I. The populist spectre haunting Global Constitutionalism

The contemporary rise of populism appears like an existential threat to Global Constitutionalism (GC), as politicians like Donald Trump or Matteo Salvini routinely ignore, discredit or actively undermine normative principles underlying global politics. Recent editorials of this journal worried that ‘far right populist authoritarian parties and leaders enjoying considerable successes across Europe and the US [signal a] decay of ‘the West’ […] anchoring a normative model of global order in which commitments to human rights, democracy and the rule of law are central’ (Kumm et al. Reference Kumm2017: 2). Hence, ‘from the global constitutionalist perspective Trumpism represents an attack on the three foundational features of the global constitution – democracy, human rights, and the rule of law’ (Havercroft et al. Reference Havercroft2018: 4).

However, the rise of populism may be more complex and ambiguous for GC than its authoritarian and nationalist incarnations suggest. Indeed, at the domestic level, a long-standing debate has considered populism’s relationship to constitutional principles as ‘two-faced’ (Canovan Reference Canovan1999) and ‘ambiguous’ (Mény and Surel Reference Mény, Surel, Mény and Surel2002), depending on the state of liberal democratic politics and the responses of other parties, institutions and voters (Arditi Reference Arditi and Panizza2005; Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart Reference Rovira Kaltwasser and Taggart.2016; Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2017). Precariously, pure populist majoritarianism is inconsistent with liberal democratic principles, but such regimes nonetheless rely on majoritarian rule to be legitimate (Berman Reference Berman2017; Mounk Reference Kyle and Mounk2018). Hence, if populism contributes to addressing defects in representative practice, it might even function as a democratic corrective, rather than an authoritarian threat (Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Rovira Kaltwasser2012), so long as populists do not undermine constitutional protections of liberal rights (Rummens Reference Rummens and Kaltwasser2017).

Empirical literatures also find such ambivalence: on the one hand, principles of horizontal accountability and democratic contestation seem to suffer where populists rule in less consolidated and executive-dominated institutional contexts (Levitsky and Loxton Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013; Huber and Schimpf Reference Huber and Schimpf.2016a; Houle and Kenny Reference Houle and Kenny.2018; Kyle and Mounk Reference Kyle and Mounk2018; Ruth Reference Ruth2018). On the other hand, where populism is in opposition, where democracy is more consolidated or where the institutional system is robust enough to prevent executive power-grabs, populist challenges may show corrective effects for overall democratic quality, participation and representation (Huber and Schimpf Reference Huber and Schimpf2016b; Andreadis and Stavrakakis Reference Andreadis and Stavrakakis.2017; Hawkins and Ruth Reference Hawkins, Ruth., Heinisch, Holtz-Bacha and Mazzoleni2017).

Importantly, beyond institutional factors and opposition status, the specific sub-type of populism also appears to be a relevant factor for its democratic influence: only radical right populists consistently undermine minority rights and mutual constraints across contexts (Huber and Ruth Reference Huber and Ruth.2017; Huber and Schimpf Reference Huber and Schimpf2017). In contrast, more inclusive types of populist challenge may be more likely to contribute to potentially corrective, democratising reform (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013; March Reference March2017; Mouffe Reference Mouffe2018): after all, leftist politicians like Bernie Sanders in the US or the Spanish Podemos Party appear squarely opposed to authoritarian ‘Trumpism’ despite being populists.

However, existing labels of ‘right’ and ‘left’ populism are also criticised as insufficient to discriminate between varieties of populism: some authors equate cases qua their shared populism as increasingly similar in nationalism and authoritarianism (Halikiopoulou, Nanou and Vasilopoulou Reference Halikiopoulou, Nanou and Vasilopoulou.2012; March Reference March2017: 284–6). Others warn against such a conflating tendency and critically examine the ‘reified association’ of populism and right-wing nationalist authoritarianism (Stavrakakis et al. 2017) or communitarianism (Ingram Reference Ingram and Kaltwasser2017). Indeed, the possibility of more transnational variants of populism has started to be theorised (De Cleen Reference De Cleen and Kaltwasser2017; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2017).

Against this backdrop, the populist relationship to global constitutionalism (GC) thus requires further scrutiny: how do varieties of populism discursively challenge normative principles beyond the state binding politics?

The main argument of this article is that populism challenges liberal GC in equally ambivalent ways which depend on its host-ideological variety. Populism engages in a contestation of global institutions via the discursive advance of ideology which may either contribute to undermining democratic politics or to pointing out and reforming normative flaws in its practice. Specifying distinct varieties, I identify four populist discursive challenges to GC by extending the classic distinction between exclusionary and inclusionary populism and empirically illustrate these through exploratory case studies of the German Alternative for Germany (AfD), the Polish Law and Justice Party (PiS), the Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25) and Peru’s Alberto Fujimori.

While all populists contest a perceived lack of popular sovereignty in GC, I show that there are both, communitarian types of populism presenting an illiberal and authoritarian threat, but also cosmopolitan types of populism which may challenge GC on behalf of liberal and democratic principles. In two sub-types, the majoritarian challenge to political frameworks at the global level is additionally combined with targeting liberal economic principles beyond the state binding politics. Finally, important contemporary examples of ‘left’ populism fall between these ideal types, highlighting key ideological ambiguities in their discursive quest for power.

Two main implications derive from these findings: First, contemporary varieties of populism present distinct challenges to normative principles beyond the state. In this regard, communitarian populism pushes towards global de-constitutionalisation by targeting the liberal and democratic pillars of GC, while cosmopolitan populism advances discourses strengthening liberal-democratic GC. Neo-socialist versions of both types seek to alter neoliberal economic choices enshrined beyond the state, and some such contemporary cases remain torn between supporting or opposing liberal political principles of GC. Overall, varieties of populism therefore illuminate the contours of an emerging discursive contest between principles of undemocratic (neo-)liberalism, illiberal democracy and democratic liberalism as alternative visions of democratically legitimate global normative frameworks.

Second, in contrast to existing functional accounts of global constitutionalisation, an increasing politicisation of the constitutional process at the societal level is therefore apparent where such populists emerge. According to ideational theories, institutional consequences of such politicised contests depend on other parties’ behaviour, contextual opportunity structures and the choices of voters. Estimating direct effects of populist contestation on GC is elusive given these contingencies, but constitutional differentiation according to context appears more likely than uniform constitutional demise.

While the rise of populism politicises normative principles binding global politics, the fate of GC is thus in no way foretold. The specific populist challenge, as well as the choices of key actors in contexts with different driving forces all influence how the discursive contests over global constitutionalisation unfold. Within this process, nuance towards both populism and the normative practice of global institutions is essential to discursively and politically defend the global constitutionalist project where justified, to sustain it where possible and to improve it where necessary.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: Section II defines global constitutionalism and its normative features. Section III develops a typology of populism in a context of transnational politicisation which Section IV empirically substantiates through illustrative case studies. Section V analyses the relationship of contemporary populist challenges to global constitutional principles, before Section VI draws implications for the process of global constitutionalisation and its possible trajectories. A final section concludes.

II. Global Constitutionalism: The global constitutionalisation of liberal principles

Global constitutionalism (GC) is a social phenomenon which results from a qualitative shift from globalisation to constitutionalisation of world politics (Wiener et al. Reference Wiener2012). In a partially global political system, constitutional frameworks binding politics through normative principles embodied in law are increasingly integrated with global processes of constitutionalisation as contained in legal institutions beyond the state (Lang and Wiener Reference Lang, Wiener, Lang and Wiener2017; Zürn Reference Zürn2018).

In its current variant, global constitutionalisation refers to the global legal and political order increasingly resting on the normative basis of principles derived from liberal values of individual self-determination (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett, Finnemore., Barnett and Duvall2005). These principles are commonly seen as represented by human rights, the rule of law, democracy as well as market-based production and allocation of resources (Dunoff and Trachtman Reference Dunoff, Trachtman., Dunoff and Trachtman2009; Gill and Cutler Reference Gill, Cutler., Gill and Cutler2012; Tushnet Reference Tushnet2019). Specifically, global liberal political principles constrain negative externalities of national politics such as unilateralism and the use of state violence and human rights violations for political goals (Axelrod and Keohane Reference Axelrod and Keohane.1985; Keohane, Macedo and Moravcsik Reference Keohane, Macedo and Moravcsik2009). Similarly, global (neo-)liberal economic principles limit national political autonomy to prevent negative spillover of protectionism and to facilitate the operation of international capital- and goods markets (Hall and Biersteker Reference Hall, Biersteker., Hall and Biersteker2002; Gill and Cutler Reference Gill, Cutler., Gill and Cutler2012).

Authority resting on these principles is encapsulated in international legal institutions which either constrain or enact policy towards individuals (in the form of human rights or investor protections) and states (in the form of rules-based multilateralism) (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett, Finnemore., Barnett and Duvall2005; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe2017; Zürn Reference Zürn2018). By resting on and shaping international law, these institutions bind global and domestic politics according to (neo-)liberal principles.

