BACKGROUND

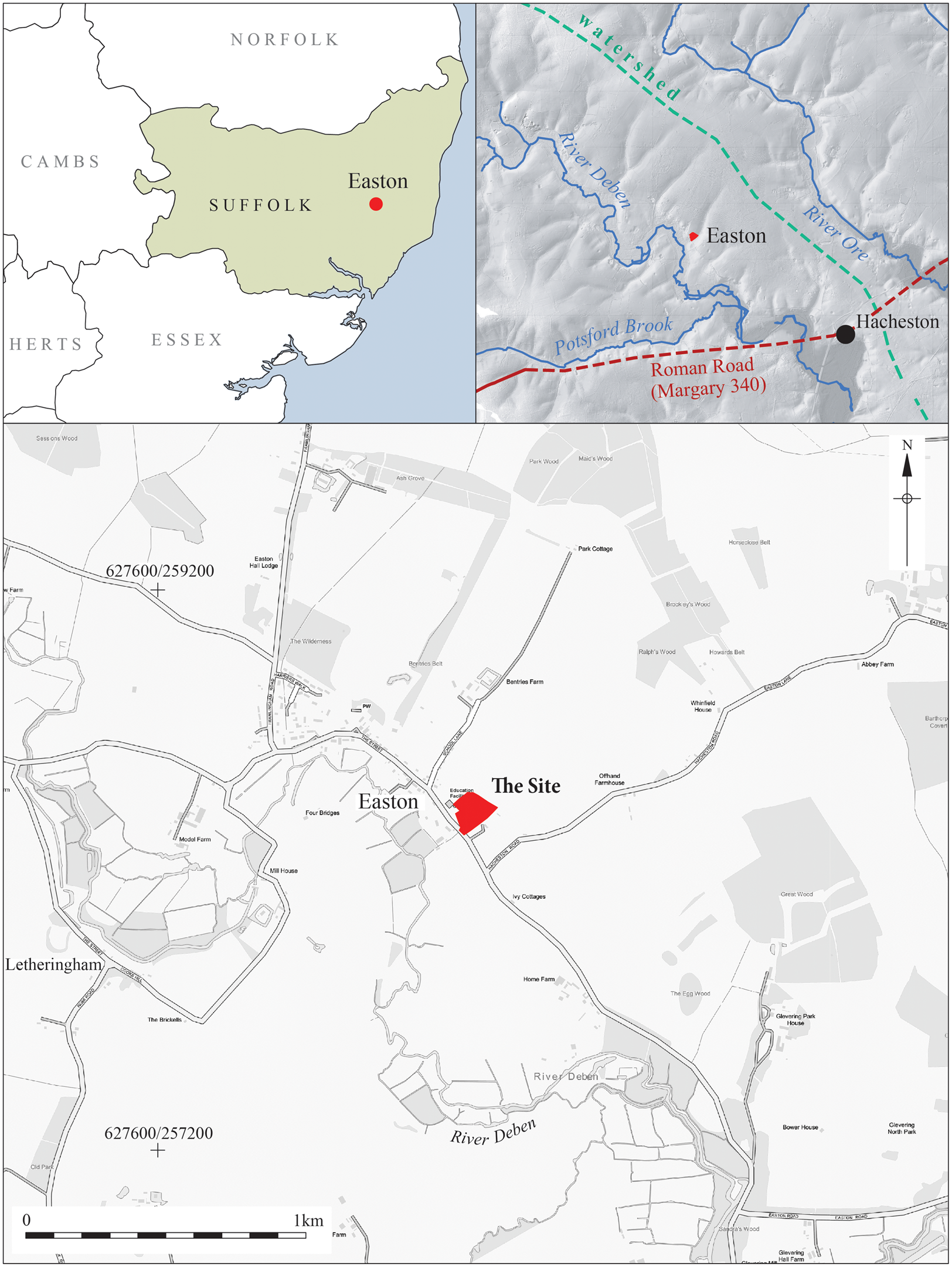

An archaeological excavation was carried out by Pre-Construct Archaeology on land east of Easton Primary School, The Street, Easton, Suffolk (centred on NGR TM 2873 5841) between 4 October and 9 November 2016 (Suffolk Historic Environment Record (SHER) Parish Code ETN 023) (fig. 1). The investigation was commissioned by CgMs Consulting on behalf of Hopkins and Moore Developments Ltd, in response to a planning condition attached to construction of 14 new homes; its aim was to record archaeological remains prior to development.

