Ancestors of the Huron-Wendat occupied southern Ontario, Canada, for millennia. The Huron-Wendat numbered about 30,000 people at the time of European contact, and they were maize agriculturalists living in palisaded longhouse villages (Warrick Reference Warrick2008). Seventeenth-century disease epidemics and warfare with the Haudenosaunee (Five Nations Iroquois) forced the Huron-Wendat to leave Ontario and join other Indigenous groups in northeastern North America, with several hundred resettling in Quebec in 1650, where their descendants live today as la Nation huronne-wendat. Because Huron-Wendat village and burial sites are relatively numerous, are highly visible in ploughed fields, and contain large quantities of artifacts, they have attracted archaeological activity in Ontario for over 170 years (Williamson Reference Williamson2014). Past and ongoing land disturbance and invasive archaeological excavation have effectively erased dozens of Huron-Wendat village sites from the Ontario landscape, hindering Huron-Wendat duty to care for their ancestors (Warrick Reference Warrick2018). Nonetheless, over the last 20 years, in addition to large-scale repatriation and reburial of ancestral remains and associated buried belongings (artifacts), the Huron-Wendat have asserted their rights to archaeological heritage in Ontario and requested that archaeologists make every effort to avoid any further excavation of ancestral sites (Conseil de la Nation huronne-wendat 2015). This request, however, poses a serious challenge to most Ontario archaeologists.

In Ontario, archaeological sites are protected under the Ontario Heritage Act (R.S.O. 1990). All archaeological activity in the province is licenced and regulated by the Ontario Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries (OMHSTCI). Provincial legislation protects archaeological sites from private- and public-sector land development, creating a healthy cultural resource management (CRM), or archaeological consulting, industry (Williamson Reference Williamson2010). In fact, almost 99% of all archaeological activity in Ontario is carried out on development lands by CRM archaeologists (Warrick Reference Warrick2017). Although federal and provincial legislation require developers to engage with Indigenous nations, such as the Huron-Wendat, Indigenous nations do not have veto power to stop development and the archaeological excavation of ancestral sites. Despite recommendations issued by the OMHSTCI to avoid large village sites during land development, in most cases, salvage excavation of Huron-Wendat village sites continues to be standard operating procedure in CRM contexts (Warrick Reference Warrick2018; Williamson Reference Williamson2010). Even the initial investigation of a discovered village site requires an archaeologist to conduct invasive test excavation. Archaeologists have their hands tied by archaeological regulations even if they wish to honor the Huron-Wendat request for noninvasive archaeology. In fact, Ontario archaeology has reached a tipping point between private-sector demands and government legislation encouraging site excavation on the one hand, and on the other, the inherent rights of and ethical responsibilities to Indigenous peoples to avoid site excavation. In this article, we explore the ways in which archaeologists can employ geophysical and geochemical surveys—in concert with very limited excavations—as a way to alleviate the tension between the demands that heritage laws and land development put on our discipline for site excavation and the demands of Indigenous rights and responsibilities to do as little excavation as possible.

We decided that the best way to discuss this tension is to feature our own research as a case study. Collaborating closely with the Huron-Wendat of Wendake, Quebec, and honoring their cultural responsibilities, Warrick and Glencross (non-Indigenous archaeologists) with Lesage (Huron-Wendat) have employed minimally invasive remote sensing methods of investigation at Ahatsistari, a forested early seventeenth-century Huron-Wendat village site in Simcoe County, Ontario. Remote sensing methods (e.g., magnetic susceptibility survey, high-resolution soil chemistry sampling, and metal detector survey) have revealed village limits and the possible location and orientation of longhouses. This has provided essential information in support of the Huron-Wendat imperative to find, assess, and preserve as many of their archaeological sites as possible so as to protect the ancestors, learn from them, and preserve ancestral sites and related landscapes for future generations.

HURON-WENDAT CONCERNS ABOUT ARCHAEOLOGY

The Huron-Wendat, like other Indigenous peoples in eastern Canada, want to take control of their archaeological heritage (Nionwentsïo Office, Nation huronne-wendat 2020). In a 2020 announcement of a new Huron-Wendat partnership with Archaeological Services Inc. (ASI), one of the oldest and largest archaeological consulting firms in Ontario, Grand Chief Konrad Sioui states,

The Huron-Wendat Nation places the preservation, protection, and promotion of its patrimonial, ancestral, and cultural rights and interests at the heart of its activities in South Wendake (central Southern Ontario). The occupation and lives of many generations of Huron-Wendat ancestors have left an invaluable wealth that we must protect and develop, and the Nation is increasing its capacity to fulfill a duty that belongs to it through this partnership and the people it involves [Archaeological Services Inc. (ASI) 2020].

This new partnership is the culmination of over two decades of political engagement and consultation agreements with governments, developers, museum curators, and archaeologists in asserting their rights to their archaeological past through (1) intensification of historical land research in collaboration with experts; (2) repatriation and reburial of the bones of their ancestors in accordance with their funerary rites (Kapches Reference Kapches2010; Pfeiffer and Lesage Reference Pfeiffer and Lesage2014); (3) enhancement of ancestral sites through the use of the Huron-Wendat language to rename and commemorate them; and (4) retelling Huron-Wendat history through cultural and artistic projects in close consultation with all levels of government, other local Indigenous nations, private developers, towns, and large corporations (Hawkins and Lesage Reference Hawkins and Lesage2018).

