Introduction

Higher education and academic research are of major importance to today’s knowledge society. More than ever, they are the result of a collective endeavour undertaken especially by their professional representatives. In European universities, the need for collective action is most visible in coordinated study paths as a result of Bologna reforms, as well as in the rise in externally funded collaborative research programmes. This development has been spurred by an increasing competition for scarce financial resources. Competition makes, first, the exploitation of scale and scope effects necessary.Reference Boardman and Corley 1 – Reference Gumport 3 They can be realized, for example, by bundling activities in shared services. Second, competition for scarce financial resources often requires thematic prioritization, thus a specific positioning against other educational and research institutions.Reference Beerkens and Derwende 4 , Reference Teichler 5 A current example is the acquisition of clusters of excellence within the Excellence Initiative of the German federation and the federal states. In this context, the positive reputation of such lighthouse projects is expected to be mirrored in other areas.

We take the increasing collaborative nature of activities in higher education institutions as a starting point and argue that governing collective action effectively is one of the most important challenges for modern universities. However, this is by no means self-evident. After all, universities for a long time have been considered the archetype of loosely coupled systems with multiple and pluralistic goal systems. In their famous quote, Mintzberg and Rose characterized universities as ‘set[s] of activities held together by common parking lots’,Reference Mintzberg and Rose 6 because the single, quite autonomous researcher and his or her creativity, effort, and tenacity were sufficient for the success of universities. Today, however, no one would probably deny that a university is more than just the sum of individual research or teaching achievements of its members. Scholars need to engage more in collaborative activities which have to be coordinated through different modes of governance. Achieving collective action calls for ‘tightening up’ loosely coupled structures by shared norms and rules, forms of peer control, and joint decision-making. Such modes of governance are as such neither good nor bad; what matters is that they fuel the mutual interactions between interdependent actors.

In general, collective action is defined as the pursuit of a goal by more than one actor.Reference Olson 7 – Reference Sandler 9 Collective action is concerned with the provision and consumption of public goods through the collaboration between these actors. Based on this idea, we enrich current research on university governance, because, so far, higher education research has not really taken into account that bundles of collective resources very often display the features of quintessential public goods: non-rivalry and non-excludability.Reference Samuelson 10 – Reference Drahos 12 We apply research on public goods, collective action, and the resource-based perspective to universities. According to the concept of corporate commons, developed by Frost and Morner to analyse collective action in multidivisional firms,Reference Frost and Morner 13 , Reference Frost and Morner 14 we call these resources university commons. With this in mind, the aim of this article is twofold: first, we aim to develop the concept of university commons in order to analyse governance challenges arising from tightening up virtually autonomous, loosely coupled ‘parts’ into a coherent whole. Second, we examine how to balance collegial and managerial governance to effectively create a university-specific portfolio of university commons. Governance modes have to be applied selectively, depending on the field of action. The overall configuration of collegial and managerial modes comprises a system of checks and balances that facilitates collective action and thus provides different university commons according to their public-good characteristics.

This article is structured as follows: in the next section, we consider briefly why achieving collective action is one of the main governance challenges for pluralistic organizations such as universities. After that, we elaborate the meaning of collective resources necessary for achieving collective action and introduce a typology of university commons. We explain that different kinds of university commons create different resource dilemmas about creating, sharing, or using collective resources. To resolve or even avoid such dilemmas and to govern these commons successfully, we propose specific combinations of different governance modes. We present this ‘strategy of coexistence’ in the following section. It requires an integrative framework that allows for a customized combination of collegial and managerial governance. Concluding remarks follow in the final section.

Collective Action in Universities: Introducing University Commons

Governing collective action is one of the most important governance challenges for modern universities. Fragmented collectives and multiple stakeholders that pursue different objectives constitute the institutional autonomy of universities and are all linked within fluid and ambiguous power relationships.Reference Denis, Langley and Rouleau 15 Such pluralistic organizations are characterized by great degrees of individual autonomy. Their members often feel more committed to their profession than to their employing organization.Reference Weiherl and Frost 16 In order to stimulate collective action, one should take into account that the structure of interdependent actions provides cohesion of future interactions by defining the mutual conditions of collective action. Thus, collective action calls for ‘tightening up’ loosely coupled structures by shared norms and rules, forms of peer control, and joint decision-making. This is also true for universities that need to be more than just the sum of their parts. Dieter Imboden, who served as head of the expert commission evaluating the German Excellence Initiative, has expressed concisely why a university should be more than just the sum of its parts.