FIG. 1. Site location.

One late Iron Age pit contained an unusual bronze handle, most likely from a jug, the form of which appears to be unique in Britain. This vessel handle is the focus of this paper. A description of the other significant results of the excavation will appear in Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History.Footnote 1 Full details of the project, together with complete specialist reports and catalogues, can be found in the Archive Report,Footnote 2 available at SHER and downloadable from the Archaeology Data Service website.Footnote 3 The site archive will be deposited at Suffolk County Council Archaeology Store.

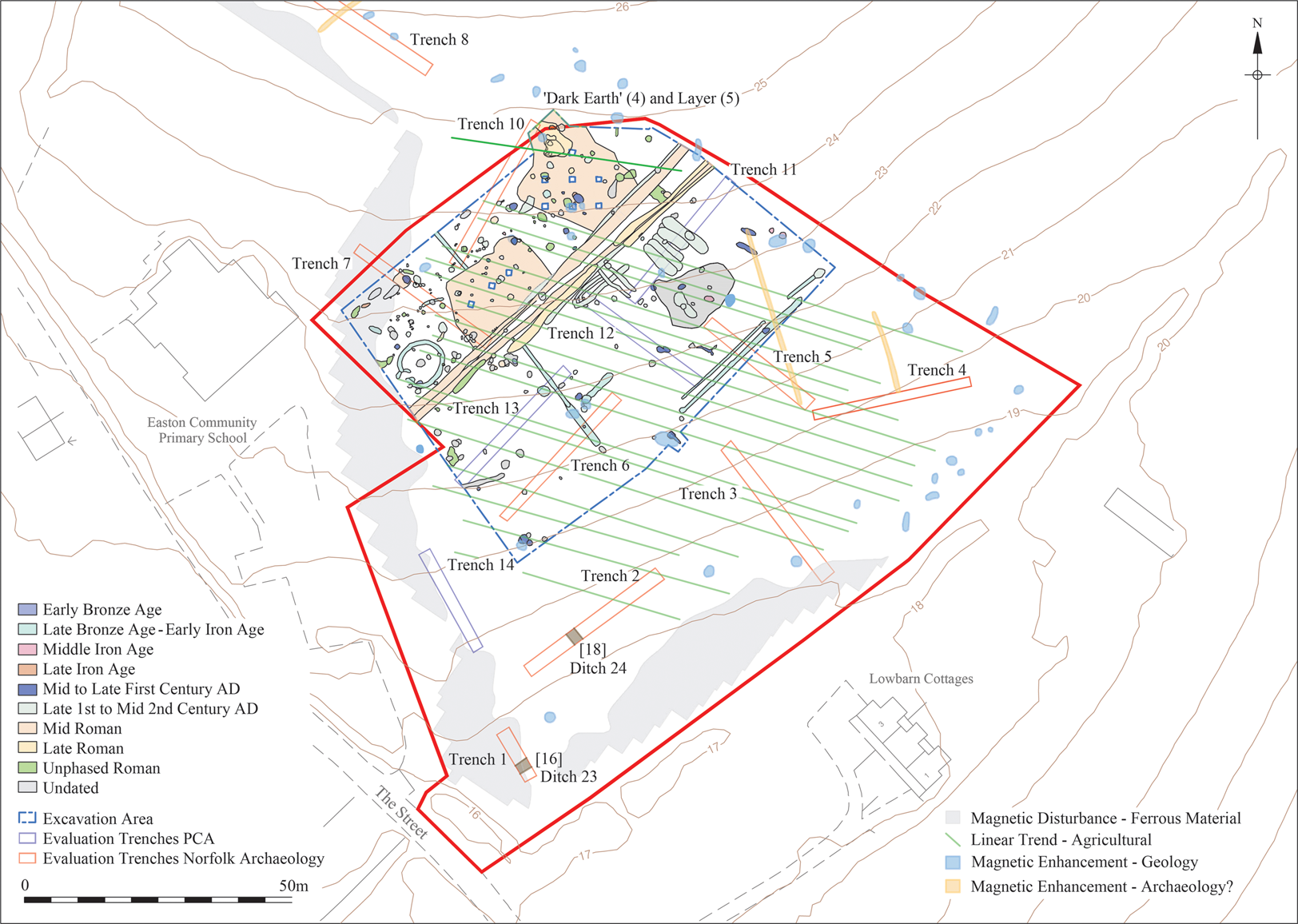

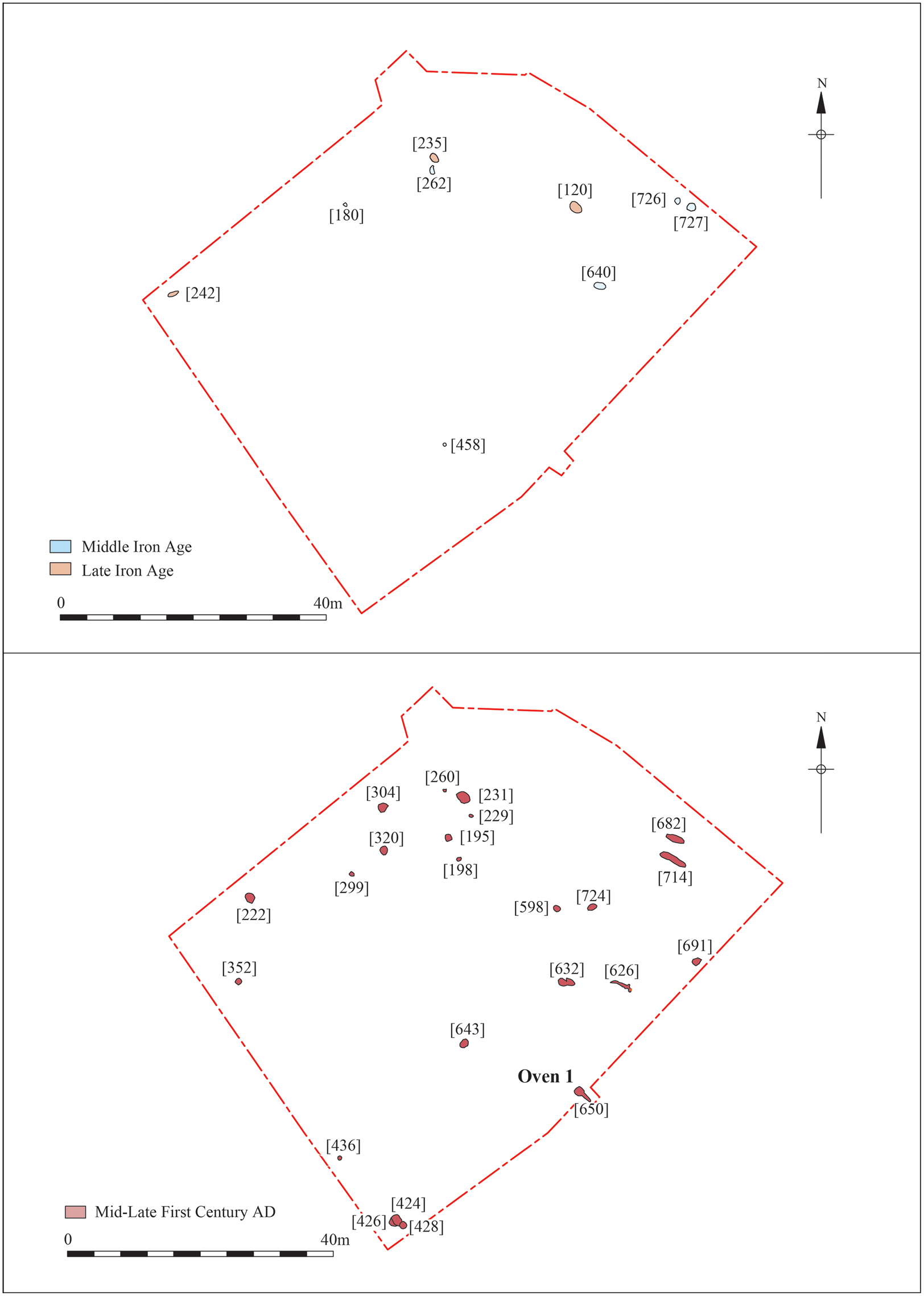

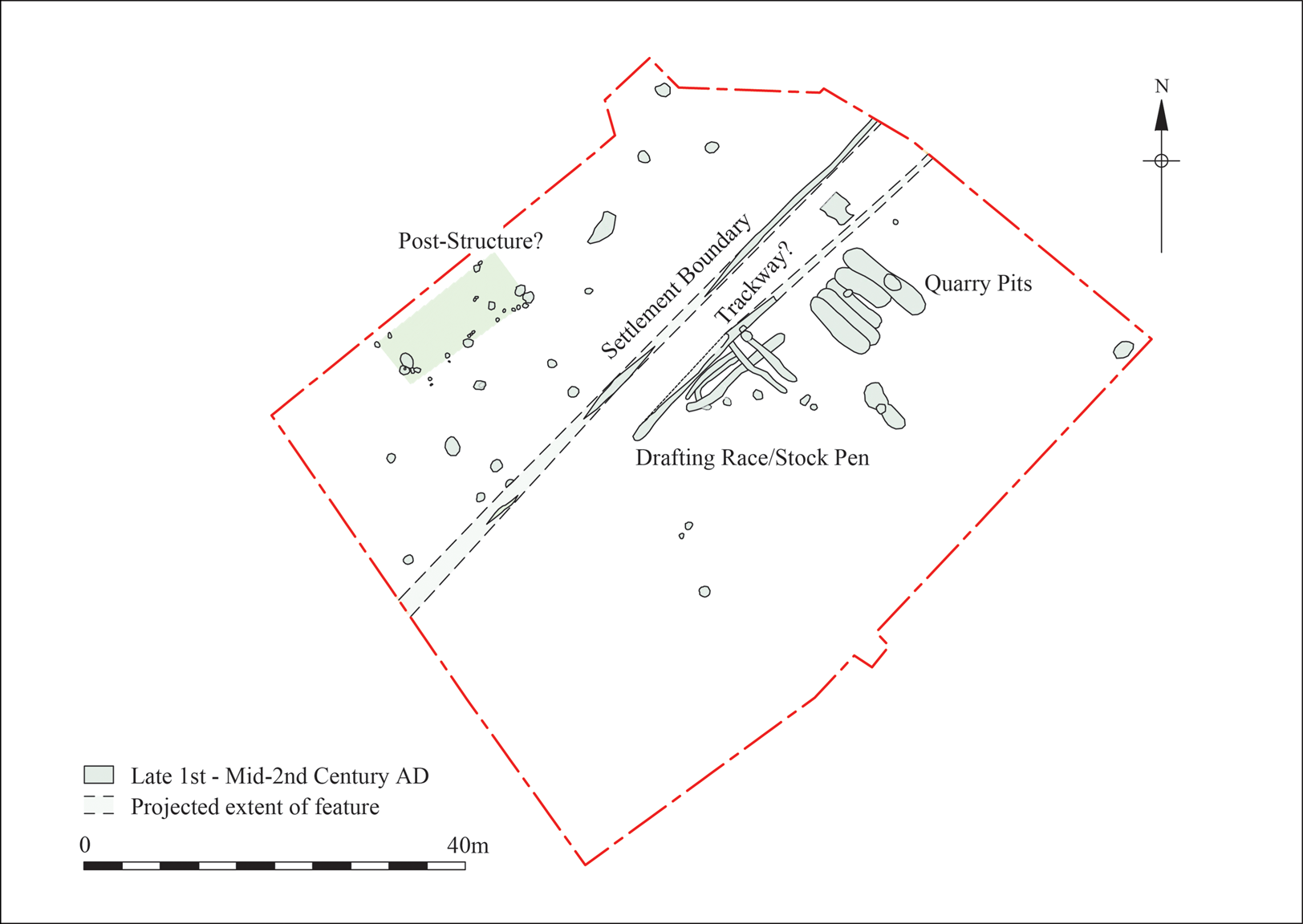

The site is located on a south-facing sandy slope (19–25 m above Ordnance Datum) extending down to a tributary stream of the river Deben (figs 2 and 3). The Deben itself is 250 m to the west; the site has commanding views south-east down the river valley. The middle and upper reaches of the Deben, as with the other river valleys in this area, form a narrow band of light and well-drained soils bisecting the High Suffolk clay plain. There is evidence of settlement on the site by the early Iron Age (c. 800–600 b.c.); occupation had shifted away a short distance by the later Iron Age, but scattered pits within the excavation area show continued