The Federal Land Banks (FLBs) were notable in the history of American finance for several reasons. They represented the first time the federal government subsidized mortgages—in this case, agricultural mortgages—and they also inaugurated a mass market for long-term, amortizing mortgages through the use of mortgage-backed bonds. Yet the most innovative aspect of the FLBs was in the area of governmental organization. The land banks were the first of what would later become known as government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs): nominally private companies that relied on the implicit backing of the federal government for support.Footnote 1

Historians, economists, and political scientists have long studied the combined expansion of “state capacity” and formal bureaucracies in the early twentieth century; recent researchers have also described the expansion of the state through nonbureaucratic means, such as contracting out, grants-in-aid, or purely government-owned public corporations.Footnote 2 These new types of state capacity were especially important in Progressive Era attempts to reform finance—manifest in efforts to move financial power from the East to the West and South—and to share risk in seemingly uninsurable sectors.Footnote 3 Yet the design and operation of implicitly backed GSEs as a new mechanism of state power and financial reform has remained lost or obscured in the literature of the era. The story of the FLBs themselves, their financial operations and eventual collapse, has received surprisingly little scrutiny.Footnote 4

This article seeks to explain the origin and nature of the government's implicit guarantee of the FLBs and to examine the detrimental impacts of that implicit guarantee on their subsequent operations. The article argues that, while seemingly avoiding a direct federal subsidy, the implicit guarantee of the banks’ debts allowed the government to mandate a weak capital structure, caused a politicization of policies and appointments, and resulted in a dangerous intertwining of federal regulation and bank management, leading to an unstable structure that made the FLBs even more prone than most financial institutions to the ravages of the Great Depression.Footnote 5 Yet this article also tries to show how the opaque nature of the implicit guarantee meant that, despite the land banks’ eventual insolvency, the new model of the GSE could be expanded on and used by subsequent reformers.

The Origins of the Federal Land Banks and the Implicit Guarantee

Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many farmers and reformers advocated for a public system that would help fund farm mortgages. Angered by existing limitations on mortgage investment by banks and the consequent high interest rates on mortgage loans, especially in the West and the South, they believed the government had a duty to help farmers purchase land and expand production.Footnote 6 In 1913, rural congressmen and Progressive reformers made an unsuccessful attempt to incorporate a federal mortgage system into the Federal Reserve Act. They were beaten back by those, including President Woodrow Wilson, who thought mortgage loans would dilute the commercial nature of the new system. The next year, a congressional bill for a separate farm mortgage system that required the explicit support of the federal government led to a veto threat by Wilson and the bill's defeat.Footnote 7 Wilson claimed at the time that it was his “very deep conviction that it is unwise and unjustifiable to extend the credit of the Government to a single class of the community” and that this conviction “has come to me, as it were, out of fire.” Wilson, unlike some more radical Progressives, believed financial reforms had to benefit all sectors alike, and he thought the land banks, unlike the reserve banks, were an unfortunate manifestation of “class legislation” for farmers.Footnote 8 In 1916, however, facing a presidential election, waning Progressive support, and insurgent rural congressmen, Wilson and Congress agreed to a type of bank that straddled the line between explicit government support and a purely private company.

The form of the first government-sponsored enterprise was thus a compromise, which had important consequences. The final bill established twelve Federal Land Banks, similar to the Federal Reserve Banks in that each was confined to a specific region and liable for the combined debts of all the land banks. However, unlike the Federal Reserve Banks, which relied on explicit federal support, the FLBs were only declared “instrumentalities of the United States,” which was thought to embody a sort of calculated ambiguity as to the government's relationship to the land banks and their debts.Footnote 9 The government also agreed to purchase whatever shares were not bought by private individuals in an initial offering, but those government shares would gradually be retired and the system would soon be purely privately owned. With the FLBs’ initial capital, they would make mortgage loans—for up to thirty-five years—and then package these loans into tax-exempt bonds, whose sale would provide funds for more loans.Footnote 10 The tax exemption and implicit guarantee had the benefit of providing support while requiring no immediate money from the government, appealing to both Progressives and Conservatives.

In a concession to those who thought this new federal system might not work in every part of the country, the act allowed the government to license any number of joint stock land banks (JSLBs), wholly private mortgage banks that could operate in only two contiguous states and could also make mortgage loans and issue tax-exempt mortgage-backed bonds. At their height, however, these banks held only about half as many assets as the FLB system.Footnote 11

The FLBs and JSLBs were to be overseen by a Federal Farm Loan Board, which would appoint appraisers to determine the value of the land behind mortgages; appoint examiners and other officers to inspect and supervise FLBs and JSLBs; and provide general regulatory oversight of the system.Footnote 12 The act, as passed in 1916, thus created both a new industry and a new supervision of that industry—the regulated and the regulator—in one step. The radical new form of this government-supported industry was to be severely tested in the tumultuous decades that followed.

