Introduction

It has been oft-noted that the widespread interest in subsidiarity is not surprising. As a core constitutional principle of the EU legal order, subsidiarity stands at the crossroads of questions about the ends and means of European integration through law.Footnote 1 The academic debate so far has predominantly concentrated on explaining the institutional adaptation of member states and EU institutions to the subsidiarity scrutiny. This focus needs to be complemented by presenting not only the mechanism for national parliaments’ activities,Footnote 2 but the content of their contribution in this domain as well.Footnote 3 Furthermore, since the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, the Early Warning Mechanism has been primarily regarded as a tool of collective action on the part of national parliaments in issuing reasoned opinions,Footnote 4 while the input of legislative chambers as individual actors seems to have been insufficiently taken into consideration.Footnote 5

The participation of national parliaments in the Early Warning Mechanism is underpinned by and conditioned on diverse factors: their institutional capacity;Footnote 6 political or policy motivations;Footnote 7 internalFootnote 8 and internationalFootnote 9 conditions; and finally the grounds for declaring the non-compliance of draft legislative acts with the principle of subsidiarity. Leaving aside the question of the circumstances in which national parliaments have decided to deliver a reasoned opinion in each particular case, this article aims to present and classify the reasons (arguments) given in these opinions.Footnote 10 To do this, an empirical review of all reasoned opinions issued in the last five years has been performed.Footnote 11 This review reveals that national parliaments’ involvement in the Early Warning Mechanism covers a variety of topics, extending beyond the mere scrutiny of subsidiarity, and that individual voices of national parliaments are meaningful even without reaching the threshold for a ‘yellow card’. This leads to the conclusion that the underestimated significance of the Early Warning Mechanism lies in its giving the floor to each national parliament, and it cannot be boiled down to the triggering of the ‘cards’ procedure. What is also important is that this view is firmly based on Article 7(1) of Protocol No. 2, according to which the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission are obliged to take into account the reasoned opinions issued by national parliaments or by a chamber of a national parliament. In other words, within the Early Warning Mechanism national parliaments can ‘sing’ not only in a choir, but also as soloists.

Additionally, this article may serve as a springboard for more developed research regarding the role of national parliaments in shaping the EU legal order, as well as on the approach of the Commission to the Early Warning Mechanism.Footnote 12

The EU dimension of the principle of subsidiarity

The concept of subsidiarity has long roots and has been used by both politicians and political theorists.Footnote 13 However, the view expressed 25 years ago that ‘subsidiarity is a fashionable idea today, although its meaning remains unclear’Footnote 14 remains pertinent. In the broad sense, we define subsidiarity as a principle organising the relations between groups, in its essence defining the structures of both the state and society.Footnote 15 More precisely, the principle of subsidiarity regulates the allocation or use of authority within a political or legal order, typically in those orders that disperse authority between a centre and various member units.Footnote 16 At its heart, subsidiarity remains a principle about how state and society should be structured. While its precise content and implications in a range of contexts can be rather vague and are often contested, at its core the principle requires higher levels to aid lower levels rather than to obliterate or subsume them.Footnote 17 In other words, subsidiarity is typically understood as a presumption in favour of lower level decision-making, and one which allows for the centralisation of powers only for particularly good reasons.Footnote 18 Because of the confusion surrounding its meaning, there is a rather hapless consensus that subsidiarity is about allocating decision-making authority between ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ levels on the basis of technical criteria, as if subsidiarity itself is indifferent to where that authority should lie.Footnote 19

The distribution of powers between ‘Brussels’ and the member states has been one of the most contentious points throughout the history of the European integration project. Since the initial years of the European Economic Community, member states have resisted the expansion of activities and the progressive centralisation of competences at the Community level. Although the original intention was that the Community could obtain a transfer of competences from member states to itself only on the basis of the member states’ authorisation, in practice the real location of competences was determined on a political basis via a broad interpretation of the Treaties.Footnote 20 The resistance of member states to legislative centralisation grew stronger after the Single European Act, which strengthened the powers of Community institutions and opened up new fields of their activity.Footnote 21 In the process of consolidation of the Union as a self-standing political organisation, the question inevitably arose as to the role of member states. In this context, the principle of subsidiarity serves to explain why certain competences should be a matter of national concern and others a matter of concern for the Union.Footnote 22 With the Treaty of Maastricht, the principle of subsidiarity explicitly found its way into a constitutional text (the TEU),Footnote 23 and since that time it has served as a corrective tool for deficiencies in the allocation of competences.Footnote 24

The principle of subsidiarity as laid out later in the Treaty of Lisbon holds that in areas which do not fall within the EU’s exclusive competence, the member states should decide, unless central action will ensure a higher comparative effectiveness in achieving the specified objective(s).Footnote 25 The principle of subsidiarity was introduced into the EU legal order to counter the expansion of the powers of the EU, and it supports the citizens’ desire for decision-making on a more decentralised level.Footnote 26 To put it differently, this principle is meant to protect the autonomy of member states and of the sub-national authorities from unnecessary Union actions.Footnote 27 Consequently, the principle of subsidiarity has been mostly read as a ‘competence valve’, determining whether the EU or member states should exercise competence over a particular issue. At the same time, it also bears an extraordinary potential with regard to preserving the constitutional identities of the member states.Footnote 28

