Introduction

According to the glossary definition (Reference O’Rourke, Oortwijn and Schuller1), health technology assessment (HTA) is a multidisciplinary process that uses explicit methods to determine the value of a health technology at different points in its life cycle. The most familiar form of HTA is work conducted by HTA agencies, on behalf of healthcare systems or other payers, to inform reimbursement or adoption decisions (including price negotiations). HTA is often used to inform decisions about the adoption, use, or pricing of pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and other technologies (defined widely in the HTA glossary definition) (2). However, HTA is also performed in earlier stages of the development of a technology to inform premarket decisions (Reference IJzerman, Koffijberg, Fenwick and Krahn3). This has been named “early HTA” or “development-focused HTA” and encompasses a broad range of work and technologies (Reference IJzerman, Koffijberg, Fenwick and Krahn3–Reference Stome, Moger, Kidholm and Kvaerner7). For example, early HTA could inform private or public innovators or investors during research into a new pharmaceutical, medical device, or diagnostic; innovators looking to improve hospital processes; or potential users in the early stages of development, looking into the design or alternative adoption strategies of an innovative health technology (Reference Bouttell, Briggs and Hawkins5;Reference Pietzsch and Pate-Cornell8). Early HTA can be conducted within healthcare settings as part of a broader hospital-based HTA (Reference Sampietro-Colom, Lach, Cicchetti, Kidholm, Pasternack and Fure9), for example, to help inform the in-house development of technologies, but is also performed within life science industries that supply technologies into the health system (Reference Partington, Crotty and Laver10–Reference Stome, Moger, Kidholm and Kvaerner13).

Early HTA is increasingly being used in all research and development phases, at different technology readiness levels. It has great potential to reduce research waste, ensuring that investment goes to technologies that are expected to create value, and are optimized to ensure they are fit for purpose (Reference Annemans, Callens, Crommelin, Guillaume and P14–Reference Wang, Rattanavipapong and Teerawattananon17). This focus on early assessment is in line with multiple policy initiatives from health systems and other payers set to provide information earlier in the life cycle on the potential value of a new technology to guide investment and assessment prioritization (18–21). Horizon scanning is the systematic identification of health technologies that are new, emerging, or becoming obsolete and that have the potential to affect health, health services, and/or society (22). Early HTA, on the other hand, refers to the assessment of these new and emerging technologies.

Often, stakeholders utilizing early HTA do not explicitly state that they consider their activity to fall within this remit and use other terms to describe it. For example, pharmaceutical companies use a range of “target assessment” frameworks in which important activities include the defining of unmet need and clinical differentiation (Reference Rodriguez Llorian, Waliji, Dragojlovic, Michaux, Nagase and Lynd23). Both activities form part of early HTA, often as a first step. Much early HTA, particularly that undertaken primarily to inform innovators, remains unpublished as it may be commercially sensitive (Reference Grutters, Govers and Nijboer24). Early HTA draws on a suite of complementary methods to assess the need for the innovation or develop target product profiles, such as interviews, expert (stakeholder) elicitation, and health economic modeling (Reference IJzerman, Koffijberg, Fenwick and Krahn3;Reference Grutters, Kluytmans, van der Wilt and Tummers4;Reference Stome, Moger, Kidholm and Kvaerner7;Reference Wang, Rattanavipapong and Teerawattananon17;Reference Bouttell, Briggs and Hawkins25). These methods can be used to explore the potential value of a technology in development using scenarios based on real-world settings, for example, reflecting alternative positions in a clinical pathway a technology could be used in, or considering alternative implementation contexts and the interoperability of a technology with existing health systems.

With increasing use of early HTA, there has been considerable debate over its precise definition, and if and how it differs from related concepts such as “early awareness,” “early dialogue,” “early (scientific) advice,” and “development-focused HTA.” Considering the multiple policy initiatives emerging in different parts of the world (18–21) and the heterogeneity in the field, clear guidance on terminology, methods, and reporting of early HTA would greatly assist practitioners, as well as journals seeking to ensure the quality of published work. The purpose of this study is to address the first of these issues and establish consistency in terminology. A working group under the HTA International Society (HTAi) was initiated to establish consensus on the definition of early HTA. This article reports the findings of this group and presents the first consensus-based definition of early HTA.

