Introduction

The study of moral injury has predominantly focused on military and high-risk occupations characterized by regular exposure to situations in which harm could arise through errors of judgement, failure to follow protocol, or ethical dilemmas. However, potentially morally injurious events can also occur in everyday community contexts. For example, a sleep-deprived individual may cause a road traffic accident; a concerned neighbour may fail to report family violence in their community; or a family member may struggle with end-of-life care decisions on behalf of a loved one. Such events may involve direct or witnessed transgressions against the individual’s moral code. According to a commonly accepted model of moral injury, such transgressions are theorized to result in discrepancy between the individual’s self-schema and the transgressive event, giving rise to event-related distress (Litz et al., Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009). When unresolved, this event-related distress may give rise to moral injury, a potentially debilitating condition characterized by guilt, shame, demoralization, self-condemnation, social alienation, and difficulties with trust and forgiveness (Litz et al., Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009). Recent empirical support for Litz et al.’s (Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009) proposal identified an association between discrepancy from a socially prescribed self-standard (i.e. what an individual believes others expect of them) and greater moral injury event-related distress (James et al., Reference James, McKimmie and Maccallum2024). However, aspects of the self that render an individual more or less vulnerable to this self-discrepancy and its flow-on effects have yet to be investigated, with implications for intervention. As moral injury shares some features with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the two are often treated with the same interventions such as prolonged exposure, which may not be effective in addressing the moral emotions of guilt and shame (Steenkamp et al., Reference Steenkamp, Litz, Hoge and Marmar2015). Improved understanding of aspects of the self that influence event-related distress severity can support the development of targeted interventions.

In their influential self-memory system model, Conway and Pleydell-Pearce (Reference Conway and Pleydell-Pearce2000) theorize that self-discrepancy arises following a disruptive life event when continuity of important roles (e.g. one’s profession or one’s relationships), or progress toward valued goals (e.g. belonging or meaning) is obstructed. While individuals can adapt by updating roles and goals or adopting new ones, failure to adapt in this way is thought to be associated with poorer outcomes for a range of disruptive life events including potentially traumatic events and bereavement (Conway and Pleydell-Pearce, Reference Conway and Pleydell-Pearce2000; Maccallum and Bryant, Reference Maccallum and Bryant2013). The development of targeted interventions for moral injury therefore warrants investigation of personal resources that could support an individual in updating disrupted roles and goals. A complex and multi-faceted self-concept is one such resource thought to play a role in adaptation following disruptive life events more broadly. Self-concept is thought to develop through experiences of varying relationships, roles, activities, behaviours, and situations drawn from sociocultural influences such as family, peers, education, religion, and culturally salient stories (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Singer and Tagini2004; Linville, Reference Linville1985). With this range of influences on self-concept, the level of self-complexity is thought to vary across individuals, with greater self-complexity defined as a broader range of inter-related facets pertaining to various domains of life, such as attributes, behaviours, roles, and relationships (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Singer and Tagini2004; Linville, Reference Linville1985). A self-concept dominated by a narrow range of roles and goals is considered vulnerable to disruption, whereas having a wide and diverse range of achievable roles and goals is proposed to reduce the threat to overall self-concept posed by disruption to one role or goal (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Singer and Tagini2004; Linville, Reference Linville1985).

