1 MOTIVATION AND INTRODUCTION

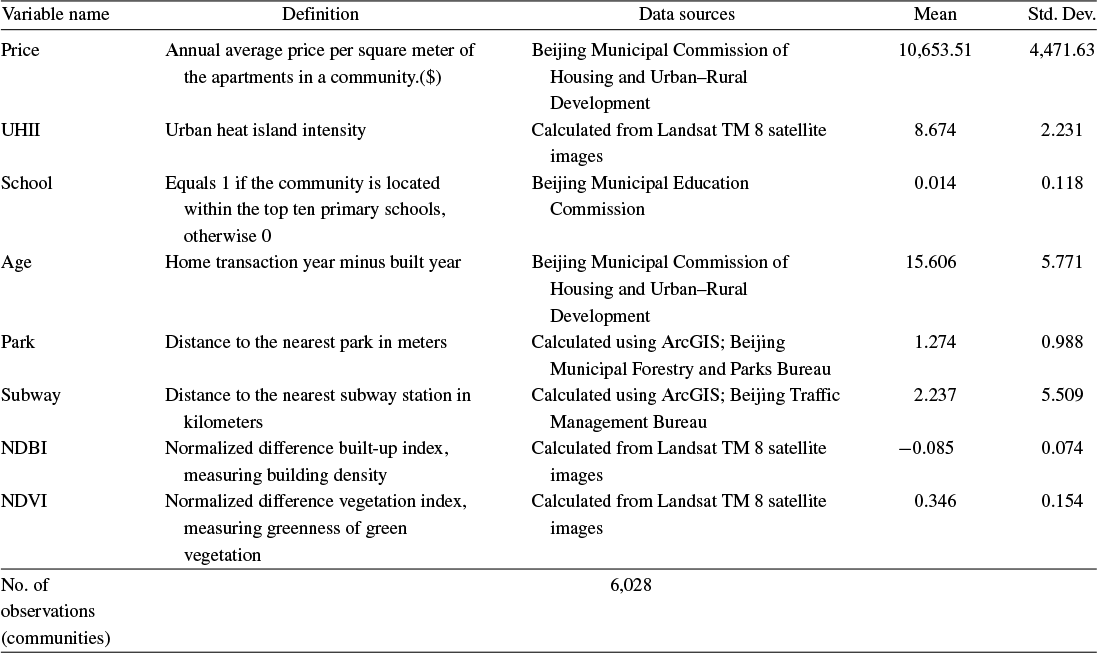

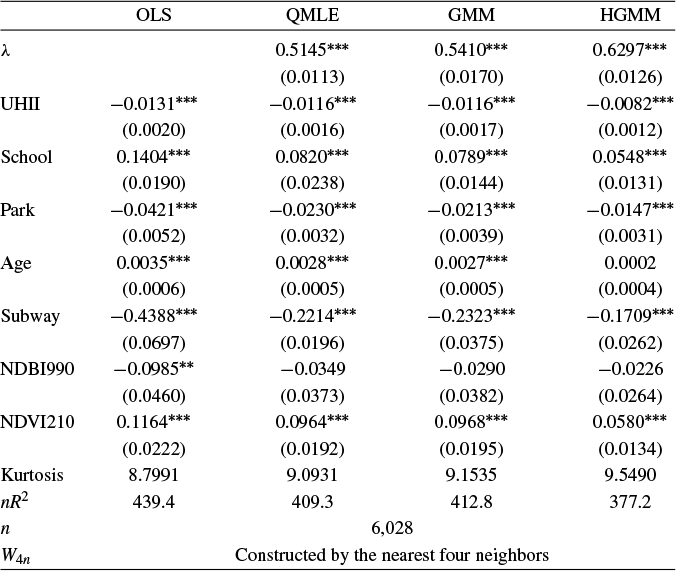

In recent years, spatial econometric models have become increasingly popular in investigating spillover effects or competition in various fields of economics, including but not limited to tax competition (Lockwood and Migali, Reference Lockwood and Migali2009; Lyytikäinen, Reference Lyytikäinen2012, Baskaran, Reference Baskaran2014), the relationship between democracy and economic growth (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu2019), the impact of social networks on education (Calvó-Armengol, Patacchini, and Zenou, Reference Calvó-Armengol, Patacchini and Zenou2009; Liu and Lee, Reference Liu and Lee2023), and international trade (Lee, Yang, and Yu, Reference Lee, Yang and Yu2023). The spatial autoregressive (SAR) model is one of the most prevalent models in this area. Correspondingly, several estimation methods have been proposed and thoroughly studied for the SAR model, including quasi maximum likelihood estimation (QMLE), two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimation, the best instrumental variable (IV) estimation, the generalized method of moments (GMM), etc. The estimation methods mentioned above work well when the disturbances are short-tailed distributed, but are very sensitive to outliers or long-tailed disturbances. Our simulation studies reveal that these classical estimators tend to possess large variances in such circumstances. However, data with outliers or long-tailed disturbances are prevalent in economics and finance, e.g., housing prices, students’ academic grades, income, yield rates of stocks or other financial assets, and the air quality index. As an example, this article employs an SAR model to investigate the housing prices in Beijing and documents that the estimated disturbances are long-tailed. This observation motivates us to develop some robust estimation methods for the SAR model that can better handle such scenarios.

This article is inspired by the Huber M-estimation proposed in Huber (Reference Huber1964), one of the mainstream robust estimation methods. An M-estimator is defined as

![]() $\arg \min _{\theta }\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\rho (x_{i},\theta )$

, where

$\arg \min _{\theta }\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\rho (x_{i},\theta )$

, where

![]() $\rho (\cdot )$

is a loss function. It is well known that least squares estimators are not robust to outliers and long-tailed disturbances for linear regression models. Huber (Reference Huber1964) combines the square loss function and the absolute value loss function to form a new loss function. M-estimators based on this loss function enjoy the merits of both least squares estimators and least absolute deviation (LAD) estimators, i.e., it is robust to outliers and more efficient than LAD estimators. The original Huber M-estimators are based on the assumption that regressors are exogenous. A few researchers manage to develop Huber-type estimators that accommodate endogeneity. Wagenvoort and Waldmann (Reference Wagenvoort and Waldmann2002) extend the idea of generalized M-estimators in Mallows (Reference Mallows1975) to develop two robust estimators for a linear model in the presence of endogeneity, namely, the two-stage generalized M-estimator (2SGM) and robust GMM estimator, respectively.Footnote

1

Kim and Muller (Reference Kim and Muller2007) generalize 2SLS estimation to the two-stage Huber estimation for a linear regression model with endogenous regressors. Sølvsten (Reference Sølvsten2020) proposes an estimator that is robust to outliers in a linear model with many IVs. All the works above deal with linear regression models with independent data.

$\rho (\cdot )$

is a loss function. It is well known that least squares estimators are not robust to outliers and long-tailed disturbances for linear regression models. Huber (Reference Huber1964) combines the square loss function and the absolute value loss function to form a new loss function. M-estimators based on this loss function enjoy the merits of both least squares estimators and least absolute deviation (LAD) estimators, i.e., it is robust to outliers and more efficient than LAD estimators. The original Huber M-estimators are based on the assumption that regressors are exogenous. A few researchers manage to develop Huber-type estimators that accommodate endogeneity. Wagenvoort and Waldmann (Reference Wagenvoort and Waldmann2002) extend the idea of generalized M-estimators in Mallows (Reference Mallows1975) to develop two robust estimators for a linear model in the presence of endogeneity, namely, the two-stage generalized M-estimator (2SGM) and robust GMM estimator, respectively.Footnote

1

Kim and Muller (Reference Kim and Muller2007) generalize 2SLS estimation to the two-stage Huber estimation for a linear regression model with endogenous regressors. Sølvsten (Reference Sølvsten2020) proposes an estimator that is robust to outliers in a linear model with many IVs. All the works above deal with linear regression models with independent data.

Next, we provide a brief overview of the robust estimation literature pertaining to the SAR model and related network econometric models. To date, such literature remains limited. Genton (Reference Genton, Dutter, Filzmoser, Gather and Rousseeuw2003) calculates the breakdown point of the MLE for a pure SAR model (i.e., an SAR model without any

![]() $x_{i,n}$

) whose spatial weights matrix is a lower triangular matrix, and the breakdown point of the least median of squares for the following SAR model,

$x_{i,n}$

) whose spatial weights matrix is a lower triangular matrix, and the breakdown point of the least median of squares for the following SAR model,

![]() $Y_{i}=\frac {\rho }{2}\left (Y_{i-1}+Y_{i+1}\right )+\epsilon _{i}$

, where

$Y_{i}=\frac {\rho }{2}\left (Y_{i-1}+Y_{i+1}\right )+\epsilon _{i}$

, where

![]() $\epsilon _{i}$

’s are independently and identically distributed (i.i.d.) normal random variables. Britos and Ojeda (Reference Britos and Ojeda2019) propose a robust estimation procedure for an SAR model in which individuals are located on a two-dimensional integer lattice

$\epsilon _{i}$

’s are independently and identically distributed (i.i.d.) normal random variables. Britos and Ojeda (Reference Britos and Ojeda2019) propose a robust estimation procedure for an SAR model in which individuals are located on a two-dimensional integer lattice

![]() $\mathbb {Z}^{2}$

. They adopt a lower triangular spatial weights matrix which precludes endogeneity. Yildirim and Mert Kantar (Reference Yildirim and Mert Kantar2020) study the robust estimation of a spatial error model by adjusting the score of the log-likelihood function. They focus on computational aspects and simulation studies of the method. Xiao, Xu, and Zhong (Reference Xiao, Xu and Zhong2023) study the Huber estimation of the network autoregressive model. But neither the model in Britos and Ojeda (Reference Britos and Ojeda2019) nor that in Xiao, Xu, and Zhong (Reference Xiao, Xu and Zhong2023) involves an endogenous spatial lag term, distinguishing their models from the SAR model. The following two papers are more related to our work. Su and Yang (Reference Su and Yang2011) propose the IV quantile regression (IVQR) approach, which is robust and less sensitive to outliers. However, we find that the IVQR approach suffers from significant efficiency loss when disturbances are short-tailed distributed. Tho et al. (Reference Xiao, Xu and Zhong2023) study the Huber estimation of the SAR model. They adapt the score of the log-likelihood function, which relies on i.i.d. normal assumption, to develop an estimator that is robust to outliers.

$\mathbb {Z}^{2}$

. They adopt a lower triangular spatial weights matrix which precludes endogeneity. Yildirim and Mert Kantar (Reference Yildirim and Mert Kantar2020) study the robust estimation of a spatial error model by adjusting the score of the log-likelihood function. They focus on computational aspects and simulation studies of the method. Xiao, Xu, and Zhong (Reference Xiao, Xu and Zhong2023) study the Huber estimation of the network autoregressive model. But neither the model in Britos and Ojeda (Reference Britos and Ojeda2019) nor that in Xiao, Xu, and Zhong (Reference Xiao, Xu and Zhong2023) involves an endogenous spatial lag term, distinguishing their models from the SAR model. The following two papers are more related to our work. Su and Yang (Reference Su and Yang2011) propose the IV quantile regression (IVQR) approach, which is robust and less sensitive to outliers. However, we find that the IVQR approach suffers from significant efficiency loss when disturbances are short-tailed distributed. Tho et al. (Reference Xiao, Xu and Zhong2023) study the Huber estimation of the SAR model. They adapt the score of the log-likelihood function, which relies on i.i.d. normal assumption, to develop an estimator that is robust to outliers.

Unlike Tho et al. (Reference Tho, Ding, Hui, Welsh and Zou2023), our work generalizes 2SLS and GMM estimation for the SAR model to ensure robustness against outliers, long-tailed disturbances, and conditional heteroskedasticity, without sacrificing much efficiency under short-tailed disturbances. We integrate the idea of the Huber M-estimation with traditional moment estimation methods for the SAR model (the 2SLS, the best IV [BIV] estimation, and GMM) to propose two novel estimation approaches for the SAR model, i.e., Huber IV (HIV) estimation and Huber GMM (HGMM) estimation.

