In Australia, approximately one in seven young people have clinical disorders such as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and anxiety and conduct disorder (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Johnson, Hafekost, Boterhoven de Haan, Sawyer, Ainley and Zubrick2015). Earlier onset of mental disorders has been associated with adverse clinical issues over the lifetime, such as risky behaviours, suicide risk and poor academic outcomes (Donovan & Spence, Reference Donovan and Spence2000). In addition to the prevalence of mental disorders, one in eight young people are estimated to have experienced abuse before the age of 15 (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2016). International estimates have suggested the prevalence of young people who have experienced trauma is as high as two out of three school-age children (Perfect et al., Reference Perfect, Turley, Carlson, Yohanna and Saint Gilles2016). The evidence suggests that Australian adolescents do not feel confident or secure in themselves, and commonly cite mental health as a barrier to success at school (Mission Australia, 2019; Tucci et al., Reference Tucci, Mitchell and Goddard2007). The schools these young people attend have an opportunity to remediate these difficulties. This study investigates specialised methods used in a school setting to reduce emotional and behavioural difficulties and keep vulnerable students engaged in education.

Trauma-Informed Practice in Education

There is clearly an important role for schools to play in developing students’ cognitive, social and emotional skills (Bloom, Reference Bloom1995). The statistics mentioned above demonstrate that Australian schools need to cater for students displaying a range of symptoms and behaviours, including poor emotional regulation, anxiety, mood disturbance, peer conflict, school refusal, conduct and oppositional defiance issues, hyperactivity, aggressive behaviour, limited attentional capacities and hypervigilance.

Young people with these difficulties become students at schools who hope to succeed but are more likely to have lower academic achievement, lower IQ scores, impaired cognitive functioning and language difficulties (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Greenwald, Gadd, Ristuccia, Wallace and Gregory2009; Perfect et al., Reference Perfect, Turley, Carlson, Yohanna and Saint Gilles2016).

Since the seminal Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study, it has been understood that trauma affects schooling and educational outcomes (Anda et al., Reference Anda, Felitti, Bremner, Walker, Whitfield, Perry and Giles2005; Cole et al., Reference Cole, Greenwald, Gadd, Ristuccia, Wallace and Gregory2009). Student’s with ACEs — such as physical and emotional abuse and witnessing domestic violence — are more likely to perform poorly in school (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Jacob, Gross, Perron, Moore and Ferguson2018), be chronically absent (Stempel et al., Reference Stempel, Cox-Martin, Bronsert, Dickinson and Allison2017), repeat a grade, and get suspended or expelled (Wolpow et al., Reference Wolpow, Johnson, Hertel and Kincaid2009). Sustainable trauma-informed practices in education are needed to address these issues (Chafouleas et al., Reference Chafouleas, Johnson, Overstreet and Santos2016).

While Australian schools have incorporated beneficial positive behaviour support practices, many schools are still struggling with managing complex behaviours without resorting to suspension and expulsion (Howard, Reference Howard2018). Trauma-informed practices provide much needed support and skill development for teachers who commonly express a need for more support (Alisic, Reference Alisic2012), and also provide benefits to students without trauma histories (Stokes & Turnbull, Reference Stokes and Turnbull2016). Through maintaining enrolment and higher education levels, students are more likely to have positive health and wellbeing outcomes, and a reduced likelihood of forensic involvement (ABS, 2016).

In trauma-informed schools, staff at all levels have a basic understanding of trauma and how trauma affects student learning and behaviour in the school environment (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014). The key elements of building teachers’ trauma-informed capacities necessary to deliver a schoolwide model include training, coaching and behavioural expertise (Chafouleas et al., Reference Chafouleas, Johnson, Overstreet and Santos2016). Trauma-focused training is effective in enhancing knowledge, fostering trauma-informed approaches, and shifting underlying attitudes and beliefs (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Baker and Wilcox2012; Green et al., Reference Green, Saunders, Power, Dass-Brailsford, Schelbert, Giller, Wissow, Hurtado-de-Mendoza and Mete2015).

Effectiveness of multitiered practice models

A systematic review by Berger (Reference Berger2019) reviewed multitiered trauma-informed models in schools and found that in addition to Tier 1 trauma-focused training, many models included Tier 2 collaboration with mental health and behavioural specialists that included consulting and leading school-based group interventions. Tier 2 group programs, such as Cognitive Behavioural Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) and BounceBack Resiliency Program, have led to improvements in school engagement and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression scores (Berger & Gelkopf, Reference Berger and Gelkopf2009; Cichetti, Reference Cicchetti2017; Perry & Daniels, Reference Perry and Daniels2016).

