1. Introduction

The vast destruction that climate change is poised to cause over the coming decades is not limited to homes and businesses in coastal and low-lying areas. A truly systemic risk, climate change risk permeates nearly all aspects of society – including cyber security. Increased natural disaster activity from climate change could have a subtle connection to the cyber domain that has gone largely unnoticed, specifically with regard to economic security. The connection could become evident through impacts on the insurance industry. Losses to the insurance industry due to natural disaster-induced climate change could limit the capital available to the cyber insurance market, depriving businesses and nation states of a key lever for economic security. This article makes an original contribution by exploring how increased natural disaster activity from climate change could constrain access to insurance and reinsurance capital for cyber risks, depriving the cyber domain of an important economic security lever.

Climate change is perhaps the broadest and most menacing systemic risk faced by humanity. It appears prominently in national security strategies from the United States to the Russian Federation (Biden, Reference Biden2022 and Buchanan, Reference Buchanan2021) and falls squarely into the environmental security sector (Albert and Buzan, Reference Albert and Buzan2011). The views of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have been called a “code red for humanity” (Chestney and Januta, Reference Chestney and Januta2021). Over time, it could lead to an increase in the frequency and severity of natural disaster events, ultimately threatening property, economic activity and even human life. The climate change threat is almost universally believed to be imminent, severe, and potentially existential to humanity. Simultaneously, cyber risk has become an area of considerable concern. Largely understood to be the “threat opportunities from digital and computational technologies,” cyber risk manifests in many forms, covering military, economic, and societal security sectors (Valeriano and Maness, Reference Valeriano, Maness, Brown and Eckersley2018). This article thus focuses specifically on the nexus of cyber security and economic security, given the frequency with which cyber threats have manifested as economic security problems, as well as the magnitude with which it has done so.

An emerging area of research, and one that has not received significant attention, is the extent to which climate change could impact cyber security. Although some research has looked at the direct effects of natural disasters on technology infrastructure or the information environment, this article makes a unique contribution to climate change and cyber security scholarship by exploring the interplay between climate change and cyber security via the role of insurance in each. This paper therefore looks at the following research question: Does the impact of natural disaster activity pose a threat to cyber security through its effects on the insurance industry, either through the depletion of capital or indirect factors that could impede capital flows to cyber-focused risk transfer instruments?

The paper begins by reviewing the relationship between climate change and natural disasters, as well as the effects of natural disasters on insurance and reinsurance (together, “re/insurance”) capital. It also reviews the structure and nature of the cyber re/insurance market, to include sources and availability of capital. The impact of natural disasters on the re/insurance industry is then contemplated with a view toward the use of capital, either to pay claims from such events or to allocate to specific categories based on the potential for financial return. This becomes the focal point for linking climate change to cyber security via a qualitative research project involving interviews with relevant reinsurance industry stakeholders. The findings reveal some preliminary connections between climate change risk and economic security concerns for the cyber domain, although they are not immediately imminent and profoundly catastrophic. However, the fact that natural disasters could limit access to capital for cyber risks in the future suggests that near-term efforts to secure capital sources for cyber re/insurance could improve cyber security in the future.

2. Literature Review

The relationship between climate change and cyber security has not been thoroughly explored, although some work in the literature links natural disasters to cyber security through intermediate steps. However, the connections are quite specific. Historical scholarship zeroes in on the potential for cyber-attacks that take advantage of post-disaster chaos and societal vulnerability, and the potential cyber security consequences of a natural disaster impacting the physical infrastructure that supports the cyber domain, such as an earthquake damaging many important data centres. These direct causal views ultimately underscore the absence of consideration of the economic security problem, involving the fact that both cyber and property insurance rely on underlying capital; as well as the risk that the larger property market could consume that capital through loss events. The latter could occur to a degree that cyber insurance would experience the risk of a capital shortfall.

The literature selected for discussion in this paper comes from a much broader set. It was chosen for its direct relevance to the research question on the impact of natural disaster activity as a threat to cyber security through its effects on the insurance industry. The focus is on the freshest perspectives and scholarship possible, given that cyber risk and insurance is relatively new, and because the literature has developed rather quickly. To this end, the author has sought to rely on literature published since 2020. Not only does this period sit well within the insurance industry’s post-NotPetya view of cyber risk, which occurred in 2017, but it also includes the ransomware epidemic that preceded Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. An exception is made for historical work on cyber security from the security studies scholarship, which predates the NotPetya attack and subsequent cyber insurance sector evolution.

The literature shows that there is little previous work that relates directly to this article’s research question, which validates this paper as addressing a gap in the historical scholarship. To provide the necessary context for the research to follow, the literature chosen first establishes that the link between climate change and cyber security has been under-explored, establishes and discusses cyber risk as an economic security concern, and explores the limits of the effectiveness of cyber insurance for economic security.

2.1. Direct Link between Climate Change and Cyber Security Has Been Under-Explored

Absent in the literature is the notion that the impact of climate change on cyber security moves through a different set of intermediary steps, with economic security the focal point. Natural disasters consume insurance capital (through the payment of claims). That consumption of capital, along with other market factors, could make cyber insurance more difficult to secure, resulting in economic security vulnerability. The historical literature offers views on the different links in this chain of reasoning but has not connected them. Given the indirect nature of the impact of climate change on cyber security, it is crucial to understand how insurance supports economic security in the face of cyber and natural disaster risks, respectively, before using it as the focal point for the relationship between climate change and cyber security.

