Article contents

Notes on Aristotle, Poetics 13 and 141

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Extract

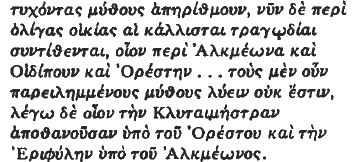

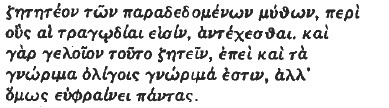

In an important recent article T. C. W. Stinton reaffirmed the case that  in Aristotle's Poetics, ch. 13, has a wide range of application. I do not wish to dispute the general conclusion of what seems to me a masterly analysis of the question but simply to discuss two areas where Stinton's argument may be thought defective–the interpretation of the examples given by Aristotle in Poetics 13, 5 3all and 53a2O–1 and the problem of the contradiction between 13, 53a13–15 and 14, 54a4–9.

in Aristotle's Poetics, ch. 13, has a wide range of application. I do not wish to dispute the general conclusion of what seems to me a masterly analysis of the question but simply to discuss two areas where Stinton's argument may be thought defective–the interpretation of the examples given by Aristotle in Poetics 13, 5 3all and 53a2O–1 and the problem of the contradiction between 13, 53a13–15 and 14, 54a4–9.

Information

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1979

References

page 77 note 2 ‘Hamartia in Aristotle and Greek Tragedy’’, CQ N.S. 25 (1975), 221–54.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 77 note 3 e.g. Else, G. F., Aristotle's Poetics: the Argument (Harvard, 1957), pp.391–8,CrossRefGoogle ScholarBremer, J. M., Hamartia (1968), Lucas, D. W., ed. 1968, pp.144–6 and 304. Full references in Stinton's article.Google Scholar

page 77 note 4 The Greek and Roman Critics (London, 1965), p.80Google Scholar n.3. So far as I know, this is an original suggestion, though Grube makes it with absolute confidence.

page 78 note 1 Cf. also Else, p.391, for similar arguments. Stinton has now kindly agreed that it is wrong to detach the second set of examples from the prescription as a whole.

page 79 note 1 Stinton, p.227 n.l, cl. Met. 948a14. Possible instances in the Poetics are e.g. 1,47b 17–23 (perhaps rather a case of sophistic argument), 8.51a25–6, 11, 52b12–13 (see Lucas ad loc; contra B. R. Rees, G & R 19 (1972), 7 f.), 11, 52a24–6 (if ![]() = ‘reversal of character expectation’’. Cf. p.89 n.3 below).

= ‘reversal of character expectation’’. Cf. p.89 n.3 below).

page 79 note 2 See Lucas on 13, 53a11. But even in this example Sophocles' Thyestes in Sicyon apparently had Thyestes commit incest with his daughter deliberately (references in Else, pp.395–6).

page 79 note 3 Stinton's somewhat unkind paraphrase of Else, p.394 and n.97. But it is what Else's argument amounts to.

page 79 note 4 Stinton, p.227 cl. Poetics 13, E.N. 3.1, 1110a28, the sophistic Dialexeis, DK ii.410. Cf. Antiphanes, fr. 191K.E.N. 3.1, 1110a28 does not exclude Orestes' matricide from consideration in Poetics 13: for the arguments see Stinton, pp.229–35. One may wonder, in any case, whether too much stress has not been laid upon E.N. 3.1, 1110a28. Is it not possible that Aristotle is intemperately rejecting the possibility of justifiable deliberate matricide simply because he finds the arguments used by the Euripidean Alcmeon so offensive? Moralists often condemn the general principle because they are outraged by the particular indefensible instance.

page 80 note 1 ![]()

page 80 note 2 Lucas on 13, 53a20, following Else, p.394 n.97, remarks: ‘Since he returned unrecognized to his own country, he was certainly a cause of ![]() in others.’’ But it is hard to believe that Aristotle could have meant that Orestes fell into misfortune because of other people's failure to recognize him. The fact that Clytemnestra and Aegisthus do not recognize Orestes until too late certainly facilitates Orestes' killing of them, but it is not the cause of his misfortune. Stinton agrees with me that ‘Orestes is certainly there as an example of deliberate matricide.’’