Within the EU, the principle of subsidiarity is recognised as a general principle of EU law,Footnote 29 or even as ‘one of the key constitutional principles that serve to set the character of the EU’.Footnote 30 It has been postulated that it would reduce ‘the democratic deficit’Footnote 31 and allow decisions to be taken ‘as close to the citizen as possible’.Footnote 32 However, there has also been some criticism as regards the principle of subsidiarity in the EU legal order. According to some authors, it does not fully accord with the specificity of the EU.Footnote 33 In the most extreme view the principle is considered as totally alien to and in contradiction to the logic, structure, and wording of the Treaties.Footnote 34

In my estimation, the most characteristic feature of the EU’s recognition of the principle of subsidiarity is that its impact is limited to the level of member states. The preamble to the TEU provides that in ‘the process of creating an ever closer union’… ‘decisions are taken as closely as possible to the citizen in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity’. While this suggests that the general concept of subsidiarity requires that decision-making is situated at the lowest possible level, the reality of the way the EU functions results in the ‘subsidiarity game’ being played out just between the EU and member states. To put it another way, with the help of subsidiarity in its EU dimension we can ensure that decisions are taken more closely to the citizen, but the final choice on just how close lies within the member states’ competences.Footnote 35 Paradoxically, the failure to fulfil the promise of proximity as an element of the principle of subsidiarityFootnote 36 is not the worst case scenario, taking into account that the attempts to interfere in the internal policy of member states via EU law are strongly (though not always justifiably) opposed by national parliaments.Footnote 37

National parliaments as watchdogs of the principle of subsidiarity

Since it was generally believed that subsidiarity was necessary for the EU’s democratic legitimacy, when it comes to its application it seemed right to entrust the role of watchdog to national parliaments.Footnote 38 The need to more closely involve national parliaments in EU actions was a corollary idea that has received increasing support since the Treaty of Maastricht, especially as a compensation for the loss of some of their legislative powers.Footnote 39 Thus national parliaments were brought into the process of scrutiny because they have an institutional interest in restraining EU actions that might encroach upon their own spheres of activity.Footnote 40 Furthermore, national parliaments provide a major space for public debate and were perceived to be the ideal forums for deliberations over important European issues and their domestic implications, as well as being capable of effectively contributing to making EU policy processes more transparent.Footnote 41 Nonetheless, some commentators have questioned whether a system which attributes the role of primary guardian to national parliaments is the best solution.Footnote 42 Likewise, it has been pointed out that MPs have their hands full even without engaging in EU affairs, so the in-depth scrutiny of European proposals may not be very attractive to them.Footnote 43

The Early Warning Mechanism, introduced by the Treaty of Lisbon, charged national parliaments with monitoring the compliance of draft EU legislative acts with the principle of subsidiarity in areas which do not fall within the EU’s exclusive competence.Footnote 44 As Cooper observed, national parliaments were previously seen as institutions that enjoyed democratic legitimacy but had little or no collective influence in EU politics.Footnote 45 The Early Warning Mechanism appeared as a compromise solution because its merits were dual in nature: offering a technical response to the question of subsidiarity control; and increasing the role of national parliaments without further complicating the institutional structure and burdening the legislative procedure.Footnote 46

The role of national parliaments in the Early Warning Mechanism has been the subject of both academic and policy debates.Footnote 47 One question of great importance concerns the scope of their scrutiny: should national parliaments only review at what level (national or EU) the legislative measure should be taken, or should they also consider the principle of proportionality, whether the correct legal basis is applied, and the substance of the proposal? There is no consensus, either among national parliaments or among scholars, concerning this multi-pronged question.Footnote 48 A narrow reading of the Early Warning Mechanism, as promoted by Fabbrini and Granat, would state that it should be limited to the material and procedural dimensions of subsidiarity review. Consequently, this mechanism should not address the content of a legislative draft, its proportionality, or the correctness of its legal basis.Footnote 49 According to this formalist interpretation, the subsidiarity review revolves more around checking whether the Commission proposal ticks all the right procedural boxes rather than engaging in a political evaluation of the principle of subsidiarity.Footnote 50 In contrast, other authors take as their starting point the member states’ perspective on the scope of the scrutiny of subsidiarity. Goldoni offers a bottom-up approach to the purpose of the Early Warning Mechanism, with its main purpose being to safeguard a representative political space on the national level and national constitutional identities.Footnote 51 Jančić advocates for a broad scope of the review, including an evaluation of the principle of conferral and the substance of the legislative proposal, and argues that by so doing the legitimacy of the EU legislative process could be improved and the democratic deficit alleviated.Footnote 52 Likewise, Kiiver suggests that subsidiarity should be understood broadly, even if it means a certain overlap with other criteria that national parliaments find relevant to the subsidiarity review, namely competence and proportionality.Footnote 53

In view of all the above considerations I would opt for a moderate, pragmatic approach, assuming that although the subsidiarity scrutiny should be based on Article 5(3) TEU, its wider understanding may bring about positive ‘side effects’.Footnote 54 As has been rightly asserted, national parliaments are obviously bound to observe the EU Treaties but – as political organs – remain free to interpret them differently.Footnote 55 If one perceives the Early Warning Mechanism to be open to a variety of purposes, it seems to be particularly inclusive in terms of raising concerns over member states’ national identities within the meaning of Article 4(2) TEU.Footnote 56 This connection between the concepts of subsidiarity and respect for national identities has already been noted by commentators as well as national parliaments.Footnote 57

Reasoned opinions (2014–2019) – state of play

Since 1 December 2009 national parliaments have issued 479 reasoned opinions. This is too a high number to be profoundly discussed in a single article, hence the following review puts the spotlight on the second half of this 10-year period; i.e. it covers the reasoned opinions submitted between November 2014 and October 2019.Footnote 58 To start with, some statistics relating to these reasoned opinions are presented in order to demonstrate the scope, the structure, and main actors within the Early Warning Mechanism, also against the background of the previous five years of its functioning (between 1 December 2009 and October 2014), which should be helpful in observing the dynamics of using this tool. This is followed by introductory remarks on the content of the reasoned opinions, and is subsequently developed later in the text.