The most common direct connection between climate risk and cyber security is the connection between natural disasters in areas with technology or telecommunications industry concentrations. For example, there is the risk of a San Francisco area earthquake and the effect it would have on Silicon Valley-based technology companies (Cherney, Reference Cherney2016), threatening the systems on which businesses rely. In fact, the earthquake scenario is sufficiently realistic to have led to an innovative risk transfer transaction, namely the catastrophe bond sponsored by Google parent Alphabet (Evans, Reference Evans2020), providing it with more than $300 million in insurance protection for earthquake risk. While the extent to which earthquake risk is related to climate risk is subject to debate (Sadhukan et al. Reference Sadhukan, Chakroborty and Mukherjee2022), the link between natural events and cyber security risks can be extrapolated to cover natural events more closely linked to climate change, such as tropical storms. When cyber security is viewed through an economic lens, on the other hand, the potential links to climate change and natural disaster become more apparent. Section 2.2 contemplates cyber security as an economic security problem, ultimately connecting to vulnerability via reliance on insurance.

The direct threat from natural disaster events is only one potential connection to cyber security risk. More heavily covered – and presumably more imminent – is the concern that the post-disaster environment is inherently chaotic and thus open to human-initiated cyber security threats, as well as other forms of outside influence and information operations (Gaskell, Reference Gaskell2022; Johansmeyer, Reference Johansmeyer2023). Although historically somewhat rare, the vulnerable populations and general disorder that come with a natural disaster may make such timing more attractive for cyber-attacks (e.g. Centre for Cyber Security, 2021). However, both precedent and impact remain thin and evolving.

2.2. Cyber Risk as an Economic Security Concern

Security in the cyber domain spans most of the five security sectors (Albert and Buzan, Reference Albert and Buzan2011), as discussed above. Political and military security in the cyber domain are intuitive, and the topic of frequent and regular discourse, and societal security, has gained increasing attention. This is particularly true in the context of disinformation and “information confrontation” as components of cyber security, the definition of which has been “highly contested,” but can be said to “incorporate a wide range of cyberthreats and cyber risks, including cyberwarfare, cyberconflict, cyberterrorism, cybercrime, and cyberespionage” (Duclos, Reference Duclos2021; Maurer and Ebert, Reference Maurer and Ebert2017). Environmental and economic security, the remaining two of the five security sectors, together comprise a powerful and present risk. This article links economic and environmental security via the cyber domain.

The focus on economic security in the cyber domain is bolstered by the notion that the interplay between cyber and traditional military and political security concerns may have been exaggerated. In the military domain, scholars have firmly landed on the notion that cyberwarfare is not a major threat. Rid, for example, explains, “No cyber-attack has ever damaged a building” (Rid, Reference Rid2012), and Gartzke adds, “There will not be a cyber Pearl Harbor, except possibly when and if a foreign power has decided it can stand toe-to-toe with conventional US military power” (Gartzke, Reference Gartzke2013). Although some attacks have been called forms of warfare, like the 2017 NotPetya cyber-attack, they have tended to fall short in impact, particularly when compared to kinetic activity (Johansmeyer, Reference Johansmeyer2022).

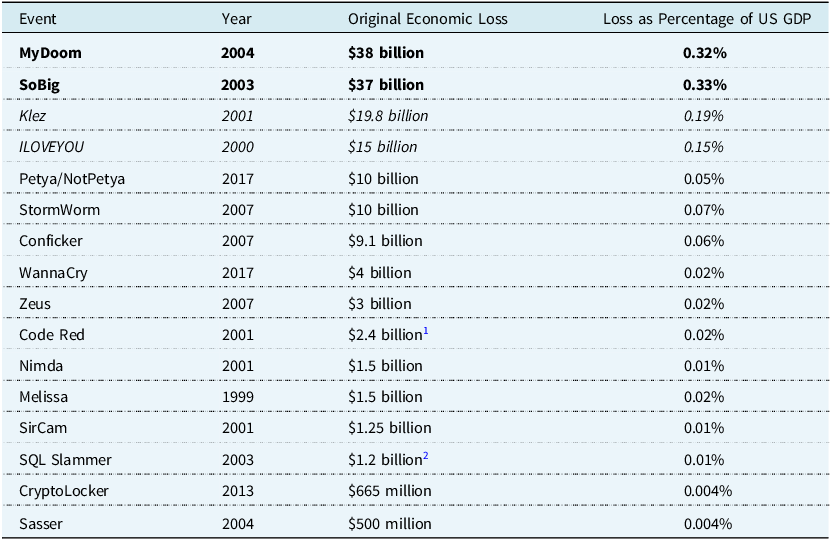

To evaluate cyber as a non-war and rather an economic security problem, a sense of magnitude is necessary. While securitisation requires more than just a substantial economic impact, there must be a practical threshold for use in analysis. One such threshold is offered by Reference Eling, Elvedi and FalcoEling, Elvedi, and Falco, in their study on the economic impact of extreme cyber risks, although the threshold falls short of a true analytical test (Eling et al., Reference Eling, Elvedi and Falco2022). They propose that an extreme cyber-event should have economic effects in the range of 0.2–2% of the affected state’s GDP. Only two events have reached this threshold, as shown in Table 1, with only two more coming close to the low end of the range. Not only are such events rare, but they have not occurred recently, with the two meeting the low end of the threshold set by Eling et al. twenty years ago, and the other two shortly before them.