in others.’’ But it is hard to believe that Aristotle could have meant that Orestes fell into misfortune because of other people's failure to recognize him. The fact that Clytemnestra and Aegisthus do not recognize Orestes until too late certainly facilitates Orestes' killing of them, but it is not the cause of his misfortune. Stinton agrees with me that ‘Orestes is certainly there as an example of deliberate matricide.’’

page 80 note 3 Meleager: Else, pp.394–5, Lucas, pp.146 and 304. Telephus' murder of his uncles (treated in Sophocles' Aleadae and probably also Aeschylus' Mysians), among other possibilities, could not have been a ‘mistake of fact’’.

page 80 note 4 In itself a reference to conscious matricide is not precluded by E.N. 3.1, 1110a28 (cf. p.79 n.4 above) but Aristotle seems to have been particularly struck by the inadequacy of Alcmeon's plea of compulsion. Of course I do not put much weight on this argument in isolation, since as Stinton points out to me ‘Aristotle might say that it was ridiculous for Alcmeon to claim that his act was compulsory, and therefore worthy of (full) pardon, but might still allow that the command of Ampharaus, which presumably carried with it a curse and the threat of his Erinyes if it was disobeyed, would be a mitigating circumstance', which on Stinton's analysis (with which I am in general agreement) is a sufficient condition for hamartia.

page 81 note 1 Webster, T. B. L., Hermes 82 (1954), 305, Else, p.391 n.86. See further my text note.Google Scholar

page 81 note 2 I hope this is not ‘implausible special pleading’’ (Stinton on the Else/Bremer approach to the examples). After all, Stinton himself takes it for granted that the reference to Oedipus in ch. 13 is to the Sophoclean Oedipus, not merely the Oedipus of Greek tragedy in general. In his letter to me Stinton agrees that Aristotle must have been thinking of particular versions of the stories, but argues that this does not necessarily mean that he was referring to particular plays, despite the reference to Sophocles' Oedipus, since it was famous in a way that Astydamas' Alcmeon could not have been. He also points out that if the version in which Alcmeon killed his mother when he was mad was Astydamas' version, then Aristotle in ch. 14 of the Poetics would be regarding Alcmeon as acting ![]() whereas by the terminology E.N. 3.1. he ought to be acting

whereas by the terminology E.N. 3.1. he ought to be acting ![]() He further argues that, although Aristotle is lax about examples and it might be thought that the precise distinctions of E.N. 3.1 are irrelevant to P o. 14, there is no hint in Po. 14 that Aristotle is thinking of acts done in a fit of madness rather than just ignorance, hence prima facie Astydamas' version was peculiar to himself, whereas the standard version, despite Antiphanes, was presumably that of Sophocles' Epigoni, and therefore the most likely reference in ch. 13 is to the version where Alcmeon killed his mother deliberately, under compulsion. Against this I would argue that if the distinction between

He further argues that, although Aristotle is lax about examples and it might be thought that the precise distinctions of E.N. 3.1 are irrelevant to P o. 14, there is no hint in Po. 14 that Aristotle is thinking of acts done in a fit of madness rather than just ignorance, hence prima facie Astydamas' version was peculiar to himself, whereas the standard version, despite Antiphanes, was presumably that of Sophocles' Epigoni, and therefore the most likely reference in ch. 13 is to the version where Alcmeon killed his mother deliberately, under compulsion. Against this I would argue that if the distinction between ![]() means anything in the context of P o. 14, then it only knocks out the equation of Astydamas' version with that mentioned by Antiphanes. But I do not in any case accept that the distinction could be important, since in ch. 14 Aristotle is only operating within the frame of

means anything in the context of P o. 14, then it only knocks out the equation of Astydamas' version with that mentioned by Antiphanes. But I do not in any case accept that the distinction could be important, since in ch. 14 Aristotle is only operating within the frame of ![]() And given Antiphanes' evidence, I do not see that for Aristotle, writing towards the end of the fourth century, from an emphatically fourth-century standpoint, the ‘standard version’’ could not have been one where Alcmeon killed his mother

And given Antiphanes' evidence, I do not see that for Aristotle, writing towards the end of the fourth century, from an emphatically fourth-century standpoint, the ‘standard version’’ could not have been one where Alcmeon killed his mother ![]() Of course after a certain point such detailed arguments as these cease to have much contact with the reality of Aristotle's rather sparse text. None the less, I believe that the cumulative case for taking the example of Alcmeon as a reference to Astydamas’’ version is quite good.

