The term ‘Westminster model’ appears frequently in both the academic and practitioner literatures and will be familiar to many specialists in comparative politics, public administration and law. But what precisely does it mean, and is there consistency in its application? If put under the microscope, can any clear meaning actually be discerned? This article suggests that while ostensibly serving as a ‘model’ in the comparative literature, the term instead risks inducing muddle and unclear thinking.

Following Giovanni Sartori's (Reference Sartori, Collier and Gerring2009 [1984]) advice for ‘reconstructing’ a social science term whose meaning may be unclear, our article analyses uses of the term ‘Westminster model’ and its equivalents in the academic literature since 1999. We find that, while the term occurs frequently in comparative texts, authors’ interpretations of it are often unclear. Definitions are often absent, and, where present, they are frequently partial, divergent and sometimes even mutually contradictory. If a dominant interpretation exists, this is probably of a majoritarian parliamentary system – but such use is far from universal. It would be far better, if focusing on such systems, to state this explicitly. Too frequently scholars’ use of the term implies that empirical findings in single country or small-n studies have broader scope – which risks feeding flawed inferences and encouraging false generalization. In order to avoid this, and to bring greater clarity to debates, we propose that the ‘Westminster model’ should now be retired from comparative politics – and more precise terms, based on authors’ specific variables of interest, be put in its place.

The article proceeds as follows. First, we summarize the roots and general uses of the term ‘Westminster model’, which began as a descriptor in British politics, but developed over time to take on a more widely comparative use. We then review the literature on concept formation in political science, to consider the reasonable expectations for a useful political science term. Next, we briefly outline our methods. The substantive part of the article is then structured around three key questions. First, to what extent do authors define the Westminster model at all? Second, where it is defined, what are its suggested meanings and how much consistency exists? Third, having determined (as far as is possible) what the Westminster model is thought to mean, where is it considered to apply? We find that the countries commonly cited in the literature have relatively few key attributes in common, while sharing some important attributes with countries not normally associated with the model. Finally, we conclude, suggesting that the Westminster model fails the test for a classical political science concept, as well as the relatively weak requirements for a ‘family resemblance’ concept. It hence risks creating more confusion than illumination.

Origins of the Westminster model

The term ‘Westminster model’ is linked by various authors to Walter Bagehot's (Reference Bagehot2001 [Reference Bagehot1867]) exposition of the ‘English’ constitution (e.g. Rhodes et al. Reference Rhodes, Wanna and Weller2009). It did not actually appear in his text, but served – at least initially – as a convenient label for the system that he described. Subsequently it came increasingly to be used in a comparative context to describe countries influenced by the British system. It is now often deployed by comparativists to imply that there is a set of ‘Westminster model countries’ (e.g. Pinto-Duschinsky Reference Pinto-Duschinsky1999), ‘Westminster democracies’ (e.g. Brenton Reference Brenton2014; Grube Reference Grube2011; Kaiser Reference Kaiser2008), countries adhering to a ‘Westminster system’ (e.g. Eggers and Spirling Reference Eggers and Spirling2016; Estevez-Abe Reference Estevez-Abe2006) or indeed members of a ‘Westminster family’ (e.g. Eichbaum and Shaw Reference Eichbaum and Shaw2007: 613; Mulgan Reference Mulgan2008: 457; Paun Reference Paun2011: 452).

Yet a superficial reading of recent comparative literature suggests at least some confusion about what the term actually means. The Oxford English Dictionary offers little clue: the term ‘Westminster model’ appears only once, within the more generic entry for ‘Westminster’, citing a classic text by SA De Smith (Reference De Smith1961) on ‘Westminster's export models’. This is not necessarily its earliest use, but a search of Google Books since the publication of Bagehot's text shows that references grew sharply in the early 1960s (Figure 1). De Smith (Reference De Smith1961: 3) himself took care to point out that ‘[t]he Westminster model will never be a legal term of art, and the political scientist may wish to handle it circumspectly’. But this clearly did little to discourage its subsequent popularity. Another classic text, JP Mackintosh's The Government and Politics of Britain, whose first edition was published in 1970, used the ‘Westminster model’ as a framing device. For Mackintosh (Reference Mackintosh1970: 28) it described ‘the idealised version of British government in the 1880–1914 period’, but he suggested that even then it had been an imperfect descriptor, while subsequent changes meant it had developed significant ability to ‘mislead’. Mackintosh, however, noted that the ‘model’ had been exported. His own writing may have inadvertently contributed to its increased comparative use.

Figure 1. Occurrence of the Term ‘Westminster Model’ in English-Language Texts Published 1867–2008 and Captured on Google Books

Source: Google Books Ngram Viewer (http://books.google.com/ngrams), generated 11 February 2019.

Note: The graph shows the occurrence of the term as a proportion of all two-word phrases in texts captured by Google Books from each given year (see https://books.google.com/ngrams/info). Note this is a relative, not an actual measure: as the number of books published has also risen sharply, the growth in actual incidence of the term would be far steeper.

More recently, the notion of the Westminster model was boosted through the attention of comparativist Arend Lijphart. Lijphart's now classic text Democracies (Reference Lijphart1984, with around 5,000 Google Scholar citations), and its later revision as Patterns of Democracy (Reference Lijphart1999, Reference Lijphart2012, with over 10,000 citations), proposed a distinction between two ideal types: ‘majoritarian democracies’ on the one hand, versus ‘consensus democracies’ on the other. Lijphart used the term ‘majoritarian democracy’ interchangeably with ‘Westminster model’ and cited Britain as ‘both the original and the best-known example of this model’ (Reference Lijphart1999: 9). His well-known system was based on 10 indicators: five on the ‘executive–parties’ dimension (e.g. electoral system, party system, presence or absence of coalition government) and five on the ‘federal–unitary’ dimension (e.g. degree of territorial decentralization and presence or absence of bicameralism). In some respects this intervention added a degree of precision to a previously rather loose term. And yet – at Lijphart's own admission – his ideal type did not precisely apply in any country. For example, he associated unicameralism with majoritarian democracy, while Britain has a bicameral parliament – albeit with a second chamber he judged to be weak.