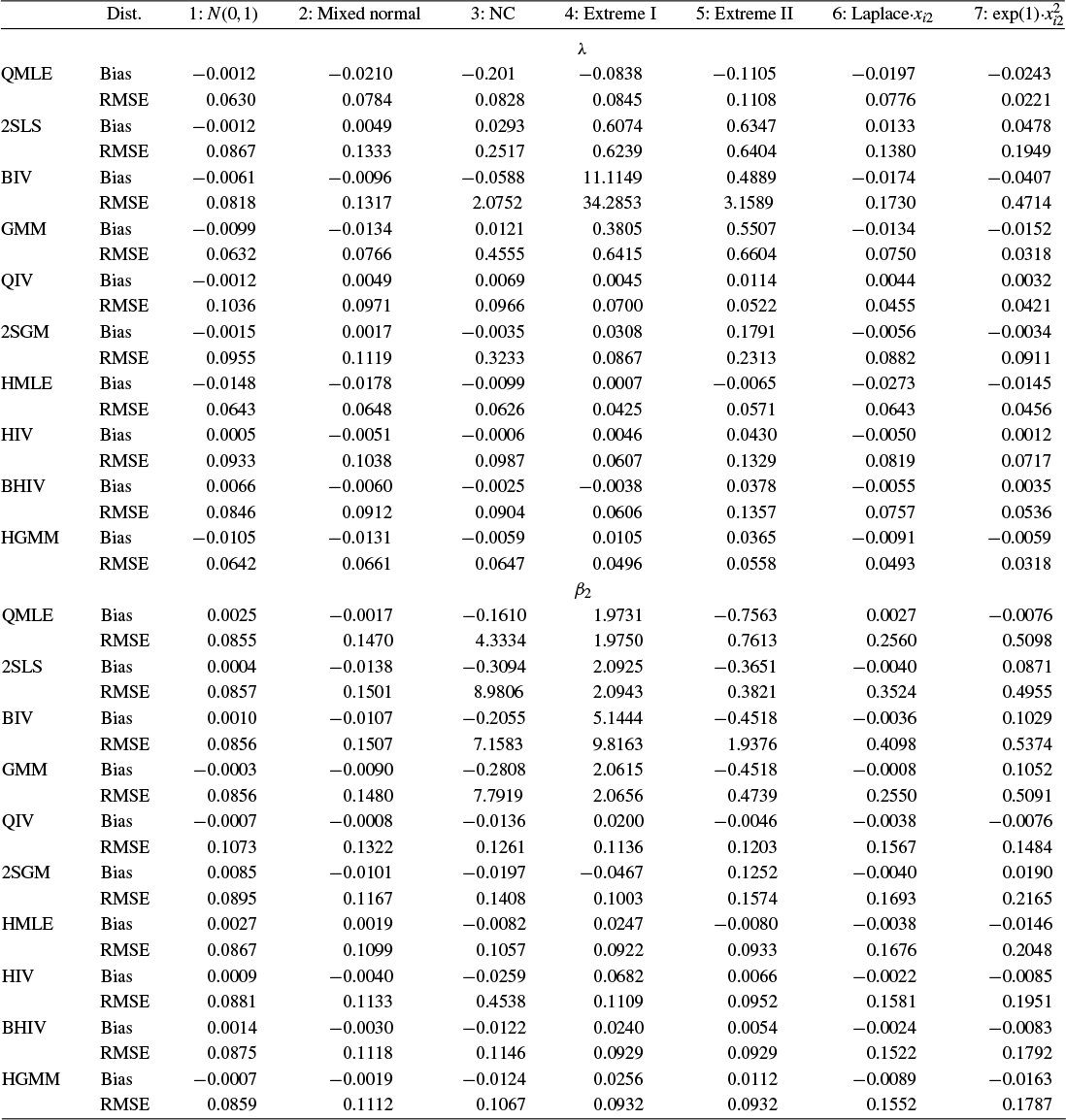

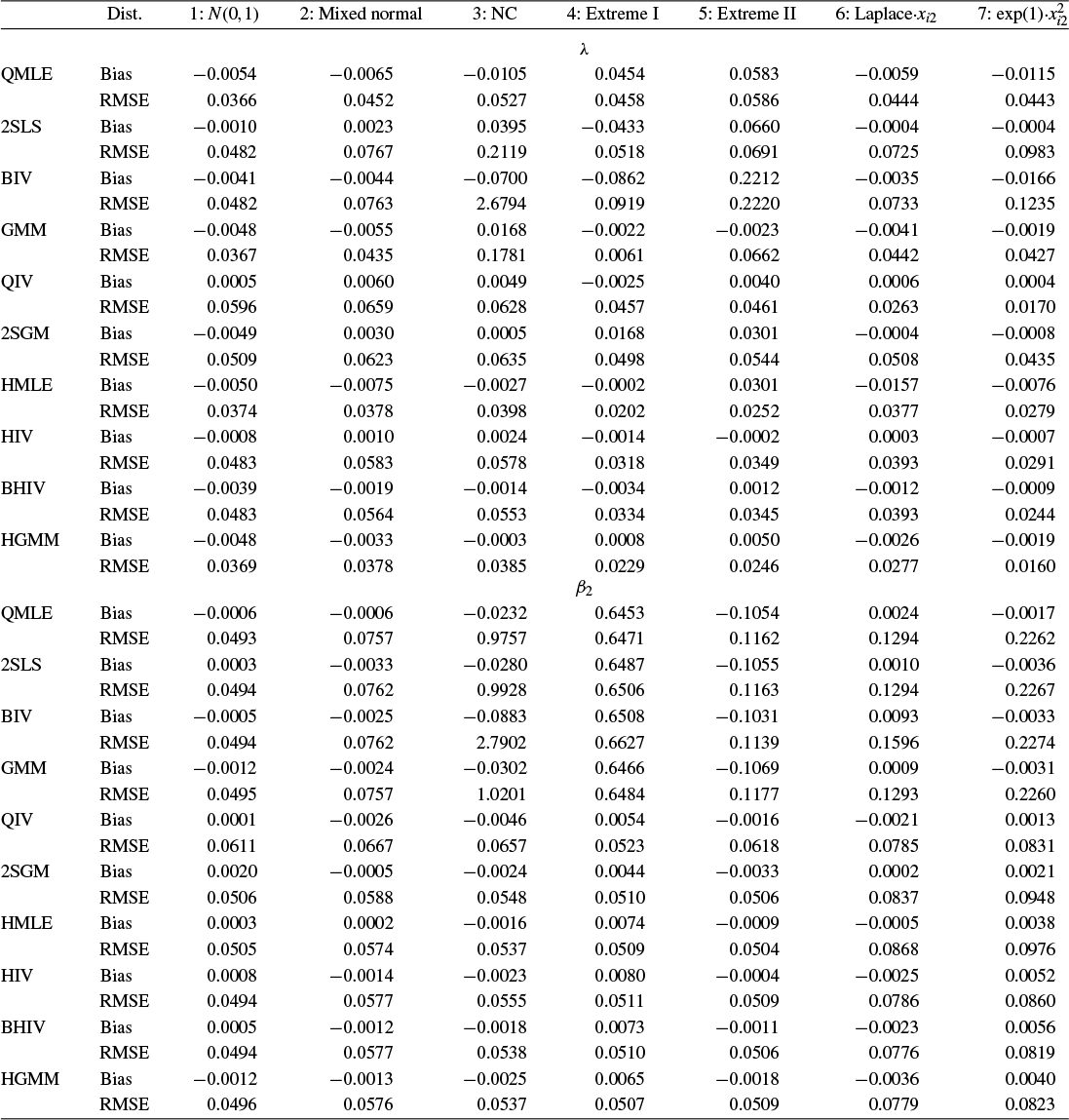

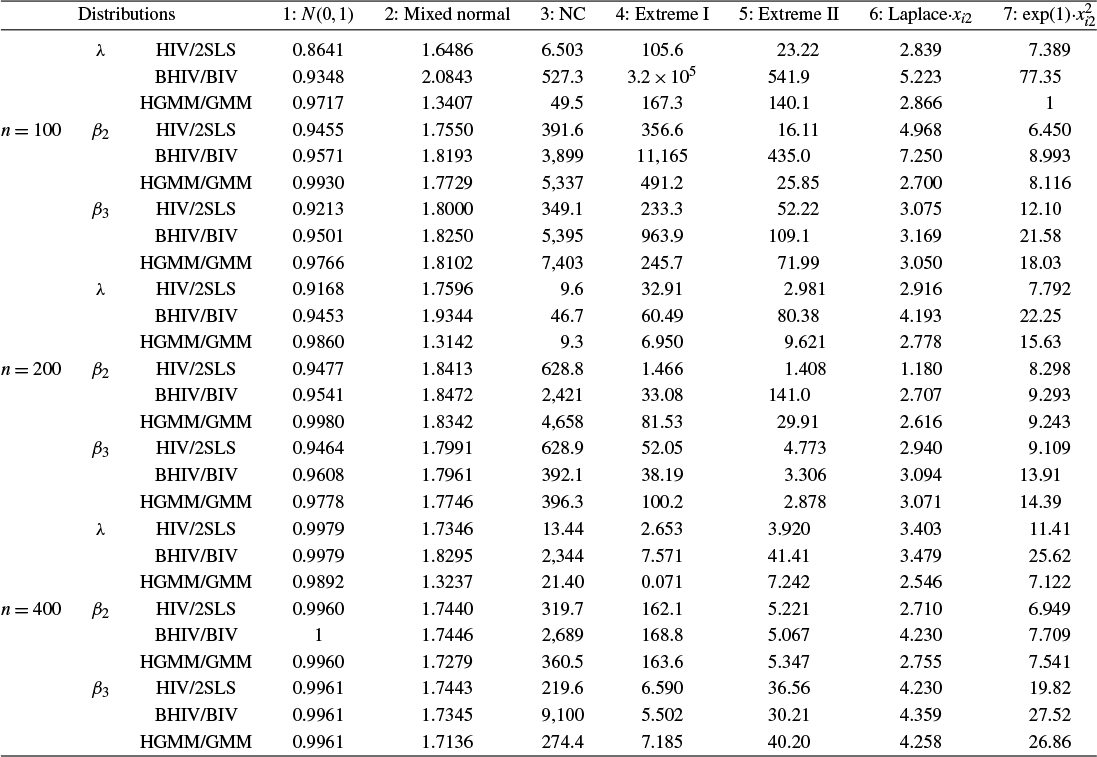

Traditional estimation methods (MLE and GMM) for the SAR model typically require the existence of moments of order higher than 4 for the error terms. The asymptotic normality of our proposed estimators only requires the existence of the first-order moment, without imposing any additional restrictive assumptions. Compared to the HIV estimation, the HGMM estimation is more recommended in empirical studies, as it is more efficient. Compared to GMM (or QML) estimation, the HGMM estimation is robust to outliers, long-tailed disturbances (and conditional heteroskedasticity). Even if the error terms are i.i.d. normally distributed, the root mean square error (RMSE) of the HGMM estimator is only about 0.2%–1.5% greater than that of the MLE, as demonstrated by simulation studies. In sum, when the error terms are i.i.d. and follow a short-tailed distribution, QML, GMM, and HGMM estimation all work satisfactorily. However, when outliers are present in the data or when it is uncertain whether the data follow a long-tailed distribution or not, the HGMM estimation method should be the preferred choice over traditional estimation methods. Practitioners can access the HGMM estimation via the accompanying package “HGMM_SAR” in their empirical studies.Footnote 2

The rest of this article is organized as follows. In Section 2, we propose the HIV estimation and the HGMM estimation for the SAR model. In Section 3, we study the consistency and asymptotic distributions of these estimators and discuss their finite sample breakdown points and influence functions. In Section 4, we implement Monte Carlo simulations to assess the finite sample properties of our proposed estimators in comparison with traditional counterparts and some other robust estimators. Section 5 applies the HGMM estimation to examine the impact of the urban heat island effect on housing prices in Beijing. Section 6 concludes this article. Additional extensions of our methods, all proofs, and ancillary tables for simulation and empirical results are collected in appendixes.

Notations:

![]() $\mathbb {N}\equiv \{1,2,3,\ldots \}$

denotes the set of positive integers. Let

$\mathbb {N}\equiv \{1,2,3,\ldots \}$

denotes the set of positive integers. Let

![]() $\mathbb {R}^{n}$

denote the n-dimensional euclidean space. For any

$\mathbb {R}^{n}$

denote the n-dimensional euclidean space. For any

![]() $m\times n$

matrix

$m\times n$

matrix

![]() $A=(a_{ij})$

,

$A=(a_{ij})$

,

![]() $A_{i\cdot }$

denotes its i-th row,

$A_{i\cdot }$

denotes its i-th row,

![]() $\Vert A\Vert _{1}=\max _{j=1,\ldots ,n}\sum _{i=1}^{m}|a_{ij}|$

,

$\Vert A\Vert _{1}=\max _{j=1,\ldots ,n}\sum _{i=1}^{m}|a_{ij}|$

,

![]() $\Vert A\Vert _{\infty }=\max _{1\leq i\leq m}\sum _{j=1}^{n}|a_{ij}|$

, and its Frobenius norm

$\Vert A\Vert _{\infty }=\max _{1\leq i\leq m}\sum _{j=1}^{n}|a_{ij}|$

, and its Frobenius norm

![]() $||A||\equiv (\sum _{i=1}^{m}\sum _{j=1}^{n}a_{ij}^{2})^{1/2}$

. For any square matrix

$||A||\equiv (\sum _{i=1}^{m}\sum _{j=1}^{n}a_{ij}^{2})^{1/2}$

. For any square matrix

![]() $A=(a_{ij})$

,

$A=(a_{ij})$

,

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {tr}}(A)$

denotes its trace. For any random vector x and constant

$\operatorname {\mathrm {tr}}(A)$

denotes its trace. For any random vector x and constant

![]() $p\geq 1$

, the

$p\geq 1$

, the

![]() $L_{p}$

-norm of X is defined to be

$L_{p}$

-norm of X is defined to be

![]() $||x||_{L^{p}}\equiv \left (\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}||x||^{p}\right )^{1/p}$

. For any matrix A,

$||x||_{L^{p}}\equiv \left (\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}||x||^{p}\right )^{1/p}$

. For any matrix A,

![]() $\min \operatorname {\mathrm {sv}}(A)$

and

$\min \operatorname {\mathrm {sv}}(A)$

and

![]() $\max \operatorname {\mathrm {sv}}(A)$

denote its minimum and maximum singular values, respectively. For any set A,

$\max \operatorname {\mathrm {sv}}(A)$

denote its minimum and maximum singular values, respectively. For any set A,

![]() $|A|$

denotes its cardinality, i.e., the number of elements in A. Let

$|A|$

denotes its cardinality, i.e., the number of elements in A. Let

![]() $\overset {p}{\rightarrow }$

and

$\overset {p}{\rightarrow }$

and

![]() $\overset {d}{\rightarrow }$

denote convergence in probability and distribution, respectively.

