No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

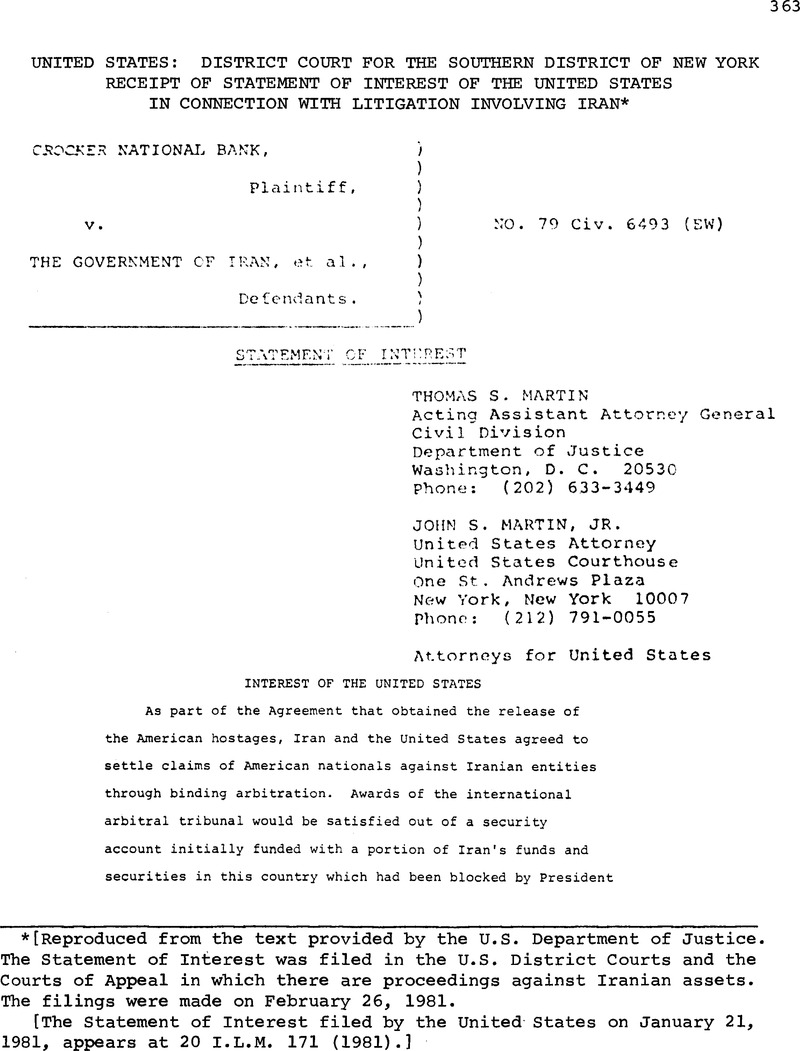

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. The Statement of Interest was filed in the U.S. District Courts and the Courts of Appeal in which there are proceedings against Iranian assets. The filings were made on February 26, 1981.

[The Statement of Interest filed by the United States on January 21, 1981, appears at 20 I.L.M. 171 (1981).]

*/ Executive Order No. 12,170, 44 Fed. Reg. 65729 (Nov. 15, 1979).[18 I.L.M. 1549 (1979)]

** The Agreement is principally comprised of two Declarations to which the United States and Iran adhered: (1) Declaration of the Government of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria [hereinafter Decl. I]; (2) Declaration of the Government of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria Concerning the Settlement of Claims By The Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran [hereinafter Decl. II]. See, Iranian Assets Litigation Rep. pp. 2224, 2227 (Jan. 22, 1981). Additional undertakings, an escrow agreement, and other technical banking documents were also part of the overall agreement, and have been made public, f 2 0 I.L.M. 224 (1983*)]

*/ There are presently pending in the United States nearly 400 suits against Iran, involving several billion dollars in claims.

**/ Certain categories of claimants are not eligible for relief before the Tribunal. See pp. 23-25 infra.fj. T.. M_ p. 374′

***/ Under the Agreement, the United States is not required i to-place any assets in a security account to fund Tribunal oawards ii: favor of Iranian claimants.

