In the face of COVID-19, most countries imposed wide-ranging containment measures and mobilized colossal sums of money to fight the pandemic and mitigate its devastating health and economic effects. At the same time, despite numerous calls for international solidarity, multilateral action to counter the pandemic and its detrimental consequences has been rare (Barnett Reference Barnett2020; Johnson Reference Johnson2020). An exception is the European Union (EU). After a bumpy start, including uncoordinated border closures and other forms of nationalist reactions, the world's most integrated regional block took important common initiatives over the course of 2020, including the joint procurement of vaccines and the setting up of the €750 billion recovery plan, ‘Next Generation EU’.

The support of this latter measure is astonishing in various respects. First, in times of crises, in-group interests are generally expected to outrank more universal forms of solidarity (Calhoun Reference Calhoun2002; Wamsler et al. Reference Wamsler2022). Secondly, by signalling an exceptionally high level of solidarity, the recovery programme does not seem to conform to postfunctionalist expectations of a ‘constraining dissensus’ (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), often argued to hinder European and international cooperation in times of politicization (see also De Vries, Hobolt and Walter Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021; Pevehouse Reference Pevehouse2020; Walter Reference Walter2021). Thirdly, ‘Next Generation EU’ breaks with the austerity policies of the Eurozone crisis, not least by enabling the issuance of common EU debt. Against this backdrop, we analyse support for European financial and medical aid during the COVID-19 crisis.

The literature on support for redistribution in the EU has largely focused on what, in the context of welfare state research, has been called the ‘redistribution from’ dimension (Cavaillé and Trump Reference Cavaillé and Trump2015), capturing respondent-specific characteristics on the donor side. Research has shown how economic self-interest, ideological preferences and personal dispositions affect citizens' support for international solidarity (Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2014; Kleider and Stoeckel Reference Kleider and Stoeckel2019; Kuhn, Solaz and van Elsas Reference Kuhn, Solaz and van Elsas2018; Nicoli, Kuhn and Burgoon Reference Nicoli, Kuhn and Burgoon2020). However, the recipient side of international solidarity, or rather the donor's perception of the recipient, has so far largely been ignored. In this article, we call this the ‘redistribution to’ dimension to capture how the orientations and relations towards possible recipients (Cavaillé and Trump Reference Cavaillé and Trump2015, 148) may affect donors' solidarity. The neglect of the ‘redistribution to’ dimension is troubling, not least because we have long since known that sharing resources among actors constitutes a ‘social relationship’ between ‘ego’ and ‘alter’ in which the former orients their behaviour towards the latter, and vice versa (Weber Reference Weber1978, 27). Accordingly, to fully understand solidarity at the international level, one needs to move beyond an ‘ego’-focused perspective and take perceptions of, and the relationship to, the ‘alter’ into account.

In this article, we theorize and empirically analyse how characteristics on the recipient side affect support for different forms of international aid. Building on domestic welfare state and international development aid research (Bayram and Holmes Reference Bayram and Holmes2020; van Oorschot et al. Reference Van Oorschot2017), we propose two central ‘redistribution to’ dimensions that influence donors' behaviour. These two dimensions refer to the situational and to the relational elements of a social interaction. First, in deciding whether to provide aid, situational elements like the level of need and a recipient's responsibility for the situation matter. Secondly, solidarity constitutes a social relationship between a donor and a recipient. As such, the scope of solidarity is often defined by the boundaries of politically and socially defined communities (Bayertz Reference Bayertz and Bayertz1999). The relational characteristics can be constituted through joint membership in a political community, by shared values and norms, and by a joint readiness to reciprocate aid.

We expect that, first, the level of need matters; in particular, health emergencies should outweigh more long-term economic challenges. Secondly, donors' evaluations of recipients' responsibility for, or control over, their situation should affect solidarity. These first two situational factors are often referred to as constituting ‘deservingness’ in a narrow sense (Petersen et al. Reference Petersen2012). Thirdly, while international settings may lack the deep social bonds, such as a shared national identity, that are often argued to constitute the glue tying citizens in domestic welfare states together, citizens may still feel connected to other countries with whom they share membership of an alliance or a political community, such as the EU. Fourthly, going beyond formal membership in a community or an alliance, the respect for common normative principles should increase support for a potential recipient of aid. Especially in a highly integrated system like the EU, adherence to community norms and standards, such as democracy or the rule of law, should increase the willingness to provide aid. Finally, in the context of repeated interactions among (member) states, we expect citizens to value reciprocity and the provision of mutual support in times of crisis. We term the latter three factors ‘relational’ (as opposed to ‘situational’), as they capture more general relations between a recipient and a donor. Moreover, we argue that the ‘redistribution to’ dimension is an important moderator for the effect of the ‘redistribution from’ dimension (that is, individuals' characteristics) of solidarity.

We test these ‘redistribution to’ explanations for international solidarity with survey data from Germany by running factorial survey experiments on support for medical and financial aid to other (EU member) states. Our data come from two original surveys with about 4,000 respondents each, collected during the first (April/May 2020) and the third (May 2021) infection waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. Germany is the largest net contributor to the EU budget, and the country also has the largest intensive-care capacity in Europe, which was a critical resource for providing medical aid to other countries during COVID-19 (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer2020). During the crucial second half of 2020, Germany held the rotating presidency of the Council of the EU. Given the country's political and economic weight in the EU, we consider Germany's support a necessary condition for the establishment of European aid schemes.

Our experiments underline that accounting for the ‘redistribution to’ dimension is indispensable for understanding European solidarity. We find that both situational and relational characteristics affect citizens' readiness to support aid. In particular, first, the types and levels of need matter. Citizens not only display stronger support for medical than for financial aid, but are also more likely to support less wealthy states, ceteris paribus. Secondly, citizens are more willing to help those who they consider to be victims of bad luck instead of bearing responsibility for their situation. Thirdly, membership in a political community matters, albeit to a varying extent for medical and financial aid. Fourthly and fifthly, citizens reward other member states that honour community norms, such as the rule of law, and who value reciprocity. Finally, our data allow us to show that altruism and, to a lesser extent, European identity are important moderators for the effects of situational and relational recipient characteristics. In particular, altruists are more responsive to information about recipients than people who report lower levels of altruistic orientations.

Our findings have important implications. First, getting a better understanding of public opinion seems indispensable for reconciling the demands for international cooperation with democratic decision making. This is important, not least when it comes to combatting and preventing future pandemics (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke2021). Secondly, our findings highlight that solidarity is no one-way street concerning only the donor side. States can earn support by playing by the rules of the game to which they, in the case of the EU, have agreed through accession, as well as by respecting the normative foundations of the community (Schimmelfennig Reference Schimmelfennig2001). This observation also matters for the current debate on how to react to democratic backsliding, both in the EU and beyond (Kelemen Reference Kelemen2020).