To our knowledge, the relationship between self-complexity and moral injury has not been investigated. However, research into other disruptive event-related outcomes including grief and PTSD serves to guide investigation into the possible protective role of self-complexity following potentially morally injurious events. In studies of bereavement and non-bereavement losses (e.g. divorce, job loss), self-complexity is operationalized as consisting of self-diversity, which refers to the number of categories self-descriptors fall into, and self-fluency, which refers to the overall number of self-descriptors. Studies primarily index self-complexity by asking participants to list self-descriptive statements within a time limit. For example, Bellet et al. (Reference Bellet, LeBlanc, Nizzi, Carter, van der Does, Peters, Robinaugh and McNally2020) indexed self-complexity in a sample of bereaved adults using the Twenty Statements Test (TST; Kuhn and McPartland, Reference Kuhn and McPartland1954) in which participants were asked to complete the phrase ‘I am’ by providing up to 20 self-descriptive statements. Participants with prolonged grief disorder provided descriptors consisting of fewer categories and provided fewer self-descriptors overall, suggesting both lower self-diversity and self-fluency were associated with increased distress. Furthermore, Bellet et al. (Reference Bellet, LeBlanc, Nizzi, Carter, van der Does, Peters, Robinaugh and McNally2020) identified diversity of activities as uniquely important in buffering the effects of grief, with participants with prolonged grief disorder providing significantly fewer descriptors in this category than those without prolonged grief disorder. Papa and Lancaster (Reference Papa and Lancaster2016) also used the TST to investigate self-complexity and grief severity following bereavement and non-bereavement losses. Consistent with Bellet et al. (Reference Bellet, LeBlanc, Nizzi, Carter, van der Does, Peters, Robinaugh and McNally2020), lower self-fluency was associated with more severe grief symptoms for both bereavement and non-bereavement losses. Moreover, a more balanced distribution of descriptors across categories, reflecting a combination of individual, relational, and societally defined roles, was also related to less severe symptoms compared with when an individual’s descriptors were mostly individual traits (Papa and Lancaster, Reference Papa and Lancaster2016).

Self-complexity has also been investigated in PTSD, although with different methods to prolonged grief. Channer and Jobson (Reference Channer and Jobson2017) asked participants to select self-descriptors from a pre-defined list that included positively and negatively valenced descriptors. Using this method, they found that individuals with PTSD selected more self-descriptors overall, spread across more categories than those without PTSD, suggesting greater self-fluency and self-diversity. Using the same task, Clifford et al. (Reference Clifford, Hitchcock and Dalgleish2020a, Reference Clifford, Hitchcock and Dalgleish2020b) found that individuals with PTSD selected more negative descriptors but found no association between the overall number of self-descriptors and PTSD. This may reflect the impact of methodological differences across PTSD and grief studies, whereby having participants select items from a list produces a different pattern of findings to self-generating responses. Nonetheless, both methodologies suggested particular patterns of conceptualizing the self may be associated with poorer outcomes. Given that moral injury is thought to arise from self-discrepancy incurred through a disruptive life event, these aspects of self-complexity might also play a role in adaptation after a potentially morally injurious event.

This study thus sought to further our understanding of moral injury by investigating the possible protective role of a complex self-concept in a community sample exposed to potentially morally injurious events. Participants provided descriptors of their self-concept, which were coded in accordance with up to 10 descriptive categories, including roles based on activities and social relationships. Consistent with studies that have used this methodology with bereaved populations, we predicted that higher levels of self-diversity (more categories) (H1) and self-fluency (more descriptors overall) (H2), and a greater number of roles (H3) would all be associated with less severe event-related distress. Furthermore, as moral injury is not the only potential outcome of exposure to a potentially morally injurious event (Nash et al., Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz2013), we also explored possible relationships between self-complexity and other common outcomes. These included traumatic stress, depression and generalised anxiety, which have been associated with guilt and shame, the core emotional features of moral injury event-related distress (Cândea and Szentagotai-Tătar, Reference Cândea and Szentagotai-Tătar2018; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Thibodeau and Jorgensen2011; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Ren, Zhao, Zhang and Ho-Wan Chan2021). While we did not make predictions regarding these relationships, we anticipated that comparison might further distinguish moral injury from other potential sequelae of potentially morally injurious events.

Method

Transparency and openness

This research conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki. This study’s design, hypotheses and analysis plan were pre-registered on the Open Science Framework website, and we report on all pre-registered analyses. Data were analysed using SPSS version 29. SPSS analysis code and all research materials are available (https://osf.io/9h6wb/?view_only=478e18860c1f4a8d85ba3e8613bfdce7). Due to the sensitive nature of the data, and in accordance with our ethics approval, data are not publicly available.

