1. Introduction and objectives

Following the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008, and the unexpectedly slow recovery of the global economy from that crisis, there has been much debate on the trajectory of economic growth globally. These debates have surfaced a wide range of ‘heterodox’ thinking and alternative positions within and beyond conventional macroeconomics. This paper aims to summarise some of the main issues of contention and the range of positions on the future of economic growth which have emerged in recent years, before considering what they might mean for health care systems and health care expenditure. Its purpose is to fill an apparent gap in the policy research literature, by relating what is understood about the drivers of health care expenditure and sustainability to a range of different scenarios for the future of economic growth.

This paper sets out data on trends in global gross domestic product (GDP) growth and health expenditure. It then summarises briefly evidence on the relationship between GDP and health expenditure. It then considers a number of the most critical current debates on the future of economic growth. The potential consequences of different scenarios for health care systems and financing are then assessed, and key implications for global health care and health financing policy explored. The complex relationship between GDP growth, health expenditure, and the welfare-maximising level of health spending under these scenarios is then considered.

2. Recent trends in economic growth

Maddison (Reference Maddison2003) offers a comprehensive discussion of historical trends in economic growth. He estimated that rates of global GDP growth were negligible or very low (between 0 and 0.3%) until around 1500; after which time Western Europe and what Maddison calls the ‘Western Offshoots’ began to experience accelerating growth into the 19th and 20th centuries. Global growth rates for GDP per capita then peaked in the period 1950–73, before slowing thereafter.

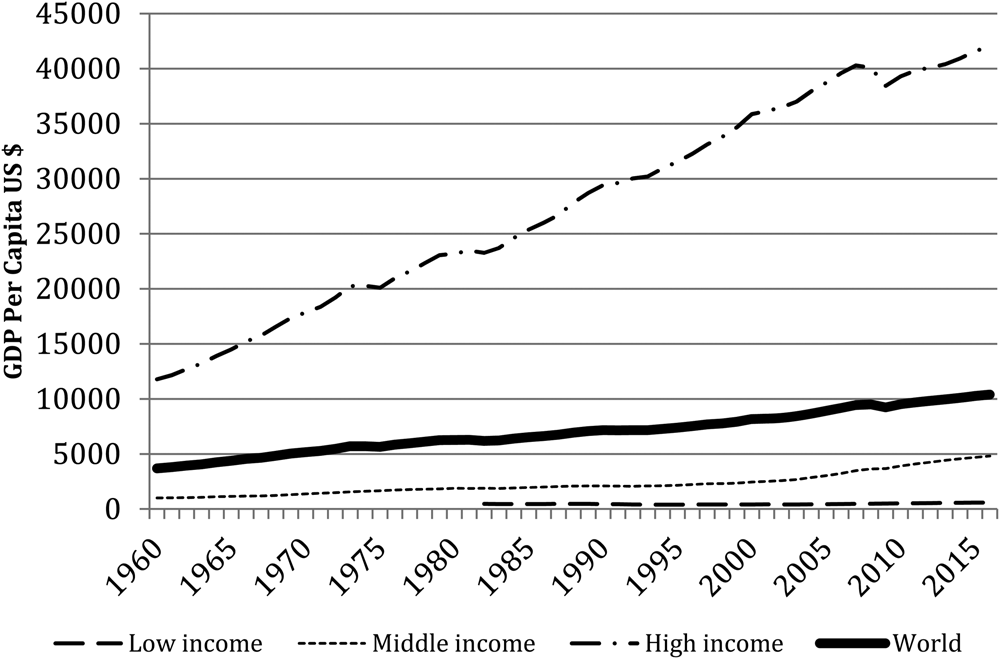

Figure 1 presents global real GDP per capita for the years 1960 to 2016. Three issues stand out from Figure 1. First is the scale of divergence between GDP per capita in the high-income countries and the low-income countries. Second is the pronounced impact of the GFC on the global economy in aggregate, and on high-income economies specifically. Third is the fact that GDP per capita in the high-income countries has only recently returned to its pre-crisis level.

Figure 1. Global GDP per capita, 1960–2016 (2010 US$).

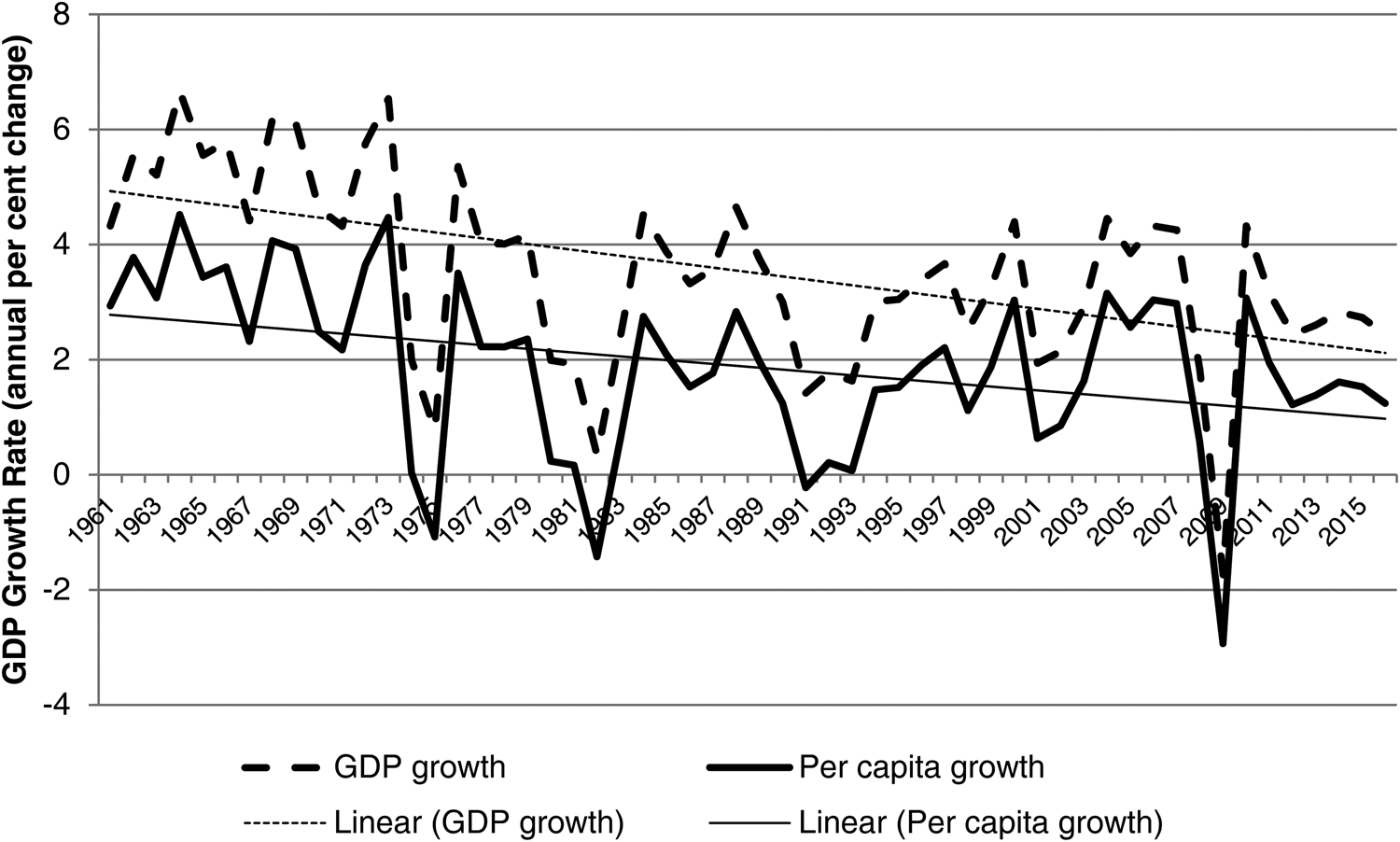

Figure 2 presents annual real global growth rates in GDP and GDP per capita from 1961 to 2016. Worth noting from this chart is how much higher global GDP growth was during the 1960s than in subsequent decades (made clearer by the use of linear trend lines). It also shows how dramatic was the impact on GDP growth of the GFC, and how subdued global growth has been since the crisis relative to the preceding decade.

Figure 2. World real GDP growth and per capita GDP growth rates, 1961–2016.

Figure 3 shows World Bank data on Total Health Expenditure as a proportion of GDP (a series which commences in 1995). It clearly shows the impact of the GFC as the inverse of that seen in the preceding GDP figures, in that a fixed (or even a falling) total health expenditure represented a higher proportion of total GDP, as the latter fell dramatically during the crisis. The health share of global GDP has remained largely static since the GFC.