$\overset {d}{\rightarrow }$

denote convergence in probability and distribution, respectively.

![]() $f(x)\lesssim g(x)$

means that

$f(x)\lesssim g(x)$

means that

![]() $f(x)\leq Cg(x)$

for all x for some constant C. For any scalar-valued function

$f(x)\leq Cg(x)$

for all x for some constant C. For any scalar-valued function

![]() $f:X(\subset \mathbb {R})\to \mathbb {R}$

and any vector

$f:X(\subset \mathbb {R})\to \mathbb {R}$

and any vector

![]() $a=(a_{1},\ldots ,a_{n})'$

with each

$a=(a_{1},\ldots ,a_{n})'$

with each

![]() $a_{i}\in X$

, we extend the definition of f to

$a_{i}\in X$

, we extend the definition of f to

![]() $f(a)=(f(a_{1}),\ldots ,f(a_{n}))'$

. A random field about

$f(a)=(f(a_{1}),\ldots ,f(a_{n}))'$

. A random field about

![]() $x_{i,n}$

is denoted by

$x_{i,n}$

is denoted by

![]() $\{x_{i,n}:i\in D_{n},n\in \mathbb {N}\}$

, where

$\{x_{i,n}:i\in D_{n},n\in \mathbb {N}\}$

, where

![]() $D_{n}$

denotes the set of individuals,Footnote

3

and sometimes

$D_{n}$

denotes the set of individuals,Footnote

3

and sometimes

![]() $\{x_{i,n}:i\in D_{n}\}$

or

$\{x_{i,n}:i\in D_{n}\}$

or

![]() $\{x_{i,n}\}$

for short.

$\{x_{i,n}\}$

for short.

2 TWO ROBUST ESTIMATORS FOR THE SAR MODEL

In this section, we propose two robust estimators for the SAR model based on Huber’s loss function: the HIV estimator and the HGMM estimator. We leave the discussion of their theoretical properties to Section 3.

2.1 Huber IV Estimator of the SAR Model

Kelejian and Prucha (Reference Kelejian and Prucha1998) propose the 2SLS estimator for the SAR model. Building upon their approach, we integrate Huber’s (Reference Huber1964) robust estimation technique to propose the HIV estimator in this section. The SAR model is formulated as

$$ \begin{align} y_{i,n}=\lambda w_{i\cdot,n}Y_{n}+x_{i,n}'\beta+\epsilon_{i,n}\equiv\lambda\sum_{j=1}^{n}w_{ij,n}y_{j,n}+x_{i,n}'\beta+\epsilon_{i,n}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} y_{i,n}=\lambda w_{i\cdot,n}Y_{n}+x_{i,n}'\beta+\epsilon_{i,n}\equiv\lambda\sum_{j=1}^{n}w_{ij,n}y_{j,n}+x_{i,n}'\beta+\epsilon_{i,n}, \end{align} $$

or in matrix form,

![]() $Y_{n}=\lambda W_{n}Y_{n}+X_{n}\beta +\epsilon _{n}$

, where

$Y_{n}=\lambda W_{n}Y_{n}+X_{n}\beta +\epsilon _{n}$

, where

![]() $Y_{n}\equiv (y_{1,n},\ldots ,y_{n,n})'$

is the column vector of dependent variables,

$Y_{n}\equiv (y_{1,n},\ldots ,y_{n,n})'$

is the column vector of dependent variables,

![]() $W_{n}=(w_{ij,n})$

is an

$W_{n}=(w_{ij,n})$

is an

![]() $n\times n$

non-stochastic spatial weights matrix and

$n\times n$

non-stochastic spatial weights matrix and

![]() $w_{i\cdot ,n}$

is its

$w_{i\cdot ,n}$

is its

![]() $i^{th}$

row,

$i^{th}$

row,

![]() $x_{i,n}=(x_{i1},\ldots ,x_{ip_{x}})'$

is a

$x_{i,n}=(x_{i1},\ldots ,x_{ip_{x}})'$

is a

![]() $p_{x}$

-dimensional column vector of exogenous regressors, including the intercept term

$p_{x}$

-dimensional column vector of exogenous regressors, including the intercept term

![]() $x_{i1}=1$

,

$x_{i1}=1$

,

![]() $X_{n}=(x_{1,n},\ldots ,x_{n,n})'$

, and

$X_{n}=(x_{1,n},\ldots ,x_{n,n})'$

, and

![]() $\epsilon _{n}=(\epsilon _{1,n},\ldots ,\epsilon _{n,n})'$

is the column vector of disturbances. Denote the parameter vector

$\epsilon _{n}=(\epsilon _{1,n},\ldots ,\epsilon _{n,n})'$

is the column vector of disturbances. Denote the parameter vector

![]() $\theta =(\lambda ,\beta ')'$

and the true parameter vector

$\theta =(\lambda ,\beta ')'$

and the true parameter vector

![]() ${\theta _{0}=(\lambda _{0},\beta _{0}')'}$

.

${\theta _{0}=(\lambda _{0},\beta _{0}')'}$

.

Huber (Reference Huber1964) introduces the following loss function:

$$\begin{align*}\rho(t)=\begin{cases} \begin{array}{@{}ccl} \frac{1}{2}t^{2} & & |t|\leq M\\ M|t|-\frac{1}{2}M^{2} & & |t|>M, \end{array} & \end{cases} \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\rho(t)=\begin{cases} \begin{array}{@{}ccl} \frac{1}{2}t^{2} & & |t|\leq M\\ M|t|-\frac{1}{2}M^{2} & & |t|>M, \end{array} & \end{cases} \end{align*}$$

where M is a critical value. When

![]() $M=\infty $

,

$M=\infty $

,

![]() $\rho (\cdot )$

is the squared loss function, while as

$\rho (\cdot )$

is the squared loss function, while as

![]() $M\to 0$

,

$M\to 0$

,

![]() $\rho (\cdot )$

approximates the absolute value loss function. Since

$\rho (\cdot )$

approximates the absolute value loss function. Since

![]() $w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}$

is an endogenous variable, the standard Huber M-estimator based on the loss function

$w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}$

is an endogenous variable, the standard Huber M-estimator based on the loss function

![]() $\rho (\cdot )$

is typically inconsistent. However, the idea of moment estimation based on the derivative of

$\rho (\cdot )$

is typically inconsistent. However, the idea of moment estimation based on the derivative of

![]() $\rho (\cdot )$

can be adapted to the SAR model, provided that suitable IVs are available.

$\rho (\cdot )$

can be adapted to the SAR model, provided that suitable IVs are available.

Notice that

![]() $\rho (t)$

is a continuously differentiable even function, and its derivative is

$\rho (t)$

is a continuously differentiable even function, and its derivative is

$$ \begin{align} \psi(t)=\frac{d\rho(t)}{dt}=\begin{cases} \begin{array}{@{}ccl} M & & t>M\\ t & & |t|\leq M\\ -M & & t<-M. \end{array} & \end{cases} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \psi(t)=\frac{d\rho(t)}{dt}=\begin{cases} \begin{array}{@{}ccl} M & & t>M\\ t & & |t|\leq M\\ -M & & t<-M. \end{array} & \end{cases} \end{align} $$

Suppose that

which is a standard assumption in the Huber estimation literature, and

![]() $\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s are independent conditional on

$\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s are independent conditional on

![]() $X_{n}$

. When the distribution of

$X_{n}$

. When the distribution of

![]() $\epsilon _{i,n}$

is symmetric about 0 given

$\epsilon _{i,n}$

is symmetric about 0 given

![]() $x_{i,n}$

, Eq. (2.3) holds trivially. When

$x_{i,n}$

, Eq. (2.3) holds trivially. When

![]() $\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s are i.i.d. but not symmetrically distributed conditional on

$\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s are i.i.d. but not symmetrically distributed conditional on

![]() $X_{n}$

, we can also shift the intercept such that Eq. (2.3) is satisfied,Footnote

4

and that is why an intercept term must be included. Notice that Eq. (2.3) allows conditional heteroskedasticity, so

$X_{n}$

, we can also shift the intercept such that Eq. (2.3) is satisfied,Footnote

4

and that is why an intercept term must be included. Notice that Eq. (2.3) allows conditional heteroskedasticity, so

![]() $\epsilon _{i,n}$

and

$\epsilon _{i,n}$

and

![]() $x_{i,n}$

might not be independent.

$x_{i,n}$

might not be independent.

Since

![]() $W_{n}$

is nonstochastic, Eq. (2.3) implies

$W_{n}$

is nonstochastic, Eq. (2.3) implies

Hence,

![]() $x_{i,n}$

and

$x_{i,n}$

and

![]() $w_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}$

can be regarded as IVs.Footnote

5

We can also add the second-order spatial effects

$w_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}$

can be regarded as IVs.Footnote

5

We can also add the second-order spatial effects

![]() $(w_{i\cdot ,n}W_{n}X_{n})$

into the IV vector

$(w_{i\cdot ,n}W_{n}X_{n})$

into the IV vector

![]() $q_{i,n}$

, or use

$q_{i,n}$

, or use

![]() $G_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}\beta _{0}$

as an IV for the endogenous variable

$G_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}\beta _{0}$

as an IV for the endogenous variable

![]() $w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}$

in the SAR model, where

$w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}$

in the SAR model, where

![]() $G_{n}\equiv W_{n}(I_{n}-\lambda _{0}W_{n})^{-1}$

and

$G_{n}\equiv W_{n}(I_{n}-\lambda _{0}W_{n})^{-1}$

and

![]() $G_{i\cdot ,n}$

is its i-th row.Footnote

6

We can also censor these IVs such that they can satisfy the theory. Let

$G_{i\cdot ,n}$

is its i-th row.Footnote

6

We can also censor these IVs such that they can satisfy the theory. Let

![]() $q_{i,n}\in \mathbb {R}^{p_{q}}$

be the column IV vector in the following and

$q_{i,n}\in \mathbb {R}^{p_{q}}$

be the column IV vector in the following and

![]() ${Q_{n}\equiv (q_{1,n},\ldots ,q_{n,n})'}$

denote the corresponding

${Q_{n}\equiv (q_{1,n},\ldots ,q_{n,n})'}$

denote the corresponding

![]() $n\times p_{q}$

IV matrix, where

$n\times p_{q}$

IV matrix, where

![]() $p_{q}$

must be greater than or equal to

$p_{q}$

must be greater than or equal to

![]() $p_{x}+1$

, the dimension of

$p_{x}+1$

, the dimension of

![]() $\theta $

. Then, we can write the moment conditions as

$\theta $

. Then, we can write the moment conditions as

Based on Eq. (2.4) and the corresponding sample moments, we can derive an estimator for

![]() $\theta $

, which we term the HIV estimator. Denote

$\theta $

, which we term the HIV estimator. Denote

![]() $ {{\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta )\equiv }}y_{i,n}-\lambda w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}-x_{i,n}'\beta $

,

$ {{\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta )\equiv }}y_{i,n}-\lambda w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}-x_{i,n}'\beta $

,

![]() $\epsilon _{n}(\theta )\equiv (\epsilon _{1,n}(\theta ),\dots ,\epsilon _{n,n}(\theta ))'$

, and

$\epsilon _{n}(\theta )\equiv (\epsilon _{1,n}(\theta ),\dots ,\epsilon _{n,n}(\theta ))'$

, and

![]() $\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))=(\psi (\epsilon _{1,n}(\theta )),\dots ,\psi (\epsilon _{n,n}(\theta )))'$

. The sample moments corresponding to Eq. (2.4) are

$\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))=(\psi (\epsilon _{1,n}(\theta )),\dots ,\psi (\epsilon _{n,n}(\theta )))'$

. The sample moments corresponding to Eq. (2.4) are

![]() $\frac {1}{n}Q_{n}'\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))=\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))q_{i,n}$

. Given a positive-definite GMM weighting matrix

$\frac {1}{n}Q_{n}'\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))=\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))q_{i,n}$

. Given a positive-definite GMM weighting matrix

![]() $\Omega _{n}$

, we can obtain an HIV estimator

$\Omega _{n}$

, we can obtain an HIV estimator

![]() $\hat {\theta }_{n}=\arg \min _{\theta \in \Theta }\hat {T}_{n}(\theta )$

, where

$\hat {\theta }_{n}=\arg \min _{\theta \in \Theta }\hat {T}_{n}(\theta )$

, where

$$ \begin{align} \hat{T}_{n}(\theta)&=\left[\frac{1}{n}Q_{n}'\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))\right]'\Omega_{n}\left[\frac{1}{n}Q_{n}'\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))\right]\nonumber\\&=\left[\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\psi(\epsilon_{i,n}(\theta))q_{i,n}\right]'\Omega_{n}\left[\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\psi(\epsilon_{i,n}(\theta))q_{i,n}\right]. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \hat{T}_{n}(\theta)&=\left[\frac{1}{n}Q_{n}'\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))\right]'\Omega_{n}\left[\frac{1}{n}Q_{n}'\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))\right]\nonumber\\&=\left[\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\psi(\epsilon_{i,n}(\theta))q_{i,n}\right]'\Omega_{n}\left[\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\psi(\epsilon_{i,n}(\theta))q_{i,n}\right]. \end{align} $$

In practice, we can let

![]() $\Omega _{n}\equiv \left (\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}q_{i,n}q_{i,n}'\right )^{-1}$

. In this case, when

$\Omega _{n}\equiv \left (\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}q_{i,n}q_{i,n}'\right )^{-1}$

. In this case, when

![]() $M=\infty $

, the HIV estimator is reduced to the 2SLS estimator based on

$M=\infty $

, the HIV estimator is reduced to the 2SLS estimator based on

![]() $q_{i,n}$

.

