

Notes: Change in GVC income between 1995 and 2018 on horizontal axis. Change in KI share on vertical axis, multiplied by 100. Data taken from Table 2. Bubbles reflect country’s size of GDP (at PPP) in 2011.

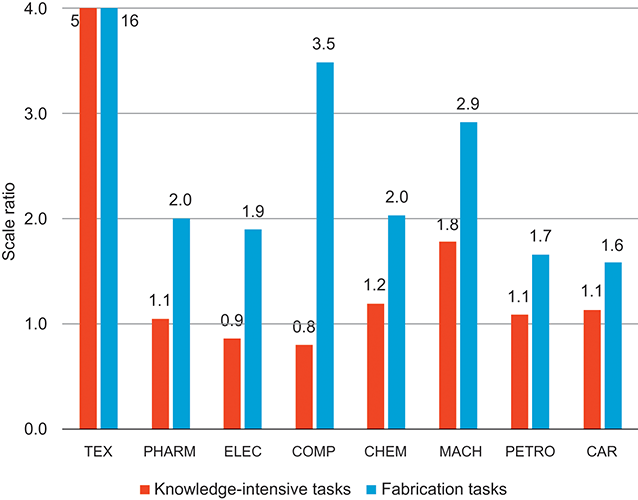

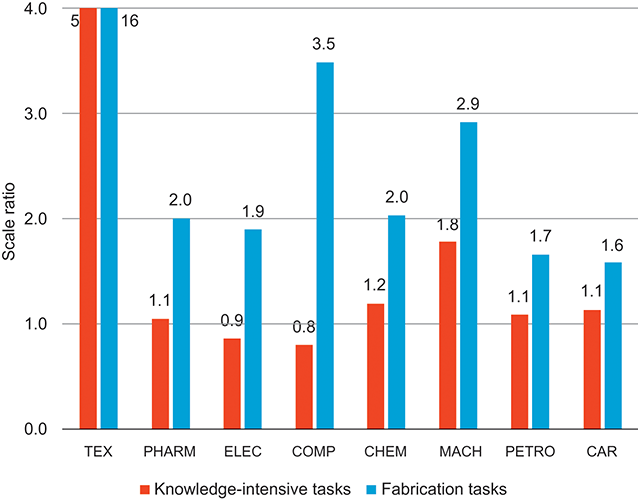

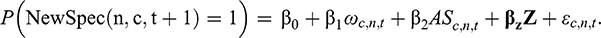

Specialization patterns in the global factory differ across products. For instance, KI tasks in apparel are easier to enter than in pharmaceuticals due in part to the strategic importance of patents in the latter. Generally, production processes reliant on intellectual property or advanced technology requiring tacit knowledge acquired through learning and experimenting show distinct specialization patterns. Figure 4 shows the scale of workers in fabrication and KI tasks in emerging economies (EE) relative to advanced economies (AE) for separate product groups in 2018.Footnote 15 Products are ranked by their relative scale ratio for workers performing fabrication tasks. The scale gap in KI tasks is much smaller than in fabrication tasks. Clearly, there is notable variation across products. For example, the scale of tasks in emerging economies for textiles is a major outlier, with the number of workers performing fabrication tasks per capita in EEs more than twelve times that in AEs. For KI tasks, it is almost four times the level in AEs, indicating there are also many workers in EEs involved in pre- and post-fabrication tasks. In pharmaceuticals, a substantial portion of fabrication tasks is in EEs (double the AE level), but this is much less so for KI tasks.

Figure 4 Scale of tasks in emerging economies relative to advanced economies, by product group, 2018

Notes: Scale (GVC workers per capita) of knowledge intensive and fabrication tasks in emerging economies relative to advanced economies. TEX: Textiles, wearing apparel and leather products; PHARM: pharmaceutical products; ELEC: electrical equipment; COMP: computer, electronic and optical products; CHEM: chemical products; MACH: Manufacture of machinery and equipment; PETRO: refined petroleum products; CAR: motor vehicles and trailer.

The offshoring of tasks to emerging economies contributed to a decline in the labor share in incomes and a rise in the capital share in both advanced and emerging economies (Timmer et al., Reference Timmer, Erumban, Los, Stehrer and de Vries2014; Karabarbounis and Neiman, Reference Karabarbounis and Neiman2014). Multinational firms developed firm-specific coordination systems, taking advantage of offshoring labor-intensive tasks to low-wage locations, leading to a decline in labor income in GVCs due to wage cost savings. The growth in global purchasing power, particularly in China, benefited multinational firms that leveraged existing intangibles like brand names and distribution systems at low marginal costs. This relates to how lead firms in GVCs have increasingly concentrated on developing and managing so-called “intangible assets.” These intangibles, which are highly appropriable, non-location bound, scalable at low marginal cost, and susceptible to opaque valuations, have become crucial for generating profits and temporary market power of multinational enterprises (Teece, Reference Teece2018; Durand and Milberg, Reference Durand and Milberg2020). Clearly, such intangible assets contribute to productivity by enhancing a firm’s ability to innovate, scale, and differentiate itself in the market. For example, patents can protect innovative ideas, allowing firms to recoup R&D investments, while trademarks and branding (including goodwill) help firms attract and retain customers more effectively. These intangible investments often exhibit spillover effects, where benefits extend beyond the firm, and scalability, meaning that once created, they can be used repeatedly at low marginal cost, both of which amplify their contribution to productivity (Haskel and Westlake, Reference Haskel and Westlake2017). Indeed, recent studies highlight the rise of “superstar firms” in the United States, which leverage scalable information technologies and significant investments in intangible assets to gain productivity advantages and increase market shares (Crouzet and Eberly, Reference Crouzet and Eberly2019; Autor et al., Reference Autor, Katz, Patterson and Van Reenen2020).