Until recently, the Huron-Wendat and other Indigenous nations have been denied their rights to their archaeological heritage and to the bones and spirits of their ancestors. Over the last century, the archaeological investigation of the Huron-Wendat in Ontario has been very colonial and has involved the excavation of dozens of village sites and thousands of buried ancestors to satisfy the scientific curiosity of non-Indigenous archaeologists, mostly without the involvement or consent of the Huron-Wendat (Hawkins and Lesage Reference Hawkins and Lesage2018; Warrick Reference Warrick2018). The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (United Nations General Assembly 2007) and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015) clearly state that Indigenous peoples have an inherent right to the protection of their ancestors and heritage. Although neither of these documents has been enshrined yet in Canadian law, both have been adopted in the ethical principles of the Ontario Archaeological Society (2017) and the Canadian Archaeological Association (2018). In support of Indigenous rights and in situ preservation of archaeological heritage, an increasing number of archaeologists are recommending less excavation and removal of in situ archaeological materials (Colwell Reference Colwell2016; Ferris and Welch Reference Ferris, Welch, Atalay, Claus, McGuire and Welch2014).

In Ontario, Indigenous nations are asserting their rights to their ancestors and archaeological sites, and they want to protect them from disturbance, whereas most archaeologists work for land developers whose modus operandi is to find and excavate any archaeological site that is in the path of development (Warrick Reference Warrick2017). Indigenous peoples are asking archaeologists to locate the buried sites of their ancestors and to conduct limited investigation designed to determine the size, age, integrity, and unique characteristics—but then to leave them alone (Ferris and Welch Reference Ferris, Welch, Atalay, Claus, McGuire and Welch2014; Warrick Reference Warrick2017). Standard methods of site investigation in Ontario (Ministry of Tourism and Culture 2011) involve excavation of test units that have the risk of disturbing human burials and other spiritual or culturally sensitive features. Consequently, to reduce the risk of doing harm to the ancestors and to preserve sites for the future, Indigenous peoples such as the Huron-Wendat want archaeologists to cause as little disturbance to a site as possible (Williamson Reference Williamson2014), preferably using noninvasive remote sensing methods in place of excavation (Glencross et al. Reference Glencross, Warrick, Hawkins, Eastaugh, Hodgetts and Lesage2017).

On June 15, 2015, the Huron-Wendat Band Council unanimously adopted a resolution to protect its archaeological and cultural heritage in Ontario—particularly burial sites—from development projects (Conseil de la Nation huronne-wendat 2015:4). Although the Ontario government is required under Canadian law to engage with and accommodate the rights of the Huron-Wendat Nation to their archaeological heritage, the Huron-Wendat Nation, also under Canadian law, have no veto power over development projects that will disturb archaeological sites.

In Ontario, 99% of the archaeological activity is CRM archaeology in advance of land development. Under the regulations of the Ontario Heritage Act (R.S.O. 1990), when an archaeological site is found and investigated, archaeologists are required to undertake test excavation to secure artifact samples and to determine site age, size, and integrity (Warrick Reference Warrick2017). Remote sensing methods are precluded because legal regulations require that the findings be subjected to ground-truth excavation. In most cases, Huron-Wendat archaeological sites that are located on land proposed for development are fully or partially excavated (Williamson Reference Williamson2010). In other words, only research archaeological investigations of Huron-Wendat sites (about 1% of all licenced archaeology in Ontario) are able to apply remote sensing methods and avoid test excavations.

Despite the regulated emphasis on test and mitigative excavation in most of Ontario archaeology, the Huron-Wendat see value in developing and applying remote sensing methods to help them fulfill their responsibilities to their ancestors in three specific ways: (1) to develop an inventory of village and burial sites (having a complete inventory of village and burial sites would enable governments, municipalities, and developers to protect these sites from destruction in land use planning), (2) to minimize excavation of village sites (such sites act as physical reminders for the Huron-Wendat of their ancestral territory), and (3) to prohibit disturbance of buried ancestors.

Inventory of Village and Burial Sites

There are a finite number of Huron-Wendat village and associated burial sites, and not all of them are known. It has been estimated that the total number of Huron-Wendat village sites that were constructed and inhabited between AD 1000 and 1650 is 750 (Warrick Reference Warrick2008:105–107). The Huron-Wendat currently claim a relationship to over 800 sites in Ontario (Wendake South; Nionwentsïo Office, Nation Huronne-Wendat 2020). As a result of undocumented destruction during urbanization and recent archaeological excavation in the course of land development, it has been estimated that as many as 300–400 village sites (and about 8,000 ancestral Huron-Wendat sites of all ages in greater Toronto alone [Coleman and Williamson Reference Coleman, Williamson and MacDonald1994]) have been erased from the landscape over the last 150 years (Warrick Reference Warrick2017; Williamson Reference Williamson2010). In addition to village destruction, a minimum of 200 burial sites (i.e., ossuaries) have also been destroyed. After AD 1300, ossuary burial—commingled interment in one large burial pit of all villagers who had died over the 10- to 30-year life of a village—defined Huron-Wendat mortuary behavior. Ossuaries are notoriously underrepresented in the inventory of archaeological sites in Ontario, partly because well over 150 of them were looted and destroyed by nineteenth-century land clearance and farming activity (and many never documented; Hunter Reference Hunter1888:58) and because they are extremely difficult to find with traditional archaeological survey techniques. Ossuary pits are typically 1.5–2.0 m deep and 4–5 m in diameter (Williamson and Steiss Reference Williamson, Steiss, Williamson and Pfeiffer2003). They elude detection in archaeological survey for two reasons: (1) ploughing is not deep enough to disturb buried skeletal remains, so there is no trace on the surface of a ploughed field; (2) shovel test assessment is carried out at a 5 m interval, so there is a very low probability of a shovel test pit intersecting an ossuary pit. In addition, ossuaries were placed up to hundreds of meters from the contributing village site (Williamson and Steiss Reference Williamson, Steiss, Williamson and Pfeiffer2003), well beyond the gaze of archaeologists. Nonetheless, during land development, ossuaries are occasionally encountered and disturbed accidentally by heavy machinery, with devastating results—for example, Ontarajia ossuary (Midland Museum) in 2003 and Teston Road ossuary in 2005 (Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing 2009). The Huron-Wendat would like an inventory of village and ossuary sites so that they can be protected from development. Some remote sensing methods, particularly magnetic gradiometer (for open, unploughed areas) and soil chemistry (forested areas), would be ideal for locating village and ossuary sites in the absence of surficial archaeological evidence (see below).

