Introduction and literature

Considering their symbolic importance and enduring material legacy, that British trade union banners have received little specific recent attention in the academic literature is something of a mystery.Footnote 1 Pioneering studies of British trade-union banners—most notably John Gorman's Banner Bright (1973) and W.A. Moyes's works on Durham miners’ banners—were an element of the emerging “new labour history,” forming part of a wider research agenda into trade union iconography.Footnote 2 A “second wave” of interest in British union banners came with the People's History Museum's National Banner Survey of 1999. This compiled details of some 2,400 plus banners (four hundred of which were in the museum's own collection). The survey provided objects for research inspired in part by the re-reading of material culture offered by poststructuralist-informed revisionist accounts of nineteenth-century popular politics in the 1990s.Footnote 3 Apart from this, the practical possibilities of using banners as educational resources have been discussed; banners have been examined from an anthropological perspective in the context of Northern Irish sectarianism as well as trade unionism and mid-1980s Scottish strikers’ testimonies have been deployed to explore how banners can be used to construct working-class solidarities.Footnote 4 Finally, there has been a fairly steady flow of more popular, and often good quality, studies of British trade union banners since the mid-1980s, as well as a second edition of Gorman's book in 1986, all inspired to some degree by the national miners’ strike against the Thatcher government's mine closures program.Footnote 5

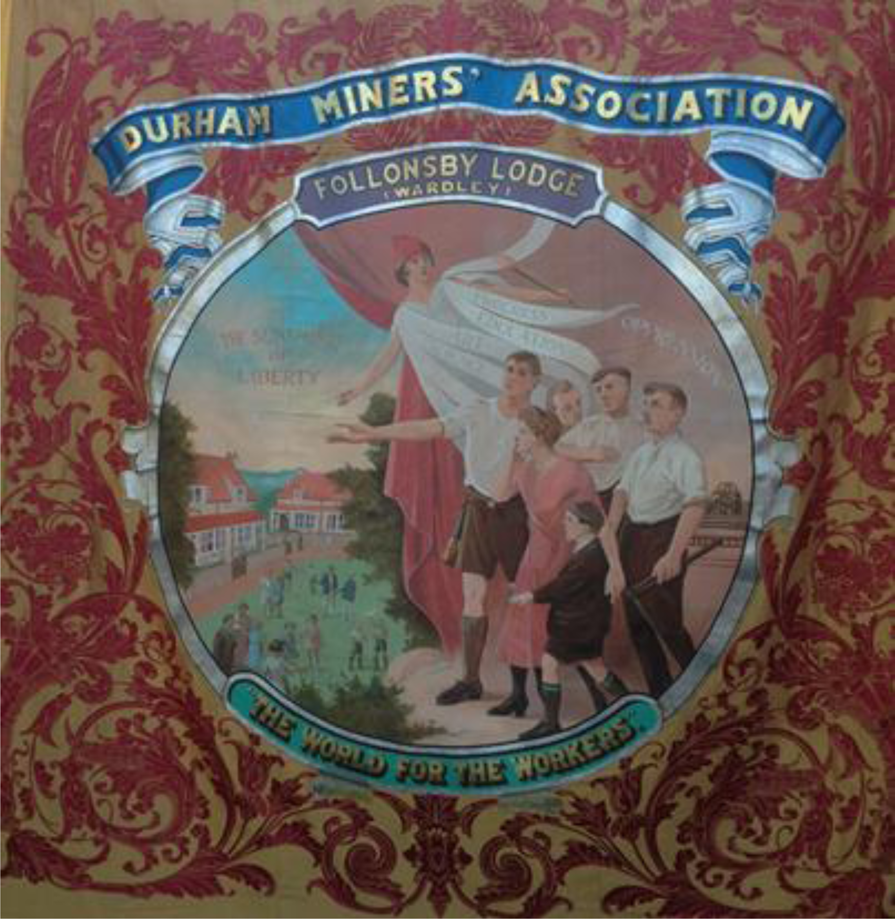

Living evidence of the diversity as well as the ongoing political and cultural significance of trade union banners is offered in the city of Durham every second Saturday in July, at the annual Durham Miners’ Gala.Footnote 6 Trade union banners old, new, and reborn are paraded through the city's crowded labyrinthine streets in a procession toward the racecourse and the so-called “Big Meeting,” a name as apt for the gala now as it was in the Durham coalfield's heyday of peak production in 1913.Footnote 7 A regular feature since 2011 among the gala's color and sound is a reproduction of the (in)famous Follonsby miners’ banner. Follonsby colliery and lodge (local miners’ union branch) were located in a pit village called Wardley, on the northern edge of the Durham coalfield and close to the south bank of the river Tyne that serves Newcastle (situated on its north bank).

The first incarnation of the “red” Follonsby banner was unfurled in 1928. With its centerpiece portrait of Lenin, it represented defiance in defeat (of the 1926 miners’ lockout), a militant call to arms in its aftermath, and an apparently shocking new left turn away from the Durham coalfield's traditional moderation and liberalism that was reflected in the dominant themes of its lodge banners’ iconography hitherto.Footnote 8 Indeed, Gorman later dubbed the Follonsby banner “implicitly, what must be the most revolutionary banner yet unfurled by a union,” presumably assuming the self-evident veracity of this claim.Footnote 9

In the context of a mass trade unionism that is characterized in Britain by a general tendency to conciliation and a reluctance to engage in “politics”—theorized as Lewis Minkin's “rules”—Gorman's important but unsubstantiated claim is clearly worthy of further interrogation.Footnote 10 Second, in the context of the coal miners’ unions specifically, it takes on further salience, considering, on the one hand, debates about coal miners as the archetypal proletarians and the “myth of the radical miner” and, on the other, that (industrially “militant” or not), the British miners’ union did not itself stray from Minkin's “rules” apart from the period between the beginning of the 1974 and the end of the 1984/5 national miners’ strikes.Footnote 11 Third, at regional level, the striking fact that this “revolutionary” banner emerged in the “moderate” Durham coalfield suggests a need to re-think the political legacies of this significant (post)industrial region.Footnote 12 Interrogating Gorman's claim about the Follonsby banner is a means of exploring what “revolutionary” meant in the context of the banner's birth, and how meanings have been established and understood differently at various political junctures since.

Methodologically, this research draws in general terms on the “material turn” in cultural studies.Footnote 13 More specifically, it is inspired by and builds on Dave Douglass's work, and that of David Wray, published in this journal, which uses many Durham miners’ lodge banners to throw light on the changing political culture of the coalfield.Footnote 14 This article offers an analysis of material culture that traces the life of a specific artifact, rather than an individual, an idea, or a movement. Maintaining a sharp focus on the images depicted on—and the material history of—a single miners’ banner fosters the linking of the micro histories, politics, and struggles of local activists with a much broader story about modern British labor history. It is a story that connects radical trade union activism of the pre-Great War period with the labor struggles of the interwar years, the working-class intellectual culture of History Workshop, and the later twentieth-century British Left with the contemporary Durham Miners’ Gala (an annual event that itself dates back to 1871). This approach also offers a pathway into debates around some of the central questions of revolutionary theory and action. The Follonsby banner is, then, at one and the same time a context-specific declaration of ambiguous (and contestable) revolutionary intent and a palimpsest of changing political attitudes, understandings of historical figures, nostalgia, and political recuperation.

The following section contextualizes and explains the creation of the 1928 red Follonsby banner and its iconography. The subsequent section then traces the banner's lives, through its second incarnation, its postwar years of purgatory, and its afterlife from 2011, while the third interrogates the claim that the Follonsby banner is the most “revolutionary” of British trade union banners. The argument is, narrowly, that the banner has a strong (though contestable) claim to be regarded as the most revolutionary in Britain, albeit with “revolutionary” understood in certain theoretical and context-specific ways. More broadly the article argues that the Follonsby banner is rather more significant for what this process of interrogating its claim to revolutionary credentials reveals about the complexities of the political culture of the mainstream British Left, rather than in its individuated existence as a curious, “extreme” outlier. In short, for all its apparent exceptionality, the Follonsby banner's iconography, birth, life, rebirth, and afterlife render it curiously, and importantly, emblematic.

