Introduction

Improving the mental health of adolescents aged 10–19 is a global priority. Estimates suggest that 13% of adolescents are living with a mental disorder, equating to around 166 million worldwide (UNICEF, 2021). Poor mental health in adolescence can impair physical health, socio-emotional development, and educational attainment, limiting opportunities to thrive in adulthood (Thapar et al., Reference Thapar, Collishaw, Pine and Thapar2012). Moreover, mental disorders are causally linked to suicide which is the fifth most prevalent cause of adolescent death (UNICEF, 2021).

Depression is a common mental disorder which accounts for 11% of total years lived with disability among adolescents aged 15–19 and 7% among adolescents aged 10–14 (Mokdad et al., Reference Mokdad, Forouzanfar, Daoud, Mokdad, El Bcheraoui, Moradi-Lakeh, Kyu, Barber, Wagner, Cercy, Kravitz, Coggeshall, Chew, O'Rourke, Steiner, Tuffaha, Charara, Al-Ghamdi, Adi, Afifi, Alahmadi, Albuhairan, Allen, Almazroa, Al-Nehmi, Alrayess, Arora, Azzopardi, Barroso, Basulaiman, Bhutta and Al2016). The burden is highest in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), yet the availability of mental health care in these settings is especially low (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana, Bolton, Chisholm, Collins, Cooper, Eaton, Herrman, Herzallah, Huang, Jordans, Kleinman, Medina-Mora, Morgan, Niaz, Omigbodun, Prince, Rahman, Saraceno, Sarkar, De Silva, Singh, Stein, Sunkel and Unützer2018). In an effort to overcome this treatment gap, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends evidence-based psychological interventions for treating depression in adolescents (World Health Organization, 2016). Some of these interventions were developed in high-income countries and exporting them to LMIC settings poses multiple challenges (Benish et al., Reference Benish, Quintana and Wampold2011; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Ibaraki, Huang, Marti and Stice2016; Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders, Purgato and Barbui2018). Mental health care in LMICs tends to be institutionalised and trained mental health personnel at the community level are scarce. Primary health care systems are often under-resourced and overburdened, with limited mental health care capacity. Cultural challenges relate to divergent local concepts of distress and community perceptions of the acceptability and utility of mental health diagnoses and care (Heim and Kohrt, Reference Heim and Kohrt2019, Sangraula et al., Reference Sangraula, Kohrt, Ghimire, Shrestha, Luitel, Van't Hof, Dawson and Jordans2021).

The past decade has seen a rise in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of psychological treatments adapted for LMICs, but the evidence base for treatments in children and adolescents is trailing that for adults. Recent meta-analyses demonstrated that effect sizes of psychological treatments are smaller in children than in adults (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Eckshtain, Ng, Corteselli, Noma, Quero and Weisz2020). An umbrella review of psychological interventions in humanitarian settings found adequate evidence to support treatments for children with conduct problems and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but not depression (Barbui et al., Reference Barbui, Purgato, Abdulmalik, Acarturk, Eaton, Gastaldon, Gureje, Hanlon, Jordans, Lund, Nosè, Ostuzzi, Papola, Tedeschi, Tol, Turrini, Patel and Thornicroft2020). Research that tests psychological interventions for children and adolescents with depression is needed to build the evidence base in LMICs.

Interpersonal therapy (IPT) is one such psychological intervention that was developed in the USA to treat depression among adults and has been successfully adapted for adolescents in LMIC settings (Mufson et al., Reference Mufson, Dorta, Wickramaratne, Nomura, Olfson and Weissman2004a, Reference Mufson, Gallagher, Dorta and Young2004b; Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Rosselló et al., Reference Rosselló, Bernal and Rivera-Medina2008; O'Shea et al., Reference O'Shea, Spence and Donovan2015). The therapeutic focus of IPT is on the interpersonal context of depression, codified into key interpersonal triggers of depressive episodes, the four ‘interpersonal problem areas’: grief, disputes, role transitions, and social isolation. The persons are helped therapeutically by understanding the connection between their depression and the problem areas associated with it, and by building skills to manage these problems more effectively. Meta-analyses suggest IPT reduces depressive symptoms in adolescents (d = −1.48) and may be more acceptable to them than other psychological therapies (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Hetrick, Cuijpers, Qin, Barth, Whittington, Cohen, Del Giovane, Liu, Michael, Zhang, Weisz and Xie2015; Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Sharpe and Schwannauer2019; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Teng, Zhang, Del Giovane, Furukawa, Weisz, Li, Cuijpers, Coghill, Xiang, Hetrick, Leucht, Qin, Barth, Ravindran, Yang, Curry, Fan, Silva, Cipriani and Xie2020).

Nepal is a lower middle-income country where psychological intervention for depression in adolescents is urgently needed. The earthquakes in 2015 compounded effects of a decade-long war on the stability and prosperity of Nepali society and the economy. Over 8000 people were killed, over 16 000 injured, and many more left homeless or displaced (Ministry of Home Affairs, 2015). Monsoon rains, flooding, and landslides continue to drive people from their homes. After the earthquakes, the prevalence of adolescent depression was 40% in some areas (Silwal et al., Reference Silwal, Dybdahl, Chudal, Sourander and Lien2018). Violence at home and in school, poverty, and parental migration are key risk factors for depression among Nepali adolescents. The COVID-19 pandemic and national lockdown pose further risks to their mental health (Orben et al., Reference Orben, Tomova and Blakemore2020; Kola et al., Reference Kola, Kohrt, Hanlon, Naslund, Sikander, Balaji, Benjet, Cheung, Eaton, Gonsalves, Hailemariam, Luitel, Machado, Misganaw, Omigbodun, Roberts, Salisbury, Shidhaye, Sunkel, Ugo, Van Rensburg, Gureje, Pathare, Saxena, Thornicroft and Patel2021). Existing mental health services are concentrated in urban centres and specialised services for children and adolescents are virtually non-existent (Luitel et al., Reference Luitel, Jordans, Adhikari, Upadhaya, Hanlon, Lund and Komproe2015).