The Liabilities and Assets of the Federal Land Banks

The capital structure of the FLBs was one of the banks’ most original aspects at the time of their creation—and the one that, in retrospect, seems most calamitous. As the banks grew, the problems with their capital structure became more obvious, and it was clear that weaknesses in that structure emerged out of a reliance on the government's implicit guarantee.

The very definition of capital used by the land banks can be disputed; in fact, one could argue that the banks had no permanent capital at all. Besides the original government investment (each bank received about $750,000 from the government, for a total of $9 million), all succeeding “capital” was to come from the borrowers themselves. Each borrower was required to join a national farm loan association, which was a small cooperative group that was supposed to guarantee all mortgage loans from the FLBs to its members. Upon receipt of the money from a mortgage loan, the association would immediately give 5 percent of the mortgage money back to the FLB; in exchange, the association would receive a like amount of new stock or equity in the FLB, on which it and its cooperative membership could receive dividends. Yet even this investment was not permanent, and the 5 percent investment from each loan was to be retired and returned to the borrower if or when the borrower paid off the loan in full.Footnote 13 In this very convoluted system, loans were largely leveraged off of themselves, allowing both the government and the borrowers to avoid putting any permanent capital into the FLBs.

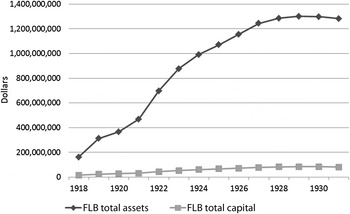

Under this plan there was also no plausible way for FLBs to raise more capital except through the production of more loans. As the initial government capital was gradually retired, even the land banks’ nominal “capital” as a proportion of all of their assets steadily dropped (see Figure 1). By 1928, at their height, the FLBs had 12.1 percent of all outstanding farm mortgages in the United States, which amounted to a total of $1.3 billion in total assets in the FLB system and put them about on par with National City Bank in terms of asset size. Yet, in that year, those assets rested on only $82 million in supposed capital, or about a 6.3 percent capital-to-asset ratio, while National City Bank had 9.4 percent in traditional capital—and the average for national banks in that year was 12.5 percent.Footnote 14 The FLBs throughout the 1920s, protected by both their joint liability and the implicit guarantee, also kept less capital than did their joint stock competitors. While JSLBs in the 1920s averaged 8.2 percent traditional capital to assets, the FLBs kept just 6.4 percent, and even this, as will be made clear below, exaggerated their actual position due to the generous accounting of the Farm Loan Board.Footnote 15

Figure 1. Federal Land Bank assets and capital, 1918–1931. Total FLB assets grew rapidly while total capital in the system remained low. (Source: Data compiled from Federal Farm Loan Board, Annual Reports 1918–1931 [Washington, D.C., 1919–1932].)

The FLBs could and did retain earnings to add to their capital, but the law limited them to charging borrowers 1 percent more than the interest on the sale of their last bonds, up to a maximum of 6 percent. This narrow margin was supposed to provide for the banks’ expenses, profits, and errors. Up until 1928, when the Farm Loan Board stopped reporting net earnings, the FLBs averaged only $5.9 million a year in reported net income, or about 0.73 percent earnings on assets a year. This was about half the ratio of national banks in this period, and, according to annual reports, up until 1928, 39.4 percent of those earnings went to dividends.Footnote 16

The very necessity of dividends in such a system is subject to question. Since the FLBs could not raise more capital through public stock offerings, dividends had little value for the banks themselves. The high proportion of earnings paid as dividends most likely reflected political pressure. Testimony before Congress by borrower-stockholders is filled with the demand for more dividends. One borrower complained at a Senate Committee on Banking and Currency hearing that the Baltimore FLB was withholding dividends after just “a few delinquents” in his cooperative association. A notable example of such complaints came when Congressman James G. Strong of Kansas protested at a hearing that his own stock, which he had received as an FLB borrower, “had not yet paid dividends.”Footnote 17 The president of the Houston FLB testified before Congress in 1931 that the demand for dividends by borrowers and politicians had seriously hurt the banks’ standing over the years. “If we had saved our dividends,” he claimed, “we would have had enough to absorb land right now. But I think we got a sort of political popularity complex, ‘Pay the dividends, pay the dividends.’ We have learned better now.”Footnote 18 Putting more dividends into capital and reserves would have helped stabilize the banks.