Table 1. Historical Cyber Event Losses Relative to US GDP

Sources: Beattie (Reference Beattie2012), Cyware Hacker News (2016), Gerencer (Reference Gerencer2020), Greenberg (Reference Greenberg2018), Leman (Reference Leman2019), and OMB (2023).

The low-level securitisation of cyber risks – using the test created by Eling et al. – suggests that the risk can be managed, particularly via economic security means. As a mechanism for financing post-event recovery, it is uniquely equipped to address the specific nature of the economic security threat. This is precisely what insurance does. The challenge involved in using insurance as the primary lever for economic security in the cyber domain is the lack of insurance penetration; and related to that, the lack of capital to support increased insurance penetration. It is not yet sufficiently pervasive.

Insurers are reluctant to allocate more capital to the risk without reinsurance support, as evidenced by the fact that insurers cede approximately 50% of what they write to reinsurers (Cellerini et al., Reference Cellerini, Finucane, Lanci and Holzheu2022). Reinsurers, in turn, do not have access to the same risk transfer resources and generally have to retain the risk they write. Their access to risk transfer markets is limited (Johansmeyer, Reference Johansmeyer2023). These constraints on reinsurer risk and capital management make it more difficult to allocate additional capital responsibly, resulting in an inability to support rapid growth and reinforcing the current state of under-penetration. Further, the market dynamics of larger classes of insurance business could inadvertently affect the availability of capital available to insure cyber risks. The question, therefore, is whether an increase in natural disasters, driven by climate change, could consume sufficient capital or exhibit other characteristics that would threaten the stability of the cyber insurance sector.

2.3. Limits on the Effectiveness of Insurance for Cyber Security

The perceived lack of penetration has become a salient concern for the use of insurance as a mechanism for cyber security. Most literature suggests that cyber insurance remains largely under-penetrated worldwide and that growth has stalled (Johansmeyer, Reference Johansmeyer2023). The under-penetration of cyber insurance is linked to constrained supply, at least in part. Insurers are reluctant to allocate more capital to the risk without reinsurance support, as evidenced by the fact that insurers cede approximately 50% of the business they write to reinsurers (Cellerini et al., Reference Cellerini, Finucane, Lanci and Holzheu2022). Reinsurers, in turn, lament the lack of their own risk transfer alternatives, resulting in the fact that they largely have to retain any business they write. These constraints on reinsurer risk and capital management make it more difficult to allocate additional capital responsibly, resulting in an inability to support rapid growth and reinforcing the current state of under-penetration.

While the cyber insurance sector may not be sufficiently capitalised relative to potential future market penetration, the insurance industry overall enjoys sufficient capital (FIO, 2022). There is sufficient supply of capital to address the general needs of the insurance industry, and that includes absorbing the effects of catastrophe events, which can have disproportionate effects on industry capital (FIO, 2022). The imbalance in economic resources (via insurance) between natural disasters (property insurance) and cyber-attacks (cyber insurance) is evident. There is simply a larger pool of resources to support people affected by natural disasters, not to mention well-worn societal, economic, and governmental pathways to facilitate both physical and economic recovery.

The question that remains is whether these two categories of insurance are independent, or whether the resources available from cyber insurance are subject to threat from natural disasters. Specifically, if natural disaster activity was sufficient to deplete re/insurance capital meaningfully, would that result in an inability or unwillingness to continue to deploy capital to the cyber class of business, let alone commit to continued rapid growth? In this way, the cyber insurance environment could be perceived as vulnerable to natural catastrophe activity, and thus in the event of major natural disasters, economic security via the cyber domain could be imperilled. With the threat of climate change continuing to gain momentum, the prospect of greater re/insurance capital consumption due to natural disasters could become an even larger economic security problem via the cyber domain.

2.4. Nexus of Cyber and Climate Risk – Property-Catastrophe Reinsurance

Almost no analysis of the connections between climate change and the cyber domain via the economic security sector has been conducted, particularly regarding how natural events could redirect capital from the cyber re/insurance market. Given the reliance of cyber insurers on reinsurance (colloquially known as insurance for insurance companies), and the fact that the reinsurance market is primarily focused on natural catastrophe risk, how the reinsurance market responds to climate change-driven natural disaster activity has profound implications for cyber security. The cyber insurance market relies heavily on reinsurance, with insurers ceding approximately 50% of their business to reinsurers (Cellerini et al., Reference Cellerini, Finucane, Lanci and Holzheu2022). Further, the cyber re/insurance market is quite small, particularly in comparison to the property insurance and property-catastrophe reinsurance sectors. Property insurance premium is estimated to be $450 billion as of 2021 according to Swiss Re, with the potential to grow to $1.3 billion by 2040, compared to a mere $13 billion in worldwide premium for cyber insurance (Howard, Reference Howard2021; Johansmeyer, Reference Johansmeyer2023). The question this raises is whether the availability of cyber insurance could be constrained by loss activity due to natural disasters, particularly through the effects of such events on the property-catastrophe reinsurance market, which has an estimated $540 billion in capital (Dorfman, Reference Dorfman2022).

