Introduction

Self-esteem is a complex construct. According to Rosenberg’s theory (Reference Rosenberg1965), it means the evaluation of self-worth, the sense of one’s value as a person, and contains both beliefs and emotional states (Brown and Marshall, Reference Brown and Marshall2006; Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1965; Zeigler-Hill, Reference Zeigler-Hill2011). Low self-esteem (LSE) does not stand as a distinct diagnostic category; it can be interpreted as a continuum, from moments of discomfort in specific situations with little impact on overall functioning, to the sort of self-hatred and intense distress we see in borderline personality disorder. We can distinguish ‘fragile’/unstable and ‘secure’/stable self-esteem (Borton et al., Reference Borton, Crimmins, Ashby and Ruddiman2012; Kernis, Reference Kernis2003), or implicit (automatic, unconscious self-evaluation) and explicit self-esteem (direct reflection to self-worth) (Borton et al., Reference Borton, Crimmins, Ashby and Ruddiman2012; Bosson et al., Reference Bosson, Swann and Pennebaker2000; van Tuijl et al., Reference van Tuijl, de Jong, Sportel, de Hullu and Nauta2014; Zeigler-Hill and Terry, Reference Zeigler-Hill and Terry2007).

Relationship between LSE and mental disorders

LSE is closely related to a number of psychiatric disorders including depression, eating disorders, personality disorders and social phobia (APA, 2013; Fairburn et al., Reference Fairburn, Cooper and Shafran2003; Fennell, Reference Fennell1998; Sowislo and Orth, Reference Sowislo and Orth2013; Zeigler-Hill, Reference Zeigler-Hill2011). Decreased self-esteem plays a role in obsessive-compulsive disorders (Coughtrey et al., Reference Coughtrey, Shafran, Bennett, Kothari and Wade2018), psychosis (Tarrier et al., Reference Tarrier, Barrowclough, Andrews and Gregg2004; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zu, Xiang, Wang, Guo, Kilbourne and Li2013). Furthermore, LSE is also related to addictive behaviours (Arsandaux et al., Reference Arsandaux, Montagni, Macalli, Bouteloup, Tzourio and Galéra2020; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Choi and Kim2020), and self-harm or suicide attempts (Bhar et al., Reference Bhar, Ghahramanlou-Holloway, Brown and Beck2008; Palmer, Reference Palmer2004; Tarrier et al., Reference Tarrier, Barrowclough, Andrews and Gregg2004; Wisman et al., Reference Wisman, Heflick and Goldenberg2015). LSE has been shown to have a significant effect on people’s lives, not just in the context of psychopathology, but in a broader sense; for instance, dropping out of school early, teenage pregnancy and poor lifelong employment history (Mann et al., Reference Mann, Hosman, Schaalma and de Vries2004; Waite et al., Reference Waite, McManus and Shafran2012).

Based on longitudinal studies and meta-analyses, the vulnerability, scar and reciprocal models of LSE (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Galambos and Krahn2014; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Galambos and Krahn2016; Orth et al., Reference Orth, Robins, Meier and Conger2016; Sowislo and Orth, Reference Sowislo and Orth2013; Zeigler-Hill, Reference Zeigler-Hill2011) have demonstrated correlations between depressive symptomatology and low self-evaluation mostly in non-clinical samples. Based on a diathesis-stress framework (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Beck, Alford, Bieling and Segal2000), the vulnerability model described by several authors (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Galambos and Krahn2014; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Galambos and Krahn2016; Orth et al., Reference Orth, Robins, Meier and Conger2016; Sowislo and Orth, Reference Sowislo and Orth2013; Zeigler-Hill, Reference Zeigler-Hill2011) considers LSE as a risk factor for depressive and anxiety symptoms later on in life. In a two-year follow-up study, van Tuijl et al. (Reference van Tuijl, de Jong, Sportel, de Hullu and Nauta2014) found partial support for the vulnerability model in adolescence: LSE predicted increased symptoms of depression and social anxiety. Conversely, the scar model of LSE is based on the assumption that psychopathology, e.g. depressive episodes, leaves ‘scars’ on the person’s self-assessment, contributing to the development of LSE in the long run (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Galambos and Krahn2016; Orth et al., Reference Orth, Robins, Meier and Conger2016; van Tuijl et al., Reference van Tuijl, de Jong, Sportel, de Hullu and Nauta2014). Sowislo and Orth (Reference Sowislo and Orth2013) examined the two models in a meta-analysis and found a bi-directional connection between self-esteem and depressive symptoms, although the vulnerability model had stronger explanatory power and better fit indicators than the scar model. Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Galambos and Krahn2016) also demonstrated a reciprocal relationship between depressive symptoms and self-esteem in their longitudinal large-scale study. Although the studies focused primarily on the direction of relationships, all three models (vulnerability, scar and reciprocal) suggest that interpersonal as well as intrapersonal mechanisms mediate the relationship between psychopathology and self-esteem.