In the absence of global authority with coercive power over states, this way of binding politics depends on legitimacy, i.e. its social acceptance by rule-addressees (Zürn, Binder and Ecker-Ehrhardt Reference Zürn, Binder and Ecker-Ehrhardt2012). In democracies, specifically, the social acceptance of international authority hangs on congruence with the liberal democratic principles which are normatively expected by citizens to guide politics (Weßels Reference Weßels, Ferrín and Kriesi2016). As put by Allan Buchanan and Robert Keohane: ‘The perception of legitimacy matters, because, in a democratic era, multilateral institutions will only thrive if they are viewed as legitimate by democratic publics’ (Reference Buchanan and Keohane.2006: 407). Hence, if global constitutional authority is not perceived as liberal and democratic, its social acceptance may decrease, ultimately threatening its capacity to bind politics.

Liberal democratic principles of politics require balancing (1) the liberal protection of individual and minority rights; as well as (2) democratic majority rule (or popular sovereignty) (Ulbricht Reference Ulbricht2018). As such, these regimes rely on liberal institutions strengthening inclusive participation on equal terms by limiting majority rule and democratic public contestation over majoritarian authority to maximise ‘continuous responsiveness of government to the preferences of its citizens, considered as political equals’ (Dahl Reference Dahl1971: 1). In turn, authority responsiveness requires both, citizens’ rights to evaluate (dis-)satisfactory decision outcomes, and the capacity to use such judgments to shape future decisions via democratic contestation and participation (Powell Reference Powell2004). In addition to legal protections of individual and minority rights, political legitimacy in democracies therefore is sourced from the output of decision-making and from the means to change dissatisfactory decisions via democratic input.

Both pillars of liberal democratic legitimacy are affected by institutions beyond the state. Constitutional limitations on majoritarian politics are particularly prominent in GC: most decision-making is delegated to quasi-constitutional non-majoritarian institutions such as courts, technocratic bureaucracies or expert bodies as well as pooled in International Organisations (IOs) deciding on the basis of agreed rules (Thatcher and Sweet Reference Thatcher and Sweet2002; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks.2015). Similarly, the constitutionalisation of (neo-)liberal economic principles enshrines market mechanisms as economic and social frameworks which are deemed superior to guide politics (Gill and Cutler Reference Gill, Cutler., Gill and Cutler2012; Scharpf Reference Scharpf2017).

In addition to constitutional constraints beyond the state, the popular sovereignty pillar of democratic legitimacy also has international dimensions: on the one hand, authoritative global markets and IOs affect social outcomes alongside decisions by domestic, democratically elected politicians (Hall and Biersteker Reference Hall, Biersteker., Hall and Biersteker2002; Zürn, Binder and Ecker-Ehrhardt Reference Zürn, Binder and Ecker-Ehrhardt2012). If part of the legitimation of authority in democracies is that political decision-making yields outcomes deemed as satisfactory by citizens, collectively-binding decision output by IOs may thus become subject of democratic legitimacy evaluations (Zürn Reference Zürn2004; Steffek Reference Steffek2015; Kreuder-Sonnen and Rittberger Reference Kreuder-Sonnen and Rittberger2019).

On the other hand, as a result of the constitutional, non-majoritarian nature of much authority beyond the state, the input-side of the democratic pillar is less developed in GC (Besson Reference Besson, Dunoff and Trachtman2009). In principle, this side of popular self-determination is institutionalised through the sovereignty of national democratic states, legitimating international politics through consented delegation or pooling of authority by elected governments (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2002; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks.2015). Once delegated, however, most decision-making of authoritative international institutions is not publicly contestable through processes of public deliberation, democratic competition and executive accountability, in contrast to domestic constitutional orders (Follesdal and Hix Reference Follesdal and Hix.2006; Tsakatika Reference Tsakatika2007). Such public contestability of authority, however, is a key requirement to ensure responsiveness of authorities to citizen preferences and hence democratic quality in (global) political institutions (Dahl Reference Dahl1971: 2). While there are also rare ‘pockets’ of majoritarian politics beyond the national level to contest policy choice and constitutional frameworks, these remain limited in authority and transnational character (Freyburg, Lavenex and Schimmelfennig Reference Freyburg, Lavenex and Schimmelfennig2017; Rocabert et al. Reference Rocabert2019).

In sum, institutions of GC thus affect both the liberal democratic principles of constitutional rights and checks on majoritarian excess as well as popular sovereignty over authoritative decision-making. Yet, the (neo-)liberal constitutional pillar dominates over limited opportunities for democratic policy choice or constitutional reform in a largely non-majoritarian global order. As I discuss next, the legitimacy in practice of global authority resting on these normative bases represents a focal point of the populist challenge in liberal democracies.

III. The populist challenge: Ideology and discourse

Assessing the populist challenge to GC requires confronting the ‘cliché’ of populist conceptual fuzziness in public discourse (Panizza Reference Panizza2005: 1). Against these obstacles, social science of the last decades has solidified around a minimal consensus which considers populism to be a people-centred form of anti-elite politics in democracies which can be approached through different analytical lenses (Rovira Kaltwasser et al. Reference Rovira Kaltwasser and Kaltwasser2017; Aslanidis Reference Aslanidis2018a; Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis Reference Katsambekis, Kioupkiolis, Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis2019).

In this article, I rely on the ideational approach to populism which studies populist politics as a discourse or set of ideas holding that society is divided between the people and an elite and that the popular will should prevail in politics (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009; Mudde Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017; Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis Reference Katsambekis, Kioupkiolis, Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis2019). Populism, in this view, partly relies on a specific set of ideas to advance its people-centred anti-elitism, which can be identified and empirically studied (Aslanidis Reference Aslanidis2018a; Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins2018). Hence, political actors (e.g. leaders, parties or movements) simultaneously advancing ideas of people-centrism, anti-elitism and popular sovereignty in political discourse are defined as populist (March Reference March2017: 286–8).

This populist discourse qualifies as a particular, ‘thin-centred’ type of political ideology with limited range compared to more comprehensive sets of ideas like Liberalism or Socialism (Stanley Reference Stanley2008). By itself, populism does not offer an encompassing societal analysis with answers to most social problems: its core content instead is limited to the allegation that democracy was subverted by a morally corrupted elite, such that popular sovereignty is now lacking in the practice of representative politics (Hawkins, Read and Pauwels Reference Hawkins, Read, Pauwels. and Kaltwasser2017). To complement this ‘thin’ ideological centre, populist ideas are advanced in political discourse together with content from so-called ‘host ideologies’, which give the populist core concepts contextual meaning and define its substantive political programmes (Mudde Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017). As a result, varieties of populism – understood as the combination of populist discourse and host ideology – can come in different flavours depending on the discursive construction undertaken in each case.

This discursive construction forms a key populist avenue to power, attempting to develop a ‘hegemonic’ vision for society in competition with established parties (Laclau Reference Laclau2005; Stavrakakis Reference Stavrakakis2017). To that end, populist discourse strategically puts forward a (‘diagnostic’) narrative defining a societal crisis, draws on host-ideologies to offer (‘prognostic’) political answers in opposition to elite views, and constructs a shared people-centred political identity to mobilise constituencies in favour of political change in line with its vision (Aslanidis Reference Aslanidis2018b: 448). Where such populist discourse ‘resonates’ by aligning with citizen attitudes and perceptions of a given context, it may unfold political power by yielding populist electoral success, thereby influencing the broader political discourse directly upon entering office or indirectly as other parties take up elements of populist host-ideology to stave off the challenge to power (Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2017: S191–S194).

On this basis, I analyse the populist challenge as a discursive ‘contestation’, drawing on a concept of political conflict which refers to the introduction of distinctive ideas through political representatives in a political arena which is ideologically competing for electoral success (Marks and Steenbergen, Reference Marks and Steenbergen2002).Footnote 1 Despite contingencies of contextual resonance and populist ideologies interacting with institutions and other parties in these electoral arenas, comparatively analysing the discursive political supply of populist actors is a necessary step to understand their potential influence on institutions of GC. Within the discursive struggle for power in democracies, this article therefore focuses on the ideological challenge to global constitutional norms advanced by emerging populists.

