INTRODUCTION

Corporations both create and destroy value for stakeholders. Recognizing this, stakeholder theory has emerged to take into consideration the fact that companies affect the value experienced by various constituents beyond owners—groups and individuals who can affect the company or be affected by it, according to the classic definition of stakeholders by Freeman (Reference Freeman1984). Stakeholder theory has been gaining in importance and is now central to the business and society field (Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar, & de Colle, Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and de Colle2010; Jones, Reference Jones1995; Schwartz & Carroll, Reference Schwartz and Carroll2008). Indeed, some theorists are seeking to redefine the theory of the firm to suggest that it should be founded on maximizing stakeholder value (Freeman, Harrison, & Wicks, Reference Freeman, Harrison and Wicks2007; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and de Colle2010). However, the construct of stakeholder value itself is inadequately conceptualized within the literature. This paper shows how stakeholder judgments of value can be better understood through insights from prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979).

Stakeholder theory may be descriptive, describing value impacts and relations between companies and their stakeholders; normative, urging companies to take into account value impacts on all stakeholders; or instrumental, examining the connections between stakeholder value and firm performance. Nonetheless, the three standpoints as identified by Donaldson and Preston (Reference Donaldson and Preston1995) are also said to be “nested” (74) and “mutually supportive” (66). Approaches to stakeholder theory range from those that define stakeholders broadly and address their multiple interests (including social interests), to those that focus strictly on creating value for a delimited set of stakeholders for the effective management of a firm (see Phillips, Freeman, & Wicks, Reference Phillips, Freeman and Wicks2003; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and de Colle2010; Harrison, Bosse, & Phillips, Reference Harrison, Bosse and Phillips2010; Harrison & Wicks, Reference Harrison and Wicks2013). Thus, there are many perspectives on stakeholder theory, and even many variants of it (Scherer & Patzer, Reference Scherer, Patzer and Phillips2011).

Despite more than thirty years of research, stakeholder theory is still said to be in need of further development (Agle, Donaldson, Freeman, Jensen, Mitchell, & Wood, Reference Agle, Donaldson, Freeman, Jensen, Mitchell and Wood2008; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and de Colle2010; Jones & Felps, Reference Jones and Felps2013). Central to all perspectives and variants of stakeholder theory is the concept of stakeholder value, that is, the utility experienced by stakeholders as a result of corporate decisions and actions. We claim that the scope for understanding stakeholder value and thus, developing stakeholder theory, can be substantially enhanced through theories of judgment and decision-making. Of these, prospect theory is a lead contender, and particularly suited for examining stakeholder value since it fundamentally revolves around judgments of value.

Given the centrality of stakeholder value to stakeholder theory, it is surprising how neglected it has been in the literature (see also Harrison & Wicks, Reference Harrison and Wicks2013), which lacks a precise definition of stakeholder value and has given little attention to the question of how stakeholders actually perceive and judge value. There are calls to this end, however, as authors have recognized a lack of focus on stakeholders in general, and a lack of understanding of stakeholder value in particular. Wood (Reference Wood2010: 75) notes that the literature has “a theoretically strange focus on the firm rather than stakeholders and societies” and calls for research efforts to refocus towards the impacts of corporate social performance on stakeholders and society. Freeman et al. (Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and de Colle2010) suggest stakeholder value is inadequately understood and, when identifying directions for further research on stakeholder theory, include the questions of what value means for stakeholders and how we can better assess the value that a firm creates for its stakeholders (288). Other authors have called for more research to better understand stakeholder actions and responses (e.g., Laplume, Sonpar, & Litz, Reference Laplume, Sonpar and Litz2008; Rowley & Moldoveanu, Reference Rowley and Moldoveanu2003).

In short, we lack understanding of how stakeholders attribute value to the outcomes that corporate decisions and actions produce for them. Several problems arise from this. Normatively, firms are supposed to create value for stakeholders and avoid destroying value; in order to design and prioritize their activities accordingly, they must understand what that value is and how stakeholders experience it. From a theoretical perspective, it is problematic for stakeholder theory if a central concept around which the theory revolves is less than sufficiently understood and described. Finally, understanding how stakeholder judgments of value are formed is a precondition for predicting and understanding the reactions to corporate decisions and actions that such judgments may subsequently trigger.

This point about stakeholder reactions is crucial from an instrumental perspective, since most impacts of corporate social performance on corporate financial performance are mediated through stakeholder reactions: on the revenue side, almost all impacts are mediated through customer reactions, and on the cost side, the reactions of stakeholders such as regulators, capital and insurance providers, employees, suppliers, and local populations mediate the costs of doing business. Only in the case of certain direct cost impacts, such as savings in energy, raw material or waste handling costs do the bottom line impacts generally not depend on stakeholders’ reactions (Bhattacharya, Sen, & Korschun, Reference Bhattacharya, Sen and Korschun2011; Lankoski, Reference Lankoski2008). This instrumental perspective also, in turn, suggests further possible normative issues due to possible judgment misalignments. Stakeholder judgments might differ relative to those of a company’s management and across stakeholders. Management—or certain stakeholder groups (e.g., NGOs)—might also be tempted to manipulate stakeholder judgments to serve their interests at the expense of stakeholder welfare.

Our objective, in part, is to contribute to a better understanding of the causal path from corporate activities and decisions to stakeholder reactions. This path consists of several cognitively distinct stages. Barnett (Reference Barnett2014) divides them into noticing, assessing and acting. Similarly, applying the ethical decision-making model in Jones (Reference Jones1991), the process can be seen to consist of recognizing the issue, making a judgment, establishing intent and engaging in behavior. Within this causal path, we focus on the assessment/judgment stage to explore the cognitive process by which individual stakeholders form their evaluations of business decisions and activities. Thus, we do not examine how stakeholders obtain knowledge of corporate decisions and activities and when they are likely to pay attention to them, nor do we examine the conditions under which stakeholders may fail to react according to their value judgments (as distinct from situations where not taking action is consistent with the value judgment).

In sum, this article responds to calls to directly focus on stakeholders to better understand stakeholder value. Not only do we explicitly look at stakeholders, but also look at them from their standpoint in order to offer a stakeholder-centered view on stakeholder value. This view is grounded in prospect theory, a leading theory of judgment and decision-making, and within the assessment/judgment stage of models of stakeholder response to corporate actions.

The following section outlines the potential contribution of prospect theory to stakeholder theory. We then examine value in the context of stakeholder theory from several perspectives to arrive at our working definition. Next, we develop a prospect theory perspective on stakeholder judgments of value, with detailed discussion of understanding stakeholders’ reference states, including some elaborations of the basic model. The penultimate section presents an investigation of avenues to influence stakeholder judgments of value, including the normative implications. Finally, the discussion section highlights the theoretical contributions and managerial implications of the paper.

APPLYING PROSPECT THEORY TO STAKEHOLDER THEORY

Fundamental to our stakeholder-centered view is recognizing that stakeholder value has innate subjectivity and depends on the stakeholder’s judgment of that value. Judgments of value are at the core of prospect theory. Thus, consistent with the recommendation of Agle et al. (Reference Agle, Donaldson, Freeman, Jensen, Mitchell and Wood2008) to develop stakeholder theory by borrowing theory from other fields and that of Wood (Reference Wood2010) to incorporate research in other domains into the corporate social performance literature, we turn to prospect theory, a psychological theory of human judgment and decision-making first proposed by Kahneman and Tversky (Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979), to develop understanding of stakeholder judgments of value.