An alternative approach taken by some interpretivist scholars is to view the ‘Westminster model’ as a more cultural and historical phenomenon. Most notably Haig Patapan et al. (Reference Patapan, Wanna and Weller2005), and Rod Rhodes et al. (Reference Rhodes, Wanna and Weller2009) have explored ‘Westminster legacies’, particularly in Asia and the Pacific region. Their review of texts spanned from De Smith's 1961 piece to articles published in 2002 and concluded that the term encompassed various constitutional features and beliefs, and had various functions: serving for example as an ‘institutional category’, ‘legitimizing tradition’ or ‘political tool’ (Rhodes et al. Reference Rhodes, Wanna and Weller2009: 8). They explicitly ruled out developing ‘a set of institutions that can be established as an ideal model, against which the degrees of deviance [from the model] can be calculated for each country’, considering this a ‘possible but … rather sterile’ exercise (Rhodes et al. Reference Rhodes, Wanna and Weller2009: 224). Patapan et al. (Reference Patapan, Wanna and Weller2005: 2) proposed instead that the ‘Westminster model … provides a set of beliefs and a shared inheritance’.

For works following a more positivist tradition in political science this seems problematic. In particular, the term is frequently used (as seen below) to select cases for comparative analysis. Under this logic it will be used to draw – or at least imply – generalized conclusions. If comparative scholars frequently deploy a term with unclear or multiple meanings, this risks feeding flawed descriptive and causal inferences. In part driven by similar concerns, various other terms have been put under the microscope in recent years. For example, David Judge (Reference Judge2003: 501) questioned the utility of the term legislative ‘institutionalization’, arguing that on examination of the literature ‘there is little agreement as to exactly what its defining core characteristics are’. Ben Berger (Reference Berger2009: 335) suggested that the term ‘civic engagement’ should ‘meet a well-deserved end’, in favour of more precise alternatives. José Antonio Cheibub et al. (Reference Cheibub, Elkins and Ginsburg2014) used data from the Comparative Constitutions Project to challenge assumptions about the attributes commonly associated with presidentialism and parliamentarism. What links these exercises is a combination of rigorous analysis of concepts with empirical study, including treating the literature itself as data. The Westminster model seems long overdue such a test.

Concepts in political science

A valuable starting point in considering concepts in comparative political analysis is the widely cited text by Sartori (Reference Sartori1970). This set out requirements for classical political science concepts, introducing the key notions of conceptual ‘travelling’ (across time and space) and conceptual ‘stretching’ (to enable a concept to remain relevant to increasingly disparate cases). Connectedly, Sartori highlighted the relationship between the ‘extension’ of a term (to different cases), and its ‘intension’, defined as the ‘collection of properties which determine the things to which the [term] applies’ (Reference Sartori1970: 1041, quoting Salmon Reference Salmon1963, italics in original). These two things can often be in conflict: extending a term's use more widely may put its intension under strain. Sartori suggested that conceptual stretching could be avoided by ascending his well-known ‘ladder of abstraction’, to deploy a more general concept instead. Such considerations remain core to judging the essential attributes needed for political science concepts to be ‘good’ (Gerring Reference Gerring1999).

In later work, Sartori made proposals for rigorous testing of concepts, and particularly for ‘reconstruction’ of categories whose meaning had become unclear. He suggested that ‘[c]oncept reconstruction is a highly needed therapy for the current state of chaos of most social sciences’ and proposed a three-stage process to achieve this. ‘[F]irst collect a representative set of definitions; second, extract their characteristics; and third, construct matrices that organize such characteristics meaningfully’ (Sartori Reference Sartori, Collier and Gerring2009 [1984]: 122, 116). Hence the key is ‘reconstructing a concept from its literature’ (Sartori Reference Sartori, Collier and Gerring2009 [1984]: 121, italics in original). We take our cue from this suggestion.

It is important, however, to note that not all concepts are equal, and some require more parsimonious definition than others. Sartori was interested in ‘classical categorization, in which the relation among categories is understood in terms of a taxonomic hierarchy of successively more general categories’ (Collier and Mahon Reference Collier and Mahon1993: 145). A widely noted alternative to this is the ‘family resemblance’ idea. Here, cases share a set of properties, but not all cases share them all. As Gary Goertz (Reference Goertz2006: 36) articulated, whereas a classical category requires members to share n attributes, ‘the family resemblance rule almost always takes the form of “m of n”’. Using the notion of a ‘Westminster family’, this logic might seem suited to the Westminster model. Indeed some authors (e.g. Patapan et al. Reference Patapan, Wanna and Weller2005) have proposed this. We return to such suggestions towards the end of the article.

Methods and data

Given the centrality of the term ‘Westminster model’ in Lijphart's Reference Lijphart1999 book, and the need to delimit our data set, we began our search for meaning through an analysis of the academic literature starting at that point. Our endpoint is January 2017.

Our search was primarily based on academic bibliographic databases, using English-language texts.Footnote 1 We began with Scopus, using the set of largely interchangeable terms frequently found in the literature: ‘Westminster model’, ‘Westminster system’, ‘Westminster democracy’ and ‘Westminster parliamentary democracy’. We searched for these in the item's abstract or keywords, or for the single word ‘Westminster’ within its title. This found over 150 items, of which around one-third were excluded as irrelevant – because they were not substantive articles, or discussed topics largely unrelated to political science, or used the term Westminster purely literally (e.g. articles on the Westminster parliament which mentioned no such ‘model’, ‘system’, etc). This search was repeated for the JSTOR database and on Google Scholar, with duplicates removed. Altogether these searches resulted in 215 items, of which the great majority (202) were journal articles.

