Deliberative democracy is fundamentally concerned with stakeholder engagement, deliberation, and the ethical issue of exclusion of disempowered stakeholders in the articulation of discourses about corporate social and environmental responsibilities (hereafter, discourses of responsibilities) (Donaldson & Preston, Reference Donaldson and Preston1995; Phillips, Reference Phillips2003). Dissensus approaches to stakeholder engagement (e.g., Barthold & Bloom, Reference Barthold and Bloom2020; Brand, Blok, & Verweij, Reference Brand, Blok and Verweij2020; Burchell & Cook Reference Burchell and Cook2013a; Couch & Bernacchio, Reference Couch and Bernacchio2020; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015, Reference Dawkins2019; Fougère & Solitander, Reference Fougère and Solitander2020; Rhodes, Munro, Thanem, & Pullen, Reference Rhodes, Munro, Thanem and Pullen2020; Sorsa & Fougère, Reference Sorsa and Fougère2020; Whelan, Reference Whelan2013; Winker, Etter, & Castelló, Reference Winker, Etter and Castelló2020) claim that agonism, rather than the rational consensus advocated by previous literature (e.g., Baur & Palazzo, Reference Baur and Palazzo2011; Burchell & Cook Reference Burchell and Cook2013b; Palazzo & Scherer, Reference Palazzo and Scherer2006; Roloff, Reference Roloff2008; Scherer & Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007), should be the aim of the engagements. Dissensus approaches argue that rational consensus is merely the temporary result of a provisional hegemony; it is a stabilization of power that always entails some form of exclusion (Brand et al., Reference Brand, Blok and Verweij2020; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015; Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005) because every possible discourse is hegemonic in nature and implies an ineradicable violence (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005). Agonism aims instead at building relations between stakeholders in such a way that the other stakeholders are recognized as legitimate adversaries (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005). In agonistic relations, conflict is accepted and agency is given to disempowered actors, who, through constructive engagements, can attempt to change hegemonic discourses.

Mechanisms such as compromise and arbitration (Brand et al., Reference Brand, Blok and Verweij2020; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015) have been proposed as means to reach agonistic closure in stakeholder engagement because they give agency to the disempowered actor and explain the power dynamics whereby each stakeholder might maintain its original views and ideals. However, these negotiation mechanisms are not “a complete embodiment of agonist ideals” (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015: 13) because they fall short of accepting dissensus and antagonism as the fundamental nature of the relation between the stakeholders and also cannot explain the dynamics of conflict beyond a temporary closure.

We draw on the agonism theories of Mouffe (Reference Mouffe1999, Reference Mouffe2005) and Connolly (Reference Connolly1993) to argue that conflict dynamics have to be understood through the analysis of the “ethics of disharmony.” Ethics of disharmony is concerned not only with the different moral categories that characterize opponent stakeholders, that is, their different views and ideals, but also with the inherent constitution of conflict between the opponents in an us-versus-them discrimination that leads to the creation of identities (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005). Identities are constituted through collective “passion” (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005: 103). Passion is a certain type of collective affect that constitutes identification. Affects are “desires [that] are not reducible to the pursuit of rational interests” (Voronov & Vince, Reference Voronov and Vince2012: 59). Affects are malleable and can be agentically oriented to contribute to the dissemination of counter-hegemonic discourses (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2014). The way in which this agentic reorientation is achieved is, however, yet to be explored in agonistic studies.

Improving our understanding of how passion can be strategically oriented in dissensus is even more important at the turn of the twenty-first century, when social media engagements are fundamentally shaping the discourses of responsibility (Castelló, Etter, & Nielsen, Reference Castelló, Etter and Nielsen2016; Margetts, John, Hale, & Yasseri, Reference Margetts, John, Hale and Yasseri2015; Whelan, Moon, & Grant, Reference Whelan, Moon and Grant2013). Engagements in social media, and in particular, on Twitter, considered a key platform for political and social debates (Grčar, Cherepnalkoski, Mozetič, & Novak, Reference Grčar, Cherepnalkoski, Mozetič and Novak2017; Howard, Reference Howard2020; Marichal & Neve, Reference Marichal and Neve2020), have been described as irrational (Rogstad, Reference Rogstad2016; Wollebæk, Karlsen, Steen-Johnsen, & Enjolras, Reference Wollebæk, Karlsen, Steen-Johnsen and Enjolras2019) with affects polarizing discussions (Berger & Milkman, Reference Berger and Milkman2012; Kramer, Guillory, & Hancock, Reference Kramer, Guillory and Hancock2014; Quercia, Ellis, Capra, & Crowcroft, Reference Quercia, Ellis, Capra and Crowcroft2011) and, as a result, annihilating the possibility of rational consensus or even any form of deliberation (Kramer, Guillory, & Hancock, Reference Kramer, Guillory and Hancock2014; Wollebæk et al., Reference Wollebæk, Karlsen, Steen-Johnsen and Enjolras2019). In contrast, the dissensus perspective on social media engagements (Anderson, Reference Anderson2011; Marichal & Neve, Reference Marichal and Neve2020; McCosker, Reference McCosker2014; Rahimi, Reference Rahimi2011) suggests that constructive engagements and deliberation are possible. Dissensus approaches to social media have explored the configuration of passion online as general affective expressions (Marichal & Neve, Reference Marichal and Neve2020; McCosker, Reference McCosker2014). However, there is little knowledge on the strategic manipulation to change hegemonic discourses. Our research question therefore asks, How can stakeholders mobilize affects to change hegemonic discourses?

To address this issue, we present an inductive-deductive, longitudinal study of the strategic efforts of civil society actors to convince corporations and other peer activists that they should reduce plastic production and consumption rather than recycling plastic. Through a qualitative and quantitative analysis of Twitter messages, supported and triangulated with semistructured interviews, naturalistic observations, and archival data, we reveal that civil society actors employ a mobilization strategy when interacting with their peers and an inclusive-dissensus strategy when trying to convert corporations to their counter-hegemonic discourse. Surprisingly, civil society organizations did not resort to strategies like compromise and arbitration, which would have required them to negotiate with corporations on the moral position, as typically proposed by the literature. On the contrary, civil society actors maintained their moral positions but, to avoid disengagement and polarization, used inclusive-dissensus strategies that combined moral affects with solidarity affects to keep their moral positions and make corporations feel included in the community of anti–plastic pollution fighters. We also show that affects contribute to the interactivity of the relation-making engagements constructive, rather than destructive, as argued by the literature.

We contribute to the literature in three ways. First, we add to the studies of deliberative democracy and dissensus in stakeholder engagement by pointing at the strategic use of affects in the dynamics of change of hegemonic discourses. Second, we show how passion can be mobilized through inclusive-dissensus strategies, thus contributing to agonistic pluralism theories and to collective action studies on affects. Third, we contribute to the understanding of social media as public agorae for stakeholder engagement and deliberation.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Dissensus in Stakeholder Engagement

One of the major philosophical projects that has confronted modernity is concerned with understanding how to control affects in the construction of public discourse. In the seventeenth century, philosophers, such as Descartes and Thomas Hobbes, advocated for rationality in debates to avoid exaggeration and distortion in arguments. The exaltation of reason and the development of scientific knowledge were both aimed at finding consensus and, ultimately, peace. In the twentieth century, with the emergence of globalization and the increase of corporate power (Beck, Reference Beck1992; Scherer & Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2011), the central role of rational argument and consensus orientation was extended to the processes of deliberative democracy and, more concretely, stakeholder engagement (Scherer & Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007). Based on liberal-democratic ideals, stakeholder engagement was mostly conceived as the means of achieving rational consensus amongst different stakeholders (Baur & Palazzo, Reference Baur and Palazzo2011; Burchell & Cook, Reference Burchell and Cook2013b; Palazzo & Scherer, Reference Palazzo and Scherer2006; Roloff, Reference Roloff2008; Scherer & Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007), which would shape the discourses of responsibilities. These authors claimed that stakeholder engagement should be based in liberal forms of deliberation that should follow the conditions of ideal speech (Habermas, Reference Habermas1984), with all parties acting as free and equal citizens and engaging with mutual respect in communicative action (Habermas, Reference Habermas and Habermas1998b). The closure of debates draws its validity from the communicative presuppositions that fair processes allow fair arguments to emerge during deliberation (Habermas, Reference Habermas1998a).

Dissensus approaches to stakeholder engagement and deliberation (e.g., Barthold & Bloom, Reference Barthold and Bloom2020; Brand et al., Reference Brand, Blok and Verweij2020; Burchell & Cook, Reference Burchell and Cook2013a; Couch & Bernacchio, Reference Couch and Bernacchio2020; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015, Reference Dawkins2019; Fougère & Solitander, Reference Fougère and Solitander2020; Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Munro, Thanem and Pullen2020; Sorsa & Fougère, Reference Sorsa and Fougère2020; Whelan, Reference Whelan2013; Winker et al., Reference Winker, Etter and Castelló2020) have emerged as a critique to the rational consensus of liberal-democracy approaches. Dissensus scholars argue that every possible discourse is fundamentally hegemonic by nature, and this implies an ineradicable violence and power because “antagonism is inherent in human relations” (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005: 101). Hegemonic discourses describe “the [discursive] practices of articulation through which a given order is created and the meaning of social institutions is fixed” (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2013: 2). As a critique to the liberal-democratic perspectives, dissensus approaches argue that rational consensus can exist only as the temporary result of a provisional hegemonic discourse, being a stabilization of power that always entails some form of exclusion (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe1999).

Building on the agonistic pluralism theories of Mouffe (Reference Mouffe1999, Reference Mouffe2005), business ethics scholars on deliberative democracy (e.g., Burchell & Cook, Reference Burchell and Cook2013a; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015, Reference Dawkins2019) propose that “the objective of stakeholder engagement should not be benevolence toward stakeholders, but agonistic processes and structures to contest corporate prerogative such that [disempowered] stakeholders are able to protect their own interests” (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015: 3). That is, we need to understand how to turn antagonistic relations into agonistic relations instead of striving for a fair but futile deliberation (Brand et al., Reference Brand, Blok and Verweij2020; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015; Fougère & Solitander, Reference Fougère and Solitander2020; Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005). Agonistic relations aim at domesticating conflict, building relations in such a way that the other stakeholders are no longer perceived as “the enemy to be destroyed but as an adversary, that is, somebody whose ideas we combat but whose right to defend those ideas we do not put into question, since they are legitimate opponents” (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005: 102).

Dissensus perspectives on stakeholder engagement and deliberation have focussed on the strategies to domesticate conflict (Brand et al., Reference Brand, Blok and Verweij2020; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015; Fougère & Solitander, Reference Fougère and Solitander2020; Levy, Reinecke, & Manning, Reference Levy, Reinecke and Manning2016). Thus Brand et al. (Reference Brand, Blok and Verweij2020: 20) present compromise as “an agreement in which all sides sacrifice something of value… to improve on the status quo.” Dawkins (Reference Dawkins2015) proposes arbitration, in which a neutral actor administers the hearing and ultimately renders a decision. Compromise and arbitration are therefore negotiation strategies that allow disempowered stakeholders to reach concrete agreements on particular goals or actions. They explain the power processes in which each stakeholder maintains its original views and ideals yet is able to reach closure.

Compromise and arbitration strategies, however, fall short of explaining the ongoing dynamics of the accommodation of hegemonic discourses, that is, how disempowered stakeholders get to change hegemonic discourses in a manner that goes beyond the simple processes of one-off or temporary negotiation. Furthermore, a fundamental aspect of agonistic pluralism, dismissed by previous dissensus approaches, is the “ethics of disharmony” (which is present in the agonistic pluralism theories of Mouffe, inspired by Žižek [Reference Žižek1992]). The ethics of disharmony makes two claims: first, that the invocation of different moral categories (or “ideas of good”) is what characterizes opponent stakeholders, and second, that deliberative processes “always involve decisions that require making a choice between conflicting alternatives” (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2013: 3). Therefore the ethics of disharmony is concerned not only with moral decision per se but also with the nature of the ethical subjectivity and the processes of identity formation around them (Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Munro, Thanem and Pullen2020).