Minimizing Site Excavation

Huron-Wendat archaeology has a long history of excavating village sites. In the early twentieth century, archaeological attention was focused on the excavation of Attawandaron, Huron-Wendat, and St. Lawrence Iroquoian village sites. W. J. Wintemberg's excavations (1912–1930) of the Uren, Lawson, and Middleport village sites in southwestern Ontario as well as the Roebuck site in eastern Ontario revealed midden areas, post-mold patterns of longhouses and palisades, and scattered human remains and burials within the village areas. University and museum archaeologists (mostly University of Toronto and the Royal Ontario Museum), under the banner of settlement pattern archaeology (Trigger Reference Trigger1967), excavated a number of Huron-Wendat villages between 1950 and 1980 (Williamson Reference Williamson2014). The excavation of village sites continued unabated from the 1970s until the 2010s in the context of land development. Despite recommendations from the Ontario Ministry of Heritage, Tourism, Sport and Culture Industries (OMHSTCI) to protect Huron-Wendat village sites from land development (Ministry of Tourism and Culture [Ontario] 2011), Huron-Wendat sites were and continue to be routinely excavated by consulting archaeologists, particularly in the cities of Barrie and Toronto (Williamson Reference Williamson2010). The Ontario government has failed to force developers to both avoid and protect archaeological sites (Warrick Reference Warrick2017). Although much has been learned from all of these village excavations—such as population history (Warrick Reference Warrick2008), sociopolitical development and dynamics (Birch Reference Birch2012), architectural features (Kapches Reference Kapches1993; Knight Reference Knight1987), household proxemics (Creese Reference Creese2012), and ethnic diversity (Ramsden Reference Ramsden2016)—the cost of this knowledge has been the erasure of dozens of ancestral villages from the Huron-Wendat cultural landscape and the disturbance and displacement of the ancestors themselves from their graves. As remarked above, of the original inventory of 750 Huron-Wendat village sites in south-central Ontario, only about 400 are extant. In accordance with the Huron-Wendat archaeological resolution, the excavation of entire villages must stop and be replaced with remote sensing investigation.

Avoiding Disturbance of Buried Ancestors

The most significant harm posed by archaeology to the Huron-Wendat Nation is the disturbance of buried ancestors. After AD 1300, the Huron-Wendat buried their dead in ossuaries, except for a few individuals who were interred in shallow graves within a village or nearby cemetery (Williamson and Steiss Reference Williamson, Steiss, Williamson and Pfeiffer2003). In Huron-Wendat beliefs, a living spirit still remains in the bones of the dead. Consequently, the burial places of ancient villagers are sacred and must not be disturbed. Despite the sacredness of burials, ossuaries and burials in villages were routinely excavated out of curiosity by the general public and the first archaeologists in Ontario, with skeletal remains being displayed on mantelpieces in private homes and dispersed to medical schools and museums—in some cases overseas (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2010). Between 1940 and 2005, archaeologists disinterred thousands of Huron-Wendat ancestors from 18 ossuaries and a number of villages (e.g., Miller, Ball, Keffer, Mantle [Jean-Baptiste Lainé]; Birch and Williamson Reference Birch and Williamson2013:152–155; Williamson and Steiss Reference Williamson, Steiss, Williamson and Pfeiffer2003). In 1999 and 2013, over 2,000 of those ancestors were repatriated from museum and university shelves and reburied with ceremony (Kapches Reference Kapches2010; Pfeiffer and Lesage Reference Pfeiffer and Lesage2014), but still hundreds wait to be returned to the earth. The Huron-Wendat have called for a moratorium on the excavation of their ancestors, from either ossuaries/cemeteries or villages, because of centuries-old spiritual obligations to protect and honor their final resting place (Birch and Williamson Reference Birch and Williamson2015; Pfeiffer and Lesage Reference Pfeiffer and Lesage2014), as well as to prevent psychological harm to the living. Nonetheless, despite the moratorium, Huron-Wendat burial places continue to be disturbed and destroyed, mainly because the Ontario government and archaeologists have made no effort to find and protect them (Warrick Reference Warrick2018). The most recent case of ossuary disturbance is the Allandale site (BcGw-69), in Barrie, Ontario, where archaeological assessment has been ongoing since 2016. Huron-Wendat representatives are on site to monitor the work, participate in decision making, and provide guidance to ensure that the archaeology is culturally respectful (Jackson Reference Jackson2016, Reference Jackson2018).