Multitiered trauma-informed models have led to improvements in internalising and externalising behaviours, increases in learning, concentration, school attendance and on-task behaviour, and decreases in discipline referrals and suspensions (Dorado et al., Reference Dorado, Martinez, McArthur and Leibovitz2016; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Levy, Smith, Pinne and Neese2015). An evaluation conducted in an Australian setting demonstrated up to 90% reduction in school suspensions (Stevens, Reference Stevens2012, Reference Stevens2013a) and 44% reduction in students being sent out of class (Stevens, Reference Stevens2013a, Reference Stevens2013b).

The Berry Street Education Model, which is a multitiered trauma-informed model applicable to mainstream school settings, has also led to improved student self-regulation, peer relationships, teacher relationships, student concentration and academic achievement (Stokes & Turnbull, Reference Stokes and Turnbull2016). Berger et al. (Reference Berger, Abu-Raiya and Benatov2016) also reported that a universal schoolwide intervention buffered against teachers’ exposure to vicarious trauma and had a positive impact on teachers’ self-efficacy and optimism.

The current study: Investigating a schoolwide approach

Researchers have called for further empirical evidence on the effectiveness of schoolwide trauma-informed models due to various limitations in the existing research. Previous studies have lacked clarity regarding what training teachers are receiving and the roles that leadership and psychologists play as consultants (Berger, Reference Berger2019). Most of the quantitative data generated so far has been derived from teacher reports, leaving a void of parent and child perspectives. Single subject designs and multiple baseline designs have been encouraged for future evaluations of trauma-informed practices (Chaufoleas et al., 2016). Furthermore, most of the research has investigated approaches implemented in international mainstream education settings. There is a significant gap in research that evaluates practices in Australian specialist school settings.

The present study attempts to provide quantitative data demonstrating whether a schoolwide trauma-informed intervention is effective in making positive adjustments for students with complex emotional and behavioural needs. Based on comparable studies, it was predicted that the intervention would reduce conduct problems, peer problems and global difficulties. Further, it was presumed that the intervention would be the most effective for students who had recently commenced at the school.

Method

Setting

This study took place within MacKillop Education, which is a small nongovernment alternative school operating in Australia. Many students at the school have diagnosed emotional and behavioural disorders that require high levels of classroom adjustment. Classroom approaches are informed by international trauma-informed education principles, and teachers are supported with relevant professional development.

Participants

The sample was comprised of students who attend at one of the MacKillop Specialist School campuses that provides education to students from P–12. The sample consists of both primary and secondary school students. Students are referred to the school for various reasons, including disengagement, aggression and severe emotional issues.

The total population for this study (N = 18) consisted of both students who had commenced at the school at the beginning of 2019 (n = 8), as well as a sample of students who had an existing enrolment at the school prior to 2019 (n = 10). During the intervention period, 64 students attended the school. Some students did not receive the full intervention due to transitioning to other schools. Only students who had two valid data points were included.

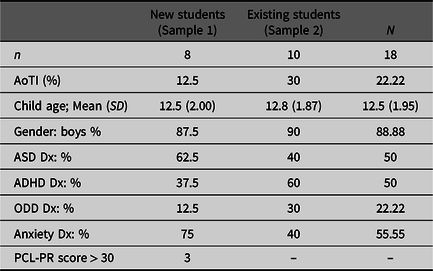

Demographic data in Table 1 shows the population consists of 89% male, mean age = 12.5, standard deviation = 1.95, (age range = 9–16), 22% Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Many of the students in the population had existing diagnoses including autism spectrum disorder, ADHD and anxiety. Trauma symptoms were screened for with newly enrolled students using the PCL-PR. While some students had mild symptoms, three students exceeded the clinical cut-off (Weathers & Ford, Reference Weathers and Ford1996).

Table 1. Demographic information

Note: AoTI, Aboriginal or Torres Straight Islander; Dx, diagnosis; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; ADHD, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD, oppositional defiance disorder; PCL-PR, Stress Disorder Checklist, Parent Report.

ReLATE model of trauma-informed practice

The Rethinking Learning and Teaching Environments (ReLATE) model has its foundations in the Sanctuary model (Yanosy et al., Reference Yanosy, Harrison and Bloom2009) and is informed by a number of key trauma-informed practice guides, including the SAMHSA (2014) principles of trauma-informed care, ‘Helping Traumatized Children Learn’ (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Eisner, Gregory and Ristuccia2013), and the National Child Traumatic Stress Network literature (2016).

