Introduction

Rock art is a global phenomenon often mentioned in connection with delineating modern humans and in relation to its ability to formulate and communicate a symbolical and ontological understanding of the human condition (e.g. David & McNiven Reference David and McNiven2018; Goldhahn Reference Goldhahn2019; McDonald & Veth Reference McDonald and Veth2012; Whitley Reference Whitley2001). During the new millennium, several attempts have been unfolded which explicitly aim to link rock art to different ceremonial and ritual contexts (Goldhahn Reference Goldhahn1999; Reference Goldhahn2016; Ross & Davidson Reference Ross and Davidson2006; Whitley Reference Whitley and Insoll2011). A growing number of these studies have explored rock art in relation to gender and life-course rite de passage ceremonies, as a visual culture operating as an inter-generational medium in coming-of-age rituals (Goldhahn & Fuglestvedt Reference Goldhahn, Fuglestvedt, McDonald and Veth2012; Goldhahn et al. Reference Goldhahn, May, Maralngurra and Lee2020; Hays-Gilpin Reference Hays-Gilpin2004; Reference Hays-Gilpin, McDonald and Veth2012; May et al. Reference May, Maralngurra and Johnston2019). Most, if not all, of these studies have predominantly relied on formal scientific analyses of material culture from archaeological contexts (e.g. Taçon & Chippindale Reference Taçon, Chippindale, Chippindale and Taçon1998), while societies where rock art still plays an important role in people's social and ceremonial life-worlds have often been overlooked (cf. Brady & Taçon Reference Brady and Taçon2016; David Reference David2002; Keyser et al. Reference Keyser, Poetschat and Taylor2006; Layton Reference Layton and Whitley2001; McClearly Reference McClearly2015; Whitley et al. Reference Whitley, Loubser and Whitelaw2019; Young Reference Young1988). In this article, we build on ceremonial and engendered life-course perspectives in an attempt to present and discuss an exceptional and important case study of Samburu, a semi-nomadic pastoralist group from Marsabit County in northern Kenya; a unique case from a global perspective, where rock art is still being created.

Background and previous research

Africa is the location for some of the oldest and most fascinating rock art traditions in the world (e.g. Coulson & Campbell Reference Coulson and Campbell2001; Le Quellec Reference Le Quellec, David and McNiven2018; Smith Reference Smith, Mitchell and Lane2013). Most of these traditions have ceased or transformed. That said, at places such as Domboshava and Silozwane in Zimbabwe (Chirikure et al. Reference Chirikure, Manyanga, Ndoro and Pwiti2010; Pwiti & Mvenge Reference Pwiti, Mvenge, Pwiti and Soper1996), Tsodilo Hills in Botswana (Thebe Reference Thebe, Agnew and Bridgland2006), Kondoa-Irangi in Tanzania (Bwasiri Reference Bwasiri2011a,Reference Bwasirib), Chongoni in Malawi (Ndoro Reference Ndoro, Agnew and Bridgland2006), the Drakensberg in South Africa (Ndlovu Reference Ndlovu2009; Reference Ndlovu2011) and Chinhamapere in Mozambique (Jopela Reference Jopela2010; Reference Jopela and Berrojalbiz2015), etc., rock art is still considered essential for people's religious and ritual practices and their well-being. In Kenya, we find some of Africa's most captivating rock art areas and both pictograph and petroglyph traditions are documented (e.g. Borona & Ndiema Reference Borona and Ndiema2014; Campell et al. Reference Campell, Clottes and Coulson2007; Gramly Reference Gramly1975; Little & Borona Reference Little and Borona2014; Odak Reference Odak and Morphy1989; Reference Odak, Morwood and Hobbs1992; Russell Reference Russell2012; Russell & Kiura Reference Russell and Kiura2011). Our focus here is the Samburu, who still create rock art as an embedded thriving part of their social and cultural identity; i.e., within a specific engendered segment of their society, the warriors, known as moran or lmurran (henceforth lmurran).

Many remarkable studies uncover intriguing aspects of Samburu life-worlds, from general cultural-historical and anthropological syntheses (Holtzman Reference Holtzman1995; Pavitt Reference Pavitt1991; Spencer Reference Spencer1965) to studies of their diviners known as laibon (Fratkin Reference Fratkin2012), as well as livestock trading and herding (Konaka Reference Konaka2001; Stiles Reference Stiles1983), the economic and symbolic meaning of their visual culture (Khasandi Reference Khasandi, Mahero, Ndegwa, Mubia and Wakoko2014; Nyambura et al. Reference Nyambura, Waweru, Matheka and Nyamache2013), music and its relation to life-course rituals (Marmone Reference Marmone2020), and more. However, the Samburu's ongoing rock art tradition has seldom been the focus of any in-depth research. Natasha Chamberlain presents an exception. In 2006, she published a report of her fieldwork among the Samburu, which aimed to try to reveal how rock art imagery from ‘shelters used for meat-feasting’ corresponded to their ‘cattle brand marks’ (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain2006, 140; cf. Gramly Reference Gramly1975). Her aim was also ‘to conduct ethnographic documentation of Samburu cultural traditions associated with pastoralism and the role of the Moran, with particular reference to cattle branding, the use of rock shelters, and changing roles within society’ (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain2006, 140).

Chamberlain's study area consisted of parts of Mugie Ranch, Laikipia and the southwest Samburu District, where she conducted surveys on foot. She encountered a vast and previously unrecorded corpus of rock art, consisting of 365 figures from 21 rock-shelters (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain2006, 142). The imagery was mainly pictographs, created by using different red, black and white pigments. She also documented an engraved Boa gaming board. Chamberlain asserted that Samburu rock art was linked to lmurran warriors and its specific age-set groups:

Several of the sites contained dates, including ‘1945’, ‘1974’ and ‘1990’, which coincide with the mass initiation of the Moran age-sets of Lkimaniki, Lkiroro and Lmeoli. It may therefore be that some of the rock paintings were created to mark major events in the life of a Samburu warrior, such as entrance into his Moran age-set, or the fulfilling of his duty as a warrior and the beginning of the next stage of his life. On several occasions, the guides commented that they could identify the age-set that had drawn the motifs through the type of red ochre that had been used, as each age-set has a shade and consistency unique to them. (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain2006, 143)

After these important notes, Chamberlain presented the encountered imagery categorized as human figures, symbolic human representations (headdresses, etc.), animals (mostly livestock), texts and dates, hand- and thumbprints, circles, linear designs, crosses, brand marks, etc. Chamberlain's conclusion of her focal survey was that ‘It is now evident that the Samburu have a strong and distinct rock art tradition, using a wide range of motifs, often as symbolic representation, or to mark significant events, from initiation into an age-set, to a successful raid’ (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain2006, 156).