Explaining Support for European Solidarity: The Missing ‘Redistribution to’ Side

Previous research on European solidarity has focused on the ‘redistribution from’ side (Cavaillé and Trump Reference Cavaillé and Trump2015), highlighting the role of individual attributes on preference formation towards international transfers. In addition, some authors have studied the political and institutional side of European solidarity (Bauhr and Charron Reference Bauhr and Charron2018; Stoeckel and Kuhn Reference Stoeckel and Kuhn2018). The focus of these studies has mainly been on support for financial aid, whereas other forms of aid within the EU have only been addressed more recently (see, for example, Baute and de Ruijter Reference Baute and de Ruijter2021; Beetsma et al. Reference Beetsma2021; Bremer et al. Reference Bremer2021; Díez Medrano et al. Reference Díez Medrano, Ciornei, Apaydin and Recchi2019; Nicoli, Kuhn and Burgoon Reference Nicoli, Kuhn and Burgoon2020).

From this literature, we have learned that accounts limited to ‘egotropic’ material self-interest, traditionally held to explain redistributive preferences in the context of the nation state (Bellani and Scervini Reference Bellani and Scervini2015; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2001; Kuziemko et al. Reference Kuziemko2015; Meltzer and Richard Reference Meltzer and Richard1981), are inadequate in capturing European patterns of solidarity. Instead, the literature has stressed the importance of non-economic cultural orientations or dispositions, such as altruism, cosmopolitanism (Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2014; Kuhn, Solaz and van Elsas Reference Kuhn, Solaz and van Elsas2018) and political ideology, with the latter conditional on social class (Kleider and Stoeckel Reference Kleider and Stoeckel2019). Early studies on EU redistribution preferences during the COVID-19 pandemic have again focused on the ‘redistribution from’ dimension and have largely replicated earlier findings (Bauhr and Charron Reference Bauhr and Charron2021; Baute and de Ruijter Reference Baute and de Ruijter2021).

In contrast, the ‘redistribution to’ dimension of solidarity (Cavaillé and Trump Reference Cavaillé and Trump2015) is still largely overlooked in the literature on EU and international solidarity. Moreover, while there are some exceptions in the area of development aid (Bayram and Holmes Reference Bayram and Holmes2020; Paxton and Knack Reference Paxton and Knack2011), we still lack a careful systematization of this component for the transnational context more broadly.Footnote 1 This shortcoming is surprising given that sharing resources, per definition, implies a ‘social relationship’ between a donor (‘ego’) and a recipient (‘alter’), who interact in a specific institutional, as well as situational, context (Weber Reference Weber1978, 27). Research on national welfare states has presented abundant evidence that perceptions of the recipient side contribute to shaping citizens' attitudes on redistribution (van Oorschot Reference Van Oorschot2006). Yet, given that the focus of the extant literature is largely on inter-individual aid, albeit partially mediated by state administrations, we still lack an understanding of whether and how these insights can be translated to international forms of solidarity.

Solidarity constitutes a social relationship between at least two actors. Based on the idea of solidarity as a social relationship, we propose two dimensions to capture the ‘redistribution to’ side of international solidarity. These two dimensions relate to the situational and the relational characteristics of a social interaction, respectively. The situational characteristics of international redistribution are constituted, first, by the level and kind of need. Secondly, the potential recipients' perceived control over, or responsibility for, their distress can be expected to affect a potential donor's readiness to help. These two situational factors are often argued to constitute the perceived ‘deservingness’ of the recipient side (Petersen et al. Reference Petersen2012). Beyond such situational characteristics, potential donors and recipients stand in a more general social relationship, oftentimes shaped by political institutions and communities (Bayertz Reference Bayertz and Bayertz1999). In such a reading, group membership, or a sense of community, delineates the scope of redistribution. This dimension is relational, as it refers to the donor's evaluation of a recipient's group membership. Moving the understanding of the ‘alter’ in a dyadic exchange of support from individual agents to whole countries requires a reconceptualization of group membership. Accordingly, international solidarity is affected by the degree of political community, which is characterized not only by formal membership in a political organization or alliance, but also by respect for shared values and norms, as well as the willingness to reciprocate aid. In sum, we distinguish five concepts reflecting those situational and relational characteristics, which we expect to affect preferences for solidarity: need, control, membership in a political community, shared norms and reciprocity.

First, we know from the literature on development aid that different levels of need affect citizens' readiness to support aid (Paxton and Knack Reference Paxton and Knack2011). Need also takes a prominent place in multilateral disaster aid (Dellmuth et al. Reference Dellmuth2021). Moreover, recent research shows that when it comes to joint medical procurement, European citizens favour priority supply to the most in-need countries over an equal distribution of medicines (Beetsma et al. Reference Beetsma2021). Thus, higher distress increases perceptions of legitimate ‘deservingness’. The salience of need in an international context ties in with findings from evolutionary psychology (Jensen and Petersen Reference Jensen and Petersen2017; Petersen et al. Reference Petersen2011; Petersen et al. Reference Petersen2012) and can even be linked to a moral philosophical ‘obligation to assist’ (Singer Reference Singer1972). Accordingly, we expect need to positively affect support for both medical and financial aid in the EU:

HYPOTHESIS 1a (H1a): The higher the perceived levels of need, the stronger citizens' support of aid.

The pandemic has caused both medical and economic need. According to Jensen and Petersen (Reference Jensen and Petersen2017, 71), health-related emergencies are more likely to trigger support compared to economic hardship due to a psychological bias that ‘tag[s] sickness implicitly as a need that is randomly caused’. Indeed, using experiments, they show empirically that humans process illness differently than unemployment, leading to stronger support for public healthcare policies compared to unemployment benefits. We therefore expect greater support for medical than for financial aid in the EU:

HYPOTHESIS 1b (H1b): Support for medical aid is higher than support for financial aid.

Relatedly, economists and social psychologists have long emphasized the importance of recipients' responsibility for, or control over, their situation in explaining redistribution preferences. Within nationally institutionalized welfare systems, work, effort or performance, on the one hand, have been pitted against (bad) luck or lack of opportunity, on the other (Alesina and La Ferrara Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2005; de Swaan Reference De Swaan1988; Fong Reference Fong2001; Hoffman and Spitzer Reference Hoffman and Spitzer1985; Lefgren, Sims and Stoddard Reference Lefgren, Sims and Stoddard2016). The key argument is that – despite notable cultural differences, for instance, between the United States and Europe (Alesina and Angeletos Reference Alesina and Angeletos2005, 960; Bénabou and Tirole Reference Bénabou and Tirole2006, 700) – beliefs about the reasons for inequality drive citizens' support for redistribution. For instance, Fong (Reference Fong2001, 225) highlights that ‘[p]eople may prefer more redistribution to the poor if they believe that poverty is caused by circumstances beyond individual control’. While most of this literature focuses on redistributive measures inside of nation states, Schneider and Slantchev (Reference Schneider and Slantchev2018, 16), for example, make a similar deservingness argument for German preference formation during the Eurozone crisis: ‘Since they [Germans] blamed the Greeks for the crisis [and did not believe that it would affect them] 76 percent did not want to help Greece.’ We thus expect that perceptions of responsibility for a situation of need affect support for aid:

HYPOTHESIS 2a (H2a): The more limited a recipient's responsibility for, or control of, the situation, the higher the support for aid measures.

