Joe Sacco is distinctive both in figure—immediately recognizable from his self-deprecating caricatures, complete with sightless glasses and contorted expressionFootnote 1 —and as a pioneer of graphic journalism. So vital is Sacco’s contribution to the formation of this genre that, upon the release of Footnotes in Gaza (the second of Sacco’s graphic narratives of the Palestinian conflict with which this paper is concerned), he was identified as “virtually a one-man comics genre: the cartoonist-journalist.”Footnote 2 The author’s oeuvre includes Safe Area Gorazde—an intricate deployment of comics narrative that details the way in which its author “[immersed] himself in the human side of life during wartime”Footnote 3 during a Bosnian visit that took him to Gorazde and, later, to Srebrenica (site of the 1995 Srebrenica genocide, in which more than 7,000 Bosniak men and boys were killed by Bosnian Serb forces).Footnote 4 This intentional “immersion” in zones of conflict for journalistic purposes, and the subsequent interviewing and collation of firsthand experiences, is a unifying theme across Sacco’s corpus, but one that becomes particularly salient in the context of Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza—Sacco’s Palestine narratives.

The anthropologist Patrick Wolfe asserts that “settler colonialism is inherently eliminatory”:Footnote 5 in other words, the project of colonialism is the erasure of the native. In this article, I suggest that the inherent polyphony of the comics medium—the ability to present at once not only the textual and the visual, but multiple narrative threads—facilitates the strategy of collation in Joe Sacco’s Palestine narratives, which are an endeavor to write back and speak out against the Israeli occupation as a colonial regime that has previously undertaken to silence Palestinian voices.

Accusations of bias proliferate throughout (and on both sides of) the reportage of the conflict between Palestine and Israel. This is hardly surprising, given that the war’s origins lie in the contestation of claims to territory: as Aimé Césaire notes in Discourse on Colonialism,Footnote 6 “No human contact, but relations of domination of submission which turn the colonizing man into a classroom monitor, an army sergeant, a prison guard.” One looks, for example, to work such as Chomsky and Pappé’s Gaza in Crisis—denoted as “reflections on Israel’s war against the Palestinians”Footnote 7 —which elaborates upon an established divide by positing Israel as both different from and irreconcilably “against” Palestine. In keeping with this hostility, a series of dichotomies become evident in various global reportage of the conflict—here I refer to the reportage of Al Jazeera and The Jerusalem Post (among others), which privilege Palestinian and Israeli viewpoints respectively. However, many pro-Palestine commentators, including Saree MakdisiFootnote 8 and Amira Hass,Footnote 9 note the representation of Palestinian civilians only “as terrorist and as victim,” without the possibility of occupying any kind of middle ground: a fact identified by Sacco himself in one of many interviews in which he elaborates upon his purpose in reporting the Palestine conflict through comics and his methodology in doing so.Footnote 10

Joe Sacco’s Palestine narratives are therefore informed and shaped both by his personal observations and by the firsthand narratives related to him, both of which pay as much attention to the quotidian as they do to the kind of cataclysmic events that might more commonly be seen in global headlines. His work makes the continually violent occupation simultaneously into both art and journalism, weaving together these ostensibly divergent genres under the remit of comics to aid in collating Palestinian stories, and thus in “writing back” against the colonial impulses of occupation. Transcribed through the lens of his trademark self-deprecation and consciousness of his own fallibility as narrator and mediator, Sacco’s journalism masterfully interrogates complexities and nuances of lives under occupation. It is a representation both visual and literary of what he saw, delivering what he perceives to be the “essential truth” without assuming any kind of false objectivity.

Comics and Collation

Although Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza share spatial focus and historical context, and both exhibit the hallmarks of Sacco’s comics style, there are important distinctions between the respective functions of the two works. The narrative of Palestine follows Sacco around the Occupied territories, investigating what it means to be Palestinian when forced displacement and an oppressive military regime have all but negated the term. In contrast, Footnotes in Gaza shadows Sacco’s attempt to trace two separate, single historical events; parts of a “forgotten war”Footnote 11 of 1956.

Sacco’s fellow comics artist Shaun Tan notes in “The Accidental Graphic Novelist” that the self-reflexivity of comics means that they can often “access a world that is otherwise inaccessible.”Footnote 12 Tan applies this logic of the “interesting space between the sound of words and the site of pictures” to his own comic The Arrival; he suggests that his own work is comparable to Raymond Briggs’s The Snowman Footnote 13 on the basis of a “shared concept of crossing thresholds, action that transcends language, and constant ambiguity.” In tandem with this, we might read the multimodality of comics narrative—to employ a term coined by Thierry Groensteen (a French academic leading the global field of comics studies), the plurivectoriality of the visual and verbal tracks—as enabling the representations of “everyday experiences that might be deeply felt but often hard to describe through words alone”:Footnote 14 an apt decision, in consideration of the bloody history of the land in question and the potentially traumatic nature of telling and retelling.

Although many of the stories Sacco depicts originate from Palestinian recollections, the eventual, multimodal narrative is his own. In this way, he speaks further to his self-assigned role as “gatekeeper,”Footnote 15 a journalistic function elaborated upon further by Kovach and Rosenstiel in The Elements of Journalism. This work identifies the “gatekeeper”—the journalist—as the figure whose role consists of “deciding what information the public should know and what it should not.”Footnote 16 Such an interpretation speaks immediately to Sacco’s implicit engagement with a critical discourse of post-colonialism, that is—who is permitted to represent whom? Does a written act of witness assume an immediate authority or constitute a pretension toward it? Hillary Chute advances this line of inquiry in relation to comics’ increasing formal prestige in Disaster Drawn, asking “Why, after the rise and reign of photography, do people yet understand pen and paper to be among the best instruments of witness?”Footnote 17 In fact, Chute also poses an earlier iteration of the question to Sacco in an earlier volume of interviews entitled Outside the Box: Interviews with Contemporary Cartoonists: Sacco’s answer is that “when you draw . . . You can always have that exact, precise moment when someone’s got the club raised.”Footnote 18 The value of the graphic stems thus not from its “veracity,” but from its ability to capture and convey the action and the feeling of a moment. For this, Sacco relies upon multiple threads of narrative—both divergent and intertwining—and the integration of the visual and the verbal that is so particular to comics narratives. In this paper, therefore, I move to foreground the relevance of the question of witness in the context of Sacco’s Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza. Although Chute deems the “proliferation of perspective part of the most basic grammar of comics,”Footnote 19 I argue that “basic” here refers simply to the fundamentality of this “grammar” to Sacco’s narration of the Palestine conflict. The “grammar” of polyphony allows Sacco to collate the experiences of those for whom the violence of occupation is merely a fact of daily life alongside his own research and the events that he has witnessed.