Varieties of populist contestation: Exclusion vs. inclusion and transnational politicisation

How can populist discursive contestations vary? The seminal distinction is between ‘exclusionary’ and ‘inclusionary’ types of populism (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013). Both types share the core populist ideology, but they differ in three related features: (1) how they discursively construct the populist core and host ideology to give meaning to the concepts of ‘the people’, ‘the elite’ and the obstacles to popular sovereignty guiding politics; whether they seek (2) economic and (3) political inclusion of excluded segments of society or, rather, seek to exclude parts of society from the economic and political sphere on behalf of a smaller in-group (March Reference March2017; Stavrakakis, Andreadis and Katsambekis Reference Stavrakakis, Andreadis and Katsambekis2017). Put differently, populists differ according to the discursive construction of core populist ideas and the host-ideological content of political or economic exclusion and inclusion.Footnote 2

Discursive exclusion and inclusion ‘essentially alludes to setting the boundaries of ‘the people’ and, ex negativo, ‘the elite’ (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013: 164, emphasis in original). While all populists vertically separate a ‘people’ from an ‘elite’, exclusionary and inclusionary populists take different approaches to horizontally differentiating among the population in order to define ‘the (morally true) people’ and their antagonists (Ivaldi, Lanzone and Woods Reference Ivaldi, Lanzone and Woods2017; March Reference March2017). Exclusionary populists advance a discourse of horizontal exclusion which restricts ‘the people’ to a national, ethnic or otherwise defined sub-group of the population, and casts others as outsiders to this ‘true’ people (De Cleen and Stavrakakis Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017). In contrast, inclusionary populists discursively build a more comprehensive popular identity going beyond the existing status quo (Ivaldi, Lanzone and Woods Reference Ivaldi, Lanzone and Woods2017; Mouffe Reference Mouffe2018). Such a discourse advances an inclusive conception of ‘the people’ independent of their differences, built on the exercise of collective sovereignty by the marginalised vis-à-vis an elite with allegedly outsized influence (Aslanidis Reference Aslanidis2018b; Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis Reference Katsambekis, Kioupkiolis, Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis2019).

Beyond their discursive core, exclusionary and inclusionary forms of economic and political host-ideology can be distinguished between populists. The economic dimension of ideology relates to different solutions to distributional questions. Hence, economic exclusion and inclusion ‘refer to the distribution of state resources, both monetary and non-monetary, to specific groups in society’ (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013: 158). Economic exclusion refers to reducing the provision of public resources to some parts of the population, whereas economic inclusion means calling for an increased use of public funds to support segments of society. Finally, the political dimension of ideology is a struggle between different visions for who can legitimately partake in the democratic contest. Political exclusion and inclusion thus ‘refer essentially to […] political participation and public contestation. Political exclusion means that specific groups are prevented from participating (fully) in the democratic system and they are consciously not represented in the arena of public contestation. In contrast, political inclusion specifically targets certain groups to increase their participation and representation’ (ibid 161).

Traditionally, populists were seen as neatly categorised into exclusionary and inclusionary ‘right’ and ‘left’ versions across these dimensions (March Reference March2017). However, because of historical changes in the structure of political conflict, this may no longer apply. Populist contestation takes place in a historical context of transnational politicisation, defined as a process where societies render transnational issues such as immigration, international integration and economic globalisation objects of public political conflict (Zürn, Binder and Ecker-Ehrhardt Reference Zürn, Binder and Ecker-Ehrhardt2012; Hutter, Grande and Kriesi Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016). Due to more salient and polarised contestation on transnational issues and institutions, a new dimension of political conflict which is orthogonal to the classic left–right dimension has solidified in recent decades (de Wilde, Leupold and Schmidtke Reference De Wilde, Leupold and Schmidtke2016: 4). This ‘transnational’ cleavage consists of a divide in societal attitudes between ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘communitarian’ ideologies or between economic, political and cultural ‘integration’ and ‘demarcation’ (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2012; Hooghe and Marks 2017; De Wilde et al. Reference De Wilde2019). Hence, ‘this divide pits cosmopolitan parties and voters on both the left and right advocating an inclusionary and international outlook […] against [communitarian] parties and voters on both the left and right that are increasingly wary of open borders and international influences’ (De Vries Reference De Vries2017: 1542).

Transnational politicisation implies that populists can ideologically vary also on a transnational dimension which explicitly addresses issues and institutions of GC: the key constitutional questions of who should have political rights and who can contest to receive which share of economic resources can then be answered not only nationally (e.g. only white wealthy men, or also other groups in society?) but also with regard to transnational inclusion or exclusion (e.g. of refugees, migrants or other countries’ citizens and representatives).

As a result, four distinct varieties of populism are apparent in such conditions, with variable views on constitutional frameworks beyond the state. Both neo-socialist and neoliberal populists on the economic dimension can exhibit politically exclusionary characteristics pertaining to communitarian host-ideology. In both cases, such populism would seek to reduce political participation and contestation rights for citizens and residents beyond the discursively constructed ethno-national sub-group of ‘the people’. Where such a contestation can be observed, we can speak of a communitarian type of populism.

Mirroring these versions, more transnationally inclusive types of left and right populism can also be conceived. As de Cleen argues, international populism would refer to ‘international cooperation between nationally organized populist parties and movements’ whereas transnational populism even ‘constructs a transnational people-as-underdog as a political subject that supersedes the boundaries of the nation-state’ (2017: 355).Footnote 3 Different degrees of populist transnationalism can thus range from nationalist communitarianism via internationalism to cosmopolitanism. This cosmopolitan type of populism in favour of political rights beyond the state can again feature either neo-socialist or neoliberal economic views.