The first “red” Follonsby banner: Contexts and protagonists

In 1928, British trade unionism was on the defensive and losing its hold on the workforce. Overall membership was declining from a 1920 peak of 8.35 million (m), representing 45.2 percent of the entire workforce, to 4.86 m (25.7 percent of the workforce) in 1929.Footnote 15 The mighty Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), which had organized the biggest strike in history in 1912, for a national miners’ minimum wage, operated in the only postwar British industry to employ over one million workers.Footnote 16 The largest and best organized element of the British trade union movement (notwithstanding aims to centralize that came to partial fruition with the advent of the National Union of Mineworkers in 1945), the MFGB had seen its membership peak at 0.95 m in 1920, only to drop away to around 0.53 m by 1930.Footnote 17 At its peak in 1920, the MFGB was the single largest mining union on the planet. Its members represented a full 35 percent of total affiliated membership at the 1920 Miners’ International Conference. The next largest were the German miners with a 0.77 m membership (30 percent) while the American miners were ranked third with 19 percent.Footnote 18 In early 1926, the long-established and deeply entrenched Durham Miners’ Association, operating in the second largest British coalfield, was the best organized of the MFGB's affiliates. It had three thousand more members than there were working miners in the coalfield, rendering the exceptional Durham mining workforce 101.8 percent organized.Footnote 19

Still Britain's most important industry, coal mining was under increasing threat from oil and suffering from chronic underinvestment, fragmentation, and a weak export market flooded by cheap German coal. Rendered even more uncompetitive by an overvalued sterling's return to the Gold Standard in April 1925, coal was, unsurprisingly, at the center of British industrial unrest in the tumultuous early postwar period. The miners suffered two devastating defeats after a fleeting moment of apparent triumph in 1919, when Lord Sankey, heading a royal commission, recommended that the coal industry be fully nationalized, a long-advocated miners’ aim. Prime Minister Lloyd George seized on the commission's lack of unanimity to reject this proposal. In 1921, after the end of the postwar boom, the miners were faced with the phasing out of state control and attendant subsidies and a return to private ownership accompanied by district agreements and a sharp cut in wages (of up to 49 percent in South Wales). Abandoned by their “Triple alliance” union allies (the transport workers and railway men) on Black Friday, April 15, 1921, the locked-out miners were starved into accepting worse terms than offered at the outset. That the fall of around 35 percent in miners’ wages over the course of 1921 was soon echoed by falling wages in other industries boosted inter-union solidarity. Four years later, on “Red Friday,” July 31, 1925, a more pugnacious Trades Union Congress (TUC) general council backed the miners in renewed struggle against further proposed wage reductions and a longer working day. A nine-month government subsidy bought time for the inconclusive Samuel Report, and for the government to prepare for mass industrial action. There followed nine days of general strike ended by a humiliating TUC leadership climbdown in May 1926, and a bitter miners’ lockout that finally ended in defeat in December 1926.Footnote 20 In total, 162.23 m working days were lost to strikes in Britain in 1926 thanks to this dispute; almost double the next largest figure of 85.87 m in 1921.Footnote 21 In this context, the unfurling of the red Follonsby banner in the depressed and defeated Durham coalfield in 1928 was an act of both dissent and of hope.

The 1928 Follonsby miners’ banner was the third of three red Durham miners’ banners of the interwar period (discussed further below). On the banner's front were five portraits: the centerpiece was Lenin, with a scroll underneath emblazoned with his name. Below Lenin was a line from William Morris’ poem “The Day is Coming”:

To Lenin's bottom left (positions are always taken from the perspective of the banner carriers) was the then miners’ leader A.J. Cook; above him Keir Hardie and top right James Connolly. Finally, bottom right was a portrait of George Harvey, the local lodge secretary and Follonsby miners’ leader since 1913. While a lodge “full general meeting” apparently decided who would feature on the newly designed Follonsby red banner, the complexities and context of Harvey's political development were central to explaining the presence of the other four portraits.Footnote 22

Keir Hardie's portrait represents Harvey's earliest political commitment. Hardie was a Scottish miners’ leader and Labour representation pioneer who founded the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in 1893. Regularly voted by DMA lodges as a speaker for their annual gala before 1914, Hardie's antimonarchist, socialist rhetoric embarrassed the Liberal-dominated DMA officials and must have helped to galvanize a younger generation of Durham miners, who then formed and led the coalfield's influential minimum-wage mass movement. Born into a coal mining family in 1885, in the Durham pit village of Beamish, itself close to the militant heart of the Durham coalfield, Harvey was active in Socialist politics by the age of seventeen.Footnote 23

James Connolly's banner portrait represented the radicalization of Harvey's politics that came only five years later, after he secured a full-time scholarship to study at the trade union-sponsored Ruskin College, Oxford, 1907–1908.Footnote 24 Connolly, born to working-class Irish immigrant parents in Edinburgh in 1868, became, like Harvey, involved in the ILP before emigrating to America in 1903. After working with Marxist Daniel de Leon's Socialist Labor Party (SLP) and in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), Connolly moved to Dublin in 1910, playing a key role in the 1913 Dublin lockout and helping form the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) to offer workers’ armed defense. Opposing the First World War on Marxist grounds, Connolly's ICA formed part of the force that held Dublin from April 24, 1916, for six days. Along with fifteen other Easter Rising leaders, a severely wounded Connolly was executed by the British on May 12, 1916, tied to a chair.Footnote 25

At Ruskin, Harvey joined the SLP's British sister party, likely influenced, according to historian Ray Challinor, by Marxist Ruskin tutor and South Wales autodidact miner Noah Ablett, then an SLP activist.Footnote 26 On returning to the pit, Harvey's newfound zeal was integral to making his local SLP branch the most active in the region.Footnote 27 From April 1909, Harvey also began contributing regularly as mining correspondent to the SLP journal The Socialist.Footnote 28 The political turmoil in the Durham coalfield engendered by new shift systems from 1910 and then in the campaign for a minimum wage from 1911—opposed vigorously by the DMA's Liberal fulltime officials—offered ample propaganda opportunities. Harvey exploited them brilliantly, publishing a full-length, well-received pamphlet in 1911, and then furthering his political agenda in his year's tenure as national editor of The Socialist, 1911–1912.Footnote 29

In 1912, Harvey addressed ever-larger mass meetings of Durham miners, received greater local press coverage, and launched his own SLP-inspired “industrial unionist” coalfield group. Harvey also began working with Will Lawther, another leading Durham miner syndicalist and also recently radicalized while studying at Central Labour College, the Marxist off-shoot of Ruskin.Footnote 30 Harvey's profile rose further when he appeared in court in November 1912, accused of libeling DMA general secretary and Liberal MP John Wilson in his second propaganda pamphlet.Footnote 31 Harvey defended himself and the judge found in favor of Wilson, awarding £200 in damages.