Participants and procedure

Cross-sectional data were collected via Qualtrics as part of a larger series of studies. Participants were resident in the UK, fluent in English, and aged between 25 and 70. Initial screening of 2021 potential participants (50% female) via Prolific (https://www.prolific.co/) identified participants who had been exposed to a potentially morally injurious event in the previous 10 years. Approximately half of these participants endorsed exposure. Selection was then narrowed to those who had experienced a potentially morally injurious event in the previous 1–5 years to capture participants who may have experienced both recent and delayed-onset outcomes (Bonde et al., Reference Bonde, Jensen, Smid, Flachs, Elklit, Mors and Videbech2022). G*Power analysis (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang2009) identified a minimum sample size of 138 for an adequately powered correlation analysis, and we aimed to surpass this number to account for attrition across two survey rounds. Participants who endorsed experiencing a target event were randomly invited to the first of the two surveys until sample size requirements were met. In Survey 1, participants clicked on a link on the Prolific website and were taken to an information page to complete informed consent before completing, in order, demographics, the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8), the Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES), the Event Type Checklist, and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL8-5), as well as measures unrelated to the aims of this study. Of the 319 participants who completed Survey 1, 233 indicated exposure to both a potentially morally injurious event captured by the MIES and an event type listed on the Event Type Checklist. Within 2 weeks of completing Survey 1, these participants were invited to complete Survey 2, which 172 (73.8%) participants completed. In Survey 2, participants again completed informed consent before completing the TST as well as other measures unrelated to this study. Surveys 1 and 2 took approximately 10 and 20 minutes to complete and contained four and two attention checks, respectively, which directed participants to provide specific responses to questions (Oppenheimer et al., Reference Oppenheimer, Meyvis and Davidenko2009). Thirteen participants were not invited to Survey 2 based on failed attention checks in Survey 1. Participants who completed Survey 2 did not differ significantly in age, gender or ethnicity, and did not score differently on any measure of psychopathology from those who completed Survey 1 and were eligible for but did not commence Survey 2. Upon completion, participants were thanked for their participation and provided with information about options for support from local services. Participants received a total of £3.55 as compensation for completing all surveys. The study was approved by the University of Queensland Research Ethics and Integrity Committee (ID number: 2021/HE001513).

Measures

Life Events Questionnaire

We developed this questionnaire to screen for possible exposure to a potentially morally injurious event prior to recruitment without alerting participants to the main purpose of the study. Participants indicated whether and when they had experienced any of 10 life events in the previous 10 years (e.g. retirement, bereavement), presented in random order. Four target events met criteria for inclusion in Survey 1: I witnessed something traumatic happen to another person/people; I failed to defend or protect someone from harm; I contributed to something that had a bad outcome; and I had to do something that was bad or wrong. These events are consistent with the transgression-self and transgression-other subscales of the MIES. Non-target events (e.g. My partner or I had a baby; I retired from work) were not considered potentially morally injurious.

Moral Injury Events Scale

The MIES (Nash et al., Reference Nash, Marino Carper, Mills, Au, Goldsmith and Litz2013) is a widely used 9-item self-report measure originally designed to identify exposure to and perceived intensity of potentially morally injurious events in a military context. Items measure both event exposure and event-related distress, and meta-analyses and factor analytic studies support the use of the MIES as a measure of event-related distress at both full and subscales across settings and populations (Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green, Etienne, Morrow and Ray-Sannerud2016; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Chesnut, Morgan, Bleser, Perkins, Vogt, Copeland and Finley2020; Steen et al., Reference Steen, Law and Jones2024). As unresolved event-related distress is thought to predict moral injury (Litz et al., Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009), the MIES serves as a proxy for the measurement of moral injury in the current study, in which participants’ event exposure had occurred between 1 and 5 years prior. Participants responded on a 6-point scale (where 1 is strongly agree; and 6 is strongly disagree). Summed scores range from 9 to 54, with lower scores indicating higher event-related distress, and higher scores indicating low or no event-related distress. Participants who indicated any level of agreement with exposure items on the MIES met criteria for inclusion. The wording of the MIES was adapted for use with a general population: e.g. ‘I feel betrayed by fellow service members who I once trusted’ was modified to ‘I feel betrayed by family/friends/colleagues who I once trusted’ (see Pfeffer et al., Reference Pfeffer, Hart, Satterthwaite, Bryant, Knuckey, Brown and Bonanno2023). The reliability of the MIES in the current sample was satisfactory (α=0.81).

