Impact statement

There are increasing calls for Indigenous participation in plastic pollution governance as part of a larger trend in Indigenous-led environmental management. Yet what counts as “participation” is so varied that sometimes models of participation are antithetical to one another, such as inclusion that becomes tokenistic, or when stakeholders and rightsholders are conflated. Here, we start by reviewing the state of how Indigenous participation is currently articulated and enacted in published peer reviewed and gray literature. This helps identify some of the common gaps between discourses of participation and their practice within writing projects themselves. Then, we turn to the different models, goals, and characteristics of participation in plastics pollution governance that are most meaningful to Indigenous peoples. The text is for primarily non-Indigenous or mixed groups who are looking to be more specific, deliberate, and just in their inclusion of Indigenous peoples in plastic pollution research, initiatives, and governance. We’ve designed what we hope is a fundamentally useful document so readers can be aware of the diversity, divisiveness, and opportunities of different modes of participation.

Introduction

The call for Indigenous peoples to be meaningful participants in environmental governance, and pollution governance, particularly, is not new at the international level. Since 1987, international, intragovernmental documents have stated the importance of recognizing, incorporating, and/or protecting Indigenous peoples, rights, and knowledge related to environmental governance (Supplementary Table S1). This trend continues in plastics pollution governance today (e.g., Norwegian Forum for Development and Environment, 2020; Collins et al., Reference Collins, Muncke, Tangri, Farrelly, Fuller, Borrelle, Hosseni, Rokomatu, Emmanuel, Adogame, Torres, Aneni, Villarubia-Gomez, Ballerini and Thompson2022; Lee, Reference Lee2022). There are many reasons for calls and declarations for Indigenous participation in environmental governance, including the recognition of Indigenous rights to governance (Carmen and Waghiyi, Reference Carmen and Waghiyi2012; Norwegian Forum for Development and Environment, 2020), the disproportionate burden of pollution on Indigenous peoples (LaDuke, Reference LaDuke, Lobo, Talbot and Morris2010; Fernández-Llamazares et al., Reference Fernández‐Llamazares, Garteizgogeascoa, Basu, Brondizio, Cabeza, Martínez‐Alier, McElwee and Reyes‐García2020; Aker et al., Reference Aker, Caron-Beaudoin, Ayotte, Ricard, Gilbert, Avard and Lemire2022; DuBeau et al., Reference Dubeau, Aker, Caron-Beaudoin, Ayotte, Blanchette, McHugh and Lemire2022; Rodríguez-Báez et al., Reference Rodríguez-Báez, Medellín-Garibay, Rodríguez-Aguilar, Sagahón-Azúa, Milán-Segoviaa and Flores-Ramírez2022), notable evidence that Indigenous stewardship is successful at protecting environments (Bendell, Reference Bendell2015, pp. 26–27; Garnett et al., Reference Garnett, Burgess, Fa, Fernández-Llamazares, Molnár, Robinson, Watson, Zander, Austin, Brondizio, Collier, Duncan, Ellis, Geyle, Jackson, Jonas, Malmer, McGowan, Sivongxay and Leiper2018; Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Taylor and Crease2021), and how “Our [non-Indigenous] privileged western perspectives can and have created blind spots in our work that can negatively impact the people and communities with whom we partner” (Ocean Conservatory, 2022; also see Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), 2015, 2022; Pulido, Reference Pulido2015, Irons, Reference Irons2022; McVeigh, Reference McVeigh2022).

However, participation is an unspecific term and has been interpreted in diametrically opposing ways. Moreover, it is well-documented that colonialism can be perpetuated through environmental research and management, and Indigenous peoples routinely face struggles “in trying to engage in and transform existing [environmental] governance and management approaches, as well as the adverse effects they experienced because of inequitable institutional arrangements, lack of resources, and failure to recognize Indigenous values …. More than 30 per cent of studies [on Marine Planning Areas] identified that Indigenous people could not meaningfully participate in marine planning and management strategies due to poorly designed and exclusionary policies and planning processes” (Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Taylor and Crease2021, p. 14; also see Rayne, Reference Rayne2008; Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), 2015; Manglou et al., Reference Manglou, Rocher and Bahers2022). Indeed, “the power dynamics currently driving plastics pollution prevention decision-making in Te Moananui [Pacific Island nations] … remains a by-product of colonial relations” (Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Ngata, Borrelle and Farrelly2022, p. 542) that mere inclusion cannot successfully address.

As such, this report offers a review of terms, models, and characteristics of Indigenous participation in plastic pollution governance with the goal of outlining modes of participation that are likely to be most successful and meaningful (see also Gaudry & Lorenz, Reference Gaudry and Lorenz2018). We end with a synthesis of Indigenous theorizations of and approaches to plastic pollution management, research, and mitigation. The review shows that Indigenous approaches to plastic pollution governance are often fundamentally different than mainstream, Western scientist, settler government, non-Indigenous environmental NGO, and industry-sponsored approaches while also showing areas of overlap and opportunity.

Methods

Position statement

A researcher’s positionality – their locations in various power structures, histories, and legacies – matters to research (Haraway, Reference Haraway1989; Takacs, Reference Takacs2003; Holmes, Reference Holmes2020; Hurley and Jackson, Reference Hurley and Jackson2020; Blue et al., Reference Blue, Bronson and Lajoie-O’Malley2021). Indeed, one of the findings of this review is that authorship impacts the types of Indigenous participation authors engage in and advocate for (Table 3 and figure 3). While this is a global review, it certainly happens from a place and context, which influence the results.

Max Liboiron is Red River Metis (Michif) and settler who grew up in Treaty 6 territory but now lives and works on the homelands of the Beothuk and Mi’kmaw on the island of Newfoundland, Canada. As a natural scientist working in partnership on plastic pollution in Inuit foodways and homelands in Nunatsiavut as well as a social scientist practicing Indigenous Science and Technology Studies, they have written extensively about the relationship about plastics pollution and colonialism from a Canadian perspective (e.g., Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2015; Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021a).

Riley Cotter is a settler who was born and raised in a rural community on the homelands of Beothuk and Mi’kmaw on the island of Newfoundland, Canada. As a graduate student at Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador, most of his post-graduation research has taken place in the Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research (CLEAR) on a variety of projects ranging from literature reviews to plastics wet lab work funded by the Nunatsiavut Government, Miawpukek First Nation, and NunatuKavut Community Council.

Scoping review

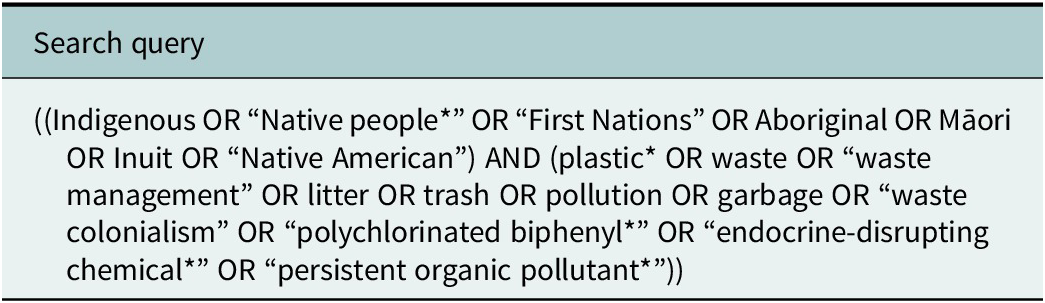

Our approach to this extensive scoping review on Indigenous participation in plastic pollution governance was inspired by Parsons et al.’s excellent study, “A Systematic Review of the Literature on Indigenous Peoples’ Involvement in Marine Governance and Management” (Reference Parsons, Taylor and Crease2021). Using the search string outlined in Table 1, we used the Google search engine, Google Scholar, ProQuest, and SCOPUS databases to locate texts focused on Indigenous participation in plastics and waste governance. ProQuest was selected as the primary repository for social scientific literature, and SCOPUS for its focus on STEM research. For these databases, we searched titles, keywords, and abstracts. The two Google engines were chosen to locate gray literature and news items.

Table 1. Search strings employed according to each database included in the literature review

Articles were excluded if they focused on deficit or harm-based models where Indigenous peoples were primary understood as victims without recourse to any form of participation or agency (Tuck, Reference Tuck2009), or if the research did not substantively include plastics pollution.

As a scoping review, we used saturation as the stopping rule. The search concluded when results were repetitive to literature already in the corpus. Google search engine searchers ended when news stories began to repeat the same case or event. For scholarly databases, there was a thinning effect where articles began the deviate from the core search terms, and/or contained only passing mentions of Indigenous peoples and did not add to the discussion of participation. Some excluded papers are still cited for context or analysis, but they are not in the corpus figures.

