Introduction

Building a modern international order is an ongoing task in which we are all protagonists.Footnote 1

–Mr. Mauricio Macri, President of the Argentine Republic, UNGA, 20 September 2016.

Scholars and practitioners have sought to understand how the values at the core of international orders are evolving,Footnote 2 including shifts in the social significance of liberal ideals.Footnote 3 International Relations (IR) scholarship has often focused on trends within and between great and rising powers. Yet the support, or lack of support, of the world’s large number of small- and medium-sized states is also integral.Footnote 4 This study presents new evidence of how key characteristics, efforts and aspirations with which state representatives in the United Nations (UN) express their states’ own positive social identities have gained, lost or retained salience since the end of the Cold War.

Building on scholarship that emphasizes shared identities and aspirations at the basis of international orders, this approach adds to insights about the ‘distribution of identities across states’ (Allan, Vucetic and Hopf Reference Allan, Vucetic and Hopf2018: 850). Identity ‘is likely to be the major defining feature of new orders’, argues Trine Flockhart, who also highlights that shared identities, including norms and domestic governance arrangements, contribute to the internal cohesion of an international society (Reference Flockhart2016: 24, 14-15 ; see also Reus-Smit Reference Reus-Smit2009). The distribution of identities in an international society notably comprises aspirations (Finnemore and Jurkovich Reference Finnemore and Jurkovich2020), that is, prevailing ideas not only about who actors are but also who they are becoming (Towns Reference Towns2010; Hall Reference Hall, Hall and du Gay1996: 4).

An aim of this article is to analyze relations between (a) issue salience and (b) the salience of normative status dimensions, which have not yet been studied in depth. Salience refers to social significance within a society at a given point in time. Normative status dimensions refer here to the fluctuating, collective ideational bases (e.g., social categories) on which actors convey positive social identifications in an international society. Understanding their dynamics is important because they can potentially contribute to improving inhabitants’ quality of life.Footnote 5 For example, if a status dimension based on social development and fighting poverty is highly salient in international society, this can encourage states and other actors to enhance domestic-level efforts and cooperation to fulfill basic needs and improve health care, education and social protection programs for all. In other words, studying changes in the salience of social identifications in an international society offers insights into the evolution of informal groups and prospects for collective action. To help visualize the concept of a salient normative status dimension, an analogy can be made to magnets with different forces of attraction. How strong is the pull of a specific value-based magnet across an international society in different years?

Normative status dimensions differ from related concepts such as social stratification,Footnote 6 statusFootnote 7 or norms.Footnote 8 Only some, not all, international norm sets become relevant for states’ positive social identifications.Footnote 9 Akin to ‘dimensions of differentiation’ (Donnelly Reference Donnelly2011: 153), normative status dimensions represent fluid informal groups rather than hierarchies. As norms shape and are shaped by differentiation processes (Towns Reference Towns2010: 44; Towns and Rumelili Reference Towns and Rumelili2017), these concepts intersect yet are distinct. Like norms, status dimensions are situated at the structural, not the unit, level. They are co-constituted among the full society, including major powers, international organizations (IOs), smaller states and others. Scholarship on status in world politics typically considers status as multidimensional, with both material and ideational components (e.g., Larson, Paul and Wohlforth Reference Larson, Paul, Wohlforth, Paul, Larson and Wohlforth2014; Larson and Shevchenko Reference Larson and Shevchenko2010; Pouliot Reference Pouliot2016). This study presents a complementary picture from a different angle. Rather than observing rankings or external recognition by powerful states, international organizations or others, normative status dimensions are observed here by aggregating state representatives’ own expressions of their states as associated with certain social categories. This is a self-referential approach consistent with the social-psychological concept of self-categorization (Oakes Reference Oakes and Turner1987; Turner Reference Turner and Turner1987; Hogg and Abrams Reference Hogg and Abrams1998).

Intuitively, one might expect to observe correlation between the salience of an issue and of a related normative status dimension (i.e., how widespread states’ expressions of positive social identity are on an issue) in the same venue, but this is not necessarily the case. For example, trends in the percentage of state representatives expressing that fighting climate change is an important general issue may or may not correlate with the percentage of those expressing that their states take (or will take) domestic-level action to fight climate change. This is discussed in greater detail below. This study highlights significant dynamics that would be overlooked by scholarship that relies exclusively on automated text analysis.

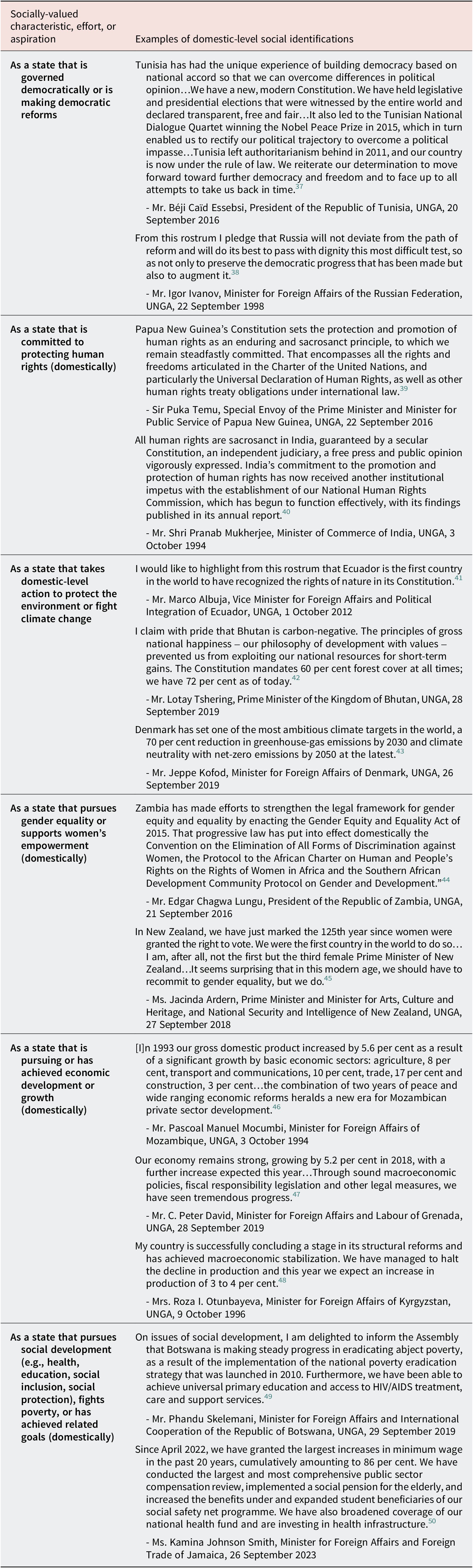

Empirically, the dynamics of salient normative status dimensions are studied here by measuring and aggregating the domestic or national level characteristics, efforts and aspirations that state representatives communicate to be valued, with reference to their own states. This builds on a method I developed to evaluate shifts in the salience of democratic governance as a basis of social status and as an issue in the UN General Assembly (UNGA) General Debate (GD) (Hecht Reference Hecht2016).Footnote 10 Here, I conduct manually-coded content analysis (3,142 speeches) of all state representatives’ speeches in the UNGA GD in seventeen years between 1978 and 2023 to compare trends in the salience of six prevalent social categories: as leaders articulate that their states (domestically) (a) are governed democratically or are making democratic reforms, (b) are committed to protecting human rights, (c) empower women or strive for gender equality; (d) take domestic-level action to protect the environment or fight climate change; (e) pursue or achieve economic development or growth or (f) pursue social development or fight poverty (e.g., improve health care, education, social protection). These include the most frequently articulated social categories related to national-level characteristics, efforts and goals in this venue, with variation, in these years. I also analyze and compare the trends with quantitative measures of issue salience derived from automated text analysis of the full corpus of GD statements, as will be further discussed. A finding is that there has been an expansion, rather than replacement, of the domestic-level components that state representatives express as positive in relation to their own states in the UNGA GD.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. The next two sections present the conceptual framework, building on constructivist IR scholarship and social psychology. Then I introduce a matrix to interpret the range of possible relations between the salience of issues and of normative status dimensions in a given venue. The following section describes the methods and case selection. In the empirical section, I present findings from the UNGA GD and analyze patterns of relations between issue salience and status dimension salience in the six above-mentioned social categories. Implications for international order are also discussed. The conclusion summarizes, considers policy implications and suggests directions for future research.