Such database searches will tend to overlook definitions embedded in books, although core texts could be important to the dissemination of a popular term. We hence also conducted searches of university reading lists. Selecting the top 10 political science departments in US universities and top five equivalents in the UK (based on QS World University Rankings), we identified core recommended texts from broad-based undergraduate and postgraduate taught courses in comparative politics. Where reading lists were not available online, we requested these from course tutors. In addition, building inductively on our analysis of extension (see below) we did the same for broad-based domestic politics courses from the same UK universities, and the top three in each of Canada, Australia and New Zealand. This resulted in 27 textbooks, which were carefully searched (on paper if not available electronically). Excluding items that did not mention the term, this brought our total number of texts to 239. Of these, 90 were texts broadly in comparative politics, 67 focused on British politics, and the remaining 82 were single-country studies focused elsewhere than the UK. It is the comparative and non-UK texts that interest us most, and which particularly inform the analysis below; but the UK-related texts are clearly also important in establishing public understandings of the term.

All texts were independently coded by two researchers, with a third adjudicating in cases of disagreement. We searched first for definitions of the Westminster model, second for attributes associated with it by the author(s), and third for countries to which the author(s) suggested it applied. Regarding definitions, all three researchers worked from a codebook developed deductively at the outset, with some initial refinement by the first coder. For attributes, categories were developed inductively from the data by the first coder, then refined (e.g. merging and splitting of categories) in consultation in the team, before second and third coding. The association of countries with the model in different texts was uncontroversial, and completed by the first coder only.

To what extent is the Westminster model defined?

The initial task was hence to search the 239 texts to determine whether or not they defined the Westminster model (or ‘Westminster system’, ‘Westminster [parliamentary] democracy’). The results are shown in Table 1. A definition was taken to be an explicit statement setting out what the author(s) in question considered to be the meaning of the term.Footnote 2

Table 1. Types of Definition of the Westminster Model, by Scope of Publication

We assigned each text to one of four categories, according to whether it contained a definition, and how complete this was. Only texts in the third and fourth categories (‘partial’ and ‘full’) actually contained a definition in the form just indicated. Combined, these accounted for only one-third of the total texts – 78 out of 239. The remaining two-thirds of texts did not provide anything that could be considered a clear statement of meaning. Definitions were far more common in UK-focused studies (50%) compared with comparative studies and texts dealing with other single-country cases (both 25%). These latter groups collectively make up over 70% of the data set.

The lack of clear definitions in many non-UK texts suggests that comparativists frequently assume the Westminster model to have a well-understood meaning. The most striking group of texts were those (representing 30% of the overall total) offering absolutely no definition at all. For example, one article proposed ‘A Framework for Evaluating the Performance of Committees in Westminster Parliaments’, but the only clue as to what a ‘Westminster parliament’ might be was the article's focus on Britain and Australia (Monk Reference Monk2010). Another piece discussed ‘three Westminster parliamentary democracies, Australia, Canada and New Zealand’, with the only expansion being that these were ‘Westminster-derived judicial systems’ (Kerby and Banfield Reference Kerby and Banfield2014: 342). The term ‘Westminster model’ (or similar) was hence often used in broadly comparative texts to imply presence of a well-defined sampling strategy, and in single-country studies to suggest that this was representative of a wider set of cases, without any overt rationale being provided. In many UK texts, in contrast, the term was simply used to describe the domestic context, without necessarily implying a comparative meaning.

Texts including an explicit definition or no definition offer two clear categories – but the largest group (38%) were those containing ‘implicit’ definitions, where the Westminster model was mentioned in combination with certain attributes or consequences, without clearly indicating that these contributed to its definition. Again, an understanding of the term seemed to be taken as read by these authors. As explored further below, the attributes mentioned in this context were quite diverse. For example, Jonathan Hopkin and Jonathan Bradbury (Reference Hopkin and Bradbury2006: 143) suggested that ‘the “Westminster model” of majoritarian party competition has traditionally placed a premium on party cohesion’, while Simon Hix and Abdul Noury (Reference Hix and Noury2016: 252) agreed that ‘the Westminster model assumes that parties can enforce legislative cohesion’. Amanda Bittner and Royce Koop noted how ‘[i]t is commonly assumed that majority governments are natural and proper in a Westminster parliamentary system’ (Reference Bittner and Koop2013: 48). Instead Peter Aucoin (Reference Aucoin2012: 177) noted that a ‘public service staffed independently of ministers on the basis of merit has long been a central feature of the Westminster model of public administration’.

Explicit definitions of a ‘partial’ kind shared some characteristics with these examples; they did include a distinct statement of meaning, but it was often far from complete. Some simply used a cross-reference to other work (often Lijphart) where a full definition could be found. For example, Frank Hendriks and Ank Michels (Reference Hendriks and Michels2011: 307) referred to Britain as ‘a strong example of majoritarian “Westminster democracy”’, compared with the Netherlands, which ‘shows strong characteristics of non-majoritarian “consensus democracy” (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1999)’. Other cases defined the Westminster model explicitly through reference to one or more attributes, without indicating whether this definition was intended to be complete. Hence Margaret Estevez-Abe wrote of ‘a Westminster system that centralizes power in the hands of the party leadership and prime minister’ (Reference Estevez-Abe2006: 633).

