I became aware of the action films al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad, both starring Muhammad Ramadan, as I chatted with a sixty-something middle-class driver while stuck in a Cairo traffic jam near an overpass in early 2014 during field research on gender, violence, and space in postrevolutionary Egypt.Footnote 1 The driver gestured toward a movie billboard depicting a muscular shirtless young man (Ramadan) and mentioned the rise of baltagi (thug) films made by “Sobky.” The chauffeur complained that Subki films encouraged immorality and violence even as they were wildly popular among young men. Press stories confirmed his critiques of the crass and low-class nature of the Subki family and their films.Footnote 2 A campaign in 2013 even called for the boycott of Subki films, arguing they legitimated the insult, degradation, and rape of women.Footnote 3 Hassan al-Subki is a wealthy butcher whose sons Muhammad and Ahmad opened a video club above their father's shop in Dokki, Cairo, in 1985 to market foreign films with wide appeal. The club reportedly became the largest such company in the Middle East.Footnote 4 In the early 1990s, the brothers started prolifically producing their own films under the name Sobky Film Productions (al-Subki lil-Intaj al-Sinima'i). Over the years, the film company incorporated women and male relatives in different aspects of production and experienced widely discussed breakups and creative disputes.Footnote 5

I asked two DVD/CD street vendors in different locations in downtown Cairo for “Subki thug films” in the days that followed my conversation with the driver and ultimately purchased six they considered significant. Most turned out to be of terrible quality because they were illicit recordings made during a cinema showing and included audience titters and blocked scenes as a viewer stood up or walked in front of the screen. Only four of the six vendors’ choices were in fact Subki productions (which the family spells “El Sobky” in English) and three of the six were action films starring Ramadan as a low-level criminal. This article examines the two most-mentioned Ramadan thug films, al-Almani (The German, 2012) and Qalb al-Asad (Lion Heart, 2013), which I watched multiple times, relying on reasonable-quality online and purchased versions. I argue that these immensely popular films express a “structure of feeling” about change after the 25 January 2011 revolution and are symptomatic of political tensions and anxieties that permeated Egyptian society at the times of their release.Footnote 6

Al-Almani, released on 26 July 2012, was the first blockbuster film after the January 25 Revolution and made Muhammad Ramadan a superstar. Written and directed by `Ala’ al-Sharif and produced by Ahmad al-Sarsawi, it was not a Subki production despite being popularly categorized in that genre. Promotional material describe it to be about “the hidden secrets of thug life in Egypt” (al-asrar al-khafiyya li-hayat al-baltagiyya fi Misr). Indeed, masculine thuggery is central to the narrative, as many men and women in the film work below the threshold of legality in the neighborhood's alleys and apartments. Qalb al-Asad, a fast-paced Subki action thriller also starring Ramadan, was released in the tumultuous summer of 2013, on 7 August, the `Id al-Fitr holiday, a month after the 3 July military coup led by General `Abd el-Fattah al-Sisi that overthrew the elected government of Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood. At its center is a more sympathetic proletarian masculine protagonist who negotiates survival by using his wit, friendships, and criminal skills in the informal economy.

The other four recommended productions I viewed were Shari` al-Haram (Pyramids Street), a Subki comedy released on 30 August 2011 for `Id al-Fitr that starred the performer Dina as a dancer being pursued by three lovers.Footnote 7 I also was pointed to al-Khawaja `Abd al-Qadir (The Foreigner `Abd al-Qadir), a popular non-Subki drama released as a television series in early 2012.Footnote 8 The third film, `Abduh Mawta (`Abdo Mawta), was a Subki production released in October 2012. The protagonist is a violent baltagi (played by Ramadan) who sells drugs after he loses his parents in unknown circumstances. He imposes his will on the neighborhood and plays against each other two women in love with him, a good and a bad girl, following Egyptian genre conventions.Footnote 9 The last film mentioned, Sa`a wa-Nisf (One-and-a-Half Hours), was a Subki drama also released in October 2012 in which Ramadan played a small role. This suspenseful and beautifully shot film stages everyday conversations, interactions, and conflicts among individuals from many backgrounds and generations at multiple stops as they catch the southbound train from Cairo during the February 2002 `Id al-Adha holiday in the hour and a half before they are killed or injured in the `Ayyat train disaster.Footnote 10

The next section expands on the plot lines of al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad, considers them in an Egyptian cinematic context, and situates Muhammad Ramadan as a performer. The section that follows details how the films deploy and undermine morality and respectability tropes in relation to work, sexuality, and family life, staging the failure of such masculinities and femininities. The third section analyzes the resonant thug figure as a masculine subject and target of state control and violence in Egyptian cinema and society. Using a close reading method, I argue that al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad present the armed masculine sovereignty of the state—the police—in salutary yet ambivalent terms. The fourth section examines the political impulses in the content and form of the films. It shows that each film expresses class injury and traces of revolutionary upheaval and nostalgia. Nevertheless, cynicism rather than hopefulness dominates, especially in al-Almani, which conveys to the middle and upper classes the specter of an ever-present threat of masculine frustration and violence that takes the path of force. The form and content of Qalb al-Asad, in contrast, offer the option of reconciling opposing elements: the possibility of an Egyptian story line with a less repressive conclusion if one takes a path between revolutionary resistance and accepting defeat.

Situating Plots, Cinematic Context, and Muhammad Ramadan

Al-Almani (Fig. 1) begins with Shahin Almani (Ramadan) confronting and killing a young man in a dark alley. Shahin steals the man's shiny black leather jacket and smartphone and stabs him when he tries to retrieve them. This scene is recorded in a high-angle shot that imitates a CCTV camera and ends with Shahin sardonically commenting, “I'll count you a martyr,” before he stares up at the surveillance camera and runs. Ranya, a young television news host, reports in studio on the “unfortunate,” “ugly,” and “upsetting” video segment “revealing that the story of the thug continues.” The footage alternates with shots of Shahin's neighbors watching the same television news segment in horror as a running caption reads, “Real video of a thug attacking Ahmad al-Shabab.”Footnote 11 The remainder of the film is in flashback and flash-forward form.

Figure 1. Al-Almani official movie poster. Courtesy of https://elcinema.com/en/press/678926810.

We learn that Shahin's mother Shadya was left by her husband when she was pregnant with Shahin. For a few years she made a good income working with a midwife, housing girls and women who became pregnant out of wedlock in her apartment until they gave birth. Shadya sent the young Shahin to apprentice in a car repair garage where the owner nicknames him “al-Almani” (the German) for his meticulous and conscientious work. Interestingly, Germany also comes up in Qalb al-Asad as a sign of modernity and quality when the protagonist Faris somewhat absurdly, given his ordinary lower-class position, professes to his girlfriend's hospitalized mother that he would send her to Germany for treatment if it weren't for the economic crisis in Egypt. I attribute these references to an Egyptian history that associates Germany with science and quality production, particularly of machines. During the Cold War, West Germany and East Germany actively competed in the Egyptian marketplace to be the legitimate heirs of their country's “quality design and workmanship” reputation, while dissociating themselves from the Nazi past.Footnote 12

Shahin's mother Shadya thrives running the illicit maternity ward until she cuts out the midwife, who hires men to beat and rob her in front of the preadolescent Shahin. Shadya graduates to selling stolen appliances and electronics that she encourages the now older Shahin to steal. Shahin's work also includes collecting debts for high-interest moneylenders in the neighborhood. Like his friends, he persistently looks for ways to make money and uses violence as necessary. Shadya and Shahin live in an apartment in the same building as the righteous Habiba and her father Salih, a widowed man who owns a small neighborhood gift shop. Shahin falls in love with Habiba, who works in her father's shop in the afternoons. He also is in a relationship with bad girl Sabah, a sex worker at the local brothel. Shahin provides “protection” to the brothel, although he is, in actuality, a significant source of their trouble. The film ends on a dark evening with the grieving Salih wailing over his daughter Habiba's body in an alley. Shahin's friend Asli kills Habiba to steal from her the substantial amount of money Shadya has asked her to deliver to facilitate Shahin's escape from the law after he robbed and killed Ahmad.