Conceptual framework: Changes in the salience of normative status dimensions and values in international orders

Why can we learn about changes in the ideational foundations of international orders by studying the dynamics of salient normative status dimensions? A widely cited definition of international order refers to a pattern of relations among states and other actors that ‘sustains the elementary or primary goals or the society of states, or international society’ (Bull Reference Bull1977: 8; Flockhart Reference Flockhart2016). These social purposes are dynamic and evolve with an order’s supporting rules, norms and institutions, as well as the distribution of power and material resources (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2018; Lake et al. Reference Lake, Martin and Risse2021). By focusing on changes in normative structures, this article addresses one piece of the broader question of how international orders are evolving.

The two above-mentioned concepts – social purposes of an international society and normative status dimensions – have some affinities and overlap, yet the former is broader in scope. Salient normative status dimensions represent the strength of actors’ (states’) interest in associating with an informal group in which related values and aspirations are viewed as positive (cf. Ellemers Reference Ellemers2017; Hurd Reference Hurd2007: 59; Turner Reference Turner and Turner1987; Finnemore and Jurkovich Reference Finnemore and Jurkovich2020: 761). Shifts signify changes in the appeal of certain social categories, which are linked to prevailing ideas about the principles of legitimacy in a society at specific points in time.

Social purposes mentioned by diplomats in the UN system in the first decades after its founding in 1945, in addition to those in the UN Charter’s Preamble, included preventing the outbreak of a highly destructive third world war and ending colonialism and apartheid. Many statespersons considered human rights vital to achieving these goals, as well as goals in their own right. Social purposes have also included preserving an international society and its members via principles such as non-intervention and territorial integrity (Reus-Smit Reference Reus-Smit2009). Even prior to 1989, some identified liberal values as salient among states in global international society, despite the concurrent East–West contestation. For example, Inis Claude argued in 1966 that democratic principles had achieved ‘widespread acceptance as the criterion of legitimate governance within the state’ (369). And in 1986, R.J. Vincent argued that ‘human rights are a prominent, if not the dominant, criterion’ of international legitimacy (131).

After the end of the Cold War, social purposes of global international society became more liberal, as several scholars have argued, as states’ participation in an inner core of international society became increasingly associated with certain domestic-level characteristics, including democratic governance, human rights and participating in the global economy (Clark Reference Clark2005: 40, 188; Hurrell Reference Hurrell2007; Donnelly Reference Donnelly2011; Pouliot Reference Pouliot2016; Viola Reference Viola2020). Narratives about the origins of the ‘liberal international order’ (LIO) explain that as the (Western) liberal order expanded globally in the 1990s, governance within states increasingly became a ‘subject of legitimate international concern’ (Hurrell Reference Hurrell2007: 143; Jahn Reference Jahn2018; Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2018: 9–10). Changing ideas about moral purposes of the state-qualified sovereign equality (Reus-Smit Reference Reus-Smit2009: 159, 164; Clark Reference Clark2005). With prominent UN-sponsored global conferences in the 1990s, international norms evolved to emphasize the well-being of individuals. At the same time, states’ domestic-level characteristics and goals became increasingly articulated in multilateral diplomacy.

In recent years, debates about the ‘end’ of liberal international order and its prospects have raised questions about the future place and social significance of liberal values, including democracy and human rights (e.g., Mearsheimer Reference Mearsheimer2019; Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2018, Reference Ikenberry2020; Allan et al. Reference Allan, Vucetic and Hopf2018; Reus-Smit Reference Reus-Smit2021; Barnett Reference Barnett2021; Flockhart Reference Flockhart2022). Some have diagnosed a ‘crisis of social purpose’ of liberal internationalism (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2018: 10), given the rise of nationalist populist parties in major democratic states, external challenges from major authoritarian states and declining ‘Western’ power. Analyses in early 2025 are even more pessimistic. According to David Petrasek, however, liberal ideals may be somewhat resilient because leaders from multiple world regions actively contributed to the emergence and institutionalization of global commitments (e.g., human rights) (Reference Petrasek2019: 103–4; see also Acharya Reference Acharya2016).

Thus, it is useful to gain additional empirical knowledge from the perspectives of all the world’s states about the extent of shifts in various values and aspirations – old and new – that have been expressed as integral to international orders. Orders require legitimation of their social purposes, which ‘must be consistent with the distribution of identity’ (Allan et al. Reference Allan, Vucetic and Hopf2018: 839), including aspirations. How central have democracy and human rights been in the global distribution of states’ social identifications, and to what extent are new social identifications gaining significance? Few scholars of international order, for example, have considered poverty eradication as a central social purpose, despite its prominence as a ‘supernorm’ since the 2000s (see Fukuda-Parr and Hulme Reference Fukuda-Parr and Hulme2011).

There are also implications for leadership in international society. As Deborah Larson reminds us, ‘a leader of the international system must have followers’, which depends on an ideology that resonates widely (Reference Larson2020: 183; see also Reus-Smit Reference Reus-Smit2021). As different normative status dimensions become salient, this suggests a more heterogeneous leadership in global international society, with variation in different issue areas. Despite international orders’ (and leaders’) need for broad appeal in a range of policy fields, less attention has been paid to trends in the (global) appeal side of the equation.

Salient normative status dimensions and domestic-level social identifications

Many values or aspirations are concurrently available for use in communicating a state’s positive social identity (Hogg and Abrams Reference Hogg and Abrams1998: 17; Pouliot Reference Pouliot2016). By selecting a particular characteristic or goal, diplomats categorize their state as belonging to a group of states with similar, valued attributes or priorities (Barker Reference Barker2001: 35; Hall Reference Hall, Hall and du Gay1996: 2). They also further legitimate, reinforce or alter the salience of these characteristics or aspirations (Schneider, Nullmeier and Hurrelmann Reference Schneider, Nullmeier, Hurrelmann, Hurrelmann, Schneider and Steffek2007; Hurd Reference Hurd2011: 587).

Social identity is ‘a shared/collective representation of who one is and how one should behave’ (Hogg and Abrams Reference Hogg and Abrams1998: 3). State representatives’ social identity expressionsFootnote 11 are communicative displays of (states’ own) characteristics, efforts or goals which generally correspond with group norms. For example, identifying his state in terms of democracy and human rights, Mr. David Kabua, President of the Republic of the Marshall Islands, stated in 2021: ‘Throughout my nation’s young history, we have remained true to the pursuit of an independent and free democracy, which assures basic and human rights’.Footnote 12 Such self-referential expressions hold significance, according to social psychologists, as actors ‘are generally less willing to be considered in terms of categorizations that are ascribed to them or imposed upon them by others than to being included in groups whose membership they have earned or chosen’ (Ellemers, Spears and Doosje Reference Ellemers, Spears and Doosje2002: 171).

Whether states’ social identity expressions are sincere, accurate or idealized does not undermine their political relevance (Hall Reference Hall, Hall and du Gay1996: 4; Crawford Reference Crawford2002: 125–28; Hurd Reference Hurd2011: 591–96; Johnstone Reference Johnstone2011: 23–24; Abulof and Kornprobst Reference Abulof and Kornprobst2017: 10). Even insincere claims signify and perpetuate a social category. Diplomats claiming to represent a particular type of state (even if idealized), communicate how they would like their state to be recognized and treated (Bailes Reference Bailes, Daase, Fehl, Geis and Kolliarakis2015: 261–62) in a certain social group and context.