While Chamberlain outlines some of the main subject matter in the ongoing tradition of Samburu rock art, as well as its cultural context, she did not study this artistic tradition from an emic perspective, e.g. how this media relates to the cultural identity of lmurran and contemporary understanding of their life-worlds. The following presentation will outline our commitment to unfold such relations. Our study is based on an emic understanding of being Samburu (SLL), first-hand observations in Marsabit County during the past 16 years (EW) and extensive communications and interviews with people who created, participated and/or observed rock art being made during their time as lmurran.

The interviews we build upon were conducted with former and present lmurran in 2019 and 2020; however, our observations extend back to 2012 when EW was introduced to some rock-shelters decorated with rock paintings in the Ndoto mountains by SLL, a one-hour walk uphill from the Ngurunit settlement. In 2016, two lmurran took one of us (EW) to another rock-painting site, about one hour higher up on the Ndoto mountainside. This rock-shelter had visible paintings of three anthropomorphic figures painted with red pigment (Fig. 1). The site showed clear evidence of recent use: among other things, a fireplace, beds of branches on the ground for goats, and potsherds. The lmurran explained that the potsherds originated from one or more cooking pots frequently used by the warriors for preparing their meals. Similar sites were explored in 2019, which resulted in a mounting interest in Samburu rock art.

Figure 1. Lererin Lempate and Sania Lempate at Site 1; beyond them, three painted anthropomorphic beings depicting dancing lmurran warriors. (Photograph: Ebbe Westergren.)

After discussing these recent paintings, SLL and EW invited two rock art researchers from Linnæus University in Sweden (JG, PS) with the purpose of putting together a pilot study. The aim was to explore the cultural context of the ongoing lmurran rock art tradition during March 2020. Funding was achieved from Linnæus University to conduct oral history with former and present lmurran, which included visits to sites close to Ngurunit, and to generate basic photo documentation in 2D and 3D of the artworks. Due to the Coronavirus outbreak in 2020, only two of us were able to conduct the planned fieldwork (SLL, EW). This included organizing a workshop to explore the social and cultural context of making lmurran rock art, and preceding interviews at some rock art sites in Ngurunit and South Horr (a Samburu settlement 70 km northwest of Ngurunit). Complementary interviews were conducted over the internet by the researchers left behind in Sweden (JG, PS). Stephen Longoida Labarakwe acted as translator during the fieldwork. Our findings are the focus of the rest of this article.

Marsabit County

Samburu mainly reside in Marsabit County, but also in Samburu County. Marsabit is the largest of 49 counties in Kenya but has the lowest population (Fig. 2). According to the 2019 census, the county had a population of 459,785 people (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics 2019). To the north, Marsabit borders Ethiopia and to the west, Lake Turkana. The county has a seasonal pattern with rainfall in March/April and October/November. Rainfall differs greatly from year to year, and some years the rain fails completely. It is one of the most food-insecure districts in Kenya. In the past 50 years, the region has experienced severe droughts, resulting in livestock deaths, child malnutrition and hunger crisis (Labarakwe Reference Labarakwe and Westergren2006; Sobania Reference Sobania, Galaty and Bonte1991).

Figure 2. Africa: Kenya with Marsabit County highlighted, and with the visited sites around the Ngurunit settlement marked out (Sites 1–6). NB Site 7 is situated 70 km northwest of the Ngurunit settlement, close to South Horr. Scale is 1 km. (Map: Joakim Goldhahn.)

Marsabit County consists mainly of lowland with desert or semi-desert vegetation, including areas with bushes, small trees and seasonal rivers. The temperature often rises above 35° Celsius. Only 3 per cent of the land is arable (Labarakwe Reference Labarakwe and Westergren2006, 94). There are a few mountains, Mount Marsabit in the middle of the county, Ndoto mountains close to Ngurunit, Mount Kulal to the east of Lake Turkana and Mount Ng'iro at South Horr (Fig. 2).

The population in Marsabit County mainly consists of nomadic or semi-nomadic pastoralists who migrate from place to place in search of pasture and water. The livestock comprises cattle, goats, sheep and camels (Spencer Reference Spencer1965). In the past 30 years, the pastoralists have become more sedentary, staying longer periods in one place; there are also a few communities who live on farming to some extent, business and fishing. The settlements are generally small and scattered. About 16 different ethnic groups live in the county: Borana, Burji, Daasanach, Embu, El Molo, Gabbra, Gurreh, Konso, Luo/Muungano, Rendille, Sadamu, Sakuye, Samburu, Somali, Turkana and Waata. In 2004, c. 90 per cent of the population was illiterate (Labarakwe Reference Labarakwe and Westergren2006, 97). That has changed, however, with more of the young attending school. By his own experience, (SLL) estimates that maybe 40 per cent are illiterate today.

Samburu

Samburu culture and lmurran life-worlds are complex, and in this short article it is only possible to present a general description. The name Samburu is derived from the word Sampurr that means ‘a big skin bag’, a bag which is used to carry meat and honey (Labarakwe Reference Labarakwe and Westergren2006, 99). They are a semi-nomadic group that is closely related to other Maa speakers in the area, Ilchamus, Maasai and Yaku (Holtzman Reference Holtzman1995). The Samburu language, as well as all Maa languages, is Nilotic. According to oral history, Samburu origins are to be found in south Sudan or west Ethiopia, from where a group migrated a couple of hundred years ago (Labarakwe Reference Labarakwe and Westergren2006, 99). Others have argued that the Samburu moved from the Baringo area south of Lake Turkana in the first half of the nineteenth century and occupied areas close to Mount Kulal, Mount Ng'iro, Ndoto mountains and Marsabit (Lentoror Reference Lentoror2011; Pavitt Reference Pavitt1991; Rigano Reference Rigano2011).