Fennell’s cognitive model of LSE

Despite the fact that LSE is associated with many mental disorders and is a key issue for psychological research, Melanie Fennell’s model (Fennell, Reference Fennell1997) seems to be the only comprehensive cognitive model of LSE. Based on Beck’s theory (Beck, Reference Beck1967; Beck, Reference Beck1979), in Fennell’s (Reference Fennell1997) cognitive model LSE is a learned pattern; early life events and temperament would establish negative core beliefs about the self (e.g. ‘I am worthless’, ‘I am stupid’), which lead to dysfunctional assumptions (e.g. ‘If I’m worthless, I’d better shut up’). This belief system can be activated by critical incidents, so the person will believe that he or she might not be able to meet the requirements of his/her assumptions, which in turn will lead to negative predictions, anxiety and maladaptive behaviour (avoidance, safety-seeking behaviours). This process may also lead to a sense that negative core beliefs have once again been confirmed, and may prompt self-criticism, which leads to depressed mood. This circle results in a sense that ‘negative beliefs about the self’ have been confirmed again and thus continue to maintain the activation of these beliefs and the entrapment in LSE.

In Fennell’s model LSE is based on patterns learned in the past that create a vulnerability to present events. LSE in the present is maintained by the sort of unhelpful behaviours/strategies which are then captured by the vicious circle. The circle is making the person vulnerable for a whole range of other difficulties in life; some of them are psychiatric issues. In other words, it creates a vulnerability to events which relate specifically to the person’s particular idiosyncratic self-beliefs, and which suggest that they might not be able to meet the terms of the dysfunctional attitudes they have adopted to cope with the negative core beliefs. This clash between current events and idiosyncratic, enduring cognitive patterns, leads to the activation of negative self-beliefs, followed by anxiety and depression (Fennell, Reference Fennell1997; Fennell, Reference Fennell1998). Despite the fact that at the cross-sectional level the self-maintaining cycle is based on reciprocal processes, the model as a whole can best be interpreted as a vulnerability model.

LSE as a consequence of transdiagnostic processes

Fennell’s model served as the basis for the development of cognitive therapy of LSE (Kolubinski et al., Reference Kolubinski, Frings, Nikčević, Lawrence and Spada2018). However, the model is more than 20 years old, and yet there had been almost no research done that would have tried to prove the validity of the model. In addition, during this time, the need to treat co-morbid and persistent mental disorders has posed new challenges for cognitive behavioural therapy (Clark and Taylor, Reference Clark and Taylor2009; Hayes and Hofmann, Reference Hayes and Hofmann2017; Newby et al., Reference Newby, McKinnon, Kuyken, Gilbody and Dalgleish2015a). The transdiagnostic approach allows a greater transfer of theoretical and treatment advances between disorders (Harvey et al., Reference Harvey, Watkins, Mansell and Shafran2015). In co-morbid conditions, the effectiveness of therapy can be significantly improved by focusing on common processes in the background (such as rumination, perfectionism, intrusive thoughts, avoidant behaviour), rather than thinking in separate diagnostic categories regarding the patient’s treatment. There is evidence that by addressing these patterns specifically, symptoms are better reduced in co-morbid conditions than with diagnosis-specific treatments (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Allen and Choate2016; Newby et al., Reference Newby, McKinnon, Kuyken, Gilbody and Dalgleish2015b; Sakiris and Berle, Reference Sakiris and Berle2019).

Dysfunctional beliefs

According to Beck’s cognitive theory (Beck, Reference Beck1967; Beck, Reference Beck1979) and the diathesis-stress model (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Beck, Alford, Bieling and Segal2000; Lewinsohn et al., Reference Lewinsohn, Joiner and Rohde2001) depressive schemata are organized into dysfunctional beliefs. In the presence of negative life events these attitudes can be activated easily, triggering cognitive distortions in views of the self, the world and the future. Dysfunctional attitudes play a similarly essential role in the development of LSE within Fennell’s model (Fennell, Reference Fennell1997; Fennell, Reference Fennell1998). The severity of dysfunctional attitudes also predicts treatment outcome in depression, while fewer dysfunctional attitudes can predict a better response to anti-depressant therapy (Pedrelli et al., Reference Pedrelli, Feldman, Vorono, Fava and Petersen2008; Sotsky et al., Reference Sotsky, Glass, Shea, Pilkonis, Collins, Elkin and Moyer1991) as well as to cognitive behaviour therapy (Jarrett et al., Reference Jarrett, Minhajuddin, Borman, Dunlap, Segal, Kidner and Thase2012; Sotsky et al., Reference Sotsky, Glass, Shea, Pilkonis, Collins, Elkin and Moyer1991). Dysfunctional attitudes correlate with low self-esteem (Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Reitenbach, Kraemer, Hautzinger and Meyer2017) and CBT interventions addressing LSE also emphasize the change of dysfunctional or negative core beliefs in general (Fennell, Reference Fennell2006; Griffioen et al., Reference Griffioen, van der Vegt, de Groot and de Jongh2017; Kolubinski et al., Reference Kolubinski, Frings, Nikčević, Lawrence and Spada2018; Waite et al., Reference Waite, McManus and Shafran2012). While the relationship between dysfunctional beliefs in general and self-esteem appears to be fundamental during interventions, less research has been done on identifying the types of beliefs associated with LSE. Beliefs related to perfectionism receive the most attention: ‘People will probably think less of me if I make a mistake’ or ‘If I don’t set the highest standards for myself, I am likely to end up a second-rate person’. Transdiagnostic research has shown that maladaptive perfectionism is often manifested in the form of self-critical perfectionism, which can erode explicit self-esteem (Grzegorek et al., Reference Grzegorek, Slaney, Franze and Rice2004; Moroz and Dunkley, Reference Moroz and Dunkley2015; Zeigler-Hill and Terry, Reference Zeigler-Hill and Terry2007), social self-esteem in the long run (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sherry, Mushquash, Saklofske, Gautreau and Nealis2017) or self-esteem connected to body image (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Papay, Webb and Reeve2016) as well.

