It is almost impossible to talk about political activism in China without talking about lawyers. In the early 2000s, Western media coverage of activist lawyers such as Gao Zhisheng 高智晟, Chen Guangcheng 陈光诚 and Pu Zhiqiang 浦志强 introduced readers to outspoken lawyers who believed that litigation could spur social change. Capitalizing on state rhetoric about the importance of law and the profession's new-found autonomy from the state, China's activist lawyers bravely pushed for causes as diverse as labour rights, constitutional review and even human rights. In parallel with real-life developments, an academic literature emerged to offer in-depth portraits of the “rights-protection” (weiquan 维权), “die-hard” (sike pai 死磕派) and human rights lawyers determined to transform the law by using it.Footnote 1 As repression has intensified in recent years,Footnote 2 much attention has also become devoted to detailing the risks of activism, including house arrest, torture and forced confessions.

Yet, for all the attention justly paid to the activist wing of the bar,Footnote 3 they are not the only Chinese lawyers who participate in politics. Here, we focus on a different set of politically active lawyers: “state-adjacent” lawyers who devote significant volunteer time to helping the state govern effectively. Empirically, drawing attention to this oft-overlooked group complicates our understanding of Chinese lawyers as political actors and answers calls to treat the professions as variegated rather than monolithic.Footnote 4 Conceptually, it trains our attention on the liminal space between state and society, an in-between zone that we call “state-adjacent.” State-adjacent lawyers inhabit a politically embedded position neither entirely within-the-system nor outside-the-system, where they serve as trusted citizen-partners in governance. As a bridge between the state and the public, and between the state and the legal profession, they can often be found providing legal aid, serving as government legal advisers or offering suggestions about how to improve laws, legal institutions and the “people's livelihood” (minsheng 民生).

To concretize what it means to be state-adjacent, we examine how recipients of the All-China Lawyers Association's Outstanding Lawyer Award (quanguo youxiu lüshi jiang 全国优秀律师奖) participate in Chinese political life.Footnote 5 Although this group does not include every state-adjacent lawyer in China, it is one set of lawyers plainly playing a state-endorsed political role. Local officials are involved in the selection process, and there is an explicit expectation that awardees exhibit excellent political quality (zhengshi suzhi guoying 政治素质过硬), exceptional professional integrity (zhiye caoshou youyi 职业操守优异) and outstanding work achievements (gongzuo yeji tuchu 工作业绩突出).Footnote 6 Below, we draw on an original database of biographical information on the 604 award winners between 2005 and 2014, as well as 28 semi-structured interviews with awardees, to explore who is invited to participate in governance, how state-sanctioned political participation works and why lawyers find these activities meaningful. Our data allow us to approach the consultative core of Chinese politics from the bottom up, from the perspective of lawyers invited into the state's consultative process.

Detailing the political role played by state-adjacent lawyers places this article at the intersection of two strands of China studies research. First, we join the growing group of scholars who take possibilities for political participation seriously despite the lack of national elections.Footnote 7 Second, our discussion of state-adjacent lawyers adds to our understanding of when and why the Chinese state outsources critical tasks to trusted individuals.Footnote 8 Certainly, recruiting third parties is a well-chronicled way to defang protest, from enlisting social workers, friends and family to persuade the recalcitrantFootnote 9 to hiring thugs to intimidate them through violence.Footnote 10 Adding lawyers to a growing list of trusted third parties shows that outsourcing is helpful in the daily business of governing, rather than a strategy solely to combat unrest.Footnote 11 More broadly, the point is that a too-sharp division between state and society obscures the important role played by trusted brokers with a foot in both worlds.Footnote 12 At least in law, and likely far more widely, dedicated volunteers stand adjacent to the state, a platform from which they provide information to the government and persuade citizens to buy into government priorities.

Data and Methods

To supplement publicly available documents, this article draws on two original sources of data. First, the Outstanding Lawyers Database contains biographical data for 604 of the 614 attorneys who have received the award since its inception in 2005.Footnote 13 Information on each award winner was collected primarily from two online sources: winners’ online law firm profiles and write-ups about winners in the All China Lawyers Association (ACLA) online yearbook. When possible, we supplemented this data with news articles about the winners. Despite variation in available information, the dataset includes consistent information on gender, educational background, work experience and involvement with local bar associations.