Prospect theory argues that the contribution of an outcome to judgment may differ markedly from the objective outcome (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1984). This is because people tend to judge value in terms of losses and gains against a reference state, not as absolute states. Moreover, there is a negative asymmetry in that losses are weighed more heavily than equally sized gains and there is diminishing sensitivity so that losses and gains occurring near the reference state affect value more than those that occur further from the reference state (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979).

Prospect theory has strong empirical support (Barberis, Reference Barberis2013; Jawahar & McLaughlin, Reference Jawahar and McLaughlin2001; Kuhberger, Reference Kuhberger1998; Starmer, Reference Starmer2000; Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1991) and has been applied to various management-related phenomena (Holmes, Bromiley, Devers, Holcomb, & McGuire, Reference Holmes, Bromiley, Devers, Holcomb and McGuire2011). However, prospect theory has not previously been applied directly to stakeholder judgments of value as we do here. While prospect theory is often associated with understanding risky choices between monetary outcomes by individuals, it can be applied to stakeholder value without compromising its authority: it is applicable even if we are dealing with judgments rather than choices (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2003), even if some considerations are related to non-monetary rather than monetary outcomes (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979), and even if situations are riskless rather than risky (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2003; Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1991).

By introducing to stakeholder judgments of value a cognitive bias known to affect human judgment, we develop a rich conceptualization of how stakeholder value judgments are formed in response to corporate decisions and actions. Our work thus complements Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Bosse and Phillips2010) who emphasize the importance of understanding stakeholders’ utility functions and note that this requires two types of knowledge: what factors are driving utility for a stakeholder, and what are the relative weightings assigned to these factors by the stakeholder. While we do not examine the utility factors and their weightings in this study, we provide a third, novel perspective to the nuanced understanding of stakeholder utility functions by adding the insights available from prospect theory that, alongside the utility factors and their weightings, determine the value experienced by stakeholders as a result of firm decisions and actions. We show how stakeholder judgments of value depend crucially on the reference state, how there are several alternative reference states that may be operative when stakeholders judge value, how the choice of reference state for stakeholders’ value judgments can occur intuitively or deliberately, and how the level of the operant reference state may change with time and may also be incorrectly perceived by stakeholders or managers. Having delineated the basic model, we elaborate in reference to category-boundary effects and neutral zones.

Our approach results in a fundamentally different way of perceiving the value of corporate actions to stakeholders, which has implications both for theory and practice. The overarching argument is that if we think about stakeholder value solely in terms of absolute outcome measures (as is currently often the case), rather than in relative terms (as losses and gains), our picture of stakeholder value will remain incomplete if not inaccurate, with potential adverse consequences for both management and stakeholders. For example, stakeholder judgments of value will often be made in relation to competing companies or products—Nike’s success in reducing instances of child labor in the supply chain could be compared to the performance of Adidas as well as its own historic performance on the issue.

While we do not aim to develop new formal theory as such, we offer a theoretical contribution that advances stakeholder theory through prospect theory by clarifying one of its central constructs and by providing a new, stakeholder-centered perspective on it. This perspective is crucial in any meaningful claims made on normative grounds of stakeholder value creation. From a more instrumental perspective, as a direct management implication of this contribution, we demonstrate how new avenues beyond those currently perceived are available for managers and others to influence stakeholder judgments of value, in turn raising further normative considerations.

VALUE IN THE CONTEXT OF STAKEHOLDER THEORY

While stakeholder value is at the core of stakeholder theory, what constitutes stakeholder value remains unclear, and this vagueness is evident throughout the literature. Thus we now turn to the construct of stakeholder value in more detail—its components, the role of subjectivity, individual vs. collective judgments, and value judgments of single vs. multiple actions—as a basis for advancing our working definition and clarifying the scope of the present paper.

Components of Stakeholder Value

Value is defined as “relative worth, utility, or importance” (Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary, n.d., emphasis added). In environmental and resource economics, several sources of value have been identified that together comprise the concept of total economic value. Essentially, this typology suggests that value can arise from actual use of a resource (use value), from its possible use in the future (option value), and from non-use-related considerations (existence value) (Braden & Kolstad, Reference Braden and Kolstad1991; Freeman, Reference Freeman1993). Within these categories there are further classifications; for example, non-use value can arise from appreciating the outcome “per se (intrinsic value), for the pleasure of others (altruism), or for future generations (bequest value)” (Plottu & Plottu, Reference Plottu and Plottu2007: 53).

Noteworthy in regard to stakeholder value is that value is conceived broadly and as having multiple components that are not necessarily visible, easily quantifiable, or reflected in monetary terms. This is in line with recent writings, which note that value has been understood too narrowly. The concept of value should be approached holistically (Santos, Reference Santos2012) and should include both economic and non-economic outcomes (Harrison & Wicks, Reference Harrison and Wicks2013) as well as both tangible and intangible outcomes (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Bosse and Phillips2010). Thus, activities by firms create (destroy) value if they positively (negatively) affect any component of value that contributes to the stakeholder’s utility. Laszlo (Reference Laszlo2008: 120), for example, writes: “Value is created when a business adds to the capital or well-being of its stakeholders. It is destroyed when a business reduces their capital or undermines their well-being.”

Subjective Versus Objective Value

Stakeholder value can be considered in subjective or objective terms. Recognizing the subjective perspective is important because, in the words of Harrison and Wicks (Reference Harrison and Wicks2013: 99), “individual differences in defining value are fundamental”. From the viewpoint of understanding stakeholder reactions, it is precisely the subjective valuations that matter and, throughout this paper, we consider stakeholder value from the subjective perspective of the stakeholder.

While subjective and objective value are likely intertwined, in that objective value, in part, drives subjective value, it is also possible that subjective valuations differ from objective ones. Stakeholders may be “mistaken” in their value judgments in that they may not know, objectively speaking, what is best for them or for the issues they care about (e.g., nutrition, an environmental resource). This raises important issues. While it might be sufficient from a purely instrumental stakeholder theory perspective to argue that what really matters are stakeholders’ subjective judgments, this is unlikely to suffice from a normative perspective. For example, there might be a requirement from a normative moral theory perspective (e.g., grounded in justice or rights) to increase objective stakeholder value even if it is judged by stakeholders to be sufficient (consider debates around living wages for employees in apparel supply chains). Equally, there might be a normative obligation to correct stakeholder misunderstandings in situations where they judge incorrectly that the value they receive from a company is below that required by law or other objectively grounded norms.

Individual Versus Collective Value Judgments

The question about stakeholder judgments of value can arise both with individual and collective stakeholders. Much of the stakeholder literature focuses on stakeholder groups and many stakeholders are indeed organization-type and thus, collective by nature (e.g., supplier firms and partner organizations, B-to-B customers, authorities, institutional investors, creditors, and the traditional media). However, many other stakeholders are clearly individuals (e.g., consumers, employees, local inhabitants, the general public, individual shareholders, and participants in social media). Although also referred to as stakeholder groups in role-based stakeholder literature, these stakeholders do not necessarily constitute psychological collectives. Thus, these stakeholder “groups” are often essentially aggregations of individuals where judgment and decision-making is still at the individual level. This is reflected in the point made by Harrison and Wicks (Reference Harrison and Wicks2013: 113) that stakeholder groups are heterogeneous in that “each stakeholder has a different utility function”, and also connects to McVea and Freeman’s (Reference McVea and Freeman2005) argument that instead of emphasizing stakeholder roles, stakeholders should be seen as real people with names and faces.