$q_{i,n}$

.

If conditional on

![]() $X_{n}$

,

$X_{n}$

,

![]() $\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s are i.i.d., the best HIV (BHIV) for

$\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s are i.i.d., the best HIV (BHIV) for

![]() $w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}$

is

$w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}$

is

![]() $G_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}\beta _{0}$

, which is the same as that proposed in Lee (Reference Lee2003). To implement the BHIV estimation, we need a consistent estimator for

$G_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}\beta _{0}$

, which is the same as that proposed in Lee (Reference Lee2003). To implement the BHIV estimation, we need a consistent estimator for

![]() $\theta _{0}$

and replace

$\theta _{0}$

and replace

![]() $G_{n}$

and

$G_{n}$

and

![]() $\beta _{0}$

by their estimates (see Section B of the Supplementary Material for details).

$\beta _{0}$

by their estimates (see Section B of the Supplementary Material for details).

2.2 Huber GMM Estimator

Building upon the 2SLS in Kelejian and Prucha (Reference Kelejian and Prucha1998), the quadratic moment conditions for a pure SAR model in Kelejian and Prucha (Reference Kelejian and Prucha1999), and the BIV estimation in Lee (Reference Lee2003) for the SAR model, Lee (Reference Lee2007) proposes a GMM estimator for an SAR model that employs both linear and quadratic moments. This GMM estimator surpasses the 2SLS estimator in efficiency and can rival the MLE when the disturbances are normally distributed and appropriate quadratic moments are chosen. Lin and Lee (Reference Lin and Lee2010) extend Lee (Reference Lee2007) to allow heteroskedasticity.

Like a 2SLS estimator, the HIV estimator proposed in the previous section employs only the first-order moments based on the conditional IV moments motivated by Eq. (2.3). To enhance estimation efficiency, drawing inspiration from Kelejian and Prucha (Reference Kelejian and Prucha1999), Lee (Reference Lee2007), and Lin and Lee (Reference Lin and Lee2010), we explore “quadratic Huber moments” in this section.

Our discussion proceeds under the same assumptions outlined in Section 2.1, especially Eq. (2.3). Let

![]() $P_{kn}=(P_{ij,kn})$

(

$P_{kn}=(P_{ij,kn})$

(

![]() $k=1,\ldots ,m$

) be n-dimensional nonstochastic square matrices with zero diagonals, i.e.,

$k=1,\ldots ,m$

) be n-dimensional nonstochastic square matrices with zero diagonals, i.e.,

![]() $P_{ii,kn}=0$

for all

$P_{ii,kn}=0$

for all

![]() $i=1,\ldots ,n$

. Then, it follows from Eq. (2.3) and the independence of

$i=1,\ldots ,n$

. Then, it follows from Eq. (2.3) and the independence of

![]() $\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s that

$\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s that

$$\begin{align*}\operatorname{\mathrm{E}}[\psi(\epsilon_{n})'P_{kn}\psi(\epsilon_{n})]&=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\sum_{j\neq i}P_{ij,kn}\operatorname{\mathrm{E}}[\psi(\epsilon_{i,n})\psi(\epsilon_{j,n})]\nonumber\\&=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\sum_{j\neq i}P_{ij,kn}\operatorname{\mathrm{E}}[\psi(\epsilon_{i,n})]\operatorname{\mathrm{E}}\psi(\epsilon_{j,n})]=0. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\operatorname{\mathrm{E}}[\psi(\epsilon_{n})'P_{kn}\psi(\epsilon_{n})]&=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\sum_{j\neq i}P_{ij,kn}\operatorname{\mathrm{E}}[\psi(\epsilon_{i,n})\psi(\epsilon_{j,n})]\nonumber\\&=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\sum_{j\neq i}P_{ij,kn}\operatorname{\mathrm{E}}[\psi(\epsilon_{i,n})]\operatorname{\mathrm{E}}\psi(\epsilon_{j,n})]=0. \end{align*}$$

Consequently, we can construct m sample quadratic Huber moments:

![]() $\frac {1}{n}\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))' P_{kn}\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))$

. As in Section 2.1,

$\frac {1}{n}\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))' P_{kn}\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))$

. As in Section 2.1,

![]() $q_{i,n}$

denotes a column IV vector and

$q_{i,n}$

denotes a column IV vector and

![]() $Q_{n}\equiv (q_{1,n},\ldots ,q_{n,n})'$

. We construct a sample moment vector as in Lee (Reference Lee2007) and Lin and Lee (Reference Lin and Lee2010):

$Q_{n}\equiv (q_{1,n},\ldots ,q_{n,n})'$

. We construct a sample moment vector as in Lee (Reference Lee2007) and Lin and Lee (Reference Lin and Lee2010):

$$ \begin{align} g_{n}(\theta)=\frac{1}{n}\left(\begin{array}{@{}c} \psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))'P_{1n}\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))\\ \vdots\\ \psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))'P_{mn}\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))\\ Q_{n}'\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta)) \end{array}\right). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} g_{n}(\theta)=\frac{1}{n}\left(\begin{array}{@{}c} \psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))'P_{1n}\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))\\ \vdots\\ \psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))'P_{mn}\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))\\ Q_{n}'\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta)) \end{array}\right). \end{align} $$

Given a GMM weighting matrix

![]() $\Omega _{n}$

, we obtain an HGMM estimator

$\Omega _{n}$

, we obtain an HGMM estimator

2.3 Selection of the Critical Value M

The Huber loss function contains a critical value M. In Section 3, we show that the two proposed estimators are consistent and asymptotically normal for any fixed constant M. Nonetheless, in finite samples, it might be beneficial to employ a data-driven approach to select a suitable M that balances robustness and efficiency. Following Bickel (Reference Bickel1975), we propose to use

where c is a positive constant and

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {median}}\left (| { {\epsilon }}-\operatorname {\mathrm {median}}({{\epsilon }})|\right )/0.6745$

serves as a robust estimator for the standard deviation. The factor

$\operatorname {\mathrm {median}}\left (| { {\epsilon }}-\operatorname {\mathrm {median}}({{\epsilon }})|\right )/0.6745$

serves as a robust estimator for the standard deviation. The factor

![]() $0.6745$

corresponds to the 75% quantile of the standard normal distribution.

$0.6745$

corresponds to the 75% quantile of the standard normal distribution.

Huber (Reference Huber1964) and Maronna et al. (Reference Maronna, Martin, Yohai and Salibián-Barrera2019) demonstrate through simulation studies that the performance of Huber M estimators is relatively insensitive to the choice of c, when it lies between 1 and 1.5. Any value within the interval

![]() $[1,1.5]$

can yield satisfactory results. Both MATLAB and R default to a critical value of 1.345, which corresponds to a 95% relative asymptotic efficiency for location estimators under normality.Footnote

7

We also investigate this issue through simulations in Section 4. The conclusion is similar. When c is a constant between 1 and 1.5, our proposed estimators outperform traditional estimators for the SAR model under long-tailed disturbances or extreme outliers, with performances being comparable across this range. Thus, it makes little practical difference whether

$[1,1.5]$

can yield satisfactory results. Both MATLAB and R default to a critical value of 1.345, which corresponds to a 95% relative asymptotic efficiency for location estimators under normality.Footnote

7

We also investigate this issue through simulations in Section 4. The conclusion is similar. When c is a constant between 1 and 1.5, our proposed estimators outperform traditional estimators for the SAR model under long-tailed disturbances or extreme outliers, with performances being comparable across this range. Thus, it makes little practical difference whether

![]() $c=1$

, 1.2, 1.345, or 1.5. Following the practice in MATLAB and R, we determine the critical value M using Eq. (2.7) with

$c=1$

, 1.2, 1.345, or 1.5. Following the practice in MATLAB and R, we determine the critical value M using Eq. (2.7) with

![]() $c=1.345$

in both our simulation studies and empirical applications.

$c=1.345$

in both our simulation studies and empirical applications.

3 THEORETICAL ANALYSIS

In this section, we will establish the large sample properties of the HIV estimator and the HGMM estimator, and discuss their finite sample breakdown points and influence functions.

3.1 Spatial Near-Epoch Dependence

Since Kelejian and Prucha (Reference Kelejian and Prucha2001) establish a central limit theorem (CLT) for linear-quadratic forms in the context of SAR models, the theory of linear-quadratic forms has become a cornerstone in spatial econometrics (see Kelejian and Prucha, Reference Kelejian and Prucha2001; Lee, Reference Lee2004, Reference Lee2007). However, as

![]() $\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))$

does not conform to a linear-quadratic form, the theory of linear-quadratic forms is not applicable to Huber estimators, except when

$\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))$

does not conform to a linear-quadratic form, the theory of linear-quadratic forms is not applicable to Huber estimators, except when

![]() $\theta =\theta _{0}$

. Hence, we require certain weak spatial dependence concepts such that some laws of large numbers (LLN) can be utilized to establish asymptotic properties of our estimators. The theory of the spatial near-epoch dependence (NED) developed in Jenish and Prucha (Reference Jenish and Prucha2012) is prevalent in spatial econometrics and is capable of handling nonlinear models. Thus, using this approach, we establish large sample properties of our estimators via spatial NED theory.

$\theta =\theta _{0}$

. Hence, we require certain weak spatial dependence concepts such that some laws of large numbers (LLN) can be utilized to establish asymptotic properties of our estimators. The theory of the spatial near-epoch dependence (NED) developed in Jenish and Prucha (Reference Jenish and Prucha2012) is prevalent in spatial econometrics and is capable of handling nonlinear models. Thus, using this approach, we establish large sample properties of our estimators via spatial NED theory.

Suppose that there are n individuals located in

![]() $D_{n}\subset \mathbb {R}^{d}$

and

$D_{n}\subset \mathbb {R}^{d}$

and

![]() $|D_{n}|=n$

. As in Jenish and Prucha (Reference Jenish and Prucha2012), the distance between any two points

$|D_{n}|=n$

. As in Jenish and Prucha (Reference Jenish and Prucha2012), the distance between any two points

![]() $x,y\in \mathbb {R}^{d}$

is defined as

$x,y\in \mathbb {R}^{d}$

is defined as

![]() $d_{xy}=\max _{i=1,\ldots ,d}|x_{i}-y_{i}|$

. We index these n individuals as

$d_{xy}=\max _{i=1,\ldots ,d}|x_{i}-y_{i}|$

. We index these n individuals as

![]() $1,2,\ldots ,n$

. We identify their indices and locations in this article.Footnote

8

$1,2,\ldots ,n$

. We identify their indices and locations in this article.Footnote

8

Next, we list the assumptions required to establish some moment conditions and spatial NED properties for

![]() $\{y_{i,n}:i\in D_{n}\}$

and related variables, which will be applied to establish the asymptotic theories in Sections 3.2 and 3.3.

$\{y_{i,n}:i\in D_{n}\}$

and related variables, which will be applied to establish the asymptotic theories in Sections 3.2 and 3.3.

Assumption 1. For any two individuals i and j in

![]() $D_{n}$

, their distance

$D_{n}$

, their distance

![]() $d_{ij}\geq 1$

.

$d_{ij}\geq 1$

.

Assumption 2. (i)

![]() $\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s are independent over i, and

$\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s are independent over i, and

![]() $\sup _{i,k,n}\left (\left \Vert x_{ik,n}\right \Vert _{L^{\gamma }}+\left \Vert \epsilon _{i,n}\right \Vert _{L^{\gamma }}\right )\leq C_{x\epsilon }<\infty $

for some constants

$\sup _{i,k,n}\left (\left \Vert x_{ik,n}\right \Vert _{L^{\gamma }}+\left \Vert \epsilon _{i,n}\right \Vert _{L^{\gamma }}\right )\leq C_{x\epsilon }<\infty $

for some constants

![]() $\gamma \in [1,\infty ]$

.