Each text in the corpus was read in its entirety at least once, and discussions pertaining to participation were highlighted. The indigeneity of a text’s authors was sought, either from introductions within the text itself or through professional biographies found via Google searches. The texts were coded in terms of the ways Indigenous participation was described (“terms of participation”) and enacted (authorship and author order). Codes were developed in a grounded approach, starting with the exact term used in the text (including phrases), and when similar types of participation were described with different terms, these terms were often combined. For example, the participatory term “opposition” includes sub-terms such as “fight,” “blockade,” and “challenge.” However, when the stake of an exact term used was assessed to be crucial to the message, the term stayed in the exact form in which it was used. For example, “seat at the table,” “free, prior, and informed consent,” and “get out of the way of Indigenous communities” were all left as-is and have quotation marks to demark a direct quote.

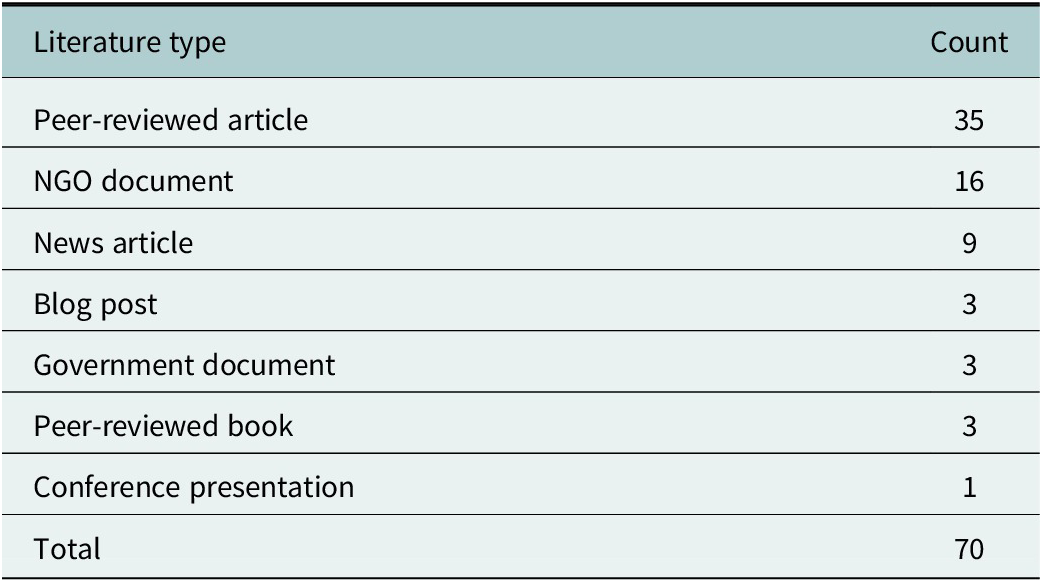

The corpus

Our search returned 70 texts, half of which were peer-reviewed articles, followed by 23% NGO or IGO reports (Table 2). Most literature focuses on plastic pollution as solid waste through a municipal solid waste (MSW) management lens, but some others discuss endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and other plasticizers (e.g., Shadaan and Murphy, Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020; Rodríguez-Báez et al., Reference Rodríguez-Báez, Medellín-Garibay, Rodríguez-Aguilar, Sagahón-Azúa, Milán-Segoviaa and Flores-Ramírez2022).

Table 2. Types of literature captured by the plastic-specific literature review

Note: Government and NGO documents include releases, reports, and websites.

Abbreviation: NGO, non-government organization.

Our corpus has a concentration of cases and authorship from Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Australia, and the United States (CANZUS), mainly because of the language of the search (Figure 1), largely because our search terms were English. But this is also because there is scarce literature on Indigenous peoples throughout Asia, Russia, the Arctic outside of Canada and the USA, South America, and Africa. A similar scoping review found that “50.7% of all studies linking pollution and IPs [Indigenous peoples] have been conducted among only 15 different Indigenous groups” with nearly half in North America (Fernández-Llamazares et al., 2020, p. 325). Another potential reason for the skew is that in the Global south, especially in Asia and Africa, the term “Indigenous” is not common or is rejected outright at the community and/or state level (Chineme et al., Reference Chineme, Assefa, Herremans, Wylant and Shumo2022; Senekane et al., Reference Senekane, Makhene and Oelofse2022).

Figure 1. Map of locations discussed in the corpus. Indigenous authors (individuals and organizations) are dark orange, mixed author lists where the first author is not Indigenous but at least one author is Indigenous are pale orange, and all non-Indigenous authored texts (individuals and organizations) are blue. Texts about the Global South, the entire Arctic, or with a global scope are not included (n = 19). Some points of the map are specific locations (e.g. “Aamjiwnaang First Nation”), while others occur in the middle of a much greater area (e.g. “Labrador Sea” or “Greenland”).

But the greatest skew in the corpus comes from the method of a literature review itself. Library scientists Anderson and Christen write that “authorship [is] both a site of colonial power and as one of settler colonialism’s flexible legal devices for maintaining control and possession of knowledge” (Anderson and Christen, Reference Anderson and Christen2019, p. 123). This means much Indigenous knowledge (IK) and participation is not published and is thus illegible to Western academic literature review practices. While we attempted to capture news stories, blogs, and reports to broaden this bias, our search methods still privilege the written word in digital format.

Indigenous participation in the corpus itself

We coded the corpus of 70 texts in terms of how texts enacted Indigenous engagement in the texts themselves (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S2).

Table 3. Comparison of inclusion types in plastic-specific literature review contents according to authorship

Note: Comparison of enacted inclusion in plastic-specific literature review contents, including authorship. The “actual” category includes texts where Indigenous leadership is apparent in the text itself, either through Indigenous first-authorship (individual or organization) or through news stories focused on Indigenous nations or Indigenous-led initiatives or projects. It does not include anthropological or other social science studies of Indigenous peoples by non-Indigenous authors. The “meaningful” category indicates that the main thesis of the text includes Indigenous peoples/theories/rights in a thoughtful, detailed, and/or reflexive manner, demonstrating fluency and commitment to ideas of Indigenous participation. This category does not evaluate the types of Indigenous participation discussed, just the extent of discussion. Texts categorized as “discursive” mention Indigenous participation in the text but we could not determine the extent, mode, or impacts of this participation in the text. “Marginal” texts briefly mentioned Indigenous peoples’ inclusion in passing in a way that was not central to the method, argument, or findings, and often appeared in footnotes, acknowledgements, or in a sentence in the conclusion or introduction. The “Indigenous” authorship category reflects Indigenous first authors (individual or organization). “Mix” refers to author lists with a non-Indigenous lead with at least one Indigenous author. It is customary in Indigenous-focused research to introduce yourself as a researcher and your positionality (Hurley and Jackson, Reference Hurley and Jackson2020), including your relationship to specific Indigenous Nations and communities. Thirty-one (44%) of texts in the corpus did not do this, nor did looking up individual author bios online indicate whether the authors were Indigenous or not. These author lists are marked as “unknown.” Given the consistent tendency for Indigenous researchers to introduce themselves according to their nation or community of belonging, and the “unmarked” position being a position of privilege (Beauvoir, Reference Beauvoir, Borde and Malovany-Chevallier2010; Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021a), we can assume most of these authors are not Indigenous (“non-Indigenous and unknown” category), though we keep the categories separate in the table for transparency.

The largest share of modes of Indigenous participation in the corpus was “actual participation” (44%), where Indigenous people are central to crafting the document, either through first authorship or in news stories that focus on what Indigenous nations, communities, organizations, or individuals are doing (Table 3). All texts in the “actual” category would also fall into the meaningful category (below) where texts had robust engagement with models and modes of Indigenous participation. Eighteen of the 31 actual texts had Indigenous first authors (60% of the category and 26% of the corpus). First authorship is characterized by decision-making power over the message overall, as well as components of research design, questions being asked, analysis, and how the benefits of authorship accrue to authors (Anderson and Christen, Reference Anderson and Christen2019). This is slightly higher compared to a similar study conducted by Parsons et al. where 21% of texts had at least one Indigenous co-author (2021, p. 13). Our corpus had a total of 28 (40%) texts with a combination of Indigenous-led and mixed author lists. However, like Parsons et al. (Reference Parsons, Taylor and Crease2021), our corpus suffers an overrepresentation of non-Indigenous authors (60% of texts, and more if we count individual authors), meaning most research on Indigenous participation in plastics pollution governance is still characterized by an “about us without us” approach (Figure 1).