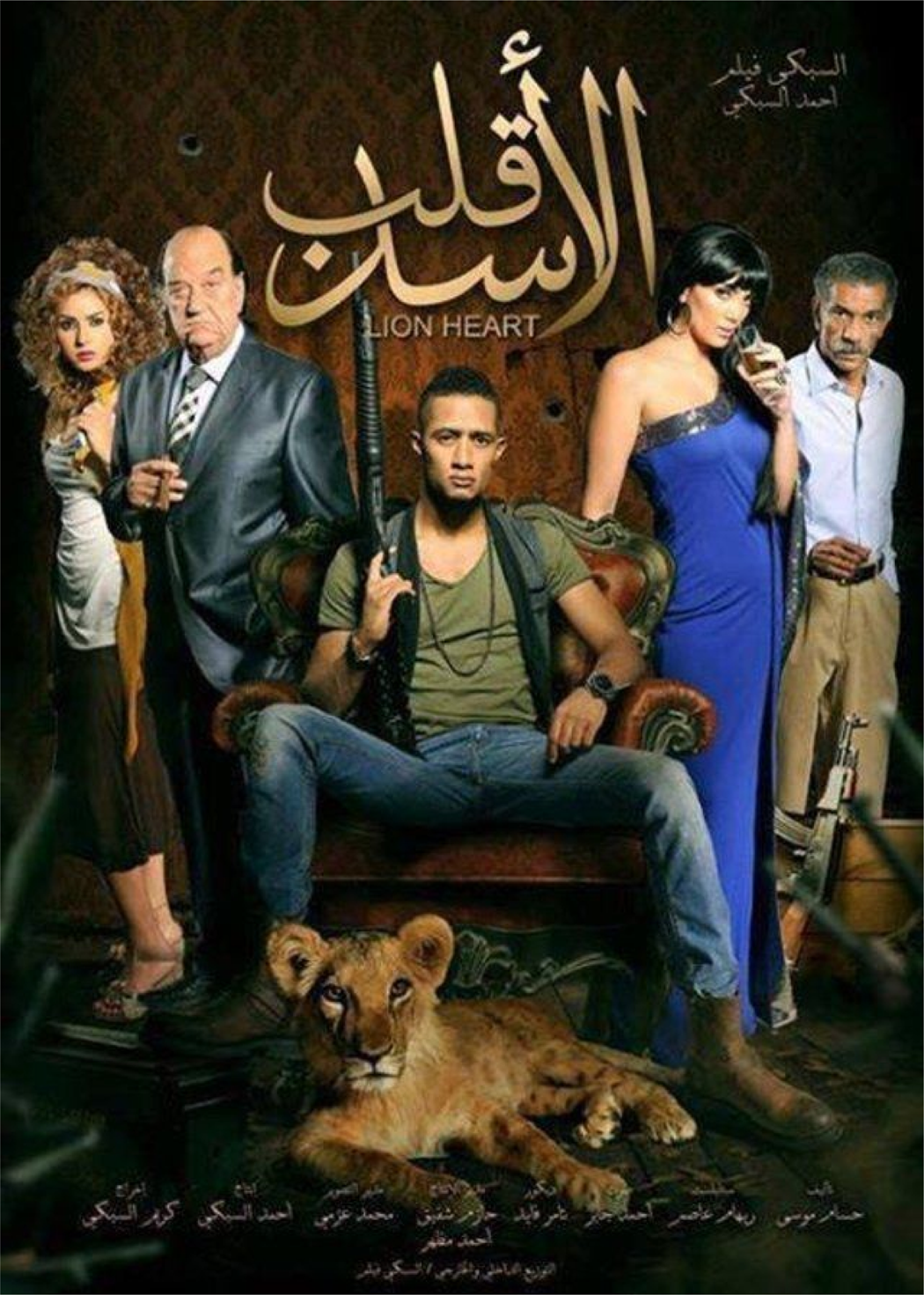

Qalb al-Asad (2013; Fig. 2), which includes multiple car chases in black SUVs and was obviously a more expensive production, begins with a slow-motion scene in which a bloody gun-wielding Faris al-Ginn (Ramadan) faces off against an armed corrupt prosecutor on a summer night in a courtyard outside a mansion on the outskirts of Cairo. As in al-Almani, most of the film is narrated in flashback, beginning with an iconic moment of violence between men. We learn that Faris was born Faris `Abd Allah al-Sawwaf to a modestly middle-class family, as indicated by the family apartment and furnishings and the little boy's clothing. When Faris was about eight years old, Ziham, a drug addict, abducted him while his blind father was pushing him on a park swing. In the scene, his father calls out to Faris when he realizes he is no longer on the swing. A slow shot shows the boy looking back at him in silence as Zinham walks him away. The plan was to sell the child to a family, but his partner in crime, Zinat, deems him too old, encouraging Zinham to “adopt him yourself, make him your son, to work and clean for you since you are cut off from a tree [you have no family].” Zinham keeps the boy, renames him Faris al-Ginn and puts him to work cleaning and training circus animals.

Figure 2. Qalb al-Asad movie poster. Courtesy of https://elcinema.com/en/press/678933786.

Faris continues this circus work into adulthood, but also works as a thief, living with his proto-father in a Giza neighborhood not far from the pyramids.Footnote 13 The plot turns when a twenty-something Faris breaks into an SUV to steal a Blackberry and expensive watch owned by Salim Bey, a grossly wealthy politician alternatively referred to as a minister and a parliamentarian.Footnote 14 Until the final scenes, Salim has parliamentary immunity (hasana), which he exploits for a weapons-running business. After the break-in, Salim's bodyguards initiate a lengthy chase on foot and by car, and a street battle with Faris ensues. Although Faris gets away, a bodyguard photographs him. Salim Bey is concerned that the stolen smartphone includes contacts and other information regarding his shady dealings and demands that his bodyguards find Faris. They kidnap him and his friend Masala and torture them in the garage of Salim's compound in a series of violent scenes. Faris escapes the garage but cannot exit the gated mansion compound, so he takes Salim's lover Nana hostage from her bedroom to secure his release. Salim learns that Faris sold the phone to pay part of the private hospital bill for his fiancé Ruqayya's mother. He retrieves the phone and hires Faris and Masala to work in his weapons-running business, convincing them it is much more lucrative than petty theft. He also gives Faris a wad of cash to pay the remainder of the hospital bill. At the end of the film, an incorruptible police officer, `Issam, arrests (the injured) Salim Bey. `Issam turns out to be Faris's biological first cousin, and he reconnects Faris with his long-lost biological father.