$\gamma \in [1,\infty ]$

.

(ii)

![]() $\{x_{i,n}\}_{i=1}^{n}$

is an

$\{x_{i,n}\}_{i=1}^{n}$

is an

![]() $\alpha $

-mixing random field with

$\alpha $

-mixing random field with

![]() $\alpha $

-mixing coefficient

$\alpha $

-mixing coefficient

![]() $\alpha (u,v,r)\leq C_{x1}(u+v)^{\tau }\exp (-C_{x2}r^{C_{x3}})$

for some constants

$\alpha (u,v,r)\leq C_{x1}(u+v)^{\tau }\exp (-C_{x2}r^{C_{x3}})$

for some constants

![]() $\tau \geqslant 0$

and

$\tau \geqslant 0$

and

![]() $C_{x1},C_{x2},C_{x3}>0$

.Footnote

9

$C_{x1},C_{x2},C_{x3}>0$

.Footnote

9

(iii)

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}[\psi (\epsilon _{i,n})|X_{n}]=0$

.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}[\psi (\epsilon _{i,n})|X_{n}]=0$

.

Assumption 3.

![]() $\zeta \equiv \lambda _{m}\sup _{n}||W_{n}||_{\infty }<1$

, where

$\zeta \equiv \lambda _{m}\sup _{n}||W_{n}||_{\infty }<1$

, where

![]() $\Lambda =[-\lambda _{m},\lambda _{m}]$

represents the parameter space of

$\Lambda =[-\lambda _{m},\lambda _{m}]$

represents the parameter space of

![]() $\lambda $

on

$\lambda $

on

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

and

$\mathbb {R}$

and

![]() $\lambda _{m}$

is the upper bound of

$\lambda _{m}$

is the upper bound of

![]() $\Lambda $

.

$\Lambda $

.

Assumption 4. In addition to

![]() $w_{ii,n}=0$

for all i and n, all the weights

$w_{ii,n}=0$

for all i and n, all the weights

![]() $w_{ij,n}$

’s in the non-stochastic and nonzero

$w_{ij,n}$

’s in the non-stochastic and nonzero

![]() $n\times n$

matrix

$n\times n$

matrix

![]() $W_{n}$

satisfy at least one of the following two conditions:

$W_{n}$

satisfy at least one of the following two conditions:

(i) When

![]() $d_{ij}>\bar {d_{0}}$

, where

$d_{ij}>\bar {d_{0}}$

, where

![]() $\bar {d_{0}}>1$

is a constant,

$\bar {d_{0}}>1$

is a constant,

![]() $w_{ij,n}=0$

.

$w_{ij,n}=0$

.

(ii) There exists an

![]() $\alpha>2.5d$

and a constant

$\alpha>2.5d$

and a constant

![]() $C_{0}$

such that

$C_{0}$

such that

![]() $|w_{ij,n}|\leq C_{0}/d_{ij}^{\alpha }$

.

$|w_{ij,n}|\leq C_{0}/d_{ij}^{\alpha }$

.

Under Assumption 1, we consider the scenario of increasing domain asymptotics. This setting is widely presumed in spatial econometrics (Qu and Lee, Reference Qu and Lee2015; Xu and Lee, Reference Xu and Lee2015a, Reference Xu and Lee2015b, Reference Xu and Lee2018; Liu and Lee, Reference Liu and Lee2019), as it is the foundation of the spatial mixing and NED theory (Jenish and Prucha, Reference Jenish and Prucha2009, Reference Jenish and Prucha2012). This setting is particularly intuitive when individuals are situated in geographical locations like countries and cities. Nonetheless, social and economic characteristics can also be employed to define coordinates, thereby constructing distances between entities. Although Assumption 1 is popular in spatial econometrics, it rules out the case of infilled asymptotics, i.e., within a bounded space, the number of individuals tends to infinity. Infill asymptotics is popular in time series, especially functional time series (see, e.g., Phillips and Jiang, Reference Phillips and Jiang2025, among many other papers). In spatial statistics, it is also widely studied, e.g., the estimation of a Gaussian random field (see Cressie, Reference Cressie1993 and Gelfand et al., Reference Gelfand, Diggle, Guttorp and Fuentes2010 for details). Under infilled asymptotics, the spatial correlations of many observations might be strong and will not tend to zero. In this case, traditional estimation methods for the SAR model are generally inconsistent.Footnote 10

Assumption 2(i) imposes some moment conditions on the exogenous variable

![]() $x_{i,n}$

and the error term

$x_{i,n}$

and the error term

![]() $\epsilon _{i,n}$

. Specifically, we require only the

$\epsilon _{i,n}$

. Specifically, we require only the

![]() $\gamma $

-th-order moment for

$\gamma $

-th-order moment for

![]() $x_{i,n}$

and

$x_{i,n}$

and

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}|\epsilon _{i,n}|^{\gamma }$

for some

$\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}|\epsilon _{i,n}|^{\gamma }$

for some

![]() $\gamma \geq 1$

. For the QMLE and the GMM estimator, when exogenous variables are uniformly bounded, Lee (Reference Lee2004, Reference Lee2007) requires disturbances to have a finite moment of order higher than 4, i.e.,

$\gamma \geq 1$

. For the QMLE and the GMM estimator, when exogenous variables are uniformly bounded, Lee (Reference Lee2004, Reference Lee2007) requires disturbances to have a finite moment of order higher than 4, i.e.,

![]() $\gamma>4$

in our notation. Assumption 2(ii) allows

$\gamma>4$

in our notation. Assumption 2(ii) allows

![]() $x_{i,n}$

to be spatially correlated. Assumption 2(iii) has been discussed below Eq. (2.3).

$x_{i,n}$

to be spatially correlated. Assumption 2(iii) has been discussed below Eq. (2.3).

Assumption 3 guarantees that the von Neumann series expansion for

![]() ${(I_{n}-\lambda W_{n})^{-1}}$

exists. This assumption is one of the critical assumptions leading to the NED of

${(I_{n}-\lambda W_{n})^{-1}}$

exists. This assumption is one of the critical assumptions leading to the NED of

![]() $\{y_{i,n}\}$

and

$\{y_{i,n}\}$

and

![]() $\{w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}\}$

. It is also widely used in the spatial econometrics literature (see, e.g., the conditions in Lemma 2 in Kelejian and Prucha, Reference Kelejian and Prucha2010).

$\{w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}\}$

. It is also widely used in the spatial econometrics literature (see, e.g., the conditions in Lemma 2 in Kelejian and Prucha, Reference Kelejian and Prucha2010).

Assumption 4 allows two setups for the spatial weights matrix

![]() $W_{n}$

. Under Assumption 4(i), two individuals have direct interactions only if they are within a fixed finite distance. Under Assumption 4(ii), two individuals are allowed to have direct interactions even if they are far away from each other, but the strength of their interactions should decrease as distance increases. Assumptions 1 and 4 imply that

$W_{n}$

. Under Assumption 4(i), two individuals have direct interactions only if they are within a fixed finite distance. Under Assumption 4(ii), two individuals are allowed to have direct interactions even if they are far away from each other, but the strength of their interactions should decrease as distance increases. Assumptions 1 and 4 imply that

![]() $\sup _{n}||W_{n}||_{\infty }<\infty $

and

$\sup _{n}||W_{n}||_{\infty }<\infty $

and

![]() $\sup _{n}||W_{n}||_{1}<\infty $

. With Assumption 3, they further imply that

$\sup _{n}||W_{n}||_{1}<\infty $

. With Assumption 3, they further imply that

![]() $\sup _{n}||(I_{n}-\lambda W_{n})^{-1}||_{\infty }<\infty $

. The uniform boundedness of the norms of

$\sup _{n}||(I_{n}-\lambda W_{n})^{-1}||_{\infty }<\infty $

. The uniform boundedness of the norms of

![]() $W_{n}$

and

$W_{n}$

and

![]() $(I_{n}-\lambda W_{n})^{-1}$

is prevalent in the literature of spatial econometrics (see, e.g., Assumption 3 in Kelejian and Prucha, Reference Kelejian and Prucha2010 and Assumption 5 in Lee, Reference Lee2004).

$(I_{n}-\lambda W_{n})^{-1}$

is prevalent in the literature of spatial econometrics (see, e.g., Assumption 3 in Kelejian and Prucha, Reference Kelejian and Prucha2010 and Assumption 5 in Lee, Reference Lee2004).

Assumptions 1–4 imply that

![]() $\{y_{i,n}\}$

and

$\{y_{i,n}\}$

and

![]() $\{w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}\}$

are

$\{w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}\}$

are

![]() $L_{\gamma }$

-NED on

$L_{\gamma }$

-NED on

![]() $\{x_{i,n},\epsilon _{i,n}:i\in D_{n}\}$

(Lemma A.8). We summarize the moment and

$\{x_{i,n},\epsilon _{i,n}:i\in D_{n}\}$

(Lemma A.8). We summarize the moment and

![]() $L_{\gamma }$

-NED properties of the regressor

$L_{\gamma }$

-NED properties of the regressor

![]() $z_{i,n}\equiv (w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n},x_{i,n}')'$

,

$z_{i,n}\equiv (w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n},x_{i,n}')'$

,

![]() ${{\psi }({\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))}}$

, and common choices for IVs in Lemma A.8 in Appendix A.

${{\psi }({\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))}}$

, and common choices for IVs in Lemma A.8 in Appendix A.

3.2 Large Sample Properties of the Huber IV Estimator

In this section, we establish the large sample properties of the HIV estimator defined in Eq. (2.5).

Assumption 5. The parameter space

![]() $\Theta $

is convex and compact.

$\Theta $

is convex and compact.

Assumption 6. The IV vector

![]() $q_{i,n}\in \mathbb {R}^{p_{q}}$

(

$q_{i,n}\in \mathbb {R}^{p_{q}}$

(

![]() $p_{q}\geq p_{x}+1$

) is constructed from

$p_{q}\geq p_{x}+1$

) is constructed from

![]() $X_{n}$

and

$X_{n}$

and

![]() $W_{n}$

, and

$W_{n}$

, and

![]() $\sup _{i,n}||q_{i,n}||<\infty $

.

$\sup _{i,n}||q_{i,n}||<\infty $

.

Assumption 7.

![]() $\Omega _{n}\xrightarrow {p}\Omega $

for some positive-definite matrix

$\Omega _{n}\xrightarrow {p}\Omega $

for some positive-definite matrix

![]() $\Omega $

.

$\Omega $

.

Assumption 8.

![]() $\liminf _{n\to \infty }\left \Vert \frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}\left [\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))q_{i,n}\right ]\right \Vert>0$

for any

$\liminf _{n\to \infty }\left \Vert \frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}\left [\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))q_{i,n}\right ]\right \Vert>0$

for any

![]() $\theta \neq \theta _{0}$

.

$\theta \neq \theta _{0}$

.

In this article, we can use

![]() $w_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}$

,

$w_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}$

,

![]() $w_{i\cdot ,n}W_{n}X_{n}$

, or

$w_{i\cdot ,n}W_{n}X_{n}$

, or

![]() $G_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}\beta _{0}$

as the IV for

$G_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}\beta _{0}$

as the IV for

![]() $w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}$

. When

$w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}$

. When

![]() $x_{i,n}$

’s are uniformly bounded, Assumption 6 holds for

$x_{i,n}$

’s are uniformly bounded, Assumption 6 holds for

![]() $x_{i,n}$

,

$x_{i,n}$

,

![]() $w_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}$

,

$w_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}$

,

![]() $w_{i\cdot ,n}W_{n}X_{n}$

, and

$w_{i\cdot ,n}W_{n}X_{n}$

, and

![]() $G_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}\beta _{0}$

; if

$G_{i\cdot ,n}X_{n}\beta _{0}$

; if

![]() $x_{i,n}$

’s are unbounded, we may censor them such that

$x_{i,n}$

’s are unbounded, we may censor them such that

![]() $q_{i,n}$

is uniformly bounded. We assume

$q_{i,n}$

is uniformly bounded. We assume

![]() $\{q_{i,n}:i\in D_{n}\}$

to be uniformly bounded to simplify the proof.Footnote

11

Alternatively, a more involved proof would permit unbounded

$\{q_{i,n}:i\in D_{n}\}$

to be uniformly bounded to simplify the proof.Footnote

11

Alternatively, a more involved proof would permit unbounded

![]() $q_{i,n}$

.

$q_{i,n}$

.

Assumption 7 is the standard requirement for a GMM weighting matrix.