Thus, from the ethics of disharmony perspective, stakeholder engagement dynamics are intrinsically concerned with business ethics for two main reasons: first, because attending to dissensus “bears an obligation to respond to and intervene in the erased conflicts in which victims cannot signify their damages” (Ziarek, Reference Ziarek2001: 92), and second, because engagements and deliberation should be analysed in a context of conflict and diversity of subjectivities in a non-rationalistic way. To this last point, Mouffe (Reference Mouffe2005) argues that conflict closure is concerned with the creation of an “us” by the determination of a “them.” That is, identities are created that confirm the establishment of us-versus-them discrimination, promoting the eventual transition from enemy to adversary. Closure should be viewed as being more akin to conversion than as a process of rational persuasion. “Compromises are, of course, possible … but they should be seen as temporary respites in an ongoing confrontation” (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005: 102). The process of conversion requires that the participants have come to understand the identities of the others and “to engage with its difference, however this engagement happens in violence and exclusion” (134) and through the expression of collective “passion” (103).

Passion as Constitutive of Dissensus

Passion is defined as “a certain type of common affects, those that are mobilized … in the formation of the we/they forms of identification” (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2014: 155). Passion helps to underline the relation between the collective and partisan characters of stakeholder engagement and form the basis of struggles against other groups (Connolly, Reference Connolly1993).

Affects are malleable and susceptible of being agentically oriented in different directions; the task of disempowered stakeholders is to foster affective attachments that contribute to the dissemination of counter-hegemonic discourses (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2014). However, agonistic pluralism studies say little about how affects are nurtured and promoted beyond claiming that a moral affect can be displaced by a contrary affect that is stronger than the original (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005). In focusing on moral affects, Mouffe dismisses the creation of collective identities. Further research needs to explore how passion can be agentically oriented to promote counter-hegemonic discourses and eventually lead to an adversary’s conversion.

Collective action scholars have analysed how affects can be agentically managed to shape collective identities by the leadership of social movements (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Reinecke and Manning2016; Snow, Reference Snow, Smelser and Baltes2001) or social entrepreneurs (Barberá-Tomás, Castelló, De Bakker, & Zietsma, Reference Barberá-Tomás, Castelló, De Bakker and Zietsma2019). They use the word emotions to describe what Mouffe calls “affects.” We retain Mouffe’s terminology for consistency and use affects as synonymous of emotions and affective as emotional. For collective action scholars, affects are “desires [that] are not reducible to the pursuit of rational interests” (Voronov & Vince, Reference Voronov and Vince2012: 59). They are also indicators of what is salient to people (Goodwin, Jasper, & Polletta, Reference Goodwin, Jasper, Polletta, Goodwin, Jasper and Polletta2001; Jasper, Reference Jasper2011; Voronov & Vince, Reference Voronov and Vince2012) and can be used as mechanisms of power (Creed, Hudson, Okhuysen, & Smith-Crowe, Reference Creed, Hudson, Okhuysen and Smith-Crowe2014). As such, affects can be agentically shaped to reflect negative or positive self-evaluations and can also influence the evaluations of others (Creed et al., Reference Creed, Hudson, Okhuysen and Smith-Crowe2014). The resulting internalized unconscious representation of what is good/bad helps to impose or generate self-imposed limitations on behaviour (Voronov & Vince, Reference Voronov and Vince2012), while also signalling identification with the norms, practices, and beliefs of the surrounding environment (Wright, Zammuto, & Liesch, Reference Wright, Zammuto and Liesch2017).

Hence there are two types of affects in collective action: first, the affects that create the sense of what is good or bad (moral affects), and second, the affects that nurture a sense of identification (solidarity affects). Moral affects involve “feelings of approval or disapproval based on moral intuitions and cultural principles as well as the satisfaction we feel when we do and feel the right (or wrong) thing” (Jasper, Reference Jasper2011: 287). People violating socially accepted rituals have been observed to suffer from moral affects like anxiety and embarrassment (Collins, Reference Collins and Kemper1990), guilt, and shame (Stets & Carter, Reference Stets and Carter2012), whereas anger and disgust are responses to the other’s violation of the social order (Rozin, Lowery, Imada, & Haidt, Reference Rozin, Lowery, Imada and Haidt1999). Moral affects have also been described as being strategically elicited by leaders or entrepreneurs by, for example, promoting moral shock (Barberá-Tomás et al., Reference Barberá-Tomás, Castelló, De Bakker and Zietsma2019; Jasper & Poulsen, Reference Jasper and Poulsen1995). Moral shock is “the vertiginous feeling that results when an event or information shows that the world is not what one had expected, which can sometimes lead to articulation or rethinking of moral principles” (Jasper, Reference Jasper2011: 287). Moral affects–based strategies may have paradoxical effects (Reger, Reference Reger2004). For example, studies of discourses of climate change showed how the strategic use of moral affects caused denial, apathy, and avoidance for people to cope with the unpleasant feelings evoked (O’Neill & Nicholson-Cole, Reference O’Neill and Nicholson-Cole2009). This is particularly likely to be the case when the moral cause induces guilt that requires potential stakeholders to face the error of their ways (Barberá-Tomás et al., Reference Barberá-Tomás, Castelló, De Bakker and Zietsma2019).

Solidarity affects make “individuals feel a desire to defend and honor the group” (Collins, Reference Collins and Kemper1990: 33). They are feelings of status provoked by group membership and express the social density of the interaction (Collins, Reference Collins and Kemper1990). Strategic uses of solidarity affects create a sense of shared membership based on common achievements (Taylor, Kimport, Van Dyke, & Andersen, Reference Taylor, Kimport, Van Dyke and Andersen2009) and a sense of affinity and positive affects about the group (Jasper, Reference Jasper2011). Solidarity affects provide the idea of social affection or “affective loyalties.” These are affects, such as love, liking, respect, or trust, relating to attachment or aversion to others in the definition or redefinition of oneself towards said others (Jasper, Reference Jasper2011). Solidarity affects also incorporate an emotional bonding kindled by a shared purpose. When used strategically, such bonding can act as a reminder of the common objectives related to collective action (Jasper, Reference Jasper2011).

On one hand, despite the deep understanding of affects by collective action studies, they fail to explain stakeholder engagement processes. This is because studies of collective action stress the importance of affects in building moral resonance between the leader and the targets (Giorgi, Reference Giorgi2017; Schrock, Holden, & Reid, Reference Schrock, Holden and Reid2004; Snow & Benford, Reference Snow and Benford1988); that is, leaders and targets have a degree of agreement about fundamental moral principles. However, moral resonance is rare in stakeholder engagements amongst corporations and civil society (Arenas, Albareda, & Goodman, Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020). Thus collective action theories do not explain how affects can be elicited if ineradicable conflict is assumed to be inherent. On the other hand, despite studies on dissensus on stakeholder engagement having pointed at the importance of conflict as ineradicable, they have dismissed the dynamics of conflict, constituted by affects. Our research addresses this gap by looking at how stakeholders can mobilize affects to change hegemonic discourses of responsibilities when conflict is ineradicable.

METHODOLOGY

Context: From Recycling to Refuse Single-Use Plastic

Plastic pollution is one of the most important grand challenges of the twenty-first century (DG Environment, 2011). Since the mid-1990s, when Captain Charles Moore discovered a vast area of floating plastic debris in the Pacific (which he termed the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch”), marine scientists and environmental activists began to actively denounce plastic pollution in the United States and United Kingdom. By 2008, Algalita, founded by Captain Moore, and other organizations, such as 5 Gyres, Heal the Bay, Plastic Pollution Coalition (PPC), and Greenpeace (see Table 1 for more examples of actors), followed, forming an emergent institutional infrastructure (Waddock, Reference Waddock2008) of civil society advocating for a change in the public understanding of plastic pollution (Moore, Reference Moore2012). These organizations claimed that the issue of plastic pollution had been faked by corporations. They argued that the most cogent solution to the issue of plastic pollution was to refuse single-use plastics (rather than to recycle them, which was the main thrust of corporations). As one of our informants noted, “recycling is the big Trojan horse—it is the main lie—the biggest mistake,” because “a plastic bag takes thousands of years to biodegrade in nature” (Colin, 2010). In the 2000s, the idea that one might refuse or reduce single-use plastic to “live a plastic free life” was perceived as radical and contentious (Terry, Reference Terry2012), not only by corporate actors but also by most citizens in the United States and United Kingdom.

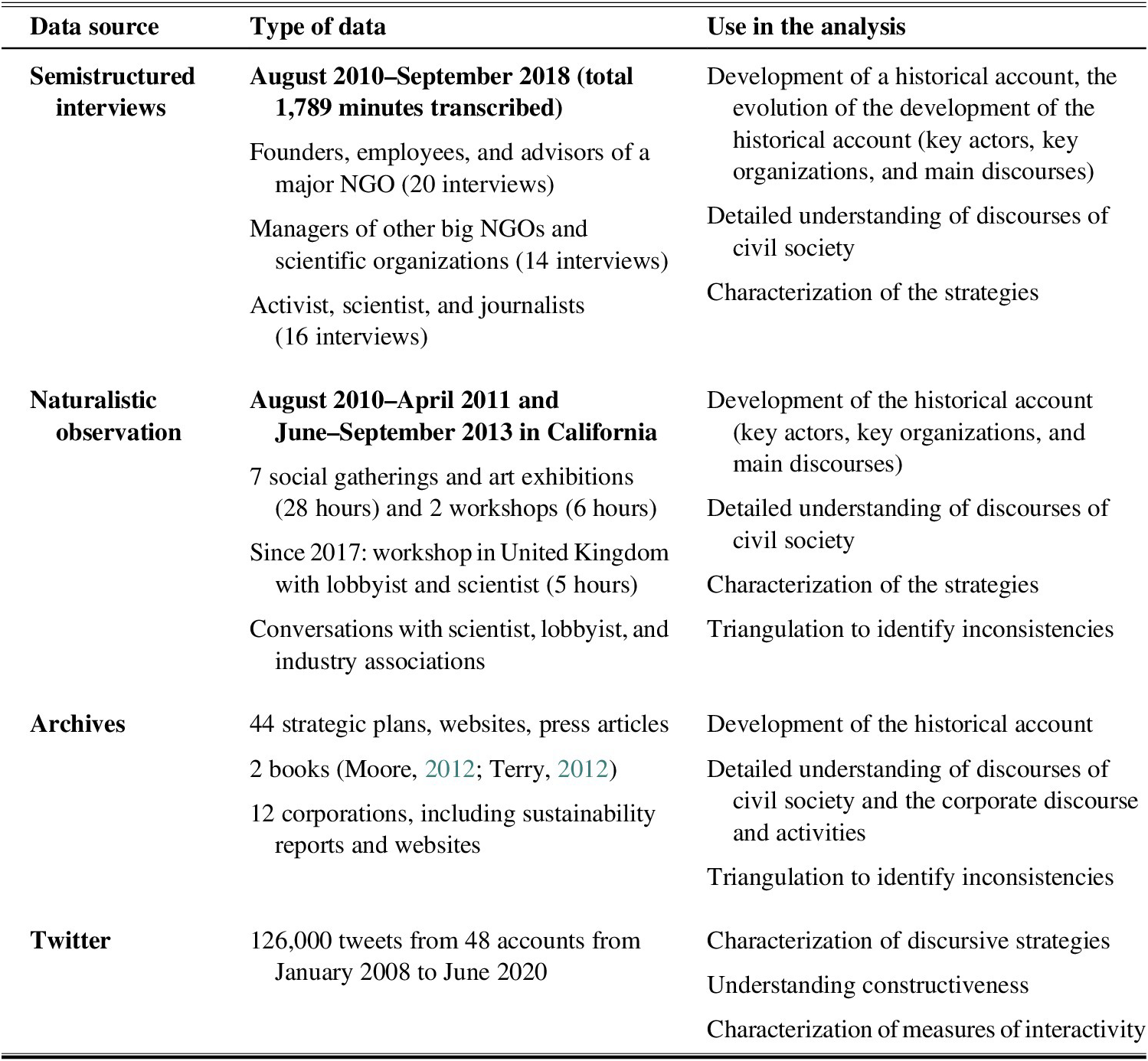

Table 1: Summary of Data Sources and Analysis

By 2020, however, the importance of plastic reduction had permeated corporate discourses. Big corporations, such as Unilever, Starbucks, and Nestlé, have integrated the reduction of plastic into their corporate social responsibility (CSR) policies (Castelló, Malcom, Murphy, O’Meara, Peacock, & Wyles, Reference Castelló, Malcom, Murphy, O’Meara, Peacock and Wyles2019). Also, governments and corporations in the United States and United Kingdom have developed multi-stakeholder initiatives, such as the UK Plastics Pact (signed in 2018) and the Alliance to End Plastic Waste. These include terms related to the elimination and eradication of plastics, advocating for circular economy solutions that favour plastic elimination.