In this study we aimed to evaluate the feasibility of IPT for depressed adolescents in Nepal. We chose IPT because it is potentially compatible with Nepali conceptualisations of identity and distress, can be delivered by non-specialist workers, and can be conducted in groups which is likely to be more cost-effective and culturally acceptable than one-to-one therapy (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Jordans, Regmi and Sharma2005; Rose-Clarke et al., Reference Rose-Clarke, Hassan, Bk, Magar, Devakumar, Np, Verdeli and Ba2021). We adapted IPT for delivery in schools based on adolescents' and parents' preferences, and evidence that school-based psychological interventions are effective, scalable, and sustainable (Michelson et al., Reference Michelson, Malik, Parikh, Weiss, Doyle, Bhat, Sahu, Chilhate, Mathur, Krishna, Sharma, Sudhir, King, Cuijpers, Chorpita, Fairburn and Patel2020, Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Sorgenfrei, Mulcahy, Davie, Friedrich and Mcbride2021).

Methods

We conducted a mixed-methods, uncontrolled pre-post evaluation to explore the feasibility of IPT and inform decisions to progress to an RCT. We use feasibility as an umbrella term that includes acceptability, utility, fidelity, outcome trends, and cost (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Lancaster, Campbell, Thabane, Hopewell, Coleman and Bond2016).

Setting

Four government secondary schools in Sindhupalchowk took part. Sindhupalchowk is a mountainous district on the Nepal–Tibet border. The population (c. 288 000) mainly lives in rural areas and agriculture is the main source of income (UN Women, 2016). Life expectancy is 62 years. Net enrolment rates for lower secondary and secondary level schools are 78 and 43% respectively (UN Women, 2016).

Intervention

We culturally and developmentally adapted the WHO group IPT intervention for delivery in schools in Nepal. Intervention components and adaptations made are detailed elsewhere (Rose-Clarke et al., Reference Rose-Clarke, Pradhan, Shrestha, Prakash, Magar, Luitel, Devakumar, Rafaeli, Clougherty, Kohrt, Jordans and Verdeli2020) and included: (i) replacing the term depression with heart-mind problems (manko samasya), which is a non-stigmatising Nepali term (Kohrt and Harper, Reference Kohrt and Harper2008); (ii) framing the intervention as life skills training to mitigate stigma towards participants; and (iii) including singing, dancing, and storytelling to help build relationships within groups and improve engagement. We included two pre-group sessions: the first with the adolescent at school to identify the most relevant IPT problem areas, help the adolescent link their depressive symptoms to the problem area, and gather information about their interpersonal relationships and history of depression; the second with the adolescent and their parent, ideally at home, to mobilise parental support and build rapport with the adolescent's family. Adolescents and parents initially provided consent to participate in the first pre-group session (adolescents took an information sheet and consent form home from school for signing). The IPT facilitator collected consent for the group sessions in the second pre-group session. Adolescents were then invited to 12 weekly group sessions. Groups were gender specific. The initial session focused on encouraging adolescents to review and share their problems, and instilling hope for recovery. In middle sessions (2–11) adolescents practiced new interpersonal skills and offered and received support to resolve their problems. In the last session, they reviewed and celebrated their progress, and made plans to tackle future problems.

In each session adolescents reviewed their depressive symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire – Adolescent Version (PHQ-A) (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Harris, Spitzer and Williams2002). This was an integral part of IPT to help adolescents link changes in their symptoms to events in their daily lives. It also enabled facilitators to identify deterioration and suicidality. We developed a standard operating procedure to manage adolescents reporting suicidal thoughts, which included risk assessment, consultation with an IPT supervisor, communication with parents, and one-to-one intervention with a psychosocial counsellor.

We initially recruited and trained nine IPT facilitators. We recruited staff nurses because of a national policy to appoint nurses in secondary schools across the country. However, most nurses in Nepal are female and in the formative research adolescents said they preferred facilitators of the same gender, so we also recruited community lay facilitators. Facilitator training involved: (i) a 10-day in-person training to build basic psychosocial skills, including interpersonal communication, listening, non-verbal communication, and group management skills; (ii) a didactic 10-day workshop using the IPT manual; (iii) an IPT knowledge test; and (iv) practice using IPT skills with small groups of adolescents. Supervisors assessed facilitators' competency using the ENhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic factors (ENACT) rating scale and the Working with children – Assessment of Competencies Tool (WeACT) (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Jordans, Rai, Shrestha, Luitel, Ramaiya, Singla and Patel2015; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Coetzee, Steen, Koppenol-Gonzalez, Galayini, Diab, Aisha and Kohrt2021). Supervisors also used standardised lists to rate IPT-specific tasks carried out by facilitators in the sessions. From the nine facilitators we selected six (two nurses and four lay workers) based on their competency and availability, ensuring an equal number of male and female facilitators.

Facilitators worked in pairs. Six out of eight groups were facilitated by a nurse-lay worker pair. Group sessions took place between December 2019 and April 2020, in a classroom, library, or outside the school if space was unavailable. We ran eight groups (four female, four male) of five to nine adolescents. Facilitators were supervised by Nepali IPT supervisors (IP and PS). Supervisors were trained and supervised themselves by IPT master trainers (HV, KC, and AKR).

Participants

IPT participants were 62 adolescents (32 boys and 30 girls) with depression and functional impairment. We used a two-stage process to recruit adolescents from four mixed gender, government secondary schools. First, we used the Community Informant Detection Tool (CIDT) adapted for adolescents to identify those with depression (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Kohrt, Luitel, Komproe and Lund2015). The tool comprised of a vignette and illustrations of adolescent depression. In schools, researchers discussed the vignette with adolescents and asked those who felt they were experiencing similar symptoms to complete the CIDT. This involved the adolescent matching symptoms presented in the vignette with their own symptoms and evaluating the extent to which symptoms compromised daily functioning. Second, we invited probable cases for further screening. Inclusion criteria were: adolescents aged 13–19; score of 14 or more on the Depression Self Rating Scale (DSRS); and score of four or more on a measure of functional impairment (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Komproe, Tol, Kohrt, Luitel, Macy and De Jong2010; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Jordans, Tol, Luitel, Maharjan and Upadhaya2011). Exclusion criteria were current suicidal ideation with a current plan or a plan in the last 3 months; suicide attempt in the past 3 months; alcohol or substance abuse; and inability to participate in interviews due to severe cognitive or physical impairment, including severe mental disorders such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