Emotion regulation

On the one hand, maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies (such as rumination, catastrophizing or self-blame) maintain and increase the effect of depressive symptoms and anxiety (Garnefski et al., Reference Garnefski, Kraaij and Spinhoven2001; Kuster et al., Reference Kuster, Orth and Meier2012; Miklósi et al., Reference Miklósi, Martos, Kocsis-Bogár and Perczel Forintos2011; Neff and Vonk, Reference Neff and Vonk2009; Owens and Rosenberg, Reference Owens, Rosenberg, Owens, Stryker and Goodman2006). Studies based on the cognitive catalyst model (Ciesla et al., Reference Ciesla, Felton and Roberts2011; Ciesla and Roberts, Reference Ciesla and Roberts2007; Sova and Roberts, Reference Sova and Roberts2018) demonstrated that the intensity of rumination can be a predictor of the duration of depressive episodes, and correlates with LSE and dysfunctional attitudes. Self-blame is related to decreased self-esteem and higher levels of depression (Grzegorek et al., Reference Grzegorek, Slaney, Franze and Rice2004; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Galambos and Krahn2014; Moroz and Dunkley, Reference Moroz and Dunkley2015). In Fennell’s cognitive model of LSE, self-criticism is an important element of the vicious circle maintaining LSE (Fennell, Reference Fennell1997; Fennell, Reference Fennell1998). The Self-Regulatory Executive Function model (Wells and Matthews, Reference Wells and Matthews1996) and study results based on this theory (Kolubinski et al., Reference Kolubinski, Marino, Nikčević and Spada2019; Kolubinski et al., Reference Kolubinski, Nikčević, Lawrence and Spada2016) also support that as a result of self-critical rumination, a person’s attention is drawn to the self-critical thoughts that contribute to the maintenance of LSE. On the other hand, adaptive emotion regulation strategies (Garnefski et al., Reference Garnefski, Kraaij and Spinhoven2001) or skills (Fehlinger et al., Reference Fehlinger, Stumpenhorst, Stenzel and Rief2013) may help to improve depressive symptoms and increase self-esteem.

Aims of the study

In our cross-sectional study we aim to understand more specifically what subtypes of dysfunctional attitudes and emotion regulation processes may play a role in maintaining LSE. As can be seen from the summary above, LSE is associated with several psychiatric disorders and transdiagnostic processes, therefore we expected that an explanatory model of LSE would emerge to fit the whole heterogeneous sample properly.

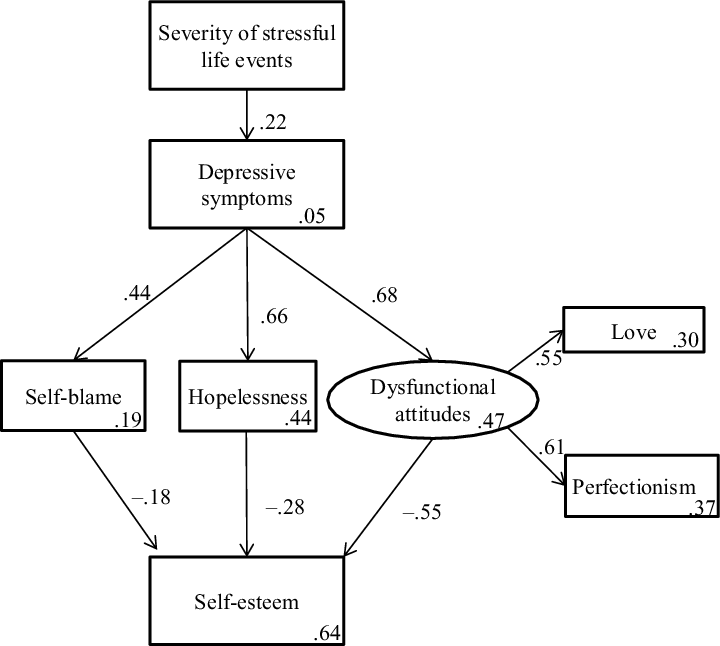

The first aim of the research was to test the fit of the hypothesis model. Our hypothesis model (Fig. 1) is based on the vicious circle of Fennell’s model (Fennell, Reference Fennell1997; Fennell, Reference Fennell1998), in which the following processes are involved in maintaining LSE: effects of stressful life events, depression, anxiety, the activation of dysfunctional beliefs, and self-blame as a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy. However, we supplemented our hypothesis model with rumination based on the ‘cognitive catalyst’ model (Ciesla et al., Reference Ciesla, Felton and Roberts2011; Ciesla and Roberts, Reference Ciesla and Roberts2007; Sova and Roberts, Reference Sova and Roberts2018) and the ‘self-regulatory executive function’ model (Wells and Matthews, Reference Wells and Matthews1996). Figure 1 represents our hypothesis model of LSE, as described above. We assumed that the higher number of stressful life events and the increased value of their subjective severity are associated with an increase in depressive symptoms and a higher level of anxiety. We also expected that higher level of depression leads directly to a lower level of self-esteem, but it also reduces self-esteem indirectly, through the mediating effect of increased dysfunctional attitudes (e.g. seeking approval, seeking love, perfectionism, etc.), self-blame and rumination as maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and hopelessness. Finally, we expected that a high level of anxiety also has a similar effect on self-esteem as depression has, i.e. it leads directly to LSE and indirectly through the processes listed above, as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Hypothesis transdiagnostic model of LSE based on Fennell’s cognitive model. Fit indicators of the model: χ2 (80, n=611)=544.648, p<.001; RMSEA=.097, CFI=.853, TLI=.808.