“Meaningful inclusion” was advocated for in 29% of the corpus, where Indigenous peoples, rights, and/or theories were engaged with in a sustained and thoughtful manner, showing familiarity or fluency in the topics (Table 3). This category does not differentiate between different modes or models of participation, which are discussed more below. Most authors in this category (89%) were non-Indigenous or unmarked.

Discursive participation (13% of the corpus) describes texts where authors stated participation of Indigenous peoples or leadership, but there were no indications as to what this entailed, its extent, or its impact (Table 3). That it, participation was stated but not demonstrated, and engagement with theories, concepts, or methods of Indigenous participation are not present enough to be included in the “meaningful participation” category. Only one of these texts had an Indigenous author (not first author). Another term for this category is tokenism, where the goal of Indigenous inclusion is simple inclusion itself, a symbol of participation, rather than a form that requires changes in structure, content, or outcome.

Marginal texts made up 24% of the corpus (Table 3). These included brief statements that Indigenous people, methods, theories, jurisdiction, or knowledges should be or were recognized. For example, this included statements such as “While not the focus of this review, in settler colonial contexts … deep consideration should also be given to … forms of environmental pollution and more-than-human environmental (ill)health” pertinent to Indigenous peoples (Alda‐Vidal et al., Reference Alda‐Vidal, Browne and Hoolohan2020, p. 12, endnotes). In another case, a plastic pollution study noted it had received Indigenous post hoc permission to conduct research in a land claim area but no further participation was noted (Mallory et al., Reference Mallory, Baak, Gjerdrum, Mallory, Manley, Swan and Provencher2021). None of these texts included Indigenous authorship of any kind.

Terms of participation

We coded 229 terms used to describe Indigenous participation in the corpus (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S3). These terms were obtained by close reading rather than automated word searches to ensure the terms were in relation to Indigenous participation (e.g., rather than calls for settler state governments to be accountable to the general public). The most common term was opposition (n = 16, 7.0% of the corpus), which referred to Indigenous-led activities described as “challenges,” “fighting,” “blockades,” and other forms of engagement outside of formal governance structures that tend to be used when governance structures fail. Even though the corpus focused on formal governance, the failure of governance and the actions it can engender was still the most remarked upon type of Indigenous participation in plastics governance. It was commonly evoked by both Indigenous authors and organizations and non-Indigenous or unmarked authors, but more rarely by mixed author groups and never by settler governments and NGOs (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Terms of participation arranged by frequency of use and authorship in the corpus. The number of times a term was used to describe Indigenous participation in the corpus, colour coded by which actor group authored the text that used the term. The graph includes only terms used two or more times. For a full list of terms, see Figure S1 in supplementary material. Usage is colour-coded by the type of actor who authored the text. Dark orange includes Indigenous organization authors as well as news stories that cover Indigenous organizations. Light orange indicates an Indigenous first author. Grey includes mixed author lists where Indigenous people were not first authors. Light blue denotes non-Indigenous authors and those for whom no introduction or biography indicated their indigeneity. Dark blue indicates authors were non-Indigenous institutions such as state governments or NGOs.

At this stage of analysis, it became clear that different actors were using terms of participation in noticeably different frequencies and contexts, and an overall count of a single term is not as useful as analyzing which terms of participation are being mobilized by which actors in accordance to their indigeneity, partnerships, and relative power (Figure 3). However, some terms were more promiscuous and used by all four of the actor groups (Figure 2). These included partner/partnership (n = 12), rights (n = 8), recognize/recognition (n = 6), and participation (n = 6). No other terms were used by all five actor groups.

Figure 3. Frequency of participatory terms used by author type. Treemap of most frequently used terms to describe Indigenous participation in plastics pollution governance, arranged by author/actor type. The larger and darker the section, the more frequently the term was used. Relative size of each segment for an actor group is independent of the others, meaning that the largest, darkest section does not always represent the same frequency across groups. The top count is noted in the corresponding segment.

It is telling that the most frequently used term by each author group tends to define the model of participation of the group (Figure 3). Indigenous-led texts spoke about opposition the most. Mixed author groups mentioned partnership most often. Non-Indigenous and unmarked authors most frequently spoke of Indigenous participation trough collecting data from Indigenous people. And non-Indigenous governments, intergovernmental- and non-governmental organizations most often spoke of “recognition,” often in abstract terms without defining what recognition meant beyond a general acknowledgement and inclusion as a special interest group.

Each group’s most frequently used terms tended to cluster. Indigenous-led texts focused on Indigenous leadership through the creation of new organizations, collaborations, partnerships, and business or jobs, and often evoked sovereign rights. This is the only group that discussed co-authorship, dismantling colonial structures, and “getting out of the way of Indigenous communities” as modes of Indigenous participation. They are the only group that did not use the otherwise popular terms empowerment, incorporate, or engagement (see Figure 2 as well).

Mixed author groups led by non-Indigenous authors also spoke about rights but tended to focus more strongly on modes of shared engagement, such as partnership, co-development, co-management, and collaboration. While decision-making was among the top terms, so too were “collect data from Indigenous people” and “incorporate,” which tends to characterize Indigenous decision-making power that is not based on leadership (there are no Indigenous first authors in this group). This indicates that decision-making is not necessarily equated with leadership or sovereignty in all understandings of partnerships.

Texts authored by non-Indigenous and unmarked authors had an interesting split in the main terms to describe Indigenous participation. Most strongly, Indigenous people were outside the team as either sources of data or social movements that were opposing dominant structures of governance. Yet this was followed by collaborative terms such as collaboration, participation, and “working with.” However, none of these terms were taken up to the point of including Indigenous peoples in the author list or using the protocol of introduction or position statements in research (Hurley and Jackson, Reference Hurley and Jackson2020). This schism is also reflected in our categories of enacted participation of texts: the “discursive” category came about precisely because there was a notable gap between the terms used to describe and advocate for Indigenous participation, but there was no demonstration of the enactment of that participation (Table 3).

Non-Indigenous organizations including governments, IGOs, and NGOs have considerably more power than independent authors. This group had relatively few texts compared to the rest of the corpus (n = 19, 27%), and tended to discuss Indigenous participation either briefly or with repetitive terms (if the same term was used multiple times in one document, it was counted as one instance. Otherwise, “rights” would be the most frequently used term in the corpus because of legal documents with extreme repetition). Recognition and consideration were two of the top terms for this group, reflecting Franz Fanon’s argument that when recognition occurs within structures of colonial dominant, the terms of accommodation, recognition, or accountability are determined by and in the interest of the colonial actors in the relationship. That is, recognition is part of a structural problem of ongoing colonization (Fanon, [1952]/Reference Fanon2008; Coulthard, Reference Coulthard2014). This is how a “seat at the table” can be interpreted. At the same time, there was a notable overlap in the importance of employment/entrepreneurship between this group of texts and Indigenous-authored texts.

Models of Indigenous participation

Terms cluster into three main models of Indigenous participation in the corpus: inclusion, where Indigenous peoples, representatives, or knowledge are added to existing processes, groups, or frameworks; rights and sovereignty, two related approaches that frame Indigenous participation in terms of rightsholder status and the right to self-determination and self-governance; and Indigenous Environmental Justice (IEJ), which overlaps with rights and sovereignty but is additionally characterized by the ability for Indigenous peoples to exercise traditional, decolonial, anticolonial, and Indigenous theories, obligations, law, and cosmologies in land relations, including governance. While these three models overlap in various (but not exhaustive) ways, they are described separately here to maximize their usefulness to understand, evaluate, or build participatory structures (see also Gaudry & Lorenz, Reference Gaudry and Lorenz2018).

Inclusion

Inclusion terms were both numerous and various, and used by all actor groups, but most strongly by non-Indigenous authors, NGOs, IGOs, and governments. Terms such as “a seat at the table,” recognition, and acknowledgement are inclusion terms, as are “voice” related terms like testimony, listen, and meet. Inclusion is often critiqued by Indigenous peoples when it is the primary goal of participation (i.e., once Indigenous peoples are included, efforts to Indigenize a process are complete). Indigenous people describe this as “inclusion into empire” (Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021b), “add Indigenous and stir” (CBC, 2017; Littlechild et al., Reference Littlechild, Finegan and McGregor2021), “tokenism” (Belfer et al., Reference Belfer, Ford, Maillet, Araos and Flynn2019), or “the politics of [settler] recognition” (Coulthard, Reference Coulthard2014) because many forms of inclusion maintain the dominance and centrality of non-Indigenous goals, knowledges, governance structures, and processes (Tsosie, Reference Tsosie, Lorusso and Winther2021). As we have argued elsewhere, “the opposite of colonialism is not inclusion. Adding more Indigenous texts to a syllabus [or Indigenous people to a committee] neither impacts land relations nor changes the dominant knowledge paradigm. In fact, using IK to enrich non-Indigenous learning has been a core component of colonial knowledge systems that require local knowledge to survive and flourish on colonized land” (Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021b, p. 876). This is not to say that inclusion is inherently unmeaningful. Rather, it is a necessary but fundamentally insufficient step to achieve meaningful and impactful Indigenous participation.