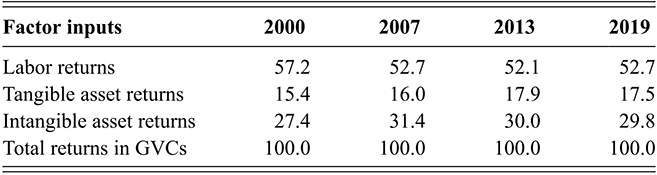

But just how important are intangibles in the division of gains in the Global Factory? Given their attributes, the returns to intangible assets are difficult to separate from returns to more conventional tangible assets such as plant, machinery, hardware, and buildings. When produced and used in-house, they are often not fully reported in firms’ balance sheets or national accounts statistics (Corrado et al., Reference Corrado, Hulten, Sichel, Corrado, Haltiwanger and Sichel2005). Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Los, Timmer, Corrado, Haskel, Miranda and Sichel2021) propose the “yeast approach” to measure intangible income indirectly based on residual income. This method aligns with the role of intangible assets in value creation and appropriation. Intangible capital acts as the “yeast” that generates value from labor and tangible assets. The returns to this intangible yeast are calculated residually by subtracting the costs of labor (L at wage w) and tangible assets (K at user cost rate r) from the value-added (Y), i.e., Y – rK – wL. Data on value-added, tangible asset stocks, and labor costs from national accounts statistics allow for estimates of intangible asset returns.Footnote 16 Results are given in Table 3, highlighting broad trends in returns within the global factory of manufactured goods. It confirms prior research that found a decline in the labor share of worldwide returns in GVCs. Most notably, it shows that returns from intangible assets (intellectual property, R&D, and firm-specific knowledge) far exceed those from tangible assets, by a factor of 1.7 in 2019, making up almost a third of the total market value of final manufactured goods. The results also show that the early 2000s was a unique period in the global economy where supranormal returns were temporarily captured, largely due to firm-specific intangible assets that went unrecorded in national statistics. The share of intangibles went up from 27% to 31% of total GVC income, gradually declining again to 30% in 2019, but not returning to the 2000 level.

In conclusion, the structure of the Global Factory has undergone a fundamental transformation, affecting both the distribution of tasks among countries and the allocation of returns to various factors of production. Recently, globalization has changed. Recent supply chain disruptions have been primarily driven by a shift in the nature of economic shocks, from isolated incidents to system-wide events, rather than by changes in the supply chains themselves (Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin2023). Looking ahead, the future of globalization is likely to be shaped more by services, particularly intermediate services, than by goods. This shift is evident in the diverging growth patterns of services and goods trade. Digital technology has enabled increased trade in intermediate services, and high-income countries generally maintain few or no barriers to such exports, facilitating this trend (Baldwin, Reference Baldwin2022).

| Factor inputs | 2000 | 2007 | 2013 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labor returns | 57.2 | 52.7 | 52.1 | 52.7 |

| Tangible asset returns | 15.4 | 16.0 | 17.9 | 17.5 |

| Intangible asset returns | 27.4 | 31.4 | 30.0 | 29.8 |

| Total returns in GVCs | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Notes: The shares of each factor input are expressed as percentages of the total GVC returns. Labor returns include all costs of employing labor, including self-employed income. Tangible asset returns are calculated as gross returns to tangible assets based on a 4% real (net) rate of return and industry-specific depreciation rates. Intangible asset returns are calculated as a residual (gross value added minus labor and tangible asset returns). The total returns include returns earned in the upstream, production and downstream GVC stages of the production of all manufactured goods in the world economy.

4 Trade in Tasks Development: Stylized Facts

Whereas the previous section provides aggregated trends, this section provides greater detail by contributing to the long-standing tradition of analyzing patterns of structural transformation as incomes rise (Chenery et al., Reference Chenery, Robinson and Syrquin1986; Syrquin, Reference Syrquin, Chenery and Srinivasan1988; Herrendorf et al., Reference Herrendorf, Rogerson and Valentinyi2014). A traditional concern in this literature is the lack of export development, which appears to be linked with slower structural change and productivity growth. We study the domestic value-added content of exports and revisit the relationship between export development and income growth from a task perspective.

Section 4.1 describes the average patterns in task shares across different levels of economic development. We document that the export basket of countries changes not only across industries (e.g., from textiles to electronics) but also within them (e.g., from craft workers to engineers). We also provide evidence that participation in GVCs relates to enhanced productivity but limited employment expansion. Section 4.2 employs a shift-share method to examine how countries initially specialize along the extensive margin (shifting exports of value added across industries) and later along the intensive margin (shifting exports across occupations within industries).