Because, first, doing good research is—today more than ever—the result of cooperation. And second, today’s academic system has grown so much that even the wealthiest university will not be able to avoid setting a strategic course, specifically, deciding for or against policy options for the future. To get things right, the ‘parts’ require rules on collective action. Reference Imboden 17

Since the publication of Olson’s famous book on the logic of collective action in 1965, collective action cannot be considered without the recognition of the role of public goods.Reference Olson 7 There is also empirical evidence supporting the idea that the construct of public goods represents knowledge resources of organizations.Reference Cabrera and Cabrera 18 Frost and Morner have applied this research to multidivisional organizations and developed a typology of corporate commons.Reference Frost and Morner 14 Transferring their research to the higher education setting, we call such common resources university commons and follow the argument congruently: without university commons there would be no organizational or strategic reason why universities should not break up into small, separate, independent parts. University commons provide the strategic basis for pursuing certain activities and producing certain resources in the first place; for coordinating, i.e. governing these activities under the umbrella of one organization. Thus, each university identifies its specific portfolio of university commons according to their strategy.

University commons are collective resources that are of benefit to all university members regardless of whether they have contributed to the creation of resources or not. Just as public goods cannot be provided without the cooperation of members of the society, university commons cannot be produced without collective action or specified rules for consumption that are valid for all members of the organization. Thus, such commons are subject to social dilemma situations and the free-rider problem: organization members may refuse to pay for the creation and use of the commons even if they value these resources very highly. Providing and consuming these resources can be considered a special case of externalities.Reference Cornes and Sandler 11 The danger of a managerial or social dilemma is imminent.Reference Miller 19 In this case, collective action cannot be achieved without the right governance modes, because individual rationality does not result in collective rationality.Reference Dawes 20 – Reference Messick and McClelland 23 The reason for this lies in the defining characteristics of public goods.

Based on the earlier work of Samuelson, the distinction between public and private goods is based on two characteristics: non-rivalrous consumption and non-excludability.Reference Samuelson 10 If there is non-rivalry, consumption by one actor does not reduce the quantity consumed by anyone else. The consumption opportunities for others are still available. The benefits of such goods are indivisible, because what one actor uses can also be used by others. If there is non-excludability, it is either impossible or prohibitively expensive to limit the benefits of the good or resource to one specific actor. In this case, the actor can benefit from the production of a public good regardless of whether he or she contributes to it, pays for it, or is engaged in the production process, or not. The degree of excludability describes the extent to which an actor has exclusive control over a good.

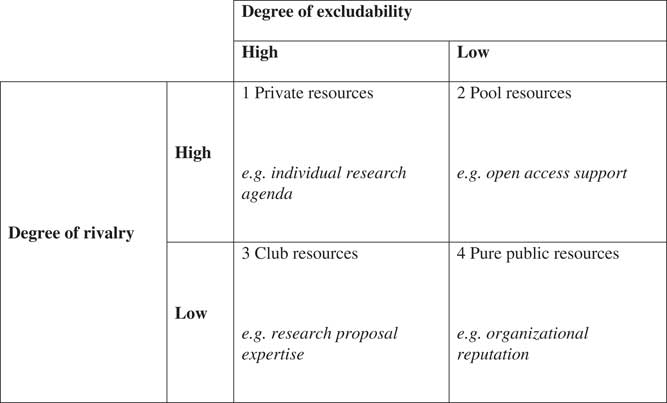

These defining characteristics are also applicable to resources that are supplied within universities. Non-rivalry and non-excludability are combined in Figure 1. Cells 2, 3 and 4 illustrate the continuum of local, internal public goods and resources in universities in contrast to private resources in cell 1.Reference Frost and Morner 14 , Reference Brydon and Vining 24 , Reference Vining 25