Assumption 8 is crucial for ensuring the identifiable uniqueness of

![]() $\theta _{0}$

. It implies that

$\theta _{0}$

. It implies that

![]() $\theta _{0}$

is the unique solution to

$\theta _{0}$

is the unique solution to

![]() $\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}\left [\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))q_{i,n}\right ]=0$

when n is large enough. However, Assumption 8 is slightly stronger than the condition that

$\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}\left [\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))q_{i,n}\right ]=0$

when n is large enough. However, Assumption 8 is slightly stronger than the condition that

![]() $\theta _{0}$

is the unique solution to

$\theta _{0}$

is the unique solution to

![]() $\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}\left [\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))q_{i,n}\right ]=0$

. Assumption 8 excludes the possibility that

$\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}\left [\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))q_{i,n}\right ]=0$

. Assumption 8 excludes the possibility that

![]() $0<\left \Vert \frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}\left [\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))q_{i,n}\right ]\right \Vert \to 0$

as

$0<\left \Vert \frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}\left [\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))q_{i,n}\right ]\right \Vert \to 0$

as

![]() $n\to \infty $

.

$n\to \infty $

.

Under the above assumptions, the HIV estimator is consistent, as stated in Theorem 1.

Remark. Tho et al. (Reference Tho, Ding, Hui, Welsh and Zou2023) have shown that their estimator is Fisher-consistent (Theorem 1 in their paper), i.e.,

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}\eta (\theta _{0},y)=0$

, where

$\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}\eta (\theta _{0},y)=0$

, where

![]() $\eta (\theta _{0},y)$

is the modified score function in their notation. Fisher-consistency only cares about the behavior of moment functions at the true parameter

$\eta (\theta _{0},y)$

is the modified score function in their notation. Fisher-consistency only cares about the behavior of moment functions at the true parameter

![]() $\theta _{0}$

and

$\theta _{0}$

and

![]() $\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta _{0}))=\psi (\epsilon _{i,n})$

are i.i.d. over i and n. As a result, the LLN for independent variables is applicable to

$\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta _{0}))=\psi (\epsilon _{i,n})$

are i.i.d. over i and n. As a result, the LLN for independent variables is applicable to

![]() $\psi (\epsilon _{i,n})x_{i,n}$

and the LLN for linear-quadratic forms is applicable to

$\psi (\epsilon _{i,n})x_{i,n}$

and the LLN for linear-quadratic forms is applicable to

![]() $\psi (\epsilon _{i,n})w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}$

.

$\psi (\epsilon _{i,n})w_{i\cdot ,n}Y_{n}$

.

The consistency established in Theorem 1 is different from Fisher-consistency: the former usually requires stronger conditions. The Fisher-consistency is similar to the correct model specification condition for GMM estimators. In addition to the correct model specification condition, we need both the uniform convergence in probability condition and identifiable uniqueness condition for consistency. Consequently, we must also address the behavior of moments evaluated at

![]() $\theta \neq \theta _{0}$

. When

$\theta \neq \theta _{0}$

. When

![]() $\theta \neq \theta _{0}$

,

$\theta \neq \theta _{0}$

,

![]() $\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))q_{i,n}$

is no longer a linear-quadratic form of

$\psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))q_{i,n}$

is no longer a linear-quadratic form of

![]() $\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s and

$\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s and

![]() $x_{i,n}$

’s. As a result, the theory of linear-quadratic forms is not applicable. Hence, we employ the spatial NED theory in our article.

$x_{i,n}$

’s. As a result, the theory of linear-quadratic forms is not applicable. Hence, we employ the spatial NED theory in our article.

Next, we derive the asymptotic distribution of the HIV estimator

![]() $\hat {\theta }$

. Given that the objective function

$\hat {\theta }$

. Given that the objective function

![]() $\hat {T}_{n}(\theta )$

is not differentiable with respect to

$\hat {T}_{n}(\theta )$

is not differentiable with respect to

![]() $\theta $

, the conventional Taylor expansion cannot be employed to derive the asymptotic distribution of

$\theta $

, the conventional Taylor expansion cannot be employed to derive the asymptotic distribution of

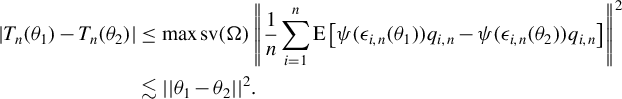

![]() $\hat {\theta }$

. However, we can utilize the empirical process theory for derivation. We generalize Theorem 3.3 in Pakes and Pollard (Reference Pakes and Pollard1989), which studies the asymptotic distributions of GMM estimators under non-differentiable moment conditions, to accommodate heterogeneous data in Proposition B.2. The critical condition in Proposition B.2 is a condition similar to stochastic equicontinuity (SEC), specifically condition (iii) there. Within the empirical process literature, several results exist to validate the SEC condition of an empirical process. However, most of them are tailored to independent or stationary data. Data generated by spatial econometric models are usually both heterogeneous and spatially correlated. Therefore, we need to generalize those results to allow for both heterogeneity and spatial correlation. Pollard (Reference Pollard1985, p. 305) extends the result in Huber (Reference Huber1967) to establish a set of sufficient conditions for SEC in the context of independent data based on a bracketing condition. In this article, we generalize the result in Pollard (Reference Pollard1985) to account for serial or spatial correlation (see Proposition B.1 for details).

$\hat {\theta }$

. However, we can utilize the empirical process theory for derivation. We generalize Theorem 3.3 in Pakes and Pollard (Reference Pakes and Pollard1989), which studies the asymptotic distributions of GMM estimators under non-differentiable moment conditions, to accommodate heterogeneous data in Proposition B.2. The critical condition in Proposition B.2 is a condition similar to stochastic equicontinuity (SEC), specifically condition (iii) there. Within the empirical process literature, several results exist to validate the SEC condition of an empirical process. However, most of them are tailored to independent or stationary data. Data generated by spatial econometric models are usually both heterogeneous and spatially correlated. Therefore, we need to generalize those results to allow for both heterogeneity and spatial correlation. Pollard (Reference Pollard1985, p. 305) extends the result in Huber (Reference Huber1967) to establish a set of sufficient conditions for SEC in the context of independent data based on a bracketing condition. In this article, we generalize the result in Pollard (Reference Pollard1985) to account for serial or spatial correlation (see Proposition B.1 for details).

To establish the asymptotic distribution of

![]() $\hat {\theta }$

, we need some additional regularity conditions.

$\hat {\theta }$

, we need some additional regularity conditions.

![]() $\dot {\psi }(\epsilon )\equiv 1(|\epsilon |\leq M)$

equals the derivative of

$\dot {\psi }(\epsilon )\equiv 1(|\epsilon |\leq M)$

equals the derivative of

![]() $\psi (\epsilon )$

almost everywhere. Define

$\psi (\epsilon )$

almost everywhere. Define

![]() $\Gamma _{n}(\theta )=\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}[\dot {\psi }(y_{i,n}-z_{i,n}'\theta )q_{i,n}z_{i,n}']$

,

$\Gamma _{n}(\theta )=\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\operatorname {\mathrm {E}}[\dot {\psi }(y_{i,n}-z_{i,n}'\theta )q_{i,n}z_{i,n}']$

,

![]() $\Gamma _{n}=\Gamma _{n}(\theta _{0})$

, and

$\Gamma _{n}=\Gamma _{n}(\theta _{0})$

, and

![]() $V_{n}\equiv \operatorname {\mathrm {var}}\left \{ \frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\psi (\epsilon _{i,n})q_{i,n}\right \} $

. By the independence of

$V_{n}\equiv \operatorname {\mathrm {var}}\left \{ \frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\psi (\epsilon _{i,n})q_{i,n}\right \} $

. By the independence of

![]() $\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s and the law of iterated expectation, straightforward calculations yield that

$\epsilon _{i,n}$

’s and the law of iterated expectation, straightforward calculations yield that

$$\begin{align*}V_{n}=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\operatorname{\mathrm{E}}[\psi(\epsilon_{i,n})^{2}q_{i,n}q_{i,n}']. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}V_{n}=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\operatorname{\mathrm{E}}[\psi(\epsilon_{i,n})^{2}q_{i,n}q_{i,n}']. \end{align*}$$

Assumption 9.

![]() $\theta _{0}\in \Theta ^{0}$

, where

$\theta _{0}\in \Theta ^{0}$

, where

![]() $\Theta ^{0}$

denotes the interior of the parameter space

$\Theta ^{0}$

denotes the interior of the parameter space

![]() $\Theta $

.

$\Theta $

.

Assumption 10. (i) The class of functions

![]() $\{\Gamma _{n}(\theta ):\,n\in \mathbb {N}\}$

is equicontinuous at

$\{\Gamma _{n}(\theta ):\,n\in \mathbb {N}\}$

is equicontinuous at

![]() $\theta _{0}$

; (ii) there exists a positive constant

$\theta _{0}$

; (ii) there exists a positive constant

![]() $\delta _{0}$

such that

$\delta _{0}$

such that

$$\begin{align*}\liminf_{n\to\infty}\inf_{\theta_{1},\dots,\theta_{l}\in B(\theta_{0},\delta_{0})}\min\operatorname{\mathrm{sv}}\left(\left[\begin{array}{@{}c} \Gamma_{1n}(\theta_{1})\\ \vdots\\ \Gamma_{ln}(\theta_{l}) \end{array}\right]\right)>0. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\liminf_{n\to\infty}\inf_{\theta_{1},\dots,\theta_{l}\in B(\theta_{0},\delta_{0})}\min\operatorname{\mathrm{sv}}\left(\left[\begin{array}{@{}c} \Gamma_{1n}(\theta_{1})\\ \vdots\\ \Gamma_{ln}(\theta_{l}) \end{array}\right]\right)>0. \end{align*}$$

![]() $\Gamma _{in}(\theta )$

is the

$\Gamma _{in}(\theta )$

is the

![]() $i^{th}$

row of

$i^{th}$

row of

![]() $\Gamma _{n}(\theta )$

; and (iii)

$\Gamma _{n}(\theta )$

; and (iii)

![]() $\lim _{n\to \infty }\Gamma _{n}=\Gamma _{0}$

and

$\lim _{n\to \infty }\Gamma _{n}=\Gamma _{0}$

and

![]() $\Gamma _{0}$

has a full column rank.

$\Gamma _{0}$

has a full column rank.

Assumption 11.

![]() $\lim _{n\to \infty }V_{n}=V_{0}$

for some positive-definite matrix

$\lim _{n\to \infty }V_{n}=V_{0}$

for some positive-definite matrix

![]() $V_{0}$

.

$V_{0}$

.

Assumption 9 is a standard condition for establishing asymptotic distributions. Assumption 10 imposes some conditions on

![]() $\Gamma _{n}(\theta )$

and

$\Gamma _{n}(\theta )$

and

![]() $\Gamma _{n}$

such that condition (ii) of Proposition B.2 holds. We need different

$\Gamma _{n}$

such that condition (ii) of Proposition B.2 holds. We need different

![]() $\theta _{i}$

for different rows because there does not exist a mean-value theorem for vector-valued functions. Under standard conditions,

$\theta _{i}$

for different rows because there does not exist a mean-value theorem for vector-valued functions. Under standard conditions,

![]() $\Gamma _{n}(\theta )$

is continuous at

$\Gamma _{n}(\theta )$

is continuous at

![]() $\theta _{0}$

. The equicontinuity at

$\theta _{0}$

. The equicontinuity at

![]() $\theta _{0}$

for

$\theta _{0}$

for

![]() $\Gamma _{n}(\theta )$

means that as the sample size n increases to infinity,

$\Gamma _{n}(\theta )$

means that as the sample size n increases to infinity,

![]() $\Gamma _{n}(\theta )$

does not change too much around

$\Gamma _{n}(\theta )$

does not change too much around

![]() $\theta _{0}$

. This is a reasonable requirement; otherwise, it would be infeasible to conduct any reliable inference based on finite samples.

$\theta _{0}$

. This is a reasonable requirement; otherwise, it would be infeasible to conduct any reliable inference based on finite samples.

Theorem 2. Under Assumptions 1–11, if the

![]() $\alpha $

in Assumption 4 satisfies

$\alpha $

in Assumption 4 satisfies

![]() $\alpha>\left [\frac {2}{\min (2,\gamma )}+1\right ]d$

,

$\alpha>\left [\frac {2}{\min (2,\gamma )}+1\right ]d$

,

The optimal choice for

![]() $\Omega $

is

$\Omega $

is

![]() $\Omega \propto V_{0}^{-1}$

, and with such an

$\Omega \propto V_{0}^{-1}$

, and with such an

![]() $\Omega $

,

$\Omega $

,

![]() $\sqrt {n}(\hat {\theta }-\theta _{0})\xrightarrow {d}N(0,(\Gamma _{0}'V_{0}^{-1}\Gamma _{0})^{-1})$

.

$\sqrt {n}(\hat {\theta }-\theta _{0})\xrightarrow {d}N(0,(\Gamma _{0}'V_{0}^{-1}\Gamma _{0})^{-1})$

.

