No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

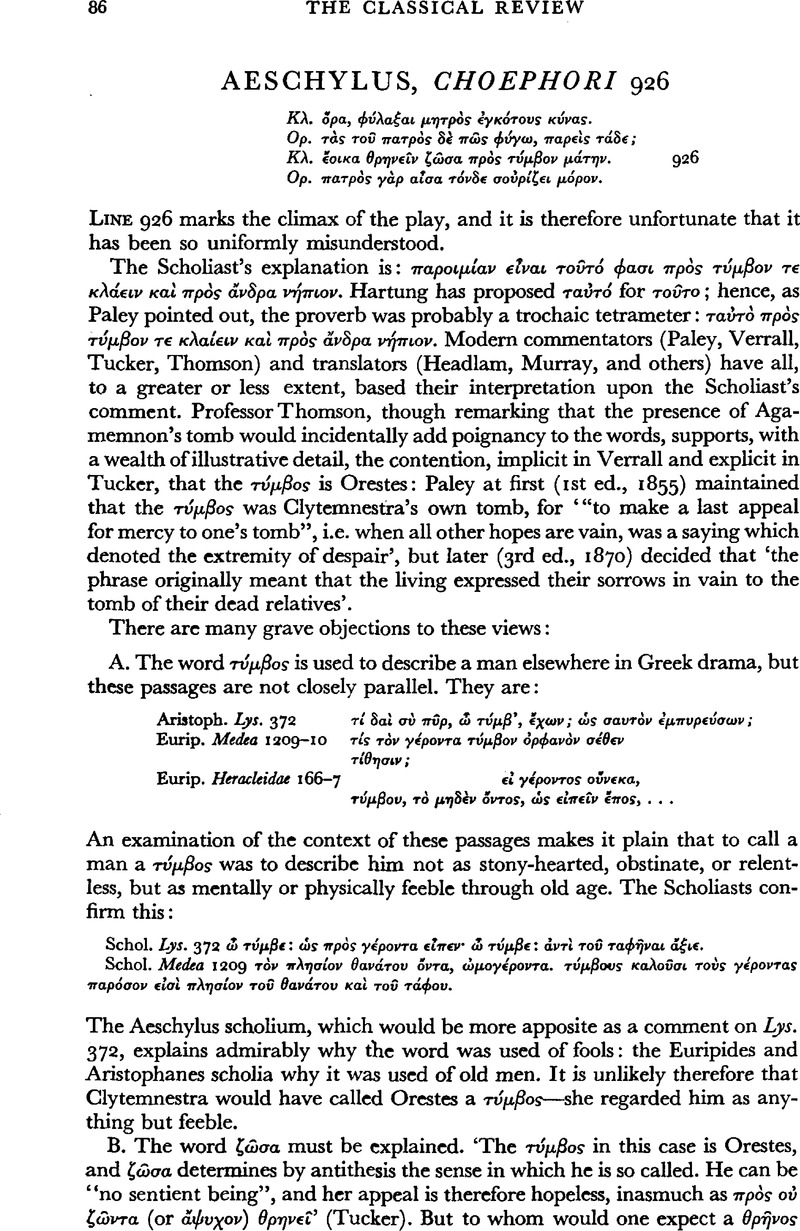

Aeschylus, Choephori 926

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2009

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1954

References

page 87 note 1 Quoted by Paley with Hermann's alteration οὐ θρῆνον, ‘i.e. not uselessly to be-wail my fate’, for Paley thought that a θρῆνος would be regarded as useless. But see below.

page 88 note 1 An interesting account of the function of funeral rites in primitive Religion is contained in Frazer's Fear of the Dead in Primitive Religion, vol. i, Lecture vi. The primitive man conducts ceremonies and offers presents before the tomb of his relative not so much out of concern for the dead man's welfare as from a fervent desire that he should ‘go away’ and not return. ‘If persuasion fails to keep the ghosts at bay, he resorts to force or fraud.’ Clytemnestra's conduct in this respect is curiously reversed. She tries force, and fails; then she resorts to persuasion—and fails again. (See also Headlam, , ‘Ghostin raising, Magic, and the Underworld’, C.R. xvi, pp. 52 ff.)Google Scholar

page 88 note 2 See ‘Excursus on the Ritual Forms prefore served in Greek tragedy’, by Gilbert Murray, contained in Harrison, J. E., Themis, pp. 341 ff.Google ScholarPickard-Cambridge, A. W., in his Dithyramb, Tragedy and Comedy, pp. 185 ff.Google Scholar, opposes Murray's views, but the argument is concerned more with the origin than with the content of Greek tragedy.

page 89 note 1 See B. Hübner, De temporum qua Aeschylus utitur praesentis praecipue et aoristi varietate. He writes, giving many examples (pp. 118–19): ‘Ex liberiore enim quadam sentiendi et cogitandi ratione fit, ut etiam ad res, quae praesentes non sunt, praesentis usus transferatur…. Quo fit, ut quod praesens vocatur tempus cancellis utrimque patefactis nunc in praeteritum rerum statum refugiat nunc in futurum procurrat.’

page 89 note 2 Rites to the dead were performed in the evening (cf. Lawson, J. C., ‘The Evocation of Darius’, C.Q. xxviii. 79 ff.)Google Scholar, and Orestes enters the palace in the late evening (Cho. 660–1). So Clytemnestra has in mind a θρῆνος which she thinks has only recently been performed. Moreover, in the first conversation between Orestes and Clytemnestra (668–781), the Chorus, having been ordered σιγᾶνθ᾽ ὄπου δεῖ λέγειν τὰ καίρια (582), do not say a word, and, unless Headlam's view of vv. 691–9 is correct, Electra also is silent. It is possible therefore that the Chorus and Electra are there pretending that they are still engaged in the ritual which Clyteevening mnestra had ordered, so that, when Orestes is about to kill her, Clytemnestra may even believe that the θρῆνος is still continuing.