4.1 Trade in Tasks and Levels of Economic Development

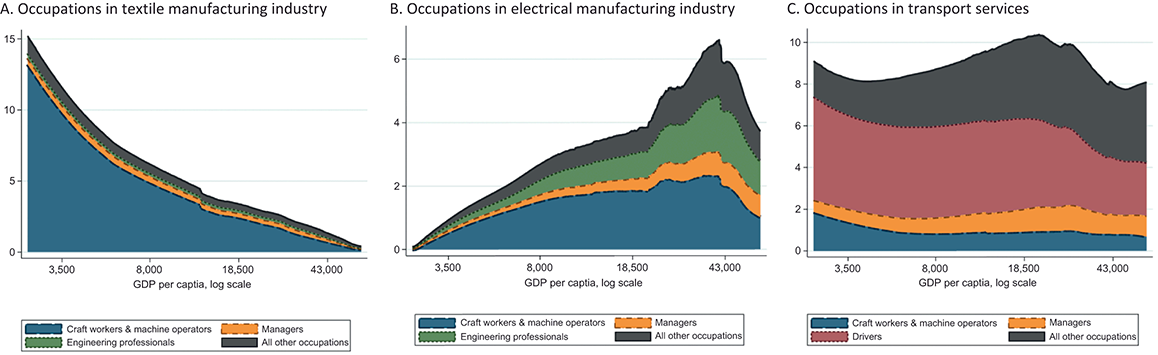

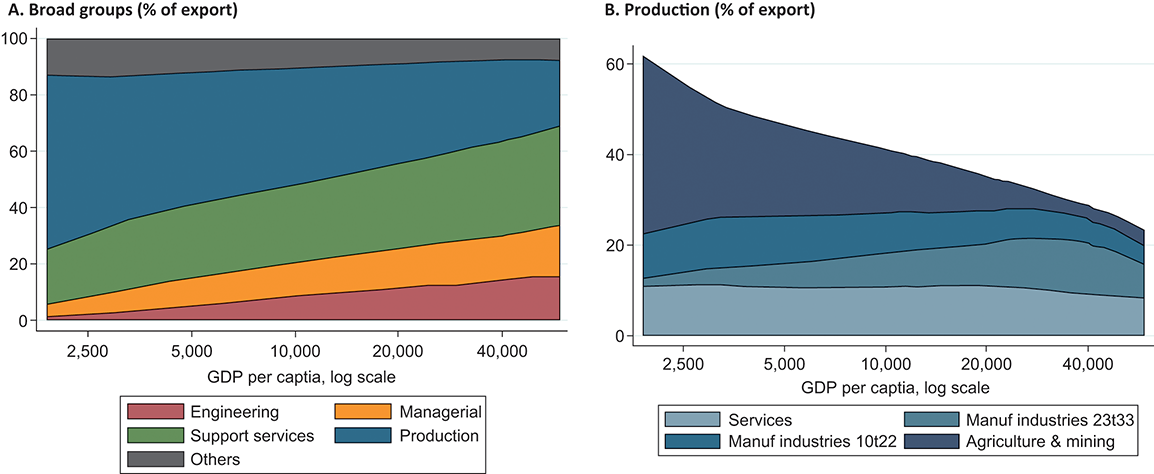

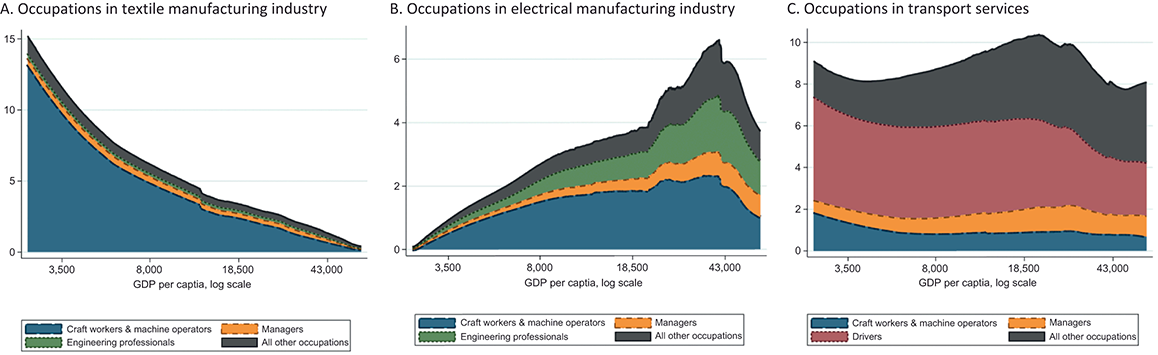

How do exports evolve in terms of tasks as countries grow richer? Figure 5 illustrates the development of export shares of various industry-occupation pairs as GDP per capita increases. These shares are estimated using a non-parametric smoother on data from fifty-two countries over a span of twenty years.Footnote 17

Notes: percentage shares of tasks in overall domestic value added exports is plotted against GDP per capita (in 2017 US$, log scale) using a non-parametric LOWESS smoother with bandwidth 0.5 on data for 52 countries and the period 2000–2018. Panel A refers to textiles and textile products manufacturing (ISIC revision 3 codes 17t18), panel B to electrical and optical equipment manufacturing (30t33), and panel C to transport services (60t63). “All other occupations” refers to total of occupations not separately shown.