As might be anticipated, textbooks using the term tended to work harder to define it than other texts. Hence in a British context Matthew Flinders (Reference Flinders, Dunleavy, Heffernan, Cowley and Hay2006: 133) referred to the ‘pillars of the Westminster model’ being parliamentary sovereignty and ministerial responsibility, while going on to list various additional features. Other British politics textbooks likewise provided quite complete definitions (e.g. Kavanagh et al. Reference Kavanagh, Richards, Geddes and Smith2006; Leach et al. Reference Leach, Coxall and Robins2011). A New Zealand textbook claimed that the core of the model was ‘a centralised or unitary state’, supported by four ‘interlocking variables that contribute to this centralisation of political power’, which it listed (Miller Reference Miller2015: 32). Quite often full definitions, like the partial definitions cited above, deferred to other authors (most commonly Lijphart), reproducing lists of attributes drawn from their texts.

‘Intension’: where the Westminster model is defined, what meaning is it given?

Our first finding is therefore that the term ‘Westminster model’ is far from universally clarified by authors who deploy it, particularly in comparative politics – though some detailed and fairly complete definitions do exist. However, we have already seen that there is diversity among the attributes that authors associate with the model, while some of those who have paid it the most careful attention emphasize the slippery or contested nature of the term.

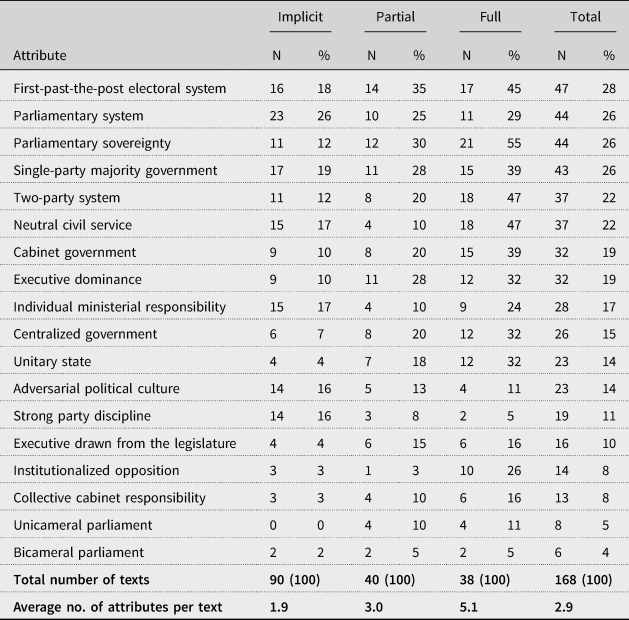

Having identified 168 texts which offer some indication of attributes associated with the model (whether as part of a full, partial or implicit definition), we can explore the diversity of these attributes, and the extent of agreement over which ones apply. That is, following Sartori, to investigate the ‘intension’ of the term. Table 2 lists the commonest attributes identified in these 168 texts, rank ordered by overall prominence and categorized according to the fullness of definition. As already indicated, attributes were coded inductively and as far as possible based on the original authors’ words, but subsequently grouped into categories where these references fairly clearly had the same meaning (see examples below the table).

Table 2. Attributes Associated with the Westminster Model, by Type of Definition

Notes: Definitions: first-past-the-post includes references to single-member plurality, but not simply to ‘majoritarian’ system; parliamentary system includes indication executive is dependent on legislative confidence; single-party majority government excludes texts referring only to one of these attributes; neutral civil service includes similar terms such as ‘impartial’; strong party discipline includes reference to strong/high party ‘cohesion’; executive drawn from the legislature includes reference to ministers sitting in parliament.

The attributes listed are diverse, and the boundaries between them sometimes blurred. As in Lijphart's version of the model, some attributes (such as a two-party system and single-party majority government) are clearly interlinked. Others (e.g. executive dominance or adversarial political culture) would be difficult to define or measure precisely, and are closer to being consequences of the model than institutional rules. Notably, the table also demonstrates some direct contradiction: eight texts (primarily in an application of Lijphart) considered unicameralism or quasi-unicameralism to be part of the model, while six authors instead associated it with bicameralism. For example, Dag Anckar (Reference Anckar2007: 641) stated that Caribbean ‘[c]ountries that adopted at independence the bicameral method are Westminster countries; others are not’.

Despite the imperfect nature of the categories, the table provides some clear indications of attributes most commonly associated with the model. Texts hinting at intension while falling short of a definition referred on average to just under two attributes, the most common of which was being a parliamentary system. Perhaps surprisingly, this attribute was not the most frequently mentioned among texts containing explicit definitions – though the countries cited as conforming to the model (discussed below) were almost exclusively parliamentary. The omission of this seemingly central attribute from many explicit definitions is partly attributable to Lijphart's interpretation, which eschewed the established dichotomy between parliamentary and presidential systems, to suggest a different dividing line between majoritarian and consensus democracies. Texts citing Lijphart hence often omitted this attribute. However, various other texts did so as well – perhaps considering it too obvious to mention.

The association between the Westminster model and parliamentarism is sufficiently strong that various authors took one as a synonym for the other. Hence Abdul Aziz Bari (Reference Bari2007: 2) suggested that Malaysia is ‘a Westminster democracy – which is also known as parliamentary democracy’. The Westminster model was often defined against an alternative of US-style presidentialism; for example, a Canadian text discussed ‘the contrast between a presidential/congressional political system and a Westminster parliamentary system: power concentrated versus power dispersed’ (Simeon and Radin Reference Simeon and Radin2010: 7). Discussing South Africa, one author suggested that ‘[d]espite the apparent unsuitability of the Westminster model, the opposite model of a clear separation of powers has never been a serious alternative’ (Nijzink Reference Nijzink2001: 54).