Methods and results

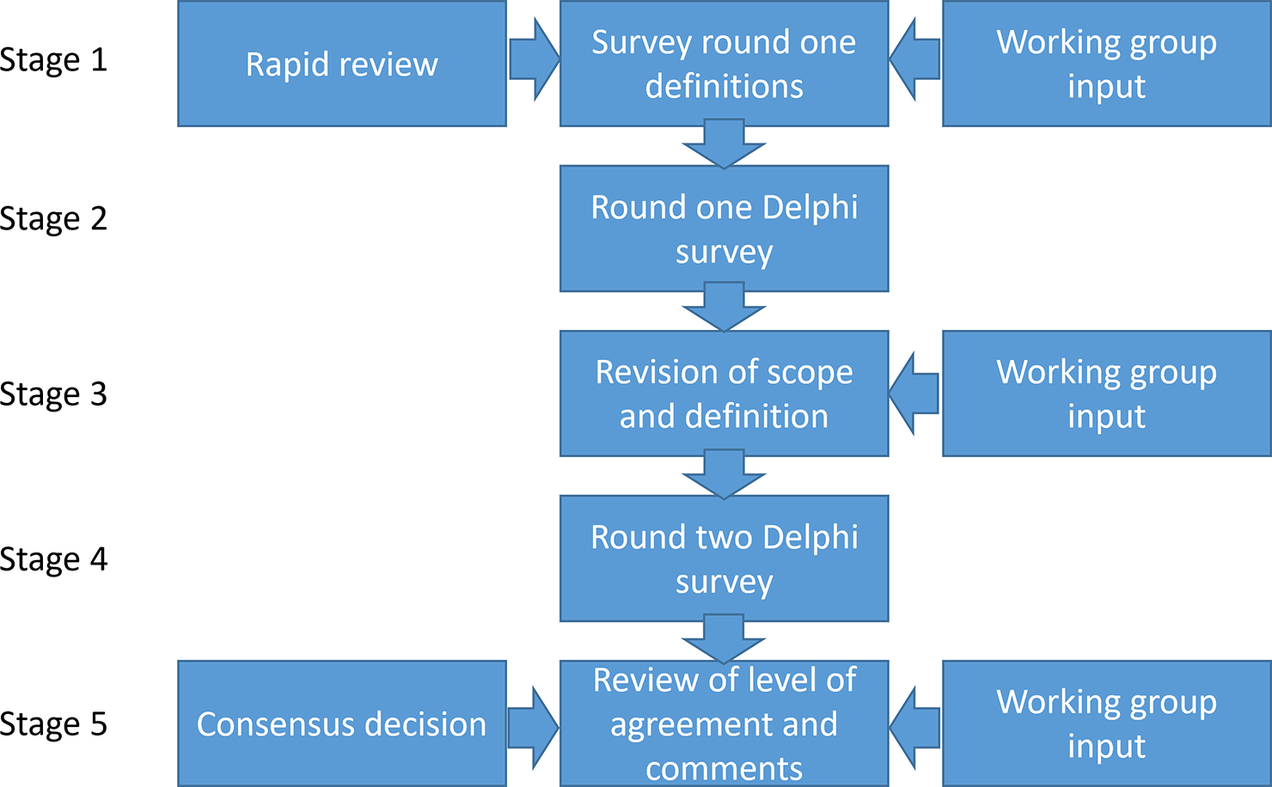

Our study used an iterative process comprising five stages of work undertaken by two bodies: the working group established under the auspices of HTAi and the panel who responded to the two stages of the consensus Delphi process. We chose to undertake a Delphi process as it is an appropriate method to reach consensus (Reference Junger, Payne, Brine, Radbruch and Brearley26). With the Delphi process, we wanted to reach as many people working in the field as possible. We report the methods and results of these stages chronologically, in line with the Guidance on Conducting and Reporting Delphi Studies (CREDES) (Reference Junger, Payne, Brine, Radbruch and Brearley26) (see Figure 1). The working group was established from a group of individuals interested in early HTA who were brought together by the first authors (JG and JB) following a call across their networks and to attendees of the HTAi Annual Meeting in the Netherlands in June 2022. Members of this wider group volunteered to join a terminology working group. Further members were added when it was formally accepted as a working group of HTAi in the summer of 2023. An advisory board was set up with five experts from different backgrounds. The total working group consisted of 17 core working group members and 5 advisory board members. These 22 people are referred to as the working group. The panel for the Delphi survey comprised all those who responded to the first round of the survey. The characteristics of both the working group and the panelists can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 1. Stages of the Delphi process.

Stage 1: development of definitions and supporting materials

Stage 1 started with a rapid review of reviews of early HTA, undertaken by JG in February 2023 based on an update of the search set out in Grutters et al. (Reference Grutters, Kluytmans, van der Wilt and Tummers4). Keywords were “(‘early health technology assessment’ OR ‘early evaluation’ OR ‘early assessment’) AND ‘methodology’ AND ‘review’.” The search added 85 articles to the previous review, of which 2 were considered relevant. Working group members were invited to add relevant review articles. A total of 11 articles were identified, including 9 separate definitions (Reference IJzerman, Koffijberg, Fenwick and Krahn3;Reference Bouttell, Briggs and Hawkins5;Reference Ijzerman and Steuten6;Reference Pietzsch and Pate-Cornell8;Reference Grutters, Govers and Nijboer24;Reference Fasterholdt, Krahn, Kidholm, Yderstræde and Pedersen27–Reference Rogowski, John, Ijzerman and Scheffler32). These were set out in the materials circulated in the first round of the Delphi survey (see Supplementary Materials). JG and JB developed an initial suggested definition based on the output from this review, as well as the HTA glossary definition of HTA (Reference O’Rourke, Oortwijn and Schuller1). These materials were then forwarded to the working group for their consideration. The working group decided to define the terms “early HTA,” “development-focused HTA,” and “early dialogue.” Other terms were used in the articles reviewed, but the working group preferred early HTA due to its prominence in the literature and development-focused HTA, as it captured the distinct nature of work undertaken to inform the development of health technologies. Early dialogue was included because when setting up the working group, there was much discussion about whether and how early HTA was different from early dialogue. Often used terms such as early economic evaluation or early health economic modeling (Reference Hartz and John28;Reference McAteer31;Reference Rogowski, John, Ijzerman and Scheffler32) were considered specific methods that could be used to inform early or development-focused HTA and were, therefore, not included in the scope of the study. The initial definition of early dialogue was taken from a recent publication by Blankart et al. (Reference Blankart, Dams and Penton33). To avoid bias, the first survey included a question asking panelists whether they agreed with the use of the terms we had suggested and asking for their own suggestions.

