In psycholinguistic research, there has been considerable debate over how number information is represented in cognitive processing of both one’s first language (e.g., Patson, George, & Warren, Reference Patson, George and Warren2014) and one’s second language (e.g., Foote, Reference Foote2010; Hoshino, Dussias, & Kroll, Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010; Wei, Chen, Liang, & Dunlap, Reference Wei, Chen, Liang and Dunlap2015). One way of investigating the interface between morphosyntactic processing and semantic or conceptual processing is to examine how comprehenders process number agreement in various constructions (e.g., Bock & Miller, Reference Bock and Miller1991; Bock & Eberhard, Reference Bock and Eberhard1993; Eberhard, Reference Eberhard1997, Reference Eberhard1999; Humphreys & Bock, Reference Humphreys and Bock2005). One reason for investigating the number agreement process is that although number agreement has been considered almost solely in terms of grammatical processing, researchers have found that in some cases conceptual information invades grammatical processing, as we will review later in this paper (e.g., Humphreys & Bock, Reference Humphreys and Bock2005).

Even first language (L1) English speakers are likely to make agreement errors when the number of a local noun phrase (NP) mistakenly agrees with the verb, such as in the gang on the motorcycles were …. (Humphreys & Bock, Reference Humphreys and Bock2005). In addition to the conceptual plurality present in collective nouns, comprehenders also use conceptual number/plural information denoted by means such as an NP consisting of a singular head NP and a plural local NP: the label on the bottles was/were … (e.g., Eberhard, Reference Eberhard1999). In this case, comprehenders conceptually represent multiple bottles with the same label (i.e., identical labels) attached to them, and thereby the number of label becomes conceptually plural. The evidence of the use of conceptual number information during language processing has been found both in production (e.g., Bock, Eberhard, Cutting, Meyer, & Schriefers, Reference Bock, Eberhard, Cutting, Meyer and Schriefers2001; Bock, Nicol, & Cutting, Reference Bock, Nicol and Cutting1999, Eberhard, Reference Eberhard1999) and in comprehension (e.g., Kreiner, Garrod, & Sturt, Reference Kreiner, Garrod and Sturt2013; Nicol, Forster, & Veres, Reference Nicol, Forster and Veres1997; Pearlmutter, Garnsey, & Bock, Reference Pearlmutter, Garnsey and Bock1999). Though most of the studies mentioned above focused on L1 sentence processing, other research has investigated whether or not second language (L2) speakers can show a processing tendency similar to that L1 speakers are known to use (Foote, Reference Foote2010; Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010; Nicol & Greth, Reference Nicol and Greth2003; Nicol, Teller, & Greth, Reference Nicol, Teller and Greth2001; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Chen, Liang and Dunlap2015). Possible cognitive overload in online tasks partially due to low language proficiency (Foote, Reference Foote2010; Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010; Jackson, Mormer, & Brehm, Reference Jackson, Mormer and Brehm2018) and the characteristics of the learners’ L1 (Jackson, Mormer, & Brehm, Reference Jackson, Mormer and Brehm2018; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Chen, Liang and Dunlap2015) are considered to be factors that hinder the use of conceptual number information in number agreement.

Despite our awareness of these factors, however, L2 studies investigating the availability of conceptual information in online sentence processing have mostly been based on eliciting number agreement errors. Just as L1 studies have reinforced the results obtained through the agreement attraction effect with those from tasks that investigated various types of conceptual plurality (e.g., Patson, George, & Warren, Reference Patson, George and Warren2014), L2 studies also have to move beyond the number agreement phenomenon, as there are other situations where conceptual plurality is critical in language processing; for example, the processing of reciprocal verbs (e.g., Patson & Ferreira, Reference Patson and Ferreira2009).

To investigate the role of conceptual plurality in the processing of reciprocal verbs, the present study developed a sentence comprehension task making use of the traditional psycholinguistic technique of self-paced reading. The logic behind this approach is demonstrated by an interesting property of reciprocal verbs, as shown in (1).

(1) a. Ken met Natsuko yesterday. (transitive reading)

b. Ken and Natsuko met yesterday. (reciprocal reading)

c. They met yesterday. (reciprocal reading)

d. *Ken met yesterday. (intransitive reading is not available)

As this example shows, reciprocal verbs can be used both transitively (1a) and reciprocally ([1b] and [1c]). If the reciprocal verbs are used reciprocally, they require two or more people to be involved in the event, as both agent and patient; therefore, if the subject of the sentence carries conceptual plurality, reciprocal verbs are used under the same restrictions as transitive verbs ([1b] and [1c]). In contrast, if the subject of the sentence is singular, the reciprocal verb must have an object or the sentence becomes ungrammatical (1d). As discussed below, Gleitman, Gleitman, Miller, and Ostrin (Reference Gleitman, Gleitman, Miller and Ostrin1996) insist that (1d) “is not ungrammatical; rather, it is semantically ill formed” (p. 354). In addition, if the subject NP is singular, the verb can no longer function as a reciprocal verb because no reciprocal reading is available in that case. Thus, whether reciprocal verbs are being used grammatically or not must involve judgment of the number information of the sentential subject. However, to our knowledge, little L2 psycholinguistic research has investigated whether L2 English speakers understand the characteristics of reciprocal verbs. Therefore, in addition to the online self-paced reading task, we investigated L2 speakers’ knowledge of English reciprocal verbs using an offline sentence completion task in which participants were asked to complete sentences following a sentence fragment (e.g., while the man and the woman dated …./ while the couples dated ….). In the following background sections, we will review in detail how conceptual plurality has been operationalized and investigated in L1 and L2 research.

BACKGROUND

Conceptual plurality in L1 research

How languages express number information varies. In the case of most English nouns, plurality is marked by the bound morpheme –s. Exceptions are irregular nouns (e.g., child–children, cactus–cacti) and nouns that have “zero plurals” (e.g., deer–deer, sheep–sheep). This plural –s represents what is often called morphological or grammatical number. In contrast, there is another type of number information present in the noun phrase, called notional or conceptual number. Conceptual number usually corresponds to grammatical number, but not always. For instance, please see (2a), an author-generated example, below. Looking at (2a), the word scissors is morphologically/grammatically plural in that it has a morphological marker that makes plural agreement with the plural copula are. However, in speakers’ minds, scissors denotes only one entity, meaning it is conceptually singular.

(2) a. The blue scissors are mine.

b. The government is going to put their new policy into action.

Similarly, government in (2b) is grammatically singular because it lacks a plural marker and makes singular agreement with the copula. Nevertheless, the possessive determiner their in the antecedent-anaphora in (2b) shows that the government is treated as plural. In pronoun agreement, unlike subject–verb agreement, singular forms of collective nouns (e.g., government or committee) tend to agree with plural pronouns rather than singular pronouns (e.g., Nicol et al., Reference Nicol, Teller and Greth2001). Note, however, that in specifier–head agreement, singular collective nouns cannot make plural agreement (e.g., these *family/families). This asymmetry demonstrates that both grammatical plurality and conceptual plurality exist and that they have to be considered separately.

Another type of conceptual plural affecting language processing comes from so-called distributive effects (e.g., Eberhard, Reference Eberhard1999; Humphreys & Bock, Reference Humphreys and Bock2005), in which the meaning of the NP can be interpreted as indicating multiple instances of the singular head noun, required by the multiple objects represented by the local plural noun (e.g., the label on the bottles…). In the distributive-effects sentences, we mentally represent the same label attached to multiple bottles.

The research mentioned above argued that the number of the local NP impacts subject–verb agreement, based on the results of oral sentence completion tasks, where the participants were provided a subject NP (the label on the bottle/bottles) and asked to complete the sentence. If the participants mistakenly produced plural verbs even with a singular head NP, it was concluded that they were distracted by conceptual number (e.g., Bock & Miller, Reference Bock and Miller1991; Eberhard, Reference Eberhard1999).