Sacco in the Text/Territory

“Palestine not only demonstrates the versatility and potency of its medium, it also sets the benchmark for a new, uncharted genre of graphic reportage.”Footnote 20

In interrogating the colonial logic that consigns the voices of the marginalized to the peripheries of global media and historic attention, Sacco’s Palestine narratives invariably arrive at the troublesome question of representation. Although the strategy of collation in these particular works attempts to provide a platform for the stories of ordinary Palestinian people, to do so necessitates at least one organizing figure to conduct that collation in practice. Here, that figure is Sacco and, as such, readers must remember that all stories (even those communicated in first-person narratives, and through speech bubbles issuing from specific figures) are mediated via Sacco’s voice and thus through cultural intervention from the West. Particularly problematic is the fact that Sacco is an American citizen: the United States of America having historically aligned itself with “isolated and repressive regimes whose major virtues, in the cases of Israel and Egypt, were that they were willing recipients of U.S. arms, loan services, technical expertise.”Footnote 21

Therefore, if Sacco’s comic books are both formally and textually occupied with multiple layers of witness—and the storytelling of experiences both individual and collective—the means through which his own presence is depicted in his works is similarly dependent upon this graphic medium. He is able visually to register the plurality of narrative strands that make up his image of life in Palestine, but the self-awareness with which both Palestine and Footnotes are produced ensures that Sacco is himself a presence in the text as constant and unavoidable as the intangible sense of “occupation” that is etched onto the very landscape itself (of this, more later). This is crucial because it emboldens the line of readerly questioning that Sacco advocates throughout. In fact, Rose Brister asserts that “no other focalization strategy is more effective and more complex than Sacco’s representation of himself as the narrative everyman upon whom we can project our expectations, fears, and desires.”Footnote 22 Sacco encourages readers’ awareness of his presence in the narrative not only as an author, but as an investigative journalist and as a subjective character. In particular, Sacco discerns the journalist manifestation of himself as “someone who you have to put a bit of faith in,”Footnote 23 noting ironically that, after all, “[he] was there.” This is the same logic that applies to the storytelling of his interviewees. Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza epitomize this approach because their iconic solidarity—“interdependent images that . . . present the double characteristic of being separated”Footnote 24 —is emblematic of the sheer multitude of narratives and experiences that Sacco compiles here to form a more expansive (if not, necessarily, more accurate) portrayal of the material and structural experiences of occupied Palestine.

It is the elasticity of the comics medium—its innate ability to adapt to official narratives and to contest them simultaneously, and the literary space that it provides to do so—that cements its position as the appropriate medium for Sacco’s particular brand of documentation and witness. This is not without its problems, however, and here I invoke the work of Hortskotte and Pedri in an exploration of the narratorial devices Sacco employs. The impetus for this line of inquiry lies in the multiplicity of witnessing voices that permeate throughout both Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza. Because Sacco’s work is investigative by definition, it makes sense that the majority of the stories originate from his Palestinian interviewees. Here, I am largely concerned with the presence of Sacco in Palestine and Footnotes as a narrator, and the way in which he allows this to determine the “focalization”Footnote 25 of his storytelling. He is a reporter and interviewer, as well as an eyewitness: questions of subjectivity, of audience, and of purpose are foregrounded constantly as a result of the “plurivectorial” narration.Footnote 26 In fact, it almost makes sense to identify separate “character-Sacco,” “narrator-Sacco,” and “author-Sacco,” so disparate are the identities of each. Thus the much-lauded self-consciousness of Sacco’s work is evident here, acting as an organizing thematic structure through which the cartoonist is able to tie together his own observations with the stories of those he meets, without privileging the “truth” of either narrative strand.

Sacco’s engagement with the concerns of postcolonial scholarship as regards the occupied territory is evidenced in Palestine when character-Sacco shows his guidebook to a Palestinian man. Notably it is not an Israeli guidebook but a Western one—“No, I think it’s Australian”Footnote 27 —and entitled “A Travel Survival Guide”: this condescension suggests a Western predisposition to conclude the Palestinian situation to be devoid of any characteristic besides danger, while the explicit reference to Australia implies the preposterousness of someone so far removed attaining any semblance of knowledge of the actual Palestinian situation. The Palestinian man is, of course, horrified at this Westernized, derogatory depiction of “an Arab and a donkey” and aggressively informs Sacco “In my family, my cousins, we have students! A professor! A teacher of computers! Arabs have technology! And we Palestinians love education!” Each exclamation references education as a vibrant and important feature of life, while Sacco’s rendering of the man’s face is one of contortion and aggression, lending emotional weight to the Palestinian man’s argument that the actuality of his life is disparate from the desperate provinciality authors such as “Neil Tilbury” present in their guidebooks. The episode highlights the extent to which the power to establish a dominant line of storytelling lies with a faceless “authority” rather than with the people who experience the conflict firsthand: once more, the erasure of marginalized voices by a dominant and violent colonizing regime.

Thus far I have avoided overt reference to other “serious comics” on the basis that Sacco’s journalistic purpose distinguishes his work from the often-autobiographical nature of that of his contemporaries. This comparison with other so-called “serious” comics—including Art Spiegelman’s seminal Holocaust memorial Maus, Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (oft-cited examples)—is one that perforates contemporary scholarship on Sacco’s work (including a number of the works comprising Worden’s edited volume). In the sense that each of these works uses the comics medium to transmit narratives that are “nonfictional” and often traumatic, comparisons are easily drawn. I suggest, however, that Sacco is doing something different to his contemporaries here. His manipulation of comics’ inherent capacity to display multiple narrative threads, and his strategic collation of these narratives into a politically motivated volume, is an effort to construct a dialogue in which the habitually silent voices of those under occupation are shared.

One has only to read “Prisoner on the Hell Planet”Footnote 28 in Maus – a comic strip in which Spiegelman depicts the events immediately prior to and following his mother’s suicide—to determine the work’s inherently personal nature. Although one senses that Maus has been, at least on some level, an expression of catharsis for its author, Sacco’s work is exploratory, ironic, and often self-referentially detached to the point of being callous. Yet it is in the “multimodal narration”Footnote 29 that Maus, Palestine, and Footnotes are deployable in conversation with one another. Both texts incorporate the authorial voice and, by extension, the authorial figure, alongside the visual representation of stories related to them. Intrinsically tied to this are the privileged positions that both authors occupy in terms of obtaining the research their work requires. Spiegelman’s access to the personal Holocaust memoir occurs as a result of his familial connection: Sacco’s narratives are made possible by the very privileges that are afforded to him both by his American citizenship and his status as a reporter, privileges of which he is extremely conscious. The collation of aspects of this such as vehicular access, press pass, and American accent are all aspects of “Sacco in the text”—all means through which he is able to navigate the territory in a different way to those for whom it is a permanent residence. Illustrating this in comics form means that Sacco is able to caveat his observations with an acknowledgment of his narratorial privilege and, in doing so, speak to comics’ “self-reflexive interrogation of the politics . . . of its own capacity to represent.”Footnote 30

Returning once more to recent scholarship on Sacco’s work, Marc Singer suggests that although Sacco is outwardly disparaging of attempts at “objective” journalism, “Palestine also replicates many of those same practices.”Footnote 31 Here, Singer alludes to the “secondhand testimonies” in the text, which, he claims, Sacco uses to imply an authorial “viewless objectivity.” Problematically, however, Singer’s contention that Sacco is a comics journalist is based upon the spurious argument that his work is “Far more traditional than his critics, his defenders, or most of his interlocutors acknowledge.”Footnote 32 I argue that Singer’s argument here is contradictory: for example, he suggests that Sacco prioritizes Palestinian perspectives and is unwilling, in certain situations, to condemn Palestinian violence—notably Palestine’s “laws,” an episode recounting a familial honor killing—elements of Sacco’s work, which, I argue, evidence the political motive of author-Sacco in giving voice to the marginalized Palestinian community. Regardless, Singer raises the traditional objectivity of journalism as a technique that Sacco uses “to fall back on” during scenarios in which he does not deem it politic to exercise his own opinion. This is not the case.