The first survey comprised background questions, definitions of “early HTA,” “development-focused HTA,” and “early dialogue”; a table setting out a detailed definition of early HTA in stages; and a table reconciling the suggested definition of early HTA with the nine definitions found in the rapid review. The full text circulated was refined iteratively through consultation with the working group. The final draft of the survey was piloted with five colleagues who were not involved with this work, and no changes to the context or structure were required. The survey, including the initial definitions, is included in the Supplementary Materials. The Supplementary Materials also include the characteristics of the working group and panelists who responded to the survey. A total of 13 members of the working group were panelists in Rounds 1 and 2. Their characteristics are included in all relevant columns.

Stage 2: Round 1 Delphi survey

A protocol for the Delphi study was developed by the working group (see Supplementary Materials). An ethical waiver was received from Radboud University Medical Center as no patients were included, and participation in the study was not associated with any risks or harms. The first round of the Delphi survey was circulated on 26 October 2023, with responses required by 24 November 2023. The survey was accompanied by an information sheet for participants (see Supplementary Materials). The survey started with an explicit consent statement that the respondents were asked to agree with. The purpose of the first round of the survey was to elicit qualitative comments rather than to seek consensus. We sought to reach a wide range of stakeholders with an interest in early HTA, including health policy makers and those in academia, HTA agencies, consultancy, and industry. As early HTA is an emerging field, we sought to be inclusive of all interested individuals regardless of their level of experience. We distributed the survey link through personal networks and social media and encouraged panelists to forward the survey link on to interested parties in their own networks. HTAi also distributed the invitation to all Interest Groups within their organisation and via their newsletter. Panelists in Round 1 were asked to provide their email address if they wished to be included in Round 2.

We received 133 responses to Round 1 of the survey; all of them gave informed consent. A total of 119 (of 133) panelists included their email addresses to be invited to participate in Round 2, and 114 panelists included free text comments for consideration.

In response to the question about whether panelists agreed with the use of the three terms we sought to define: “early HTA,” “development-focused HTA,” and “early dialogue,” many panelists found it difficult to distinguish between “early HTA” and “development-focused HTA.” Panelists felt that the concept of development-focused HTA covered the earliest stages of early HTA and that - if included - another complementary term covering the later stages of early HTA should also be included. There were contrasting views about the definition of “early dialogue” and they fit with early HTA. Multiple panelists regarded early dialogue as a method of stakeholder involvement used for early HTA. If it was a specific type of stakeholder involvement, as the proposed definition suggested, panelists suggested changing the term accordingly, for example, “early regulatory dialogue.”

In response to our question about any other suggested terms, panelists proposed 26 alternative terms, with 1 term, “developmental HTA,” suggested twice.

Stage 3: decision on scope and revision of definition

Stage 3 involved collaborative consideration by the working group of the feedback received from Round 1 of the survey and amendment of the definition of early HTA. At this stage, we also discussed the characteristics of the panel and identified some additional questions regarding the panelists’ characteristics that we wished to ask in Round 2. Given the responses on development-focused HTA being a subset of early HTA, the working group considered that introducing another complementary term covering the later stages of early HTA would create confusion. Hence, the working group decided to drop development-focused HTA and concentrate on the definition of early HTA, as the more comprehensive and recognized term. The working group also decided that, given the multiple policy initiatives in the area of early dialogue at present and the greater expertise elsewhere in HTAi on this topic, we would not seek to develop a consensus definition for this term. Regarding the alternative terms that were suggested by the panelists, many were suggested as mirror terms for development-focused HTA or to provide two terms to subdivide early HTA. In view of the absence of a dominant alternative, the working group decided to focus only on the definition of the single term “early HTA.”

The working group reviewed the responses, and the main themes were discussed at length. An iterative amendment process was undertaken, comprising a meeting of the working group and subsequent group emails, until the working group was satisfied that the definition reflected their understanding of early HTA. At this stage, we also consulted a panelist and a lexicographer who were involved in the HTA Glossary. Box 1 sets out the initial definition circulated with Round 1 and the final definition arrived at by the working group. Based on the advice offered, “HTA” appears as the first phrase in the definition to link directly to the overall definition in the HTA glossary. Early HTA is a subset of HTA, which means that concepts from the main definition, such as “to promote an equitable, efficient, and high-quality health system” are implied and, therefore, not required in our core definition. In the Supplementary Materials, we explain the working group’s responses to feedback received in the first round and how that was considered in the different aspects of the definition.