The Westminster model is hence often presented as an archetypal parliamentary system. Nonetheless, some authors take care to address the diversity of such systems, instead presenting it as an archetype amongst them. For Kaare Strøm et al. (Reference Strøm, Narud and Valen2005: 782), ‘[p]arliamentary democracy comes in many forms, but one of the most venerable and influential is the Westminster model’. Philip Norton (Reference Norton, Jones and Norton2014: 269) expanded, suggesting that ‘[t]here are two basic types of parliamentary government: the Westminster parliamentary system and the continental’ – where the former ‘stresses single-party government, elected normally through a first-past-the-post electoral system’, and the latter ‘places stress on consensus politics’. Lia Nijzink (Reference Nijzink2001: 55) also acknowledged this distinction, noting that ‘[i]n addition to the presidential–parliamentary contrast between fusion and separation of powers, there is a further important difference between Westminster's executive dominance and the continental European pattern of executive-legislative balance'.

Texts containing full definitions mentioned on average just over five different attributes. The most frequent among them (identified by a little over half such texts) was parliamentary sovereignty, and its corollary of an unwritten constitution. This was another of the highest-ranking attributes overall, and mentioned particularly frequently in the UK texts. Hence James Mitchell (Reference Mitchell2010: 101) indicated that ‘[a]t its core, the Westminster model focuses on the centralised nature of power legitimated through a popularised version of Dicey's doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty’. But the attribute also appeared fairly frequently in non-UK texts. Thus Geoffrey Palmer and Matthew Palmer (Reference Palmer and Palmer2004: 596), writing in a New Zealand context, suggested that ‘Westminster systems of government … [are] founded … on a bedrock doctrine of Parliamentary sovereignty that, in theory, privileges the legislature over all else, including the judicial branch of government’. Andrew Harding (Reference Harding2004), in a broad comparative text, proposed that this feature was at the heart of the model.

Table 2 demonstrates how there is no single attribute which authors explicitly agree characterizes the Westminster model. But purely quantitatively, the contest is narrowly won by a country's possession of a first-past-the-post electoral system – cited in just under a third of all texts. For example, Jack Vowles (Reference Vowles2000: 684) suggested that first-past-the-post is ‘[o]ne of the deepest foundations of the Westminster model’. Some authors, indeed, treated the model as synonymous not with parliamentarism, but with this. In an article focused on electoral systems, Michael Pinto-Duschinsky (Reference Pinto-Duschinsky1999: 116) stated that in Britain ‘the current method of election [is] by first-past-the-post in single-member constituencies (the Westminster model)’, and used this to suggest that ‘the Westminster Model is used in 62 countries and by 49% of the world's electors’. This electoral system is clearly closely linked to other very widely cited features – including a two-party system and single-party majority governments. Likewise these are connected to less tangible attributes such as executive dominance – for example, described as ‘a strong executive authority’ (Burgess Reference Burgess1999: 3) or ‘executive supremacy’ (Gamble Reference Gamble, Dunleavy, Gamble, Heffernan and Peele2003: 20).

Instead, for a different set of authors, focused on public administration, the central feature of the Westminster model was a neutral civil service. Hence Raymond Miller (Reference Miller2006: 259) pointed out that in New Zealand, ‘[i]n the Westminster tradition officials are presumed to be non-partisan servants of the Crown’. Likewise David Richards and Martin Smith (Reference Richards and Smith2004: 783) emphasized that the ‘Westminster model sees officials as neutral, permanent and loyal’. As with electoral systems, some such texts referred to no other attributes beyond civil service neutrality and ministerial responsibility in indicating the model's meaning. But these attributes were also frequently mentioned in other texts.

Connected to the notion of executive dominance, various authors stressed the importance of centralization to the Westminster model. For example, Flinders (Reference Flinders2011: 2) pointed to a ‘centralising ethos [and] power-hoarding logic’. One key manifestation of this is the expectation of a unitary rather than a federal state – cited in around one-third of texts containing a full definition, in part due to its inclusion in Lijphart's schema.

A number of authors also highlighted party behaviour in the legislature. In a single-country case study based on the UK, Andrew Eggers and Arthur Spirling (Reference Eggers and Spirling2016: 20) echoed comments cited above when suggesting that ‘[s]trong party discipline is a defining feature of legislative politics in Westminster systems’. Similarly, in a broad comparative text, Hix and Noury (Reference Hix and Noury2016: 252) suggested that a Westminster model of legislative politics is underpinned by a governing party ‘which can enforce Party cohesion in votes … [with] the main weapon [being] the threat of a vote-of-confidence’. This again suggests some blurring between Westminster systems and parliamentary systems more broadly – and perhaps implicitly a comparator of US presidentialism.

This analysis of the Westminster model's ‘intension’, in terms of the features most commonly associated with it, provides a somewhat confusing picture. Most features listed present a fairly accurate account of the traditions of UK government. But whether they describe a ‘model’ with real comparative application remains distinctly open to doubt.

Extension: where is the Westminster model thought to apply?

We can shed more light on this question by exploring the extension of the Westminster model: that is, the countries to which authors suggest it applies. Here, all 239 texts in the data set (i.e. including those containing no definition) were included in the analysis. In total, 35 countries were mentioned, but many no more than a handful of times.Footnote 3 The top 10 countries identified are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Countries Most Commonly Identified as Conforming to the Westminster Model

Unsurprisingly, the country almost universally mentioned is the UK. References to Canada, Australia and New Zealand were also particularly frequent. Notably, and again unsurprisingly, all of the countries listed in the table (and most of those included in note 3 below) have a British colonial heritage and are (with the exception of Ireland) Commonwealth members. This immediately suggests a common linkage of shared cultural history. To a greater or lesser extent, these countries adopted institutions long ago which were influenced by UK traditions. But today, are there tangible common attributes that apply to these countries, which could in any sense imply a ‘model’ of government?