Given these issues with the banks’ assets and liabilities, one wonders if the FLBs were meant to survive without continuing government support. Comparing the act passed in 1916 with the act of 1914 that was defeated by Wilson's veto threat, but which contained the clause requiring direct federal support, one notices few differences. Besides slightly increasing the starting capital—from $7 million to $9 million—and changing the requirement that total mortgages be no more than twenty times capital to one that they be no more than fifteen times, the basic structure of the later act is the same.Footnote 19 There are only two explanations for this. Either the drafters believed that the requirement of government support in the first bill was largely extraneous, or they believed that the banks created by the 1916 act could confidently rely on its substitution by the implicit guarantee. Arguments made by Senator Henry Hollis of New Hampshire, the leading drafter of both bills, make the latter interpretation more credible. Hollis stated in the Senate that “it is fair in this case that the Government should put itself back of this system to a reasonable extent, as it will do if this bill passes”; further, he argued that, with a clause allowing the FLBs to become temporary depositories of government funds, the “Government under this bill will advance to a land bank money if it gets in temporary difficulty.”Footnote 20 One opponent said that the term “instrumentalities of the United States,” as contained in the act “is mere subterfuge,” stating that institutions that were “empowered to use the cash, good faith, and credit of Government are Government institutions to the extent that investors in their shares and bonds would have a moral, if not a legal right, to look to the United States for return of their money.”Footnote 21 It is possible that the very fragility of the capital structure of the banks was another indication of the implicit guarantee, demonstrating that the only plausible backstop for the banks could be the taxpayer.

Politicization of Officers and Loans

During the debate on the farm mortgage system in 1916, when some rural congressmen argued for a purely federal institution that would loan money directly to farmers, others claimed such a public institution would become politicized in both its appointments and its policies.Footnote 22 In practice, just such a politicization of the supposedly private FLBs did occur, and significantly damaged their solvency. The structure of the new enterprises and the government's implicit guarantee meant political interference was a constant at the banks.

Under the 1916 act, the government was allowed to vote for land bank directors using its original shares and thus elect the first board of directors of every FLB. The result was a political rush. Thousands of letters poured in to the Federal Farm Loan Board from politicians in every part of the country suggesting friends, colleagues, political allies, and local bankers. To organize this flood, the board created a filing system with columns for each candidate's qualifications and, more important, endorsements. For instance, the board noted that one William S. Mitchell, of Little Rock, Arkansas, had the endorsement of Little Rock's mayor, the state auditor, six members of Congress, and Senators W. F. Kirby and Joseph Robinson. With this backing, Mitchell was, of course, appointed a director of the New Orleans FLB—and after his appointment, he successfully recommended several other political friends for positions.Footnote 23 According to the first farm loan commissioner, the official executive head of the Farm Loan Board, the board “had plenty of [appointment] suggestions from Senators and Representatives, particularly the former, because we were a Bureau of the Treasury Department and Treasury appointments are regarded as ‘Senatorial Patronage.’”Footnote 24 Once appointed, the banks’ directors had the power to hire underlings at the banks, and these positions also became subject to outside political pull. A board member wrote to one FLB president, himself a political appointee, arguing that “[i]t is extremely necessary of the Farm Loan Board to have friends in Washington, and if the Senators or Congressmen give us the names of good men capable of filling any positions which may come, we are very, very, very much in favor of obliging them in this.”Footnote 25

The farm land appraisers, upon whom all agreed that safety and security of the system depended, were a particular subject of political envy and concern. Even those bank directors and presidents appointed through political favors worried that the politicization of these appointments could damage their banks. One FLB president complained—after a request from Senator Duncan Fletcher for the appointment of his brother—that “this bank is already in possession of one of Senator Fletcher's relatives as an appraiser” and asked that the board prevent having any more of “Senator Fletcher's kin forced on us.”Footnote 26 Another worried that all his current appraisers were “[m]en who have made no success of their own business” and were mere “‘hangers on’ looking for political patronage and a soft snap and no hard work.” He warned the board that he could not “assume responsibility for appraisements” made by these men.Footnote 27 These politicized appointments continued in subsequent administrations. The first Republican farm loan commissioner under President Warren Harding said that the “Farm Loan System is founded on the theory of bipartisanship,” but noted, without a hint of irony, that he did “fully intend, where vacancies occur or additional appointments are called for, to fill such vacancies and make such appointments from the Republican Party.”Footnote 28 It is difficult to know how much these political appointments damaged the stability and earnings of the FLBs, but one can take the word of these bank directors that the practice was at least somewhat detrimental.