Animals are ubiquitous in Qalb al-Asad, adding an effective quality of surrealism to the film: a young black filly we see once runs through a neighborhood alley past Faris, startling him. A beautiful cat with its tail stiffly up walks past an open door in another room, larger than life in Zinat's ground floor apartment, as Faris in the foreground washes his face in the kitchen and slowly turns to watch it. The adult Faris's kinky hair is shaved in the shape of a short lion's mane. Faris owns a lion cub he loves that is largely restricted to a cage. The one scene of Faris alone with the cub is shown in a beautiful upward architectural pan shot as Faris enters a sunny courtyard. Faris and his friend Masala employ the cub as a prop in a scene at the pyramids in Giza that is difficult to watch given abuse of the animal. They charge tourists ten US dollars to use their cameras to take exotic photographs with the natives and their cub.

In light of scholarship on Egyptian cinema and television, it is important to establish from the outset that, although these two films resonate with Egyptian audiences on a range of affective, social, and political registers, al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad are neither what Suzanne Gauche calls “national” films nor what Robert Lang terms “cinemas of resistance.”Footnote 15 They do not stage, as Joel Gordon argues for earlier Egyptian films, nostalgia for the revolutionary Nasserist period or “an imagined community … characterized by civic responsibility.”Footnote 16 They do not serve what Teshome Gabriel refers to as a Fanonian liberation project or fit within the genre Viola Shafik calls “committed films of the New Realism” produced in the 1980s and 1990s.Footnote 17 They do not assert Egyptian cultural inferiority, the value of indigenous traditions, or the superiority of the middle class.Footnote 18 Nor are the films pedagogical in the “developmental realism” paternalistic sense discussed by Lila Abu-Lughod in her ethnographic analysis of 1990s Egyptian serial dramas.Footnote 19 The films do not stage Ramadan's protagonists Shahin and Faris as humiliated “common men” betrayed by the modern state.Footnote 20 Nor do they directly or indirectly grapple with larger matters of imperialism, colonialism, or Zionism.Footnote 21

Made for Egyptian and Arab audiences, al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad privilege entertainment. Similar to the bulk of Egyptian cinema, the un-subtitled films were destined for popular consumption rather than festivals.Footnote 22 Like other scholars, I take these films seriously irrespective of intellectual criticisms of their “triviality,” “vulgarity,” excessive melodrama, and inauthenticity.Footnote 23 Although viewed by tens of millions of Arabs, al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad have yet to draw scholarly attention as far as I can determine, with the exception of a short essay in Arabic published online in 2014 by Muhammad Sayyid `Abd al-Rahim.Footnote 24

Muhammad Ramadan's characters in the two films, Shahin Almani and Faris al-Ginn, are skilled fighters and dancers who express sadness and poignant emotions at various points. Overall, however, Shahin in al-Almani is stoic and violent, whereas Faris in Qalb al-Asad is funny, sarcastic, and clever. Ramadan's sinewy brown physique is central to each story and an object of erotic desire. The protagonists he plays enact their masculine physicality in alleys, streets, and bedrooms, moving with ease through wealthy and poor neighborhoods in greater Cairo. The films invite the audience to identify with masculine figures who rely on a combination of wiry physicality, intelligence, violence, and duplicity to survive.

Ramadan has avoided being typecast, playing with some panache protagonists in comedic, dramatic, historical/political, and action films, as well as men of urban, rural, poor, middle-class, and bourgeois backgrounds. He has performed in films aimed at popular and elite audiences. A talented multidimensional entertainer, the prolific Ramadan epitomizes the impulses of entrepreneurial Egyptian millennials. Born in May 1988 in the village of Munib south of Giza to a family of reportedly modest means, Ramadan is the youngest of three children. He played football, training with the Zamalek Club, until he turned to theater in high school. He continued acting while a student at `Ayn Shams University, performing in independent theater productions and later in television serials and films. He worked as an extra in a few comedy films targeted at young audiences in his early to mid-teen years and moved to playing a confused and sympathetic young police officer in the 2008 comedy film Rami al-`Itisami. His first significant role was in Yousry Nasrallah's 2009 fantasy drama Ihki ya Shahrazad (Scheherazade, Tell Me a Story), in which he plays a proletarian employee in a home repair shop in a popular quarter who manipulates the three sister co-owners against each other. In 2010 he starred in the subtitled artsy drama al-Khurug min al-Qahira (Cairo Exit), playing a working-class Muslim man who falls in love with a Coptic woman. In a short 2011 film, Bard Yanayir (Cold January), which won many national and international awards in 2012, Ramadan plays a patriotic young man who while walking across a bridge over the Nile speaks to and purchases a flag from the young daughter of an impoverished woman before attending the January 2011 demonstrations. In the 2011 film al-Shawq (Lust), a subtitled high art production set in Alexandria, Ramadan plays a lower-middle-class young man who wants to escape his poor neighborhood by migrating across the Mediterranean, leaving everything and everyone behind, including his girlfriend.

Ramadan's acting credits include other projects produced, coproduced, directed, or codirected by Ahmad al-Subki and Karim al-Subki, such as the 2012 comedy Hasal Khayr (Good News). Although his protagonists in non-Subki productions remain varied—including historical and comedic characters—Ramadan has recently played salutary protagonists who become violent in a fight for a good cause in three Subki productions. Shadd Ajza’ (Tightening Parts) is a 2015 drama in which Ramadan plays an upper-middle-class police officer who breaks the rules to get vengeance for the murder of his young wife, a new mother. The 2017 drama Gawab I`tiqal (Detention letter) is a thriller in which Ramadan joins an Islamic terrorist group first to release his brother from the group and later to avenge his death, becoming a wanted man himself. In the 2018 action film al-Dizil (Diesel) Ramadan's proletarian character seeks to find and kill whoever murdered his fiancée. Ramadan has won Egypt's Best Actor Award for three years in a row, an unprecedented achievement.Footnote 25 Many of his films include scenes that foreground his immense talent as a dancer, including al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad. More recently, Ramadan performs his music in concert halls and produces viral music rap videos that are posted on a dedicated YouTube channel.Footnote 26

The late dark-skinned actor Ahmad Zaki is popularly considered to be Ramadan's closest predecessor in Egyptian film and television because of his brownness, kinky hair, and the characters he played, especially earlier in his career. Indeed, Ramadan was dubbed “the new Ahmad Zaki” after his acclaimed performance in Ihki ya Shahrazad.Footnote 27 Zaki, who was called “the Black Tiger” after starring in a 1984 film by the same title (al-Nimr al-Aswad), rose to stardom in the mid-1980s (when he was in his mid-thirties) in film and television and worked until he died of lung cancer in 2005 at the age of fifty-five.Footnote 28 It is worth noting that neither Zaki nor Ramadan are phenotypically black-skinned Egyptian actors. In Egyptian films dark-skinned characters still most often are unnamed, underdeveloped roles, as in the two Ramadan films al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad.