Figure 1 A typology of university commons.Reference Frost and Hattke 2 , Reference Frost and Morner 14 , Reference Vining 25

A perfectly private resource is characterized by complete rivalry in use and fully effective property rights. Resources in universities are private goods if they are separable and attributable. Low interdependence between private resources and their underlying activities does not require collective action. Individual research agendas of scholars are a good example of private resources in universities. They are rivalrous in consumption since replications are less valued by the scientific community than novel findings, and it is possible to exclude other scholars from detailed knowledge about upcoming steps on the agenda.

In contrast, as shown in cell 4, pure public resources are non-rivalrous in use and non-excludable. Examples as regards universities are the reputation, the organizational culture and a strategic course, for example, taken by a ‘university for a sustainable future’. On the one hand, the availability of these resources does not diminish with use. They can be transacted again and again without loss of integrity as long as the syntactical rules for deciphering them are known. On the other hand, all university members and units benefit from these resources regardless of whether they have contributed to their provision or maintenance, or not. This creates a public-good dilemma, which arises from free-riding behaviour or social loafing of individuals.Reference Kollock 21 , Reference Baumol 26 In the above example, it is rational for scholars to invest in their own research record instead of contributing to their university’s overall strategy and institutional reputation. The individual member faces immediate costs that generate a benefit that can also be shared by other members of the university, which, in turn, is cheaper for them as someone else bears the costs. As a consequence, as few pure public resources as possible are provided. Organizational governance has to resolve this dilemma of undersupply to promote the provision of pure public resources.

In reality, however, public goods tend to have blurred boundaries. Thus, the intermediate points along the continuum in Figure 1 stand for various degrees of ‘impure’ public resourcesReference Cornes and Sandler 11 whose benefits are partially rivalrous and/or partially excludable: they are called pool resources and club resources.

In cell 2, pool resources are rivalrous in consumption but non-excludable. Examples of this are often professionally driven expert services such as legal services or IT solutions. The provision and use of pool resources is characterized by pooled interdependencies that occur when these common pool resources are constituted and used to realize economies of scale and specialization.Reference Thompson 27 – Reference Grandori 29 The extensive use of these resources by some organization members reduces their availability for others. For instance, scholars may try to spend as much open access funds as possible without considering other colleagues at their university. To exclude beneficiaries by physical and institutional means, however, generates costs. Therefore, these pool resources are vulnerable to exploitation, which is known as the tragedy of the commons.Reference Vining 25 , Reference Hardin 30 The problem is the non-excludability of an unmanaged pool resource and the subtractability of the benefits: what is consumed by one member is not available to others.Reference Messick and McClelland 23 Unless governance arrangements resolve these conflicts, there is a dilemma of overuse.

Cell 3 includes club resources that are rivalrous to a low degree but possess the characteristic of excludability. Thanks to the Nobel laureate James Buchanan, club goods have been introduced to distinguish between public and private goods.Reference Buchanan 31 Due to the nature of high excludability, he thus presented goods and services that can be organized in a club and from whose benefits all non-members are systematically excluded although they could be valuable to them. Transferred to the university context, clubs are single units or central functions. In this case, a high degree of excludability means that if a unit or function has club resources at its disposal – whether in the form of ‘best practice’ or another kind of specialist expertise – it can separate itself from the rest of the organization and exclude non-members from the club. A low degree of rivalry in consumption means that this characteristic particularly applies to resources that are information-based and knowledge-based, because information and knowledge do not diminish by being cut into smaller portions. On the contrary, such information and knowledge can be enriched by dividing it. In universities, examples of club resources are specific capabilities; a kind of best practice in, for example, writing an EU research proposal or running a PhD graduate program. Interdependence is reciprocal, because club resources of one unit can serve as an important input to other units, and vice versa. There is no necessity for intensive interaction between the units to generate these resources.Reference Frost and Morner 14 However, there is the imminent danger that such club resources are strategically sealed off and are not shared within the university. The motivation of such a club is to maintain its position as a holder of idiosyncratic knowledge by hoarding information and expertise. The members of this club do not want to surrender their advantage to a third party, perhaps because they see no benefit in sharing these knowledge resources with other units. In this case, knowledge resources are likely to be underused, and externalities arise.Reference Brydon and Vining 24 Economists call this problem the tragedy of the anti-commons.Reference Buchanan and Yoon 32 , Reference Heller 33 With regard to the governing challenges, the anti-commons problem becomes a dilemma of underuse. To resolve or eliminate the dilemma of underuse and to consider institutionalized collective responses, organizational governance must encourage the units to bundle and share their individual parts of club resources.