The effect that climate change could have on security in the cyber domain can hence be traced quite clearly to the field of insurance, which is fundamental to economic security in developed markets across both physical and cyber domains. In fact, the focal point within the insurance market is specifically on property-catastrophe reinsurance and how the use of capital in that sector can affect the availability of cyber insurance. To fill the gap in historical research and make a unique contribution to the scholarship, this article explores the specific threats to cyber insurance capital availability that could arise through an increase in natural disaster activity. It does this by interviewing reinsurance and other risk transfer professionals on this specific issue, which appears to be the first time such an effort has been made. While the connection is neither intuitive nor direct, concerns about the prospect of cyber insurance potentially experiencing shortfalls due to increased natural disaster activity in the future are beginning to arise. The specific dynamic has not occurred yet, but the convergence of several factors has begun to make it possible to imagine such a scenario.

3. Methodology

This paper sets out to explore the relationship between climate change and cyber security via the economic security implications of increased natural disaster activity and its impact on re/insurance capital. To this end, a mixed methods approach is necessary. The research begins with a review of publicly available information on natural disasters and their impact on reinsurance capital, which builds on the relationship between natural disaster activity and climate change. Secondary research involves a review of summary statistics related to cyber re/insurance penetration, loss experience, and capitalisation. The review of publicly available information serves to build a foundation for the original primary research conducted for this article, which consists of a qualitative research effort in which cyber reinsurers and insurance linked securities (ILS) fund managers discuss the relationship between risk transfer capital and recent natural disaster activity.

3.1. Summary statistics using publicly available information

There are several generally accepted sources of information about the insured and economic consequences of natural catastrophes. Munich Re NatCatSERVICE (2025) and Swiss Re’s sigma-explorer (2025) are among the most widely accepted and are available for public use and analysis. In order to provide context for the primary research that follows, the analysis of the research question requires an understanding of the insurance industry implications of natural catastrophes. To this end, a historical view of industry-wide insured losses is built primarily with data from sigma-explorer, given it has greater granularity of publicly available data; while data from Munich Re NatCatSERVICE tends to be available only in summary form in reports and public announcements (e.g. press releases). However, since sigma-explorer does not offer an estimate after 2022, data from Munich Re NatCatSERVICE is used for 2023.

The data collected from sigma-explorer and Munich Re NatCatSERVICE provides a view of aggregate industry-wide insured catastrophe losses by year, which is then used to provide a ready and relatable benchmark for industry impact against which to discuss how natural catastrophes could impair reinsurance capital sufficiently to impact capital availability for cyber insurance. It is important to remember that industry-wide insured loss estimates represent a snapshot of how the loss is perceived at the time that estimate is published. Over time, industry-wide insured loss estimates for natural catastrophes can increase or decrease as more information becomes available. For this reason, one can assume that the estimates for older events tend to be more stable, given they are informed by more underlying loss-related data and experience. Nonetheless, the process of estimating industry-wide insured losses is inherently subjective and must be treated as guidance rather than fact.

3.2. Original research with reinsurance and ILS market participants

Primary research regarding the relationships between cyber risk, climate change, and the re/insurance industry comes from interviews with eleven cyber reinsurance executives and ten ILS managers. The discussions about the intersection of cyber security and natural disasters are extracted from interviews involving a much broader range of cyber re/insurance and security concerns, with the comments relevant to this article’s research question specifically extracted for analysis. Many themes emerged apart from those discussed in this article and are in various stages of review for future publication. Appendix A provides a list of publicly available articles resulting directly from the interviews but covering other themes from those addressed here.

The use of qualitative research methods is a necessity given the small sample size (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). In total, there were 21 interview subjects, 10 of them ILS managers and 11 of them cyber reinsurance executives. The interviews were conducted and recorded using Microsoft Teams and ranged from 30 minutes to 60 minutes, with each participant interviewed once between 24 March 2023 and 14 June 2023. The project uses a thematic analysis approach, with semi-structured interviews and transcripts each coded multiple times.

One could argue that the small sample size is a limitation of the study, and that would be a fair criticism. However, the participants represent significant shares of both the ILS and cyber reinsurance sectors. The 10 ILS managers interviewed represent $41.3 billion in assets under management (AuM), which is approximately 39% of the $104.9 billion ILS sector (Artemis.bm Deal Directory, 2023). Among them, 8 engaged explicitly with the subject of natural catastrophe sector impact on cyber re/insurance capital availability and pricing (36.5% of worldwide ILS AuM), with 2 of them indicating that the dynamic between cyber insurance and natural disasters is not an issue). The 11 cyber reinsurance executives represent $3.7 billion in affirmative cyber reinsurance premium, which is approximately 55% of the worldwide $5.5 billion market. This market estimate is based on interview responses that put global cyber insurance market premium at $12 billion, with an estimated 50% ceded to reinsurers (Cellerini et al., Reference Cellerini, Finucane, Lanci and Holzheu2022).

