In the Central Arabah, a hyperarid zone in Israel's far south, thousands of migrants from Thailand work in sweltering greenhouses, raising bell peppers that their employers hope to sell at lucrative prices in European winter markets.Footnote 1 The region's cooperative settlements were established in the 1960s and 1970s, in a belated revival of the principle of self-labor (‘avoda ‘atzmit), but in the 1990s they became capital-intensive agricultural enclaves dependent on the labor of disenfranchised migrants. Climate change, the removal of water from ancient, non-replenishing aquifers, and the destruction of desert ecosystems now combine to cast the continued viability of human life in the Arabah into question.

Chronologically, ecologically, and economically speaking, the Arabah is an “edge-case”—a term I borrow from engineering to describe situations in which significant parameters take on unusually large or small values. Edge-cases tell us about how systems react to extreme conditions; hence, the Arabah can help us to assess the ecological impact of Zionism, itself something of a chronological and economic edge-case among settler-colonial projects. This article locates the cooperative moshavim of the Central Arabah within the history of Zionist agrarian settlement, which I characterize as colonial in its goals and capitalist in its methods and assumptions throughout its history. Elsewhere in the country, colonization is today predominantly suburban in form, but the settlers of the Arabah have parlayed their ideological orthodoxy to import cheap workers, expand cultivation, and compete in global markets. A growing body of literature, much of it by scholars resident in the region, reveals the human and ecological costs of this achievement and points to the dangers ahead.Footnote 2

The Arabah is an outlier, but not an exception. The Zionist objective of creating and permanently sustaining a sovereign Jewish majority in the land of Israel has consistently been grounded in the expectation that settlers would live off the production of commodities for sale.Footnote 3 In the words of Ghassan Kanafani, Zionist colonization entailed “the transformation of . . . an essentially Arab agricultural economy to an industrial economy dominated by Jewish capital.”Footnote 4 Eventually, this transformation would empty the countryside, eliminate subsistence livelihoods, and reinvent remaining farms as low-margin businesses dependent on cheap labor and foreign markets. But the transition to capitalism also entailed the destruction of complex, long-standing ecosystems, leading to the emergence of a “metabolic rift,” an imbalance between the inputs and outputs of human and nonhuman systems that puts both at risk.Footnote 5 This process continues in the Arabah today.

Although Zionist settlement has always been primarily urban, the movement also has historically focused on agrarian settlement, utilizing large-scale investments in infrastructure, machinery, and raw materials to produce commodities for sale. At various points, the movement has deployed the labor power of indigenous Palestinians, Jewish settlers, and migrants who are neither. In characterizing this settlement as capitalist throughout, I follow Jairus Banaji and Nahla Abdo, who both identify the production of commodities for profit and the accumulation of value in the hands of a minority as defining characteristics of this mode of production.Footnote 6 Two features of early Zionism that are often cited to characterize it as noncapitalist, the concentration of land in the hands of “national” institutions and resistance to the employment of wage labor, should be understood as adaptations to the unusual context in which this settler-colonial movement was acting. When colonization began, Palestine's agrarian economy was already integrating into the capitalist world-system, and markets in land and labor were emerging. The establishment of “an industrial economy dominated by Jewish capital” depended on the restriction of access to these markets.

Profit in itself has never been the primary goal of Zionist colonization, and infusions of capital from overseas have often allowed Zionist leaders to subordinate the bottom line to political tasks, including the establishment of military and diplomatic leverage and ideological self-justification.Footnote 7 Such motives have been amply treated in recent scholarship, which emphasizes the primacy of the drive to “eliminate the native” in settler colonialism in general and Zionism in particular.Footnote 8 In practice, however, the colonization of Palestine has entailed both the elimination of non-Jews from the polity and their super-exploitation through split labor markets.Footnote 9

Despite the relative autonomy from financial constraints provided by unilateral capital flows, Zionist leaders from Theodor Herzl to Naftali Bennett have regarded profitable production as a benchmark and guarantee of their project's viability. However, this article argues that the metabolic rift between the agrarian modes of livelihood established by Zionist settlements and the nonhuman environment on which they depend renders these livelihoods increasingly precarious, especially in the Central Arabah but quite possibly elsewhere as well. Building on primary sources, on ethnographic research in the region in 2015–16, and on a wealth of scholarly literature, I demonstrate the depth and probable irreversibility of many of the ecological changes wrought in the Arabah. The conclusion raises the question of how a democratic decolonization of the region, involving the bedouin and Thai “others” of Zionist colonization as well as settlers, might grapple with these new and challenging circumstances.