Other research has investigated the representation of plural nouns’ constituents. Kaup, Kelter, and Habel (Reference Kaup, Kelter and Habel2002) investigated whether native English speakers differentiated plural sets from their own members, presenting sentences like John and Mary went shopping with two alternative accompanying sentences, (a) Both bought a gift, and (b) They bought a gift. Participants were asked to answer the question, How many gifts did John and Mary buy? The results showed that when the subject was both (as in [a]), participants tended to answer that two gifts were bought, indicating that John and Mary were represented as constituents of a plural set, a so-called complex reference object. In contrast, for (b), participants more often answered that only one gift was bought, suggesting that John and Mary were represented as a group. Thus, the human language processor is sensitive to whether individuals in the plural sets are mentioned explicitly or vaguely. This prediction has also been supported by other L1 psycholinguistic research (e.g., Patson & Ferreira, Reference Patson and Ferreira2009; Patson et al., Reference Patson, George and Warren2014; Patson & Warren, Reference Patson and Warren2011). In eye-tracking experiments, Patson and Ferreira (Reference Patson and Ferreira2009) found that only coordinated NPs (e.g., the man and the woman) can block garden-path effects ([3a]–[3c]); neither plural definite descriptions (PDDs; e.g., the lovers) nor numerically quantified plurals (e.g., the two cats) were represented as complex reference objects, but coordinated NPs were. Because, in coordinated NPs, the constituents of plural nouns are easily accessible, the parsing system easily construes the reciprocity and avoids assigning an object role to the NP following the reciprocal verb.

(3) a. Soon after the singer and the model met the director cast them in his movie.

b. Soon after the models met the director cast them in his movie.

c. Soon after the two models met the director cast them in his movie.

Patson and Ferreira (Reference Patson and Ferreira2009) also found that no blocking effect is observed when the first verb of the sentences is optionally transitive, even if the subject of the optionally transitive verb is coordinated. Patson and Ferreira revealed further that clearly differentiating the characteristics of the individuals in plural sets is critical to conceptually representing those complex reference objects.

The studies reviewed above give evidence that not only linguistic but also conceptual information derived from linguistic representations impacts L1 sentence processing. More recently, L2 researchers have also started to investigate whether L2 speakers process conceptual number information in terms of distributive effects, as we will review in the next section.

Conceptual plurality in L2 research

Though few L2 studies have investigated conceptual number information in sentence processing, some research has looked at whether distributive effects are observed by L2 speakers (e.g., Foote, Reference Foote2010; Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010; Nicol & Greth, Reference Nicol and Greth2003; Nicol et al., Reference Nicol, Teller and Greth2001; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Chen, Liang and Dunlap2015). These studies have considered three main questions: whether distributive effects are found in sentence production by L2 speakers and if so how they resemble/differ from those in L1 (Foote, Reference Foote2010; Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010; Nicol & Greth, Reference Nicol and Greth2003; Nicol et al., Reference Nicol, Teller and Greth2001); whether age of acquisition or proficiency level influence the magnitude of distributive effects (Foote, Reference Foote2010; Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Mormer and Brehm2018); and whether L1 background plays a role in distributive effects in L2 (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Mormer and Brehm2018; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Chen, Liang and Dunlap2015).

Regarding the first question, Nicol et al. (Reference Nicol, Teller and Greth2001) found distributive effects in both Spanish–English and English–Spanish bilinguals, to a similar extent as in Spanish and English native speakers. Moreover, Nicol and Greth (Reference Nicol and Greth2003) investigated distributive effects in English–Spanish bilinguals and found distributive effects similar in magnitude across L1 and L2.

Foote (Reference Foote2010) also investigated distributive effects in Spanish–English and English–Spanish bilinguals of intermediate and advanced levels, taking into account the second issue, age of acquisition and proficiency. Foote (Reference Foote2010) found that, overall, all the groups demonstrated notional number attraction effects, which, however, differed in magnitude across the groups: they were larger in early bilinguals than late bilinguals, larger in intermediate than advanced group, and larger in English than Spanish. The overall tendency was consistent across English–Spanish and Spanish–English bilinguals. One exception was that the intermediate group who started learning the L2 late demonstrated larger distributive effects in Spanish than in English. Foote tentatively concluded that this “less attraction effect” for the late-intermediate group implied that English–Spanish bilinguals were not able to make use of Spanish number morphology to overwrite the mismatching notional number in the demanding online task. As a result, the rate of erroneous agreement in Spanish was a little higher than in English for only the late-intermediate group, contrasting the overall tendency.

Similar to Foote (Reference Foote2010), Hoshino et al. (Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010) also investigated how proficiency influences sensitivity to conceptual and grammatical number agreement, adapting the L1 model of Hartsuiker and Barkhuysen (Reference Hartsuiker and Barkhuysen2006) to an L2 context. In an L1 context, Hartsuiker and Barkhuysen had investigated the basic effect of cognitive demand on this sensitivity to distributive effects, finding that although number mapping from conceptual to functional representation in the first stage of agreement (the “marking process” per Eberhard, Cutting, & Bock, Reference Eberhard, Cutting and Bock2005) is less affected by cognitive resource limitations, the second stage of agreement, where the language processor resolves number feature conflict between the head NP and local NP (the “morphing process” in Eberhard et al.’s, 2005, term) and is more affected by cognitive resource limitations. Hoshino et al. (Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010) then operationalized cognitive demand in terms of language proficiency (high or low), and found that highly proficient Spanish–English bilinguals were sensitive to both grammatical and conceptual number agreement in both L1 and L2, whereas the low proficiency group were sensitive to only grammatical number agreement in L2 (but to both types in L1). On this basis, Hoshino et al. (Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010) argued that sufficient cognitive resources to maintain conceptual number information were required to check number agreement in the second stage. Similarly, Hoshino, Kroll, and Dussias (Reference Hoshino, Kroll and Dussias2012) did not find distributive effects in Japanese learners of English as a foreign language (EFL), who were less proficient than the Spanish–English bilinguals in Hoshino et al. (Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010) but who might have shown sensitivity to conceptual information if they were as proficient as that group. The results of Hoshino et al. (Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010, Reference Hoshino, Kroll and Dussias2012) conflict with those of Foote (Reference Foote2010), because Foote found a small but significant distributive effect even for less proficient bilinguals. Wei et al. (Reference Wei, Chen, Liang and Dunlap2015) explained that these contradictory results may be related to the presence of pictures during the task (as in Foote, Reference Foote2010) versus their absence (as in Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010). Wei et al. (Reference Wei, Chen, Liang and Dunlap2015) also confirmed that distributive effects in production were rare if learners’ L1 did not have a subject–verb agreement system, as in the case of Chinese–English bilinguals; however, showing pictures eased the Chinese–English bilinguals of this cognitive load in L2 production, leading to distributive effects.

All the research on conceptual number representation in L2 speakers reviewed above applied distributive effects, in which sentence fragments (e.g., the label on the bottles) were presented and participants were asked to complete the sentence. As recent L1 research (e.g., Patson & Ferreira, Reference Patson and Ferreira2009; Patson et al., Reference Patson, George and Warren2014; Patson & Warren, Reference Patson and Warren2010) has developed a variety of methodologies to examine the conceptual representation of number apart from number agreement, L2 studies should also focus not only upon distributive effects but also upon other linguistic features; among these, we focused on reciprocal verbs.

As mentioned above, reciprocal verbs have an interesting characteristic: their interpretation is influenced by the number of people involved in the action. In the following section, we will review the characteristics of reciprocal verbs in detail to help us consider the conceptual representation of plurality.

Reciprocal verbs and plurality

As noted above, a reciprocal verb means the denoted event is pluralized. Like many other languages, Japanese, the first language of the present study’s participants, features reciprocals. The most relevant one to the discussion of the present study is Japanese suffix –aw. Once –aw attaches to a verb, it introduces a reciprocal reading, as shown in (4).

(4) a. kodomo-tachi-ga rouka-de hanashi-teiru

(The) child-tachi[pl]-ga[NOM] the hallway-de[LOC] talk-teiru[PROG]

:(The) children are talking in the hallway.”

b. kodomo-tachi-ga rouka-de hanashi-at-teiru[PROG]

(The) child-tachi[pl]-ga[NOM] the hallway-de[LOC] talk-aw-teiru[PROG]

“(The) children are talking to each other in the hallway.”

Though (4a) might imply a reciprocal reading, (4b) clearly conveys that the children are talking “to each other.” Conversely, (4a) could be interpreted that more than one child is talking to somebody, possibly on the phone, whereas (4b) does not allow this interpretation.

Reciprocal reading requires two or more people to be involved in the action denoted by the main verb. Because Japanese does not have an obligatory plural suffix as English does, the sentences in ([4a] and [4b]) can be rendered without the Japanese plural marker –tachi ([5a] and [5b]).