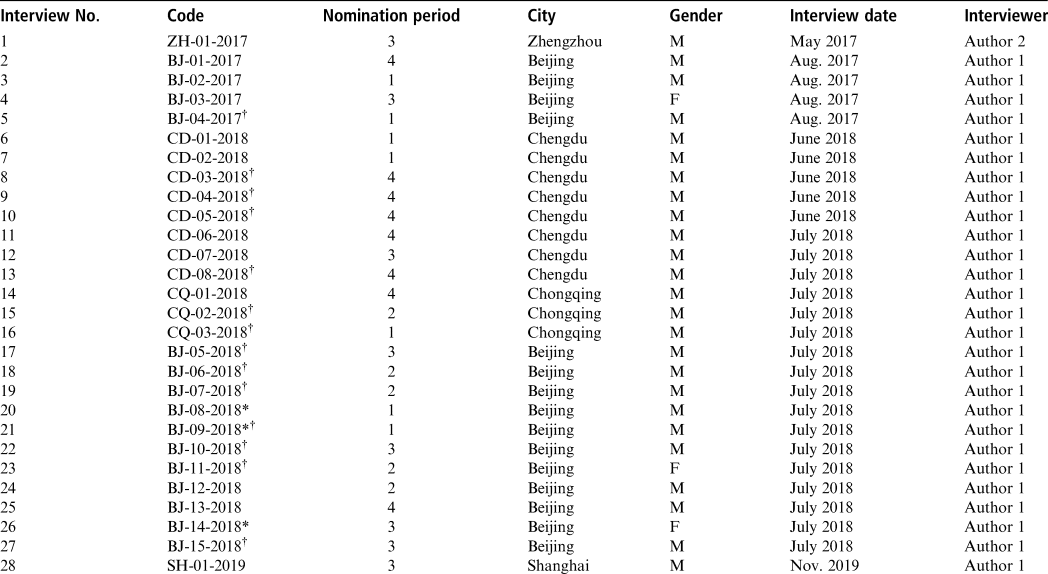

Second, we draw on 28 semi-structured interviews with winners of the Outstanding Lawyer Award, which were conducted between May 2017 and November 2019. Each interview lasted between 45 minutes and three hours.Footnote 14 During these conversations, we asked interviewees about the role and responsibilities of a lawyer, their view of other lawyers and legal reforms, and their involvement with the bar association. Interviews took place across five cities (Zhengzhou, Beijing, Chengdu, Chongqing and Shanghai), with the majority occurring in Beijing and Chengdu. We selected Chengdu and Beijing as our two main field sites in order to capture the experience of lawyers in both first and second-tier Chinese cities.

The Outstanding Lawyer Award and its Awardees

Since the award's inception, ACLA has honoured four cohorts of Outstanding Lawyers (2005, 2005–2007, 2008–2010 and 2011–2014). To ensure geographic diversity, ACLA assigns each province or provincial-level city a quota of awards and the provincial bar associations then divide these awards among their cities. From there, local bar associations manage the selection process, with significant input from officials from the justice bureau (MoJ), the public security bureau, the procuracy and the courts. Publicly available documents from Guangzhou, Hunan and Shanghai offer insight into how selection works. In Guangzhou during the 2011–2014 round, MoJ officials and lawyers involved with the city bar association first proposed a list of nominees. The list was then vetted by the local bar's Party committee, approved by the bar association's standing committee and forwarded to the provincial bar association.Footnote 15 In Hunan and Shanghai, the head of the MoJ office responsible for the supervision of lawyers (lüshi chu chuzhang 律师处处长) has historically served as the MoJ representative on the selection committee.Footnote 16

According to the 2008–2010 ACLA selection criteria notice, selection committees should first and foremost identify nominees with high political quality. “Political quality” is indicated by support of the CCP leadership, belief in socialist rule of law and behaviour in accordance with the Party line.Footnote 17 A score sheet used in Hunan to rank the 2011–2014 nominees awarded extra points to those who served the state as legal advisors to the bar association, the people's congress or the people's political consultative conference. Special weight was also given to winners of previous government awards.Footnote 18 Professional ethics are a secondary consideration, visible in a work history free of disciplinary action from the bar association. Finally, ACLA guidelines suggest that Outstanding Lawyers should take on social responsibilities beyond their day-to-day legal work and contribute to social welfare.Footnote 19

Our database of awardees shows that this process typically culminates in the selection of a well-read, domestically educated male with strong ties to the ACLA or his local bar association (Table 1). Just over 80 per cent of awardees are leaders in the bar association, perhaps an unsurprising outcome given that local bar associations control the nomination process. Nominees would be well known to a committee already disposed to believe that bar association leadership shows a public-spirited ability to organize and inspire others. More surprising is the underrepresentation of women. About 20 per cent of awardees are female across each of the four rounds, a proportion that has not risen despite more women entering the profession.Footnote 20 In Beijing and Shanghai, two cities where the bar association maintains public directories of lawyers that include party affiliation, it is also true that Outstanding Lawyers are more likely to be Party members – 69 per cent of those from Beijing belong to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), as do 47.2 per cent of those from Shanghai, both of which exceed the proportion of CCP lawyers among the entire profession and for each city respectively.Footnote 21

Table 1: Outstanding Lawyer Award (2005–2014), Descriptive Statistics

Notes:

* A Chinese university was coded as “top 20” if it was included in the 2015 Ministry of Education list of top law schools.