Fifty years ago, Mackintosh (Reference Mackintosh1970) considered that the ‘Westminster model’ had become an increasingly unreliable guide and imperfect fit for Victorian Britain. Recent years have seen continued lively debates among British politics scholars about the extent to which the UK can be said to conform to the model. Various factors have contributed to these doubts – for example, Britain's accession to the EU in the 1970s raised significant questions about parliamentary sovereignty. But the largest cause for reflection has been the programme of reform introduced by the Labour governments of 1997–2010, which included territorial devolution to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, partial reform of the House of Lords and the introduction of a Human Rights Act. Authors have respectively suggested that these introduced ‘quasi federalism’ (Gamble Reference Gamble2006: 22), stronger bicameralism (Russell Reference Russell2013) and greater judicialization (Bevir Reference Bevir2008). Subsequent to this, the 2010 general election resulted in a coalition government, ending a period of single-party governments previously uninterrupted since 1945; the election of 2017 later resulted in a single-party minority government. Even before all of this had played out, authors such as Flinders (Reference Flinders2005, Reference Flinders2009) and Robert Hazell (Reference Hazell2008) had sought systematically to assess constitutional change against Lijphart's articulation of the Westminster model, acknowledging at least some shift. Pippa Norris (Reference Norris2001: 881) was an early exponent of such views, arguing that constitutional change had moved the UK away from the Westminster model, and that its system was ‘becoming more like the political systems in Australia and Canada’.

This latter comment implies that other frequently cited countries do not conform to a shared pattern either, and that there is diversity among supposed ‘Westminster model’ countries. In fact, as Wanna (Reference Wanna2014: 20) has observed, ‘the relatively few remaining jurisdictions that identify with Westminster are all very different to each other and behave differently’.

Lijphart noted in his original (Reference Lijphart1984: 19) text that ‘[i]n nearly all respects, democracy in New Zealand is … a better example of the Westminster model, than British democracy’. The country demonstrated a clear concentration of power, being unitary, (since 1952) unicameral and using a first-past-the-post electoral system that routinely resulted in single-party governments. This last feature then ended in 1993, with a move to the mixed-member proportional (MMP) system, which had knock-on effects for the composition of parliament, and in turn, New Zealand governments. Nonetheless, in the post-1999 literature, New Zealand continues to be cited frequently as an exemplar of the model. As Chris Eichbaum and Richard Shaw (Reference Eichbaum and Shaw2011: 585) suggest, ‘[n]otwithstanding its adoption of proportional representation, [New Zealand] retains several elements of the family of ideas that constitute Westminster’. Indeed, the New Zealand Parliament (2014) itself suggests that ‘[o]ur parliamentary system is known as the Westminster model after the British system based at Westminster in London’.

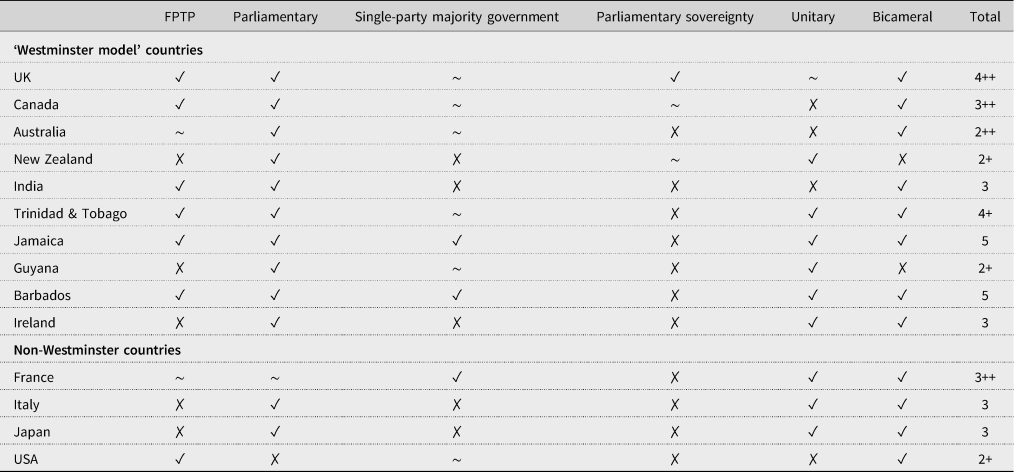

Deviations from the perceived model are likewise seen in most other countries with which it is frequently associated, as illustrated in the top half of Table 4, which links the top 10 countries to six key attributes identified earlier in the article. The attributes included are the most frequently cited, excluding those which are less measurable (such as ‘executive dominance’), and limited to those which are clear-cut or for which reliable data sets are available.Footnote 4 We depart here from Lijphart by selecting bicameralism as part of the model, in line with UK practice. The most widely violated expectation is that of parliamentary sovereignty (implying an unwritten constitution), which essentially applies nowhere beyond the UK. Seven of the 10 countries have a single constitutional document, while New Zealand and Canada have ‘constitutions consisting of multiple texts’ (Melton et al. Reference Melton, Stuart and Helen2015: 10). Beyond this, most other countries violate at least one further expectation. This particularly applies among the countries most widely cited as adhering to the model. The UK itself reliably demonstrates only four of the six key attributes, while most other cases reliably demonstrate no more than three.

Table 4. Key Attributes as Observed in ‘Westminster’ and Non-Westminster Countries since 1999

Notes: FPTP = first-past-the-post; ✓ = yes; ✗ = no; ~ = partly fulfilled (e.g. majoritarian, but non-FPTP, elections; some single-party majority governments; devolution of powers to regions; corpus of laws with constitutional status). Total calculated as number of attributes fulfilled, with additional symbols reflecting any partly fulfilled.