The Huron-Wendat moratorium against disturbance of ancestral burials applies to not only ossuaries but also village sites. Huron-Wendat village sites often contain a few buried individuals, and their location is somewhat unpredictable. As a result, any partial or complete village excavation has a strong probability of disturbing buried ancestors (e.g., Mantle, Ball, Draper sites [Birch and Williamson Reference Birch and Williamson2013; Knight and Melbye Reference Knight and Melbye1983; Williamson Reference Williamson1979]). In addition, scattered human remains are often found in middens and other pit features in villages (Williamson Reference Williamson, Chacon and Dye2007). Consequently, any subsurface excavation of a village site has a probability, albeit small, of disturbing buried human remains. The use of remote sensing methods instead of excavation would greatly reduce disturbance of the ancestors.

In consideration of the history and scale of village destruction already carried out by archaeologists and others—and the desire of Huron-Wendat to document and characterize the few remaining sites while avoiding disturbance of buried ancestors—we developed a remote sensing and sustainable archaeology project in collaboration with the Huron-Wendat at the Ahatsistari site. In the remainder of the article, we present recent and ongoing research using remote sensing to reveal the size and layout of Ahatsistari and other Huron-Wendat village sites.

REMOTE SENSING AND HURON-WENDAT ARCHAEOLOGY: BENEFITS AND CHALLENGES

The application of remote sensing methods in Huron-Wendat archaeology began in 1969 with soil chemistry survey of a Huron-Wendat village as part of a University of Toronto research project (Heidenreich and Konrad Reference Heidenreich and Konrad1973). Results were intriguing, but Ontario archaeologists saw no benefit in developing these methods further because the acceptable method of investigating a Huron-Wendat village site was excavation. Until the late 1990s, excavation of Huron-Wendat sites proceeded with little concern for the Huron-Wendat people or their cultural/spiritual values. Since the reburial of Huron-Wendat ancestors in the Ossossane ossuary in 1999 (Kapches Reference Kapches2010), archaeologists working on Huron-Wendat sites have become more aware of the impact of archaeological excavation, and they have begun experimenting again with remote sensing as an alternative to excavation. In Ontario, over the last decade, Indigenous rights declarations, legal decisions granting more Indigenous control of archaeology, and the new ethic of sustainable archaeology promoting site preservation (Warrick Reference Warrick2017) have given new impetus to the development of noninvasive methods of investigation of Huron-Wendat sites. It is in response to these developments that our own work at the Ahatsistari village site prioritized noninvasive remote sensing methods in a university field school context (Glencross et al. Reference Glencross, Warrick, Hawkins, Eastaugh, Hodgetts and Lesage2017).