ReLATE promotes schoolwide trauma-specific interventions that are designed to repair the dysregulated stress response, enhance self-regulation abilities, embed routines and rituals that create safety and predictability, and repair relational capacities. Classrooms consist of safe and supportive learning environments where students are not just known but understood and teachers are supported in their professional growth. While a comprehensive exploration of the components of the model is currently being undertaken in a larger study, and hence beyond the scope of this study, two core components of the model are discussed below.

Sanctuary model

All staff at the school are trained in the Sanctuary model, which educates staff on trauma-informed practice (Bloom, Reference Bloom1997; Esaki et al., Reference Esaki, Hopson and Middleton2014; Yanosy et al., Reference Yanosy, Harrison and Bloom2009). The 2-day group training is completed at the commencement of employment and focuses on safety and creating an understanding of how past adversity can continue to have an impact throughout life. The Sanctuary model enables entire organisations to understand the effects of trauma and enable others to cope more effectively with stress and trauma. The training focuses on the four ‘pillars’ outlined in the Sanctuary model: (1) trauma theory: scientific research and knowledge about trauma, adversity, and attachment; using psychoeducation to bring understanding of trauma and behaviour to students and staff; (2) the Sanctuary commitments of organisational practice; (3) a shared language discussion framework called ‘S.E.L.F.’ (Safety; Emotion; Loss; Future); and (4) a Sanctuary toolkit that provides practical tools, including the community meeting, self-care plans and individual safety plans for all staff and students.

Community meetings

The community meeting is a core ReLATE intervention that is practised at the start and end of each school day. Meetings generally occur by bringing people into a circle, asking each other three questions, and listening carefully to the answers. The aim of the meeting is to increase emotional expression, help seeking and goal setting. The three questions are: How you are feeling? What is your goal for today? and Who can you ask for help? (Sanctuary Model, 2012).

Safety plans

Every student in the ReLATE intervention had a personal safety plan that listed several personalised strategies they could use any time they were not feeling safe within the classroom. Safety plans also included known triggers and were displayed in classrooms. Safety plans were developed when the student first began at the school, alongside education about the zones of regulation (Kuypers, Reference Kuypers2013). The safety plans of primary students included simple visual layouts and images, whereas secondary students used words and phrases to denote their strategies.

Therapeutic crisis intervention, debriefing and reflective practice

Therapeutic Crisis Intervention (TCI) training was completed by all school staff upon commencement of employment. TCI is an intervention system that teaches a variety of methods for crisis prevention and management. TCI is a 3-day group training that involves seminar style instruction as well as individual coaching and practice in methods to de-escalate potential crises, effectively manage crises, reduce injuries to students and staff, and teaches constructive ways to handle stressful situations (Residential Child Care Project, 2016).

Life Space Interview

The Life Space Interview (LSI) is a component of ReLATE adapted from TCI that occurred in response to every critical incident that occurred at the school. Critical incidents included: (1) dangerous or highly disruptive behaviours by a student, (2) community concern, (3) escape or absconding by a student, (4) injury sustained by a student or staff member, (5) property damage by a student, and (6) physical assault by a student.

The LSI is a structured discussion between staff and student that focuses on how the student can stay in control and not resort to violent behaviours. The staff member goes through several steps, such as isolating the conversation, listening empathetically, connecting emotions to behaviours, and collaborating with the student to identify more adaptive behaviours.

The LSI process was adapted according to the age and developmental stage of the student. Primary school students with a concrete understanding of emotions at times had their LSIs paired with story books and drawing activities to accommodate for lagging social and language skills. Secondary school students who were able to think abstractly had more conversational LSIs that focused on perspective taking and learner confidence.

Debriefing

ReLATE also includes protocols for debriefing in response to incidents at the school. Debriefs ran for 90 minutes and occurred in response to critical incidents. Debriefs took place approximately weekly and involved staff who observed the incident. Debriefs are chaired by school leaders, including the principal and psychologist. The debrief process includes staff reflective practice and a behavioural analysis. Additional individual reflective practice and coaching opportunities were offered to teachers in regular supervision each term as well as clinical discussions with the psychologist. Supervision and clinical reflective practice sessions typically occurred for 60 minutes and occurred two to three times per term.

Professional development seminars were provided to the staffing group at the beginning of each term and covered critical incident management, behavioural strategies and recovery tools. Professional development days also included guest lectures on topics including motivational interviewing techniques and fostering language development.