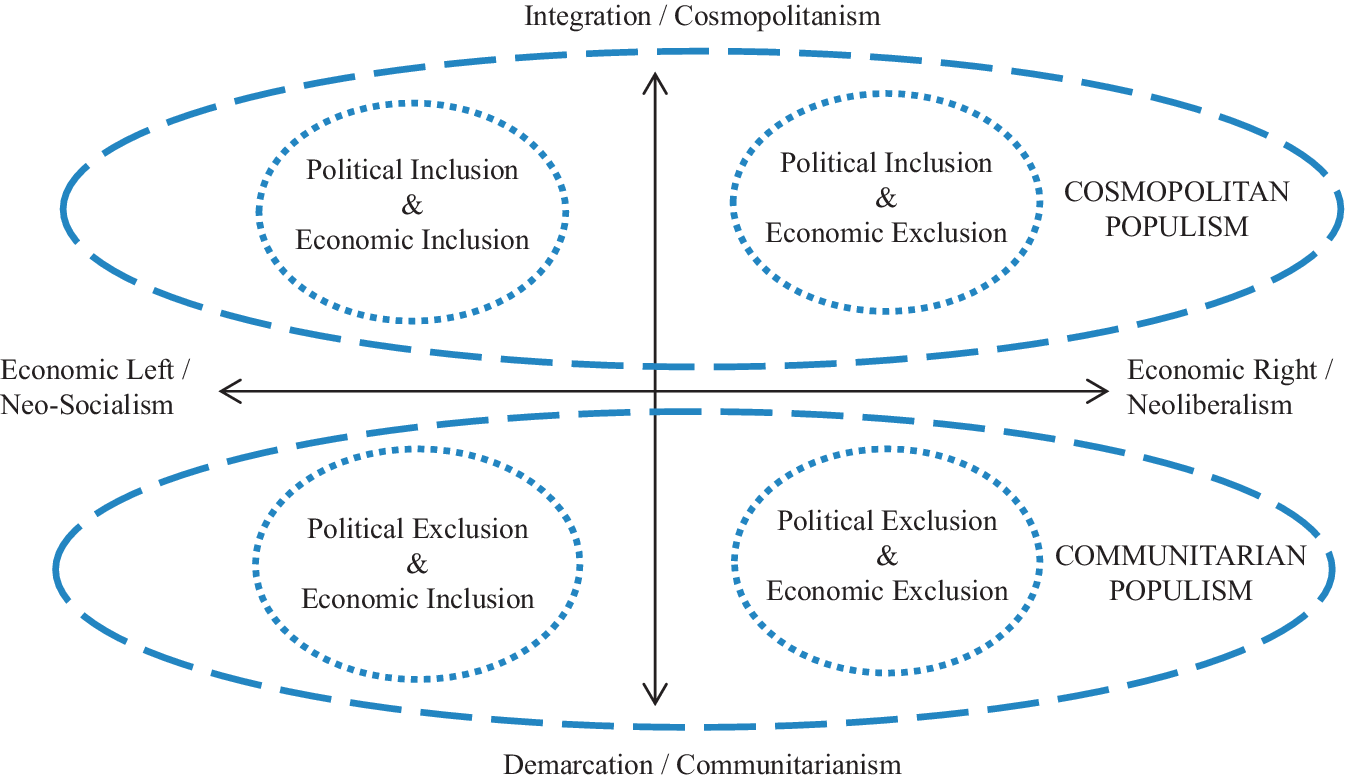

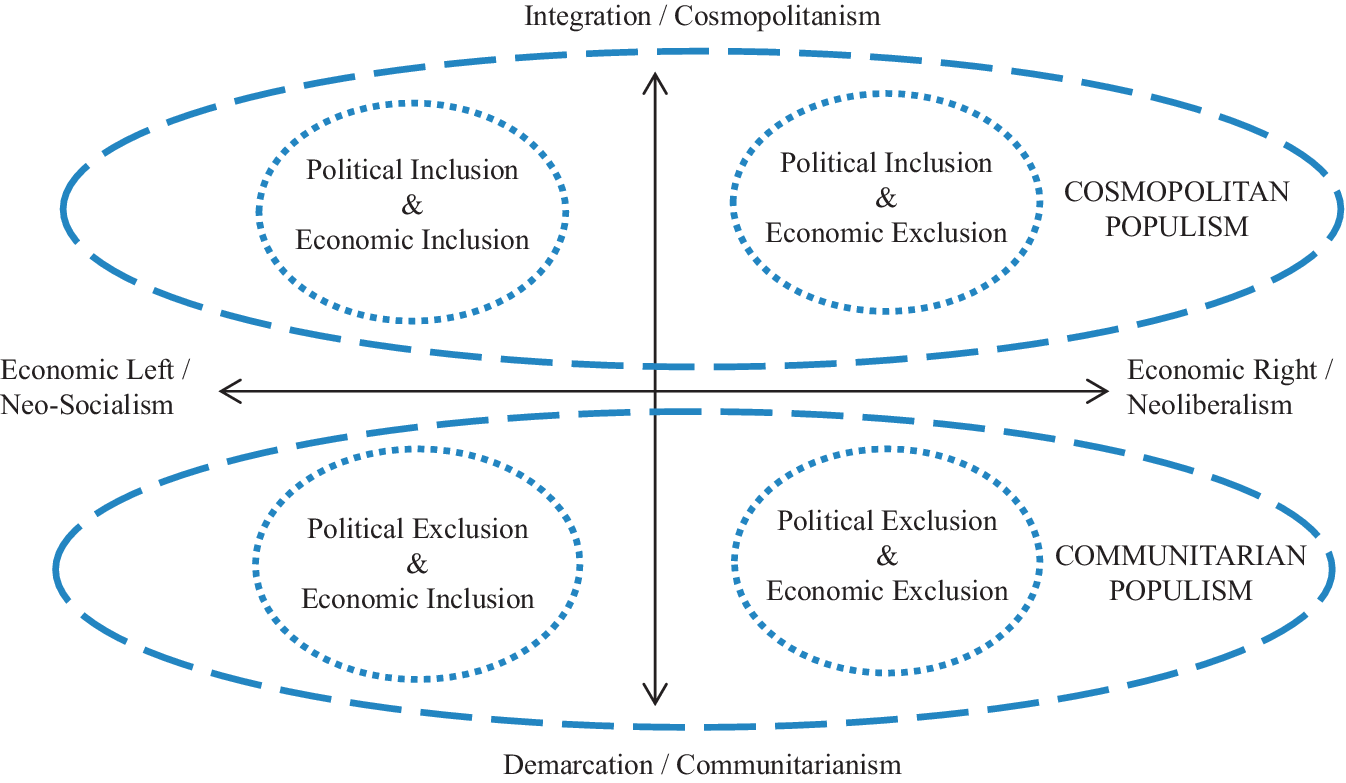

In sum, four ideal-typical varieties of populism may therefore be identified in such conditions (see Figure 1). The bottom right quadrant denotes a purely exclusionary populist challenge that is communitarian and neoliberal in ideology. This version would be opposed to constitutional frameworks enshringing political rights beyond the state and in favour of restricting rights to economic redistribution. Most strongly contrasting this version is a purely inclusionary populism on the top left, which uses cosmopolitan and neo-socialist host-ideology. This variety would be in favour of political rights beyond the state and campaign for rights to political intervention in the economy. Additionally, mixed forms of populism exist: these can contest on the one hand on behalf of cosmopolitan and neoliberal ideology, supporting political rights at the global level with restricted rights to politically interfere in the operation of markets. Finally, on the contrary, populists can also advocate for economic neo-socialism on the domestic level, while maintaining communitarian political exclusion transnationally. This variant would oppose political rights beyond the domestic state but seek to redistribute economic resources nationally.

Figure 1: Two-dimensional ideological space and types of populist contestation under conditions of transnational politicisation.

IV Transnational varieties of populist contestation

This section empirically illustrates the transnational typology through a series of exploratory case studies, before analysing contemporary populists’ relationship to principles of GC. On the basis of party manifestos and leader discourse of populist actors during the process of electoral emergence, I first discuss the two versions of communitarian populism, before considering the two cosmopolitan incarnations.

Communitarianism populism

Communitarian types of populism extend an exclusionary populist contestation to institutions of GC. In this type’s discourse, society is portrayed as divided into an ethno-national ‘people’ whose sovereignty is obstructed by a morally corrupted elite which serves itself, migrants or foreigners (Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2017). Such populists exclude particular groups or individuals from the morally legitimate group of ‘the people’ to protect or increase ‘natives” share of political influence and economic resources in a society seen as zero-sum (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). Populist discourse is thus combined with politically exclusionary host-ideology to advance either neoliberal or neo-socialist versions of communitarian populism.

Communitarian neoliberal populism: The ‘Alternative for Germany’

Neoliberal versions of communitarian populism argue that resources should be withheld or revoked from undeserving out-groups at home and abroad by reducing social welfare support or public money for minorities (de Koster, Achterberg and van der Waal Reference de Koster, Achterberg and van der Waal2013; Schumacher and van Kersbergen Reference Schumacher and van Kersbergen2016). Claiming that hard-working ‘native people’ are being exploited, lower taxes and reduced state interference to the benefit of ‘the people’ is promised, highlighting the economically neoliberal ideology employed by these populists (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1997).

The German Alternative for Germany (AfD) serves as an illustrative case of neoliberal communitarian populism. Formed in 2013, it broke through electorally in 2014. Though its hasty first manifesto from September 2013 was very sparse, it already demanded in populist fashion that ‘the people should determine the will of the parties, not the reverse’, called for ‘strengthening of democracy and democratic civil rights’ and for introducing ‘popular referenda and initiatives’ in particular on transfers of sovereignty to the EU (AfD 2013: 2). Denigrating an illegitimate political elite, ‘parties’ were claimed to ‘rule over’ the political system while ‘sand is deliberately thrown in the eyes of citizens’ (AfD 2013: 2–3). The first full manifesto of 2017 elaborated on these popular antagonists, stating that ‘a small, powerful political oligarchy which has developed within existing political parties’ was the ‘secret sovereign in Germany’ and is responsible for ‘the negative developments of recent decades’ (AfD 2017: 7). Allegedly, a ‘political class had formed whose primary interest is in its power, its status and its material welfare’, holding ‘the levers of state power, political education and informational and medial influence on the population in its hands’ (ibid).

Beyond established parties, ‘the people’ were painted as exploited by the allegedly inflation-inducing European Central Bank (ECB), and by ‘banks, hedge-fonds and private large-scale investors’ as the main benefactors of government policy (AfD 2013: 1). Similarly, ‘Brussels bureaucracy’ was blamed as intransparent and ‘detached from citizens’ and the European Parliament as having ‘failed in the control of Brussels’ (ibid 2). Later, the AfD expanded under the heading ‘without popular sovereignty, no democracy’ that the ‘untouchable popular sovereignty’ had been interfered with by European integration without a ‘European people’, a process which allegedly ‘limits or permanently destroys […] democratic nation-states’ and made ‘German citizens the paymaster of Europe’ (AfD 2017: 6–7).

In opposition to this elite at home and in Europe, ‘the people’ have to ‘return to being sovereign’ according to the AfD and receive ‘the right to look deputies over the shoulder’, to change or decline ‘the flood of’ parliamentary laws which are ‘often without sense’ and be empowered to ‘initiate and confirm’ laws by popular referendum (AfD 2017: 7). Indeed, ‘only the Staatsvolk [lit. state people] of the Federal Republic of Germany can, via the tools of immediate democracy, end this illegal state of affairs’ (ibid) according to the AfD. In ‘contrast to the CDU and its chancellor [Merkel], we believe the German people to be responsible and able’ to decide ‘fateful decisions of the nation with more foresight and sense of common good than power- and interest-guided professional politicians’ (AfD 2017: 8). Beyond domestic politics, the AfD pronounced that ‘every people should be allowed to democratically decide about its own currency’, that savings of ‘the citizen’ must not be ‘devoured’ by inflation, and that ‘the tax-payer’ should not bear Euro bailout costs (AfD 2013: 1).