Domestic-level social identifications are communicative displays of states’ national (or sub-national) shared characteristics, efforts or aspirations. ‘A country’s international reputation is largely dependent on its domestic health’,Footnote 13 stated Mr. Jan Kavan, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic, in 1998. Yet the attributes of ‘domestic health’ that diplomats choose to showcase vary over time. An example in the issue area of social development was made by Mrs. Alicia Bárcena Ibarra, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Mexico, in 2023, who stated that in Mexico, ‘5.1 million people have been lifted out of poverty in recent years. We witnessed the largest increase in the minimum wage in our history and developed an elaborate network of social programmes that extend rights to the entire population.’Footnote 14

When aggregated, these expressions reflect the appeal of certain informal groups at specific points in time.Footnote 15 Even if actors may hold different ideas about their meaning and interpretation, international norms and goals that have been endorsed by consensus and institutionalized in the UN system provide language with which some diplomats speak about goals for their states and others, especially in multilateral venues with international and domestic audiences (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004; Towns Reference Towns2010; Pouliot Reference Pouliot2016; Ellemers Reference Ellemers2017; Hecht and Steffek Reference Hecht and Steffek2024). Yet not every international norm set becomes relevant for states’ self-representations and some status dimensions become salient in the absence of codified international norms.Footnote 16

The concept of normative status dimensions helps to visualize changes in informal groups, which evolve with shared positive social identifications in an international society. Some statements convey explicitly that domestic-level social identifications connect a state to an informal group of states that share certain characteristics, policies or priorities. For example, Ms. Suzi Carla Barbosa, Minister for Foreign Affairs, International Cooperation and Communities of the Republic of Guinea-Bissau, stated in 2019:

As a champion of gender equality, Guinea-Bissau…wishes to share with the General Assembly the historical adoption of the law of parity by the People’s National Assembly in Guinea-Bissau in 2018, which established women’s level of representation in elected positions at 36 per cent. As a result, Guinea-Bissau became part of a group of more than 80 countries that have adopted corrective and temporary measures to increase the participation of women in politics and decision-making.Footnote 17

Expressions of states’ own domestic achievements or commitments are more meaningful indicators of social identification than declaring a value important for other actors (e.g., for a state’s neighbors, their region or the UN system). By analogy, at the individual level, if a leader self-identifies as an environmentalist and tells a large audience that she composts or volunteers to remove plastics from beaches and parks, this is a more meaningful, personal commitment to the environment than if she praises her neighbors for installing solar panels or argues that the government should invest more in renewable energy. An example in the issue area of environmental protection, Mr. Enrique Castillo, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Costa Rica, stated in the General Debate in 2012:

Costa Rica adopted sustainability as a development model several years ago and has embraced its national responsibilities on the matter. We have increased our forest coverage. We generate 90 per cent of our energy from renewable sources. Over 25 per cent of our territory is made up of national parks, and we have adopted the goal of becoming a carbon-neutral country by 2021.Footnote 18

As an example in the policy area of social development and fighting poverty, in 2018, Mr. Wang Yi, State Councillor and Minister for Foreign Affairs of the People‘s Republic of China, stated:

In the past 40 years, more than 700 million individuals in the Chinese population have been lifted out of absolute poverty, which accounts for more than 70 per cent of the global totals for the same period. A basic medical insurance system has been set up to cover China’s 1.35 billion people, and a social pension network accessible to more than 900 million people has been fully implemented.Footnote 19

As suggested above, the salience of a normative status dimension can be gleaned by aggregating the percentage of state representatives’ statements that mention their states’ own domestic-level efforts, achievements, characteristics, policies or aspirations in different issue areas in a given venue and point in time. This requires manual coding to distinguish from the broader indicator of issue salience. Issue salience comprises a wider range of expressions beyond domestic-level social identifications, for example, when a diplomat conveys a state’s support for certain shared priorities or norms in its foreign policy, either bilaterally or as an issue for multilateral or UN action beyond its borders, as well as vague expressions of support for (or contestation of) an issue. This is further discussed in the methods section below. Differentiating between these two indicators is important because normative status dimension salience provides more meaningful insights into changes in the values underpinning an international order. Although not every state representative is expected to articulate domestic-level social identifications in each issue area in the UNGA GD each year, a large and significant number articulate several of them, and by viewing patterns in the combination of these statements over time, we gain knowledge about changes in the salience of different status dimensions in international society.

State representatives highlight aspects of their states’ (positive) social identities in UN venues for various reasons. Some are proud of their domestic achievements or reforms. Some explain why they make excellent partners for cooperation, are good destinations for business and investment or deserve integration in regional or other groups. ‘Aspiring group members hoping to earn trust and inclusion often express characteristic group values most strongly, as a pledge of loyalty to the group’, argues social psychologist Naomi Ellemers (Reference Ellemers2017: 28, 14). Some would like to be viewed as leaders in the related issue areas. Others convey their right to govern (Barker Reference Barker2001), to sovereignty (Franck Reference Franck1990), to reduce stigma (Adler-Nissen Reference Adler-Nissen2014) or to lift sanctions. When describing their national efforts or priorities in the UNGA, state representatives often reaffirm their commitment to upholding the values and purposes of the United Nations or to achieving collective goals endorsed at major global conferences. Some state representatives also highlight their domestic efforts and goals in response to major international, regional or domestic events. Systematic explanation of states’ motivations, however, is beyond this article’s scope, as the focus here is on trends at the structural level.

Historically, some international norms for states’ domestic-level behavior differentiated between developing and industrialized countries. Agendas such as the Millennium Development Goals and the Kyoto Protocol assigned different roles to different types of states. These roles have been reflected in discourse. Several industrialized states have tended to focus on global or regional policy rather than national policy in their GD statements. However, some shifts in discursive patterns could be expected, for example, if their standing in certain issue areas comes into question, the categories become blurry, during increased contestation (Oakes Reference Oakes and Turner1987; Ellemers et al. Reference Ellemers, Spears and Doosje2002) or when international norms apply to new groups of actors, such as the shift in the domestic-level applicability of the SDGs beyond developing countries to all states.

To summarize, an empirical aim of this study is to illustrate and compare changes in the salience of six normative status dimensions (and related values at the foundation of international order) by measuring the extent to which state representatives express positive domestic-level social identifications on the basis of these social categories in the UNGA GD over time. An analytical objective is to improve understanding of relations between the salience of issues and status dimensions, to which we now turn.

Relations between issue salience and (normative) status dimension salience

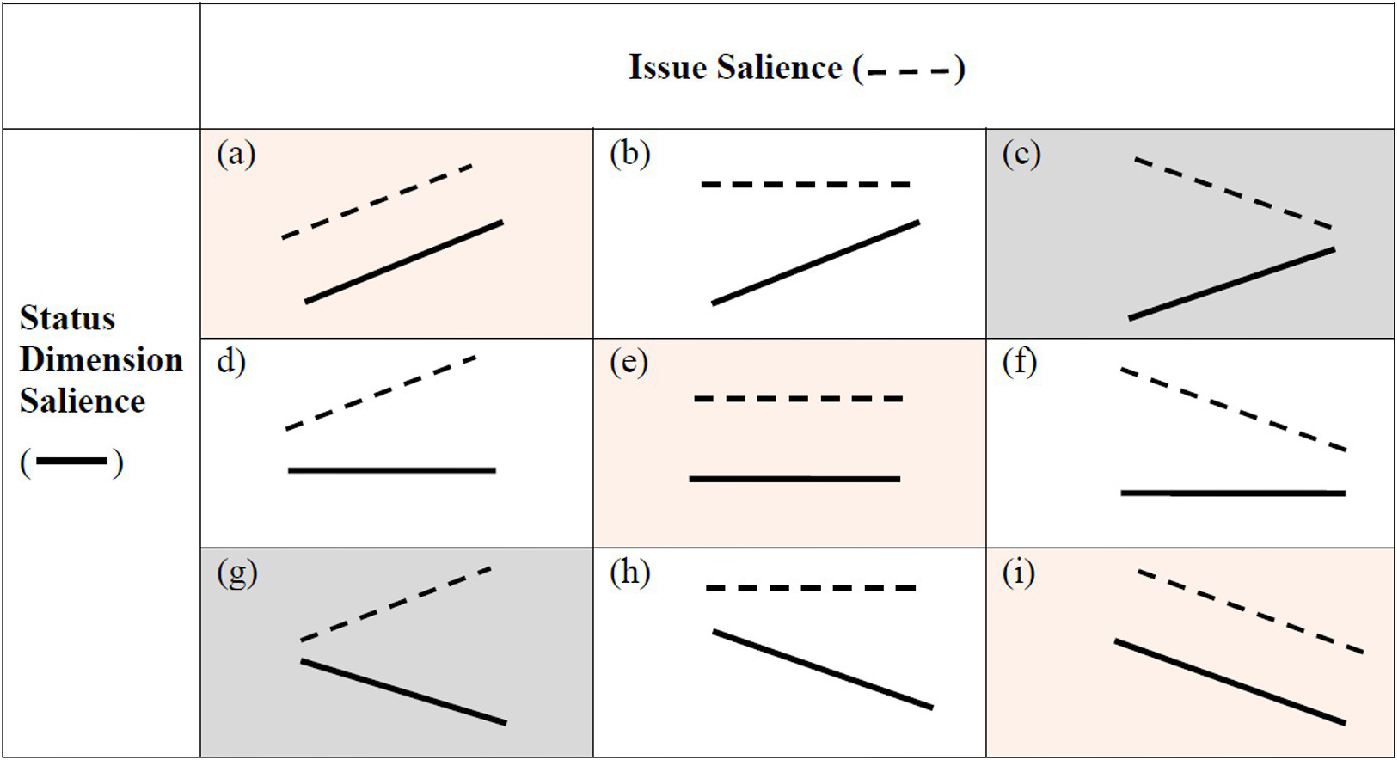

Table 1 presents a schematic overview of nine possible relations between issue salience (i.e., how widespread is discussion of certain issues across a society) and the salience of related status dimensions (i.e., the extent to which state representatives express domestic-level characteristics, efforts, goals or achievements related to these issues) in a given venue at different points in time. This analytical differentiation is useful because the latter (solid lines) provides unique insights into trends in the strength of values underpinning an international order. Issue salience (dashed lines) can be rapidly calculated with corpus linguistic tools and automated frequency measures. However, automated methods cannot capture the sometimes significantly different patterns of status dimension salience, which require manual coding to reveal.

