1 Introduction

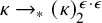

Partition relations appear frequently in combinatorics. Ramsey showed that the set of natural numbers,

![]() $\omega $

, satisfies the finite partition relations

$\omega $

, satisfies the finite partition relations

![]() $\omega \rightarrow (\omega )^k_2$

for each

$\omega \rightarrow (\omega )^k_2$

for each

![]() $k < \omega $

. The infinite exponent partition relation

$k < \omega $

. The infinite exponent partition relation

![]() $\omega \rightarrow (\omega )^\omega _2$

(also called the Ramsey property for all partitions) is a natural generalization which is not compatible with the axiom of choice. However, simply definable partitions such as Borel or analytic partitions always satisfy the Ramsey property by results of Galvin and Prikry [Reference Galvin and Prikry7] and Silver [Reference Silver17]. Mathias [Reference Mathias15] produced many important results concerning the Ramsey property including the technique of Mathias forcing which is used to verify

$\omega \rightarrow (\omega )^\omega _2$

(also called the Ramsey property for all partitions) is a natural generalization which is not compatible with the axiom of choice. However, simply definable partitions such as Borel or analytic partitions always satisfy the Ramsey property by results of Galvin and Prikry [Reference Galvin and Prikry7] and Silver [Reference Silver17]. Mathias [Reference Mathias15] produced many important results concerning the Ramsey property including the technique of Mathias forcing which is used to verify

![]() $\omega \rightarrow (\omega )^\omega _2$

in the Solovay model and Woodin’s extension

$\omega \rightarrow (\omega )^\omega _2$

in the Solovay model and Woodin’s extension

![]() $\mathsf {AD}^+$

of the axiom of determinacy,

$\mathsf {AD}^+$

of the axiom of determinacy,

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

. Mathias also studied the Ramsey almost everywhere behavior of functions on the Ramsey space

$\mathsf {AD}$

. Mathias also studied the Ramsey almost everywhere behavior of functions on the Ramsey space

![]() $[\omega ]^\omega $

such as when every function

$[\omega ]^\omega $

such as when every function

![]() $\Phi : [\omega ]^\omega \rightarrow \mathbb {R}$

is Ramsey almost everywhere continuous or every relation

$\Phi : [\omega ]^\omega \rightarrow \mathbb {R}$

is Ramsey almost everywhere continuous or every relation

![]() $R \subseteq [\omega ]^\omega \times \mathbb {R}$

has a Ramsey almost everywhere uniformization. Recently, these two properties have been used by Schritteser and Törnquist [Reference Schrittesser and Törnquist16] to show that

$R \subseteq [\omega ]^\omega \times \mathbb {R}$

has a Ramsey almost everywhere uniformization. Recently, these two properties have been used by Schritteser and Törnquist [Reference Schrittesser and Törnquist16] to show that

![]() $\omega \rightarrow (\omega )^\omega _2$

implies there are no maximal almost disjoint families on

$\omega \rightarrow (\omega )^\omega _2$

implies there are no maximal almost disjoint families on

![]() $\omega $

. Finite exponent partition relations on uncountable cardinals are important in set theory and motivate large cardinal axioms such as the weakly compact and Ramsey cardinals. Martin, Kunen [Reference Solovay18], Jackson [Reference Jackson8], Kechris, Kleinberg, Moschovakis and Woodin [Reference Kechris, Kleinberg, Moschovakis and Hugh Woodin12] showed that the axiom of determinacy is a natural theory in which

$\omega $

. Finite exponent partition relations on uncountable cardinals are important in set theory and motivate large cardinal axioms such as the weakly compact and Ramsey cardinals. Martin, Kunen [Reference Solovay18], Jackson [Reference Jackson8], Kechris, Kleinberg, Moschovakis and Woodin [Reference Kechris, Kleinberg, Moschovakis and Hugh Woodin12] showed that the axiom of determinacy is a natural theory in which

![]() ${\omega _1}$

and many other cardinals

${\omega _1}$

and many other cardinals

![]() $\kappa $

possess even the strong partition relation:

$\kappa $

possess even the strong partition relation:

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow (\kappa )^\kappa _2$

. Kleinberg [Reference Kleinberg14], Martin and Paris studied functions on the finite partition spaces of

$\kappa \rightarrow (\kappa )^\kappa _2$

. Kleinberg [Reference Kleinberg14], Martin and Paris studied functions on the finite partition spaces of

![]() ${\omega _1}$

and produced ultrapower representations for

${\omega _1}$

and produced ultrapower representations for

![]() $\omega _n$

, showed

$\omega _n$

, showed

![]() $\omega _2$

has weak partition property and established combinatorial properties such as Jónssonness for

$\omega _2$

has weak partition property and established combinatorial properties such as Jónssonness for

![]() $\omega _n$

, for all

$\omega _n$

, for all

![]() $n \in \omega $

. Under the axiom of determinacy, the authors ([Reference Chan and Jackson4], [Reference Chan2], [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang6] and [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang5]) studied variations of almost everywhere continuity properties for functions on the partition spaces of

$n \in \omega $

. Under the axiom of determinacy, the authors ([Reference Chan and Jackson4], [Reference Chan2], [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang6] and [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang5]) studied variations of almost everywhere continuity properties for functions on the partition spaces of

![]() ${\omega _1}$

and

${\omega _1}$

and

![]() $\omega _2$

according to suitable partition measures and applied these results to distinguish the cardinalities below

$\omega _2$

according to suitable partition measures and applied these results to distinguish the cardinalities below

![]() ${\mathscr {P}({\omega _1})}$

and

${\mathscr {P}({\omega _1})}$

and

![]() ${\mathscr {P}(\omega _2)}$

. There,

${\mathscr {P}(\omega _2)}$

. There,

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

provided useful motivation and elegant arguments, but the techniques have severe limitations. Here, the authors will prove stronger almost everywhere behaviors for functions on partition spaces (such as continuity and monotonicity) from pure combinatorial principles, and these results will be applied to distinguish important cardinalities below the power set of partition cardinals. This will lead to new results about the most important weak and strong partition cardinals of determinacy.

$\mathsf {AD}$

provided useful motivation and elegant arguments, but the techniques have severe limitations. Here, the authors will prove stronger almost everywhere behaviors for functions on partition spaces (such as continuity and monotonicity) from pure combinatorial principles, and these results will be applied to distinguish important cardinalities below the power set of partition cardinals. This will lead to new results about the most important weak and strong partition cardinals of determinacy.

A basic question of infinitary combinatorics is the computation of the size of infinite sets. Cantor formalized the notion of size and the comparison of sizes. Let X and Y be two sets. One says X and Y have the same cardinality (denoted

![]() $|X| = |Y|$

) if and only if there is a bijection

$|X| = |Y|$

) if and only if there is a bijection

![]() $\Phi : X \rightarrow Y$

. The cardinality of X is the (proper) class of sets Y which are in bijection with X. The cardinality of X is less than or equal the cardinality of Y (denoted

$\Phi : X \rightarrow Y$

. The cardinality of X is the (proper) class of sets Y which are in bijection with X. The cardinality of X is less than or equal the cardinality of Y (denoted

![]() $|X| \leq |Y|$

) if and only if there is an injection

$|X| \leq |Y|$

) if and only if there is an injection

![]() $\Phi : X \rightarrow Y$

. The cardinality of X is strictly smaller than the cardinality of Y (denoted

$\Phi : X \rightarrow Y$

. The cardinality of X is strictly smaller than the cardinality of Y (denoted

![]() $|X| < |Y|$

) if and only if

$|X| < |Y|$

) if and only if

![]() $|X| \leq |Y|$

but

$|X| \leq |Y|$

but

![]() $\neg (|Y| \leq |X|)$

.

$\neg (|Y| \leq |X|)$

.

The axiom of choice,

![]() $\mathsf {AC}$

, implies every set is wellorderable. Thus, the class of cardinalities forms a wellordered class under the injection relation. Each cardinality class has a canonical wellordered member (an ordinal) called the cardinal of the class. Wellorderings of sets (even

$\mathsf {AC}$

, implies every set is wellorderable. Thus, the class of cardinalities forms a wellordered class under the injection relation. Each cardinality class has a canonical wellordered member (an ordinal) called the cardinal of the class. Wellorderings of sets (even

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

) are incompatible with certain definability perspectives. This is usually the consequence of definable sets possessing combinatorial regularity properties.