During the reference period, national parliaments delivered 185 reasoned opinions on 78 draft legislative acts, while in the years 2009–2014 there were 294 reasoned opinions on 115 draft legislative acts. This means that in the second period reasoned opinions concerned 19.5% of all draft legislative acts, while in the first period the level was about 23.5%.Footnote 59 In addition, by comparing the number of reasoned opinions delivered in last five years with the maximum number of reasoned opinions which could have been issued within the same period, we obtain a result of 0.5%,Footnote 60 which can be called the actual ‘participation factor’ in the Early Warning Mechanism. Obviously this does not mean that in the remaining 99.5% of cases national parliaments tacitly accepted the compliance of the draft legislative acts with the principle of subsidiarity, as their silence could have been the result of various factors.Footnote 61

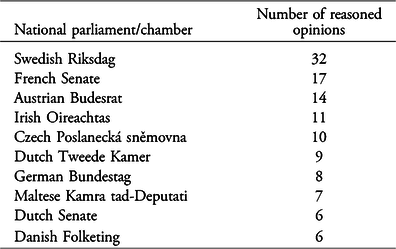

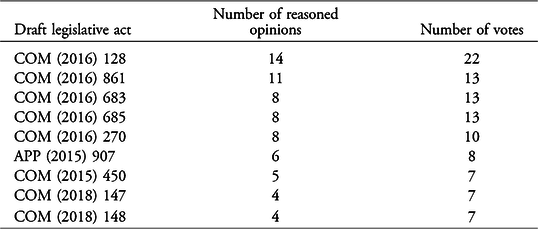

It should be noted that there were large disparities among national parliaments in terms of their activity in the Early Warning Mechanism, with the Swedish Riksdag (32 reasoned opinions) at the top of the list, while six national parliamentary chambers (in five countries) did not submit any reasoned opinions at all.Footnote 62 During the first period the Riksdag was also the leader, and the rest of the chambers demonstrated varied degrees of commitment to this mechanism.Footnote 63 It should be stressed that in the most recent five years the ‘yellow card’ procedure was launched only once,Footnote 64 when 14 chambers (equal to 22 votes) submitted reasoned opinions on the draft directive on the posting of workers within the framework of the provision of services.Footnote 65 By comparison, in the first five-year period two ‘yellow cards’ were triggered.Footnote 66

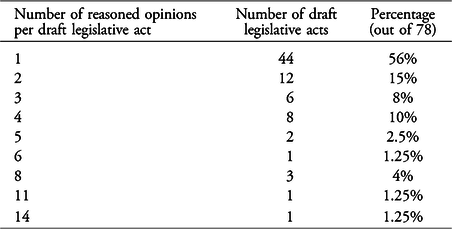

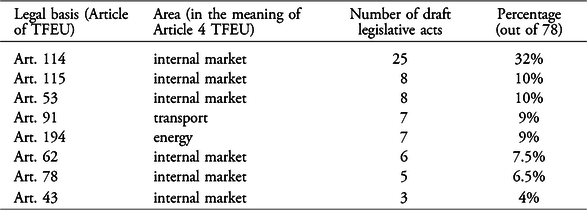

With regard to the distribution of reasoned opinions, the most striking fact is that 44 out of 78 scrutinised draft legislative acts (56%) were the subject of a single reasoned opinion. Adding to this number those cases where two or three reasoned opinions were submitted, it follows that these types of opinions cover around 80% of the whole activity of national parliaments in the Early Warning Mechanism.Footnote 67 Moreover, it is worth mentioning that reasoned opinions predominantly concerned draft legislative acts in the areas related to the internal market, followed by the areas of energy and transport.Footnote 68

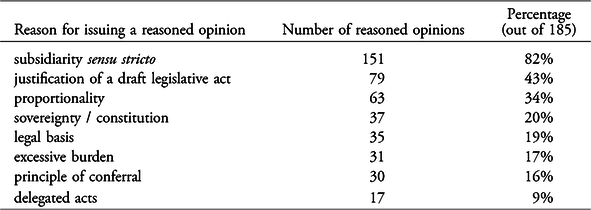

As regards the contents of the reasoned opinions in the most recent five years, it should be stressed that national parliaments gave very diverse reasons for offering their opinions, referring not only to the subject matter of draft legislative acts but also to formal issues.Footnote 69 What is most surprising is that some parliamentary chambers submitted reasoned opinions even when they did not find a clear breach of the principle of subsidiarity. In order to classify the reasons given in the reasoned opinions, we can divide them into five main categories. The first group – the most obvious but intriguingly not encompassing all reasoned opinions – consists of those which indicate a breach of the principle of subsidiarity within the literal meaning of Article 5(3) TEU, although the alleged breaches were grounded on various concerns. Second, reasoned opinions discussing infringements of the principle of conferral should be regarded as a common category. The main factor underpinning this set of reasoned opinions is a strong link between the principles of conferral and subsidiarity, apparent especially in relation to the scope of member states’ competences. Thirdly, diversified arguments with respect to proportionality were presented in a considerable number of reasoned opinions. The fourth category is comprised of reasoned opinions which contained remarks of a legislative nature, pointing out alleged infringement of EU Treaties, even if there is no connection with the principle of subsidiarity. Finally, in numerous cases the shortcomings in the justification of draft legislative acts made the subsidiarity scrutiny more difficult or impossible to carry out, leading national parliaments to the conclusion that Protocol No. 2 had been infringed. Table 5 shows the number of reasoned opinions in which reasons falling within these categories were delivered, with the caveat that most opinions cumulatively invoked arguments of different kinds.