To sum up, collective resources of higher education institutions are called university commons. In contrast to private resources, providing and consuming university commons represent a special case of externalities in the form of non-compensated interdependence.Reference Cornes and Sandler 11 , Reference Kollock 21 However, interdependence creates a governance problem.Reference Grandori 34 , Reference Simon 35 University members must choose whether they follow a competitive course of action that furthers their own interests at the expense of others or contribute to a cooperative solution that increases joint interests and results in collective action. Otherwise, three different resource dilemmas arise: they occur when pool resources are overused, when club resources are not shared and therefore underused, and when pure public resources are undersupplied. Organizational governance plays an active role when it comes to resolving these dilemmas and achieving collective action, and developing a university-specific portfolio of university commons.

Governing a Portfolio of University Commons

Many studies approached university governance from a field-level perspective by focusing on changes in the socio-political environment.Reference Musselin and Teixeira 36 , Reference Paradeise, Reale, Bleiklie and Ferlie 37 Other examinations were concerned with how these changes affect the practices of governance, i.e. strategies, structures and controls, and consequently extended the literature to the organizational level.Reference Frost, Hattke and Reihlen 38 In general, governance is concerned with the delineation and implementation of strategies and structures for achieving organizational goals. It is about how managers coordinate and control actors and how these influencers reconcile and prioritize competing claims of organizational stakeholders.Reference Frost, Hattke and Reihlen 39 Taking organizational governance as a reference, this article centres on modes that frame decision-making processes for coordinating interdependencies between economic activities of different organization members and units: the collegial and managerial modes. Subsequently, we disclose inherent challenges of the two modes in facilitating collective action. Finally, we examine how to resolve these challenges so that a specific portfolio of university commons can be governed.

University Governance: Collegial and Managerial Modes

For a long time, universities have been organized as a self-governed community of scholars. This ‘republic of science’ was based on the principle of joint decision-making, mutual peer control and reciprocal coordination between scientists.Reference Polanyi 40 In the second half of the twentieth century however, this extensive professional autonomy came under pressure from ‘post-modern scepticism’, which entailed the creation of a new model of collegial governance, and from ‘market fundamentalism’, which resulted in a more managerial mode of governance.Reference Bleiklie and Kogan 41 , Reference Leicht 42 During the politicization of universities in the 1960s, the ‘elitist’ dominance of professors and the lack of participatory elements for other status groups were criticized as an ‘academic oligarchy’.Reference Clark 43 This interpretation of the Humboldtian University by the political left was the effect of the democratization of societies.

Today’s collegial governance is characterized by democratic participation in academic senates, councils, or committees. In order to include the voices of all status groups, these governing bodies typically prescribe parities between tenured and non-tenured faculty, undergraduate students, as well as for administrative and technical personnel.Reference Hattke, Blaschke and Frost 44 Collegial governance resembles a representative democracy in which preferences of status groups are advanced by elected representatives. Interactions between groups are thus not only restricted to informal communication processes. Joint decision-making is defined as the official governance mode involving mutual convincing and monitoring, and thus exerting peer control. This is how all participants involved in the university are represented in the decision-making process. Collegial governance seeks to achieve collective action by aggregating their preferences by means of majority voting on issues of pre-negotiated agendas.