The exclusionary character of the AfD’s discourse was apparent from the start. Already the 2013 manifesto decried ‘unordered immigration into our social security systems’ and a need for ‘qualified migration willed to integrate’ (AfD 2013: 4). This exclusion of ethno-national outsiders was expanded in the 2017 programme, where it claimed to work on behalf of ‘big accomplishments of European civilisation’ brought about by ‘Christian and humanist culture’ (AfD 2017: 10) and in defence of a ‘German lead culture instead of multiculturalism’, citing language, customs, traditions, cultural history and values (AfD, 2017: 46). In separation from it, the AfD stated that ‘Islam does not belong to Germany’ and that ‘its spread and the presence of more than 5 million Muslims whose number constantly rises’ presents a ‘big danger for our state, our society and our value system’ (AfD 2017: 33). Indeed, it proclaimed the threat of ‘further destruction of European values’ through an ‘already ongoing culture fight between occident and Islam [and its] non-integratable cultural traditions and legal commands’ (AfD 2017: 46). Further, the programme paints a dark picture of ‘foreigners’ criminality’, terror and exploitations of the automatic birthright to German citizenship for instance through ‘members of criminal clans’ (AfD 2017: 22) and ‘mostly unqualified asylum applicants’ (AfD 2017: 27–8).

Further exclusionary discourse was apparent towards progressive gender roles and sexual minorities. As such, the AfD campaigned in favour of ‘traditional families’, stated that single parents are ‘not an ideal case’ for whom special public support should be curtailed, and claimed that ‘gender ideology marginalises natural differences between sexes and questions sexual identity’, seeking to ‘get rid of the classical family as life model and role script’ (AfD 2017: 39). ‘So-called quota rules’ for gender-based affirmative action as well as anti-discrimination laws allegedly intrude on legal equality and private individuals’ freedom of contract (AfD 2017: 11). It also denounced initiatives such as the ‘equal pay day’ or gender-sensitive language as ‘propaganda activities’ and sexual education in schools as an ‘ideological experiment in early sexualisation’ on behalf of the ‘sexual leanings of a loud minority’ (AfD 2017: 39–40).

Derived from such exclusionary populist discourse, communitarian host-ideological responses abound, exemplified by the promise of ‘self-conservation, not self-destruction of our state and people’ (AfD 2017: 28). In this vein, the AfD insisted on a ‘re-ordering of immigration law’ (AfD 2013: 4) and an ‘immediate closing’ of borders to ‘immediately end’ the supposedly ‘unordered mass immigration’ (AfD 2017: 28). Further berating immigrants, ‘the successful adjustment of all of these people, including a substantial share of analphabets, is impossible’ according to the AfD, justifying a need for ‘several years of negative migration’ (ibid). Demanding ‘national sovereignty regarding every form of immigration’, the AfD claimed that ‘mass abuse of asylum rights must be ended by reforming German basic law’ and demanded ‘re-negotiating’ the ‘outdated’ Geneva convention ‘and other supra- and international agreements’ to ‘adjust them to the threat to Europe from population explosions and migration streams of the globalised present and future’ (AfD 2017: 29). Ending rights to family reunion for refugees, defining absolute maxima for annual migration and strongly restricting citizenship rights for migrants and their descendants are further policy planks justified on communitarian grounds (AfD 2017: 30–1).

Beyond immigration, the AfD also opposed a ‘centralised European state’ and called to ‘return legal competences to national parliaments’ (AfD 2013: 1–2), as well as demanding a popular referendum about German membership in the Euro and ‘potentially in the EU’ (AfD 2017: 7–8). It called for putting an end to trade and foreign investment inducing ‘the sell-out of knowledge produced in our country over generations’ as well as to trade agreements like TTIP which contain supranational courts (AfD 2017: 18–19). Regarding transnational climate politics, the AfD programme sowed doubts about the scientific authority of the UN’s IPCC and called for the termination of the 2015 Paris Climate Accords and a German exit from and the abolition of all support to ‘all public and private “climate protection’ organisations” (AfD 2017: 64).

Promoting a neoliberal version of communitarianism, suppressing public spending by respecting the constitutional public ‘debt brake’ and reducing German ‘mountains of debt’ as well as ‘drastically simplifying the tax code’ is favoured by the AfD (AfD 2013: 2). It later expanded that a ‘reduction of tax- and social security contribution rates’ and ‘dismantling of bureaucracy’ was its target as well as the reduction of subsidies and ‘unnecessary public expenses’ (AfD 2017: 49). It also demanded an end to inheritance tax in its current form and no reintroduction of a wealth tax (ibid 50). Additionally, all ecological subsidies as part of the German energy transition are to be ‘scrapped without replacement’ while nuclear, gas and coal power plants should remain on grid to ‘not overburden the economy and citizen’ and green technologies like electromobility are to develop, ‘like every technology, on the basis of market economics’ (AfD 2017: 65).

Beyond domestic politics, the AfD called in neoliberal fashion for reforming the EU to ‘reduce Brussels bureaucracy’ and slim it through ‘more competition and self-responsibility’ (AfD 2013: 2). It demanded quitting the alleged ‘transfer union’ and dismantling or leaving the Euro area as well as preventing any potential risk-sharing for non-German banks and deposits and any further ‘arbitrary’ bailout programmes (AfD 2017: 7–8). Similarly, it aims at forbidding the ECB from intervening in financial markets by buying public ‘junk bonds’ and ‘expropriating savers and pensioners’ through active monetary policy (AfD 2013: 1, 2017: 13–14).

In sum, the AfD clearly illustrates a communitarian and neoliberal type of populist contestation. Its discourse divides society between an elite of established parties, progressive gender ideologues and Eurocrats on the one hand, and the upright German ‘people’ of tax-paying citizens whose sovereignty is allegedly thwarted on the other. It defined ‘the people’ exclusively in traditional ethno-cultural terms, portraying migrants, refugees, Islam, sexual minorities and women beyond traditional gender roles as outsiders which encroach on the ‘popular’ will. Advancing a communitarian vision of national sovereignty, it opposed immigration, any further EU integration and concessions to global climate politics. In line with neoliberal convictions, it demanded downsizing the German tax state, preventing any financial risk-sharing in Europe as well as public fiscal and monetary policy actively intervening in markets.

Communitarian neo-socialist populism: The ‘Law and Justice Party’

A second version of communitarian populism emphasises an alleged ethno-popular oppression through an allegedly privileged and ‘do-gooder’ elite which seeks to please international markets and financially support migrants and foreigners, denying the ‘common man’ its fair economic share of societal resources (Shields Reference Shields2012). The construction of the ‘elite’ takes a more capitalist turn in this variety, demonising financial market links and ‘global capital’ (Kalb Reference Kalb2018).Footnote 4 In turn, the construction of ‘the people’ is more class-based in this kind of populism, while retaining the focus on an ethno-culturally demarcated subset of economically lower classes (Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall.2017). Ideologically, it thus combines political communitarianism with neo-socialist economic views.

As a case of this version of populism, the Polish Law and Justice Party (PiS) is illustrative. Having turned towards populist discourse ahead of the 2005 elections, PiS went on to govern in a coalition with the agrarian ‘Self-Defence’ and the religiously conservative ‘League of Polish Families’ (LPF). Taking up economically inclusionary discourse from the originally left-wing Self-Defence and outbidding the LPF on cultural conservatism, it eventually forced both coalition partners out of the Polish political system altogether. While this contributed to the party losing its governing majority in the (early) 2007 elections, a strengthened PiS won an outright majority in the 2015 elections, governing the country since (Stanley Reference Stanley2018).

Combining inclusionary and exclusionary populist discourse, PiS developed a radical critique of ‘the political decisions of the elites at the time’ which were ‘choosing the wrong path of transformation after the 1989 system change’, leading to ‘beneficiaries under such capitalist conditions [having] become undeservedly privileged’ (PiS 2005: 7). The ‘old state and informal apparatus’ originating from Communist-era ‘influences and secret links to the Special Services’ allegedly operated through ‘informal and often interpenetrating cliques and interest groups including powerful pressure groups [such as] the banking and import lobby’ (ibid). Decrying a ‘lack of resistance to corruption and particularistic and premeditated group interests’ (ibid) as ‘one of the most serious diseases affecting the Third Polish Republic’ (ibid 18), it branded those elites for tolerating escalating regional and social inequality resulting from neoliberal ‘shock therapy’ in the 1990s and for sacrificing the rural population and catholic values. Decrying an alleged moral ‘crisis of polonism and patriotism’, a ‘crisis of values connected with the sense of national belonging’ (PiS 2005: 10), it further stigmatised liberal urbanites and called out the post-1989 ruling parties as ‘definitely anti-family’, alleging they ‘put in place rules that actually encourage young people to premature sexual intercourse’ and started to ‘work on a law legalising homosexual marriage, without excluding the possibility of adopting children in such relationships in the future’ (PiS 2005: 118).

In contrast to post-Soviet elites, PiS claimed to campaign on behalf of the marginalised ‘vast majority of Poles’ who ‘had to bear the costs of transformation’ (PiS 2005: 8), placing itself discursively with ‘ordinary Poles’ (PiS 2005: 12). In communitarian fashion, PiS promised that ‘words like homeland, Poland, Poles, neighbours, human dignity are not just empty sounds for most of us’ and that they believe ‘in a revival of a sense of community and a spirit of solidarity and a social and Christian neighbourly love’ (PiS 2005: 13).