Ramadan also is compared to Zaki because of the protagonist Zaki played in his breakout 1988 film Ahlam Hind wa Kamilya (Dreams of Hind and Camilia). In the film, `Id is a womanizing proletarian working in the illegal economy who ultimately makes good by marrying the domestic worker (Hind) he had impregnated, played by a young `Aida Riyadh.Footnote 29 Zaki's role in Ahlam Hind wa Kamilya differs from Ramadan's roles in al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad in at least two ways relevant to my argument: `Id and his male and female acquaintances in late 1980s Cairo work, live, and circulate in the same spaces as the middle classes rather than being drastically segregated from them. Ahlam Hind wa Kamilya juxtaposes unequal class relations in the intimate spatialities of homes, on front door staircases, on sidewalks, and in cafés. Second, Zaki's character, `Id, is rehabilitated, achieving what we might call respectable working-class heteronormativity when Kamilya convinces him to marry the noticeably pregnant Hind. He does his best by Hind and loves their daughter Ahlam (trans. “dreams”) despite ultimately serving prison time because of his criminal efforts to build a better future for himself and his nuclear family. The film portrays `Id's inability to fulfill the role of the respectable breadwinning father as understandable given the contradictions of a deeply unequal society, making him similar to most proletarian men. By comparison, the two Ramadan films I examine assume from the onset that abiding by sexual respectability norms or turning to married life for economic and social stability are failed strategies for the popular classes, an argument developed in the next section.

Subverting Respectability Tropes

A number of scholars have addressed the politics of respectability in Egypt.Footnote 30Al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad offer familiar morality and respectability tropes in relation to work, crime, sex, and family life even as they undermine their validity and challenge their fairness. Beyond Shahin Almani's repeated statements that he wants to live a clean rather than illicit life, moralizing regarding sexual behavior, gender codes, and drug and alcohol use is limited in these two films. The poor understand they must skirt or violate the boundaries of legality and social acceptability to survive. During a depressed moment after sex, Shahin tells Sabah that he feels disgusting (arfan min nafsi). He wants to find work that allows him to become “clean” (`ayyiz anzaf) but instead finds confirmation that life itself is pathological.Footnote 31

Shafik argues that Egyptian films of the 1950s and 1960s often used the “seduction/rape motif” to express class and colonial subordination, as did the committed new realism cinema of the 1980s and 1990s, in the process continuing to associate “women with morality.”Footnote 32 This pattern continued in committed cinema produced in the 21st century, such as the highly acclaimed 2007 film Hiyya Fawda (This is Chaos), codirected by Youssef Chahine and Khaled Youssef.Footnote 33 Rape is central to the plot but serves as an allegory for political critique. In the film, the obsessed stalker, police sergeant Hatim `Abd al-Basit, the corrupt “Pasha” in charge of control and extraction in the Shubra neighborhood, rapes the middle-class, educated Nur and incites a popular rebellion. In comparison, there are no rape scenes in al-Almani, although Shahin has sex with a brothel worker to punish his lover, her coworker Sabah. In the same film, a wealthy john, unaware he is being snared in a collaborative theft operation involving sex worker Hanan and two men from the neighborhood, invites them to rape Hanan in front of him instead of robbing him and stealing his wife's Mercedes. They decline. In the one scene of sexual assault in Qalb al-Asad, Salim Bey's bodyguards hold good girl Ruqayya hostage in the living room of his luxurious mansion as the others beat Faris. If Faris does not promise to double-cross his biological cousin (policeman `Issam), bad girl Nana says they will kill his fiancé but first make her a “madam,” that is, rape her. Nana rips Ruqayya's blouse and invites the men to attack her, with the darkest-skinned bodyguard putting his face to her neck while she struggles and screams on the ground until Faris promises to do what Salim wants. In an evening scene set outside the gates of the posh Al Wadi October Hospital in Giza, where Faris has ventured to light a cigarette after visiting his neighbor Safiyya, he half-jokingly asks if Salim's bodyguards are going to rape him when they kidnap him. These motifs associate sexual assault and rape with having class and political power, arguably articulating another symbolic system that avoids addressing and challenging quotidian sexual harassment and assault in interpersonal, work, and public spaces.

The morality motif comes up in other ways. In Qalb al-Asad, which was released a week before government forces massacred Mohamed Morsi supporters at a sit-in outside the Rab`iyya al-`Adawiyya Mosque, a number of short scenes center on conflict over a small mushaf, a pocket copy of the Qur'an. Safiyya, love interest Ruqayya's mother, has given the text to Faris al-Ginn for protection. In the initial scene, he kisses its cover and stows it in a pocket. In a later scene in Safiyya's private room in a posh hospital, Ruqayya tells Faris “you forgot the mushaf” and holds it out to him. The upper body shot shows his deep hesitation before he reaches to accept it. During an argument in the cramped hallway of the modest home she shares with her mother, Ruqayya asks Faris to take out the Qur'an and swear on it that his new money is from a legitimate source. When he cannot find the small book, she asks him sarcastically if he forgot it. I read the tension over the pocket-size Qur'an as symptomatic of the society-wide reckoning of Egypt's post–January 25 Revolution political identity. This upheaval intensified during the year Morsi was president, from 30 June 2012 until the military coup of 3 July 2013, because the choices offered in hegemonic discourse in postrevolutionary Egypt continued to be dichotomous: a militarily-ruled or chaotic society, civil or Islamist rule.Footnote 34

The argument between Ruqayya and Faris ends as he walks down a set of stairs that increasingly separates him from her as she faces his back, visually expressing the widening high-low ethical gap between them (Fig. 3). The scene also evokes the childhood meeting moment when he looks up from the bottom of the same stairs at her and her mother having a meal. Ruqayya threatens to break her engagement with Faris instead of reciprocating his declaration of love because she is suspicious of his newfound wealth and behavioral changes, which suggest he is taking the wrong path. Faris angrily points out the deep class barriers for most Egyptians, as well as his persistent efforts to overcome them. By the end of the scene he metaphorically accuses Ruqayya, and by extension all poor Egyptians who buy into middle-class respectability tropes, of having internalized poverty: “Your road is full of takatik [three-wheel unregulated rickshaws] and microbuses, but my road is paved and has no bumps. Do you know the difference between you and me, Ruqayya? Poverty runs in your blood, but I have ambition.”

Figure 3. Qalb al-Asad. Author screenshot of Faris walking down the stairs with his back to Ruqayya during an argument.

Acquiring respectability, as outlined in Farha Ghannam's ethnographic sketch of the life trajectories of a brother and sister in urban Cairo, is difficult in these films.Footnote 35 Shadya's life story in al-Almani challenges the trope of heteronormative marriage as a source of stability for the lower classes. Her disreputable work with pregnant single women seeking a safe place to give birth illustrates the degree to which sexual respectability relies on dissimulation and social fiction. A nightclub incident in which a wealthy young woman refuses to recognize him emphasizes that Shahin will never be able to meet classed expectations for masculine behavior while retaining his dignity. This failure is emphasized when Habiba decisively rejects him as a marriage prospect because his criminal behavior and sexual laxity violate her moral values. More importantly, her petit bourgeois widowed father Salih absolutely refuses the possibility of such a union.