In this conventional understanding, ‘control over one's situation’ is backward-looking: did a state put in the effort that could be reasonably expected to avoid misfortune, be it sound public finances or a well-run public health system? However, in the context of public policy and administration, effort can hardly be understood as a one-off investment, but should be considered an ongoing process of capacity building. The concept of ‘control’ should therefore also include a forward-looking capacity dimension. Development scholars, for example, consider the effort a recipient country makes into putting aid to good use. Bayram and Holmes (Reference Bayram and Holmes2020, 832) show that US citizens are more willing to grant foreign aid to countries that ‘establish a national development program, set clear policy priorities and monitoring programs’. Aid needs to be put to good use, and the capacity to do so effectively is distinct from pre-crisis efforts. We therefore expect citizens to be more willing to grant aid to recipient countries with higher administrative capacity:

HYPOTHESIS 2b (H2b): The higher a recipient's perceived capacity to use aid effectively, the higher the support for aid measures.

Besides these situational aspects, relational characteristics should inform citizens' readiness to support international redistribution and aid. The fundamental social bonds between the members of a group are often understood as a key condition for solidarity (Bayertz Reference Bayertz and Bayertz1999, 3). In the welfare state literature, such a ‘homophily’ logic is commonly termed ‘identity’ and relates to the idea of social closure – non-nationals are often excluded from the redistribution of goods in a society, a phenomenon termed ‘welfare chauvinism’ (Kuhn, Solaz and van Elsas Reference Kuhn, Solaz and van Elsas2018; Mewes and Mau Reference Mewes and Mau2013). The homophily or similarity principle, which can be traced back to the work of Aristotle (McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001), is a decisive mechanism to delineate the social boundaries of support. It implies that the willingness to support others increases with greater political proximity, from a small-scale local or municipal community, to the nation state, the EU and more distant countries across the globe:

HYPOTHESIS 3 (H3): Donors are more likely to support aid to recipients with whom they share membership in a political community.

Next to political proximity as captured by formal community membership, we suggest that informal practices and, in particular, shared communal norms matter for shaping redistribution preferences. The welfare state literature emphasizes that those ‘who are … compliant and conforming to our standards’ (van Oorschot Reference Van Oorschot2006, p. 26) are particularly deserving. Moving from the individual or group level of domestic welfare states to the macro level of international aid between nation states, we argue that sharing normative standards is an important condition for providing help. States supporting each other should also share common normative standards. Violating normative principles like the democratic rule of law is likely to undermine the willingness to help. This should be especially true in the case of a highly integrated political system like the EU, built on common norms and values (Schimmelfennig Reference Schimmelfennig2001). The democratic backsliding of some EU member states is a stark case of violating community norms (Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022; Kelemen Reference Kelemen2020). In the summer of 2021, the violation of another norm – non-discrimination of (sexual) minorities – caused a heated debate in the European Council. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte even suggested that Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orbán should reconsider Hungary's EU membership after passing discriminatory legislation against LGBTQI+ persons. Heading the government of a state that is a net contributor to the EU budget, Rutte expressed frustration that Dutch taxpayers' money would be redistributed to a country in violation of civil liberties. Therefore, we expect that a recipient needs to accord to some communal norms to be perceived as legitimately deserving aid:

HYPOTHESIS 4 (H4): Citizens are more likely to support aid to other member states that display respect for community norms.

Finally, reciprocity, a norm deeply engrained in human nature (Bowles and Gintis Reference Bowles and Gintis2011), seems to be valued by citizens when it comes to redistribution. Reciprocity can be retrospective or future oriented. If those in need have contributed to the common good before, they have already ‘earned’ support; alternatively, they may be ‘expected to be able to contribute in the future’ (van Oorschot Reference Van Oorschot2006). In the EU's political system, member states interact constantly and repeatedly. It is a setting in which member states (are supposed to) provide reciprocal support to each other over time and across different policy fields. Governments and citizens remember how their peers acted in the past, with possible lasting effects on public opinion. A decade on, Southern Europeans still remember the conditionality that came with bailout programmes during the Eurozone crisis as an unfair imposition from abroad (Morlino and Raniolo Reference Morlino and Raniolo2017). Meanwhile, many in Western Europe begrudge the fact that Central Eastern member states refused to welcome refugees during the migration crisis of 2015–16. We therefore expect that citizens are more willing to provide aid to member states that acted in solidarity during previous crises, reflecting a mechanism of reciprocity:

HYPOTHESIS 5 (H5): Citizens are more likely to support aid to states that they perceive to honour principles of reciprocity.

In the ‘redistribution from’ perspective, scholars have emphasized the importance of the donor's individual dispositions, such as altruistic and cosmopolitan orientations, or European identity. Altruism refers to a general disposition to help others, even if this implies a potential cost and effort for an actor (Monroe Reference Monroe1994). Cosmopolitanism reflects an orientation towards the world, which can be distinguished from a focus on the narrow local or regional context, resulting in a distinction between ‘cosmopolitans’ and ‘locals’ (Merton Reference Merton1968, 392). Finally, identity refers to a feeling of belonging, which might again be either rather local/national or conform to a European identity. All three individual dispositions have been shown to matter for European solidarity during the Eurozone crisis (Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2014). The relationship between these ‘redistribution from’ determinants and the ‘redistribution to’ determinants can either have an additive or multiplicative effect on European solidarity. While both seem plausible, recent theories of action have emphasized the interactive effect of personal characteristics and situational cues in explaining pro-social behaviour (Kroneberg, Yaish and Stocké Reference Kroneberg, Yaish and Stocké2010). For instance, in a study on the rescue of Jews in Nazi Germany, Kroneberg, Yaish and Stocké (Reference Kroneberg, Yaish and Stocké2010) show that people with strong internalized pro-social norms disregarded situational risks in their decision to help Jews. This suggests that the situational characteristics of recipients will be less important if people have strong altruistic or cosmopolitan orientations. Conversely, it is also plausible to assume that people without a minimal interest or motivation to help others will be less likely to respond to situational cues (Diekmann and Preisendörfer Reference Diekmann and Preisendörfer2003), such as whether a potential recipient bears some responsibility for their situation. In other words, situational characteristics, for instance, unmet deservingness criteria, could have a stronger effect on people with more altruistic or cosmopolitan dispositions, or those with a stronger European identityFootnote 2:

HYPOTHESIS 6a (H6a): The effects of ‘redistribution to’ factors on European solidarity will be stronger if respondents have stronger altruistic or cosmopolitan orientations, or a European identity.

HYPOTHESIS 6b (H6b): The effects of ‘redistribution to’ factors on European solidarity will be weaker if respondents have stronger altruistic or cosmopolitan orientations, or a European identity.