$\mathbb {R}$

) are incompatible with certain definability perspectives. This is usually the consequence of definable sets possessing combinatorial regularity properties.

Let

![]() $\omega $

denote the set of natural numbers or the first infinite cardinal. Cantor showed that

$\omega $

denote the set of natural numbers or the first infinite cardinal. Cantor showed that

![]() $\omega $

does not surject onto

$\omega $

does not surject onto

![]() ${\mathscr {P}(\omega )}$

. Thus,

${\mathscr {P}(\omega )}$

. Thus,

![]() $\omega < |{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}|$

. Let

$\omega < |{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}|$

. Let

![]() ${\omega _1}$

denote the first uncountable cardinal. With the axiom of choice,

${\omega _1}$

denote the first uncountable cardinal. With the axiom of choice,

![]() ${\omega _1} \leq |{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}|$

using a wellordering of

${\omega _1} \leq |{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}|$

using a wellordering of

![]() ${\mathscr {P}(\omega )}$

or

${\mathscr {P}(\omega )}$

or

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

. However, if the axiom of choice is omitted and instead

$\mathbb {R}$

. However, if the axiom of choice is omitted and instead

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

is assumed to satisfy the perfect set property and the property of Baire, then a classical argument involving the Kuratowski–Ulam theorem would show that there is no injection of

$\mathbb {R}$

is assumed to satisfy the perfect set property and the property of Baire, then a classical argument involving the Kuratowski–Ulam theorem would show that there is no injection of

![]() ${\omega _1}$

into

${\omega _1}$

into

![]() $\mathbb {R}$

or

$\mathbb {R}$

or

![]() ${\mathscr {P}(\omega )}$

. Thus,

${\mathscr {P}(\omega )}$

. Thus,

![]() ${\omega _1}$

and

${\omega _1}$

and

![]() $|{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}| = |\mathbb {R}|$

are incompatible cardinalities. Moreover, the perfect set property completely characterizes the structure of the cardinalities below

$|{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}| = |\mathbb {R}|$

are incompatible cardinalities. Moreover, the perfect set property completely characterizes the structure of the cardinalities below

![]() $|{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}|$

in a manner which satisfies a choiceless continuum hypothesis: The only uncountable cardinality below

$|{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}|$

in a manner which satisfies a choiceless continuum hypothesis: The only uncountable cardinality below

![]() $|{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}|$

is

$|{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}|$

is

![]() $|{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}|$

.

$|{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}|$

.

With the perfect set property and the Baire property, the structure of the cardinalities below

![]() ${\mathscr {P}({\omega _1})}$

is nonlinear since

${\mathscr {P}({\omega _1})}$

is nonlinear since

![]() ${\omega _1}$

and

${\omega _1}$

and

![]() $|\mathbb {R}| = |{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}|$

are two incompatible cardinalities below

$|\mathbb {R}| = |{\mathscr {P}(\omega )}|$

are two incompatible cardinalities below

![]() $|{\mathscr {P}({\omega _1})}|$

. For each

$|{\mathscr {P}({\omega _1})}|$

. For each

![]() $\epsilon \leq {\omega _1}$

, let

$\epsilon \leq {\omega _1}$

, let

![]() $[{\omega _1}]^\epsilon $

be the increasing sequence space consisting of increasing functions

$[{\omega _1}]^\epsilon $

be the increasing sequence space consisting of increasing functions

![]() $f : \epsilon \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

.

$f : \epsilon \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

.

![]() ${\mathscr {P}({\omega _1})}$

and

${\mathscr {P}({\omega _1})}$

and

![]() $[{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}$

are in bijection. Therefore, sequence spaces represent natural combinatorial cardinalities below

$[{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}$

are in bijection. Therefore, sequence spaces represent natural combinatorial cardinalities below

![]() $|{\mathscr {P}({\omega _1})}| = |[{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}|$

. Another important example is

$|{\mathscr {P}({\omega _1})}| = |[{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}|$

. Another important example is

![]() $[{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}} = \bigcup _{\epsilon < {\omega _1}} [{\omega _1}]^\epsilon _*$

, which is the set of countable length increasing sequences of countable ordinals. A natural question is to distinguish

$[{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}} = \bigcup _{\epsilon < {\omega _1}} [{\omega _1}]^\epsilon _*$

, which is the set of countable length increasing sequences of countable ordinals. A natural question is to distinguish

![]() $|[{\omega _1}]^\omega |$

,

$|[{\omega _1}]^\omega |$

,

![]() $|[{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}|$

and

$|[{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}|$

and

![]() $|{\mathscr {P}({\omega _1})}| = |[{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}|$

under suitable regularity properties. A helpful combinatorial property possessed by

$|{\mathscr {P}({\omega _1})}| = |[{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}|$

under suitable regularity properties. A helpful combinatorial property possessed by

![]() ${\omega _1}$

(in some natural theories) is the strong partition property,

${\omega _1}$

(in some natural theories) is the strong partition property,

![]() ${\omega _1} \rightarrow _* ({\omega _1})^{\omega _1}_2$

.

${\omega _1} \rightarrow _* ({\omega _1})^{\omega _1}_2$

.

Partition properties will be discussed in detail in Section 2. Let

![]() $\kappa $

be a cardinal,

$\kappa $

be a cardinal,

![]() $\epsilon \leq \kappa $

and

$\epsilon \leq \kappa $

and

![]() $A \subseteq \kappa $

. Let

$A \subseteq \kappa $

. Let

![]() $[A]^\epsilon _*$

be the collection of increasing functions

$[A]^\epsilon _*$

be the collection of increasing functions

![]() $f : \epsilon \rightarrow A$

of the correct type (i.e., discontinuous everywhere and has uniform cofinality

$f : \epsilon \rightarrow A$

of the correct type (i.e., discontinuous everywhere and has uniform cofinality

![]() $\omega $

). The partition relation

$\omega $

). The partition relation

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\epsilon _2$

is the assertion that for all

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\epsilon _2$

is the assertion that for all

![]() $P : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow 2$

, there is a closed and unbounded (club)

$P : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow 2$

, there is a closed and unbounded (club)

![]() $C \subseteq {\omega _1}$

and

$C \subseteq {\omega _1}$

and

![]() $i \in 2$

so that for all

$i \in 2$

so that for all

![]() $f \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

,

$f \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

,

![]() $P(f) = i$

. If for all

$P(f) = i$

. If for all

![]() $\epsilon < \kappa $

,

$\epsilon < \kappa $

,

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\epsilon _2$

holds, then

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\epsilon _2$

holds, then

![]() $\kappa $

is called a weak partition cardinal. If

$\kappa $

is called a weak partition cardinal. If

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\kappa _2$

, then

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\kappa _2$

, then

![]() $\kappa $

is called a strong partition cardinal. If

$\kappa $

is called a strong partition cardinal. If

![]() $\epsilon \leq \kappa $

and

$\epsilon \leq \kappa $

and

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\epsilon _2$

holds, then the partition filter

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\epsilon _2$

holds, then the partition filter

![]() $\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

on

$\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

on

![]() $[\kappa ]^\epsilon _*$

defined by

$[\kappa ]^\epsilon _*$

defined by

![]() $X \in \mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

if and only if there is a club

$X \in \mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

if and only if there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq \kappa $

so that

$C \subseteq \kappa $

so that

![]() $[C]^\epsilon _* \subseteq X$

is an ultrafilter.

$[C]^\epsilon _* \subseteq X$

is an ultrafilter.