Of course after a certain point such detailed arguments as these cease to have much contact with the reality of Aristotle's rather sparse text. None the less, I believe that the cumulative case for taking the example of Alcmeon as a reference to Astydamas’’ version is quite good.

page 82 note 4 The fact that the mode recommended as best in ch. 14 is not mentioned at all in ch. 13 might seem to suggest that the final preference of ch. 14 is an afterthought, rather than a properly considered change of mind. But it is hardly likely that when writing ch. 13 Aristotle should have forgotten of the existence of plays like the Ion, Cresphontes, and Ipbigeneia in Tauris, and the emphatic phraseology of 13, 53a14–15 ![]()

![]() and 21–30 must be intended to reject more than the mode

and 21–30 must be intended to reject more than the mode ![]()

![]() (13, 52b36–7), and must in fact also contain an implicit polemic against the Cresphontes schema.

(13, 52b36–7), and must in fact also contain an implicit polemic against the Cresphontes schema.

page 82 note 1 Art. cit. 252–4.

page 82 note 2 Originally suggested by Lessing and accepted by e.g. Vahlen, J., Beiträge zu Aristoteles Poetik, ed. Schone, H. (Leipzig, 1914), pp.53–4,Google Scholarde Montmollin, D., La Poétique d'Aristote. texte primitif et additions ultérieures (Neuchatel, 1951), pp.338–9, Else, pp.450–1, Lucas, p.155 (tentatively).Google Scholar

page 82 note 3 This is not to exclude the possibility that some of the discrepancies between chs. 13 and 14 can be explained by distortion due to difference of emphases: cf. p.83 n.2 below.

page 83 note 1 Hubbard, M. E., Ancient Literary Criticism (ed. Russell, D. A. and Winterbottom, M. M., Oxford, 1972), p.109Google Scholar n.5. Cf. Glanville, I. M., ‘Tragic Error’’, CQ 43 (1949), 47.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 83 note 2 14, 54a3–4; it is quite clear in ch. 14 that whether or not ![]() comes into play depends on the motivation of the agent, not on whether the deed is done or not. Cf. also 14, 53b38–9, where the situation where someone in possession of the facts is about to act, but fails to do so, is stigmatized for having

comes into play depends on the motivation of the agent, not on whether the deed is done or not. Cf. also 14, 53b38–9, where the situation where someone in possession of the facts is about to act, but fails to do so, is stigmatized for having ![]() The same accusation is levelled implicitly against the situation where the agent acts knowingly (14, 54a2). It is misleading to say ‘Aristotle passes no judgement on class (2), acts done knowingly’’ (Stinton, p.234), or ‘The schema is not uncommon … it is not excluded as untragic by Aristotle, but simply not preferred, as belonging to the simple not the complex plot’’ (Stinton, p.252). Although the superiority of the complex plot is certainly of some relevance, in the first instance Aristotle is assessing the various possibilities according to the criteria of

The same accusation is levelled implicitly against the situation where the agent acts knowingly (14, 54a2). It is misleading to say ‘Aristotle passes no judgement on class (2), acts done knowingly’’ (Stinton, p.234), or ‘The schema is not uncommon … it is not excluded as untragic by Aristotle, but simply not preferred, as belonging to the simple not the complex plot’’ (Stinton, p.252). Although the superiority of the complex plot is certainly of some relevance, in the first instance Aristotle is assessing the various possibilities according to the criteria of ![]() and arousal of the tragic emotions. The situation where the agent acts knowingly clearly involves

and arousal of the tragic emotions. The situation where the agent acts knowingly clearly involves ![]()

![]() and equally clearly the structure of Aristotle's argument implies that this is so, even though the text at this point is little more than a series of jottings. But, though Stinton overlooks this important fact, it does not necessarily go against his argument for a wide–ranging application for

and equally clearly the structure of Aristotle's argument implies that this is so, even though the text at this point is little more than a series of jottings. But, though Stinton overlooks this important fact, it does not necessarily go against his argument for a wide–ranging application for ![]() in ch. 13. See Stinton, pp.234–5. To the objection: ‘Why does Aristotle here pointedly reject acts done knowingly as having

in ch. 13. See Stinton, pp.234–5. To the objection: ‘Why does Aristotle here pointedly reject acts done knowingly as having ![]() if he is prepared to allow them as

if he is prepared to allow them as ![]() in ch. 13?’’ the answer might be that the distortion of emphasis occurs because Aristotle has effectively forgotten that he is supposed to be assessing the

in ch. 13?’’ the answer might be that the distortion of emphasis occurs because Aristotle has effectively forgotten that he is supposed to be assessing the ![]() in the light of the whole

in the light of the whole ![]() and has simply become interested in calculating the relative merits of the various

and has simply become interested in calculating the relative merits of the various ![]() for their own sake (this goes some way to explaining the preference for a ‘happy ending’’ plot in ch. 14, as argued below). Stinton, however, is right that Aristotle does not exclude schema (2) (Medea) as ‘untragic’’.