In the following, we introduce our case before moving to the empirical analysis.

EU Solidarity during COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has created both a health and an economic crisis, which have affected European countries quite differently. The capacity of public health systems to absorb large numbers of COVID-19 patients varied greatly, and so did the ability to raise ‘cheap’ money to finance lockdowns imposed to limit the spread of the virus. After an initial period of nationalist reflexes, including the uncoordinated closing of borders, EU member states started to provide bilateral medical support, including the provision of medical equipment and the relocation of patients. In June 2020, the European Council agreed on the €750 billion recovery programme, ‘Next Generation EU’, which provided €390 billion in grants and €360 billion in loans to member states (Hinarejos Reference Hinarejos2020). Issued in conjunction with the EU's new multi-annual budget, the recovery plan signalled the resolve of EU member states to fight the consequences of COVID-19 together.

‘Next Generation EU’ was negotiated under the European Council presidency of Germany, whose governments and public opinion during the Eurozone crisis had been opposed to large-scale redistribution (Degner and Leuffen Reference Degner and Leuffen2020; Schneider and Slantchev Reference Schneider and Slantchev2018), aligning with fiscally conservative positions of other Northern member states, such as the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Austria. However, in what can be described as one of the most noteworthy policy shifts in recent EU history, German Chancellor Angela Merkel abandoned the camp of the ‘frugal’ countries, championing the ‘Next Generation EU’ programme. Explaining the German policy shift, Crespy and Schramm (Reference Crespy and Schramm2021, 16) show that the German government not only emphasized Germany's economic self-interest in preventing the EU's disintegration, but also framed the COVID-19 crisis as ‘an exogenous shock not involving any responsibility or wrongdoing’. Chancellor Merkel thus employed a framing that ties in with the argument that situational characteristics help explain international solidarity (Kneuer and Wallaschek Reference Kneuer and Wallaschek2022).

Research Design

We use a factorial survey or vignette design to study the ‘redistribution to’ dimension of European solidarity (see also Alves and Rossi Reference Alves and Rossi1978). Factorial survey experiments are well suited for assessing the ‘judgment principles that underlie social norms, attitudes, and definitions’ (Auspurg and Hinz Reference Auspurg and Hinz2015; Jasso Reference Jasso2006). This approach combines the advantages of an experimental design with those of survey research, thereby aligning internal and external validity. Respondents are provided with multidimensional descriptions of hypothetical situations (vignettes) describing countries in need. The respondents are then asked whether they would be willing to support a financial or medical aid initiative. Support is measured on a seven-point Likert scale (‘not support at all’ = 1; ‘strongly support’ = 7). The dimensions of the vignettes are systematically varied, reflecting variations in the experimental stimuli, and randomly assigned to respondents. This allows for estimating the causal effect of situational attributes on the average support of either medical or financial solidarity.

We included four different experiments in two representative surveys fielded in April/May 2020 and May 2021, mirroring the first and third waves of the pandemic in Germany. Additional vignette experiments with corresponding results were conducted in November 2020 and are reported in Online Appendix L and discussed in the robustness section.Footnote 3 The surveys were fielded using the Respondi online access panel in Germany, implementing quotas for age, gender, education and region, and included 4,799 (first survey) and 4,027 (second survey) respondents. Participants were older than eighteen years, German speaking and residents of Germany (thus including German-speaking migrants). Online Appendix C compares the composition of our samples with the overall German population based on census data. The comparison shows that our data represent the German population relatively well. Yet, to correct for small deviations from the general population and a deliberate oversampling of East Germany, we used weights in all analyses. While the composition of our sample cannot assure representativeness, the experimental design assures the high validity of our results.

The first experiments focus on direct bilateral medical and financial aid, varying the political proximity/membership and control dimensions; we also account for the cost dimension, which has proved relevant not only for support for European solidarity (Lengfeld, Kley and Häuberer Reference Lengfeld, Kley and Häuberer2020), but also in other policy areas, including climate policies (see, for example, Bechtel and Scheve Reference Bechtel and Scheve2013; Beiser-McGrath and Bernauer Reference Beiser-McGrath and Bernauer2019). The second experiments directly build on and extend the first experiments. Here, we explore indirect aid via the EU, carefully considering all situational and relational recipient-country characteristics except membership. In these experiments, we were primarily interested in zooming in on the effects of the ‘redistribution to’ variables outlined earlier. To reduce the complexity and length of the vignettes, we did not include the costs and risks of the policy measures.Footnote 4

In the first survey, fielded six weeks into the first German lockdown, we included one vignette about medical solidarity (Vignette Medical Aid 1 [VMA1]) and one vignette about financial solidarity (Vignette Financial Aid 1 [VFA1]). Both vignettes ask respondents whether they would support Germany providing bilateral aid. The former describes a situation in which a region is in need of ventilators; the second describes a situation in which a region is in need of financial assistance (for descriptions, see Table 1; for the wording of the vignettes, see Online Appendix A). In both experiments, we varied the potential recipient's proximity or membership in different political communities by describing different political entities in need of support (‘German region’, ‘EU country’ or ‘non-EU country’), the recipient government's preparedness for the crisis (control) with respect to both health and fiscal policies (‘Public health system’ and ‘Fiscal discipline’), and the costs or risk of the policy intervention for the donor region, in which the respondent resides. Thus, each vignette contained three factors, which results in a universe of twelve (2 × 2 × 3) possible scenarios for either medical or financial solidarity. Each respondent saw one medical and one financial vignette only.

Table 1. ‘Redistribution to’ dimensions as applied to medical and financial aid in the April 2020 and May 2021 vignettes

The vignettes from the May 2021 survey focus on EU aid schemes designed to help member states in need. The financial vignette (Vignette Financial Aid 2 [VFA2]) asks whether an EU member state should receive money from the ‘Next Generation EU’ programme. The medical vignette (Vignette Medical Aid 2 [VMA2]) presents a hypothetical EU programme providing medical equipment and personnel to member states with very high COVID-19 infection rates. In both vignettes, we vary five dimensions, creating a universe of thirty-two (2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2) possible vignette combinations. Each respondent was randomly assigned to one medical and one financial vignette; the order in which respondents viewed the vignettes was randomized. The level of need is reflected in a country's wealth (‘rich’ versus ‘poor’). Whether a country has been fast or tardy in adopting measures to fight the pandemic pertains to the control dimension in a retrospective way (‘COVID-19 policy’). Moreover, we add a forward-looking measure of control, distinguishing whether or not a capable public administration assures a solid implementation of the measures (‘Administrative capacity’). While the financial vignette speaks of administrative capacity in general, the medical vignette specifically refers to the capacity of the public health sector. The community norms dimension reflects whether the country honours democratic norms and the rule or law, or fails to do so (‘Rule of law’). Finally, we address reciprocity by experimentally varying whether a country has contributed strongly or only weakly to EU refugee-relocation schemes in the past (‘Refugee admission’). During the 2015/16 refugee crisis, Germany was one of the EU member states that admitted the largest number of refugees in Europe (Eurostat, 2016). Given the high public salience of migration, we assume that there is a general awareness among respondents that some EU member states have not ‘adequately’ contributed to the admission and redistribution of refugees within the EU. Acceptance of refugees therefore signals a readiness to carry a part of a shared burden, comparable with the COVID-19 health crisis.