Living respectably offers little protection even to this father. In an evening scene, Habiba joins the pensive Salih at their modest dining table. Foreshadowing her murder, the excessively protective father, deathly afraid throughout the film that harm will come to his daughter and himself, cries and asks her to forgive him for not being able to protect her. Salih represents one form of failed fatherhood in these films: a rule-following conventional man who tries to do right by his family but is defeated at every turn. The film makes explicit the contrast between the masculine subjectivities represented by Shahin and Salih in an early scene. After Shahin commits the televised murder, his mother Shadya runs to Salih's apartment to ask for help. Salih is dismissive, “I told Shahin to keep to himself.” Shadya insultingly responds that Shahin cannot stay out of things because he would turn out like Salih, a weak and terrified man. The respectable family similarly offers little protection or value in Qalb al-Asad: Faris `Abd Allah al-Sawwaf was abducted by the drug-addicted Zinham while he was with his blind middle-class father, indicating the stark realities such parents do not see and from which they can offer little protection to their children.

The relationship between Shahin and his girlfriend, sex worker Sabah, in al-Almani is domestic and intimate in ways that do not distinguish between a paid and an unpaid sexual partner. In a postcoital scene between Sabah and Shahin, Sabah easily suggests that one of her johns working in the tourism industry had helped someone else escape the law for about 20,000 Egyptian Pounds and could assist Shahin. Sabah directly challenges the economic worth of sustaining a division between respectable and illicit work. In an earlier scene in the gift shop, she mocks good girl Habiba, who was working behind the counter, for passing on lucrative sex work opportunities to retain her respectability. She challenges her with some quick math, “I am advocating for your interests. You probably make 150 ginay a month, right? That is about five ginay a day. Work with me and I'll give you five ginay a minute.” The brothel owner Umm Gamal calls at that moment to assign Sabah a job in upper crust Màadi making 200 LE an hour. Sabah turns to Habiba to emphasize, “See, 200 ginay in an hour!”

Habiba in al-Almani is killed and good girl Ruqayya in Qalb al-Asad is ultimately irrelevant. She (like Faris's biological father) is absent in the final getaway scene in which a shiny new convertible is driven by her fiancé Faris on a sunny day in Cairo, his best friend Masala in the passenger seat and his symbolic father, the drug addict who abducted and raised him, in the back (Fig. 4). Although al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad are similar to films produced before the 2011 revolution in expressing classed frustrations around “blocked futures,” they are different, I contend, in that “deadly forms of violence” are not ultimately “contained by the family.”Footnote 36 They are unsentimental in staging normative family life and sexual respectability as difficult to sustain and offering little of value to the poor.

Figure 4. Qalb al-Asad. Author screenshot of Masala, Zinham, and Shahin in their new convertible.

“Thugs” and Police in Postrevolutionary Egypt

In her 2006 ethnography of Bulaq ad-Dakrur in Cairo, Salwa Ismail shows how police as agents of the “everyday state” abuse, monitor, humiliate, and limit the mobility of young men from the popular quarters even as they facilitate and profit from illegal activities.Footnote 37 In contrast, police and intelligence officers are largely absent in al-Almani and staged as harmless interlocutors and protectors when they do appear. Characters in the film refer to “the government” (al-hukuma) at crisis points, noting that it targets them first irrespective of evidence, cannot be relied on even when they need help, and is a failure that literally makes people ill. Qalb al-Asad personifies the antagonists as corrupt unaccountable government officials—not police officers—despite the backdrop of massive malfeasance by the government's central security services. Such sleights of hand may be attributable to censorship rules and fortification of the authoritarian state.

The antithesis of the state and its representatives of law and order are futuwwa and baltagiyya—tough guys or thugs—who have long histories as masculine subject positions, targets of governmental discipline, and discursive figures in Egyptian cinema and literature. Between the 1950s and 1980s, a number of Egyptian films featured thug and tough guy figures in which “an urban lower class character” with “physical capabilities—including traditional stick fighting—is able to positively or negatively monopolize power in a traditional alley.”Footnote 38 Wilson Jacob argues that futuwwa was a capacious term for a broad range of historically shifting Egyptian male socialities and embodied sovereignties not invested in the state, traditional family life, or modernity per se.Footnote 39 As evocative and polysemic signs, futuwwa and baltagi have been symbols of a variety of anxieties and conflicts. Real and symbolic thugs may be protectors, bullies, or both.Footnote 40 As Parama Roy argues for colonial imaginaries of 19th-century India, “the thug as a discursive object … is all things to all people.”Footnote 41 The government of former president Hosni Mubarak frequently deployed the term baltagi for resistant boys and men, even as it obfuscated the distinction by hiring boys and men off the street to attack politically resistant women and men. The word baltagi is used frequently in al-Almani, whereas Qalb al-Asad, released a year later, avoids using it and offers a more sympathetic and less violent protagonist who is a tough guy nevertheless.

Egyptian films produced in the 1950s typically staged police officers as salutary representatives of order, as illustrated by the 1954 film Futuwwat al-Husayniyya (Thugs of al-Husayniyya), written by Naguib Mahfouz and Niyazi Mustafa, directed by Mustafa, and produced by Muhammad Fawzi. Set in Cairo in the early 20th century under Ottoman and British rule, the drama stars an early “tough guy”, Farid Shawqi, who plays villager Mahsum al-Fayyumi, and Huda Sultan (Shawqi's wife in real life at the time) as his love interest.Footnote 42 The “social life and death of al-futuwwa preoccupied” the realist writings of Mahfouz from the late 1930s, with representations shifting to reflect “the difference between the hopefulness accompanying Egypt's anticolonial struggle and the disillusionment following its postcolonial failures.”Footnote 43 In Mahfouz's dozens of screenplays, “Justice is revolutionary … and appears overwhelmingly in the form of the police. In contrast to the cruelty and decadence of the alley and its masters, officers of the law are embodiments of order and modernity.”Footnote 44 The 1954 film classic Hayat aw Mawt (Life or death) also stages the police as salutary selfless actors who mobilize with large numbers of Cairenes across a massive metropolitan area to save Ahmad, an unemployed and ill middle-class professional striver, from being inadvertently poisoned by a prescription medication.Footnote 45

In contrast, despite the corruption of the Egyptian central security services and the violence and repression its police forces visit on poor people and political activists, al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad stage policemen as neutral foils, reasonable men overwhelmed by upheaval. For example, after a stylized street fight between neighborhood men and bodyguards looking for Shahin in al-Almani, a plainclothes officer soliloquizes: “These days we don't know who is who or what to do, between the misfortunes of the children of the wealthy, who will make 100 problems if we apprehend them, and the misfortunes of the lost and scattered, whose story also will never end if we catch them.” Deploying a motif of humanity and the human (bani adam) expressed in both films, a young man asks him, “You hit us in the daytime, though, why? Aren't we human?” The officer ignores the interior ministry's violence and its investment in paid street thugs in his response: “Everyday you've overturned the world on us, with the satellites [fathaiyyat], and saying thugs [al-baltagiyya], thugs [al-baltagiyya], catch the thugs [imsiku al-baltagiyya]. We do not know what to do. Every area has six, seven thousand thugs, and each of them feeds a whole group its daily bread.” The officer renders police and military officers as sympathetic, above the fray, and not responsible for any misfortune and suffering.