Many Indigenous people value being included in forums such as those provided by the United Nations and for the emerging plastics treaty (e.g., Adeola, Reference Adeola2000). Researchers relate how “Indigenous leaders express frustration and disappointment at being excluded from past United Nations Environment Assembly Ad-Hoc Open-ended Expert Groups (UNEA AHEG) on marine litter and microplastics, in part, due to a lack of facilitation to support travel from Te Moananui including visas and funding” (Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Ngata, Borrelle and Farrelly2022, p. 551).

At the same time, Indigenous youth representative “Michael Charles, part of a delegation of youth climate justice leaders, noted, ‘We know that if we show up, we become tokenized and people think that’s an adequate voice, but if we don’t show up, we also recognize that there will be no voice and no one else to step in’” (Belfer et al., Reference Belfer, Ford, Maillet, Araos and Flynn2019, p. 24). Inclusion in some forums can also exclude Indigenous people from other forms, such as where platforms such as the UN Forum “have siloed Indigenous voices into one body (the Indigenous Peoples Major Group), thus limiting their access to other decision-making spaces” (Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Ngata, Borrelle and Farrelly2022, p. 551). Finally, inclusion does not guarantee decision-making power, and international or intra-governmental forums are often beholden to the settler state, falling “short of supporting Aboriginal self-determination” (McGregor, Reference McGregor2010, p. 75).

Yet, “despite these constraints, important opportunities motivate participants to continue to engage in these fora: opportunities for agenda-setting, the ability to access high-level ministers and influence both international and national policy, the opportunity to meet and collaborate with other IPs through the caucus, alliances with CSOs” (Belfer et al., Reference Belfer, Ford, Maillet, Araos and Flynn2019, p. 27). This is the root of ambivalence: to be included is crucial, but insufficient for the types of participation that can enable us to reach our goals.

A core example of ambivalent inclusion is the case of IKs or traditional knowledge (TK). IKs were mentioned regularly in the corpus. Yet, the mode of engagement around IK is highly variable. In several texts, the call to include IK appeared without the simultaneous inclusion of Indigenous peoples (e.g., United Nations Environment Assembly of the United Nations Environment Programme, 2021–22, p. 3; Collins et al., Reference Collins, Muncke, Tangri, Farrelly, Fuller, Borrelle, Hosseni, Rokomatu, Emmanuel, Adogame, Torres, Aneni, Villarubia-Gomez, Ballerini and Thompson2022). Sometimes, the presence of Indigenous people in an author group is conflated with access to IK (AMAP, 2022). Most Indigenous authors agreed that “simply taking or ‘extracting’ TK from the community and inserting what is deemed relevant into environmental management regimes (the ‘knowledge extraction paradigm’) is an approach that is failing all parties” (McGregor, Reference McGregor2014, p. 498). That is, mere inclusion is not only insufficient as a mode of engaging with IK but is not actually how IK works as a complex, place-based, intergenerational system of knowledges. It is not data.

At the same time, Indigenous authors and activists have noted the acute success of sharing IK when it is understood as a system of knowledge through relationships, ethics, and protocol. Deborah McGregor has written about how “current State–First Nation discussions in this area [policy on water pollution] are focused primarily on the techno-fix, the regulatory/legislative fix, and aboriginal and treaty rights. In part, framing the policy research on water within a TK framework resulted in the expansion of this prevailing narrative to include fulfilling responsibilities to the natural world” (McGregor, Reference McGregor2014, p. 494). That is, when done correctly, robust inclusion changed the terms of engagement for the entire process, and not just for Indigenous participants. Caught between these forces, there is a “cautious willingness by First Nations to share TK” (McGregor, Reference McGregor2014, p. 497). This review has shown this cautiousness is warranted.

Rights and sovereignty

Indigenous peoples are rightsholders, not stakeholders. Parsons et al. (Reference Parsons, Taylor and Crease2021) noted that “a common critique raised by Indigenous peoples was that government officials treated them (Indigenous tribes, peoples, nations) as if they were just another ‘stakeholder’ that the government needed to consult with, rather than an Indigenous nation who possessed sovereignty, rights, and responsibilities for their ancestral lands and waters beyond that of mere ‘stakeholders’” (2021, p. 15). This trend is repeated in the plastics pollution corpus, and some authors explicitly misidentify Indigenous peoples as stakeholders (e.g., Butler et al., Reference Butler, Gunn, Berry, Wagey, Hardesty and Wilcox2013; Ren et al., Reference Ren, James, Pashkevich and Hoarau-Heemstra2021). Many others are less explicit and use terms of inclusion that describe stakeholder participation (a group with a general or vested interest) such as “consideration” or “inclusion” rather than terms appropriate rightsholder participation (a group with an inherent, fundamental, and indisputable entitlement) such as “decision-making” or “sovereignty.”

Other texts in the corpus explicitly foreground a rights-based approach to participation, for example, arguing that, “Arctic Indigenous people should be designated as ‘rights holders’ instead of stakeholders. Stakeholders for Arctic discussions include many different interest groups, industries, and organizations” (Schlosser et al., Reference Schlosser, Eicken, Metcalf, Pfirman, Murray and Edwards2022, p. 5) or call to “prioritiz[e] the perspectives of [I]ndigneous caregivers, rather than the concerns of settler-colonisers and commercial companies” (Environmental Investigation Agency, 2022). Terms such as “rights,” “free, prior, and informed consent,” and “treaty” were common terms in the corpus for this framework, particularly, in texts with Indigenous first-authors. Many of these terms and phrasing come from the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP; e.g., Lusher et al., Reference Lusher, Provencher, Baak, Hamilton, Vorkamp, Hallanger, Pijogge, Liboiron, Bourdages, Hammer, Gavrilo, Vermaire, Linnebjerg, Mallory and Gabrielsen2022, pp. 2–3; Norwegian Forum for Development and Environment, 2020, p. 17. Also see Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Garba, Figueroa-Rodríguez, Holbrook, Lovett, Materechera, Parsons, Raseroka, Rodriguez-Lonebear and Rowe2020; First Nations Information Governance Centre, 2023).

Treaties are also mentioned. Some of these reference post-contract treaties held between settler and Indigenous nations (e.g., Chisholm Hatfield, Reference Chisholm Hatfield2019; Shadaan and Murphy, Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020), which are designed as binding legal contracts (though these are rarely upheld) while others specifically refer to the UN Treaty on Plastic Pollution, designed to be “an international legally binding instrument” with a provision for “The best available science, traditional knowledge, knowledge of indigenous peoples and local knowledge systems” (United Nations Environment Assembly of the United Nations Environment Programme, 2021–22, pp. 1 and 3; also see Adeola, Reference Adeola2000; Schlosser et al., Reference Schlosser, Eicken, Metcalf, Pfirman, Murray and Edwards2022).

Rights and sovereignty overlap, but Indigenous sovereignty is more extensive and specific than rights. Indigenous rights are fundamental entitlements given to Indigenous peoples as first peoples, and these rights are granted and recognized (or not) by settler and colonial states. That is, they are premised on settler state recognition (Fanon, Reference Fanon2008; Coulthard, Reference Coulthard2014), and therefore, stem from what is legible, valuable, and allowable to the settler state. Indigenous sovereignty, on the other hand, is the expression of Indigenous nationhood inherent in our collective histories, laws, cosmologies, and communities and is synonymous with self-determination. A sovereignty approach to participation in plastic pollution governance is based on Indigenous autonomy and self-determination so that “key ideas, concepts, and principles that constitute the foundation of Indigenous laws and codes of conduct, including specific direction on how people are to relate to all of Creation” structure the nature of participation at every stage (McGregor, Reference McGregor2018, p. 11; also see Borrows, Reference Borrows2010). Terms in the corpus that align with this mode of participation including the explicit use of sovereignty and self-determination as well as ownership, control, decision-making, and community-led. Both rights-based and sovereignty governance requires the capacity to make decisions and have ownership over processes and projects, which in turn requires material conditions (infrastructures) to enable decision-making and ownership.