Box 1. Definition of early HTA included in the two rounds of the survey

Definition included in Round 1 of the Delphi survey

Early HTA is a formal, systematic, transparent, and multidisciplinary process that uses explicit methods, both quantitative and qualitative, to explore the potential and/or expected value of a health technology*, including the associated uncertainty, before or alongside the technology development process. Stages at which early HTA can be undertaken include the concept/discovery stage, prototype/proof of concept stage, and research/evidence development stage. The stages have an impact upon the evidence/data available, the questions to be answered, the methods to be used, and the audience for the work. The purpose is to provide innovators with insight about the potential value** for the health system and commercial viability of a technology, and to inform decision making about the (clinical) need, design of a technology, positioning of the technology in the care pathway, further research needed to prove value, and potential for future market access and adoption, to promote a high-quality health system.

* A health technology is an intervention developed to prevent, diagnose, or treat medical conditions; promote health; provide rehabilitation; or organize healthcare delivery. The intervention can be a test, device, medicine, vaccine, procedure, program, or system (definition from the HTA Glossary; http://htaglossary.net/health+technology).

**The dimensions of value for a health technology may be assessed by examining the potential intended and unintended consequences of using a health technology compared to existing alternatives. These dimensions often include clinical effectiveness, safety, costs, and economic implications; ethical, social, cultural, and legal issues; organizational and environmental aspects, as well as wider implications for the patient, relatives, caregivers, and the population. The overall value may vary depending on the perspective taken, the stakeholders involved, and the decision context

Accepted consensus definition

Early health technology assessment

A health technology assessment (HTA) conducted to inform decisions about subsequent development, research, and/or investment by explicitly evaluating the potential valueFootnote 1 of a conceptual or actual health technologyFootnote 2.

1 The dimensions of value for a health technology may be evaluated by examining the intended and unintended consequences of using a health technology compared to existing alternatives. These dimensions often include clinical effectiveness, safety, costs, and economic implications; ethical, social, cultural, and legal issues; organizational and environmental aspects, as well as wider implications, for example, for the patient, relatives, caregivers, innovators, and the population. The overall value may vary depending on the perspective taken, the stakeholders involved, and the decision context.

2 An intervention developed to prevent, diagnose, or treat medical conditions; promote health; provide rehabilitation; or organize healthcare delivery. The intervention can be a test, device, medicine, vaccine, procedure, program, or system.

Stage 4: Round 2 Delphi survey

In the second round of the survey, we asked participants to respond on a Likert scale to indicate whether they strongly agreed, agreed, were neutral, disagreed, or strongly disagreed with the definition. They were asked to provide comments to support their responses. Participants who had provided their email addresses in Round 1 were sent a personal link to complete Round 2. As prespecified in the protocol, we considered consensus reached if 70 percent of panelists or more either strongly agreed or agreed with the definition. Panelists were asked to provide their name and affiliations if they wished to be acknowledged in this article. In addition, we asked them questions about their geographical background and follow-up questions about their expertise in (early) HTA.