Qalb al-Asad explicitly invites viewers to identify with ethical police officer `Issam, Faris's biological cousin, and by extension the security services. `Issam leads a sting operation against Salim Bey that presents central security service officers as savvy crime fighters who rely on sophisticated planning and the latest surveillance equipment, including a GPS-enabled lighter that Faris slips into Salim's pocket while being beaten by him, a technology that ultimately allows for Salim's apprehension. The producer Karim al-Subki worked with the ministry of interior to acquire the multiple police vehicles used in Qalb al-Asad.Footnote 46 Muhammad Ramadan has expressed support for the security services, although given the repressive Egyptian context it is difficult to separate his ideological commitments from his protective self-positioning.Footnote 47

I offer an alternative reading of proletarian approaches to Egyptian state violence drawn from the words of Faris al-Ginn in Qalb al-Asad as he convinces his hesitant best friend Masala to collaborate in a sting organized by his long-lost cousin `Issam against the corrupt Salim Bey. “The police,” Faris explains to Masala, “are the [female] cousins of the people [al-shurta bint `am al-sha`b].” That is, the poor are conjoined to the police just as young men are culturally expected to marry a female paternal cousin. Masala jokingly replies, “You mean the police is your cousin.” Even if Faris and Masala refused to work with Officer `Issam, Faris reminds Masala, “there would be ten others” to take his place, both evoking and unsettling dialogue from the final scene of the classic treatment of the neighborhood thug figure, the 1957 film al-Futuwwa (The Thug) starring Farid Shawqi.Footnote 48 Set in colonial Egypt but produced four years into Gamal Abdel Nasser's presidency, state agents are largely absent in the film as criminal elements target small merchants in an urban fruit and vegetable marketplace. The violent venal boss Abu Zayd controls prices, products, and merchants, paying off representatives of a colonial state. Haridi (Shawqi), the righteous and tough village merchant, becomes equally evil in this timeless morality tale. After Abu Zayd and Haridi are killed, a police officer sporting a white uniform says to relieved vendors in the street market: “The question isn't one of individuals. Abu Zayd and Haridi are gone, but a thousand like them will come to take their place, with their greed and avarice.” Although the officer in al-Futuwwa presents state institutions during the earlier postrevolutionary moment as protecting the working classes from a proliferation of greedy actors, in a postrevolutionary cinematic moment about fifty-five years later, Faris and Masala in Qalb al-Asad express little faith in the state. Instead, they delicately point to the difficulty of avoiding its numerous agents, who penetrate the lives and spaces of the popular classes.

Revolutionary Resistance, Defeat, or a “Third Option”

In keeping with the era's contentious spirit, many Egyptian films from the first decade of the 21st century challenged political repression and economic inequality, condemning “the ruling classes,” especially “businessmen and the security services.”Footnote 49Al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad, released a year and a half and two-and-a-half years after the January 25 Revolution, are haunted by a fortified repressive state that never comes into focus despite occasionally wistful references to revolutionary ideals, although the theme of the injuries of class inequality is persistent. Whereas al-Almani concludes with a cycle of violence and little hope, Qalb al-Asad's story line and cinematic form differ by suggesting the possibility of ideological reconciliation and an ending that is neither revolutionary resistance nor complete defeat.

Both films alternately represent the 2011 revolution as an interruption of business as usual, a source of chaos, and a question mark. Characters in al-Almani repeatedly use the phrases “the world is a mess” (al-dunya kharbana) or “the world is upside down” (al-dunya maqluba). Corrupt officials in Qalb al-Asad mention expensive slowdowns and new barriers implicitly related to the revolution. When the prosecutor tells the parliamentarian Salim Bey over lunch that an illegal weapons sale must wait “in this period,” Salim responds, “no way, no way, the product must be delivered. … My brother, what are we waiting for? We have been sleeping for a period.” The prosecutor remains anxious and pushes his food away. In contrast, the portly Salim continues to eat, as in multiple scenes in which he never seems satiated.

Al-Almani was produced and released in 2012 and Qalb al-Asad in 2013, years when downtown Cairo witnessed many moments of tumultuous protest and revolutionary and counterrevolutionary violence. Al-Almani was staged (sometimes conspicuously) in studio and on location in Hataba (near the Salah al-Din al-`Ayyubi Citadel), Bulaq, Manyal, and Dokki, distant from places that evoke memories of revolutionary encampment and violence and show the military partitions, concrete walls, graffiti, and government propaganda that transformed those spaces.Footnote 50Qalb al-Asad, working with the much larger budget of a Subki production, includes car chases, uses innovative cinematic techniques, and is strikingly edited, with lighting and sound quality that give it a more polished look.Footnote 51 Like al-Almani, however, Qalb al-Asad avoids downtown Cairo. It would not be surprising if ideological and practical concerns affected staging location decisions. Nevertheless, references to revolutionary resistance and counterrevolution occur in both films in motifs, persistent questions, and occasional images.

About thirty minutes in, al-Almani stages a rare scene of political analysis produced under the influence of drugs that cloaks revolutionary sensibilities in Egyptian humor and criticizes the inequality deeply imprinted on the geography of Cairo. Shahin, Asli, and Faris are relaxing in Asli's darkened bedroom, smoking hashish and becoming increasingly stoned. Shahin is somber because he is in love with Habiba but she is unlikely to accept him. When Asli suggests that Shahin express his love to Habiba, he responds he is not good enough for her. Becoming silly, Faris exclaims, “You are the German … all the countries know you!” Joining in the fun, Asli suggests an absurd possibility to Shahin: “You should be president of the republic. Why are you laughing? All you need is to prepare photographs and register. … We used to participate in elections that did not concern us. The coming elections affect us and we have an impact on them!” Asli and Faris laugh when Shahin takes up the idea, “You know, the girls used to call me ‘Obama,’” referencing his brownness, which contrasts with the lighter countenances of his friends. As they continue ribbing each other, Shahin asserts with seriousness: “If I am elected president, I would require a social exchange, my first decision would be to bring residents of [upper-class] Zamalek to [lower-class] Kitkat [in Giza near Agouza] and residents of Agouza to Zamalek!”

Different characters use the term “nightmare” (kabus) a number of times early in Qalb al-Asad, alluding to the social and political situation in 2013 and gesturing to a larger nightmare in which Egyptians are trapped. The film occasionally visually signifies the social and political upheaval that marks the geography of Cairo. For example, Faris wears a tight short-sleeved red t-shirt in multiple evening scenes that unfold, beginning with his kidnapping by Salim Bey's bodyguards. The shirt's overlapping architectural images in black and white evoke shadows, columns, and even hieroglyphs around which a logo in black and white English lettering reads “The City is Undergoing Construction,” implying that work is in progress on multiple scales in Cairo. Location shooting occurs in cinematic spaces that show revolutionary graffiti at various points during car and foot chases, most startlingly for a mere two seconds during a wide angle shot of Faris sprinting away from bodyguards up the stairs of a pedestrian bridge. A movable concrete barrier shown behind him at the bottom of the stairs is spray-painted in light black “Yasqut al-Mushir” (Down with the Field Marshal), referring to Muhammad al-Tantawi of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), who was installed as head of state when Hosni Mubarak stepped down as president in February 2011. Below this slogan in brighter red is spray-painted the widely used revolutionary slogan, “al-dakhiliyya baltagiyya” (The Interior Ministry [are] thugs), reminding alert viewers that the primary source of thuggish violence in Egypt is the ministry that oversees the central security services and its uniformed police officers.