Social media platforms have been hosting debates on the issue of plastic pollution between civil society actors and corporations. More specifically, Twitter has for the last ten years been the social media platform preferred by corporations and civil society actors to voice their activities (Lee, Oh, & Kim, Reference Lee, Oh and Kim2013; Rybalko & Seltzer, Reference Rybalko and Seltzer2010). Studies of political theory and business ethics have shown the influence of Twitter on social and political discourses, for example, the 2016 US presidential election and the 2016 UK Brexit Referendum (Grčar et al., Reference Grčar, Cherepnalkoski, Mozetič and Novak2017; Howard, Reference Howard2020; Marichal & Neve, Reference Marichal and Neve2020). The frequent use of Twitter by social figures like Sir David Attenborough and Greta Thunberg makes the platform one of the key spaces for deliberation on grand challenges like climate change and plastic pollution (Bennett, Reference Bennett2003; Dahlgren, Reference Dahlgren2005; Marichal & Neve, Reference Marichal and Neve2020).

For the purposes of our research, we analyse these debates going back to 2008, when the first specialized non-governmental organizations (NGOs) on plastic pollution, including PPC and 5 Gyres, joined Twitter, to gain an understanding of their strategies for changing the hegemonic discourse on plastic pollution.

Data Sources and Collection

To address our research question, we mobilized a rich set of data and studied the evolution of the discourses on plastic pollution over twelve years (from 2008 to 2020). Since 2010, we have been building expertise on the issue of plastic pollution through semistructured interviews, naturalistic observations, and the collection of archival data. These data have been partially used in an article published by the authors (Castelló et al., Reference Castelló, Malcom, Murphy, O’Meara, Peacock and Wyles2019). Unique to the current article, we gathered social media data, specifically from Twitter. Looking at the social media data with expert eyes allowed us to develop a novel methodology that combines artificial intelligence techniques with qualitative interpretation. Table 1 summarizes the data and their uses.

Semistructured Interviews

From 2010 to 2018, we conducted fifty semistructured interviews using a snowball sampling approach. Interviews, lasting fifteen minutes to two hours, were recorded and transcribed with interviewees’ consent (1,789 minutes transcribed). We conducted twenty interviews with the founders, employees, and advisors of one of the major US NGOs dedicated to plastic pollution. We carried out fourteen interviews with leaders of other well-established NGOs and sixteen interviews with individual activists and leaders of small anti-plastic organizations. Of the fifty people interviewed, forty-five were active in social media, especially Twitter, and four of them were social media managers. Interview data helped us better understand the key actors in the plastic pollution debates, their moral positions, and their strategies.

Naturalistic Observations

Since 2010, we have been gathering observational data from various events: five talks with industry associations, lobbyists, and consultants specializing in plastic; seven civil society organization events in California from August 2010 to March 2011 and from June to September 2013; and three workshops with civil society organizations, scientists, and lobbyists (in the United States and United Kingdom). These data provided a better understanding of the different moral positions and strategies in the discourses on plastic pollution.

Archival Data

We collected information from the websites and sustainability reports for twelve of the corporations that are most active on the issue of plastic pollution. The outcome of these data was published in an industry report (Castelló et al., Reference Castelló, Malcom, Murphy, O’Meara, Peacock and Wyles2019). To increase the internal and external reliability of our analysis and further understand the issue of plastic pollution, we used media articles, websites, emails, newsletters, academic articles, and two books by key actors (Moore, Reference Moore2012; Terry, Reference Terry2012). The archival data helped us better understand the evolution of the discourse of the different key actors as well as the relationships between these actors, including the corporations.

Social Media Data

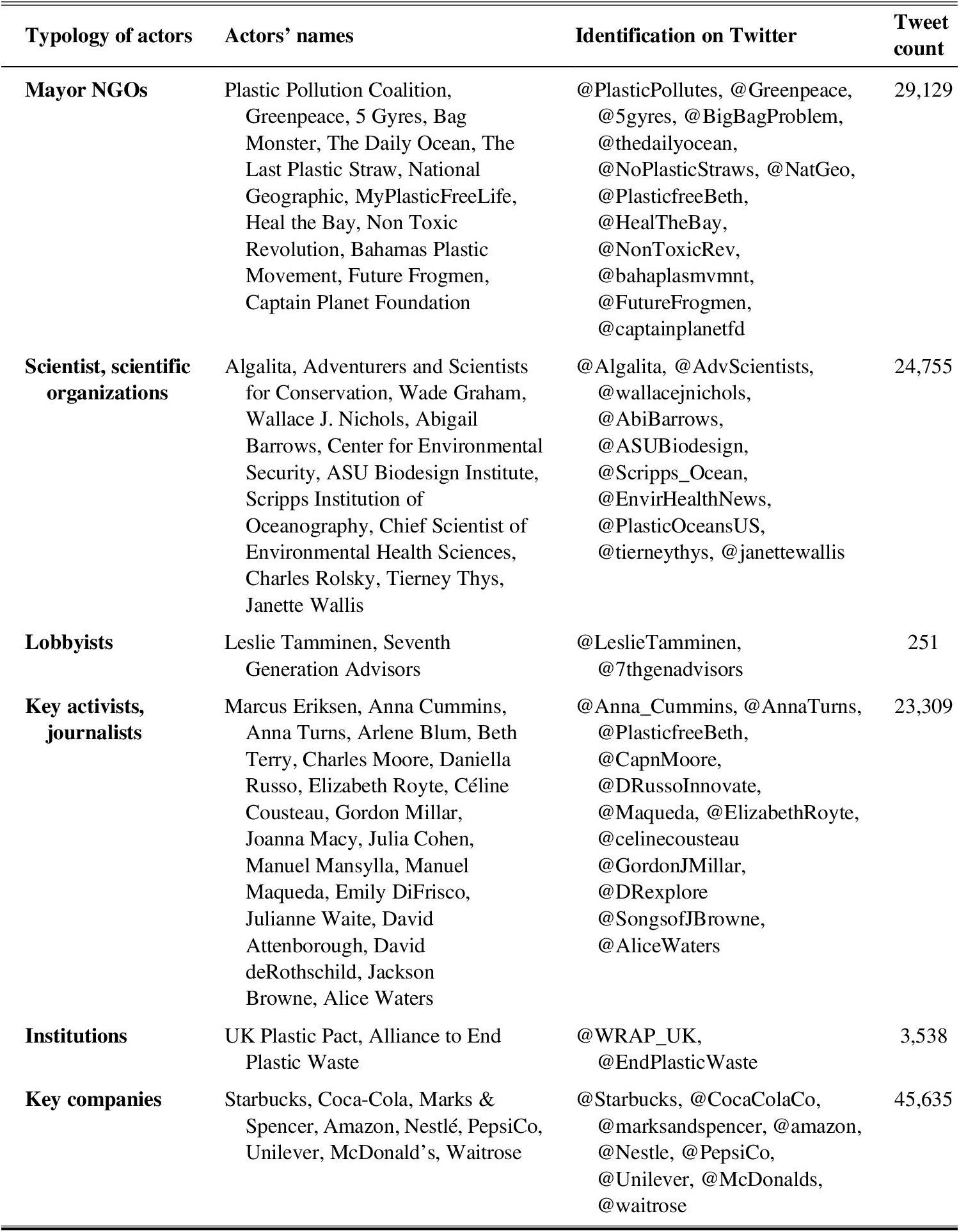

Social media platforms enable unobtrusive data gathering (Vesa & Vaara, Reference Vesa and Vaara2014: 293) from “naturally situated behaviours” (Kozinets, Reference Kozinets2002: 63) and interactions. We collected data from forty-eight Twitter accounts, using the Twitter API to harvest the tweets, and developed our own code to process and curate the data set. The selection of the sample was based on a coding performed from the interviews, observations, and archival data. The database spans 126,000 records and contains most of the tweets generated by the key actors from January 2008 to June 2020. We found a total of 26,285 tweets containing the words “plastic,” “recycling,” or “recycle,” forming our final sample. Table 2 contains details on key stakeholders and the stakeholders’ Twitter handles.

Table 2: Key Stakeholders and Their Twitter Identifications

Data Analysis

To be able to analyse the large amount of data, specifically the tweets, while being able to answer our research question, we followed four main analytical steps in an explorative and inductive-deductive method of theory generation.

Step 1: Open Coding on Actors and Discourses

We first performed open coding to identify key actors and the main features of their discourses. On the basis of the data from the interviews, observations, and archives, we developed a list of forty-eight key actors participating in Twitter on the issue of plastic pollution. We validated this list with the founder of one of the key NGOs. The list contained NGOs, key activists, scientists, associations, and corporations. We took a community-based approach (Kozinets, Reference Kozinets2015) to the analysis of social media. Knowing who the actors are, what they think, and how they talk allowed us to interpret quantitative results in context (Beninger, Reference Beninger, Sloan and Quan-Haase2017). It also helped to create two categories of actors that we designated as either civil society (including NGOs, activists, scientists, and associations) or corporations according to their opposed discourses on plastic pollution in 2008. The corporate–civil society segregation is often used in business ethics research (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020; Brand et al., Reference Brand, Blok and Verweij2020).

Step 2: Explorative Approach to the Online Deliberation

We took an explorative approach to understanding key features of the online deliberation (Steenbergen, Bächtiger, Spörndli, & Steiner, Reference Steenbergen, Bächtiger, Spörndli and Steiner2003), defining three key features: 1) constructiveness, 2) conversational themes and actors, and 3) measures of interactivity (reference, endorsement, and amplification).