Laying out its exclusionary view of ‘the people’, PiS campaigned on behalf of traditional, patriarchal and hierarchic social values seen as central to ‘national culture [as] the source of national identity transmitted from generation to generation’ (PiS 2005: 105), while excluding female participation and contestation, rights of homosexuals, as well as those of ethnic and religious minorities. Accordingly, ‘PiS, seeing in Christian values that form the basis of […] our cultural sphere the foundation of a strong family, is against abortion and euthanasia’ and in favour of ‘state-run family-oriented policies […], strengthening desirable patterns of family life and ethics’, while warning of certain ‘pathological phenomena in families’ (PiS 2005: 81) and ‘social pathologies’ seen as also caused by ‘modern cultural trends’ (ibid 124). Overall, PiS demanded ‘resolute responses by public authorities to manifestations of violation of the moral order’ (ibid), including a ‘law on protection of the citizens’ peace, introducing severe and prompt enforcement of penalties for anti-social behaviour, […] such as violating the peace and infringements of order, silence, morality, etc.’ (PiS 2005: 29).

This discursive exclusion reverberates in its communitarian ideology. According to PiS, it was necessary to oppose ‘attempts to impose the supremacy of European Law on national institutions as well as the lack of consent to the issues of morals and moral laws which are regulated by European law and not left in full responsibility of the Member States (ibid 43). The process of EU identity-building was seen as in practice ‘imposing the identity of the stronger nations on the weaker nations’ (ibid 9). On such communitarian grounds, PiS opposed the draft Constitution for Europe for ‘giving too many new competences’ to EU institutions and ‘lowering the rank of the [Polish] Constitution’ (ibid 42). Specifically, the EU constitution was allegedly ‘denying the role of Christianity in moral and cultural formation of our continent’, introducing ‘a kind of anti-Christian censorship’ and showing that ‘the Union has departed from the values that guided the European founding fathers’ and is ‘experiencing a crisis of cultural identity’ (ibid). Quoting pope John Paul, PiS alleged that such a ‘democracy without values easily turns into open or thinly disguised totalitarianism’ (ibid). Poland, instead, should take its place in the EU to ‘revive Europe with the spirit of Christian solidarity, expressed in human rights, the rights of the family and the rights of nations’ (ibid).

Regarding European institutions, PiS further declared itself ‘afraid of the Union’s domination by the strongest, most populous and economically most powerful states’ (PiS 2007: 27) and ‘in favour of strengthening the role of [the Polish parliament]’ to face ‘the threat of creating rights outside [its] control, which is contrary to the fundamental principle in the constitution namely the sovereignty of the Polish nation’ (PiS 2005: 46). Accordingly, it was ‘opposed to replacing sovereign states and creating a European superstate structure’ (ibid 44), as well as to ‘imposing the common currency on Poland until the costs of monetary union will be definitely lower than the possible benefits’ (ibid 63). Generally, according to PiS, ‘all EU competences arise from sovereign decisions of countries’, such that its overall EU vision was that ‘the most important decision-making institutions […] should remain the European Council and Council of the EU’ while ‘maintaining the unanimity rules’ on treaty change, thereby ‘preserving independence of Polish economic policy within the common market’ and ‘confirming the role of national governments and national parliaments’ to bring the EU ‘closer to the average citizen’ (PiS 2005: 43–4).

Economically, the PiS brand of populism calls for a more socially sensitive and less market-dominated type of capitalism. In contrast to post-1989 governments who are decried as having ‘significantly reduced taxes and social security contributions’, key tenets of their programme became ‘increasing social benefit payments, […] raising the minimum wage, increasing expenditures on child nutrition and benefits to worse-off families’ (PiS 2007: 1). Increasing investments in infrastructure, expanding the public health and education system as well as ensuring ‘development through employment’ (PiS 2005: 12) were proposed as necessary, arguing that in a modern market economy, ‘we cannot deprive the state of influence and responsibility for the social order, in particular for the weakest social groups whose situation as a result of the transformation has been rapidly deteriorating’ (ibid: 113–14). Blaming austere fiscal policy pursued by the previous governments in their goal of acceding the Eurozone for requiring ‘further sacrifices [from citizens] to tighten the belt’, such that ‘everyone paid for it in their own way’, PiS promised instead to actively address the ‘embarrassing […] disgrace’ of unemployment, deprivation and poverty (ibid 8). Further, PiS opposed the Euro and full international market liberalisation because of ‘too strong competitive pressure’ without ‘preparing companies for competition on global markets [so that] it will not weaken the competitiveness of Polish exports’ (PiS 2005: 63).

In sum, PiS illustrates the communitarian and neo-socialist type of populist contestation well. Relying on an exclusionary discourse elevating ‘ordinary Poles’ defined according to traditional Christian values, it demonised the ruling liberal post-1989 elite for their openness to liberal causes such as rights of homosexuals and for tolerating the inequality produced by neoliberal market integration in the 1990s. In response, PiS advocates a more communitarian and neo-socialist Polish ideology, defending national ‘popular’ sovereignty over Catholic values and protectionist, redistributive economic policy.

Cosmopolitan populism

In contrast, cosmopolitan populism extends an inclusionary populist contestation to institutions of GC. This type relies on a discourse of popular integration beyond the nation state against corrupted elites portrayed as serving particularistic domestic interests (De Cleen Reference De Cleen and Kaltwasser2017; Ingram Reference Ingram and Kaltwasser2017). Ideologically, it thus exhibits a cosmopolitan host-ideology which can be used to advance either neo-socialist or neoliberal economic agendas.

Cosmopolitan neo-socialist populism: DiEM25

Neo-socialist cosmopolitan populism associates international and transnational economic and political elites with maintaining an undemocratic global order from which they allegedly benefit at the expense of ‘ordinary people’ (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2017). In opposition to this elite, ‘the people’ are constructed as sharing a united identity across national borders and citizenship limits by jointly being exploited economically and oppressed politically (Ingram Reference Ingram and Kaltwasser2017). Given this transnational problem constellation, neo-socialist cosmopolitan populists emphasise more majoritarian decision-making in political institutions beyond the nation state to redress perceived undemocratic tendencies in IOs and to change the economically neoliberal character of international constitutional order.

At the level of political parties, this type of populism is rare given the dearth of transnational democratic electoral arenas. However, the recently formed Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25) can serve as an illustrative case. Founded as a ‘pan-European platform’ in 2015 by Yanis Varoufakis, formerly SYRIZA’s Finance Minister for Greece, it has since evolved into a transnational party which contested the EP elections in May 2019 and won its first parliamentary seats in the Greek election of July 2019.

Its populist discourse is evident in its founding manifesto: the ‘Powers of Europe’ consisting of ‘unaccountable “technocrats”, complicit politicians and shadowy institutions’ are decried as allegedly seeking ‘to deny, exorcise and suppress, […] co-opt, evade, corrupt, mystify, usurp and manipulate democracy’ (DIEM25 2015: 2, 7). In a long list, the opposed ‘deep establishment whose failed policies lead it to authoritarianism’ is explicitly specified as amongst others ‘the Brussels Bureaucracy (and its more than 10,000 lobbyists)’ and ‘the Troika they formed together with unelected technocrats from other International and European Institutions’, ‘bailed out bankers, fund managers […], political parties [which] betray their most basic principles when in government’, as well as ‘media moguls who have turned fear mongering into an art form, and a magnificent source of power and credit’ (DIEM25 2017: 4). Indeed, according to DiEM25, ‘a confederacy of myopic politicians, economically naïve officials and financially incompetent experts submit slavishly to the edicts of financial and industrial conglomerates, alienating Europeans’ from the ‘Brussels democracy-free zone’ (DIEM25 2015: 2–3).

In opposition to this elite declared as morally corrupt for ‘asphyxiating democracy’, its discourse pits the European ‘peoples’ (ibid 4–5) with ‘a duty to regain control over our Europe’ (ibid 7). The main self-declared goal is ‘a democratic Europe in which all political authority stems from Europe’s sovereign peoples’, proclaiming that ‘We are forming DiEM25 intent on moving from a Europe of “We the Governments”, and “We the Technocrats”, to a Europe of “We, the peoples of Europe”’ (ibid 7–8). In inclusionary fashion, the movement-party claims to ‘come from every part of the continent and [be] united by different cultures, languages, accents, political party affiliations, ideologies, skin colours, gender identities, faiths and conceptions of the good society’ (ibid) and to seek advancing a ‘pluralist Europe of regions, ethnicities, faiths, nations, languages and cultures’ as well as an ‘Egalitarian Europe that celebrates difference and ends discrimination based on gender, skin colour, social class or sexual orientation’ (ibid 8).