More clearly damaging was the insistence on loans given for political purposes and on political terms. Despite having been passed with the goal of equalizing mortgage interest rates across the nation, the act itself did not specify that all banks must charge the same interest rate for all mortgages, perhaps with the understanding that the risks for different types of loans in different areas might differ. When some board members and FLB presidents balked at a uniform rate in an early meeting, Secretary of the Treasury William McAdoo told them that without a universal rate they “would find that after a little while the question would be agitated not so much by borrowers, probably, as by politicians. You have a political as well as an economic problem. . . . This is not like a private system where you are able to do as you think best. You are dealing with what has now become a public instrumentality.”Footnote 29 With this logic McAdoo convinced them to keep the rate uniform, though, as the banks complained, this made the rate too high in some areas and too low in others.Footnote 30 The board and FLBs also demonstrated a tendency to cross-subsidize smaller loans, which were more expensive to make and monitor but more clearly fulfilled the mandate of the FLB to help the small farmer. The president of the Wichita FLB noted that “the Federal land banks lose every year on every loan of 1,400 or less. . . . Notwithstanding this fact, however, we and most other Federal land banks have numerous loans below that figure.”Footnote 31 The New Orleans FLB was by all accounts the most subject to political pressure, often from the Huey Long machine; in 1930, 48 percent of its loans were for amounts below $1,000.Footnote 32

In the 1920s, as agricultural distress became a perennial political issue, the banks also received constant demands to make more loans, especially in depressed areas. In 1922, a Republican Senator from Idaho wrote to Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon to ask that he open up the spigots of funds in his state. This senator threatened Mellon by saying, “I don't want to introduce any bills in Congress or to find any fault upon the floor the Senate with the Members of the Farm Loan Board,” but he added that, “[e]very day, I am getting appeals for relief through the Federal Farm [Loan] Board, and our people out there are suffering from bank failures.” Mellon assured him that all efforts would be made to relieve the situation and then wrote to the board to expand its loans.Footnote 33 Representive James G. Strong of Kansas also wanted more loans from the FLBs, claiming, “I think I have bothered them in that respect about as much as anybody. One of the members of the board is from my State, one of them stops at my hotel, and I have a good chance to bother them.”Footnote 34 One board member later complained that there was much “political pressure . . . to loan liberally.”Footnote 35

The most obvious evidence of political pull for loans—though more representative of its danger than directly injurious—were direct loans made to members of Congress. A later report compiled by the Farm Loan Board listed every loan that went to a senator, congressman, or one of their relatives and showed hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth. Many of these individuals, including Senator “Cotton Ed” Smith of South Carolina and a few members of the prominent Bankhead family of Alabama, had multiple loans, despite restrictions on borrowing only on a primary residence. Many, again including Smith and the Bankhead family, owed thousands of dollars of delinquent payments but had not been foreclosed upon.Footnote 36

It is difficult to quantify precisely how political loans affected the earnings of the FLBs. Yet, a comparison of the delinquencies of FLB loans to those of JSLB loans, which had almost identical characteristics, demonstrates that FLB borrowers were significantly more likely to default on payments. In 1924, the rate of FLB delinquencies was almost double that of JSLBs, at 4 percent of loans to 2.2 percent, and FLB delinquencies continued to be multiple percentage points higher throughout their history. In 1932, 45 percent of FLB loans were delinquent, compared to the JSLBs’ 39 percent.Footnote 37 At least some portion of this difference can reasonably be attributed to riskier loans made by the FLBs due to political considerations.

Politicians were also concerned with controlling the other half of FLBs’ loan policies: collections. Complaints by congressmen to the Farm Loan Board about foreclosures of FLB mortgages on their constituents are far too numerous to catalog here. Many claimed, falsely, that the FLBs tended to foreclose more rapidly than any other institution and begged them to give “temporary relief” to those in trouble.Footnote 38 These complaints do seem to have had some effect on foreclosure policies. Despite having higher delinquency rates, the FLBs had a significantly lower percentage than JSLBs of real estate owned due to foreclosures, and this divergence grew as the Depression continued and foreclosures attained more political salience (see Figure 2).Footnote 39 The farm loan commissioner testified to a concerned Congress in 1931 that the banks tried not to foreclose unless “there is no reasonable hope of working out the situation” and stated that, in practice, foreclosures were “resorted to only where land has been abandoned, or has deteriorated to the extent that something must be done, or where the borrower is hopelessly insolvent.”Footnote 40

Figure 2. Real estate owned by Federal Land Banks and Joint Stock Land Banks, 1927–1931. Despite FLBs’ higher default rate, they foreclosed on fewer farms and therefore held less real estate than private mortgage lenders. (Source: Data compiled from Federal Farm Loan Board, Annual Reports 1927–1931 [Washington, D.C., 1928–1932].)