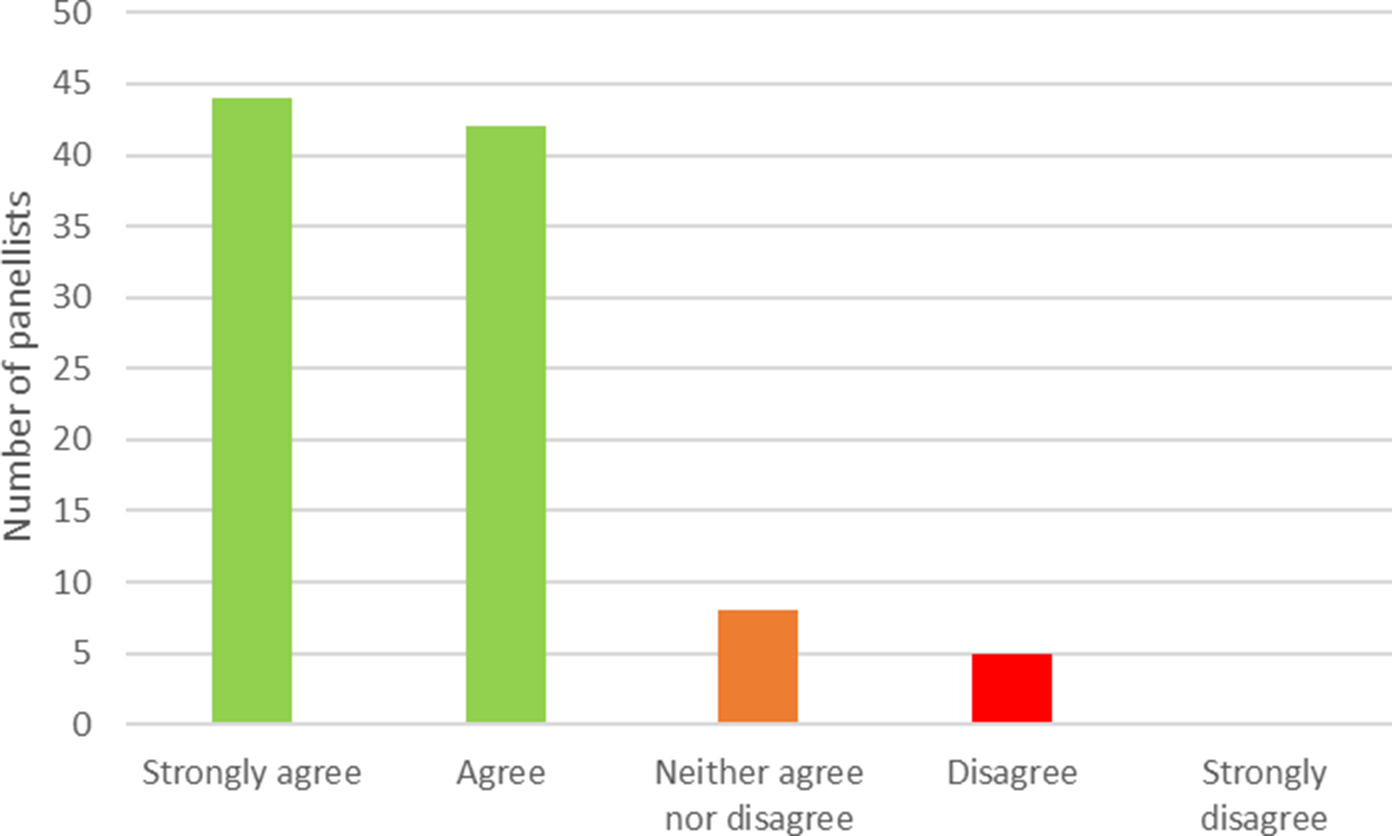

Of the 119 panelists who provided their email addresses in the first round, 99 (83 percent) took part in the second round. Figure 2 shows the level of agreement reached in the second round. In total, 86 (87 percent) panelists either strongly agreed or agreed with the definition. This compares with a consensus threshold of 70 percent set in our protocol. Eight panelists (eight percent) neither agreed nor disagreed, and five (five percent) disagreed. Of the 13 members of the working group who were also panelists, 5 agreed and 8 strongly agreed with the definition. Excluding these 13 individuals results in a level of agreement of 85 percent, with 73 panelists agreeing or strongly agreeing from a total of 86. Excluding panelists with no experience of either early HTA or early dialogue, the level of consensus is 88 percent.

Figure 2. Level of consensus on the provided definition of early HTA. HTA, health technology assessment.

Stage 5: decision on consensus

In the fifth and final stage of the study, the working group considered the responses to the second round and decided whether any further amendment was required. The working group unanimously concluded that, given the strong level of agreement, the second definition, set out in Box 1, would be adopted as the consensus definition. Free text comments from the second round of the survey focused on three key areas: what early HTA can and cannot do; confusion with or between early dialogue/early awareness/early scientific advice, and the timing of early HTA.

What early HTA can and cannot do

One panelist commented that early HTA cannot include early ethical, social, cultural, legal, organizational, and environmental aspects. The working group felt that early HTA can consider these elements and that it was important to emphasize the relevance of exploring these aspects at an early stage of development to anticipate later issues, even though this is currently not often included in early HTA (Reference Smits, Ludden, Verbeek and van Goor34). Another panelist expressed concern that early HTA would be “inaccurate” due to a lack of detail and a fast-moving environment. The working group felt that this comment misunderstood the purpose of early HTA. Given the purpose of early HTA is to inform decisions about subsequent development, research, and/or investment, an early HTA would highlight a fast-moving therapeutic or competitive environment and incorporate this uncertainty into analyses. Although it could be argued that all HTA is, on some level, imprecise, economic evaluation as part of early HTA does not typically give a definitive answer to a binary question about whether a health technology is cost-effective or not. Rather, it is intended to identify the key parameters that will influence cost-effectiveness and provide some guidance about threshold levels of performance that may be required for a technology to add value. Understanding the needs of stakeholders for a technology and the conditions under which it can provide value for money is particularly important in fast-moving therapeutic and competitive environments.