Table 1. number of reasoned opinions per national chambers

Table 2. legislative acts with the most reasoned opinions

Table 3. Reasoned opinions per legislative act (percentage)

Table 4. legal basis for the reasoned opinions

Table 5. reasons for issuing reasoned opinions

The principle of subsidiarity sensu stricto

It is generally acknowledged that the material dimension of the principle of subsidiarity is connected to the two tests delineated in Article 5(3) TEU. First, the ‘national insufficiency test’ indicates that the EU can act only when the member states are unable to achieve a specific EU policy goal. Second, the ‘comparative efficiency test’ indicates that the EU should act only if its action is better able to achieve this goal than that of the member states.Footnote 70 Both tests must be met cumulatively, which implies that even if national action is deemed insufficient to achieve a specific goal, the EU should refrain from acting if the exercise of its powers at the supranational level is unable to attain the prescribed goal better than the states’ actions.Footnote 71 According to the Irish Oireachtas, in consequence two questions must be answered: whether the action by the EU is necessary to achieve the objective of the proposal; and whether the EU action provides greater benefits than an action at the member state level.Footnote 72

Overall, national parliaments delivered arguments relating more or less directly to the principle of subsidiarity within the meaning of Article 5(3) TEU in 151 (out of 185) reasoned opinions. It should be underlined that the reasoned opinions drew attention to various aspects of the principle of subsidiarity, and they differ significantly in terms of the specificity of their justification. Some reasoned opinions were limited to a general statement that the objectives of the planned measures can be ‘better achieved by member states’;Footnote 73 or are ‘satisfactorily achieved by member states and cannot be achieved by the proposed actions of the EU’;Footnote 74 or that ‘the proposal does not concern a subject that could not be resolved by member states’.Footnote 75 At this point it is worth noting that national parliaments sometimes revealed totally different attitudes towards the very same provisions of a given draft legislative act.Footnote 76 In other cases, more in-depth reasoning was provided, usually based on references to provisions of national law and an assessment that the transfer of decision-making powers to the EU level was not needed. Hence it was maintained that, e.g., ‘national practices are inherently better able to take into account the technical, economic and environmental context’;Footnote 77 that ‘the varied practice of member states and their differing political and electoral circumstances suggest that this is a matter best decided at national level’;Footnote 78 and that ‘the current national/regional implementation is sufficient to achieve the objectives’.Footnote 79 Thus, national parliaments are eager to counteract the first test and prove that a member state is capable of achieving a specific goal, which from their perspective may be called a ‘national sufficiency test’. In this context, in assessing the compliance of an EU legislative act with the principle of subsidiarity the fact that a member state can sufficiently achieve an objective is relevant.Footnote 80 In my view, national parliaments cannot compare the efficiency of the EU level with the national level ‘as such’,Footnote 81 because their competence does not encompass the obligation to determine this abstract level. On the contrary, they are authorised to construct reasoned opinions taking into account their national circumstances.

Additionally, it should be highlighted that national parliaments are not very keen on concentrating on the regional and local dimensions of the principle of subsidiarity, although they have incidentally maintained that ‘the Commission did not take into account the regional and local impacts of the proposal’;Footnote 82 or that ‘the objectives can be achieved satisfactorily at the central, regional and local level’.Footnote 83 In this context, it must be mentioned that under Article 6 of Protocol No. 2 it is for each national parliament or its chamber to consult, where appropriate, their regional parliaments with legislative powers. After all, only eight member states have regional parliaments with such powers,Footnote 84 and reasoned opinions delivered by national parliaments very rarely reveal whether regional bodies scrutinised a given draft legislative act.Footnote 85 This rather clearly shows that the real impact of the principle of subsidiarity within the EU is, as a rule, reduced to the level of a member state. As has been rightly maintained, while subsidiarity seemed to bear the promise of recognising local and regional authorities as regulators in EU law, Article 5(3) TEU currently limits this promise to pure rhetoric rather than having an actual substantive effect.Footnote 86

More rarely, national parliaments have performed the ‘comparative efficiency test’. When doing so they have asserted that, e.g., ‘it is doubtful whether the scale or the effects of the proposed actions make them better achievable at the Union level’;Footnote 87 ‘it is unpersuasive that action taken by the EU proposal offers any clear advantages over action taken at a national level by member states’;Footnote 88 or that ‘the proposal does not provide tangible added value, when compared to national legislation’.Footnote 89 Even less frequent were situations when a reasoned opinion combined the results of both tests, indicating that the ‘proposed actions can be taken more effectively at the member state level and there is no sufficient added value in terms of attaining the objectives’.Footnote 90 As the subsidiarity principle is founded on the assumption that the proclaimed aims can be best achieved at the lowest possible level, it seems rather confusing that in a couple of reasoned opinions we find statements discussing the international level as more preferable to the EU level,Footnote 91 which can be called ‘subsidiarity a rebours’. Most of these cases contained allegations that in a given area the OECD provisions are effective and in consequence there was no need to transfer the legislative competence to the EUFootnote 92 or to go further than the OECD provisions.Footnote 93 Similarly, it was indicated that the proposals address global problems (e.g. tax avoidance) which could be resolved more effectively beyond the EU level,Footnote 94 or that due to international law some matters (e.g. civil aviation safety) cannot be transferred to EU institutions.Footnote 95

In addition, several reasoned opinions mentioned the fact that the Commission ‘has not demonstrated that the goal cannot be sufficiently achieved by member states’;Footnote 96 ‘has not provided convincing evidence that the purpose of its action cannot be sufficiently achieved by member states’;Footnote 97 or ‘has failed to provide sufficient evidence that the EU objectives can be better achieved at the Union level’.Footnote 98 Such formulations pose the question whether the national parliaments treated these reasons as substantive arguments, inclining them to issue a reasoned opinion, or rather as a procedural failure, comparable to, for example, the lack of a sufficient justification for the proposal (see below).