Nevertheless, the trial afforded Harvey an excellent propaganda platform, securing fresh support that enabled him to launch a new Durham Mining Industrial Union Group in its aftermath.Footnote 32 The extent of Harvey's standing was evident in March 1913, when he was elected checkweighman on a militant platform, telling the Follonsby miners: “If you want a gentle Jesus, Temperance preacher, for God's sake don't consider me as likely to suit.”Footnote 33

Elected by the miners, the checkweighman literally checked the weight of tubs of coal at the pithead and was one of the most important and trusted miners in any Durham colliery.Footnote 34 Given Harvey's lack of lodge official experience, his age (only twenty-eight), his outspoken militant policy, and Follonsby's distance from Harvey's stomping ground around the Durham market town of Chester-le-Street, this was a remarkable achievement. Harvey continued most of his earlier propaganda activities into the war, including publishing several pamphlets from 1917–1918.Footnote 35 That Harvey was becoming more prominent inside the DMA was demonstrated in April 1915, in his lead role campaigning against acceptance of a derisory wages offer. On this he won a short-term victory.Footnote 36 Elected lodge secretary in 1916, Harvey consolidated his grip on Follonsby lodge's politics and cemented his reputation among the men as a dedicated and highly talented militant.Footnote 37

While a de Leon-like divisiveness and sectarianism occasionally characterized Harvey's writing and activities, there are probable reasons why Connolly's image, rather than de Leon's, made it onto the Follonsby banner.Footnote 38 Though Harvey himself had no direct Irish roots, the cause of Ireland resonated strongly in the locality of Follonsby lodge. It was located near the Tyneside town of Jarrow, which had seen considerable Irish immigration in the nineteenth century. Drawn to coal mining and shipbuilding, the descendants of Irish immigrants retained their former cultural and political practices and ties to a considerable degree.Footnote 39 It was known as the Irish Labour Party (ILP) in that part of South Tyneside and the local party color was green rather than red.Footnote 40 In his early postwar rank-and-file activism, Harvey was clear that the “strongest part of the [rank-and-file miners] movement here is that composed of Irish people.”Footnote 41 Indeed, in movement conference resolutions that congratulated “the Irish working class upon their noble and most gallant stand against the Black and Tans” and called for an Irish Workers’ Republic, it was clear to the Home Office that Harvey was “making a special effort” to win Irish workers to his militant cause.Footnote 42

There was surely a more personal link as well. Connolly was printing The Socialist on his press in Dublin at the time Harvey edited it.Footnote 43 Finally, Connolly was not only (and unlike de Leon) an (albeit controversial) revolutionary martyr after 1916; Connolly was also—perhaps paradoxically—rather more pragmatic than de Leon. Harvey's altering the SLP policy before the Great War to allow him to stand for elected office inside his union, as well as—as we shall see—the development of his postwar political practice, suggested that he shared rather more of Connolly's pragmatism than de Leon's dogmatism.Footnote 44

Lenin's image represents Harvey's move away from the SLP and into the orbit of the organization that superseded it, the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), soon after its founding in July 1920. The bulk of the SLP membership made the same switch. That Lenin apparently claimed that the Bolsheviks had applied de Leon's interpretation of Marxism, and that Ray Challinor wrote (controversially) that the SLP represented the Origins of British Bolshevism, only underscored the apparent lack of political distance between Harvey's (pre-1918) politics and Lenin's.Footnote 45 There was continuity in Harvey's industrial practice as well: He adopted a militant stance in national miners’ wage negotiations in September 1920, and took the fight back to the supine DMA leadership that had voted for conciliation, contrary to their mandate from union members.Footnote 46

The apparent failure of the MFGB to hammer home its advantage in the wages dispute with the government in 1919–1920 catalyzed the grassroots emergence of Communist-inspired “Unofficial reform” groupings in many coalfields. Harvey was immediately a leading figure in the Northern section of the miners’ Unofficial Reform Movement (NURM) from early January 1921, trying to radicalize the MFGB and get it to affiliate to the Soviet “Red” International of Trade Unions. Harvey was feverishly active in the NURM throughout and beyond the 1921 miners’ lockout, though repeated efforts to galvanize local rank-and-file solidarity action among the miners’ comrade unions of the Triple Alliance failed, as they had at a national level.Footnote 47 With defeat and postwar slump came disenchantment. By December 1921, even Harvey's own local NURM committee was “dead,” along with ten of the eleven others in county Durham.Footnote 48 The ongoing turmoil in the coal industry offered more possibilities for militant agitation. By November 1923, Harvey—who had been contributing articles to the new CPGB paper, the Communist from October 1921—was deploying his considerable experience in helping form a new communist industrial initiative; the (National) Minority Movement (NMM), which was formally launched in August 1924.Footnote 49

Harvey's industrial activity raised his standing inside the DMA. Continuing close collaboration with Communists may even, in these strange times, have further bolstered Harvey's profile. But Keir Hardie's relevance for Harvey's politics also reasserted itself in the immediate postwar years, as Harvey became active in the Labour Party. Elected a party branch chairman in 1919, Harvey won a seat for Labour in the year that the party took control of Durham County Council (making it the first such Labour-controlled institution anywhere in the country). Harvey soon joined the council's Education Committee, and in October 1919, Durham miners elected him among the union's parliamentary candidates.Footnote 50

The final portrait on the Follonsby banner is that of national miners’ federation (MFGB) general secretary Arthur James Cook (1883–1931).Footnote 51 Somerset-born, an eighteen-year-old Cook migrated for work to the booming South Wales coalfield. He emerged as a militant during the bitter Cambrian Combine strike in 1910, went to Central Labour College in 1911 (like Lawther), and was involved with Ablett in the miners’ “Unofficial Reform Committee” that published the Miners’ Next Step in January 1912. The antiwar Cook was imprisoned for sedition in 1918, briefly a member of the nascent CPGB in 1920, and was elected South Wales Miners’ Federation secretary in 1921. An ILP member, Cook, like Harvey, also worked closely with the Minority Movement until the late 1920s. Cook's election as MFGB general secretary, in February 1924, signified the miners’ increasing militancy in the teeth of short-time and downward pressures on their wages. Cook's legend took shape during the 1926 miners’ lockout.Footnote 52 The same was true at a local level for Harvey who was intensely active during 1926 organizing gangs to work Follonsby colliery's spoil heaps to provide house coal for locked-out miners. So successful was this operation that miners’ organizers came from all over the country to see how Harvey's system worked.Footnote 53

The Follonsby banner's life, re-birth, purgatory, and afterlife

For the decade from the unfurling of the first red Follonsby banner, appropriately enough by a wind-blown A.J. Cook, Harvey's political activism remained consistently that of a union militant and Labour left-winger, with strong links to local communists. Inside Follonsby lodge, Harvey continued to prove himself a highly capable official and organizer, especially in terms of winning compensation cases. In hard times of slack trade and shorter hours Harvey established a rota system to distribute available work as widely as possible.Footnote 54 Inside the DMA, Harvey was narrowly defeated in a vote for a fulltime DMA official in 1936 to another, younger left-winger, Sam Watson.Footnote 55 Harvey continued his Labour Party work, becoming chairperson of the local urban district council in 1933, before standing down in 1937.Footnote 56 Remaining on the Labour Left, Harvey worked with communists who had moved from the sectarianism of the “Class Against Class” “Third period” (1928–1933) to advocating, first, a united front with the rest of the Left, and, later a more politically heterogenous popular front.Footnote 57 Much of Harvey's work in this area was with the 1930s Hunger Marches to London and in solidarity support for the Spanish Republic after the civil war broke out in July 1936.Footnote 58

Figure 1 and 2. The 1928 red banner (left). The 1938 red banner with Horner on the microphone and Harvey standing next to him (right). Joyce, who appeared on a later version (see below) is immediately in front of the star. Tom Smith, who is also on the later banner, is front center (dark hair). PHOTOS: Dave Douglass.