Measures

Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

The 25-item Parent Report version of the SDQ (Goodman, Reference Goodman2001) was used to assess positive and negative attributes of students. Each item is scored on a 3-point scale with 0 = Not true, 1 = Somewhat true, and 2 = Certainly true. The responses from the questionnaire derive five subscales of five items each: the emotional symptoms subscale, the conduct problems subscale, the hyperactivity subscale, the peer problems subscale, and the prosocial behaviour subscale. An additional total difficulties scale is derived from the combination of the negative attribute subscales. A final ‘Impact Score’ category was derived from additional questions that asked about the impact that students’ behaviour has on the family as a whole, homelife, friendships, learning and leisure activities.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist — 4th edition, Parent Report (PCL-PR)

The PCL-PR is a 17-item, parent-report questionnaire of PTSD symptoms (Weathers & Ford, Reference Weathers and Ford1996). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale to derive a total severity score. The PCL-PR symptom severity score has high internal consistency (alpha = .91 (Daviss et al., Reference Daviss, Mooney, Racusin, Ford, Fleischer and McHugo2000). Students’ experiences of trauma were observed through referral information provided by schools and families, as well as clinical assessment reports that included case histories. Observed experiences of trauma included physical abuse, witnessing family violence, neglect, removal from primary caregiver, abandonment, incarceration of a family member, and death of a family member.

Procedure

In the current study, the intervention was carried out schoolwide over a 12-month period and involved school leadership, psychologists, teachers and education support. Data collection and monitoring was overseen by psychologists employed by the school. Data were obtained through parents of the students completing standardised assessment measures in hard-copy formats. Parents completed the questionnaire as part of the intake process at the school. Baseline data were collected in December 2018. The postintervention questionnaire was administered to parents to complete while the students completed an annual testing session at the school. Postintervention data collection occurred in December 2019. Questionnaires were cross-referenced to ensure that the same rater was used across time points. Scores were then digitalised for analysis. All parents and guardians complete consent forms prior to enrolment at MacKillop Specialist School that includes permission to include their child’s data in research projects.

In 2019, there were 11 new students commencing enrolment. Therefore, three students had unusable data due to missing time points that were not contributed to Sample 1. Unlike Sample 1 who completed the PCL-PR as part of the school intake process, Sample 2 participants did not complete the PCL-PR.

Data analysis

To evaluate the effects of the intervention, a series of repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were carried out. The ANOVAs explored whether significant adjustments occurred over a 12-month period. This analysis was followed up with the Reliable Change Indicator analysis to determine effect size and in case nonsignificant results needed correction.

Reliable Change Indicator (RCI)

The RCI method was developed to determine whether ‘the difference in score from pre-to-post-treatment is meaningful or due to random error’ (Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Robinson and Splaine2002, p. 510; Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, Follette and Revenstorf1984). The calculation of reliable change involves estimates of a scale’s internal consistency and the standard deviation of the sample relating to the dependent variable. An absolute value of reliable change is calculated as 1.96 times (z-score) the standard error of the difference between scores of a specific scale administered across time points. The Reliable Change scores derived in Table 2 are based on Australian data and psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire published by Hawes and Dadds (Reference Hawes and Dadds2004) and Mellor (Reference Mellor2004).

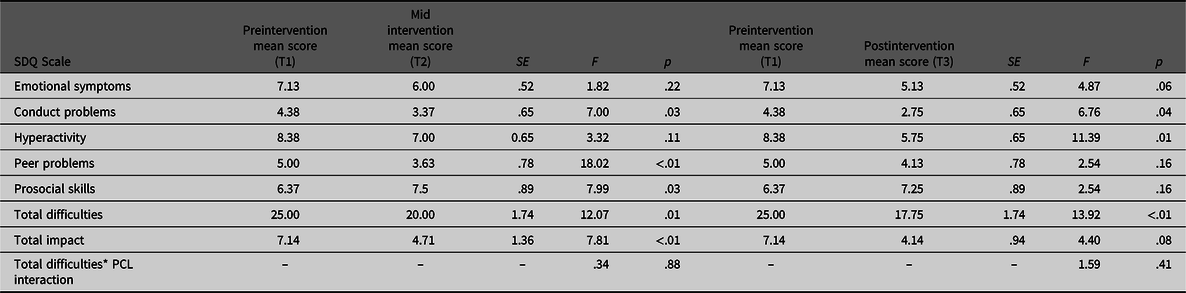

Table 2. Sample 1 (New students; n = 8) multivariate test results by SDQ Domain T1–T2; T1–T3

Note: SDQ, Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire; T1, Time 1; T2, Time 2; T3, Time 3.

Results

Table 2 presents Sample 1 mean scores (and standard deviations) for the various SDQ subscales as outcome measures on the three occasions: Time 1, which was collected at baseline; Time 2, which was collected 6 months into the intervention; and Time 3, which was collected 12 months after the intervention commenced.