Another aim of our study was to set up a properly fitted modified transdiagnostic model by considering the fit indices and the theories above, if the hypothesis model does not fit the sample properly.

Method

Study sample and procedure

Six hundred and eleven patients (70.9% women), between the age of 18 and 67 years (mean=32.84 years, SD=10.80) were treated at our highly specialized psychotherapeutic out-patient unit. Patients come to the out-patient clinic from primary and specialist care, mainly for psychotherapeutic treatment, in some cases for diagnostic purposes at their own request or on the recommendation of the referring doctor. Descriptive values and diagnosis groups are shown in Table 1. Inclusion criteria were: anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, serious health anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and other phobias); mood disorders (depression); obsessive-compulsive disorder or psychosomatic disorders. Exclusion criteria were: acute psychotic state or a history of regular alcohol or drug use (based on information collected as part of the socio-demographic data). Individuals with incomplete test results were excluded from the database.

Table 1. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

The study protocol was approved by the Scientific Ethical Committee of Semmelweis University. Participants completed the questionnaires while waiting for their first interview with a clinical psychologist, as part of the initial assessment procedure at the participating clinic. Diagnostic information was obtained during an intake interview conducted by trained or intern clinical psychologists under the supervision of the second author. Diagnoses were established according to ICD-10 (WHO, 2016).

Measures

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale – Hungarian version (RSES-H)

The RSES-H is 10-item scale that measures global self-worth on a 4-point Likert scale – from ‘0’ (strongly disagree) to ‘3’ (strongly agree). There are five reversed and five straightforward items. We used the scale as unidimensional (Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg1965; Sallay et al., Reference Sallay, Martos, Földvári, Szabó and Ittzés2014).

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ)

The CERQ is a self-report measure to evaluate cognitive strategies in emotion regulation, consisting of 36 Likert-type items [from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always)] (Garnefski and Kraaij, Reference Garnefski and Kraaij2007) with nine subscales based on the original factor analysis (Geisler et al., Reference Geisler, Vennewald, Kubiak and Weber2010) and its Hungarian adaptation (Miklósi et al., Reference Miklósi, Martos, Kocsis-Bogár and Perczel Forintos2011). Higher scores represent greater use of the specific strategy: self-blame, rumination, catastrophizing and blaming others as maladaptive strategies. Refocus on planning, positive reappraisal, putting into perspective, positive refocusing and acceptance represent the adaptive strategies. CERQ reference values for a Hungarian healthy sample can be found in the study of Miklósi et al. (Reference Miklósi, Martos, Kocsis-Bogár and Perczel Forintos2011).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

The most widely used self-rated scale, the BDI, was used to measure the severity of depressive symptoms (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock and Erbaugh1961; Kopp and Fóris, Reference Kopp and Fóris1993). Twenty-one questions on a 4-point Likert-scale (0 to 3) evaluate key symptoms of depression (such as mood, pessimism, self-dissatisfaction, self-dislike, suicidal ideas, irritability, indecisiveness, body image change, work difficulty, insomnia, loss of appetite and weight, somatic symptoms, loss of libido, etc.). A higher score correlates with more severe depression.

Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS)

To measure negative predictions for the future (hopelessness), we used the BHS, a self-report inventory designed to measure three major aspects of hopelessness: feelings about the future, loss of motivation, and expectations. The test consists of 20 true or false items; scores above 7 indicate mild suicide risk, and above 9 reflects severe suicide risk (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Weissman, Lester and Trexler1974; Perczel-Forintos et al., Reference Perczel-Forintos, Sallai and Rózsa2010; Szabó et al., Reference Szabó, Mészáros, Sallay, Ajtay, Boross, Udvardy-Mészáros and Perczel-Forintos2016).

Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS)

To measure the intensity of dysfunctional attitudes we used this 35-item self-report questionnaire. The DAS has seven subscales: seeking approval, seeking love, perfectionism, achievement, entitlement, omnipotence and external control/autonomy (Kopp, Reference Kopp1985; Weismann and Beck, Reference Weismann and Beck1979). Six points or more (on a subscale) indicate activation of that scale. Higher scores reflect more strongly believed dysfunctional attitudes.

Paykel Life Events Questionnaire, Hungarian shortened, modified version (PLEQ-H)

The PLEQ-H is a self-report questionnaire based on the Paykel Stressful Life Events Questionnaire (Paykel et al., Reference Paykel, Prusoff and Uhlenhuth1971; Tringer and Veér, Reference Tringer and Veér1977). The PLEQ-H is a 28-item scale that lists different stressful life events such as death of a family member or close friend, being a survivor of violence, change of residence or divorce. Patients indicate whether they have experienced each event, and rate how stressful they found it on a 6-point Likert scale (0–5). We examined two indicators: the total number and the average severity of stressful life events.