The 1928 red Follonsby banner, bearing “portraits of five leaders revered by them all,” only survived a decade.Footnote 59 In January 1938, it was burned in a serious fire that had started in the upper story of Follonsby miners’ hall. The fifty-year old, largely timber-constructed building, and Harvey's adjoining house, were both razed. Woken by their two barking dogs, Harvey and his wife escaped “just in time.”Footnote 60 The banner, all lodge documents, and Harvey's collections of antiques and first editions of Robbie Burns, James Hogg, and Sir Walter Scott that he had built up over twenty-five years were all destroyed.Footnote 61

Yet, only six months later, a “replacement” red Follonsby banner was unfurled. Costing £60 (around $5,000 today), it was more professional than its predecessor. The portrait of Lenin was painted by a “famous Russian artist” and sent from Moscow, to be returned after it had been copied onto the banner. The Connolly portrait was commissioned from a Dublin Academy artist who had fought alongside him in 1916. The new Follonsby banner had the same five portraits as its 1928 predecessor and carried similar images of the hammer and sickle and the Soviet six-pointed star.Footnote 62 The main difference, apart from superior portraiture, was that Harvey and Cook (now cleanshaven) had switched places with Harvey, now positioned bottom left. It is uncertain if these, and other changes (see photos), were for other than stylistic reasons. The new banner, in the Soviet national colors of red, gold, and white, was unfurled at an open-air meeting at Wardley welfare ground on Sunday July 17, 1938.Footnote 63 Arthur Horner (1894–1968), the main speaker, was an apt choice. Elected president of the South Wales miners in 1936, Horner, like Harvey, joined the ILP in his youth, became a Marxist under the influence of Noah Ablett and, opposing the war, joined the Irish Citizen Army. He was a CPGB founder member and NMM activist, although, unlike Harvey, Horner remained a fully committed CPGB activist throughout his career.Footnote 64

Figure 3. The reverse of the 2011 reproduction banner PHOTO: Lewis Mates.

On the banner's reverse side was a female figure carrying a flaming torch and wearing four sashes emblazoned with the words “Progress, Education, Art, Science.” Even with the new socialist influenced trade union iconography of the twentieth century, women workers were rarely depicted in masculine-dominated industries like coalmining (even less so in Durham where women had never worked underground). But they did remain as representations of liberal self-help (for example, as Prudence, Truth, or Justice), continuing from an earlier period. The Follonsby banner's female figure comes more from the direct influence of socialism, however, in representing either an angel (with wings obscured) or perhaps a goddess. She wears a red Phrygian or “liberty” cap, worn during the French Revolution to demonstrate allegiance to the republican cause. This, too, was typical of the iconography of the newly emerging Socialist movement that was partly inspired by French Revolutionary imagery, and whose most famous proponents were Williams Morris, Walter Crane, the progressive arts-and-crafts movement and art nouveau.Footnote 65 Indeed, the Follonsby image bears striking similarities to a (clearly winged) angel of socialism in a Walter Crane image for the ILP's paper Labour Leader in 1897.Footnote 66 To the angel's left there is a small coal mining headgear in silhouette and half obscured with the word “oppression” above it. The angel's torch lights the way for a group of four miners, a woman, and a child. They are all looking onto new (interwar) style housing. In front of the new, spacious-looking houses is a green or park packed with people of all ages enjoying the outdoor space, including children at play. Below this image are the words “The World for the Workers.”

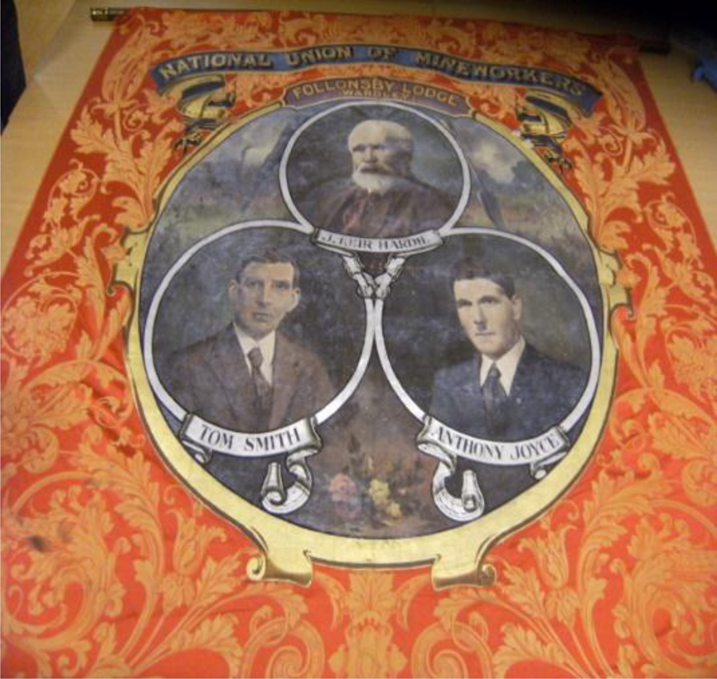

Figure 4. The painted over red banner, now located in Beamish Museum. PHOTO: Dave Douglass.

The scene is reminiscent of what a new part of Wardley had begun to look like, ironically, just as Follonsby colliery closed down, on midnight of October 15, 1938, as (its owners claimed) it was uneconomic. The resultant twelve hundred job losses constituted almost the entire village's male working population.Footnote 67 The new red Follonsby banner had served a lodge with a functioning colliery for only three months. By January 1939, Harvey had moved onto Harraton colliery after twenty-five years leading the Follonsby miners. Harraton was another lodge with a militant reputation five miles south of Wardley.Footnote 68 Follonsby lodge struggled on, albeit with an (unemployed) membership that had halved by April 1939. Salvation was at hand, however, as rumors that new owners were going to re-open Follonsby (along with the old Wardley colliery that had been closed since 1913) were officially confirmed in June 1939.Footnote 69

But what of Harvey's red banner, left behind in Wardley and now under the stewardship of the new, more moderate lodge secretary, Anthony Joyce? The portrait side (the front) was painted over, while the reverse, less controversial, side remained unaltered. Of the red banner's five portraits, only Hardie survived on the painted-over version, now located directly above portraits of Joyce to his left and Tom Smith, the lodge treasurer.Footnote 70 The Soviet symbols, and the Morris quote, were now also gone. Painting over was not unusual (see below): it was much cheaper than commissioning an entirely new banner, and easier to do. Painting over also made a political statement, in this case about those who ran the lodge now that Harvey had gone. In terms of the portraits of the new lodge officials, Harvey's own image appeared on the 1928 and 1938 versions of the red banner. Indeed, Durham lodges often pictured local officials on their banners, often alongside regional, national, and international figures.

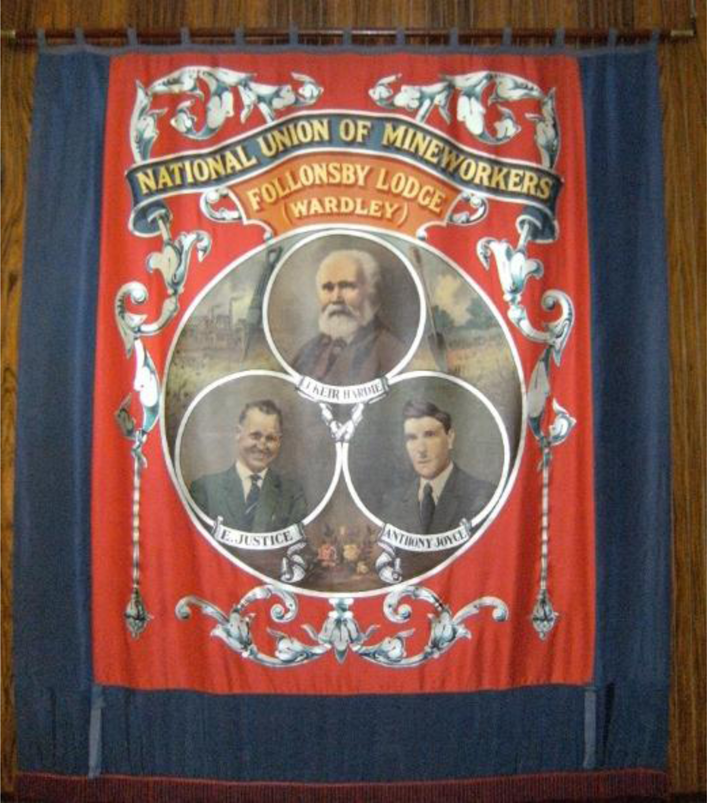

Figure 5. The last (1960) Joyce banner, now located in Gateshead Council Chamber. PHOTO: Dave Douglass.