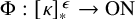

If

![]() $\kappa $

satisfies suitable partition relations, then the partition spaces

$\kappa $

satisfies suitable partition relations, then the partition spaces

![]() $[\kappa ]^\epsilon _*$

for

$[\kappa ]^\epsilon _*$

for

![]() $\epsilon < \kappa $

,

$\epsilon < \kappa $

,

![]() $[\kappa ]^{<\kappa }_*$

and

$[\kappa ]^{<\kappa }_*$

and

![]() $[\kappa ]^\kappa _*$

represent important cardinalities below

$[\kappa ]^\kappa _*$

represent important cardinalities below

![]() ${\mathscr {P}(\kappa )}$

. Distinguishing the cardinality of these partition spaces involve understanding the possible injections that exist between these partition spaces. To answer such questions, this paper will use partition properties to obtain very deep understandings of the behavior of functions

${\mathscr {P}(\kappa )}$

. Distinguishing the cardinality of these partition spaces involve understanding the possible injections that exist between these partition spaces. To answer such questions, this paper will use partition properties to obtain very deep understandings of the behavior of functions

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

on measure one sets according to the relevant partition measure,

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

on measure one sets according to the relevant partition measure,

![]() $\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

. The following will summarize and motivate the main results of the paper concerning these almost everywhere behaviors of functions.

$\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

. The following will summarize and motivate the main results of the paper concerning these almost everywhere behaviors of functions.

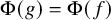

In [Reference Chan2], it is shown that if

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\kappa _2$

, then every function

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\kappa _2$

, then every function

![]() $\Lambda : [\kappa ]^\kappa _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, there is an ordinal

$\Lambda : [\kappa ]^\kappa _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, there is an ordinal

![]() $\alpha $

so that

$\alpha $

so that

![]() $\Lambda ^{-1}[\{\alpha \}]| = |[\kappa ]^\kappa _*|$

. This asserts that

$\Lambda ^{-1}[\{\alpha \}]| = |[\kappa ]^\kappa _*|$

. This asserts that

![]() $|[\kappa ]^\kappa _*| = |{\mathscr {P}(\kappa )}|$

satisfies a regularity property with respect to wellordered decompositions. The set

$|[\kappa ]^\kappa _*| = |{\mathscr {P}(\kappa )}|$

satisfies a regularity property with respect to wellordered decompositions. The set

![]() $[\kappa ]^{<\kappa }_*$

does not satisfy such regularity. This is used in [Reference Chan2] to show that

$[\kappa ]^{<\kappa }_*$

does not satisfy such regularity. This is used in [Reference Chan2] to show that

![]() $|[\kappa ]^{<\kappa }_*| < |[\kappa ]^\kappa _*|= |{\mathscr {P}(\kappa )}|$

. This paper is motivated by the question of distinguishing the cardinality of

$|[\kappa ]^{<\kappa }_*| < |[\kappa ]^\kappa _*|= |{\mathscr {P}(\kappa )}|$

. This paper is motivated by the question of distinguishing the cardinality of

![]() $[\kappa ]^\epsilon $

for

$[\kappa ]^\epsilon $

for

![]() $\epsilon < \kappa $

and

$\epsilon < \kappa $

and

![]() $[\kappa ]^{<\kappa }_*$

. For these computations, it will be important to understand functions

$[\kappa ]^{<\kappa }_*$

. For these computations, it will be important to understand functions

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \kappa $

through continuity properties.

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \kappa $

through continuity properties.

To motivate continuity, suppose

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

. Given

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

. Given

![]() $f \in [\kappa ]^\epsilon _*$

,

$f \in [\kappa ]^\epsilon _*$

,

![]() $\Phi $

can be considered as an abstract procedure which uses information about f to assign an ordinal value. Examples of such information include specific values of

$\Phi $

can be considered as an abstract procedure which uses information about f to assign an ordinal value. Examples of such information include specific values of

![]() $f(\alpha )$

for

$f(\alpha )$

for

![]() $\alpha < \epsilon $

, initial segments

$\alpha < \epsilon $

, initial segments

![]() $f \upharpoonright \alpha $

for

$f \upharpoonright \alpha $

for

![]() $\alpha < \epsilon $

or possibly the entirety of f or the values of f on some unbounded subsets of

$\alpha < \epsilon $

or possibly the entirety of f or the values of f on some unbounded subsets of

![]() $\epsilon $

. An almost everywhere continuity property intuitively asserts that for

$\epsilon $

. An almost everywhere continuity property intuitively asserts that for

![]() $\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

-almost all f,

$\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

-almost all f,

![]() $\Phi $

can assign an ordinal to f using only information from f which comes from a well-defined bounded subset of

$\Phi $

can assign an ordinal to f using only information from f which comes from a well-defined bounded subset of

![]() $\epsilon $

.

$\epsilon $

.

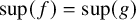

One appealing continuity property for a function

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \kappa $

(with

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \kappa $

(with

![]() $\epsilon < \kappa $

) would be that for

$\epsilon < \kappa $

) would be that for

![]() $\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

-almost all f, there exists a

$\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

-almost all f, there exists a

![]() $\delta < \epsilon $

so that

$\delta < \epsilon $

so that

![]() $\Phi (f)$

only depends on

$\Phi (f)$

only depends on

![]() $f \upharpoonright \delta $

. However, such a property is impossible by the following illustrative example. If

$f \upharpoonright \delta $

. However, such a property is impossible by the following illustrative example. If

![]() $\kappa $

satisfies

$\kappa $

satisfies

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^2_2$

, then

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^2_2$

, then

![]() $\kappa $

is a regular cardinal. Thus, the function

$\kappa $

is a regular cardinal. Thus, the function

![]() $\Psi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \kappa $

defined by

$\Psi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \kappa $

defined by

![]() $\Psi (f) = \sup (f)$

is well defined and it depends on more than any initial segment. This suggests that perhaps a general function

$\Psi (f) = \sup (f)$

is well defined and it depends on more than any initial segment. This suggests that perhaps a general function

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon \rightarrow \kappa $

might have a fixed

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon \rightarrow \kappa $

might have a fixed

![]() $\delta < \epsilon $

so that for

$\delta < \epsilon $

so that for

![]() $\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

-almost all f,

$\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

-almost all f,

![]() $\Phi (f)$

depends only on the initial segment

$\Phi (f)$

depends only on the initial segment

![]() $f \upharpoonright \delta $

and

$f \upharpoonright \delta $

and

![]() $\sup (f)$

. Under suitable partition properties, such a continuity will be true more generally for functions

$\sup (f)$

. Under suitable partition properties, such a continuity will be true more generally for functions

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

with

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

with

![]() ${\mathrm {cof}}(\epsilon ) = \omega $

(and this cofinality assumption is generally necessary).

${\mathrm {cof}}(\epsilon ) = \omega $

(and this cofinality assumption is generally necessary).

Fix

![]() $\epsilon < \kappa $

a limit ordinal with

$\epsilon < \kappa $

a limit ordinal with

![]() ${\mathrm {cof}}(\epsilon ) = \omega $

. Define an equivalence relation

${\mathrm {cof}}(\epsilon ) = \omega $

. Define an equivalence relation

![]() $E_0$

on

$E_0$

on

![]() $[\kappa ]^\epsilon $

by

$[\kappa ]^\epsilon $

by

![]() $f \ E_0 \ g$

if and only if there exists an

$f \ E_0 \ g$

if and only if there exists an

![]() $\alpha < \epsilon $

so that for all

$\alpha < \epsilon $

so that for all

![]() $\beta $

with

$\beta $

with

![]() $\alpha < \beta < \epsilon $

,

$\alpha < \beta < \epsilon $

,

![]() $f(\beta ) = g(\beta )$

. A function

$f(\beta ) = g(\beta )$

. A function

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

is

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

is

![]() $E_0$

-invariant if and only if whenever

$E_0$

-invariant if and only if whenever

![]() $f \ E_0 \ g$

,

$f \ E_0 \ g$

,

![]() $\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

. The first step is the following independently interesting result that functions which are

$\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

. The first step is the following independently interesting result that functions which are

![]() $E_0$

-invariant

$E_0$

-invariant

![]() $\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

-almost everywhere depend only on the supremum

$\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

-almost everywhere depend only on the supremum

![]() $\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

-almost everywhere under suitable partition relations.

$\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

-almost everywhere under suitable partition relations.