Quantitative measures of feasibility

We calculated the participation rate as the number of adolescents who participated in group sessions as a percentage of all those eligible. We calculated the mean percentage attendance at group sessions (attendance at pre-group sessions was a prerequisite for receiving the intervention). IPT supervisors observed 27 of 90 group sessions. For each group, they aimed to observe at least one session from initial, middle, and termination phases. During these in-person observations supervisors assessed intervention fidelity using standardised lists to rate how well facilitators carried out key components of the session. Lists were adapted from tools in the WHO IPT manual (World Health Organization and Columbia University, 2016). Supervisors rated each session component as ‘superior’, ‘satisfactory’, ‘needs improvement’, ‘failed to attempt’, ‘not applicable’, or ‘could not assess’. Fidelity was calculated as the percentage of components rated superior or satisfactory. We used the follow-up rate and percentage of missing data to assess the feasibility of study procedures.

Outcome measurements

We assessed adolescent mental health outcomes at three time points: immediately before the first individual session (baseline); within 2 weeks of the 12th group session (post-treatment); and 8–10 weeks after the 12th group session (follow-up). Primary outcomes were depression measured with the DSRS, and functional impairment measured with a locally developed tool. The DSRS is an 18-item screening tool for children and adolescents that has been used in various cultural contexts (Ivarsson et al., Reference Ivarsson, Lidberg and Gillberg1994; Denda et al., Reference Denda, Kako, Kitagawa and Koyama2006; Panter-Brick et al., Reference Panter-Brick, Eggerman, Gonzalez and Safdar2009). In the adapted Nepali version items are presented as questions, for example ‘Are you able to sleep well?’, ‘Do you feel like eating when you see food?’ and response options are ‘never’, ‘sometimes’, or ‘mostly’ (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Jordans, Tol, Luitel, Maharjan and Upadhaya2011). Responses were summed to give a total score out of 36 with higher scores indicating more severe depression. The functional impairment tool is a 10-item scale to assess adolescents' ability to participate in the past 2 weeks in locally relevant daily activities including working in the fields, doing house chores, and spending time with friends (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Komproe, Tol, Kohrt, Luitel, Macy and De Jong2010). Items are in question format and responses are ‘none of the time’, ‘a little of the time’, ‘some of the time’, and ‘all the time’. Scores range from 0 to 30 with higher scores indicating more impairment. The tool was originally developed for a study in southwestern Nepal using methods outlined by Bolton and Tang (Reference Bolton and Tang2002). We adapted it for Sindhupalchowk using free listing to identify tasks that are important to adolescents in this setting. Secondary outcomes were anxiety, PTSD, and disruptive behaviour, measured with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI, 21 items); Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS) (17 items); and Disruptive Behaviour International Scale – Nepal (DBIS-N, 24 items) (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Kunz, Koirala, Sharma and Nepal2003; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Komproe, Tol, Kohrt, Luitel, Macy and De Jong2010; Burkey et al., Reference Burkey, Ghimire, Adhikari, Kohrt, Jordans, Haroz and Wissow2016; Burkey et al., Reference Burkey, Adhikari, Ghimire, Kohrt, Wissow, Luitel, Haroz and Jordans2018). Tools were translated into Nepali and previously validated in Nepal.

We wanted to use different tools to assess the primary outcome and in-session depression assessments because we anticipated adolescents would become very familiar with the latter, increasing the risk of social desirability bias and a testing effect. We also wanted a shorter tool in the sessions to mitigate interview fatigue. We therefore used the Patient Health Questionnaire – Adolescent Version (PHQ-A, 9 items) to monitor session-by-session change (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Harris, Spitzer and Williams2002). The PHQ-A is a modification of the Patient Health Questionnaire which was validated in Nepal among adults (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Luitel, Acharya and Jordans2016). Validation of the PHQ-A among adolescents in Nepal is underway.

Cost analysis

We did an activity-based cost analysis of the design and implementation of IPT from the provider perspective. Costs from monthly project accounts were entered in an Excel tool, divided into start-up or implementation costs, and allocated to different cost centres (capital, staff, and materials) and intervention activities (e.g. adaptation, training, facilitation, etc.). Interviews with project staff before implementation and at follow-up informed how they divided their time across activities and thus how to allocate their salaries. The total cost of the intervention was annualised then divided by the number of participants in a year to estimate a unit cost per IPT participant. We calculated a unit cost per participant based on four assumptions. First, the IPT manual, training materials, and training of trainers were treated as single capital items with a useful life of 7 years (Greco et al., Reference Greco, Knight, Ssekadde, Namy, Naker and Devries2018). Like other capital costs, these were annualised over their useful life using a discount rate of 8.00% (Nepal Government Bond yield in 2020) (Greco et al., Reference Greco, Knight, Ssekadde, Namy, Naker and Devries2018; International Monetary Fund, 2020). Second, each facilitator pair can run three groups of 10 adolescents simultaneously, and a total of 36 groups per year (360 adolescents). Third, facilitators need annual refresher training and supervisors need sporadic support from master trainers. Fourth, when estimating unit costs for 360 participants, we assumed a linear increase of the recurrent costs incurred to provide the intervention to 62 participants. This is because sessions would run in the same place and additional participants would come from the same area with similar accessibility. All costs were inflated to 2020 and converted from Nepali rupees to international and US dollars using World Bank data on consumer price index and exchange rates (World Bank, 2020). Last, univariate sensitivity analyses were carried out to test the key assumption and cost driver relating to the annual number of participants that facilitators could serve at capacity.

Quantitative data collection and analysis

We based the sample size on the minimum number of groups needed to pilot various facilitator combinations (e.g. both female facilitators, both male, one female, and one male). Facilitators recorded attendance and adolescents completed the PHQ-A at each session. We collected quantitative data on mental health, costs, and sociodemographic characteristics through interviews with adolescents at baseline, post-treatment, and follow-up. Researchers conducted the interviews using tablets programmed with ODK data collection software.