(5) a. kodomo-ga rouka-de hanashi-teiru

(The) child/children-ga[NOM] the hallway-de[LOC] talk-teiru[PROG]

“(The) child/children is/are talking in the hallway.”

b. kodomo-ga rouka-de hanashi-at-teiru[PROG]

(The) *child/children-ga[NOM] the hallway-de[LOC] talk-aw-teiru[PROG]

“(The) *child/children is/are talking to each other in the hallway.”

Without –tachi, the discrepancy between (5a) and (5b) becomes clearer. In (5a), it is unclear whether one child is talking to somebody who does not appear in the sentence, or more than one child is talking to somebody independently, or more than one child is talking to other children in the same group (the reciprocal interpretation). In contrast, with the suffix –aw attached to hanasu “talk” in (5b), only the reciprocal interpretation is allowed, entailing that kodomo carries plurality despite the lack of plural marker –tachi, that is, kodomo is grammatically singular but conceptually plural (see Nakanishi & Tomioka, Reference Nakanishi and Tomioka2004, on the use of –tachi with proper nouns). Thus, –aw requires the subject to be plural, but this plurality does not have to be marked grammatically.

As these examples demonstrate, –aw introduces a reciprocal reading and, more important, enables an unmarked singular NP to be conceptually plural. When we consider the characteristics of reciprocal verbs and reciprocal sentences in English, it emerges that the prerequisite of an NP’s being the subject of a reciprocal sentence is conceptual, but not necessarily grammatical, plurality.

Fiengo and Lasnik (Reference Fiengo and Lasnik1973) argued that not grammatical plurality, but semantic, or in our terms conceptual, plurality is what makes sentences reciprocal. As we discussed above, conceptual and grammatical number are sometimes in conflict in English, for instance in so-called pluralia tantum (e.g., scissors, pants, and binoculars), as in (6).

(6) a. The binoculars are on the table.

b. *The binoculars are focused differently from each other (one pair).

(Fiengo & Lasnik, Reference Fiengo and Lasnik1973, p. 452)

The reason (6b) is ungrammatical is that each other cannot be in anaphoric relationship with a conceptually singular NP. A similar claim was made by Gleitman et al. (Reference Gleitman, Gleitman, Miller and Ostrin1996), who argued that a lexical–semantic property of reciprocal verbs, rather than syntactic verb subcategorization information, requires conceptual plurality of subject NPs. (Verb subcategorization information is information about the argument structures a verb can take. For example, the English verb talk cannot take a person as a direct object [e.g., *he talked you last night], but ask can [e.g., he asked you last night].) According to Gleitman et al. (Reference Gleitman, Gleitman, Miller and Ostrin1996), this is why reciprocal verbs can be used with grammatically singular but conceptually plural collective nouns (e.g., the group meets).Footnote 1 Gleitman et al. conclude that oddity in singular NP–reciprocal verb combinations is not a matter of grammar but of the semantic properties of the sentence.

In summary, reciprocal verbs require plurality from subject NPs. If the subject NP is singular, the object NP(s) must necessarily follow the verb to make the sentence grammatical (e.g., *Bob met vs. Bob met Mary), and the verb is no longer called reciprocal because there is no reciprocal reading available. Plurality here is not a grammatical property but a conceptual one; thus, how speakers conceptually represent the number information of an NP is crucial in deciding whether reciprocity is derived. This is why investigating reciprocal verbs has potential implications for L2 learners’ representation and processing of conceptual number information.

Purpose of the present study

As reviewed above, although how L1 and L2 speakers conceptually represent number information in sentence processing has interested many researchers, L2 research has focused almost exclusively on number agreement. Previous studies revealed that L2 speakers processing for number agreement are less likely to be affected by conceptual number than L1 speakers are unless they are highly proficient in the L2 (Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010) or their L1 has a number agreement system (Wei et al., Reference Wei, Chen, Liang and Dunlap2015). However, the role of conceptual plurality may vary depending on the type of conceptual plurality, for example, conceptual plurality present in collective nouns versus conceptual plurality derived from distributive effects (e.g., see Kusanagi, Tamura, & Fukuta, Reference Kusanagi, Tamura and Fukuta2015, for the case of collective nouns). The difference between a conceptual number derived from collective nouns and one derived from distributive effects can be explained according to whether the constituents of the plural object are fully specified or unspecified. Our focus here was the former (see Patson, Reference Patson2014, for a comprehensive review of plurality).

Missing in L2 studies are (a) the application of a comprehension task as in recent L1 studies, and (b) investigation of conceptual plurality apart from number agreement. Of course, number agreement remains an interesting linguistic phenomenon, because speakers use both grammatical and conceptual information, which interface in distributive effects, in making number agreement. However, focusing on this phenomenon risks missing the broader picture. Focusing on processing of reciprocal verbs, in which conceptual number is inevitably involved in reaching a final interpretation, will broaden our understanding of how L2 learners represent conceptual number information and will move the field forward.

METHOD

The research question taken up by this study was as follows: are Japanese EFL learners able to use conceptual plural information during online sentence processing? To answer this research question, we examined the processing of reciprocal verbs.

Following the idea proposed by Ferreira and McClure (Reference Ferreira and McClure1997), Patson and Ferreira (Reference Patson and Ferreira2009) investigated whether reciprocal verbs with conjoined NPs enabled native speakers of English to evade garden-path effects, by comparing the reading time of four types of sentences, shown below.

(7) a. While the lifeguard and the swimming instructor embraced the child fell into the pool.

b. While the lifeguards embraced the child fell into the pool.

c. While the lifeguard and the swimming instructor trained the child fell into the pool.

d. While the lifeguards trained the child fell into the pool.

In ([7a] and [7b]), the verbs in the subordinate clauses are reciprocal verbs involving two or more people, and therefore, if the subject of the sentence carries plurality, they are used like transitive verbs. As discussed above, the plurality in this case is conceptual, not grammatical.

When we look at (7a), the reciprocal verb embraced has a conjoined NP as its subject, and therefore, the following noun, the child, should be less likely processed as the direct object of embraced. If so, no garden-path effects should be found in (7a). In (7c), by contrast, the verb trained in the subordinate clause is an optionally transitive verb (OT verb), which can be interpreted either transitively or intransitively irrespective of the subject’s number information. As a result, the child is more likely to be considered the direct object of the verb trained. The question is whether the same thing happens if the subject is a plural definite NP, like in ([7b] and [7d]), which also has plurality, but the constituent of the plural nouns (i.e., the exact number of lifeguards) is ambiguous compared to the case of a conjoined NP. Patson and Ferreira (Reference Patson and Ferreira2009) found that even L1 English speakers tended to be trapped in garden-path sentences like ([7b]–[7d]) whereas they did not in (7a); thus, Patson and Ferreira concluded that what made readers avoid the pitfalls of garden-path sentences was not the main effect of either the conjoined NP or the reciprocal verb but the interaction between them. Following this line, we also considered the type of noun (plural definite NP or conjoined NP) in our experiments. However, we did not include a singular subject NP condition because if the subject NP is singular, the sentence becomes ungrammatical (e.g., *the lifeguard embraced the child fell into the pool).

As our participants were Japanese EFL learners, we confirmed that they understood the characteristics of reciprocal verbs, using a written sentence completion task (SCT) and a self-paced reading task (SPRT).

The experiments’ possible outcomes should be interpreted as follows. In the SCT, if participants would tend to produce few direct objects of reciprocal verbs in subordinate clauses, it would suggest that they know reciprocal verbs do not need a direct object if the subject NP carries plurality. In the SPRT, if participants read sentences with reciprocal verbs faster than those with OT verbs at and after they encountered the verb of the main clause, it would mean that they used the conceptual number information of the subject NP to interpret the NP right after the reciprocal verb as the subject of the main clause. Furthermore, the speed of processing was expected to differ depending on the type of subject NP (conjoined or PDD) because the conjoined NP more clearly denotes the constituent of the plural set.

Participants

Thirty-two Japanese learners of English participated in this study. They were either undergraduate (n=6) or graduate students (n=26) in Japanese universities, from various majors. Four participants were removed because their English proficiency was found too low to engage in the SPRT. Fifty-eight percent of the participants had some experience living in English-speaking countries, for between 2 weeks and 54 months. Most had studied English since they were freshmen in junior high school, and some had also experienced weekly English language lessons in the fifth and sixth years of elementary school. The participants were considered relatively proficient EFL learners, with mean TOEIC score of 854.46 (SD=82.58) / 990, roughly equivalent to B2 level on the Common European Framework Reference for Languages. They agreed to participate, receiving compensation of 1,000 Japanese yen. Detailed demographic information on participants, including self-reported English proficiency, is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Demographic information of the participants

Note: Starting age of learning English was calculated by subtracting the years of learning English from the age. One participant did not report his age, so his starting age could not be calculated. The self-reported proficiency scale was measured by a 5-point Likert scale. a n=28. b n=27. c n=18.