for their own sake (this goes some way to explaining the preference for a ‘happy ending’’ plot in ch. 14, as argued below). Stinton, however, is right that Aristotle does not exclude schema (2) (Medea) as ‘untragic’’.

page 83 note 3 The term ![]() is carefully analysed by B. Rees, R., ‘Pathos in the Poetics of Aristotle’’, G & R 19 (1972), 1–11, though he does not deal directly with the problems of ch. 14.Google Scholar

is carefully analysed by B. Rees, R., ‘Pathos in the Poetics of Aristotle’’, G & R 19 (1972), 1–11, though he does not deal directly with the problems of ch. 14.Google Scholar

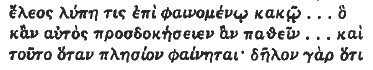

page 84 note 1 Stinton, pp.253–54, working from Glanville, p.55 nn.6, 7, cl. Rhet. 1385b13, 1386a34, 1382a21 (below, p.86 n.2). The point was already made by Vahlen, pp.53 ff., and accepted by Else, p.451. That it is relevant to Poetics 14 is suggested by 14, 53b 18 ![]()

page 84 note 2 Rees, art. cit. 5, does not come to grips with this difficulty. Clanville, pp.52 ff., argues that realization before action ‘rescues both man and God from a moral condemnation through which pity is roused for what is human only at the cost of misrepresenting what is divine.’’ On the unlikelihood of this explanation see Stinton, p.253.

page 85 note 1 As Bywater remarks on 13, 53a5–6, ‘The antithesis in the text… is too strongly put’’, cf. also Else, p.373.

page 85 note 2 See end-note, pp.92–4 below.

page 85 note 3 Nothing more is known of this play.

page 85 note 4 For deaths etc. on stage see Lucas on 11, 52b 10. The nearest thing to the representation of an actual killing is Ajax' suicide, which occurs (arguably) only just out of sight of the audience. Later such restraints were relaxed, as the fame of Timotheus of Zacynthus (Scbol. Ai. 864) attests.

page 85 note 5 Note, however, that Aristotle does seem to accept as a useful criterion whether a thing comes off on stage: 13, 53a27–8, cf. 17, 55a22 ff.

page 86 note 1 This is not the place to become embroiled in discussion of catharsis. The formula in the text is Hubbard, , op. cit., pp.88–9.Google Scholar Else, pp.423–50, while denying that catharsis is the ‘end’’ of tragedy (p.439), still manages to make it relevant to Aristotle's preference for realization before action. But his analysis depends not only on an idiosyncratic interpretation of catharsis, and an argument that is not easy to follow, but also upon an erroneous acceptance of Bywater's view thai recognition after action still involves an element of ![]()

page 86 note 2 Cf. Rhet. 1385b13 ff. ![]()

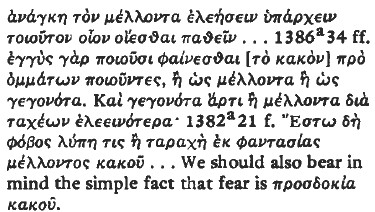

page 86 note 3 De Esu Carnium 998E ![]()

page 87 note 1 ![]() is the desire to understand: Rhet. 1371a31–4 (cf. b5–ll), Met. 982b 17–19.

is the desire to understand: Rhet. 1371a31–4 (cf. b5–ll), Met. 982b 17–19.

page 87 note 2 The formulation is Else, p.420.