Table 1. Overview of possible relations between issue salience and status dimension salience (in the same issue area) over a period of time. Light shaded boxes (a, e and i): show both types of salience with a strong correlation. White boxes (b, d, f and h) show decorrelation. Darker shaded boxes (c and g) represent anti-correlation.

One might expect the salience of issues and related status dimensions to be correlated, as shown in the light-shaded boxes (a, e and i). That is, one might expect states’ social identifications (e.g., as states that fight poverty) to rise or fall in parallel with the salience of this issue in a particular venue over time. However, correlation cannot be assumed. Notably, issue salience and status dimension salience can each independently take three values over time – rising, stable or falling. Table 1 visualizes possible combinations.

Why is this important? Activists in a particular issue area would like both issue salience and status dimension salience to be high, but the latter is viewed as key. According to Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, when states are trying to raise their status, civil society may have more leverage (Reference Keck and Sikkink1998: 29). Social psychologists also note that when a particular social category is salient, actors are more likely to think of themselves in these terms and cooperation or contestation on related topics is more likely (see Turner Reference Turner and Turner1987; Ellemers Reference Ellemers2017). If issue salience is high while status dimension salience is low in a particular issue area, advocacy efforts may be less successful than if both are high.

Relations between issue salience and status dimension salience can be grouped according to their correlation at different points in time. The first pattern is that they may be strongly or moderately correlated (boxes, a, e and i). A second pattern is that they may be decorrelated. Scenarios of decorrelation are shown by the white boxes (b, d, f and h) in Table 1. Box b shows rising status dimension salience while issue salience remains constant; boxes d and f show constant status dimension salience while issue salience increases or decreases; and box h shows declining status dimension salience while issue salience holds constant. Decorrelation represents a disconnect between the prevalence of discussed topics and their resonance for positive social identifications in a given venue. A final pattern is the possibility of anti-correlation, represented by the darker boxes c and g.

Why would we observe weak correlation, decorrelation or inconsistency over time? Some issues become significant for states’ positive domestic-level social identifications only gradually, others emerge more quickly, some lose appeal and some fail to become fashionable. Salient issues among states in the UN system may (or may not) resonate as aspects of domestic-level social identifications. Boxes b and d represent the curious scenario of unfulfilled potential for a salient issue to become a salient status dimension. Status dimension salience can increase, as in box b, for example, if processes that shape status markers become more inclusive of the full group or if institutionalization and implementation in an issue area become more robust.

Alternatively, decorrelation might be viewed as resulting from some states’ strategic use of non-self-identification or silence as an image-management tactic, partly to avoid calling attention to lower-than-expected performance consistent with certain normative values. This would, however, still be compatible with the analysis presented here. Whether for strategic or other motives, the characteristics, efforts and aspirations that states showcase vary over time. Significant shifts in the percentage of states that express different social identifications in a given year, as in the strategy of social creativity, will be visible in the comparative empirical data in the figures in the next section when these changes occur between the six selected categories. In addition, even if a state does not fully embody the characteristic in question, state representatives often reference future-looking policy goals or aspirations, rather than past or present achievements (see Finnemore and Jurkovich Reference Finnemore and Jurkovich2020), which lowers the bar to associating with certain social categories.

Social psychologists suggest that the salience of a social category among individuals is affected by ‘accessibility’ of the category, including utility and actors’ ‘fit’ with the category, as well as actual and anticipated changes in the relative prestige of prototypical actors (Oakes Reference Oakes and Turner1987; Ellemers et al. Reference Ellemers, Spears and Doosje2002). Major events (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) generate widespread attention to related issues and may correspond with short-term increases in domestic-level social identifications. However, disentangling speakers’ motivations is beyond this article’s scope. The bottom row (boxes g. h and i) may result from contestation or competing agendas. Understanding the abstract patterns in Table 1 can benefit from comparison with empirical evidence.

Methods and case selection

The United Nations General Assembly, with its wide membership and broad policy portfolio, has been a highly visible global venue for debates related to international legitimacy (Claude Reference Claude1966; Vincent Reference Vincent1986: 62; Steffek Reference Steffek2003; Binder and Heupel Reference Binder and Heupel2015). The General Debate (GD), which opens the annual sessions of the UNGA each September in New York, is uniquely apt for studying changes in the salience of social identifications and issues among the world’s states, given its significance as a symbolic site of multilateral diplomacy in which state representatives are allotted equal time to speak about topics of their choice (Hecht Reference Hecht2016; Mitrani Reference Mitrani2017; Baturo, Dasandi and Mikhaylov Reference Baturo, Dasandi and Mikhaylov2017; Kentikelenis and Voeten Reference Kentikelenis and Voeten2021; Chelotti, Dasandi and Mikhaylov Reference Chelotti, Dasandi and Mikhaylov2022; Hecht and Steffek Reference Hecht and Steffek2024; Adams and Mitrani Reference Adams and Mitrani2024). In their broadly publicized GD speeches, the Heads of State or Government, foreign ministers and other high-level state representatives articulate their states’ global and regional foreign policy interests as well as domestic-level priorities, aspirations and achievements in a wide range of policy areas. They also express grievances and, inter alia, advocate issues they consider important for the future work of the UN. Notably, these statements contain expressions of states’ positive social identities.

Performances in the General Debate are particularly informative because this venue offers rare opportunities for states of all sizes to present themselves and gain the attention of global and domestic audiences. According to Claude, statespersons are ‘keenly conscious of the need for approval by as large and impressive a body of other states as may be possible, for multilateral endorsement of their positions’ (1966: 370). Leaders’ addresses in the annual GD have an open character, as their content is unrestricted. Their performative nature interacts with features of the venue (see also Wiseman Reference Wiseman2015: 327–28; Pouliot Reference Pouliot2016; Neumann and Sending Reference Neumann and Sending2021), such as its global scope, high visibility and connections with multiple communities of practice. Moreover, from the perspective of many smaller states, the UNGA holds procedural legitimacy, given its decision-making based on formal sovereign equality (one state, one vote).

Thus, the UNGA GD is comparatively well positioned to reveal patterns in aggregate social identifications across (global) international society. Other UN organs such as the Security Council and Economic and Social Council do not comprise the full UN membership. The UNGA also has a broader policy portfolio than other UN entities, such as the World Health Organization and the United Nations Development Programme, or the World Bank. As the UN’s mandate ranges from peace and security, economic and social development, human rights, sustainability and beyond, the speeches in the UNGA potentially cover a wider range of issues than in IOs with a narrower policy mandate. With limited time to speak, state representatives can only mention their states’ highest priorities in a given year. These speeches are valuable for improving our understanding of changes in the social significance of articulated values across a collective that approximates international society. To analyze these shifts and to produce the graphs that appear in the next section, the following methods were employed.

First, I manually coded 3,142 UNGA General Debate speeches, representing all statements delivered by each state representative in 1978, 1982, 1994, 1996, 1998, 2002, 2004, 2008, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021 and 2023 from the Provisional Verbatim records. Only with manual coding is it possible to identify the domestic-level social identifications invoked by state representatives and to differentiate these from general references to issues, which can be captured with automated text analysis. In each of the full speeches, I coded all instances in which state representatives associated their country’s own domestic-level characteristics, efforts, achievements, policies or aspirations explicitly with any of the six selected social categories: (1) democracy; (2) human rights; (3) gender equality and empowering women; (4) environmental protection and climate action; (5) economic development and growth and (6) social development and fighting poverty. Coding decisions entailed determining if each speech included (or did not include) at least one reference to a state’s positive national, domestic-level characteristics, efforts or aspirations in any of the six categories, together with contextual reference to the state itself. Appendix 1 presents coding examples in each category.