Figure 3. Global total health expenditure as percent of GDP, 1995–2014.

Overall, these figures show a number of key trends of particular relevance. First, a clear secular trend towards slower global per capita GDP growth over time. Second, a more recent trend towards flat or only limited growth in health care expenditure as a share of global GDP. Third, and notwithstanding the many and diverse complexities of international comparative data, little or no evidence of the desired ‘grand convergence’ in the proportion of resources invested in health between rich and poor countries (Jamison et al., Reference Jamison, Summers, Alleyne, Arrow, Berkley, Binagwaho, Bustreo, Evans, Feachem, Frenk, Ghosh, Goldie, Guo, Gupta, Horton, Kruk, Mahmoud, Mohohlo, Ncube, Pablos-Mendez, Reddy, Saxenian, Soucat, Ultveit-Moe and Yamey2013).

3. Health care expenditure and economic growth

The relationship between health care expenditure and GDP has been the subject of extensive study by health economists for decades. Comprehensive reviews of the rich literature in this field have been undertaken by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2006), Busse et al. (Reference Busse, Van Ginneken, Normand, Figueras and McKee2012), Velenyi (Reference Velenyi and Scheffler2016) and Getzen (Reference Getzen and Scheffler2016). These reviews all point to a well-documented positive relationship between health care expenditure and GDP both over time and between countries, showing over the long run that health care expenditure has tended to grow faster than GDP. Even though data are only systematically available since the 1960s in developed countries (and only more recently in developing countries) there is less evidence of medical care consuming a growing share of GDP much before the 1950s (Getzen, Reference Getzen and Scheffler2016; Gordon, Reference Gordon2016). Much of the literature in this area has focused on this post-1960 phenomenon of ‘excess growth’ (i.e. growth in health spending per capita running ahead of growth in GDP per capita). This research followed Newhouse's (Reference Newhouse1977) initial conclusions that health care appeared to have the characteristics of a luxury good (i.e. an income elasticity greater than one), and that increasing income (GDP per capita) was the dominant explanatory factor for increasing health care spending. Much of the subsequent debate has focused on the implications of this excess growth. Amongst others, Newhouse (Reference Newhouse1992) has argued that this phenomenon tends to buy additional medical care of ever-decreasing marginal value, and is hence likely to represent a welfare loss for society if this trend continues. In contrast, others have argued that, as individuals and societies grow richer, ‘…the most valuable channel for spending is to purchase additional years of life’ (Hall and Jones, Reference Hall and Jones2007: 68). A familiar range of other potential drivers of rising health care expenditure has been discussed at length, including demographics (especially ageing), the impact of new technologies, and the ever-increasing uptake and over-utilisation of existing technologies (Velenyi, Reference Velenyi and Scheffler2016), while others (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Finkelstein and Notowidigdo2012) have continued to challenge the empirical basis of the apparent dominance of affluence in this regard. Nonetheless, this debate remains as topical as ever as countries continue to grapple with the sustainability of health systems (e.g. House of Lords, 2017).

4. Future growth: debates and scenarios

This section considers a range of explanations for the weakness of global growth since the GFC, before exploring a range of other considerations which may bear upon the future prospects for economic growth, and attempting to draw out the likely implications for health care of alternative scenarios.

4.1 Structural low growth

Following the GFC, many countries' growth rates (and in a number of the worst-affected countries, growth levels) had not returned to pre-crisis levels even after several years. One interpretation of this has been to suggest that the GFC provides evidence of particularly strong hysteresis effects (Ball, Reference Ball2014), with the crisis itself causing such severe long-term damage to a number of countries that they have been unable to recover to pre-crisis growth rates or output levels. Summers (Reference Summers2015) points to an unintended effect of the ultra-low interest rates which have been forced upon post-crisis monetary policy in much of the developed world. Summers (Reference Summers2015) argues that negative real interest rates have interacted with the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates to impose a long-term constraint on aggregate demand, causing the phenomenon of secular stagnation. This argument is pursued by Eichengreen (Reference Eichengreen2015), who suggests that secular stagnation is driven in the short run by this downward trend in the real interest rate. He argues that this reflects an excess of desired savings over available investment opportunities, resulting in a persistent output gap and low growth rates. However, he also points to a range of longer-term phenomena that might be expected to reinforce persistence in secular stagnation. These include falling relative prices of investment goods (interacting with savings gluts) and the effects of population ageing.

In the United States, Gordon (Reference Gordon2016, Reference Gordon2012) points to a range of deeper structural forces (or ‘headwinds’) at work that will arguably depress economic growth rates substantially into the future. Gordon suggests that secular stagnation emanates from the supply side, as the short-lived and smaller impacts of the information technology revolution on productivity growth (relative to the two previous ‘industrial revolutions’ of modern history) dissipate. He suggests this trend will be cemented by six other ‘headwinds’: demography and ageing, limited scope for further population-level educational gains, growing inequality, globalisation, the costs of averting (or failing to avert) environmental damage and persistently high levels of private and public debt. Gordon's focus on demography (especially the transition to retirement of the baby boomers), and limited productivity impact of the information technology boom, as explaining this ‘new normal’ for the US economy has been supported by others (e.g. Gagnon et al., Reference Gagnon, Johannsen and Lopez-Salido2016; Bonaiuti, Reference Bonaiuti2017; Sharma, Reference Sharma2017).

Delli Gatti et al. (Reference Delli Gatti, Gallegati, Greenwald, Russo and Stiglitz2012) provide an alternative structural explanation for the persistent growth crisis in developed nations. They argue that we are witnessing the terminal decline of manufacturing in developed nations, with technological change and innovation leading to lower incomes at a faster rate than workers can transition effectively to new industries. They suggest this is directly analogous to the Great Depression of the 1930s, which itself represented the terminal phase of the decline of agriculture as a large source of employment.

4.2 Avoidable low growth

Around 2010, decisions were made in many countries to reduce or cease post-GFC stimulus spending. This cessation of stimulus occurred because it was feared that increasing public debt burdens would dampen growth and recovery. However, increasing evidence has since suggested that this austerity ‘turn’ was, in fact, misguided. IMF internal research (Ostry et al., Reference Ostry, Ghosh and Espinoza2015) has increasingly suggested that the costs (in reduced investment) of attempting to reduce public debt in most economies will outweigh the ‘crisis insurance’ benefit of lower debt. More recent research by House et al. (Reference House, Proebsting and Tezar2017) goes further, suggesting that not only did European policies cause an austerity shock that retarded the recovery of GDP, they actually resulted in higher public debt to GDP ratios. Meanwhile, adherents of the modern monetary theory (MMT) school argue that a range of key assumptions underlying orthodox treatments of monetary economics are fallacious, and therefore result in significant policy errors (e.g. Nersisyan and Randall Wray, Reference Nersisyan and Randall Wray2016). MMT proponents argue that, for sovereign currency issuing governments, specific budget outcomes (whether surplus or deficit) are not meaningful targets for policy, but that fiscal policy should simply be a tool by which to achieve socially desirable goals, and that austerity represents pointless sacrifice (Kelton, Reference Kelton2015).

It is, however, less clear how the anti-austerity and MMT perspectives interact with a structurally determined slow-down in economic growth. Avoiding austerity in times of recession is a relatively simple concept, which appears to be re-gaining respectability in light of experience. Whether the effective relaxation of deficit constraints on governments under MMT can provide a sufficient (or even a significant) counterweight to structural factors driving lower growth rates is less clear. MMT will not support unlimited and open-ended public spending on health care in perpetuity if underlying growth dynamics are being affected by structural factors such as population ageing – under MMT, real resource constraints (as opposed to purely financial constraints) do impose limits on government spending (Kelton, Reference Kelton2015). It is also important to remember that MMT could not have helped the Southern European Eurozone members out of their fiscal crises, as these nations did not retain sovereign control of their monetary policy.

4.3 Fragile growth

The ‘secular stagnation’ argument suggests that, while growth rates may remain low for years or decades to come, the crisis – while not necessarily the cause of the stagnation – is now past (Summers, Reference Summers2015). By contrast, a number of other economists have suggested that the world's economic woes may not end simply with current low growth rates, but that a variety of forms of fragility may augur a further potential economic crisis, risking even greater negative impacts on future growth. These perspectives are broadly in the tradition of Hyman Minsky's financial instability hypothesis (Minsky, Reference Minsky1992), which argued that modern capitalism is essentially financial in character, and will move through a cycle from robustness, to fragility, to crisis and thence debt deflation.