Of the 21 subjects interviewed (11 cyber reinsurance executives and 10 ILS managers), 9 reinsurers and 8 ILS managers discussed the potential role of natural disaster activity in impacting the availability and price of cyber risk transfer capital. Among them, 9 cyber reinsurance respondents and 6 ILS manager respondents – representing 63% of respondents by premium and 58% of respondents by AuM, respectively – raised the prospect of natural catastrophe losses directly affecting capital availability for cyber insurance.

Not all participants were prompted to discuss the issue, and those that did not mention it and were not prompted were simply missed, because the semi-structured interviews took a different direction and there was ample other material to focus on. What has emerged may be a lack of consensus on the notion that natural catastrophes (and thus climate change) could threaten the availability of capital for cyber insurance; but at the same time there is a directional indicator that this is a risk worth monitoring, given the sizeable majorities from each participating constituency suggesting at least a tangential connection. Further, the differences in perception by category – reinsurance versus ILS – suggest a power imbalance with regard to capital flows in this context. The views of the respondents, however, require context – Section 3.3 provides it in the form of an analysis of historical natural catastrophe loss activity and the effect it has had on re/insurance industry capital.

This represents another opportunity for further research. In addition to broadening the sample size, or simply revisiting the market with the same sample size given that the individuals interviewed may change positions from time to time (indeed, some have since having been interviewed), future researchers should contemplate more focused studies. This focus should specifically be on the topic of how natural catastrophe loss activity could impact capital availability for the cyber insurance sector, particularly to build on the findings of this paper.

3.3. Research limitations

The research involves qualitative methods, which invites the risk of bias. Efforts have been made to mitigate bias risk by engaging participants beyond simply the basis of market share, in order to attract a broader set of perspectives. However, the cyber re/insurance market is small and highly concentrated, which means that the risk of bias cannot fully be neutralised. To further address concerns about bias, the methodology and findings are offered in a way that maximises transparency without imperilling the anonymity of the participants.

The risk of bias in qualitative research has to be accepted, and it is worth tolerating, particularly given the nascent state of the cyber insurance sector. There is little in the way of raw data available for this market, particularly with regard to the perspectives of cyber re/insurance leaders and the decisions they make. The only way to gather this information is to speak directly with the actors involved in the business, and that introduces a risk of bias that may be higher than that present in quantitative research. The fact that the cyber insurance sector is so new deprives researchers and scholars of the rich context associated with other, longer-standing risks and classes of insurance business. This article seeks to provide a foundational study on a qualitative basis that can be used to trigger future research that can help build out a platform for more robust study.

4. A Capital Connection between Cyber Security and Natural Disasters

The prospect of capital availability for cyber insurance becoming constrained due to an increase in natural disaster activity may seem remote, given the historical data, but it has already become a concern across the re/insurance industry. In fact, the research question itself comes from casual industry conversations that occurred in the fourth quarter of 2022, when the impact of Hurricane Ian on the global insurance industry was still to be determined. The prospect of a major loss arose as a concern for the cyber insurance industry, which has struggled to secure sufficient capital for growth. The impact of natural disaster activity on the cyber re/insurance and ILS market so far, though, has been subtle and nuanced. While it is clear that there are connections of at least influence (if not causation) between natural disaster activity and the ability of reinsurers and ILS managers to allocate capital to cyber risks, the market is split. When asked about this risk, an executive at one of the largest ILS managers in the market replied, “Yeah, 100%,” but another replied, “I would say no.”

Following the review of natural disaster activity, the analysis of interview transcripts focuses on two emergent themes: The direct consumption of capital by natural disasters and the role of natural disaster activity on reinsurance rates, leading to an opportunity cost that could impede the flow of capital to cyber risks. Again, the participants do not provide a consensus view. There is a broad concern about the effect of natural disasters on the availability of capital for cyber risks. Although they see, at most, a remote risk of this arising through the direct consumption of capital by natural disasters, they do see the opportunity cost in a hardening rate environment for property – catastrophe risks as a barrier to the future flow of capital to cyber risks – and in fact this is even a present concern.

4.1. Confluence of Climate Risk and Economic Security

A “disaster” is “a serious disruption of a community or society at any scale due to hazardous events interacting with conditions of exposure, vulnerability and capacity, leading to one or more of the following: human, material, economic and environmental losses and impacts” (UNDRR, 2025). The insurance industry focuses more on natural catastrophes, which require further qualification, specifically in terms of impact on the insurance industry. A natural catastrophe refers to a natural disaster that causes sufficiently large amounts of insured loss. This is a standard that can vary from one company to the next and varies among industry-wide bodies. The economic security implications of climate change in general can be viewed through the insurance industry lens, with the lack of capital for post-event remediation (via claims payments) suggestive of vulnerability. This concern could then be stretched to cover the cyber domain, in the event that changes in the use or deployment of insurance capital lead to shortfalls in insurance protection for cyber risks.