Cumulative anxiety indicator

To measure the level of anxiety, based on the Hungarian norms of STAI-S we used a three-level anxiety indicator, where 0 means no anxiety or a low level of anxiety, and 2 means a high level of anxiety (Sipos and Sipos, Reference Sipos, Sipos and Spielberger1978; Spielberger et al., Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch and Lushene1970). This was necessary because the database contained only a three-level anxiety index calculated from STAI-S results in the case of some patients (n=46).

Statistics

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24. There were no missing values in the sample as patients with missing values in the test results were excluded from the analysis. To test the possible mediational effects of cognitive emotion regulation strategies and dysfunctional attitudes on the relationship between depressive symptoms and self-esteem structural equation modelling (SEM), path analysis in AMOS 18 was used. As Hu and Bentler (Reference Hu and Bentler1999) and MacCallum and Austin (Reference MacCallum and Austin2000) suggested, a model fit was assessed by the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). A good fit is indicated by values greater than or equal to .95 for the CFI and the TLI, and less than or equal to .05 for RMSEA. A moderate fit is indicated by values between .05 and .08 for RMSEA.

Results

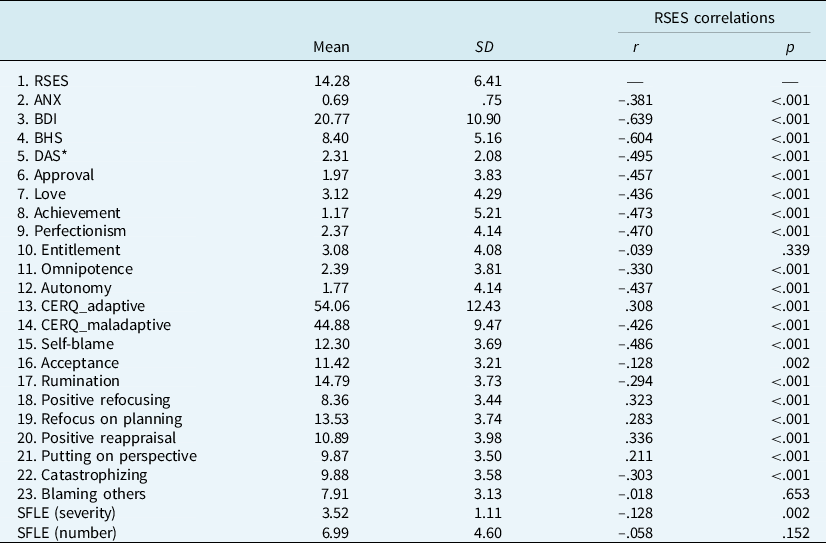

Means and standard deviations for the measures of interest are shown in Table 2. All clinical scales indicated a critical value: mild anxiety (ANX), moderate depression (BDI), a high level of negative predictions/hopelessness (BHS), and very low self-esteem (RSES) were measured. On average, 2.31 (SD DAS=2.07) dysfunctional attitudes reached the 6-point limit; subscales with the highest value in the total sample were: seeking love (Mean=3.12, SD=4.29), entitlement (Mean=3.08, SD=4.08), and omnipotence (Mean=2.39, SD=3.81). Compared with a healthy Hungarian control sample (Miklósi et al., Reference Miklósi, Martos, Kocsis-Bogár and Perczel Forintos2011), maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies (rumination, catastrophizing, self-blame, blaming others) were increased (Mean=44.88, SD=9.47). In contrast, adaptive strategies (positive refocusing, refocus on planning, positive reappraisal) were decreased (Mean=54.06, SD=12.43).

Table 2. Means and standard deviations for the measure, correlations with RSES

SD, standard deviation; r, Pearson’s correlation; ANX, Cumulative Anxiety Indicator (0–2); BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BHS, Beck Hopelessness Scale; RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; DAS*, numbers of activated dysfunctional attitudes; CERQ, Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; SFLE, stressful life events

The bivariate correlations between different scales and self-esteem are also shown in Table 2. There was a strong negative correlation between self-esteem and depressive symptoms (r=–.639) as well as self-esteem and hopelessness (r=–.604). Moderate correlations were shown between self-esteem and the elevated number of activated dysfunctional attitudes (r DAS*=–.495), and also between the elevated level of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and self-esteem (r=–.426), especially self-blame (r=–.486).