Over the initial 6 months (T1–T2), significant reduction in scores was found for conduct problems (F = 7.00, p = .03), peer problems (F = 18.02, p < .01), total difficulties (F = 12.07, p = .01), and total impact (F = 7.81, p < .01), while a significant increase was seen for prosocial skills (F = 7.99, p < .03). Reduction in mean scores was seen for emotional symptoms and hyperactivity but not found to be significant. There was no significant interaction effect found between total difficulties and PCL score.

Over 12 months (T1–T3), significant reduction in scores was found for conduct problems (F = 6.76, p = .04), hyperactivity (F = 11.39, p = .01), and total difficulties (F = 12.07, p < .01). Reduction in mean scores was seen for emotional symptoms, and this was on the cusp of being significant (p = .06). Similarly, total impact was approaching significance with a substantial reduction found in the mean. Further exploration of these reductions was conducted through the RCI process displayed in Table 3.

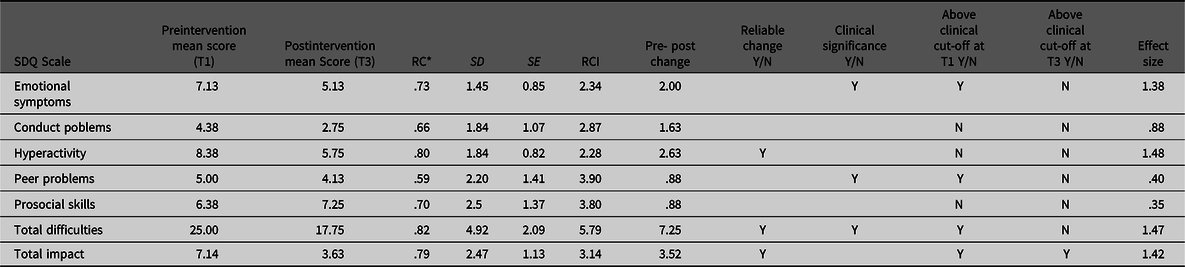

Table 3. Sample 1 (new students; n = 8) Reliable Change Index results by SDQ domain, T1–T3

Note: SDQ, Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire; T1, Time 1; T2, Time 2; T3, Time 3.

Clinically significant changes

The RCI method (Table 3) further determined that the intervention led to significant benefits in many of the outcome variables. Over the 12-month intervention (T1–T3), effect sizes were found to be small for peer problems (d = .40) and prosocial skills (d = .35), and large for all other outcome measures.

Table 3 also demonstrates that although total impact fell below the threshold for statistically significance in the ANOVA analysis, the mean difference is above the reliable change absolute threshold, which infers that reliable change has occurred. Further, the reduction from T1 (7.14) to T3 (3.63) signifies that the intervention has come close to reducing the impact score to below the clinical threshold (3.0).

Clinically significant reduction was found for total difficulties, given the change score (7.25) is above the absolute threshold of reliable change (5.79), the mean score at baseline (25) was above the clinical cut-off score (20), and the postintervention mean score (17.75) was below the clinical cut-off. Though emotional symptoms was only approaching statistical significance (Table 2) and the pre-post change (2.00) did not quite reach the threshold for reliable change (2.34), an adjustment from above the clinical cut-off at baseline to below the clinical cut-off postintervention was noteworthy.

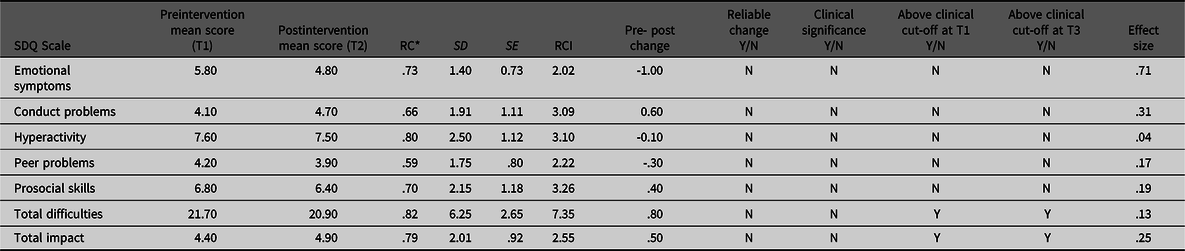

Table 4 displays a comparison sample of existing students who had continual enrolment at the school prior to 2019. Unlike in Sample 1, no reliable pre-post intervention change was found for any of the SDQ subscale outcome measures. Effect sizes were considerably smaller in Sample 2, with most domains in the small range (d = .04–.31) and emotional symptoms in the medium effect size range (d = .71).