In response, a politically and economically inclusionary host-ideology is advanced. Politically, the movement-party proclaimed itself ‘committed to’ building ‘a real democracy […] at a transnational European level’ (DIEM25 2017: 8). To that end, it wants to ‘promote a Constitutional Assembly Process, involving representatives elected on transnational tickets, to manage the evolution of Europe into a democratic political entity and the replacement of all existing European Treaties with a democratic European Constitution’ (DIEM25 2017: 9). Relatedly, already its candidacy at the recent EP and Greek elections expanded political inclusion beyond national borders: while transnational lists were not officially allowed, DiEM25 ‘simulated’ such lists by agreeing on a common programme beforehand while running with national organisational and legal structures campaigning on behalf of it. DiEM25’s electoral alliance also sought to ‘strengthen the European Parliament’ for instance through right of initiative, expand direct-democratic instruments such as the European Citizen’s initiative and bolster ‘fundamental rights against member-state governments who try to take them away’ by introducing a watchdog commission investigating on behalf of the ECJ (European Spring Reference Spring.2019: 7–8). Further cosmopolitan political demands include a commitment to advance global climate policy commitments under its ‘Green New Deal’ as well as respect for human rights of migrants and refugees, expansion of legal migration and a common European Asylum Policy (European Spring Reference Spring.2019: 6–11).

Clearly neo-socialist in economic ideology, DiEM25’s policy programme decries ‘the bitter price of austerity’, ‘ultra-low investment’ and ‘involuntary underemployment’ as central economic problems facing Europe (DIEM25 2017: 4). In response, its economic policy platform includes ‘re-politicising money creation’ and ‘funding a green investment-led recovery’ via central banks, public investment banks and new carbon-, finance- and wealth taxes, advancing a ‘Jobs Guarantee program’ as well as partly socialising returns on assets and technology-driven productivity gains of companies in the digital era (ibid: 10–11). Combining political and economic inclusion, DiEM25 advocates in favour of additional international institutions tasked with economic stabilisation and investment financed from a common, democratically legitimated budget as well as for ‘democratising’ technocratic institutions such as the ECB and the European Stability Mechanism (European Spring, Reference Spring.2019: 18–20).

In sum, DiEM25 constitutes an illustrative case of cosmopolitan neo-socialist populism. Discursively opposing Brussels technocrats and national governments seen as complicit with global neoliberal market forces, it campaigns on behalf of a transnational and pluralist vision of the ‘European peoples’ united in their exploitation and disenfranchisement. Accordingly, it advocated drastic expansions of democratic decision-making at the international level and large-scale public intervention in the economy to redress global neoliberalism’s perceived ills.

Cosmopolitan neoliberal populism: Alberto Fujimori

Finally, neoliberal versions of cosmopolitan populism discursively construct political elites as systematically in bed with special clientelistic interests from the organised working class, state-led enterprises and the broader taxpayer-money-hungry public bureaucracy (Sawer and Laycock Reference Sawer and Laycock2009). In opposition to this privileged and corrupted political class, such populism claims to represent a marginalised and disadvantaged class of ‘ordinary’ people without such connections (Roberts Reference Roberts1995). Ideologically, political participation and contestation in the market-society should be increased in cosmopolitan fashion for entrepreneurial citizens and transnational actors alike, be it by strengthening international investor rights or allowing migrant labour (Verbeek and Zaslove Reference Verbeek, Zaslove and Kaltwasser2017: 394–6). Economically, the focus is on protecting ‘the people’s’ individual resources from alleged state capture and redistribution to the privileged, as the state’s role in the economy is made responsible for individuals’ ills such as inflation, inefficiencies and cyclical crisis. Accordingly, the distorting state should be shrunk, taxes lowered and the market unleashed as the ‘legitimate instrument of the popular will’ (Sawer and Laycock Reference Sawer and Laycock2009: 134).

This type of politically inclusive but economically exclusive populism is rare in established liberal democracies and does not form part of the contemporary wave of populist challenges to GC. However, it can be illustrated with recourse to examples in 1990s Latin America. There, the second wave of neo-populist politics brought to power politicians like Alberto Fujimori in Peru, whose contestation is discussed in the Annex as an illustrative historical case (Roberts Reference Roberts1995; Weyland Reference Weyland1996).

V. Contemporary varieties of populism and the challenges to global constitutionalism

How do varieties of populism discursively challenge global constitutional principles? To address this question, I first focus on the contemporary versions of communitarian and cosmopolitan populism, before discussing pertinent cases with key ideological ambiguities in their contestations.

Communitarian populism: Contesting (neo-)liberal global constitutionalism

Communitarian populists like the German AfD or the Polish PiS advance a populist discourse by excluding those groups constructed as outsiders to the ‘ethno-national people’ from having equal rights to those of the populist in-group (Jenne Reference Jenne2018). The concerns of minorities, refugees, migrants, as well as citizens of other states and their representatives are not considered as equally legitimate and as standing in the way of following the ethno-nationalist ‘people’s’ interests in politics. Through their discourse, communitarian populism thus contests liberal democratic legitimacy by questioning constitutional protections of individual and minority rights, claiming that they undermine ethno-national popular sovereignty (Rummens Reference Rummens and Kaltwasser2017).

For GC, this version of populism therefore presents an illiberal challenge to international human rights and to rules-based multilateralism. Due to its zero-sum view of society, it seeks to reduce political rights of constructed ‘outsiders’ and undermine international legal institutions in their way. For instance, the AfD called to renegotiate the Geneva convention on international rights of refugees and asylum-seekers, wishing to privilege national sovereignty over immigration. Similarly, PiS opposed the European constitutional framework for not clearly privileging its interpretation of Christian cultural traditions and imposing pluralist values through legal supremacy beyond the state.

Two different versions of such communitarian populism became apparent: a neoliberal one which calls for economic exclusion from state resources domestically, too, and a neo-socialist one, which advocates for economic redistribution among its restricted, ethno-nationalist sub-group of ‘the people’.

Neoliberal communitarian challenges like the AfD’s do not as clearly oppose economic principles in global constitutional institutions where similar principles historically dominate. Rather, its challenge opposes the European constitutional framework on the basis of allegedly threatening to privilege Southern European and refugees’ rights ahead of ‘native’ German taxpayers’, desperately calling for respect of the neoliberal ‘no-bailout’ principle in the EU treaties. In communitarian fashion, a return to national fiscal, monetary and immigration policy is demanded to reclaim this vision of neoliberal economic policy, as (existing) global constitutional limitations on economic transfers are not trusted.

In contrast, as an example of neo-socialist communitarianism, PiS additionally challenges neoliberal economic principles of GC. The EU and Eurozone accession criteria imposing fiscal austerity are criticised as harmful to Poland and as unjustly limiting the capacities for social policy expenditures towards left-behind rural and unemployed parts of the population. Similarly, the strategic strengthening of domestic industry against European and global market competition runs counter to WTO and EU free market principles on trade. In addition to its illiberal communitarian challenge, PiS’ version of populism thus contests the legitimacy of neoliberal economic principles beyond the state binding domestic majority politics.

Beyond these cases, the nativist form of communitarianism exhibited by both AfD and PiS is associated with the contemporary populist radical right (Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2017). Examples range from neoliberal populist examples like the Spanish party ‘Vox’ via mixed cases of protectionism and deregulation like Donald Trump’s Republican party to neo-socialist projects like the French Rassemblement National under Marine Le Pen. While their economic views vary, this party family thus shares an illiberal and nationalist challenge to the global liberal principles of human rights and rule of international law.

Cosmopolitan populism: Contesting in support of liberal-democratic global constitutionalism

Cosmopolitan populists like DiEM25 advance an inclusionary populist discourse by complementing their anti-elitism with an emphasis on a transnational notion of ‘the people’. In contrast to communitarians, they do not seek to reduce political rights of a sub-group of the population. Rather, they call to expand individual rights transnationally and support more rules-based multilateralism in their discourse. For instance, DiEM25 called for expanding rights of migrants and refugees and bolstering EU citizens’ fundamental rights as well as for additional European institutions. Fujimori emphasised indigenous and gender equality rights as well as international investor rights (see Annex).

However, such cosmopolitan populism contests in favour of a distinct normative vision of GC. Historically, neoliberal cosmopolitans like Fujimori sought to enshrine only market principles and individual rights beyond the state (see Annex). In contrary, contemporary neo-socialist versions like DiEM25 favour binding politics through democratic rules of popular sovereignty at the international level and accordingly call for expansions of transnational democratic rights, too. For instance, DiEM25 called for strengthening citizen initiatives at the EU level, for giving legislative initiative rights to the EP and for democratic control over the technocratic ECB and the intergovernmental ESM. In its calls for further constitutionalising global politics, this contemporary version of cosmopolitan populism thus emphasises the majoritarian pillar of (transnational) popular sovereignty, but also the liberal political rights needed to exercise that sovereignty.