SEM analysis of the transdiagnostic model of LSE

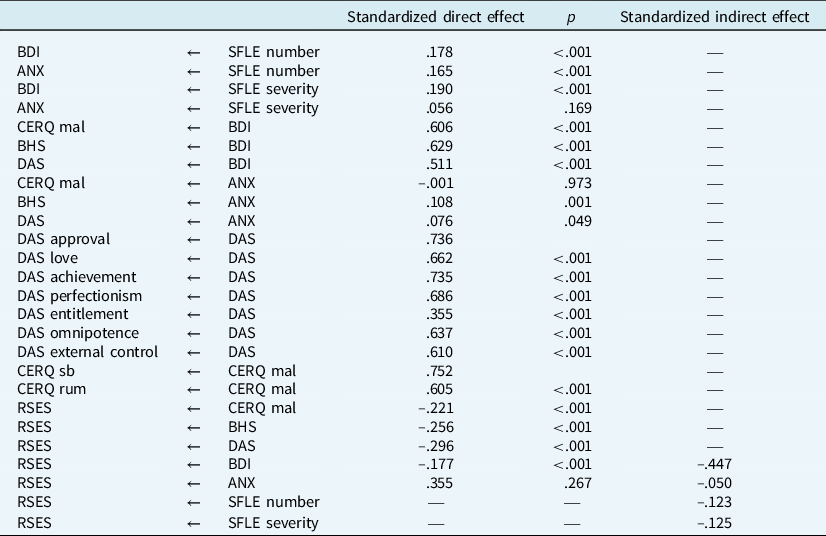

SEM pathway analysis implemented through AMOS Graphics 18 was used to test the hypothesis transdiagnostic model of LSE (Fig. 1). The hypothesis model did not fit the data [χ2 (80, n=611)=544.648, p<.001; RMSEA=.097, CFI=.853, TLI=.808]. The variables in the model accounted for 53% of the variance in self-esteem level (R 2=.53). All standardized regression weights estimated for the hypothesis model with p-values and the standardized indirect (mediated) effects of variables on self-esteem are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Regression weights in the hypothesis model

ANX, Cumulative Anxiety Indicator; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BHS, Beck Hopelessness Scale; CERQ mal/sb/rum, Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire maladaptive strategies/self-blame/rumination; DAS, Dysfunctional Attitude Scale; RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; SFLE, stressful life events.

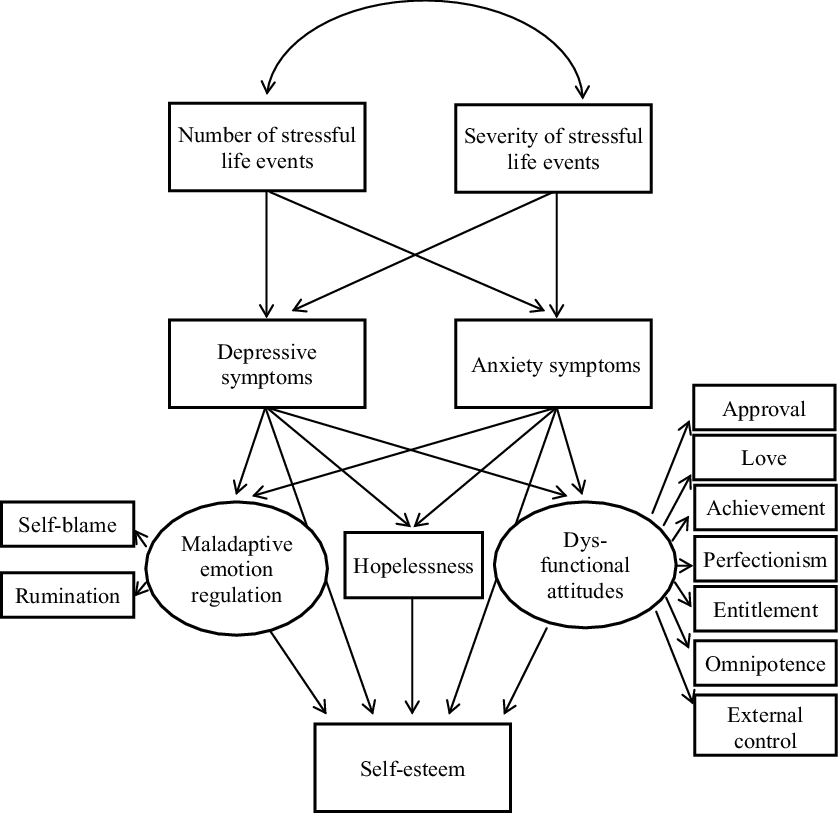

From the hypothesis model, taking into account the fit indices (p-values, estimated regression weights, direct and indirect effects), we created a modified transdiagnostic model that fits the sample appropriately (Fig. 2). Based on fit indicators, anxiety was removed from the model, because it has a significant direct effect on BHS alone, although the effect size was weak (β=.10). The indirect effect of anxiety on self-esteem was low (Table 3), and the fit of the model was greatly impaired. Similarly, the number of life events showed only a weak correlation directly with depression and indirectly with low self-esteem. In the case of the latent variable showing dysfunctional attitudes, the variables with low factor weights were removed from the model in multiple steps, so that eventually only perfectionism and seeking love remained in the model. Due to the exclusion of poorly matched variables from the model, the direct effect of depression on self-esteem became non-significant (β=–.078, p=.243). Regarding maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, the direct effect of rumination was significant in the latent variable (β=–.604, p<.001, λ=.162) and the latent variable also had significant impact on LSE (β=–.221, p<.001). However, the fit indices still were not good enough [χ2 (17, n=611)=105.825, p<.001; RMSEA=.092, CFI=.941, TLI=.902; adj R 2=.623] even after removing poorly fitting variables above. By removing rumination from the model, the fit indicators improved and the explained variance of LSE increased, as well.

Figure 2. Modified transdiagnostic model of LSE. The standardized estimates are shown in the figure, p-values are <0.001 in all cases. Fit indicators of the model: χ2 (12, n=611)=76.471, p<.001; RMSEA=.080, CFI=.950, TLI=.913.

The modified transdiagnostic model produced moderate fit to the data [χ2 (12, n=611)=76.471, p<.001; RMSEA=.080, CFI=.950, TLI=.913]. The variables in the model accounted for 63.6% of the variance in self-esteem level (adj R 2=.636). The standardized beta coefficients are shown in Fig. 2. All coefficients estimated for the measurement model and the estimates of error variances were significant (p<.001). Severity of stressful life events (SFLE_severity) has a relatively weak effect on self-esteem (β=–.141), while depression (BDI) showed a strong negative indirect effect on self-esteem (β=–.637). Overall, our results suggest that the severity of depression and stressful life events indirectly, while self-blame (β=–.18), hopelessness (β=–.28), and dysfunctional attitudes related to seeking love and perfectionism (β=–.55) directly contribute to the maintenance of LSE.