*/ Several claimants have obtained injunctions against the transfer of Iranian assets which are functionally equivalent to attachments, and for purpose of this document the term attachment is intended to incorporate those equivalent injunctions.

*/ Neither the Executive Orders nor implementing regulations, 31 C.F.R. 535.218(b), purport to terminate valid pre-judgment attachments acquired prior to November 14, 1979 against Iranian property.

* The Executive Order provides that if the Tribunal determines it does not have jurisdiction over a claim, the suspension of that claim terminates. If the Tribunal (1) rejects the claim on the merits or (2) provides that a claimant shall have a recovery, and the claimant is paid the full amount of the Tribunal award, then, either situation “shall operate as a final resolution and discharge of the claim for all purposes.” (Id. §§3, 4.) [i.L.M. p. 412]

The Executive Order further provides (1) that the suspension applies to all claims for equitable or judicial relief in connection with claims that may be presented to the Tribunal under Article II; (2) that the suspension applies to all claims either presently pending or filed after the date of the Executive Order; (3) that the commencement of an action for purposes of tolling a period of limitation is not precluded; (4) that nothing requires dismissal of any action for want of prosecution; (5) that nothing shall apply to any claim concerning the validity or payment of a standby letter of credit, performance or payment bond, or other similar instrument; (6) that nothing shall prohibit the assertion of a counterclaim or set-off by a United States national in any judicial proceeding pending or hereafter commenced by Iran or its entities; and (7) that Executive Order Nos. 12,276 through 12,285 are ratified. The Executive Order delegates all the powers granted the President bv IEEPA to the Secretary of Treasury. (Id. §§1, 2. 5, 6, 7, 8.).

*/ See also Richardson v. Simon, 560 F.2d 500, 505 (2d Cir. T977) appeal dismissedT 435 U.S. 939 (1978); Real v. Simon, 510 F.2d 557, 563 (5th Cir. 1975); Nielsen v. Secretary of Treasury, 424 F.2d 833, 840-841 (D.C. Cir. 1970).

*/ 8 M. Whiteman, Digest of International Law, 1217, 1224 (1967) thereinafter Whiteman-Digest]; 6 J. Moore, A Digest of International Law, 1012-1027 (1906); 2 C. Hyde, International Law Chiefly as Interpreted and Applied By the United States, 890-891 (2d ed, 1947); William A. Parker (United States v. Mexico), Opinions of the Commissioners, 36 (1927).

**/ Moreover, the power to restore normal relations with a foreign government belongs to the President exclusively, U.S. Const., Art. II, and includes the “[p]ower to remove such obstacles to full recognition as settlement of claims *** .” United States v. Pink, supra, 315 U.S. at 229; United States v. Belmont, supra. Resolution of the hostage crisis and the claims settlement “eliminate *** possible sources of friction *** ” between the United States and Iran, and “rehabilitate] *** relations between this country and another nation *** .” United States v. Pink, supra, 315 U.S. at 225, 230.

*/ At least since the case of the “Wilmington Packet” in 1799 Presidents have exercised the right to settle claims of U.S. nationals by executive agreement. Lillich, The Gravel Amendment to the Trade Reform Act of 1974; Congress Checkmates A Presidential Lump Sum Agreement, 69 Am. J. of Intl. L. 837, 844 (1975) . That case “set a precedent which was to be followed in a long line of subsequent claims, settlement of which has been sought by the authority of the Executive alone.” McClure, W. , International Executive Agreements 44 (1941)Google Scholar. In fact, during the period 1817-1917, “no fewer than eighty executive agreements were entered into by the United States looking toward the liquidation of claims of its citizens *** .” Id. at 53. Throughout our history many claims of U.S. citizens have been remitted to arbitration by Executive Agreement. See, e.g_. , S. Crandall, Treaties: Their Making and Enforcement, 109-111 (1916); 79 Cong. Rec. 969-971 (1935) (listing 40 executive agreements, entered into between 1842 and 1931, providing for arbitration of claims against foreign governments); 2 C. Hyde, supra at 1409; 5 G. Hackworth, , Digest of International Law 403 (1943)Google Scholar; 12 Whiteman Digest, supra at 1267.

