Alcohol consumption is one of the leading risk factors for death and disability worldwide. Reference Zhang, Xue, Wu, Zhang, Hou and Xiang1 Many policies have been introduced across the world to reduce alcohol-related harm. 2 These policies are mainly implemented as part of national alcohol plans for particular countries. Reference Zhang, Xue, Wu, Zhang, Hou and Xiang1 However, some types of alcohol policy, identified here as short-term policies, are implemented occasionally as a strategic response to a temporary challenge or a particular situation for a specific period. These policies have not necessarily been put into action by most countries. This paper aims to discuss contexts in which these short-term policies are applied, using examples from countries in which members of the International Society of Addiction Medicine’s New Professionals Exploration, Training & Education Committee (ISAM-NExT) have experience. The paper then highlights the need for impact measurement and empirical evaluation of the public health effects of such policies. It also calls for a global exchange of experiences to better understand and address the challenges such as those posed by the alcohol industry.

Method

In addition to fixed national alcohol policies, some countries implement short-term policies – these are temporary measures or regulations enacted by the national or local government to manage or control the consumption, sale and distribution of alcoholic beverages for a limited period. They are made to address specific issues or events, such as public health crises (as in the COVID-19 pandemic), holidays or mass gatherings, where alcohol might play a significant role in causing public disorder. Short-term alcohol policies may act on top of existing regulations.