Discussion

In our cross-sectional clinical study, we were interested in what transdiagnostic cognitive processes may contribute to the maintenance of LSE. Several studies have been conducted to examine the relationship between LSE, depression and anxiety (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Galambos and Krahn2014; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Galambos and Krahn2016; Orth et al., Reference Orth, Robins, Meier and Conger2016; Sowislo and Orth, Reference Sowislo and Orth2013). Other research results show that this relationship on the one hand, is influenced by dysfunctional beliefs (Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Reitenbach, Kraemer, Hautzinger and Meyer2017; Moroz and Dunkley, Reference Moroz and Dunkley2015; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sherry, Mushquash, Saklofske, Gautreau and Nealis2017; Zeigler-Hill and Terry, Reference Zeigler-Hill and Terry2007) and on the other hand, by maladaptive emotion regulation strategies such as rumination (Ciesla et al., Reference Ciesla, Felton and Roberts2011; Kuster et al., Reference Kuster, Orth and Meier2012; Sova and Roberts, Reference Sova and Roberts2018) and self-blame (Grzegorek et al., Reference Grzegorek, Slaney, Franze and Rice2004; Moroz and Dunkley, Reference Moroz and Dunkley2015).

Taking into account the studies above and the main cognitive theories about LSE into account, our hypothesis model (Fig. 1) was based on Melanie Fennell’s cognitive model of LSE (Fennell, Reference Fennell1997), the cognitive catalyst model (Ciesla et al., Reference Ciesla, Felton and Roberts2011; Ciesla and Roberts, Reference Ciesla and Roberts2007; Sova and Roberts, Reference Sova and Roberts2018) and the S-REF model (Wells and Matthews, Reference Wells and Matthews1996). One of the objectives of the research was to test the hypothesis model by SEM pathway analysis on a heterogeneous clinical sample. In case of improper fit, the second aim was to set up a properly fitting model.

The transdiagnostic approach of LSE

Our hypothesis model (Fig. 1) did not fit the sample well; therefore, modifications have been made based on fit indicators. The emerged explanatory model of LSE has good fitting indicators on a moderately large (n=611) heterogeneous clinical sample with the main diagnosis of various anxiety disorders (such as panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, serious health anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and other phobias), depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder and psychosomatic disorders. The fact that we found a well-fitting model with strong explanatory power (R 2=.65) seems to support the assumption that LSE can be interpreted as a transdiagnostic phenomenon maintained by transdiagnostic mechanisms in accordance with the literature (e.g. APA, 2013; Fennell, Reference Fennell1998; Sowislo and Orth, Reference Sowislo and Orth2013; Zeigler-Hill, Reference Zeigler-Hill2011).

We hypothesized that the number and the severity of stressful life events contribute to an elevated level of anxiety and depressive symptoms leading to the development and maintenance of LSE as reflected in Fennell’s model (Fennell, Reference Fennell1997). Our results supported the impact of the severity of stressful life events on the development and maintenance of symptoms contributing to LSE. However, the number of stressful life events did not fit the model, which suggests that it may be the subjective evaluation of life events, and not the number of them, that can lead directly to symptom formation.

We expected that depressive and anxiety symptoms would lead to LSE directly, and also through cognitive processes such as different types of dysfunctional attitudes, hopelessness, self-blame and rumination. Although anxiety symptoms are related to self-esteem (r=–.381, p<.001), the direct (β=.355, p=.267) and indirect (β=–.050) effects of anxiety on LSE were not found to be significant within the emerged explanatory model where the impact of anxiety was manifested on its own, that is, without the effect of depressive symptoms and mediating cognitive processes. The scale used to assess anxiety in our study (STAI-S) measures state-anxiety, i.e. how a person feels during a perceived threat. Based on our results, we assume that this type of anxiety might not have a maintenance role in LSE.

The correlations between LSE and depressive symptoms – including cognitive, somatic, and emotional symptoms – seem to be strong (r=–.639); however, in the final model the direct effect of depression on self-esteem became non-significant (β=–.078, p=.243). Our results suggest that the factors which lead directly to the maintenance of LSE are the elevated level of seeking love and perfectionism, hopelessness, and self-blame as maladaptive cognitive processes associated with depression. Thus, the relationship between depression and self-esteem is influenced by these mediating factors.

Self-blame in the transdiagnostic model means how a person tries to handle emotionally difficult situations. In a stressful or challenging situation, he/she primarily criticizes himself/herself and believes that the primary cause of the difficulty is his/her inadequacy. Due to activated dysfunctional beliefs, individuals think that their acceptability and lovability depends on whether they handle situations perfectly and that everyone loves them. However, it is impossible to meet these unrealistic expectations, so they become hopeless. Which in this case may mean that: ‘my difficulty is not just about the situation, I am incompetent, I am not lovable and this will not change’. Our findings are in accordance with earlier transdiagnostic studies (Grzegorek et al., Reference Grzegorek, Slaney, Franze and Rice2004; Moroz and Dunkley, Reference Moroz and Dunkley2015; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sherry, Mushquash, Saklofske, Gautreau and Nealis2017; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Papay, Webb and Reeve2016) which demonstrate that perfectionism combined with self-blame can turn into harmful self-critical perfectionism.