The six selected social categories (1–6 above) are broad enough that any diplomat could invoke them in relation to their state if they wished. These categories include the most frequently articulated domestic-level social identifications in the UNGA since the end of the Cold War. They also exhibit significant variation over time, as well as a range of relations to (liberal) international order. For each speech, I initially coded for other categories that are not included here. The omitted categories were either less frequently mentioned or limited to certain types of states (e.g., fight corruption, terrorism or trafficking of weapons or drugs domestically, are a ‘peace-loving state’, are a small island developing state or have renounced nuclear weapons) or represent international-level social identifications (e.g., contribute to UN peace operations, provide 0.7% of GNI in official development assistance), which are different in type and entail different dynamics than the selected domestic-level social identifications that are potentially accessible to states of all types and are presented below. The other categories remain interesting topics for future analysis.

Second, I calculate the percentage of state representatives in a given year who make at least one reference during their GD speech to any of the six selected social categories, in relation to their domestic context. I calculate percentages in order to illustrate the social significance across the full composition of the UNGA (Hecht Reference Hecht2016; Hecht and Steffek Reference Hecht and Steffek2024). This method controls for variation in speech length both across years and within the same year.Footnote 20 It also controls for increases in the number of state representatives speaking in the UNGA GD between 1978 and 2023.Footnote 21 This builds on the logic that if a state representative prioritizes associating their state with a particular social category in the GD in a given year, they are likely to find the time in their speech to make at least one reference, regardless of other priorities or speech length. Some speakers exceed the voluntary time guidelines and their speeches contain more words than others (see Ghanem and Speicher Reference Ghanem and Speicher2017; Binder and Heupel Reference Binder and Heupel2015). This indicator reflects the distribution of social identifications across the international society of states as a whole. Alternative indicators, such as normalized, average references per year or overall frequency can overestimate the relative significance in years with longer statements (prior to 2001 and 1997). I also disaggregate indicators of status dimension salience by the five UN regional groupsFootnote 22 to compare the global average with trends in different world regions.

Third, for the broader measure of issue salience in the UNGA GD, I calculate the percentage of speakers making at least one reference per speech to the related issue as defined by selected search terms, using the UNGA GD dataset compiled by Baturo et al.Footnote 23 This dataset consists of machine-readable text files organized by year and country. Each speech was scanned for at least one mention of the search terms in a case-insensitive manner in the years 1978–1982 and 1990–2023 using a Python script. For this, no additional pre-processing was needed. The search terms for the automated text analysis are listed in the footnotes in the following section. I selected these search terms during the above-described manual coding process and also coded within each speech for the presence or absence of any reference to the six related issues, which served as a human check on the computational analysis of issue salience. For both the automated and manually-coded analysis, the UNGA GD speeches analyzed in each year are the same.

The temporal focus is on trends in the past three decades because international status dynamics changed significantly at the end of the Cold War. Fifteen years between 1994 and 2023 are analyzed, with comparison to two years from the Cold War (1978 and 1982). Due to the significant effort of manual coding, it was not possible to analyze speeches from every year. However, each year between 2014 and 2019 is examined to gain a finer-grained understanding of potential shifts at a time when the discussions intensified about challenges to the liberal international order.Footnote 24 All speeches in the first three years analyzed (1982, 1994, 2014) served as an initial probe and were fully manually coded twice, enhancing reliability. In the end, I rechecked all seventeen years for consistency.

A critic might find limitations to relying on the utterances of states. Political leaders, for example, may or may not, be honest in presenting their states’ achievements, policies or goals. First, however, even if some leaders’ descriptions of their states are misleading, invoking certain characteristics and values nevertheless conveys and reinforces the salience of these symbols (see Hall Reference Hall, Hall and du Gay1996: 4; Crawford Reference Crawford2002: 125–28; Hurd Reference Hurd2011: 591-96; Johnstone Reference Johnstone2011: 23–24; Bailes Reference Bailes, Daase, Fehl, Geis and Kolliarakis2015: 261–62; Abulof and Kornprobst Reference Abulof and Kornprobst2017: 10; Claude Reference Claude1966: 369), as they signal how they would like their states to be perceived. While inaccurate self-categorizations may stretch or eventually weaken shared understandings of the social categories and values in question, they are relevant in signaling their social significance in a given venue and point in time. Second, studying discourse rather than behavior admittedly presents a piece, albeit an interesting and significant piece, of a larger picture about normative shifts in an evolving international order. My approach complements, for example, scholarship on norm robustness or status that also studies actions, behavior or material influences (e.g., Deitelhoff and Zimmermann Reference Deitelhoff and Zimmermann2019; Larson and Shevchenko Reference Larson and Shevchenko2010; Beaumont and Røren Reference Beaumont and Røren2025), which offer insights into related yet distinct research questions. By highlighting the relevance of salient normative status dimensions as a concept and empirically comparing their patterns as expressed in speech across six issue areas in the GD over time, this study adds a new perspective into ideational shifts across international society, as shown in the findings presented in the following section.

Findings: Dynamics of salient normative status dimensions and issues in the UNGA GD

Democracy and human rights: Consistent, moderately salient normative status dimensions