domestic activity in the near vicinity. One such pit ([235]) contained the bronze handle, alongside an iron nail and residual struck flint and early Iron Age flint-and-sand-tempered pottery. The feature was not in itself securely dated but it was cut by another pit ([231]) that contained a small assemblage (21 sherds; 227 g) of probably later first-century a.d. pottery, including fine sandy micaceous black-slipped, oxidised and greyware fabrics, and part of a grog-tempered jar. Both pits were sealed beneath a later Roman (third- to fourth-century) soil, probably the remnants of a midden. By the mid-first century a.d., on-site activity had intensified and occupation continued until at least the end of the fourth century a.d. During this period the site was part of a fairly prosperous Roman farmstead, the core of which was probably to the north-west of the excavation area.

FIG. 2. Detailed site location showing topography, previous investigations and archaeological features by period (magnetometer survey conducted by West Yorkshire Archaeological Service; Harrison Reference Harrison2014).

FIG. 3a. Plans of the later Iron Age to early Roman period remains.

FIG. 3b. Plan of the early Roman period remains.

THE BRONZE JUG HANDLE

SF 63, fill (234) of pit [235]. Width of plate 35 mm; width of handle 15.3 mm; length 116 mm; depth 31 mm. Based on comparisons with published copper-alloy vessels, from both Britain and the Continent, the handle is most likely to be from a spouted jug; more particularly, it is probably the handle of a lidded water jug (Wasserkanne) or tin jug (Blechkanne),Footnote 4 a type that is rare in Britain.

The handle is a cast, hollow tube; overall it is circular in section (fig. 4). At the apex of the handle, the tube expands into an oval-shaped plate that would have been positioned to follow the curvature of the vessel neck below the rim. There are the remains of tin-rich solder on the inside of the plate; this would have been used to attach the handle onto the recipient vessel, in this case most likely a jug. This technique of handle attachment was mostly Roman, or at least no earlier than 50 b.c.;Footnote 5 earlier Iron Age vessels were primarily assembled using rivets.Footnote 6 Attaching the handle below the rim is in contrast to most known copper-alloy jugs recovered from Britain,Footnote 7 where the handle usually encircles the rim, often being soldered directly to it, as is the case with the example from Elms Farm, Heybridge, Essex.Footnote 8 At the point at which the handle expands into the attachment plate, there are two moulded ribs that are pierced at their apex. A bronze rivet sits across the ribs, through these two perforations. The rivet also holds the remains of a hinge loop for holding a lid in place between the moulded ribs. Although different in form, a handle from Moigrad in Dacia Porolissensis has a comparable hinge mechanism comprising a rivet between two ribs.Footnote 9 Similarly, fragments of a handle, associated with a jug, that were recovered during excavations at Zuegma in Turkey, display a bifurcated hinge mechanism with rivet and a tubular, ‘S’-shaped handle.Footnote 10 This form of hinge mechanism points to a date from 50–30 b.c. onwards, as it is a technique not known before this time.Footnote 11 The hinge mechanism would have supported a flat lid on the top of the jug, such as those from Dacia illustrated in Mustață Reference Mustață2017.Footnote 12 The handle widens along its length towards the base; the edge of the tubular handle at this point is rough, probably incomplete. It is possible that this section of the handle terminated in a now-missing base plate that would have attached the handle to the body of the jug. The base plate may have been decorative, perhaps anthropomorphic, as for other broadly contemporary jugs discovered in Britain; however, this is speculative. Without an attachment base plate, it is not possible to see how the handle would otherwise have attached to the jug. The lack of curvature on the handle suggests that it would be most suitable for attachment to a jug with a wide lower body, like the first-century b.c. example from Ca’ Morta.Footnote 13

FIG. 4. Bronze jug handle. (Drawing by Cate Davies; photographs by Strephon Duckering)