What is more, 31 (out of 185) reasoned opinions referred to Article 5 of Protocol No. 2, stating for instance that a breach of the principle of subsidiarity stemmed from the excessive financial or administrative burden imposed on member states,Footnote 99 economic operators,Footnote 100 or citizens. These reasoned opinions also included allegations that the proposal would impose on national authorities ‘an increased administrative burden’,Footnote 101 or ‘considerable additional costs’.Footnote 102 Presumably, national parliaments invoked these statements as auxiliary arguments, strengthening the assessment of non-compliance of the draft legislative act with the principle of subsidiarity.

Principle of conferral – in defence of national sovereignty or national identity?

Article 5(2) TEU provides that under the principle of conferral the Union shall act only within the limits of the competences conferred upon it by the member states in the Treaties to attain the objectives set out therein; and that competences not conferred upon the Union in the Treaties remain with the member states. Whereas the principle of conferral deals with the existence of EU powers to regulate within a particular field, the principle of subsidiarity regulates the exercise of powers shared by the EU and the member states, setting up a functional criteria to decide whether the EU – or rather the member states – should act within a given field.Footnote 103 Some scholars underline the close relationship between the principles of conferral and subsidiarity, and assume that national parliaments should exercise scrutiny over both.Footnote 104 As Goldoni claims, it seems logical to check whether a proposal for a legislative act is compatible with the principle of conferral, since subsidiarity emerges as an issue only when the principle of conferral has been respected.Footnote 105 In contrast, there are voices against the admissibility of such a broad review, primarily on account of the wording of Article 5 TEU and Protocol No. 2, which limit the scrutiny to the principle of subsidiarity.Footnote 106

National parliaments have explicitly invoked the principle of conferral in 30 (out of 185) reasoned opinions. Some of them stressed that the scrutiny of compliance with the principle of subsidiarity should necessarily include an examination of EU competences. The words of the German Bundesrat were particularly strong: ‘Scrutiny of compliance with the principle of subsidiarity necessarily encompasses scrutiny of EU powers and responsibilities in the policy area in question’.Footnote 107 Other reasoned opinions did not directly address the links between the principles of conferral and subsidiarity, but simply stated that in the case of the given proposal a particular area (e.g. taxation policy) or a matter falls outside EU competences. In some instances it is rather difficult to distinguish references to member states’ competences in the context of the principle of conferral from the reasons given why member states could exercise a competence better than the EU. The most common phrases used by national parliaments embraced statements such as that a proposal ‘encroaches upon national competences of member states’;Footnote 108 ‘constitutes a clear restriction of national decision-making powers’;Footnote 109 ‘unnecessarily interferes with the competence of member states’;Footnote 110 or ‘goes beyond the powers (ultra vires) of what is permitted by the Treaties’.Footnote 111 Likewise, the principle of conferral may be implicitly linked to the problem of determining the correct legal basis for a legislative act. To put it another way, the indication of the legal basis is regarded as a positive dimension of this principle.Footnote 112 Such cases may be illustrated by the following wording: ‘the principle of subsidiarity is infringed if the Union possesses no competence; accordingly, the subsidiarity check must examine whether the proposal’s legal basis is such as required for the EU to take action’.Footnote 113

Another subcategory consists of arguments related to the sovereignty of member states (37 out of 185 reasoned opinions), which in many situations appears to be regarded as a synonym for member states’ competences. Hence, these reasoned opinions alleged that the encroachment upon a given regulatory area ‘violates’,Footnote 114 ‘undermines’Footnote 115 or ‘has a direct impact on’Footnote 116 the sovereignty of a member state. It is striking in this regard that the issuance of a reasoned opinion may be built on the allegation that the draft legislative act is incompatible with the member state’s constitution, national legal order, or even just national law. Thus, reasoned opinions encompassed concerns as regards the compliance of a given proposal with the ‘member state’s constitutional law’Footnote 117 or ‘provisions of the member state’s Constitution’.Footnote 118 National parliaments also held that a given proposal ‘unnecessarily encroaches into the legal systems of member states’;Footnote 119 ‘is incompatible with the member state’s system of law’;Footnote 120 or ‘has insufficiently taken into account the legal traditions of the member states and issues relating to the uniformity and consistency of their legal systems’.Footnote 121 Moreover, some reasoned opinions embraced phrases claiming that a proposal ‘represents interference in the member state’s labour market model’;Footnote 122 ‘may violate the budgetary autonomy of member states’;Footnote 123 ‘undermines the member state’s taxation system’;Footnote 124 ‘may have adverse effects on the member state’s economy’;Footnote 125 ‘is a radical encroachment on national enforcement systems’;Footnote 126 or ‘should not interfere with national legal measures that ensure an appropriate level of family protection’.Footnote 127 This shows that many of the substantive arguments endorsed by national parliaments do not aim at protecting national competences vis-à-vis EU competences per se, but instead at protecting or promoting, for example, sectoral economic interests.Footnote 128