Materials and procedures

This section discusses the materials used in the experiment as well as the procedure of the experiment. The experimental materials used in the SPRT will be described first because the materials of the SCT were based on these used in the SPRT. Note that in the Analysis, Result, and Discussion sections, the SCT will always be discussed first because all the participants completed the SCT first and the SPRT afterward.

SPRT

Twenty test items were developed, each of which appeared in four different conditions ([8a]–[8d]). In (8a) and (8c), the subject NP in a dependent clause was a conjoined NP, followed by either a reciprocal verb (8a) or an OT verb (8c). In contrast, the subject NP in the dependent clause in (8b) and (8d) was a PDD followed by either a reciprocal verb (8b) or an OT verb (8d).

(8) a. As the mother and the father battled the child played the guitar in the room (Conj/recip)

b. As the parents battled the child played the guitar in the room. (PDD/recip)

c. As the mother and the father left the child played the guitar in the room. (Conj/OT)

d. As the parents left the child played the guitar in the room. (PDD/OT)

The 10 reciprocal verbs and 10 OT verbs presented in Table 2 were used as test items, following Patson and Ferreira (Reference Patson and Ferreira2009).Footnote 2 Although we referred to the test items made by Patson and Ferreira (Reference Patson and Ferreira2009), we did not use words that are often unfamiliar to EFL learners. The examples of those words were salute, snuggle, and cuddle. In addition, the sentence structure was also controlled for so that all the target verbs were followed by a determiner, a noun, and a prepositional phrase.

Table 2 The list of reciprocal verbs and optionally transitive verbs used in the experiment

In addition, 5 conjunctions (when, while, as, after, and because) were distributed equally among the test items, along with 68 distractors (the test items are provided in Appendix A). Some of the distractor items were such as they had to teach the employees Chinese before sending them to China. The participants were asked to answer a comprehension question (e.g., Were the employees to be sent to China?) after reading the distractor. Both examples presented here were taken from Jiang (Reference Jiang2007). Participants were randomly assigned one of the four lists, meaning participants in different conditions did not see the same test items.

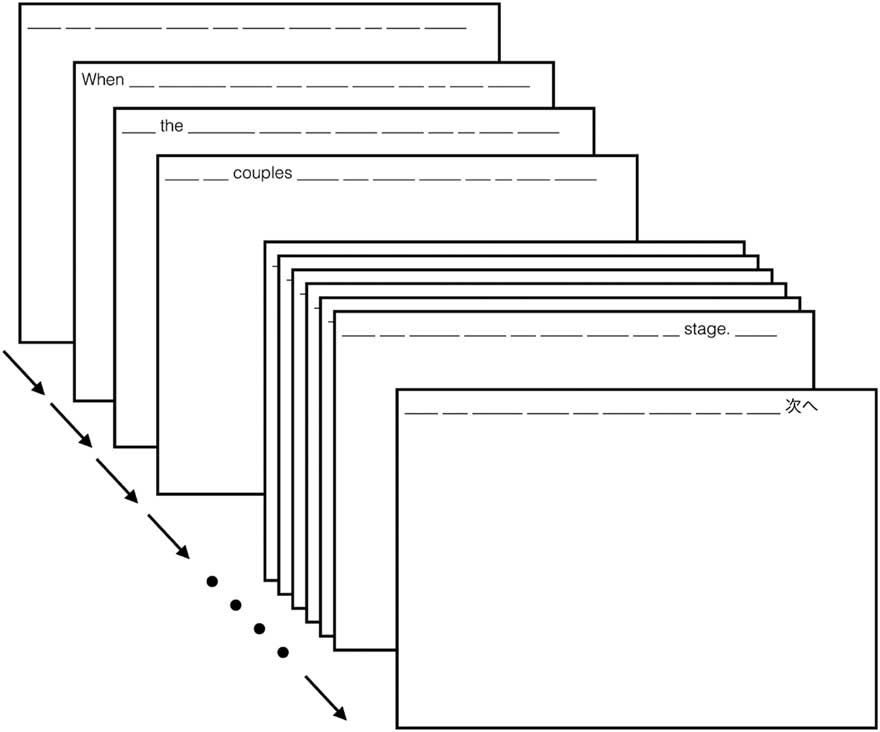

The SPRT was developed using Hot Soup Processor version 3.2., which is a programming language freely available from http://hsp.tv/; it was conducted individually, in a quiet room. Participants were asked to read a sentence randomly presented on a computer screen (Figure 1). Target sentences were presented in a moving-window style: participants read the sentence word by word, moving to a new word by pressing a key. Though distracter items were followed by yes/no comprehension questions, no legitimate test items were followed by comprehension questions. Mean accuracy for comprehension questions was 85.7% (SD = 7.0%), or good to fair. To avoid fatigue effects, the 88 items (including distracters) were presented in two sessions; session order was counterbalanced on each of the four lists. The entire experiment, including the background questionnaire and an offline sentence completion task, took 1 hr.

Figure 1 Schematic of the self-paced reading experiment. In order to avoid the wrap-up effect, the last region included the Japanese translation of “going to the next.” In the analysis, this last region was excluded in calculating mean reading time of the participants.

SCT

This task had two objectives: first, to ensure that participants could interpret reciprocal readings; and second, to ensure that participants did not show any preference for transitive or intransitive interpretation of OT verbs. On the first point, if participants did not know that a reciprocal verb does not require an object noun if the subject noun carries plurality, they would be less likely to avoid the garden-path effect. Thus, it was necessary to verify that participants understood the argument structure of reciprocal verbs and could attend to reciprocal readings; if so, we could safely conclude that if there was no difference in reading time (RT) latencies between reciprocal verbs with a conjoined NP subject and OT verbs with a conjoined NP subject in the SPRT, this was because participants were able to assign both agent and patient roles to the subject NP, avoiding the garden-path effect.

As for the second point, the aim in comparing reciprocal and OT verbs in the SPRT was to confirm that what blocks the garden-path effect is not transitivity but reciprocity. However, certain combinations of subject nouns and OT verbs may more likely lead to either transitive or intransitive interpretations. If so, this bias would affect online processing during self-paced reading, and thus verbs biased toward intransitive interpretation would likely block the garden-path effect. Therefore, we needed to ensure that participants processed OT verbs to the same extent as transitive and intransitive ones.

After the SPRT, participants tackled the SCT. They completed printed sentences ([9a]–[9d]), using the same items as in the SPRT.

(9) a. When the artist and the painter hugged______________________________

b. When the artists hugged_________________________________________

c. When the artist and the painter wrote_______________________________

d. When the artists wrote__________________________________________

The same item list, comprising 20 sentences but without distracters, was used.Footnote 3 Each participant was assigned a different list from the one he or she had had in the SPRT, and thus did not see exactly the same sentences seen while doing the SPRT, avoiding the possibility of memorizing sentences. In addition, each list contained the same number of test items across all four conditions, and thus, there was no serious danger that the participants’ responses to the SCT would be influenced by the fact that they completed the SPRT just beforehand.

One may wonder why the combination of singular NPs and reciprocal verbs were not tested in the SCT as well as in the SPRT, because it seems critical to demonstrate that the participants would show higher transitivity bias for reciprocal verbs with a singular subject than for those with a conjoined subject NP to determine whether they appreciate reciprocal readings or not. However, “reciprocal meaning” does not derive from a singular subject, given that reciprocity necessarily involves two (or more) people involved in the action denoted by the verb and that those people should be both agent and patient of the action. Thus, the only way to prove whether the participants appreciate reciprocal readings is to have them process the combination of plural subject NP and reciprocal verb and to investigate whether they add an object NP after the reciprocal verb. If they add an object NP, it means they do not read the sentence reciprocally but rather transitively. If not, it means they interpret the sentence reciprocally.