Event Type Checklist

We developed a checklist as a follow-up to the MIES to elicit further information about the nature of the potentially morally injurious events that participants had experienced. The checklist, which was based on items derived from previous questionnaires (Weathers et al., Reference Weathers, Blake, Schnurr, Kaloupek, Marx and Keane2013; Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Kimerling, Brown, Chrestman and Levin1997), included violence, harassment, deception, maltreatment, suffering of another, and dilemma; additional filler event types (sub-standard behaviour including disrespect, carelessness, and irresponsibility; emotional neglect in adulthood including rejection, abandonment, and invalidation) were included. Participants could select multiple event types that characterized their experience as rated on the MIES. Those who selected one or more potentially morally injurious event types were invited to Survey 2.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5

The PCL8-5 (Price et al., Reference Price, Szafranski, van Stolk-Cooke and Gros2016) is a validated 8-item abbreviated version of the PCL-5 self-report measure used to screen for symptoms of traumatic stress. Participants were asked to indicate how often they had been bothered by eight possible problems over the preceding 4 weeks (e.g. ‘repeated, disturbing, and unwanted memories of the stressful experience’, ‘avoiding memories, thoughts, or feelings related to the stressful experience’, ‘having strong negative beliefs about yourself, other people, or the world (for example, having thoughts such as: I am bad, there is something seriously wrong with me, no one can be trusted, the world is completely dangerous)’). Participants responded on a 5-point scale (where 0 is not at all; and 4 is nearly every day). Total scores range from 0 to 32, with a score of 19 or more indicating probable PTSD. Sample Cronbach’s α was 0.93.

Patient Health Questionnaire

The PHQ-8 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Strine, Spitzer, Williams, Berry and Mokdad2009) is a widely used and validated 8-item self-report measure of depression symptoms. Participants were asked to indicate how often they had been bothered by eight possible problems over the preceding 2 weeks (e.g. ‘little pleasure or interest in doing things’, ‘feeling down, depressed, or hopeless’, ‘feeling bad about yourself, or that you are a failure, or have let yourself or your family down’). Participants responded on a 4-point scale (where 0 is not at all; and 3 is nearly every day). Total scores range from 0 to 24, with a score of 10 or more indicating moderate to severe levels of depression. Sample Cronbach’s α was 0.91.

Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment

The GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) is a widely used and validated 7-item self-report measure of general anxiety symptoms. Participants were asked to indicate how often they had been bothered by seven possible problems over the preceding 2 weeks (e.g. ‘feeling nervous or on edge’, ‘not being able to stop or control worrying’, ‘trouble relaxing’). Participants responded on a 4-point scale (where 0 is not at all; and 3 is nearly every day). Total scores range from 0 to 21, with a score of 10 or more indicating moderate to severe levels of anxiety. Sample Cronbach’s α was 0.91.