Mental health outcomes were analysed as continuous outcomes. We conducted descriptive analyses comparing outcomes at baseline to post-treatment, and baseline to follow-up and calculated a measure of effect size (Cohen's d). We repeated these analyses excluding three participants referred to the psychosocial counsellor to see how it affected outcomes. We conducted sub-group analyses to see if changes in outcomes were concentrated by gender, caste/ethnic group, income level (low v. not low, with low defined as sufficient family income for no more than 6 months), family type (nuclear or extended), baseline mental health comorbidities, IPT group, and school.

Qualitative evaluation of feasibility

Researchers conducted semi-structured interviews with 16 adolescents and all six facilitators. We sampled female and male adolescents with low (less than four group sessions), medium (4–7), and high attendance (8–12) at group sessions, across age and caste/ethnic groups. Topic guides included questions on positive and negative aspects of IPT and adverse events. Interviews were in Nepali, audio-recorded, transcribed, and translated into English. Data were analysed using the Framework approach which involved developing a coding framework used to open-code interview transcripts, and mapping summaries into a matrix (Excel spreadsheet) (Gale et al., Reference Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid and Redwood2013).

Impact of COVID-19 on implementation and data collection

Face-to-face research in Nepal was banned in March 2020 so we had to conduct 25/62 post-treatment surveys and all follow-up surveys by phone. Using regression analysis with interactions, we tested whether the change in mental health outcomes between post-treatment and follow-up differed by whether the post-treatment interview was conducted on the phone or in person. We found no statistically significant differences in any outcome between individuals who had their post-treatment interview conducted in person v. over the phone.

Supervisors were unable to complete all planned observations of sessions and supervisions were done by phone. We conducted qualitative interviews with facilitators using phone/video conferencing. Qualitative interviews with adolescents were delayed until after the lockdown in June 2020. Due to COVID-related restrictions some IPT groups did not receive 12 in-person group sessions: one male group received 11 group sessions; one male group received 9/12 in-person group sessions with the final session conducted individually by phone; and one male group received 10 in-person group sessions plus a final session by phone.

Ethics

The Nepal Health Research Council (637/2018) and King's College London Research Ethics Committee (RESCM-18/19–8427) approved the research.

Results

Table 1 presents adolescent baseline characteristics. More than two-thirds were from low-income households defined as those having sufficient income for no more than 6 months. Mean scores for depression, anxiety, PTSD, and disruptive behaviour were similar across genders. Baseline characteristics by school are reported as online Supplementary materials (Appendix A). The intra-class correlation coefficient for DSRS at baseline across schools was 0.07.

Table 1. Baseline descriptive sample characteristics, overall and by gender

s.d., standard deviation.

a Low income = family income sufficient for no more than 6 months.

Feasibility of IPT and study procedures

The participation rate was 93.9% (62/66) and mean attendance was 82.3% [standard deviation (s.d.) 18.9, n = 62]. Online Supplementary Appendix B is a participant flowchart. Supervisors rated 95.3% of IPT-specific tasks as superior or satisfactory across 27/90 sessions observed. All adolescents were followed up at post-treatment and follow-up. There were no missing data.