Not addressed here is the fact that Sacco’s subjectivity within the text is derived from the fact that he does not shy away from admitting his privileging of a historically underrepresented Palestinian viewpoint; but his objectivity lies in the sense that, having laid this initial groundwork, he does not pass judgment on those involved in the conflict as people. Kristian Williams concurs in “The Case for Comics,” arguing that Sacco “shows us what he has learned—including those elements that frustrate any easy conclusions.” The “easy conclusions”Footnote 33 Sacco avoids are not just those typically perpetuated within American media—positing Palestinians as “angry and hostile dreamers”Footnote 34 through “patterns of decontextualization and imbalanced sourcing”Footnote 35 —but those in opposition, which iron out the individualities of the Palestinian populace and group them, collectively, as “victims.” Indeed, in the introduction to a recent volume dedicated to the study of Sacco’s work, Daniel Worden comments that the comics journalist “neither romanticize[s] suffering, nor legitimate[s] violence.”Footnote 36 The implication is not, of course, that Sacco himself has no opinion on such matters—interviews, as cited in this article,Footnote 37 provide plenty of evidence to the contrary—but that he provides his readers with comics constructed from multiple, often differing narrative threads and that the work of the reader is to engage with these threads, to question the legitimacy of the stories they tell, and more importantly, to question Sacco’s own right to act as translator and mediator of these.

“Shapes in the Dark”Footnote 38 is another demonstrative example of the ways in which the imaginary capacity of comics enables Sacco to represent experiences that could be verbalized only with extreme difficulty. The entirety of this section is shrouded in darkness; at one point, a caption box tells the reader that “If there is a tank there, we cannot see it.” This text is imposed over pitch black—Sacco does not imagine a tank. Although his medium is interpretive by nature—he notes himself in Journalism that “the cartoonist draws with the essential truth in mind, not the literal truth”;Footnote 39 he will not exercise this in relation to something that cannot be verified by anyone at all.

Sacco’s journalistic training makes itself apparent in the meticulous manner in which his work is researched, as well as in his self-identified pursuit of “truth” over “objectivity.” This does not mean an objective “truth” in the sense of a narrative that can be proven concretely “right” or “wrong,” but a more elusive sense of reporting lived experience. There is an almost metafictional aspect to Sacco’s texts, as the research process becomes an integral part of the finished product. This is seen particularly in Footnotes: Sacco makes extensive reference to his gathering and organizing of stories, as well as his perception of their “usefulness.” Assessing the form of Palestine, however, throws up some interesting curveballs; for example, “Remind Me.” Structured in a way that alludes instantly to a broadsheet newspaper—text in columns, illustrative images—it is as though Sacco uses the form to foreground his journalistic purpose and appeal to his readerly assumptions of “accuracy” that might accompany this. In comparison with the remainder of the work and, indeed, with Footnotes in Gaza, this section stands out for its verbosity and movement away from the visual narrative track.

Does this therefore count as an instance of authorial doubt in the comic medium? That Palestine was initially serialized might indicate fluctuations in what Sacco deems an appropriate means of representing his findings. To interpret the passage in this way, however, is to ignore the visual strand altogether—and, as in the rest of the work, it is paramount. Focalized through Sacco’s eyes, there is suspicious eye contact from children playing in the street;Footnote 40 hands pushing the journalistic intrusion away, which are afforded a more violent urgency through Sacco’s use of foreshortening; intricate portraits of pop cultural figures from both the West (Chuck Norris) and the East (Oum Koulsom).Footnote 41 Although the visual narrative here is not as prevalent as its verbal counterpart, it is nonetheless a result of the comic book form that Sacco is able to manipulate his verbal-visual ratio in this way.

Although Sacco’s work has been lauded by critics both academic and otherwise, perhaps one of its most reputable admirers is Edward Said, who penned the introduction to Palestine. Said sums up Sacco’s purpose in the occupied territories succinctly thus: “Joe is there to be in Palestine, and only that—in effect to spend as much time as he can sharing, if not finally living the life that Palestinians are condemned to lead.”Footnote 42 Sacco never permits his readers to forget that he, too, is aware of the limits of his own empathy as well as his own objectivity. When Said notes that “Joe is there to be in Palestine,” it is because this is truly the aim: to construct but one among many narratives of Palestine. Indeed, Said is present himself in Palestine, as Sacco stumbles across a copy of Orientalism in a home in which he is a guest. Ironically, this iconic text of dispossession instigates in character-Sacco a desire to “sit around a heater with people like Larry [Sacco’s friend] and read Edward Said.”Footnote 43 Here, he provides an entirely self-conscious acknowledgment of the cultural climate in which he is reporting. Placing Orientalism in the text is a deliberate move that also alludes once more to the Western privilege that both permits Sacco’s movement around the occupied territory and impedes him in his quest to be “finally living” the same experience as the Palestinians.

It is interesting, then, that Sacco describes a piece such as “Hebron: A Look Inside”—originally published in TIME magazine and now found in Journalism, a volume of Sacco’s shorter works—as his own “least successful piece of comics journalism.”Footnote 44 Superficially, it is immediately distinguishable from Palestine and Footnotes: for a start it is in color, in comparison with the black-and-white photorealism of the two longer works, peppered with moments in which he must verbally identify the distinctive hues of “police in blue” and “border police in green.”Footnote 45 But it is Sacco’s turn here to a more traditionalized, objective form of reporting that he identifies as the reason for his “failure” to “adequately convey the great unfairness of making the free movement of tens of thousands of Palestinians hostage to the considerations of the few hundred militant Jewish settlers.”Footnote 46

In a notable passage about halfway through Footnotes, Sacco invokes comic book form to illustrate this detached investigative approach. In an interview, Sacco explains a methodology of copious note-taking, reminding himself of the details of particular scenes in order to draw them after he has immediately experienced an event or conducted an interview. He speaks in interview of “checking” situations with his guide to render them with accuracy. He says:

I’d say, “OK, so remind me.” He’d tell me right away what’s going on, so it’s already in my head: then we get back. We’d often sit and I’d say, “How do you remember it again?” I’m checking with him and then writing it in my journal—especially something like that, because I want to get it right.Footnote 47

The process becomes quasi-scientific in its methodology: in Footnotes Sacco claims he and Abed have “broken down the main event into its component parts,”Footnote 48 deliberately removing any sort of human emotional attachment in the analysis of their investigation. Interviewees become numbers, like subjects in a lab experiment, because Sacco “can hardly keep anyone’s name straight.” Sacco is flippant, dismissive; and yet this apparently offhanded comment serves subtly to highlight the author’s organizing concerns of the accuracy, truth, and reliability of a witness. Certainly, we should question the stories we hear at the level of the eyewitness, as Sacco and Abed do: but when those who act as our translators and transcribers acknowledge their own fallibility, what effect does this have on the extent to which we can rely on the stories they transmit? Only one panel later, Sacco says that “The more [he and Abed] hear, the more [they] fill in our picture of that day in ’56, the more critical [they] become of each tale we hear.” Again, his narrative is painfully self-deprecating: character-Sacco equates volume of testimony with reliability, and suggests ironically that his investigation imbues him with an understanding of the historic situation in Rafah more profound than that of those who were actually present. The comic book’s intersection of visual and verbal elements is similarly vital in compounding the irony of the scene, as Sacco and Abed “drink coffee and eat those honey-drenched pastries,” enjoying a cigar each as they kick back, relax, and assess the accuracy of tales of massacre. Chute recognizes that “Sacco’s drawing of another’s testimony is both meticulously researched, in collaboration with the witness, and necessarily imagined.”Footnote 49