Precisely when the red banner was painted over remains uncertain, but it must have happened before Harvey died in July 1949. The shock that Harvey felt at seeing what had happened to his red banner was not unique: other Follonsby miners refused for many years to carry the “Joyce” banner at the annual gala, in protest at the red banner's desecration.Footnote 71 Around 1960, a new—albeit inferior quality—lodge banner was unfurled carrying the same design as the painted-over “Joyce” version it replaced (see below).Footnote 72 The painted-over red banner was discarded and, bizarrely, ended up being rescued by a holidaying Mr. Anderson from a rubbish tip in Marlow, Buckinghamshire, in south east England, sometime in the 1960s.Footnote 73 Feeling “guilty” during the 1984 miners’ strike, Anderson donated the banner to Beamish Open Air Museum in County Durham.Footnote 74 Somehow the tattered remnants of Harvey's old 1938 red banner had found their way back to his birthplace some thirty-five years after his death.

In June 2011, an expertly crafted reproduction of the 1938 red Follonsby banner was unfurled at a packed ceremony in Wardley club. The 1938 red banner's afterlife had begun. This came in the context of the remarkable renaissance of the annual Durham Miner's Gala, a demonstration of the strength and solidarity of the miners and the wider labor movement that had been held annually, almost unbroken since 1871, but which looked likely to expire with the closure of the last Durham collieries in the early 1990s.Footnote 75 For some years before 2011, however, local miners’ banner groups had been springing up all over the county, using the miners’ “unique heritage, grounded in solidaristic and inclusive social networks” to return “meaning back to their lives.”Footnote 76

The origins of the 2011 red banner's rebirth lay in the 1960s and Dave Douglass, a third generation Wardley miner, who, after training, started down his village's pit in 1964, aged seventeen. It was here that Douglass first heard talk of Harvey, this “folk hero in the community.”Footnote 77 A faction of the “old boys,” including his own father, were “Harvey's men”; educated by Harvey at lessons on Sunday afternoons. But one manifestation of the rich auto-didact culture of the coalfield, this was also a standard way that miners’ leaders built a local support base. As his own politics developed from youthful communism to anarchist syndicalism, Douglass’ “ears pricked up” at any talk of Harvey. Indeed, discussing issues like the police or war in the pit, some of the older men told the young militant that he talked politics like the long-gone Harvey.Footnote 78

In 1970, like Harvey before him, Douglass went to study at Ruskin College, where Raphael Samuel encouraged him to research the history of the Durham coalfield. On returning to Tyneside for research, Douglass saw the history of his home village with new eyes. He then “discovered” a photo of the 1938 red banner's unveiling, pinned to the wall of a wooden hut where retired Wardley miners congregated. This photo, it later transpired, was a copy of one that appeared in the North Mail (July 18, 1938). Copies of it must have been distributed to the Follonsby lodge committee at the time. Tapping into the rich local oral history, Douglass found that Harvey was still known of as a “hotheed” at the Durham miners’ offices in Redhills. Once completed, Douglass presented his findings to the “History Workshop,” riotous research seminars with “hundreds hanging off the ceiling listening,” that brought something of the spirit of a contemporary rock festival to the study of working-class and radical “history from below.”Footnote 79

In 1972, Douglass’ Pit Life in County Durham, the sixth number in the History Workshop Pamphlet series, contained an afterword devoted to Harvey. (Douglass had wanted the 1938 red banner photo to go on Pit Life's cover).Footnote 80 And, with History Workshop events so well attended, energy-driven, and inspiring, soon other researchers like W.R. Garside and Ray Challinor, and later Ruskin student Geoff Walker, were also chasing up Harvey (whose only previous appearance in academic print had James Williams mistakenly placing him in the Derbyshire coalfield).Footnote 81 Also in 1974, Harvey's own theoretical work was brought to a new generation of militants. The Institute for Workers’ Control published an extract from Harvey's 1911 pamphlet Industrial Unions and the Mining Industry.Footnote 82 Douglass had previously presented to the IWC on Harvey, though was disappointed to find that its meetings lacked the “sex, drugs and rock-n-roll” of History Workshop.Footnote 83

Alongside this recrudescence in academic interest in questions of worker's power, that fed from, and into, the growing industrial militancy of the early 1970s, there was pioneering work on trade union banners. The initial spark was also the rich banner culture of the Durham coalfield when, in early 1973, the Durham Light Infantry Museum hosted an exhibition of local lodge banners. W.A. Moyes, a local headmaster, produced an accompanying book. Moyes followed this up a year later with a full-length study of Durham miner's banners, published by Frank Graham, a Newcastle-based publisher who had fought in the International Brigades during the civil war.Footnote 84 But it was John Gorman's 1973 Banner Bright that first published the second of only two known photographs of the 1938 red Follonsby banner. This image, of the full banner hanging on a loom, includes the Morris quote that is obscured in the North Mail's 1938 unveiling photo. Gorman had accessed the archives of Tutill's, the famous London banner makers who had cornered the interwar British trade union banner market. Fortunately, the photo's glass negative had escaped the 1940 Nazi bombing of Tutill's.Footnote 85

Douglass published more on Harvey in the later 1970s, again under the direction of Samuel. But, as a union activist, Douglass's output turned much more to interventions on the political questions of the day, particularly around the 1984/85 miners’ strike, in which he played a leading part in the South Yorkshire coalfield.Footnote 86 By 2009, returned to his native northeast and retired, Douglass could pursue his long-standing aim to bring the 1938 red Follonsby banner back to life. In close cooperation with the DMA, Douglass formed a Follonsby Banner Association (hereafter the Association) of interested locals, activists, and members of Tyneside IWW. There was considerable enthusiasm from several local Gateshead councilors who pooled their annual allocations from the council community fund, itself then under serious threat from the Conservative/ LibDem. coalition government's austerity agenda, to fund the new banner.

Funding secured, there came the task of ascertaining the 1938 banner's coloring and what was on the back of it. Both existent (known) photos were black-and-white and of the front only. The breakthrough came when Douglass was tipped off that the painted-over Joyce banner was in storage and uncatalogued at Beamish Museum. Finding the original 1938 banner—albeit it painted over—gave Douglass a “terrific sense of historic connection.”Footnote 87 On the front, the original image was starting to come through the paint, as if the red banner was reasserting itself after decades of obscurity. Douglass and the Beamish archivists concluded that the painting-over was part of the banner's historical identity and therefore no attempt should be made to remove it. The image on the back, however, seemed to have been untouched, which allowed for an exact copy for the 2011 replica banner (see above images).