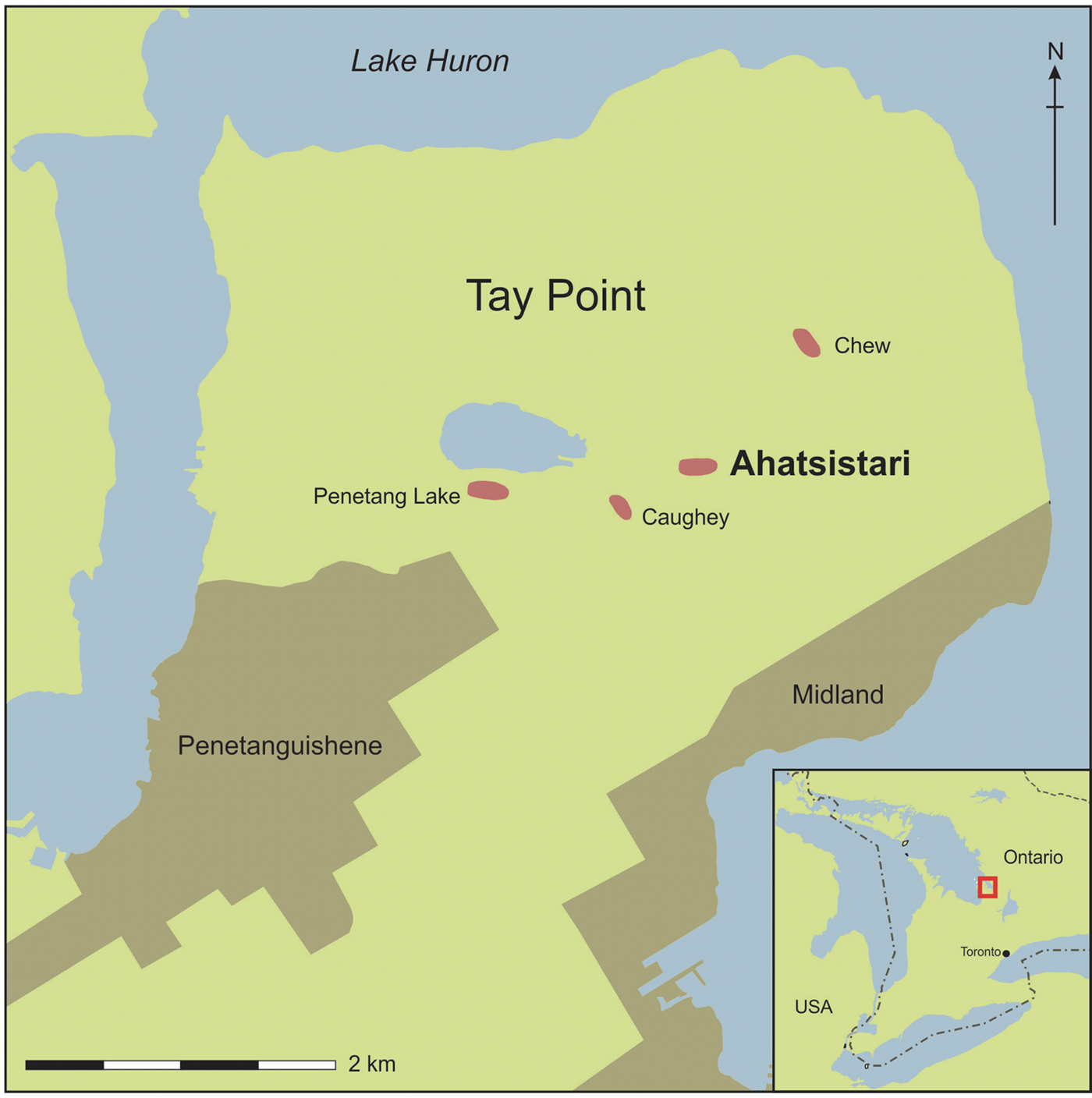

Ahatsistari Site (BeGx-76) and Wilfrid Laurier University Field School

The Ahatsistari site (BeGx-76) was discovered in 2012 by an avocational archaeologist (Gary DuBeau) who was looking for mushrooms in the forests north of Penetanguishene, on Tay Point in Simcoe County, Ontario (Figure 1). He saw artifacts scattered in freshly dug backdirt on the steep bank of a cold-water stream, evidence of illicit digging by pothunters. He alerted the local archaeological community, and Alicia Hawkins (Laurentian University) registered the site and supervised the excavation and sieving of backdirt from the hillside midden by volunteers from the Huronia Chapter of the Ontario Archaeological Society (OAS). Recovered artifacts indicated an early seventeenth-century age for the site (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2014). In 2013, Hawkins returned to the site to conduct a shovel test pit assessment of the site as part of her summer field school, which revealed that the site was a large village of over 2 ha, and she supervised additional sieving of pothunter backdirt and stabilization of the hillslope midden by OAS volunteers (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2015). Bonnie Glencross and Gary Warrick participated in the 2013 excavations and became interested in the site as a location for a Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies, Wilfrid Laurier University (WLU) multiyear field school, beginning in 2014.

FIGURE 1. Location of Ahatsistari site (BeGx-76; map drawn by Edward Eastaugh, Western University, ON).

So, in the fall of 2013, in recognition of Indigenous rights to cultural heritage and the ethics of Indigenous archaeology, and following the helpful advice of archaeologist Alicia Hawkins (Hawkins and Lesage Reference Hawkins and Lesage2018; Hawkins and Raynor Reference Hawkins, Raynor, Dorais and Lainey2012), Glencross and Warrick asked the Huron-Wendat Nation if they could undertake a field school at Ahatsistari. Chief Line Gros-Louis and staff of the Nionwentsïo Office, Huron-Wendat Nation (Louis Lesage, Simon Picard, and Mélanie Vincent) were consulted. Glencross and Warrick reassured the Huron-Wendat Nation that the goal of the field school would be to teach students how to conduct archaeology responsibly, sustainably, and with sensitivity to Huron-Wendat concerns about archaeology, adhering to the tenets of Indigenous archaeology. The Huron-Wendat agreed to let the field school proceed, with the following stipulations: (1) they would receive regular updates as well as copies of reports and publications; (2) all work would cease if human remains were uncovered; and (3) noninvasive remote sensing methods would be applied, with minimal site excavation. Consequently, WLU field schools at the Ahatsistari site adopted a minimally invasive sustainable archaeology approach, designed to disturb as little of the site as possible. Minimally invasive methods used in the field schools (2014, 2016, 2018) included surface survey (to determine midden locations), strategically placed test excavation units in backdirt from looted middens (to secure artifact and ecofact samples using fine-sieve water screening and flotation) and on the village periphery (to delineate site limits and palisade lines), magnetic susceptibility survey, metal detector survey, and high-resolution soil chemistry survey (to explore the internal structure of the village and locate houses; Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Glencross, Warrick and Reinhardt2019; Glencross Reference Glencross2016, Reference Glencross2018; Glencross et al. Reference Glencross, Warrick, Hawkins, Eastaugh, Hodgetts and Lesage2017).

The use of remote sensing methods on a Huron-Wendat village site does little damage and upholds Huron-Wendat responsibilities to the ancestors by minimizing the risk of disturbing buried human remains. Insufficient studies have been carried out, however, to rely exclusively on remote sensing to reveal the layout and structure of a village site. At this point in Huron-Wendat archaeology, the results of remote sensing are often ambiguous or inconclusive, and they require ground-truthing (i.e., subsurface test excavation) to demonstrate that the remote sensing has actually located buried cultural features (e.g., hearths, storage pits), longhouse floors, palisade lines, village limits, and concentrations of seventeenth-century European metal artifacts. Remote sensing methods have enormous potential, but they are not sufficiently reliable at the moment without verification through excavation. The following sections summarize the remote sensing (geophysical prospection) and other methods (metal detection, soil chemistry survey, magnetic susceptibility survey, and magnetometer and resistivity survey) applied to Ahatsistari and other Huron-Wendat sites, with comments on the benefits and challenges of using each one to reveal the layout, structure, and features of village sites.