For those without class privilege, access to political levers, or investment in collective political struggle, resistance is usually indirect, impure, and informal, operating at infra-scales and in quotidian realms. It is about materially surviving within the given conditions. Al-Almani includes multiple scenes of transactions involving money set around propane tanks, stolen appliances, sex, motorbikes, and drugs. These transactions are often referred to as maslaha (interest or opportunity), playing on use of the term by elites who strategically maneuver to improve their personal situations by extracting resources from those with less influence and money. In a humorous brothel scene in which the Madam Umm Gamal and her husband complain about a month with no clients, a sex worker says it's not her fault since “half the men are afraid and without desire,” and a second finishes the sentence, “and the other half don't have 20 ginay in their pockets!”

Qalb al-Asad expresses the theme of racialized economic struggle intertextually. In a quiet scene of Faris alone in his bedroom changing his shirt and shoes, rap and hip-hop posters decorate his walls, drawing on a global genre of resistant unauthorized masculinities (Fig. 5). One of the posters is for the song “Hold Me Back,” released in July 2012 by the Florida rapper Rick Ross, with a refrain that laments barriers, scarcity, trying to keep on the lights, and the necessity to “hustle.” Another advertises the album P.O.M.E. (Product of My Environment) by New York City artist Jim Jones (released in November 2006) in which he sings of “chasing death” and thirsty vultures.Footnote 52 The hip-hop performers make their mark and money in the cultural marketplaces of racial capitalism rather than by demanding rights as radical activists. Mark Anthony Neal terms this “hip-hop cosmopolitanism” in his analysis of the work of African-American artist and entrepreneur Jay-Z (Shawn Carter). Jay-Z's career, Neal argues, reflects contemporary “hip-hop's unfettered pursuit of leisure, wealth, capital, and movement,” in the process challenging a hip-hop binary of authentic localism (attachment and belonging to the hood) and global cosmopolitanism, even when individuals do not have the resources to actually leave a neighborhood, or Cairo in Faris's case.Footnote 53

Figure 5. Qalb al-Asad. Author screenshot of Faris's bedroom with hip-hop posters.

In the only scene of collective struggle in either film, boys and men from Nazlat al-Simman near the Giza pyramids in al-Almani emerge to participate in a dramatic stick fight in defense of Shahin against security guards from an elite nightclub. The previous night Shahin had used a bat to destroy the car of a wealthy young woman who insulted him as he prepared to valet park it outside an expensive nightclub. Sabah the sex worker had found him this short-lived employment after he told her he was disgusted with himself, was in love with Habiba, and wanted to work in a respectable job despite limited pay. Shahin is shattered the first night on the job not as a result of the work's meager pay or low status, but because this woman refused to consider him worthy of her recognition. Wearing a short red dress, high heels, and manicured long black hair, she insultingly gestures to him with her car key to, “take it, you… [ya].” Shahin responds, “My name is Almani” (ismi Almani). Her hyperbolic retort condenses class-based indignities: “Did I ask your name? Your job is to take this car, park it and shut up!” Shahin's goal to get good girl Habiba through a licit low-paying job is defeated by the personal failings of arrogant elites, not incidentally personified by a beautiful wealthy young woman who parties at nightclubs. In the process, the film mystifies and validates the class structure that benefits elites, since it implies that Shahin would have remained in the job if he had not been so deeply insulted. This humiliating interaction triggers a downward spiral that culminates with Shahin stealing Ahmad's mobile phone and black leather jacket and murdering him in the film's opening scene.

In a rendering of the 2011 Arabic revolutionary chant, “al-sha`b yurid isqat al-nizam” (the people want the fall of the regime) that reverberated in physical and digital spaces when tens of thousands of voices chanted it, the opening music of Qalb al-Asad repeatedly demands, “The people want [the film] Qalb al-Asad for `Id!” (al-shàb yurid Qalb al-Asad lil-`Id). This trivializing of the main slogan of the massive uprisings and revolutions that occurred in multiple Arab countries nevertheless evokes their energy and may even express masked disappointment in their outcomes. In an evening scene on a rooftop near the end of the film, we learn that Faris and Masala had coordinated with Faris's criminal father to steal from Salim's weapons sale proceeds even as they collaborated with the police in a sting operation against him. Faris jokes with his friend Masala as they stand over two black cases full of US one-hundred-dollar bills that it would be wrong to return to civilized society without the money to pay for hummus. In a bird's-eye camera shot of them standing over the cases, they sequentially look at the money and each other and chant in unison, “Long live Egypt!,” a perhaps gratuitous gesture to film fans or government censors. Signaling more than that, in the final car scene the pair talk of investing some of their stolen riches in a “national project” such as a Molotov cocktail factory, reminding viewers of revolutionary struggle and spoofing the socialism of the Nasserist period, another disappointing yet ultimately beloved project. I read these statements as tying together the popular hopes invested in Egypt's two revolutions.

The sikka (path) motif, the idea that Egyptians are at an ideological and practical crossroads that requires a choice between one of two directions, threads through both films. In al-Almani, the path most available to Shahin and his male friends is informal violence, what he calls sikkat al-`afiyya (the path of force), their sole source of leverage against elites. Shahin recognizes that love is one area where violence will not do, which is why he briefly works in a legitimate job in a failed attempt to be accepted by Habiba and her father. When the television host condemns Shahin for killing a man for his mobile phone in a backstage scene, Shadya responds, “How should he eat?” Ranya suggests that he work. Shadya retorts, “He should serve you, right? You would ride in cars and live and he would serve you?” During the live studio interview with Shadya, Ranya expresses her sympathy for the righteous Salih and Habiba and “all the people who want to live right but cannot and are forced to live among you.” Shadya responds with measured outrage, “Among us? We are correct and we scare you. You know we can force you to hide in your homes. Almani will escape. He will disappear for a while and then he will return to you in your homes!”

In Qalb al-Asad, when Faris explains to Salim that he does not want to transfer “arms that will kill people,” the politician replies, “You need to make a choice about which side you are on.” Faris's fiancé, Ruqayya, caustically accuses him of being on one path while she is on another, although she notably remains engaged to him at the end of the movie. The film includes an intense and beautiful outside evening scene between Faris and his best friend Masala, with the sounds of wildlife, Umm Kulthum music playing in the background, and a calm brown horse hitched to a nearby post, presumably employed to give tourists rides at the Pyramids during the daytime. The magical effect is amplified when the horse directly returns the gaze of the camera. Masala, who is more willing than Faris to cross the boundary between licit and illicit behavior to take advantage of opportunities to make money, tries to convince his hesitant friend to participate in the dangerous criminal enterprise offered by Salim. Faris tamps down Masalla's excitement: “We are entering a path [sikka] whose end we have no idea of.” In a close headshot, his profile and hair framed by warm light, Masala passionately makes his case to Faris: “We want to live like other people are living. We want to eat the best food, to sleep in the best beds, to befriend the most beautiful women in the world. Or do we want to remain buried here in this dirt?” Faris resists his friend's entreaties, although he acknowledges, “This is an age that legally encourages wrong.” Masala gives Faris a drag from his cigarette and responds, “This is the point the world has reached—either we are with them and like them or it is the end of you and me.”