So the attraction of comic book form for Sacco’s reportage is not that its multimodal narrative, variable focalization, and intertwining of the visual and the verbal facilitate the expression of a singular concrete narrative. Rather, it is that the more information is available to us as readers, the more questions we are able to ask regarding the witnessing, documenting, and reporting of Palestinian conflict—and the wider the scope of the narrative strands we are able to view in conversation with one another to achieve this end. In Footnotes, character-Sacco begins ironically to posit that the volume and breadth of the experiences to which he has listened positions him as a greater authority on the subject than those whom he has interviewed, and who were actually present in the situation. An implicit sense of irony here alludes to the project’s nature as a contested narrative—and one of a contested territory, at that, already implying a variety of different perspectives at the level of the land—and the reader is led to understand that collective experience does not preclude difference in recollection, but that this does not lessen the “accuracy” nor the validity of the emergent narratives. Sacco says himself that “As much as journalism is about “what they said they saw,” it is about “what I saw for myself.”Footnote 50 That “as much” importance is assigned to both facets of the narrative is crucial: Sacco does not privilege his own observations, nor does he depict those of the Palestinian inhabitants as entirely authoritative. As such his presence in the text works in vital conjunction with the comic book medium, whether in consideration of his position as author, interviewer, or observer: it ensures that some idea of a dissenting narrative—one that may not concur with those previously related, but is not rendered of any less importance by this fact—is always foregrounded for Sacco’s readers. Fallibility of narrative is not essentially a negative trait in these works; rather, it highlights the sheer multiplicity of the marginalized narratives communicated through the comic and provides an important impetus for its readers to question beyond the page. It is, furthermore, an invitation to texturize one’s interpretation of the Palestinian conflict by juxtaposing it with other, disparate narratives that are equally flawed, but equally important.

Life in Contested Territory

Across accounts of the conflict over the Palestinian territories, one notices a unifying thematic thread of elasticity, changeability, and impermanence. The historic borders of the area now considered “occupied” territory have shifted according to the regime in power at any given temporal moment. Indeed, one might refer to the currently ongoing furor regarding the recognition of Palestine on Google Maps as a pertinent example of the ever-shifting nature of Palestine’s national identity.Footnote 51 In this paper, I address the ways in which the land—in particular, settlements along the West Bank and the Gaza Strip—register the violence that is a ubiquitous part of everyday life. My line of inquiry here draws upon Eyal Weizman’s Hollow Land, which argues that all features of the land register and illustrate the nature of the occupation, whether these are manmade or natural: in conversation with Weizman and others, I endeavor to investigate the ways in which the landscape influences and is influenced by occupation both ongoing and historic.

As Weizman argues, “the organization of geographical space cannot simply be understood as the preserve of the Israeli government executive power alone, but rather one diffused among a multiplicity of—often non-state—actors”:Footnote 52 for this reason, I choose to emphasize not the instigating ideologies behind the architecture of occupation, but the ways in which Sacco’s work represents this physical registration of the regime. The Israeli occupation regime—registered from military force or from the violence of individuals—treats the oppressed population as a faceless Palestinian mass rather than a collective made up of individuals. Sacco’s renderings of the architecture disrupt this narrative and explore the biopolitical impact of occupation on individuals to form a more complete, cohesive picture of the Palestinian situation at large. As Wolfe’s now-famous maxim states, “settler colonizers come to stay: invasion is a structure, not an event”Footnote 53 —and with this in mind, how is the occupation regime encoded upon the land and the architecture of occupied territory? And what is the capacity of comic book form to register—and to represent—this spatialized violence?

The first and most fundamental element of the occupied territory is the construction of borders. The geographical reach of the land claimed as “Israeli” and that which is identified as “Palestinian” is subject to constant shift—so much so that Weizman notes “Against the geography of stable, static places, and the balance across linear and fixed sovereign borders, frontiers are deep, shifting, fragmented and elastic territories.”Footnote 54 Spatiality and the ways in which it intersects with both conflict and power are therefore immediate concerns for Sacco’s work on Palestine. Even the titles speak to a pertinent discourse about state legitimacy: the nomenclature of Footnotes in Gaza situates the narratives within a specific strip of land, the stories and the inhabitants of which are—as is implied by the terminology of “footnotes”—often overlooked or deliberately consigned to the peripheries of conflict narrative, and to name Palestine is a political act, acknowledging a state that is not currently recognized by all global authorities.Footnote 55 In Sacco’s work then, it is notable that although participants on both sides of the conflict refer to Arab inhabitants of the land as “Palestinians,” this name is used predominantly by those who actually self-identify as Palestinian. In such instances, claiming Palestinian nationality is an act of dissent emblematic also of claiming the territory that accompanies it: it asserts that the Palestinian population remain Palestinian, in spite of their forced displacement and the continual lack of recognition for their country.