The introduction of new public management into the public sector by the end of the twentieth century has led to a growth of economic rationality and managerial orientation in the governance of higher education.Reference Clark 45 Managerial governance concentrates decision-making processes and the control of procedures and behaviour in a more asymmetrical way. It is based on hierarchical decision-making of professional boards which are made up of presidents, chancellors, deans and external stakeholders. On the one hand, these boards set up rules and thus use authority to transmit preconditions for decision-making. On the other hand, they enforce strategic goals by allocating resources and budgets according to aggregated performance metrics and negotiated objectives.Reference Frost, Hattke and Reihlen 39 Managerial governance aims to make universities more responsive to rating and ranking results by increasing individual and institutional accountability. To achieve collective action, managerial governance should encourage university members to negotiate with the professional boards and reach an agreement on their contributions to or use of the commons.

Challenges of Collegial and Managerial Governance in Facilitating Collective Action

Fostering collective action in universities calls for organizational governance that allows channelling individual interests and, thus, influencing the processes of creating, sharing and using university commons. Collegial and managerial governance both entail a specific internal logic but, taken individually, are not capable of governing a university-specific portfolio of commons effectively. Political economists have identified various challenges associated with both governance modes that might obstruct collective action.Reference Olson 7 , Reference Miller 19

The challenge of collegial governance is to succeed in transforming originally divergent preferences or interests of different status groups into a common mutual understanding. Preference patterns follow the logical structure of utility judgements: basic value assessments of organization members translate into motives for action in specific situations. However, it is problematic to coordinate collective action across status groups that have divergent preferences. Arrow’s paradox suggests that it is impossible to arrive at one aggregated collective preference order under such conditions.Reference Bernholz 46 , Reference Koehler 47 A satisfactory solution can only be found if representatives of the different status groups prefer the same set of university commons. Efficient collegial governing requires a certain degree of motivational compatibility, in the sense that the parties involved need to have the ability and willingness to cooperate. Only in this case do strategic dialogues, joint discussions and decision-making become possible. Otherwise, representatives may engage in logrolling.Reference Tullock 48 , Reference Buchanan and Tullock 49 Logrolling is a mutual agreement between representatives of different groups to deviate from their own preferences when it comes to negotiating issues that are of minor importance to them. Representatives of one group vote for the preferences of the other group to which these issues have higher importance. In exchange, they receive support from that group when the issues are important to themselves. This trading of favours leads to ineffective collective action, although all representatives participate in the process of decision-making. For example, if every group favours a different commons, it is likely that all commons are agreed upon. When it comes to establishing and maintaining this portfolio of commons, however, groups with narrow interest will not contribute. If all groups prefer taking veto positions on certain commons, the university might miss the opportunity for collective action altogether. Indeed, collegial governance has been extensively criticized for its organized irresponsibilityReference von Lüde 50 and garbage-canReference Cohen, March and Olsen 51 decision-making, which directs collective action towards an arbitrary portfolio of university commons. Resolving resource dilemmas through collegial governance requires the status groups and university members to find common ground. This is only possible if each side can be convinced of certain values in the consensus principle and, additionally, is willing to put a joint solution first. In order to make this happen, a ‘joint production motivation’ capturing the intricate human capacity to actively engage in collaborative activities has to be fostered.Reference Lindenberg and Foss 52