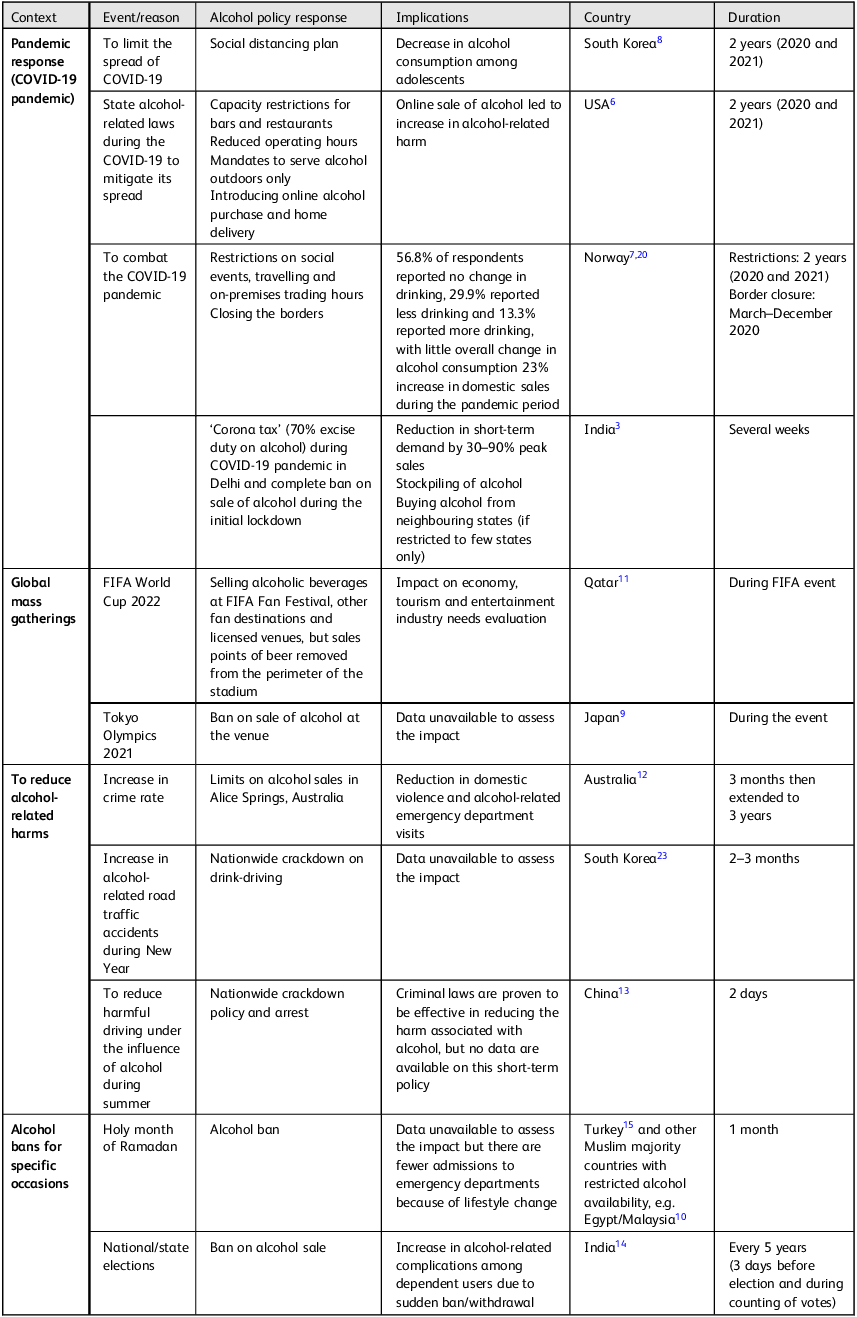

This definition of short-term policies was shared with ISAM-NExT Committee members, and they were asked whether such policies are implemented in their countries of expertise and for what reason. After 1 month, responses were received from 18 countries, ten of which were included in our study (USA, Norway, South Korea, India, Qatar, Japan, China, Australia, Turkey and Indonesia; Table 1). Members from four countries had no experience with such policies, while four reported on non-applicable ones. The ISAM-Next Committee is a global platform for early-career addiction medicine professionals that currently has 30 early-career addiction professional members from 22 countries.

Table 1 A snapshot of the contexts in which short-term alcohol policies are implemented

We used thematic analysis to analyse the responses, identifying common contexts with no presumptions.

Results

Four contextual reasons were identified for implementing short-term policies: unplanned in response to unexpected events (e.g. pandemic response); planned in response to expected short-term events (e.g. global mass gatherings); planned to mitigate harm (e.g. reducing alcohol-related harms); and planned in response to longer-term systemic events (e.g. alcohol bans during specific occasions).

Pandemic response

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many short-term alcohol policies were implemented around the world Reference Murthy and Narasimha3,4 in line with World Health Organization’s recommendation of limiting drinking to one drink per day during the pandemic. Despite some studies Reference Murthy and Narasimha3 the impact needs to be further explored.

Certain countries prohibited the sale of alcohol during lockdown periods, whereas others classified it as a necessity, leading to various global challenges. Reference Murthy and Narasimha3 For example, Australia temporarily relaxed liquor licensing, allowing restaurants, cafes and small bars to sell alcohol for takeaway and delivery. As a result, in New South Wales, Australia, alcohol consumption increased, resulting in increased psychological stress, domestic violence and child abuse. Reference Colbert, Wilkinson, Thornton and Richmond5 Similarly, USA home delivery led to increased alcohol-related harm. Reference Grossman, Benjamin-Neelon and Sonnenschein6

In Norway, for instance, little change in alcohol consumption was observed in the 3 first months after extending the provisions of the Infection Control Act in March 2020, with restrictions on social events, travel and on-premises trading hours. Reference Bramness, Bye, Moan and Rossow7 Over half of responders in a study from June to July 2020 reported no change in drinking, one-third reported less drinking and only 13% reported increased consumption. Those with a low past-year consumption drank less, whereas those with a initially high consumption drank more. Reference Bramness, Bye, Moan and Rossow7 On the other hand, in South Korea, social distancing and school closures during the pandemic notably reduced consumption among adolescents owing to decreased peer pressure. Reference Jeong8

Global mass gatherings

Linking both the COVID-19 pandemic and global mass gatherings, some countries had to apply short-term policies to enable them to host such gatherings during the pandemic. Despite the norm, alcohol-containing beverages were forbidden in the Olympic villages during the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. Reference McCurry9 There are no available data to assess the impact of this particular tactic. However, in countries in which alcohol is typically banned or highly restricted, such as Muslim majority countries (MMCs), Reference Al-Ansari, Thow, Day and Conigrave Katherine10 short-term policies are often applied to the availability and consumption of alcohol. For example, Qatar implemented a short-term policy on easing the restrictions of alcohol availability and consumption when it hosted football’s FIFA World Cup in 2022. Reference Dun and Rachdi11 The impact is not clear, as many of the fans came from neighbouring MMCs with a culture of limited exposure to alcohol consumption.