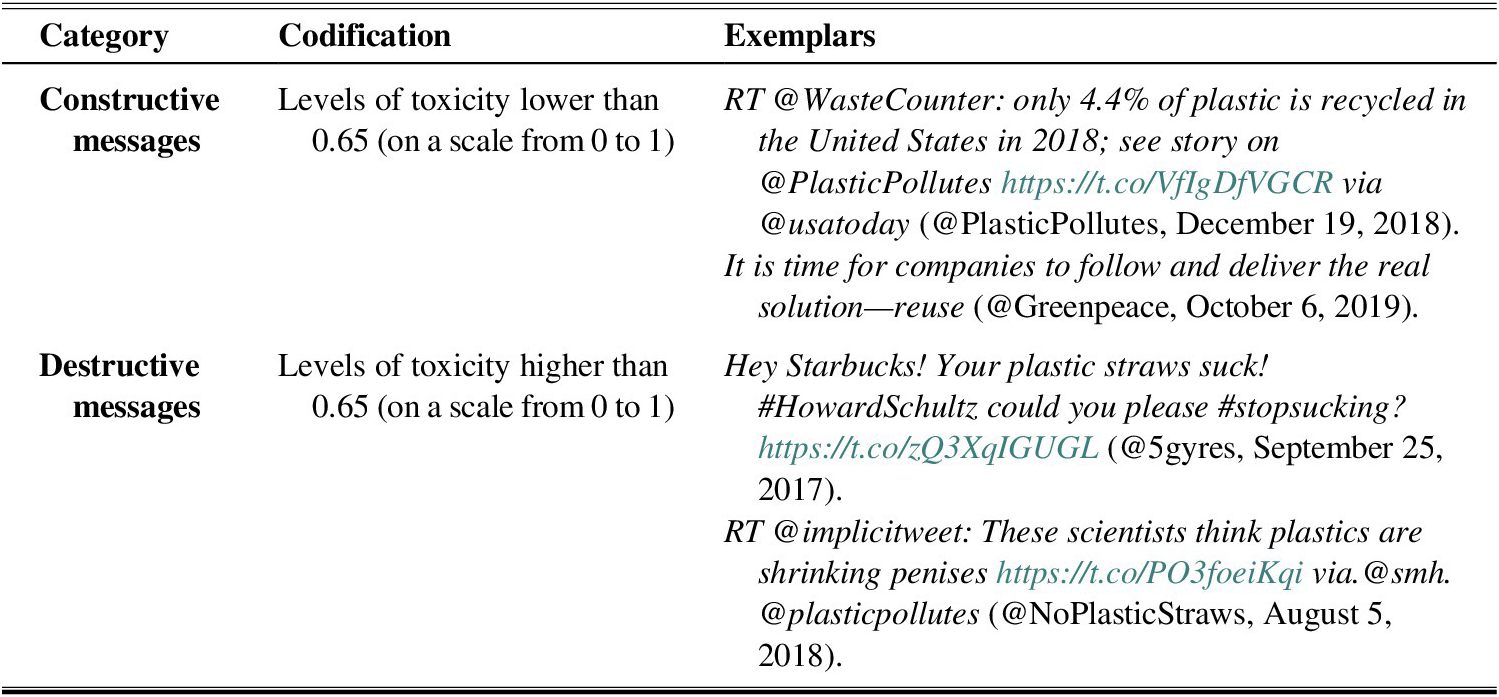

Constructiveness. Constructiveness suggests a low level of emotional toxicity in the messages constituting the engagements. A very high level of destructive messaging means that deliberation is not possible, as actors with polarized views are not willing to recognize other actors as adversaries (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005). We developed a natural language processing (NLP) engine that departs from the conventional, dictionary-based, algorithmic approaches to the analysis of text (e.g., Illia, Sonpar, & Bauer, Reference Illia, Sonpar and Bauer2014; Short, Broberg, Cogliser, & Brigham, Reference Short, Broberg, Cogliser and Brigham2010) and uses artificial intelligence techniques to achieve significant improvements in text classification tasks (Young, Hazarika, Poria, & Cambria, Reference Young, Hazarika, Poria and Cambria2018). We trained our engine to compute a set of basic affects (Crowston, Allen, & Heckman, Reference Crowston, Allen and Heckman2012). We further validated the performance of the engine using best practices in artificial intelligence (Devlin, Chang, Lee, & Toutanova, Reference Devlin, Chang, Lee and Toutanova2018) and Google’s technical support and found the engine’s precision levels to be above 85 percent. Assisted by the engine, we classified tweets on the basis of their level of “toxicity” as basic affect, on a scale from 0 to 1. We further validated the result of the measure of constructiveness with another sample of twenty thousand tweets based on the discourse of climate change activist Greta Thunberg. We selected Greta’s case given that mass media articles have found her to be the recipient of hate speech (Shrimsley, Reference Shrimsley2019); we therefore expected significant levels of destructive messages. In fact, we found low levels of destructive messages against this activist (0.5 percent), which supports our claims that conversations in Twitter can be constructive and not only destructive and polarized. Table 3 provides examples of constructive and destructive messages from our data sample on plastic pollution.

Table 3: Destructive versus Constructive Tweets

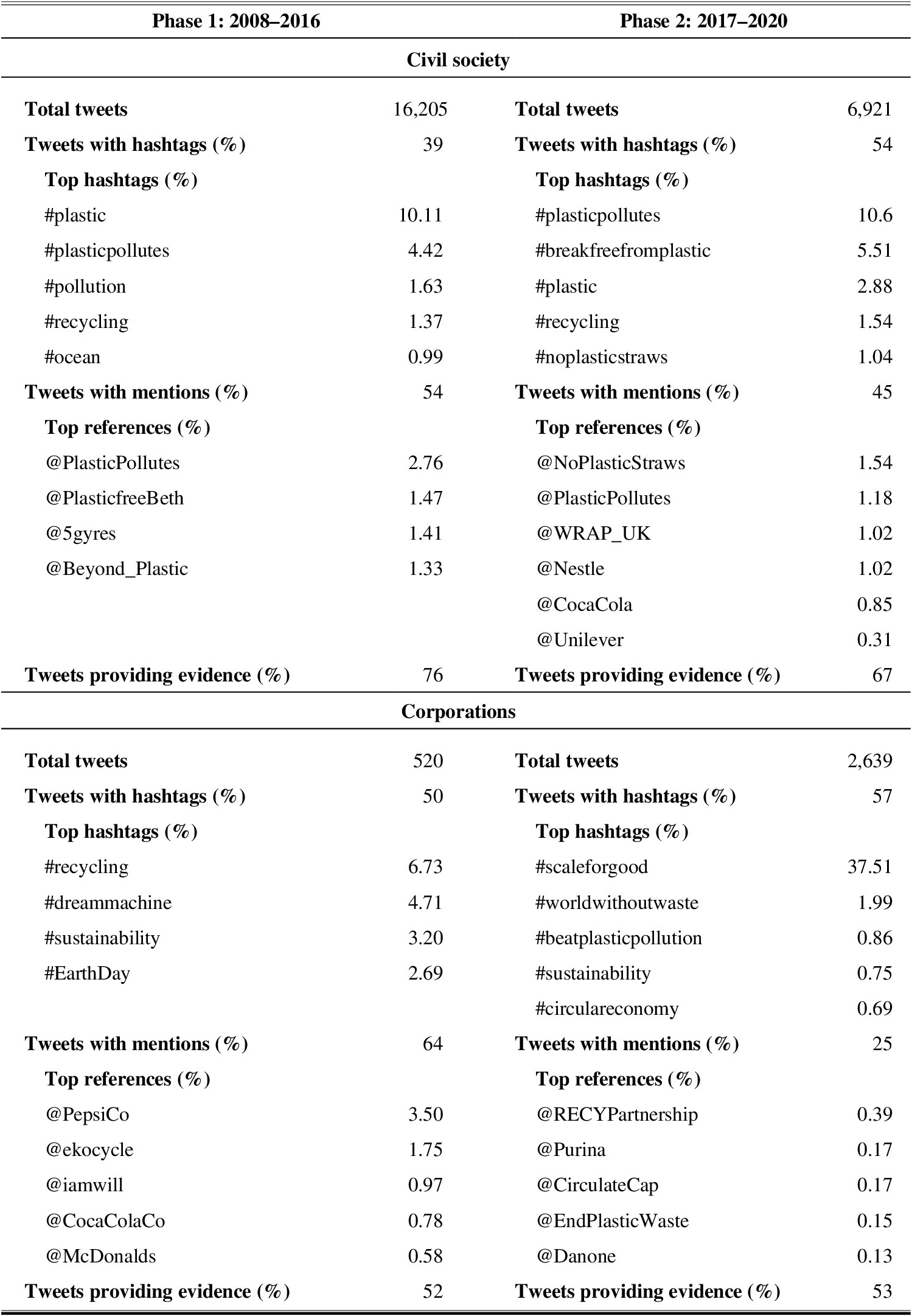

Conversational themes and actors. We took an exploratory look at the hashtags (represented by #) and main actors (represented by @) referenced in the tweets. Hashtags provide a first understanding of the central themes in the discourses (Rogstad, Reference Rogstad2016), and references define who is willing to talk with whom (Boyd, Golder, & Lotan, Reference Boyd, Golder and Lotan2010). We coded the database to map the hashtags and @ symbols over time to assess their weight in the sample. We concluded two phases that defined the evolution of the conversations: a first phase (2008–16) and a second phase (2017–20), as explained in the findings section. Table 4 shows the most frequent hashtags and @ per stakeholder per phase.

Table 4: Main Hashtag and Correspondent Actors (@) by Phase and Actor Category

Measures of interactivity (reference, endorsement, and amplification). We also performed a quantitative analysis of the interactivity of messages as a measure of engagement (Castelló et al., Reference Castelló, Etter and Nielsen2016; Marichal & Neve, Reference Marichal and Neve2020). Interactivity measures define the capacity of the tweet to be part of a broader conversation, whether this is because it mentions another user in the conversation (using the symbol @) or because it is supported by other users (indicated by “likes”) or because it is retweeted (a retweet is when the user forwards to the user’s network a message that was not written by the user). Retweets have been defined as elements in which key users or influencers are able to have their voices echoed (Rogstad, Reference Rogstad2016; Wu, Mason, Hofman, & Watts, Reference Wu, Mason, Hofman and Watts2011). On the basis of the aforementioned literature, we define three main measures of interactivity: reference, endorsement, and amplification. Reference is a discrete categorical measure with three categories: category 0 (tweets with no @), category 1 (tweets referring to other users by @), and category 2 (tweets directly responding to previous tweets). Endorsement is a discrete ordinal measure with three levels: level 0 (tweets with zero likes); level 1 (tweets with one to ten likes in the 75 percent quantile), and level 2 (tweets with more than ten likes above the 75 percent quantile). Amplification is a discrete ordinal measure with three levels: level 0 (tweets with zero retweets); level 1 (tweets with one to twelve retweets in the 75 percent quantile), and level 2 (tweets with more than twelve retweets above the 75 percent quantile). With these measurement instruments in place, we analysed the level of interactivity of the constructive and destructive tweets. Given the categorical nature of reference, we did not include this in the comparison. From these measures, we concluded that, in our sample, 1) most of the tweets had a constructive intent and 2) constructive tweets had higher levels of interactivity. Table 5 describes the measures of reference, endorsement, and amplification in constructive versus destructive tweets.

Table 5: Measures of Interactivity—Constructive versus Destructive

Note. The difference is also statistically significant in the two ordinal variables considered: endorsement and amplification, F(2, 26,066) = 48.02, p <.001. We did not include the interactivity measure of reference because it is a categorical measure and the others are ordinal measures, as explained in the methods.

Encouraged by these results, we continued analysing the sample to answer our research question about the use of affects in the strategies of civil society actors to change hegemonic discourses.