Samburu life is gradually changing in pace with the rest of the world. Colonial and modern influences have been altering the Samburu life-worlds for a long time, though many of their cultural practices continue to play an essential role for their identity. For many decades, the Samburu have interrelated closely with the Rendille, a Cushite community, and intermarriages are common. Even though they are two distinct groups, the Samburu dominates in number and language. More and more of their children finish primary schools (grade 8) and start secondary schools. Some boys and girls also attend university or college, although always coming home for holidays. Today there are cell-phone networks in many places in Marsabit County, but not yet in Ngurunit and surroundings.

That said, Samburu are strongly rooted in their culture, norms, beliefs and values. Traditionally they have been pictured as a classic pastoral gerontocratic and patriarchal society (Spencer Reference Spencer1965), but recent research has underlined the power of the lmurran warrior group (Marmone Reference Marmone2020). It is a strictly gendered society, where men and women have designated obligations and responsibilities to fulfil; men's work is with herding and livestock, while women take care of children and chores at home, fetching water, gathering firewood, cooking and building huts. Polygamy is common, with senior men often having three or four wives (Holtzman Reference Holtzman1995; Spencer Reference Spencer1965). The family lives in a manyatta, a settlement with several huts, formed in a certain order for the family members. In the centre of the manyatta there is space for livestock, the most valuable possessions for Samburu. The manyatta is surrounded by a fence of thorny bushes with one or two entrances. The huts are made in a simple way to make it easy to move the whole manyatta. Wealth among Samburu is connected to the number of livestock: the more, the wealthier.

The Samburu are organized in clans and sub-clans. Each clan is led by a Senior Elder or a group of Senior Elders. Women have limited or close to no authority in the family, but gain respect and seniority after bearing children (Spencer Reference Spencer1965, 211–15, 222). They often marry young, at the age of 12 to 16 years, to a man that normally is much older. Traditionally, the girls are circumcised on the day of the wedding and are expected to give birth to several children. The marriage is the main rite de passage for women among the Samburu (Labarakwe Reference Labarakwe and Westergren2006). For men, related rites de passage are more elaborate and several, if not all, of these are linked to lmurran warriorhood (Fig. 3).

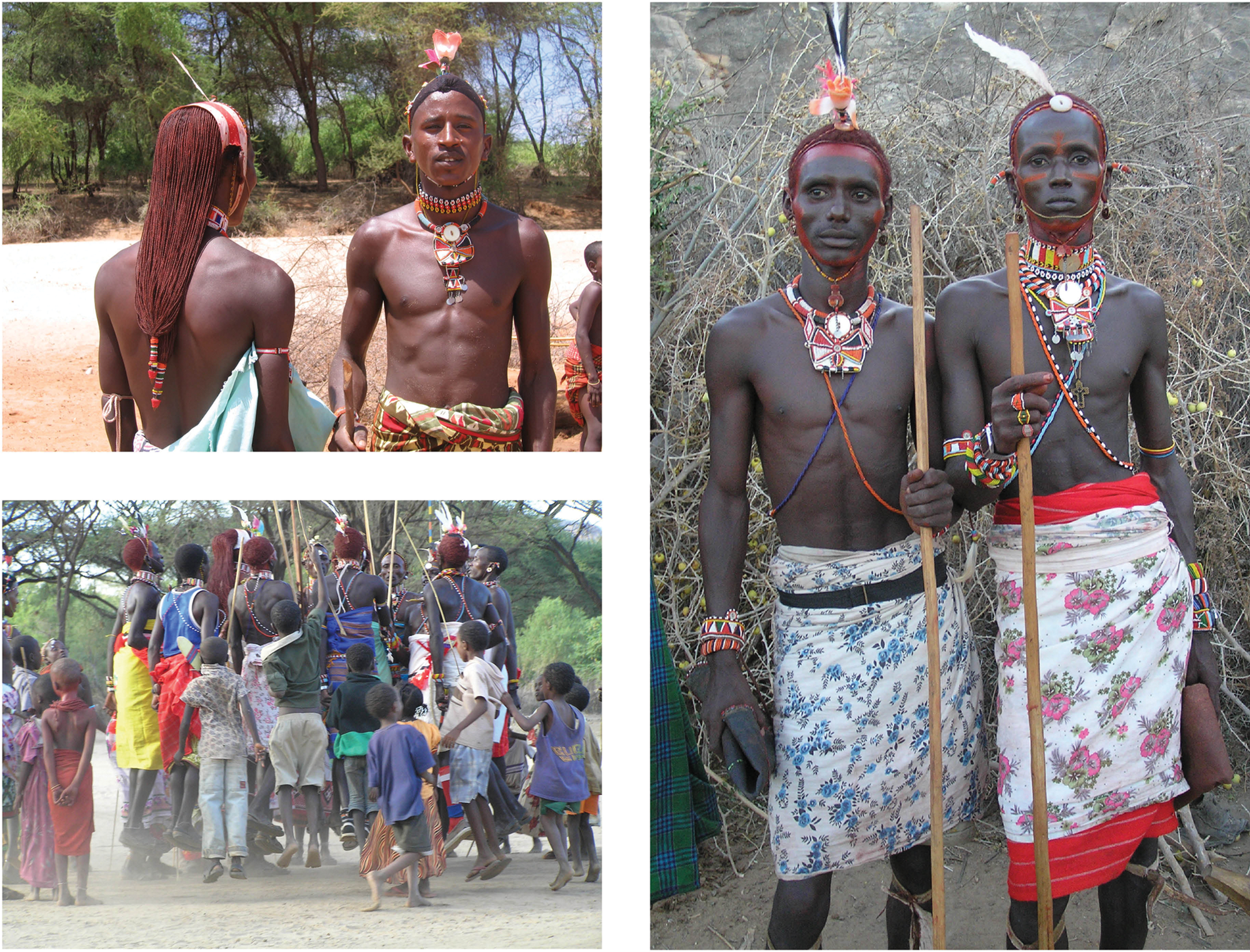

Figure 3. Lmurran warriors, with their adornments, and their dancing. (Photograph: Ebbe Westergren.)

lmurran

Men's life-course ceremonies are more comprehensive and extended in time than those for women among Samburu. Six different rite de passage ceremonies, called the lmuget, can be outlined, leading ‘up to the acquisition of full political and religious powers’ (Marmone Reference Marmone2020, 2), which is bestowed on Samburu's Senior Elders. The lmuget ceremonies are usually led by the so-called firestick elders, formed by a former lmurran age-set that served three generations before the current one (Spencer Reference Spencer1965, 82–3, 149). The first of these ceremonial circles, lmuget le nkweni or the ceremony of birds or arrows, is associated with circumcision rituals and marks the passing from childhood to warriorhood.