Prospect theory was developed as an individual-level theory (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Bromiley, Devers, Holcomb and McGuire2011), and in this paper we focus on those instances where stakeholders act as individuals in their judgment of stakeholder value. Significantly, while the individual level does not account for all possible instances of stakeholder value judgments, it may still account for many important instances. For example, studies show that effects on customers and employees, where individual level judgments are likely to predominate, are particularly significant for financial performance impacts (e.g., Berman, Wicks, Kotha, & Jones, Reference Berman, Wicks, Kotha and Jones1999).

Value Judgments of Single Versus Multiple Actions

Stakeholder value can refer to the value that one action of a firm creates (destroys) for a stakeholder. Stakeholders may react to isolated actions, but there can be (and often are) multiple actions of a firm that affect a particular stakeholder, who may take several such impacts into account when making an overall evaluation. Godfrey (Reference Godfrey2005) argues that stakeholders account for positive moral capital accrued through philanthropic activities and Barnett (Reference Barnett2007) suggests that they account for the historical record of the firm’s socially responsible and irresponsible acts. Thus, stakeholders often aggregate value judgments across multiple actions by any one firm, encountered during their history of interactions with the firm.

In forming an overall evaluation, the stakeholder often must make trade-offs, especially if the value impacts of the actions under consideration are conflicting. This requires commensuration, the “comparison of different entities according to a common metric” (Espeland & Stevens, Reference Espeland and Stevens1998: 313). Such commensuration happens all the time, but its form may vary (Espeland & Stevens, Reference Espeland and Stevens1998), ranging in the stakeholder context from the explicit and elaborated calculations of a sustainability ratings agency to the implicit, unconscious, even irrational “gut feeling” of some consumers. How stakeholders judge individual firm actions and how they then pool those judgments are treated here as two separate questions. The former judgment activity is our focus; the latter aggregation task is left for future research, although we do sketch some first directions for such research in the discussion section.

Our Definition of Stakeholder Value

Based on the preceding discussion, and consistent with our scope, in this paper we define stakeholder value as the subjective judgment of a stakeholder, occurring at the individual level, of the total monetary and non-monetary utility experienced as a result of some decision or action by an organization.

PROSPECT THEORY AND STAKEHOLDER JUDGMENTS OF VALUE

Prospect theory makes three key claims about judgments of value, as shown in Table 1: reference dependence, loss aversion, and diminishing sensitivity (Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1991). Reference dependence—the cornerstone of prospect theory—argues that people do not normally judge value in terms of absolute states of the outcomes, but rather in terms of gains and losses against a reference state (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979). Speaking of corporate practices, this would mean, for example, that it is not the absolute level of environmental impacts per se that determines stakeholder value (and stakeholder reactions) but how these impacts relate to the reference state employed by stakeholders.

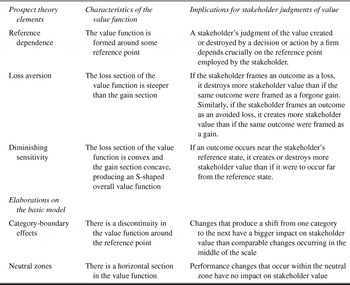

Table 1: Implications of Prospect Theory for Stakeholder Judgments of Value

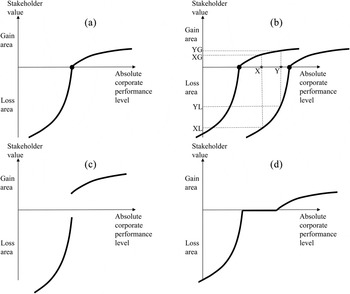

Once a reference state is chosen, framing occurs relative to this reference state and the outcome is interpreted from a loss or gain perspective (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979); however, these are not necessarily conscious processes. Notably, companies can engage in activities that objectively represent either improvements or deteriorations in performance (e.g., increase or reduction in CO2 emissions). A simple view would suggest that improvement in performance is a gain for the stakeholder and deterioration in performance is a loss. However, framing is more complicated than this and points to a more nuanced perceptual process. Depending on how the change is framed, a performance improvement can also be interpreted as an avoided loss (e.g., reduced CO2 emissions are framed as avoided environmental harm), and deterioration in performance can be interpreted as a forgone gain (e.g., increased CO2 emissions are framed as forgoing an improved environmental situation). In other words, performance improvements and deteriorations can be both interpreted from a loss frame and a gain frame, resulting in different value judgments. Thus, when the company is perceived as better than or operating “above” the reference level, it is in the gain area (see Figure 1). Stakeholder value will be judged in terms of gains: performance improvements as gains and performance deteriorations as forgone gains. By contrast, when the company is perceived as worse than or operating “below” the reference level, it is in the loss area. Then stakeholder value will be judged in terms of losses such that performance deteriorations become losses and performance improvements become avoided losses.

Figure 1: Illustrations of Stakeholder Value Functions: (a) The General Shape, (b) Comparing Judgments Against Two Reference States, (c) Category-Boundary Effect, and (d) Neutral Zone.

The second key element in prospect theory is loss aversion. Loss aversion makes the point that the value function is asymmetric, being steeper for losses than for gains. In practice, this means that “losses loom larger than gains” (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979: 279): the negative impact of losing something, for example, a stakeholder’s loss of annual philanthropic contributions from a local firm, is greater than the positive impact of gaining the same thing. Doh, Howton, Howton and Siegel (Reference Doh, Howton, Howton and Siegel2010) found that a firm’s addition to a social index did not affect shareholder wealth, but deletion from such an index did reduce shareholder wealth, which would seem to be consistent with loss aversion. Evidence suggests that this negative asymmetry is typically twofold (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2003; Starmer, Reference Starmer2000), meaning that when people judge value, they tend to be twice as sensitive to outcomes framed in terms of losses than to corresponding outcomes framed in terms of gains.

A third element in prospect theory is diminishing sensitivity. This means that the incremental value of both gains and losses decreases with their size, thus producing a value function that is concave for gains, convex for losses, and steepest at the reference point (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979). In other words, people are relatively more sensitive to changes that occur near the reference point than to changes that occur far from it. Diminishing sensitivity implies, for example, that against a reference state of a permitted amount of effluent discharges, stakeholders are likely to be more sensitive to a firm improving its modest track record than to another firm improving its strong track record further. Indeed, Doh et al. (Reference Doh, Howton, Howton and Siegel2010) found that firms with strong corporate responsibility reputations had the least to gain from addition to a social index, and also the least to lose from a deletion from a social index, as diminishing sensitivity would predict.

When prospect theory is applied to stakeholder judgments of value, this produces stakeholder value functions as shown in Figure 1a. The shape of the stakeholder value function simultaneously reflects all the three key elements of prospect theory. Firstly, the value function is formed around some reference point. Secondly, because losses are judged differently from gains, the function is asymmetrical, with the loss section steeper than the gain section. Thirdly, the S-shape of the function reflects the diminishing sensitivity of losses and gains.

Key observations about stakeholder judgments of value can be made directly from Figure 1b. First, let us examine the stakeholder value associated with a particular absolute corporate performance level X. Judged against one reference state, that performance represents a gain and produces stakeholder value XG. However, judged against an alternative reference state, the same absolute performance is a loss and produces much lower stakeholder value XL. Thus, different reference states lead to different value judgments, and more favorable judgments result from framing corporate performance outcomes as gains rather than losses.