To measure support for the solidarity initiatives, we estimate ordinary least square (OLS) regression models. Two-tailed statistical tests are used in all analyses. Our main models include 4,775 (Survey 1) and 4,016 (Survey 2) respondents who answered our dependent variables. In Online Appendix F, we report models with additional control variables and model-specific listwise deletion of observations with missing values. To facilitate interpretation of the effect sizes, in the Online Appendix, we additionally plot marginal effects from linear probability models for the dichotomized dependent variables (coded ‘1’ if respondents support aid initiatives and ‘0’ otherwise) for all experiments (see Online Appendix H). In addition, we perform subgroup analyses to show how variables identified as important by the ‘redistribution from’ literature – altruism, cosmopolitanism and EU identity – interact with the recipient characteristics of the vignettes.

Results

Figure 1 highlights that 63 per cent of respondents support medical and 44 per cent support financial aid directed at other EU states in April/May 2020, based on the collapsed dependent variable. We find a similar pattern when it comes to access to EU aid programmes in May 2021, where respondents are again more willing to offer medical compared to financial aid (it should be noted that the results are not fully comparable over time, as the underlying vignettes differ).

Fig. 1. Support for medical and financial aid in Germany in April/May 2020 and May 2021.

Notes: Sample limited to the EU treatment only. April/May 2020: n (medical aid) = 1,568 and n (financial aid) = 1,605; May 2021: n = 4,023. Response categories: 1–3 = ‘not support aid’, 4 = ‘neither’, 5–7 = ‘support aid’.

We take the higher level of support for medical aid as a first, cautious indication that citizens consider need levels when forming their preferences regarding international assistance: they are more likely to help in the face of existential health threats than in cases of economic hardship. While this interpretation echoes what we know about solidarity in the context of the welfare state and corresponds to expectations from moral philosophy, the pattern may also signal a stronger support for in-kind as compared to financial assistance. Therefore, in VMA2 and VFA2, we operationalized the need requirement more directly through EU member states' level of wealth. Backing the descriptive results, the experiments do indeed reveal that respondents are less likely to express support for aid to more wealthy countries. This applies to both medical and financial aid (see Figure 2), lending support to hypotheses H1a and H1b.

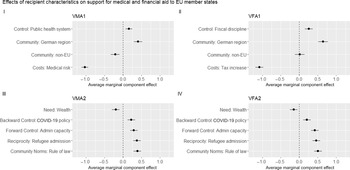

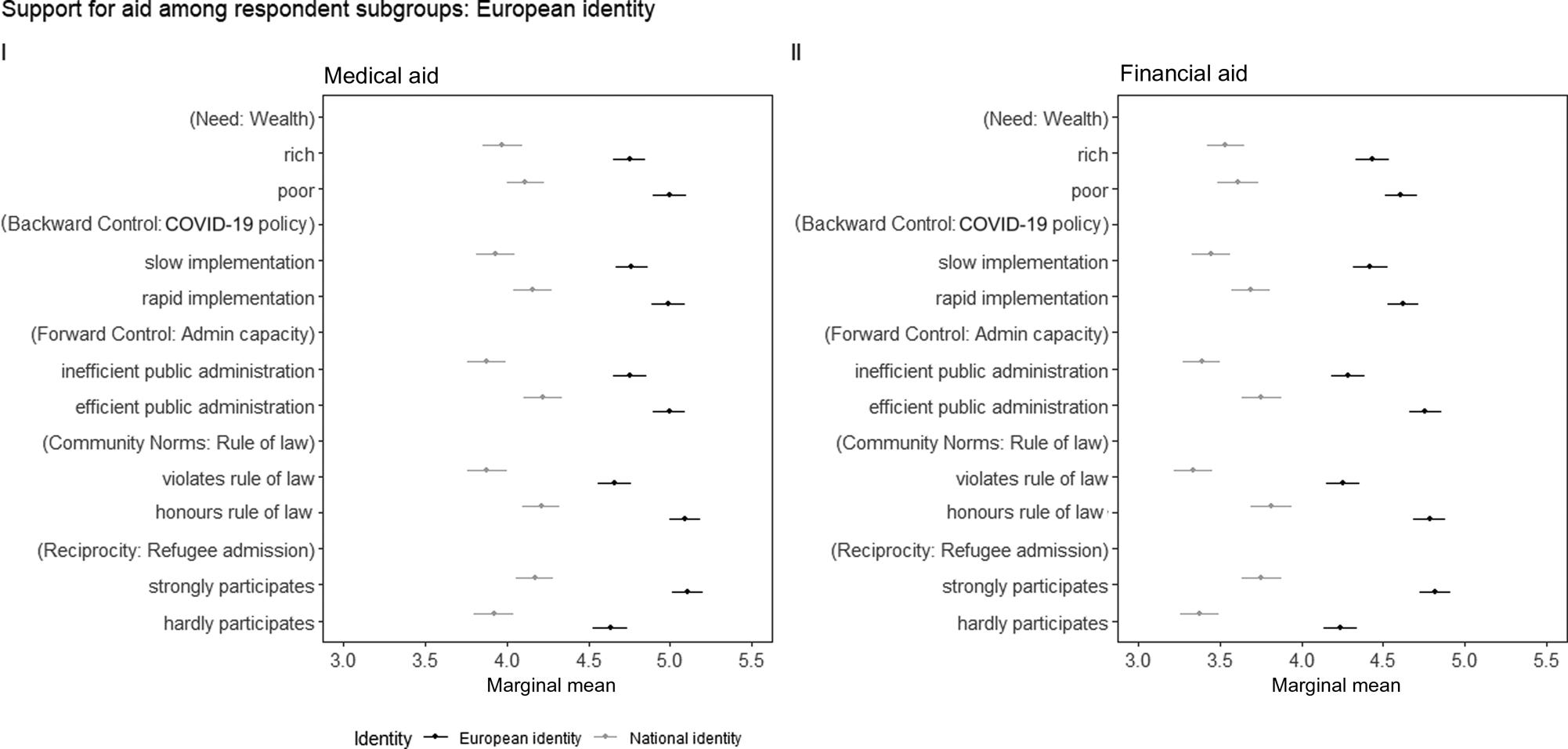

Fig. 2. Effects of recipient characteristics on support for medical (VMA) and financial aid (VFA) in April 2020 (Panels I + II) and May 2021 (Panels III + IV).

Notes: Each plot shows the average marginal component effects of vignette attributes on medial and financial solidarity. VMA1 and VFA1: n = 4,775; VMA2 and VFA2: n = 4,016.