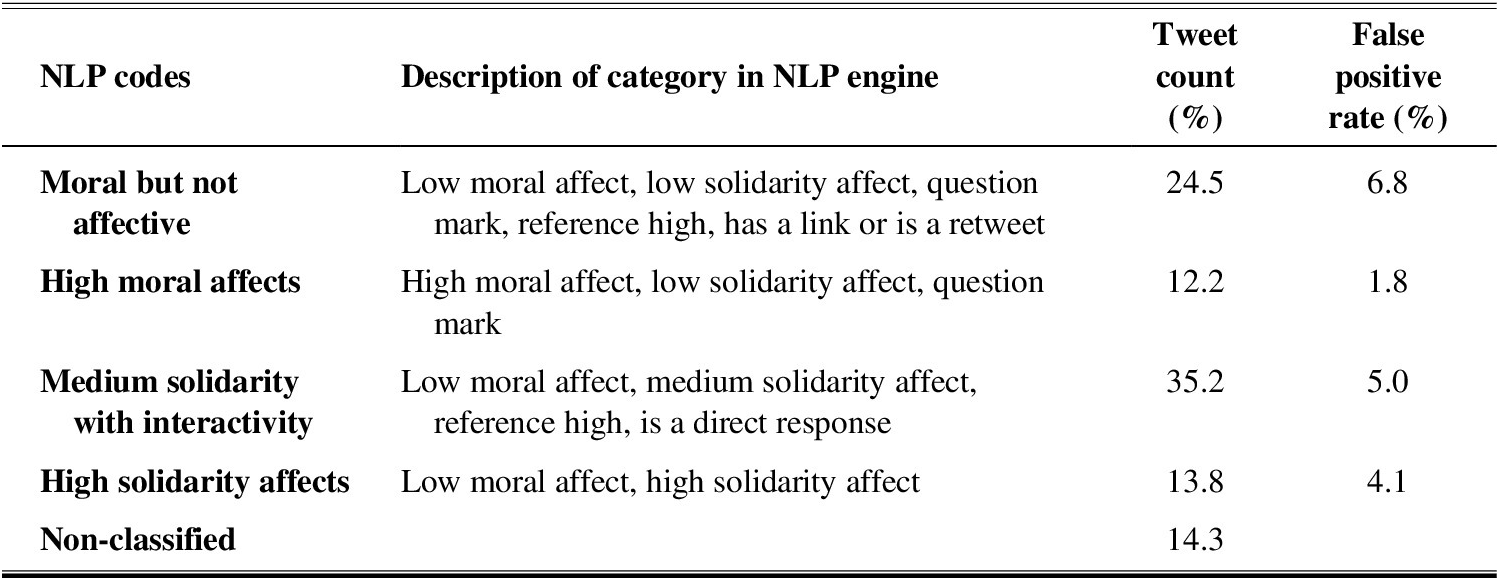

Step 3: Data Coding

We performed an inductive-deductive process of open coding to identify the discursive strategies of civil society. Two researchers looked at 10 percent of the constructive tweets of the civil society sample to seek out initial patterns. Upon looking at the data, we first noticed the importance of affective expressions like “shameful!,” “shame,” “horrific.” We also observed that users asked questions, such as “Does microplastic make us sick?” Users expressed joy and excitement about their arguments (e.g., “This is great news!”). On the basis of the diversity of the affective content and the literature, we coded the data with our engine to produce a first quantitative understanding of the emotional content of the data. We defined two emotional signals: moral affects (as a composite of anger, fear, and sadness) and solidarity affects (a composite of love, joy, and trust). It took us several cycles of iterations, involving reading tweets and classifying them both manually and assisted by the NLP engine, to create a codification of the tweets that reflected the qualitative understanding of the engagement activities based on a high percentage of tweets. We complemented the codification of affective signals (moral affects and solidarity affects) with other key codes, such as “?,” and interactivity signals, such as @, retweets, and links, which allowed us to better define groups with complete meaning. We ended up with four coding categories: 1) high moral affects (composed of high moral affects, low solidarity affects, and question marks), 2) moral but not affective (composed of low moral affects, low solidarity affects, question marks, reference high, and has a link or is a retweet), 3) medium solidarity with interactivity (composed of low moral affects, medium solidarity affects, reference high, and is a direct response), and 4) high solidarity affects (composed of low moral affects and high solidarity affects). In this process, the authors visually inspected a random sample (30 percent of each category) to compute accuracy levels. A total of 85.3 percent of all the tweets inspected were classified with false positive rates ranging from 1.2 percent to 5.6 percent (refer to Table 6), which we considered a good result.

Table 6: Natural Language Process (NLP) Codes

Note. n = 26,285. Table 4 provides information on the number of tweets classified across stakeholders; 85 percent of the tweets have been classified.

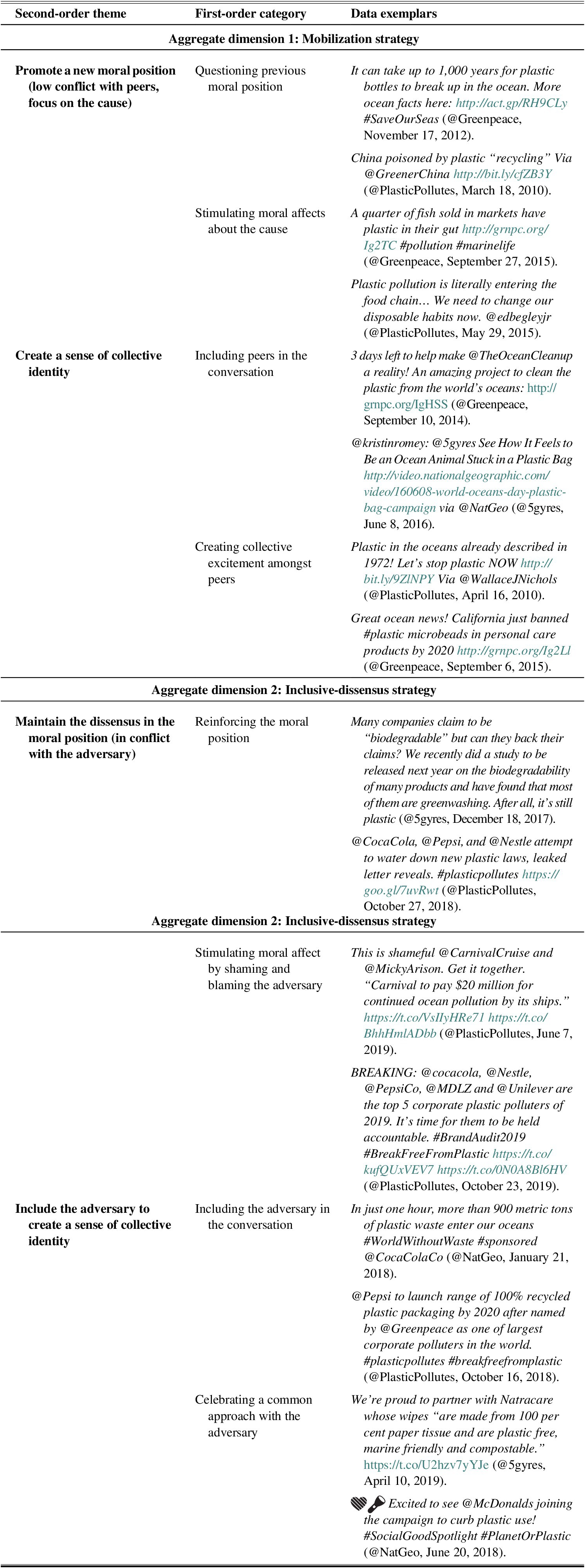

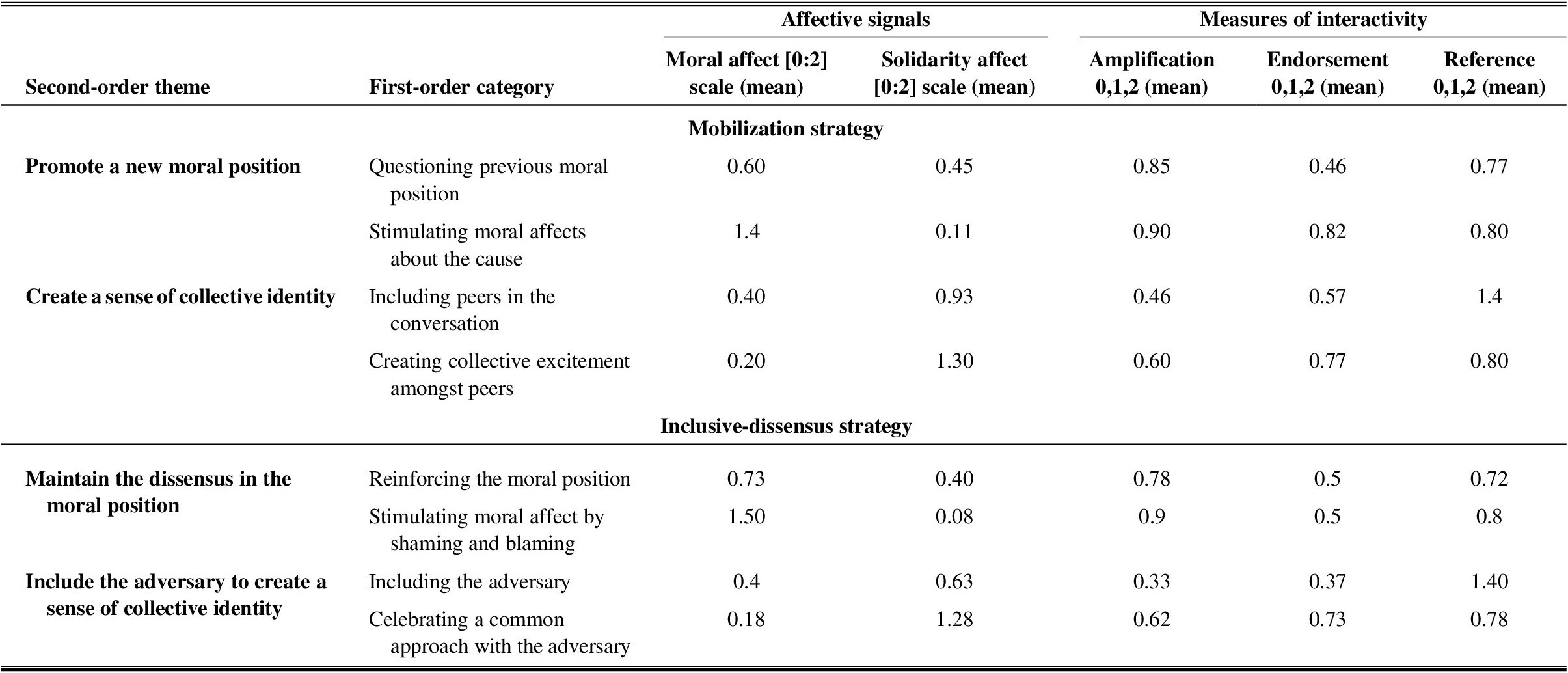

Step 4: Aggregate Dimensions and Model Development

After the initial coding, we sought out particularities in the two different phases previously identified and in relation to conversations with peers or corporations. We cross-checked our emergent understandings by returning to the data, inspecting the data per phase, and returning to the interview data to ensure our interpretations were consistent. We then developed a model that refined our first “by-phase” coding and created eight first-order categories, aggregating them into four second-order themes and two aggregate dimensions. Table 7 describes the data structure and provides data exemplars. We then analysed levels of affective signals (moral and solidarity) and the interactivity measures for each of the first-order categories, and we depict the means in Table 8. To segregate by type of actor, we added to the engine the tag “mentions a corporation or not.”

Table 7: Engagement Strategies (First-Order Categories, Second-Order Themes, Aggregate Dimensions, and Data Exemplars)

Table 8: Affective Signals and Interactivity per Strategy

FINDINGS

We describe the social media strategies used by the civil society actors to transform the hegemonic discourse of plastic pollution from one that fixates on recycling to one that acknowledges the importance of reducing plastic use. We first show how constructive engagements happen in social media. Second, we describe the strategies.