Second, let us examine the impacts on stakeholder judgments of value associated with a particular corporate decision or activity that results in a change in corporate performance. Besides the extent of absolute change in performance, stakeholder value impacts depend on whether the change is perceived in terms of gains or losses, as well as on the distance from the reference level. (Note that in referring here to gains and losses, we also include forgone gains and avoided losses.) Because of the asymmetry between losses and gains, the same performance change has larger stakeholder value impacts when interpreted from the loss frame than when interpreted from the gain frame. Further, because of diminishing sensitivity, performance changes near the reference level have larger incremental impacts on stakeholder value than changes far from the reference level (even if the absolute impacts are larger the further you are from the reference level). Therefore, for example, as we see from Figure 1b, a corporate performance change from X to Y (such as increasing annual charitable contributions to the local community from $50,000 to $80,000) produces a large change in stakeholder value (from XL to YL) if it gets to be framed in terms of (avoided) losses near the reference point (which would be the case for someone whose reference level was $90,000), but only a small change in stakeholder value (from XG to YG) if against another reference state it gets to be interpreted in terms of gains far from the reference level (by someone whose reference point is, say, $10,000). This holds true regardless of whether the change in question represents an improvement or a deterioration in performance, and demonstrates again the crucial role of the reference state for judgments of value.

Table 1 contains a summary of our description of how the three key elements of prospect theory inform understanding of stakeholder judgments of value. (“Elaborations on the basic model” in Table 1 will be covered later.)

All in all, a prospect theory perspective on stakeholder judgments of value implies that stakeholder value depends on (i) what reference state is being employed by the stakeholders, (ii) whether the outcome occurs “above” or “below” that reference state, and (iii) how far from that reference state it occurs (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979). Understanding stakeholder judgments of value therefore fundamentally boils down to understanding the level of the stakeholder’s reference state. This is what we turn to next.

UNDERSTANDING STAKEHOLDERS’ REFERENCE STATES

To provide a rich exploration around stakeholders’ reference states, in this section we outline alternative reference states and their properties, as well as discuss the choice of a reference state and perceptions about the level of a reference state. Finally, we elaborate on the basic model by discussing how certain complexities may sometimes present themselves in connection with a reference state.

Alternative Reference States

Prospect theory allows for several possible reference states. Most intuitive is the status quo and this is often used in prospect theory research (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Bromiley, Devers, Holcomb and McGuire2011), but Tversky and Kahneman (Reference Tversky and Kahneman1991: 1046-1047) write: “Although the reference state usually corresponds to the decision maker’s current position, it can also be influenced by aspirations, expectations, norms, and social comparisons.” Reference states other than the status quo have been used in prior theoretical work (e.g., Whyte, Reference Whyte1986; Wiseman & Gomez-Mejia, Reference Wiseman and Gomez-Mejia1998) and empirical studies (e.g., Fiegenbaum & Thomas, Reference Fiegenbaum and Thomas1988; Wiseman & Catanach, Reference Wiseman and Catanach1997; Zhang, Bartol, Smith, Pfarrer, & Khanin, Reference Zhang, Bartol, Smith, Pfarrer and Khanin2008).

Reference states can arise externally or internally (Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1991). External reference states are based on comparisons to some external benchmark; internal reference states are based on some internal yardstick that the stakeholder has in mind. For example, in the context of consumer decision making, different reference prices can be identified, such as the price I paid last time, the average retail price and the price I would like to pay, corresponding to the status quo, external and internal reference states respectively (Klein & Oglethorpe, Reference Klein and Oglethorpe1987).

Status quo. In the status quo reference state, the comparison in the stakeholder’s mind is to the current performance level of the company (e.g., number of workplace accidents at the company), when judging a proposed action, or to past performance (e.g., number of workplace accidents in the previous year) when judging an action already implemented.

External comparisons. In the case of reference states based on external comparisons, the stakeholder takes an external benchmark and uses it as the reference state against which the performance of the company is compared. Such benchmarks can be taken from norms, markets, or ideals. Norms could refer to the performance level specified by regulations or, perhaps, ethical norms. From markets, the stakeholder can take the performance of other relevant firms or actors as the benchmark. This can be, for example, the performance of competitors, firms operating in the same geographical area, firms across industry sectors facing the same issue, or industry average performance. To illustrate, dramatically different stakeholder judgments of a mining company’s workplace safety performance could follow from these various possible external reference states; contrast statistics for mining accidents in high- versus low-income countries and occupational safety data for mining versus other industries (ILO, 2011). Further benchmarks are offered by widely held ideals, such as using best available technology (e.g. a production system with minimal effluent discharges), or best available practices (e.g. no use of child labor in own operations and in the supply chain). This might extend to no acceptance of trade-offs, as in the context of absolute or “protected” values (e.g. with regard to the natural environment, human or animal life, human rights, etc.) that trump all other values (Ritov & Baron, Reference Ritov and Baron1999; also see Tetlock et al. Reference Tetlock, Kristel, Elson, Lerner and Green2000 for research suggesting that even sacred values can be subject to “taboo trade-offs”, prompting moral outrage and cleansing). Interestingly, even though previous stakeholder literature has not recognized the prospect theory perspective on stakeholder valuations, it nevertheless contains examples that imply reference state thinking and external comparisons. For instance, Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Bosse and Phillips2010: 64, emphasis added) write “stakeholders are fully cooperative only when they perceive the value they get is fair in comparison to the value received by other stakeholders.” Harrison and Wicks (Reference Harrison and Wicks2013: 116, emphasis added) write “more value is created when the firm provides a level of utility to a stakeholder that goes above the norm … Consequently, the best measures allow firms to be compared to other firms in general or to firms in their industries.” Harrison and Wicks (Reference Harrison and Wicks2013) also develop the notion of stakeholders’ opportunity costs, arguing that stakeholder perceptions about the utility they receive from a firm partly depend on stakeholders’ perceived opportunity costs, that is, “whether stakeholders believe they are getting a good deal from the organization compared with what they might expect to receive through interactions with other firms that serve similar purposes” (107, emphasis added).

A particular example of reference states based on an external ideal is what we call the zero state. Here, the comparison in the mind of the stakeholder is to a hypothetical situation without the existence of the company, and hence with no stakeholder value created nor destroyed by the firm. This is analogous to Donaldson’s (Reference Donaldson1982) “state of individual production,” a hypothetical pre-agreement condition that would prompt moral agents to develop a social contract for business such that they would consent to the development of productive organizations largely as we know them today (subject to certain constraints consistent with the terms of the contract).

Internal aspirations. In addition to external benchmarks, the reference state can be based on internal aspirations of the stakeholder and the performance level of the company assessed relative to this aspired-to level. Indeed, according to Wood and Jones (Reference Wood and Jones1995), stakeholders are the source of expectations about desirable and undesirable firm performance, and they also evaluate how well firms have met these expectations. The internal aspiration can coincide with or be influenced by some external yardsticks, but also reflect other elements less obvious to the firm. For example, a stakeholder may have the aspiration that a natural area be preserved as it was in his or her childhood. Again, without speaking from a prospect theory vantage point, Harrison and Wicks (Reference Harrison and Wicks2013: 114, emphasis added) implicitly evoke internal aspirations when they argue that collecting information about stakeholder happiness “can raise the expectations of stakeholders and thus make it more likely that the firm will disappoint them.”