State-adjacent Lawyering: Political Embeddedness and Political Participation

Many Chinese lawyers want to deepen their political embeddedness by cultivating a “diverse portfolio of direct and indirect, individual and organizational ties to the state.”Footnote 22 Close ties with officials help lawyers to find clients, win cases and collect evidence from state agencies, while also providing some protection against political retribution.Footnote 23 Political connections are also a resource for political participation. Some politically embedded criminal defence lawyers, for example, lobby officials for causes associated with political liberalism,Footnote 24 and some politically embedded administrative lawyers sue the state to try to improve government accountability.Footnote 25 Among Guangdong lawyers who help the government to respond to online petitioners, older lawyers (who are likely to have higher social status and better political ties) are also more likely to provide direct legal advice than their younger and less embedded colleagues.Footnote 26 Outside the legal field, politically connected citizens are more likely to complain to the authorities about public services than their less-connected neighbours, even if they do not experience higher levels of dissatisfaction.Footnote 27

This article extends understandings of how and why Chinese lawyers are politically embedded in three ways. First, social scientists have typically measured political embeddedness through static characteristics of an individual's biography. A previous job inside government is commonly treated as a proxy for political embeddedness among lawyers,Footnote 28 for example, while citizens are coded as politically connected if they have a relative who works for a government agency.Footnote 29 In contrast, we look at how lawyers build ties to the state through volunteer work, a shift that lends a measure of social mobility to the concept of political embeddedness. Lawyers can affirmatively opt into the political establishment, even without the benefit of a previous government job or a well-connected family.

Second, we flesh out the spatial dimensions of political embeddedness. Others have noted that political embeddedness is locally bounded, as the usefulness of political ties often fades abruptly outside a lawyer's hometown.Footnote 30 We agree, and go a step further by conceptualizing politically embedded lawyers as “state-adjacent.” To be “state adjacent” is to occupy a liminal space between state and society, an intermediate zone that complicates efforts to classify lawyers as either system-insiders (tizhi nei 体制内) or outsiders (tizhi wai 体制外).The idea of a state-adjacent zone between state and society comes out of our interview data. When we explicitly asked Outstanding Lawyers if they think of themselves as within-the-system or outside-of-it, most interviewees rejected the dichotomy and found a way to talk about how they bridge the gap between state and society.Footnote 31 A Chengdu Outstanding Lawyer, who manages a private law firm and also serves as a part-time government legal advisor, captured the tension of simultaneously standing inside and outside the system particularly well:

If we use the phrases within-the-system and outside-the-system, all [part-time government legal advisors] are within-the-system. But, we are also not official government staff members. So, we are really both within-the-system and outside-the-system. From the within-the-system perspective, we all respect the law and follow the government's lead, and we wholeheartedly serve the government and country when acting as government advisors … Whenever there is a conflict between Chinese and foreign interests, we will definitely stand with our country and government. In terms of outside-the-system, we are not official parts of the establishment, nor are we official government employees. We provide services on individual issues as they come up, and what we tell the government is merely suggestive. The government can adopt the suggestions, but they can also reject them.Footnote 32

In trying to describe how they are close to the state and yet not part of it, a number of interviewees also drew a distinction between their formal position and the tactics they use. Unlike judges, lawyers are “independent actors” who are not part of the civil serviceFootnote 33 and by extension push for change from beyond the “borders” of government.Footnote 34 Outstanding Lawyers typically described their tactics, however, as working within-the-system, with an emphasis on “collaboration” and “compromise.”Footnote 35 In interviews, they also sharply differentiated their insider advocacy approach with the “illegal” (feifa 非法 or bu hefa 不合法), “excessive” (guoji 过激 and guofen 过分), “irrational” (bu lixing 不理性) or “destructive” (pohuai xing 破坏性) tactics used by activist lawyers.Footnote 36 In a typical example, an Outstanding Lawyer from Henan condemned activist lawyers for “radical measures” such as interrupting court proceedings, “making up facts” and blocking the doors to government offices.Footnote 37 To some, escalating rapidly to confrontation is wrong-headed when “there are normal tactics” left to try.Footnote 38