Among our texts, Canada is cited as ‘the first modern federation to combine the so-called Westminster model of parliamentary government with the federal system of government’ (Burgess Reference Burgess1999: 2), the Canadian federation dating to 1867. Plus, while the federal parliament continues to use first-past-the-post, election results since 1999 have frequently resulted in minority governments. Hence some authors have recently suggested that ‘[a]mong Westminster systems, Canada is the deviant case’ (Johnston Reference Johnston and Courtney2010: 208). Others refer to ‘more consensual Westminster systems such as Canada’ (Caramani Reference Caramani2017: 43).

Australia is also widely cited, but its deviations are almost certainly greater. It is a federation which within 20 years of its formal establishment in 1901 had switched from first-past-the-post to the majoritarian alternative vote (AV) for lower house elections, while in 1948 the Senate (which was always wholly elected) moved to a proportional representation system. Hence, although many continue to see Australia as a ‘Westminster model’ country, it is also widely noted that ‘Australian political practice has long outgrown the original model to which its founding fathers looked’ (Weller Reference Weller, Galligan and Roberts2008: np). Likewise various authors have pointed out key deviations from the model in India, in terms of both federalism and its ‘large multi-party system’, though the country retains first-past-the-post (Heath et al. Reference Heath, Glouharova, Heath, Gallagher and Mitchell2006: 137). In addition, Mahendra Singh and Douglas Verney (Reference Singh and Verney2003: 11) have suggested that ‘India is unique in its Westminster form of parliamentary federalism’, because ‘whereas Canada and Australia retain the monarchy, India alone is a republic’.

Such deviations from the Westminster model among its best-known exemplars have been frequently noted (e.g. Dunleavy Reference Dunleavy2010, Paun Reference Paun2011). Less noted, however, is the extent to which the model – despite its shakiness – has been presented as a pole to which other systems, sharing little of the heritage of those in the Commonwealth, may or may not adhere. These claims go beyond countries with an obvious shared cultural inheritance. For example, in line with authors viewing the Westminster model as synonymous with first-past-the-post, David Kretzmer (Reference Kretzmer2006: 65) has claimed that a move away from multipartyism in Israel ‘could only be achieved by abandoning the system of proportional representation in favour of a system similar to the Westminster model’. Strøm et al. (Reference Strøm, Narud and Valen2005: 785–786) observed that in the 1960s Norway ‘looked much like a Westminster system’, but subsequently ‘moved away from this model’ due to a more fragmented party system, minority government and increasingly assertive judiciary. Meanwhile, writing on Japan, Estevez-Abe (Reference Estevez-Abe2006: 633) claimed that ‘whether voters intended to do so or not, Koizumi's 2005 landslide [had] cast the die in favor of a Westminster system that centralizes power in the hands of the party leadership and prime minister'.

Hence the Westminster model appears to be a movable feast. Deviations away from almost any of its key features are insufficient for a country with a certain cultural heritage to shed the label. Meanwhile, adopting very few such features can raise questions about whether a new country with a different heritage has entered the fold. Both of these usages imply that the Westminster model is a well-defined concept, but this appears to be far from the case.

A relatively modest claim would be that the Westminster model is closer to a ‘family resemblance’ concept than to a ‘classical’ social science concept of the kind recognized by Sartori, which could seem fitting with the history of the term. After all, authors often speak of the ‘Westminster family’, referring to countries which share a common British parentage. Various authors hint at this kind of conceptualization. For example, Harding (Reference Harding2004: 146) suggests that ‘[w]hile one can identify essential features, hardly any one of these can be said, logically, to be essential in the sense that if it is missing in a given instance the Westminster model does not apply or has ceased to exist’.

Yet in strict social science terms Table 4 demonstrates that the concept does not even meet the formal, albeit loose, requirements of family resemblance – in terms of a minimum number of clearly definable features being shared. Australia and New Zealand each consistently display only two of the attributes listed (and have just one overlapping: parliamentarism), while Canada and India consistently display only three. But, as indicated at the bottom of the table, other examples from beyond the traditional ‘family’ share just as many of these core attributes. France uses a majoritarian electoral system, is unitary, only semi-presidential and has similar weak-to-medium-strength bicameralism to the UK. Nowhere, however, is it suggested that France should be considered a Westminster model democracy. Despite the comment above, it is far from mainstream to consider Japan an exemplar of the model, but it is aligned on the same number of attributes as Canada and India – as is Italy. Meanwhile the US practises first-past-the-post, has a two-party system and is bicameral; but its system is widely presented as the polar opposite of the model. This strongly suggests that any ‘Westminster family’ exists only in the natural language sense – of individuals sharing a common ancestor – rather than in formal social science terms. And for all countries – even the UK – the shared ancestor is now becoming increasingly distant.

Some authors have suggested that certain supposedly Westminster model countries are better considered a kind of hybrid. Elaine Thompson (Reference Thompson1980) coined the term ‘Washminster’ to describe Australia's fusion of certain Westminster elements (notably parliamentarism) with others more akin to US government in Washington, DC (notably a strong directly elected Senate), and this term continues to be used (e.g. Bach Reference Bach2003). David Butler (Reference Butler1974) simply preferred to describe the Australian variant as the ‘Canberra model’. More recently, Harshan Kumarasingham (Reference Kumarasingham2013: vi) has suggested the term ‘Eastminster’ to capture the export of UK-style institutions to India and Sri Lanka, which ‘altered and adapted the Westminster system for their own soil’. But while these hybrid terms are intended to respect and reflect deviations from the original, such deviations are (at least by now) almost universal. Nearly two decades ago, Norris (Reference Norris2001: 878) suggested that ‘we are perhaps witnessing the twilight of the pure Westminster model, with only a few states like Barbados continuing to cling to this ideal’. Table 4 clearly supports this view. Nonetheless, even suggesting that the Westminster model survives in the Caribbean is not wholly uncontroversial. Matthew Bishop (Reference Bishop2011: 421) has described Caribbean variants as ‘in many respects a caricature of Westminster with the intensification of many of its least desirable aspects’, resulting not in the formerly benign Westminster, but instead in a ‘Westmonster’ which must be slayed.