Outcome trends

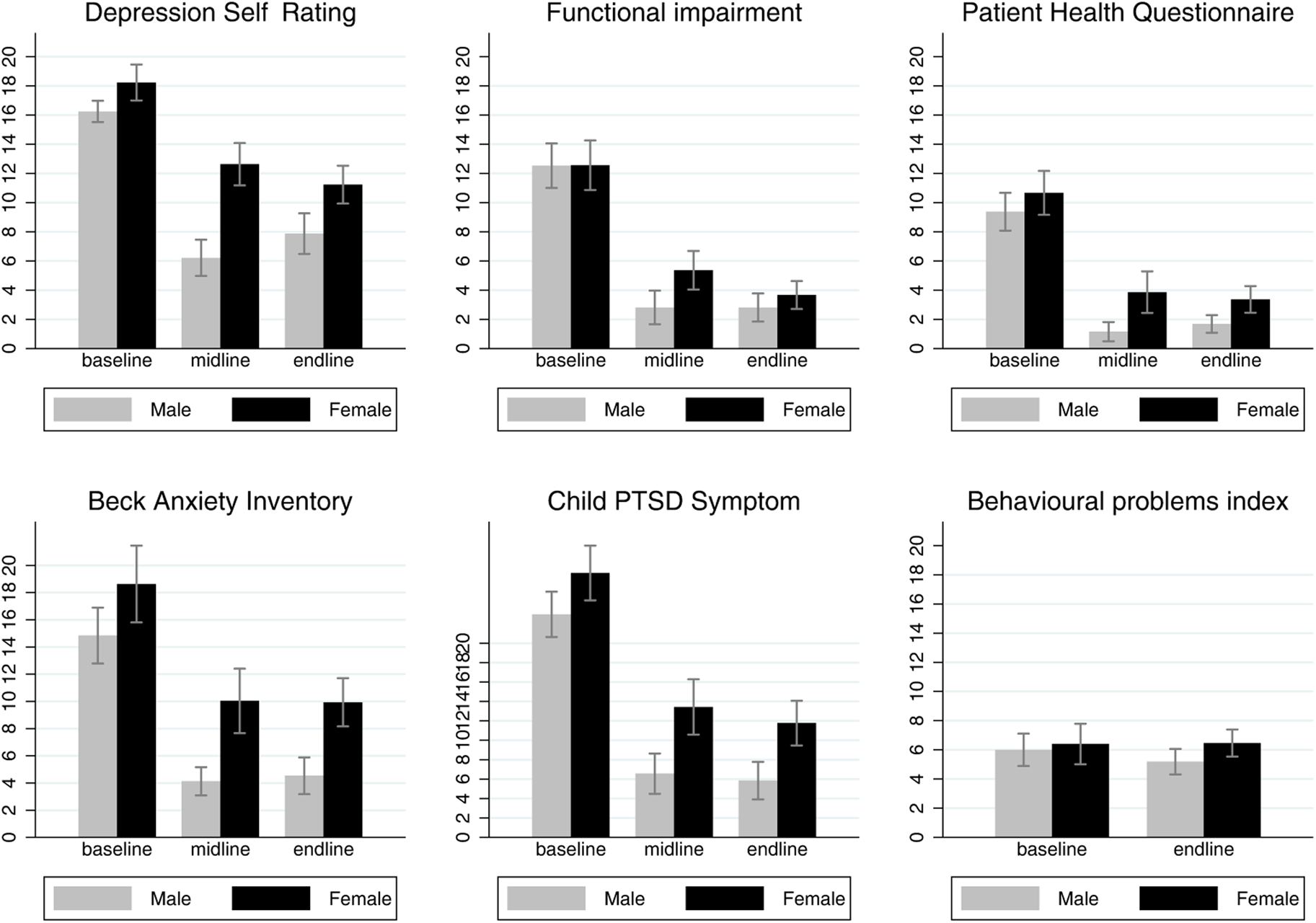

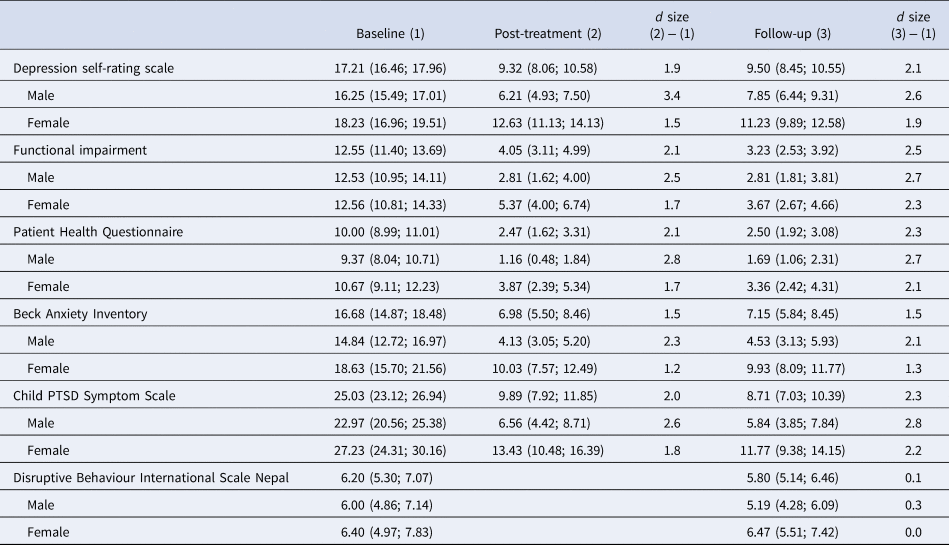

Table 2 and Fig. 1 show that all outcomes except for disruptive behaviour improved between baseline and post-treatment, and between baseline and follow-up. Facilitators referred three adolescents at high risk of suicide to a psychosocial counsellor. Results remained the same after excluding these participants from the analyses. Most improvements happened between baseline and post-treatment. Cohen's d ranged from 1.5 for anxiety to 2.5 for functional impairment, indicating large effect sizes. Across outcomes, fidelity to the IPT manual and effect size were not correlated.

Fig. 1. Outcome means and 95% confidence intervals by gender at baseline, post-treatment, and follow-up time points.

Table 2. Results overall, and by gender with within-group effect sizes (Cohen's d)

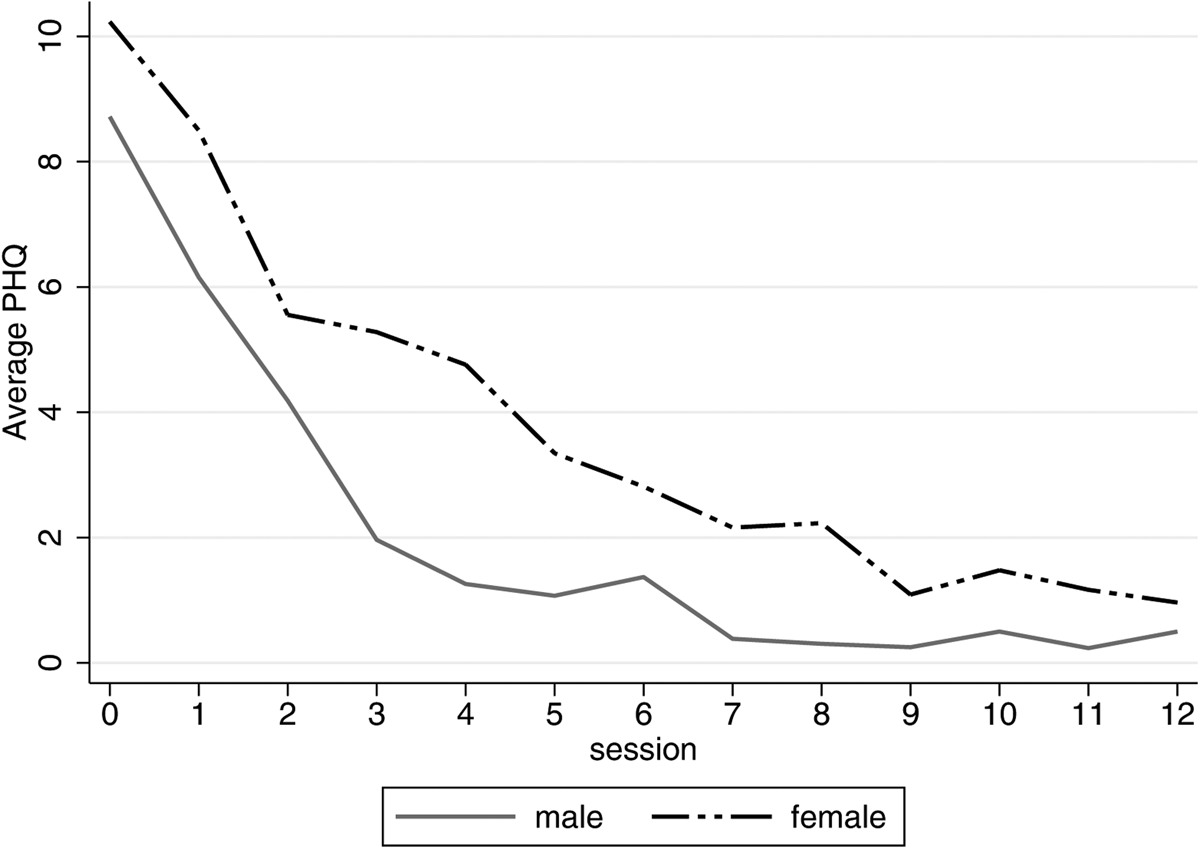

The rate of improvement was highest in the first three sessions and boys improved faster than girls (Fig. 2). Males and females had similar levels of depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms at baseline, both groups improved up to follow-up, but males improved more than females across these outcomes (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Fig. 2. Session by session depressive symptoms by gender.