One such perspective focuses on the role and level of private debt – both in causing the GFC but also in the world's persistent post-crisis woes. Jaworski and Weber (Reference Jaworski and Weber2011) suggest that long-term current account deficits and excessive private credit availability led to overconsumption above levels sustainable by national economies in the rich world. As privately held debt has continued to increase since the GFC, they argue that further debt-financed stimulus cannot possibly deliver a sustainable solution. Buttiglione et al. (Reference Buttiglione, Lane, Reichlin and Reinhart2014), Keen (Reference Keen2015) and Wolf (Reference Wolf2014) highlight the absence of real private deleveraging since the GFC, and argue that the bubble risk posed by excessively high private indebtedness has grown rather than receded since the crisis. Streeck (Reference Streeck2016: 67) describes this interaction of low growth with risks and fragility as leading to an outlook of ‘stagnation with a chance of bubbles’.

A parallel perspective focuses on the potentially malignant influence of increasing financialisation on the real economy. This approach provides research indicating that ‘financial depth’ (i.e. the scale of credit and the finance sector) starts to have a negative impact on output growth above certain levels (Cecchetti and Kharroubi, Reference Cecchetti and Kharroubi2012; Arcand et al., Reference Arcand, Berkes and Panizza2015). Sahay et al. (Reference Sahay, Čihák, N'Diaye, Barajas, Bi, Ayala, Gao, Kyobe, Nguyen, Saborowski, Svirydzenka and Yousefi2015) show that excessively fast and poorly regulated financial deepening has led to economic and financial instability. Not only does continuing failure to rein in financialisation potentially risk greater volatility in the future, it leads to an excessive focus on financial profits. Financial profits increasingly represent rents and rent-seeking activity, at the expense of productive investment and activity, hence reducing economic growth (Bezemer and Hudson, Reference Bezemer and Hudson2016; Standing, Reference Standing2016).

4.4 Unequal growth

In recent years, significant methodological and data advances have been made in the field of estimating income and wealth inequality, both within and between nations. These studies (e.g. Ostry et al., Reference Ostry, Berg and Tsangarides2014; Piketty and Saez, Reference Piketty and Saez2014; Milanovic, Reference Milanovic2016) have told a striking and consistent story, beginning with a convergence of incomes and wealth from extremes of inequality in the pre-First World War period, to a ‘golden age’ of greatly reduced inequality and increasing middle and working class prosperity (in the developed countries, at least) in the post-Second World War period. From the 1970s onwards, income and wealth inequality grew once again, with ‘top’ incomes growing rapidly while much of the population of developed countries have faced stagnant real incomes. While inequality between countries has reduced significantly during this latter period (and the proportion of the world's population living in absolute poverty has declined greatly), there is much less evidence of any reduction in inequality within nations, whether rich or poor (Ravallion, Reference Ravallion2014; Milanovic, Reference Milanovic2016).

4.5 Undesirable and unsustainable growth

Thus far, this paper has not queried the desirability of GDP growth. A significant literature has conventionally used GDP as a proxy for overall societal welfare and wealth (see Coyle, Reference Coyle2014). Yet it has long been recognised that many costs which are clearly undesirable ‘bads’ are all counted as positive increments to GDP (Mishan, Reference Mishan1967). At the same time, great swathes of the essential but unmarketed work of survival, nurture and caring undertaken by humans (and especially the work of women) are excluded from this measure (Waring, Reference Waring1988; Stiglitz et al., Reference Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi2010). Drawing on substantial, if contested, empirical research (Easterlin, Reference Easterlin2001; Beja, Reference Beja2014), it has been argued that, above surprisingly modest levels of income and GDP, additional income and consumption provide very slim gains in well-being and happiness (Oswald, Reference Oswald1997, Reference Oswald, Southerton and Ulph2014; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Frijters and Shields2008).

This evidence has led many of these authors (e.g. Oswald, Reference Oswald1997; Stiglitz et al., Reference Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi2010) to question why GDP growth maximisation should enjoy its apparent status as the preeminent goal of economic policy. These critiques of the limits of GDP as both measure and goal of economic policy are uncontroversial and supported by many governments. They are made explicit in the deliberate choice that makes ‘economic growth’ only a partial component of one of the seventeen United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Thus Goal 8 is to ‘promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all’ (UN, 2015), making GDP merely a means, not an end of policy.

A second line of argument questioning the desirability of unfettered GDP growth centres on persistent concerns that human activity (for which GDP does represent a plausible proxy) is in fact consuming and polluting the natural world at a faster rate than it can regenerate, with potentially negative consequences for humanity (Meadows et al., Reference Meadows, Meadows, Randers and Behrens1972; Rockstrom et al., Reference Rockstrom, Steffen, Noone, Persson, Chapin and Lambin2009; Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Richardson, Rockstrom, Cornell, Fetzer, Bennett, Biggs, Carpenter, de Vries, de Wit, Folke, Gerten, Heinke, Mace, Persson, Ramanathan, Reyers and Sorlin2015). These impacts include not only atmospheric CO2 pollution, but also depletion of natural resources (from potentially renewable fisheries to non-renewable fossil fuel and mineral deposits), and the destruction of natural habitats and ecosystems, with alarming losses in biodiversity and consequent risks to humanity's future access to essential ecosystem services (IPBES, 2019).

Economists such as Arrow et al. (Reference Arrow, Bolin, Costanza, Dasgupta, Folk, Holling, Jansson, Levin, Maler, Perrings and Pimentel1995), Arrow et al. (Reference Arrow, Dasgupta, Goulder, Daily, Ehrlich, Heal, Levin, Maler, Schneider, Starrett and Walker2004) and Dasgupta (Reference Dasgupta, Southerton and Ulph2014) have tentatively concluded that human society (at least in the developed countries) is consuming more resources than can be sustained, or indeed than may be consistent with optimal human welfare. Daly (Reference Daly and Daly2007) has suggested that economic growth has already become ‘uneconomic’ growth, as it not only causes increasing damage to the natural environment, but has passed the point of diminishing marginal benefits to society.

One response to this problem, broadly adopted across many international development and economic agencies, is to advocate for what has come to be known as ‘green growth’. ‘Green growth’ can be characterised as a strategy by which economic activity continues to increase over time, but in a way which does not reduce aggregate natural capital (Bowen and Hepburn, Reference Bowen and Hepburn2014), by ensuring that economic growth does not unsustainably deplete non-renewable natural resources or unsustainably pollute natural sinks. To achieve this aim, ‘green growth’ requires GDP growth to achieve an absolute decoupling from pollution (especially but not exclusively CO2 emissions) and resource depletion. Whether absolute decoupling is technically or practically possible remains highly contested (Smulders et al., Reference Smulders, Toman and Withagen2014; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Sutton, Warner, Costanza, Mohr and Simmons2016; Hickel and Kallis, Reference Hickel and Kallis2019).

Meanwhile, ecological economists have examined ‘post-growth’ options for a steady state economy (Daly, Reference Daly1977) or ‘agrowth’ economics (van den Bergh, Reference van den Bergh2017) – in which the objective of economic policy ceases to be GDP growth, but instead seeks to maximise human welfare within a sustainable and strictly limited level of material consumption and pollution of the Earth's natural resources – generally allowing for the necessity of continued (albeit much more carefully directed) catch-up growth in the developing countries (Daly, Reference Daly1977; Booth, Reference Booth1994; Victor and Rosenbluth, Reference Victor and Rosenbluth2007; Lawn, Reference Lawn2010, Reference Lawn, Costanza, Limburg and Kubiszewski2011; Raworth, Reference Raworth2017; van den Bergh, Reference van den Bergh2017).

Others have gone further than the ‘steady state’ proposition, by arguing that a preliminary period of ‘degrowth’ (i.e. the deliberate and active reduction of consumption levels, rather than just limits on their growth) is necessary prior to stabilising the economy at a steady state equilibrium (Kallis, Reference Kallis2011; Kallis et al., Reference Kallis, Kerschner and Martinez-Alier2012). Not surprisingly, the degrowth perspective remains controversial even amongst those who broadly advocate for a steady state economy, with considerable uncertainty as to how such a policy objective could be realised without itself precipitating major financial and economic crises (Klitgaard and Krall, Reference Klitgaard and Krall2012; Tokic, Reference Tokic2012). While voluntary degrowth may be unlikely to be socially or politically palatable, others note that involuntary degrowth (otherwise known as collapse) always remains a possible outcome of ecological overshoot (Bonaiuti, Reference Bonaiuti2017).