At the end of this scene, in a rare explicit reference to the revolution, Faris quietly asks Masala whether life will be “more of the same” (ziyadat al-zahira) or “the revolution will continue” (al-thawra mustamirra). Masala replies, “No, we're taking the third option.” Qalb al-Asad indeed invites viewers to consider options that are neither frontal collective revolutionary resistance nor acceptance of more of the same situation. For example, even as Faris and police officer `Issam, his biological cousin, reconcile and ultimately collaborate so that the corrupt Salim is arrested, Faris steals some of the captured gun-running proceeds and shares them with Masala and his abductor-father. Faris maintains his relationships with his newfound blind biological father and his petty criminal father, his friend Masala and his cousin `Issam, instead of choosing between them.

Related to this third path is the possibility of radical contingency opened up by the form and editing of Qalb al-Asad. The film begins with a slow-motion outside evening scene in which a bloodied Faris and the corrupt prosecutor point guns at each other. We hear Faris breathing loudly and heavily before he comes into focus. He drops his gun under threat from the prosecutor, who nevertheless shoots him. Faris falls in slow motion onto the designer concrete tiles. The scene is then reversed in slow motion, undoing the fall and the shot, except Faris turns from a profile shot to stare intensely at the audience (Fig. 6), and this opens a lengthy flashback. The slowed and reverse motions point to the potential for do-overs in Egypt, for rewinding and reversing the causes of action and opening the possibility of alternative outcomes. Similarly, the film is edited in the last few minutes to dramatically reverse events in the recent scenes, using fast cuts between past and present and double flashbacks to fill out details and show the “real” story trajectory, the events that occurred behind the scenes. Masala had not betrayed his best friend Faris to the corrupt Salim for money despite outward appearances. Instead, Masala and Faris had coordinated a successful double-cross operation. We prematurely assume the ending, as is likely the case for Egypt, where ideological, material, and cultural battles and transformations continue on multiple scales, many of them not easily seen or measurable.

Figure 6. Qalb al-Asad. Author screenshot of Faris al-Ginn in opening shootout scene as he faces the camera.

Conclusion

Some have criticized al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad in moralistic terms, as did the chauffeur I mentioned at the beginning of this article. Bourgeois and establishment condemnation of the vulgarity and corrupting influence of mass culture and its artists and entrepreneurs is part of a long tradition in Egypt.Footnote 54 High-culture producers in Egypt often reproduce Arab enlightenment discourse even when they criticize the state.Footnote 55 In an online essay published in 2014 titled “Liman Yusna` al-Aflam?” (Who are Films Produced For?), Muhammad Sayyid `Abd al-Rahim analyzes al-Almani, Qalb al-Asad, and a third film starring Ramadan, `Abduh Mawta, arguing that all three antiheroes challenge prerevolutionary cinema's foregrounding of the virtues of Egyptian middle-class values. Although the essay at times deploys a distancing elitist lens when it refers to a collective “popular” mind, `Abd al-Rahim challenges those who dismiss these as merely “thug” films. The protagonists, he argues, are manifestly responding to their social conditions, and both protagonists and antagonists are “drowning in trouble.”Footnote 56

Al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad were a safe way for me to examine masculinities at a time (January and February 2014) when Cairo was unstable and dangerous for fieldwork. State-sponsored violence, imprisonment, economic precariousness, and sexual assault threatened everyday Egyptians as well as researchers and activists. Activists in organizations I studied were subdued, depressed, underground, or shut down. As an Arab-American woman researcher, I received accusations of US support for the Muslim Brotherhood and foreign schemes to destroy Egypt. In contrast to the situation during a research visit in the summer of 2011, in 2014 I was stunned by ubiquitous public support for the military government. Three years after the start of the January 25 Revolution as a protest against National Police Day, the counterrevolution seemed to have settled into itself. A week after my arrival, I realized that security forces were monitoring my movements while I stayed in a downtown hostel. At around 11 p.m. in mid-February, leaving a dinner meeting at a restaurant a few blocks from Tahrir Square, the Egyptian doctoral researcher I was with refused to walk out until her husband texted that he was outside to pick her up in their car, and she discouraged me from taking a taxi or walking. I declined their offer of a ride and walked the six blocks to my hostel, increasing my brisk pace as I saw no girl or woman on the relatively lively sidewalks. It felt decidedly less safe for girls and women in greater Cairo than on trips over the previous twenty-five years, although, as a woman who usually moves alone through the city and walks a lot, I experienced and observed many incidents of verbal sexual harassment, bold staring in restricted spaces, and unwanted touching before and after the revolution. The films I examine in this article forced themselves into my field of attention during a confusing and anxious time in Egypt. The militarist masculinities sponsored by the state and United States imperialism permeated the Egyptian scene, mixed with the quotidian grinding violence of poverty and sexism.

Given this context, it is notable that most battles in al-Almani and Qalb al-Asad are personal rather than confrontations with the world or the system. Although the thug is depicted more as a victim of class injuries than a victimizer, the films personalize subordination and injustice in hyperbolic terms, in some ways naturalizing and mystifying the structural state, regional, and transnational forces at work. Although the films index unauthorized forms of “making it” within Egypt, they circulate comfortably within capitalist circuits in and outside Egypt. They do not express “national” messages in the sense implied in Egyptian films from the 1950s and 1960s or the tumultuous decade before the 2011 revolution. If they have anything to say about the nation, it is to point to widespread class-based despair and the potential of permanent crisis at the hands of disenfranchised masculine subjects. They do not stage or allow us to see what despair and crisis of disenfranchised female and nonheterosexual subjects look like. They privilege and make legible only hetero-masculine classed frustrations and suffering. While they communicate that the norms of morality and respectability will get the majority of poor Egyptians nowhere, we can reasonably ask whether poor and working-class Egyptian women are structurally situated to gain as much as poor and working-class men in this situation, particularly in the realms of sexuality and marriage.

Acknowledgments

I dedicate this article with love to my late father Fauzi Hanna Hasso. I am grateful to May Al Dabbagh, Mark Pedelty, and Sondra Hale for inviting me to present this work at various stages, and I appreciate the feedback I received on the first draft during a faculty seminar at NYU Abu Dhabi (March 2015) and at presentations at the Duke on Gender Colloquium (October 2015), the UCLA Von Grunebaum Center for Near Eastern Studies (May 2016), and the University of Minnesota Department of Communication Studies (December 2017). Although the translations are mine, I regularly turned to Zeinab Abulmagd, Mona Hassan, and Atef Said for connotations of colloquialisms and answers to my Cairo landscape questions. Kathryn Medien offered insightful feedback on an early version, and Nadia Yaqub's reading strengthened a late version. Hadeel Abdelhy completed impressive research in a compressed time period on Muhammad Ramadan's entire television and film oeuvre. During a 2018–2019 fellowship at the National Humanities Center (NHC), I benefited immensely from Weihong Bao's brilliant visual analysis based on watching the films without subtitles. I folded her suggestions into the paper at multiple points, and they influenced the ultimate argument. I am grateful to NHC staff members Brooke Andrade and Joel Elliott for acquiring one of the films and for their technical support. Joel Gordon of IJMES and two anonymous reviewers offered insightful feedback that helped bring the manuscript to its final form.