On the Continent, copper-alloy jugs or pitchers appear as pre-Conquest Italian imports, probably from Campania in Italy, at major oppida in northern Gaul and the Moselle region. For example, six bronze jugs have been found in the Aisne valley, of which four belong to the early Kappel-Kelheim type, of the late second to early first century b.c.Footnote 14 The remaining two handles are variants of the Kelheim form, as defined by Joachim Werner:Footnote 15 one of the preceding Ornavasso-Ruvo jug form and one of the later Ornavasso-Kjaerumgaard variety, which dates to the mid- to later first century b.c. The two jug forms found in the Moselle region, in graves at Titelberg and Goeblingen-Nospelt (Grave B), are both of this latter type. However, the forms of their handles do not correspond well with that from Easton. The Kelheim forms are defined by upright projections on the handles and variations in base plates: the Kappel-Kelheim has a Silenus-mask base plate, the Ornavasso variants have heart-shaped base plates and the Kjaerumgaard variety has the addition of tendrils.Footnote 16 Three Kelheim jugs, all Kjaerumgaard variants, have been discovered in Britain in graves at Aylesford Y,Footnote 17 Welwyn AFootnote 18 and Welwyn B.Footnote 19

Examples of copper-alloy jugs, or fragments thereof, are known from East Anglia, but these are predominantly of Imperial Roman date.Footnote 20 Essex has a large number of early Roman graves that contain copper-alloy vessels,Footnote 21 including two from Cremation 25 at Stansted that have ornamented handles and thumb rests (Eggers type 125), a form known from Pompeii and several graves of Flavian and Antonine date on the Continent.Footnote 22 More recently, Nina Crummy recorded in detail a copper-alloy jug discovered at Elms Farm, Heybridge.Footnote 23 This example has a handle that terminates in a foot, a form that Crummy notes has a wide distribution from ‘Thrace across to Britain but [examples] are found chiefly in the northern provinces of Pannonia, Germania, and Gallia Belgica, where they appear to follow the trade routes of the Danube and Rhine.’ Crummy compares it to two other examples of similar foot-handle jugs that are recorded in Britain: one from Hauxton, Cambridgeshire, and a second from further north, at Corbridge. She believes the Heybridge jug to have been manufactured in the first half of the second century a.d., far later than the suspected date of the Easton handle. Similarly, the trefoil jug and lion's-head handle found at Rivenhall, Essex, date to the first or second century a.d.Footnote 24

Examples of Roman Imperial period jugs are also known from Colchester,Footnote 25 HachestonFootnote 26 and, as examples of earlier jugs, from Santon, Norfolk,Footnote 27 and in the remarkable collection of grave goods from the Lexden tumulus near Colchester, where the overall date is c. 15–10 b.c.Footnote 28 Andrew Fitzpatrick notes a lack of ‘arms’ for enveloping the rim in his discussion of the Lexden handle, suggesting the likelihood of it being soldered to the vessel;Footnote 29 however, the poor condition of the artefact lends uncertainty to this interpretation. The handle from Easton bears no comparison with these or the Heybridge jug, again reinforcing a likely earlier date for its production and a Continental origin. However, there again seem to be no direct parallels for the Easton handle amongst the jugs recovered from Gallic or German late La Tène period contexts.

Amongst Suzanne Tassinari's classification of Roman bronze vessels produced in Italian workshops there is one form that dates between c. 30 and 1 b.c.: the ‘E.4000’ type.Footnote 30 Here, the upright on the handle has been pierced to allow a hinged lid to be attached. Examples are known from Aspiran, Soumaltre, France, and from Pompeii Antiquarium, Italy.Footnote 31 The Easton handle, seemingly unique in Britain, could be contemporary to Tassinari's E.4000 variant, possibly displaying some similarity in the way the base of the handle could be attached to the vessel and a reduced version of the hinge mechanism.

The jugs from Colchester and Thatcham, illustrated in Eggers Reference Eggers1966,Footnote 32 are Roman Imperial versions of this form and, while the Easton handle does not directly parallel either of these jugs, the hinge mechanism and mode of attachment point to it being an early precursor. It is a form that evolved on the Continent during the period of the Kelheim vessels, though sharing few similarities with those published to date.

X-RAY FLUORESCENCE ANALYSIS By Sarah Paynter

METHOD AND RESULTS

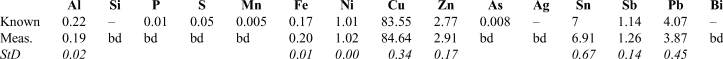

Quantitative analysis was undertaken using a Bruker M4 Tornado X-ray fluorescence spectrometer, which is able to focus on a spot size of 30 μm. This is a non-destructive analytical technique, but the weathered surface has a different composition to the metal beneath, so a small area of bare metal was exposed with a scalpel. A voltage of 50 KV and a current of 200 μA were used, under vacuum. A standard of known composition (BM10) was also analysed to ensure the precision and accuracy of the results; the known and measured compositions are compared in table 1 and agree well.