Table 4. Sample 2 (existing students; n = 10) Reliable Change Index tesults by SDQ domain

Note: SDQ, Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire; T1, Time 1; T2, Time 2; T3, Time 3.

Discussion

This study explored whether specialised trauma-informed methods used in a school setting can reduce student emotional and behavioural difficulties. The intervention consisted of a 12-month implementation of the ReLATE model in a specialist school.

As predicted, the intervention led to reduction in conduct problems, peer problems and global difficulties. Additionally, results suggested that there was beneficial adjustment in all outcome domains. Prosocial skills and peer problems improved significantly over the initial 6 months, though this was not maintained at 12-months. Findings from total difficulties reduction were statistically significant with a large effect size. The intervention displayed large effect sizes over the 12-month period. While past studies focused on teacher-observed adjustments, this study demonstrated a parent perspective and the generalised benefit in homelife, friendships, and learning and leisure activities through the finding of meaningful positive change in global impact.

As predicted, the intervention was found to be more effective for new students, though existing students showed small positive adjustments in most outcome domains. An explanation for the weaker benefits displayed by Sample 2 could be due to the fact some existing students were already receiving the ReLATE intervention for 2 years prior to the intervention period reported in the study. It is possible that students in Sample 2 had already reaped the majority of benefits from the intervention and started from a lower baseline of behavioural difficulty with less scores in the clinical cut-off range.

Importantly, teachers reported that existing students were more likely to have fewer emotional and behavioural difficulties than new students, and as a result, the focus for these students was more likely to shift toward academic rigour and learning confidence during the 12-month intervention period.

In comparison, students in Sample 1 had more capacity to improve. These students likely started from a higher baseline of difficulty and received their first exposure to the ReLATE interventions. The adjustment could also be attributed to new students and parents being exposed to a fresh learning environment and adopting new perspectives from the psychoeducation provided, whereas existing students had already consolidated these learnings and were accustomed to the environment.

Internalising problems adjustment

The reduction in emotional symptoms for Sample 1 was on the cusp of being significant. The adjustment was more substantial over a 12-month period compared to the 6-month period. This is likely due to the cumulative feeling of safety and security as the year progressed. This result is consistent with findings from Holmes et al. (Reference Holmes, Levy, Smith, Pinne and Neese2015), who reported improvements in internalising problems for students who completed the Head Start Trauma Smart program. While the Holmes et al. (Reference Holmes, Levy, Smith, Pinne and Neese2015) study assessed preschool children, the participants in Sample 1 were aged from 9 to 16, indicating that schoolwide trauma-informed models may lead to improvements in internalising difficulties for older children and adolescents too.

There are a number of ReLATE practices that could have led to this reduction. The community meeting is a repetitive, patterned and predictable activity that can produce a sensation of emotional safety for students who have a limited internal sense of structure and benefit from clear boundaries and expectations (Downey, Reference Downey2012). Students who formerly were highly anxious when arriving at school began to display an increasing sense of confidence, knowing their day would start in a predictable manner. This emphasis on clear structure and routine is also supported by visual schedules and other daily rhythmic routines like walking around the block as a class. Furthermore, anxiety was reduced by a process in which students commenced their day with individualised goal setting that maximised mastery relevant to their academic level, rather than performance compared to other peers (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2002). Students who became anxious at school were supported to learn strategies to manage their emotions by using their safety plan.

Externalising problems adjustments

Hyperactivity

Hyperactivity improved at a consistent rate throughout the intervention. In Sample 1, 37.5% of students had a diagnosis of ADHD. After 12 months of intervention, the mean hyperactivity score for the sample reduced from being in the ‘clinical’ category to being classified as ‘slightly raised’. This clinically and statistically significant finding is supported by a meta-analysis conducted by DuPaul et al. (Reference DuPaul, Eckert and Vilardo2012), who found that the average effect size for within-subjects, school-based ADHD interventions was .72. School-based interventions that have been found to reduce hyperactivity include token-reinforcement systems, replacement behaviour training and academic choice-making interventions (DuPaul, Reference DuPaul2007; DuPaul & Weyandt, Reference DuPaul and Weyandt2006). Consistent with this research, ReLATE interventions included a prize-box system for primary students in which students received points for displaying desired behaviours and an academic-menu strategy that allowed secondary students to choose a method of task engagement they were comfortable with. For example, in morning reading, one student chose to read from a car magazine while another chose to read subtitles from an online video. Additionally, functional assessments were completed by the psychologist and replacement behaviour training was carried out by teachers.

The current study found a larger than average effect size (d = 1.48), which may be accounted for by a reduction in the symptom of hyperarousal which can be displayed by trauma-affected students. An alternative explanation for the reduction in hyperactivity is students widening their ‘Window of Tolerance’, resulting in less stress-response activation and reduced hyperarousal (Siegel, Reference Siegel1999).