Third, we add a fresh perspective to ongoing debates about why political embeddedness is prized. Most research on political embeddedness among Chinese lawyers emphasizes the material benefits of close ties to the state.Footnote 39 In contrast, our focus is on a group of lawyers who donate a great deal of time to political participation, even as the material returns on their time diminish. We side, then, with those who underscore the non-material satisfactions of civic-minded political participation in contemporary China.Footnote 40 We also note that political participation comes in multiple ideological flavours. In contrast to politically embedded “progressive elite” lawyers who advocate for political liberalism – and feature prominently in the English-language literatureFootnote 41 – state-adjacent lawyers are more heterogeneous in their views and less dissatisfied with the status quo. They work in service of the political system, driven by a broad sense of service to society, the people and the Party. In this version of “symbiotic exchange” between market and state actors, what lawyers receive is the opportunity to participate in politics.Footnote 42 Political participation is seen as a valuable commodity, perhaps partly for the economic benefits it brings but also because lawyers find it personally meaningful.

For students of state–society relations in contemporary China, our account of the political role played by state-adjacent lawyers is a reminder that politics is not “always a story of neatly divided antagonists with representatives of the state on one side, and members of the popular classes on the other side.”Footnote 43 Too crisp a division between state and society obscures the people who straddle both worlds in an attempt to create a more perfect China and how the state relies on them to provide information, maintain order and build legitimacy. Indeed, the role played by state-adjacent lawyers has much in common with the work of people's congress deputies. The CCP has long believed in the need for a public voice in policymaking, and both deputies and state-adjacent lawyers act as a “link from the leadership to the citizenry” as they advocate for their communities and also “deflect illegal or impractical demands.”Footnote 44 Lawyers’ professional identity, however, sets them apart. Although lawyers sometimes offer suggestions to improve life in their residential communities, their greater value to the state is their professional expertise. They serve as an important corps of not-quite-in-house legal experts who contribute to the state's signature project of legal construction.Footnote 45 Also, unlike deputies, they serve as a bridge to the legal profession rather than only to citizens. Instructing young lawyers, and modelling success for them, is not an incidental sideline. Rather, it is a critical front of the Party's larger persuasion project, as the legal profession has harboured the fiercest political critics to yet emerge in China's 21st century.

The Functions of State-adjacent Participation: Information and Persuasion

Perhaps above all, Outstanding Lawyers are dedicated volunteers.Footnote 46 Interviewees reported spending an average of 40 per cent of their working hours on forms of political participation that are either unpaid or performed for minimal pay.Footnote 47 These activities include (but are not limited to) serving as people's congress and people's political consultative conference deputies, working as part-time government legal advisors, holding leadership positions in the bar association, providing legal aid and hosting policy forums at their law firms. How does this sundry list of time-consuming activities contribute to governance? We take a functional approach and focus on two roles Outstanding Lawyers play in politics: the information they provide to the state and how they persuade others to behave in ways the state considers appropriate.

First, Outstanding Lawyers provide the state with recommendations grounded in their legal knowledge and life experiences. Sometimes, this feedback happens through formal channels designed to deliver feedback to policymakers, such as serving in a local representative body, as a government legal advisor or holding a leadership position in the ACLA. For example, Outstanding Lawyers have advocated for changes in the definition of how judges classify small-claims litigationFootnote 48 as well as for the establishment of an intellectual-property court in Beijing's Zhongguancun 中关村 technology hub.Footnote 49 The role of part-time government legal advisor is also an increasingly important way for Outstanding Lawyers to offer policy opinions, participate in the drafting of laws and contracts, defend state agencies in litigation and (in at least one caseFootnote 50) give regular lectures on law to government officials. There is an official goal of establishing legal advisor positions inside all Party and state organs by the end of 2020,Footnote 51 and the government increasingly recognizes that it should “let the professionals handle professional work.”Footnote 52

Some Outstanding Lawyers share social circles with officials and can offer advice in more informal settings, such as a shared meal or a WeChat group. At least in person, even sensitive political topics can be in bounds for discussion. One Chengdu Outstanding Lawyer, for example, organizes bimonthly dinners with fellow law school alumni who work as lawyers, judges, police officers, prosecutors and professors in the city. During these meals, the group discusses a pre-selected law-related topic, such as how artificial intelligence will affect the future of the legal profession. At the dinner attended by one of the authors, the trust uniting the group was strong enough that participants shared their thoughts on the Xinjiang detention centres, perhaps the most politically sensitive issue in China today.Footnote 53 But, not all Outstanding Lawyers are equally able to exercise influence in this way. Professional socializing is both common in contemporary China and largely dominated by middle-aged men. Not only are gender and age important factors affecting who is most likely to win the Outstanding Lawyer Award, they also continue to shape opportunities for informal political participation afterward.