Features of particular reference states. Some reference states have features that are worth highlighting in the context of stakeholder judgments of value. With status quo as the reference state, improvements below the reference level and deteriorations above the reference level cannot exist in practice. The framing here is straightforward: performance improvements appear as gains and performance deteriorations appear as losses. Second, with zero state as the reference state, the impacts that the existence of a company has on its stakeholders can be inherently positive (“doing good”), such as paying wages, making available useful products, or giving money for charitable purposes. They can also be inherently negative (“doing harm”), like polluting the environment or violating human rights. All negative impacts of business are “below” the reference level and get to be interpreted from the loss frame so that “doing harm” is a loss and “doing less harm” is an avoided loss. For example, producing hazardous waste is a loss for the stakeholder; reducing this waste is an avoided loss (instead of a gain). Similarly, the positive impacts of business are “above” the reference level: “doing good” is a gain but “doing less good” is a forgone gain. For example, giving money for the local school is a gain for the stakeholder; giving less money than last year is a forgone gain.

Third, framing with regard to ideal performance is also interesting. Some ideals have a natural floor or ceiling, like those based on a zero state (for example, zero tolerance of fatalities in mining accidents), and the company cannot in practice be operating above the reference level. In these situations, all judgments are from a loss frame. Performance improvements can reduce the gap from the ideal but cannot exceed the reference level and turn outcomes into gains. With the mining accidents example, increased fatalities are clearly framed as losses, while efforts that reduce fatalities produce avoided losses. Occasionally, ideals can be exceeded; for example, with climate change, a commonly quoted ideal is carbon neutrality, but it is possible that some firms or sectors are in fact net absorbers of carbon dioxide. Moreover, ideals set by current best available technology are not fixed but may be exceeded with technological change (but the result of exceeding such an ideal is that it adjusts and shifts to the new, higher level). In these situations, framing in terms of gains is also possible.

Choice of Reference State

Human reasoning is widely seen to comprise a dual process: logical thinking and intuition (for a review of dual-process theories, see Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011; Osman, Reference Osman2004). Similarly, the choice of the reference state to be employed may be affected by deliberate or subconscious processes (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Bromiley, Devers, Holcomb and McGuire2011). One stakeholder may have carefully selected his or her reference point, while another may not even be aware of what yardstick he or she is using when judging corporate performance—or that a yardstick is being used in the first place. With subconscious choice, the operant reference state is not deliberately chosen but has emerged on the basis of environmental cues. For example, presenting information on corporate performance in terms of improvements from past levels is likely to evoke a status quo reference state. An external comparison reference state is made more salient by an announcement of a breakthrough in performance by a competitor, and an NGO campaign for a moratorium for a controversial field of business will strengthen the prominence of the zero state (e.g., no oil drilling in the Arctic wilderness). Thus, which reference state is subconsciously adopted depends on the competing messages in the environment and on their relative strength.

However, sometimes a stakeholder consciously establishes a reference point, explicitly considering what kind of performance he or she expects of a company. Such deliberate choice requires that the issue at stake is important for the stakeholder and that the stakeholder is sufficiently involved such that there is conscious goal setting with regard to the issue (Klein & Oglethorpe, Reference Klein and Oglethorpe1987). Whether this is the case depends on issue and stakeholder characteristics; for example, involvement is likely to be higher when the moral intensity of the issue is high (Jones, Reference Jones1991) or when stakeholders exhibit the characteristic of urgency (Mitchell, Agle, & Wood, Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997; Rowley & Moldoveanu, Reference Rowley and Moldoveanu2003).

A unique reference state often cannot be found across all stakeholders. For example, with regard to fur farming, the reference state for the authorities might be based on laws and regulations, but for an NGO campaigning for a moratorium on fur farming it might be the zero state. In their study of the French nuclear industry, Banerjee and Bonnefous (Reference Banerjee and Bonnefous2011) found that stakeholders could be classified in three groups: passive, supportive, and obstructive stakeholders. While the passive and supportive stakeholders might have expectations regarding sustainability, the objective of the obstructive stakeholders was not improved sustainability performance but “the cessation of all nuclear activities” (130), reflective of a “zero state” reference state. Further, stakeholder groups are not necessarily internally homogenous (Wolfe & Putler, Reference Wolfe and Putler2002) and different people within the group may employ different reference states (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Bromiley, Devers, Holcomb and McGuire2011). For example, for one customer the reference state may be the past performance level of the firm, for another the performance level of a key competitor, and for a third the performance level of the most proactive company that he or she is aware of.

Level of Relevant Reference State

Given an operant reference state, stakeholder judgments will be determined by the perceived level of that reference state at the moment of judgment. However, most reference states are dynamic so their levels can change with time. As such they can represent moving targets. The status quo is prone to change with time, as are norms, the performance levels of other companies, and stakeholders’ aspirations. Even ideals can change with time, as we noted earlier; for example, with new knowledge or changing technological possibilities. Only the zero state is absolute and stable.

Stakeholders will adapt to the changed level of the reference state and begin to use this new level as the basis for framing (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979). Indeed, the concept of a hedonic treadmill proposed by Brickman and Campbell (Reference Brickman, Campbell and Appley1971; ref. Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1984: 349-350) suggests, “rapid adaptation will cause the effects of any objective improvement to be short-lived”. For example, if the reference state is based on status quo, because of adaptation to a new status quo giving up something is framed as a loss. The value of this loss is greater than the value of the original gain in receiving the same thing (Tversky & Kahneman, Reference Tversky and Kahneman1991; see Levin, Schreiber, Lauriola, & Gaeth, Reference Levin, Schreiber, Lauriola and Gaeth2002 for an empirical validation in the context of “building up” or “scaling down” product components). Consider, for example, employment. When a company provides new employment, this is originally a gain for those who become employed as well as for the whole local community. However, if later there are layoffs, they may not be framed as forgone gains but as losses. This is because there has been adaptation to the new status quo; the jobs have become part of the endowment of the employees and the community. The negative impacts on stakeholder value of losses are greater than those of forgone gains. Thus, if adaptation has taken place, the stakeholder value impact of the layoff is greater than that of the original gain of job creation.

Knowing what is the perceived level of the relevant reference state at the moment of stakeholder value judgment is a further consideration. All reference states require some degree of information (e.g., about competitor performance, past performance, or technological possibilities, depending on the reference state). The availability and complexity of such information can vary, as can the information processing ability of different stakeholders. Hence, the perceived level of the reference state may not coincide with the true level of the reference state, or with what the firm considers to be the true level. It might also be approximate and anecdotal. For example, whereas a firm might have quantified measures of its pollution impacts, stakeholder perceptions might amount to no more than a sense that one company is a “heavy” polluter relative to another.

Elaborations on the Basic Model

We have so far discussed the general form of the stakeholder value function. However, within this general idea of an asymmetrical, s-shaped value function for a given reference state, these functions still can vary in terms of how steep the sections are, how strong the diminishing sensitivity is, or whether thresholds or other complexities are involved. We wish to bring up two possible complexities in particular: category-boundary effects and the presence of a neutral zone (see also Table 1). Note that, in contrast to the three key points in prospect theory that we presented earlier and that (according to the theory) always apply to stakeholder judgments of value, the topics we present here may sometimes apply in addition to those three.