Metal Detection

The use of metal detectors on archaeological sites tends to be associated in the minds of most professional archaeologists with pothunters or looters. Metal detectors in the hands of highly experienced operators, however, can be a powerful tool for finding site limits and tracing patterns of metal artifacts. In North America, metal detectorists have assisted archaeologists in mapping colonial-period habitation and battlefield sites (Connor and Scott Reference Connor and Scott1998), but metal detectors have been used sparingly on seventeenth-century Huron-Wendat village sites. In 2005, metal detection survey attempted to locate the limits of the Ossossane site and grid stakes from previous excavations (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2007), and in 2015, Alicia Hawkins supervised Laurentian University field school students in a metal detector survey of the seventeenth-century component of the Ellery site but did not excavate detector hits. It must be noted, however, that Huron-Wendat village sites do contain varying quantities of eighteenth- to twenty-first-century metal (colonial settler activity) that is virtually impossible to differentiate from seventeenth-century metal without recovering and examining the object. Given that positive metal-detector hits must be unearthed to identify them as seventeenth century, metal detector survey accompanied by shovel testing each detector hit (30 × 30 cm test pits) was undertaken at the Ahatsistari site field schools in 2016 and 2018. The 2016 detector survey covered a 90 × 10 m area in meter-wide transects, running east-west across the center of the village site with the aim of uncovering metal artifacts left in and around longhouse floors (Figures 2 and 3). The Teknetics Delta 4000 metal detectors used have a subsurface range of only 28 cm, and students were instructed not to dig deeper than 30 cm to retrieve metal objects so as to minimize disturbance of in situ deposits below topsoil. Nonetheless, the depth of topsoil on the site is relatively shallow (15–20 cm), and the top portions of subsurface pit features may have been disturbed in some cases during test pit confirmation of detector hits. Students were also instructed to maintain the integrity of each shovel test pit and to not “chase” detected objects when a metal object was not recovered in the initial shovel test pit. All detector hits / test pits were mapped with a laser transit and tied into the site grid (Glencross et al. Reference Glencross, Warrick, Hawkins, Eastaugh, Hodgetts and Lesage2017).

FIGURE 2. Wilfrid Laurier University archaeology field school students laying out a 10 × 10 m unit for metal detection at the Ahatsistari site in 2016 (photograph by Bonnie Glencross).

FIGURE 3. Metal detection at the Ahatsistari site in 2016 (photograph by Bonnie Glencross).

Metal detector survey (accompanied by shovel testing of detector hits) is the most invasive of remote sensing methods used on Huron-Wendat villages. Its use was justified at Ahatsistari for two reasons. First of all, metal items in seventeenth-century Attawandaron (Neutral) and Huron-Wendat sites are concentrated in midden areas and longhouse floors. In longhouses, most metal items—particularly iron axes, knives, and large pieces of brass/copper kettles—are situated in pit features under the bunklines (just inside the sidewalls of the houses) or in the end cubicles of houses. For example, in Attawandaron sites such as Fonger (late sixteenth century) and Walker (seventeenth century), and in the Huron-Wendat Molson site (seventeenth century), European metal items were most frequently situated in storage or bunkline support features near the side and end walls of longhouses (Lennox Reference Lennox2000; Warrick Reference Warrick1983:91; Wright Reference Wright1981). The Huron-Wendat stored “their most precious possessions” (presumably valuable iron axes) in pits dug in longhouse floors to protect them from house fires and theft (Wrong Reference Wrong1939:95). Consequently, linear patterns of axes, knives, and kettle parts that are not in village middens might reveal the location of longhouse walls. In the future, metal detection without shovel test pitting could be used on Huron-Wendat village sites to plot the iron and brass/copper detector hits (e.g., iron axes, kettle parts) that could help to identify longhouse walls. The second reason for metal detection combined with retrieval of discovered items at Ahatsistari is that the site has been and continues to be damaged by pothunters and metal detectorists. As a result, in anticipation of major damage and loss of items from illicit digging in the near future, it was important to remove a sample of seventeenth-century metal items from the relatively unlooted village floor to assess the density of European metal items in the site.

The majority of detected objects at Ahatsistari were confirmed seventeenth-century European artifacts through shovel test pit recovery. Several artifact clusters were recognized as either small caches or large, widely distributed concentrations of artifacts. The caches are identified on the basis of artifacts found within a single shovel test pit, and they are thought to have been intentionally deposited together. Although the total number of artifacts recovered from each of the caches is small, the artifacts recovered represent valued trade items (i.e., two or more iron trade axes, bundled copper strips; Figure 4). Larger concentrations were recognized by comparing the proportions of metal artifacts across units with the expectation that higher densities represent foci, such as living floors of longhouses or other areas of localized activity. Additional work is still needed, however, including the expansion of the metal detector shovel test pit survey to encompass a larger area, as well as ground truthing with excavated units to confirm the location of features and longhouses. As noted earlier, the probability of encountering human remains within a village and/or house is quite low, but a slight risk of disturbing ancestral remains during the recovery of items from a shovel test pit persists. Nonetheless, the Huron-Wendat feel that the potential gain of information on village settlement patterns from metal detector survey with recovery of finds, which is far less intrusive than traditional test excavation, is worth the small risk of disturbing buried ancestors.

FIGURE 4. Seventeenth-century iron axes found in the same test pit dug to verify a positive metal detector hit at the Ahatsistari site in 2016 (photograph by Bonnie Glencross).