Second, the state increasingly relies on lawyers to defuse anger towards the government, and Outstanding Lawyers are often found persuading citizens to give up claims or compromise.Footnote 54 When asked about their volunteer activities, about a quarter of our interviewees chose to discuss their work helping the state settle thorny disputes with citizens.Footnote 55 A story told by a Beijing Outstanding Lawyer, who describes himself as a “film director” who directs how confrontations unfold, exemplifies how state-adjacent lawyers defuse state–society conflict.Footnote 56 Once, he represented two parents whose son had died in a car accident caused by an ice patch on a poorly maintained highway. The parents had petitioned various levels of government for over ten years, but this lawyer knew that the state would never admit fault. Tearing up while re-telling this story, he recounted how he convinced the parents to give up their fight by empathizing with their plight and then suggesting that their actions hurt their son as he looks down on them from the afterlife. “Your son is unwilling to see you in so much pain,” he told them, a line of logic that he says addressed their emotional needs and convinced them to finally drop their claims.

In mediating disputes between citizens and the state, state-adjacent lawyers leverage their status as “professional, third parties” (zhuanye 专业,di sanfang 第三方) who can be trusted to analyse the situation from an “objective and fair point of view.”Footnote 57 Lawyers involved in demobilizing protest help identify relevant laws and policies, explain complicated procedures and assess the legality of government responses.Footnote 58 When confronted with a sober legal analysis from a professional not employed by the state, aggrieved citizens often lower their demands.Footnote 59 At times, professionalism can also be a cudgel deployed to persuade clients to take their lawyers’ advice. One Outstanding Lawyer we interviewed specializes in representing migrant workers, a group known for disrupting societal stability through protest and petitioning.Footnote 60 Despite the high stakes of his work, he rarely clashes with clients because he simply reminds them “I'm the professional here.” Clients almost always trust and accept his advice because of his years of experience.

Another facet of persuasion is socialization, seen in how Outstanding Lawyers model success for younger lawyers. Some Outstanding Lawyers embrace this role and describe mentorship as an important part of their jobs.Footnote 61 In Chongqing, an Outstanding Lawyer who felt strongly about nurturing the next generation quoted Wen Jiabao 温家宝 to make his point: “A train cannot only look at the engine, but it must also look at the caboose.”Footnote 62 Mentorship can also take the form of on-the-job training, as was the case for a Beijing Outstanding Lawyer who was proud of recruiting a team of young lawyers for pro bono property-dispute mediation.Footnote 63 For others, it involves lecturing to audiences of young professionals. Although these lectures are typically framed as continuing education, the stories and experiences of the person at the podium also shape the aspirations of listeners. The lecture circuit can be quite active, as Chinese lawyers are required to complete at least 30 credits of continuing legal education each year.Footnote 64 One Outstanding Lawyer in Chongqing gives 50 to 60 lectures a year across the country, and works hard to make his lectures on law firm management, labour law and banking regulations as entertaining as “listening to stories.”Footnote 65 Another Beijing Outstanding Lawyer who leads ACLA training programmes described these unpaid lectures as “a huge honour” that are as much a part of his job responsibilities as representing clients.Footnote 66

State-adjacent lawyering also has important implications for state capacity. Over the first two decades of the 21st century, state-adjacent lawyers gave Chinese government officials access to legal expertise without the burden of having to pay their salaries. As China has grown richer, and also in tandem with Xi Jinping's 习近平 emphasis on law, it is perhaps not surprising that there is a push to hire more lawyers at all levels of government and bring legal expertise in-house. State-adjacent lawyers will continue to play an important role in governance, however, because a plausible distance from the state enhances their persuasive power. They are not the direct target of ire inspired by the decisions or incompetence of officials and are thus well-positioned to do what sociologist Erving Goffman once called “cooling out the mark,” or ensuring that citizen anger stays within manageable proportions.Footnote 67 They can listen without defensiveness to furious diatribes and express empathy without fear that any kindness or apology might be treated as an admission of wrongdoing or a promise to make things right. Persuasion work extends state capacity, too. Effectively cooling out angry citizens or inspiring future state-adjacent lawyers is a time-intensive process and each incident that lawyers manage to defuse solves a headache for the officials involved.