The most common way this manifested in the corpus was through Indigenous-led waste management and plastic governance within existing Indigenous legal jurisdictions such as land claim areas, tribes, bands, iwis, or nations (e.g., IZWTAG, n.d.; Para Kore, n.d.; The Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaw, n.d.). The corpus and affiliated literature were clear that at this scale of governance, infrastructure was essential, whether that meant solid waste infrastructure (Seeman and Walker, Reference Seeman and Walker1991; Bharadwaj et al., Reference Bharadwaj, Nilson, Judd-Henrey and Ouellette2006; Njeru, Reference Njeru2006; Eisted and Christensen, Reference Eisted and Christensen2011; Seemann et al., Reference Seemann, McLean and Fiocco2017), or supply chain infrastructure that enabled non-plastics to be a viable material option in a community (Seemann et al., Reference Seemann, McLean and Fiocco2017; BC Gov News, 2022; Gascón, Reference Gascón2022). For instance, if an Indigenous community had no potable water, the choice not to use disposable plastic packaging was not available (BC Gov News, 2022). Less often, Indigenous sovereignty over plastic and other forms of pollution included Indigenous nation- to nation-legal frameworks, such as the water declaration of the Anishinaabek, Mushkegowuk, and Onkwehonwe (Cheifs of Ontario et al., Reference Chiblow and Dorries2007).

Indigenous Environmental Justice (IEJ)

In our view, the ultimate indicator of whether Indigenous participation in plastic pollution governance is meaningful enough is whether processes and end results have to have the capacity to produce IEJ. McGregor writes that “achieving IEJ will require more than simply incorporating Indigenous perspectives into existing EJ theoretical and methodological frameworks (as valuable as these are). Indigenous peoples must move beyond ‘Indigenizing’ existing EJ frameworks and seek to develop distinct frameworks that are informed by Indigenous intellectual and traditions, knowledge systems, and laws” central to which is our relationships to non-human kin (Borrows, Reference Borrows2010; McGregor, Reference McGregor2018, p. 11).

In the first instance, this requires that participation does not replicate colonial structures of power. Tina Ngata argues that “plastic pollution, like climate change, was just another form of colonization upon our bodies and territories: an uninvited intrusion driven by people with a supreme sense of entitlement. This meant, for me, that ‘turning [plastic] off at the tap’ didn’t mean changing policy as it does for most, it meant exposing, and dismantling, the racist and imperialist nature of plastics pollution” (Ngata and Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021, p. 4). If we understand how “pollution is not a manifestation or side effect of colonialism but is rather an enactment of ongoing colonial relations to Land” (Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021a, p. 7), then we can extend this understanding to pollution governance as well. Management and governance of plastics can reaffirm non-Indigenous access to, control of, and benefit from Indigenous lands, for instance, even if they somehow include Indigenous peoples.

Within IEJ, the terms of plastics pollution are articulated in fundamentally different ways than mainstream and non-Indigenous framings, and thus solutions, management, and mitigations look different as well. Specifically, it addresses environmental pollution from a “culturally relevant framework that emphasizes the sacredness and interconnectedness of the land, and the subsequent need to restore and protect it” (Akwesasne Task Force on the Environment, 2023). For example, Māori researcher Tina Ngata writes that, “When I re-indigenize the framing of plastic pollution, it leads me to understanding plastic as a disruptor of whakapapa” (Ngata and Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021, p. 4). Anishinaabe legal scholar John Borrows states that pollution interferes with “dibenindizowin (the freedom to live well with others). Dibenindizowin ‘implies that a free person owns, is responsible for, and controls, how they interact with others’” (McGregor, Reference McGregor2018, p. 14). Whakapapa and dibenindizowin are not identical, but both frame plastics pollution in terms of lifeways and obligation to those lifeways, which is a departure from common articulations of the issue. Indeed, when the Ministry for the Environment, Wellington compared their own indicators of freshwater health to those created by kaumātua, the non-Indigenous researchers provided eight indicators and kaumātua provided 29, only four of which overlapped (Tipa and Teirney, Reference Tipa and Teirney2006). Inclusion of Indigenous people via “voice” or presence may allow these terms (Whakapapa, dibenindizowin, or kaumātua indicators) to appear in management documents, but not an understanding of how to carry them out, which is required for governance.

Indigenous-based frameworks for understanding plastic pollution

In his work on climate change, Amitav Ghosh theorizes that elite research on climate change and the phenomenon of climate change have become synonymous, despite the vastness of the event and the myriad ways of knowing about climate change (Ghosh, Reference Ghosh2021). We would argue that the same has occurred for plastics pollution: Western, non-Indigenous, and elite research has overdetermined and restricted what plastic pollution is, and thus, how it might be governed. We conclude our review by outlining some of the characteristics of how plastic pollution is understood in the corpus. Indigenous authored texts are used to frame this overview, though all texts in the corpus are used to describe them. They are presented under discrete headings, but they usually appeared together synergistically. They’ve been separated here for ease of understanding.

Relationships first: Plastic pollution disturbs relationships and obligations

One of the core characteristics of Indigenous-led descriptions of plastic pollution was how it “disrupt[s] the ability of communities to maintain kinship and obligations to land, food, and nonhumans” resulting, in turn, of the challenging of Indigenous communities to “maintain ‘collective continuance’ (as per Whyte, Reference Whyte2014) and ‘mutual flourishing’ (as per Kimmerer, Reference Kimmerer2013)” (Shadaan and Murphy, Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020, pp. 10, 16; also see Luginaah et al., Reference Luginaah, Smith and Lockridge2010; McGregor, Reference McGregor2010; Chisholm Hatfield, Reference Chisholm Hatfield2019; Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Ngata, Borrelle and Farrelly2022, p. 540). McGregor explains that “First Nations are not simply concerned about water [quality], but have specific responsibilities to protect water. Aboriginal peoples’ responsibilities and obligations to water extend to all of Creation, the spirit world, the ancestors and those yet to come; and all must be considered when contemplating actions that will affect water” (McGregor, Reference McGregor2014, p. 501) polluted by plastics and other contaminants. This understanding of pollution leads to very different governance than what is common in the mainstream. For instance, plastic pollution of this kind is not addressed by legislated threshold limits for plastics or endocrine distrusting compounds (Durie, Reference Durie1999; Shadaan and Murphy, Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020; Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021a).

Food sovereignty was a core example of the way plastics impact relationships (e.g., Ngata and Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021; CBC Gem, 2022; Lusher et al., Reference Lusher, Provencher, Baak, Hamilton, Vorkamp, Hallanger, Pijogge, Liboiron, Bourdages, Hammer, Gavrilo, Vermaire, Linnebjerg, Mallory and Gabrielsen2022). Indigenous food sovereignty is not just about access to traditional food, but about the complex set of relationships and obligations to families, the community, non-humans, land, language, and the food itself. For example, Tina Ngata has spoken about the impacts of plastic contamination of wild food as well as the import of plastic packaging on hosting (Ngata and Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021). Others have written about how when food advisories due to EDCs in wild food cause people to stop fishing, then people stop tying traditional knots, stop using the words to refer to them, and stop going to the river together, all of which have acute impacts on culture beyond just nutrition.

Colonialism at the source: Global trends of colonial power in plastic pollution

Indigenous-led articulations of plastics pollution usually included global structures and scales of colonialism while also dealing with the diverse specificities of place and peoples. Indigenous-led writing rarely engaged with concepts of precautionary consumption, individualized action, or technical fixes, and instead understood plastic pollution as part of colonial systems. For instance, Ngata and Liboiron (Reference Liboiron2021) write that, “From an anti-colonial perspective, plastic pollution demands us to analyze and dismantle the harmful systems and perspectives that allow it to proliferate. This requires a focus on the international, trans-national, regional and domestic systems of colonial power that not only inform the problem, but also shape our responses to the problem” (p. 5). In a similar vein, Wagner-Lawlor (Reference Wagner-Lawlor2018) argued that “the waste crisis, particularly in cities and in the mega-metropolis, Lagos, is understood as a Western ‘invasion’ of Nigeria’s own social and physical ecologies: a disruption of a national oikos” (p. 200). A colonial understanding of plastic pollution includes not just disposal, but also extraction of oil and gas for the raw feedstocks of plastic production and the settler governance of both extraction and pollution from manufacturing: “Within the settler colonial infrastructures of the oil and gas industry – which includes both the corporate industrial structures and the state’s permission-to-pollute system of regulation – white, settler, and capitalist forms of life are promoted, and other forms of life, land, and sovereignty are disrupted” (Shadaan and Murphy, Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020, p. 10; also see CLEAR and EDAction, 2017; Mah, Reference Mah2023, p. 3). Put simply, plastic “pollution is colonialism” (Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021a, emphasis added).