Figure 2 depicts the treatment effects of all experimental factors from both survey waves. We varied the control dimension pertaining to the capacity of the health and fiscal systems. In the first medical (VMA1) and financial aid (VFA1) vignettes, countries that find themselves in need, despite previously having set up a well-funded health system or having enforced fiscal discipline, are apparently considered victims of ‘bad luck’. This is captured by the variables ‘public health system’ and ‘fiscal discipline’: both having a well-developed health system and being ascribed past fiscal discipline increase public support in a statistically significant way. In the second experiments (VMA2 and VFA2), we referred more directly to the political and administrative measures enacted over the course of the pandemic in preparation for future infection waves (‘COVID-19 policy’). In line with the theoretical expectations, we find that citizens are more generous when it comes to a well-prepared but unfortunate country, as compared to a country that only belatedly introduced suitable policies. Yet, effect sizes remain moderate across all four vignettes. These findings are in line with H2a. While ‘good or bad’ COVID-19 policies are a retrospective dimension of control, we also test for a prospective understanding thereof. In VMA2 and VFA2, we inquired whether administrative capacity or effectiveness affected support for aid. We find that this forward-looking dimension is, indeed, important: citizens are more supportive of financial and medical aid if a country is perceived to be governed effectively (H2b). The effect of capacity is smaller for the medical aid condition. Effectiveness is less about a resentful punishment of past failures than an assessment of the capacity to properly administer large transfers. Evidently, citizens want their aid to be used well.

To test the role of political proximity/political community membership, we varied the regions of potential recipients in VMA1 and VFA1. We distinguished assistance that is directed towards: (1) another region in Germany; (2) an EU member state; and (3) a state that is not a member of the EU. Willingness to provide different types of help clearly varies with the regional scope, confirming H3. Support for medical and financial help to other German regions is significantly higher than help for another EU country. Using a linear probability model on dichotomized dependent variables, willingness to help another German region is between 8 per cent (medical) and 12 per cent (financial) higher than helping another EU member state (see Online Appendix E). In contrast, support for non-EU countries is lower than for EU member states when it comes to medical help. In the case of financial help, there is no statistically significant difference between EU und non-EU countries – a finding that contrasts with previous results in the literature (Gerhards et al. Reference Gerhards2019).

In VMA2 and VFA2, we account for two further relational characteristics of the recipients, namely, the adherence to community norms and reciprocity. Figure 2 highlights the importance of these factors. In the context of EU aid, we operationalize ‘norm adherence’ through the proper working of the rule of law in a member state, reflecting current concerns about democratic backsliding (Kelemen Reference Kelemen2020). Confirming H4, we find that whether a recipient country respects the rule of law is crucial for explaining citizens' support for solidarity. In line with H5, we also find that an EU member state that had been ready to accept refugees in the past is considered far more deserving of medical and financial aid. The reciprocity and the rule of law/democracy treatment display the largest substantive effects – a finding that we had not anticipated. The effect sizes are relatively large, increasing support by around 0.35 to 0.5 scale points on a scale from 1 to 7 for both community norms and reciprocity (9 per cent medical aid and 12–13 per cent financial aid for the dichotomized dependent variables).

Beyond recipient characteristics, donors are also influenced by the risks and costs associated with an aid package. These variables are included in VMA1 and VFA1, and have a strong negative effect, highlighting the well-known importance of self-interest. For VMA1 and VFA1, we also observe an ordering effect. Respondents that receive the medical before the financial vignette report higher support for either type of aid, suggesting carry-over effects. If the existential medical need is shown first, it seems to trigger a higher deservingness, which also carries over to financial need independent of other treatments (see Online Appendix E).

Turning to the effect sizes of the ‘redistribution from’ dimension of European solidarity (see Model 2 in Tables A3–A6 in Online Appendix E), we find that altruism and European identity are strongly correlated with our outcomes in all four experiments. Cosmopolitanism has a weaker correlation to the dependent variables. For medical aid (VMA2), the effects of altruism (0.64 scale points) and European identity (0.62 scale points) are almost twice as big as the effects of rule of law (0.36 scale points), refugee admission (0.39 scale points) or administrative capacity (0.29 scale points). For financial aid (VFA 2), the effects of altruism (0.53 scale points) and European identity (0.77 scale points) are slightly stronger and stronger, respectively, than the effects of rule of law (0.46 scale points), refugee admission (0.47 scale points) or administrative capacity (0.45 scale points).