Motivations

Why are Outstanding Lawyers willing to devote so much time to political participation? The most obvious explanation is money, meaning that the award provides a reputational boost so that lawyers can attract more business, raise their fees, or both. Based on our conversations, money is at least part of the story for some. Three Outstanding Lawyers mentioned an uptick in business after receiving the award, which they attributed to public recognition of their already high-quality work.Footnote 68 For a slightly larger number of interviewees, this reputational boost translated into more wealth for their firms, even if not always for themselves.Footnote 69 The way that Chinese lawyers are paid, however, suggests that money is not the full story. Compensation for most Chinese lawyers is calculated as a percentage of billed revenue, sometimes called an “eat what you kill” system, such that unpaid volunteer labour translates into less income. Indeed, many interviewees described participation and wealth as a trade-off: the more time they spend volunteering, the less time they have for legal work. Even if participation opens up some professional opportunities, it is ultimately unpaid work that causes a lawyer to “lose lots of billable hours.”Footnote 70 Although Outstanding Lawyers are doing well for themselves financially – nearly all are law firm partners with a good number serving as the firm's managing partner – many emphasized that not chasing after the fattest pay cheque is part of what makes them distinctive.Footnote 71 As explained by one Outstanding Lawyer in Beijing, lawyers who only seek to maximize their income are not well-respected.Footnote 72 Being a “big-time lawyer” is about much more than making money, another Beijing awardee stressed, and Outstanding Lawyers are not those at the top of the income ladder.Footnote 73

If money is not the sole motivator, are Outstanding Lawyers driven by the chance to shape policy? Certainly, they are quick to identify numerous problems in China. In interviews, Outstanding Lawyers criticized the government for lack of judicial independence,Footnote 74 rising income inequalityFootnote 75 and harsh treatment of migrant workers,Footnote 76 among other issues. Yet, when asked directly for evidence of their own political efficacy, most interviewees struggled to recount a concrete example of how their activities had made a difference. The clearest (and most frequently cited) example of policy influence to emerge from our interviews was a 2010 proposal by Chengdu Outstanding Lawyer Shi Jie 施杰 to increase the penalties for drunk driving, which was incorporated into national-level revisions to the Criminal Law in 2011.Footnote 77 Shi's proposal grew out of what the Chinese media dubbed the “Crazy Buick” case, in which he represented a client sentenced to life imprisonment for killing four people while driving drunk. This unusually long sentence reflected public outcry, rather than the maximum seven-year term for drunk driving legally allowable at the time.Footnote 78 In response, Shi researched penalties for drunk driving in other legal systems and then used his position as a national people's political consultative conference deputy to advocate for stiffer penalties in China as well.

Other than Shi Jie's success, however, tangible examples of political efficacy were hard to come by. A handful of Outstanding Lawyers expressed confidence that their political activities mattered, even if they could not point to specific examples. Lawyers who took this optimistic line typically pointed to the presence of lawyers in government in-and-of-itself as a sign of influence,Footnote 79 or described the frequent cadence of their interactions with government. A Beijing people's political consultative conference deputy, for example, proudly described how government representatives visit her office again and again until she is happy with their responses to her proposals.Footnote 80 Upon reflection, however, most Outstanding Lawyers admitted the difficulty of isolating one's individual effect on a policy outcome,Footnote 81 or blamed their ineffectiveness on bad timing.Footnote 82 A few were especially pessimistic. One Beijing Outstanding Lawyer told us that “little people's words carry little weight” (renwei yanqing 人微言轻),Footnote 83 and the most disillusioned of all interviewees quit participating in representative bodies altogether.Footnote 84 To him, the old adage rings true: “what the Party says counts, the government must take that into account, and the people's representatives understand they do not count.”

Although most Outstanding Lawyers hold modest expectations about their political influence, they still enjoy the process of participation enough to devote significant time to it. One reason is surely that hobnobbing with officials is a source of valuable contacts that assist lawyers in their practice. Among other advantages, close ties to the state can help lawyers to obtain evidence from state agencies, guarantee clients a hearing in front of a sympathetic bench and provide a measure of protection against police harassment and intimidation.Footnote 85 Bragging rights also accompany invitations to meetings with high-level officials, especially when the purpose is to solicit advice.Footnote 86 For example, a particularly proud (albeit prone to exaggeration) Outstanding Lawyer in Beijing opened our conversation by apologizing for his tardiness, caused by a longer-than-expected interview with a state-run newspaper.Footnote 87 After proudly mentioning how he had earned over 400 government awards, he pulled up his WeChat profile to show off a photo with Xi Jinping in the foreground and him smiling nearby. Although he was not a typical interviewee, his story highlights how some lawyers enjoy the status that accompanies political participation.