Examples of what is often called waste colonialism or toxic imperialism in the corpus focused on: trans-boundary issues such as the export of plastic recyclables (and thus plastic pollution) from the global north to the global south (Adeola, Reference Adeola2000; Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2015; Michaelson, Reference Michaelson2021; Ngcuka, Reference Ngcuka2022); the neo-colonialism of oil and gas extraction specifically for plastic production in Nigeria by Global North colonial powers (Wagner-Lawlor, Reference Wagner-Lawlor2018); the export of Western or Northern loans and sponsored incinerators to the East and Global south for “their” plastic pollution problem (Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), 2015; Michaelson, Reference Michaelson2021; Ocean Conservatory, 2022); myopic scientific research that places “the responsibility for plastic waste solely on the shoulders of five Asian countries … while ignoring the role of Global North in plastic overproduction and waste exports” (Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), 2022; also see Adeola, Reference Adeola2000; Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), 2009; Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Ngata, Borrelle and Farrelly2022); and how plastic waste governance such as the Basel plastic amendments can replicate these colonial structures (Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Ngata, Borrelle and Farrelly2022, p. 546).

Place-based: Specificity and locality in the face of global trends

The focus on global trends of colonial power in the corpus simultaneously supported an emphasis on the places, nations, cultures, waters, communities, and Indigenous forms of governance unique to different Indigenous peoples. Pan-indigeneity, the idea of a single or universally coherent Indigenous way of being, has been criticized as a colonial tactic to restrict and control the diversity of our nations, languages, histories, and laws (Sandberg McGuinne, Reference Sandberg McGuinne2014). Moreover, indigeneity is “often expressed through place-based descriptions of relationships” and the term is “used to express intergenerational systems of responsibilities that connect humans, non-human animals and plants, sacred entities, and systems” of a particular land (Whyte, Reference Whyte, Adamson, Gleason and Pellow2016, pp. 143–144). Place matters to Indigenous concepts and actions concerning plastics, even in the face of global colonialism and pollution. One text articulated this as “starting from where you are,” meaning that knowing, talking to, and involving the specific Indigenous peoples of a place as well as “understanding your distinct colonial context” were necessary for plastics pollution work (Ngata and Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021, p. 2).

An Indigenous emphasis on specific land and nation often conflicts with modes of international participation when “the international scale and the limitations of observer status demand the creation of a relatively unified Indigenous negotiating bloc” such as at the scale of extra-governmental agencies like the United Nations, which creates the “challenge of responding to ongoing developments in the negotiation space, while reflecting the results of local and regional consultations and considering the needs and demands of colleagues with vastly different circumstances” (Belfer et al., Reference Belfer, Ford, Maillet, Araos and Flynn2019, p. 25; emphasis in original). Modes of participation and governance that can deal with place-based differences within and across Indigenous groups are important.

Moreover, plastics pollution itself is place-based and unique in different places despite its simultaneous global scale: “there is not a single plastic pollution […] plastic profiles, like dialects, are unique to their regions” (Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2020, p. 1). Studies have found that universal standards do not work for waste management, particularly, in rural and remote Indigenous communities (Seeman and Walker, Reference Seeman and Walker1991; Seemann et al., Reference Seemann, McLean and Fiocco2017; Johnson, Reference Johnson2019; Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Ngata, Borrelle and Farrelly2022; Manglou et al., Reference Manglou, Rocher and Bahers2022; Stefanovich, Reference Stefanovich2022). As such, some of the corpus focused on local and community solutions (e.g., The Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq, 2014; Asomani-Boateng, Reference Asomani-Boateng2016; Norwegian Forum for Development and Environment, 2020, p. 9) and governance.

Problem definition: Community-based and holistic definitions of health and harm

Indigenous peoples have described issues of health and harm related to plastic pollution in ways that differ greatly from non-Indigenous frameworks. In the corpus, this was expressed mainly by evaluating how plastics impacted place-based relationships and obligations (as above). But occasionally these concepts were explicit, particularly for the benefit non-Indigenous audiences. Non-Indigenous researcher Kurt Seeman explains that “The literature on health impacts associated with solid waste is focused on a Western biomedical interpretation of health, which is concerned with isolating the specific causes of physiological illness” (Seemann et al., Reference Seemann, McLean and Fiocco2017, p. 20). This interpretation of health is much narrower than the Indigenous interpretation of health, which encompasses the physical, social, emotional, and cultural wellbeing of the individual and the community as a whole (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Suina, Jäger, Black, Cornell, Gonzales, Jorgensen, Palmanteer-Holder, De La Rosa and Teufel-Shone2022). For example, in two Indigenous-focused studies on water quality, an indicator of both human and water health was the sound of birds (Durie, Reference Durie1999; Tipa and Teirney, Reference Tipa and Teirney2006).

Holism: “Plastics” pollution includes a range of extraction, production, and disposal activities and related root causes

Some texts in the corpus spoke about the frustration Indigenous peoples had when they expressed multiple concerns as connected, but were often understood as separate by outsiders (Narine, Reference Narine2021). As one collaborative team explains, “Most plastics pollution ends up in the environment so that Indigenous leaders must now deal with the impact of plastics leachates to arable soils, fishing grounds, and mangroves, impacting the local food systems, human and ecological health, cultural connections to land and sea, and community livelihoods (Leal et al., Reference Filho, Havea, Balogun, Boenecke, Maharaj, Ha’apio and Hemstock2019). Plastics pollution leakage is exacerbated by Te Moanaui’s exposure to weather extremes because of climate change. Winds, rain, and storm swells, rising sea levels, and frequent cyclones and storm surges disperse plastics easily into the environment, further threatening human health and ecosystems – the lands, oceans, air, and bodies of Te Moananui’s Indigenous peoples” (Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Ngata, Borrelle and Farrelly2022, p. 545). Likewise, texts that focused on water protection did not isolate plastics from other types of water pollution or the impacts of climate change on water (Adeola, Reference Adeola2000; Endres, Reference Endres2009; CLEAR and EDAction, 2017; MEWWS, 2017; Decolonizing Water, 2023). Other authors described a wider cacophony of environmental harms as the lived reality of how Indigenous peoples encounter colonialism’s impact on their world, looking at the cumulative and synergistic impacts of pollution, COVID-19, forest fires, and climate change (Chisholm Hatfield, Reference Chisholm Hatfield2019; Narine, Reference Narine2021).

When there was a focus on plastics pollution, it was common for Indigenous and some non-Indigenous authors to think about plastics pollution through its entire life cycle and structures of power (Seemann et al., Reference Seemann, McLean and Fiocco2017; Wagner-Lawlor, Reference Wagner-Lawlor2018; Ngcuka, Reference Ngcuka2022; Peryman, Reference Peryman2022; Mah, Reference Mah2023). For example, in their work on plastic additives such as phthalates and BPA, collaborators Shadaan and Murphy join “other researchers in pushing the study of EDCs back to fossil fuel and petrochemical industry production, and thus also extends out to extraction itself, including oil fields, fracking pads, mining pits, and tar sands…. This understanding of EDCs also expands to the wastelanding practices of settler colonialism and racial capitalism that accompany oil extraction and refining performed through the distribution of industrial and infrastructural emissions to airs, waters, and lands” (2020, p. 6). This approach was also common in critiquing some mainstream solutions to plastics pollution, particularly incineration. These critiques tied incineration to its own complex clusters of harm, from the burden of debt and operating costs to the “health and environmental impacts of burning so much waste” (Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), 2015, p. 2). More than merely opposing “end of pipe” solutions rather than targeting production, these critiques linked incineration to structures of imperial financing, climate change, and toxic colonialism (Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), 2015, 2022; Chisholm Hatfield, Reference Chisholm Hatfield2019).

Agents of a polluted status quo: The settler state and industry capture

Regulatory capture, sometimes also called industry capture or agency capture, refers to a type of corruption of authority where a regulatory or governance entity serves commercial or industrial interests rather than the general public or constituents (Dal Bó, Reference Dal Bó2006). This term was not used in the corpus, but several texts described the phenomenon:

“In March 2021, Coca-Cola stopped distributing glass bottles in Samoa in favor of plastic ones through a local distributor, putting pressure on the central and local government, and on communities to manage yet more plastic waste (Membrere, Reference Membrere2021). They are an example of ‘Big Plastics’ (Linnenkoper, Reference Linnenkoper2020), a major plastics producer with the power to dictate national policy and skirt democratic and regulatory controls and infringe on the right to a healthy environment (and the right to life, health, and water) (UNHRC, 2021, Resolution 48/13), leaving the onus solely with Moananui nations to manage waste, prevent plastic pollution, strengthen legislation, develop an effective remedy, and protect environments and communities.” (Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Ngata, Borrelle and Farrelly2022, p. 548)

Another example from the same text relates the case of “An Indigenous leader from Tuvalu reports, Tuvalu showed leadership in enacting legislation to prevent plastic pollution and had intended to enact a waste levy, but due to pressures and ‘barriers’ from ‘the business community’ (local importers/suppliers) it was blocked…we argue that weak policy (that which is able to be exploited) is not the result of a Te Moananui governance and policy deficit, but rather, is because of Western-centric epistemologies and pedagogies promoted in Te Moanunui since colonization” (Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Ngata, Borrelle and Farrelly2022, pp. 549, 550).