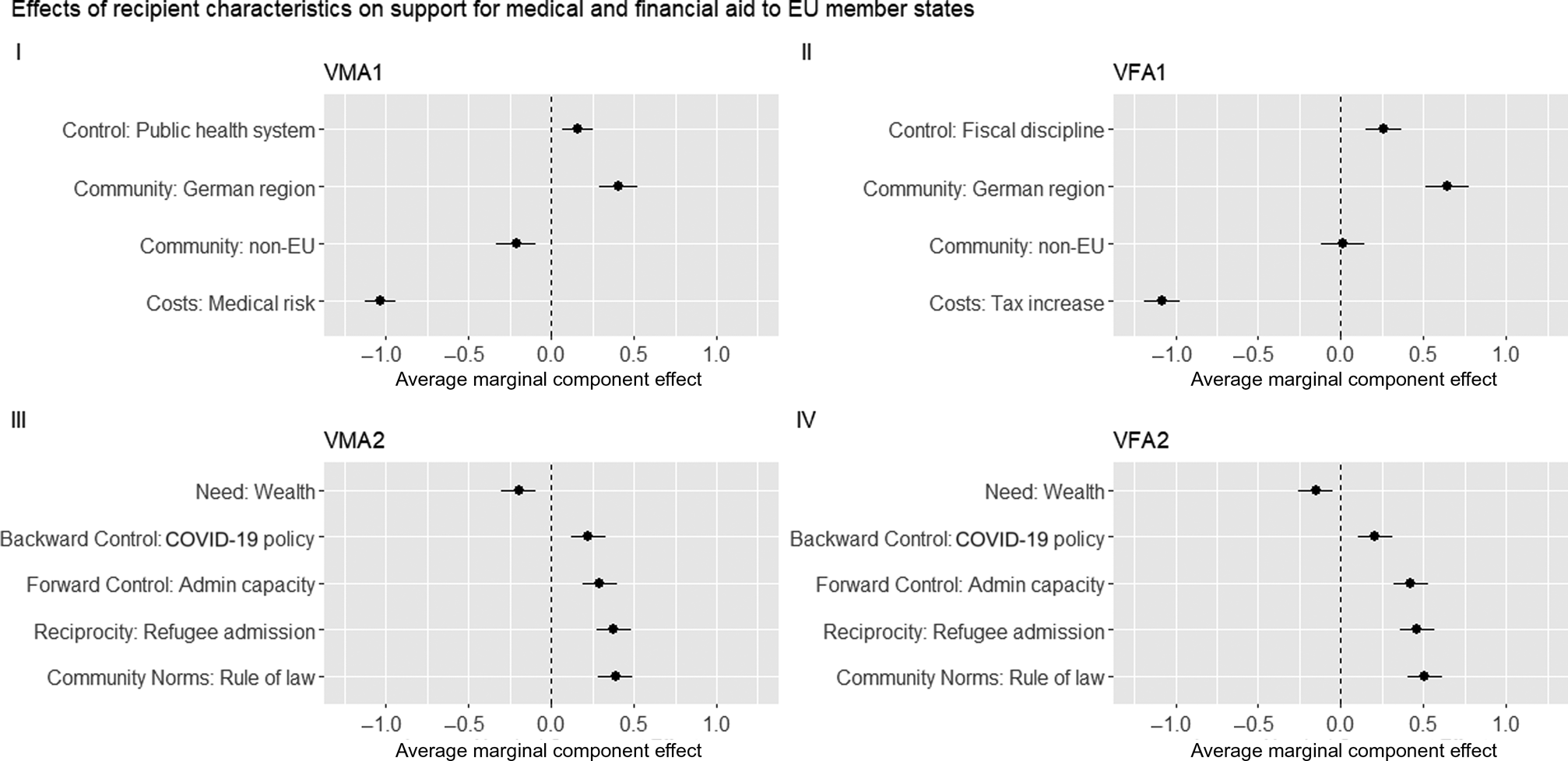

To assess how these recipient characteristics interact with these individual dispositions of donors, we conducted subgroup analyses in which we compare citizens with high and low altruism, cosmopolitanism and European identity scores.Footnote 5 Figures 3–5 illustrate the heterogeneous treatment effects of VMA2 und VFA2 for respondents with high and low altruism and cosmopolitanism scores, as well as those with a European or exclusively national identity.Footnote 6

Fig. 3. Heterogeneous treatment effects of recipient characteristics for respondents with high and low altruism scores.

Fig. 4. Heterogeneous treatment effects of recipient characteristics for respondents with a European or an exclusively national identity.

Fig. 5. Heterogeneous treatment effects of recipient characteristics for respondents with high and low cosmopolitanism scores.

Figure 3 shows the support for medical (Panel I) and financial aid (Panel II) for respondents with high (black) and low (grey) levels of altruism. Our analysis highlights for both types of aid that people with higher levels of altruism are more sensitive to the situational and relational country cues. In the group with low altruism, our treatments are only partly statistically significant and mostly have a weaker effect on medical and financial solidarity. This finding lends some support to H6a, which expected situational and relational cues to be specifically important for citizens with a more altruistic outlook.Footnote 7

Turning to the moderating effect of European identity, depicted in Figure 4, we find that respondents with an exclusive national identity are less supportive of international solidarity than those who have a European identity. Both groups value an efficient public administration, reciprocity and the adherence to community norms when assessing possible recipient countries. However, refugee admission has a discernibly stronger effect for people with a European identity.Footnote 8 When it comes to the distinction between respondents with high and low cosmopolitanism scores (see Figure 5), we find no clear differences between the effects of the treatment variables on these groups, with the exception being the reciprocity treatment in the medical vignette. However, while our findings are mixed, the effects of ‘redistribution to’ variables are stronger, not weaker, for people with a stronger European identity or for more altruistic people. Thus, we do not find support for H6b.

Additional analysis for VMA1 and VFA1 (see Online Appendix I) shows that EU identity matters with respect to the political community membership treatment. While both respondents with an exclusive and a European identity prefer to help other German regions rather than foreign countries, those with an exclusively national identity are even less willing to do so. Moreover, this group seems to make no distinction between EU and non-EU recipient countries. In contrast, respondents with a European identity are more supportive of medical aid to EU countries compared to non-EU recipients but appear not to make this distinction when it comes to bilateral financial aid.

In sum, we find support for H6a: the analysis of altruism shows that having pro-social orientations seems to increase the effect of situational and relational recipient-country characteristics on European solidarity. For cosmopolitans and citizens with a European identity, reciprocity in the form of refugee admission appears to matter more than for non-cosmopolitans and those with a nationalist identity. This latter group also seems to make less of a distinction between EU and non-EU members – that is, membership in a political community – when deciding on solidarity beyond the nation state. Our findings therefore show that the ‘redistribution from’ and the ‘redistribution to’ dimensions interact, suggesting that their joint effect needs to be taken into account in the analysis of international solidarity.

Robustness Checks

We conducted a number of robustness checks, which support our results. First, the experimental treatments produce consistent results for the overall sample, as well as for different theoretically relevant subgroups, relating, for instance, to differences in terms of altruism, cosmopolitanism and European identity. Secondly, all analyses have also been conducted without using the population weights, as well as with and without listwise deletion, providing further support for our analysis. Thirdly, when accounting for multiple testing, using a Bonferroni correction, we receive robust results (see Table A7 in Online Appendix E).

On a more specific note, one could argue that our measure of reciprocity (that is, states’ past willingness to contribute to refugee-relocation schemes) reflects general attitudes towards migration, rather than reciprocity and burden sharing. To address this concern, we also ran VFA2 in an additional survey wave (see Online Appendix L) to control for general attitudes towards immigration (a measure not available in the second survey). The analysis shows that while European solidarity is generally larger among respondents with pro-migration orientations, the effect of our reciprocity measure remains statistically significant for the subgroup with more critical orientations towards migrants (see Figure A10 in Online Appendix L). Moreover, in an additional experiment on medical solidarity, we use a direct measure of recipients' principled readiness to reciprocate medical help (see Figure A9 in Online Appendix L). This direct measure has a strong and statistically significant effect on medical solidarity and therefore provides further support to the general importance of reciprocity.

Arguably, a number of measures relating to the ‘redistribution from’ dimension suffer from social desirability, for instance, people may consider themselves to be altruists to uphold a positive self-image. In our study, these measures are used to analyse the interactions of ‘redistribution to’ with ‘redistribution from’. While we cannot rule out effects of social desirability, we also get consistent results when using different cut-off points for our altruism item on our seven-point Likert scale (see Online Appendix M). In sum, we are confident that our measures adequately capture the underlying theoretical concepts and that our results are robust.

Discussion

Getting a more encompassing understanding of support for international or European solidarity is important for theoretical and substantive reasons. So far, our knowledge of solidarity beyond the nation state remains largely limited to respondent-specific traits, that is, the ‘redistribution from’ side. However, in light of growing international interdependence and major global crises, the importance of international solidarity is likely to increase. It is therefore crucial to better understand the conditions under which citizens are willing to grant aid to other countries and their citizens. Public opinion can constrain the political agenda (De Vries, Hobolt and Walter Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021; Page and Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro1992), and if scarce medical resources or colossal sums of money are transferred to other states, as is the case with the ‘Next Generation EU’ recovery plan, legitimacy hinges on citizens' support (Armingeon Reference Armingeon2021). Obviously, public support is important from a legitimacy perspective too, as democratic governments should value responsiveness (Schneider Reference Schneider2018; Wratil Reference Wratil2019).