4.6 Shorter-term prospects

The preceding review of the literature on economic growth prospects in the post-GFC era has identified strong arguments from very different premises which support the notion that long-run growth rates – especially but by no means only in the high-income countries – are likely to continue their secular decline. Ultimately, only long-run data can support or disprove the thesis that long-run economic growth rates are falling. Yet it is unwise to assume that long-run trends cannot be bucked temporarily or locally. Over the last year, some countries have experienced growth rates above those that have prevailed for many years. Yet the International Monetary Fund appears convinced by the secular stagnation thesis. Their latest outlook (IMF, 2019) showed slowing economic growth in most of the world, including China and Europe. Recent high quarterly growth in the US economy (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2019) has generated divergent media commentary, and is not reflected in most other countries. Real concerns remain as to how central banks' unwinding of their extraordinary quantitative easing policies might impact on the real economy. Increasing interest rates, combined with historically high levels of private indebtedness, could prove highly problematic for businesses and households alike. Indeed – despite recent GDP growth and employment figures – the US Federal Reserve has recently paused its planned programme of interest rate rises (US Federal Reserve, 2019).

Meanwhile, major recent reports by UN-auspiced bodies have pointed out in increasingly stark terms the need for urgent and dramatic changes to meet environmental challenges. In October 2018, the IPCC reported that current international commitments to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions under the Paris Agreement will not limit global warning to 1.5°C, and that global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions must be reduced by 45% from their 2010 levels by 2030 if this goal is to be achieved – requiring a step-change in emissions reduction efforts globally (IPCC, 2018). The latest global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services makes a similarly blunt assessment on the urgency of reducing humanity's wider impacts on the natural world, stating:

‘Goals for conserving and sustainably using nature and achieving sustainability cannot be met by current trajectories, and goals for 2030 and beyond may only be achieved through transformative changes across economic, social, political and technological factors’. (IPBES, 2019)

5. Discussion: implications for health care policy

5.1 Health care and current macroeconomic debates

This discussion of future scenarios for economic growth has necessarily been brief, and therefore unavoidably risks criticism for being too broad in scope. Yet this review has identified a number of substantial debates on the future of economic growth, and has found little evidence that other researchers have yet attempted to assess, still less integrate, their implications for health care policy. Health care systems and health economists have not engaged directly with the debate on secular stagnation, low growth or sustainable post-growth in recent years. They have confined their attention to managing or researching the direct impacts of economic crisis, rather than considering the possibility of a state change having occurred. Health care policy-makers, planners and regulators need to readjust their assumptions and expectations to reflect a low or post-growth world as a plausible future for the developed countries, if not the whole globe. This may challenge long-dominant assumptions.

What is perhaps most striking in the literature is the absence of any real sense that economic growth will return to some pre-crisis ‘normal’ (Jackson, Reference Jackson2019). Instead, the future possibilities seem complex and their implications are challenging. It is particularly important not to cherry pick only the positives from the scenarios under consideration. Getzen's (Reference Getzen and Scheffler2016) observations on the historical trajectory of health care expenditure provide an appropriate starting point for this discussion. He argues that growth in health expenditure was low until GDP growth took off in the post-WW2 ‘golden age’; and now that GDP growth has slowed, so too has growth in health expenditure. Getzen notes that a pronounced slowdown in the growth of the health care share of GDP is already clearly apparent in the developed countries (Figure 3). He also notes that demographics and ageing (one of Gordon's ‘headwinds’) are essentially an unavoidable pressure on health systems, even if they have proved historically to be only a minor driver of increasing health care costs.

Scenarios of demand-side secular stagnation (Eichengreen, Reference Eichengreen2015; Summers, Reference Summers2015) can have some quite surprising implications for health care and health financing policy in both developed and emerging economies. Teulings and Baldwin (Reference Teulings and Baldwin2014) argue that the need to reduce savings rates under secular stagnation logically entails increasing the role of pay as you go (PAYG) public pension and health care insurance systems, as self-funded systems have contributed to current savings gluts. Building credible PAYG systems is, they argue, the best way to minimise excess precautionary savings. Rachel and Summers (Reference Rachel and Summers2019) argue that high government debt and deficits, PAYG pensions and government-funded health care insurance have been the key mechanisms keeping real interest rates from falling into even more deeply negative territory in recent years. If correct, this could have profound implications for the optimal future balance between different sources of health financing.

The evidence of the GFC does seem to have confirmed the Keynesian wisdom of how to stop a crisis or recession from becoming a depression (and exposed again the self-defeating outcomes of austerity economics). The economic crises suffered by some Eurozone countries (most notably Greece) since the GFC, and earlier crises such as the fall of the Soviet Union, have provided clear evidence on the extremely negative impacts of ‘austerity’ on publicly funded health care systems (Kentikelenis and Papanicolas, Reference Kentikelenis and Papanicolas2012; Stuckler and Basu, Reference Stuckler and Basu2013; Tyrovolas et al., Reference Tyrovolas, Kassebaum, Stergachis, Abraha, Alla, Androudi, Car, Chrepa, Fullman, Fürst, Haro, Hay, Jakovljevic, Jonas, Khalil, Kopec, Manguerra, Martopullo, Mokdad, Monasta, Nichols, Olsen, Rawaf, Reiner, Renzaho, Ronfani, Sanchez-Niño, Sartorius, Silveira, Stathopoulou, Stein Vollset, Stroumpoulis, Sawhney, Topor-Madry, Topouzis, Tortajada-Girbés, Tsilimbaris, Tsilimparis, Valsamidis, van Boven, Violante, Werdecker, Westerman, Whiteford, Wolfe, Younis and Kotsakis2018).

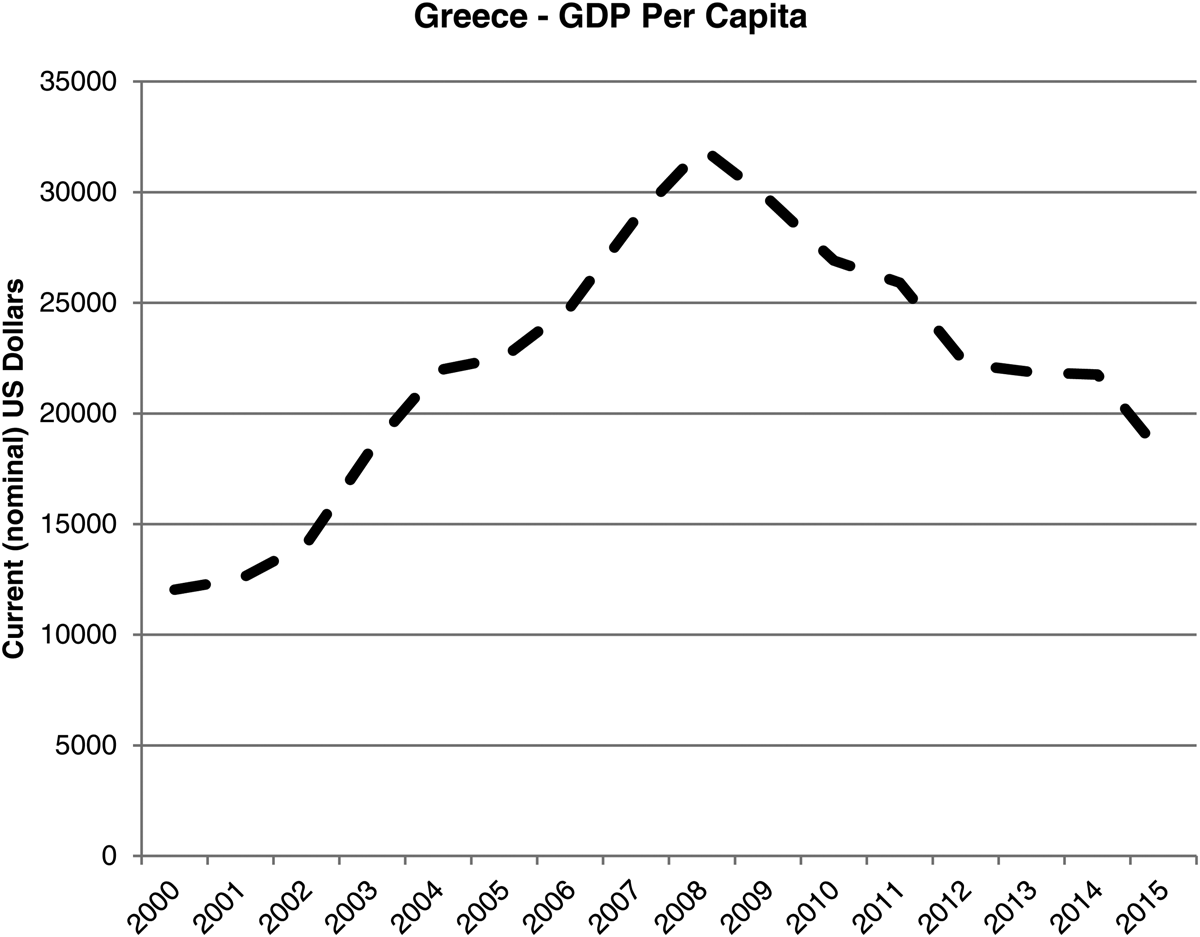

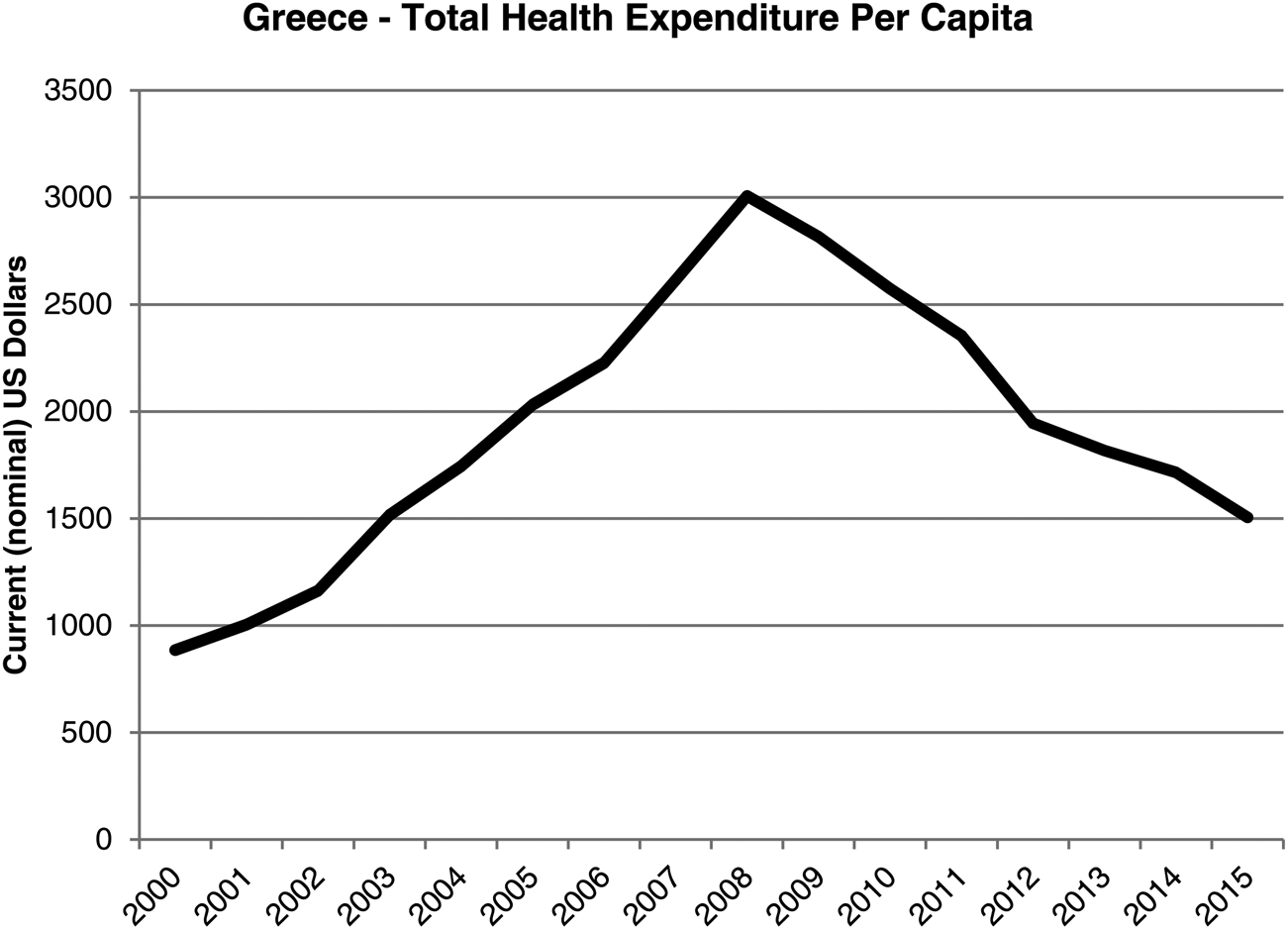

Figures 4 and 5 show the magnitude of the GDP contraction that afflicted Greece in the years after the GFC, and the even greater reduction in health expenditure per capita that accompanied the austerity policies of that period. Between 2008 and 2015, nominal Greek GDP per capita (expressed at market exchange rates in US dollar terms) contracted by some 44%. Meanwhile total health expenditure per person fell by almost exactly 50%, from $3007 per capita in 2008 to $1505 in 2015.

Figure 4. Greece – per capita GDP, current US$.

Figure 5. Greece – total health expenditure, current US$.

The implications for health care of the case that austerity is self-defeating are perhaps the easiest to summarise of all the scenarios under consideration. Conventional policy prescriptions for health care systems facing fiscal austerity have tended to exhort ever-greater ‘efficiency’, and have appealed to shift health care spending away from public and towards private sources (e.g. Saltman and Cahn, Reference Saltman and Cahn2013). Post-Keynesian and MMT critiques of observed policy responses suggest that, under recessionary or contractionary conditions, not only will public spending cuts damage health, but that this reduced public spending on health will impact negatively on aggregate demand and economic recovery. In systems in which private financing plays a significant role, these approaches suggest that, under low or negative growth conditions, household incomes will be suppressed, reducing their capability to finance needed health care or private health insurance. A parallel policy of austerity in the public health system will therefore make a bad health financing situation even worse than it needs to be, and will worsen inequities in health and health care, while also potentially undermining growth and recovery. Given this, it becomes quite hard to mount a convincing argument that austerity is defensible on pragmatic grounds, let alone that it is ethically defensible from the perspectives of justice and fairness. The sheer scale of reductions in Greek health expenditure should also serve as a warning that apparently inconceivable economic reversals still can and do happen, even in high-income countries – and that health care systems will never be immune in times of economic crisis. Recent experience shows clearly the damage that austerity policies are likely to have on health care systems, and health economists might reasonably make the case that austerity policies represent a substantial misallocation of resources pushing systems and societies away from allocative efficiency.

5.2 Health care, financialisation and rent-seeking

Evidence on the importance of financialisation and rent-seeking in health care has grown significantly in recent years. Bezemer and Hudson (Reference Bezemer and Hudson2016) explicitly highlight health insurance as a significant area of attractive potential rent-seeking activity, due to its highly regulated nature and tendency to attract various forms of public subsidy. Their critique of rent-seeking behaviour in private health insurance – and its wider consequences for both health care and the economy – has certainly been echoed outside academic discourse, both in the United States (Robb, Reference Robb2017) and in Australia (Sainsbury, Reference Sainsbury2016). Similar arguments have been made concerning the pharmaceutical industry (Mazzucato, Reference Mazzucato2013). Pharmaceutical companies make extremely high profits when compared with other sectors, in part because their real research and development costs are lower than generally believed (Prasad and Mailankody, Reference Prasad and Mailankody2017). Researchers (Bessen, Reference Bessen2009; Spitz and Wickham, Reference Spitz and Wickham2012) found strong evidence for the existence of pharmaceutical rents leading to supra-normal profits, and that the rents enjoyed by big pharma are an order of magnitude larger than those in other industries. In the United States at least, it is certainly the case that the health care industry in general, and pharmaceutical and device manufacturers in particular, spends large sums on political contributions. In 2018, the pharmaceutical industry spent $281.8 million on lobbying, roughly as much as hospitals, nursing homes, health professionals and health services/Health Maintenance Organizations combined; overall, the health sector as a whole spent nearly $563 million on lobbying efforts that year (CRP, 2019). Public choice theory would explain this expenditure as a rational and highly cost-effective effort to protect these valuable economic rents.

Meanwhile, Baranes (Reference Baranes2017) finds direct evidence of the increasing financialisation of the US pharmaceutical industry over time, showing that the industry has come to rely ever more heavily on profits from intangible assets rather than from production and sales. Yet proposals exist that explicitly promote further financialisation of health care funding, for example in the call to establish a market for securitised health care loans to allow US patients to purchase very high-cost curative therapies (Montazerhodjat et al., Reference Montazerhodjat, Weinstock and Lo2016).

Mazzucato (Reference Mazzucato2013) argues that the evolution of the pharmaceutical industry has reflected the logic of financially driven rent-seeking. She suggests this is best exemplified in pharmaceutical firms extracting economic rents from original research and innovation that was largely funded by the state, and failing to deliver innovative drugs in markets where revenues (or rents) are limited. The most notable example of the latter phenomenon is the antibiotic ‘discovery void’ (WHO, 2014), and the progressive abandonment of research into novel antibiotics by major pharmaceutical companies. Substantial efforts have been devoted to developing often complex public–private partnership solutions for encouraging antibiotic development. Yet these attempts have failed to deliver meaningful progress, so much so that one of their leading proponents has recently declared that the failure of the antibiotics market is so profound that nationalised or publicly owned pharmaceutical firms may now be the only option able to deliver success in this area (Andalo, Reference Andalo2019). Baker et al. (Reference Baker, Jayadev and Stiglitz2017) have recently called for substantial changes to the international intellectual property rights regime, arguing that it has failed to deliver innovation in a way that improves welfare, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Meanwhile, new approaches, such as the ‘knowledge commons’ and open source movements (Raworth, Reference Raworth2017) might, with appropriate nurturing and partnering by the state, begin to provide viable alternatives to the traditional for-profit innovation model; others (e.g. Gaffney, Reference Gaffney2018) suggest tackling the problem of patent monopoly rents and financialisation by separating the processes of drug discovery and evaluation from manufacture, and providing direct public funding for the former. Beyond pharma, there are strong suggestions that US health care providers increasingly display evidence of financialisation and that they may have been able to use their ‘non-profit’ status in ways that assist in the capture of economic rents (Rosenthal, Reference Rosenthal2017). Meanwhile, Mazzucato (Reference Mazzucato2018) argues that the systematic extension of outsourcing of services to private providers and of the Private Financing Initiative in the British National Health Service (and elsewhere) has created new frontiers for rent-seeking for a select group of large generic outsourcing firms.

There appears to be little published research on regulatory capture in health care, although some exists in adjacent sectors such as nursing home care (e.g. Makkai and Braithwaite, Reference Makkai and Braithwaite2008). Yet concerns are persistently raised concerning the clear risks of regulatory capture in health care systems, especially in the area of pharmaceutical and devices approval and regulation by agencies such as the FDA, MHRA and TGA (e.g. Moynihan, Reference Moynihan2002; Furberg et al., Reference Furberg, Levin, Gross, Shapiro and Strom2006), and even in areas such as the development of clinical guidelines (Welch, Reference Welch2017).

Beyond regulatory capture and rent-seeking lies an even starker problem which has become especially manifest in the US health care system in recent years: illegal behaviour, bribery and fraud on striking scales, sometimes with very direct adverse impacts on health. The US opioid epidemic has thrown up a string of successful lawsuits and convictions against pharmaceutical manufacturers for their practices which drove the evolution of this lethal iatrogenic epidemic (e.g. USDC, 2007, McGreal, Reference McGreal2019) – although bribery and collusion between drug companies and doctors by no means appears to have been confined to opioids (e.g. Dyer, Reference Dyer2019).

This discussion raises difficult questions about the sustainability of current models of health technology innovation. The conventional wisdom that brackets profit-driven innovation with economic growth may not only conflate micro (profits) and macro (GDP growth) factors and confuse them with welfare; it may simply fail to deliver welfare-improving innovation in a low or post-growth future. Action to improve public value by driving down rent-seeking, financialisation and law-breaking may require significant rethinking of the current default model of innovation and intellectual property in the pharmaceutical and other health technology industries, especially if more concerted action is to be taken to drive down overutilisation and inappropriate use (see below for further discussion). The institutional role and relationships of health economics and health economists within health technology assessment (HTA) ecosystems may need careful review, and strong safeguards developed to defend against regulatory capture. Meanwhile, growing calls for states to regulate more confidently in the public interest (Mitchell and Fazi, Reference Mitchell and Fazi2017; Mazzucato, Reference Mazzucato2018) are likely to be reprised in the health sector before long. Health economists need to be ready to contribute with imagination and originality to the design of new regulatory approaches which prioritise public value over industry returns. The discipline is, in fact, well placed to contribute new approaches to conceiving and safeguarding this ‘public value’ (Mazzucato, Reference Mazzucato2018), but greater collaboration with institutional economists and specialists in regulatory policy and law are likely to be required to strengthen the traditional toolkit of health economics.

5.3 Health care and economic inequality

Consideration of how recent trends in ‘unequal growth’ might impact on health care in the future requires consideration of the two key types of income and wealth inequality, inequality between nations, and inequality within nations. There has been clear evidence of reduced income inequality between nations (Milanovic, Reference Milanovic2016). The long-term relationship between health and GDP summarised earlier would logically suggest that, over time, reduced disparities in GDP per capita between nations should also manifest in reduced disparities in health expenditure per capita. Indeed, this convergence has been called for as a crucial aim of global policy (Jamison et al., Reference Jamison, Summers, Alleyne, Arrow, Berkley, Binagwaho, Bustreo, Evans, Feachem, Frenk, Ghosh, Goldie, Guo, Gupta, Horton, Kruk, Mahmoud, Mohohlo, Ncube, Pablos-Mendez, Reddy, Saxenian, Soucat, Ultveit-Moe and Yamey2013). Yet recent modelling (Dieleman et al., Reference Dieleman, Templin, Sadat, Reidy, Chapin, Foreman, Haakenstad, Evans, Murray and Kurowski2016; Dieleman et al., Reference Dieleman, Campbell, Chapin, Eldrenkamp, Fan, Haakenstad, Kates, Li, Matyasz, Micah, Reynolds, Sadat, Schneider, Sorensen, Abbas, Abera, Kiadaliri, Ahmed, Alam, Alizadeh-Navaei, Alkerwi, Amini, Ammar, Antonio, Atey, Avila-Burgos, Awasthi, Barac, Berheto, Beyene, Beyene, Birungi, Bizuayehu, Breitborde, Cahuana-Hurtado, Castro, Catalia-Lopez, Dalal, Dandona, Dandona, Dharmaratne, Dubey, Faro, Feigl, Fischer, Fitchett, Foigt, Giref, Gupta, Hamidi, Harb, Hay, Hendrie, Horino, Jürisson, Jakovljevic, Javanbakht, John, Jonas, Karimi, Khang, Khubchandani, Kim, Kinge, Krohn, Kumar, Leung, El Razek, El Razek, Majeed, Malekzadeh, Malta, Meretoja, Miller, Mirrakhimov, Mohammed, Molla, Nangia, Olgiati, Owolabi, Patel, Caicedo, Pereira, Perelman, Polinder, Rafay, Rahimi-Movaghar, Rai, Ram, Ranabhat, Roba, Savic, Sepanlou, Ao, Tesema, Thomson, Tobe-Gai, Topor-Madry, Undurraga, Vargas, Vasankari, Violante, Wijeratne, Xu, Yonemoto, Younis, Yu, Zaidi, El Sayed Zaki and Murray2017a, Reference Dieleman, Campbell, Chapin, Eldrenkamp, Fan, Haakenstad, Kates, Liu, Matyasz, Micah, Reynolds, Sadat, Schneider, Sorensen, Evans, Evans, Kurowski, Tandon, Abbas, Abera, Kiadaliri, Ahmed, Ahmed, Alam, Alizadeh-Navaei, Alkerwi, Amini, Ammar, Amrock, Antonio, Atey, Avila-Burgos, Awasthi, Barac, Bernal, Beyene, Beyene, Birungi, Bizuayehu, Breitborde, Cahuana-Hurtado, Castro, Catalia-Lopez, Dalal, Dandona, Dandona, de Jager, Dharmaratne, Dubey, Farinha, Faro, Feigl, Fischer, Fitchett, Foigt, Giref, Gupta, Hamidi, Harb, Hay, Hendrie, Horino, Jürisson, Jakovljevic, Javanbakht, John, Jonas, Karimi, Khang, Khubchandani, Kim, Kinge, Krohn, Kumar, El Razek, El Razek, Majeed, Malekzadeh, Masiye, Meier, Meretoja, Miller, Mirrakhimov, Mohammed, Nangia, Olgiati, Osman, Owolabi, Patel, Caicedo, Pereira, Perelman, Polinder, Rafay, Rahimi-Movaghar, Rai, Ram, Ranabhat, Roba, Salama, Savic, Sepanlou, Shrime, Talongwa, Ao, Tediosi, Tesema, Thomson, Tobe-Gai, Topor-Madry, Undurraga, Vasankari, Violante, Werdecker, Wijeratne, Xu, Yonemoto, Younis, Yu, Zaidi, El Sayed Zaki and Murray2017b) has questioned not only whether there is much sign of any such convergence in health spending to date, but also whether there is any real prospect of health spending in low-income countries increasing at the rates required in coming decades without significant changes in policy direction and global development assistance. IMF (2018) has recently expressed concern that it expects one-quarter of emerging market and developing economies to grow slower than the advanced economies over the next 5 years. Indeed, Milanovic (Reference Milanovic2016) notes that the gains from growth (and hence progress in reducing inter-country inequality) have overwhelmingly been reaped by Asian nations. Most African nations continue to experience slower growth than the high-income nations, such that the ongoing impacts of low growth remains a key barrier to improving health and health care on that continent. Benatar (Reference Benatar2016) suggests that significant progress in this regard is almost inconceivable within current social and economic belief systems; only if we can overcome what he describes as our ‘lack of moral imagination’ can there be any realistic prospect of developing meaningful technical strategies to achieve convergence in health spending.