For many texts, “regulatory capture” may in fact be too weak to describe how authors understood plastics and other pollutions to be not an error, oversight, or corruption of settler state governance, but part of its very structure. Shadaan and Murphy (Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020) write that “Canada’s environmental governance is largely a permission-to-pollute system, designed to support extraction as a core economic feature of the nation…. The presence of over 150 years of colonial disruption is profoundly shaped by the laws and regulations of the Canadian state in the past but also in the present” (p. 2). They go on to explain how “disrupting Land/body relations…are made possible by a permission-to-pollute regulatory regime. This regulatory regime emphasizes outdated ‘dose makes the poison’ approaches to toxicity, erasing not only low-dose effects, but also intergenerational effects, cumulative effects, as well as concentrated effects that expose Indigenous, Black, Brown, and poor communities to early mortality, intensified debility, and reproductive violence” (Shadaan and Murphy, Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020, p. 8; also see Carmen and Waghiyi, Reference Carmen and Waghiyi2012; CLEAR and EDAction, 2017; Lui, Reference Lui2017; Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021a).

Texts in the corpus included examples such as: how “toxics governance relies on industries to self-report their emissions, and to do the research that determines whether their own chemicals are harmful” (CLEAR and EDAction, 2017, p. 2; also see Shadaan and Murphy, Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020); the inability or lack of investment that means “violations [of plastic disposal] by both the populace and industry go largely unpunished” (Wagner-Lawlor, Reference Wagner-Lawlor2018, p. 214); pushing responsibility of discarded plastic waste onto Indigenous guardians or rangers rather than the industries that create them (Phillips, Reference Phillips2017, p. 1152); or the structure of trade policies and relations to create and maintain plastic flows into Indigenous lands (Manglou et al., Reference Manglou, Rocher and Bahers2022; Fuller et al., Reference Fuller, Ngata, Borrelle and Farrelly2022; Gascón, Reference Gascón2022, p. 4; Peryman, Reference Peryman2022). Again, for many of these authors, there is no pre-existing, un-colonial state of settler governance that has been corrupted. Instead, most frame “regulatory capture” as a characteristic of settler and colonial governance.

Wariness of Western science and the call for more research

Research in general and science, in particular, were discussed in the corpus extensively (indeed, the largest share of texts was peer-reviewed and academic articles, due to the method of literature review used). However, Indigenous authors expressed ambivalence, weariness, and caution around non-Indigenous research concerning plastics pollution. Tina Ngata explains that, “Entitlement and extraction mentality are foundational to colonial thinking – and when that manifests in science it looks like researchers assuming their questions are valid, assuming a level of intellectual authority, assuming their practice is safe, and assuming the right to take from Indigenous knowledge and science for the ‘betterment of humanity…. Addressing scientism is not always something fixed with ‘more research’ or even ‘better research’ – it can be as simple as getting out of the way of Indigenous scientists and communities who already have the answers but have just experienced colonial barriers to implementing them” (Ngata and Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021, p. 6). Multiple texts discussed how Indigenous peoples have extensive local knowledge of chemical infrastructures and plastics pollution that does not require more or outside research (Luginaah et al., Reference Luginaah, Smith and Lockridge2010; McGregor, Reference McGregor2010; Butler et al., Reference Butler, Gunn, Berry, Wagey, Hardesty and Wilcox2013; Shadaan and Murphy, Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020).

Authors outside of the corpus have written about how research can deepen colonial structures of power in several ways. Gerald Singh and colleagues write that “Contemporary environmental degradation and social inequity result in part from the long-standing practice of applying scientific innovation to exploit natural resources in unsustainable and inequitable ways. Historically, science and technology were used to better understand ocean systems to enrich European nations by fueling mercantile and colonial interests and the geopolitical and economic demands of nations with substantive ocean estates or oceanic empires” (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Harden-Davies, Allison, Cisneros-Montemayor, Swartz, Crosman and Ota2021, p. 2). They argue that more basic research has no intrinsic ability to reverse or even slow that trend. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami has described how “the primary beneficiaries of Inuit Nunangat research continue to be [non-Inuit] researchers themselves, in the form of access to funding, data and information, research out-comes, and career advancement” (2018, p. 5, also see Liboiron et al., Reference Liboiron, Zahara, Hawkins, Crespo, de Moura, Wareham-Hayes, Edinger, Muise, Walzak, Sarazen, Chidley, Mills, Watwood, Arif, Earles, Pijogge, Shirley, Jacobs, McCarney and Charron2021). Given Figure 1, this trend continues in terms of research about Indigenous participation in plastics pollution. At a more basic level, Indigenous researchers have noted how outside research is a source of plastic pollution in Indigenous homelands, and that only 38% of peer-reviewed articles on plastics in surface waters of Inuit homelands noted they had permits from Inuit research review boards as required in the area (Liboiron et al., Reference Liboiron, Zahara, Hawkins, Crespo, de Moura, Wareham-Hayes, Edinger, Muise, Walzak, Sarazen, Chidley, Mills, Watwood, Arif, Earles, Pijogge, Shirley, Jacobs, McCarney and Charron2021). This is why Indigenous thinkers say that “it is not enough just to know; one has to ‘do something,’ or ‘act responsibly’ in relation to the knowledge” (McGregor, Reference McGregor2014, p. 495. Also see Carroll et al. Reference Carroll, Garba, Figueroa-Rodríguez, Holbrook, Lovett, Materechera, Parsons, Raseroka, Rodriguez-Lonebear and Rowe2020).

Intersectionality: Attention to the intersections of indigeneity and other social locations

Indigenous-led texts in the corpus routinely incorporated an intersectional approach to understanding the harms and interventions to plastics pollution. Intersectionality refers to the way that two or more forms of oppression and/or identity come together to produce unique forms of oppression (or possibility) that is more than the sum of their parts (Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1990). In the corpus, gender and age mattered to how plastics pollution was experienced and how governance should be conducted.

The most common intersection was between indigeneity and gender. Authors argued that environmental violence is highly gendered and constitutes a unique “gendered economy of pollution” (Shadaan and Murphy, Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020, p. 14). Indigenous women were understood as bearing unique burdens from plastics pollution during its lifecycle, from the gendered violence from man-camps at oil and gas extraction zones (Native Youth Sexual Health Network, 2016) to in the disproportionate harm from EDCs related to reproductive health (EDCs) (Carmen and Waghiyi, Reference Carmen and Waghiyi2012; Shadaan and Murphy, Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020; Aker et al., Reference Aker, Caron-Beaudoin, Ayotte, Ricard, Gilbert, Avard and Lemire2022; Rodríguez-Báez et al., Reference Rodríguez-Báez, Medellín-Garibay, Rodríguez-Aguilar, Sagahón-Azúa, Milán-Segoviaa and Flores-Ramírez2022; Akwesasne Task Force on the Environment, 2023). Gendered roles related to food gathering and preparation, work in informal economies, cleaning and hygiene, crafting, and the provision of household goods also contributed to this burden (Seeman and Walker, Reference Seeman and Walker1991; Luginaah et al., Reference Luginaah, Smith and Lockridge2010; Carmen and Waghiyi, Reference Carmen and Waghiyi2012; Asomani-Boateng, Reference Asomani-Boateng2016; Phillips, Reference Phillips2017; Runyan, Reference Runyan2018; Alda‐Vidal et al., Reference Alda‐Vidal, Browne and Hoolohan2020; Shadaan and Murphy, Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020, p. 5; Indigenous Services Canada, 2021; Chineme et al., Reference Chineme, Assefa, Herremans, Wylant and Shumo2022).