Twenty Statements Test

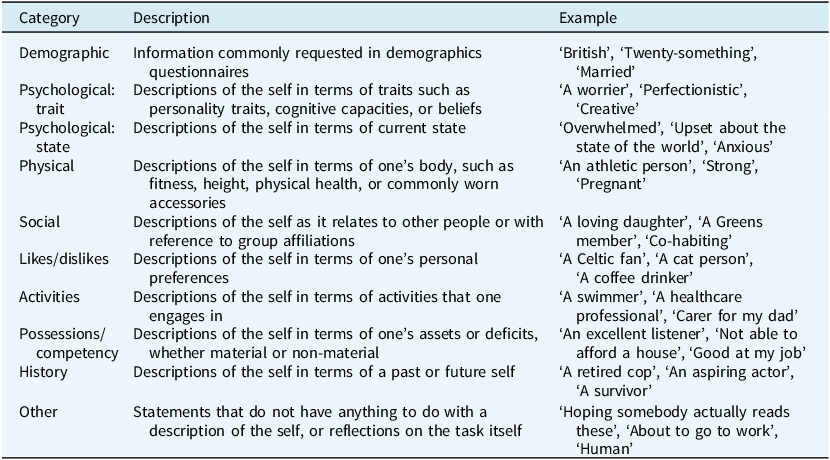

The TST (Kuhn and McPartland, Reference Kuhn and McPartland1954) involved a task in which participants were asked to list up to 20 statements they felt described themselves accurately in two minutes. Data were coded by two raters according to an adapted version of Bellet et al.’s (Reference Bellet, LeBlanc, Nizzi, Carter, van der Does, Peters, Robinaugh and McNally2020) Self-Profile Coding System with a maximum of 10 possible descriptive categories (see Table 1). The inter-rater reliability coefficient between coders was .78. Self-fluency was calculated as the total number of self-descriptors; self-diversity as the number of descriptive categories; and role diversity as the total number of self-statements identified as social/relational or activity-based (e.g. family relationships, occupational or social roles, group or team memberships) (Papa and Lancaster, Reference Papa and Lancaster2016).

Table 1. Adapted Self-Profile Coding System (Bellet et al., Reference Bellet, LeBlanc, Nizzi, Carter, van der Does, Peters, Robinaugh and McNally2020)

Results

Analytic strategy

We explored bivariate correlations and conducted planned multiple regression analyses to examine relationships between self-complexity and event-related distress, traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety. No outliers were observed, and skewness and kurtosis values were consistent with a normal distribution. Less than 2% of data was missing on any variable.

Participant demographic and symptom characteristics

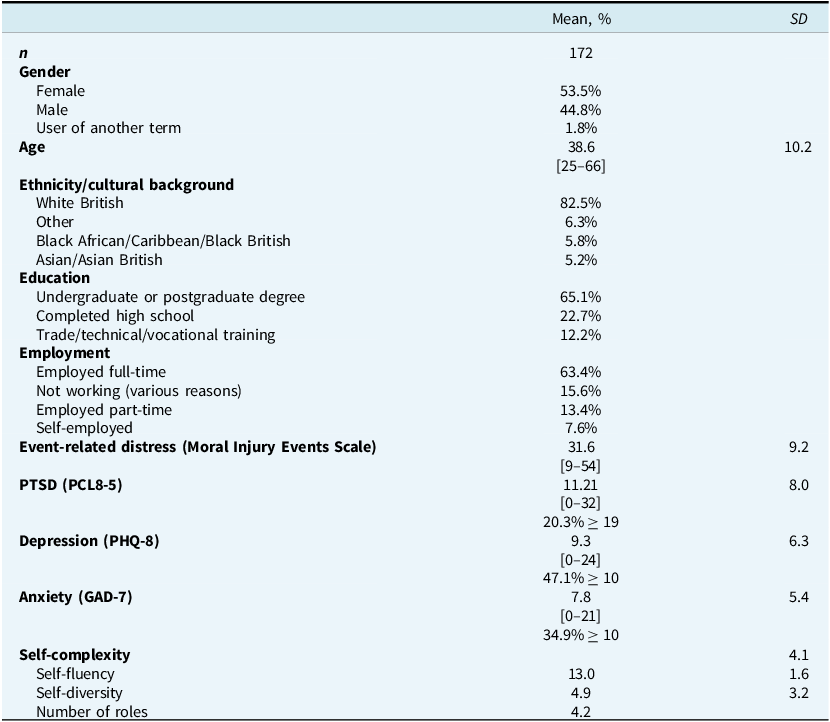

Table 2 displays participant characteristics and scores on all psychopathology measures (n=172). The mean age was 38.6 years (SD=10.2), and 53.5% were female. Mean total score on the MIES was 31.6 (SD=9.2). Just under half of the sample (47.1%) endorsed at least moderate levels of depression, 34.9% moderate levels of general anxiety, and 20.4% probable PTSD.