A standard two-step GMM procedure can be applied to obtain an HIV estimator based on the optimal GMM weighting matrix, where

![]() $\Omega _{n}\equiv \left [\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\psi (\hat {\epsilon }_{i,n})^{2} q_{i,n}q_{i,n}'\right ]^{-1}$

for the optimal GMM estimation, where

$\Omega _{n}\equiv \left [\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\psi (\hat {\epsilon }_{i,n})^{2} q_{i,n}q_{i,n}'\right ]^{-1}$

for the optimal GMM estimation, where

![]() $\hat {\epsilon }_{i,n}\equiv y_{i,n}-z_{i,n}'\tilde {\theta }$

and

$\hat {\epsilon }_{i,n}\equiv y_{i,n}-z_{i,n}'\tilde {\theta }$

and

![]() $\tilde {\theta }$

is an initial consistent estimator. We can estimate

$\tilde {\theta }$

is an initial consistent estimator. We can estimate

![]() $\Gamma _{0}$

and

$\Gamma _{0}$

and

![]() $V_{0}$

by their sample means

$V_{0}$

by their sample means

![]() $\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\dot {\psi }(\hat {\epsilon }_{i,n})q_{i,n}z_{i,n}'$

and

$\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\dot {\psi }(\hat {\epsilon }_{i,n})q_{i,n}z_{i,n}'$

and

![]() $\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\psi (\hat {\epsilon }_{i,n})^{2}q_{i,n}q_{i,n}'$

, respectively (see Theorem 5 for their consistency).

$\frac {1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n}\psi (\hat {\epsilon }_{i,n})^{2}q_{i,n}q_{i,n}'$

, respectively (see Theorem 5 for their consistency).

3.3 Large Sample Properties of the Huber GMM Estimator

For the HGMM estimator, we require the linear Huber moments to satisfy the conditions for the HIV estimators. In addition, some conditions for the quadratic Huber moments are also needed. We use

![]() $W_{n}$

,

$W_{n}$

,

![]() $W_{n}^{2}-\operatorname {\mathrm {diag}}(W_{n}^{2})$

,

$W_{n}^{2}-\operatorname {\mathrm {diag}}(W_{n}^{2})$

,

![]() $S_{n}^{-1}-\operatorname {\mathrm {diag}}(S_{n}^{-1})$

, or

$S_{n}^{-1}-\operatorname {\mathrm {diag}}(S_{n}^{-1})$

, or

![]() $G_{n}-\operatorname {\mathrm {diag}}(G_{n})$

as

$G_{n}-\operatorname {\mathrm {diag}}(G_{n})$

as

![]() $P_{kn}$

in this article. Since

$P_{kn}$

in this article. Since

$$ \begin{align} \psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))'P_{kn}\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\psi(\epsilon_{i,n}(\theta))\left[P_{i\cdot,kn}\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))\right], \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))'P_{kn}\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\psi(\epsilon_{i,n}(\theta))\left[P_{i\cdot,kn}\psi(\epsilon_{n}(\theta))\right], \end{align} $$

if

![]() $\left \{ P_{i\cdot ,kn}\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))\right \} _{i\in D_{n}}$

is uniformly bounded and uniformly

$\left \{ P_{i\cdot ,kn}\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))\right \} _{i\in D_{n}}$

is uniformly bounded and uniformly

![]() $L_{2}$

-NED on

$L_{2}$

-NED on

![]() $\{x_{i,n}\,\epsilon _{i,n}:i\in D_{n}\}$

, by Lemma A.5, the product term

$\{x_{i,n}\,\epsilon _{i,n}:i\in D_{n}\}$

, by Lemma A.5, the product term

![]() $\left \{ \psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))\left [P_{i\cdot ,kn}\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))\right ]\right \} _{i\in D_{n}}$

is also uniformly bounded and uniformly

$\left \{ \psi (\epsilon _{i,n}(\theta ))\left [P_{i\cdot ,kn}\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))\right ]\right \} _{i\in D_{n}}$

is also uniformly bounded and uniformly

![]() $L_{2}$

-NED. Then, we can investigate the limiting properties of the quadratic Huber moments using the NED theory. We show that

$L_{2}$

-NED. Then, we can investigate the limiting properties of the quadratic Huber moments using the NED theory. We show that

![]() $\left \{ P_{i\cdot ,kn}\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))\right \} _{i\in D_{n}}$

is uniformly

$\left \{ P_{i\cdot ,kn}\psi (\epsilon _{n}(\theta ))\right \} _{i\in D_{n}}$

is uniformly

![]() $L_{2}$

-NED on

$L_{2}$

-NED on

![]() $\{x_{i,n}\,\epsilon _{i,n}:i\in D_{n}\}$

in Assumption A.9. Thus, we are ready to establish asymptotic properties of the HGMM estimator.

$\{x_{i,n}\,\epsilon _{i,n}:i\in D_{n}\}$

in Assumption A.9. Thus, we are ready to establish asymptotic properties of the HGMM estimator.

Next, we obtain the asymptotic distribution of the HGMM estimator

![]() $\hat {\theta }_{HGMM}$

. To do so, we need some regularity conditions for

$\hat {\theta }_{HGMM}$

. To do so, we need some regularity conditions for

![]() $\Gamma _{n}(\theta )\equiv \frac {\partial g_{n}(\theta )}{\partial \theta '}$

,

$\Gamma _{n}(\theta )\equiv \frac {\partial g_{n}(\theta )}{\partial \theta '}$

,

![]() $\Gamma _{n}\equiv \Gamma _{n}(\theta _{0})$

, and

$\Gamma _{n}\equiv \Gamma _{n}(\theta _{0})$

, and

![]() $V_{n}\equiv n\operatorname {\mathrm {var}}\left (g_{n}(\theta _{0})\right )$

. We collect the expressions of these matrices in Section C of the Supplementary Material. Notice that the

$V_{n}\equiv n\operatorname {\mathrm {var}}\left (g_{n}(\theta _{0})\right )$

. We collect the expressions of these matrices in Section C of the Supplementary Material. Notice that the

![]() $V_{n}$

in Eq. (C.2) is a block diagonal matrix. This is because a linear form and a quadratic form (with all diagonal elements being zero) are uncorrelated, as suggested by Eq. (3.2) in Kelejian and Prucha (Reference Kelejian and Prucha2001).

$V_{n}$

in Eq. (C.2) is a block diagonal matrix. This is because a linear form and a quadratic form (with all diagonal elements being zero) are uncorrelated, as suggested by Eq. (3.2) in Kelejian and Prucha (Reference Kelejian and Prucha2001).

Assumption 13.

![]() $\lim _{n\to \infty }V_{n}\equiv \lim _{n\to \infty }n\operatorname {\mathrm {var}}\left (g_{n}(\theta _{0})\right )=V_{0}$

for some positive-definite matrix

$\lim _{n\to \infty }V_{n}\equiv \lim _{n\to \infty }n\operatorname {\mathrm {var}}\left (g_{n}(\theta _{0})\right )=V_{0}$

for some positive-definite matrix

![]() $V_{0}$

.

$V_{0}$

.

Theorem 4. Under Assumptions 1–9, 12, and 13, if the

![]() $\alpha $

in Assumption 4(ii) satisfies

$\alpha $

in Assumption 4(ii) satisfies

![]() $\alpha>\left [\frac {2}{\min (2,\gamma )}+1\right ]d$

, then

$\alpha>\left [\frac {2}{\min (2,\gamma )}+1\right ]d$

, then

When

![]() $\Omega \propto V_{0}^{-1}$

,

$\Omega \propto V_{0}^{-1}$

,

![]() $\sqrt {n}(\hat {\theta }_{HGMM}-\theta _{0})\xrightarrow {d}N(0,(\Gamma _{0}'V_{0}^{-1}\Gamma _{0})^{-1})$

.

$\sqrt {n}(\hat {\theta }_{HGMM}-\theta _{0})\xrightarrow {d}N(0,(\Gamma _{0}'V_{0}^{-1}\Gamma _{0})^{-1})$

.

The condition

![]() $\alpha>\left [\frac {2}{\min (2,\gamma )}+1\right ]d$

ensures that the NED coefficient satisfies the condition of Lemma A.3 in Jenish and Prucha (Reference Jenish and Prucha2012). If

$\alpha>\left [\frac {2}{\min (2,\gamma )}+1\right ]d$

ensures that the NED coefficient satisfies the condition of Lemma A.3 in Jenish and Prucha (Reference Jenish and Prucha2012). If

![]() $|w_{ij,n}|$

decreases exponentially as

$|w_{ij,n}|$

decreases exponentially as

![]() $d_{ij}$

increases, this condition becomes unnecessary.

$d_{ij}$

increases, this condition becomes unnecessary.

Following Lin and Lee (Reference Lin and Lee2010), we estimate

![]() $V_{0}$

in Eq. (C.2) in the Supplementary Material by replacing

$V_{0}$

in Eq. (C.2) in the Supplementary Material by replacing

![]() $\Sigma _{n}\equiv \operatorname {\mathrm {var}}(\psi (\epsilon _{n}))$

by

$\Sigma _{n}\equiv \operatorname {\mathrm {var}}(\psi (\epsilon _{n}))$

by

![]() $\hat {\Sigma }_{n}\equiv \operatorname {\mathrm {diag}}(\psi (\hat {\epsilon }_{1,n})^{2},\ldots ,\psi (\hat {\epsilon }_{n,n})^{2})$

and replacing

$\hat {\Sigma }_{n}\equiv \operatorname {\mathrm {diag}}(\psi (\hat {\epsilon }_{1,n})^{2},\ldots ,\psi (\hat {\epsilon }_{n,n})^{2})$

and replacing

![]() $\Sigma _{n}^{d}$

by

$\Sigma _{n}^{d}$

by

![]() $\hat {\Sigma }_{n}^{d}\equiv (\psi (\hat {\epsilon }_{1,n})^{2},\ldots ,\psi (\hat {\epsilon }_{n,n})^{2})'$

, where

$\hat {\Sigma }_{n}^{d}\equiv (\psi (\hat {\epsilon }_{1,n})^{2},\ldots ,\psi (\hat {\epsilon }_{n,n})^{2})'$

, where

![]() $\hat {\epsilon }_{i,n}=y_{i,n}-z_{i,n}'\hat {\theta }$

is the residual, i.e., the estimator for

$\hat {\epsilon }_{i,n}=y_{i,n}-z_{i,n}'\hat {\theta }$

is the residual, i.e., the estimator for

![]() $V_{0}$

is

$V_{0}$

is

Similarly, we estimate

![]() $\Gamma _{n}$

in Eq. (C.1) in the Supplementary Material by

$\Gamma _{n}$

in Eq. (C.1) in the Supplementary Material by

Then, we can estimate the asymptotic variance of the optimal GMM estimator by

![]() $(\hat {\Gamma }_{n}'\hat {V}^{-1}\hat {\Gamma }_{n})^{-1}$

.

$(\hat {\Gamma }_{n}'\hat {V}^{-1}\hat {\Gamma }_{n})^{-1}$

.

Theorem 5. Suppose Assumptions 1–9, 12, and 13 hold. And conditional on

![]() $x_{i,n}$

, the probability density function (p.d.f.) of

$x_{i,n}$

, the probability density function (p.d.f.) of

![]() $\epsilon _{i,n}$

, denoted by

$\epsilon _{i,n}$

, denoted by

![]() $f_{in}(\cdot |x_{i,n})$

, satisfies

$f_{in}(\cdot |x_{i,n})$

, satisfies

![]() $\sup _{i,n,\epsilon ,x}|f_{in}(\epsilon |x)|<\infty $

and

$\sup _{i,n,\epsilon ,x}|f_{in}(\epsilon |x)|<\infty $

and

![]() $\sup _{i,n,\epsilon ,x}|\epsilon f_{in}(\epsilon |x)|<\infty $

. Suppose

$\sup _{i,n,\epsilon ,x}|\epsilon f_{in}(\epsilon |x)|<\infty $

. Suppose

![]() $\gamma \geq 2$

. Then, (1)

$\gamma \geq 2$

. Then, (1)

![]() $\hat {V}\xrightarrow {p}V_{0}$

and (2)

$\hat {V}\xrightarrow {p}V_{0}$

and (2)

![]() $\hat {\Gamma }_{n}\xrightarrow {p}\Gamma _{0}$

.

$\hat {\Gamma }_{n}\xrightarrow {p}\Gamma _{0}$

.

The conditions

![]() $\sup _{i,n,\epsilon ,x}|f_{in}(\epsilon |x)|<\infty $

and

$\sup _{i,n,\epsilon ,x}|f_{in}(\epsilon |x)|<\infty $

and

![]() $\sup _{i,n,\epsilon ,x}|\epsilon f_{in}(\epsilon |x)|<\infty $

are satisfied by most continuous and piecewise continuous p.d.f.s in practice. As long as

$\sup _{i,n,\epsilon ,x}|\epsilon f_{in}(\epsilon |x)|<\infty $

are satisfied by most continuous and piecewise continuous p.d.f.s in practice. As long as

![]() $f_{in}(x)$

is continuous and

$f_{in}(x)$

is continuous and

![]() $\lim _{|x|\to \infty }|xf_{in}(x)|=0$

, Assumption 2(ii) holds. Even when

$\lim _{|x|\to \infty }|xf_{in}(x)|=0$

, Assumption 2(ii) holds. Even when

![]() $f_{in}(\cdot )$

is not continuous, Assumption 2(ii) is still satisfied in many cases, e.g., the p.d.f. of an exponential distribution or a uniform distribution.

$f_{in}(\cdot )$

is not continuous, Assumption 2(ii) is still satisfied in many cases, e.g., the p.d.f. of an exponential distribution or a uniform distribution.