The board recognized that its policy of forbearance limited the likelihood that the banks would collect the full amount of their loans.Footnote 41 Although comparisons with the joint stock banks are not available, comparisons with contemporary insurance company mortgages are instructive in highlighting the relatively low recovery on FLB loans. Despite strict legal limitations on the percentage of farm value that could be mortgaged to FLBs (50 percent of the value of the land as decided by appraisers), the land banks consistently recovered only a small percentage of their mortgages and investments upon selling farms—much less than insurance companies recovered on comparable mortgages. In 1928, FLBs recovered only 87.3 percent of the value of their mortgages after selling foreclosed real estate, while insurance companies recovered 94.4 percent. By 1932 that figure had dropped to 66 percent for FLBs and 87.6 percent for insurance companies.Footnote 42 This comparison also seems to demonstrate that the FLB appraisers, often picked due to political influence, were likely overestimating the value of real estate and thus underestimating the banks’ likelihood of both receiving earnings and recovering from foreclosed land.

The hope that semi-independent farm mortgage banks could be kept free from politics seems not to have been borne out in practice. Instead it appears the politicization of the FLBs resulting from the government's implicit guarantee had a significant and negative effect on their operations. The political dangers also became more acute as the Depression continued.

Combining Federal Supervision and Federal Management

Another substantial factor in the troubles of the FLBs was the ambiguous delineation between the role of the Federal Farm Loan Board as supervisor and examiner of the FLBs, similar to the role of the Comptroller of the Currency in regard to national banks, and the board's role as the original controlling stockholder and then overseer of the FLBs’ operations. The implicit guarantee of the government meant the board felt it necessary to take managerial control of the banks and soon found itself concealing or distorting information that the board believed reflected poorly on its own management of the FLBs. The lack of arm's-length and independent regulation proved dangerous to the land banks’ solvency.

Although the original act demanded that the board turn control of the FLBs and the election of their directors to the new borrower-stockholders once they had acquired a majority of shares, the board was loathe to lose its powers. From early in the 1920s, the Farm Loan Board demanded that Congress allow it continuing control over these appointments. The farm loan commissioner told Congressman Henry Steagall in 1922 that these “farm-loan bonds are . . . the moral obligation of the United States,” and therefore, the “Government should have the control.” When asked by Steagall if the stockholders would ever manage the system, the commissioner stated, “The owners of the system, no.”Footnote 43 To this end an act was passed in 1923 that split bank director appointments between government and private nominees. Many borrowers later complained, however, that the elections to choose the private directors were a “whitewash,” organized to appoint pro–Farm Loan Board members, and the evidence of this is convincing. Most shareholder directors were approved by the board beforehand, received advance information about such things as the districts they would represent, ran with little to no competition, and won by overwhelming margins, despite significant objections.Footnote 44

The structure of these appointments meant the Farm Loan Board was both manager and regulator of the banks. The possibilities for conflicting loyalties were legion. From early in the system's history the board became the agent through which the FLBs sold their bonds, usually through a group of bond houses selected by the board. The board admitted it was “uncomfortable” making an ex parte contract for the banks it was supposed to supervise but felt it had little choice. One farm loan commissioner, after his term of office, testified that the board considered itself the champion of all banks in the system, required not only to “assist the banks, but to persuade, if I may use that word, the public to invest in the securities. That we tried to do.”Footnote 45 These attempts at persuasion often meant ignoring problems in the system. The first farm loan commissioner later admitted that in the first year of operation the board had published only consolidated statements of all the FLBs, because “we used the banks that had fared a little better to bolster up or conceal the bad condition of those whose business came slowly.”Footnote 46