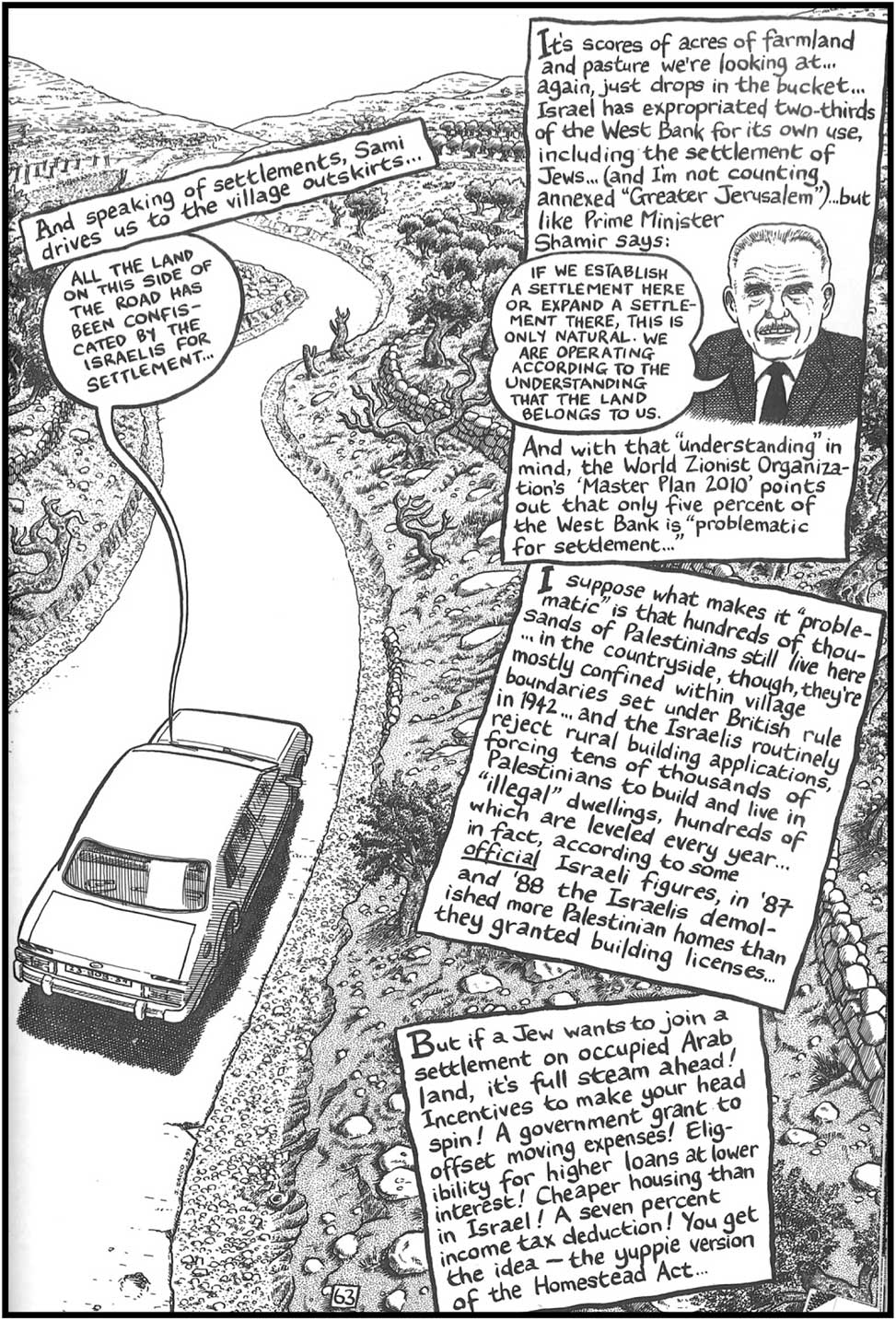

More visually pressing in Sacco’s work is the actual, physical land of which ownership is the source of such violent altercation. An impression of territorial instability is true for both sides of the conflict because it results from a constant lack of consensus regarding the parameters of land and its “rightful” occupants: nonetheless, there is a crucial distinction to be made in the fact that the Israeli occupation controls this border, while the Palestinian population is subject to the persistent threat of enforced repositioning. In Palestine, Sacco’s guide taxi winds its way through the West Bank: though the comic itself is static, use of the splash page so that the image of the arable land extends to the edge of the page—and, it is implied, well beyond—and progressively fainter renderings of the mountain scenery toward the horizon line convey both the movement of the car and the vast “acres of farmland and pasture”Footnote 56 through which it travels. Because the borders are so little evident, the elasticity of the occupation frontier becoming increasingly apparent, although we must be mindful, of course, that to refer to an “elastic” border is still to interpret it as an entity both liminal and limiting. A speech bubble issuing from the car says “All the land on this side of the road has been confiscated by the Israelis for settlement”:Footnote 57 an informative statement, if a misleading one, because the violence of this land project is belied by the seemingly innocuous “settlement.” “Settlement” seems lexically to overlook the fact that the West Bank is “problematic” in this regard; “problematic” is Sacco’s own ironic choice of word to denote the presence of Palestinians in the territories sought by Zionist forces.

Sacco relies on the intersection between the visual and the textual to represent the occupation regime in this scene, however. In the vast swathes of land that he depicts—his taxi dwarfed by the rolling vista—there are no outward manifestations of military or violent control. Far from undermining the more self-evident expressions of violent occupation, however, this suggests the collective social absorption of “occupation” as a constant state. Although there are, as yet, no visible Israeli settlements, this land is still recognized as having been “confiscated” from the Palestinian people. In Sacco’s drawing, it is of further note that the caption boxes are imposed over the rendering of the land: a compilation of incentives for Israeli settlers (“A government grant to offset moving expenses!” see Figure 1) blocks reader perception of the rural vista, as does a photorealistic portrait of Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Shamir. The latter figure states that “If we establish a settlement here or expand a settlement there . . . we are operating according to the understanding that the land belongs to us.” That the lexical symbolism of this powerful Zionist “understanding” obstructs readers’ view of the occupied Arab land is a tangible reflection of the Israeli dominance. Thus, the form of comics enables Sacco thus to visualize the territorial claims of both sides of the conflict simultaneously.

Figure 1 Settlement frontier. Joe Sacco, Palestine, 63.

Ray Dolphin claims that although Israel may not be defined through “recognisable borders,”Footnote 58 its independence is not threatened by a lack of “existential security.” The Zionist impetus behind the Israeli side of the territorial conflict has been able to establish dominance, but as Dolphin proceeds to outline, the continuing presence of dissatisfied Palestinians is testament to the fact that “Israel has not solved its native problem.” The construction of the “West Bank Wall” along the Armistice Green Line was approved by Ehud Barak in 2000—during the interim period between Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza. The latter is therefore anaphorically implicated in conversation with Sacco’s previous work: Sacco’s oeuvre itself is testament to the number and variety of narrative strands regarding occupation. He interweaves geographical representations and historical explanations, in a different and, arguably, subtler deployment of comics’ inherent polyphony: these are the closest examples of empirical impartiality that his work displays, and they provide him with a relatively neutral backdrop for the more personal accounts he employs later on. In this capacity, one might argue that Sacco’s reportage retains some of the journalistic objectivity at play in his earlier career. Compared to a piece such as Amira Hass’s Reporting from Ramallah, the narrative of which frequently employs statistical support for its claims—for example, she cites an official statistic that “Before 1967, 527,000 dunams of the West Bank were registered as state lands by the Jordanian government”Footnote 59 to illustrate one particularly “common Israeli view that state lands are off limits to Palestinians”—Sacco’s use of widely accepted historical facts seems more an act of storytelling than an illustration of discovery. So brief are his forays into the wider historical paradigms of the conflict that, really, they serve further to highlight the importance of individual narrative strands in creating a wider understanding of what occupation means in a real, tangible sense. Yes, these statistics of displacement and destruction are an important measure of the scale and reach of the conflict; but in terms of lived experience and the testimony thereof, stories from survivors provide far greater detail and nuance. In collecting, structuring, and above all, telling the stories of interviewees alongside personal observations, Sacco’s narrative addresses the inherently political object of his work, while implicating his readers in a dialogue surrounding the validity and value of personal testimony in journalistic dispatches.

Infrastructure is of similar import in enforcing adherence within the wider architecture of occupation. Traffic can be halted at any time and for any reason; people talk about not being “allowed” to leave their refugee camps. Already though, we might interpret this as Sacco’s refutation of a wholly homogenous discourse of occupation. That he is personally able to move around is creditable to his press pass and his American nationality, certainly, but he is accompanied by translators and by taxi drivers: all people for whom the experience of movement and stasis within the regime would differ from those permanently entrapped in refugee camps.