Improvements in mental health did not differ by caste/ethnic group, income level, or family type. Graphs of outcomes by age (13–14 v. 15–19 years) and number of comorbidities are given in online Supplementary Appendices C and D. Adolescents in schools 3 and 4 improved more than those in schools 1 and 2 for all outcomes except for disruptive behaviour. Because schools 3 and 4 ran male-only groups, it was unclear if differences in mental health reflected differences in improvement due to gender or the school environment. All eight IPT groups improved from baseline to follow-up across depression, anxiety, and PTSD outcomes with some exceptions: depression measured using the DSRS did not improve in one female group, and anxiety did not improve in two female groups.

Cost analysis

The total intervention cost was NPR 6 682 849 (Int'l $199 310; US $57 457) between September 2018 and 2020, with an annualised cost of NPR 3 341 424 (Int'l $99 655; US $27 728; online Supplementary Appendix E). The unit cost was NPR 53 894 (Int'l $1607; US $447.2) per participant (n = 62). If facilitators were operating at capacity (n = 360) the annualised total cost is NPR 4 055 368 (Int'l $120 947; US $34 867) and unit cost is NPR 11 265 (Int'l $336.0; US $96.9). The main driver of unit cost is the number of groups a pair of facilitators can run at capacity. Assuming they run two groups simultaneously (n = 240) the unit cost is NPR 16 470 (Int'l $491.2; US $141.6); if they run four groups (n = 480) the unit cost is NPR 8663 (Int'l $258.4; US $74.5).

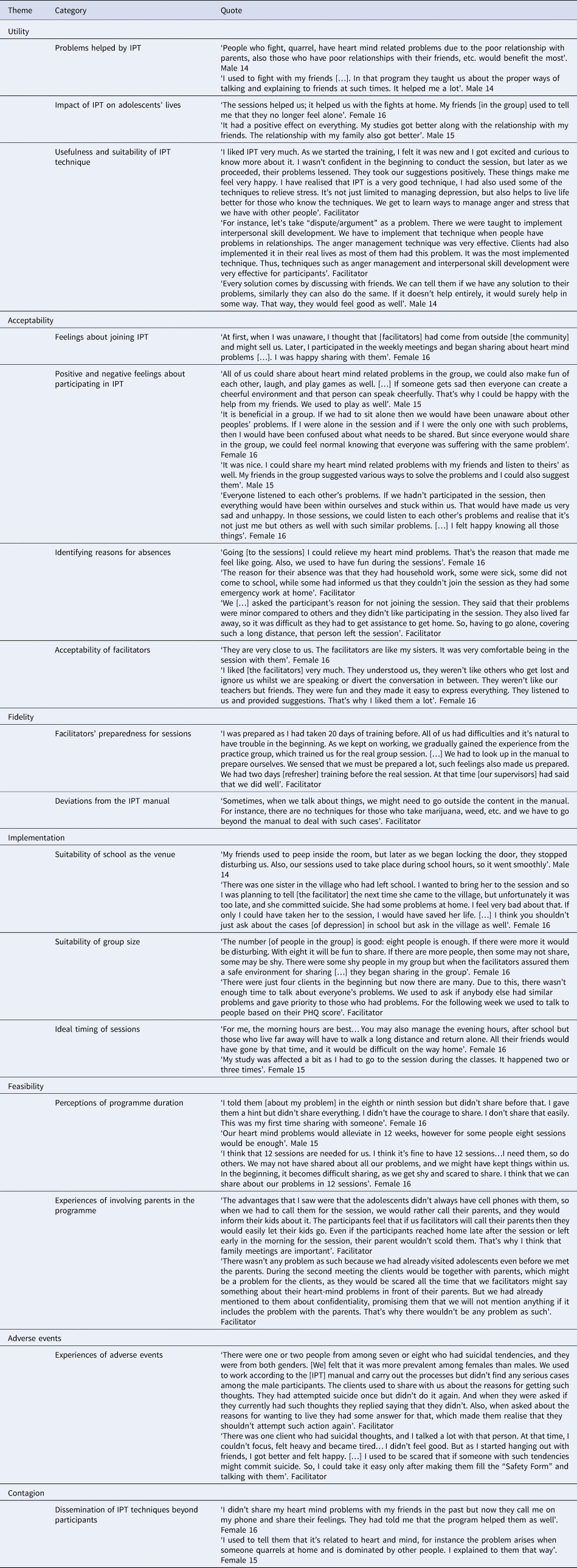

Perceptions of acceptability, feasibility, and utility

Qualitative interviews captured adolescents' mixed feelings about being recruited to IPT (Table 3). Nine felt happy to join. One girl initially worried that the programme was a front for human trafficking. Others, especially girls, were worried they would damage their ‘family prestige’ (pariwarko Ijjat janu) by sharing about their family in a group. However, having completed the programme all adolescents emphasised the value of sharing and the advice and support they received from group members.

Table 3. Findings from qualitative interview with adolescents and facilitators

Adolescents thought IPT sessions were ‘fun’ and enjoyed the singing and games. They were unanimously positive about facilitators whom they described as like ‘friends’ or siblings who understood their problems, listened, and created a comfortable group environment. Adolescents and facilitators thought the most useful skills were in decision-making, communicating, role-play, anger management, and relaxation. Facilitators described how they competently managed adolescents with suicidal ideation, but how it made them feel ‘heavy’ and anxious. Adolescents said that even though the programme had finished, they continued to use and share the skills they learned to help themselves and their friends.