According to data from sigma-explorer, industry-wide insured losses from natural catastrophe events reached $105 billion in 2021, up from $89.5 billion in 2020, $56.7 billion in 2019, and $89.7 billion in 2018 (Swiss Re Institute, 2025). The sigma-explorer database does not have an estimate for 2022, but Munich Re NatCatSERVICE has one at $120 billionFootnote 3 (Munich Re, 2023a). The ten-year average industry-wide insured loss for the period ending 2022, using sigma-explorer with Munich Re NatCatSERVICE to fill 2022, is $77.5 billion. The average for the 25-year period ending in 2022 is only $62.1 billion (not indexed for inflation). According to data from sigma-explorer, natural catastrophe activity has risen steadily since 1970, growing from 43 events that year to 170 events in 2021 (Swiss Re Institute, 2025). More than half of the years since 1970 were the worst on record at that time.

Over the past five years alone, worldwide natural disasters have cost the global insurance industry more than $450 billion, much of it borne by reinsurers. Moreover, the upward trend has left many capital providers cautious. The situation is far from dire, though. Reinsurance broker Guy Carpenter estimates global traditional reinsurance capital to be $435 billion (Evans, Reference Evans2022), with ILS adding another $104.9 billion (Artemis.bm Deal Directory). Capital is certainly sufficient, but the loss trajectory is worth noting. Although natural catastrophe activity appears to be unlikely to cause sufficient erosion of capital to imperil the insurance industry as a whole, the prospect of capital consumption on a smaller scale calls for consideration, particularly since the reinsurance and ILS market deals in remote risks. The views of both cyber reinsurance executives and ILS managers on this subject, below, are generally consistent with the historical analysis above, with some treating it as an indicator of a potential future problem to be contemplated today.

4.2. Capital Erosion from Natural Disaster Losses

Both reinsurers and ILS fund managers saw the threat posed by natural catastrophe loss activity to the availability of capital for cyber as noteworthy but rather thin. Although there was no genuine fear or concern conveyed by interview participants with regard to this prospect, some were still aware of the possibility that natural catastrophes could have some impact on capital availability for cyber (and other classes of business), given that all insurance claims ultimately draw from the same pool of industry-wide capital. While there has been no shortage of major natural catastrophes worldwide since 2017, with considerable financial impact on the global re/insurance industry, the losses themselves have not been sufficient to divert capital flows away from cyber. What is most evident from the discussions with ILS fund managers and cyber reinsurers on this subject is the difference in perspective they have.

Cyber reinsurers have broadly indicated a need for additional capital to fuel growth (Johansmeyer, Reference Johansmeyer2023b), which provides important context for the depth of their concerns about capital availability, particularly within the context of retrocession. ILS managers do not believe that capital erosion from natural disasters had a significant direct effect on capacity for cyber risk transfer. Six respondents either state or imply some connection, but their views on the depth of that impact vary. Two respondents, both with experience in the cyber-ILS market, see a more modest connection between natural disaster activity and the availability of capital for cyber re/insurance. Of the four remaining cyber-ILS markets that see an impact, only one sees capital erosion as a potential concern. However, it offers a fairly specific and nuanced explanation, starting with the fact that natural catastrophe risk is the “engine” for their business, which in turn is used to “fund the alternative ideas,” such as cyber. The other three believe that natural catastrophe losses can affect cyber capital availability indirectly.

Similarly, cyber reinsurance sector respondents did not suggest that losses from property-catastrophe events eroded capital to the point that cyber capacity was imperilled, but many indicated the potential for that sort of development to occur in the future. One of them noted the capital erosion over the past few years but also observed the simultaneous growth of capacity in the cyber reinsurance market: “I don’t think it’s entirely been a problem in terms of reducing the amount of capacity available and I also don’t think it’s entirely been a benefit in terms of causing people to seek diversifying business plans. It’s somewhere in the middle.”

While that dynamic may not be able to persist forever, it at least shows that natural catastrophe losses so far, despite significant quantum, have failed to achieve systemic reinsurance market effects. The other cyber reinsurer believes that natural catastrophe losses have “certainly influenced” the behaviour of some of their retrocession providers. He explains that “no capital has been withdrawn” but adds that none seemed to be coming in at the time (during the fourth quarter of 2022, following Hurricane Ian). In fact, he describes the market as “a bit in a shock state.” Again, the market quickly stabilised, but the shock was likely sufficient to be remembered for the next few years.

Another large cyber reinsurer noted the overall reduction of capital industry-wide by the natural disaster events since 2017 and adds that it affects all lines of business, not just cyber. This is a reasonable position, provided one recognises the lack of systemic effects. The wave of 2017–2022 catastrophe losses, which has cost the global insurance industry an aggregate $623.4 billion according to Munich Re NatCatSERVICE (2023b), has become a perception problem and a performance problem; and is more noteworthy for the secondary effects on the market that appear to influence the cyber re/insurance market’s access to capital.

4.3. Reinsurance Rate Movement and Opportunity Cost

The increased natural catastrophe rate of the past seven years has given rise to a positive side effect for the core global re/insurance market that could impede the flow of capital to cyber risks: Reinsurance rate increases. It is not unusual for risk transfer rates to increase after major loss events, as both cyber reinsurance and ILS manager respondents indicated during the interviews and which can be seen via the Guy Carpenter US Property Catastrophe Rate on Line Index. This had rate increases following Hurricane Andrew in 1992, the terror attacks of September 11th 2001, and Hurricane Katrina in 2005, not to mention the increases associated with more recent loss events (Guy Carpenter, 2022).