The Political Ecology of Pre-Zionist Palestine

The sliver of land comprising Israel/Palestine encompasses diverse ecological zones that enable various forms of livelihood. The country's hilly central spine and the Galilee have sustained peasant populations growing wheat, barley, olives, and grapes for millennia.Footnote 10 Lowlands and seasonal marshes have historically supported smaller populations subsisting on foraging, buffalo-raising, and sometimes cultivation of tropical crops. Finally, more than half of the country is desert—a broad term encompassing zones where agriculture has been regularly practiced and more arid areas where domestic camels and goats have rubbed shoulders with abundant wildlife.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, much of Palestine's population was engaged in subsistence production organized through kinship-based arrangements subsumed under the cultural idiom of musha‘, meaning “common” or “shared.”Footnote 11 In the hilly heartland, elites extracted surpluses of grain and olive oil for local industries, for commercial export to urban centers such as Cairo and Damascus and to feed the imperial military, linking Palestine to the growing world-system.Footnote 12 But most cultivated land was crown property (miri) over which peasants could exercise usufruct rights as long as they kept up cultivation, and the right of peasants to continue residing and cultivating on their land was legally enshrined.Footnote 13 Integration into the world-system accelerated in the 19th century as coastal towns like Jaffa and Gaza forged commercial links to Europe. Population and economic activity shifted to the west, and the crown sold large tracts of lowland to urban commercial families, such as the Sursuqs of Beirut.Footnote 14 Some landowners allowed their tenants to continue subsistence cultivation in return for a share of the harvest, but others raised citrus for export using water pumped from coastal aquifers with animal power and employing commuting peasants and a new peri-urban proletariat.Footnote 15 Despite the formalization of title mandated by the Land Code of 1858, most holdings remained unregistered, and many village communities continued to organize land allocation collectively to ensure fairness, stability, and soil vitality.Footnote 16

In the triangle of land which was to become known as the Negev or Naqab, the autonomy of the bedouin inhabitants remained largely intact until the First World War.Footnote 17 South of a line connecting Gaza and Hebron, arability, population density, and wealth all fell away as tribal territories grew larger and the Ottoman military's coercive power faded. Over the 19th century, the empire began encouraging its nomadic subjects to settle down and cultivate, a shift exemplified by the establishment of the garrison town of Beersheba.Footnote 18 But the roughly 80,000 bedouin residents of the southland maintained ownership of their tribal territories (dirat) and connections with kin in the Sinai and Transjordan well into the Mandate period.Footnote 19