Indigenous women were also understood to have a unique and crucial role in leading initiatives, protests, or changes related to plastic pollution due to many of these same gendered roles, as well as teaching and holders of culture (Carmen and Waghiyi, Reference Carmen and Waghiyi2012), their role as social organizers within families and communities (McGregor, Reference McGregor2015; Asomani-Boateng, Reference Asomani-Boateng2016; MEWWS, 2017; Wagner-Lawlor, Reference Wagner-Lawlor2018, p. 214; Chineme et al., Reference Chineme, Assefa, Herremans, Wylant and Shumo2022), and because of a “sacred connection… [to] waters” and the labor that goes into caring for water (McGregor, Reference McGregor2015, p. 74). Sometimes two-spirit, non-binary, or gender non-conforming people were mentioned, but mainly to include a fuller range of gender minorities or “gender constituency” rather than to focus on unique gender roles (Native Youth Sexual Health Network, 2016, p. 6; Murphy, Reference Murphy2017b; Belfer et al., Reference Belfer, Ford, Maillet, Araos and Flynn2019).

Like women, youth and children carry an above-average burden from EDCs and exposure to plastics (Asomani-Boateng, Reference Asomani-Boateng2016; Native Youth Sexual Health Network, 2016; Dubeau et al., Reference Dubeau, Aker, Caron-Beaudoin, Ayotte, Blanchette, McHugh and Lemire2022; Akwesasne Task Force, 2023). In the corpus, youth were discussed in terms of having unique rights relating to pollution, particularly body burdens (Carmen and Waghiyi, Reference Carmen and Waghiyi2012; Native Youth Sexual Health Network, 2016; Norweigian Forum, 2020), as well as having specific leadership roles or capacity (McGregor, Reference McGregor2015; Native Youth Sexual Health Network, 2016; Arsenault et al., Reference Arsenault, Diver, McGregor, Witham and Bourassa2018; Belfer et al., Reference Belfer, Ford, Maillet, Araos and Flynn2019). It was also noted that these rights and capacities are combined with relative powerlessness in relation to adults, particularly, when it came to leadership (Ngcuka, Reference Ngcuka2022). Another common framing of youth participation in plastics governance and initiatives was in terms of training and education. One researcher wrote that “education should begin with children and youth as they will in turn teach adults in their communities” (McGregor, Reference McGregor2010, p. 76; also see McGregor, Reference McGregor2015; BC Gov News, 2022; Schlosser et al., Reference Schlosser, Eicken, Metcalf, Pfirman, Murray and Edwards2022). These points were rarely as well integrated as discussions of gender minorities or elders. There were rarely reasons given for why young people had greater body burdens, specific capacity for leadership, or unique rights. There were no youth-led texts in the corpus.

Indigenous elders are widely acknowledged as being TK holders, so they most often appeared in the corpus as sources of information or expertise (LaDuke, Reference LaDuke, Lobo, Talbot and Morris2010; McGregor, Reference McGregor2010, Reference McGregor2014; Native Youth Sexual Health Network, 2016; Arsenault et al., Reference Arsenault, Diver, McGregor, Witham and Bourassa2018). This recognition is so widespread that one study noted when elders were not represented in a participatory governance body (Belfer et al., Reference Belfer, Ford, Maillet, Araos and Flynn2019, p. 18). Only one text specifically stated that elders were important targets of inclusion and engagement for plastics pollution intervention because of their important roles in community (Huntsdale, Reference Huntsdale2016).

In their review of participation in marine governance, Parsons et al. found that “Indigenous conceptualisations of what constitutes sustainable marine governance and management frequently extend to include intergenerational justice matters” (2021, p. 18). This was also the case in our review. The corpus discussed “the ways EDC pollutants have disrupted communities intergenerationally” (Shadaan and Murphy, Reference Shadaan and Murphy2020, p. 3). In one case, an Indigenous indicator of stream health included whether people returned to the stream over time and across generations (Tipa and Teirney, Reference Tipa and Teirney2006). It was also common to discuss how intergenerational sharing of knowledge is essential to community-based governance and sustainability through the connection between youth and Elders (McGregor, Reference McGregor2010; Aresenault et al., 2018).

Cultural resurgence: The role of plastic pollution interventions in strengthening cultural revitalization

The corpus included a surprising number of non-Indigenous authors writing about Indigenous artists using plastic waste to make art (e.g., Butler et al., Reference Butler, Gunn, Berry, Wagey, Hardesty and Wilcox2013; Le Roux, Reference Le Roux2016; Wagner-Lawlor, Reference Wagner-Lawlor2018; Castro-Koshy and Le Roux, Reference Castro-Koshy and Le Roux2020; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Paturi, Puri, Senf Jakobsen, Shankar, Zejden and Azzali2020). In these articles, as well as texts about Indigenous-led business, social initiatives, and conservation management, Indigenous-led plastic pollution interventions are premised on investing in cultural ways of doing, knowing, and being were the primary goals of many of these activities, rather than mitigating the impacts or flows of plastics (though this was often also the case, but as an additional outcome). One researcher wrote that, “The art of plastic pollution from Nigeria marks more than an environmental consciousness. It also marks an ecological consciousness based on contemporary plastic-waste artists’ commitment to advocating the recovery of traditions of repurposing materials and of skilled craft work” (Wagner-Lawlor, Reference Wagner-Lawlor2018, p. 198). For instance, an Indigenous-partnered 3D printing social enterprise, the project was rooted in place and elder knowledge rather than the effectiveness of the project for dealing with plastic flows (Huntsdale, Reference Huntsdale2016). This is not a shortcoming of the project, but the point. In another case, many indicators of water health for tangata whenua are about the continuation of culture, such as “fitness for cultural usage” (Tipa and Teirney, Reference Tipa and Teirney2006, p. 1) and “the number of species of traditional significance that are still present” (2006, p. 2). Taken together, these examples may be understood as surviance with plastics, where themes of survival, continuity, and resistance are more important than narratives of destruction, harm, or demise (Vizenor, Reference Vizenor1999; Tuck, Reference Tuck2009; Murphy, Reference Murphy2017b).

Togetherness: Collectives, coalitions, partnerships, and sharing

We have left this section until the end because, as this review has shown, inclusion is often mistaken for togetherness and “working with” does not necessarily achieve meaningful participation and change. It can even cause harm. Jones with Jenkins writes that, “the liberal injunction to listen to” and collaborate with Indigenous peoples.

“Can turn out to be access for dominant groups to the thoughts, cultures, and lives of others… the crucial aspect of this liberating process is making themselves visible to the powerful. To extend the metaphor: In attempting, in the name of justice and dialogue, to move the boundary pegs of power into the terrain of the margin-dwellers, the powerful require those on the margins not to be silent, or to talk alone, but to open up their territory and share what they know. The imperialist resonances are uncomfortably apt” (Jones and Jenkins, Reference Jones, Jenkins, Denzin, Lincoln and Smith2008, p. 480; also see Cid et al., Reference Cid, Milligan-Myhre, Leonard, Alegado, Liboiron, Yusuf, David-Chavez, Gomez, Ellenwood, Crocker, Small-Lonebear, Johnson, Jennings, Aarons, Russo Caroll and Tsosie2021).

While collaboration and partner/partnership are two of the three most common participatory terms in the corpus, the corpus also demonstrates that these terms hide a vast range of engagement frameworks. Indigenous authors characterized collaborations in terms of Indigenous rights, treaties, and leadership (Figure 3). This cluster of terms, as well as close readings of the texts, foreground a call for collaboration based on Indigenous sovereignty – the ability to govern – rather than inclusion, the ability to show up. In a discussion about plastics pollution research in the Arctic, Indigenous researchers have asked that “capacity building” frameworks be abandoned for “capacity sharing” (Pijogge and Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021), echoing other Indigenous researchers in a critique of deficit framing and even the “capacities approach at all” (Watene, Reference Watene2016). These critiques argue that Indigenous “communities already have the foundations upon which to build community capacity and address the environmental challenges they face” (McGregor, Reference McGregor2010, p. 81), including robust social capital (Chineme et al., Reference Chineme, Assefa, Herremans, Wylant and Shumo2022) and knowledge (Pijogge and Liboiron), and that colonization is the primary barrier to this work (Ngata and Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021). Following an IEJ model, addressing the dynamics of colonization so that Indigenous ways of being, doing, and thinking are able to flourish, rather than be merely incorporated, into partnerships.

Conclusion

Our review of texts finds that even when Indigenous involvement in plastics pollution governance is discussed, different actors mean fundamentally different things. We find that the core actor group (Indigenous, non-Indigenous, and settler governments and organizations) accounts for considerable differences in the degree and mode of Indigenous participation in our corpus. Notably, sources authored by Indigenous individuals or organizations were more likely to directly oppose colonial systems of pollution in favor of rights- and justice-based modes of governance, compared to non-Indigenous authors and organizations that tended to advocate for inclusion, recognition, and even extraction-based Indigenous involvement that conform to colonial norms. We realize that in the latter case extraction is unintentional, but it remains a dominant framework of Indigenous participation by non-Indigenous actors (Figure 3).