With the requisite funding secured, the Association then conducted a “beauty parade” of banner makers, settling on Chippenhams Designs. As if to anticipate the renaissance in interest in banners, Chippenhams had been founded in 1969, with a London premises in the next street to the site of the famous Grunwick strikes and protests of 1976–1978.Footnote 88 By the time the replica Follonsby red banner was commissioned, Chippenhams had a strong reputation, having been on the TUC's list of approved banner makers since the 1980s, and now widely regarded as the heirs to Tutill's.Footnote 89 As to the banner material, the last looms large enough to recreate the original jacquard weave in Britain had been destroyed during Second World War bombing. The remaining silks in Britain had been snapped up as union banners made a resurgence. By 2011, a jacquard weave could only be secured from India. The Association decided instead to commission a British-based weaver to make the weave in six pieces, which were then stitched together to appear as one single silk. The new red Follonsby banner, costing £13,600 in total, made its first Durham Miners’ Gala appearance among some eighty banners and forty bands on July 9, 2011, over seventy years since the original was last paraded on gala day. The Association has carried the Follonsby banner at every gala since.Footnote 90

Acting on instructions from the council funders, Association members took the banner to a traditional blessing ceremony in Durham cathedral during the 2011 gala. The incongruity of this material statement of interwar revolutionary internationalism being blessed by Justin Welby, the then Bishop of Durham, was not lost on the Association's members nor, it seems, on the clergy. Dave Douglass remembered: “The cathedral nearly fell down when we went in with Lenin and James Connolly. The bishop did remark it was rather radical.”Footnote 91 That the blessing went ahead at all was suggestive of the far more cordial relationship that the Church of England enjoyed with the former mining areas of Durham in the twenty-first century than it did in the period when the Follonsby banner was born. Vocal opposition to miners’ demands for a living wage by the interwar Bishop of Durham, Hensley Henson, unsurprisingly rendered him singularly unpopular. Mistaken for Henson, the Dean of Durham was manhandled into the river Wear while making an ill-advised appearance at the Durham Miners’ Gala in July 1925.Footnote 92

How “revolutionary” was the Follonsby red banner?

The 1928 Follonsby red banner was certainly an outlier in terms of (some of) the figures it celebrated, and it remains so in the context of Durham miners’ banners specifically, and British miners’ and other trade unions’ banners more generally. Indeed, in 1973, John Gorman dubbed the Follonsby banner “implicitly, what must be the most revolutionary banner yet unfurled by a union,” a claim he repeated in 1986.Footnote 93 This section teases out some of the theoretical and contextual complexities and assumptions of this, or any, claim about how “revolutionary” any trade union banner is.

We might start with Lenin, the central banner portrait, and note that the regime his democratic centralist vanguardism inaugurated in Russia after 1917 appeared to its Left critics as the hijacking and side-tracking of a nascent revolution—manifest in the popular, democratic councils called Soviets—rather than its logical consolidation. The Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin effectively predicted—by thinking through the logic of Marx's ideas applied—what would happen in Russia a full forty years before it came to pass. This does not, of course, mean that Bakunin's own writings, such as his Pan Slavism, anti-German and anti-Semitic sentiments, and political practice (conspiratorial secret societies) were beyond criticism.Footnote 94 But, while visiting and sympathetic anarchists were leaving nascent Bolshevik Russia with their worst fears of rampant authoritarianism confirmed, the Russian revolution had, at the time, offered a spark of hope to progressives of varied political hues in a war-torn world.Footnote 95 It was therefore unsurprising that, when anarchist eyewitness Emma Goldman came to Britain to tell the working-class movement what was really happening in Bolshevik Russia in the early 1920s, she was side-lined and ignored.Footnote 96

Lenin also appeared on the other two red banners of the interwar Durham coalfield, those of Chopwell and Bewicke Main, both unfurled four years before the red Follonsby banner, and within a few months of Lenin's death on January 21, 1924. Chopwell was Will Lawther's stomping ground. Organizing numerous and diverse propaganda and educational activities through the village's Anarchist (or Communist) club (from 1913), Lawther, his numerous and equally militant siblings and a group of like-minded activists came to dominate the lodge's interwar politics.Footnote 97 Chopwell lodge's new red 1924 banner exemplified this. It also carried two other portraits; those of Marx and Keir Hardie.Footnote 98 The Chopwell reds were still not locally hegemonic, however. There was overt opposition to the new banner, although this may have been due to its perceived endorsement of (communist) atheism, or because, only a few years after the Great War, that Marx was German.Footnote 99 Chopwell had suffered fearfully in the war, in spite of a small but militant antiwar, anticonscription movement led by Lawther and his comrades. Nevertheless, the Chopwell red banner, and the names of new streets of housing built from 1924, fed into the “Little Moscow” epithet that Chopwell had fully adopted by the time the red Follonsby banner emerged. And, while Wardley also had something a claim to the Little Moscow epithet, there is scant evidence that this embedded itself in local popular myth.Footnote 100

Regarding timing, then, Follonsby did not blaze the trail for red banners in Durham. Indeed, 1928 was a curious time to launch a red banner; the CPGB was just embarking on its sectarian “Class Against Class” phase that would only seem to exacerbate a pre-existing drift from a widespread militant mood in the coalfield to apathy that came in the wake of the miners’ return to work in winter 1926. This was exemplified by the regional CPGB's (mostly miner) membership decline by two-thirds in a year after September 1926.Footnote 101 It is only, however, on Follonsby's banner that Lenin's image is central, and by far the largest of the five figures. This must suggest Lenin's front-ranking standing among the Follonsby banner's miner designers at the very least.

On Bewicke Main, the distinctly unrevolutionary first Labour prime minister and MP for the Durham mining seat of Seaham (until 1935), Ramsay Macdonald, was the central and largest banner portrait. Concerned at the potential existential threat that syndicalist arguments posed his party before the Great War, Macdonald expended a good deal of energy attempting to refute them.Footnote 102 He had, on the other hand, subsequently adopted a principled antiwar stance and suffered as a consequence. Macdonald was, however, painted over (startlingly with white paint rather than another portrait) in retribution for his “betrayal” of the labor movement in forming the National government with Conservatives and Liberals in 1931. Painting over portraits on banners was standard practice. A pre-1924 version of the Chopwell banner saw a local leader's image painted over when he became a masterweighman (i.e., the owners’ checkweighman!).Footnote 103 Of these cases, however, it was only the painting-over of the Follonsby banner that moved it toward (rather than away from) political or industrial moderation. But, with Bewicke Main colliery shutting permanently in 1934, only the red Chopwell banner survived the immediate postwar years to represent a working Durham colliery. Its third incarnation in 1955 was finally retired and replaced by a fourth in 2011, the same year that the red 1938 Follonsby banner was also brought back to life.Footnote 104

By 1928, the Soviets also basked in the proud record of their considerable donations to the locked-out miners of 1926. If anything, Lenin's standing was higher among miners then, than just after he had died in 1924. In the context of 1920s Britain, Lenin was unequivocally a revolutionary figure for the overwhelming majority of those seeking progressive social change and it is perhaps not so surprising that his portrait unites the three red Durham miners’ banners. There is an argument here that, with Marx as its central portrait, the red Chopwell banner was more revolutionary. This is determined not simply by a judgement over whether revolutionary ideas trump revolutionary actions (though the notion of Marx's as simply a legacy of ideas has been problematized), but also of the relationship between the ideas of Marx (and Engels) and Lenin.Footnote 105 On the one hand, there is a more libertarian form of Marxism evident, for example, in Rosa Luxemburg's critique of Leninist vanguardism.Footnote 106 Likewise, there is John Plamenatz's later claim that Lenin was not a Marx scholar and that he only knew slogans and broad conclusions, being ignorant, even, that he was distorting Marx's work.Footnote 107 This position regards the notion of Marxism-Leninism as incongruent, thereby allowing Marx to retain his revolutionary (and, indeed, democratic) credentials while Leninism and its practitioners, including Stalin, are condemned as ill-read autocrats or worse.

A broadly drawn counter-position contends, like Neil Harding, that Lenin was not a Russian-Jacobin opportunist but rather a serious, consistent, and even doctrinaire Marxist. Here is a defense of Leninism, including vanguardism and democratic centralism, and an argument that the disconnect in the Marxist tradition comes with Stalinism, which cannot be regarded as a natural development of what had come before.Footnote 108 Adopting the first position renders Marx (much) more purely revolutionary than Lenin. The second position renders Marx and Lenin equals in this regard, though it is worth remembering that many of the leading Chopwell reds were as prepared to openly support Stalin's regime as they had been Lenin's. And this remained the case even after the 1956 Khrushchev revelations about Stalin's murderousness that precipitated a mass exodus from the CPGB.Footnote 109 The third, anarchist position (discussed above), does of course also see congruence and continuity between the writings and practice of Marx and Lenin, but regards this as essentially authoritarian rather than liberatory.