Figure 5 Task shares in exports over levels of economic development, selected industries

Traditionally, export patterns are described as progressing from agricultural to manufacturing products. Within manufacturing, exports shift from light industries that rely on unskilled labor to heavy industries that depend on physical and human capital (Syrquin, Reference Syrquin, Chenery and Srinivasan1988). Figure 5 confirms this progression. The share of the textile industry in total value-added exports is generally high during the early phases of development but steadily declines as countries grow richer (Panel A). Conversely, the export share of tasks in the electrical machinery industry steadily increases, peaking at a GDP per capita of around $40,000 before declining (Panel B).

However, a task perspective reveals that the export basket of countries changes not only across industries but also within them. For instance, in the early stages of development, exports from the electrical industry are dominated by craft workers and machine operators. As countries develop, engineers play a major role in these exports (Panel B). Additionally, the services industry makes substantial contributions to value-added exports, as noted by Johnson and Noguera (Reference Johnson and Noguera2017). For example, tasks in the transport services industry constitute between 8% and 10% of total export value at all development levels (Panel C). Initially, these tasks are mostly performed by drivers and mobile plant operators. Over time, the share of tasks performed by clerical support workers and sales workers increases. These results show that the composition of exports evolves not only across different industries but also within industries as countries develop.

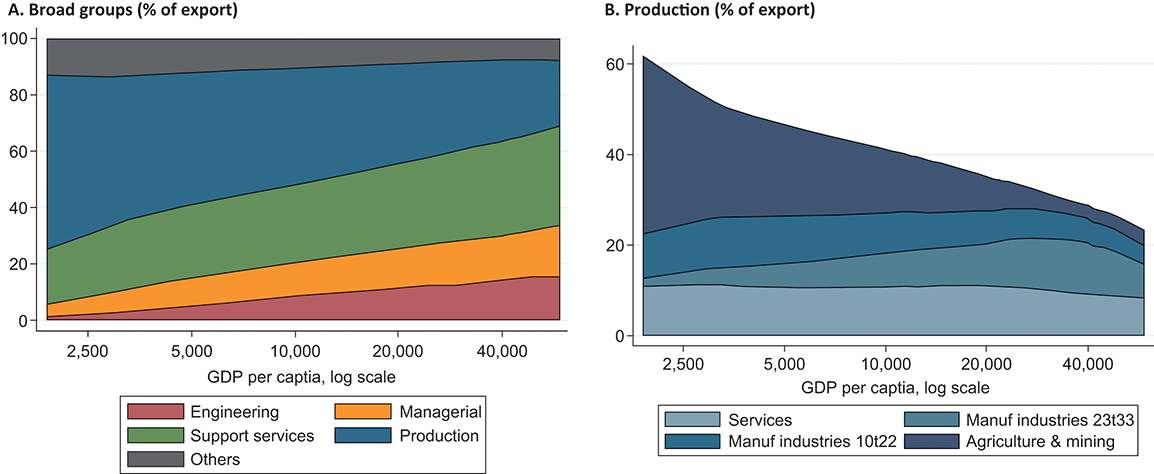

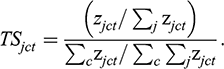

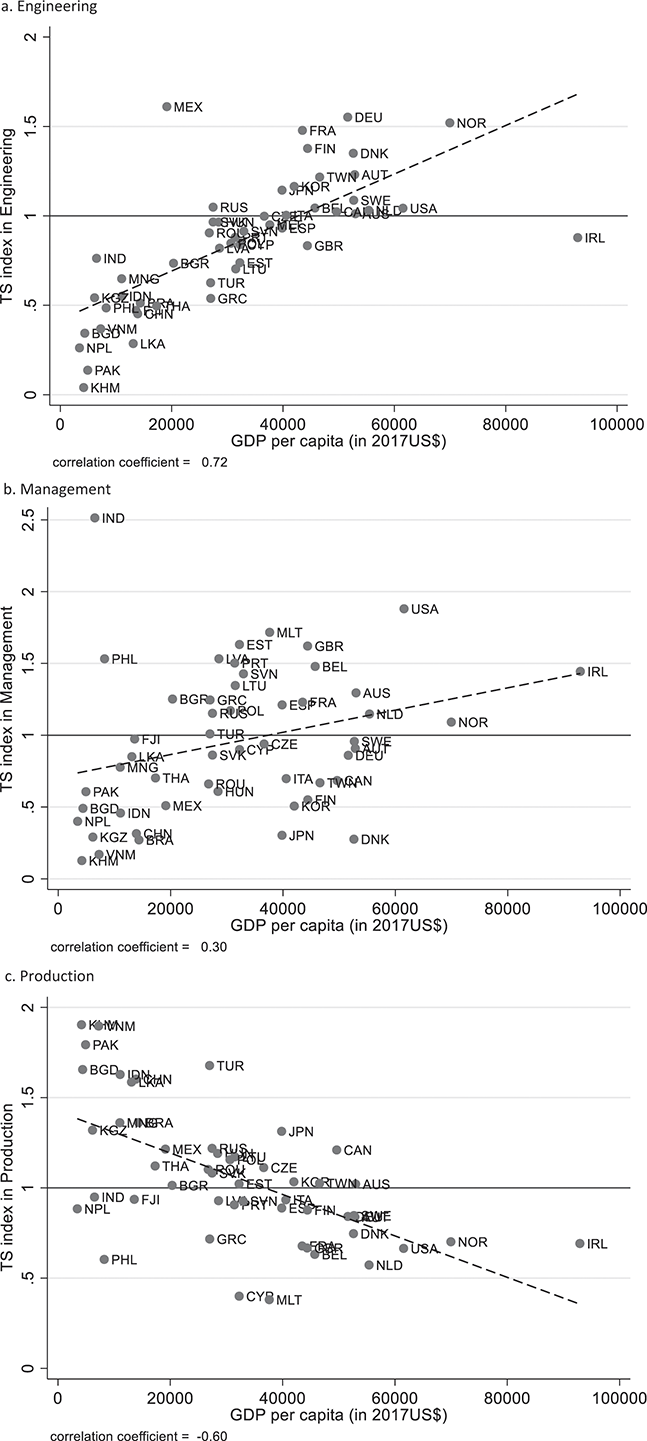

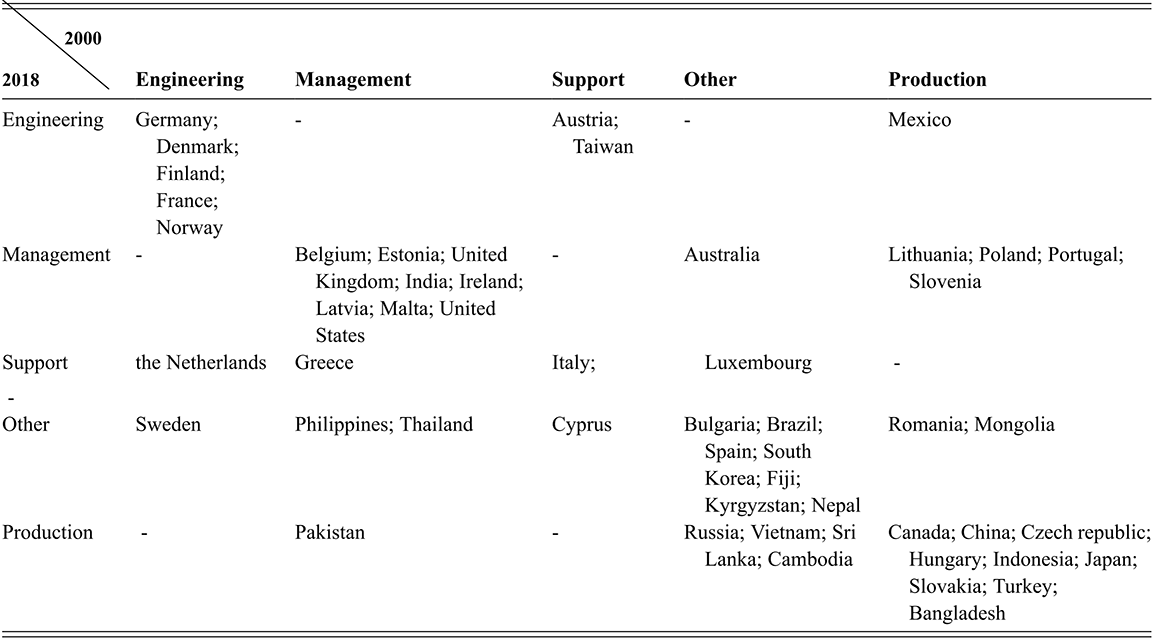