Category-Boundary Effects. Corporate performance that crosses the reference boundary may have particular importance (Diecidue & van de Ven, Reference Diecidue and van de Ven2008). If a change in performance is enough to turn an “irresponsible” company into a “responsible” one, or vice versa, the impact on stakeholder value is likely to be disproportionately large. This is because we expect a category-boundary effect (Kahneman & Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1984): changes that produce a shift from one category to the next have a bigger impact than comparable changes occurring in the middle of the scale. For example, under a reference state based on norms, a salary increase in a firm operating in a developing country leading to compliance with the legal minimum wage produces more stakeholder value than the same salary increase in an already compliant company. The feature of diminishing sensitivity already results in the stakeholder value function being steepest around the reference point; the presence of an added category-boundary effect accentuates this by suggesting a discontinuity in the stakeholder value function around the reference point (see Figure 1c). According to Koop and Johnson (Reference Koop and Johnson2012), the category-boundary effect is especially pronounced for reference states that represent a “survival” or minimum requirement threshold.

Neutral Zones. Sometimes the reference level for a given reference state may be conceived of as a range of values rather than as a specific value (e.g., Klein & Oglethorpe, Reference Klein and Oglethorpe1987). This would imply a region of indifference, or a neutral zone about the reference state, with the consequence that performance changes that occur within the neutral zone have no impact on stakeholder value (see Figure 1d). Such an approach is in line with other applications of prospect theory to organizational situations that have essentially suggested the use of two different reference points that divide the outcomes in three groups: clear gains and serious losses, with a more neutral zone in between (March & Shapira, Reference March and Shapira1987; Shimizu, Reference Shimizu2007). For example, stakeholders may consider that companies that comply with pollution legislation without demonstrating any special leadership in that area are “OK”—not irresponsible but not particularly responsible either. Improvements or deteriorations in performance do not affect stakeholder value as long as the company still remains within this neutral area.

INFLUENCING STAKEHOLDER JUDGMENTS OF VALUE

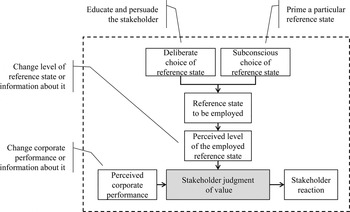

Managerial interest in stakeholder judgments of value is not limited to understanding these judgments, even if an improved understanding is already an important step forward. Managers may also wish to influence the value judgments and consequently the stakeholder reactions that these judgments trigger. It is well established that judgments of value can be changed by changing corporate performance, information about it, or both (see Figure 2). While this remains an important consideration, our analysis points to additional options, to be used alone or in various combinations, for potentially influencing stakeholder judgments.

Figure 2: Influencing Stakeholder Judgments of Value.

However, influence strategies can also raise ethical issues, with managers seen as potentially attempting to manipulate stakeholders. Equally, misalignments in judgment can exist across stakeholders. Apparel factory workers might consider a factory’s working conditions to be adequate or even good (e.g., with a reference state based on competing employers in the area), whereas NGOs active on labor rights might judge the firm’s performance to be poor (e.g., with a reference state based on global rather than local factory norms). The NGOs might also engage in strategies that attempt to manipulate stakeholders and sometimes to advance a political agenda that might not be in the best interest of the factory employees. Thus this section explores influence strategies that management and others might employ in relation to stakeholder judgments of value, while also considering normative ethical issues.

Influence Strategies for Managers—and Others

A causal path has been identified whereby perceived corporate performance gives rise to stakeholder judgments of value, which in turn trigger stakeholder reactions, as we described in the introduction and consistent with prior literature. This path is shown at the bottom of Figure 2, which also shows how our use of prospect theory can complement this understanding by incorporating the reference state that is being employed and the perceived level of the relevant reference state at the moment of judgment, both of which affect stakeholder valuations. We acknowledge that other variables besides those shown in Figure 2 are likely to influence stakeholder judgments of value. For example, Lange and Washburn (Reference Lange and Washburn2012) discuss the roles of effect undesirability, corporate culpability, and affected party noncomplicity in attributions of corporate social irresponsibility, and Bitektine (Reference Bitektine2011) explores social and cognitive influences on social judgments of organizations. Our objective in this paper, however, is to highlight specifically how prospect theory can inform the understanding of stakeholder judgments of value. We now examine the elements in Figure 2 more closely, thus outlining the new avenues for influencing stakeholder judgments of value that are opened up by our analysis.

One option for managers is to attempt to change the perceived level of the reference state that is being employed. Certain reference states (e.g., best available practices) are such that a company can affect their level through its own actions, perhaps by investing in R&D. Other reference states, however, do not lend themselves to being defined by the company (e.g., competitor performance). But even in these cases, it may still be possible to influence the perceived level of the reference state through communications. This might be, for example, by clarifying information or correcting a misunderstanding (quite possibly, management might determine that by some objective criterion, stakeholders are mistaken in their perception of the level of the reference state that they apply: for example, in what is technologically possible, what is nutritionally healthy, what is permitted by law, or what the competition is doing). As we have discussed, a change in the perceived level of the reference state can change stakeholder judgments even if the reference state stays the same. This is what Shell attempted—albeit without success—in the Brent Spar case (see e.g., Heath, Reference Heath1998). The reference state for Greenpeace and the general public was some kind of ideal state (“what is best for the environment”). Shell did not argue that the decision ought to be made against some other benchmark, but that its solution was the best for the environment; i.e., corresponding to the same reference state but at a different level to that widely perceived.

An alternative, clearly, is to attempt to influence a change in the stakeholder reference state. The susceptibility to such influence and how a switch could be brought about depend on how the reference state was originally established (Klein & Oglethorpe, Reference Klein and Oglethorpe1987). Subconsciously formed reference states emerge based on environmental cues and firms might potentially modify such cues and prime particular reference states. If the priming messages by the firm “overwrite” previous environmental cues, they can become the basis for the new subconsciously formed reference state. For example, Levin and Gaeth (Reference Levin and Gaeth1988) found that consumers evaluated beef more favorably if it was labeled “75% lean” rather than “25% fat” and observe that a major role of advertising is to frame the subsequent product experience (for a framing typology and broader discussion, see Levin, Schneider, & Gaeth, Reference Levin, Schneider and Gaeth1998; also see Levin et al., Reference Levin, Schreiber, Lauriola and Gaeth2002). With subconscious original reference states, it might also be possible to influence stakeholders to consciously choose particular reference states, through persuasion and education. When the original reference state was based on a deliberate choice, persuasion and education is likely the only route to influencing reference state choice.

In practice, a firm (or others) may not have detailed knowledge of the reference states its various stakeholders are using, how they have arrived at these reference states, and what they perceive the level of these reference states to be. Managers may well presume that stakeholders are using a status quo reference state, not least because this is likely to be a performance metric used within the firm (e.g., managers are evaluated on the basis of a year-on-year reduction in workplace accidents). The diagnosticity of reference states becomes more difficult where external comparisons are being used because of the multiple possible comparison points (although this notion is at least familiar to managers who benchmark their firm’s performance against other companies). It becomes more difficult still where the reference state is internal to the stakeholder and thereby far less accessible, though still potentially informed through stakeholder engagement.

Which reference state gets to be adopted under what circumstances is ultimately an empirical question (Whyte, Reference Whyte1986) and definitively identifying reference states is an important unresolved issue in prospect theory (Barberis, Reference Barberis2013; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Bromiley, Devers, Holcomb and McGuire2011; Köszegi & Rabin, Reference Köszegi and Rabin2006; Luce, Mellers, & Chang, Reference Luce, Mellers and Chang1993). However, while the difficulty in identifying the reference state(s) that stakeholders are using makes it hard for managers to predict in practice stakeholders’ reactions (Barberis, Reference Barberis2013; Wood & Jones, Reference Wood and Jones1995), it is less of a problem for influencing stakeholder judgments of value. Even without full knowledge of the reference states currently employed, managers can still promote particular reference states and information about their levels, so that they would increasingly become the basis for framing for stakeholders.