The Arabah Before Israel

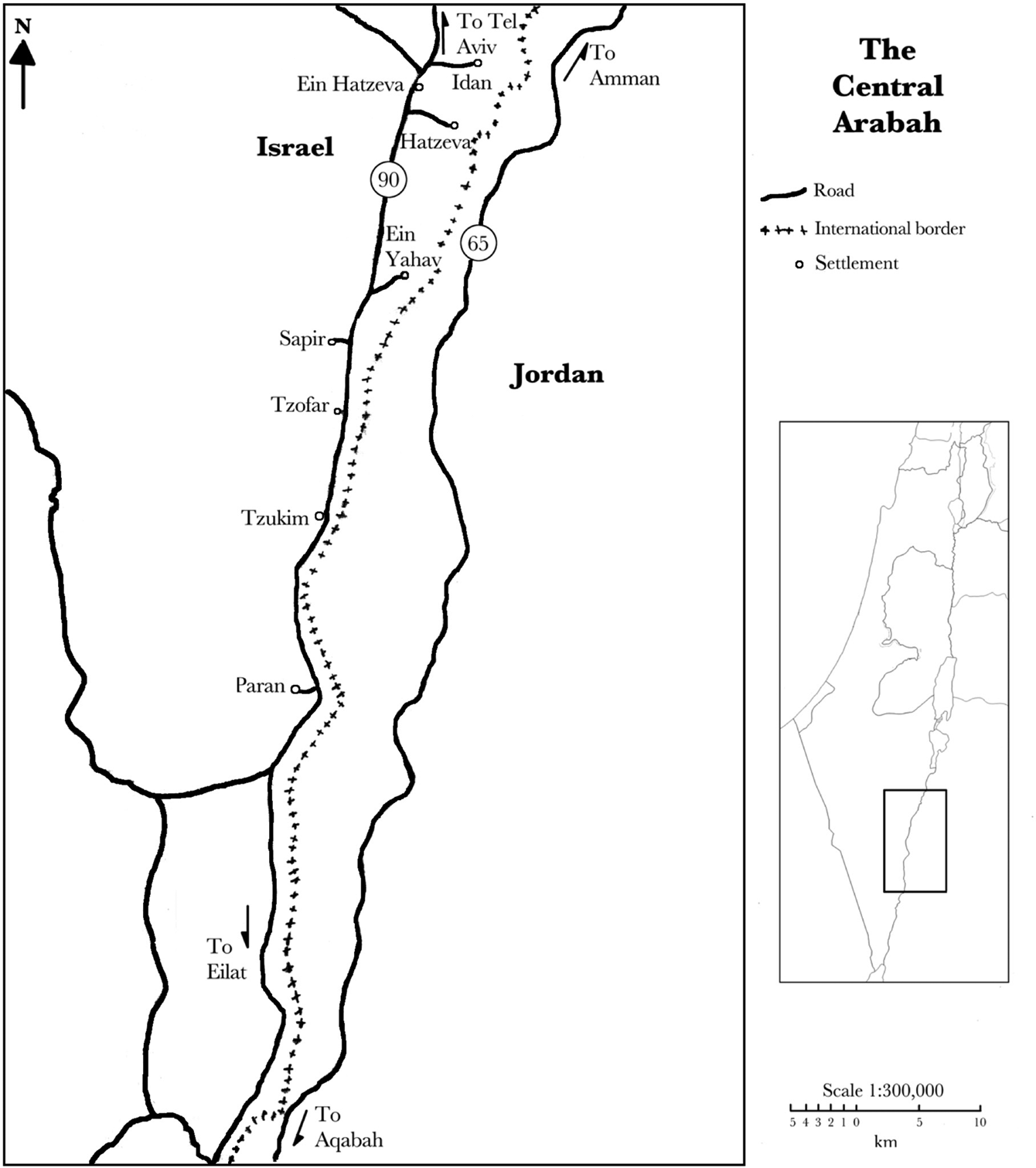

Forming the eastern edge of the Negev, the Arabah Valley is the part of the tectonic gap separating the central spine of Israel/Palestine from the Jordanian plateau which lies between the Dead Sea and the Red Sea (Map 1). The depression lies hundreds of meters below the Negev massif, which blocks the arrival of precipitation from the Mediterranean Sea; therefore, the valley is hyperarid and very hot for much of the year. A few times per winter, rainstorms break over the mountains astride the valley and their rushing waters flood the wadis, seeping into the ground and feeding a string of springs and oases.Footnote 20 The ecological keystone is the acacia tree, whose leaves feed the Nubian ibex and endemic Palestine gazelle, themselves once prey to leopards and wolves.

Map 1: The Arabah Valley (map designed by author).

Human occupation of the Arabah dates to the Paleolithic. The ancient Egyptians established the world's first copper mines here, and important trade and pilgrimage routes crossed the valley from the Roman to the early Islamic periods, waning in importance as sea transport developed.Footnote 21 But the valley was never abandoned. Researchers building on the firsthand knowledge of indigenous Arabah resident ‘Ali al-Misk uncovered a unique system channeling rainwater to fields through stone terracing, practiced in the region from ancient times until the Israeli takeover. In wet years the bedouin planted barley and wheat for human consumption, and in dry years animal feed was grown. Together with the threshing floors, livestock enclosures, and storage sheds discovered by the researchers, these constructed fields provide ample evidence of intervention in the environment to support a “smallholder, mixed crop-livestock” mode of production, with imported artifacts testifying to connections outside the region.Footnote 22 Bedouin control of the Arabah was complete throughout the Ottoman period, when the valley formed a rough border between tribal federations; European travelers avoided the area for fear of being caught up in their conflicts.Footnote 23

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 greatly facilitated shipment of goods from Asia to Europe and fueled imperial interest in the vicinity. After the imposition of Mandatory rule following World War I, the territories of Palestine and Transjordan were administratively separated, and the border was drawn down the center of the valley. The British attempted to rule the southland indirectly, through the establishment of a bedouin desert police corps. This policy had mixed results, with some policemen participating in the Arab revolt of 1936–39, but the posts established throughout the Arabah, from ‘Ayn Hosb in the north to Umm Rashrash on the Red Sea coast, were staffed until 1948.Footnote 24 In his History of Beersheba and Its Tribes, Palestinian historian ‘Arif al-‘Arif wrote that the Arabah, nicknamed “the wadi of fire” after the many victims of tribal warfare who had fallen there, belonged to the Sa‘idiyyin tribal federation.Footnote 25 A 1944 Zionist expedition gave a more detailed account, describing the valley as divided from south to north between the Ahaywat, Sa‘idiyyin, ‘Azazma, and Tiyaha federations, and estimating that at the yearly peak of occupation it was home to 15,500 goats, 7,800 camels, and 2,040 bedouin tents, probably sheltering about 10,000 people.Footnote 26

Zionism and the Desert

The common Zionist arraignment of the pastoral Arab as “father of the desert” has a venerable colonial pedigree.Footnote 27 Western visitors in the 19th century held to an imperialist theory of desertification that blamed Palestine's Arab residents and their herds for the country's supposed dessication. Up-to-date research, however, shows that land use patterns in the region were steady between the first and 19th centuries, although rangelands, unlike the temperate climates familiar to these visitors, experienced large variations in precipitation, which could cause drastic changes in the landscape's appearance. Despite this variability, “nonequilibrium” ecologies can support stable pastoral livelihoods. Without imported feed or water, herbivore populations shrink in dry years and do not threaten the ecosystem's survival; indeed, their removal can cause ecosystem degradation.Footnote 28 The tree surrounded by goats, a common motif in the country's traditional art, can be interpreted as representing this symbiosis between flora and fauna. Intriguingly, ancient art with a variation on this motif in which a shrub is surrounded by ibex has been discovered in the Arabah.Footnote 29

Although grounded in 19th-century discourse, Zionist ideas about “redemption of the land” have even deeper roots in the ideology of European expansionism. The doctrine of terra nullius, “no one's land,” was central to colonization of the Americas beginning in the late 17th century. For philosopher John Locke, “in the beginning all the world was America,” a primeval, unowned wilderness.Footnote 30 Locke reasoned that land could only become private property once man's labor of “improvement” molded it to his needs. This primal appropriation, however, need only be undertaken once; henceforth the land would belong to the initial cultivator and his heirs, whether or not they invested any additional work in it.