When we asked Outstanding Lawyers explicitly about their motivation, however, most framed their participation in terms of a sense of responsibility to society.Footnote 88 For these lawyers, raising legal consciousness, promoting justice and contributing to legal development is what separates an Outstanding Lawyer from an average one.Footnote 89 For example, Liu Yongtian 刘用田, an Outstanding Lawyer from Henan, told the Anyang Daily that “being a lawyer is not just about helping clients with their lawsuits or providing them with legal services. Shouldering societal responsibility is even more important.”Footnote 90 Or, in the words of Hunan Outstanding Lawyer Di Yuhua 翟玉华, a “good lawyer needs to put societal responsibility first. He needs to shoulder responsibility and love society.”Footnote 91 Some Outstanding Lawyers also feel a stronger sense of societal responsibility because of the award. One Chengdu Outstanding Lawyer relayed that he feels pressure to “live up to his title” now that others expect more from him.Footnote 92 Echoing these sentiments, two other Outstanding Lawyers talked about how winning the award pushed them to take on even more societal responsibility than before.Footnote 93

Those able to articulate the origins of their sense of societal responsibility traced it back to their values and life experiences. One Outstanding Lawyer from Chongqing pointed to his modest upbringing when explaining his commitment to clients at the bottom of the social hierarchy. His humble beginnings inspired him to return home to start a law firm, and he is now seen as such a leader in his community that even the street vendors call out to him by name.Footnote 94 Others described their volunteer work as a natural result of their place in the professional hierarchy. One interviewee explained that as a lawyer moves up the career ladder, she begins looking for opportunities to serve beyond her day-to-day legal work.Footnote 95 Political participation is one obvious way to give back to a society whose emphasis on legal development has granted lawyers increasing wealth and prestige,Footnote 96 and lawyers should “cherish” the opportunity to make their voice heard inside the system.Footnote 97 An Outstanding Lawyer in Chengdu voiced a desire to “sacrifice oneself to the profession” (toushen dao hangye zhong 投身到行业当中). “Lawyers are not businesspeople,” he emphasized, and people will ultimately judge his life based on the mark he leaves on society and the profession, not his bank account.Footnote 98 Across interviews, lawyers drew on a vocabulary of social responsibility to discuss the meaning they found in their work. For many, the advantage of being close to the state is a chance to contribute to society and, in so doing, to reach towards a mission-driven, purposeful life.

Given the trope that China is a post-ideological society where few believe in communism anymore, the energy that Outstanding Lawyers pour into political participation marks them as an unusually committed group. But it is worth pausing to ask, what do they believe in? Some are dyed-in-the-wool Party loyalists. Heilongjiang Outstanding Lawyer Xu Guiyuan 徐桂元, for example, told reporters that “to walk with the Party is right,” and that Party leadership is “irreplaceable.”Footnote 99 More commonly, though, Outstanding Lawyers express a generic faith in China's trajectory, coupled with patience about how long it might take to reach a stage where reform is no longer necessary. This optimism was shared by Outstanding Lawyers across interview sites. As one put it: “Things may be far from the ideal, but at least things are much better today than they were before.”Footnote 100 So, even if it “requires generations’ worth of hard work … things will work out well in the end.”Footnote 101 In addition, advocates of gradualism often simultaneously warned of the dangers of too rapid a change. Chinese history repeatedly illustrates that “the masses are the ones who ultimately suffer” from political instability.Footnote 102 Reform, on the other hand, “is a step-by-step process” that requires “steady development” rather than “revolution.”Footnote 103 Although a diverse mix of motivations and beliefs inspire Outstanding Lawyers to participate in politics, their commitment to sharing the concerns of their communities with the state is important. This is a significant political role that underscores how much political participation takes place not only under authoritarianism but in a political system that many observers would have said was long drained of true believers.