An act of resistance is still an act of acknowledgment that there is, after all, something to resist. Thus it reifies the idea of existing disparate narratives; but does this diminish the innate rebellion of the act? Foucault’s theory of governmentality claims that “liberty is a practice”:Footnote 60 that no object or institution is innately repressive nor innately libertarian, but that it is human regime that imposes these qualities upon them. Resistance is also encoded in the practice of liberty, then, because even when one is under oppressive control one has the capacity to refuse it. As noted then, the very act of identifying oneself as Palestinian, in the way that Sacco’s interviewees often do, requires also the identification of that which is not Palestinian; again, necessitating the collation of apparently contradictory narratives. Therefore, the Israeli watchtowers in the Palestinian territories are perhaps the most obvious manifestation of the oppressive regime’s omnipresence. A sense of panopticism is evoked simply by the fact that these watchtowers are depicted as simultaneously ubiquitous and invisible: from the ground (as the reader sees from the panels’ perspectival orientation) it is not necessarily possible to discern whether these watchtowers are manned. The fixtures are drawn in such a way that it is often difficult even to find them on the page among the more prominent details of Sacco’s panels, although with closer attention it is possible to perceive their omnipresence. Sacco is able therefore to depict both his own paranoid sense of being watched and the different effect of this potential observance upon Palestinians for whom this is a far more quotidian experience. A poignant example of this occurs in Palestine when Sacco observes a small girl scanning the land for Israeli soldiers and finally worming her way through a hole in the fence: her awareness and exploitation of a “gap” in the surveillance indicating that this small instance of resistance occurs regularly. Sacco thus creates an empathic experience for his readers, facilitating their understanding of the extent to which occupation is encoded in the very lay of the land. These panoptic structures have been the subject of artwork other than Sacco’s, such as Taysir Batniji’s 2008 series Watchtowers, West Bank/Palestine. Batniji’s work relies on the visual alone, registering that “aestheticization becomes a vivid political challenge” Footnote 61 when an artist’s resources and movement are both limited. In comparison, Sacco’s Bruegel-esque landscapesFootnote 62 tend to absorb the intricately rendered watchtower structures within them. During Sacco’s transcription of stories from Ansar III jail in Palestine, for example, one panel combines caption narratives from two different men.Footnote 63 Sacco indicates the transition between their individual perspectives via thumbnail portraits accompanying their transcribed story, and yet the visual perspective of the panel is rendered in a medium shot: not quite an aerial angle, but certainly not focalized through the eyes of either of the witnesses. Only on the following page are Sacco’s readers provided with sufficient information to attribute the focalization to his feathered rendering of the watchtower and the shadowy omnipresence within. Even here, it is not the primary focus of the frame. Rather, its simultaneous ubiquity and invisibility is reified by the fact that Sacco is able to employ its visual perspective without his reader’s immediate awareness—and that, when readers do recognize the tower for what it is, its repetition allows it to become both deliberate stylistic trope and representation of what is understood or “accepted” to be part of the background noise of daily life under occupation.

It is not, however, the borders of the Palestinian territory alone that are subject to drastic and often violent change: more important on an individual scale is the bulldozing of homes, depicted by Sacco to evoke a sense of the occupation’s fundamental instability. It is a sense of vulnerability that permeates the domestic as well as the communal—we see this in the sandbags that keep the roofs down, but seem a permanent fixture. A similar sense in which the visual rendering of architecture is integral to the communication of general atmosphere is noticed by Chute in Disaster Drawn with reference to another of Sacco’s works, The Fixer. She states in one particular passage that “the abstraction of the clouds meets the details of architecture to evoke the unknowable,”Footnote 64 indicating a commonality of technique across Sacco’s approach to the medium of comics.

While the architecture of occupation is concerned primarily with biopower in the sense of the daily lives of Palestinian inhabitants, it is important also to recognize the refugee camps themselves: much of Palestine derives from events taking place in Jabalia, for example. Sacco’s attitude toward a Palestinian “everyday” in which a complete family is more unusual than one missing one or more members is evident elsewhere in the texts, but this is also encoded in the buildings themselves. Sacco is shown around one house in which bullet holes pepper the walls as they do the civilians.

Focus upon the contested nature of the territory is necessary in any analysis of this conflict, particularly one that centers upon the collation of disparate narratives; however, Sacco is not interested in determining the legitimacy of either side’s claim to the land. Although his extensive representation of Palestinian experience certainly weighs the narrative balance heavily in favor of those under occupation—and as Burrows observes, “The dissenters state that involving oneself compromises the balance of news reportage . . . [that] the bias is compromised to such a point that reportage simply becomes a diary”Footnote 65 —I argue that inserting himself as a character in this capacity allows Sacco to express his sympathies and gut reactions without explicitly taking an identifiable “side.” In fact, Sacco’s own response to Burrows is to assert that “There’s never just two sides” in a journalistic endeavor; an important further illustration of his self-awareness of the “inherent danger of subjectivity.” Rather, in representing the architecture of occupation, his use of comics is more noticeably useful in collating the verbal and the visual, constructing a more illuminating rendering of the conditions in which the Palestinian people are forced to live under occupied rule.