It should be noted that it is not only managers who can influence stakeholder judgments of value: stakeholder collectives also can influence these judgments, and so can third parties like competing firms and civil society (e.g., labor unions, NGOs). With the exception of changing actual corporate performance, the same avenues are available for these actors as for the firm. Stakeholder collectives or third parties can be a source of information and thus change an individual’s perceived level of corporate performance (e.g., an NGO brings to light labor rights problems with a company operating in a foreign country). McWilliams and Siegel (Reference McWilliams and Siegel2011: 1491) note that especially through viral media such as blogs, YouTube and Twitter, activists and journalists can easily alert consumers to “the good, the bad, and the ugly in corporate behavior”. Furthermore, stakeholder collectives or third parties can provide information that affects the perceived level of the relevant reference state (e.g., the NGO explains that a particular labor practice is forbidden according to the local regulations of that country). They can also influence the reference state that an individual employs, either through the priming messages they send (e.g., the NGO presents all information and argumentation in reference to the applicable local regulations) or purposefully educating and persuading individuals to adopt a particular reference frame (e.g., the NGO argues that compliance with local regulations is what should be expected of companies operating in foreign countries). Doh et al. (Reference Doh, Howton, Howton and Siegel2010) point out that many stakeholders rely on institutional assessments of third parties such as ratings agencies to inform their own judgments; both a reference state and information about performance with respect to that reference state are often built-in to such rankings and ratings.

Normative Implications of Misalignments in Judgment

These various strategies for influencing stakeholder judgments are inherently value-laden (in the normative sense). Firms might attempt to “correct” stakeholder judgments that they believe understate the value created or overstate the value destroyed. Perhaps, for example, stakeholders are employing an ideal or zero reference state and the company attempts to influence stakeholders to use a reference state reflecting comparisons with its competitors. Quite possibly, the company believes with good reason that it is impossible to achieve the performance level expected under judgments relative to an ideal or zero state (e.g., ecological restoration of a closed gold mine—restoring the land to its original state). Equally, however, the company might be attempting to manipulate stakeholder judgments with malign intent to reduce the possible negative reactions of stakeholders. While the outcome might be the same—a change in stakeholder judgments that is more favorable for the company—intentions matter and the former example differs categorically from the second because the company is acting in good faith.

The strategies for influence—for good or for bad—reflect differences in judgments between stakeholders and the firm and highlight the broader problem of misalignments in judgment that can arise because of different reference states employed or different perceived levels of a reference state (which we consider jointly, though arguably there may well be differences in the ease and legitimacy of attempting change in reference states versus in their perceived levels). Three base cases present themselves: 1) Stakeholder judgments and those of the company are all aligned, perhaps reflective of common reference states and agreement on the perceived level of the reference state(s); 2) Stakeholder judgments and those of the company are misaligned, with stakeholder judgments of value below those of the company; 3) Stakeholder judgments and those of the company are misaligned, with stakeholder judgments of value above those of the company. There are variants of the second and third case, where judgments differ across stakeholders, as in the earlier example of apparel workers and NGOs having different judgments of value in relation to factory working conditions.

Problems arise when there are misalignments. Many instances of business and society conflict can be framed as misalignments in stakeholder and company judgments, with stakeholders judging company value creation to be inadequate or value destruction to be excessive, consistent with the second base case. From a normative standpoint, the stakeholders can be morally right. This could be due to company management using a different and inappropriate reference state that ignores relevant moral criteria (e.g., in the mining fatalities example, management uses status quo—past performance—while human rights dictate a zero reference state that insists on no fatalities) or because management’s level of the reference state overestimates value, perhaps due to unconscious self-serving interpretations of conflicts of interest as a consequence of bounded ethicality (Bazerman & Moore, Reference Bazerman and Moore2009). Alternatively, of course, stakeholders could be morally wrong, for similar reasons.

In the third base case of stakeholder judgments of value above those of the company, either stakeholders or company management could, again, be out of alignment. However, we would speculate that this case more often occurs where stakeholders overestimate the value created, not least because the incentives are less likely to lead management to underestimate value. A typical scenario is where consumers overestimate how “good” a product is on important features such as safety or health. An interesting example comes from research finding that people are more likely to underestimate the caloric content of main dishes and to choose higher-calorie side dishes, drinks, or desserts when fast-food restaurants make health claims (e.g., Subway) compared to when they do not (e.g., McDonald’s) (Chandon & Wansink, Reference Chandon and Wansink2007). Health halos lead consumers to underestimate the calories consumed at a Subway restaurant (their perceived level of the reference state is incorrect). In such instances, an argument could be made asserting that the marketer (e.g., Subway) has a moral duty to correct the judgment of value by consumers.

DISCUSSION

We set out to examine how stakeholders judge the value they experience as a result of corporate decisions and actions, an important inquiry relevant for all variants of stakeholder theory and with profound implications for stakeholders and management. The extant literature is surprisingly silent on this topic despite calls for further research. Harrison and Wicks (Reference Harrison and Wicks2013) come closest to the idea when they call for a “stakeholder-based perspective of value” (98). They aim to contribute to measuring “how stakeholders feel about the value they receive through their interactions with the firm” (100, emphasis added), note that stakeholder preferences “come from perceptions regarding how transactions, relationships and interactions with the firm influence the utility they receive” (101, emphasis added), and define their approach “in terms of the perceived utility stakeholders receive from the firm, consistent with the idea that perception influences utility” (103). However, they do not address the role of cognitive bias in producing these “feelings and perceptions” for stakeholders, apart from mentioning it briefly as a potential problem with self-reported measures of happiness (114).

For us, this cognitive bias is much more than a source of measurement error. We argue that the value of corporate actions to stakeholders is a social and psychological construction with subjective as well as objective qualities and influenced by a cognitive bias that affects all human judgment. Thus we draw upon prospect theory—a particularly relevant and influential theory—to explain how it affects stakeholder value judgments and, by extension, possible stakeholder reactions that might result. While prospect theory itself is well established, we believe this is the first study to join prospect theory in this way with stakeholder theory, resulting in novel insights with both theoretical and managerial relevance. Indeed, focusing on stakeholders (rather than on the firm) alone represents a needed change of perspective in the literature (Wood, Reference Wood2010).

Joining prospect theory with stakeholder theory suggests that stakeholders judge value not in absolute but in relative terms: as losses and gains against a reference state that might differ across stakeholders and change over time and where losses weigh more heavily than equally sized gains. Fine-tuning this general argument, we discuss types of stakeholder reference states and how they are chosen, how perception of the level of the reference state is separate from the choice of reference state, and how certain complexities may be involved in the value function built around the reference state. We thus contribute to the building of a nuanced understanding of stakeholders’ utility functions by offering a new perspective—a perspective complementary to the view that such functions depend on the factors that drive utility for a stakeholder and the relative weightings assigned to such factors by the stakeholder (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Bosse and Phillips2010).