As such, neo-socialist cosmopolitan populism à la DiEM25 poses a cosmopolitan challenge on behalf of liberal democratisation as well as economic neo-socialism. A perceived neoliberal bent in normative economic principles of GC is seen by such populists as responsible for the corruption of democratic politics and unsatisfying economic outcomes in practice, not unlike the discourse voiced by their communitarian neo-socialist counterparts. Yet, in contrast to these, the political ideology they advance in response is drastically different, based on their transnational notion of ‘the people’. Accordingly, neo-socialist cosmopolitan populism challenges the democratic pillar of GC as being underdeveloped and incapable of reining in global markets which are seen to cause unequal material and political outcomes to which they are not democratically entitled. In response, cosmopolitan neo-socialist populists call to strengthen democratic principles beyond the state to bind politics.

This type of populism is rare given the complexities of constructing a transnational political identity and the dearth of transnational electoral arenas in global politics (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2017). However, outside the sphere of parties, transatlantic social movements such as Occupy and the Southern European anti-austerity Indignados employed a cosmopolitan and neo-socialist populism in opposition to neoliberal financial globalisation and Eurozone economic policy (Gerbaudo Reference Gerbaudo2017; Aslanidis Reference Aslanidis2018b).

Similarly, populist projects have used neo-socialist cosmopolitan discourse in other historical contexts. For instance, the initial challenge of Hugo Chávez in 1990s-Venezuela employed a transnational notion of a Bolivarian ‘people’ in Latin America, jointly opposed to perceived neoliberal US imperialism (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013). In response, his project advanced a regionalist agenda establishing alternative institutions of international integration to establish neo-socialist constitutional principles beyond the state (Kellogg Reference Kellogg2007; Verbeek and Zaslove Reference Verbeek, Zaslove and Kaltwasser2017).

Overall, thus, while cosmopolitan populism has historically also existed in versions supporting (neo-)liberal political principles beyond the state (see Annex), its contemporary challenge to GC is directed specifically against a perceived neoliberal bent in global normative principles and the dearth of democratic decision-making enshrined beyond the state.

Transnationally ambiguous populism: Neo-socialist contestations between global neoliberalism and national democratic politics?

Aside from highlighting contrasting versions of communitarian and cosmopolitan populist contestation, the typology also allows identifying important cases of populism which evince clear categorisation because they present transnationally ambiguous challenges to GC.

Most notably in contemporary politics, several pertinent populists from the traditional left remain ambivalent towards transnational dimensions of global politics and constitutional principles beyond the state.Footnote 5 For instance, while cosmopolitan populist movements informed the party-political challenges of Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren in the US, SYRIZA in Greece and Podemos in Spain, these populists advance inclusionary contestations which oppose mainly ‘the 1 percent’ and domestic ‘establishment’ politicians corrupted by them (‘the casta’ in Southern Europe) to a diverse body of ‘people’ as exploited workers and disenfranchised citizens.

Ideologically, these populists challenge neoliberal principles of GC without offering explicitly cosmopolitan responses. Rather, their contestation focuses on domestic political institutions and partly uses communitarian rhetoric vis-à-vis global issues (Halikiopoulou, Nanou and Vasilopoulou Reference Halikiopoulou, Nanou and Vasilopoulou.2012). The campaigns of SYRIZA and Podemos, for instance, emphasised domestic opposition to principles underlying Eurozone institutions and the Troika bailout programmes, without providing a cosmopolitan contestation of transnational reform if such resistance fails (Stavrakakis and Katsambekis Reference Stavrakakis and Katsambekis2014; Kioupkiolis Reference Kioupkiolis2016). Indeed, in the case of SYRIZA, acquiescing to the Troika demands despite the July 2015 referendum results directly led to Varoufakis leaving the party and forming DiEM25 as a more cosmopolitan populist alternative.

More generally, left populists like the Dutch Socialist Party and the German Left Party remain torn between an internationalist outlook in principle and sometimes fundamental opposition to global constitutional projects like the EU in practice for their perceived neo-liberal character (see Beaudonnet and Gomez Reference Beaudonnet and Gomez.2017: 5–6). Similarly, Jeremy Corbyn’s populist Labour party leadership essentially fudged its position on Brexit since the 2016 referendum because of divisions between segments of the membership and electorate, officially announcing a partial ‘Remain’ position only three years later (Labour Party Reference Party2019).

Overall, such cases of transnationally ambiguous populism on the left appear to be caught between two contending impulses: on the one hand, they share the criticism of global neoliberalism and its democratic effects advanced by its cosmopolitan neo-socialist counterparts. On the other hand, they focus on restoring popular sovereignty in national democratic politics instead of transnational arenas and advance a socially protectionist challenge towards international institutions and their perceived neoliberal bias rather than explicitly campaigning for their democratisation.

VI. Discussion and implications

The variety of contemporary populist challenges suggest broader implications for GC. First, populism challenges contemporary GC from three distinct normative angles, which illustrate the contours of an emerging discursive contest over GC’s democratic legitimacy. Second, populist contestation therefore politicises the process of constitutionalisation beyond the state, with ambivalent and politically contingent institutional trajectories for GC.

Contemporary varieties of populism and the discursive contest over global constitutionalism

While contemporary populist discursive contestations all challenge global non-majoritarianism, the analysis showed that they relate to principles of GC in ambivalent ways which depend on their host-ideological variety. Specifically, three contemporary populist challenges became apparent: a communitarian one, a cosmopolitan one and a neo-socialist one.

On the one hand, communitarian populists advocate an illiberal and nationalist vision of majoritarian rule on behalf of their exclusive notion of national popular sovereignty. These versions attack GC’s liberal pillar of individual rights and legal institutions guarding these. As such, communitarian populists clearly threaten global de-constitutionalisation in a way which undermines liberal and democratic principles. For instance, US president Trump pulled out of the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council over its criticism of his dehumanising immigration policy and blocked the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Appellate Body to conduct bilateral trade negotiations and impose tariffs outside the constitutional framework protecting weaker states from strong-arm tactics. Similarly, the Hungarian and Polish populist governments undermined human rights norms in the context of the migration crisis and legal independence as guarded by the EU treaties, illustrating this illiberal nationalist trajectory.Footnote 6

In contrast, contemporary cosmopolitan populists mount a neo-socialist challenge on behalf of transnational popular sovereignty, against GC they perceive as undemocratically (neo-)liberal. These versions support principles of GC but favour binding global politics through liberal and democratic principles of popular sovereignty, discursively outlining a trajectory of global constitutional democratisation. Most prominently, such a trajectory is currently thinkable in the EU, which for all its democratic discontents remains globally unrivalled in terms of opportunities for majoritarian influence. There, cosmopolitan democratisation attempts to transnationalise EP elections exist by common platforms, candidates and electoral lists of new types of populist parties like DiEM25, but also by the non-populist pan-European party ‘Volt’. Similarly, Green parties have long advocated for democratic cosmopolitan reform and their electoral surge may strengthen such a trajectory.

Finally, neo-socialist populists which are divided between communitarian or cosmopolitan versions promote a more socially sensitive economic constitutional order for the marginalised ‘people’ they claim to represent. While sharing the contestation of global neoliberal constitutionalisation, especially populists of the traditional ‘left’ remain ambiguous regarding transnational issues and institutions and only selectively support global constitutional principles of international rights and rules-based multilateralism.

In interpreting these findings, some points merit further discussion. First, populist ideology (like any other) may change over time. For instance, Marine Le Pen’s leadership has altered the French Front National’s (now renamed Rassemblement National) formerly neoliberal economic position towards a neo-socialist stance. Similarly, neo-socialist populists may also take on more exclusionary ideology. In the case of the populist German Left Party, the leadership was seen as flirting with a welfare chauvinistic, politically exclusionary turn in recent years by criticising immigration. Contrarily, further transnationalisation of left populists in support of cosmopolitan democratisation is possible, too: for instance, looser and less radically pan-European leftist platforms comprising the populists of France Insoumise and Spain’s Podemos were recently formed ahead of the 2019 EP elections (Mélenchon Reference Mélenchon2018).Footnote 7 Given the authoritarian potential of communitarian forms of populism for GC and the potentially democratising potential of transnationally inclusionary populism, these dynamics of discursive change remain crucial avenues for further research.

Second, the analysis also spurs the question whether ambiguous cases are currently stuck between conflicting views or, rather, deliberately choose to ignore a key political conflict in societies marked by transnational issues and institutions. It is not always clear whether this ambiguity is a beneficial strategy keeping together precarious electoral alliances, or whether it erodes their capacity of acting as a credible political force offering answers on important contemporary questions. As communitarian populists partly compete with the left in offering economically left-wing positions, the transnational political cleavage may become the site where progressive visions, populist or otherwise, are set apart from regressive ones which trade off others’ political rights for ‘community’ gain. Not decisively articulating alternative visions may normalise communitarian populist constructions of legitimate ethno-popular opposition to allegedly lofty and privileged cosmopolitan ideas, thereby devaluing international principles like human rights.