The challenge of managerial governance lies in the high degree of cognitive and information asymmetries between members of universities and the professional board. University members draw on different contexts with regard to solving problems, depending on specific experiences and their embodied and embrained knowledge.Reference Lam 53 This cognitive asymmetry makes it difficult to judge the quality of contributions to university commons, because knowledge-intensive professional services that are at the core of universities – academic research and teaching – are credence goods.Reference Arrow 54 Laymen or outsiders cannot evaluate the quality of these goods with sufficient reliability and therefore must rely on the competencies and professional experience of scholars. But even with a strong professional background, the complexity of academic services hampers an understanding between scholars of different disciplinary backgrounds or specialization. In addition, it prevents the professional board from reaching a level of detail in the knowledge that is essential for informed decision-making on which and how commons should be established.Reference Hinds and Pfeffer 55 This is the main reason why a professional board composed of accomplished scholars from a variety of disciplines is more successful in university leadership.Reference Hattke and Blaschke 56 , Reference Goodall 57 The performance metrics and behaviour controls used by the board to bridge this cognitive and information asymmetry have side effects. First of all, individual performance measures are likely to enforce individual rationality and counteract collective rationality, which is required for collective action. Instead of resolving the commons dilemmas, governance by numbers might worsen the associated problems.Reference Osterloh 58 Besides, incentive systems and pay-for-performance schemes might have motivation crowding effects, especially when they are contingent upon quantified goals.Reference Frey and Jegen 59 , Reference Frey and Oberholzer-Gee 60 The high intrinsic motivation of scholars might diminish if they feel controlled by a management that interferes with their professional autonomy. Thus, even if goals are of a collective nature, the increase of extrinsic motivation due to rewards might not compensate for the loss of intrinsic motivation. Besides, the introduction of regulative pressures might force individual scholars to simply comply with the system of control instead of providing their professional service to the best of their ability.Reference Holmstrom and Milgrom 61 Thus, individualized accountability and the associated micromanagement of scholars has evoked strong criticism of managerial governance, putting its potential for collective action into question.Reference Frost and Brockmann 62

Managerial governance can only cope with resource dilemmas if it is perceived as enabling and non-coercive.Reference Adler and Borys 63 On the one hand, this may be influenced by the fairness of procedures enacted by the supervisory hierarchy.Reference Brockner and Wiesenfeld 64 , Reference De Cremer and van Knippenberg 65 On the other hand, if managerial governance is competence-based, it is rather perceived as enabling (i.e. if the supervisory board is able to include knowledge of professional experts into the decision processes and, thus, improves its own ‘judgeability’).

Towards Reconciliation between Collegialism and Managerialism

Due to the multiple and pluralistic goal systems of universities, the modus operandi of universities cannot be reduced to a single governance mode. While the status groups of universities cannot ignore the demands of external stakeholders, which are mainly communicated managerially, external stakeholders cannot ignore the institutional autonomy of universities, which is exercised collegially. In addition, collegial and managerial governance modes cannot be simply combined, since the norms and values embedded in each mode are often at odds and compete for dominance.Reference Hattke, Vogel and Woiwode 66 For this reason, we suggest that – instead of prioritizing one governance mode over the other or merging both modes into one best possible form of university governance – a strategy of coexistence should be pursued.Reference Pache and Santos 67 The governance challenge is to purposefully orchestrate governance modes according to their potentials for coping with different preferences and cognitive asymmetry.Reference Frost and Morner 14 Heterogeneous or opposing interests need to be aligned, allowing them to reach integrative, negotiated agreements. Cognitive asymmetries need to be bridged to arrive at a mutual understanding and common perception of relevant information and practices in use. The concept of bridging has been introduced by Nooteboom.Reference Nooteboom 68 Bridging is not about comprehensively reducing cognitive asymmetries but about creating overlaps so that sufficient capacity remains for specialized search heuristics while still enabling a shared understanding of problems. This is essential for the use of collegial governance and for effective leverage of managerial governance. Direct supervision and rules can only be implemented effectively if the professional board is able to ‘judge’ the instances of consumption and contributions that promote the use of pool resources, the sharing of club resources, and the creation of pure public resources.