page 87 note 3 See also Rees, , art. cit., p.4, for a similar interpretation.Google Scholar

page 87 note 4 See Dodds on Bacch. 52, Barrett on Hipp. 41–50, and Owen on Ion 70–1. Broader studies of Euripides' partiality for teasing the expectations of his audience are Winnington-Ingram, R. P., ‘Eurpides: Poietes Sophos’’, Arethusa 2 (1969), 127–42,Google Scholar and Arnott, G., ‘Euripides and the Unexpected’’, G & R 20 (1973), 49–64.Google Scholar

page 88 note 1 Eur, . Hipp. 451–6Google Scholar must give pause– see Barrett ad loc. Lloyd-Jones, , The Justice of Zeus (Berkeley, 1971), p.198Google Scholar n.124, is not (in my opinion) an adequate reply. One of the most commonly used arguments–that use of ironic effects necessarily presupposes audience foreknowledge–is also unconvincing. See p. 90 n.2 below.

page 88 note 2 13, 53a34;9, 51b36–9, 13, 53a34–5; 18, 56a27–32.

page 88 note 3 9, 51b23–6 ![]()

The external evidence is inconclusive. The best discussion is Else, pp.318 ff., though his interpretation of ![]() as ‘even the familiar names’’ is strained (but does not affect the argument).

as ‘even the familiar names’’ is strained (but does not affect the argument).

page 89 note 1 In the first sentence of ch. 11 ![]()

![]() refers back to 9, 52a4: so Rostagni, A., Aristotele Poetica (2nd edn.Turin, 1945), p.60,Google ScholarGlanville, , ‘Note on Peripeteia’’, CQ 41 (1947), 73–8CrossRefGoogle Scholar (on the basis of an unpublished paper by F. M. Cornford), Else, p.344, Lucas. D.129. Rbet. 1371bll helos the case.

refers back to 9, 52a4: so Rostagni, A., Aristotele Poetica (2nd edn.Turin, 1945), p.60,Google ScholarGlanville, , ‘Note on Peripeteia’’, CQ 41 (1947), 73–8CrossRefGoogle Scholar (on the basis of an unpublished paper by F. M. Cornford), Else, p.344, Lucas. D.129. Rbet. 1371bll helos the case.

page 89 note 2 This analysis is essentially Bywater's.

page 89 note 3 So, emphatically, Else, p.330 n.103; the immediate context and the ![]() and

and ![]() contexts discussed above combine to make this interpretation practically certain. But this interpretation, because of the link between 11, 52a23 and 9, 52a4 (n.l above), implies that

contexts discussed above combine to make this interpretation practically certain. But this interpretation, because of the link between 11, 52a23 and 9, 52a4 (n.l above), implies that ![]() in ch. 11 should be taken as ‘reversal of audience expectation’’. Although I agree with this view (see e.g. Else, p.345, Turner, P., ‘The Reverse of Vahlen’’, CQ N.S. 9 (1959), 207–15,CrossRefGoogle Scholar Hubbard, p.104 n.5), which is consistent with Aristotle's belief in the ignorance of the contemporary audience (p.88 above), it hardly affects the argument which view of

in ch. 11 should be taken as ‘reversal of audience expectation’’. Although I agree with this view (see e.g. Else, p.345, Turner, P., ‘The Reverse of Vahlen’’, CQ N.S. 9 (1959), 207–15,CrossRefGoogle Scholar Hubbard, p.104 n.5), which is consistent with Aristotle's belief in the ignorance of the contemporary audience (p.88 above), it hardly affects the argument which view of ![]() is preferred. Even if

is preferred. Even if ![]() means ‘reversal of character expectation’’, the significance of this reversal lies in the transference of the emotions of the characters to the audience. Cf. next note.

means ‘reversal of character expectation’’, the significance of this reversal lies in the transference of the emotions of the characters to the audience. Cf. next note.