Confusion between early dialogue/early awareness/early scientific advice

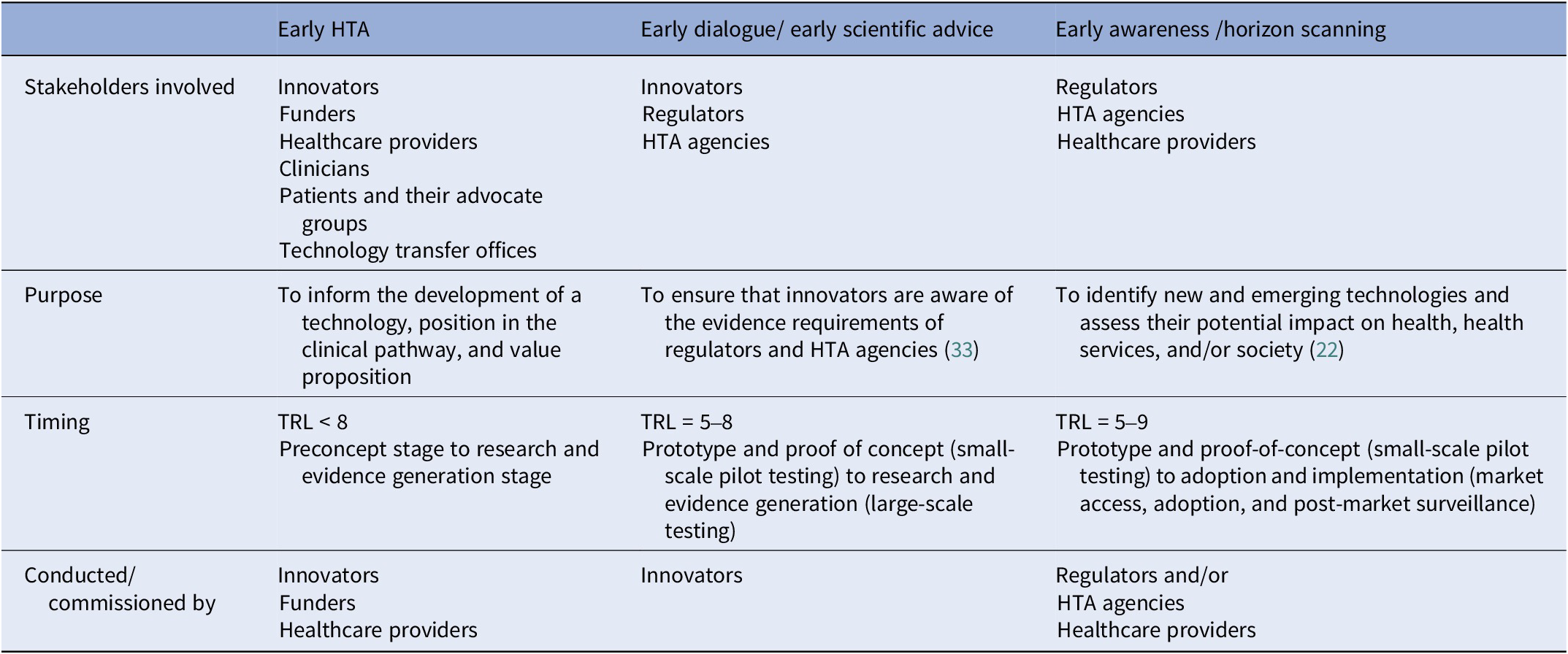

The responses highlighted some confusion on how early HTA relates to early dialogue, early awareness, and early scientific advice. Possibly, this is because early HTA undertaken within companies or on innovators’ behalf by consultants and academics is largely unseen. Panelists from HTA agencies are aware that their own or associated agencies’ horizon scan for emerging technologies (early awareness) and engage with innovators to discuss process and evidence requirements (early scientific advice). They may be less aware of early HTA, which occurs at a much earlier stage of development than these activities and is not readily visible to them. Since early dialogue explicitly concerns the interaction between the innovator and HTA agency and/or regulatory body, it is different from the method of stakeholder involvement that can be used as a qualitative method for performing an early HTA, which generally includes a broader set of stakeholders. Table 1 gives an illustration of the working group’s view of how these activities relate to early HTA.

Table 1. Relationship between early HTA, early awareness, and early dialogue/scientific advice