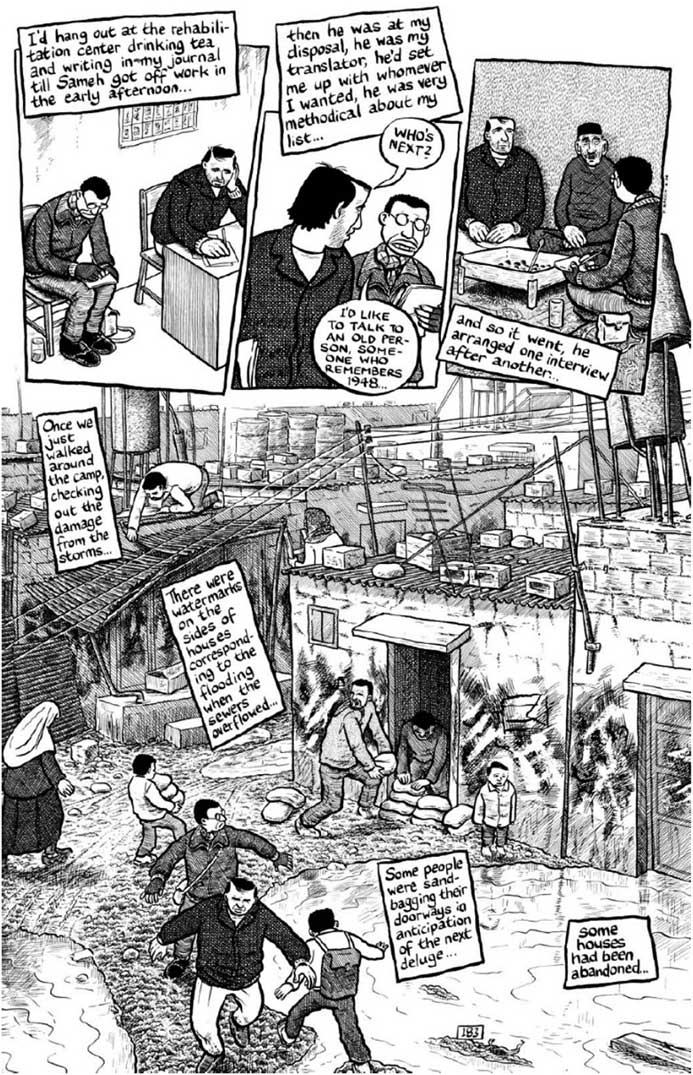

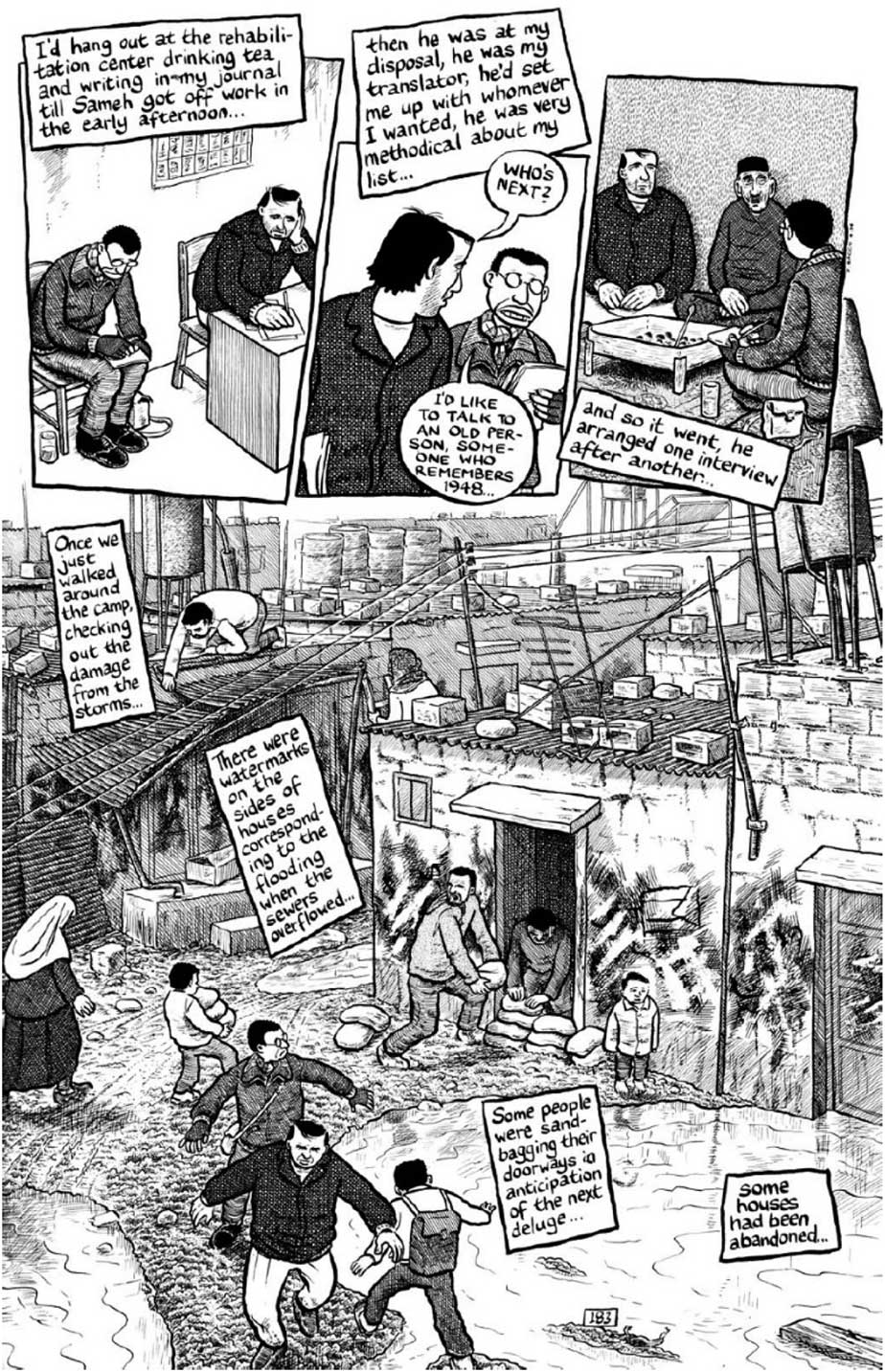

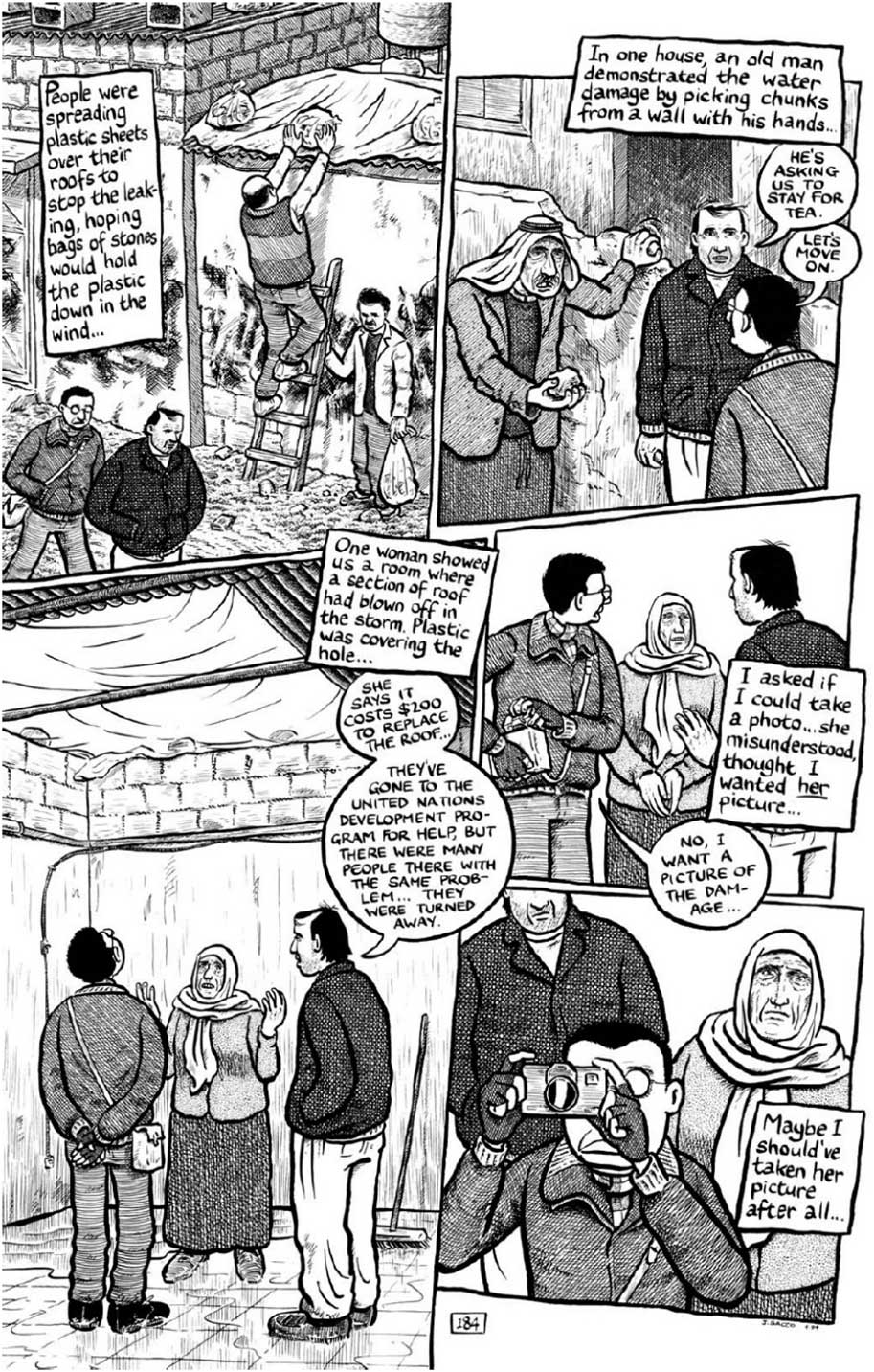

Particularly illustrative of this is a two-page section of Palestine in which Sacco depicts the more horrific aspects of the Jabalia refugee camp (see figures 2 and 3). Although Sacco employs black-and-white line drawing for the majority of his oeuvre, that same artistic decision here enables him to communicate a definite sense of the unavoidable grime inscribed upon the landscape. The graphic weight he applies to the mud on the ground, for example, and to the “watermarks on the sides of the houses” is particularly illustrative of the lack of structural hygiene and the extent to which it pervades domestic structures: according to UNRWA, for example, approximately 90 percent of the water in Rafah Camp is contaminated.Footnote 66 Such an impression is reinforced by details that appear only superficially minor; for example, the corpse of a rat that floats unheeded in the corner of the panel in one of the camp’s innumerable puddles, and the fact that, if one looks closely, one of the children in the image is barefooted in spite of the omnipresent filth. None of these aspects of the panel draws the eye alone. It is only in collation that they provide a more complete visual of the encoding of the regime in occupied architecture.

Figure 2 Jabalia refugee camp. Joe Sacco, Palestine, 183.

Figure 3 Jabalia refugee camp. Joe Sacco, Palestine, 184.

Sacco’s initial assessment of this situation is not immediately readable, due to the habitual blankness of his glasses (a feature of his work that has been the subject of substantial analysis, as in Rachel Cooke’s “Eyeless in Gaza”), but his later comment that “Jabalia was awful, [he’d] never seen such things”Footnote 67 provides a narrative hook—a point of reference back to his feelings in the moment. Once more, however, his permanent presence as a figure “checking out the damage from the storms” emphasizes his transience within the environment. Watching an old man demonstrating “the water damage by picking chunks from a wall with his hands,”Footnote 68 his reaction to an invitation for tea is “Let’s move on.” Here, character-Sacco seems to demonstrate a peculiar lack of empathy, unless one considers this once more within an interpretation of the text’s multilayered narrative: readerly sympathy is invoked for the old man in reaction to Sacco’s own illustrated callousness, so that the architectural registration of occupation is evidenced, too, by the human suffering that is incurred alongside it.

Even to locate Sacco on the page of this particular panel requires close attention, as he is camouflaged among the Palestinian figures attempting to preempt “the next deluge”Footnote 69 despite being in the foreground. Here, he figures himself once more as the organizing voice through which disparate narratives are collated; because he is not the character to which the reader’s eye is immediately drawn, we can infer that he has not been completely immersed into the Palestinian experience of occupation. As a result, we remain conscious of his presence as observer—in fact, in each of these panels he depicts himself staring at the damage and at the Palestinian people who attempt to live their lives around it. The final panel is a particularly metanarrative example of Sacco’s own fallible perspective as the comic’s structural adhesive. Drawing himself photographing the image of a damaged roof, Sacco emphasizes the aspect of his comics journalism that is wholly informative. Yet, even this is not an entirely objective panel because he expresses a personalised regret that “Maybe [he] should’ve taken [the roof owner’s] picture after all.”Footnote 70 Again, the text is almost painfully self-deprecating in its recognition of his privileged position as the collateral. That “maybe” is one of many aspects of the text that encourages his readers constantly to question the validity of his narrative; it focalizes his authorial presence as the lens through which all the text’s stories are transmitted, and thus his ability to include and omit where he sees fit. Perhaps the fact that this woman’s image is included in the finished artifact of Palestine—albeit as a cartoon, rather than as a photograph as, it is suggested, she hoped—indicates a sense of guilt on Sacco’s part; yet another subtle nuance to the polyphony of his narrative and a further implication of his own subjective presence as a filter for the stories and emotions of others.