**/ For instance, in the recent United States-Peoples Republic of China Settlement, T.I.A.S. 9306 (1979), the United States agreed to accept $80.5 million in full settlement of the claims of American nationals against the PRC. Other Agreements similarly provide for the full settlement of specified claims. See, , United States-Egypt Claims Settlement, 27 U.S.T. 4214, T.I.A.S. 8446 (1976); United States-Hungary Claims Settlement, 24 U.S.T. 522, T.I.A.S. 7569 (1973); United States-Bulgaria Claims Settlement, 14 U.S.T. 969, T.I.A.S. 5387 (1963); United States-Poland Claims Settlement, 11 U.S.T. 1953, T.I.A.S. 4545 (1960); United States-Rumania Claims Settlement, 11 U.S.T. 317, T.I.A.S. 4451 (1960); United States-Yugoslavia Claims Settlement, 12 Bevans 1277, T.I.A.S. 1803 (1948). See generally, R. Lillich and B. Weston, International Claims: Their Settlement by Lump-Sum Agreements, 2 Vols. (1975).

*/ For example, claims commissions or their equivalent to resolve outstanding claims were established in 1871 (Spain), see, e.cj. , United States ex rel. Angarica v. Bayard, 127 U.S. 251 (1888); in 1839 and 1868 (Mexico), see e.g., Williams v. Oliver, 53 U.S. (12 How.) Ill (1851); Ailing v. United States, 114 U.S. 562 (1885); Peugh v. Porter, 112 U.S. 737 (1885); United States ex rel. Boynton v. Blaine, 139 U.S. 306 (1891); in 1871 (Britain) , see, e.g_. , Williams v. Heard, 140 U.S. 529 (1891); United States v. Weld, 127 U.S. 51 (1888); and in 1965 (Canada), see 17 U.S.T. 1566, T.I.A.S. 6114. Such arbitrations have often involved contract claims such as those involved here. See, E. Borchard, The Diplomatic Protection of Citizens Abroad 296, 299 (1915); 5 Hackworth, supra, 618-623. See generally Stuyt, Survey of International Arbitrations, 1794-1970 (1972).

**/ The choice of arbitration in the present case is particularly appropriate in light of Art. XXI (2) of the Treatyof Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights with Iran, 8 U.S.T. 899, T.I.A.S. 3853. In ratifying that treaty, the Senate gave its approval for the two nations to settle disputes regarding interpretation or application of the treaty by submission to the International Court of Justice or “by some other pacific means.” Arbitration is a pacific means of settlement. See, e.g., United Nations Charter, Art. 33(1). Because the Treaty provides for peace and friendship between the two nations, trade and commercial freedom, prompt and just compensation for the taking of property, constant protection and security for each other's nationals and proscribes unreasonable or discriminatory measures that would impair legally acquired rights and interests, the claims referred to the Tribunal involve disputes “as to the interpretation or application of the * * * Treaty.” Id. Art. XXI(2).

*/ 1 Whiteman, M. , Damages in International Law 275 (1937)Google Scholar Thereinafter Whiteman-Damages]. Lillich and Weston, supra, vol. 1 at 1. Panevezys Saldutiskis Railway Case, P.C.I.J. Ser. A/B, No. 76 (1939).

**/ See, e.g., United States-PRC Settlement, supra, Art. II (a), Art V. “Except as an agreement might provide otherwise, international claims settlements generally wipe out the underlying private debt, terminating any recourse under domestic law as well.” Henkin, L., Foreign Affairs and the Constitution 262 (1972)Google Scholar. See also Restatement (Second} of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States 628 (comment to §213)” (1965) . Cf. Ozanic v. United States, supra; Christoffer Hannevig v. United States, 114 Ct. CI. 410 (1949).