On the constructiveness of the engagements, we found that only 1.4 percent of the tweets were destructive (given a toxicity threshold of 0.65) (see Table 3 for examples of constructive vs. unconstructive tweets). We also found that constructive messages had higher levels of interactivity (as evidenced by basic statistics, such as the difference in the means and standard deviations; see Table 5). The difference is also statistically significant in the two ordinal variables considered: endorsement and amplification, F(2, 26,066) = 48.02, p <.001. Furthermore, we found that affective tweets had higher levels of interactivity than the less affective ones (see Table 8; also explained later). We therefore argue that, despite stakeholder engagement occurring between stakeholders with opposed views, Twitter was a space of constructive engagement. Affects were used to drive change in audiences’ discourses. Affective messages had higher levels of interactivity than less affective ones.

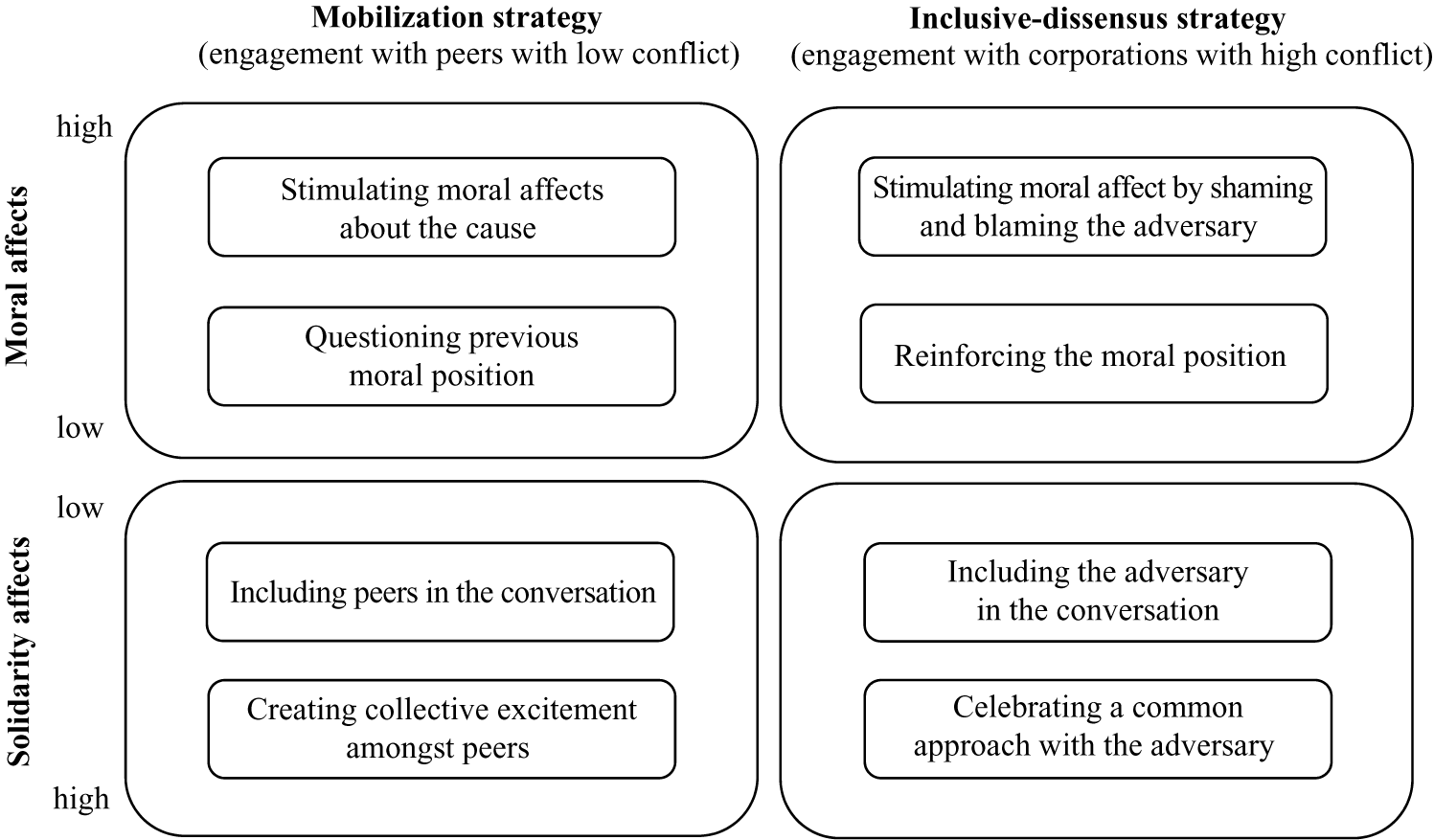

We observed two strategies carried out by civil society actors that we cluster into two phases: a first phase from 2008 and 2016, in which civil society actors mainly performed a “mobilization” strategy, and a second phase from 2017 and 2020, in which civil society actors maintained the mobilization strategy with peers while embarking on an inclusive-dissensus strategy with corporations. In the mobilization strategy, civil society actors promoted a moral position that focussed on the importance of reducing plastic consumption. They also worked on creating a sense of collective identity by including their peers in the conversation and creating collective excitement. Surprisingly, in the inclusive-dissensus strategy, civil society actors did not negotiate a common perspective with corporations. They maintained their moral position, shaming and blaming corporations for pollution. At the same time, they recognized the legitimacy of corporations, including them in their conversations and celebrating a common approach when it occurred. Key to these two strategies was the use of moral and solidarity affects. Moral affects were used to enhance the moral position, whereas solidarity affects avoided disengagement and polarization. Recognizing the legitimacy of corporations in the debate helped the corporations convert to some of the key features of the civil society discourse, such as the importance of reducing plastic use and the principles of a circular economy. Figure 1 represents the two strategies and their relation to affects.

Figure 1: Model of Strategies of Stakeholder Engagement

Phase 1 (2008–16): Mobilization Strategy

Since their founding around 2008, most civil society organizations, such as PPC, Algalita, and 5 Gyres, used Twitter to promote the counter-hegemonic discourse of plastic pollution. Twitter was the preferred tool, as Grant, founder of a lead NGO, explained: “I learn every day how to connect with people. Twitter has helped a lot with that. Twitter is awesome, is incredible. Because you can only use 140 characters you have to be concise. People notice yourself [sic]” (Grant, 2009). The mobilization strategy consisted of promoting the new moral position amongst other peer activists (with emphasis on the importance of reducing plastic), while making them feel part of a growing collective.

Promoting a New Moral Position

A new moral position based on the idea of reducing plastic use was promoted at first, questioning the previous moral position. Second, stimulating moral affects about the cause of plastic pollution made peer activists feel overwhelmed about the issue of plastic pollution but also made them feel affectively attached to it.

Questioning the previous moral position and disseminating information on the new one. A common way of disarticulating the discourse of recycling in tweets and rearticulating the discourse of refusing was to state the problems about recycling and support the importance of reducing plastics with new information. This was communicated via the sharing of links to scientific reports or other information about the impacts of plastic pollution. The links to scientific reports or reputable mass media articles helped civil society actors not only present their new moral position but also legitimize their arguments and bolster their positions as knowledge providers. For example, in the following tweet, Algalita questioned the recycling principles and provided a link to a recent report issued in the GreenBride Guide: “How many of those shiny plastic sippy cups will still be here in 30 years? Let’s hope none. @GreenBrideGuide http://t.co/t3WHvsNpAA” (@Algalita, November 19, 2013). Greenpeace, in the following tweet, pointed at the problem of plastic consumption and the fact that plastic is not recycled. To support this view, it shared a scientific map of plastic pollution: “5 trillion pieces of plastic floating in our oceans. This map shows you where. http://grnpc.org/IgNMi” (@Greenpeace, May 29).

Civil society actors also used Twitter hashtags, such as #plasticpollutes, #plasticpollution, #refuse, and #plasticfree. They created new vocabularies for rearticulating the discourse about plastic, which enabled people to communicate differently. As Colin, cofounder of one of the lead NGOs, argued, “we started to create a kind of collective intelligence; a crowdsourcing of ideas…. It was really helpful…. There is an increasing whole market of alternatives to plastic and suddenly somebody was finding something new and sharing it” (Colin, 2018). Promoting the new moral position by sharing ideas is shown in the following tweet by Manuel Maqueda, cofounder of PPC: “@realrawlive http://twitpic.com/7f9f9—How do I buy these zero-plastic bottles?” (@Maqueda, June 15, 2009). In line with the sharing of fresh knowledge while promoting the new vocabulary of the plastic-free life and plastic pollution refusal, some of the civil society actors organized public debates that helped them question previous moral positions and position themselves as experts in the cause, as exemplified by lead activist Beth Terry in the following tweet: “In the mood to chat with me and http://t.co/CFPz8vz4cq about the chemicals in plastic? Join us on Twitter in about 30 minutes. #LTKH” (@PlasticfreeBeth, November 18, 2014).

Stimulating moral affects about the cause. Pointing out the impossibility of recycling and sharing links and tips for how to live a plastic-free life were not enough to disarticulate the discourse of recycling. Refusing plastic required an enormous effort to change everyday behaviours. Civil society actors used messages with strong moral affects (e.g., horror and anger) to spark moral shock. As Will, a lead activist, argued, “it began with emotional connection that people have with beautiful places and animals learning that this places and animals are being harmed by our pollution. That was the entry point. Simple explanation. This is how people get engaged” (Will, 2010). The strategic use of affects is shown in two tweets by Greenpeace: “Terrible—8m tons of #plastic waste are dumped into the ocean each year, and it’s growing http://grnpc.org/IgtzX” (@Greenpeace, July 22, 2015) and “Horrible. Our #oceans could contain more #plastic than fish by 2050. http://grnpc.org/IgSZD” (@Greenpeace, January 20, 2016). The repetition of moral affective expressions like “horror” and “terrible,” combined with images of baby albatrosses, whales, and sea otters dying from ingesting colourful plastic objects (bags, lids, toys), helped to promote the moral shock needed to shake behaviours, as in the following tweet: “The Plastic You Use Is Killing Animals the World’s Most Remote Islands http://ow.ly/PlwUf #plasticpollution” (@5gyres, July 8, 2015). These images were intended to viscerally connect people to the problem and promote engagement, as evidenced by high levels of moral affect (1.4), amplification (0.9), endorsement (0.82), and reference (0.8) compared with the less affective tweets (see Table 8).

Create a Sense of Collective Identity

In the mobilization strategy, civil society actors also worked at creating a sense of collective identity by including peers in the conversation and creating collective excitement with highly affective tweets.

Including peers in the conversation. Civil society actors strategically worked on connecting with other peers, as Grant, founder of a lead NGO, explained: “I’ve chosen to support some people: J. Nichols, Manuel Maqueda…. It is all very tactical. They have their own networks. It is about the influencers. It is also [a] reciprocate [sic] [strategy]” (Grant, 2009). Civil society actors were, for example, retweeting others’ messages: “RT @1Child1Planet: @PlasticfreeBeth Agree, saving money is an occasional bonus of going plastic free, but shouldn’t be primary motivator” (@Bridget_M, April 17, 2014), which indicated a willingness to include others in the conversation. The preceding tweet is also an example of connecting with other people via a direct call, such as by using the @ symbol (i.e., @PlasticfreeBeth and @1Child1Planet) in conjunction with expressions like “agree.” This strategy helped civil society actors not only to include more people in the debate but also to promote moral rightness about the importance of reducing plastic consumption. There is a similar dynamic, in the willingness to connect with other actors via @ and expression of moral rightness, in the following tweet, which concerns the problem of wrapping food: “Totally agree with @tomsfeast via @guardian—no need to smother fruit and veg in plastic wrapping” (@AnnaTurns, June 28, 2017).