In an interview Sacco has commented that one in pursuit of “An absolute literal group of images” as representative “might as well go to a photographer”Footnote 71 but adds that, despite the interpretive nature of his medium, he is firm that his renderings “have to be informed by reality.” As such, it is likely that Sacco has made a deliberate artistic decision to include multiple aspects of “the damage from the storms”Footnote 72 that he has observed, rather than aspiring to create a photorealistic replica of the street down which he gingerly picks his way. After all, his captions suggest “some people were sandbagging their doorways” and that “some houses had been abandoned.” Although it is unlikely that each of these features of occupation would be visible on each and every street, that Sacco collates these aspects of individual experiences into one image here makes a bolder claim to a more general, desperate experience of living under occupation.

As Weizman argues, the logic of occupation is codified in every stone of every street in the West Bank and in Gaza. Refugee camps, though ostensibly transitory, begin to concretize; roads and barriers create obstacles both official and unauthorized; the very land becomes significant as a site upon which Palestinians and Israelis habitually conflict: all of these demonstrate the extent to which the actual control of the occupation regime is dependent upon features of the land. As a reporter-observer, Sacco’s depiction of these architectural and structural manifestations of occupation are undoubtedly influenced by his own subjectivity. He is entirely conscious of this, however; in fact, he employs it to the advantage of his reportage by rendering his own observations of structures such as watchtowers alongside his transcriptions of the experiences of those who live permanently under these conditions. The comics form provides Sacco with the facility to interrogate lived experiences of occupation as they are encoded within the architecture of the land, acknowledging these through and alongside his own lens of observation, and interrogating the contested territory in all its complexities and nuances.

Conclusion

If Sacco’s narratives place such importance on the concept of “seeing for oneself,” it is through the inherent polyphony of comics that the multiple narratives—often diverse, contradictory, and following a haphazard chronology—of those who “see” can be represented simultaneously. The effect of this strategy of collation and its representation through the intertwining of the textual and the visual is to provide a platform for stories that have previously been relegated to the “footnotes”: verbalizing these stories becoming particularly crucial in writing back against the violence of occupation because, as Sacco tells us, “History chokes on fresh episodes and swallows whatever old ones it can.”Footnote 73 Moreover, although Sacco’s narratorial voice—and his deployment of his own figure as author, character, and journalist—make evident the privileged Western elements of his intervention, these also serve the dual purpose of highlighting Sacco’s own self-awareness of this problematic aspect and encouraging his readers to engage critically with his work and with the stories they hear. In the introduction to The Question of Palestine, Edward Said asserts that this particular book is intended as “a series of experienced realities, grounded in a sense of human rights and the contradictions of social experience, couched as much as possible in the language of everyday reality.”Footnote 74 Sacco’s project of narrative collation is easily read in conversation with such an aim; but in his comics, the medium’s inherent polyphony facilitates the deployment of these many narratives without privileging any single thread, nor overwriting the ongoing need for discourse and dialogue surrounding the occupation regime.