***/ Restatement, supra, §213; 8 Whiteman-Digest, supra at 1224.

****/ United States v. La Abra Silver Mining Co., 29 Ct. CI. 432, 512-513 (1894), aff'd 175 U.S. 423 (1899) Boynton v. Blaine, supra; Miller v. United States, 583 F.2d 857, 865 (6th Cir. 1978); United States ex rel. Keefe v. Dulles, 222 F.2d 390, 393 (D.C. Cir. 1954), cert, denied, 348 U.S. 952 (1955); U.S. ex rel. Holzendorf v. Hay, 20 D.C. App. 576 (1902). In fact, a claim may be presented even over the objection of the national whose claim is involved. 8 Whiteman-Digest, supra at 1224.

*****/ Borchard, supra at 365; Moore, Treaties andExecutive Agreements, 20 Pol. Sci. Q. 385, 403 (1905); Restatement, supra, §§212-213; 8 Whiteman-Digest, supra at 1216-1217.

******/ i whiteman-Damaaes .o supra at 275, See also Restate V See, e.g. , United States-PRC Settlement, supra, Art. II(by i United States-Yugoslovia Settlement, supra, discussed at 95 Cong. Rec. 8837-8838 (1949).

**/ 8 Whiteman-Digest, supr at 1217; William A. Parker (United States v. Mexico), supra at 36.The foregoing principles were summarized cogently by the Court of Claims:

When the national government urged upon Great Britain the demands of American citizens * * * those demands became reclamations by the sovereignty of this nation * * * and passed out of the region of mere private right into the domain of international law, and out of the hands of the citizen into those of his government. When they so passed, the authority of the national government over them became immovable and supreme * * * . [After] the United States received [the] sum * * * [awarded by the Tribunal], as a sovereign, and not otherwise * * * there existed no private claims of American citizens against Great Britain * * *; they were all obliterated by the act of the United States as a sovereign, in demanding and receiving satisfaction therefor. Nor were there, in law, any such claims against the United States. That

**/ continued, [onp . 3 7 1 . ]

**/ continued [from p. 3 70.]

sum was received by the United States in their sovereign capacity, unmixed, in law, withany private right, and unaffected by any legal obligation to pay out- any part of it to any one. * * * No failure on the part of Congress to authorize payment of those claims, or any of them, could ever authorize judicial recourse against the United States in this or any other court.

Great Western Insurance Co. v. United States, 19 Ct. CI. 206, 217-218, aff'd on other grounds, 112 U.S. 193 (1884). See also E. Borchard, supra at 366-367 (1915).

*/ United States v. Schooner Peggy, supra, 5 U.S. at 110; Aris Gloves, Inc. v. United States, 420 F.2d 1386, 1393-1394 (Ct. CI. 1970); U.S. ex rel. Holzendorf v. Hay, 20 D.C. App. 576 (1902); Henkin, supra at 263.

**/ Boynton v. Blaine, supra; Frelinghuysen v. Key, 110 U.S. 63 (1884) ; Williams v. Heard, supra; First National City Bank v. Gillilland, 257 F.2d 223, 226-227 (D.C. Cir.), cert, denied, 358 U.S. 837 (1958); 3 Whiteman-Damages, supra at 2046-2047 (1943); Restatement, supra, §214.

***/ F. Assets Corp. v. Hull, supra, 311 U.S. 470, 489 (1941); DeVegvar v. Gillilland, 228 F.2d 640 (D.C. Cir. 1955), cert, denied, 350 U.S. 994 (1956); First National City Bank v. Gillilland, supra.

*/ Indeed, at times Congress has authorized the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission to determine the amount and validity of claims prior to a claims settlement agreement and to provide that information to the Secretary of State, 22 U.S.C. 1643 et seq., where it remains available to be used by the Executive Branch in future negotiations to settle those claims.

**/ These statutes are discussed in detail in Part II, infra. In the context of the present case the “Hostage Act”, see pp. 32- 33 infra, provides additional support for the President's actions

***/ See Richardson v. Simon, supra; Real v. Simon, supra; Nielsen v. Secretary of Treasury, supra.

****/ H.R. Rep. No. 95-459, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. 17 (1977); S.Rep. No. 95-466, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. 6 (1977).

*/ The Act creates a comprehensive statutory scheme delineatinga foreign government's various immunities and amenability to suits in American courts. See generally, Ruggiero v. Compana Peruana de Vaoores “Inca Capac Yupanqui, Nos. 80-7595, 7597, 7599 (2d Cir. Jan. 15, 1981).