This ceremony is the most important event among Samburu (Labarakwe Reference Labarakwe and Westergren2006, 101). The initiation period takes about two months, when the boys are circumcised and taught life-skills by the elders. Each boy makes a bow with special arrows and is supposed to show his hunting skills on birds and small prey. They go to a shelter or cave in the bush and stay for several weeks, eat meat and other kinds of food to become stronger and prepare themselves for life as warriors. They are now allowed to smear themselves in red ochre. This ceremonial circle is only held once for a generational age-set, which means that it only takes place about every 12–15 years when new warriors are taking over from the previous warrior group (e.g. Spencer Reference Spencer1965, 80). Each generation of lmurran is given a specific name and identity, which follows them through life. The lmurran group circumcised in 2019/2020 is called Lkiseku, the previous Lkichami/Lmetili. The name of the warrior group is also the way that Samburu refers to time eras in the past, indicating which lmurran group that was holding the responsibility for protecting the community at the time. Given the predetermined role of these warrior groups, it should not come as a surprise that they are counted back far in history. Through our fieldwork, we have been able to document different lmurran groups as far back as the first half of the nineteenth century (Table 1). Previous oral history in the area, conducted by the Bridging Ages project, extend this even further back in time, to the eighteenth century (Rigano Reference Rigano2011).

Table 1. Lmurran age-set groups mentioned during our 2020 fieldwork, and the approximate calendar years when they were responsible for protecting the Samburu community. (Sources: oral history conducted during fieldwork, March 2020.)

After being initiated as a warrior, lmurran should not eat with their mothers any more, but go out in the bush and prepare their food. The lmurran move from place to place, taking care of the livestock during the hard times of the year when there is often a lack of water and grazing (Labarakwe Reference Labarakwe and Westergren2006). During this time, lmurran often camp in rock-shelters or in small caves in the mountains where they stay, eat, relax, dance and sometimes arrange feasts where meat is included. It is in these contexts that rock art is created.

Several ceremonial circles occur during the time a person is lmurrani. The second and third ceremonial circles, the lmugeti le watanta and le sikiya, or the ceremonies of roasting sticks and scent, respectively, aim to purify the newly initiated person and refurbish the authority of senior elders: ‘The smoke produced at the culmination of the ceremonies by burning leaves and branches of eight plant species has the power to “wash” (aituk) the bodies and persons of the lmurran and to eliminate the last vestiges of their “degrading” uncircumcised past’ (Marmone Reference Marmone2020, 3). The fourth ceremonial circle, lmuget le nkarna or the ceremony of the name, is an important graduation ceremony of warriors (Spencer Reference Spencer1965, 88), when a large number of Samburu families gather to celebrate the lmurran and hundreds of cattle are slaughtered. This ceremony confirms the name of the age-group and asserts them as full defenders of the Samburu community.

After approximately 12–15 years, when a lmurrani may be in his lower 30s, the warriors are replaced by a new age-set; this implies a transition from warriorhood to ‘seniorhood’. The men then go through the fifth ceremonial circle—lmuget le laiŋoni, the ceremony of the bull—when a bull is slaughtered up in the mountains. In connection to this ceremony, the lmurran start to take off their warrior insignia, shave their head and start wearing ornaments connected to their new status as Junior Elders, e.g. ivory earrings are changed to brass, and different clothing. Those who have not married before will now marry and have children. A man may have as many wives as he can afford. Having many children and several wives means status: it shows that you can afford the bride price and are blessed with children. A baby boy is a sign of continuity in the family line (Labarakwe Reference Labarakwe and Westergren2006, 102).

The Junior Elders are gradually trained for taking over as Senior Elders. To be respected as seniors, they must go through the sixth ceremonial circle lmuget lo kule o mbené, the ceremony of milk and leaves. The time for this ceremony is flexible, but usually it occurs c. 15–20 years after leaving lmurran. Senior Elders are the main advisors and decision-makers of the community. They are in charge of all religious ceremonies and make the final decisions in community matters through long conversations when the subject-matter is discussed until a consensus is reached (Labarakwe Reference Labarakwe and Westergren2006; Marmone Reference Marmone2020). Senior Elders solve disputes and punish offenders. They also decide on when marriage and circumcision ceremonies should take place.

Samburu visual culture and lmurran rock art

Following Khasandi et al. (Reference Khasandi, Mahero, Ndegwa, Mubia and Wakoko2014), the visual culture among Samburu embodies different engendered power relations. As already indicated, traditional ornaments are worn by specific age and gender groups, and this visual discourse reveals specific conceptual and ontological realities of the people who wear them (Nyambura et al. Reference Nyambura, Waweru, Matheka and Nyamache2013). Among other things, these ornaments indicate whether a person has gone through mandatory initiation ceremonies, whether s/he is married or not, whether a child of a parent has gone through specific rituals, been circumcised, and more. Material culture is used in active ways to communicate essential engendered cultural identities, in short: symbols in action (Hodder Reference Hodder1982).

The lmurran age-set and its warriorhood are unfolded through their adornments (bracelets, necklaces, headgear, earrings), specific colourful loin cloths, and by their weapons (Fig. 3). They are also easily distinguished through their long hair and their custom of smearing their hair and bodies with red pigment. A small mirror helps to give the right look. In the evenings, lmurran often gather to sing and dance (Marmone Reference Marmone2020), frequently including unmarried women from the community in these activities (Labarakwe Reference Labarakwe and Westergren2006, 101). The dancing can go on for hours and sometimes people fall into a trance.