This tendency to conceal problems with some of the banks continued throughout the banks’ history. In 1925, when the Spokane FLB was unable to pay the debts on its bonds, ten other FLBs agreed to take nonperforming farm mortgages and already foreclosed real estate off the Spokane bank's books. In return, the other land banks received euphemistically titled “Spokane Participation Certificates.” The board in its annual report claimed that the Spokane FLB's mortgages were “taken over on a basis which guarantee[s] the contributing banks against ultimate loss.”Footnote 47 Yet, soon after, an internal report concluded that “[i]t would be unworthy of a farm loan system to even give these farms away” and that “[i]t seems evident that the contributing banks can never be repaid from the sale of farms” unless there was some “miraculous change” in conditions in the region.Footnote 48 At the same time that the board's public statements stated that the Spokane FLB had $5.2 million of existing, unimpaired capital, an internal analysis estimated that the bank would lose at least $5.7 million on outstanding nonperforming mortgages and acquired real estate, meaning it was functionally insolvent.Footnote 49 The board also allowed a special accounting exception, just for the Spokane FLB, that did not charge off real estate acquired by foreclosures from earnings.Footnote 50

A similar desire of the board to protect its own charges was evident when the FLBs employed a former chair of the board to act as a “fiscal agent,” marketing the FLBs' bonds to the public, at 250 percent of his old salary. Later, a confidential investigation of the chief examiner of the board found the fiscal agent to be “juggling bonds” between different accounts to avoid reporting losses. The fiscal agent was also found to have taken a $15,000 loan from one of the bond companies with which he was negotiating to support a Montana property scheme he was speculating in, and to have asked for another $50,000 from another bond house for the same lands (he had told them they could “double” their money).Footnote 51 He resigned under duress, but the annual report stated only that the board and the FLBs had agreed that the position of fiscal agent “be discontinued.”Footnote 52

The board was so solicitous of the banks it was supervising that outside investors began to question the veracity of its reports. One wrote to Secretary Mellon, “it is commonly being said among investors that government supervision is a joke.”Footnote 53 Mellon himself complained that the board was too protective of the banks it was supposedly regulating and had not been performing the kind of “thorough, comprehensive and independent supervision” that all had hoped for.Footnote 54 Yet, as the Depression further eroded the banks’ balance sheets, the board began loosening requirements on accounting reserves and charges, allowing banks to hold acquired real estate at a price the banks’ estimated they could sell it for in a “reasonable period of time.”Footnote 55

The accounts published by the board were riddled with other misleading numbers that made the FLBs appear healthier than they actually were. In early 1931, National City Bank—which declared itself as “one of the most active distributors of Federal Land Bank Bonds”—requested a look at the board's internal books in order to evaluate the veracity of its public statements. National City Bank noted some odd things about the banks’ balance sheets in its subsequent report. One egregious example was the inclusion of $7.2 million in FLB bonds, which the banks had purchased from each other, as an asset. Loan installments over ninety days late were written off as a loss, but the principal of the mortgages from which those delinquent installments came—a total of $76.5 million—was carried at full value without reserves. These loans alone, with long-term delinquencies and little likelihood of full redemption, amounted to 6.45 percent of the value of all loans and together were almost as much as the reported total net worth of the banks, at $83.6 million. Further bad assets would push the total higher than this amount.Footnote 56 The board was also unable to furnish to National City Bank a simple sheet of expenditures and revenue of the FLBs. Despite these problems, the examiner noted that three of the banks together paid $1.9 million in dividends that year.Footnote 57

Some indication of concern within the administration about the banks’ accounts, and the government's desire to keep such concerns private, was provided during the farm loan commissioner's meeting with President Herbert Hoover in May 1930.Footnote 58 The commissioner warned the president that about 60 percent of all the FLBs’ sales of foreclosed real estate since the system's inauguration, totaling almost $20 million, were “not real”—these two words were underlined in Hoover's notes on the meeting. The commissioner was presumably referring to “purchase money mortgages” that had been given out and valued at the banks’ discretion in exchange for the foreclosed land, sometimes above 80 percent of the land's estimated value.Footnote 59 The commissioner also asked, almost a year and a half before Hoover publicly recommended that action be taken, that some holding company be created to buy up the bad mortgages. Yet the Farm Loan Board's 1930 annual report reflected none of these concerns.Footnote 60 By the end of 1931, just a month before the act recapitalizing the banks was passed, the annual report still showed a combined net worth of almost $81 million and a 6.4 percent capital-to-asset ratio. Both the total net worth and capital ratio were higher than they had been in 1928, before three years of rapid land-price collapses and rising defaults, and are therefore highly implausible.