To reduce alcohol-related harms

In some countries, short-term alcohol restrictions are implemented as a response to increased alcohol-related crime in a specific region. Australia, for instance, implemented alcohol restrictions in Alice Springs for an initial period of 3 months, then extended to 3 years. This approach resulted in a reduction in crime but it is not yet considered an evidence-based intervention. Reference Morse and Robinson12

Alcohol-related motor vehicle accidents and injuries have a global impact and so enforcing criminal laws effectively reduces these harms. In China, a 2-day nationwide crackdown on drink-driving resulted in the arrest of 17 000 individuals for driving under the influence of alcohol. 13 It is vital to investigate how effective this sharp 2-day policy has been for it to be considered for implementation in other countries.

Alcohol bans for specific occasions

Transient policies are also used on occasions where alcohol sales and/or consumption is banned for a defined period. An example of this is the ban on alcohol sales in India that starts 3 days before national and state-level elections (once every 5 years) and continues during the vote tallying period. Reference Narasimha, Mukherjee, Shukla, Benegal and Murthy14 Although the socioeconomic impact of election-period bans has not been studied, the evidence for harm in dependent users accumulates. Reference Narasimha, Mukherjee, Shukla, Benegal and Murthy14 There are increased cases of severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome and presentations to emergency departments, Reference Narasimha, Mukherjee, Shukla, Benegal and Murthy14 as well as an increase in illicit liquor sales. The risk of consumption of illegally produced alcohol and associated health hazards is also elevated. Reference Narasimha, Mukherjee, Shukla, Benegal and Murthy14

On the other hand, the adverse effects are not the same when a transient ban is implemented in an MMC population during a religious period such as Ramadan. Reference Pekdemir, Ersel, Yilmaz and Uygun15 Limited data show evidence of decreased admissions to emergency departments. Reference Pekdemir, Ersel, Yilmaz and Uygun15 This can be explained by the pre-existing religious restrictions and stigma surrounding alcohol availability and consumption in this context. Reference Al-Ansari, Thow, Day and Conigrave Katherine10

Discussion

Short-term policies and the global alcohol industry

The global alcohol industry is known for hunting opportunities to influence alcohol policy-making in favour of its own interests rather than public health. Reference Casswell, Callinan, Chaiyasong, Cuong, Kazantseva and Bayandorj16 In the contexts discussed above, there are some gaps that the alcohol industry might use to strengthen its presence.

For example, the industry challenged Reference Huckle, Parker, Romeo and Casswell17 the implementation of short-term policies during COVID-19, as its strong online and social media presence both encouraged people to buy alcohol online and benefitted the industry owing to limited regulation of online sales. Reference Radoš Krnel, Levičnik, van Dalen, Ferrarese and Tricas-Sauras18

Mass gatherings such as the FIFA World Cup and the Olympic Games often become targets for the alcohol industry, which sponsors events and shapes alcohol policies, from availability and advertising to serving intoxicated individuals. Reference Hastings, Brooks, Stead, Angus, Anker and Farrell19 This influence challenges host countries’ ability to enforce short-term alcohol policies effectively. For instance, despite the UK’s extensive experience, the industry’s tactics to circumvent restrictions on alcohol advertising have highlighted the country’s lack of self-regulation in marketing. Reference Hastings, Brooks, Stead, Angus, Anker and Farrell19 Addressing these issues is crucial for better managing the industry’s impact on alcohol policies during such significant events.

Although no information is available regarding the effects of the alcohol ban during the Tokyo Olympics Reference McCurry9 in 2021 and Beijing Winter Olympics in 2022, investigating approaches like this may provide new ways to address the influence of the alcohol industry during global events.