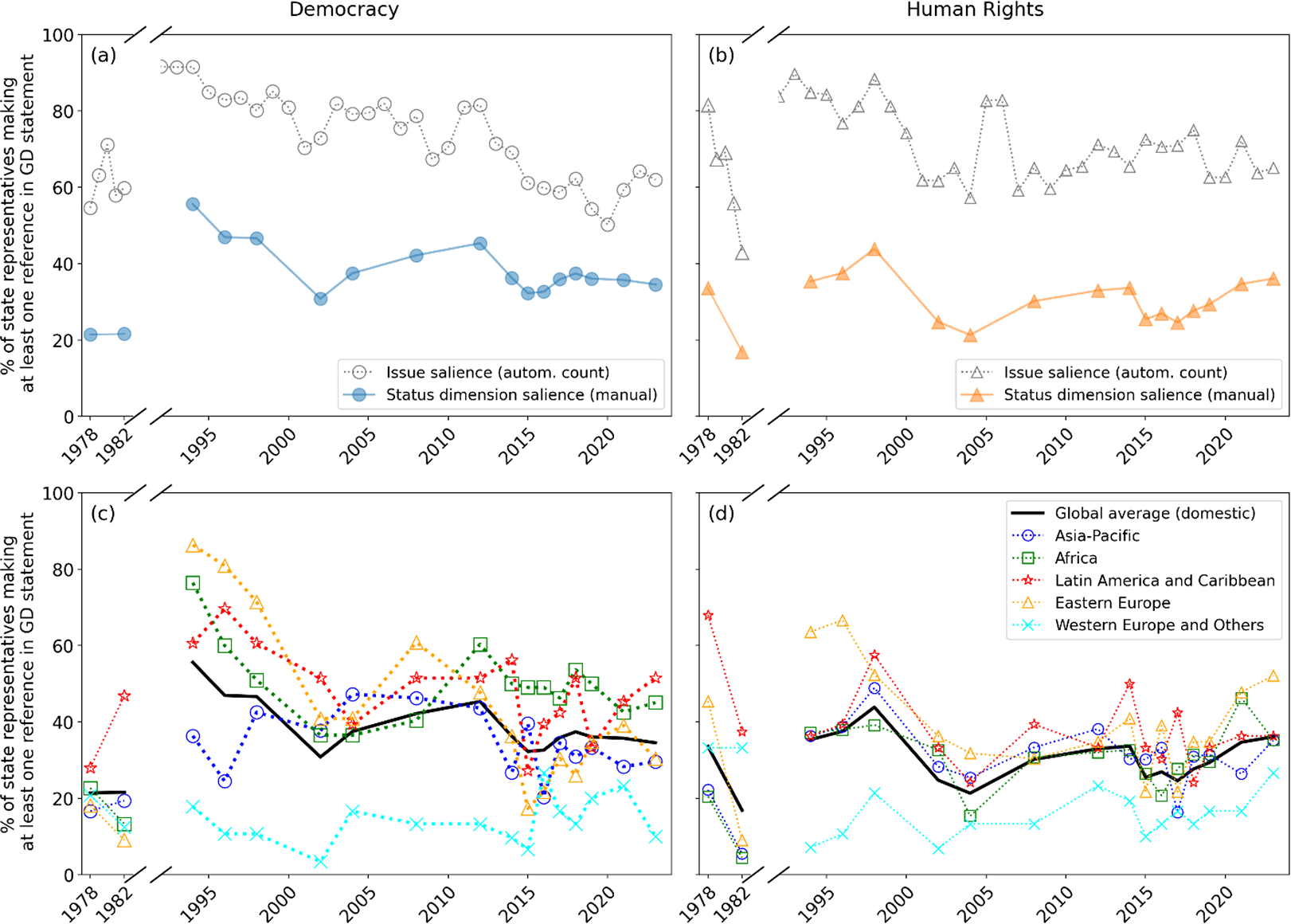

Trends in the salience of normative status dimensions based on democracy or human rights in the GD are shown by the lower, colored lines (filled symbols) in Figure 1(a) and (b), which represent the percentage of state representatives that made at least one domestic-level social identification based on these topics in their GD statement in the given year. These data points are derived from the manually-coded content analysis, as described above. The top, grey lines (open symbols), by contrast, indicate the salience of democracyFootnote 25 and human rightsFootnote 26 as issues in the GD in the respective years and are derived from the computational text analysis. Figure 1(c) and (d) disaggregate the global average of the percentage of speakers making at least one domestic social identification in the respective categories (black line, status dimension salience) according to the five UN regional groups.

Figure 1. Democracy and Human Rights. Panels (a) and (b): Status dimension salience (lower lines, filled symbols) versus issue salience (top lines, open symbols). Panels (c) and (d): From each UN regional group, the percentage of state representatives in the GD making at least one domestic-level social identification related to democracy or human rights in their statement.

In the issue areas of democracy and human rights, typically considered to be integral to (liberal) international order after the Cold War, we observe patterns similar to boxes (i) and (e) in Table 1 (decreasing or stable in parallel). Yet there are also notable indications of decorrelation for democracy in recent years (box f in Table 1), as issue salience has decreased while status dimension salience has remained stable.

In 1978 and 1982, democracy was central to a more limited, liberal order in the bipolar international system. Figure 1(c) and (d) show that Latin American states (red stars) in 1978 and 1982 self-categorized in terms of democracy and human rights at levels higher than the global average. By 1994, as the so-called liberal international order expanded globally, states in the Eastern European, Asia-Pacific and African regions increasingly expressed their domestic characteristics, reforms and goals in these terms. Democracy and human rights became more contested in some quarters in the 2000s. After peaking in the mid-1990s, state representatives’ social identifications of their states in these terms declined in the 2000s, yet have remained stable in the 2020s, signaling continued significance, even if the categories’ salience is comparatively lower.

In the 1990s, the higher salience of democracy in the GD as an issue and basis of positive social identifications corresponded, inter alia, with the decreased appeal of alternative forms of governance at the end of the Cold War, regional interests (e.g., European Union accession), significance as a basis for partnerships, cooperation or foreign investment and the UN’s flexible understanding of democracy. In 2000, UN member states adopted a GA resolution to support democratic consolidation (A/RES/55/96). The decline and plateau of domestic democracy-related social identifications since 2000 corresponds, inter alia, with lower-than-expected recognition of democratizing states’ reforms, increased availability of partnerships without democratic conditions, increased contestation, shifts in perceptions of democratic states after the 2008 financial crisis, and the increased salience of other status dimensions (e.g., related to sustainable development) (Hecht Reference Hecht2016), as shown in the following sections. The plateau in recent years suggests some stability despite the recent lack of clarity about the place of democracy in (global) international order.

Figure 1(b) shows that the salience of human rights as a normative status dimension (orange-filled triangles) follows a similar pattern to democracy. There is a larger distance between the lines in Figure 1(b) than in Figure 1(a). Perhaps surprisingly, states’ domestic-level social identifications in terms of human rights have generally been expressed less frequently in the GD, even though diplomats discuss human rights as an important international issue, often referencing key human rights declarations and conventions (e.g., Universal Declaration of Human Rights), especially on important anniversaries. Moreover, states seeking election to the Human Rights Council would have incentives to publicize their commitment to human rights. Human rights also have symbolic flexibility, as leaders can refer to social, economic, cultural, civil or political rights. In recent years, some diplomats have framed domestic-level priorities, achievements and goals related to social and economic rights instead in terms of development agendas.

Contestation has also affected the salience of democracy and human rights in the UNGA GD, even if the contestation takes place elsewhere. In Figure 1(c) and (d), decreased social identifications are observed in the Eastern European group after 2000 and the Asia-Pacific group after 2010. States in the African and Latin American and Caribbean groups have self-identified at levels above the global average on democracy and closer to the average on human rights. The relatively infrequent representation of states in the Western Europe and Others group (WEOG) corresponds with their traditional emphasis on foreign rather than domestic-level policy in their GD statements, however, some shifts are observed in more recent years. Although the fairly consistent issue and status dimension salience in the cases of democracy and human rights suggests that these have been stable components of post-Cold War international order, Figure 1 suggests their decreased centrality.

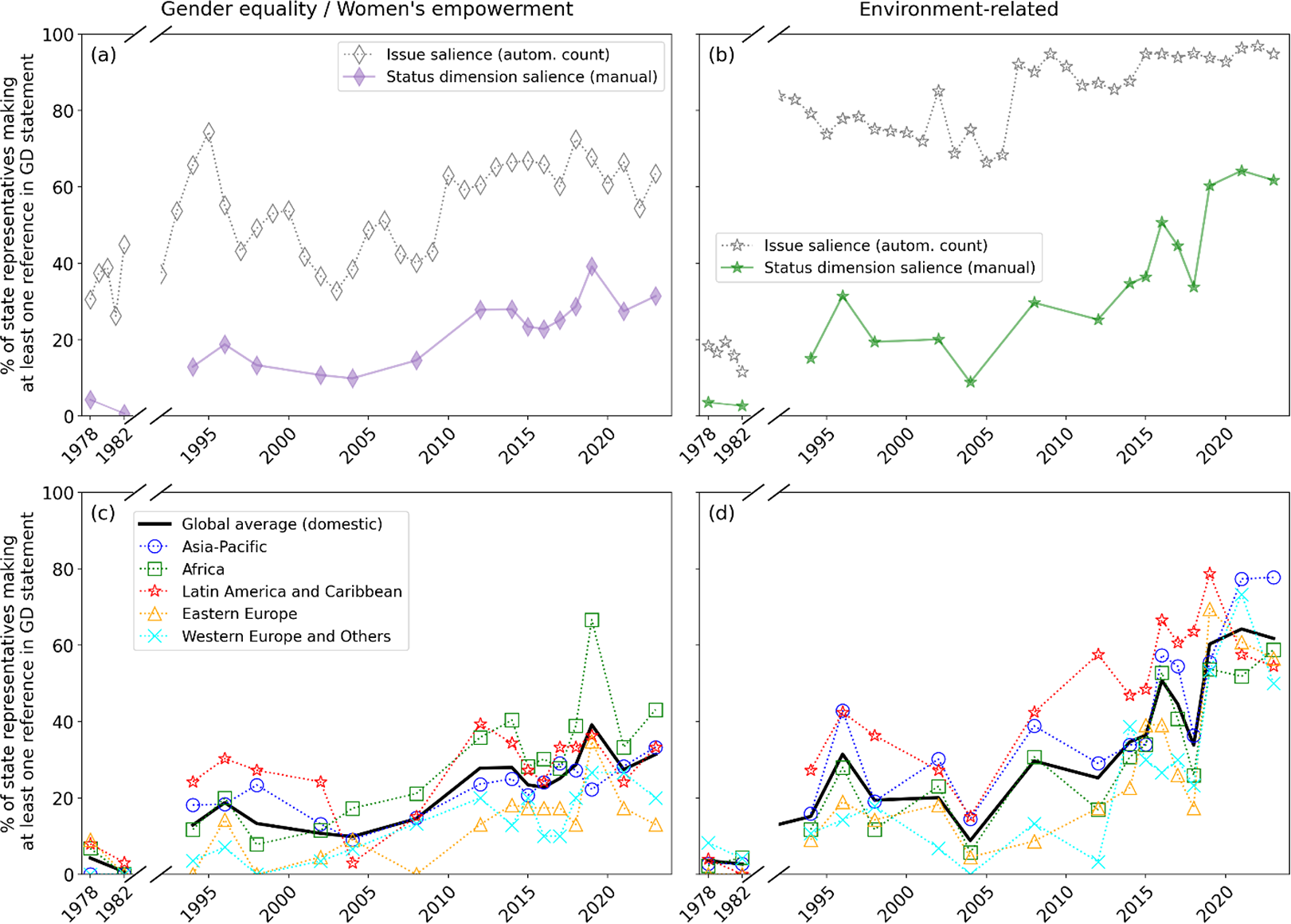

Gender equality/women’s empowerment and environmental protection/climate action: Newer and rising normative status dimensions

In a second pattern, status dimension salience in the issue areas of gender equality and women’s empowermentFootnote 27 and environmental protection, including climate action,Footnote 28 has risen from near zero in 1982 and notably low levels in the early 1990s to greater social significance in the GD over time. In 1982, only 4 state representatives mentioned their states’ domestic-level efforts to protect the environment and only one country mentioned its efforts to pursue gender equality or empower women domestically. Yet in 2019, both surpassed the salience of democracy as a basis of domestic-level social identifications in the GD.