Theorem 3.6. Suppose

![]() $\kappa $

is a cardinal,

$\kappa $

is a cardinal,

![]() $\epsilon < \kappa $

is a limit ordinal with

$\epsilon < \kappa $

is a limit ordinal with

![]() ${\mathrm {cof}}(\epsilon ) = \omega $

and

${\mathrm {cof}}(\epsilon ) = \omega $

and

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^{\epsilon \cdot \epsilon }_2$

holds. Let

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^{\epsilon \cdot \epsilon }_2$

holds. Let

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

be a function which is

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

be a function which is

![]() $E_0$

-invariant

$E_0$

-invariant

![]() $\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

-almost everywhere. Then there is a club

$\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

-almost everywhere. Then there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq \kappa $

so that for all

$C \subseteq \kappa $

so that for all

![]() $f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if

$f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if

![]() $\sup (f) = \sup (g)$

, then

$\sup (f) = \sup (g)$

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

.

$\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

.

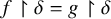

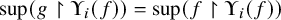

Using this theorem, the desired almost everywhere short length continuity result is established.

Theorem 3.7. Suppose

![]() $\kappa $

is a cardinal,

$\kappa $

is a cardinal,

![]() $\epsilon < \kappa $

is a limit ordinal with

$\epsilon < \kappa $

is a limit ordinal with

![]() ${\mathrm {cof}}(\epsilon ) = \omega $

and

${\mathrm {cof}}(\epsilon ) = \omega $

and

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^{\epsilon \cdot \epsilon }_2$

holds. For any function

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^{\epsilon \cdot \epsilon }_2$

holds. For any function

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, there is a club

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq \kappa $

and a

$C \subseteq \kappa $

and a

![]() $\delta < \epsilon $

so that for all

$\delta < \epsilon $

so that for all

![]() $f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if

$f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if

![]() $f \upharpoonright \delta = g \upharpoonright \delta $

and

$f \upharpoonright \delta = g \upharpoonright \delta $

and

![]() $\sup (f) = \sup (g)$

, then

$\sup (f) = \sup (g)$

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

.

$\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

.

The almost everywhere short length continuity of Theorem 3.7 is used to show that if

![]() $\kappa $

is a weak partition cardinal, then for any

$\kappa $

is a weak partition cardinal, then for any

![]() $\chi < \kappa $

,

$\chi < \kappa $

,

![]() ${}^{<\kappa }\kappa $

does not inject into

${}^{<\kappa }\kappa $

does not inject into

![]() ${}^\chi \kappa $

or even

${}^\chi \kappa $

or even

![]() ${}^\chi \delta $

for any ordinal

${}^\chi \delta $

for any ordinal

![]() $\delta $

by providing a sufficiently complete analysis of potential injections.

$\delta $

by providing a sufficiently complete analysis of potential injections.

Theorem 4.4. Suppose

![]() $\kappa $

is a cardinal so that

$\kappa $

is a cardinal so that

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^{<\kappa }_2$

. Then for all

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^{<\kappa }_2$

. Then for all

![]() $\chi < \kappa $

, there is no injection of

$\chi < \kappa $

, there is no injection of

![]() ${}^{<\kappa }\kappa $

into

${}^{<\kappa }\kappa $

into

![]() ${}^\chi \mathrm {ON}$

, the class of

${}^\chi \mathrm {ON}$

, the class of

![]() $\chi $

-length sequences of ordinals. In particular, for all

$\chi $

-length sequences of ordinals. In particular, for all

![]() $\chi < \kappa $

,

$\chi < \kappa $

,

![]() $|{}^\chi \kappa | < |{}^{<\kappa }\kappa |$

.

$|{}^\chi \kappa | < |{}^{<\kappa }\kappa |$

.

A stronger continuity notion would assert that a function

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

(with

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

(with

![]() $\epsilon < \kappa $

) has finitely many locations in

$\epsilon < \kappa $

) has finitely many locations in

![]() $\epsilon $

depending solely on

$\epsilon $

depending solely on

![]() $\Phi $

so that

$\Phi $

so that

![]() $\Phi (f)$

depends only on the behavior of f at these finitely many locations. (By the previous example, one of these locations must be allowed to be the supremum of f.) The next result states that if

$\Phi (f)$

depends only on the behavior of f at these finitely many locations. (By the previous example, one of these locations must be allowed to be the supremum of f.) The next result states that if

![]() $\epsilon $

is countable and

$\epsilon $

is countable and

![]() $\kappa $

satisfies a suitable partition relation, then

$\kappa $

satisfies a suitable partition relation, then

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

will satisfy a strong almost everywhere short length continuity.

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

will satisfy a strong almost everywhere short length continuity.

Theorem 3.9. Suppose

![]() $\kappa $

is a cardinal,

$\kappa $

is a cardinal,

![]() $\epsilon < \omega _1$

and

$\epsilon < \omega _1$

and

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^{\epsilon \cdot \epsilon }_2$

holds. Let

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^{\epsilon \cdot \epsilon }_2$

holds. Let

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

. Then there is a club

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

. Then there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq \kappa $

and finitely many ordinals

$C \subseteq \kappa $

and finitely many ordinals

![]() $\delta _0, ..., \delta _k \leq \epsilon $

so that for all

$\delta _0, ..., \delta _k \leq \epsilon $

so that for all

![]() $f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

$f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

![]() $0 \leq i \leq k$

,

$0 \leq i \leq k$

,

![]() $\sup (f \upharpoonright \delta _i) = \sup (g \upharpoonright \delta _i)$

, then

$\sup (f \upharpoonright \delta _i) = \sup (g \upharpoonright \delta _i)$

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

.

$\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

.

Suppose

![]() $\epsilon \leq \kappa $

and

$\epsilon \leq \kappa $

and

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

. A natural question is that, if one increases the information stored in f by increasing the values of f, could the value of

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

. A natural question is that, if one increases the information stored in f by increasing the values of f, could the value of

![]() $\Phi $

possibly decrease? An almost everywhere monotonicity property for

$\Phi $

possibly decrease? An almost everywhere monotonicity property for

![]() $\Phi $

would assert that for

$\Phi $

would assert that for

![]() $\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

almost all

$\mu ^\kappa _\epsilon $

almost all

![]() $f,g \in [\kappa ]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

$f,g \in [\kappa ]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

![]() $\alpha < \epsilon $

,

$\alpha < \epsilon $

,

![]() $f(\alpha ) \leq g(\alpha )$

, then

$f(\alpha ) \leq g(\alpha )$

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) \leq \Phi (g)$

. By Fact 5.1, for all functions of the form

$\Phi (f) \leq \Phi (g)$

. By Fact 5.1, for all functions of the form

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

to satisfy this almost everywhere monotonicity property, one must at least have the partition relation

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

to satisfy this almost everywhere monotonicity property, one must at least have the partition relation

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\epsilon _2$

. If

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\epsilon _2$

. If

![]() $\epsilon $

is countable, then the strong almost everywhere short length continuity of Theorem 3.9 implies the following almost everywhere monotonicity result.

$\epsilon $

is countable, then the strong almost everywhere short length continuity of Theorem 3.9 implies the following almost everywhere monotonicity result.

Theorem 4.8. Suppose

![]() $\kappa $

is a cardinal,

$\kappa $

is a cardinal,

![]() $\epsilon < {\omega _1}$

,

$\epsilon < {\omega _1}$

,

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^{\epsilon \cdot \epsilon }_2$

holds and

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^{\epsilon \cdot \epsilon }_2$

holds and

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

. Then there is a club

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

. Then there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq \kappa $

so that for all

$C \subseteq \kappa $

so that for all

![]() $f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

$f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

![]() $\alpha < \epsilon $

,

$\alpha < \epsilon $

,

![]() $f(\alpha ) \leq g(\alpha )$

, then

$f(\alpha ) \leq g(\alpha )$

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) \leq \Phi (g)$

.

$\Phi (f) \leq \Phi (g)$

.

When

![]() ${\mathrm {cof}}(\epsilon ) = \omega $

, one only has the weaker almost everywhere short length continuity property of Theorem 3.7. Moreover, there are functions on partition spaces of high dimension which do not satisfy a recognizable continuity property. Regardless, almost everywhere monotonicity still holds for functions on partition spaces assuming the appropriate partition relation.