Analysis

SCT

The SCT responses were analyzed as follows. First, if the sentences were not complete, complex sentences, the responses were categorized as errors. If the participants seemed confused about whether to interpret the verb transitively or intransitively, those responses were also coded as errors (e.g., *after the leaders kissed to their children, they went to the battlefield as a national army). In this example, kissed is used intransitively although it should have been transitive (e.g., after the leaders kissed their children …), which causes ungrammaticality. Second, how the verb in the subordinate clause was interpreted was coded as a transitive, intransitive, or reciprocal reading. If the OT verb was followed by a direct object, the responses were coded as transitive; for responses to be coded as intransitive, the OT verb had to proceed to a prepositional phrase or a comma. If no direct object followed or each other followed, those responses were coded as reciprocal readings. In addition, if adjuncts followed the reciprocal verbs (e.g., as the mother and the father battled in the house ….), these responses were also coded as reciprocal readings. In contrast, if the post-\verbal prepositional phrases did not refer to the person involved in the denoted action (e.g., because the coach and the trainer argued about the methods of training ….), these responses were coded as intransitive. If the reciprocal verbs took direct objects (e.g., As the waiters met their friends in the café …), these were coded as transitive. Any grammatical errors or mistakes which were not relevant to the coding, such as morphosyntactic errors or spelling mistakes, were ignored. Coding examples are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3 Examples of coding in the sentence completion task

To see the differences in proportions, Poisson log-linear analyses were performed on the reciprocal verb items and OT verb items, respectively, using R 3.3.0 (R Core Team, 2016). As no reciprocal reading was permitted for the sentences with OT verbs, the matrix was constructed as 2 (levels of noun type; reciprocal or PDD)×2 (levels of interpretation type; intransitive or transitive) for OT verbs. In contrast, reciprocal verbs can be interpreted in three ways, reciprocally, transitively, or intransitively, and therefore, a 2 (reciprocal or PDD)×3 (reciprocal, transitive, or intransitive) matrix was used. It should be noted that the error rate differed across each condition, leading the sum frequency to differ also. To control the discrepancies, we added log-transformed total number of observations as an offset term of the Poisson log-linear model. The two categorical variables were contrast coded to avoid serious multicollinearity; if there was an interaction between the two factors, we proceeded to multiple comparison using the lsmeans package (Lenth, Reference Lenth2016).

SPRT

As for the analysis of the SPRT, RT was analyzed in the target region, that is, the region where the participant encountered the target verb (reciprocal or OT), as well as in the two regions that followed it, in which the participants read the direct object of the target verb, to consider delayed effects; finally, one word before the target verb was also analyzed. The reason why we looked at the word before the target verb was to make sure that no RT difference was observed across the four conditions. It did not tell us anything about the conceptual plurality, and to understand the results of the SPRT correctly, we should examine the delay observed after the target verb was due to the garden-path effect. The analysis of RT was conducted as follows. We divided the RT data into four conditions ([8a]–[8d]) and calculated the mean and standard deviation of each participant’s RT in all regions. We considered responses below and above M+/–3 SD as outliers and removed them from further analysis. Responses below 200 ms were also regarded as outliers, because word recognition and processing of word meaning are not likely to occur below 200 ms. Overall, 4.5% of the responses were removed as outliers.

After removing all the outliers, a series of generalized mixed-effects models (GLMMs) were applied using R 3.3.0 (R Core Team, 2016) and the lme4 package (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015), so as to see the effects of the following three explanatory variables; type of verb (reciprocal or OT), type of NP (conjoined or PDD), and an interaction term between these two variables. In addition, the participant’s English proficiency (TOEIC score) and word length for each region were added as covariates, although the latter was not added to the model for the region of one word after the target verb region because in all the conditions, the word length was three (the). To avoid convergence issues, TOEIC score was scaled before being entered into the model. A GLMM with cross-random effects (subject and item) was fitted with raw RT data as a response variable. The gamma distribution with identity link function was adopted on the presumption that the response variable (raw RT) fits gamma distribution because it is a continuous variable whose parameters are greater than zero (Lo & Andrews, Reference Lo and Andrews2015). Note that both exploratory variables were contrast coded (verb type: –.5=OT, .5=reciprocal; noun type: –.5=PDD, .5=conjoined), in accordance with Linck and Cunnings’s (Reference Linck and Cunnings2015) recommendation.

Similar to traditional multiple regression, GLMM is also in danger of multicollinearity if the correlation between the explanatory variables is high. Thus, we checked variance inflation factor for the best models in each region to make sure that no serious multicollinearity was found (See the online-only Supplementary Materials for details).

If the GLMM analyses found an interaction between the type of nouns and verbs, we examined the simple main effects of both variables using the lsmeans package (Lenth, Reference Lenth2016).

RESULTS

SCT

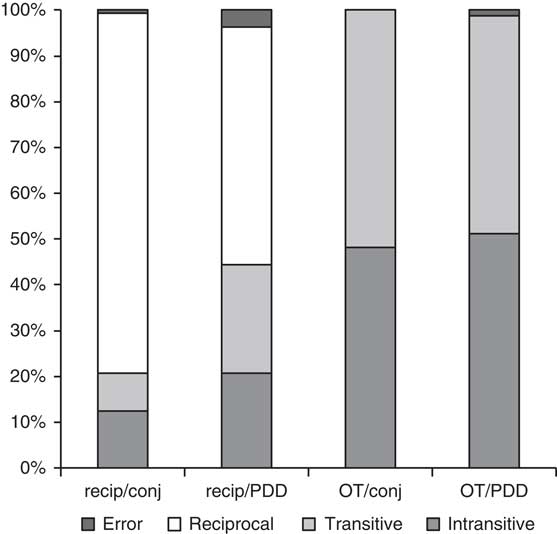

Table 4 breaks down by frequency the interpretations of the verbs in the four conditions, and Figure 2 graphically demonstrates their proportions. As can be seen, whether the subject was a conjoined NP or a PDD, OT verbs were construed transitively or intransitively to the same degree. Thus, the participants did not have any preference regarding the target OT verbs used in the experiment. The result of log-linear analysis confirmed this tendency: there was no main effect of noun type (Estimate=0.075, SE=0.159, z=0.476, p=.634) or of verb category (Estimate < 0.001, SE=0.112, z=–0.004, p=.997); nor was there any interaction between the two factors (Estimate=–0.151, SE=0.224, z=–0.673, p=.501). The results were also confirmed by stepwise backward model selection based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The best model chosen was a null model that included neither the main effect of the type of noun nor the main effect of the coded verb category (see the online-only Supplementary Materials for further information).

Figure 2 The proportion of the interpretation of the verb in the sentence completion task. Conj, conjoined NPs; PDD, plural definite descriptions; recip, reciprocal verbs; OT, optionally transitive verbs.

Table 4 Proportion of verb interpretations in the sentence completion task (percentage in parentheses)

Note: Conj, conjoined NPs. PDD, plural definite descriptions. OT, optionally transitive verbs.

Looking at the reciprocal verbs, we see that they were more likely to be read reciprocally than either transitively or intransitively. However, the proportion of reciprocal readings appeared to be influenced by the type of subject NP: if the subject NP was conjoined, the participants were more likely to prefer a reciprocal reading. This observation was confirmed by the log-linear analysis. The best model chosen by stepwise backward selection contained the interaction between the noun type and verb category, suggesting that frequency differences between some combination of noun type and verb type (e.g., conjoined NP with transitive verb, PDD with intransitive verb, etc.) do exist.

To examine these frequency differences, multiple comparisons were carried out. Their results showed that when the subject was a conjoined NP, participants produced more reciprocal than intransitive verbs (Estimate=–1.841, SE=0.241, z=–7.647, p<.001) and also more reciprocal than transitive verbs (Estimate=2.271, SE=0.291, z=7.797, p<.001); however, there was no frequency difference between intransitive and transitive verbs (Estimate=0.431, SE=0.356, z=1.209, p=.448). Similarly, when a plural definite noun stood as the subject, the participants produced more reciprocal than intransitive verbs (Estimate=–0.892, SE=0.204, z=–4.383, p<.001) and more reciprocal than transitive verbs (Estimate=0.781, SE=0.196, z=3.989, p<.001).