While our novel perspective complements (rather than replaces) previous knowledge, it still casts understanding of stakeholder value in a new light. Applying a prospect theory lens to stakeholder judgments of value results in a radically different way of perceiving the value of corporate actions for stakeholders. Seen from this perspective, value judgments depend critically on the chosen reference state, and valuations can change dramatically from those that would be expected based on absolute performance outcomes alone. Consider a construction company that complies with all relevant regulations but has an above average number of accidents on site, despite a reduction following a recent safety initiative. It could be considered responsible by stakeholders with status quo or legal compliance as the reference state, but irresponsible by those stakeholders whose reference state is the competitors’ performance or some ideal state.

Through our theorizing, we contribute to stakeholder theory by bringing theory from another field, as encouraged by Wood (Reference Wood2010). We respond to broad calls to strengthen stakeholder theory (e.g., Agle et al., Reference Agle, Donaldson, Freeman, Jensen, Mitchell and Wood2008) as well as to specific research recommendations such as those of Freeman et al. (Reference Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar and de Colle2010: 288), who ask: “What does ‘value’ mean for a particular group of stakeholders?” We do this by more adequately specifying the key construct of stakeholder value, which makes stakeholder theory conceptually more rigorous, and by developing generally applicable principles governing how stakeholder valuations are made. Integrating these insights in models of stakeholder theory can enrich those models by providing a more accurate picture of the value perceived by stakeholders and used as a basis for their reactions.

Our work also potentially contributes to prospect theory. While ample empirical evidence supports the major tenets of prospect theory, as Barberis observes (Reference Barberis2013: 178), “it is not always obvious how, exactly, to apply it… it is often unclear how to define precisely what a gain or loss is, not least because Kahneman and Tversky offered relatively little guidance on how the reference point is determined.” Holmes et al. (Reference Holmes, Bromiley, Devers, Holcomb and McGuire2011: 1082) note that prospect theory “lacks a theory of reference points” and Koop and Johnson (Reference Koop and Johnson2012) call for more studies with lifelike, real-world scenarios rather than artificial reference points. By connecting prospect theory to stakeholder theory this paper identifies a domain where alternative reference states are richly manifest and may be fruitfully investigated. Although much remains to be done, the paper thus takes some steps towards a deeper analysis of reference states within prospect theory.

Managerial Implications

Understanding stakeholder judgments of value is not only important from a theoretical perspective, it is also a critical managerial consideration to be able to better allocate resources to create value, to better communicate the value created, and to better anticipate and potentially influence stakeholder reactions to decisions and actions. According to Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Bosse and Phillips2010), “really understanding” stakeholder utility functions in a nuanced manner can produce various management benefits. To capture these benefits, managers need to be cognizant of the subjective elements that influence stakeholder judgments of value, including the cognitive bias arising as a result of operant reference states.

That said, we would not wish to understate the considerable challenges involved in identifying operant reference states and their levels as perceived by stakeholders. Our managerial implications are thus partially premised on an assumption that managers are able to discern real world usage of reference states by stakeholders. Nonetheless, one can have some idea of stakeholder reference points, especially if there is stakeholder dialogue. As Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Bosse and Phillips2010) suggest, trustful relationships with stakeholders are an important facilitator for sharing information about utility functions, and the same may hold for reference states.

It is well established within instrumental stakeholder theory that managers should look to stakeholders for guidance on which activities to prioritize in a resource-constrained environment (Jones, Reference Jones1995). Thus, if managers are choosing to allocate resources across multiple activities, decisions on resource allocation might well be different if managers consider stakeholder judgments rather than absolute performance measures, and acknowledge the possibility of reference states other than the status quo. For example, decision-making on a reduction in effluent discharges based on a year-on-year improvement by a firm with an already comparatively low level of effluents might result in an over-investment if stakeholder judgments are based on external comparison (e.g., with the firm’s competitors) rather than a status quo reference state. Equally, the firm might be under-investing in other areas, perhaps again as a result of a reliance on absolute metrics when stakeholder judgments reflect a cognitive bias. Moreover, differences across stakeholders might exacerbate the problem. Employees or brand-loyal customers, for instance, might be more willing in some sense to “fool themselves” by adopting a favorable reference state out of loyalty to the company when other stakeholders adhere to reference states that demand a higher absolute performance.

Moreover, resource allocation decisions need to be communicated to stakeholders in ways that acknowledge stakeholder judgments (e.g., communicating performance relative to peer competitors as well as year-on-year improvements). Our theorizing suggests that stakeholders may well judge firm value creation (and destruction) differently to managers. Harmonizing stakeholders’ and managers’ valuations in practice requires convergence of reference states (see Figure 1b). Managers are also more likely to be evaluated on absolute measures or relative to the status quo (e.g., reduction in CO2 emissions) and this can only heighten the disconnect between their judgments and those of stakeholders, suggesting that balanced scorecard and other evaluation frameworks should also incorporate stakeholder judgments.

In addition to creating and communicating value, managerial implications arise in the area of anticipating and influencing the type and extent of stakeholder reactions. To predict stakeholder reactions when considering an activity managers need at least to be aware of, if not specifically identify, the various reference states used by stakeholders. Adverse stakeholder reactions potentially can be avoided, or at least be less surprising when understood relative to the reference state(s) being employed.

Managers wishing to take a more active role in attempting to manage stakeholders’ value judgments and the consequent stakeholder reactions can take note of how our analysis alters knowledge of the avenues available for companies to try to influence stakeholder judgments of value. As earlier discussed, managers can support and complement actions taken to achieve changes in perceived performance by stakeholder dialogue and other actions that are designed to influence the stakeholders’ reference states as well as the perception stakeholders have about the level of the relevant reference state. Of course, managers should do this ethically—not with the intent of manipulating stakeholders—and be aware that these possibilities are equally available to others wishing to influence stakeholder judgments, including their critics. Moreover, the relationship is reciprocal—stakeholders can also make managers change their reference states.

A different set of implications for managers relates to potential misalignments of judgments. Stakeholder judgments may not be well aligned with those of corporate management, across stakeholders, and relative to absolute measures. In some ways, these misalignments are where the theoretical and managerial implications of stakeholder value judgments are most critical. In particular, misalignments of judgments of value between stakeholders and companies can lead to companies using influence strategies that might be manipulative. Company management might be using the morally “wrong” reference state where stakeholder judgments of value are lower than those of management. In instances where stakeholders overestimate value, as in the Subway example, there is a potential “clash” of instrumental and normative perspectives. From an instrumental perspective, management might prefer to keep quiet about consumers’ underestimation of their calorie consumption. From a normative perspective, it could be claimed that there is a moral obligation (grounded in consumer welfare) to correct the level of the reference state as perceived by consumers. Should managers follow the instrumental or the normative path? Perhaps this clash can be avoided through educating consumers such that they make judgments consistent with their welfare.

Research Implications

The finding that absolute outcomes are insufficient in themselves when determining stakeholder value richly informs future research by showing how the value of corporate decisions and activities to stakeholders can be more meaningfully and accurately operationalized and tested. This perspective on stakeholder judgments of value goes against conventional practice where value to stakeholders is conceived and measured in terms of absolute performance outcomes; a practice that becomes evident by looking at the corporate social performance variables in studies reviewed by Margolis and Walsh (Reference Margolis and Walsh2003) or by Wood (Reference Wood2010). It also challenges the prevailing (implicit) assumption that changes in corporate performance are judged relative to the status quo which, as we show, is only one of a number of possible reference states. Such an assumption is visible in the strong tendency to measure and report changes as improvements from past levels (e.g. in social responsibility reports).