**/ See, e.g., Republic of Mexico v. Hoffman, 324 U.S. 30 (1945); Ex Parte Peru, 318 U.S. 578 (1943).

***/ Indeed, Congressional enactment of IEEPA in 1977, giving the President the necessary tools- to settle international claims, after enactment of the FSIA, evidences Congressional intent not to alter fundamental Executive practice in this area. This is confirmed by the fact that neither the language nor the legislative history of the FSIA purports to limit the President's powers under the TWEA which was on the books when the FSIA was enacted. Essentially, FSIA establishes the ordinary rules of immunity to be applied to a foreign state, while IEEPA and the TWEA provide the President the necessary powers to deal with emergency or war-time situations. See United States v. Yoshida International Inc., 526 F.2d 560, 578 (C.C.P.A. 1975).

*/ The United States does not concede that a claim by plaintiff for compensation will be within the jurisdiction conferred by Congress on the Court of Claims, see 28 U.S.C. 1502, or indeed any Court. See, e.g_-/ United States v. Schooner Peggy, supra, 5 U.S. at 110. Settlement of an international claim is not a taking, because the claim belongs to the United States, see pp. 14-15 supra, and because against foreign governments there can be no assured right of compensation. Avramova v. United States, 354 F. Supp. 420 (S.D. N.Y. 1973).

Gray v. United States, 21 Ct. CI. 340 (1886), is not to the contrary. Unlike the present situation, there the Court found a taking because the American claims were valid, would have been honored by the French, and were released in full by the United States. SeeAris Gloves, supra at 1396-1397 (Nichols, J. , concurring!“] Moreover, Gray was “strictly an advisory opinion which was not binding upon either of the parties and cannot be binding upon subsequent courts.” I_d. at 1393. As the Supreme Court said of Gray “[w]e think that payments thus prescribed to be made were purposely brought within the category of payments by way of gratuity, payments as of grace not of right.” Blagge v. Balch, 162 U.S. 439, 457 (1896).

*/ For example, in the instant casejust as an Executive Xicense was required to go forward with this litigation initially, see pp. 30-31 infra, the Executive retained full discretion under IEEPA to suspend that license. 31 C.F.R.

*/ continued [in next column,]

*/ continued 5 35.805; New England Merchants National Bank v. Iran Power Generation and Transmission Co., No. 79 Civ. 6380 (KTD)(Order, Nov. 5, 1980) See also, Chase Manhattan Bank v. United China Syndicate, Ltd., 180F.Supp. 848 (S.D.N.Y. 1960); Clark v. Propper, 169 F.2d 324 (2d Cir. 1948), aff'd, 337 U.S. 472 (1949).

*/ Additionally, the Executive Order suspending claims does not apply to “any claim concerning the validity or payment of a standby letter of credit, performance or payment bond or other similar instrument.” Executive Order No. 12,294, § 5 (Feb. 24, 1981)

*/ Article VII defines “claims of nationals” as:

claims owned continuously, from the date on which the claim arose to the date on which this agreement enters into force, by nationals of that state, including claims that are owned indirectly by such nationals through ownership of capital stock or other proprietary interests in juridical persons, provided that the ownership interests of such nationals, collectively, were sufficient at the time the claim arose to control the corporation or other entity, and provided, further, that the corporation or other entity is not itself entitled to bring a claim under the terms of this agreement.

*/ In agreeing to arbitration of most claims of United States nationals, Iran has relinquished any sovereign immunity and act of state defenses it might otherwise possess against such claims. The Agreement, therefore, will greatly increase the chances of recovery for many American claimants.

*/ In denying a TRO seeking to restrain transfer of Iranian assets in this country District Judge Gesell stated:

[T]he President's power to enter into this agreement and establish a special fund in effect indicating the creditors that can proceed against the Iranian funds here is beyond question * * * . We don't need to refer to any statute. It is a power that he can exercise under Article II, and he has exercised it.

Ebrahimi v. Islamic Republic of Iran, Nos. 80-3127, 3128, 3129, Tr. pp. 31-32 (D.D.C. Jan. 21, 1981).