Figure 6 illustrates the cross-country evolution of trade in tasks relative to GDP per capita. To simplify the analysis, panel A aggregates the 455 tasks into five broad groups: engineering, managerial, production, support, and other across all industries. A common distinction in global production is between fabrication and headquarter activities, generally aligned with unskilled (blue-collar) and skilled (white-collar) labor, which we discussed in the previous section. Building on this, we now classify occupations into five functional task categories: engineering, managerial, production, support, and other. These categories reflect how multinational firms typically structure their operations around core business functions to exploit internal economies of scale (Porter, Reference Porter1985).

Figure 6 Task shares in exports over levels of economic development, cross-country

Notes: Based on percentage shares of tasks in overall domestic value added exports for 59 countries and 20 years. Shares are plotted against GDP per capita (in 2017 US$, log scale) using a non-parametric LOWESS smoother with bandwidth 0.5. Broad groups are aggregated up and summed over all industries in panel A. Support services include: other professionals, clerical support workers, and sales workers; Production includes: craft workers and machine operators, agricultural workers, and drivers; Others include: legislators, health professionals, teachers, personal support workers; and other workers. Further breakdown of production in panel B by industry in which production task takes place: agriculture and mining refer to ISIC rev. 4 codes A and B, manufacturing industries to code C and services industries to codes D to U.

The data indicate that at lower levels of economic development, production constitutes a large portion of export income. Specifically, the production share decreases from over 50% of total exports at GDP per capita levels below $5,000 to approximately 30% at levels above $40,000. As countries become wealthier, engineering, managerial, and support increasingly dominate the labor income derived from exports.Footnote 18 Panel B offers a more detailed look at production across four broad industry groups. It reveals a shift in income from production within agriculture, mining, and “light” manufacturing industries (such as food and textiles) toward production in “heavy” manufacturing industries (including electrical and transport equipment).