Strictly speaking, Locke's theory was not applicable even in North America, where anthropogenic “changes in the land” preceded European colonization by many centuries, although the indigenous people who transformed their surroundings generally made no individual property claims. But even where Native American cultivation entailed practices familiar to English settlers, such as plowing, the latter argued that by doing so “poorly” and without enclosing land into private parcels they forfeited their property rights.Footnote 31 Real improvement, for Locke and his followers, could be measured by success in producing surpluses for trade or taxation. But although “improvement” of this sort could generate handsome profits, it often destroyed the soil's vitality, catalyzing further colonial expansion.Footnote 32

By the late 19th century, this logic of improvement had become commonplace in Europe, and was taken for granted by the first Zionists, who hired cheap, skilled Palestinian peasants to work part-time on their privately owned farms. But among the settlers who began to arrive around 1904 were many poor young men of socialist tendencies, who could not hope to buy land or compete against the local workforce. Influenced as much by German romantic nationalism as by Marxism, their ideologists believed that sweat mixed into the soil established a property right, but they dissented from Locke by conceiving this right as pertaining to the nation rather than the individual, as well as by insisting on its perpetual reaffirmation through repeated investment of labor.Footnote 33 The employment of Arab wage laborers constituted a threat to this reaffirmation; hence the strong anxiety regarding the exploitation of indigenous labor that accompanied the settlement activity of the new generation.Footnote 34

The heads of the Zionist movement realized that without work young settlers would leave the countryside, if not the country, and colonization would stall. To generate agrarian incomes competitive with those available in alternative migration destinations, they resolved to fund the acquisition of land by “national” bodies such as the Jewish National Fund and capital investments that would enable commercial production without the use of hired Palestinian labor.Footnote 35 Among the various organizational forms attempted, the most initially successful was the kibbutz, a collective in which productive and reproductive labor were pooled, freeing members to undertake military tasks. One notch down the scale of vanguardism was the moshav, a cooperative settlement whose members worked their land separately but shared procurement and marketing arrangements to enjoy economies of scale.Footnote 36 Settlements of these two types became the symbolic heart of the “labor settlement” movement, which quickly rose to hegemony among the Jewish community in Palestine.Footnote 37 The economic role played in Zionism by “national” capital, deployed to take land off the free market rather than privatizing it, mirrored its ideological “religion of labor.”

It was the British who introduced a properly Lockean conception of land tenure into Palestine. Beginning in the 1920s, Mandate authorities undertook systematic land registration, encouraged the dismantling of musha‘ arrangements, and moved to grant landowners absolute “freehold,” including the right to evict tenant cultivators. The colonial authorities encouraged not only the cultivation of “wasteland,” but any transformation that would raise land's capacity to produce profitably. Here as elsewhere, the empire sought to encourage “market-oriented development and investment” to achieve “a more efficient revenue system and an enhanced tax base.”Footnote 38

Mandatory policy favored the Zionists by subsidizing capital investment in agriculture and facilitating the eviction of tenants from their newly acquired tracts. These tracts, bought mostly from large landowners such as the Sursuqs, were concentrated in low-lying, marshy, and sandy areas. Their inhabitants, many of them traditionally stigmatized herders and foragers, were forced out as settlers undertook ecological transformations such as wetland drainage, soon to become a common Zionist metaphor for the “healing of the nation.”Footnote 39 But these evictions fueled the nascent Palestinian nationalist movement, strengthening villagers’ resolve to maintain musha‘ arrangements intact and prompting leaders such as ‘Arif al-‘Arif and Haj Amin al-Husayni to formulate an anti-colonial Palestinian “agro-nationalism.”Footnote 40 From the Zionist perspective, a more serious drawback to the land market was skyrocketing prices, due to which the movement was able to acquire no more than 7 percent of Palestine's territory before 1948. This territory was almost exclusively in the lowlands, creating the distinctive geographic N shape of Zionist holdings that linked the coast, the Jezreel Valley, and the upper Jordan Valley.Footnote 41 In the hill country and the drylands, the tenure of the fellahin and bedouin remained mostly intact, and olive cultivation remains a crucial strategy for resisting Israeli encroachment in the West Bank today.Footnote 42

Ecological questions came to the fore in the 1930s in the debate on Palestine's “absorptive capacity.” Mandate officials and Palestinian nationalists interested in limiting Jewish immigration pointed to the country's limited water and land resources, prompting the Zionist leadership to turn its interest to the possibility of “improving” lands through grand ecological transformations such as the diversion of water from the Jordan basin to the Negev, where Jewish settlements were first established in the early 1940s.Footnote 43 The 1937 Peel Commission's partition plan, which assigned the entire country south of Jerusalem to a future Arab state, split British officialdom, with influential officers arguing that only the Jews could make proper use of the desert.Footnote 44 This view won over the UN Special Committee on Palestine, which justified its assignment of the entire Negev to the Jewish state in its 1947 partition plan by the logic of improvement, arguing that its “sparsely populated” parts could be developed through “heavy investment of capital and labour and without impairing the future . . . of the existing Bedouin population.”Footnote 45

The bottleneck facing Zionist colonization was finally broken during the war of 1948–49, when around 700,000 Palestinians were forced to leave their homes in the mass expulsion known as the Nakba, and their lands were confiscated by the new state.Footnote 46 Immediately after independence, the newly constituted Israeli authorities set about undertaking ecological transformations at a dramatic new scale. The wetlands of the Hula Valley in the upper reaches of the Jordan basin were drained, and indigenous foragers were deported.Footnote 47 The immense National Water Carrier, completed in 1964, fulfilled the fantasies of the 1930s by exporting immense quantities of water from the Jordan to coastal urban centers and the agricultural frontier of the northern Negev at the expense of the population of the lower Jordan basin, including the refugees who had escaped there.Footnote 48