Figure 2(a) and (b) show decorrelation in the 1990s and 2000s, when persistently low levels of status dimension salience on these issues are observed alongside widely fluctuating issue salience in both categories, as in boxes (d) and (f) in Table 1. Yet, more recently, both issue salience and status dimension salience for gender equality/women’s empowerment have generally become more correlated (box (a) in Table 1), yet they remain decorrelated environmental protection/climate action (box (b) in Table 1). Environmental protection and climate action recently became the third most frequently expressed type of domestic-level social identification in the GD of those studied here (after social development/fighting poverty and economic development).

Figure 2. Gender Equality/Women’s Empowerment and Environmental Protection/Climate Action. Panels (a) and (b): Status dimension salience (lower lines, filled symbols) versus issue salience (upper lines, open symbols). Panels (c) and (d): From each UN regional group, the percentage of state representatives making at least one domestic-level social identification related to gender equality/women’s empowerment or environmental protection/climate action in their GD statement.

Gender equality/women’s empowerment and environmental protection/climate action are newer bases of states’ social identifications, which have increased alongside institutionalization processes in the UN system and beyond (see also Towns Reference Towns2010). Despite increased discussion of gender equality around the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women (top line, open diamonds), and efforts to implement the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, these topics became more relevant to states’ social identifications in the GD gradually, as Figure 2(a) shows.

Figure 2(c) shows that African states have often expressed domestic efforts and achievements related to women’s empowerment or gender equality at levels above the global average and contributed significantly to the rise observed in 2019. On this and protecting the environment and fighting climate change, states in the Latin American and Caribbean region have been above the global average in showcasing domestic-level efforts and goals (Figure 2(d)). States in the Asia-Pacific group have increasingly referenced national efforts and goals such as renewable energy, especially in 2021 and 2023. States in the Western Europe and Others group have also increasingly spoken about domestic-level climate action. States from all regions have highlighted policies or actions to fight climate change related to the Paris Agreement. For example, in 2021, 25 state representatives highlighted their states’ efforts or commitments with explicit reference to their nationally determined contributions.

The observed shifts on both issues have often corresponded with institutionalization. In 1994, several states mentioning domestic-level efforts to protect the environment also referenced the 1992 Rio Earth Summit or the 1994 Global Conference on the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States. Figure 2 (b) and (d) show more significant increases after the Kyoto Protocol came into effect in 2005, and especially since 2015 when states adopted the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the SDGs. Increases in the GD related to gender equality and women’s empowerment since the 2010s have followed the creation of UN Women in 2010, which consolidated the UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), the Division for the Advancement of Women, the Office of the Special Adviser on Gender Issues and Advancement of Women, and the International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women, and enhanced UN support to national governments on these issues (see Hecht and Steffek Reference Hecht and Steffek2024).Footnote 29 Annual sessions of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) and summits of the Conference of the Parties (COP) of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change regularly mobilize participation by state representatives, IO staff, civil society actors and others. Alongside efforts of the international environmental and women’s movements, the institutionalization of the 2030 Agenda and SDGs at multiple levels since 2015 appears to support salience in both issue areas. Contestation in other UN and multilateral venues, however, has potentially limiting effects, even though these topics are not typically contested in the General Debate itself. Aggregate domestic-level social identifications related to the environment and climate action were notably resilient in the late 2010s, despite the U.S. announcement to withdraw from the Paris Agreement in 2017. The trends in Figure 2 suggest that institutionalization at the international and domestic levels contributes to increased status dimension salience in the GD, as many states express their commitment to implementing domestic and collectively agreed international agendas. Decorrelated issue salience and status dimension salience (as before the mid-to late 2000s in both cases in Figure 2) can represent the potential for states to add a positive characteristic, effort or goal into their repertoires.

Economic development and social development/fighting poverty: Decorrelated or weakly anti-correlated, rising normative status dimensions

A third pattern is shown in Figure 3 in the issue areas of economic developmentFootnote 30 and social development/fighting poverty,Footnote 31 where status dimension salience and issue salience are decorrelated or weakly anti-correlated in both cases. In these issue areas, issue salience has been consistently high, however, status dimension salience has fluctuated in the case of economic development and has been moderate and rising in the case of social development. Again, we see that it is impossible to infer status dimension salience from issue salience. The decorrelated pattern for social development and fighting poverty generally corresponds with box (b) in Table 1. High percentages of state representatives have consistently mentioned terms connected with economic development, growth, social development or fighting poverty as issues at least once in their statements, yet related normative status dimensions have fluctuated and become more salient recently.

Figure 3. Economic Development and Social Development/Fighting Poverty. Panels (a) and (b): Status dimension salience (lower lines, filled symbols) versus issue salience (upper lines, open symbols). Panels (c) and (d): From each UN regional group, the percentage of state representatives in the GD making at least one domestic-level social identification related to economic development or social development/fighting poverty in their statement.

Social development and fighting poverty have traditionally been more peripheral to liberal international order. Accordingly, note social development’s sluggish performance as a status dimension in the 1990s and early 2000s. By contrast, economic development and related components (e.g., free trade) are typically considered central to liberal international order. States with authoritarian regimes also showcase their economic growth, policies and goals. Comparing Figure 3(a) and (c) with Figure 1 conveys that states’ discursive support for economic liberalism remains stronger than for political liberalism.

In 1982, approximately 36 per cent of state representatives showcased domestic economic development or related reforms in the GD, while approximately 26 per cent articulated domestic-level policies or goals in terms of fighting poverty/social development. The latter is just slightly higher than democracy in 1982 (Figure 1(a)), yet the categories’ salience evolved quite differently. Figure 3(a) shows that in 1994 and 1998 a significant percentage of state representatives showcased their economic growth or reforms related to privatization, liberalization, structural adjustment policies, infrastructure, development, opening markets, etc. in their statements. While failures of the ‘Washington Consensus’ decreased the popularity of related macroeconomic policies, political leaders have continued to highlight economic growth statistics or other domestic-level economic policies in the GD. Figure 3(c) shows that in the 1990s, Eastern European states actively mentioned economic development and reforms, as several pursued European Union accession, similar to the patterns observed in Figure 1. In both issue areas, states from the Latin American and Caribbean group have consistently self-categorized at levels above the global average, as have states in the African and Asia-Pacific groups.

Figure 3(b) shows that the percentage of state representatives making at least one domestic-level social identification in terms of social development or fighting poverty rose to over 70 per cent in the GD, with peaks in 2016 and 2021, even surpassing economic development by this measure in 2014-2017. Although the UN system supported social and human development agendas for decades, states’ domestic-level identifications with aspects of these agendas increased more gradually in the GD. Prominent development discourses and global conferences of the 1990s, including the 1995 World Summit for Social Development in Copenhagen, corresponded in timing with moderate levels of states’ social identity expressions related to social development. Trends appear to be reinforced by the gradual institutionalization of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), between 2001 and 2015 (see Fukuda-Parr and Hulme Reference Fukuda-Parr and Hulme2011).