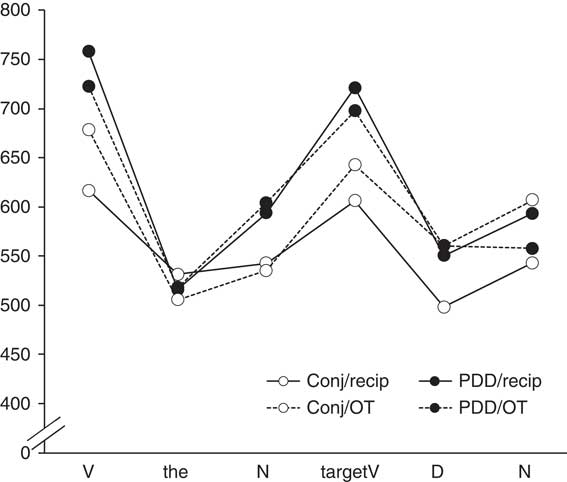

SPRT

Table 5 summarizes the mean and standard deviation of RTs for each condition, and Figure 3 is a graphical representation of mean RT profile. As mentioned above, GLMM was carried out in four critical regions. Because our focus was an interaction term between type of noun and type of verb, we developed a model including both of these variables and the interaction term. We also added TOEIC score, which was z-transformed, as a covariate, to control the effect of proficiency differences.

Figure 3 Mean reading time profile in all the four conditions. Conj, conjoined NPs; PDD, plural definite descriptions; recip, reciprocal verbs; OT, optionally transitive verbs.

Table 5 Mean RTs (ms) and SDs (in parentheses) in the self-paced reading task

Note: Conj, conjoined NPs. PDD, plural definite descriptions. Recip, reciprocal verbs. OT, optionally transitive verbs.

For each region, the random effect structures were decided as follows. First, a model with maximal random structures (i.e., with all the slopes and intercepts of all the explanatory variables) was developed. Second, we removed random slopes one by one and developed several models with simpler random structures. Third, we compared the AICs of all the converged models and chose the model with the lowest AIC (see the online-only Supplementary Materials for detailed information on each model). Note that in the target verb region, the two models produced almost exactly the same AIC (6934.074 and 6934.137); therefore, in this region, we also checked the Bayesian information criterion, and selected the model with the lower Bayesian information criterion.

The best model as justified by AIC in the region of one word before the target verb region demonstrates that there is an interaction between the type of noun and the type of verb (Table 6). A simple main effects test revealed that sentences including conjoined NPs and OT verbs were read faster than those with PDDs and OT verbs (Estimate=–76.179, SE=24.403, z=–3.122, p=.002). No other comparison reached statistical significance, although RT differences between the combination of conjoined NPs and OT verbs and that of conjoined NPs and reciprocal verbs were close to the significance threshold (Estimate=–34.013, SE=18.344, z=–1.854, p=.064; see the online-only Supplementary Materials for the complete tables of the simple main effects test).

Table 6 Results from GLMM in the one word before Target V region

Note: Number of observation = 536, N=28, K=20. Model formula: RT ~ Noun +Verb + Noun : Verb + TOEIC + Word Length + (1+Noun | Subject)+(1 | Item).

Table 7 is a summary of the best model in the target verb region. In this region, main effects of both noun type (Estimate=56.606, SE=17.138, t=3.303, p<.001) and verb type (Estimate=–32.914, SE=16.057, t=–2.050, p=.040) were found; however, there was no significant interaction between them (Estimate=–8.381, SE=26.478, t=–0.317, p=.752).

Table 7 Results from GLMM in the Target V region

Note: Number of observation = 501, N=28, K=20. Model formula: RT ~ Noun + Verb + Noun : Verb +TOEIC + Word Length + (1 | Subject)+(1 | Item).

Table 8 summarizes the results of GLMM in the next region, one word after the target verb. In this region, there was a main effect of verb type (Estimate=–57.874, SE=26.830, t=–2.157, p=.031), but neither the main effect of noun type nor the interaction term was significant (noun type: Estimate=40.381, SE=32.719, t=1.234, p=.217; interaction: Estimate=21.785, SE=26.528, t=0.821, p=.412).

Table 8 Results from GLMM in Region D

Note: Number of observation = 547, N=28, K=20. Model formula: RT ~ Noun + Verb + Noun : Verb + TOEIC + (1+Noun + Verb | Subject)+(1 | Item).

The model selected based on the AIC in the last region of interest, two words after the target verb, confirmed that no main effect of either noun type or verb type was found (noun type: Estimate=19.43, SE=17.48, t=1.111, p=.266; verb type: Estimate=–21.84, SE=18.87, t=–1.157, p=.247). However, there was a significant interaction between the two variables (Estimate=45.13, SE=22.57, t=2.000, p=.046). Table 9 summarizes the results of GLMM in the region two words after the target verb.

Table 9 Results from GLMM in Region N

Note: Number of observation = 532, N=28, K=20. Model formula: RT ~ Noun + Verb + Noun : Verb + TOEIC + Word Length + (1+Verb + TOEIC + Word Length | Subject)+(1+Verb | Item).

A simple main effects test further revealed that if the verb in the subordinate clause was reciprocal, sentences in which a conjoined NP served as subject were processed faster than those with a plural definite noun as subject (Estimate=–33.710, SE=16.409, z=–2.054, p=.040), whereas no RT difference resulting from subject noun type was found when the verb was OT (Estimate=2.688, SE=15.877, z=0.169, p=.866). Looking at the simple main effect of verb type, conjoined NPs with reciprocal verbs were read faster than those with OT verbs (Estimate=49.939, SE=23.768, z=2.101, p=.036); in contrast, no RT difference was found between plural definite nouns with OT verbs and those with reciprocal verbs (Estimate=13.541, SE=24.164, z=0.560, p=.575). Figure 4 graphically represents the interaction between type of noun and type of verb.

Figure 4 Interaction plot of the reading time in the last interested region of the self-paced reading task. The black lines indicate optionally transitive verbs and gray lines indicate reciprocal verbs.

To control the possible effect of English language proficiency, TOEIC score was added to GLMM models in all the regions of interest; however, the main effects of the TOEIC score did not reach statistically significant levels in any of the regions, which implied that English language proficiency did not have much impact on the variance of the RT latencies.

DISCUSSION

Findings of the present study

SCT

We analyzed the data obtained through the SCT to confirm that the participants did not show any bias in the interpretation of OT verbs. The results suggested that the OT verbs used in this study successfully induced transitive interpretations to the same extent as intransitive interpretations, meaning that participants demonstrated no bias in the interpretation of OT verbs regardless of whether the subject was a conjoined NP or a plural definite description.

Another objective of the SCT was to show the participants capable of reciprocal readings, in which the subjects of the reciprocal verb play both agent and patient roles in the action denoted by the verb. The results of the SCT in reciprocal verb conditions show that whether the subject noun type was conjoined or a PDD, the participants interpreted the sentences reciprocally much more frequently than intransitively or transitively. However, the type of noun did influence the likelihood of reciprocal reading: participants were more inclined to read reciprocally when the subject was conjoined than when the subject was a plural definite noun. This might indicate that a conjoined NP is more likely to induce reciprocal reading.

SPRT

To summarize the results of the SPRT, in the first region of interest, sentences with OT verbs and conjoined NPs were unexpectedly read faster than those with PDDs, but there was no significant RT difference between OT verbs with conjoined NPs and reciprocal verbs with conjoined NPs.Footnote 4 Nonetheless, the expected RT differences were observed in the target verb region: sentences with reciprocal verbs were read faster than those with OT verbs in both the conjoined NP and PDD conditions, although the main effect of noun type indicated that irrespective of verb type, the sentences with conjoined NPs were read faster than those with PDDs. This indicates the possibility that if the subject is a PDD, learners might have difficulty inducing reciprocal interpretation. In the region covering the one word after the target region, the main effect of noun type disappeared, but the main effect of verb type persisted, suggesting that RT delay was observed only in the OT verb sentences. However, in the next region, two words after the target verb region, the RT trend changed: the participants read fastest in the conjoined NP with reciprocal verb condition, and the PDD with reciprocal verb condition was no longer read faster than the OT verb conditions.

Processing and representation of plurality

Our research question was “Are Japanese EFL learners able to use conceptual plural information during online sentence processing?” The evidence presented here suggests that the answer is yes. Before discussing this in more detail, let us consider the results of the SCT, which confirmed that the participants possessed the knowledge that reciprocal verbs do not need a direct object if the number feature of the subject carries plurality. This result allowed us to conclude that if the processing tendency in the SPRT was to differ depending on verb type, it had to result from the characteristics of the reciprocal verb. Sentences with reciprocal verbs were read faster than those with OT verbs. This result is to be expected, because the probability of taking a direct object is lower for reciprocal verbs than for OT verbs, which was confirmed by the observation that in the SCT the participants were far less likely to write direct objects after reciprocal verbs.