HTA, health technology assessment; TRL, technology readiness levels

Timing of early HTA

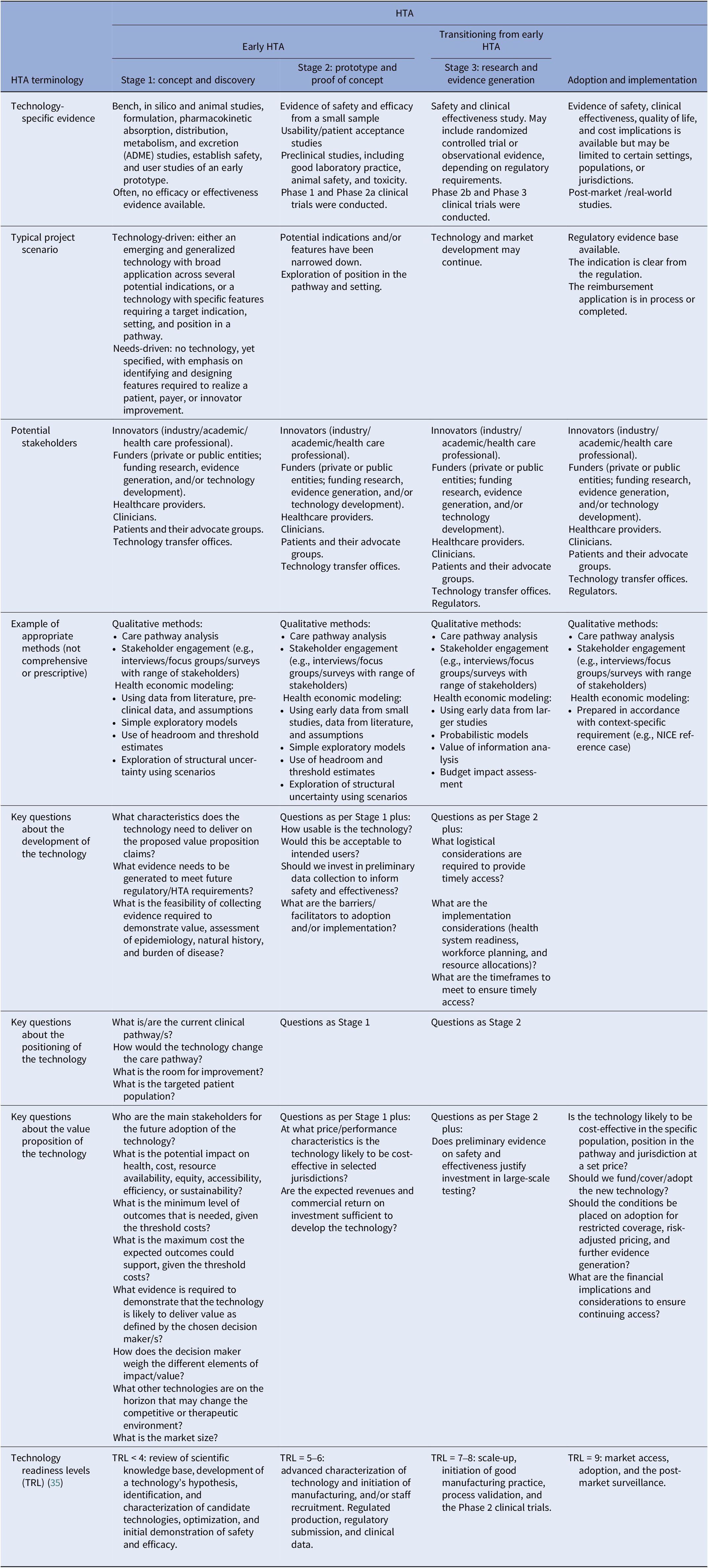

Some panelists felt it was important to specify in the definition at what stage an HTA is “early,” in contrast to “not early” HTA. The working group felt that the only clear distinction between early and other forms of HTA relates to the decision problems that the respective assessments are intended to inform. The second definition (Box 1) is structured to place early HTA as a subset of HTA with a clear purpose that is different from, for example, HTA performed to inform reimbursement decisions. Further details provided in Table 2 illustrate the typical timing of early HTA. Panelists felt it would be useful to be explicit about several aspects of early HTA, such as who requests, carries out, and pays for the HTA; what the outputs are; whether the process is confidential; and the role of the HTA agency. The working group acknowledged the relevance of these questions, but noted that the answers will vary. For example, early HTA activities can be performed by a consultancy company to inform an innovator about the potential value for money of their technology or idea, in which case it will be paid for by the innovator, and the process is probably confidential. However, early HTA could be facilitated by an academic expert, paid for by a public research funder, to inform decisions on funding a clinical study on a new technology. We added details covering these points to Tables 1 and 2. Although the aim of the Delphi survey was to adopt a broad definition of technology and to make the definition of early HTA technology agnostic, we acknowledge that some technologies, such as orphan drugs, digital health, or service innovations, may deviate from standard health technologies, and our general descriptions may not capture every nuance.

Table 2. Additional detail by stage of technology development

HTA, health technology assessment; TRL, technology readiness levels.

Additional details on the stages of early HTA

In the first round of the survey, we included a detailed table that delineated early HTA into three stages, shown alongside the phases of development of a technology (see Supplementary Materials). We amended the table in response to the feedback in Round 1 (Table 2). Specific changes include a recognition that, as the development of the technology proceeds into what we have termed “Stage 3: research and evidence generation,” HTA can still be early, but it does not necessarily have to be, depending on the purpose of the assessment. If the purpose of HTA activities at this stage is to inform risk sharing and ongoing monitoring arrangements as part of reimbursement/adoption decisions rather than to directly inform decisions to adapt or develop the technology, it is no longer deemed early. We also added details of typical methods at each stage of development, including some comments on how uncertainty may be explored, as this was a common request in the feedback to Round 1. It should be noted that these are examples only and not intended to be exhaustive or prescriptive. Table 2 should not be seen as part of the consensus definition, as it was not included in the second round. However, we felt it addressed most of the comments that were made on the definition in Round 2 of the Delphi process.

Discussion

We undertook a five-stage process, including a two-round Delphi survey, which produced consensus on a definition of early HTA. Based on this process, early HTA is defined as “an HTA conducted to inform decisions about subsequent development, research, and/or investment by explicitly evaluating the potential value of a conceptual or actual health technology”. A total of 11 previous articles had suggested 9 definitions for early HTA or related terms (see Supplementary Materials) (Reference IJzerman, Koffijberg, Fenwick and Krahn3;Reference Bouttell, Briggs and Hawkins5;Reference Ijzerman and Steuten6;Reference Pietzsch and Pate-Cornell8;Reference Grutters, Govers and Nijboer24;Reference Fasterholdt, Krahn, Kidholm, Yderstræde and Pedersen27–Reference Rogowski, John, Ijzerman and Scheffler32). Several of these definitions were limited to the health economic modeling component of early HTA (Reference Hartz and John28;Reference McAteer31;Reference Rogowski, John, Ijzerman and Scheffler32), whereas our definition considers wider implications by incorporating the note from the HTA glossary definition of HTA on the dimensions of value, albeit slightly amended to include implications for the innovator. Pietzsch and Pate-Cornell (Reference Pietzsch and Pate-Cornell8) and Ijzerman and Steuten (Reference Ijzerman and Steuten6) both recognize that the purpose of early (health) technology assessment is to inform future development, with the former explicitly recognizing that investment and design decisions may be informed. Ijzerman et al. (Reference IJzerman, Koffijberg, Fenwick and Krahn3) explicitly recognize that industry may be the primary audience defining early HTA as “all methods used to inform industry and other stakeholders about the potential value of new medical products in development.” Fasterholdt et al. (Reference Fasterholdt, Krahn, Kidholm, Yderstræde and Pedersen27) defined early assessment as “being performed when the initial selection of ideas or rough prototyping has taken place, but before large-scale testing or traditional clinical research. Hence, early assessment is based on data from early phases, that is, feasibility, pilot, or initial effect data.” This focus on a specific stage in development or the un/availability of specific data is useful in the definition of early HTA, and we have included both aspects in our detailed table (Table 2); however, the working group felt that the distinctive feature of early HTA is that it is intended to inform decisions around development, research, and investment decisions. The availability or otherwise of data is not a defining characteristic of early HTA.