Most of the messages civil society actors issued in this strategy were aimed at relating to peer organizations or key activists, such as PPC (@PlasticPollutes), Beth Terry (@PlasticfreeBeth), 5 Gyres (@5gyres), and J. Wallace Nichols (@wallacejnichols) (see Table 4). As Janette, a lead activist, argued, hashtags and @ symbols were used to connect with others: “Through social media, the use of hashtags has been fantastic to connect up with other people. There is a real online community of people…. Also, it fosters a sense of that collective identity” (Janette, 2018).

Creating collective excitement amongst peers. As a fundamental part of their strategy, civil society actors issued highly emotional tweets aimed at creating a sense of collective excitement and endorsement. Tweets contained expressions of joy but also of trust. These were intended to create solidarity affects, helping activists feel part of a collective and creating a sense of belonging to a community. As Colin, one of the founders of a lead NGO argued, the creation of a sense of collective identity was a premeditated strategy: “I wanted to highlight always that we were together in this … we are learning together … was my way to apply compassion” (Colin, 2018).

In the following tweet, Daniela Russo, cofounder of one of the major NGOs, expressed her support for a new organization (KUMU) with which she created solidarity affects with the expression “awesome!”: “RT @KUMUlab: Awesome wording! ‘retro innovation’ meaning going back to things that worked. Dan Imhoff says at #beyond_plastic event” (@DRussoInnovate, June 16, 2013). Other expressions of solidarity affects (such as “nice work!”) were used by the civil society actors to promote a sense of achievement and a sense of collectivity: “Nice work! @SeaWorld Says Goodbye to Plastic Bags | http://bit.ly/IeqKGt” (@5gyres, April 27, 2012). Greenpeace, in the following tweet, expressed happiness and joy about people’s intention to stop using plastic bags: “Happy International Plastic-Bag Free Day! Try not using plastic bags today… and why not tomorrow? and the next day?” (@Greenpeace, July 3, 2012). Collective excitement tweets had higher levels of interactivity than less affective tweets in the “including the peers” category: amplification (0.60 compared to 0.46); endorsement (0.77 compared to 0.57) (see Table 8).

Corporate Discourse in Twitter

From 2008 to 2016, corporations were still reluctant to use Twitter to engage in plastic-related conversations. Corporations issued only 3,180 related tweets (by way of comparison, NGOs posted 11,090 tweets in the same period). Corporate hashtags mainly presented their positions regarding recycling and sustainability: #recycling, #EarthDay, #recycle, #greenresolutions, #sustliving. Their @ symbols signalled other companies or private initiatives, for example, @PepsiCo, @ekocycle, @iamwill (see Table 4 for more examples). Grant confirmed the silence of corporations: “We are independently jumping. BP [British Petroleum as example of a corporation] is missing an opportunity, it helps. They cannot convert the masses. [What we do is] what drives a global transformation” (Grant, 2009).

Phase 2 (2017–20): Inclusive-Dissensus Strategy

Around 2017, the engagement scene on Twitter started to change. Corporations increased their involvement in the debate, and civil society actors modified their engagement strategies to connect with corporate actors in the conversations. But civil society actors did not negotiate a new moral position with corporations. They maintained their moral position, focussed on reducing plastic production and consumption, while including corporations in the conversation by identifying them as partly responsible for the problem and inviting them to join the cause by converting to the moral position of reducing plastic use. This was done with an inclusive-dissensus strategy. The inclusive-dissensus strategy consisted of maintaining the dissensus in the moral position while being inclusive with the adversary to create a certain sense of collective identity and avoid disengagement and polarization.

Maintaining the Dissensus in the Moral Position

The first step in maintaining the dissensus in the moral position was to reinforce in the messages the importance of reducing plastic use and to stimulate moral affects by shaming and blaming the corporations.

Reinforcing the moral position. The importance of plastic use reduction was maintained as a key message in the new tweets. The hashtags continued to reinforce the moral position on plastic pollution (e.g., #breakfreefromplastic, #noplasticstraws; see Table 4 for more examples). Tweets were also strategically used to reinforce the reduce/refuse message, as shown in the following tweet by Greenpeace: “Would you rather—have oceans full of fish, or full of plastic? It’s time to #BreakFreeFromPlastic! Here’s what you can do: https://act.gp/2qNp6q5” (@Greenpeace, April 20, 2018). In the following tweet, the PPC quotes Diana Cohen, a lead activist and founder of the organization, who criticizes the throwaway culture implicit in the recycling discourse: “‘I’m hoping people wake up to the beauty of reusables and disengage from all of these throwaway to-go cups and this whole throwaway mentality that we’ve become acclimatized to, because it’s completely unsustainable,’ said Dianna Cohen @implicitweet https://t.co/ZZrPf3FYar” (@PlasticPollutes, August 28, 2018). Some of these tweets also pointed at companies and their recycling policies or, as in this tweet, the claim of biodegradability: “Many companies claim to be ‘biodegradable’ but can they back their claims? We recently did a study to be released next year on the biodegradability of many products and have found that most of them are greenwashing. After all, it’s still plastic” (@5gyres, December 18, 2017). Other tweets targeted specific corporations, such as Coca-Cola or Nestlé, and their recycling strategies: “Companies like @cocacola, @nestle and @pepsi are increasing the amount of single-use plastic. Recycling can’t manage this. Ask companies to stop #plasticpollution they helped to create: https://act.gp/2EDGFSQ #BreakFreeFromPlastic” (@Greenpeace, October 23, 2018).

Stimulating moral affects by shaming and blaming the adversary. Reinforcing the moral position was complemented with highly affective tweets. In the inclusive-dissensus strategy, rather than focusing on the problem of plastic pollution (as in the mobilization strategy), the tweets directed blame at the corporations with the aim of making them feel shame. Specific corporations were identified as responsible for the production of plastic and also blamed for their adherence to the discourse of recycling. The following tweet from PPC shamed supermarkets for pollution and their recycling strategies, using expressions like “shelves of shame”: “Shelves of Shame: Are These the Worst Recycling Offenders in the Supermarkets? #plasticpollutes https://t.co/XMltPtwXhU https://t.co/g2i8YdCwCE” (@PlasticPollutes, May 17, 2019). The organization 5 Gyres directly blamed Coca-Cola for polluting the oceans, arguing that the company had “choked the oceans”: “Hey #CocaCola: Stop choking our oceans with plastic! #BreakFreeFromPlastic http://thndr.me/caBWwW https://fb.me/9raYdW130” (@5gyres, January 2, 2018). In this tweet, Greenpeace used the expression “we have had enough!” to express its anger when blaming Nestlé for the problem: “Single-use plastic pollutes our environment and destroys communities. @Nestle produced 1.7 million tonnes of plastic last year, and has no plans to stop. Tell @Nestle we have had enough! https://act.gp/2HKAJbu #BreakFreeFromPlastic” (@Greenpeace, March 28, 2019).

Blaming and shaming corporations was conceived as not so much a way of attacking corporate reputations as a way of activating solutions, as evidenced by the Greenpeace tweet that calls for Nestlé to reduce the production of plastic. This is also explained by Helena, a lead activist:

We use that [tweets with images of dead animals and strong affects] to activate solutions…. For example, in California there’s a bill called Connect the Caps that would require that Nestlé and Coca-Cola and others, who are producing single-use bottles, have the cap connected to the bottle…. So that was a great example of how we activate those solutions…. If it’s a ladder of engagement, if you will, it’s all about moving them from that first step of seeing the symbol, seeing the photo… and then going all the way to that step of getting educated and getting activated (Helena, 2018).

Be Inclusive to Create a Sense of Collective Identity

To create a sense of collective identity, civil society actors created tweets that included the adversary in the conversation and celebrated a common approach.

Including the adversary in the conversation. The shaming and blaming tweets were complemented with tweets that aimed at including the corporations in the conversation with the intent of taking them up the “ladder of engagement” (as Helena argued in the preceding quote). These tweets were less emotional, containing low signals of moral affects and solidarity affects (0.4 and 0.63, respectively; refer to Table 8). The intention of these tweets and hashtags was to develop links between civil society and the companies and create direct conversations. For example, civil society used some hashtags for initiatives the corporations were also promoting (e.g., #reuse, #recycle, #EarthDay, #circulareconomy, #didyouknow) (see Table 4 for more examples). This connection with corporate conversations was also reflected in the strategic use of the @ symbol as a sign of inclusion. Civil society actors connected through the @ symbols with corporations like Nestlé, Coca-Cola, Unilever, and PepsiCo (see Table 4 for more examples). This strategy was reflected in the following tweet by Greenpeace directed at Coca-Cola: “Hey @CocaCola, you hope no one notices all the plastic bottles floating in the ocean. But we did http://act.gp/2nD5NQB” (@Greenpeace, April 18, 2017). This tweet, like many others, is confrontational and ironic, but other tweets were more inclusive, as exemplified by the following tweet that uses the first person plural (“let’s”) to signal Greenpeace’s involvement: “@CocaCola produces over 100 billion plastic bottles every year. Let’s do something about it. http://act.gp/2oQPQ9I #EndOceanPlastics” (@Greenpeace, October 4, 2017). The following tweet, by 5 Gyres, shows a will to engage directly with a corporation, in this case, Starbucks:

@Starbucks serves 4 BILLION+ plastic-lined cups, lids & straws each year, most aren’t recyclable. Demand they address #StarbucksTrash TODAY at the shareholder meeting at 10am! ![]() https://www.stand.earth/starbucks-problem #breakfreefromplastic #sneakystyrene Check our FB for Live vid! (@5gyres, March 21, 2018).

https://www.stand.earth/starbucks-problem #breakfreefromplastic #sneakystyrene Check our FB for Live vid! (@5gyres, March 21, 2018).

Celebrating a common approach. Civil society actors complemented the inclusion tweets with tweets with high solidarity affects. Civil society actors celebrated in their tweets a common approach with companies, as in the following tweet by the PPC:

Happy #EarthDay! We are excited to announce the launch of #BYOBottle, a music industry effort to turn the tide on plastic pollution, Click to commit to #BYOBottle & join the movement to reduce #plasticpollution in the music industry. @BYO_Bottle https://t.co/H01LaeuojO https://t.co/SRWzApgMNq (@PlasticPollutes, April 22, 2019).

In the following tweet, National Geographic celebrates IKEA and HP joining a new plastic reduction initiative: “![]() #SocialGoodSpotlight: We’re so happy to see @HP and @IKEAUSA joining @nxtwaveplastics in their commitment to ‘turn off the tap’ of plastic entering the ocean #planetorplastic” (@NatGeo, November 4, 2018). Civil society also issued tweets with high solidarity affects when celebrating changes in the companies’ discourses and strategies, as in the following tweet by Greenpeace: “The UK supermarket chain @IcelandFoods is going plastic free! They’ve committed to eliminate plastic packaging in all their own-brand products within 5 years

#SocialGoodSpotlight: We’re so happy to see @HP and @IKEAUSA joining @nxtwaveplastics in their commitment to ‘turn off the tap’ of plastic entering the ocean #planetorplastic” (@NatGeo, November 4, 2018). Civil society also issued tweets with high solidarity affects when celebrating changes in the companies’ discourses and strategies, as in the following tweet by Greenpeace: “The UK supermarket chain @IcelandFoods is going plastic free! They’ve committed to eliminate plastic packaging in all their own-brand products within 5 years ![]() Who’s next? http://act.gp/2FJdiey #PlasticFree” (@Greenpeace, January 1, 2018). The following tweet by Heal the Bay is also highly affective (using the heart symbol and expressions like “going green!”) when celebrating the company Yelp becoming greener and therefore converting to some of the new discourse on reducing plastic use:

Who’s next? http://act.gp/2FJdiey #PlasticFree” (@Greenpeace, January 1, 2018). The following tweet by Heal the Bay is also highly affective (using the heart symbol and expressions like “going green!”) when celebrating the company Yelp becoming greener and therefore converting to some of the new discourse on reducing plastic use:

What’s for dinner? @Yelp is going green! Now, when you check-in to a restaurant, Yelp will ask about plastic usage and plastic-free options. All the collected data will help inform customers about sustainable restaurants by next year ![]() https://t.co/d7RE1K5VsJ (@HealTheBay, May 3, 2019).

https://t.co/d7RE1K5VsJ (@HealTheBay, May 3, 2019).