The SCT results also indicated that the conjoined NP is more likely than the plural definite noun to induce reciprocal reading, as reciprocal reading requires readers to access the individuals within the plural sets (Patson & Ferreira, Reference Patson and Ferreira2009; Patson & Warren, Reference Patson and Warren2010), and the conjoined NP explicitly denotes the individuals in the plural sets while the plural definite noun does not. Thus, the indication in the findings that the combination of reciprocal verb and conjoined NP made participants more likely to read reciprocally than that of reciprocal verb and plural definite noun is plausible. This tendency is also compatible to some extent with the results of the SPRT: although it seemed that participants interpreted sentences with reciprocal verbs reciprocally regardless of noun type, they appeared to have processing difficulty in the case where a plural definite noun was the subject of a reciprocal verb, as reflected by the fact that RT slowed when participants encountered the object noun of the main verb, two words after the target verb region. The only condition that showed no RT delay among the several regions of interest was the combination of conjoined NP and reciprocal verb, indicating that a conjoined NP, which explicitly denotes the individuals in plural sets, might help participants induce reciprocal readings more easily. Nevertheless, we cannot be 100% sure that the participants assigned reciprocal reading to the reciprocal verbs, because we did not directly measure the participants’ interpretation of the verbs in the SPRT. If we had done so, the participants would have noticed that the focus of the SPRT was the interpretation of the verbs. Therefore, we do not know the participants’ preference toward transitive reading in the SPRT; however, if we look at the results of the SCT, we can see that most of the time, the participants showed reciprocal interpretation if the verb of the subordinate clause was a reciprocal verb, although the percentage was higher when the subjects of the reciprocal verbs were conjoined subjects. Even though the SCT was an offline task, we can reasonably infer that the participants must have preferred reciprocal reading in processing reciprocal verbs in the SPRT.

The difference between conjoined NP and plural definite nouns may, in part, be explained by L1 transfer effects, as suggested by Shibuya and Wakabayashi (Reference Shibuya and Wakabayashi2008). In Japanese, no bound morpheme is attached to nouns to specify plurality, but quantifiers can be attached ([10a] and [10b]).

(10) a. kodomo-ga rouka-de hanashite-iru

(The) child/children-ga[NOM] the hallway-de[LOC] talk-iru[PROG]

“(The) child/children is/are talking in the hallway.”

b. kodomo-ga san-nin rouka-de hanashite-iru

(The) child/children-ga[NOM] three-nin[CL] the hallway-de[LOC] talk-iru[PROG]

“(The) three children are talking in the hallway.”

In other words, Japanese does not require the processing of bound morphemes, unlike English, and this might have caused difficulty for the Japanese EFL learners in the current experiment when they attempted to process conceptual plurality present in plural definite nouns.

The present study’s results, as summarized above, seem to contradict some of the previous L2 research, which showed L2 speakers having difficulty accessing conceptual plural information in a sentence production task (e.g., Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Chen, Liang and Dunlap2015). Two possible explanations are worth discussing here. One big difference between the previous literature and the present study is the mode of language being considered: production versus comprehension. Though L1 research like that cited in the literature review section has shown that L1 speakers use conceptual number information during sentence comprehension (e.g., Kreiner et al., Reference Kreiner, Garrod and Sturt2013), this might not hold true in light of the present results because L2 speakers’ performance is more vulnerable to disruption than that of L1 speakers, and is sometimes inconsistent across different tasks. Clearly, future research needs to investigate and compare the accessibility of conceptual number information in both production and comprehension, across L1 and especially L2 speakers.

The other, and the more critical, difference between the previous research and the present study is that the present study did not investigate number agreement phenomena. Researchers investigating the representation and processing of conceptual number information through subject–verb number agreement are interested in the interface between conceptual and grammatical number processing, and researchers who have demonstrated L2 learners’ inability to use conceptual number in making number agreement in online tasks have posited that conceptual number does not invade grammatical processing (Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010, Reference Hoshino, Kroll and Dussias2012; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Chen, Liang and Dunlap2015). As our study did not examine number agreement process, its results do not inevitably contradict the evidence previously accumulated. Rather, the present study can add a novel viewpoint to those of previous L2 studies investigating conceptual number information: EFL learners whose L1 does not have an obligatory morphological number marking system succeed in accessing conceptual plural information in online sentence processing if grammatical number agreement is not concerned. As reviewed earlier, reciprocal verbs call not for grammatical number, but conceptual number (Fiengo & Lasnik, Reference Fiengo and Lasnik1973; Gleitman et al., Reference Gleitman, Gleitman, Miller and Ostrin1996); thus, it might be that L2 learners are able to access conceptual number information in online processing but that this information is not “strong” enough to invade the grammatical number agreement process.

The availability of conceptual number information could be explained by the two-stage agreement process (Hartsuiker & Barkhuysen, Reference Hartsuiker and Barkhuysen2006) and the required cognitive resources. According to Hartsuiker and Barkhuysen (Reference Hartsuiker and Barkhuysen2006), the first stage, number mapping between conceptual representation and functional representation, is not vulnerable to resource limitations, whereas the later stage, integrating number information, does suffer if sufficient cognitive resources are not available. Following this account, Hoshino et al. (Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010) insisted that the reason why low-proficiency L2 speakers in their study did not show sensitivity to conceptual number is because the low-proficiency L2 speakers failed in the second stage due to their limited cognitive resources. Thus, Hoshino et al. (Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010) assumed that their low-proficiency participants might have succeeded in mapping conceptual number to functional representation but failed to integrate conceptual number information in the later stage. Therefore, it should be noted that the participants in the present study who succeeded in accessing conceptual plurality in reciprocal sentences might not show sensitivity to conceptual number in number agreement, as Hoshino et al. (Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010, Reference Hoshino, Kroll and Dussias2012) argued.

Finally, let us recall and consider that reciprocal constructions in Japanese and English both require the readers to access conceptual plurality. In the literature review, we introduced Japanese reciprocal constructions, focusing on V+aw, and explained that in Japanese too, speakers would be expected to access conceptual plurality to make a reciprocal interpretation. Unlike English, Japanese does not necessarily mark plurality of nouns; but as we saw, even if the subject NP is unmarked for number, V+aw makes the subject NP conceptually plural, so that the sentence can be made understandable. Though it is only a tentative speculation at this point, this could be one reason that Japanese EFL learner participants were able to access conceptual plurality of subject NP in reading English reciprocal sentences. As the present study did not include other L2 or L1 comparison groups to look for possible differences in L1 effects, further investigation is necessary to assess this possibility.

Limitations and implications for future research

Here we present a number of limitations of the present study that may affect its interpretation. First, although much of the previous research has applied the SPRT to investigate various types of garden-path effect (e.g., Juffs, Reference Juffs1998; Juffs & Harrington, Reference Juffs and Harrington1996), one of the limitations of this task is that we cannot reliably determine the process of reanalysis. In reading garden-path sentences, the comprehender is presumed to move backward after encountering interpretive breakdown to reparse the sentence in a correct way. However, the method used in this study did not allow the participants to move backward in this way, because it could have made the analysis of RT in each region more complicated and chaotic. In this sense, an eye-tracking procedure might be preferable in that it enables us to observe regressions (reader’s backward eye movements). It should be noted in this regard, however, that Patson and Warren (Reference Patson and Warren2010) replicated the findings of Patson and Ferreira’s (Reference Patson and Ferreira2009) eye-movement experiments using a self-paced reading task, which may help address concern about this limitation.

Second, it must be acknowledged that not all the test items were followed by comprehension questions, although comprehension questions did follow distracter items to help the participants focus on meaning during the experiment. In this sense, it was inevitably unclear whether the participants succeeded in ambiguity resolution. The lack of comprehension questions after target items is related to the nature of the self-paced reading task used in this study. Due to the unavailability of backward reading and reanalysis, it cannot be ruled out that participants did not reach a final appropriate interpretation. Thus, whether there was any RT delay or not does not fully reveal the success of ambiguity resolution. However, asking whether the participants comprehended the sentences correctly may have been rather unfair, because they might have failed to understand the sentences due to the prohibition on reparsing them; future studies should compensate for this limitation.