We present the first consensus-based definition of early HTA. The strengths of our approach are the extensive experience and different perspectives represented in our working group and by our Delphi panel members. We have representation from most geographic areas, although we acknowledge that there is a preponderance of involvement from Europe and Australia. Although there is no recognized standard for the conduct or reporting of consensus exercises such as ours, we have followed the CREDES best practice guidelines (Reference Junger, Payne, Brine, Radbruch and Brearley26). We set out our methodology in our protocol, worked under the oversight of the Scientific Development and Capacity Building Committee of HTAi, and have reported all aspects of our process transparently. Our study has a number of limitations. Both the working group and the Delphi panel had a strong representation from Australia and Europe. Moreover, most of the working group members and panelists were from academia and mostly had experience with quantitative methods. This is not surprising, given that most early HTA activities focus on health economics and are performed in Europe and Australia. Both the working group and panel were open to anyone interested, and we did not have a predefined threshold for the representation of certain stakeholders, regions, or experience. Our panel and working group thereby seem to be a good representation of the current interest in and use of early HTA.

The development of this consensus definition of early HTA is important because it provides clarity and raises the profile of the field. Although it fits within the umbrella definition of HTA developed by an international joint task group co-led by the International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment and HTAi (Reference O’Rourke, Oortwijn and Schuller1), it does suggest an extension of the concept of “value” in that definition to include wider implications for innovators. It also makes clear that early HTA is not restricted to the activities of HTA agencies but involves a wide range of actors from the very earliest stages and may precede the development of the technology itself, with much work remaining unpublished and potentially “below the radar.” It clearly distinguishes early HTA from related but distinct activities of early awareness and early dialogue/early scientific advice. Developing a consensus definition of these terms was beyond the scope of this study, but it would further clarify the differences between the activities. We urge authors to identify their papers as early HTA, where appropriate, and use our detailed table (Table 2) to report the stage of development of the technology and the level of evidence available. We encourage journal editors to reinforce the use of this uniform terminology to improve visibility. Next steps for our group include the submission of the consensus definition to the HTA glossary and working on methods and reporting of early HTA. In developing methods, it will be useful to relate early HTA to other fields of research, such as bioethics, philosophy of technology, responsible research and innovation, and decision making under deep uncertainty. In addition, we stress that, like all definitions, this is a “living” definition that may need to be updated in time to reflect the evolution continuously happening within the field of HTA.

Early HTA is performed to inform decisions about development. It provides an opportunity to assess the potential value of innovation before significant funds are committed, thus guiding investment decisions. We also advocate the adoption of an early HTA approach in a proactive sense to identify and describe specific clinical needs and the technology features required to meet them. Furthermore, early HTA provides the opportunity to ensure that technology is optimally designed and positioned to deliver the most value to a diverse range of stakeholders, including the innovators themselves, whether they are working within the healthcare system or in the industry. Early HTA, like HTA as a whole, seeks to promote an “equitable, efficient, and high-quality health system.”

Conclusion

In this article, we have reported a five-stage process, including a two-round Delphi survey that developed and reached consensus on a definition of early HTA, which is “an HTA conducted to inform decisions about subsequent development, research, and/or investment by explicitly evaluating the potential value of a conceptual or actual health technology.” By providing a consensus-driven definition of early HTA, we hope to enhance uniformity and harmonization of terminology. In addition, we hope to lay the foundation for more discussion, research, and method development in this important field.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462325100123.

Acknowledgments

This work is the result of a working group established within the Health Technology Assessment International (HTAi: https://htai.org/engage-with-us/working-groups/). The authors would like to acknowledge the Delphi panelists who participated in the project. Panelists who agreed to be named are listed in the Supplementary Materials. The HTAi Scientific Development and Capacity Building (SDCB) Committee provided a thorough review of the concept and the draft manuscript, offering valuable comments and suggestions. The authoring team is solely responsible for the final content.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and not of their employers or funders.

Funding statement

Dalia Dawoud: This work was partly supported by funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement number 82516 (Next Generation Health Technology Assessment (HTx) project).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.