An often neglected part of the visual culture of lmurran is the creation of rock art (Figs. 1, 5–8 below); this mainly comprises paintings, but engravings also occur. Our understanding of these artworks rests primarily on interviews with five previous lmurran that belong to four different age-sets of warriors (Table 1; Fig. 4). These are 88-year-old Nchalugi Loloibor of the Lkimaniki (c. 1946–61) and 70-year-old Ltanyaye Lempate of the Lkishili (c. 1961–16), both Senior Elders; Senior Elder and co-author, 49-year-old Stephen Longoida Labarakwe of the Lmeoli (c. 1990–2005); 29-year-old Ltaulon (Simon) Lesadala and 27-year-old Sania (James) Lempate, who both belong to the Lmetili (c. 2002/2005–2019) age-set. The latter two have just finished their obligation as warriors (NB the age of the elders is approximate). Of these, Loloibor was born in Mount Kulal, c. 200 km north of Ngurunit. He spent his time as lmurran in the Mount Kulal area. The others are from Ngurunit (Fig. 2).

Figure 4. Photographs from our 2020 workshop in Ngurunit. Below, Junior and Senior Elders, from left to right: Ltaulon (Simon) Lesadala, Sania (James) Lempate, Ltanyaye Lempate and Nchalugi Loloibor. (Photograph: Ebbe Westergren.)

Figure 5. Ltaulon Lesadala with his rather blurred and weathered handprint, Site 2. (Photograph: Ebbe Westergren.)

Figure 6. Example of rock art and names from Site 5, which were all created between our visits to the site in 2018 and 2020. (Photographs: Ebbe Westergren.)

Figure 7. Site 6 and examples of a petroglyph and pictographs. Above right: Ltaulon (Simon) Lesadala engraves a bull motif. (Photographs: Ebbe Westergren.)

Figure 8. South Horr: Lmapili Lengewa and Leramis Lengewa with the rock paintings of Lmapili's brothers that were made in 2005 when they were lmurran. NB The bull figure painted by Lpalani Lengewa is situated in the top right corner; the warriors and letters created by Ljanini Lengewa can be seen in the centre and to the left on the panel. (Photograph: Ebbe Westergren.)

During our workshop, Senior Elders Loloibor and Lempate stated that they only knew of rock art made by Samburu. They also claimed to have created hundreds of paintings during their time as lmurran, Loloibor in the Mount Kulal area and Lempate in the Ndoto mountains near Ngurunit (Fig. 2). They generally painted anthropomorphic figures and domestic animals, such as cattle, goats and sheep, but some engravings were also created using a sharp stone. According to the Senior Elders, there are hundreds of rock-shelters in the mountains with lmurran paintings. They also affirmed that their fathers and grandfathers created rock art when they were warriors. Loloibor's father belonged to the Lmarikon era (c. 1879–93) and his grandfather to Ltarigrig (c. 1865–79). The Senior Elders did not remember any names of warrior age-sets before Lkipiku, which served as warriors approximately between 1837 and 1851 (Table 1).

During our interviews, all elders demonstrated great familiarity with when, how and why lmurran rock art is created. When discussing these matters during our workshop in Ngurunit, they habitually illustrated their knowledge by drawing figures in the sand. Among other things, such sand figures were used to demonstrate stylistic variations between age-sets’ depictions of anthropomorphic figures (Fig. 4), revealed through variations in the form of the head, arms and legs. For example, more recent lmurran used more curved legs when they depicted anthropomorphic beings. Most anthropomorphic figures are depicted as if they were dancing (Figs. 1, 6 below), with female gender indicated by depiction of sexual organs and sometimes breasts. Senior Elders Loloibor and Lempate said that the anthropomorphic figures often depict the artists, the lmurran, or his preferred spouse—‘a picture of a girl he loves’.

The elders also demonstrated how to depict animals, such as elephants, bulls and livestock. Such animal figures were often drawn after encounters with real animals in the environment, showing what the artist had seen and experienced: a form of recollection of lmurran life-worlds. For example, if the artist encountered a big elephant, he could later recount this story while painting it in a shelter. Other occasions they remembered being commemorated in rock art were a wedding, people dancing, a big bull (with big horns) that had been slaughtered (e.g. Fig. 8, below), or other livestock they had consumed at the meat-feasts in the rock-shelters.

According to Senior Elders Loloibor and Lempate, rock artists did not receive any formal guidance or teaching. They learned by studying previous lmurran rock art in the shelters and by trying to replicate these images, often with an explicit aim to add their style. This explains both archaic and traditional traits in the artworks as well as recent innovations like letters, years, names, etc., which seem to become more common as illiteracy declines (also Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain2006). Older paintings were seldom or never repainted or replicated per se, probably because a lmurrani identifies himself with his age-set, which ought to distinguish themselves stylistically; but older engravings were sometimes retouched, enhanced or painted over.

Through the workshop, we also learned that gifted artists were appreciated for their skills and the aesthetic qualities of their artworks. Rivalries between artists were common, both within and between different age-sets of lmurran. Among our Senior Elders, Lempate is considered to have the upper hand, but Loloibor is also acknowledged as a good painter. Both claim to have been prolific painters, or, as they both proclaimed, ‘I have done hundreds of rock paintings’. Both of them underlined that paintings were mainly (but not always) created by the youngest or new lmurran, who like to play and fool around, while the older warriors, who had passed the fourth ceremonial circle, the ceremony of the name, often preferred to be more laid-back, taking charge of preparing food. Loloibor underlined that food is the most important. All seniors agreed that creating rock art was perceived as playful leisure, a pastime, something you would do for pleasure.

The preferred colours for the paintings are red, black and white. Specific pigments were often sought after. Loloibor, who was brought up in Mount Kulal said that before the mzungus [white people] came (c. 1945), they favoured a dark red pigment, e.g. an ochre which they also used for smearing their hair and bodies. This pigment is found in Mount Kulal; other red pigments can be obtained close to Marsabit. After the mzungus came, some lmurran used commercial paint. Today most artists buy paint in local shops, but the same pigment that is used to smear their bodies and hair is also used for paintings. The Senior Elders said that, traditionally, lmurran did not use white or yellow pigments; the light colours on the walls were achieved by using fat from animals as a pigment, which appears as white when it dries. The black pigment was achieved by using charcoal. Sania Lempate and Ltaulon Lesadala added that ash from the outside of a cooking pot was sometimes used as a pigment. As a binder, all pigments were mixed with fatty oil from slaughtered animals, such as cattle, camels, goats and sheep. The best binder comes from sheep, and a proper mixture of pigment and binders will help preserve the paintings.