The 1950s and early 1960s were a period of rapid expansion for the agrarian settlements, as generous state support was allocated to step up production to meet the needs of the growing population. Throwing self-labor to the wind, kibbutzim and moshavim began to employ the remaining Palestinians, now Israeli citizens under military rule, and Jewish immigrants of Middle Eastern origin (Mizrahim) who had been settled in peripheral “development towns” with no land of their own.Footnote 49 Other Mizrahim were semi-forcibly settled in new moshavim, which were considered appropriate for their “premodern culture,” whereas veteran kibbutzim plowed profits into industrialization, producing new ethnic and economic inequalities within the labor settlement movement.Footnote 50 But the new reality ran directly counter to the tenets upon which the movement had staked its claim to moral supremacy, triggering an ideological crisis among veteran settlers. One group of youth reacted by pledging to rejuvenate the movement's principles far from the temptations of cheap labor, deep in the desert: a new terra nullius on the frontier.

The Israeli Settlement of the Arabah

Intense fighting between Israeli and Egyptian armies began in the area between Gaza and Beersheba immediately after Israel's declaration of independence in May 1948, but the deep south was only conquered in March 1949 when the Israel Defense Forces swept to Umm Rashrash, forcing the bedouin along the way over the Jordanian border.Footnote 51 Following the war, much of the Negev's remaining bedouin population was expelled, and most of those remaining were concentrated in a reservation area east of Beersheba. Ever since, the struggle of the Negev bedouin to retain their land and resist forced urbanization has hinged on their ability to “prove” consistent cultivation to a hostile agro-nationalist state, ready to use the flexibility necessary for survival in nonequilibrium rangelands against them to deny their claims.Footnote 52

Following the war agrarian settlements were set up quickly around Beersheba, but not in the Central Arabah, where land improvement appeared both financially unfeasible and strategically unnecessary. Israeli leaders’ interest in the region focused on its outlet to the Red Sea, through which they hoped to forge trade links with Asia. But the opening of the port of Eilat in 1955 and the establishment of a few kibbutzim in its hinterland, at the Arabah's southern end, devolved strategic importance onto the routes connecting Eilat to the country's center. Fearing “infiltration” by the deported bedouin and Palestinian fighters, the IDF placed the region under military administration and established bases at the former British police posts.Footnote 53 In 1953, the bedouin al-Misk and ‘Amrani families of the Sa'idiyyin federation were allowed to return from Jordan and settle near ‘Ayn Hosb in return for their military services, which included patrolling the border.Footnote 54

Zoologist Giora Ilani, who served as a military wireless operator at ‘Ayn Hosb in 1956 and later settled in the Arabah, provides an account of the post in which wonder at the area's natural splendor clashes with disgust at the army's destructive relation to the environment:

the limestone mountainside sloped wildly towards Wadi Fuqra . . . dotted with tamarisks and acacias. . . . To the north, the gray eminence of mesquite, seepweed and nitre-bush dominated the landscape . . . ample trees — twisted acacia, umbrella thorn acacia, and even Christ's thorn jujube — grew and cast their gladdening shade across the land, but the jewel in the crown was the hundreds of desert gazelles. . . . Abu Ghanim and his friends estimated the distance to the camp at ‘Ayn Hosb, and after ascertaining that no one would hear the shots, tried to kill as many gazelles as they could. The gazelles had learned from experience to run out of the rifles’ range, so I could only see them from afar. . . . [The soldiers] smiled apologetically after missing their shots; they promised me that at night they would kill as many gazelles as they wished using spotlights.Footnote 55

These Druze soldiers also served as hunting guides for high-ranking Jewish officers, who had “learned to enjoy free hunting” when serving “in the British Army in the Western Desert and North Africa.” Ten gazelles were turned over to the camp's cook every week, but others were killed in such a reckless way as to render their carcasses unfit for consumption.Footnote 56

The Arabah might have remained a safari destination for military brass if it were not for the intervention of Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, who saw moral as well as strategic danger in leaving the deep Negev devoid of permanent Jewish presence. The running battle between the “voluntarist” Ben-Gurion and cabinet “pragmatists” was not over the need to anchor settlement in commodity production, which both took for granted, but over the expenses which the developmentalist state could afford to incur to establish its preconditions. Ben-Gurion's initial efforts to settle the deep south were unsuccessful, but the tide began to turn when a group of youth intent on settling in the Arabah approached him in 1955.Footnote 57 Mostly children of veteran moshavim, they wished to retain this settlement form despite the frontier location, which the authorities saw as more suitable for kibbutzim. At Ben-Gurion's behest, the Central Arabah's first Jewish settlement, Ein Yahav, was established as a NAHAL outpost (he'ahzut), and in 1962 was transferred to civilian control, becoming a moshav.Footnote 58

Near the point where a major tributary entered the Wadi Arabah, Ein Yahav had relatively good access to water, but it also was one of the remotest spots in the country: 125 kilometers from both Eilat and Jerusalem as the crow flies, distant from both consumers and much of the requisite infrastructure. But despite the initial reticence of the authorities, once the settlement had become a “fact on the ground” they committed to financing this infrastructure, and other moshavim rapidly followed suit: Hatzeva in 1965, Paran in 1971, Tsofar in 1976, and Idan in 1980. The bedouin families who returned to the Arabah, however, remain unrecognized squatters on their land despite their loyal service to the state.Footnote 59

After a short period of experimentation, the settlers and their government advisers decided to focus on vegetable cultivation. Existing springs could not provide anything like the amounts of water needed, so the deep, ancient, and non-renewing aquifers below the valley were tapped, and the region was gradually covered by a grid of wells, pipes, and reservoirs.Footnote 60 Due to the extreme salinity and compactness of the ground, soil appropriate for growing vegetables was imported. The moshavim enjoyed cheap state-sponsored credit and production quotas, as well as the fruits of state-funded research, including the technological breakthrough of drip irrigation. Finally, the section of Israel Route 90 connecting Sdom to Eilat, completed in 1967, enabled trucks to quickly and cheaply bring the region's produce to the country's centers of population.