Changes in task income shares likely relate to productivity growth. This is because tasks are likely to differ in their returns to factor inputs, for example, where the average wage of engineers is higher than assemblers. Tasks are also likely to differ in their potential for productivity growth and in the generation of knowledge and other spillovers. However, whether changes in task income shares also relate to employment growth is a different matter. As Rodrik (Reference Rodrik2018) argues, the specialized nature of GVC participation, typically focused on a narrow set of tasks within global production networks, limits the development of domestic linkages. This means that local firms are often excluded from upstream or downstream activities, reducing opportunities for job creation, technology transfer, and productivity spillovers. As a result, GVC integration may raise export volumes and foreign investment without delivering the widespread employment benefits or structural transformation that characterized industrialization in earlier periods of development. Compounding the issue, Rodrik (Reference Rodrik2018) contends that technological advancements within global value chains favor skilled labor, resulting in increased productivity but failing to adequately absorb unskilled workers.

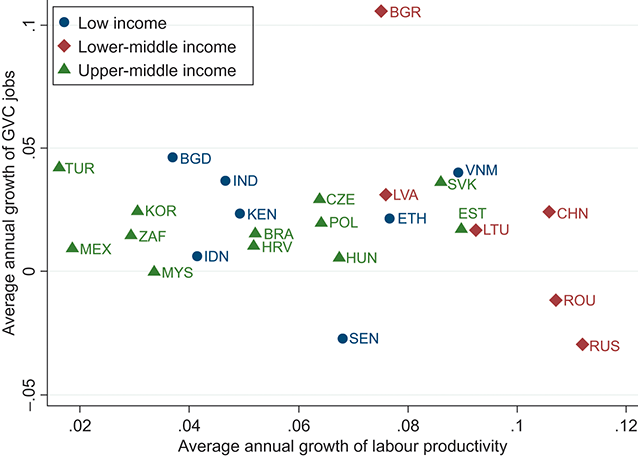

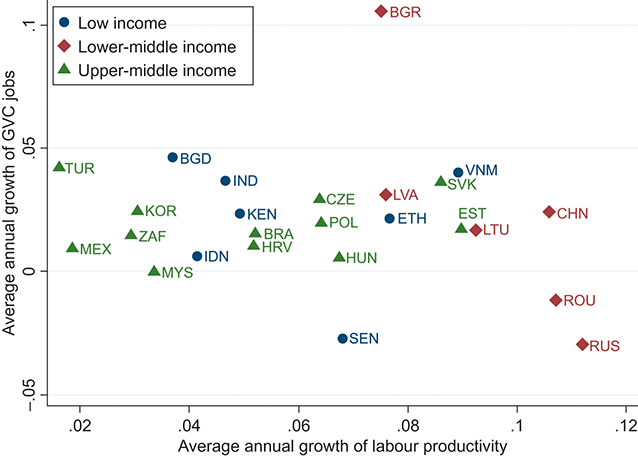

Suggestive evidence for this is provided in Figure 7. The figure shows the change in the number of workers involved in global value chains plotted against the change in labor productivity. Some countries, such as China and Vietnam, demonstrate a combination of job creation and rapid labor productivity growth. In contrast, other countries like Ethiopia, Romania, Russia, and Senegal experience high productivity growth but relatively modest job growth. Overall, there is no clear positive relation between job creation and productivity (value added per worker) in global value chains. This aligns with other recent studies. Country-level regressions indicate that participation in global value chains positively relates to labor productivity (Constantinescu et al., Reference Constantinescu, Mattoo and Ruta2019), but does not necessarily lead to employment growth (Pahl and Timmer Reference Pahl and Timmer2020; Winkler et al., Reference Winkler, Kruse, Luna and Maliszewska2023). Firm-level data from Diao et al. (Reference Diao, Ellis, McMillan and Rodrik2021) reveal that larger firms in Tanzania and Ethiopia, which have recently started exporting, show enhanced productivity but limited employment expansion.

Figure 7 Productivity and employment growth within global value chains

Notes: Average annual growth rates of workers and labor productivity (measured as deflated value added per worker) in GVCs from 2000 to 2014 are presented. The results cover 7 low-income countries (Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Indonesia, India, Kenya, Senegal, and Vietnam), 6 lower-middle-income countries (Bulgaria, China, Lithuania, Latvia, Romania, and Russia), and 12 upper-middle-income countries (Brazil, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, South Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Poland, Slovakia, South Africa, and Turkey).

The next section investigates the extent to which countries follow a common development path in export specialization. First, we further explore how the composition of exports evolves both across industries and within industries as countries develop.

4.2 Trade in Tasks: Distinguishing Changes along the Intensive and Extensive Margin

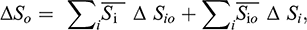

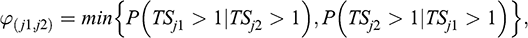

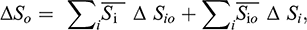

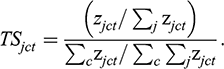

As discussed in the previous section, changes in the tasks composition of exports can be driven by shifts along the extensive margin – shifting exports of value added across industries – and shifts along the intensive margin – shifting export income across occupations within industries. To quantify the relative importance of these shifts, we conduct a standard shift-share decomposition. The overall change in

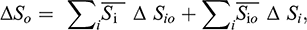

![]() , the share of occupation o in a country’s overall export income during a particular period, can be expressed as follows:

, the share of occupation o in a country’s overall export income during a particular period, can be expressed as follows:

(1)

(1)

where

![]() represents the share of workers with occupation o in exports of industry i, and

represents the share of workers with occupation o in exports of industry i, and

![]() denotes the share of industry i in the country’s overall export income. Δ indicates the change over the period and a bar over a variable denotes the period average of that variable.

denotes the share of industry i in the country’s overall export income. Δ indicates the change over the period and a bar over a variable denotes the period average of that variable.