${\mathrm {cof}}(\epsilon ) = \omega $

, one only has the weaker almost everywhere short length continuity property of Theorem 3.7. Moreover, there are functions on partition spaces of high dimension which do not satisfy a recognizable continuity property. Regardless, almost everywhere monotonicity still holds for functions on partition spaces assuming the appropriate partition relation.

Theorem 5.3. Suppose

![]() $\kappa $

is a cardinal satisfying

$\kappa $

is a cardinal satisfying

![]() $\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\kappa _2$

. For any function

$\kappa \rightarrow _* (\kappa )^\kappa _2$

. For any function

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\kappa _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, there is a club

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\kappa _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq \kappa $

so that for all

$C \subseteq \kappa $

so that for all

![]() $f,g \in [C]^\kappa _*$

, if for all

$f,g \in [C]^\kappa _*$

, if for all

![]() $\alpha < \kappa $

,

$\alpha < \kappa $

,

![]() $f(\alpha ) \leq g(\alpha )$

, then

$f(\alpha ) \leq g(\alpha )$

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) \leq \Phi (g)$

.

$\Phi (f) \leq \Phi (g)$

.

Adapting this argument, one can also show monotonicity for

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

when

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

when

![]() $\epsilon < \kappa $

.

$\epsilon < \kappa $

.

Theorem 5.7. Suppose

![]() $\kappa $

is a weak partition cardinal. For any

$\kappa $

is a weak partition cardinal. For any

![]() $\epsilon < \kappa $

and function

$\epsilon < \kappa $

and function

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, there is a club

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq \kappa $

so that for all

$C \subseteq \kappa $

so that for all

![]() $f, g \in [\kappa ]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

$f, g \in [\kappa ]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

![]() $\alpha < \epsilon $

,

$\alpha < \epsilon $

,

![]() $f(\alpha ) \leq g(\alpha )$

, then

$f(\alpha ) \leq g(\alpha )$

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) \leq \Phi (g)$

.

$\Phi (f) \leq \Phi (g)$

.

The last section will establish the strongest known continuity result for functions of the form

![]() $\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_* \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

from the strong partition relation on

$\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_* \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

from the strong partition relation on

![]() ${\omega _1}$

and a certain club selection principle. A certain club uniformization principle will be an important tool. Let

${\omega _1}$

and a certain club selection principle. A certain club uniformization principle will be an important tool. Let

![]() ${\mathsf {club}}_{\omega _1}$

denote the set of club subset of

${\mathsf {club}}_{\omega _1}$

denote the set of club subset of

![]() ${\omega _1}$

. The almost everywhere short length club uniformization principle at

${\omega _1}$

. The almost everywhere short length club uniformization principle at

![]() ${\omega _1}$

is the assertion that for all

${\omega _1}$

is the assertion that for all

![]() $R \subseteq [{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}_* \times {\mathsf {club}}_{\omega _1}$

which is

$R \subseteq [{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}_* \times {\mathsf {club}}_{\omega _1}$

which is

![]() $\subseteq $

-downward closed (in the sense that for all

$\subseteq $

-downward closed (in the sense that for all

![]() $\ell \in [{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}_*$

, for all clubs

$\ell \in [{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}_*$

, for all clubs

![]() $C \subseteq D$

, if

$C \subseteq D$

, if

![]() $R(\ell ,D)$

holds, then

$R(\ell ,D)$

holds, then

![]() $R(\sigma ,C)$

holds), there is a club

$R(\sigma ,C)$

holds), there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq {\omega _1}$

and a function

$C \subseteq {\omega _1}$

and a function

![]() $\Lambda : [C]^{<{\omega _1}}_* \cap \mathrm {dom}(R) \rightarrow {\mathsf {club}}_{\omega _1}$

so that for all

$\Lambda : [C]^{<{\omega _1}}_* \cap \mathrm {dom}(R) \rightarrow {\mathsf {club}}_{\omega _1}$

so that for all

![]() $\ell \in [C]^{<{\omega _1}}_* \cap \mathrm {dom}(R)$

,

$\ell \in [C]^{<{\omega _1}}_* \cap \mathrm {dom}(R)$

,

![]() $R(\ell ,\Lambda (\ell ))$

.

$R(\ell ,\Lambda (\ell ))$

.

Consider a function

![]() $\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1} \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

. Asking that there exists a

$\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1} \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

. Asking that there exists a

![]() $\delta < {\omega _1}$

so that

$\delta < {\omega _1}$

so that

![]() $\Phi (f)$

only depending on

$\Phi (f)$

only depending on

![]() $f \upharpoonright \delta $

for

$f \upharpoonright \delta $

for

![]() $\mu ^{\omega _1}_{\omega _1}$

-almost

$\mu ^{\omega _1}_{\omega _1}$

-almost

![]() $f \in [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_*$

is impossible in general. (For instance, consider

$f \in [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_*$

is impossible in general. (For instance, consider

![]() $\Phi (f) = f(f(0))$

. See Example 6.1.) Using the almost everywhere short length club uniformization at

$\Phi (f) = f(f(0))$

. See Example 6.1.) Using the almost everywhere short length club uniformization at

![]() ${\omega _1}$

, [Reference Chan and Jackson4] showed that functions

${\omega _1}$

, [Reference Chan and Jackson4] showed that functions

![]() $\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_* \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

do satisfy

$\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_* \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

do satisfy

![]() $\mu ^{\omega _1}_{\omega _1}$

-almost everywhere continuity where

$\mu ^{\omega _1}_{\omega _1}$

-almost everywhere continuity where

![]() $[{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_*$

is endowed with the topology generated by

$[{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_*$

is endowed with the topology generated by

![]() $\{N_\ell : \ell \in [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_*\}$

as a basis, where

$\{N_\ell : \ell \in [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_*\}$

as a basis, where

![]() $N_\ell = \{f \in [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_* : \ell \subseteq f\}$

for each

$N_\ell = \{f \in [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_* : \ell \subseteq f\}$

for each

![]() $\ell \in [{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}_*$

and

$\ell \in [{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}_*$

and

![]() ${\omega _1}$

is given the discrete topology. Explicitly, there is a club

${\omega _1}$

is given the discrete topology. Explicitly, there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq {\omega _1}$

so that for all

$C \subseteq {\omega _1}$

so that for all

![]() $f \in [C]^{\omega _1}_*$

, there exists an

$f \in [C]^{\omega _1}_*$

, there exists an

![]() $\alpha < {\omega _1}$

so that for all

$\alpha < {\omega _1}$

so that for all

![]() $g \in [C]^{\omega _1}_*$

, if

$g \in [C]^{\omega _1}_*$

, if

![]() $f \upharpoonright \alpha = g \upharpoonright \alpha $

, then

$f \upharpoonright \alpha = g \upharpoonright \alpha $

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

. [Reference Chan2] showed that the almost everywhere short length club uniformization at

$\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

. [Reference Chan2] showed that the almost everywhere short length club uniformization at

![]() ${\omega _1}$

can be used to get an even finer continuity result which asserts that there is a club

${\omega _1}$

can be used to get an even finer continuity result which asserts that there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq {\omega _1}$

so that for all

$C \subseteq {\omega _1}$

so that for all

![]() $f \in [C]^{\omega _1}_*$

and all

$f \in [C]^{\omega _1}_*$

and all

![]() $\alpha < {\omega _1}$

, if

$\alpha < {\omega _1}$

, if

![]() $\Phi (f) < f(\alpha )$

, then

$\Phi (f) < f(\alpha )$

, then

![]() $f \upharpoonright \alpha $

is a continuity point for

$f \upharpoonright \alpha $

is a continuity point for

![]() $\Phi $

relative to C. (For these results, the condition that

$\Phi $

relative to C. (For these results, the condition that

![]() $\Phi $

maps into

$\Phi $

maps into

![]() ${\omega _1}$

is generally necessary.)

${\omega _1}$

is generally necessary.)