School was perceived to be a suitable and convenient location for IPT sessions though some adolescents reported being disturbed by noise and concerns about privacy. They suggested sessions should be in a room with a lockable door and scheduled for the early morning or lunchtime to avoid having to miss class or return home late. A female participant highlighted the need to include out of school adolescents in groups:

‘There was one sister in the village who had left school. I wanted to bring her to the session and so I was planning to tell [the facilitator] but unfortunately it was too late and she committed suicide. I feel very bad about that. If only I could have taken her to the session I would have saved her life. […] I think you shouldn't just ask about the cases [of depression] in school but ask in the village as well’. Female 16

Adolescents and facilitators agreed that IPT participants with more heart-mind problems required more sessions than those with fewer problems. All facilitators and some adolescents recommended reducing the number of sessions. Facilitators thought most participants' problems were resolved after session eight and that they were less likely to attend subsequent sessions. Facilitators identified illness, exams, school/home/paid work, festivals, and sporting events as reasons for absence.

Most parents supported their child's participation and reminded them to attend. Facilitators stressed the importance of initially meeting parents to build rapport and learn more about the adolescent but found it difficult to travel to remote villages and find a mutually convenient time.

Fourteen adolescents said they had not experienced stigma related to participating in IPT. One said that friends had teased him, and another described how a teacher shouted at him for missing class. In one school facilitators asked the principal to intervene because a teacher referred to a participant as ‘psycho’ and IPT groups as ‘psycho groups’. Adolescents and facilitators recommended school-level psychoeducation and programme orientation to explain that IPT can help adolescents solve problems and improve their studies.

Discussion

The results of the study support progression to an RCT to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of IPT for adolescents with depression in Nepal. Adolescents found IPT acceptable, evidenced by high recruitment and attendance rates and qualitative data suggesting they thought groups were useful and fun. Adolescents perceived that IPT reduced their heart-mind problems and outcome trends suggest improvements in depression, functioning, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms between baseline and follow-up. Training and supervision of nurses and lay workers to deliver IPT was feasible, evidenced by high levels of fidelity to the manual. The recruitment process identified sufficient adolescents with depression, although recruitment of more out of school adolescents is needed. Ethics and safety procedures ensured high risk suicidal adolescents were identified and treated. Data collection procedures were feasible evidenced by no missing data. A cluster RCT which randomises schools rather than individuals to trial arms could help to minimise any contamination related to adolescents sharing IPT skills with their peers.

There are several strengths of our study including the mixed methods approach used to test a culturally adapted psychological treatment that is potentially scalable through the education system. The lack of a control arm means we cannot infer causality and attribute adolescents' improvements in mental health to IPT. Although outcome assessments were conducted by research assistants, not IPT facilitators, we cannot exclude the possibility of social desirability bias in surveys and qualitative interviews. COVID-19 lockdown measures in 2020 halted face-to-face IPT sessions and data collection but it was still possible to conduct sessions and assessments with adolescents by phone. Moreover, despite the unprecedented and potentially distressing circumstances during lockdown, we observed maintained improvements in participants' mental health.

Our study is relevant beyond Nepal and contributes to a growing body of global research showing the feasibility of psychological treatments delivered by people who are not specialists in mental health (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, King and Prost2013; Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders, Purgato and Barbui2018; van Ginneken et al., Reference Van Ginneken, Chin, Lim, Ussif, Singh, Shahmalak, Purgato, Rojas-García, Uphoff, Mcmullen, Foss, Thapa Pachya, Rashidian, Borghesani, Henschke, Chong and Lewin2021). Nurses and lay workers delivered IPT in pairs. This facilitator model is advantageous because the intervention could be scaled up through the education system and network of school-nurses. Recruitment of male lay workers to support the mainly female workforce of school nurses ensures the intervention is acceptable to adolescents who prefer a facilitator of the same gender. We did not directly compare therapeutic competency between nurses and lay workers because of the small number of facilitators in the study. However, this analysis could help to optimise facilitator training and supervision and should be part of a future fully powered RCT.

We delivered IPT through secondary schools. Adults and adolescents who participated in our formative work said they did not trust organisations from outside the community so we should deliver the intervention in schools (Rose-Clarke et al., Reference Rose-Clarke, Pradhan, Shrestha, Prakash, Magar, Luitel, Devakumar, Rafaeli, Clougherty, Kohrt, Jordans and Verdeli2020). The high rate of attendance at group sessions suggests school is a convenient and accessible location for adolescents. This contrasts with trials of IPT in healthcare settings reporting low uptake (51%) and high dropout rates (28%) in South Africa and Kenya, respectively (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Hanass Hancock, Bhana and Govender2014; Meffert et al., Reference Meffert, Neylan, Mcculloch, Blum, Cohen, Bukusi, Verdeli, Markowitz, Kahn, Bukusi, Thirumurthy, Rota, Rota, Oketch, Opiyo and Ongeri2021). Evidence for school-based mental health interventions in LMICs is only just emerging but results are promising (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Patel, Thomas and Tol2014; Michelson et al., Reference Michelson, Malik, Parikh, Weiss, Doyle, Bhat, Sahu, Chilhate, Mathur, Krishna, Sharma, Sudhir, King, Cuijpers, Chorpita, Fairburn and Patel2020; Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Gericke, Coetzee, Stallard, Human and Loades2021). Schools vary greatly in terms of environment, resources, and their suitability as a venue for mental health care. In Nepal, corporal punishment is common, and schools may not have a quiet, private room for group sessions. Adolescents participating in a mental health intervention may experience stigma and discrimination from peers and teachers (Gronholm et al., Reference Gronholm, Nye and Michelson2018). Participant confidentiality and safety are paramount so assessment of a school's suitability and readiness, and parallel anti-stigma and psychoeducation activities must be pre-requisites for school-based psychological intervention in Nepal and beyond.

For all the potential advantages of school-based programmes (accessibility, scalability, and efficacy), they usually exclude adolescents who are not in education. In Nepal this is around 12% of adolescents who tend to be from poorer households, are at greater risk of early marriage and child labour and are likely to have more mental health problems than school-going adolescents (Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Jeffery, Odero, Rose-Clarke and Devakumar2022). Although we did not explicitly exclude out of school adolescents, we did not proactively search for them. Earlier formative research suggests that out of school adolescents would consider attending school-based programmes alongside school-going adolescents. One possible solution could therefore be a more inclusive community-based recruitment strategy. This could involve training adolescents, community leaders, and health workers to use the Community Informant Detection Tool to find and refer out-of-school adolescents (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Kohrt, Luitel, Komproe and Lund2015). Elsewhere, IPT sessions have been held in community healthcare settings which could be feasible in parallel or combined with sessions in schools (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar, Chatterjee, De Silva, Bhat, Araya, King, Simon, Verdeli and Kirkwood2010; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana and Baillie2012).