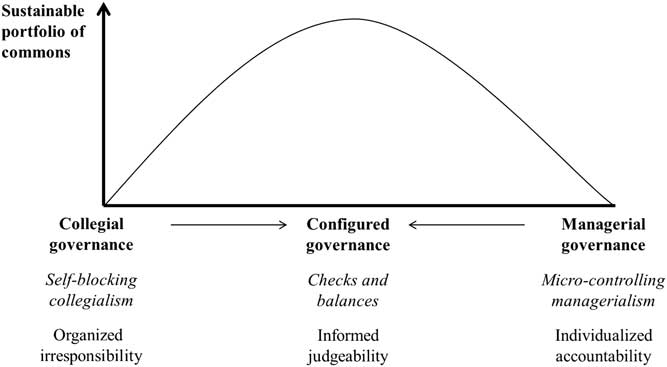

Neither collegial governance nor managerial governance alone can foster collective action. However, as pluralistic organizations, universities are able to set up configured governance. The overall configuration of collegial and managerial modes constitutes a system of checks and balances that helps to resolve resource dilemmas and to achieve collective action. Instead of the organized irresponsibility of self-blocking collegialism or the negative side effects of a micro-controlling managerialism, the appropriate configuration of collegial and managerial modes allows for maintaining a university-specific portfolio of commons that is based on what we term informed judgeability. This means that managerial decisions are responsive to bottom-up collegial judgements. The relationship is signified by the inverted U-shaped curve in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Configuration of governance modes and university commons.

How can universities implement such a configured system of governance? Empirical studies on collective action in universities suggest that, first, collegial and managerial governance are substitutes with regard to collective performance and, second, that the effectiveness of different governance modes in fostering collective action depends on the characteristics of coordinated activities, especially on their underlying interdependencies.Reference Hattke, Blaschke and Frost 69 The configuration of governance modes varies significantly with the type of interdependence. Thus, we expect that a ‘mix and match’ of governance modes and fields of action contributes to a sustainable portfolio of university commons.

Managerial governance seems to be more effective for pooled and reciprocal interdependence while collegial modes are more suitable for intensive interdependencies such as the complex core issues of research and teaching. In the case of pool resources – thus, pooled interdependence – the professional board lays down rules that govern access to resources and, accordingly, encourages units not to overuse the resources. In the case of club resources – thus, reciprocal interdependence – managerial governance is able to encourage units and groups to share their resources – mainly knowledge and expertise – with others in the organization and, finally, overcome their ‘sharing hostility’.Reference Michailova and Gupta 70 Of course, nobody can be forced to share their club resources. However, if the supervisory hierarchy has enough expertise and cognitive proximity and is therefore able to estimate the amount, use and flow of resources between university members or units, it can determine who receives which, and what amount of, resources. Managerial governance is transformed into what we call informed judgeability, which is a kind of competence-based procedural governance. In the case of pure public resources – thus, intensive interdependence – collegial governance is able to cope with the dilemma of undersupply. It can be solved if the involved status groups, units and university members believe that their contribution has an important effect on the provision of pure public resources. This does not mean that their inputs can be measured or singled out. What is crucial is that the involved parties are aware of their critical impact on the final decision. To avoid organized irresponsibility of self-blocking collegialism, collegial governance needs to be embedded in a set of accepted rules. This is what we define as configured governance.

Conclusion

We took the increasing collaborative nature of activities in universities as a starting point and argued that governing collective action effectively is one of the most important challenges for modern universities. According to the perspective of university commons, the challenge for university governance lies in coordinating activities within the university so that the respective intended portfolio of specific commons can be established, shared and used. As a result, dilemmas of undersupply, overuse and underuse can be resolved.

Ultimately, the perspective of university commons does not imply that all activities should be performed collectively. After all, universities are still an archetype of loosely coupled systems with multiple and pluralistic goal systems. Instead, as an alternative governance perspective, the concept of university commons implies that university leadership utilizes configured governance – thus, a mix of governance modes – to ensure that a strategically relevant and sustainable portfolio of university commons can be generated, shared, and used effectively.

Jetta Frost is full professor of organization and management, as well as vice president at the University of Hamburg, Germany. She was founding director of the Center for a Sustainable University (KNU) from 2011–2013 and is a member of the European Academy of Science and Art. Jetta Frost received her PhD and her habilitation at the University of Zurich. Her current research interests are knowledge governance in universities and multidivisional firms, organization and management control, strategic solutions for value creation management, and agile leadership.

Fabian Hattke is interim professor of organization and management at the University of Hamburg, Germany. He is associate member of the Center for Higher Education and Science Studies (CHESS) at the University of Zurich and guest lecturer for academic management at the University of Basel, Switzerland. He has published several books and articles on the governance of universities. Among his research interests are institutional change and pluralism, as well as performance management and motivation in the public sector.