Once augmented by water, soil, technology, and road links, the horticulture of the Central Arabah enjoyed a competitive advantage in a protected produce market. High temperatures enabled the wintertime cultivation of tomatoes, cucumbers, and bell peppers, which drew high off-season prices, and local farmers earned enough by working hard in the cool months to rest during the broiling summers. Due to this seasonal rhythm and the commitment to self-labor, bolstered by the absence of available labor power nearby, at peak times all members of the community had to lend a hand: women and children worked in the fields beside men, often aided by volunteers from the global North attracted to the socialist ideals and clean living associated with Israeli labor settlement in this period.Footnote 61 In short, a unique combination of climatic, political, and economic factors enabled self-labor to retain its hold in the Arabah for a full generation. Although this principle had run its course in the heartland, the Arabah showed that it could still be fruitfully deployed on the frontier.

The Crisis of Labor Settlement and the “Thai Revolution”

Colonization of the territories occupied by Israel in 1967 at first followed the traditional labor settlement approach, aiming to prevent demographic contiguity between Palestinians and the surrounding Arab states through the agricultural settlement of their outer perimeter. But the debacle of the war of 1973, when Syrian and Egyptian forces temporarily reconquered parts of these territories, spelled the beginning of the end for labor settlement. After the election of Likud leader Menachem Begin to the premiership in 1977, a new generation of settlements was established in the West Bank's mountainous heart with a view to preventing contiguity between Palestinian centers of population through suburban sprawl.Footnote 62 Since then, the commuter-oriented, non-agrarian “community settlement” has become the most common archetype for new settlements in the West Bank as well as Palestinian-majority areas within Israel proper.Footnote 63 In recent years, the vanguard of West Bank settlers has rediscovered the strategic and ideological uses of agriculture, but farming remains a negligible source of livelihood for Israelis residing in the Occupied Territories.Footnote 64

Following an inflation crisis under Begin's administration, a “national unity” government including the Labor Party enacted the neoliberal Economic Stabilization Plan. In sync with the changing interests of its urban, middle-class constituents, Labor embraced the free market and a fiscal discipline that for the first time extended to the favorite sons of the agrarian sector. Kibbutz and moshav members near urban centers could look forward to converting their holdings into lucrative residential properties, but others, including the settlers of the Arabah, had no such option. As state backing for agricultural credit was withdrawn, cooperative marketing and financial arrangements broke down, forcing neighboring farms into competition with one another.Footnote 65 Vegetable cultivation in particular was labor-intensive, and the new cutthroat competition made cheap labor imperative. Such labor had long been available to Israeli employers in the form of the noncitizen Palestinians of the Occupied Territories, but in 1987 this group rose up in the first intifada, which encompassed workplace actions ranging from rallies and strikes to attacks on employers.Footnote 66 The numbers of foreign volunteers also dwindled following the atrocities of the Lebanon War and the intifada. As farmers dependent on Palestinian labor scrambled to adjust, the settlers of the Central Arabah might have felt confirmed in their insistence on self-labor, but they felt the new hunger for cheap labor as acutely as anyone else.Footnote 67

The solution emerged from an unexpected source. Since the 1950s, Israel had sought to exert soft power in the Third World by exporting its models of agricultural settlement, including a royally sponsored agricultural cooperative in Thailand.Footnote 68 Such efforts had been scaled back by the 1980s, but when the Thai military regime reached out for assistance in training cadres for agrarian settlement on its volatile Cambodian frontier, Israeli diplomats agreed. In 1987, Thai soldiers and civilians began arriving in Israel, including the Arabah, for courses of agricultural “training.” Private middlemen in both countries quickly intercalated themselves into the process, taking a cut of the cash “allowances” on offer.Footnote 69 Meanwhile, the Labor government elected in 1992 responded to the intifada by embarking on the Oslo negotiation process. Its strategic objective was to achieve “separation,” which included weaning the Israeli economy of its compromising dependence on Palestinian labor, especially in the construction and agriculture sectors. By this time, farmers already had a substitute workforce at hand. Their organizations lobbied to extend the existing “training” programs, and within a few years over twenty thousand Thais were working Israel's fields, as they do to this day.Footnote 70