At first glance, the above examples may indicate that the principle of the primacy of EU law over national lawFootnote 129 is not necessarily present in the ‘consciousness’ of national parliaments. They seem to ignore the fact that domestic law cannot be invoked as a justification for a breach of EU law.Footnote 130 Nevertheless, it should be noted that the Early Warning Mechanism pertains to draft legislative acts, and thus the signalling of internal constitutional doubts in a reasoned opinion is not equivalent to making the same assertion in relation to binding EU law before the European Court of Justice. Furthermore, it is not surprising that national parliaments have seized the opportunity to use reasoned opinions as a reaction against proposals which infringe upon the essence of member states’ constitutions.Footnote 131

Keeping the above in mind, it can be assumed that a hidden argumentative potential in this regard lies in the concept of member states’ national identities under Article 4(2) TEU.Footnote 132 As has been observed, a possible limitation to the ‘expansive nature’ of the principle of subsidiarity in favour of the EU could come from the interpretation of Article 5(3) TEU, together with Article 4(2) TEU.Footnote 133 It has also been suggested that Article 4(2) TEU endorses the trend to reframe the subsidiarity inquiry from a ‘value-added test’ to a ‘non-encroachment test’, and helps to broaden the scope of this inquiry by connecting the principle of subsidiarity with the principle of conferral and the principle of proportionality.Footnote 134 Arguably, the identity clause – along with the principles of conferral, loyal cooperation, subsidiarity, and proportionality – should be read jointly as setting the boundaries of EU actions.Footnote 135 This may be specifically perceived as a constitutional device to defuse clashes generated by the apparent collision between, on the one hand, the need to ensure the autonomy and the effet utile of EU law, and on the other hand the need to protect the fundamental structures and essential functions of member states.Footnote 136 What is of importance here is that Article 4(2) TEU may be invoked by a national parliament in the context of member state’s national identity,Footnote 137 but not its constitutional identityFootnote 138 or sovereignty. To be precise, in order to decide whether a feature of a particular member state deserves protection under Article 4(2) TEU, this feature must be seen as a part of the constitutional and political structure of the member state in question; must be fundamental to these structures; and must be unique in that no other member state exhibits such a feature.Footnote 139 Applying this logic, the above-cited reasons given by national parliaments are too vague to be approved as a relevant way of utilising the tool provided for under Article 4(2) TEU. However, a proper reference to national identity in a reasoned opinion may serve as a preventive measure to avoid disputes in this matter between national courts and the European Court of Justice.Footnote 140

The various faces of proportionality

Article 5(4) TEU provides that under the principle of proportionality, the content and form of Union action shall not exceed what is necessary to achieve the objectives of the Treaties. The principle of proportionality addresses the intensity of EU action once it has been established that the EU enjoys the power to act.Footnote 141 More precisely, this principle requires that a measure must be appropriate and necessary to achieve its objectives. To determine whether a provision is compatible with the principle of proportionality, it is necessary to verify whether the means it employs to achieve the aim correspond to the importance of the aim (‘a test of suitability’), and whether they are necessary for its achievement (‘a test of necessity’).Footnote 142 The literature highlights the tight connections between the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality, even calling them ‘sister principles’.Footnote 143 Some authors demonstrate the flaws of the existing solution and call for reforming the Early Warning Mechanism to include (at least to a certain extent) a proportionality check,Footnote 144 while others argue for maintaining the exclusion of proportionality from the scrutiny of national parliaments.Footnote 145

National parliaments raised arguments as regards proportionality in 63 (out of 185) reasoned opinions during the period scrutinised. Generally speaking, there were three ways of referring to this matter: (1) as an element of monitoring compliance with the principle of subsidiarity; (2) as a separate principle; and (3) as an additional reason.

The first subcategory is well exemplified by the statement of the Swedish Riksdag, according to which the words ‘only if and in so far as’ in Article 5(3) TEU mean that the subsidiarity check includes a proportionality criterion, and that consequently the proposed action may not go beyond what is necessary to achieve the desired objective(s).Footnote 146

In the second subcategory of reasoned opinions it was emphasised that the principle of subsidiarity is closely related to the principle of proportionality,Footnote 147 but the infringement of the latter is evaluated separately. Certain reasoned opinions merely concentrated on the assessment of the proposal in light of Article 5(4) TEU, which led to conclusions such as ‘the proposal goes beyond what is necessary to achieve the stated objectives and therefore conflicts with the principle of proportionality’;Footnote 148 ‘the proposal is at variance with the principle of proportionality since the measures contained in the proposal are not proportional to the objectives to be achieved’;Footnote 149 and ‘the proposal violates the principle of proportionality because it greatly exceeds what is necessary to achieve the objective pursued by the Commission’.Footnote 150 In one case it was interestingly expressed that Article 5(4) TEU seeks to safeguard member states’ regulatory powers, which implies that the draft act ‘should be adopted in the form that least encroaches on member state autonomy in terms of both its scope and the degree of regulation it involves’.Footnote 151 Moreover, we can identify a category of reasoned opinions which posit that a proposal which goes beyond the extent necessary to achieve the objective violates both the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality.Footnote 152

Finally, reasoned opinions in which proportionality was mentioned without specifying the precise context may be observed. For instance, national parliaments have argued that the proposed provisions are ‘not proportionate to the objectives of the proposal’;Footnote 153 or used phrases based on the issue of proportionality but without naming the principle, e.g. ‘the proposal goes beyond what is necessary to achieve the objective pursued’.Footnote 154

Despite the ambiguity of national parliaments’ usage of the proportionality principle, it seems that their approach, and in particular their reliance on the links between the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality fosters the inclusion of the proportionality test in the scrutiny performed within the Early Warning Mechanism.