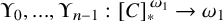

A natural question is whether

![]() $\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1} \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

satisfies any form of continuity in which

$\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1} \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

satisfies any form of continuity in which

![]() $\Phi (f)$

depends only on the behavior of f at finitely many locations on

$\Phi (f)$

depends only on the behavior of f at finitely many locations on

![]() ${\omega _1}$

. By the function from Example 6.1, it is impossible to have finitely many ordinals

${\omega _1}$

. By the function from Example 6.1, it is impossible to have finitely many ordinals

![]() $\delta _0, ..., \delta _{n - 1} < {\omega _1}$

which are independent of any input f so that

$\delta _0, ..., \delta _{n - 1} < {\omega _1}$

which are independent of any input f so that

![]() $\Phi (f)$

depends only on the behavior of f at these finitely many points. One can conjecture if there are finitely many continuity locations for

$\Phi (f)$

depends only on the behavior of f at these finitely many points. One can conjecture if there are finitely many continuity locations for

![]() $\Phi $

which do depend on f. That is, are there finitely many functions

$\Phi $

which do depend on f. That is, are there finitely many functions

![]() $\Upsilon _0, ..., \Upsilon _{n - 1}$

so that there is a club

$\Upsilon _0, ..., \Upsilon _{n - 1}$

so that there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq {\omega _1}$

with the property that for all

$C \subseteq {\omega _1}$

with the property that for all

![]() $f \in [C]^{\omega _1}$

, for all

$f \in [C]^{\omega _1}$

, for all

![]() $g \in [C]^{\omega _1}_*$

, if for all

$g \in [C]^{\omega _1}_*$

, if for all

![]() $i < n$

,

$i < n$

,

![]() $\sup (g \upharpoonright \Upsilon _i(f)) = \sup (f \upharpoonright \Upsilon _i(f))$

, then

$\sup (g \upharpoonright \Upsilon _i(f)) = \sup (f \upharpoonright \Upsilon _i(f))$

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

? This is also not possible. For each

$\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

? This is also not possible. For each

![]() $f \in [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_*$

, call an ordinal

$f \in [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_*$

, call an ordinal

![]() $\alpha $

a closure point of f if and only if for all

$\alpha $

a closure point of f if and only if for all

![]() $\beta < \alpha $

,

$\beta < \alpha $

,

![]() $f(\beta ) < \alpha $

or equivalently

$f(\beta ) < \alpha $

or equivalently

![]() $\sup (f \upharpoonright \alpha ) = \alpha $

. Let

$\sup (f \upharpoonright \alpha ) = \alpha $

. Let

![]() $\mathfrak {C}_f$

denote the club set of closure points of f. Let

$\mathfrak {C}_f$

denote the club set of closure points of f. Let

![]() $\Psi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_* \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

be defined by

$\Psi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_* \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

be defined by

![]() $\Psi (f) = \min (\mathfrak {C}_f)$

, that is, the smallest closure point of f. Example 6.3 shows that there is no collection of finite functions

$\Psi (f) = \min (\mathfrak {C}_f)$

, that is, the smallest closure point of f. Example 6.3 shows that there is no collection of finite functions

![]() $\Upsilon _0, ..., \Upsilon _{n - 1}$

which satisfies the proposed continuity property with respect to

$\Upsilon _0, ..., \Upsilon _{n - 1}$

which satisfies the proposed continuity property with respect to

![]() $\Psi $

. Closure points necessarily contain infinite information concerning f. The next result shows that closure points are the only obstruction to a

$\Psi $

. Closure points necessarily contain infinite information concerning f. The next result shows that closure points are the only obstruction to a

![]() $\mu ^{\omega _1}_{\omega _1}$

-almost everywhere continuity property asserting finite dependence:

$\mu ^{\omega _1}_{\omega _1}$

-almost everywhere continuity property asserting finite dependence:

Theorem 6.18. Assume

![]() $\mathsf {DC}$

,

$\mathsf {DC}$

,

![]() ${\omega _1} \rightarrow _* ({\omega _1})^{\omega _1}_2$

and that the almost everywhere short length club uniformization principle holds at

${\omega _1} \rightarrow _* ({\omega _1})^{\omega _1}_2$

and that the almost everywhere short length club uniformization principle holds at

![]() ${\omega _1}$

. Let

${\omega _1}$

. Let

![]() $\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_* \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

. There is a club

$\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_* \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

. There is a club

![]() $C \subseteq {\omega _1}$

and finitely many functions

$C \subseteq {\omega _1}$

and finitely many functions

![]() $\Upsilon _0,...,\Upsilon _{n - 1}$

so that for all

$\Upsilon _0,...,\Upsilon _{n - 1}$

so that for all

![]() $f \in [C]^{\omega _1}_*$

, for all

$f \in [C]^{\omega _1}_*$

, for all

![]() $g \in [C]^{\omega _1}_*$

, if

$g \in [C]^{\omega _1}_*$

, if

![]() $\mathfrak {C}_g = \mathfrak {C}_f$

and for all

$\mathfrak {C}_g = \mathfrak {C}_f$

and for all

![]() $i < n$

,

$i < n$

,

![]() $\sup (g \upharpoonright \Upsilon _i(f)) = \sup (f \upharpoonright \Upsilon _i(f))$

, then

$\sup (g \upharpoonright \Upsilon _i(f)) = \sup (f \upharpoonright \Upsilon _i(f))$

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

.

$\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

.

To put these results in context and discuss examples, one needs to consider the natural theories which possess combinatorially regular properties. Let

![]() $A \subseteq {{}^\omega \omega }$

. Consider a game

$A \subseteq {{}^\omega \omega }$

. Consider a game

![]() $G_A$

where two players take turns picking natural numbers to jointly produce an infinite sequence f. Player 1 is said to win

$G_A$

where two players take turns picking natural numbers to jointly produce an infinite sequence f. Player 1 is said to win

![]() $G_A$

if and only if

$G_A$

if and only if

![]() $f \in A$

. The axiom of determinacy, denoted

$f \in A$

. The axiom of determinacy, denoted

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

, asserts that, for all

$\mathsf {AD}$

, asserts that, for all

![]() $A \subseteq {{}^\omega \omega }$

, one of the two players has a winning strategy for

$A \subseteq {{}^\omega \omega }$

, one of the two players has a winning strategy for

![]() $G_A$

. Under

$G_A$

. Under

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

, the perfect set property and the Baire property hold for all sets of reals, and

$\mathsf {AD}$

, the perfect set property and the Baire property hold for all sets of reals, and

![]() ${\omega _1}$

and many other cardinals possess partition properties. Many weak versions of the continuity results mentioned here have been previously established for

${\omega _1}$

and many other cardinals possess partition properties. Many weak versions of the continuity results mentioned here have been previously established for

![]() ${\omega _1}$

and

${\omega _1}$

and

![]() $\omega _2$

under

$\omega _2$

under

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

. This paper evolved from attempts to establish continuity properties and cardinality computations at the most important weak and strong partition cardinals of determinacy.

$\mathsf {AD}$

. This paper evolved from attempts to establish continuity properties and cardinality computations at the most important weak and strong partition cardinals of determinacy.

See Section 2 for a summary of partition properties under

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

. Martin showed under

$\mathsf {AD}$

. Martin showed under

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

that

$\mathsf {AD}$

that

![]() ${\omega _1}$

is a strong partition cardinal and

${\omega _1}$

is a strong partition cardinal and

![]() $\omega _2$

is a weak partition cardinal which is not a strong partition cardinal. Jackson [Reference Jackson8] showed under

$\omega _2$

is a weak partition cardinal which is not a strong partition cardinal. Jackson [Reference Jackson8] showed under

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

that for all

$\mathsf {AD}$

that for all

![]() $n \in \omega $

,

$n \in \omega $

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_{2n + 1}^1$

is a strong partition cardinal and

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_{2n + 1}^1$

is a strong partition cardinal and

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_{2n + 2}^1$

is a weak partition cardinal which is not a strong partition cardinal. The next strong partition cardinal after

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_{2n + 2}^1$

is a weak partition cardinal which is not a strong partition cardinal. The next strong partition cardinal after

![]() ${\omega _1}$

is

${\omega _1}$

is

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_3^1 = \omega _{\omega + 1}$

. Kechris, Kleinberg, Moschovakis and Woodin [Reference Kechris, Kleinberg, Moschovakis and Hugh Woodin12] showed that

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_3^1 = \omega _{\omega + 1}$

. Kechris, Kleinberg, Moschovakis and Woodin [Reference Kechris, Kleinberg, Moschovakis and Hugh Woodin12] showed that

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

and the

$\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

and the

![]() $\Sigma _1$

-stable ordinals

$\Sigma _1$

-stable ordinals

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

of

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

of

![]() $L(A,\mathbb {R})$

for any

$L(A,\mathbb {R})$

for any

![]() $A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

are strong partition cardinals under

$A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

are strong partition cardinals under

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

.