Soil Chemistry Survey

Soil chemistry survey can be a quick and reliable remote sensing method for determining the location of longhouse floors, footpaths, pit features, and limits of a Huron-Wendat village site (Birch Reference Birch2016; Griffith Reference Griffith1981; Heidenreich and Konrad Reference Heidenreich and Konrad1973; Heidenreich and Navratil Reference Heidenreich and Navratil1973). The first soil chemistry survey of a Huron-Wendat village was completed during the 1969 excavation of the Robitaille site, a forested seventeenth-century site on the Penetang Peninsula, Simcoe County. Soil chemistry analyses revealed the location of longhouse floors and site limits, as well as midden locations (Heidenreich and Konrad Reference Heidenreich and Konrad1973; Heidenreich and Navratil Reference Heidenreich and Navratil1973). In the late 1970s, another soil chemistry investigation was completed at the Benson site, an unforested sixteenth-century Huron-Wendat village. Samples were collected from an excavated longhouse on a 1 m grid, and the soils of former footpaths outside the house were chemically distinguishable from middens, as well as pit features and post molds inside the house (Griffith Reference Griffith1980, Reference Griffith1981). Despite the relative success of these pioneering soil chemistry surveys, there were no further studies carried out for over four decades. This is primarily because archaeologists considered such surveys a waste of time, given that site excavation—the unquestioned standard method for doing Huron-Wendat archaeology until the early 2000s—revealed houses and settlement layout. In light of recent Huron-Wendat demands for less excavation, however, soil chemistry survey of village sites is experiencing a revival. Soil phosphate samples were collected in 2014 from the Trent-Foster site (see above) at a 10 m interval, in conjunction with gradiometry and magnetic susceptibility survey. Soil chemistry patterns showed some overlap with magnetic anomalies, but overall, the results were ambiguous (Conger and Birch Reference Conger and Birch2019). Also, in 2014, in addition to magnetic gradiometry and susceptibility survey, soil chemistry survey was completed for a portion of the Spang site, a late sixteenth-century Huron-Wendat village near Toronto (Birch Reference Birch2016). Soil phosphate patterns (from 10 m interval data) at this site are interpreted as possible middens or refuse-filled features in a central village plaza (Birch Reference Birch2016). In 2016, a soil phosphate survey using a 10 m interval was conducted at Hamilton-Lougheed, a Tionontate (Petun) village site, in the same area of gradiometer and magnetic susceptibility survey (see above). Although soil chemistry confirmed known midden locations, the patterns were not sufficiently focused to identify longhouse floors (Conger and Birch Reference Conger and Birch2019). None of the latter studies were verified with test excavation, so inferred longhouse locations and middens that were published should be considered questionable.

High-resolution soil chemistry survey was completed in 2018 and 2019 at the Ahatsistari site. Beatrice Fletcher, a doctoral student at McMaster University, collected and analyzed soil samples taken with a 2.5 cm diameter handheld coring device at 25 cm intervals on an east-west transect designed to intersect palisade lines and village limits and a portion of the village interior, in which both magnetic susceptibility and metal detection indicated possible longhouses (Figure 5). Analyses are ongoing, but preliminary results show that high-resolution soil samples can find village limits and locate longhouse floors with considerable precision (Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Glencross, Warrick and Reinhardt2019). More research is warranted for high-resolution soil chemistry, in tandem with magnetic susceptibility or magnetic gradiometry, to locate the central hearths of longhouses. Of all the remote sensing methods, the Huron-Wendat endorse soil chemistry as holding the highest potential for revealing village layout without excavation. Its use should be encouraged with the new generation of archaeologists so that better respect is given to Huron-Wendat archaeological sites.

FIGURE 5. High-resolution soil chemistry survey being conducted at the Ahatsistari site in 2018 (photograph by Bonnie Glencross).

Magnetic Susceptibility Survey

Magnetic susceptibility survey is a powerful remote sensing method that, unlike magnetometer survey, can be used in forested contexts. There have been two recent applications of magnetic susceptibility on Iroquoian village sites, with varying levels of success. The first survey was carried out in 2014 on a forested St. Lawrence Iroquoian site in Quebec, Mailhot-Curran, and it accurately located central hearths of longhouses that were verified by excavation (Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Millaire, Eastaugh and Chapdelaine2016). The second survey was completed at the Ahatsistari site in Ontario but failed to locate hearths. Several longhouse floors (oriented northeast-southwest) were inferred from the patterns of magnetic anomalies. Four detected anomalies, suspected central hearths, were ground truthed. Although one contained a concentration of fire-cracked rock, the others failed to provide any evidence of the presence of a feature or burning (Glencross et al. Reference Glencross, Warrick, Hawkins, Eastaugh, Hodgetts and Lesage2017). In fact, there is a good probability that the magnetic anomaly patterns at Ahatsistari may be more reflective of underlying glacial till deposits, not seventeenth-century cultural activity (Glencross et al. Reference Glencross, Warrick, Hawkins, Eastaugh, Hodgetts and Lesage2017). As is the case with magnetometer and resistivity surveying, magnetic susceptibility survey cannot currently be relied on to produce a map of the layout of a Huron-Wendat village without supporting data—that is, test excavation. If, however, magnetic susceptibility is targeted at finding only hearth features (i.e., longhouse floors) in a Huron-Wendat village, there is minimal risk of disturbing human remains from test excavation to verify hearth feature locations.

Magnetometer, Magnetic Gradiometer, and Resistivity Survey

Magnetometry and resistivity survey require unimpeded linear transects across an archaeological site, which is virtually impossible on a heavily forested site such as Ahatsistari. Despite the problems with applying these methods to forested sites, most Huron-Wendat village sites are situated in ploughed fields, and they could benefit from these remote sensing methods. Magnetometry and resistivity surveys of Huron-Wendat sites have been conducted on several Huron-Wendat village sites in ploughed fields. One of the first applications of magnetometry in Huron-Wendat archaeology occurred in 2005 and 2006. In collaboration with the Huron-Wendat, Alicia Hawkins (Reference Hawkins2007) conducted geophysical survey of the Ossossane site (BeGx-25), a ploughed seventeenth-century village site. Magnetometer and resistivity survey were carried out. The magnetometer survey was designed to locate previous excavation trenches, not longhouses or pit features. None of the excavation trenches were found, but there were a number of anomalies that might indicate seventeenth-century iron objects (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2007:12). Resistivity survey was applied to one of the magnetometer anomalies, but the resistivity readings did not pick up the anomaly. Investigators believe that the anomaly is probably a bedrock feature or subsurface water.