The influx of Thai workers revolutionized the Central Arabah. From 1989 to 1999, as children came of age and left the region, its Israeli population fell from around 6,000 to 2,100, only climbing back to 3,200 in 2016 with the growth of a third generation. But by 2013, the numbers of local Thais had reached 3,212—roughly half the total population. The 1994 peace treaty with Jordan enabled the cultivation of new fields, and from 1988 to 1999 the area under cultivation in the Central Arabah rose by 32 percent. The share of this area covered by labor- and water-intensive greenhouses leapt from 4 to 41 percent, and from 1991 to 2000 water use almost doubled. Bell peppers for export jumped from 6 to 26 percent of the crop, pushing out the range of vegetables previously produced for local markets.Footnote 71 After a long boom followed by a few disastrous seasons, this monocultural trend was partially reversed, with dates rising to compete with peppers for primacy. Nevertheless, statistical summaries of the 2017–18 and 2018–19 growing seasons reveal that 31 percent of the region's cultivation area remains devoted to the bell pepper crop.Footnote 72

Competition in European markets, where other producers also had access to the cheap labor power of disenfranchised migrants, heightened the dependence of Arabah farmers on a low wage bill.Footnote 73 Although on paper Thai migrants are entitled to the same protections as Israeli citizens, in practice the government tolerates gross violations of their legal rights.Footnote 74 In 2016, the minimum wage was 25 Israeli new shekels (US $6.33) per hour, but the prevailing wage for Thais in the Arabah was much lower, around 18 NIS per regular hour and 22 NIS for overtime, including on days longer than the legal maximum.Footnote 75 Wages were docked in legally dubious ways, peripherals like severance pay denied, and pay slips falsified. Health and safety regulations and stipulations on housing quality were flouted.Footnote 76

While the state serves employers by ignoring legal labor protections, it also enlists them as enforcers of its draconian immigration policy: employers whose workers leave their posts or stay in Israel beyond the five-year limit are punished by having their employee quotas docked. But farmers also cite the temporariness of employment relations as a justification for continued state support. Thus, in a lobbying document arguing for the enlargement of employment quotas, the Central Arava Regional Council declared that the “behavioral norms” of local migrants “do not include intermarriage, childbirth and lengthy periods of illegal residence in the country.”Footnote 77 The informal employment of bedouin women and teenagers from other parts of the Negev, which I witnessed during my fieldwork without being able to learn much about it, is passed over in silence.

Ideological disavowals notwithstanding, the shift from self-labor to dependence on migrant workers has had profound social consequences. At first, Thai “trainees” lived with their employers and formed intimate paternalistic relationships that were often replicated as employers recruited new workers from among the friends and family of veteran ones. At first, they were fitted into the institutional slots created for overseas volunteers, with “volunteer” even becoming a common euphemism for their status.Footnote 78 But as the number of migrants has grown, and especially since the 2012 bilateral agreement that randomized the matching of workers to employers to prevent fee extortion by middlemen, such ties have grown weaker. Today, employees live in segregated quarters and form self-contained communities that manage their domestic lives along Thai norms of age and seniority. Most employers no longer do any manual work and often leave even the allocation of tasks to Thai foremen. Women have mostly been pushed out of agricultural work, and the children who were once expected to lend a hand now often “don't even know where Dad's fields are,” as the local cliché goes.Footnote 79

Political-ecological Futures of the Arabah

The “Thai revolution” that engulfed the Central Arabah over the last generation is in many ways a Marxian textbook case of capitalist dynamics. Advances in technology, transport, and trade have minimized the labor required to bring a kilogram of peppers to market, but instead of freeing producers from drudgery, this has triggered intensified competition and lower prices, forcing farmers to expand production and push down wages to stay profitable. This open-ended expansion accelerates the consumption of natural resources and the degradation of the environment, placing impossible pressures on the metabolism that links humans to the earth. In the Arabah, a climatically extreme zone that nevertheless has managed to support human life for millennia, the metabolic rift has become a yawning abyss that threatens to wipe out the conditions for agricultural production in the near future.

So far, public opposition to the environmental damage caused by Arabah farms has focused on the destruction of trees resulting from their expansion.Footnote 80 But the degradation of water sources endangers the local ecosystem as much as this sprawl. Unlike the bedouin subsistence economy, which supplied nourishment to humans and domestic animals without upsetting the water balance, the capitalist agriculture currently practiced in the Arabah effectively exports huge amounts of water from this thirsty region to much better-watered quarters of the globe. As water is extracted, aquifers become saline and silty, necessitating expensive repairs to drilling equipment and new boreholes. Agricultural runoff pollutes the reserves, whose water must be subjected to energy-intensive treatment to be fit for irrigation, not to mention drinking. Following the retreat of the water table, eighteen of thirty-one springs on the Israeli side of the Arabah have run dry, and monitoring stations on both sides of the border show increasing aridity. Farmers are well aware of the deterioration in water quality and note its negative effects on production.Footnote 81

Broader processes also cast doubt on the continued viability of settlement in the Arabah. The International Organization of Migration, charged with recruitment by the 2012 bilateral agreement, requested in 2019 that some of the fees still paid by migrants be assumed by their employers. When this demand was dismissed, the IOM announced its departure from the arrangement beginning in July 2020.Footnote 82 The possibility of a return to fee extortion, together with the emergence of alternative migration destinations and the disruption caused by the coronavirus pandemic, all point to the increasing risks of dependence on a flow of laboring bodies from abroad.Footnote 83 Finally, there is the growing threat of global heating, which up-to-date models predict will bring a “pronounced increase in the mean temperature . . . with peaks of up to ~2.5 [degrees] C” to Israel/Palestine over the coming decades.Footnote 84 Its impact can already be felt in the Arabah, where precipitation levels declined over the thirty years preceding 2009.Footnote 85