Table 2. Participant characteristics

Self-complexity

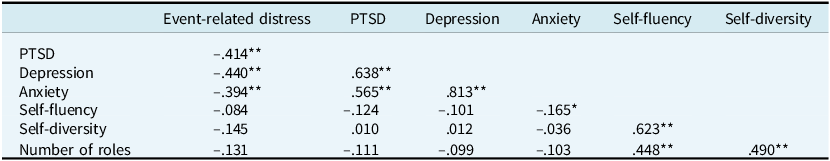

Mean self-complexity scores and correlations with measures of psychopathology are presented in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively. Event-related distress did not correlate with any measure of self-complexity; nor did traumatic stress or depression. There was a small correlation between anxiety and self-fluency such that, as self-fluency increased, anxiety decreased (r=–.165 p=.03).

Table 3. Correlations between self-complexity and distress

n=172. Higher scores on the MIES indicate lower event-related distress. Therefore, a negative correlation with this measure indicates higher self-complexity is associated with higher distress. *p<.05, **p<.01.

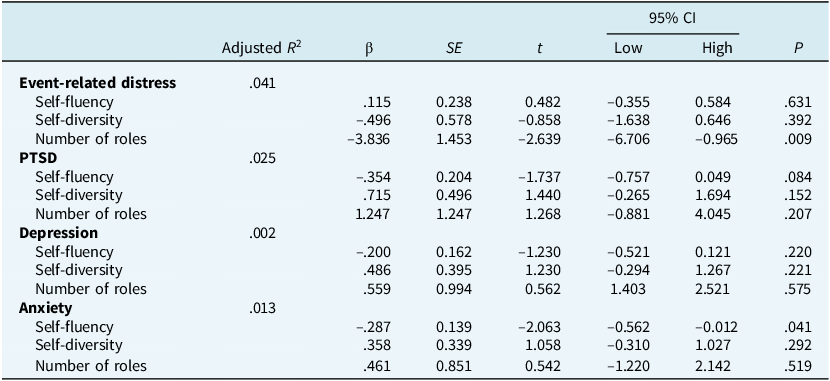

Table 4. Regression coefficients examining the relationship between self-complexity and event-related distress, PTSD, depression and anxiety

Table 4 presents the results of the planned regression analyses. The overall regression explained 4.1% of the variance in event-related distress (p=.029). Role diversity was the only independent predictor, with fewer roles associated with greater event-related distress (p=.009).

For traumatic stress and depression, the overall regression was not significant and none of the measures of self-complexity independently predicted variance in symptom severity. While the overall equation for general anxiety was non-significant (p=.186), lower self-fluency independently predicted higher anxiety severity (p=.041).

Discussion

We sought to extend understanding of moral injury by investigating the relationship between self-complexity and event-related distress in a community sample. We predicted that both greater self-fluency and self-diversity would be associated with lower event-related distress, but we did not find such a relationship. However, we did find that participants who described themselves as having a greater number of roles reported less severe event-related distress.

Theoretical models and studies of event-related psychopathology suggest that a more complex and multi-faceted self-concept is less vulnerable to the effects of a disruptive life event (Bellet et al., Reference Bellet, LeBlanc, Nizzi, Carter, van der Does, Peters, Robinaugh and McNally2020; Conway et al., Reference Conway, Singer and Tagini2004; Papa and Lancaster, Reference Papa and Lancaster2016). It was therefore surprising that self-diversity was not associated with event-related distress severity in our moral injury-exposed sample. One possible reason for this divergent finding is the importance of any given category of self-descriptor. Responses to our measure of self-complexity referenced a broad range of categories including those that reflected trait descriptions (e.g. creative, generous) and more transient states (e.g. excited, unsettled) in addition to personal goals and roles. Consistent with Bellet et al. (Reference Bellet, LeBlanc, Nizzi, Carter, van der Does, Peters, Robinaugh and McNally2020), when we restricted the analysis to active roles only, the expected association was observed. This suggests that a diverse array of roles may be more supportive of adaptation following a potentially morally injurious event than a diversity of descriptive traits and characteristics. These findings are consistent with theoretical models that emphasize the importance of meaningful goals and roles to adaptation (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Singer and Tagini2004). Replication of these findings is needed to affirm whether role diversity is the only aspect of a diverse self-concept that impacts the severity of event-related distress following a potentially morally injurious event. If replicated, this could have implications for fine-tuning the definition of self-diversity.