The ReLATE intervention attempted to expand the window of tolerance by challenging students in accordance with the zones of proximal development theory that contends growth occurs when the challenge is safe but not too safe (Ogden, Reference Ogden2009; Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978). For primary school students, they were reminded that their goals should not be in their ‘comfort zone’ or the ‘too-hard zone’, rather they should be in the ‘growth zone’. As students’ window of tolerance expands and they progressively experience the safety, predictability and consistency of the school, hyper-arousal is likely to decrease.

Peer problems

New students’ level of peer problems reduced significantly over the first 6 months. This positive adjustment could be attributed to the LSI, which promotes behaviour modification, peer mediation and perspective taking, which have been found to demonstrate long-term positive effects on adolescent violent and antisocial behaviour (Flood, Reference Flood2010). The LSI approach has been shown to increase positive behaviours, restore relationships and return the student to the classroom without delay (Long et al., Reference Long, Wood and Fecser2001). After peer conflict occurred, each student met with their teacher to conduct separate LSIs. After having their issues validated, solutions to restore the relationship with the other student were discussed and role-played. The process often concluded in both students exchanging gestures and returning to class with new strategies to manage themselves when they are feeling challenged.

The effect size (d = .40) for peer problems adjustment was smaller than the other outcome domains. This is likely a result of the complex behavioural interactions between students. While the approach staff take to working with students is highly strategic and controlled, the behaviours between students is less predictable.

Conduct problems

Conduct problems reduced significantly over the 12-month intervention. This result supports findings from Dorado et al. (Reference Dorado, Martinez, McArthur and Leibovitz2016) and Stokes and Turnbull (Reference Stokes and Turnbull2016) that schoolwide trauma-informed practices can reduce disciplinary issues and improve relationships among peers. As reported by Stokes and Turnbull (Reference Stokes and Turnbull2016), this adjustment may be attributed to the alternative classroom disciplinary and behavioural management processes that are employed in trauma-informed models. Traditional school disciplinary and behavioural management approaches commonly involve short- and long-term suspension (Hymel & Henderson, Reference Hymel and Henderson2006). Research indicates that this approach rarely produces lasting change, increases risk of drop-out, and does not address the underlying causes for the behaviour (Kearney & Albano, Reference Kearney and Albano2004).

Trauma-informed practice models shift from a reactive, consequence-based approach to a proactive approach focusing on preventative measures to clarify expectations and provide opportunities for students to learn new skills to better equip them to handle the problem next time. To promote this approach, the ReLATE intervention used the LSI in response to conduct problems and as a recovery tool each time there was an incident. As demonstrated by Long et al. (Reference Long, Wood and Fecser2001), this approach can reduce conduct problems by role modelling adaptive responses and providing a reflective forum in which students can connect their behaviour to underlying emotions and needs. Through this process, students develop more effective coping skills that could reduce conduct problems that derive from an inability to cope.

In addition to the behaviour support and crisis intervention techniques taught by Therapeutic Crisis Intervention Training, the school implemented a behaviour management process informed by the work of Greene (Reference Greene2011) that is underpinned by the following perspectives: (1) kids do well if they can; (2) doing well is preferable to not doing well; (3) behind every challenging behaviour is a lagging skill that can be developed; (4) problems should be solved collaboratively with the student; and (5) empathic consideration should be given to how past experiences of trauma have influenced the behaviour.

The reduction in conduct problems could be attributed to both the new coping skills taught through the LSI, as well as the behavioural philosophy adopted by staff. A parent expressed that the improvement in her son’s behaviour was attributed to the acceptance of his barriers and the schools acceptance that he will need support to meet behavioural expectations. This parent also spoke about the willingness to embrace challenges and contrasted this to a previous school who isolated the student to prevent behavioural problems.

While the initial training and professional development for staff is necessary to embed understanding and skills, the staff also witness best-practice incident responses from members of the school leadership team, which included principals, the wellbeing coordinator and school psychologist. Incidents are discussed from a trauma-informed lens in a debrief process that also discusses the challenges and strengths of staff responding to the escalations. Additionally, the psychologist at the school provided multiple refresher training sessions throughout the year aimed at coaching and skill building.

Total difficulties and impact adjustment

The meaningful and statistically significant reduction in total difficulties and global impact is a noteworthy finding given that many of the students that made up Sample 1 had come from schools that reported they had exhausted all possibilities. Many of the students had multiple external professionals involved from a young age to remediate the difficulties associated with their disorders. Further, the fact they were withdrawn from mainstream settings and enrolled at a specialist school likely signifies their symptoms were increasing in severity prior to the enrolment. Given the data was captured from parent-reported observations of their child, the results from global impact reduction signify that the benefits from school-based, trauma-informed intervention models are not just observed within the school environment and may generalise to other aspects of life, including the student’s friendships, learning and family life.