Visited rock art sites

The paintings made by lmurran are generally found at higher altitudes in the mountains, well dissociated from Samburu settlements. The decorated rock-shelters or caves we visited between 2012 and 2020, in total six sites in the Ndoto mountains, are found at a distance of 45 minutes to two hours’ walk from Ngurunit, on the rocky hillsides, often in close relation to a freshwater source (Fig. 2). Two rock art sites have more than 20 paintings; only one has engravings. Some paintings that were visible in 2012 can no longer be detected, other paintings have been added, which shows that this is an ongoing tradition. One site with several paintings was also visited on the side of Ng'iro mountain, just over an hour's walk from the settlement of South Horr. Here we know the names of the painters and what year they were made. The elders mentioned many more sites with artworks in the mountains, so it is clear that this corpus only comprises a fragment of sites with Samburu rock art (see Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain2006).

Site 1, Ngurunit, 2 March 2016

This is one of the first rock-shelters we visited after the rock art had sparked our interest. The site is situated two hours’ walk from Ngurunit up in the Ndoto mountains. It was visited in company with two Junior Elders, Sania Lempate and Lererin Lempate. There was a fireplace in the shelter with remains of potsherds and beds of branches for goats. Three anthropomorphic figures were painted on the wall with red pigment (Fig. 1). Sania Lempate's interpretation of the scene is that it depicts three dancing warriors.

Site 2, Ngurunit, 30 March 2019

The site is situated 45 minutes’ walk from Ngurunit on a hillside. We visited the site in company with two Junior Elders, Sania Lempate and Ltaulon Lesadala, about a year after they passed the ceremony of the bull. Several huge stone blocks on the ground provide small shelters and caverns. During our visit, we found two wooden sticks in the shelter, close to the fireplace, used for stirring a pot. On top of the boulders, there are natural holes in the rock, which sometimes hold water. You have to know where they are and be fit to climb the rock to find them. The lmurran use these water sources for washing themselves and their clothes.

Both Junior Elders had stayed at this site many times when they were lmurran. We found a large number of artworks depicting anthropomorphic figures, handprints and an elephant. We also recorded Samburu names. Red pigment was used for these figures. There is also a bull painted in white outside a boma (an enclosed area made of dried wood to keep out late-night predators) and a black anthropomorphic figure. Several faded and vanishing paintings were also noted, as well as letters and names of lmurrani, and specific age-sets (Fig. 5). According to Sania Lempate and Ltaulon Lesadala, the human figures are males and dancing, and all of them were created quite recently.

Sania Lempate and Lesadala stated that there are many shelters in the vicinity with rock art, many that were used during their time as lmurran, i.e. the Lmetili era between 2002/2005 and 2019 (Table 1). They said that everybody knows about the rock art, but not everybody bothers or talks about it as important. Lmurran always go to the rock-shelters directly after the circumcision ceremonies, at the start of a new lmurran age-set group. After that, this and other decorated shelters were used on a regular or irregular basis, as a camp, during their nomadic life as lmurran. The warriors stay overnight in the rock-shelters, meet and talk to each other, relax, sleep and take care of goats and cattle. They prefer to stay in such shelters, partly because these are cool and give some protection against dangerous animals. They cook food and eat; sometimes they slaughter a goat, bull, or other livestock and have a feast.

The rock paintings they saw being made were created as a leisure activity, as relaxation, often in the evening when some other lmurran prepared food. Those warriors who had an interest, or those who were skilled artists, created rock art. Images were also created partially to make a mark for future visits, but also for the preceding age-sets of warriors to contemplate and admire: as a commemoration of past, present and future lmurran cultural identity. A finger was used to make the art. During our visit, Lesadala showed a rather blurred handprint on the rock that he had created during his time as lmurrani (Fig. 5), but he was not particularly proud of it: ‘I'm not a good painter’, he commented.

Site 3, Ngurunit, 30 March 2019

The same day we visited another shelter, situated only 20 minutes’ walk from the first. Sania Lempate and Ltaulon Lesadala said that several paintings had been created in this shelter, but, because of exposure to weather and wind, as well as smoke and soot from the fire below the panel, almost all of these images were now undetectable. This shelter is used on a regular basis. Some red ochre lines and dots were all that could be seen, indicating the paintings that were made a few years ago.

Site 4, Ngurunit, 12 March 2020

This site is situated on a rocky hillside north of the Lepiri river, about 45 minutes’ walk from Ngurunit. It was visited with Ltaulon Lesadala and Sania Lempate. It is a rock-shelter where they often camped. There is a recent fireplace and the wall above the fireplace is pitch black.

Only one painting was clearly visible, a small white animal, probably a bovid. There were also fragmentary traces of red pigments on the wall. Ltaulon Lesadala and Sania Lempate said there had been several paintings close to the fireplace, but they had now been covered by a black layer of soot.

Site 5, Ngurunit, 12 March 2020

This site is situated beside a natural water pool, an hour's walk uphill from Ngurunit. During our visit in 2012, a clear anthropomorphic figure painted with red pigment was documented. At that time, there were also traces of other paintings. During our visit to the site in 2018, there were no visible paintings at all in the shelter; all had vanished. During our latest visit in 2020, new images were noticed. According to Labarakwe, these images were made by lmurran in 2019, some time before they went through the ceremony of the bull to become Junior Elders. Three figures of women holding hands are painted with red pigments, lines under the figures probably indicating the ground. On a flat rock beside the pool, several Samburu names are written, including Lolmuran (Fig. 6).

Site 6, Ngurunit, 13 March 2020

This site consists of a huge boulder which creates several shelters (Fig. 7). It is situated about 45 minutes’ walk from Ngurunit and was visited with Ltaulon Lesadala and Sania Lempate. It is only 20–30 minutes’ walk from Site 2. The Junior Elders said that this site has not been used for some time; it may have been used by the age-set of Lkiroro (c. 1976–91) and/or Lkichili (c. 1961–76). On one side of the boulder is a fireplace that seemed to have been used recently, and there was a package from World Food, a United Nations aid programme distributing food in Kenya and other countries.