A 1946 report by the government confirms the banks’ insolvency. This report compiled statistics on all loans made by the FLBs in the years from 1916 to 1933, and calculated the loans’ losses to the date of the report. It found that the losses amounted to 7.1 percent of the total loan value. These losses came after years of emergency farm mortgage programs, including special second mortgages provided directly by the government to delinquent FLB borrowers to maintain payments.Footnote 61 By any reasonable measure, the entire system was insolvent in 1932 when the federal government acted on its implicit guarantee and recapitalized the banks, but the misleading public reports of the Farm Loan Board, written partially to cover up its own managerial mistakes, help explain why even today this insolvency is not widely recognized.Footnote 62

The New Implicit Guarantee in Practice

The history of the federal government's supposedly implicit guarantee of the FLBs demonstrates why it continued to be involved in the banks’ operation, and why it eventually bailed them out. Yet attempts by both the government and the banks to obscure this history demonstrate why, despite their problems, the land banks would become a model for subsequent reforms.

The desire to avoid President Wilson's veto—and, after the passage of the act, his displeasure—meant that many advocates for the FLBs in their early years used a constructive ambiguity when discussing the government's relationship to the banks. One person who did this to great effect was Wilson's secretary of the treasury, and son-in-law, William McAdoo. In public hearings conducted shortly after the act's passage, McAdoo noted that the land bank bonds were “printed in the Bureau of Printing & Engraving in Washington, with the same care and skill as is exercised in printing the currency of the United States . . . [and] these are the only bonds issued by any bank or quasi-public institutions or private institutions which are given the protection of the Secret Service of the United States.”Footnote 63 More than a mere explanation of defenses against counterfeiting, McAdoo wanted to emphasize the special relationship between the banks and the government. Later, he gave the equivalent of a knowing wink to the bankers’ syndicate that marketed the first bond sale. In an open letter to the bond houses, which he allowed to be reproduced in their first circulars to investors, the secretary of the treasury wrote, “While no Governmental guarantee is added to the already ample security of these bonds, they are secured obligations of corporations operating under Federal charter with Governmental spervision [sic] on whose boards of direction the Government is represented and whose capital stock is principally owned by the Government of the United States.”Footnote 64

Both the heavy financing needs of the rest of the government during World War I and later the burdens of a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the FLBs, which claimed they were not “necessary and proper” to any enumerated function of government, made the FLB bonds temporarily unsalable; as a result, the government was forced to appropriate millions of dollars in two separate congressional acts to purchase the bonds. During the debate on the first piece of legislation, one original opponent of the banks was ungracious enough to say “I told you so” on the House floor, while Representative Carter Glass, who earlier had fought alongside Wilson against direct government support, now claimed that if the banks were “guaranteed reasonable assistance by the Government there will be a psychological change of attitude” from bond purchasers.Footnote 65 By 1921, the government had purchased over $180 million in FLB bonds—a not insignificant sum considering that the entire federal budget before the war had been barely $700 million.Footnote 66

The new Republican administrations of the 1920s, however, were less sympathetic to the implicit guarantee and began combating bond advertisements that argued for it. The new undersecretary of the treasury was horrified to find an advertisement stating that “The good faith and credit of the United States has been pledged to the Federal Land Banks.” A long series of negotiations with the major bond houses ensued, in an effort to determine how to clarify the wording.Footnote 67 A bond seller wrote to the Treasury claiming that the “real difficulty is that the relationship cannot be stated simply. . . . Furthermore, we face squarely the difficulty of altering in any respect the first [McAdoo] Circular issued by the Bankers (which was approved by the Treasury Department in every detail).”Footnote 68 The Treasury called one new bond house proposal “long and rather mealy-mouthed” and demanded a precise statement of no liability on the part of the government.Footnote 69 The bond houses claimed that they did not mind a precise statement, but stated, “What we would object to is making this statement in a way that is not precise and that might be interpreted as repudiation by us . . . [of a] statement as to the ‘moral responsibility’ of the Government.” They proposed instead a statement that the government had “no legal liability.”Footnote 70 Both sides eventually settled on a strict statement that allowed the bond houses to note in public ads both the amount of remaining capital and bonds held by the government and the particular kind of government supervision exercised by the Farm Loan Board.Footnote 71

The Treasury also began dunning the Federal Farm Loan Board to pay down its purchased bonds. The Treasury wrote to the board to say it had noticed the announcement of the sale of $60 million in new, private bonds and “hope[d] that we shall soon be able to arrive at an understanding as to how much” of that amount would pay down the government-held bonds.Footnote 72 In response to these requests, the farm loan commissioner, in a letter marked “PERSONAL AND CONFIDENTIAL,” almost threatened the Treasury by saying that any call of the bonds would “provoke a great deal of criticism and possibly undesired legislation.”Footnote 73 The Treasury responded in a threatening “PERSONAL AND CONFIDENTIAL” letter of its own, claiming that it had an “alternative”—namely, selling its existing holdings of farm loan bonds directly to the public—though it noted, with apparent satisfaction, that this “would involve some danger of competition with the [new] direct offerings of the Federal Land Banks.”Footnote 74