This dynamic results in an opportunity cost associated with a flight from loss-affected classes. If capital is allocated to cyber – and away from property-catastrophe risks – then they not only take on the risks associated with a relatively untested class of business, but they also lose the opportunity to benefit from an increasing rate environment. In this regard, the cyber insurance sector faces a problem common to emerging risks and classes of business, where capacity providers tend to embrace the opportunity they understand, particularly in a favourable rate environment.

Five ILS managers specifically cite the post-event increase in catastrophe reinsurance rates as an impediment to deploying to cyber (and other classes of business). According to one ILS manager, his ability to deploy to catastrophe risks in this environment has dulled end investor interest in cyber. “Right now,” he explains, “every dollar we get through the door, we can easily deploy” to property-catastrophe risks. Cyber, he continues, “is more difficult to find interesting because the investor can just allocate to nat cat, and they don’t need the complexity” of a new class of business, such as cyber. Further, with rate increases after heavy catastrophe loss years, end ILS investors want to participate in the improved rate environment. Another describes natural catastrophe business as “the engine,” as mentioned earlier, that is the original core business they presented to investors, and the area they know best. This leads not just to a decision involving the opportunity costs associated with the natural catastrophe/cyber allocation decision but also to the role of familiarity. ILS managers understand natural catastrophe risk, which almost always tilts them in that direction, particularly with regard to newer classes of business, like cyber. Even for theoretically similar risk profiles between a cyber transaction and a natural disaster transaction, one ILS manager says, “It’s a difficult call to make, particularly when the pricing is pretty close.”

Together, the increased attractiveness of catastrophe business in an environment with increasing rates and the tendency to stick with familiar classes of business can make it “a difficult time to try something new,” as one ILS manager puts it. Familiarity can be a powerful force, even when prevailing conditions over a period of years suggest moving to alternatives. According to one ILS manager, investors affected by natural catastrophe losses should be “biting your hand off” for opportunities in “a non-correlated market with a similar return profile.” In fact, other respondents do indicate that this is happening. Two participants say that natural disaster activity (and thus climate change) has not affected their appetite for cyber. There are instances where end investors like the ILS manager but not the catastrophe class of business. In fact, one such investor says that among his end investors, “there’s a strong, strong appetite for cyber irrespective of what’s happening in the broader property-cat markets.” Respondents with this view indicate that a further increase in the perspective that cyber risks are not correlated with financial markets would contribute to the increase in capital flows to cyber risks, a tendency that could be intensified by continued significant natural disaster activity.

Cyber reinsurance executives note that their companies have to engage in the same opportunity cost exercises as ILS managers, with six of the nine respondents speaking to this point. It is a core business that they know well and for which they have staffed and built the necessary infrastructure. There is a grim reality associated with the commitment to property-catastrophe risk, balancing recent losses with price increases. One reinsurance respondent observes, “It’s as attractive as it can be after six years of heavy losses.” Several others specifically note rate increases and better margins. Further, the sheer size of the catastrophe market can prove difficult to tame. One respondent, for example, has seen property-catastrophe rates become more attractive and reports that it has made it difficult for him to grow his cyber reinsurance book of business. Not only are the rates in property-catastrophe attractive, the sector is much larger, which makes growth easier to attain and manage.

The opportunity cost associated with catastrophe versus cyber risk, as an impediment to the flow of capital to cyber risks, involves the confluence of the near-term reinsurance rate environment, familiarity with the class of business, and an opportunity for returns that is easier to understand than those possible from a new and emerging risk. Further, the opportunity cost and questions about recent ILS manager and reinsurance property-catastrophe performance indicate that the second-order effects of natural disasters – and thus climate change – on the availability of capital for cyber reinsurance is a more imminent concern than the possible effects of a massive erosion of capital. If there is an upside, it is that these second-order effects can serve as a “canary in the coal mine,” alerting the industry to capital scarcity problems before they arise with unprecedented scale as the result of a major natural disaster.

5. Climate Change and Cyber Security: No Longer a Missing Link

The lack of clear causation or discrete levers with regard to the interplay between natural disasters (and thus climate change) and the availability of capital to support cyber re/insurance risk transfer should come as no surprise. The causal connection chain from climate change to natural disaster activity to insurance industry impacts to cyber insurance capital availability to overall cyber and economic security is packed with nuance, exceptions, and mitigating factors. While the connection may look tenuous due to the length of the chain and some of the disagreement among respondents, the overarching sentiment suggests the connection is sufficiently meaningful to warrant engagement with it. The strength of responses in support of the risk of climate change-related influence on cyber economic security is nearly impossible to ignore. While not all participants have witnessed impediments to the flow of capital, those who have are the rule rather than the exception. Their experience may change over time, with the assumption that the investors in cyber now are pioneers and more will follow. However, the early state of any transition is delicate, and such prospects could be extinguished by an uptick in major landfalling hurricanes.