The rock art is found on the boulder on the opposite side of the fireplace. To the right is an elephant painted with red pigment, as well as an engraved elephant and camel. To the left is a large engraved elephant and, close to each other, a black bull, a red elephant, a red rhino, and below, five anthropomorphic figures: two black (male and female), two red (male and female) and a single human (male), made using red pigment (Fig. 7). On the boulder, you can also see a person taking care of a cow (in red), two single humans (black), one male and one female holding hands (red) and a camel painted with red pigment. When we visited this site, Lesadala made a new engraving of a big bull using a sharp stone. The purpose was to demonstrate how the engravings were created (Fig. 7).

In discussion by the shelter, Lesadala and Lempate said that the rhino talks about a time when big game was common in the area. Wild animals such as giraffes, buffaloes, lions and rhinos disappeared in the 1970s, because of poaching. Lesadala and Lempate mentioned that rock paintings are made as a memory, a reminder, ‘I was here’. It happens that they revisit the shelters they stayed at as lmurran, to tell stories about what happened when they were younger. They were sure that the new age-set that are circumcised and initiated as lmurran in 2020, Lkiseku, will continue to use this and other shelters in the coming years and make new paintings, which underlines the importance of rock art as an inter-generational medium among Samburu warriors.

Site 7, South Horr, Ng'iro mountains, 15 and 17 March 2020

This site is situated about 70 minutes’ walk uphill from the Sumurai settlement, South Horr, on the Ng'iro Mountain. Not far from the settlement, two Boa gaming boards (Ntotoi in Samburu), engraved in stones, were noticed. The rock art site was visited together with two Junior Elders, 26-year-old Lmapili Lengewa and 30-year-old Leramis Lengewa. According to Lmapili Lengewa, this shelter has been used for generations by lmurran, at least five age-sets, mainly for staying while herding goats. He knows about activities in this shelter from Lkimanike (c. 1948–61), which was the age-set of Lengewa's father, and onwards (see Table 1). The main camping place is situated on one side of the rock, with the rock paintings on the other. Lengewa's father Lemoriate Lengewa lived in this shelter most of his time as a lmurrani, and later, during Lkichili (c. 1961–76), he moved down from the mountain area to South Horr, where the family is now living.

There are at least 10 anthropomorphic figures painted with red pigment on the main panel (Fig. 8): some male figures/lmurran holding a spear in front of them, and one of these is holding hands with a female-attributed figure. The letters ‘Lm’ and ‘M’ can also be read on the wall. To the right is a bull and below it an anthropomorphic figure, both painted in red pigment.

According to Lmapili Lengewa, all the paintings on the side of the rock were created in 2005, on several occasions, just after the circumcision ceremony when the new Lmetili age-set had been initiated (Table 1). The rock art was created by two older brothers of Lmapili Lengewa, Lpalani and Lejinai, who at the time were around 20 and 16 years old, respectively. Lmapili Lengewa was present when the paintings were created, although he was a little too young at the time to be a lmurran (about 13 years old). The brothers learned from studying older paintings, but their imageries were made to commemorate what they had experienced as newly inducted lmurran. The bull figure, for example, depicts a bull they had slaughtered and eaten (Fig. 8). At the time there were about five or six people in the shelter; most of them focused on preparing the food, while the two brothers created rock art. The red pigment had been bought in a shop in South Horr and was mixed with fat from the animals they had slaughtered and eaten, in this case the depicted bull. Lmapili Lengewa stated that his brothers still refer to this site as ‘their’ rock-shelter.

Two days after the visit to the shelter, one of the rock art artists, Lejinai Lengewa, was interviewed at his home. He confirmed his younger brothers’ story. He and his older brother Lpalani created all these paintings in 2005, sometime after their circumcision and initiation to become warriors. They created the paintings on several occasions, but all in the same year. Lejinai Lengewa painted the three lmurran with spears and his brother made the bull and the lmurran portrayed below (Fig. 8). Lejinai Lengewa confirmed that the paintings were created for leisure. It did not take long to make them, in total maybe an hour or two. Lmapili Lengewa said that the two brothers competed to be the best painter and that Lpalini was the better one. Lejinai Lengewa did not fully agree with this description, but maintained that he created the images because he enjoyed painting. Lejinai revealed that ‘Lm’ on the rock means Lmetili, the age-set he belongs to, while ‘M’ stands for Meoli (Lmeoli), the previous age group (Table 1). The two brothers made many paintings in several rock-shelters during their time as lmurran. Lejinai Lengewa mentioned at least two more shelters in the vicinity where he painted, which, unfortunately, we did not have time to visit. They also assured us that there are several more rock-shelters with paintings and engravings in the mountains on both sides of South Horr. They even showed photographs of some of them, with geometrical engravings in one shelter and the years 2002, 2012, 2015 and 2020 in others.

Discussion and conclusion

Lmurran life-worlds encourage staying away from the main settlements during their warriorhood, moving from place to place. They care for themselves and their families’ livestock, and the protection of the community. Because of the harsh area and high temperature, they look for cool shelters with shade which are easy to defend against wild animals. These shelters are often found in the mountains or on hillsides, where large boulders or rock formations form small caves and rock-shelters; a site close to a water source is preferable. These rock-shelters are regularly used by lmurran in their nomadic lifestyle, to stay overnight, or sometimes several weeks in the same shelter. There is always a fireplace and often space for goats and/or cattle. Broken pots can also be found, along with small bags that have contained food ingredients, a stick to stir the pot, branches for the goats, beds or wooden pillows for the warriors, and other traces of recent activities. Some of the rock-shelters have been used for generations, others have been abandoned, for one reason or another. Many, but not all, display rock art.