The main aim of our study was to assess the feasibility and acceptability of IPT, rather than its effects. We report large effect sizes for mental health outcomes but these are likely inflated due to the pre-post study design without a control group and clustering at the school level which, with only four schools, we could not account for in the analysis (Bryan and Jenkins, Reference Bryan and Jenkins2015). More modest effects have been reported in RCTs of adolescent IPT (Mufson et al., Reference Mufson, Weissman, Moreau and Garfinkel1999; Mufson et al., Reference Mufson, Gallagher, Dorta and Young2004b; Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, Bass, Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, Clougherty, Neugebauer, Murray and Verdeli2007; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Jou, Ko, Huang and Yen2009). Our strategy of selecting the six most competent facilitators to deliver the intervention from the nine we trained likely facilitated the study outcomes and may not be feasible in a larger community-based programme. However, there are several reasons to suggest IPT may be effective in rural Nepal. First, IPT was the result of an evidence-based cultural adaptation of IPT in this setting (Rose-Clarke et al., Reference Rose-Clarke, Pradhan, Shrestha, Prakash, Magar, Luitel, Devakumar, Rafaeli, Clougherty, Kohrt, Jordans and Verdeli2020). Evidence from meta-analyses suggests therapies that have been culturally adapted may be more effective than those that have not (Benish et al., Reference Benish, Quintana and Wampold2011; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Ibaraki, Huang, Marti and Stice2016). Second, the group-based delivery of IPT facilitated locally relevant reciprocal support, empathy, and compassion, which participants valued highly (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Ottman, Panter-Brick, Konner and Patel2020). Third, experiences of physical and sexual abuse are prevalent among adolescents in Nepal [Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP), 2012]. Research suggests IPT may be particularly helpful for those with a history of maltreatment and/or trauma (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Newnham, Brennan, Verdeli, Borisova, Neugebauer, Bass and Bolton2012; Toth et al., Reference Toth, Handley, Manly, Sturm, Adams, Demeusy and Cicchetti2020). Last, Gunlicks-Stoessel et al. (Reference Gunlicks-Stoessel, Mufson, Jekal and Turner2010) found greater benefits of IPT among adolescents reporting high levels of conflict with their mother or peers (Gunlicks-Stoessel et al., Reference Gunlicks-Stoessel, Mufson, Jekal and Turner2010). Our qualitative data suggest many IPT participants experienced such difficulties and found communication analysis and anger management techniques particularly useful (Rose-Clarke et al., Reference Rose-Clarke, Hassan, Bk, Magar, Devakumar, Np, Verdeli and Ba2021). Whether the lack of correlation between fidelity to IPT and mental health outcomes is due to a ceiling effect or because adolescents mainly benefitted from the supportive group environment rather than the IPT content should be explored through an RCT.

We observed a greater improvement in depression among male than female participants which warrants further investigation in an RCT powered to detect gender differences. We aimed to recruit an equal number of male and female participants, but it was harder to find males with a sufficiently high DSRS score. This is likely because the prevalence of depression is lower among males, with the gender difference peaking in adolescence (odds ratio 3.02 between the ages of 13 and 15) (Hyde and Mezulis, Reference Hyde and Mezulis2020). Whether this gender difference is due to boys under-reporting depression because it is perceived to be unmasculine, or because distress in boys manifests more in externalising symptoms that are not captured by the DSRS remains unclear (Chaplin and Aldao, Reference Chaplin and Aldao2013; Hyde and Mezulis, Reference Hyde and Mezulis2020; Rice et al., Reference Rice, Oliffe, Seidler, Borschmann, Pirkis, Reavley and Patton2021).

Qualitative data suggest some adolescents and facilitators preferred fewer than 12 group sessions. This is supported by data showing that the rate of reduction in depressive symptoms was highest in the first three sessions and symptoms stabilised around the ninth group session. IPT was originally designed to be delivered over 12–16 sessions although it has been delivered in eight group sessions (Markowitz and Weissman, Reference Markowitz and Weissman2004; Swartz et al., Reference Swartz, Grote and Graham2014; World Health Organization and Columbia University, 2016). Alternative intervention models with fewer sessions and/or additional sessions for adolescents with persistent symptoms could be more acceptable and cost-effective. However, reducing the number of sessions reduces time for participants to consolidate IPT skills and techniques, which could reduce effect sizes and any longer-term treatment benefits. Moreover, in a two-stage model, adolescents requiring additional sessions may feel a sense of failure and lose hope of recovery. Research is therefore needed to explore IPT treatment duration as a potential effect modifier.

Taken at face value, unit costs for IPT in Nepal appear high, but our estimates are in line with those reported in a cluster-randomised trial of a group psychotherapy intervention for adults living with HIV with mild to moderate depression in rural Uganda (Nakimuli-Mpungu et al., Reference Nakimuli-Mpungu, Musisi, Wamala, Okello, Ndyanabangi, Birungi, Nanfuka, Etukoit, Mayora, Ssengooba, Mojtabai, Nachega, Harari and Mills2020). This intervention reduced depression and was highly cost-effective: the study estimated that costs would have to increase by 1000% before the intervention stopped being cost-effective. While it is challenging to predict costs at scale, this evidence suggests that IPT in Nepal could be cost-effective. Moreover, additional adjustments such as reducing the number of group sessions would reduce costs further.

Conclusion

A culturally adapted version of group IPT for adolescents delivered through schools in Nepal is feasible and acceptable. Our results support progression to an RCT to assess the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of IPT in this setting. Research is needed to develop alternative recruitment strategies for out of school adolescents, and to explore how treatment duration and social factors could modify IPT's effects to optimise intervention delivery and impact.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.46.

Acknowledgements

We thank the IPT facilitators and psychosocial counsellor for their contributions to the study.

Financial support

The work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research, and the Department for International Development (grant reference: MR/R020434/1).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation.