Introduction

Unlike the Tang dynasty, the Song dynasty was not powerful enough to establish a tribute-based international order. Under the tribute system that required neighboring states to observe courtesies as vassal states to Chinese dynasties in return for recognition of their sovereignty and territory, only the sovereign of each state had the right to build diplomatic relations with China and conduct trade, which only took place in the form of tributes. The Song dynasty, however, which was unable to construct a tribute system around it, permitted private trade alongside official international trade under the ostensible purpose of conducting tributary missions, a policy stance that was maintained until the early fifteenth century, when the Ming dynasty was founded and prohibited overseas trade with the exception of tributes.Footnote 1

In addition, the tendency of allowing private trade became intensified under the Song in order to ensure large-scale military preparedness as it bordered strong nomad-based states. As a way to cover its increasing military spending, the Song relied heavily on the indirect taxation of commerce, instead of fixed land taxes.Footnote 2 This led to a growing interest in revenues from tariffs generated from trade.

Private trade began to be permitted in the middle of the eighth century when the Tang's international power weakened. Arab and Persian Muslim merchants gradually broadened their domain into the coastal regions of China, as they played an important role in the trade routes connecting the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. Around the mid-eighth century, there were a number of Muslim trade vessels sailing into Guangzhou port (廣州港) of China and at least thousands of Muslim merchants in Yangzhou (揚州).Footnote 3

However, the region faced a turning point as merchants based in China, including foreign merchants, emerged as a leading power in maritime trade in the seas of Eastern Eurasia in the ninth century.Footnote 4 While trade had previously taken the form of merchants from Southeast Asia, India, and West Asia sailing to Chinese ports, after the ninth century, the mainstream trend in maritime trade gradually shifted toward the tendency for merchants based in China to travel to the Goryeo (高麗, a kingdom based in the Korean Peninsula), Japan, or Southeast Asia. Although there was a short-lived attempt to create a state monopoly over trade in the early Song dynasty, maritime trade by Chinese merchants was fully permitted starting from 989,Footnote 5 which led merchants based in China, who traveled across the South China Sea and East China Sea, to occupy the leading position in maritime trade. Consequently, Chinese settlements began to form in various locations including the Goryeo, Japan, and Southeast Asia around the twelfth century.Footnote 6

Previously, there had been an underlying assumption regarding the background of the formation of Chinese communities that, as Chinese merchants traveled between their home country and foreign countries over a long period of time, they came to establish a close economic and social relations with the ruling elites of their host countries, which allowed their residential communities to form naturally.Footnote 7 To summarize, Chinese merchants established overseas bases while traveling between China and their respective trading countries, married local spouses to raise families there, and then naturally entered into long-term residence or settled permanently.

This was also affected by the sailing conditions of the era. As the sailboats known as Chinese junksFootnote 8 were used as the main means of maritime transportation at the time, merchants were likely to stay in their host countries for longer while waiting for the proper seasonal winds for the trip home. Given this possibility for the natural establishment of Chinese settlements, the study on Chinese communities has primarily focused on merchants' long-term residence or settlement in their host countries. Another contributing factor to this trend is the fact that the interest in overseas Chinese, particularly in Southeast Asia, was significantly motivated by their economic roles as merchants or capitalists in various regions of their residence.Footnote 9

However, examining the records of overseas Chinese communities in the Song period shows that it was more often the case for Chinese migrants with knowledge or skills required by their host countries and then employed to serve as public officials there. Of course, since these materials were written largely by the Song court or its local officials, their focus was placed more on the emigration of intellectuals, rather than merchants. Nonetheless, since descriptions of Chinese residential quarters in neighboring countries around the twelfth century are largely based on these sources, it is necessary to understand the formation of Chinese communities with a focus on the figures mentioned in these records, instead of merchants.

Nevertheless, existing studies have shown a strong inclination to discuss the figures mentioned in these sources based on the premise that they were merchants or at least had backgrounds as trade merchants, even in cases where they worked as government officials in neighboring countries.Footnote 10 This assumption is largely based on two factors. The first is the premise that only merchants were fully permitted to sail out abroad during the Song period, meaning that those who were not fully permitted must have been special exceptions. The second is the perception that a wide range of classes were involved in trade during the Song period, including intellectuals.Footnote 11

The term “intellectuals” in the Song dynasty did not refer to those who simply had the basic knowledge to engage in intellectual activities, but rather mainly referred to prospective, current, and former government officials. These included former and current officials; those on the waiting list for appointment after having passed state examinations or being qualified to become government officials through other channels such as recommendations by relatives holding high-ranking public posts; those with a history of applying for the state examinations; and students enrolled in the central and local schools for the purpose of preparing for state examinations. They were also a part of privileged classes that were exempted from corvée and received preferential treatment under the criminal law.Footnote 12 Some of them engaged in trade for economic interest. Therefore, Chinese figures who were mentioned as government officials in other countries were judged to have visited foreign countries for the purpose of trade and then become public officials after being recognized for their talent.

However, this assessment needs to be reexamined in two aspects. First, there were those who traveled overseas with the express intent to obtain a government post, rather than conducting trade. These figures already existed by around 1003, as mentioned below. These migrants generally left China by land at first, but records from 1078 onward indicate that some had begun to depart by sea. Thus, intellectuals who sought to sail out abroad had various purposes such as gaining profits through maritime trade and seeking a government post in other countries. However, preceding research has focused on the former purpose of trade to date.

In addition, the Song government began to regard even the aforementioned intellectuals, whose traits as merchants had been emphasized previously, as prospective officials and implement relevant policies under this assumption. For example, in cases where impoverished intellectuals were registered as merchants and engaged in maritime trade, the Song government classified their status as prospective officials and placed them on the overseas travel ban in 1112.Footnote 13 While merchants were fully permitted to travel overseas for trade since 989, intellectuals continued to be prohibited to travel overseas regardless of their purpose. The fact that extant historical records of the Song dynasty mainly focus on the bureaucratic nature of overseas Chinese citizens is deemed to be attributable to the focus on intellectuals, even in cases where certain figures simultaneously had characteristics of intellectuals and merchants.

China's neighboring countries employed Chinese people due to their essential philosophical and systemic knowledge for state governance, as opposed to their trading abilities. This brought about cases where some Chinese figures were forced to stay in their host country.Footnote 14 Such forced habitation would not have been necessary if the said Chinese figures had been employed to serve as trade merchants, since it would have been sufficient to allow regular visits to their home country. Therefore, even in cases when Chinese figures had originally arrived in their host country for trade, their subsequent residence in the host country was predicated upon traits other than their competencies as merchants. In this regard, it is necessary to review the Chinese migrants without being bound by the premise that they were merchants.

Also, the migration of population in search of new opportunities also coincides with the demographical situation that China faced at the time. The Song dynasty is characterized as a period in which its newly cultivated southern regions outpaced the northern regions in economic and demographic preeminence and no more frontier settlements were left to accommodate its growing population.Footnote 15 Under these conditions, the regular traffic of vessels to underpopulated regions that were relatively rich in resources created the background for more people to sail abroad in search for opportunities that they could not access in China or for better living conditions than in China. This resulted in diverse classes of Chinese diaspora with intellectuals on the top of the hierarchy.

Meanwhile, the existence of numerous figures with different traits from merchants would indicate a close link between the formation of Chinese residential communities and the way in which the Song controlled the outward travel of figures other than merchants. As such, this study examines the way in which the Song court identified and controlled the population within its territory and the connection between such control measures with the formation of Chinese residential communities abroad, based on laws on outward travel that were enacted by the Song.

To this end, first of all, Chapter 1 conducts a review of historical sources compiled on the Song period, records written by local officials, and documents from the Goryeo and Japan regarding overseas Chinese settlements. This aims to verify the hypothesis that extant historical sources focused on Chinese diaspora such as intellectuals whose purpose was not related to trade. In order to specify the time when the figures mentioned in Chapter 1 began to move abroad, Chapter 2 closely examines overseas travel bans by reviewing statute books, compilations of historical sources, and Su Shi wenji (蘇軾文集, Collection of works from Su Shi) that discuss the Song period. This is particularly because the period when overseas travel bans were enacted mainly coincided with the time of active population migration by sea, which is believed to be closely related to the formation of Chinese communities overseas. Based on the premise that the increase in vessel traffic served as the background for the active migration of Chinese people abroad, Chapter 3 finally intends to examine the law that caused the rapid increase in vessel traffic. With the maritime traffic increasing due to the enactment of related law, a consequent increase in the migration of Chinese people is deemed to be related to the appearance of Chinese communities around the same time in most overseas regions connected to China by sea.

Reexamination of overseas Chinese communities in the Song period

Although such examples do exist, it is not the case that merchants formed the core of overseas Chinese residents in the records on Chinese communities overseas. According to the actual records on Chinese communities that were formed around the twelfth century, their main residents were not merchants, but rather those who possessed academic and technical knowledge from China and therefore had the capacity to contribute to the governments of their host countries.

In the case of Japan, as of 986, there was already records of a Chinese merchant establishing long-term residence in the country and having a child with a Japanese woman while residing in Japan.Footnote 16 However, the term tōbō (唐坊 or 唐房), which refers to a Chinese community, appeared around 1097 at the earliest as a growing number of Chinese people began gathering and residing in Japan.Footnote 17 It was also found that Chinese citizens staying in tōbō communicated their knowledge or skills of medicine and musical instruments to Japan.Footnote 18 These examples indicate the active participation of Chinese migrants in their host country, utilizing the knowledge and skills gained in China.

In this regard, it would be more accurate to classify them as migrants with knowledge or skills that were valued highly overseas, rather than merchants. In the case of the Goryeo, there were even many cases in which Chinese people were appointed as government officials. Hundreds of Chinese people, mostly from Fujian (福建), lived in Gaegyeong (開京), the capital of the Goryeo after arriving on trade vessels. The Goryeo government tempted them with official positions after testing their talent in secret or even forced them to stay there. Under this situation, when Song envoys visited the Goryeo, they collected and returned with any Chinese citizen who sent them an appeal wishing to return home.Footnote 19

There are some specific examples. Zhou Zhu (周佇), from Wenzhou (溫州) of China, traveled to the Goryeo on a trade vessel in 1005 and worked as a government official there until he died in 1024. In another case, an educated man well-versed in medicine, Shen Xiu (愼脩) from Kaifeng (開封), traveled to and resided in the Goryeo until his death in 1101, having served as a government official in the reign of King Munjong (文宗, r. 1046–83). His son Shen Anzhi (愼安之) also became a government official of the Goryeo in the reigns of King Yejong (睿宗, r. 1105–1122) and King Injong (仁宗, r. 1122–46), comprising an unusual case in which a Chinese father and son both served the Goryeo court. In particular, Shen Xiu rose to the position of Chamjijeongsa (參知政事), a junior two-grade (the fourth rank among a total of 18 ranks in the Goryeo government). These Chinese were generally well educated and thus often became appointed as government officials, some of whom were well-versed in musical instruments, medicine, or incantations. After Zhang Ting (張廷), who was recorded to have passed the Chinese civil service examination, also traveled to the Goryeo in 1052, more Song citizens who had passed the state examination went on to hold government positions in the Goryeo.Footnote 20

However, it was not the case that every Chinese émigré was accepted. Instead, their capabilities were tested upon arrival with only those who passed being accepted, while others were returned to their original country. For example, Yang Zhen (楊震) from the Song came to the Goryeo on a merchant vessel and claimed to pass the first state examination in the Song. However, he failed to pass multiple tests in the host country and was sent back to China in 1081.Footnote 21 Meanwhile, the Goryeo also implemented a policy in 1091 to attract more Chinese people with document-writing or combat skills by earnestly requesting their prolonged sojourn and offering higher-ranking posts and higher salaries.Footnote 22

In cases where their arrival routes were identified, most of these migrants had traveled to Goryeo ports on trade vessels. They often worked as government officials after having their talents recognized and lived in the Goryeo until their deaths. Of course, there are also examples of Song merchants in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries who traveled between China and the Goryeo while basing their residence in both countries simultaneously, with some even marrying local spouses.Footnote 23 Nevertheless, remaining records from the Song and Goryeo direct more attention on the residency of Chinese intellectuals, rather than merchants. Unlike merchants traveling between two countries, these Chinese intellectuals settled and lived in the Goryeo until they died.

It also shows that many Chinese people from Fujian lived as high-ranking officials or aristocrats in Jiaozhi (交趾), corresponding to present-day northern Vietnam in the late eleventh century. For example, there was a Chinese man named Xu Boxiang (徐伯祥) who repeatedly failed the second round of the state examination after passing the first round in the Song. After hearing that Hokkiens were treated well in Jiaozhi, he secretly sent a letter to the Jiaozhi court in 1073 to express his intention to serve the king of Jiaozhi instead of the Chinese emperor since he was given no chance to work for the Chinese court. Warning Jiaozhi of an impending invasion by the Song, he proposed that Jiaozhi invade the Song first while he would aid Jiaozhi from within. This resulted in the outbreak of war between Jiaozhi and the Song. As the war developed, Xu Boxiang's act of treachery was discovered and he ultimately committed suicide.Footnote 24

Among overseas Chinese settlers, many were from Fujian, because the region had a shortage of land in proportion to its population and therefore became well known for the migration of its population.Footnote 25 According to the Chinese records on Jiaozhi, people from Fujian received favorable treatment and were appointed as government officials in the country, because its forefather, Lý Công Uẩn (李公蘊), was also from Fujian.Footnote 26 In the Goryeo, a significant number of Chinese people who lived in Gaegyeong were from Fujian as well. In particular, those with the ability to prepare documents were given favorable treatment in both Jiaozhi and the Goryeo.

Since gaining its independence from China in 939 after having been incorporated into Chinese territory around 111 BC, Jiaozhi continued to pursue Sinicized governance systems such as the primogeniture rule of royal succession and the adoption of a bureaucracy based on state examinations, in order to maintain its independence against continued Chinese aggression.Footnote 27 The Goryeo was also built on a centralized bureaucracy amid continued external tensions with northern tribes such as the Khitans, Jurchens, and Mongols. In order to prepare for external crises, the military system required a unilateral decision-making process and a swift chain of command.Footnote 28 Both countries that sought to adopt a Chinese-style political system therefore needed to recruit people who were well-versed in the Chinese bureaucracy and administrative system. Although the process of centralizing power could not be completed within a short period of time, naturally, these Chinese figures showed greater loyalty toward the sovereign of their host countries since their fragile social standing in their respective host society made them more dependent on their personal relationship with the king.

The situation in which those familiar with the Chinese document system worked in association with the local authorities is also identified in Champa (占城, or Zhancheng, present-day central and southern Vietnam), Srivijaya (三佛齊, or Sanfotsi, a kingdom based on the Indonesian island of Sumatra), and South India. In the case of Champa, in 1050, the Cham ruler presented tributes including 201 ivories and 79 rhino horns, along with two originals of diplomatic documents each written in Cham and Chinese to the Song emperor.Footnote 29 When Chen Yingxiang (陳應祥), a Song captain, sailed into the Song in 1167, the vessels carried a total of 12 Chams including the envoy, deputy envoy, and their attendants, with two originals of diplomatic documents from the Cham ruler, each written in Cham and Chinese, and a tribute list written in Chinese.Footnote 30

This demonstrates that Champa sent a diplomatic document and tribute list written in Chinese to the Chinese emperor when presenting tributes, in which Chinese people who were fluent in both Cham and Chinese languages were likely to have been involved. For instance, Wang Yuanmao (王元懋) of Quanzhou (泉州) mastered the languages of Southeast Asian countries after learning them from his teacher while working at a Buddhist temple during his childhood. When he traveled to Champa on a ship, the Cham king admired his fluency both in Cham and Chinese languages, leading him to become the King's resident guest, marry his daughter, live in the country for 10 years, then return home.Footnote 31 Chinese figures like Wang Yuanmao were highly likely to have written the diplomatic documents sent to China.

The close relationship between Champa and China required a denser and more accurate communication, beyond simple exchanges of envoys, since the intention of the Chinese side to gain the military cooperation of Champa for the conquest of Jiaozhi, ran parallel to Champa's internal power struggle to seize power by strengthening relations with China.Footnote 32 Thus, it appears that it was all the more essential to utilize an intermediary who had the capacity to accurately understand and communicate the intentions of the two countries.

An example of sending diplomatic documents written in Chinese can be also found in Srivijaya. In 1082, Son Jiong (孫迥), the chief of the Guangzhou Shibosi (廣州市舶司)Footnote 33 reported that the captain of a ship from Southeast Asia delivered 227 taels of mature camphor and 13 bolts of cloth to him, along with Chinese documents from the ruler of Srivijaya and his daughter who oversaw state affairs.Footnote 34 Although the Chinese documents were sent to the local official, instead of the Chinese emperor, this example indicates that the Chinese language was used alongside the native language in Srivijaya and that the biaowen (表文), diplomatic documents to be submitted to the Chinese emperor, was written in Chinese.Footnote 35

In the case of the Chola (注輦) dynasty on the southeastern coast of present-day India, the King dispatched an envoy in 1077 to pay a tribute of gifts along with two originals of biaowen, each written in the native and Chinese languages.Footnote 36 This demonstrates that, since 1050, kings or rulers in Champa, Srivijaya, and South India sent diplomatic documents written in Chinese to the emperor or local officials of China. This implies that figures familiar with the Chinese document system were at least working in connection with the local ruling power. Based on these circumstances, Kamei Meitoku argue that Chinese communities had been formed in Southeast Asia as of the mid-eleventh century at the latest.Footnote 37

It was around 1078 when the Song court took action to ban people familiar with the Chinese academic or administrative system from sailing out of the country. The formation of Chinese communities overseas was followed by the Song's movement to deter the migration of Chinese people from the country by sea, which shows the interconnection between the two trends. Therefore, the next section will examine the emigration control implemented by the Song.

Emigration control over people

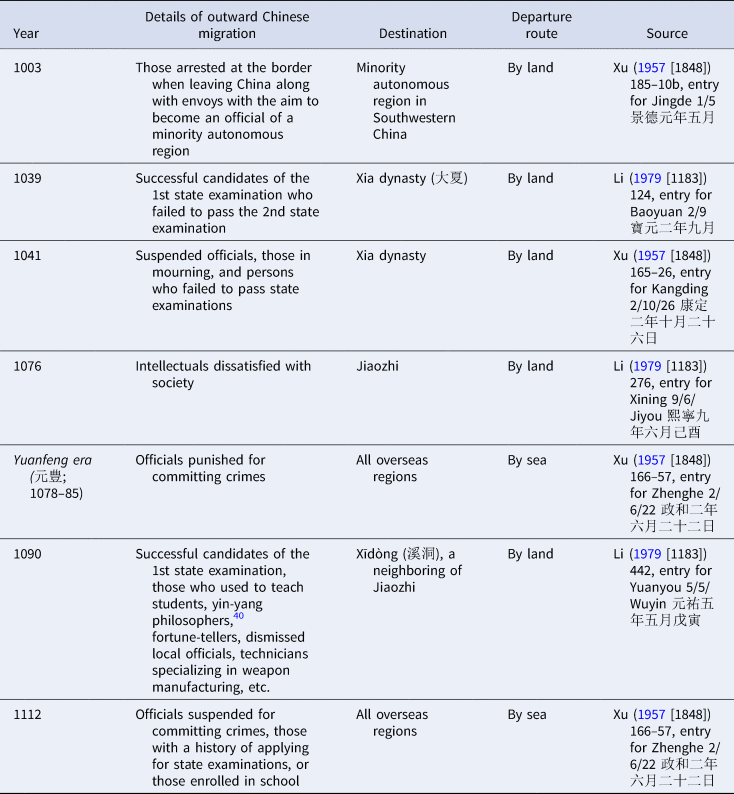

Like previous Chinese regimes, the Song tended to control people who crossed the border. According to Song xingtong (宋刑統), the basic criminal law of the Song enacted in 963, it was prohibited for anyone to cross the border without an official pass.Footnote 38 Given the repeated bans on the departure of Chinese people traded as slaves, spies, deserters, and women,Footnote 39 it can be deduced that such demographics were largely those emigrating overseas. The population migration also took place among Chinese intellectuals. In order to examine the time when this trend began, Table 1 outlines cases in which this issue was discussed at the Song court or the departure of intellectuals became prohibited.

Table 1. Discussions and bans on the overseas travel of intellectuals during the Song period

Table 1 indicates that the migration of intellectuals to regions where shared land border with China had begun to take place already by around 1003. As military tensions continued with the Xia dynasty at the time, there was an issue in which disgraced Chinese intellectuals moved to the Xia dynasty by crossing the western border of China. In 1041, many suspended officials, those in mourning, and persons who failed to pass the state examinations gathered in Hebei (河北), Hedong (河東, present-day southwestern region of Shanxi Province), and Shaanxi (陝西), even though they were not from these regions. They were regarded to be pursuing their own personal interests with no regard for their wrongdoings in the case of dismissed officials, their parents' deaths in the case of those in mourning, and their own scholarly mistakes in the case of those who failed state examinations.Footnote 41 This indicates there was a movement for intellectuals who lost employment or could not find employment in the Song to travel to the Xia dynasty in search of new opportunities.

These figures played a critical role in introducing Chinese systems or establishing strategies to counter China in their host countries. On the Chinese side, there was a perception that the figures gathering around foreign sovereigns helped their host country to restructure itself based on Chinese systems, develop their national strength, and establish a strategy to invade China.Footnote 42 The Jiaozhi king Lý Nhân Tông (李乾德, r. 1072–1127) deliberately violated the Song's orders and invaded the Song's territory, which is regarded to have involved numerous Chinese figures residing in Jiaozhi.Footnote 43

In countries that shared land borders with China, there were not only Chinese settlers but also native Chinese people who lived in regions that had originally been Chinese territory and then were incorporated into the country concerned. These regions included the Sixteen Prefectures of Yan and Yun (燕雲十六州) in the Liao dynasty (大遼), and Lingzhou (靈州, present-day Lingwu City of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region) and Xiazhou (夏州, present-day Jingbian County of Shaanxi Province) in the Xia dynasty. Since the acquisition of the regions into their territory, these countries adopted Chinese systems such as by introducing Chinese titles of nobility, emulating the Chinese bureaucratic ranking system, employing Chinese figures, reading Chinese books, using Chinese wagons, wearing Chinese clothing, and adopting Chinese laws and regulations.Footnote 44 The introduction of Chinese-style systems and etiquette contributed to stabilizing the social order in the countries concerned and containing internal rebellions.Footnote 45

Especially in the countries in military tensions with the Song, there was a demand for Chinese figures who were able to adopt Chinese systems that could be used to prevent social disorder by strengthening internal order or to establish a strategy to counter the Song based on their thorough knowledge of the Song's affairs. Such demand was satisfied by those who failed to enter the Song's bureaucracy or former officials who failed to build a successful career in the Song's bureaucratic society.

The problem of intellectuals' departure was limited mainly to the areas sharing land borders with neighboring countries until the 1070s. However, it can be confirmed there were rules to prohibit people familiar with the Chinese academic or administrative system from sailing out of the country since the 1070s. More specifically, the regulation that banned former officials who had been sentenced to a punishment for a crime from sailing out to other countries had already been implemented in the Yuanfeng era (元豊, 1078–85) and the provision to ban educated intellectuals from sailing out abroad was newly added in 1112.Footnote 46 As active vessel traffic resulted in an increasing migration of people abroad by sea, their destinations included all overseas regions traveled to and from by Chinese ships. It can be assumed that the migration of intellectuals was concentrated to the countries in military tension with the Song until the 1070s, and then gradually expanded to all regions with which the Song conducted exchanges.

There already existed regulations that prohibited groups of people such as women, spies, and deserters from leaving the country, but by 1105, they were banned from boarding ships entirely.Footnote 47 Though vessel traffic promoted the migration of population in some aspects as well as trade in goods, the policy of identifying people on board seagoing ships had not been in place from the start since 989 when merchants were fully permitted to sail out for maritime trade. According to extant laws and regulations regarding the departure of merchant vessels, trade vessels were permitted to voyage overseas in the 1040s, with only the type of cargo and destination required to be reported in order to obtain a certificate of passage from the relevant authority. By around 1086, the number and names of passengers were also required to be reported (see Table 2).

Table 2. Details of trade vessels to be reported before departureFootnote 49

Before leaving the country, trade merchants had to report to the relevant authority with regard to the number of vessels, names of captain-level figures and crew members, types and amounts of cargo, the guarantor of the vessel, their destination, etc., to obtain a certificate of passage that would later be submitted upon their return from abroad.Footnote 48 This implies that the focus of departure control was initially placed on export goods or destinations of vessels, and then later shifted to identifying people leaving the country during a specific era.

The background of this change of stance reflected the reality that captains of trade vessels began to take abroad Chinese people who were familiar with Chinese academic or administrative system since the Yuanyou era (元祐, 1086–94), such as previous candidates for state examinations or former low-ranking officials with a criminal record.Footnote 50 Although it had been a problem since before the Yuanfeng era that former officials who had been punished for committing crimes subsequently left to take a voyage abroad, it was since the Yuanyou era that the overseas departure of intellectuals in general became an issue.

It also seems natural that little attention was dedicated to identify travelers journeying abroad for trade in the first place, given the very nature of trade. As maritime trade is a profit-seeking activity that comprises delivering products required in foreign countries and bringing foreign goods back, it is completed by a series of outgoing and returning journeys with no point in one-way voyages. As such, merchants generally tend to return home no matter how long it takes, since the original purpose of their trip would be wasted if they do not return to their point of departure.

However, this is not to claim that individual passengers onboard trade vessels all shared the same interests with regard to traveling on their respective vessel. Some did not travel for trade, while others who did travel for trade may have concluded that they would prefer to reside overseas. Such differing views between trade vessels and their passengers with regard to the prospect of returning home resulted in a situation where individual passengers had the choice of remaining at their overseas destination, even if the vessel that they had traveled on decided to return.

There were sometimes cases in which figures at the vice-captain level, which were often wealthy merchants, chose not to return to China. In July 1026, Zhang Chengfu (章承輔), who was the vice-captain of a vessel sailing back to the Song from Japan, decided to stay behind in Japan because he was too old and frail to the point of finding daily activities difficult and had no intention to return to China. His Japanese spouse was also an elderly lady. In order to verify whether the old couple were still alive, their son Zhang Renchang (章仁昶) was recorded arriving in Japan in August 1027.Footnote 51 Unfortunately, his father had already passed away before his arrival.Footnote 52 Although Zhang Chengfu is considered to have retired after handing over the family business to the next generation, it can be surmised that even merchants decided to stay abroad if they had no intention to go back to China.

In addition, it was not the case that all passengers on trade vessels were merchants. Although this is an example from a later era, according to the records on the present-day Cambodia at the end of the thirteenth century, many crew members on ships that traveled to Cambodia deserted as life there was more comfortable than in China.Footnote 53 This could mean that Chinese communities that formed in foreign countries served as an alternative for Chinese people with difficult livelihoods in China or those who simply wished for better living conditions than in China. Among these Chinese migrants, intellectuals and bureaucrats occupied the peak of the social hierarchy. The fact that members of such privileged classes left the country for better opportunities points toward the possibility that those in worse social conditions would have been even more tempted to migrate abroad.

As such, a growing number of people leaving the country for non-trade-related purposes reflects an increased social mobility in the population. The Song period saw stronger tendencies than previous dynasties toward leaving the homeland to move to other regions and engaging in business rather than agriculture. There were several factors at work in this phenomenon, such as population growth, land shortage, a large number of farmers who lost their agricultural land due to land privatization and accumulation, and the growth of cities, commerce, and industry.Footnote 54

Just like the previous Chinese regimes, the Song court also compiled the family register to organize and manage the population, based on which taxes and duties were collected and imposed. In this regard, the government did not view the increase in migration favorably. However, it was unable to prevent this increased migration in practice, finally allowing people to relocate to another region and transfer their family register there on the condition of undergoing a year of punishment.Footnote 55 In essence, the punishment was a kind of precondition for being able to transfer the family register elsewhere. Given the fact the Song government permitted private merchants to engage in overseas trade, Zheng Youguo contend that the Song was different from the previous dynasties that sought to control people by binding them to specific regions.Footnote 56

In addition, the Song dynasty did not actively seek to tie people to the land because non-property tax revenue such as customs and commercial tax accounted for a higher portion of its national finance than in previous regimes.Footnote 57 It also employed a standing military whose soldiers were paid a salary, other than drafting soldiers according to the ratio of cultivated land, which created a class of citizens who were not attached to the land. The combination of such tendencies can be said to have increased the movement of people during the Song period. This emigration was not limited to the Song's territory and expanded further abroad.

Thus, the emergence of overseas residents and the formation of their overseas settlements were not solely attributable to the Song's policy of permitting merchants to travel overseas for trade. Those who became detached from their birthplace then moved to cities, handicraft production areas, or ports in search of jobs and even further traveled abroad. This demonstrates the connection between China's domestic situation to the international phenomenon.

The investigation of passengers on trade vessels, which are documented from around 1086, reflected the situation in which the overseas population migration increased to an extent recognized by government agencies. This situation coincided with China's population status, which reached its peak in 1080. Due to the expansion of arable land and population growth caused by migration from the north to south, from highlands to coastal regions, by the end of the eleventh century, the southern regions had replaced the northern regions in economic and demographic preeminence before plateauing in 1080. After the subsequent phase of decline in the major regions of both North and South China, the population in each area remained about the same in 1542 as in 1080.Footnote 58 Those who faced difficulties in establishing a livelihood in their regions of origin migrated to the southern or coastal regions in search of better opportunities, but when even this trend reached a plateau, it appears that overseas relocation began to be considered as a possible option from the late eleventh century onward.

The situation of supply outpacing demand was the same for intellectuals. As the expansion of social classes that were allowed to take the state examinations combined with the Song court's intention to take advantage of the state examinations as an instrument of governance, the number of applicants for the state examinations experienced an explosive growth. This resulted in the growth in state examination applicants outpacing the rate of population growth. As such, only hundreds among hundreds of thousands of applicants finally passed the state examinations, taken once every three years, resulting in the staggering odds of one in 1,000. Thus, many applicants failed to pass the state examinations even at the age of 50 or older after starting to take the state examinations at the age of around 20. Given that fact that the preparation for the examinations usually began before the age of eight, this generated many prospective officials who spent their entire lives preparing for the examinations.Footnote 59

In response to the explosive increase in applicants, the pass rate was raised for the state examinations, thereby resulting in the Song dynasty producing the largest number of successful state examination candidates in Chinese history at a rate five times higher than the Tang dynasty and four times higher than the Ming and Qing dynasties.Footnote 60 Even if the successful applicants were qualified to enter government service, they had to wait a long time before being actually appointed as an official due to the limited number of government positions. The competition for public posts had already become fierce around 1000, and officials had to wait one or two years on average before being reappointed after completing their term of office.Footnote 61 The migration of prospective officials, as found in 1003 in Table 1, appears to reflect this situation.

Although additional administrative units were newly created with the development of southern regions and the population growth, the competition over government posts appears to have become even more intensified around 1080 when the population reached its peak. This may have driven some intellectuals who were unable to find employment at government agencies to turn their attention overseas. As inferred through the Goryeo's cases of offering higher posts or salaries, Chinese intellectuals were likely to have received better treatment in foreign countries outside of the Song. These factors are believed to have served as the motivation for them to seek overseas residence.

As it became mandatory to report all passengers on a seagoing vessel around 1086, as a means to prevent the population migration, there are examples in which Chinese people overseas were urged to return to China. Liu Cheng (柳誠), a Song merchant who traveled to the Goryeo in 1124 and brought a letter from the Mingzhou (明州) authority, which granted permission for free residence in the Goryeo to Du Daoji (杜道濟) and Zhu Yanzuo (祝延祚) who were staying in the Goryeo at that time. Previously, the Mingzhou authority had sent an official document to the Goryeo on two occasions to call for their return, as the two Chinese men had not returned home after traveling to the Goryeo on a trade vessel. Then, the Goryeo court sent to a diplomatic document to the Song emperor to ask for permission for their residence in the Goryeo, and honoring the wish of the Song emperor, the Mingzhou authority sent the letter that granted permission for their residence.Footnote 62 Although there were calls for Chinese migrants to return, they were eventually granted permission to reside overseas at the request of their host country.

As seen in the case of Du Daoji and Zhu Yanzuo, it is deemed to have been quite difficult to forcibly repatriate overseas Chinese as long as they did not actively wish to return. Despite the existence of Chinese officials working for the Goryeo court as late as the mid-thirteenth century,Footnote 63 there are no recorded cases in which these people were urged to return. This reflects the reality that, even if such laws existed, state agencies and officials had little will or means to enforce them.Footnote 64

Therefore, these measures – the overseas voyage ban on intellectuals, women, spies, and deserters; mandatory reporting of all passengers on seagoing vessels; and explicit recommendations for overseas Chinese to return home – demonstrate that the issue of population migration by sea had come to the forefront for the first time in the period from the late eleventh century to the early twelfth century. However, the bans were insufficient to halt the movement of people. Moreover, it can even be surmised that the emigration trend accelerated further in the Southern Song period when the population grew in proportion to the land.Footnote 65 Qingyuan tiaofa shilei (慶元條法事類), a compilation of laws and regulations from January 1169 to December 1196 stipulates that trade merchants were subject to punishment for allowing people to sail out to foreign countries.Footnote 66 This could be interpreted to mean that the migration of various types of figures took place, to the extent that the act of providing outbound passage by sea was prohibited indiscriminately.

In fact, Chinese people of all backgrounds, not only intellectuals, were migrating into Jiaozhi in the 1170s. As a significant number of Chinese people moved from the Song to Jiaozhi, which had a smaller population than the Song, it was said that Chinese people came to account for half of Jiaozhi's population. Some Chinese people were traded as slaves, while those with special talents, skills, or ability to write documents were better treated. It is said that the number of migrants from the Song to Jiaozhi reached hundreds up to a thousand each year. Also, there were a significant number of criminals banished by the Song, exiles, and fugitives on the run among the Chinese people who lived in the region.Footnote 67 Meanwhile, Chinese figures took an active part in various fields of Japanese society from the eleventh to thirteenth centuries, such as architecture, shipbuilding, arts, crafts, Confucianism, and Buddhism.Footnote 68

It can also be said that the Song's move to regulate people leaving the country reflects the social situation regarding the partial emergence of people who intended to go abroad in search of different opportunities or better living conditions than China, as opposed to merchants traveling for the purpose of trade. Unlike trade merchants, these people were much likely to reside for a longer period or settle permanently in foreign countries. As such emigration became commonplace, Chinese communities came to be formed in various parts of the world.

Increase in Chinese merchants sailing abroad

As mentioned earlier, Chinese communities were formed as more people left the country to look for opportunities or jobs, other than merchants traveling for trade. Although it is difficult to identify a specific time, it appears that 1086 was a clear turning point when information on passengers was additionally included into the items to be reported to obtain a certificate of passage, as shown in Table 2. It can be speculated through the various examples described earlier that people with knowledge of medicine, music, and Confucianism were able to move abroad and find employment in the host country even before 1086. However, by 1086, the number of Chinese citizens residing abroad had increased beyond the scope of a few exceptions to reach a substantial enough number for the Song government to officially recognize the situation. In other words, a new trend of sailing out of the country for better opportunities had fully emerged. This trend led many Chinese citizens to reside overseas. Next, this study will examine the background behind this new trend in the overseas migration of the population around 1086.

The Song government bestowed a royal decree on September 17, 1085 to allow every foreign country to commission Song merchants to present tributes or conduct trade. Since then, Song merchants traveled to foreign countries more frequently by obtaining a certificate of passage and increasingly transported foreign envoys to present their tributes publicly.Footnote 69 However, at the request of Su Shi (蘇軾) who opposed the use of Song vessels to present foreign tributes or conduct trade under commission, an order to ban these activities was issued shortly thereafter. According to the public appeal submitted by the Song official Huang E (黃鍔) on October 17, 1128,Footnote 70 in 1090, the Minister of Confucian Rites Su Shi called for the abolition of the provision that had allowed Song merchant vessels to carry foreign missions or merchants for the first time in 1085, and his request was accepted by the Song court. However, there were still Song merchants who carried foreign envoys in 1128. As such, Huang E requested the Song court to punish anyone who violated the ban and the Song court approved the request. On November 22, 1129, the order was issued to punish any Song merchant who carried foreign envoys on a trade vessel without permission to two years of forced labor and confiscation of property.Footnote 71

Given that there are no examples of such a punishment being imposed in practice, the Song court seems to have knowingly overlooked the situation in which Song vessels continued to carry foreign tribute missions to the Song.Footnote 72 Examples of foreign tribute missions traveling to the Song on a trade vessel can be found even after 1128, as Champa commissioned Chinese vessels to present tributes to China in 1155 and 1167 and Cambodia did the same in 1205.Footnote 73 It appears that, despite the ban requested by some officials, it became common practice for Song vessels to intermediate foreign tributes after 1085.

Naturally, examples in which foreign merchants or envoys traveled to the Song on Chinese vessels had existed even before 1085. For example, a tribute mission from Java (闍婆) arrived in the Song in December 992. The mission was aboard a vessel owned by Mao Xu (毛旭), a Song merchant of Jianxi (建溪) Fujian, who had traveled to Java several times previously.Footnote 74 Also, in 1019, merchant Lin Zhen (林振) of Fuzhou (福州) was discovered to have concealed pearls to avoid taxes, thus resulting in all cargo on the vessel being confiscated, even the cargo that belonged to the foreign merchants onboard.Footnote 75 Foreign merchants traveling to China as passengers on Chinese vessels was a common occurrence since the end of the Tang dynasty.Footnote 76

Nevertheless, there was a perception in China that sending envoys on Chinese vessels to present tributes was a violation of proper protocols. For instance, in 1078, a Japanese envoy who had arrived on a Chinese trade vessel was received and returned under the name of the local government at the destination, instead of the name of the Song court, because the Japanese envoy had observed different protocols for tributes to other countries.Footnote 77 As the Song court officially permitted Chinese vessels to carry foreign envoys to the country, however, the sanction against this action seems to have been lifted.

As Song merchants were allowed to conduct overseas trade not only for their country but for foreign countries, the frequency of overseas travel by Chinese vessels significantly increased. For example, in cases where a Chinese vessel brought a foreign tribute mission to the Song, the vessel was likely to have transported the mission back to its home country after its diplomatic duties were completed. This necessitated round trips, and as the same trip now required two round trips, the frequency of seagoing voyages increased at face value.

Furthermore, as the ruling elites of trading countries came into contact more frequently, merchants were able to strengthen their personal networks. This is likely to have resulted in a growing tendency for merchants to intermediate not only goods but also talented persons at the behest of local authorities overseas.

The mediation of Chinese merchants to help various overseas clients to recruit people with valuable skills had taken place even before 1085, as seen in the abovementioned examples of the Goryeo and Jiaozhi. Once the official permission was given for the intermediation of foreign tributes by Chinese vessels in 1085, however, the perception developed since the Yuanyou era (元祐, 1086–94) that trade vessels generally transported educated persons with a history of applying for state examinations or former low-ranking officials with a criminal record, which indicates a degree of correlation between the former and the latter. As Chinese merchants officially became engaged in intermediating tributes or trade according to the needs of foreign countries, the number of people traveling abroad rapidly increased through trade vessels that now sailed more frequently between countries. This resulted in the near-simultaneous development of Chinese communities in various locations overseas.

Conclusion

The discussion thus far has mainly dealt with trade merchants in the context of Chinese figures temporarily residing or settling permanently abroad or Chinese communities as the colloquial term for their overseas residential settlements. As they frequently traveled abroad due to the characteristics of their occupation, they were more likely to reside in foreign countries for varying lengths of time in the process. In historical records of the Song regarding Chinese figures residing overseas, however, the focus was primarily on intellectuals and bureaucrats who were trained in the Chinese knowledge and administrative systems, comprising a different demographic altogether from merchants. Indeed, examining the relevant materials hardly produces the impression that merchants accounted for the majority of overseas Chinese figures at that time.

The movement of people as well commodities can only be facilitated by the back and forth travels of merchants. This can be seen as the background behind the formation of a Chinese community in each foreign region to which Chinese trade vessels traveled in the Song period. However, it was not merchants who simply traveled between countries, but people with the knowledge and skills sought by foreign governments who played a pivotal role in forming Chinese communities, as confirmed in the abovementioned examples from each of the Song's neighboring countries.

Merchants came to intermediate people as well as merchandise required by foreign countries as they traveled to these countries and built close relations with the local governments. The fact that merchants transported overseas those who had a history of applying for state examinations or former officials with a criminal record indicates that they had a keen understanding of the types of people in demand in various overseas regions. Although some Chinese were trafficked as seen in the example of Jiaozhi, it is believed that such extreme cases of forced relocation does not apply to all Chinese migrants and that many instead left China in search of better opportunities.

This paper strived to focus on the emergence of people who looked for opportunities overseas as the background for the formation of Chinese communities in the Song period, as opposed to trade voyages by merchants. This situation is clearly revealed through the Song's ban on overseas travel for those with different traits from merchants.

Examining trade-related regulations shows that the Song initially regarded the border control of people to be less important than border control for goods. At the time, state authorities focused on the cargo or destination of vessels, rather than their passengers. But then, with the proclamation of the regulation prohibiting certain groups of people such as intellectuals and bureaucrats from traveling abroad in 1078, it became mandatory around 1086 to report all passengers on a seagoing vessel. These regulations indicate that the emergence of people who sought to journey abroad for new opportunities had begun even before this period.

The movement of people then dramatically increased as Chinese vessels became officially allowed to carry foreign envoys and merchants to China in 1085. As Chinese merchants came to intermediate trade and tributes from foreign countries, they not only traveled more frequently, but also established closer relations with the local society and came to intermediate talented persons who were in demand in the local society. It is inferred this situation became the background behind the appearance of Chinese communities in most regions to which Chinese vessels traveled around the twelfth century. In addition, the growing number of seagoing vessels brought about an increase in the movement of both goods and people. The emergence of Chinese communities does not simply demonstrate the outcome of international exchanges and trade, and instead can be linked to the population trends and policies of the Song dynasty.

Conflict of interest

None.