The prospect of a major natural disaster – or a series of them – impacting global re/insurance capital so severely as to create a systemic event for cyber re/insurance appears to be extremely remote. To erode enough capital for the cyber re/insurance sector to be affected materially, the hypothetical event or series of events mentioned above would have to be cataclysmic and truly without precedent. Could a $250 billion property-catastrophe loss year cause a sharp reduction in risk capital allocated to cyber re/insurance? What about twice that amount? Perhaps, but the broader systemic implications cannot be gauged realistically, which casts doubt over any specific guesses for the cyber sector under such circumstances. For now, the problem remains theoretical.

The impact of significant natural disasters on decisions regarding which risks to deploy capital to, on the other hand, is one of near-term practicality. An increase in natural catastrophes leads to increases in reinsurance rates, evident over the past thirty years, and further back in history. End capital seeks returns, which can result in a decision to divert capital flows away from cyber risks, given not just the pricing associated with property-catastrophe transactions but also the familiarity the market has with them. Essentially, the market opportunities associated with climate change represent a clear economic threat via the cyber domain. While this second-order effect lacks the direct impact of a significant loss of capital from a headline-grabbing natural disaster, it nonetheless results in economic security vulnerability relative to the threat of cyber-attack. Not all respondents in the reinsurance and ILS categories hold this view, but the majority do, as measured not just by the number of responses but by the premium for cyber reinsurance executives participating and AuM for ILS managers.

Of course, natural catastrophe losses could become sufficiently extreme that they force a change in capital flows away from the existing market, and potentially to cyber risks, provided that the ILS market can become comfortable with the class of business and modify existing operating infrastructure appropriately. The decision to leave the natural catastrophe space – which some respondents referenced – is not a hypothetical alternative. However, the decision to exit the natural catastrophe market does not ensure that the capital would remain in the ILS market, let alone be deployed to cyber. Consequently, it is of paramount importance that the cyber re/insurance market develops dedicated sources of capital to support their market. While some of that could come from the ILS market – six ILS respondents remain quite bullish, and they represent roughly 30% of worldwide ILS AuM – the overwhelming influence of natural disaster activity and climate change in general on the ILS market suggests that some diversification of capital providers would be an important risk management measure.

Climate change and cyber are often cited as two of the most important systemic threats in the world. Both, for example, are enshrined in the 2022 US national security strategy and the 2021 Russian national security strategy, among many others. Separately, these two systemic risks are difficult to deal with. The fact that they may be interrelated is cause for even greater alarm. That changes in the weather could seemingly disrupt the cyber domain suggests not just a deeper impact of climate change but simultaneously a broader vulnerability to the cyber domain than previously believed. The focus on economic security does suggest more manageable remediation than the more difficult threats associated with both climate change and cyber security, and a failure to take advantage of the existing re/insurance infrastructure to support economic security in the cyber domain in the face of climate change represents the unnecessary assumption of a risk that could rather easily be hedged.

6. Conclusion

Climate change poses an indirect threat to cyber security, although via a causal chain with several links. This can make it easy to miss the connection between the two, particularly in light of the many varied and significant ways that climate change can affect all major security sectors. The connection may be difficult to spot, but it clearly exists, and it could have significant implications for cyber security in the years to come. Existing shortages of capital for cyber re/insurance protection could be exacerbated by the effects of climate change. The fact that capital is both in short supply and could be further constrained by factors unrelated to cyber risk itself suggests a broader systemic problem to be explored. The fact that there is an existing market to address the flow of capital to cyber risks and even preliminary market participants indicates that this problem is indeed manageable.

The mixed messaging from the market can be problematic. There was no clear consensus from cyber reinsurance executives or ILS managers about the connection between climate change and cyber security risk, although a majority of respondents by count and by financial metrics do see cause for concern. This may be enough to ring the alarm about a new form of economic risk to be contemplated in cyber security strategy. The fact that it is not a headline-grabbing risk – such as an earthquake destroying data centres or even a typhoon obliterating large volumes of insurance industry capital – makes it even more concerning, as subtle risks often fail to get the attention they deserve.

There are barriers to the flow of capital into the cyber re/insurance market in general, as the historical literature reveals, and the opportunity costs associated with capital deployment in an active natural disaster environment further complicate the matter. Rather than rely on the momentum of cyber-ILS pioneers or assume that capital flows will be diverted from the natural catastrophe market at some point in the future due to the presumed uninsurability of natural disaster risk, re/insurance capital for cyber risks is a problem that must be addressed in the near term and (to the extent possible) separately from the dynamics of the property-catastrophe market. There is no doubt that additional sources of capital for cyber re/insurance risk transfer will become increasingly important, and the recent shortages that have constrained the growth of this market could give way to genuine and profound economic security problems over the next few years.

There is no substitute for action with regard to the problem of climate change as a cyber security risk. The fact that the connection centres on an economic security lever with centuries of market precedent for covering major risks – i.e. the insurance industry – should make the challenge less menacing. The market as it exists today may not be able to solve the problem on its own, however, as evidenced by the capital shortages referenced in this article. Whether through new entrants or government support, a new market force will be necessary to help this solvable problem receive the attention it needs.