A change in

![]() can result from two main factors. Firstly, shifts along the intensive margin occur when there are changes in the distribution of value-added exports across different occupations within industries. This is represented by the first term on the right-hand side of the equation. Secondly, changes along the extensive margin occur when there are shifts in the distribution of value-added exports between industries. This is captured by the second term in the equation.

can result from two main factors. Firstly, shifts along the intensive margin occur when there are changes in the distribution of value-added exports across different occupations within industries. This is represented by the first term on the right-hand side of the equation. Secondly, changes along the extensive margin occur when there are shifts in the distribution of value-added exports between industries. This is captured by the second term in the equation.

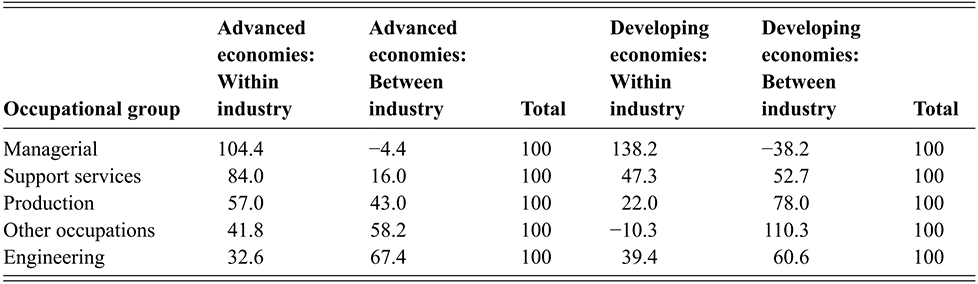

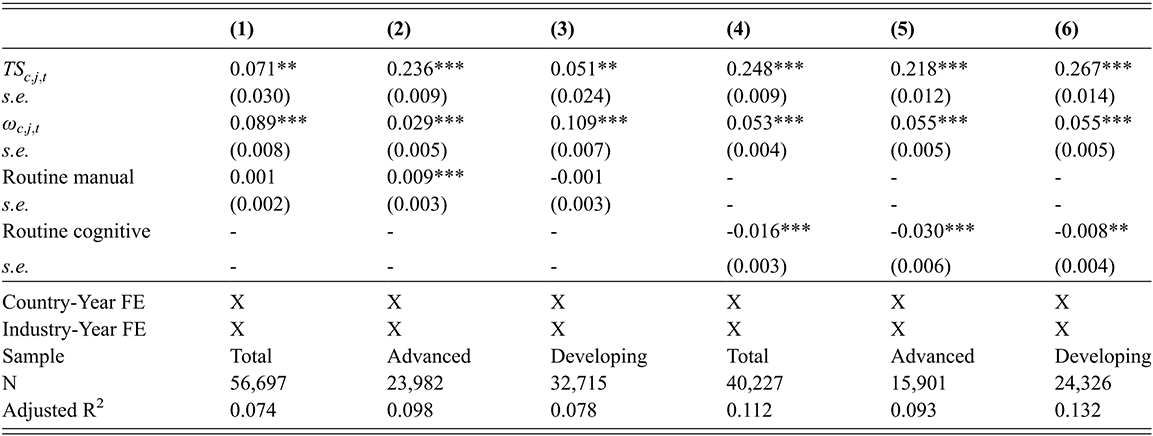

Table 4 presents the decomposition for each of the five broad occupational groups between 2000 and 2018. The economies are categorized into advanced and developing groups based on their income levels in 2000 (see Appendix B for the countries in each group). The results are reported as simple averages across all economies within each group.

| Occupational group | Advanced economies: Within industry | Advanced economies: Between industry | Total | Developing economies: Within industry | Developing economies: Between industry | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Managerial | 104.4 | −4.4 | 100 | 138.2 | −38.2 | 100 |

| Support services | 84.0 | 16.0 | 100 | 47.3 | 52.7 | 100 |

| Production | 57.0 | 43.0 | 100 | 22.0 | 78.0 | 100 |

| Other occupations | 41.8 | 58.2 | 100 | −10.3 | 110.3 | 100 |

| Engineering | 32.6 | 67.4 | 100 | 39.4 | 60.6 | 100 |

Notes: The change in the share of a broad occupation group in export incomes is decomposed into between-industry and within-industry effects according to equation (1) for five broad aggregations of occupational groupings. Results are standardized by the total change within each broad aggregation and ordered by the within-industry component for advanced economies. Simple country averages are given for advanced and developing economies.

In developing economies, the decline in the export of production tasks is primarily attributed to shifts along the extensive margin, as workers transition toward less production-intensive industries. As countries progress economically, shifts along the intensive margin become increasingly dominant, aligning with the production outsourcing hypothesis, also referred to as the “servicification” of goods industries, as highlighted by Duernecker and Herrendorf (Reference Duernecker and Herrendorf2022). Engineering continues to expand its export share across all development levels, primarily driven by shifts along the extensive margin. Conversely, the increase in the export share of managerial tasks occurs exclusively through increasing shares within industries, observed in both developing and advanced economies.