$\mathsf {AD}$

.

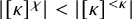

Previously known continuity results at

![]() ${\omega _1}$

and

${\omega _1}$

and

![]() $\omega _2$

heavily used determinacy methods. For instance, Kunen trees and Kunen functions ([Reference Jackson9] and [Reference Chan3]) are very important for many combinatorial questions at

$\omega _2$

heavily used determinacy methods. For instance, Kunen trees and Kunen functions ([Reference Jackson9] and [Reference Chan3]) are very important for many combinatorial questions at

![]() ${\omega _1}$

and for the description analysis below

${\omega _1}$

and for the description analysis below

![]() $\omega _\omega $

which leads to the strong partition property for

$\omega _\omega $

which leads to the strong partition property for

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_3^1 = \omega _{\omega + 1}$

. [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang6] and [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang5] Fact 2.5 used these Kunen functions to provide a very simple argument that every function

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_3^1 = \omega _{\omega + 1}$

. [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang6] and [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang5] Fact 2.5 used these Kunen functions to provide a very simple argument that every function

![]() $\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^\epsilon \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

with

$\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^\epsilon \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

with

![]() $\epsilon < {\omega _1}$

satisfies the almost everywhere short length continuity expressed in Theorem 3.7 and even the stronger version expressed in Theorem 3.9 (but only when the range of the function goes into

$\epsilon < {\omega _1}$

satisfies the almost everywhere short length continuity expressed in Theorem 3.7 and even the stronger version expressed in Theorem 3.9 (but only when the range of the function goes into

![]() ${\omega _1}$

). [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang6] used this result to show that

${\omega _1}$

). [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang6] used this result to show that

![]() $|[{\omega _1}]^\omega | < |[{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}|$

under

$|[{\omega _1}]^\omega | < |[{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}|$

under

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

. Using Martin’s ultrapower representation of

$\mathsf {AD}$

. Using Martin’s ultrapower representation of ![]() for each

for each

![]() $1 \leq n < \omega $

, [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang5] showed that

$1 \leq n < \omega $

, [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang5] showed that

![]() $[{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}$

does not inject into

$[{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}$

does not inject into

![]() ${}^\omega (\omega _\omega )$

. Using a variety of determinacy specific techniques (the full wellordered additivity of the meager ideal, generic coding arguments, Banach–Mazur games, Wadge theory and Steel’s Suslin bounding), [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang5] showed that

${}^\omega (\omega _\omega )$

. Using a variety of determinacy specific techniques (the full wellordered additivity of the meager ideal, generic coding arguments, Banach–Mazur games, Wadge theory and Steel’s Suslin bounding), [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang5] showed that

![]() $[{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}$

does not inject into

$[{\omega _1}]^{<{\omega _1}}$

does not inject into

![]() ${}^\omega \mathrm {ON}$

under

${}^\omega \mathrm {ON}$

under

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

and

$\mathsf {AD}$

and

![]() $\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

. (Note that Theorem 4.4 improved this result to just the hypothesis

$\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

. (Note that Theorem 4.4 improved this result to just the hypothesis

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

without

$\mathsf {AD}$

without

![]() $\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

.) Extending these methods to studying the next strong partition cardinal

$\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

.) Extending these methods to studying the next strong partition cardinal

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_3^1 = \omega _{\omega + 1}$

seems difficult. Although

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_3^1 = \omega _{\omega + 1}$

seems difficult. Although

![]() $\omega _{\omega + 1}$

has analogs of Kunen functions and generic coding functions ([Reference Kechris and Woodin13]) using supercompactness measures, there is no analog of the full wellordered additivity of the meager ideal which can be a major obstacle to generalizing results to

$\omega _{\omega + 1}$

has analogs of Kunen functions and generic coding functions ([Reference Kechris and Woodin13]) using supercompactness measures, there is no analog of the full wellordered additivity of the meager ideal which can be a major obstacle to generalizing results to

![]() $\omega _{\omega + 1}$

as observed by Becker at the end of [Reference Becker1]. Moreover,

$\omega _{\omega + 1}$

as observed by Becker at the end of [Reference Becker1]. Moreover,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

and the

$\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

and the

![]() $\Sigma _1$

-stable ordinals

$\Sigma _1$

-stable ordinals

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

(

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

(

![]() $A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

) are strong partition cardinals which are limit cardinals and cannot possess analogs of the desired Kunen functions. The methods for

$A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

) are strong partition cardinals which are limit cardinals and cannot possess analogs of the desired Kunen functions. The methods for

![]() ${\omega _1}$

are much less applicable here. Although,

${\omega _1}$

are much less applicable here. Although,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_3^1$

,

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_3^1$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

and

$\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

are important cardinals of determinacy possessing numerous scales and reflection properties, unlike

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

are important cardinals of determinacy possessing numerous scales and reflection properties, unlike

![]() ${\omega _1}$

, these properties do not seem to facilitate the analysis of cardinality. The pure combinatorial methods of Theorem 3.7, 4.4, 3.9, 5.3 and 5.7 are the only known method for establishing these properties for these important strong partition cardinals of determinacy.

${\omega _1}$

, these properties do not seem to facilitate the analysis of cardinality. The pure combinatorial methods of Theorem 3.7, 4.4, 3.9, 5.3 and 5.7 are the only known method for establishing these properties for these important strong partition cardinals of determinacy.

Corollary 3.10. Assume

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

. Suppose

$\mathsf {AD}$

. Suppose

![]() $\kappa $

is

$\kappa $

is

![]() ${\omega _1}$

,

${\omega _1}$

,

![]() $\omega _2$

,

$\omega _2$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_n^1$

for

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_n^1$

for

![]() $1 \leq n < \omega $

,

$1 \leq n < \omega $

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

where

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

where

![]() $A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

or

$A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

or

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

(assuming

$\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

(assuming

![]() $\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

). If

$\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

). If

![]() $\epsilon < {\omega _1}$

and

$\epsilon < {\omega _1}$

and

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, then there is a club

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, then there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq \kappa $

and finitely many ordinals

$C \subseteq \kappa $

and finitely many ordinals

![]() $\beta _0 < \beta _1 < ... < \beta _{p - 1} \leq \epsilon $

(where

$\beta _0 < \beta _1 < ... < \beta _{p - 1} \leq \epsilon $

(where

![]() $p \in \omega $

) so that for all

$p \in \omega $

) so that for all

![]() $f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

$f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

![]() $i < p$

,

$i < p$

,

![]() $\sup (f \upharpoonright \beta _i) = \sup (g \upharpoonright \beta _i)$

, then

$\sup (f \upharpoonright \beta _i) = \sup (g \upharpoonright \beta _i)$

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

.

$\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

.

Assume

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

. Suppose

$\mathsf {AD}$

. Suppose

![]() $\kappa $

is

$\kappa $

is

![]() ${\omega _1}$

,

${\omega _1}$

,

![]() $\omega _2$

,

$\omega _2$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_n^1$

for

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_n^1$

for

![]() $1 \leq n < \omega $

,

$1 \leq n < \omega $

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

, where

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

, where

![]() $A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

or

$A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

or

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

(assuming

$\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

(assuming

![]() $\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

). If

$\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

). If

![]() $\epsilon < \kappa $

with

$\epsilon < \kappa $

with

![]() ${\mathrm {cof}}(\epsilon ) = \omega $

and

${\mathrm {cof}}(\epsilon ) = \omega $

and

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, then there is a club

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, then there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq \kappa $

and a

$C \subseteq \kappa $

and a

![]() $\delta < \epsilon $

so that for all

$\delta < \epsilon $

so that for all

![]() $f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if

$f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if

![]() $\sup (f) = \sup (g)$

and

$\sup (f) = \sup (g)$

and

![]() $f \upharpoonright \delta = g \upharpoonright \delta $

, then

$f \upharpoonright \delta = g \upharpoonright \delta $

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

.