*/ Where Congress desired to limit the President's powers under the Act, it specifically so provided. For example, the Act expressly excludes authority to control non-economic aspects of international relations such as personal communications or humanitarian contributions, 50 U.S.C. 1702(b)(1), (b)(2), and does not authorize the President to vest title to foreign property. See, e.g., H. Rep. No. 95-459, supra, at 15. Similarly, Congress intended to limit the power to control purely domestic transactions, as Presidents occasionally did under the TWEA. See, eg., id at 3-5,11.

**/ Executive Order No. 12,170, 44 Fed. Reg. 65729 (1979). [18 I.L.M. 1549 (1979)]

*/ The identical language of section 5(b) of the Trading with the Enemy Act had been interpreted as providing the Executive similar authority in a variety of international financial transactions. See, e.g., Propper v. Clark, 337 U.S. 472, 484-486 (1949); Sardino v. Federal Reserve Bank,, 361 F.2d 106 (2d Cir. 1966); Nielsen v. Secretary of Treasury, 424 F.2d 833, 838 (D.C. Cir. 1970).

**/ These specific regulations were authorized by the power to “regulate * * * any transfer * * * of,” Iranian assets, and the authority to “regulate * * * [or] prevent or prohibit * * * [the] exercising [of] any right, power or privilege with respect to” Iranian property. 50 U.S.C. 1702(a)(1)(B).

*/ On previous occasions Treasury had similarly revoked licenses with respect to blocked property. See, e.g_. , W. Reeves, The Control of Foreign Funds by the United States Treasury, 11 L. & Contemp. Prob. 17, 38 (1945).

**/ Contrary to the opinion of District Judge Porter (EDS Corp. v. Social Security Organization of the Government of Iran, Slip op. No. CA3-79-0218-F at 17-19-TN.D. Tex. Feb. 12, 1981)), the Executive Orders issued by President Carter on January 19, 1981 are valid. Judge Porter's ruling is now moot, because President Reagan, has expressly ratified the January 19 Executive Orders. Executive Order No. 12,294, §8 (Feb. 24, 1981). Furthermore, Judge Porter is incorrect. President Carter's orders took effect immediately upon issuance, which indisputably occurred before noon on January 20, 1981. While under the Agreement with Iran the United States was not required to terminate third party interests in [Opinion at I.L.M. p. 344]

**/ continued [on p. 379 . ]

**/ continued [from p. 378.]

Iranian property prior to the hostages' release, nothing precluded the President from taking that action earlier, and nothing in the Executive Orders was explicitly contingent on the hostages' release. Even if the provisions of the Executive Order were contingent on the release of the hostages, it is not unusual for an order, regulationor statute to have an effective date after the session of Congress expires or a cabinet official has left office, or contingent on some event to occur in the future, but at an unspecified time.

*/ See also 50 U.S.C. 1701(a)(1)(A).

**/ The authority to direct the transfer of Iranian assets Ts explicitly provided by IEEPA, and contrary to District Judge Porter's decision in EDS v. Social Security Organization of the Government of Iran, supra, at 20-27 the exercise of that authority does not constitute a vesting by the United States, which is precluded by IEEPA. When the United States vests foreign property, it strips the foreign power of ownership and takes title for itself. See H.R. Rep. No. 95-459, supra, at 15; McGrath v. Manufacturers Trust Co., 338 U.S. 241, 244 (194 9); Propper v. Clark, supra, 337 U.S. at 477 n.7. Under the Iranian Asset Control Regulations title to blocked property has never passed; indeed such transfers of title have explicitly been prohibited. 31 C.F.R. 535.201, 535.310. Obviously, there has been no vesting of Iranian assets still in the United States because except for that portion that Iran committed to fund the claims settlement program for the benefit of American claimants, the remainder is to be returned to Iran.

***/ The national emergency, remains in effect. 50 U.S.C. 1622, 1706. The decision of the political branches of the government on this question is binding on the courts. See, e.g., Sardino v. Federal Reserve Bank, supra, 361 F.2d at 109”.