Since 2015, the trends in Figure 3 correspond with institutionalization of the SDGs, which have a broader scope than the MDGs’ earlier focus on basic needs, as the SDGs extend more holistically to economic, social and environmental dimensions of development (see Kamau, Chasek and O’Connor Reference Kamau, Chasek and O’Connor2018; Dumitriu Reference Dumitriu2023). Economic and social development have been increasingly expressed in domestic social identifications as mutually reinforcing, which arguably contributes to their salience. For example, Mr. Arthur Peter Mutharika, President of the Republic of Malawi, stated in 2018: ‘My government is endeavouring to eliminate hunger and malnutrition by 2030. Inclusive and resilient economic growth is key to overcoming hunger and reducing poverty… We now expect growth of 4 per cent in our 2018–2019 financial year’.Footnote 32 Similarly, a significant number of state representatives highlight their states’ efforts to advance green growth, the blue economy or renewable energy, agendas with connections to both the economic and environmental dimensions of development. These examples show that how agendas are interpreted, including their synergies, can reinforce the salience of a normative status dimension in a particular multilateral venue.

The COVID-19 pandemic increased attention to health-related issues on the global agenda. Domestic-level health policies, efforts and priorities were initially coded as a component of social development-related social identifications. For example, Ms. Salome Zourabichvili, President of Georgia, stated in 2019: ‘Georgia has made the political choice to move towards a universal health coverage system and tripled health allocations across all sectors. Today, 90 per cent of our population has access to primary-care services’.Footnote 33 To learn more about recent changes in the salience of health as an issue and normative status dimension in this venue, I further disaggregated the 1996, 2002, 2012, 2019, 2021 and 2023 GD statements, summarized in Table 2.Footnote 34 Despite significant issue salience in 2002, which corresponded in timing with the MDGs, which contained three health-related goals, global concern about HIV/AIDS and the launch of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the salience of a health-related status dimension increased in later years. Decorrelation is thus also observed in this issue area. Issue salience remained higher in 2023 than before the pandemic, although status dimension salience was lower in 2023 than in 2019. Notably, in 2021 more countries highlighted their domestic health policies, vaccination, or other pandemic-related efforts in the GD than expressed positive social identifications in terms of democracy, human rights or gender equality and women’s empowerment. Only environmental protection, economic development and social development/fighting poverty were more salient than health as normative status dimensions in the GD in 2021. This example shows that even as health became a highly salient status dimension, it did not fully replace, but rather joined and co-exists with traditional and previously salient status dimensions in international society.

Table 2. Percentage of state representatives making at least one mention of health as an issue or in a domestic-level social identification in their GD statement in selected years

Are we observing initial stages of convergence in the ways in which developing and industrialized states interact with the international normative environment and use these symbolic resources in discourse in the UNGA? A shift in WEOG states’ social identifications has been tentative and gradually more noticeable after 2015. Figure 3(c) and (d) show some increases in WEOG states’ self-representations related to social development/fighting poverty and economic development. The shift to ‘universality’ in the 2030 Agenda conveyed that all states, developing and industrialized alike, are expected to pursue the domestic-level sustainable development goals and targets. A corresponding discursive shift is reflected, for example, in the statement by Mr. Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, in 2017: ‘The Sustainable Development Goals are as meaningful in Canada as they are everywhere else in the world. We are committed to implementing them at home, while we also work with our international partners to achieve them around the world’.Footnote 35 Some states seeking leadership positions have self-categorized as aspiring towards and supporting the SDGs. Mr. Charles Flanagan, Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade of Ireland, which, like Canada sought election in 2020 for a two-year term on the UN Security Council, stated in 2016: ‘we are now called to meet our obligation to implement the SDGs domestically within our own borders, bilaterally with our development partners, and multilaterally within regional and United Nations forums’.Footnote 36 Domestic-level social identity expressions can communicate leadership by example. A shift in the applicability of norms to all states can contribute to greater alignment between issue salience and status dimension salience. Economic development and social development/fighting poverty are examples in which decorrelation, or high issue salience alongside moderate status dimension salience (as in the 1990s), can represent untapped potential for an increase in the salience of a status dimension in the future (box (b) in Table 1).

Conclusions

By visualizing shifts in the salience of six normative status dimensions over time, this article has presented new insights into how values underpinning an international order have been evolving between 1978 and 2023, from the perspective of the wide range of the world’s states. Adding to IR scholarship on international societies, the study of trends in state representatives’ positive domestic-level social identifications in the UNGA General Debate revealed surprising patterns in the ‘distribution of identities’ and the extent to which leaders categorize their states as associated with informal groups with similar values.

The analysis showed that there has been an expansion, rather than replacement, of the domestic-level components that are featured in states’ positive social identifications in international society. In 1994, democracy and economic development were the two most salient domestic-level social identifications articulated in the GD of the six studied here, followed by social development/fighting poverty and human rights, respectively. In the 2010s, social development/fighting poverty and environmental protection/climate action became more salient as normative status dimensions alongside economic development, and the salience of gender equality and women’s empowerment also increased. The COVID-19 pandemic boosted the salience of health, which in 2021 co-existed with other highly salient status dimensions. Democracy has shifted from a central to a more peripheral, yet still significant, place in international order.

Table 1 introduced a schematic overview of possible relations between the salience of issues and normative status dimensions. The latter offers a meaningful indicator of the strength and appeal of a certain value in an international society at a given point in time and conveys unique information about prospects for action and cooperation on a particular issue. These two indicators do not necessarily rise and fall together. Decorrelated patterns were observed most strongly in the issue areas of social development/fighting poverty and economic development, as well as before the mid-2000s with environmental protection/climate action and gender equality/women’s empowerment. The curious pattern of decorrelated high or fluctuating issue salience with comparatively low status dimension salience suggests potential for a social identity to become salient in a given venue. Quantitative approaches that rely solely on frequency indicators are unable to detect these patterns. One factor that appears to have brought the salience of issues and status dimensions into greater alignment in the UNGA GD has been the implementation of collectively negotiated and endorsed agendas at the international and domestic levels, such as the 2030 Agenda, the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement.

Future research could further explore scope conditions for the rise, fall and plateau of normative status dimensions, differences in meanings, interpretations and understandings among actors, or compare patterns in other international organizations. It would also be interesting to study trends in the use of other social identifications, such as contributions to regional and international-level efforts, peace and security, or official development assistance, which would have different dynamics and potential groups than the domestic-level social identifications among all states as discussed here. A follow-up study could also explore the extent to which state representatives’ self-categorizations of their states may be in harmony with, or disconnected from, domestic policies or the perceptions of their inhabitants.

What are potential policy implications for (normative) leadership in international society? When democracy was among the most salient social categories in international society, certain states self-identified as prototypical. This is breaking down, but what replaces it remains unclear. States with proven successes in social development and fighting poverty, environmental protection or gender equality and women’s empowerment are not necessarily yesterday’s leaders. Today, exemplifying the full range of norms that demonstrate commitment to the purposes and principles of the UN is a tall order. Few states, if any, are prototypical for all social identities that are currently salient. A shortcut for potential leaders is to associate with aspirations collectively endorsed in global agendas such as the SDGs (see Finnemore and Jurkovich Reference Finnemore and Jurkovich2020). For scholars or practitioners concerned about the future of liberal international order, the findings of this study suggest to expand liberal ideas of modernity with attention to the distribution of what state representatives say their states are (or are becoming). To appeal to a larger group of actors in international society, it could be useful to increase linkages with the global environmental protection, climate action, social development and poverty eradication agendas.

Early 2025 is a difficult time to envisage the future of international order. This analysis emphasizes the relevance of studying states’ aggregate positive social identifications, as articulated in the UN General Assembly, to help understand the fluctuating salience of a range of values that shape the social purposes of international society. It remains an open question to which values states will orient themselves in international society and which will rise, fall, or continue to appeal.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Jörg Rottler for help with the computational analysis of the corpus. Earlier versions of this article were presented at the International Studies Association Annual Convention, the European International Studies Association pan-European Conference on International Relations and (virtual) research colloquia at the Centre for Global Cooperation Research at the Universität Duisburg-Essen and the Technische Universität Darmstadt. Many thanks to all participants, and to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive comments. I would also like to thank Deborah Larson and Jens Steffek for helpful feedback on an earlier version and Mor Mitrani for helpful discussions. This research was partly conducted during a senior research fellowship at the Käte Hamburg Kolleg/Centre for Global Cooperation Research, Universität Duisburg-Essen.

Appendix 1: Examples of coding decisions: Domestic-level social identifications related to six issue areas in the UN General Assembly General Debate