Our finding that greater role diversity was associated with lower event-related distress suggests that a broader diversity of roles may offer protection from the impacts of a potentially morally injurious event. According to the commonly accepted model of moral injury, self-discrepancy following a transgressive event gives rise to event-related distress (James et al., Reference James, McKimmie and Maccallum2024; Litz et al., Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009). It may be that a diverse range of roles reduces the extent to which the transgressive event is experienced as disruptive to the self-concept as a broader range of relational and activity-based roles supports continuity of valued activities and a sense of belonging to valued groups (e.g. Bellet et al., Reference Bellet, LeBlanc, Nizzi, Carter, van der Does, Peters, Robinaugh and McNally2020; Conway et al., Reference Conway, Singer and Tagini2004; Papa and Lancaster, Reference Papa and Lancaster2016). However, the cross-sectional nature of the observed relationship does not allow us to test the direction of this relationship. Thus, it is also possible that a potentially morally injurious event may reduce role diversity by disrupting relationships or activities that are pivotal to the individual’s self-concept and reducing access to meaningful sources of social support (Bellet et al., Reference Bellet, LeBlanc, Nizzi, Carter, van der Does, Peters, Robinaugh and McNally2020; Litz et al., Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009). Alternatively, those with lower event-related distress may have more capacity to engage with and develop more roles, supporting adaptation after their disruptive experience (Bellet et al., Reference Bellet, LeBlanc, Nizzi, Carter, van der Does, Peters, Robinaugh and McNally2020). Longitudinal research can assist in determining the temporal sequence and direction of the association observed.

As previous studies had identified relationships between self-fluency and both grief and PTSD, it is surprising that self-fluency was not associated with event-related distress in the current study; yet the finding of the current study is not unique. Additional logistic regression analyses by Bellet et al. (Reference Bellet, LeBlanc, Nizzi, Carter, van der Does, Peters, Robinaugh and McNally2020) identified self-diversity as the only remaining predictor of prolonged grief, indicating that self-fluency did not provide additional predictive value. While it may be that moral injury is distinguished from PTSD in part by the absence of a relationship with self-fluency, important methodological differences impact the ability to make direct comparison between studies. Whereas participants in the current study generated their own self-descriptors, in previous studies of self-complexity and PTSD participants selected valenced options from a pre-defined list that included trauma-specific descriptors (Channer and Jobson, Reference Channer and Jobson2017; Clifford et al., Reference Clifford, Hitchcock and Dalgleish2020a; Clifford et al., Reference Clifford, Hitchcock and Dalgleish2020b). For participants with PTSD, higher overall self-fluency was related to selecting more negatively valenced self-descriptors, which may reflect a more negative self-concept rather than a more complex one (Channer and Jobson, Reference Channer and Jobson2017). Future research incorporating self-ratings of valence could explore whether event-related distress is similarly related to the proportion of negative self-descriptors, as this has implications for intervention targets.

The modest size of the relationship between role diversity and event-related distress is consistent with literature in the field suggesting individual variables may only have a small relationship with outcomes (Bonanno, Reference Bonanno2021). However, it is possible that even a small increase in the number of roles supports adaptation following a potentially morally injurious event. While there may exist an optimal number of roles for buffering the effects of event-related distress, it is also possible that certain roles are pivotal to the individual’s sense of self, serving as connectors to relationships and activities that provide resources for adaptation (Bellet et al., Reference Bellet, LeBlanc, Nizzi, Carter, van der Does, Peters, Robinaugh and McNally2020; Papa and Lancaster, Reference Papa and Lancaster2016). Future longitudinal research could examine this proposition by asking participants to rate the importance or centrality of their roles and mapping goal development and disruption over time in relation to event-related distress.