$\Phi (f) = \Phi (g)$

.

Corollary 4.6. Assume

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

. Suppose

$\mathsf {AD}$

. Suppose

![]() $\kappa $

is

$\kappa $

is

![]() ${\omega _1}$

,

${\omega _1}$

,

![]() $\omega _2$

,

$\omega _2$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_n^1$

for

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_n^1$

for

![]() $1 \leq n < \omega $

,

$1 \leq n < \omega $

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

, where

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

, where

![]() $A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

or

$A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

or

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

(assuming

$\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

(assuming

![]() $\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

). Then for any

$\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

). Then for any

![]() $\chi < \kappa $

,

$\chi < \kappa $

,

![]() $|{}^\chi \kappa | < |{}^{<\kappa }\kappa |$

and

$|{}^\chi \kappa | < |{}^{<\kappa }\kappa |$

and

![]() ${}^{<\kappa }\kappa $

does not inject into

${}^{<\kappa }\kappa $

does not inject into

![]() ${}^\chi \mathrm {ON}$

.

${}^\chi \mathrm {ON}$

.

Corollary 5.5. Assume

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

. Suppose

$\mathsf {AD}$

. Suppose

![]() $\kappa $

is

$\kappa $

is

![]() ${\omega _1}$

,

${\omega _1}$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_{2n + 1}^1$

for

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_{2n + 1}^1$

for

![]() $1 \leq n < \omega $

,

$1 \leq n < \omega $

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

where

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

where

![]() $A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

or

$A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

or

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

(assuming

$\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

(assuming

![]() $\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

). For any

$\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

). For any

![]() $\epsilon \leq \kappa $

and any function

$\epsilon \leq \kappa $

and any function

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, there is a club

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq \kappa $

so that for all

$C \subseteq \kappa $

so that for all

![]() $f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

$f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

![]() $\alpha < \epsilon $

,

$\alpha < \epsilon $

,

![]() $f(\alpha ) \leq g(\alpha )$

, then

$f(\alpha ) \leq g(\alpha )$

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) \leq \Phi (g)$

.

$\Phi (f) \leq \Phi (g)$

.

Corollary 5.8. Assume

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

. Suppose

$\mathsf {AD}$

. Suppose

![]() $\kappa $

is

$\kappa $

is

![]() ${\omega _1}$

,

${\omega _1}$

,

![]() $\omega _2$

,

$\omega _2$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_n^1$

for

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_n^1$

for

![]() $1 \leq n < \omega $

,

$1 \leq n < \omega $

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

where

$\boldsymbol {\delta }_A$

where

![]() $A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

or

$A \subseteq \mathbb {R}$

or

![]() $\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

(assuming

$\boldsymbol {\delta }^2_1$

(assuming

![]() $\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

). For any

$\mathsf {DC}_{\mathbb {R}}$

). For any

![]() $\epsilon < \kappa $

and

$\epsilon < \kappa $

and

![]() $\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, there is a club

$\Phi : [\kappa ]^\epsilon _* \rightarrow \mathrm {ON}$

, there is a club

![]() $C \subseteq \kappa $

so that for all

$C \subseteq \kappa $

so that for all

![]() $f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

$f,g \in [C]^\epsilon _*$

, if for all

![]() $\alpha < \epsilon $

,

$\alpha < \epsilon $

,

![]() $f(\alpha ) \leq g(\alpha )$

, then

$f(\alpha ) \leq g(\alpha )$

, then

![]() $\Phi (f) \leq \Phi (g)$

.

$\Phi (f) \leq \Phi (g)$

.

Determinacy provides examples to show that the hypothesis in Theorem 3.7 and Theorem 3.9 are generally necessary. Let

![]() $\Psi : [\omega _2]^{\omega _1} \rightarrow \omega _3$

be defined by

$\Psi : [\omega _2]^{\omega _1} \rightarrow \omega _3$

be defined by

![]() $\Phi (f) = [f]_{\mu ^{\omega _1}_1}$

, that is, the ordinal represented by f in the ultrapower

$\Phi (f) = [f]_{\mu ^{\omega _1}_1}$

, that is, the ordinal represented by f in the ultrapower ![]() of

of

![]() $\omega _2$

by the club measure on

$\omega _2$

by the club measure on

![]() ${\omega _1}$

.

${\omega _1}$

.

![]() $\Psi $

will not satisfy the weak or strong version of the almost everywhere short length continuity. (See Example 3.13.) Letting

$\Psi $

will not satisfy the weak or strong version of the almost everywhere short length continuity. (See Example 3.13.) Letting

![]() $\Upsilon : [\omega _2]^{{\omega _1} + \omega } \rightarrow \omega _3$

defined by

$\Upsilon : [\omega _2]^{{\omega _1} + \omega } \rightarrow \omega _3$

defined by

![]() $\Upsilon (f) = \Psi (f \upharpoonright {\omega _1})$

is an example of a function satisfying the weak short length continuity of Theorem 3.7 (note

$\Upsilon (f) = \Psi (f \upharpoonright {\omega _1})$

is an example of a function satisfying the weak short length continuity of Theorem 3.7 (note

![]() ${\mathrm {cof}}({\omega _1} + \omega ) = \omega $

) and does not satisfy the strong short length continuity of Theorem 3.9 (note that

${\mathrm {cof}}({\omega _1} + \omega ) = \omega $

) and does not satisfy the strong short length continuity of Theorem 3.9 (note that

![]() ${\omega _1} < {\omega _1} + \omega $

). In the two examples above, the range goes into

${\omega _1} < {\omega _1} + \omega $

). In the two examples above, the range goes into

![]() $\omega _3$

. Curiously, it is shown in [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang6] that every function

$\omega _3$

. Curiously, it is shown in [Reference Chan, Jackson and Trang6] that every function

![]() $\Phi : [\omega _2]^{\omega _1}_* \rightarrow \omega _2$

satisfies even the strong almost everywhere short length continuity property (despite

$\Phi : [\omega _2]^{\omega _1}_* \rightarrow \omega _2$

satisfies even the strong almost everywhere short length continuity property (despite

![]() ${\mathrm {cof}}({\omega _1})> \omega $

). This remarkable property is unique only to

${\mathrm {cof}}({\omega _1})> \omega $

). This remarkable property is unique only to

![]() $\omega _2$

and is made possible by Martin’s ultrapower representation of

$\omega _2$

and is made possible by Martin’s ultrapower representation of

![]() $\omega _2$

under

$\omega _2$

under

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

.

$\mathsf {AD}$

.

[Reference Chan and Jackson4] shows the almost everywhere short length club uniformization holds for

![]() ${\omega _1}$

under

${\omega _1}$

under

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

. (By a more general argument, [Reference Chan2] shows that nearly all known strong partition cardinals of

$\mathsf {AD}$

. (By a more general argument, [Reference Chan2] shows that nearly all known strong partition cardinals of

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

also satisfies this club uniformization principle.) By absorbing functions

$\mathsf {AD}$

also satisfies this club uniformization principle.) By absorbing functions

![]() $\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_* \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

into the inner model

$\Phi : [{\omega _1}]^{\omega _1}_* \rightarrow {\omega _1}$

into the inner model

![]() $L(\mathbb {R})$

which satisfies

$L(\mathbb {R})$

which satisfies

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

and

$\mathsf {AD}$

and

![]() $\mathsf {DC}$

, Theorem 6.18 implies the following holds in

$\mathsf {DC}$

, Theorem 6.18 implies the following holds in

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

.

$\mathsf {AD}$

.

Theorem 6.22. Assume

![]() $\mathsf {AD}$

. Let

$\mathsf {AD}$

. Let