By taking the double threat of the COVID-19 pandemic as a health and an economic crisis seriously, our analysis goes beyond the existing research focus on financial redistribution, adding medical aid. Moreover, we extend existing studies of EU financial solidarity that focus on the ‘redistribution from’ perspective by adding the ‘redistribution to’ component.

Our theoretical focus on the ‘redistribution to’ dimension allows a first test of the importance of situational and relational recipient characteristics for international redistribution. Our experiments underline that in addition to the well-studied material, pro-social and cosmopolitan motives, the specific situation of need, and relational political characteristics play a strong role in explaining support for international assistance. In line with the extant literature (Bechtel and Mannino Reference Bechtel and Mannino2020; Jensen and Petersen Reference Jensen and Petersen2017), we find that medical help is less conditional than financial help. We demonstrate that control has both a backward- and a forward-looking dimension: citizens want their aid to be used well and know that administrative capacity is important in this respect. Moreover, our experiments show that formal political community membership does not easily extend beyond the nation state; in particular, the difference between solidarity towards EU member states and non-member states was smaller than anticipated. At the same time, our data reveal that shared norms and reciprocity matter strongly for EU transfers. The respondents are more willing to financially help those states that show respect for the fundamental norms of the EU, highlighting the relational conditions of solidarity. In addition, the ‘redistribution from’ and ‘redistribution to’ dimensions need to be jointly considered to fully understand European solidarity; in particular, situational and relational considerations are especially important when coinciding with higher levels of altruism or a European identity. Therefore, this study also has implications for research that exclusively focuses on respondent characteristics, such as altruism. While altruists are generally more likely to help than non-altruists, it is specific situational emergencies, as well as the characteristics of a set of actors in such emergencies, that really propel altruism as a driver of support. Situational and relational aspects are thus crucial catalysts for translating individual orientations into action. In existing research on transnational solidarity, these mechanisms mostly remain implicit. Thus, whether studies do or do not find a strong effect of altruism on social support might well be a consequence of moderating situational and relational factors, rather than of altruism itself.

Our study is based on data from Germany. As the EU's largest economy and net contributor, Germany is substantively important when it comes to EU funds. Moreover, having one of the largest systems of intensive-care units in Europe, it also has a higher capacity for medical support than other countries. German Chancellor Merkel was a vocal supporter of the ‘Next Generation EU’ recovery programme. Given the German public's past reluctance to increase financial transfers to other EU member states, it is notable that she faced no significant public constraint. Indeed, our data show that in November 2020, almost 50 per cent of respondents expressed support for this policy (see Online Appendix J).Footnote 9 In contrast, the governments of other net-contributing states, in particular, the so-called ‘frugal four’ (Austria, Finland, the Netherlands and Sweden), expressed strong concerns about the support measures – an observation which suggests that diverging perceptions of situational and relational characteristics may inform redistributive choices, and future research should investigate how the domestic framing of such situations affects citizens' readiness to support European and international aid. Fault attribution may play a large role in justifying aid policies, oftentimes accentuating divergent perceptions of different actors, both on the donor and on the recipient sides. Despite the different positions taken by the German government and the governments of the ‘frugal four’ with respect to ‘Next Generation EU’, we still maintain that the mechanisms revealed by our experimental results should similarly hold in other European countries, or at least those that perceive themselves to be on the net-contributing side. For instance, Genschel and Hemerijck (Reference Genschel and Hemerijck2018) report YouGov data that highlight a stark divide between one group of self-perceived net contributors and another group of self-perceived net recipients; Bremer et al. (Reference Bremer2021) likewise hypothesize similarities between Germany and the Netherlands. However, citizens are, on average, more ready to support European solidarity when countries suffer from a natural disaster or a military attack, rather than from unemployment or public debt (Genschel and Hemerijck Reference Genschel and Hemerijck2018). This may make the COVID-19 crisis a likely case for strong support for redistributive measures across different countries. At the same time, while less-severe situational characteristics may diminish absolute support levels, we have no reason to expect changes with respect to the relational components of our model.

In our April/May 2020 experiments, we compared support for help for EU member states with that for other countries. Our findings indicate that the mechanisms also extend to solidarity with states outside the EU. However, future research should more systematically investigate additional cases, varying the donor and the recipient sides, as well as different situations of need. It may well be that the global shock imposed by COVID-19 has triggered unique reactions that are different to other natural or man-made disasters that usually do not affect donors and recipients alike.

Our findings have important policy implications. Countering pessimistic expectations about the difficulties of formulating multilateral reactions to the COVID-19 crisis, the EU has adopted ambitious measures to fight the health crisis and mitigate its most devastating economic and social consequences. Apparently, public opinion was no hindrance in this respect, but there is still a need for better understanding the mechanisms of international solidarity – the global vaccination race during COVID-19 or the 2022 war in the Ukraine come to mind. Our results suggest that if potential recipients are not perceived to be legitimately deserving, this reduces support for international aid. As the legitimacy of multilateral actions, especially during times of high politicization, hinges on responsiveness, political leaders in favour of international solidarity must solicit public support. Since in-group dynamics usually increase the reluctance to help outsiders, justifying international solidarity is far from trivial and requires engaged leadership. On the one hand, our findings therefore highlight the importance of preventing the prevalence of negative national stereotyping and prejudiced fault attribution. On the other hand, our results also have implications for the recipients of aid. In particular, honouring community norms and reciprocity can pay off in times of crisis.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123422000357

Data Availability Statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RCO69B

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for excellent comments provided by three anonymous reviewers and Lucas Leemann. Moreover, we thank Jozef Bátora, Michael Bechtel, Ariane Bertogg, Christian Breunig, Marius Busemeyer, Urs Fischbacher, John Erik Fossum, Anselm Hager, Pascal Horni, Philipp Kerler, Vally Kouby, Theresa Kuhn, Giorgio Malet, Martin Moland, Patrick Sachweh, Katrin Schmelz, Julian Schüssler, Jonathan Slapin, Helene Sjursen, Gabriele Spilker, Jarle Trondal, Catherine de Vries, Stefanie Walter and the participants at seminars at Comenius University, ETH Zurich, ARENA Centre for European Studies, the Council for European Studies (CES) and ECPR Standing Group on the European Union (SGEU) conferences in 2021, and an Integrating Diversity in the European Union (InDivEU) workshop at the University of Amsterdam for helpful comments. Thomas Woehler, Konstantin Mozer, Philipp Kling, Franziska Lauth and Pascal Mounchid provided excellent research assistance.

Financial Support

The surveys were funded by the Cluster of Excellence for ‘The Politics of Inequality’ (German Research Foundation [DFG], Grant Number EXC-2035/1–390681379). Dirk Leuffen's and Max Heermann's work was generously supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement 822419.

Competing Interests

None.