Comparison with international models

The ReLATE intervention differs to other trauma-informed models that have been evaluated internationally. Many U.S. models provide intervention through clinician-led manualised programs, such as Cognitive Behavioural Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS), Bounce Back Resiliency Program and Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TF-CBT) (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti2017; Hansel et al., Reference Hansel, Osofsky, Osofsky, Costa, Kronenberg and Selby2010; Perry & Daniels, Reference Perry and Daniels2016); whereas the ReLATE model aligns more closely with the Australian Berry Street Education Model (BSEM), which uses a wide variety of teacher-led, classroom-based strategies and activities to increase self-regulatory abilities and improve students psychological coping. Another similarity with the BSEM is the implicit teaching and training that occurs throughout implementation. However, unlike the BSEM, which has been evaluated in large mainstream schools, the ReLATE model has thus far only been evaluated in a small specialist school. In their evaluation of BSEM, Stokes and Turnbull (Reference Stokes and Turnbull2016) reported that a key challenge was embedding the model schoolwide across all year levels, rather than specific sectors of the school. Schoolwide consistent practice was a strength of the ReLATE intervention.

Limitations

ReLATE was not implemented as a standardised protocol that can be replicated with other experimental design studies. Rather, it is an intervention developed to be flexible by using a variety of evidence-based components. As a result, this study has several limitations.

First, it is possible the small sample size, which has been predominantly discussed (n = 8), had a negative impact on the statistical power in the ANOVAs. However, this was corrected for through the use of the RCI. This approach excels with small sample sizes due to the ability to track individual change, and can be applied with very specific client populations that are difficult to recruit (Zahra & Hedge, Reference Zahra and Hedge2010). Another limitation of the sample was the disproportionate number of males. Trauma exposure impacts females functioning differently and results in different service needs (Postlethwait et al., Reference Postlethwait, Barth and Guo2010). A gender-balanced sample would reveal whether the ReLATE intervention addressed both male and female needs equally. However, a recent study of trauma-informed teaching with a female population reported significant symptom improvement through practices shared with ReLATE, such as staff training, de-esclation strategies and a nontraditional disciplinary approach (Crosby et al., Reference Crosby, Day, Baroni and Somers2019).

The study design would have been improved through the inclusion of a waitlist control group for comparison. The school uses a waitlist system; however, this was unable to be utilised at the time of data collection. Without this comparison group, it is difficult to separate out external environmental factors such as adjustment in parenting approaches or changes in environmental conditions that are known to influence the difficulties described (Loeber et al., Reference Loeber, Burke, Lahey, Winters and Zera2000).

Implications

The findings from the study support the efficacy of specialist withdrawal settings. Further, for students who need to access these settings, results from this study indicate that to gain full social-emotional benefits, students may need to attend for at least a year.

While it may have been predicted that trauma-affected students would respond best to this intervention, findings indicated that students with other clinical disorders — for example, ADHD, oppositional defiance disorder (ODD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and anxiety — all benefitted equally. This result highlights the need for further studies to corroborate the finding that a wide range of students benefit from trauma-informed intervention models. Given these results occurred within a specialist school setting that has atypical classroom arrangements — such as a ratio of eight students to two adults — the generalisability of these findings to mainstream schools and classrooms is limited.

Finally, an emphasis on the role school psychologists can play in implementing trauma-informed practice models is evident from the findings. Psychologists are trained to be expert consultants, evaluators, behaviour analysts and trainers. Further, their interpersonal skills lend themselves to role modelling coregulation practices that reduce student aggression.

Conclusion

School-based trauma-informed practice models provide a promising solution to the various emotional and behavioural challenges displayed by students with clinical disorders and who have experienced trauma. This study demonstrated that over 12 months, a schoolwide trauma-informed intervention model led to a range of emotional and behavioural benefits with moderate to large effect sizes. Findings are attributed to classroom environments that emphasise safety and practicability, clear incident response and debriefing processes, reflective practices for student recovery, and regular and ongoing staff training to preserve trauma-informed perspectives.

Acknowledgments

Dr Shane Costello for his guidance in refining the scope of the study and editorial comments; Justin Roberts for his insights into the findings.

Conflicts of interest

MacKillop Education is the employer of the author.

Ethical standards

The author asserts that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The author asserts that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guides on the care and use of laboratory animals.