page 90 note 1 Lucas, D. W., ‘Pity, Terror, and Peripeteia’’, CQ N.S. 12 (1962), 52–60, esp. 54 ff.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page 90 note 2 Lucas appears to concede this possibility in ‘Pity’’ 53 (following Else, p.346), but rejects it in his edition (p.133) on the ground that ‘Even with regard to Oedipus the audience is clearly assumed to know from the start all that in the course of the play Oedipus discovers about himself’’ (cf. Glanville, , ‘Note on Peripeteia’’, p.77).Google Scholar But this argument simply ignores the possibility that as far as Aristotle was concerned the audience could feel surprise of a detective-story type. Not only, as Else points out, can it be argued that ‘Our knowledge that Oedipus’’ situation is going to be reversed is “accidental” in Aristotle's sense. It is not an expectation based on the facts as they are given in the course of the play', but also Aristotle's belief that ‘even the familiar stories are familiar only to a few’’ means that from his point of view the whole question of advance knowledge of a given plot is simply irrelevant (cf. Else, p.346 n.10). I may add that the natural interpretation of 11, 52a24–6 is that the audience is assumed not to know the Oedipus story (cf. Hubbard ad loc.). None of this necessarily means that Aristotle is insensitive to ironic effects in tragedy, as both Else and Lucas imply, though admittedly he says nothing about them. It is often argued that the mere presence of ironic effects of the kind used so extensively throughout the Oedipus necessarily presupposes audience foreknowledge of the story, but although I do not doubt that some of Sophocles' audience had that foreknowledge, or that he exploited it to the full by the use of ironic effects, their mere presence does not prove audience foreknowledge. Irony of course can work retrospectively. This is a familiar enough technique in Greek and Latin poetry (e.g. Anacreon 358 PMG, as interpreted by Harvey, A. E., ‘Homeric epithets in Greek lyric poetry’’, CQ N.S. 7 (1957), 213).CrossRefGoogle Scholar It should also be familiar enough to any follower of modern theatre or cinema or indeed to anyone who reads a detective story. One does not deny the existence of the clues Hitchcock gives his viewers in the first part of Psycho simply because their significance is not appreciated when they actually appear on screen, or the ironic light thrown on everything that precedes the solution by the solution itself in Agatha. Christie's classic detective story, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. The criterion: would the audience appreciate it at the time?–is altogether too crude a critical tool. Thus Aristotle's emphasis on the techniques of suspense is in theory by no means incompatible with an awareness of the significance of ironic effects. In fact, if the ![]() felt by the audience at the

felt by the audience at the ![]() of the Oedipus is of a detectivestory kind, it is actually enhanced by the previous ironic effects, whose true meaning is only made clear by the

of the Oedipus is of a detectivestory kind, it is actually enhanced by the previous ironic effects, whose true meaning is only made clear by the ![]() itself. Aristotle's way of looking at the Oedipus, which assumes an audience without advance knowledge of the story, therefore gives the ironic effects a somewhat different value than they would have had for some of the fifth-century audience, but it need not be taken to devalue them completely.

itself. Aristotle's way of looking at the Oedipus, which assumes an audience without advance knowledge of the story, therefore gives the ironic effects a somewhat different value than they would have had for some of the fifth-century audience, but it need not be taken to devalue them completely.

page 91 note 1 e.g. Euripides' Bacchae and Heracles; probably Astydamas' Alcmeon and Sophocles' Odysseus Akantboplex.

page 91 note 2 This seems to have been appreciated by Glanville, , ‘Note on Peripeteia’’, p.77Google Scholar n.l: ‘In plays with a happy ending, the tragic emotion … depends on the outcome not being a foregone conclusion …’’, though her parallel argument (p.77) that ‘the whole emotional effect of the play’’ (viz. the Oedipus) ‘depends on their knowing the outcome from the first, since fear is ![]() ignores Aristotle's belief in the ignorance of the audience and the possible role of retrospective irony (p.90 n.2 above), and also seems to imply quite wrongly that

ignores Aristotle's belief in the ignorance of the audience and the possible role of retrospective irony (p.90 n.2 above), and also seems to imply quite wrongly that ![]() is not a significant factor in ‘happy ending’’ plays.

is not a significant factor in ‘happy ending’’ plays.

page 91 note 3 The Cresphontes did not have an explicit prologue. See Musso, O., Euripide, Cresfonte (Milan, 1974), p.XXIV.Google Scholar

page 91 note 4 It is not quite explicit–see p.87 n.4 above–but presumably the audience would feel fairly sure of a happy ending after it, though they would undoubtedly get some shocks along the way.

page 91 note 5 Documentation in Haigh, A. E., The Attic Theatre (2nd edn.Oxford, 1898), pp.99–102,Google Scholar cf. The Tragic Drama of the Greeks (Oxford, 1896), p.448 n.4.Google Scholar

page 92 note 1 e.g. the studies of Euripides' dramatic technique cited above, p.87 n.4, or Taplin, O., The Stagecraft of Aeschylus (Oxford, 1977). Note, e.g., Taplin's contention that the so-called ‘carpet scene’’ in the Agamemnon ‘is meant to be puzzling’’ (p.316).Google Scholar

- 7

- Cited by