Third, one may point out that the plausibility of the verb in the subordinate clause and the following NP combinations might have been problematic. It should be acknowledged that some of the test items accidentally included implausible or infrequent verb + NP structures: those are argued the student, negotiated the manager/man, battled the child/the employer, recovered the editor/manager, protested the referee/the employer, and write somebody. Among the six less plausible phrases, four are OT (negotiate, recover, protest, and write). These four OT verbs would have induced transitive reading due to the lower likelihood of them taking human being as their direct object. However, if so, the sentences with OT verbs would have been likely to show smaller garden-path effects, because the NP following the OT would be more likely to be interpreted as the subject of the main clause, which would block the garden-path effect. Nevertheless, the sentences with OTs were read more slowly than those with reciprocal verbs, thereby showing the garden-path effect. Still, the experimental materials should be revised and improved for future research to address this issue.

Fourth and finally, including native speakers of English as a control group would have been worthwhile, given that it would have allowed us to compare the processing tendency of L1 and L2 speakers of English. However, interpreting the results of L1–L2 comparison in the same tasks needs caution, particularly when the L2 learners are not highly proficient, as often in EFL environments. In these cases, usually, test materials are tailored to learners, for instance, to avoid low-frequency vocabulary and complex sentence structures, which are difficult for L2 learners to process. The resulting easiness might allow L1 speakers to engage in heuristic processing, because L1 speakers do not find these items difficult to process. As a result, we might not be able to capture L1 speakers’ real processing behavior. Bearing this caution in mind, future studies need to examine similarities and dissimilarities between L1 and L2 speakers of English with regard to the use of conceptual plural information in tasks like those used in our study and in Patson and Ferreira (Reference Patson and Ferreira2009).

Similarly, and with focus on the learner factors, it should be acknowledged that not all of the variables that could potentially influence the results (e.g., age and study abroad experience) were taken into account in the analysis, although the participants’ L2 language proficiency scores were examined in analyzing the data. The impact that the other variables have upon the processing of conceptual plural information will be worth investigating in future research.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The purpose of the present study was to investigate native-Japanese-speaking L2 English speakers’ representation and processing of conceptual plurality apart from number agreement, which has been the approach taken by the bulk of the previous research (Foote, Reference Foote2010; Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010, Reference Hoshino, Kroll and Dussias2012; Kusnagi et al., Reference Kusanagi, Tamura and Fukuta2015; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Chen, Liang and Dunlap2015). To achieve this objective, we investigated L2 speakers’ comprehension process from the viewpoint of reciprocal verbs, whose processing requires accessing the conceptual plurality of the subject NP. We confirmed through the written sentence completion task that our participants understood that reciprocal verbs do not need a direct object when the subject NP has plurality, while the results of the self-paced reading task suggest that the participants succeeded in accessing conceptual plurality and did not show RT delay in reciprocal conditions compared to the conditions where the participants read OT verbs, in which retrieving conceptual plurality is not necessary for understanding. In addition, explicitly denoting plurality of NP by conjoining two singular NPs (e.g., the boy and the girl) appeared to help the learners access conceptual plurality, similar to the case of L1 speakers (Patson & Ferreira, Reference Patson and Ferreira2009). This could be evidence that L2 speakers are capable of using conceptual plurality in online sentence processing if we are not concerned about whether conceptual number information overrides grammatical number, which was the focus of the previous L2 literature (Foote, Reference Foote2010; Hoshino et al., Reference Hoshino, Dussias and Kroll2010, Reference Hoshino, Kroll and Dussias2012; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Mormer and Brehm2018; Wei et al., Reference Wei, Chen, Liang and Dunlap2015). Though several limitations we mentioned in the previous section should be kept in mind, we hope the present findings will be viewed as helpful to broadening the understanding of the nature of conceptual representation of number information in L2 speakers.

APPENDIX A

Test items for the experiment

1a When the producer and the editor fought the actor cancelled the offer of the program.

1b When the editors fought the actor cancelled the offer of the program.

1c When the producer and the editor criticized the actor cancelled the offer of the program.

1d When the editors criticized the actor cancelled the offer of the program.

2a When the artist and the painter hugged the son played the violin with the teacher.

2b When the artists hugged the son played the violin with the teacher.

2c When the artist and the painter wrote the son played the violin with the teacher.

2d When the artists wrote the son played the violin with the teacher.

3a When the doctor and the nurse dated the chef cooked the dish in the restaurant.

3b When the doctors dated the chef cooked the dish in the restaurant.

3c When the doctor and the nurse paid the chef cooked the dish in the restaurant.

3d When the doctors paid the chef cooked the dish in the restaurant.

4a When the manager and the secretary kissed the worker entered the room with the colleagues.

4b When the managers kissed the worker entered the room with the colleagues.

4c When the manager and the secretary investigated the worker entered the room with the colleagues.

4d When the managers investigated the worker entered the room with the colleagues.

5a While the professor and the lecturer argued the student sang the song in the classroom.

5b While the professors argued the student sang the song in the classroom.

5c While the professor and the lecturer investigated the student sang the song in the classroom.

5d While the professors investigated the student sang the song in the classroom.

6a While the boy and the girl dated the performer played the piano on the stage.

6b While the teenagers dated the performer played the piano on the stage.

6c While the boy and the girl paid the performer played the piano on the stage.

6d While the teenagers paid the performer played the piano on the stage.

7a While the actor and the actress embraced the woman took the photograph in the theater.

7b While the actors embraced the woman took the photograph in the theater.

7c While the actor and the actress emailed the woman took the photograph in the theater.

7d While the actors emailed the woman took the photograph in the theater.

8a While the French and the Spanish hugged the girl watched the dog in the park.

8b While the Europeans hugged the girl watched the dog in the park.

8c While the French and the Spanish searched the girl watched the dog in the park.

8d While the Europeans searched the girl watched the dog in the park.

9a As the waiter and the waitress met the manager gave the promotion to the employee.

9b As the waiters met the manager gave the promotion to the employee.

9c As the waiter and the waitress negotiated the manager gave the promotion to the employee.

9d As the waiters negotiated the manager gave the promotion to the employee.

10a As the wife and the husband divorced the woman published the article on the newspaper.

10b As the lovers divorced the woman published the article on the newspaper.

10c As the wife and the husband wrote the woman published the article on the newspaper.

10d As the lovers wrote the woman published the article on the newspaper.

11a As the mayor and the councilor fought the journalist reported the argument on the internet.

11b As the politicians fought the journalist reported the argument on the internet.

11c As the mayor and the councilor criticized the journalist reported the argument on the internet.

11d As the politicians criticized the journalist reported the argument on the internet.

12a As the mother and the father battled the child played the guitar in the room.

12b As the parents battled the child played the guitar in the room.

12c As the mother and the father left the child played the guitar in the room.

12d As the parents left the child played the guitar in the room.

13a After the writer and the novelist married the editor heard the news on the radio.

13b After the writers married the editor heard the news on the radio.

13c After the writer and the novelist recovered the editor heard the news on the radio.

13d After the writers recovered the editor heard the news on the radio.

14a After the runner and the cyclist met the boy called the mother on the phone.

14b After the athletes met the boy called the mother on the phone.

14c After the runner and the cyclist searched the boy called the mother on the phone.

14d After the athletes searched the boy called the mother on the phone.

15a After the singer and the guitarist married the manager held the interview at the company.

15b After the musicians married the manager heard the interview at the company.

15c After the singer and the guitarist recovered the manager held the interview at the company.

15d After the musicians recovered the manager held the interview at the company.

16a After the king and the queen kissed the baby read the book in the bed.

16b After the leaders kissed the baby read the book in the bed.

16c After the king and the queen left the baby read the book in the bed.

16d After the leaders left the baby read the book in the bed.

17a Because the novelist and the poet divorced the man sent the letter to the family.

17b Because the writers divorced the man sent the letter to the family.

17c Because the novelist and the poet negotiated the man sent the letter to the family.

17d Because the writers negotiated the man sent the letter to the family.

18a Because the musician and the comedian embraced the man took his phone from the pocket.

18b Because the entertainers embraced the man took his phone from the pocket.

18c Because the musician and the comedian emailed the man took his phone from the pocket.

18d Because the entertainers emailed the man took his phone from the pocket.

19a Because the coach and the trainer argued the referee canceled the game on the way.

19b Because the coaches argued the referee canceled the game on the way.

19c Because the coach and the trainer protested the referee canceled the game on the way.

19d Because the coaches protested the referee canceled the game on the way.

20a Because the engineer and the mechanic battled the employer called the chief by the phone.

20b Because the engineers battled the employer called the chief by the phone.

20c Because the engineer and the mechanic protested the employee called the chief by the phone.

20d Because the engineers protested the employer called the chief by the phone.