TABLE 1 MEASURED VALUES (AVERAGE OF 3) COMPARED TO CERTIFIED, KNOWN VALUES (bd = below detection limit; StD = standard deviation)

The residue inside the handle and the small fragment of the lid hinge were analysed only qualitatively because these areas are fragile. No attempt was made to remove the corrosion, so the results are only an indication of the composition.

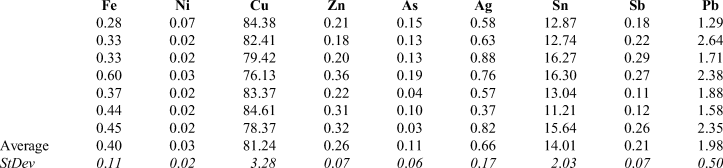

The results for the handle are given in table 2. Multiple analyses were completed on two prepared areas and an average is given with the standard deviation. Bismuth was sought but not detected. The remaining analyses were of corroded surfaces, so are discussed below but not included in the table. The results are normalised as the totals were not always 100 per cent, since the handle surface is not flat.

TABLE 2 XRF ANALYSES OF PREPARED METAL ON THE HANDLE SURFACE, NORMALISED

DISCUSSION

Large numbers of Roman copper-alloy artefacts have been analysed from across the Roman world. These studies tend to be dominated by certain types of artefacts, such as statuettes, needles and brooches, and clearly show that certain alloys were preferred for specific types of object; however, many of the objects are not closely dated. Alloys have different properties, including colour, melting temperature and workability, and this influenced the type of alloy chosen for each application.

The handle is made of bronze: a copper/tin alloy. The composition of Roman bronze varies, but the majority contains 0–19 per cent tin and 0–33 per cent leadFootnote 33 (not including mirrors, which have even higher tin contents), with traces of elements such as antimony, silver, nickel, arsenic and zinc. Certain alloy compositions were preferred for particular applications: for example, objects with very high lead contents tend to be large, complex castings. Jugs belong to a group, including paterae/saucepan-style vessels and ladles, that is consistently made of a bronze with about 10–11 per cent by weight (wt%) tin, less than 3 per cent by weight lead and zinc, and the rest copper.Footnote 34 Similar compositions have been identified amongst the contemporary vessels at Stanway, Colchester.Footnote 35 Pliny describes the proportions of fresh and recycled metal used to make bronze alloys for different applications.Footnote 36 The bronze preferred for vessels was versatile because its properties make it suitable for both casting and working.

The Easton handle, which contains around 2 per cent by weight lead and 14 per cent by weight tin, is therefore fairly typical of this type of Roman vessel. The lead content of bronze handles, rims and feet from vessels is sometimes found to be higher than that of the bodies,Footnote 37 and lead contents as high as 10 per cent by weight were detected in one area of the Easton handle, but this is likely to be because the lead forms tiny discrete droplets in the bronze, so the lead content is not homogeneous throughout the casting.

The remains of the lid hinge on the Easton handle are also bronze. Slightly higher levels of lead were detected, but this area was badly corroded so the analyses here must be interpreted with greater caution. Twice the amount of tin was detected on the inside face of the handle plate; this is likely to be the remains of a solder used to attach the handle to the body.

The Easton handle does have some unusual characteristics in terms of its trace elements. Arsenic contents over 0.1 per cent by weight occur in many copper alloys from Iron Age Britain (62 per cent) but are less common in Roman ones (only 15 per cent);Footnote 38 so the levels of arsenic detected here are on the high side.

The levels of silver detected (0.7 per cent by weight) are also high and appear to be concentrated in the lead droplets in the alloy, because the two elements are correlated. Silver contents are usually between 0 and 0.12 per cent by weight in Roman copper alloys.Footnote 39 Similarly, the silver content of Iron Age and Roman lead metal rarely exceeds 500 ppm and is often much lower because of the efficient technology for extracting silver from lead, and other alloys, at the time.Footnote 40 A thin layer of silver can be applied to the surface of bronze alloys (although none is visible here) or silver can become enriched at the surface, either through corrosion processes or deliberate etching or heat treatments by the craftsperson.Footnote 41 Alternatively, Arne Jouttijärvi reports abnormally high silver contents for a Roman comb and two brooches, and speculates that this may result from the recycling of silvered copper-alloy objects.Footnote 42 Therefore, there are several possible explanations for the analytical results, and it may be possible to interpret these further as more analyses of similar objects become available for comparison.