Even given these trends, it is difficult to declare the fate of agriculture in the Arabah sealed. As Gökçe Günel argues in her ethnography of climate entrepreneurship in the United Arab Emirates, capitalist states prefer spending immense sums on “technical adjustments” that defer and externalize ecological damage over undertaking structural economic transformations that may bring political upheaval.Footnote 86 A state “master plan for water in the Arabah,” now in an advanced stage of implementation, promises to meet the region's water needs by importing desalinated water from the Red and Mediterranean Seas. By 2030, new pipes are expected to provide up to 30 million cubic meters of irrigation-grade water per year, at a total cost of over half a billion NIS. The energy cost of about 40 million kilowatt-hours per year will be met by Israel's power grid, which remains heavily dependent on nonrenewable energy sources.Footnote 87 Such fossil fuel–powered desalination, which responds to water scarcity by releasing thousands of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and exacerbating the global metabolic rift, is “technical adjustment” par excellence.

The alternative would appear to be to begin winding down the cash-crop production upon which the Israeli and Thai residents of the Central Arabah currently depend for their livelihoods. Although the regional leadership has taken steps to diversify the economy in recent years, investing in tourism and attempting to attract work-from-home professionals to settle, these are dubious replacements for farming as an economic mainstay. Might ecological sustainability demand the depopulation of the Arabah? Even raising this question constitutes a breach of the Israeli taboo on “evacuation of settlements.” Although usually invoked to prevent territorial compromise in the West Bank, the taboo applies a fortiori to Jewish settlements inside Israel proper — although it does not apply at all to the “unrecognized” villages of the state's bedouin citizens, which are continually under threat of liquidation.Footnote 88 From the perspective of the colonizers, at least, dismantling the settlements of the Arabah would be tantamount to decolonization.

But although the Arabah supported a population of the same order of magnitude in 1944 as it does today, decolonization cannot take the form of reversion to the mixed agricultural-pastoral mode of production formerly practiced by local bedouin. Given the recession of the water table and the rise in temperature and rainfall volatility, this mode of production has probably become impossible.Footnote 89 Moreover, as for Palestinian farmers in northern Israel forced by state discrimination to use traditional methods, nostalgic ecologism can easily serve as cover for dispossession and impoverishment.Footnote 90 If humans are to continue living in the Arabah, they will have to do so in what Anna Tsing calls the “ruins” of capitalism, making use of all that has gone before to forge something new rather than attempting to turn back time.Footnote 91 But unlike the disturbed pine forests Tsing discusses, where marginalized people have found opportunities by harvesting mushrooms for the plates of wealthy Japanese diners, the desiccating Arabah possesses no obvious comparative advantage. The copious sunlight it receives could be a basis for solar power production, but many local environmentalists oppose solar-power buildup in the area as a threat to the Negev's unusual biodiversity.Footnote 92

Perhaps the Arabah should be left to the acacias and the gazelles then? I do not see why the possibility should be rejected out of hand, but this is not the place to decide the question. Meaningful decolonization would entail a democratic decision-making process involving not only trustees of the region's nonhuman species and leaders of the settler population, but also the Thai migrants who have labored here for thirty years and the indigenous bedouin who have been excluded from their homeland for over seventy. By including actors whose relation to the land is so different from that of the Israeli settlers, such a broad deliberative process might throw up new possibilities. Inklings of these possibilities may be found in the vegetable gardens cultivated by Thai migrants for personal use in greenhouse corners and barrack yards, or among the bedouin who have found ways to grow cannabis in wadis far from the eye of the state, and obviously without its assistance.Footnote 93

The remote, hyperarid, agrarian Arabah certainly cannot be taken as typical of Israel/Palestine, whose dense, overwhelmingly urban population clusters in different climate zones. It is informative, rather, as an ecological and political-economic edge-case demonstrating what Zionist colonization has been able to achieve while operating within the constraints of the capitalist mode of production. Moral strictures notwithstanding, the achievement is impressive: with advanced technology, untrammeled access to underground water, and cheap labor power imported from the other end of Asia, the farmers of the Arabah have fulfilled the Zionist dream, turning the desert green while making a profit. But their garden is built on shifting sands. Israel's founders, including the voluntarist Ben-Gurion, took profitability for granted as the ultimate test of viability, and although their concern with ground-level territorial control has been replaced by an obsession with information technology and surveillance, this assumption remains fundamental to the ruling ideology.Footnote 94 Yet the edge-case of the Arabah points in the opposite direction: it is precisely the capitalist nature of the colonial project as practiced here that threatens to render the environment unlivable, and only the prospect of a noncapitalist, democratic decolonization offers hope for sustainability. This is a remote place, with a small population, but it would be foolish to imagine that what happens here has no bearing on other parts of Israel/Palestine, or indeed on any part of the world where capitalism and colonialism march hand in hand, destroying human and nonhuman lives as they go.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Joel Beinin, Basma Fahoum, Eyal Goldstein, Natalia Gutkowski, Geoffrey Hughes, Ofri Ilany, Zachary Lockman, and Andrew Shryock, as well as editor Joel Gordon and the three anonymous reviewers at IJMES, for their valuable feedback on various versions of this article.