At the time it seems that Marx's legacy was as likely to be understood as one of “action” rather than ideas. In June 1925, a local left-wing Labour councilor said that the “Marx Terrace” of new housing in Chopwell was named after “one of the greatest and noblest of trades union leaders that ever lived.” When asked Marx's nationality (being German remained widely problematic in 1925) the councilor quipped; “According to the Bible he is one of our brothers (Laughter).”Footnote 110 Indeed, that Chopwell had two non-British/ Irish revolutionary figures (though Marx had spent a lot of time in the country), and that one of them was of a recent enemy, nationality offers an argument for it being the most revolutionary banner; its two revolutionaries’ impact being qualified (to a debatable degree) by one single mainstream Labour leader (Hardie). Hardie's portrait was, admittedly, central on the Chopwell banner, but all three portraits on it are the same size, distinguishing it from Follonsby's significantly larger, and centrally located Lenin.

Not all the other figures (smaller on Follonsby's banner) were as controversial or “contextually revolutionary.” That Keir Hardie alone remained on the painted-over Joyce Follonsby banner was testament to his status as perhaps the only figure by 1950 who transcended the often chasmic ideological diversity in the British labor movement. Indeed, Hardie's politics defied reductive categorization, as Stefan Berger remarked about Duncan Tanner's efforts at doing so.Footnote 111 More recently, that Labour leaders as ideologically diverse as Tony Blair and Jeremy Corbyn could both lay claim to following in the tradition of Hardie suggests that he continues to hold this unusual status in Labour mythology more than a century after his death. (Clem Attlee has since become another Labour figure among very few able to bridge modern ideological divides within the Labour Party in this way. Naturally, Attlee could not do this while he still lived.)

But care is needed in classifying the meaning of activism within Hardie's party, the ILP, before 1914. Certainly, it was much more complex than a vehicle for a form of classless, ethical socialism, or the even less ideological laborism, contrary to Tanner's still influential account of the period.Footnote 112 While the ILP's political project remained statist and essentially reformist—nationalization of the coal industry rather than the syndicalist “workers’ control”—it was still able to engage meaningfully with syndicalist ideas of all hues. The reasons grassroots ILP activists gave for rejecting syndicalist ideas were often not about ends but means. The ILP's approach was regarded as simply better tailored to securing reforms and small, short-term victories.Footnote 113 That syndicalism was regarded as a longer-term strategy that could not adequately address miners’ immediate precarious material conditions inverted Noah Ablett's pro-syndicalist rhetorical question “Why cross the river to fill the pail?”Footnote 114 Taken as a whole, though, all of this suggests a rather blurred line between the revolutionary and the reformist as it was understood and experienced at a grassroots level in organizations like the ILP. This point is evident, too, in the very combination of figures—in some respects diverse, in others rather less so—on the Follonsby banner itself.

A case study of Cook's political history also reveals the complexities of defining “revolutionary.” Elected on the Communist-inspired Minority Movement platform in 1924, even during the 1926 lockout, there were moments—such as July 1926, when he recommended acceptance of the bishops’ compromise proposals to end the lockout—that belied even his reputation as a militant. After the lockout, though, Cook was heavily involved in the Communist-led unemployed hunger marches and, in 1928, he launched a campaign with the ILP firebrand Jimmy Maxton to end the capitalist collaborationism of the Mond-Turner talks between industrialists and union leaders. But even Cook's own union, the miners, had accepted this new stance and he was forced by circumstance toward an overtly pro-Labour position, incurring the wrath of a sectarianizing CPGB.Footnote 115 Though of a younger generation and leading on the industrial wing of the labor movement, Cook was nevertheless a similar figure to Hardie; charismatic; a great speaker; difficult to pin down ideologically; and somewhat tragic. Thus, while it would not be helpful to blithely brand Cook a revolutionary, he remained, like Hardie, a popular choice for Durham miners’ banners.

Harvey himself can be characterized similarly to Cook; albeit, with a head that “continually wagged from side to side,” he lacked Cook's oratorical impact.Footnote 116 Though a Labour councilor from the early 1920s, Harvey was and remained an industrial militant on the party's Left and was sympathetic to communist initiatives of all kinds (though there is no firm evidence that he was ever a card-carrying party member, unlike some similar figures in the region).Footnote 117 Harvey's acceptance of parliamentarianism did not represent a significant adaptation of his politics as the SLP's dual strategy always advocated running election candidates on a revolutionary ticket. In practice, however, Harvey stood on the reformist municipal tickets of the Labour Party and his local standing and influence within the party grew throughout the interwar years. Harvey was thus able to occupy political space, in a time of considerable flux, that allowed for activism within the Labour Party as well as other organizations outside of it that themselves had fluctuating relationships with the then nascent CPGB (itself yet to fully coalesce around a firm organization and strategy). Initially, at least, communists were instructed to become active in the Labour Party, with the idea that if it failed, the CPGB could capitalize on the discontented, radicalized workers, a strategy Lenin infamously branded as supporting Labour leaders (specifically Arthur Henderson) “in the same way as the rope supports a hanged man.”Footnote 118 In working through pre-existing labor movement structures (and therefore palpably not subject to Lenin's diagnosis of “infantile disorders”) Harvey acted as a good Leninist should in Britain, certainly in the early 1920s.

In the 1930s, Harvey's support of all the major causes of the Labour Left and CPGB included even the popular front, which meant antifascist work with liberals and even, in some versions, progressive conservatives.Footnote 119 That said, Harvey's call for direct action in a “working class Popular Front” against the government, in October 1936, for example, was open to a degree of interpretation.Footnote 120 Was this a militant, class-conscious alliance Harvey desired, or an “alliance at any price” sell-out with capitalists now being denounced by the newly (self-styled) revolutionary ILP? In terms of his politics, Harvey self-described (and was known in Wardley) as a Bolshevik rather than a Communist.Footnote 121 This may have been a way of suggesting that Harvey regarded himself as a revolutionary in the model of Lenin's party, and the CPGB as not so. But the precise meaning Harvey intended to convey by this distinction has been lost. He did not use the word revolutionary itself at all in his public utterances. It does, however, seem likely that Harvey regarded himself as politically consistent and that, with a change of contexts he, as any effective political operator, simply tailored his mode of activism and language to suit the prevailing mood of the times. This notwithstanding, practically Harvey dedicated most of his political life to strengthening (as well as, to some extent, radicalizing) the institutions of both industrial and political wings of the mainstream labor movement.