Congress soon found a way to keep the FLB bonds on the federal books. On March 4, 1923, the last day of the sixty-seventh Congress, it passed a general revision of the U.S. Government Life Insurance Act, which since the war had provided life insurance to soldiers and veterans. The new act allowed the trust fund for this program to invest in government obligations, as hitherto, and now in FLB bonds.Footnote 75 By the time of the act, the banks had paid down $80 million of their debt. Beginning in 1925, the Treasury would trumpet the gradual retirement of the rest of the bonds held, which were finally paid off in 1927. In actuality, all of those bonds, almost dollar for dollar, went into the “off-budget” Government Life Insurance Fund that Congress had opened to them. From then until the collapse of the FLBs in 1932, the government would continue to hold about $100 million in FLB bonds, further emphasizing its connection to the system and its implicit guarantee (see Figure 3).Footnote 76

Figure 3. Federal investment in Federal Land Bank bonds, 1918–1931. While the Treasury claimed to hold no FLB bonds after 1927, it continued to hold substantial amounts of these bonds through various trust funds. (Source: Secretary of the Treasury Annual Reports, 1918–1931 [Washington, D.C., 1919–1932]. See FRASER: https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/?id=194.)

As the Depression began to undermine the banks’ solvency, some investors became concerned that the government would not provide the necessary capital to save the FLBs, and this concern was reflected in a sharp drop in the FLBs’ bond prices. One contemporary observer listed their declining prices as one of the major dangers affecting banking in 1931.Footnote 77 In that year, however, the government would make its support much more obvious. The comptroller of the currency declared that all banks in the Federal Reserve System, national and state level, could carry FLB bonds at par instead of at their market price (now known as mark-to-market), which was the regulatory standard at the time.Footnote 78

Fearing increased defaults, President Hoover and the Federal Farm Loan Board members, in November 1931, called on Congress for a $100 million recapitalization of the banks. In public testimony, the board argued that this was not necessary for the banks’ solvency, but rather would ensure the confidence of the financial system and give the banks the ability to grant more loan extensions.Footnote 79 When this recapitalization—raised to $125 million by Congress and passed in January 1932—did not fully calm the bond market, the new Reconstruction Finance Corporation and the Federal Reserve Banks began purchasing FLB bonds on the open market.Footnote 80 In May 1933, the first year of the Roosevelt administration, Congress passed the Emergency Farm Mortgage Credit Act, which handed management of the FLBs directly to the federal government and provided a further $200 million in capital funds.Footnote 81 The FLBs would be run as explicitly nationalized banks up until their reprivatization in 1947. It is worthwhile to note here, however, that in another farm crisis, in the 1980s, the federal government would once again rescue the land banks, this time with $4 billion in congressionally appropriated funds.Footnote 82

Conclusion

The opaque nature of the FLBs and the misleading statements about their condition made by the Federal Farm Loan Board continue to obscure the system's history. Of those who write about the banks today, few explain the reasons for their insolvency in 1932, and fewer discuss their recapitalizations in 1932 and 1933. Even at the time, their condition was not widely known. This had significant ramifications for the future of the government-sponsored enterprise.

As early as 1920, vice presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt asked the Democratic Party—unsuccessfully—to include a plank in its platform that called for the “[e]nergetic and intensive development of the Farm Loan policy and the extension of the same principle to urban home builders.”Footnote 83 Just months after the passage of the 1932 act recapitalizing the FLBs, in which their true condition had been concealed from the public, Congress passed an act creating the twelve Federal Home Loan Banks, which were modeled almost exactly on the FLBs.Footnote 84 This act inaugurated the federal government's attempt to support the urban mortgage market, which was extended in 1938 when the government created what became another implicitly backed corporation: the Federal National Mortgage Association, better known as Fannie Mae.

These later GSEs often shared similar attributes with the first one, including relatively low capital ratios, presidential and congressional control of some appointments and policies, and regulators who occasionally intervened in operational decisions.Footnote 85 Therefore, despite numerous differences between the FLBs and subsequent institutions, understanding the shape and form of the first such enterprise is essential to understanding subsequent financial reforms, as well as how the federal government came to exert influence over a large part of the national economy.