Dieleman et al. (Reference Dieleman, Campbell, Chapin, Eldrenkamp, Fan, Haakenstad, Kates, Li, Matyasz, Micah, Reynolds, Sadat, Schneider, Sorensen, Abbas, Abera, Kiadaliri, Ahmed, Alam, Alizadeh-Navaei, Alkerwi, Amini, Ammar, Antonio, Atey, Avila-Burgos, Awasthi, Barac, Berheto, Beyene, Beyene, Birungi, Bizuayehu, Breitborde, Cahuana-Hurtado, Castro, Catalia-Lopez, Dalal, Dandona, Dandona, Dharmaratne, Dubey, Faro, Feigl, Fischer, Fitchett, Foigt, Giref, Gupta, Hamidi, Harb, Hay, Hendrie, Horino, Jürisson, Jakovljevic, Javanbakht, John, Jonas, Karimi, Khang, Khubchandani, Kim, Kinge, Krohn, Kumar, Leung, El Razek, El Razek, Majeed, Malekzadeh, Malta, Meretoja, Miller, Mirrakhimov, Mohammed, Molla, Nangia, Olgiati, Owolabi, Patel, Caicedo, Pereira, Perelman, Polinder, Rafay, Rahimi-Movaghar, Rai, Ram, Ranabhat, Roba, Savic, Sepanlou, Ao, Tesema, Thomson, Tobe-Gai, Topor-Madry, Undurraga, Vargas, Vasankari, Violante, Wijeratne, Xu, Yonemoto, Younis, Yu, Zaidi, El Sayed Zaki and Murray2017a, Reference Dieleman, Campbell, Chapin, Eldrenkamp, Fan, Haakenstad, Kates, Liu, Matyasz, Micah, Reynolds, Sadat, Schneider, Sorensen, Evans, Evans, Kurowski, Tandon, Abbas, Abera, Kiadaliri, Ahmed, Ahmed, Alam, Alizadeh-Navaei, Alkerwi, Amini, Ammar, Amrock, Antonio, Atey, Avila-Burgos, Awasthi, Barac, Bernal, Beyene, Beyene, Birungi, Bizuayehu, Breitborde, Cahuana-Hurtado, Castro, Catalia-Lopez, Dalal, Dandona, Dandona, de Jager, Dharmaratne, Dubey, Farinha, Faro, Feigl, Fischer, Fitchett, Foigt, Giref, Gupta, Hamidi, Harb, Hay, Hendrie, Horino, Jürisson, Jakovljevic, Javanbakht, John, Jonas, Karimi, Khang, Khubchandani, Kim, Kinge, Krohn, Kumar, El Razek, El Razek, Majeed, Malekzadeh, Masiye, Meier, Meretoja, Miller, Mirrakhimov, Mohammed, Nangia, Olgiati, Osman, Owolabi, Patel, Caicedo, Pereira, Perelman, Polinder, Rafay, Rahimi-Movaghar, Rai, Ram, Ranabhat, Roba, Salama, Savic, Sepanlou, Shrime, Talongwa, Ao, Tediosi, Tesema, Thomson, Tobe-Gai, Topor-Madry, Undurraga, Vasankari, Violante, Werdecker, Wijeratne, Xu, Yonemoto, Younis, Yu, Zaidi, El Sayed Zaki and Murray2017b) suggest two important conclusions of relevance here. They demonstrate that the share of out of pocket expenditures on health care is highest in the very poorest nations, and that their importance declines in nations with higher GDP. Second, they illustrate the surprisingly small role played globally by private health insurance (‘prepaid private spending’) as a share of total health expenditure even at higher levels of GDP. Their analysis makes it clear that, at a global level, government health spending is the engine of strong health care systems. Combined with the critique of rent-seeking by health insurers through regulation and subsidy, this might lead us to be rather sceptical about the role of private health insurance in a lower growth future, where every marginal health dollar will have to count for more. Indeed, it reinforces recent recognition that significantly increased government expenditure on health care is essential if the goal of universal health coverage is to stand any chance of being achieved in low and middle income countries (e.g. McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Meheus and Røttingen2017).

Within nations, the impact of future trends in income and wealth inequality is certainly not easy to predict. In the absence of any turn towards greater redistribution, Cowen (Reference Cowen2013) suggests that significantly increasing disparities in access to health care will be inevitable, presenting a libertarian vision in which reduced health care cover for the poor may simply come to be accepted as a necessary part of adapting to endemic inequality. Alternatively, societies and governments might see maintaining or improving equitable access to health care as an important component of strategies to improve justice and distributive fairness, as part of a ‘social wage’ (Schofield, Reference Schofield2000). If societies and governments move directly to reduce current inequalities in income, impacts on the health care sector might well include increasing roles for tax-funded health care or social health insurance (with universal health care frequently appearing on the same platform as calls for a basic income guarantee). This would most likely be accompanied by diminished roles for voluntary private health insurance and regressive out of pocket payments, including informal ‘under the table’ payments (Lewis, Reference Lewis2007). It is important to note that reducing income inequality may have implications for medical incomes in particular, with doctors typically one of the highest paid professions in most societies.

5.4 Health care and overconsumption

Meanwhile, even if post-Keynesian macroeconomics now offers the most realistic models of the behaviour of current capitalist economies, this in no way guarantees that their policy prescriptions do not conflict with ecological constraints and planetary boundaries. A significant public health literature has emerged in recognition of the potentially profound impacts of climate change (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Abbas, Allen, Ball, Bell, Bellamy, Friel, Groce, Johnson, Kett, Lee, Levy, Maslin, McCoy, McGuire, Montgomery, Napier, Pagel, Patel, de Oliveira, Redclift, Rees, Rogger, Scott, Stephenson, Twigg, Wolff and Patterson2009; Watts et al., Reference Watts, Adger, Agnolucci, Blackstock, Byass, Cai, Chaytor, Colbourn, Collins, Cooper, Cox, Depledge, Drummond, Ekins, Galaz, Grace, Graham, Grubb, Haines, Hamilton, Hunter, Jiang, Li, Kelman, Liang, Lott, Lowe, Luo, Mace, Maslin, Nilsson, Oreszczyn, Pye, Quinn, Svensdotter, Venevsky, Warner, Xu, Yang, Yin, Yu, Zhang, Gong, Montgomery and Costello2015). A related ‘planetary health’ movement is starting to extend this analysis to incorporate other planetary boundaries (Whitmee et al., Reference Whitmee, Haines, Beyrer, Boltz, Capon, Ferreira de Souza Dias, F Ezeh, Frumkin, Gong, Head, Horton, Mace, Marten, Myers, Nishtar, Osofsky, Pattanayak, Pongsiri, Romanelli, Soucat, Vega and Yach2015). The beginnings of a literature dealing more explicitly with sustainable health care are apparent (Pencheon, Reference Pencheon2013), as are estimates of the aggregate contribution of health care systems to GHG emissions – for example, health care generates some 7% of national GHG emissions in Australia and 10% in the United States (Eckelman and Sherman, Reference Eckelman and Sherman2016; Malik et al., Reference Malik, Lenzen, McAlister and McGain2018).