National parliaments as ‘legislative advisors’

In numerous reasoned opinions national parliaments pointed out topics which cannot be easily classified into one particular and consistent category. Their common feature is the fact that they are linked to EU Treaty provisions which have a distant, if any, connection with the principle of subsidiarity, and overall they touch on matters of a legislative nature.

All told, 35 (out of 185) reasoned opinions commented on the legal basis of the draft legislative act. Apart from above-mentioned problem of the legal basis as a part of the conferral scrutiny, some reasoned opinions have accentuated that ‘the legal basis is not completely equivalent to the content of the proposal’;Footnote 155 ‘there is a mismatch between the legal basis of the proposal and the aims of the proposed measures’;Footnote 156 ‘the proposal goes beyond the legal basis’;Footnote 157 or ‘the legal basis is not appropriate’.Footnote 158 It seems that in situations wherein national parliaments do not contend that the Union has no competence in a given matter, but claim that an incorrect legal basis has been invoked, the problem lies in infringement of the principle of legality, not the principle of conferral.

Sporadically, national parliaments have indicated that draft legislative acts breach other Treaty provisions of a material nature in a specific area, by declaring that, e.g., the proposal ‘would violate the principle of “equal pay for equal work” as laid down in Article 157 TFEU’;Footnote 159 ‘interferes with member states’ responsibility for medical care and management of health services provided for in Article 168(7) TFEU’;Footnote 160 ‘gives rise to concerns in terms of its compatibility with the principle of democracy, which is included among the fundamental values of the EU pursuant to Article 2 TEU’;Footnote 161 ‘is not compatible with the principle of subsidiarity with regard to the Treaty right of member states to freely shape their own energy mix, technological neutrality and sovereign national energy (Article 194(2) TFEU)’;Footnote 162 or ‘clashes with the spirit and purpose of Article 78 TFEU and the European policy aimed at supporting the action of member states facing immigration pressure at their borders’.Footnote 163 Besides, national parliaments several times adopted positions in defence of the common market, arguing that a given proposal may contravene its principles or the objectives of its functioning.Footnote 164

In 17 (out of 185) reasoned opinions national parliaments raised concerns over the empowerment of the Commission to adopt delegated acts. In a few cases they simply took the view that Article 290 TFEUFootnote 165 has been breached because ‘the proposed scope and extent of delegated acts significantly exceed the mandate issued in Article 290 TFEU’;Footnote 166 or the ‘powers delegated to the Commission go beyond the limits laid down in Article 290 TFEU’.Footnote 167 Other national parliaments observed that an excessive use of delegated acts can violate the principle of subsidiarity because they do not have the power to adopt reasoned opinions with regard to ‘draft delegated acts’.Footnote 168 Furthermore, national parliaments have occasionally criticised provisions conferring implementing powers on the Commission. These reservations have generally relied on the fact that implementing acts are not submitted to the subsidiarity scrutiny.Footnote 169

Last but not least, national parliaments have relatively often expressed a negative assessment of draft legislative acts, but without a clear indication how their assessment was associated with a breach of the principle of subsidiarity. For example, they contended that given proposals seem to be unnecessary,Footnote 170 unclear,Footnote 171 or harmful to the member state.Footnote 172

All the above examples demonstrate that national parliaments are willing to improve the quality of EU provisions, in both their material and formal dimensions. While this is not the place to analyse whether their input in this regard is of a significant value, nevertheless pragmatically speaking there is no cause for not benefiting from their expertise in the field of legislation.Footnote 173

Insufficient justification of draft legislative acts

Under Article 5 of Protocol No. 2, any draft legislative act should contain a detailed statement making it possible to appraise its compliance with the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality.Footnote 174 While in the legal doctrine the correct justification – in the context of national parliaments’ prerogatives in the Early Warning Mechanism – is mainly seen as a point of reference for assessing compliance with the principle of subsidiarity,Footnote 175 shortcomings in the justification as such are generally not considered to give rise to a need to adopt a reasoned opinion.Footnote 176 Nevertheless, Kiiver argues that an inadequate justification in itself constitutes a breach of the subsidiarity principle because there are formal obligations on the part of the Commission to justify a draft.Footnote 177

Reasons regarding the justification of proposals were given in 79 (out of 185) reasoned opinions. National parliaments stated, e.g., that ‘the Commission failed to fulfil its obligations to inform and duly justify the proposal with regards to its compliance with the principle of subsidiarity’.Footnote 178 Many reasoned opinions specified that the lack of a justification which meets the requirements set out in Article 5 of Protocol No. 2 made it difficult or even impossible to assess the compliance of a proposal with the principle of subsidiarity,Footnote 179 or with the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality.Footnote 180 As a consequence, such a lack ‘undermines national parliaments’ right to objections, which in the long term would weaken the democratic decision-making processes in the EU’.Footnote 181 It was also observed that shortcomings in the justification of a draft act may breach the principle of sincere cooperation of Article 4(3) TEU,Footnote 182 and may constitute grounds for judicial review under EU law.Footnote 183