Furthermore, Harvey was by no means alone among Durham miners with this complex political identity, one so graphically depicted on the Follonsby banner. Prewar anarchist and vehement antiparliamentarian Will Lawther, for example, similarly became a Labour election candidate by 1918 and an MP (briefly) by 1929. Lawther's later trajectory, that ended with his term as a right-wing postwar president of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), did however differentiate him considerably from Harvey. But the rest of the militant Lawther family of Chopwell, and their comrades like Henry Bolton, operated politically in much the same way as Harvey throughout this period, notwithstanding Labour's nationally-led intensifying efforts to define itself against Communism and to root out Communists among its ranks from 1925 onward.Footnote 122

The Follonsby banner's image of James Connolly, albeit not placed centrally, is ordinarily crucial in any case for the uniqueness of its revolutionary credentials. More than this, it is that Connolly is depicted wearing the uniform of the Irish Citizen's Army, which he wore fighting in the streets of Dublin in 1916, for an organization that was to become the IRA. While a handful of Irish banners depict Connolly, none dress him in this uniform.Footnote 123 These details seem to have been lost on the press at the time of the banner's unveiling. Indeed, it is noteworthy that, of the five banner portraits, the North Mail judged it necessary to remind its readers (albeit briefly) only who Connolly (“the famous Irish leader”) was.Footnote 124

Alongside Lenin, Conolly is a second “man of action” (and it is exclusively men who are depicted). Though a prolific writer of Marxist propaganda, Connolly is not generally recognized as a front-ranking Marxist thinker. Connolly's revolutionary credentials are tied up intimately in the debates about the extent to which his involvement in the Easter rising represented an act drawing from his Marxism, or that his aligning with bourgeois nationalists represented a repudiation of Marx. Claims regarding how revolutionary the Follonsby banner is, then, are to a considerable extent determined by positions on the “Connolly question.” Dave Douglass, for example, argued that Connolly saw the Irish 1916 rising as a means of setting off a series of anti-imperialist, antiwar conflicts across Europe. This is effectively an endorsement of the early orthodoxy established by C. Desmond Greaves (1961) that Connolly was akin to Lenin.Footnote 125 Austen Morgan offered a qualification, arguing that Connolly's involvement in the Irish Revolution stamped a strong nationalist identity on Irish working-class politics.Footnote 126 But it is David Howell's subtle approach—defending Connolly from claims of Marxist apostasy, but more critical of Connolly's mythologizing of the Irish past and disregarding of the nonsocialist politics of many of the Nationalists he worked with—that most convinces.Footnote 127

There is a further dimension to this understanding of revolutionary being as much (if not more) about action than thought, about means rather than ends. This is evident in Douglass's claim that the Follonsby banner was probably the most revolutionary since the days of the Chartists, justified by pointing to Chartist banners’ sometimes violent slogans and images.Footnote 128 Certainly, Chartists’ banners (none of which still exist) representing the “physical force” side of the movement implied violence in some of their images (like guns and knives) and slogans (such as, and taken from the Bible, ‘“He that hath no sword let him sell his garment and buy one”’).Footnote 129 Of course, this does beg the question of how revolutionary (and, indeed, contradictory) it is to demand the vote by threatening the use of violence. Perhaps this is as incongruous as the SLP's dual strategy of standing for parliamentary elections on a revolutionary platform.

Apart from the portraits, there were also the words and symbols the red banners carried. Follonsby had the Red Star, the Rising Sun, and the Hammer and Sickle, all of which were in prominent positions. Chopwell's, by contrast, carried two symbols: the Hammer and Sickle inside the Red Star (located below Lenin's portrait) and the Labour Party's symbol (located below Marx).Footnote 130 In terms of the poems, surely Follonsby's William Morris lines were more revolutionary (albeit perhaps less uplifting) than Chopwell's Walt Whitman quote (suggested by Will Lawther's brother Eddie) “We take up the task eternal, the burden and the lesson. Pioneers! O pioneers!”Footnote 131 But both banners’ “wordy expressions” were “exceptional.”Footnote 132

There is one final consideration regarding the nature and meaning of the Follonsby banner's iconography. All the discussion above is about the five men depicted on the front of the banner. The whole reverse side of it is like the other known Durham miners’ banners produced in this period, including Chopwell's. This was partly due to 1920s banner fashion and was reflected on trade union banners from various industries and all over the country, thanks to Tutill's central role in banner design and production.Footnote 133 But it clearly offers a social democratic vision of an attainable future. And the Follonsby version also, notably, has a better gender balance than the similar but male dominated Chopwell banner scene.

Even though this was a generic union banner image, Wardley village had begun, in part thanks to Harvey's council work, to resemble it before the war. This new semi-detached housing was, perhaps ironically, being occupied, and the old colliery slum housing deserted and readied for demolition, just as the colliery itself was being mothballed (albeit momentarily) in late 1938. Post-1945, there came more such council housing in Wardley, including the Ellen Wilkinson estate in the early 1950s. The banner scene, then, does not at first glance appear revolutionary but rather reformist. Yet, for lifelong miners and activists like Dave Douglass's coal miner father—a new occupant of the Ellen Wilkinson estate after living in much older housing—here was real socialism. There had apparently, through the ballot box, been a peaceful revolution, evident in real material gains like indoor toilets, the elimination of the hitherto ubiquitous “black clocks” (cockroaches), and generously sized gardens for, eventually, every working-class household. Naturally, these gains were nowhere near enough for the radicals of Douglass's own baby-boomer generation, nor for New Left critics of parliamentary socialism.Footnote 134 Yet both generations were to discover that the apparent gains (revolutionary or hopelessly reformist, as they might have been) of the early postwar years could be reversed after the 1979 Thatcher victory.Footnote 135

Conclusion

Any judgement on the degree to which a trade union banner is revolutionary must be based on a contextually specific yardstick that adopts and defends a position on the various issues discussed above. These include ruling on the relative importance and relationship (or not) between means and ends, thought and action, and changes in the contexts and political outlooks of complex individual activists over time; even their often-apparent contradictory nature at any given moment, as well as how these activists are understood by those around them. This is certainly not to dismiss revolutionary as an historical category. It is, rather, to recognize that the term, like all those used in the study of politics, needs defining in a clear, historically specific way.Footnote 136 Yet the red Follonsby banner's explicable but contestable status as the most revolutionary British trade union banner is less important than the light examining this claim can throw on the complexities of both the local-specific and the much broader political cultures that shaped it.

Taking the local first, it is clear looking at Follonsby, and its two fellow red Durham banners, that adorning them with the image of the leading international Communist of the interwar period did not indicate the even very local-specific embeddedness of organized Communism (in the form of a strong and influential CPGB branch). Indeed, it is remarkable that the militant (traditionally regarded) South Wales coalfield, with its actual Little Moscows like Maerdy and Bedlinog (where the CPGB was locally hegemonic for a time in the interwar period) did not spawn red banners.Footnote 137 In the (traditionally regarded) moderate Durham coalfield, conversely, the CPGB was never hegemonic in any locality, not even in the coalfield's own Little Moscow of Chopwell.Footnote 138 This moderate Durham coalfield was politically dominated by the notorious postwar right-winger Sam Watson. But even he, as we have seen, had been on the prewar Left, just like his political ally Will Lawther, who, as NUM president, became the “hammer” of the Bevanites in the 1950s. Thus, while the red Durham banners’ very existence does not mean that the Durham coalfield should be regarded as on a par with its radical South Walian counterpart, they are testimony to the complexity and diversity of the political culture of coal mining areas, none of which, on closer scrutiny, lend themselves to reductive caricature.

As demonstrated above, not only do these red banners reflect the evolving politics of local leaders and their idiosyncratic political vicissitudes, they also testify to the complexities of the much broader, and changing, political ideologies, identities, and institutions of the British labor movement. In terms of the diversity and nuances of its iconography, and in exploring the spatial and ideological specifics of this, the overlaps and subtleties of working-class organizations and the activists who give them life, the Follonsby red banner seems rather more representative of the British Left in an interwar moment than it might at first be given credit for. Even in its apparent exceptionality, it tells us about much more than itself. Not only this but its postwar afterlife—painted over for the late 1940s and affluent, conservative-dominated 1950s—its rediscovery as an image by a young activist in the early, militant 1970s; its return home prompted by the 1984/85 miners’ strike; its physical rediscovery and synthetic rebirth in 2011 as many other local banners were being revived or rediscovered, too; chimes with developments in the history of the British Left. All this suggests that the banner's significance lies rather more in its strange representativeness than in its apparent uniqueness. Naturally, the history of one single artifact cannot hope to reveal all the secrets of the historical development of a mass movement of many millions of people over a century of more. But the complexity it does reveal—of political cultures, of the relations between understandings of the past, the present, and the future—can still be observed, every second Saturday in July in the city of Durham at the miners’ gala; an event that the Follonsby Banner Association hopes to march at for many years to come.