3.4 Finite Sample Breakdown Point Analysis

Breakdown point analysis is a key criterion for assessing the robustness of a statistical procedure. “Informally, a breakdown of a statistical procedure means that the procedure no longer conveys useful information on the data-generating mechanism” (Genton and Lucas, Reference Genton and Lucas2003). The concept of breakdown point varies across different literature. Traditionally, the breakdown point refers to the fraction of contamination (or outliers) that results in unbounded estimators or estimators on the boundary of the parameter space (Hampel, Reference Hampel1971). This definition is well-suited for independent data, but Genton and Lucas (Reference Genton and Lucas2003) argue that it is not readily applicable to dependent data. Thus, they extend the definition in Hampel (Reference Hampel1971) to accommodate dependent data. Genton, (Reference Genton, Dutter, Filzmoser, Gather and Rousseeuw2003, p. 151) finds that when the spatial weights matrix is lower triangular, the breakdown point for the MLE of a pure SAR model without exogenous variables is zero; when

![]() $w_{ij}=1$

if and only if

$w_{ij}=1$

if and only if

![]() $|i-j|=1$

, the asymptotic breakdown point of the least median of squares estimator for the pure SAR model with additive outliers is 14.4%.

$|i-j|=1$

, the asymptotic breakdown point of the least median of squares estimator for the pure SAR model with additive outliers is 14.4%.

Since “the breakdown point is most useful in small sample situations” (Huber and Ronchetti, Reference Huber and Ronchetti2009, p.279), we focus on finite sample breakdown point. As in Genton and Lucas (Reference Genton and Lucas2003), we consider innovation outliers, i.e., outliers in the error terms

![]() $\epsilon _{i,n}$

.Footnote

12

Unlike additive outliers used in Genton (Reference Genton, Dutter, Filzmoser, Gather and Rousseeuw2003), the impact of innovation outliers can be propagated through the spatial weights matrix

$\epsilon _{i,n}$

.Footnote

12

Unlike additive outliers used in Genton (Reference Genton, Dutter, Filzmoser, Gather and Rousseeuw2003), the impact of innovation outliers can be propagated through the spatial weights matrix

![]() $W_{n}$

to all dependent variables

$W_{n}$

to all dependent variables

![]() $y_{j,n}$

’s. Assuming the presence of contamination

$y_{j,n}$

’s. Assuming the presence of contamination

![]() $\zeta \bar {\epsilon }_{n}$

, where

$\zeta \bar {\epsilon }_{n}$

, where

![]() $\zeta \in [0,\infty ]$

controls the magnitude of the contamination, the model then becomes

$\zeta \in [0,\infty ]$

controls the magnitude of the contamination, the model then becomes

So,

![]() $Y_{n}=S_{n}^{-1}(X_{n}\beta +\epsilon _{n}+\zeta \bar {\epsilon }_{n})$

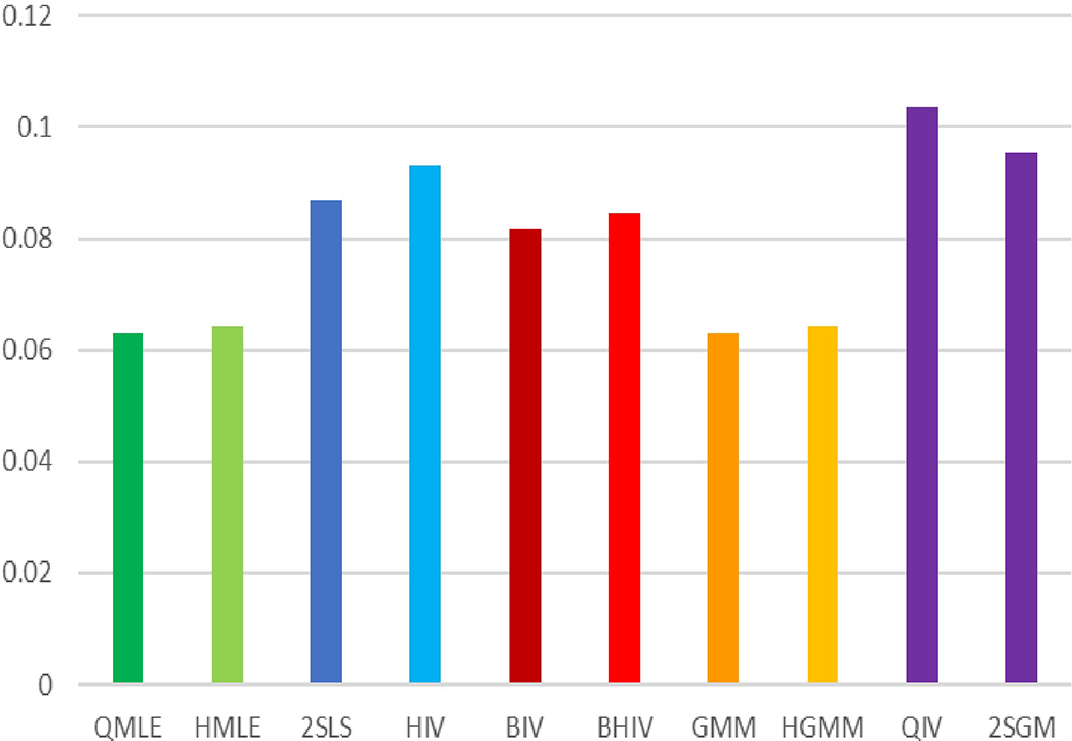

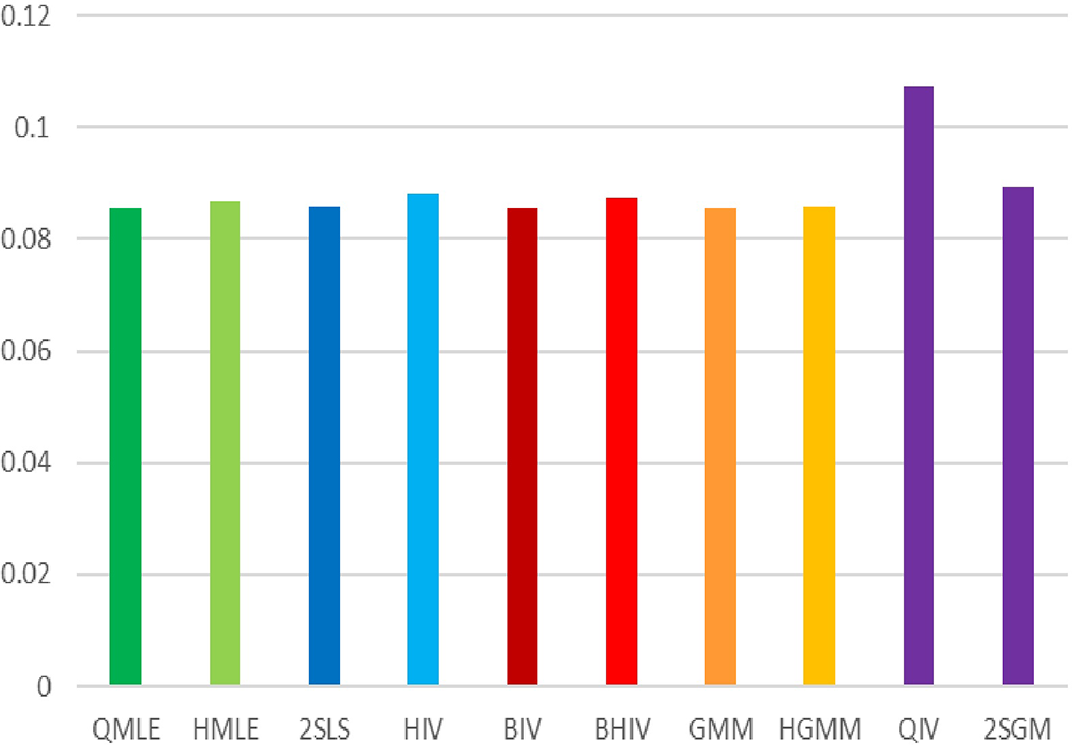

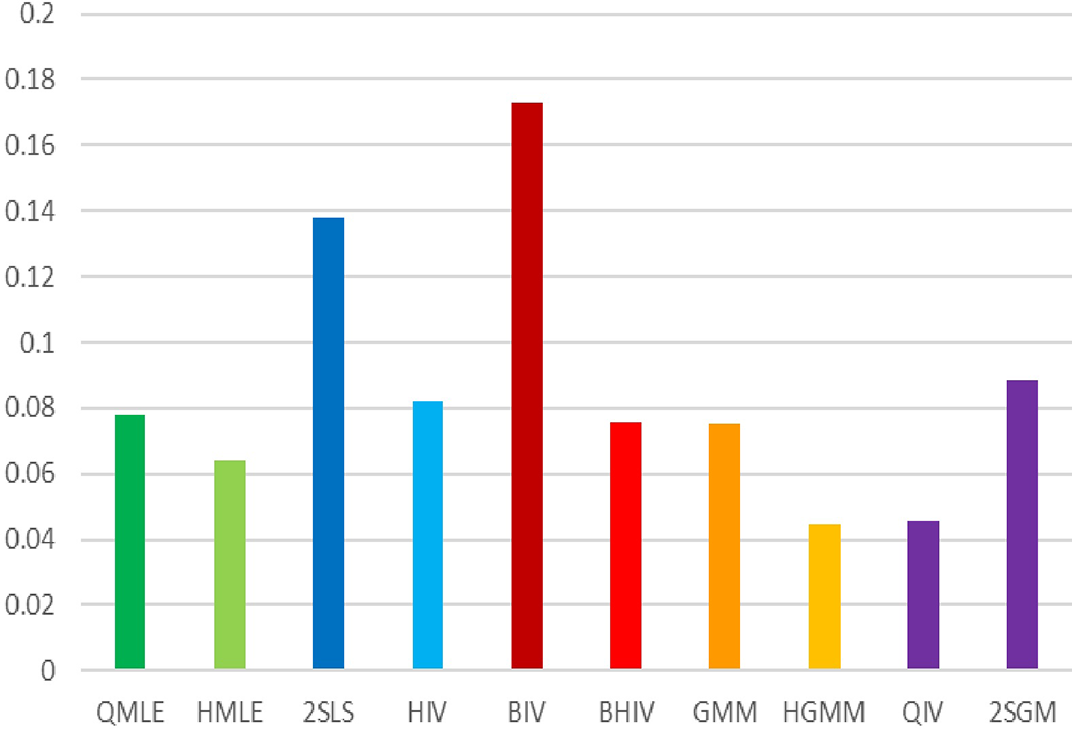

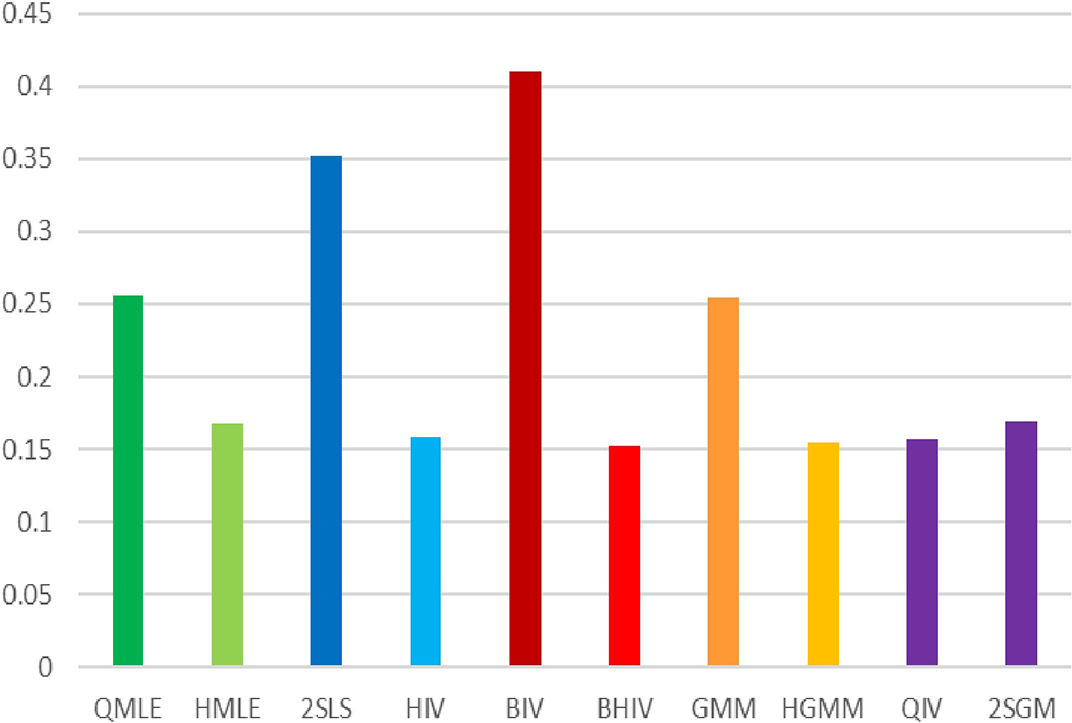

. Suppose all entries of