Low or constrained growth, coupled with ecological constraints, makes it even more pressing that health care systems confront the reality that more health care is not necessarily better health care (Saini et al., Reference Saini, Brownlee, Elshaug, Glasziou and Heath2017). Strong evidence now exists of pervasive overuse of health care across the world (Brownlee et al., Reference Brownlee, Chalkidou, Doust, Elshaug, Glasziou, Heath, Nagpal, Saini, Srivastava, Chalmers and Korenstein2017; OECD, 2017). While quantified estimates of the scale of this problem are still emerging, currently available studies suggest that between 10 and 30% of all care currently provided may constitute overuse globally (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Brownlee, Leppin, Kressin, Dhruva, Levin, Landon, Zezza, Schmidt, Saini and Elshaug2015). Meanwhile, estimates of all forms of ‘waste’ in health care systems (not just overuse) generate similarly large numbers – perhaps 20% of all health spending in OECD countries represents waste (OECD, 2017), while the overall cost of waste in the US health care system could be within the range of 21–47% of total health spending (Berwick and Hackbarth, Reference Berwick and Hackbarth2012). Overtreatment, overdiagnosis and waste in health care represent not only potential harm to patients and inefficiency for health systems, but also a form of ecologically damaging overconsumption (Hensher et al., Reference Hensher, Tisdell and Zimitat2017). It is important to understand a crucial implication of this conclusion: trying to use health care as a tool to maintain or stimulate aggregate demand may (at least in the global North) therefore risk undermining welfare in the pursuit of growth – by inadvertently expanding low value or even harmful care. Conversely, in the poorest countries, expanding access to basic health care is likely both to drive significant welfare gains and GDP growth.

6. Conclusions

6.1 Growth, health care and human welfare

GDP growth has been the de facto overarching goal of economic policy in high- and low-income countries since the end of the Second World War. Implicitly or explicitly, it has been assumed that GDP growth is essential for increasing the welfare of society and its members, either directly or as the lubricant that avoids the need for radical redistribution of resources. Yet the evidence reviewed above shows clearly that GDP growth also brings with it welfare-reducing ‘bads’, especially in the ever more visible form of global environmental destruction; and that, above a certain level, a broad range of indicators of human well-being no longer appear to increase even as GDP continues to grow. It is perhaps unsurprising to find that growth in health care consumption displays some similar characteristics to growth in GDP. Most crucially, health care consumption demonstrably contributes to environmental damage via GHG emissions and a range of other pollutants; and a significant portion of health care output and consumption is either of little or no value, or is positively harmful to patients. In other words, not all health care is welfare-enhancing, and some is already welfare-destroying – just like the rest of the economy. However central GDP and growth might be to conventional economic thinking, there is no valid argument against the proposition that growth is simply a means to the ultimate end of improving human welfare. Whether GDP growth is fast, slow or absent, it is only of value if it genuinely improves welfare. Therefore it is with health care output and expenditure: more health care is only of value if it improves human welfare; if it undermines welfare, then it is not of value.

There is growing appreciation of the mechanisms by which patterns of increasing consumption of many products are harming human health and are heavily implicated in global epidemics and syndemics of non-communicable diseases (Freudenberg, Reference Freudenberg2014; Landrigan et al., Reference Landrigan, Fuller, Acosta, Adeyi, Arnold, Basu, Baldé, Bertollini, Bose-O'Reilly, Boufford, Breysse, Chiles, Mahidol, Coll-Seck, Cropper, Fobil, Fuster, Greenstone, Haines, Hanrahan, Hunter, Khare, Krupnick, Lanphear, Lohani, Martin, Mathiasen, McTeer, Murray, Ndahimananjara, Perera, Potočnik, Preker, Ramesh, Rockström, Salinas, Samson, Sandilya, Sly, Smith, Steiner, Stewart, Suk, van Schayck, Yadama, Yumkella and Zhong2018; Swinburn et al., Reference Swinburn, Kraak, Allender, Atkins, Baker, Bogard, Brinsden, Calvillo, De Schutter, Devarajan, Ezzati, Friel, Goenka, Hammond, Hastings, Hawkes, Herrero, Hovmand, Howden, Jaacks, Kapetanaki, Kasman, Kuhnlein, Kumanyika, Larijani, Lobstein, Long, Matsudo, Mills, Morgan, Morshed, Nece, Pan, Patterson, Sacks, Shekar, Simmons, Smit, Tootee, Vandevijvere, Waterlander, Wolfenden and Dietz2019). Human health and well-being can only be maximised if future economic growth minimises these harms, even if doing so reduces profits. Health care must also meet the same test – harms must be minimised to the truly unavoidable, and growth in health care at the margin must demonstrably produce greater welfare than would be achieved were the same resources used for other social objectives. More health care is not better, unless it is the ‘right’ care (Saini et al., Reference Saini, Brownlee, Elshaug, Glasziou and Heath2017), and even the right care currently externalises damage to the environment (Pencheon and Dalton, Reference Pencheon, Dalton and Davies2017).

6.2 Value-based care in low-growth or post-growth economies

Under all the low growth or post-growth scenarios discussed above, decision-makers' budget constraints would be stricter and relative scarcity more pronounced than under conditions of more generous economic growth. As a result, health care systems, clinicians, managers and policy-makers will face ever greater pressure to improve technical and allocative efficiency. This will have consequences for the use of economic evaluation in health care, which has, in many countries, become an essential mechanism for determining which interventions should be adopted and funded. To date, there has been little evidence of any effective change in cost-effectiveness thresholds as used in real-world decisions since the GFC (Dakin et al., Reference Dakin, Devlin, Feng, Rice, O'Neill and Parkin2015). In a more economically constrained future, this must eventually change, with significant consequences for HTA. Methods of economic evaluation will need to be developed that overcome the current bias of HTA systems towards patented interventions, to the detriment of non-patentable, community or traditional approaches (Eckerman, Reference Eckerman2017). Current methods of economic evaluation have also proved to be of limited value in identifying and dealing with overdiagnosis and overtreatment; substantial improvements (both conceptual and technical) are essential if value- and welfare-destroying waste and overuse are to be reduced meaningfully. Economic evaluation will also need to become better at assessing care, not just technical interventions, given the increasing recognition that better care is not always synonymous with more technology. Debates on the appropriate balance within health care systems between technological intervention, caring and the reduction of suffering are likely to become more prominent.

Longer term, it is also possible that a deeper ecological constraint on growth may eventually prove incompatible with the ‘extra-welfarist’ perspective embodied by quality adjusted life years (Mooney, Reference Mooney2009). The assumption of a privileged (or, at least, a self-contained) status for health may progressively become untenable, as inter-sectoral welfare trade-offs and environmental costs become more starkly visible. As an absolute minimum, environmental costs and externalities will increasingly need to be built into all forms of the economic evaluation of health care.

6.3 Value-based care and value-based policy

The post-war golden age of rapid economic growth increasingly appears as a brief, if striking, anomaly against the background trend of economic history (Jackson, Reference Jackson2019). Similarly, modern health care systems have existed at scale for less than half of the industrial age, and their period of rapid growth has so far spanned little more than a single human lifetime. This paper has suggested that there are good reasons to consider the possibility that rapid growth will not – or, indeed, should not – return.

Policy responses to the low growth debate – in health care and beyond – seem unavoidably to require a stronger normative element to guide decision making on tough policy decisions and dilemmas. Pretending that these issues can be resolved through purely technical analyses is likely to result only in a continuation of the status quo; and it is perhaps this courage to confront moral choices head on that has been most lacking in economics as a discipline in recent decades (Buarque, Reference Buarque1993; Sedlacek, Reference Sedlacek2013). Critical economic decisions on equity in health care and its relationship to income and wealth inequality, on rent-seeking and monopoly power in health care, and even on overuse can only be solved by combining citizens' social and moral judgements with wise political and professional leadership, and not by an appeal to illusory technical solutions or authority (Earle et al., Reference Earle, Moran and Ward-Perkins2017).

For health systems attempting to deliver value in health care, confronting a low growth or post-growth future offers both opportunities and challenges. The greatest opportunity lies in the central task of recognising and acting upon the increasing evidence that more health care is not always better, either for patients, the population at large, or the planet; and that less is sometimes more when it comes to maximising welfare. A post-growth future also offers many opportunities to reduce the harmful consumption patterns driving many non-communicable diseases in high- and low-income nations alike. Yet there is no escaping the fact that eliminating unnecessary health care will reduce profits and incomes for many actors in the health care market; and that it is the influence and power of these actors over market dynamics, regulation and politics that has too often prevented effective action from occurring in the past. Without economic growth, these tensions are likely to become starker, more immediate and harder to evade. Such a world will require clearer thinking from those to whom the job of securing value for patients and the public is entrusted. If it is indeed the case that the future path of global economic growth will be substantially lower than in the past, then policy responses must reflect the long-term nature of this phenomenon. One-off improvements in health system technical efficiency might be helpful where they are available, yet they cannot be sufficient. Only solutions that are designed for the long haul are likely to be of enduring value. In the long-run, it is likely that strong institutions underpinned by effective institutional and professional ethics and cultures are what will be most important to create the strong and sustainable health care systems that can endure in an uncertain future.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.