Celebratory tweets had higher levels of interactivity than less affective tweets in the including the adversary category: amplification (0.62 compared to 0.32); endorsement (0.73 compared to 0.37) (see Table 8).

Corporate Discourse on Twitter

From 2017 onwards, corporations significantly increased their presence in Twitter’s plastics debate, posting five times the number of tweets they had posted in the previous period (2,639 vs. 520) (refer to Table 4). Corporate discourse in Twitter continued to be concerned mainly with the importance of recycling, as in this example from Unilever: “We’re pleased to announce a new partnership with @Veolia to improve waste collection and recycling infrastructure, starting in India and Indonesia. Our joint ambition is to help create a #circulareconomy for plastic waste https://t.co/JqH8C9sEHu” (@Unilever, October 24, 2018).

Although their moral position on the importance of recycling had not changed, corporations had introduced into their discourse some elements of the counter-hegemonic discourse of reducing plastic use. For example, corporate hashtags signalled a slightly new moral position that called for “beating plastic pollution,” or they cited the principles of the circular economy, a central concept of which is to reduce the amount of polluting materials in the design of products (e.g., #beatplasticpollution, #circulareconomy). Other hashtags signalled campaigns and events that were shared by the civil society organizations (e.g., #scaleforgood, #EarthDay, #didyouknow) (see more in Table 4). Furthermore, tweets from some corporations, such as Starbucks, signalled some conversion to the new discourse of reducing plastic use: “We plan to eliminate single-use plastic straws globally by 2020” (@Starbucks, July 9, 2018).

Summing up, we show how from 2017 onwards, civil society actors began to recognize the legitimacy of corporations in their engagements on plastic pollution. The inclusive-dissensus strategy allowed them to maintain a strong moral position, shaming and blaming corporations, but at the same time to include the corporations and make them feel part of the community of people working on reducing plastic pollution, avoiding disengagement and polarization. We also observed that from 2017 onwards, corporations joined the debate. Even if they did not radically change their discourse, some companies began to adopt some of the elements of the discourse of civil society.

DISCUSSION

This article described the strategies of civil society actors in their efforts to change the hegemonic discourses led by corporations. Surprisingly, and contrary to the negotiation strategies presented by the literature, civil society actors did not negotiate their moral position. On the contrary, they maintained a strong moral position, which they supported with highly affective shaming and blaming messages. Yet, to avoid disengagement and polarization, they used solidarity affects to make the adversary feel part of the group of anti–plastic pollution fighters. We call this an inclusive-dissensus strategy. We revealed the importance of affects in the engagement processes, as they enabled the inclusive-dissensus strategy. They also led to more interactivity than the less affective ones.

We contribute to the literature in three ways. Our first contribution is to the studies of deliberative democracy that take a dissensus approach to stakeholder engagement by revealing the use of affects to drive change in hegemonic discourses. Second, we show how passion can be mobilized through inclusive-dissensus strategies; this contributes to agonistic pluralism theories and also to collective action studies of affects. Third, we contribute to the debate about social media platforms operating as public spaces for stakeholder engagement and deliberation.

Deliberative Democracy and the Dissensus Perspective to Stakeholder Engagement

We first argue that, by attending to the ethical underpinnings of deliberative democracy and the emerging dissensus approaches to stakeholder engagement and deliberation (Barthold & Bloom, Reference Barthold and Bloom2020; Brand et al., Reference Brand, Blok and Verweij2020; Burchell & Cook, Reference Burchell and Cook2013a; Couch & Bernacchio, Reference Couch and Bernacchio2020; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015, Reference Dawkins2019; Fougère & Solitander, Reference Fougère and Solitander2020; Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Munro, Thanem and Pullen2020; Sorsa & Fougère, Reference Sorsa and Fougère2020; Whelan, Reference Whelan2013; Winker et al., Reference Winker, Etter and Castelló2020), we are able to challenge the rationalist orientation of previous studies of stakeholder engagement and deliberation in general. Through the ethics of disharmony (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005), we analysed engagement processes not only by reference to ideas of the good (as seen in liberal deliberative approaches to deliberation and also in most dissensus perspectives) (Couch & Bernacchio, Reference Couch and Bernacchio2020; Mouffe, Reference Mouffe and Inglis2004) but by taking into account the dynamic processes in which antagonism and violence are ineradicable and in which affects constitute the relations between actors. We therefore contribute to the reorientation of the debates of deliberative democracy by moving away from moral plurality discussions to looking at the ways in which plurality is constituted.

The rationalist approach to stakeholder engagement and deliberation has also been criticized by ethical theories, such as the ethics of care (Manning, Reference Manning1992), and the work of other feminist scholars (e.g., Gilligan, Reference Gilligan1993; Held, Reference Held1993) that points out the inseparability of nature and reason and the importance of understanding judgements as made by “embodied persons with feelings for others and for themselves” (Held, Reference Held1993: 36). By looking at the role of affects in engagement, we are able to expand the understanding of how identity is constituted in contestation between actors (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2019) even when they have different logics of governance (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2019; Sorsa & Fougère, Reference Sorsa and Fougère2020). We also shed light on the processes of recognition and acceptance of legitimacy, which are fundamental to the power that resides in difference (Rancière, Reference Rancière2006).

Attention to affects can also help us look beyond negotiation mechanisms, such as compromise and arbitration (Brand et al., Reference Brand, Blok and Verweij2020; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015, Reference Dawkins2019; Whelan, Reference Whelan2013), that are, by nature, transient and look instead at the dynamics of the construction of the hegemonic discourses. These dynamics have been explained theoretically in aspirational talk discourses that examine the paradoxes generated amongst stakeholders (Winker et al., Reference Winker, Etter and Castelló2020); however, they have not been sufficiently analysed empirically and in relation to passion. Through an empirical case, we show that these dynamics are constituted by the agentic use of moral affects coupled with solidarity affects.

We also respond to recent calls to examine how the processes of stakeholder engagement contribute to understanding conflict and pluralism in the development of discourses of responsibility in grand challenges (Burchell & Cook, Reference Burchell and Cook2013a; Ferraro, Etzion, & Gehman, Reference Ferraro, Etzion and Gehman2015; George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi, & Tihanyi, Reference George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi and Tihanyi2016). We argue that many conflicts between stakeholders and corporations seem to be not so much existential (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2015) as centred around collective identification. We contribute to this literature by proposing an agonistic framework that normalizes conflict.

The Role of Affects in Changing Hegemonic Discourses

We contribute to the understanding of passion and its role in steering changes to hegemonic discourses. We explain how identities are constituted by going beyond displacing a moral affect with one that is stronger (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005) and argue for the importance of considering moral affects in combination with solidarity affects. Inclusive dissensus shows the importance of the constitution, through affects, of the identities of opposed parties and of understanding how different affects work to compensate or enhance one another.

Our work also sheds new light on the role affects play in the dynamics of change in sustainability issues (Barberá-Tomás et al., Reference Barberá-Tomás, Castelló, De Bakker and Zietsma2019; Fan & Zietsma, Reference Fan and Zietsma2017). Whereas prior work has focussed on the role of affects in identification processes (Creed et al., Reference Creed, Hudson, Okhuysen and Smith-Crowe2014), in the social structures that accommodate reflexive and dis/embedding arguments (Ruebottom & Auster, Reference Ruebottom and Auster2018), or in framing processes (Giorgi, Reference Giorgi2017), we propose a dissensus approach that looks at the ethical-political dynamics of stakeholders in conflict. Inclusive dissensus shows that change of counter-hegemonic discourses goes beyond the resonance with moral affects defining new frames (Giorgi, Reference Giorgi2017) or the use of moral shock through images (Barberá-Tomás et al., Reference Barberá-Tomás, Castelló, De Bakker and Zietsma2019). A subtle strategy of compensation of moral and solidarity affects is needed to keep the promotion of the new moral frame while creating a sense of identification that avoids polarization.

Stakeholder Engagement Online and Social Media as New Public Agora

Our article presents the case of a vibrant online debate between civil society actors and corporations. Attending to online and offline information, we show the evolution of hegemonic discourses and some mechanisms that enabled change. Using a mixed-methods approach and triangulating different sources of information, we reveal the importance of understanding online engagements as culturally and contextually located (McCosker, Reference McCosker2014). We find that online engagements can be constructive rather than just polarized and destructive. We also show how affects can promote engagement. We therefore contribute to the understanding of the constructive nature of online stakeholder engagements and deliberation (Anderson, Reference Anderson2011; McCosker, Reference McCosker2014; Rahimi, Reference Rahimi2011; Schultz, Castelló, & Morsing, Reference Schultz, Castelló and Morsing2013), rather than the destructive nature that has been presented by previous literature (Kramer et al., Reference Kramer, Guillory and Hancock2014; Wollebæk et al., Reference Wollebæk, Karlsen, Steen-Johnsen and Enjolras2019).

We go beyond a political analysis of agonism and online dissensus (Rahimi, Reference Rahimi2011) to explain how identification is created and to highlight the role affects play in developing hegemonic discourses. We contribute to the understanding of the configuration of passion online (Marichal & Neve, Reference Marichal and Neve2020; McCosker, Reference McCosker2014). Yet, our article goes beyond the consideration of passion as comprising general affective expressions like grief and pride (McCosker, Reference McCosker2014) or moral affects like resentment (Marichal & Neve, Reference Marichal and Neve2020) to consider passion in the constitution of identity through the combination of solidarity and moral effects. We present inclusive dissensus as an agentic form of passion to deal with opposed stakeholders.

Our case contributes to the conceptualization of social media platforms as a public sphere or agora for deliberation (Bennett, Reference Bennett2003; Castells, Reference Castells2007; Papacharissi, Reference Papacharissi2010). Social media platforms have been described as a venue to “fight” against irresponsible business conduct (Lyon & Montgomery, Reference Lyon and Montgomery2013), as a catalyst for social movement ideas (Bennett, Segerberg, & Walker, Reference Bennett, Segerberg and Walker2014), and as a primary outlet for citizens wishing to express their concerns and voice their opinions (Barberá, Jost, Nagler, Tucker, & Bonneau, Reference Barberá, Jost, Nagler, Tucker and Bonneau2015; Russell Neuman, Guggenheim, Mo Jang, & Bae, Reference Russell Neuman, Guggenheim, Mo Jang and Bae2014). Our case reveals the importance of understanding the inherent conflict in the deliberation processes and the importance of managing affects to change discourses.

Limitations and Further Research

Our research has several limitations. First, there are limitations to the reproducibility of passion. There may be grand challenges in which inclusive-dissensus strategies might work; there may be others in which the logics of different parts and the importance of other factors might be so irreconcilable that agonist dialogues might never occur. Furthermore, building deliberative capacity, such as inclusive dissensus, might not be possible for less powerful stakeholders who are unable to represent their interests adequately (Ehrnström‐Fuentes, Reference Ehrnström-Fuentes2016; Soundararajan, Brown, & Wicks, Reference Soundararajan, Brown and Wicks2019). We claim that inclusive dissensus has to be understood in the context of the futility and fragility of political agreements and the temporary nature of any social discourse (Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005).