Conclusion

State-adjacent lawyers shore up the political status quo by moderating dissatisfaction and channelling it into state-run forums designed to keep feedback constructive. This works because enough lawyers (especially outside of China's coastal cosmopolitan megacities) see close ties to the state as desirable, honourable and even cool. Could this change? Of course. Political participation is not the only path to prestige and some lawyers may find other forms of recognition more meaningful than the status afforded by proximity to the state. Moreover, political participation occurs against a broader backdrop of state control,Footnote 104 and state-adjacent lawyers may one day become subject to state censorship, surveillance or sanctions. Gao Zhisheng 高智晟 and Teng Biao 腾彪, for instance, are notable examples of lawyers who were once celebrated by the state who are now alienated from the political system.Footnote 105 Indeed, there are rich possibilities for future work that looks more closely at career trajectories to better understand whether, when and how state-adjacent lawyers move towards or away from the state. For now, this article suggests that if the ranks of state-adjacent lawyers hollow out, or if it becomes hard to find new recruits, it could be an early warning of unrest. After all, a regime in trouble is one where citizens no longer want the symbolic capital it has to offer.

State-adjacent lawyering is also part of an enduring strategy of Chinese statecraft. From the Leninist transmission belts that undergirded Mao's mass line to the reform era's reliance on policy advice from technocrats, the CCP has a long history of citizen consultation.Footnote 106 However, the Party has also exhibited a long-standing preference for atomized, individual political participation over lobbying by independent interest groups. Given this history, it is not surprising that China's Outstanding Lawyers lack a sense of collective identity. Although they typically know other award winners in their hometown because they share professional and social circles, they are rarely aware of Outstanding Lawyers elsewhere. Neither national meetings (nor a WeChat group) bind together China's Outstanding Lawyers, despite the commonalities shared by this group.

Yet, the form of citizen consultation also adapts to the times. One characteristic of the post-Mao era is the resurgent status of white-collar professionals, buoyed by state discourse about the importance of professionalism. At the same time, ties between local officials and the people are “looser, more ephemeral and more impersonal” than they once were and there is a need for new brokers to link state and society.Footnote 107 Professionals have stepped into this role, aided by an aura of professional authority and recognized by the authorities as citizen-specialists whose work can stabilize society and sustain the conditions for economic growth. Existing work shows how other types of professionals, such as Chinese businesspeople,Footnote 108 journalistsFootnote 109 and social workersFootnote 110 are drawn into politics and often perform the same critical functions of information provision and persuasion. Beyond lawyers, professionals are important participants in Chinese politics, an insight in its own right that also opens up opportunities for comparisons with other authoritarian regimes.

Among professionals, whose voice matters and why? For lawyers, being a domestically educated man with a leadership position in the local bar and close ties to the government is highly correlated with opportunities for political participation. These opportunities would be difficult to imagine for the average Chinese lawyer who is hustling for business inside a law firm that typically provides little professional support.Footnote 111 As odd as it first seems to talk about inequality and political participation in an authoritarian context, it is also clear that opportunities for political participation in China are unequally distributed. Those interested in extending the argument might look at how political participation intersects with age, gender and class among other recipients of official honours such as “outstanding model workers” (quanguo laodong mofang 全国劳动模仿) or “outstanding entrepreneurs” (quanguo youxiu qiye jia 全国优秀企业家). For lawyers, at least, the emphasis placed on Party loyalty is plainly growing. Additions to Article 4 of the 2018 ACLA Charter prioritize the development of the CCP inside the legal profession,Footnote 112 and Party activities among Chinese lawyers are increasingly tracked and celebrated.Footnote 113 In addition, ACLA handed out the inaugural Outstanding Party Lawyer Award in July 2018 to lawyers especially committed to the socialist rule of law, the Party and Xi Jinping thought.Footnote 114 Is demonstrated loyalty to the Party now the prerequisite for lawyers to exercise a voice in Xi Jinping's China? That increasingly appears to be the case, and marks a real shift for a bar accustomed to giving a wider swath of its membership a chance to stand close to the state and offer suggestions for change.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kevin O'Brien, Maria Repnikova, Cristián Villalonga Torrijo and the reviewers for helpful comments at various stages of the project. This article has also benefited from feedback of audiences at the Center for the Study of Law and Society at Berkeley Law, the University of Wisconsin Law School, and the 2019 Law and Society Association Meeting. We are deeply grateful to Aqua Huang and Lizzie Shan for first-rate research assistance. The research was approved by the University of California, Berkeley IRB Protocol ID 2016-10-9238.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Lawrence J. LIU is a PhD student in the Jurisprudence and Social Policy Program at Berkeley Law as well as a JD candidate at Yale Law School. His current research focuses on state–society relations, regulatory politics and the ways in which “law” legitimizes or challenges governance efforts in contemporary China.

Rachel E. STERN is a professor of law and political science in the Jurisprudence and Social Policy Program at Berkeley Law, where she currently holds the Fong Chair in China studies. Her research looks at law in mainland China and Hong Kong, especially the relationship between legal institution building, political space and professionalization.

Appendix

Table 1: Interview List