Our fieldwork has revealed solid evidence for a strong ongoing rock art tradition among lmurran of Samburu, which was also underlined c. 15 years ago in a study conducted by Chamberlain (Reference Chamberlain2006). This is truly unique from a global perspective, since most rock art traditions have ceased or transformed (e.g. David & McNiven Reference David and McNiven2018; McDonald & Veth Reference McDonald and Veth2012). However, the importance of rock art for indigenous people world-wide should not be ignored; it constitutes an essential part of their cultural identity and practices, as well as their well-being (e.g. Brady & Taçon Reference Brady and Taçon2016; Keyser et al. Reference Keyser, Poetschat and Taylor2006; Taçon Reference Taçon2019; Taçon & Baker Reference Taçon and Baker2019). Among the Samburu, both Senior and Junior Elders as well as contemporary lmurran claim to have created rock art, and there is nothing to suggest that this cultural practice will come to an end soon.

Through our interviews and earlier oral history in the area, this tradition can be followed back to the nineteenth century, but it is probably older (Table 1). Contrary to Chamberlain (Reference Chamberlain2006, 143), who suggested that lmurran rock art was made to ‘mark significant events, from initiation into an age-set, to a successful raid’ (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain2006, 156), our findings suggest that these artworks were created predominantly as a mundane leisure activity (cf. Layton Reference Layton and Whitley2001; Mulvaney Reference Mulvaney1996). Both Senior and Junior Elders among Samburu play down the importance of rock art, claiming that it was mainly made by young warriors as a pastime. Instead, the elders emphasized that it was the lmurran meat-feasts after circumcision, and also meals, that were of significance and importance. Despite being an ongoing tradition, the creation of rock art is given less attention in the public domain ruled by Senior Elders.

That said, this does not automatically lead us to suggest that lmurran rock art should be interpreted as ‘l'art pour l'art’ [art for art's sake] (e.g. Halverson Reference Halverson1987), for as Robert Layton (Reference Layton and Whitley2001, 312) has argued, ‘Even secular art, however, resonates with a culture's values’. Part of the downplaying of the significance of the rock art might be explained in that lmurran constitutes a passing life-stage, betwixt and between childhood and seniorhood, the desired status as members of Samburu elders. Usually, at the end of one's time as a lmurrani, or just after, one may get married and have children who can carry the family name into the future. To be a warrior is a transient, engendered stage and time-period in men's life-worlds, which might explain why the importance of rock art is played down. However, even if Samburu people seldom talk about rock art and generally make light of its significance for their cultural identity (cf. Holtzman Reference Holtzman1995; Pavitt Reference Pavitt1991; Spencer Reference Spencer1965), when asked, most people are aware of the rock art and in what context the artworks have been created. This suggests that we have to alter our perspective to understand how lmurran rock art is made meaningful.

First, the rock art discussed is of great significance, since the created images are all based on this-worldly experiences of lmurran as herders and warriors, unfolding key events and features of their life-worlds. The lmurran identity creates what cognitive anthropologist Jean Lave and educational theorist Etienne Wenger (Lave & Wenger Reference Lave and Wenger1991) have termed ‘a community of practice’; a social and, in this case, engendered cultural identity that is bound together by the members’ common interest in a particular domain or field, i.e. Samburu warriorhood. A community of practice is formed when people deliberately share a common goal, gaining knowledge about a specific economic, social and ideological field. By the process of sharing information and experiences within the group, members learn from each other and have an opportunity to develop personal and professional bonds (Wenger Reference Wenger1998) and, in this case, a cultural identity which transcends generations of warriors.

What makes this notion applicable in the case of lmurran is the common coherent identity that is bestowed on an age-set of warriors (Table 1). In this context, rock art acts as a ‘secondary agent’ (e.g. Gell Reference Gell1998), an inter-generational medium exceeding time that transfers and embodies a common cultural engendered identity and community of practice. Current lmurran watch and learn from previous age-sets’ artworks, adding their commemorations and style, and nowadays also names of the age-set and the artist/s who made the rock art (Figs. 5, 6, 8). Even if the artworks are created as a pastime, the imageries are also the subject of an elusive generational and inter-generational visual culture, which sometimes sparks a spirited competition between past and/or contemporary rock art artists.

Part of what constitutes this community of practice is the vibrant account and legacy of previous warrior groups, manifested in the age-sets listed in Table 1. Both present lmurran, as well as Junior and Senior Elders, are well aware of when, where and sometimes who it was that created specific rock art images at certain places, with oral histories stretching back to the mid nineteenth or even the eighteenth century. Here it is interesting to note that the stories which are shared among lmurran, as well as with outsiders, also include places where rock art has recently been created but where the artworks, for different reasons, no longer can be detected. Some lmurran paintings are well preserved and made generations ago, while others disappear quite fast, some after only a few years, as exemplified by the paintings at the water pool close to Ngurunit (our Site 5, see also Sites 3 and 4). In such cases, places embody intangible cultural memories within the community of practice, regardless of the presence or absence of tangible material culture. This discloses a deeper cultural connection and relation to places, the rock art, its landscape settings and its significance as an inter-generational engendered medium which, in this case, are crucial aspects of the cultural identity of lmurran. It also underlines the importance of exploring and exposing how rock art and other material culture mediate and unfold people's life-worlds. Often, the social practices and places where rock art is created are of greater significance than the artworks we explore as archaeologists and rock art researchers.

What at first sight might be viewed as a pastime, leisure activity and something to do just for pleasure, in this case lmurran rock art, can therefore be given a deeper culture-historical interpretation and implication. Importantly, without the informed emic perspectives from past and present lmurran, it would be close to impossible to provide such understanding, which calls for further studies and research of the ongoing Samburu rock art tradition.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our sincere gratitude to the Samburu community members of the Ngurunit settlement for their hospitality and collaboration in finalizing this article. Especially, we wish to thank Nchalugi Loloibor of the Lkimaniki, Ltanyaye Lempate of the Lkichili and Ltaulon (Simon) Lesadala and Sania (James) Lempate of the Lmetili for sharing their time and knowledge about lmurran rock art with us. Thanks also to the Lengewa relatives, Lejinai, Lmapili and Leramis, for sharing their stories concerning lmurran rock art in the South Horr area. Judith Crawford corrected our use of English, thanks! Our three reviewers gave us plenty to think about and we thank them for their constructive criticism that strengthened our paper's arguments. Last, but not least, our appreciation to the Department of Cultural Science at Linnæus University for funding our fieldwork and collaboration with Ngurunit community members.