More recent successful experiments have been conducted with magnetic gradiometer and resistivity survey on a Huron-Wendat special-purpose site as well as four Huron-Wendat and one Tionontate village sites. In the course of CRM archaeology in 2008, ASI examined a small area of a special-purpose site (Trio, early sixteenth century) and successfully identified a longhouse interior that was later excavated. Additionally, ASI surveyed portions of two Huron-Wendat village sites with a magnetic gradiometer prior to mitigative excavation. Survey of a small area of the Damiani site (fifteenth century) in 2008 revealed the other half of a previously excavated longhouse and activity associated with a palisade, verified by subsequent excavation. In 2012, magnetometry at the Skandatut site (late sixteenth century) found a linear anomaly at the site edge matching the location of a palisade line later found in excavation (Kellogg Reference Kellogg2014). In 2014 and 2016, the Spang site (sixteenth century), Trent-Foster site (sixteenth century), and the Hamilton-Lougheed site (seventeenth century) were investigated with magnetic gradiometry and resistivity survey (Birch Reference Birch2016; Conger and Birch Reference Conger and Birch2019). Longhouses, middens, and possible pit features in an open plaza were inferred from the pattern of magnetic anomalies at these sites, but no test excavation was carried out to verify the inferred findings.

To date, studies in both CRM and research contexts demonstrate that magnetometry and resistivity survey do have the potential to locate longhouse floors, pit features, and palisade lines in Huron-Wendat village sites in ploughed fields. More experimentation is needed, but to determine the reliability and accuracy of these remote sensing methods, test excavation of anomalies must be carried out. In other words, in the process of refining magnetometry and resistivity survey as reliable methods of revealing the layout and features of a Huron-Wendat village, excavation will need to occur. In addition to locating village sites and their layout, magnetometry and resistivity survey could help to find ossuaries on unforested lands. Although a soil probe or coring device could be used to verify that an anomaly was in fact an ossuary—a method that might be acceptable to the Huron-Wendat in certain circumstances—coring would cause considerable damage to human remains in the path of the coring device.

CONCLUSION

For Huron-Wendat village sites located in forests or without surface visibility (unploughed pasture), remote sensing methods (particularly metal detection, soil chemistry survey, and magnetic susceptibility survey)—although still in the exploratory/experimental stage—hold promise for determining site limits as well as the location of pit features, middens, and longhouses with minimal or no disturbance. Application of such methods will directly address Huron-Wendat concerns about the destructive nature of traditional archaeological practices. In doing so, collaborative work between archaeologists and the Huron-Wendat will be strengthened.

The most serious limitation of remote sensing methods, however, is that they are currently not fully reliable on their own and require verification with test excavation. All or some of the methods described in this article may or may not be suitable for all projects, and in fact, it may be necessary to use multiple techniques to ensure a more thorough investigation of a given site. It is also recognized that when minimally invasive methods are applied, fewer artifacts will be recovered, thereby impacting the amount of data recovered. This runs counter to the full excavation required during CRM development–related mitigation, where the priority is to excavate and record as much as possible before development. Some would argue that full excavation will always be necessary in salvage situations, and complete village excavations, as mentioned earlier, have provided unique insights on Huron-Wendat history (see Williamson Reference Williamson2014). In fact, the recent partnership between the Huron-Wendat and ASI (Yändata’) contains provisions for involvement of Huron-Wendat in site excavation, if deemed unavoidable due to public interest or to provide data to better understand their history, as a component of Huron-Wendat archaeological heritage management (ASI 2020). Nevertheless, the Ontario government and CRM archaeologists need to be encouraged to employ remote sensing in place of excavation where possible, with all parties recognizing that test excavation will continue to be part of remote sensing methods on Huron-Wendat sites for the foreseeable future. In the future, archaeologists working on Huron-Wendat sites will have to better collaborate with the Huron-Wendat Nation from the beginning of any archaeological work and avoid all unnecessary excavation in order to uphold the cultural and spiritual responsibilities of the Huron-Wendat to protect their ancestors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Huron-Wendat Nation for its unflagging support of the Wilfrid Laurier University field school at the Ahatsistari site. Graeme Davis, Senior Forester, County of Simcoe, gave permission to enter the property on which the Ahatsistari site is situated. We extend our gratitude to our colleagues Ed Eastaugh and Lisa Hodgetts, who completed the magnetic susceptibility study in 2014 and 2015, and Beatrice Fletcher, who carried out the high-resolution soil chemistry survey of the site in 2018 and 2019. In addition, Alicia Hawkins has been an extremely supportive colleague over the last few years, and she has provided welcome advice, access to unpublished reports, and the impetus for engaging in sustainable field school archaeology at the Ahatsistari site. Matt Sanger (guest editor) and three anonymous reviewers provided recommended changes to the original draft and improved the article considerably. Last, we would like to acknowledge all of the WLU students who participated in the WLU field schools in 2014, 2016, and 2018, and who enthusiastically embraced sustainable archaeology and recognized that minimally invasive methods such as remote sensing are the way of the future. Fieldwork in 2014, 2016, and 2018 was conducted under archaeological licences P-377-0001-2014, P-377-0002-2016, and P-377-0003-2018, issued to Bonnie Glencross by the Ontario Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries.

Data Availability Statement

No original data were presented in this article.