We expected rumination to be an important mediating factor in the transdiagnostic model of LSE, as well. Although rumination proved to play a significant role in the latent variable of maladaptive emotion regulation (β=–.604, p<.001, λ=.162), and this latent variable proved to be significant in the maintenance of LSE (β=–.221, p<.001) (Table 3), surprisingly, rumination worsened the fit of the model and the explained variance of LSE. A possible explanation of this finding is that rumination is a type of worry. According to our results, anxiety in general appears to be less important in the maintenance LSE than the processes that belong to the depressive symptoms. Rumination as a maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategy reflects being stuck in the flow of thoughts where the person is constantly analysing him/herself, and his/her thoughts and feelings over and over again. It is possible that rumination does not fit into the model because it does not clearly contribute to LSE in individuals for whom rumination is not associated with self-judgement.

In sum, it seems from the described transdiagnostic model that perceived severity of stressful life events and depression can damage self-esteem in various mental disorders via the activation of dysfunctional beliefs about perfectionism and seeking love, hopelessness and self-blame.

Limitations

The results of this model must be interpreted with caution due to potential limitations. First, as mentioned earlier, this transdiagnostic model of LSE shows only a cross-sectional picture of the relationship between depressive symptoms, self-esteem and mediator variables. A reciprocal model would describe this transdiagnostic process more precisely as suggested by Orth et al. (Reference Orth, Robins, Meier and Conger2016), Sowislo and Orth (Reference Sowislo and Orth2013) or Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Galambos and Krahn2014). Direct testing of models which explore the development of psychological phenomena such as LSE is primarily possible by longitudinal studies by follow-up design, as relationships invariably unfold over time. However, a cross-sectional design can still provide useful information for establishing therapies and new interventions. Furthermore, the publication of these types of studies helps to develop common knowledge, while the results from longitudinal studies usually require decades of work.

Clinical implications

Therapies based on Fennell’s model proved to be effective in the improvement of self-esteem. However, the clinical sample size in intervention studies seems to be very limited even in the case of a meta-analysis (Kolubinski et al., Reference Kolubinski, Frings, Nikčević, Lawrence and Spada2018), due to the fact that the everyday practice of therapeutic care often does not meet the scientific methodological requirements. In terms of clinical implications, the transdiagnostic model seems to support that the vicious circle of Fennell’s model is also valid in a moderately large, heterogeneous clinical sample. Only the role of anxiety was not substantiated, but the role of hopelessness (related to negative predictions), self-blame and dysfunctional beliefs appear to have a maintaining role in LSE in accordance with Fennell’s cognitive model.

On the other hand, the transdiagnostic model highlights several factors that contribute to the maintenance of LSE. Interventions targeting these factors can expand the therapeutic toolkit to address low self-esteem. For instance, perfectionism-focused CBT has been shown to be effective in improving self-esteem while reducing symptoms of eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and anxiety (Egan et al., Reference Egan, van Noort, Chee, Kane, Hoiles, Shafran and Wade2014; Handley et al., Reference Handley, Egan, Kane and Rees2015; Kothari et al., Reference Kothari, Barker, Pistrang, Rozental, Egan, Wade and Shafran2019). Hopelessness and self-blame can also be decreased by problem-solving therapy (Shanbehzadeh et al., Reference Shanbehzadeh, Tavahomi, Zanjari, Ebrahimi-Takamjani and Amiri-Arimi2021) or by the improvement of non-judgemental attitude via MBCT (Ebrahiminejad et al., Reference Ebrahiminejad, Poursharifi, Bakhshiour Roodsari, Zeinodini and Noorbakhsh2016) thereby leading to the improvement of self-esteem.

Future studies are needed in order to investigate the validity of this transdiagnostic model in other psychiatric conditions such as addictions and eating disorders. A longitudinal study would be appropriate to understand the factors involved in the development of LSE and the role of rumination and anxiety.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the co-operation of all the colleagues of the Department of Clinical Psychology, Semmelweis University, for the assistance in data collection. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their observations, which encouraged us to rethink some essential methodological questions. Special thanks is due to Melanie Fennell who carefully read through the whole manuscript and corrected it with her invaluable constructive advices and comments. It was a really rewarding experience to exchange ideas with her about such an important topic in psychotherapy as LSE. Finally, we are grateful to all the patients who participated in the study.

Financial support

The research was financed by the Higher Education Institutional Excellence Programme of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology in Hungary, within the framework of the Neurology thematic programme of the Semmelweis University, FIKP/2018.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethics statements

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Ethical permission was obtained from the scientific ethical commission of the university. All participants provided an informed consent.

Data availability

Raw data were generated at the out-patient unit of the Clinical Psychological Department of Semmelweis University. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (D.P.-F.) on request.

Author contributions

Szilvia Kresznerits: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (lead), Funding acquisition (equal), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (equal), Validation (equal), Visualization (equal), Writing-original draft (equal), Writing-review & editing (equal); Sándor Rózsa: Conceptualization (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Validation (equal); Dóra Perczel-Forintos: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Funding acquisition (lead), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Software (lead), Supervision (equal), Validation (equal), Writing-review & editing (equal).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.