DISCUSSION

In the late Iron Age, the Deben valley was in the border area between the tribal territories of the Iceni to the north and the Trinovantes/Catuvellauni of south Suffolk and Essex to the south.Footnote 43 The Iceni have sometimes been seen as culturally insular and unreceptive to the Roman-influenced material culture and behaviours that gradually became adopted across much of south-eastern Britain in the century or so before the Roman Conquest. ‘Belgic’/Romanising wheel-turned pottery is rare in Norfolk and north Suffolk, and urned (‘Aylesford-Swarling’) cremation burial did not gain much popularity as a funerary rite. At the élite level, there is relatively little evidence in Iceni territory for adoption of Gallo-Roman dining or drinking habits, such as the import and consumption of wine.Footnote 44 Nonetheless, there is some, such as the silver cups from Hockwold-cum-WiltonFootnote 45 and the mid-first-century a.d. hoards from CrownthorpeFootnote 46 and SantonFootnote 47, which all contain Italian and more local bronze vessels.

Against this backdrop, the imported Continental jug handle is notable, suggesting the presence in late Iron Age Easton of an élite who had access to imported goods from the Roman world and who were, perhaps, also receptive to the broader culture of which those objects were part. Probable pre-Conquest Gallo-Belgic imports were found during excavation of the nearby Roman ‘small town’ at Hacheston, 3 km downstream along the river Deben, and there are some indications that this may have been an ‘extensive’ settlement of the sort that developed in the pre-Roman period in Trinovantian territory.Footnote 48 Nine kilometres south-west of Easton stood the substantial fortified settlement at Burgh, whose inhabitants also used imported pottery vessels and drank wine from the Continent.Footnote 49 There is considerable overlap of Iceni and Trinovantian/Catuvellaunian material culture in south-east Suffolk, suggesting the presence of a social grouping with strong links to both ‘tribal’ areas.Footnote 50 Coinage distributions might imply that this area, perhaps extending as far north as the river Alde, came under direct Catuvellaunian control by the early first century a.d.;Footnote 51 such a possibility is also suggested by the evidence from Burgh, where ‘Belgic’ pottery appears only late in the archaeological sequence.Footnote 52

Many of the imported copper-alloy jugs found in Britain have been recovered from burial contexts; they may have been held for generations prior to deposition. Such imports are likely to have served to represent the wealth and status of the deceased owner, or they may have symbolised the contacts and alliances of the dead.Footnote 53 Quentin Sueur has demonstrated that in Gaul the geographical distribution of the earlier forms of jugs, such as the Kappel-Kelheim forms, highlights strong commercial links or political alliances between Rome and Gallic tribes such as the Remi and Treveri.Footnote 54 Allowing for the probability that a robust and finely made metal vessel may have remained in use or circulation for a considerable period of time after its manufacture, there is a possibility that the handle at Easton could have been deposited at any time up to the late first century a.d. This potentially opens the way to more fanciful explanations of its provenance, as, for example, loot from Colchester or another Roman settlement sacked during the Boudican Rebellion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Pre-Construct Archaeology Ltd (PCA) would like to thank Myk Flitcroft of RPS (formerly CgMs) Consulting for commissioning the work and Hopkins and Moore Developments Ltd for funding the project. PCA is also grateful to Rachael Abraham of Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service Conservation Team for monitoring the work. The fieldwork was managed for PCA by Taleyna Fletcher and supervised by Mary-Anne Slater, assisted by Tom Woolhouse, who also managed post-excavation analysis. Katie Anderson analysed the Roman pottery. Figures accompanying this report were prepared by Rosie Scales of PCA's Drawing Office; the illustrations are by Cate Davies and the photographs by Strephon Duckering. Ruth Beveridge extends her thanks to Quentin Sueur, Ernst Künzl, Jörn Schuster and Michel Feugère for their advice. The XRF analysis was carried out by CASSI (Commercial Archaeological Science for Social Investigation) Ltd and reviewed by Florian Ströbele. The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their advice and input.