Our exploratory findings illustrate how the task composition of exports evolves along both the industry (extensive) and occupation (intensive) dimensions as countries advance. Initially, countries specialize along the extensive margin, shifting exports of value-added across industries. As GDP per capita continues to rise, specialization intensifies along the intensive margin, with exports of value-added shifting across occupations within industries. While extensive diversification is captured in analyses using the traditional product or industry perspective, intensive diversification is not. This sheds light on the nuanced dynamics of export composition changes as countries progress in terms of GDP per capita.Footnote 19

5 The Dynamics of Task Specialization

The traditional approach to measure specialization in trade is based on the product composition of countries’ gross export flows. A central argument in this Element is that this product perspective needs to be enriched with information on what workers do, due to large-scale offshoring trends with workers across countries carrying out different tasks in global value chains.

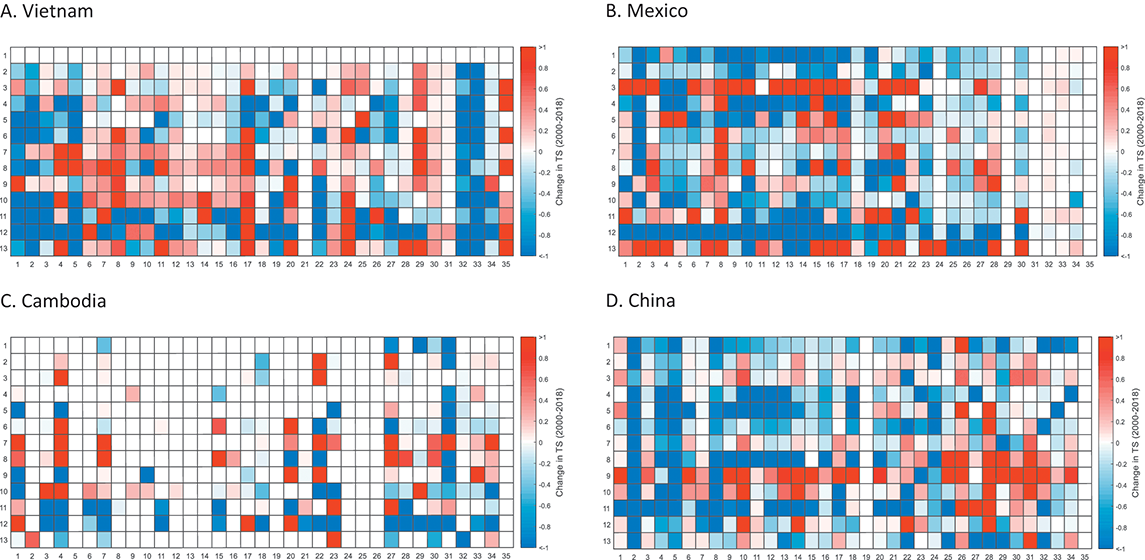

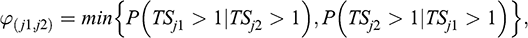

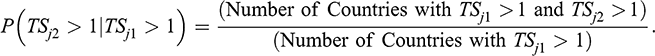

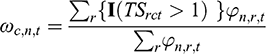

This section provides new insights by analyzing the dynamics of trade specialization through the lens of tasks. Section 5.1 describes the methodology to identify what tasks countries are relatively best at doing. It also provides an illustration using the exports of electronics. Section 5.2 examines the cross-country relation between task specialization and levels of development. Section 5.3 studies the dynamics of task specialization within countries over time. Section 5.4 explores the determinants of task specialization. The final part of this section, Section 5.5, explores the role of automation in task specialization.

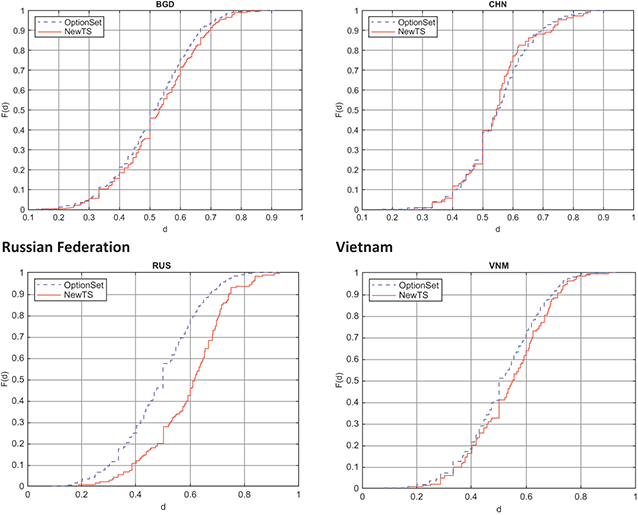

5.1 Comparative Advantage in Tasks: Method and Illustration

A common method to determine if a country is specialized in a particular product is to examine whether the product’s share in the country’s overall exports is higher than the corresponding share in the exports of other countries (Balassa, Reference Balassa1965). For example, when a specific product accounts for a larger share of a country’s exports compared to others, it suggests that the country has a comparative advantage in producing and exporting that good.