Qatar was the first MMC to host the FIFA World Cup as a global event. This presented challenges both for the alcohol industry, which has a strong reputation for sponsoring the World Cup, and for Qatar as a country with alcohol restriction/prohibition. Reference Al-Ansari, Thow, Day and Conigrave Katherine10 Highlighting the challenges posed to existing policies on alcohol in Qatar and how the country adapted to host this global event is crucial. Reference Dun and Rachdi11 This is particularly relevant as FIFA looks to expand its events into Islamic countries such as Saudi Arabia. Moreover, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Greece are contemplating a collaborative proposal for hosting the 2030 men’s World Cup. Reference Dun and Rachdi11

European countries tend to have stricter regulations and policies on the import of alcohol compared with MMCs. During the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing domestic sales could be seen after border closures in Norway. Reference Leifman, Dramstad and Juslin20 In addition to weak or absent alcohol policies, many Middle Eastern countries, plagued by war and government instability, have weak or non-existent border protections or taxes. Reference Al-Ansari, Thow, Day and Conigrave Katherine10,Reference Al Ansari, Dawson and Conigrave21 This creates opportunities for the global alcohol industry to use short-term policies to exploit these ‘dry’ regions as new markets, distributing alcohol legally or illegally.

A further concern that needs to be addressed is whether some of these policies might be made by the alcohol industry itself. For example, the Korean Alcohol Research Foundation was established by the alcohol industry in 2000. 22 One notable initiative is the ongoing Stop Drink Driving Campaign, which began in 2002 and utilises booklets, posters and advertisements to raise awareness. 22 Sometimes raising awareness can include the national short-term crackdown policies on drink-driving. Reference Gwangmin23

Need for improved impact measurement

To aid policymakers and service providers in crafting effective short-term alcohol policies, research on their impacts must be current, consistent and uniform. It is essential to balance the targeted and unintended outcomes of these policies by investing in treatment services and managing supply and demand reduction efforts. Reference Morse and Robinson12 For example, a policy might achieve the targeted outcome that it was designed for, such as crime reduction in Alice Springs, Australia, Reference Morse and Robinson12 but it might also have unwanted health outcomes, such as the severe complications in alcohol-dependent individuals observed during election-period bans on alcohol sales in India. Reference Narasimha, Mukherjee, Shukla, Benegal and Murthy14 Balancing the positive and negative impacts of policies needs careful planning and consideration of the context in which they are implemented. There has been some reported evidence on outcomes at a national level in some countries, Reference Morse and Robinson12 but this is considered to be soft data. Therefore, it is essential to build on existing experience by studying the impact of short-term alcohol policies precisely and exchanging those details between the global community. This is particularly important because the World Health Organization’s global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol emphasises national alcohol policies with a long-term focus. 2 Short-term policies have not been explicitly included in those indicators or recommendations.

Countries’ differing policies lead to varied experiences. Measuring their impact and sharing insights can enhance policy effectiveness and understanding. For instance, studies might track health outcomes such as alcohol-related hospital visits, injuries, poisonings and mortality rates, or assess social and behavioural effects by analysing changes in alcohol-related crimes, drink-driving incidents and public disorder.

In conclusion, short-term alcohol policies complement national strategies for specific situations and durations. These policies are applied in contexts such as pandemic response or global mass gatherings and vary widely in their outcomes. The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, emphasised the need for rapid decision-making and short-term fast-acting policies.

There is a need to achieve an equilibrium between the targeted and unwanted outcomes of these policies. This can lead into an evidence-based response where a balance is made between investing in treatment and services available and the supply and demand reduction. Therefore, drawing parallels between similar contextual factors globally where short-term alcohol policies are implemented can help in advancing the process of preparedness for a safe-for-all implementation and so investing in the benefits that these policies are designed for.

Questioning the alcohol industry’s influence and benefits highlights the importance of focusing on impact measurement and global knowledge exchange. This is vital for countries with limited policies on alcohol, such as those that ban alcohol consumption on religious grounds.

Establishing a global database for short-term alcohol policies and standardising evaluation metrics can support international collaboration, enhance data sharing, and strengthen policy adaptation and knowledge exchange.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Author contributions

The study was conceived and design designed by B.A.-A., V.L.N. and R.B.; all authors were involved in acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and reviewing the article and approval of the final version.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.