Several reasoned opinions presented more nuanced reservations as regards the content of the justification, e.g. by claiming that ‘the Commission has not adequately met the procedural requirements to provide a detailed statement with sufficient quantitative and qualitative indicators’.Footnote 184 In other cases, national parliaments argued that the Commission did not carry out an impact assessment of the proposed legislation,Footnote 185 or that the assessment was founded on unrealistic assumptions.Footnote 186 Furthermore, in a couple of reasoned opinions national parliaments criticised the lack of consultations or their insufficiency.Footnote 187 The most frequently cited reason for reservations was the breach of Article 2 of Protocol No. 2, according to which the Commission shall conduct a broad consultation before proposing a legislative act.Footnote 188 In this context it is worth noting that according to some experts, the failure to conduct broad consultations may justify an allegation of infringement of the procedural requirements of Protocol No. 2, although it is not sufficient to simply maintain that the results of consultations were unsatisfactory.Footnote 189

To sum up, strictly speaking flaws in the justification of a draft legislative act are not sufficient to constitute the sole reason to deliver a reasoned opinion. That said, it must be added that the expectations of national parliaments regarding the accuracy of such justifications have solid grounds under, inter alia, Article 4(3) TEU. Besides, the high number of reasoned opinions discussing deficiencies in justifications of legislative proposals indicates that the declarations of the Commission as to its commitment to duly act in this regard have not yet been fulfilled.Footnote 190

Conclusions

Pursuant to Article 6 of Protocol No. 2, a reasoned opinion issued by a national parliament must state why it considers that the proposal in question does not comply with the principle of subsidiarity. The above empirical review demonstrates that national parliaments’ reasoned opinions rely on diverse reasons, sometimes only slightly connected to the meaning of this principle under Article 5(3) TEU. To my mind, each reasoned opinion should provide at least one reason indicating a direct breach of the principle of subsidiarity sensu stricto, which anchors such opinion in the Early Warning Mechanism. Consequently, so long as the EU Treaties are not amended it is insufficient to construct reasoned opinions solely on the grounds of an alleged infringement of the principles of conferral or proportionality. This does not diminish the value of addressing problems related to these principles or other topics in reasoned opinions, since it may trigger a fruitful discussion during the course of the legislative procedure.Footnote 191 Despite the fact that a variety of these topics, including remarks on the merits of the draft legislative acts, are also brought up within the framework of the political dialogue,Footnote 192 it should be emphasised that the Early Warning Mechanism, which is established in the Treaty, still has an advantage over the Barroso initiative, the informality of which allows the Commission to abolish it on any occasion.Footnote 193

In this field, one should particularly take into account the potential contributions of national parliaments as regards matters of a constitutional and/or legislative nature. First, this concerns the concept of national identity, since parliaments can here play a substantial role as bodies regularly engaged in operating in constitutionally sensitive areas. In this context it should be highlighted that so far reasoned opinions have been principally focused on problems considered as significant from the individual perspective of a member state. This practice is understandable, because the issues of sovereignty, constitutional law, or national competences are far more deeply inscribed in the modus operandi of national legislatures than dealing with the nuances of a pan-European overview. Insofar as this attitude does not obscure the core of the principle of subsidiarity, it should be accepted, unless we wish national parliaments to retreat from the Early Warning Mechanism. In practice, this mechanism consists of a sum of individual arguments based on internal (national) premises, not a common view of national parliaments on a given problem.Footnote 194 Thus, it seems naïve to believe that national parliaments will function as ‘objective’ scrutinisers which compare the effectiveness of the EU with that of member states ‘as such’. That said, it has to be underlined that reasoned opinions are not designed to cover any and all constitutional concerns on the part of a member state, but only those which can be meaningfully voiced on the basis of the national identity clause found in Article 4(2) TEU. Additionally, inasmuch as national parliaments are willing to share their concerns over matters like the (in)adequacy of a legal basis or the legislative quality of a proposal, their concerns should not be disregarded. Since legislating is at the core of national parliaments’ domestic competence, their scrutiny over EU draft legislative acts may ‘accidently on purpose’ bring positive effects with respect to the quality of EU law.

In addition, we should stop perceiving the Early Warning Mechanism solely through the prism of whether the threshold has been reached that allows ‘cards’ to be triggered. If the significance of the Early Warning Mechanism were limited to issuing a yellow card, this would mean that in the last five years the voice of national parliaments mattered only in one out of nearly 400 draft legislative acts delivered to them. According to the statistics, in most cases draft legislative acts are subject to reasoned opinions submitted by up to three chambers, although, as has been described above, even in these situations national parliaments may contribute to adopting better EU laws. Since the collective feature of the Early Warning Mechanism is emphasised,Footnote 195 every so often proposals are submitted to strengthen the cooperation between national parliaments, as well as to amend the procedure for delivering their reasoned opinions. In my view, these issues are not of primary importance, since under the current legal framework there are no procedural obstacles which hinder national parliaments from participating in the Early Warning Mechanism. At the same time, some national parliaments simply do not appear to be interested in becoming significantly involved in EU matters.Footnote 196 Hence voices in favour of reforming the procedural dimension of the Early Warning Mechanism would seem to be a ‘forward escape strategy’ and are not promising with respect to strengthening the overall involvement of national parliaments.

To conclude, no matter how serious the criticism is over the outstretched interpretation of the principle of subsidiarity, it is national parliaments’ right to give reasons via their reasoned opinions. Thus, instead of rebuking the parliamentarians for not acting strictly in line with the letter of the Treaty, a more benevolent attitude should be adopted so as not to miss the chance to profit from the expertise of each chamber. In other words, in the case of the Early Warning Mechanism the safety should not be not in numbers, but in the value of the input provided individually by national parliaments. This could be profitable for the functioning of the EU – being a legal as well as political project – in the delicate area of striking a balance between acting on the level of the Union and/or on the level of its member states.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1574019620000048