Conclusion

We have followed Sartori's (Reference Sartori, Collier and Gerring2009 [Reference Sartori, Collier and Gerring1984]) advice in seeking to ‘reconstruct’ the concept of the Westminster model, by reviewing its use in the recent comparative literature. Particularly when going beyond UK-focused studies we found that the term is frequently used with little or no definition. This is perhaps because some authors believe, in line with Peter Kerr and Steven Kettell (Reference Kerr and Kettell2006: 7), that ‘[t]he central features of this model are by now so well-known that they are barely worth recounting’. But our analysis of how the literature describes both the term's intension (the properties with which it is associated) and extension (the specific cases to which it is thought to apply) shows this not to be the case. The model is associated with numerous properties, given varying weight by different authors. It is also associated with numerous countries, key exemplars of which display few of the clearly definable properties that are most commonly discussed.

We did not conduct a full historical analysis of the literature, but it seems clear that the Westminster model has had different meanings over time, all of which continue to have some vestigial use. At the outset it described the traditions of British government in a crucial period when the franchise was widening and modern democracy being cemented. Some authors continue to use it as shorthand for the political institutions that characterize (or, alternatively, used to characterize) the UK. But the term is also widely used in broader comparative politics, often denoting a political system that was influenced by UK institutions. For some authors it is (erroneously) a term interchangeable with parliamentarism – as distinct from what is seen as its polar opposite, US presidentialism. For others it is a special case of parliamentarism, founded on a majoritarian (normally first-past-the-post) electoral system – or indeed shorthand for that electoral system itself. For many public administration scholars, the term instead denotes something about civil service culture, while some others associate it with centralization (notwithstanding the fact that several of the most commonly cited exemplars are federal states).

Alongside these fragmentary approaches, Lijphart's (Reference Lijphart1984, Reference Lijphart1999, Reference Lijphart2012) interventions have been influential. His work made the term ‘Westminster model’ synonymous, in the minds of many, with an ideal-type majoritarianism. In one sense these interventions injected new life, and a new precision, into an ageing and distinctly cloudy term by suggesting 10 attributes associated with such a model. However, this compounded the confusion, because Lijphart's ideal type did not apply in any existing country, while some countries previously strongly associated with the ‘model’ did not share the attributes proposed.

Hence while the ‘Westminster model’ may once have had a meaning (or meanings), a combination of conceptual confusion among authors and real-world change have seen it stretched beyond recognition. As Collier and Mahon (Reference Collier and Mahon1993: 845) note, ‘the problem of conceptual stretching can arise not only from movement across cases but also from change over time within cases’. Both problems clearly apply to supposedly Westminster model countries. By now the term has gone well beyond individual cases of what Sartori referred to as ‘individual ambiguity’ to achieve a damaging state of ‘collective ambiguity’ in the literature (Reference Sartori, Collier and Gerring2009 [1984]: 111).Footnote 5

Whether adhering to Lijphart's version or not, political scientists today often reach for the term ‘Westminster model’ relatively casually, assuming that its meaning is clear and thereby imbuing it with a faux precision. Practitioners, in turn, may assume that a term frequently used by political science academics has a solid basis. In reality, however, comparative politics scholars seem frequently to deploy the term either as a convenient cloak to imply that single-country studies have comparative application, or to suggest that a rational sampling or case selection strategy was used in small-n comparative studies. Sometimes this may provide a cover for what is essentially a convenience sample, based on English-speaking jurisdictions. Indeed, some users of the term appear to betray limited understanding of cases beyond the English-speaking world – hence the frequent contrast with US presidentialism.

Following Sartori, authors are often attempting to ascend too far up the ladder of abstraction, to reach for a broad term, but the term chosen is one with no clear empirical basis. Comparativists need instead to focus lower down the ladder, on the variables of explicit relevance to their analysis, if their conclusions are to have any capacity to travel beyond the cases at hand. Hence, if studying the effects of first-past-the-post electoral systems, it is wholly justified to include the UK alongside the US. If studying weak-to-medium strength bicameralism, or the culture of large parliamentary chambers, it is appropriate to compare the UK with France. Of course, this is precisely what many good comparativists already do. In contrast, justifying case selection on the basis that cases are ‘Westminster model’ countries risks feeding false descriptive and causal inferences, and false generalization. It also perpetuates a false impression among practitioners that a meaningful ‘family’ of political systems exists.

Language in political science and politics changes, and terms regularly fall out of use when they become outdated. For example, the term ‘Third World’ rose to prominence at around the same time as the ‘Westminster model’, but many now consider it inappropriate as a description of a set of diverse countries which should not merely be pigeonholed by reference to (previously) more dominant comparators (Solarz Reference Solarz2012). The strongest argument for common bonds between ‘Westminster model’ countries is one based on heritage, and hence possibly on culture. Yet continued emphasis on this ‘family’ risks trapping certain countries, whose systems now radically differ, in a colonial past. Scholars wanting to compare systems with a shared British heritage should make this attribute explicit, and justify why it is an appropriate one to include within their sampling or case selection strategy. Otherwise, we suggest, it is time for the ‘Westminster model’ to be retired.