Consistent with expectations, role diversity was not associated with depression or anxiety. We considered these associations less likely as these reactions are not necessarily tied to a specific event. However, role diversity was not associated with traumatic stress either. In considering this finding it is important to recognize that participants were selected for exposure to a potentially morally injurious event rather than a potentially traumatic event. While there is likely some overlap between these event types, key features of different event types may have discrete impacts on important relationships or activities. For example, bereavement is associated with disrupted continuity of identity-relevant roles that are dependent on a key relationship (Papa and Lancaster, Reference Papa and Lancaster2016), whereas a potentially morally injurious event may disrupt continuity of identity-relevant roles through ostracism or social withdrawal motivated by shame or loss of trust (Litz et al., Reference Litz, Stein, Delaney, Lebowitz, Nash, Silva and Maguen2009). Future research comparing populations exposed to potentially traumatic versus potentially morally injurious events could assist in understanding whether event type impacts the relationship between role diversity and mental health outcomes.

We recognize that there are a number of limitations to the conclusions that can be drawn from this study. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of this study precludes causal conclusions. Also, while standard practice, coding of participants’ responses to the TST using the Self-Profile Coding System necessitates a degree of interpretation and coder discretion. While inter-rater reliability was acceptable, participants themselves might categorize self-descriptors differently from the research team, with potential implications for self-diversity and role diversity scores. Future studies could test this by asking participants to categorize their self-descriptors in their own words and comparing these categories against raters’ categories. Nevertheless, the use of the Self-Profile Coding System to assess self-concept complexity in relation to moral injury facilitated the identification of greater role diversity as a unique predictor of reduced event-related distress, indicating a potential intervention target for further research. Additionally, consistent with previous studies, we used self-report measures, and we acknowledge that clinical interviews are also required to optimally identify levels of psychopathology. However, we note that event-related distress scores were comparable with non-military occupational samples (e.g. Benatov et al., Reference Benatov, Zerach and Levi-Belz2022; Pfeffer et al., Reference Pfeffer, Hart, Satterthwaite, Bryant, Knuckey, Brown and Bonanno2023), as were the proportion of our sample self-reporting clinically relevant levels of depression (47.1%) and anxiety (34.9%). Fewer participants exhibited clinically relevant levels of traumatic stress (20.4%). Furthermore, our sample reported lower levels of all forms of distress than treatment-seeking populations (e.g. Bravo et al., Reference Bravo, Kelley, Mason, Ehlke, Vinci and Redman2020; Bryan et al., Reference Bryan, Bryan, Anestis, Anestis, Green, Etienne, Morrow and Ray-Sannerud2016). Future research will assist in determining whether effect sizes observed in the current study might differ in a clinical sample.

Conclusion

In exploring a potential relationship between increased self-complexity and reduced event-related distress, this study provides the first empirical evidence of the relationship between role diversity and moral injury. While theories of adaptation suggest a multi-faceted self-concept supports adaptation following a disruptive life event, the current study indicates a more nuanced conclusion. Rather than simply being able to describe oneself in many and diverse ways, playing a broader range of roles may prove to be uniquely protective in buffering the effects of a potentially morally injurious event. Further research may identify role diversity as a target for more effective intervention in moral injury, with implications for increased emphasis on behavioural elements of CBT targeting increases in the range of active roles.

Data availability statement

The research protocol and analysis syntax for this study can be found at https://osf.io/9h6wb/. Due to the sensitive nature of the data collected, and in accordance with our ethics approval, data are not publicly available.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Kari James: Conceptualization (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Writing - original draft (lead), Writing - review & editing (lead); Blake McKimmie: Supervision (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Fiona Maccallum: Supervision (lead), Writing - review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This research has received no external funding.

Completing interests

We have no known competing interests to disclose.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the University of Queensland Research Ethics and Integrity Committee (ID number: 2021/HE001513).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.