*/ The 1977 Amendments to the TWEA removed from Section 5(b) the President's authority to control economic transactions during national emergencies, and transferred those powers to IEEPA. Thus, the grant of authorities in IEEPA parallels Section 5(b) of the TWEA, and interpretations of that Act are directly applicable to IEEPA. See H. Rep. No. 95-459, 95th Cong., IstSess. 14-15 (1977).

*/ Significantly, the blocking order in Orvis was issued prior to the 1941 amendments to the TWEA which added, inter alia, the powers to nullify or void any interest in alien property. 55 Stat. 839, Title III, §301 (1941). The President under IEEPA not only has the power to condition the creation of property interest, and then invoke the condition, but also the separate power to nullify or void any interest in blocked property even in the absence of any stated conditions or reservations.

*/ The Supreme Court's decision in Zittman v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 446 (1951) (Zittman I), decided two years before Orvis, is not to the contrary. In Zittman I the Court, construing the terms of a vesting order, denied the custodian's request that a state court attachment be declared null and void, with respect to the enemy debtor. Because the custodian had vested only the “right, title and interest” of the debtor-bank, he had voluntarily put himself in the shoes of the bank and therefore was subject to the attachment.

Unlike the present case, the creditor's attachment in Zittman I was obtained prior to the regulation prohibiting attachment, and not pursuant to a license specifically made revocable. Id_. at 452. Significantly, in Zittman v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 471 (1951)(Zittman II), the Court carefully confined its decision to the plaintiff's rightsin relation to the enemy debtor under the particular vesting order, and reserved the issue whether state court judgments or attachments could have any conclusive effect on final dispostion of the assets, id. at 474, the issue resolved favorably to the government in Orvis.

*/ The Executive's decision to consider the international agreement with Iran in force is binding on the courts. See, e.g., Clark v. Allen, 331 U.S. 503, 514 (1947); Terlinden v. Ames, 184 U.S. 270, 288 (1902).

*/ In fact, many of the claimants' attachments were invalid. The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, 28 U.S.C. 1610(d), in general bars pre-judgment attachments as “foreign relations irritants.” 122 Cong. Rec. 33532 (1976) (remarks of Rep. Danielson). The FSIA does keep in force, however, preexisting treaty provisions, including Article XI, 1(4 of the 1955 Iran-United States Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights (FCN Treaty), 8 U.S.T. 899. 28 U.S.C. 1609. See Eehring International, Inc. v. Imperial Iranian Air Force, 475 F.Supp. 383, 392-395 (D.N.J. 1979) . But see New England Merchants National Bank v. Iran Power Generation and Transmission Co., 502 F.Supp. 120, 124-125 Ts.D.N.Y. 1980), appeal pending, Nos. 80-3063, 81-8002 (2d Cir.); E. Systems, Inc. v. Islamic Republic of Iran, 491 F.Supp. 1294, 1300 (N.D. Tex. 1980).

Like numerous other FCN treaties, the Iran-United States Treaty waives immunity only for a commercial or business “enterprise * * * which is publicly owned or controlled,” but not for any other type of government agency. See, e.g., S. Exec. Rep. No. 5, 83d Cong., 1st Sess. 5 (1953); S. Exec. Rep. No. 5, 81st Cong., 2d Sess. 6 (1950); and cf. H.R. Rep. No. 94-1487, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 27 (1976). The “reaty waiver of immunity would apply to suits arising out of a purchase of goods by a government airline, for example, but not by the Army. At a minimum, then, all current attachments of Iranian assets are invalid under the FSIA and the Treaty except for those attachments of assets owned by governmentcontrolled business enterprises. This position is developed in detail in the United States' amicus curiae brief in Electronic Data Systems Corp. v. Social Security Organization of Iran,610 F.2d 84 (2d Cir. 197JT. That court did not reach the question.

*/ Among others, many oil importing nations, where Iranian assets have traditionally been on deposit, have committed themselves to honor international arbitral awards. Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Arbitral Awards, supra.

*/ The President has exercised his IEEPA authority to terminate the attachments and to direct the transfer of Iranian assets by Executive Order. In order to relieve the concern of those who hold Iranian assets this Court should apply the rule of law established by the Executive Order and formally vacate its attachment order.