A growing number of scholars call for downgrading the centrality of international anarchy in international-relations theorizing in favor of a focus on hierarchy (Hobson and Sharman Reference Hooghe and Marks2005; Lake Reference Lake2009; Hobson Reference Hobson and Sharman2014; Mattern and Zarakol Reference McCourt2016). But most forms of ‘international hierarchy’ pose no special problems for thinking of world politics as anarchical. ‘Hierarchy’ merely refers to any pattern of super- and subordination. Scholars already routinely place the ranking of states by status, economic roles, and military capabilities at the center of their scholarship (e.g. Lemke Reference Lemke2004; Towns Reference Towns2009; Paul, Larson and Wohlforth Reference Pratt2014).

However, one form of hierarchy among and across political communities, that involving governance, does contravene the states-under-anarchy framework. We argue that such governance hierarchies are likely ubiquitous features of world politics. In this article, we present a toolkit to help scholars recognize the myriad forms such hierarchies may take. We contend that the common practice of identifying anarchical relations from conditions such as the existence of independent diplomatic relations among actors, the de jure or de facto presence of a right to exit formal and informal governance hierarchies, or the observation of power-political behavior rests on deeply problematic assumptions about how governance arrangements operate. Some relations among some actors likely do take on anarchical forms, but we think that much of the action in world politics occurs under conditions that Donnelly (Reference Dickovick and Eaton2009, 64) terms heterarchic: involving ‘multiple, and thus often “tangled”… hierarchies.’

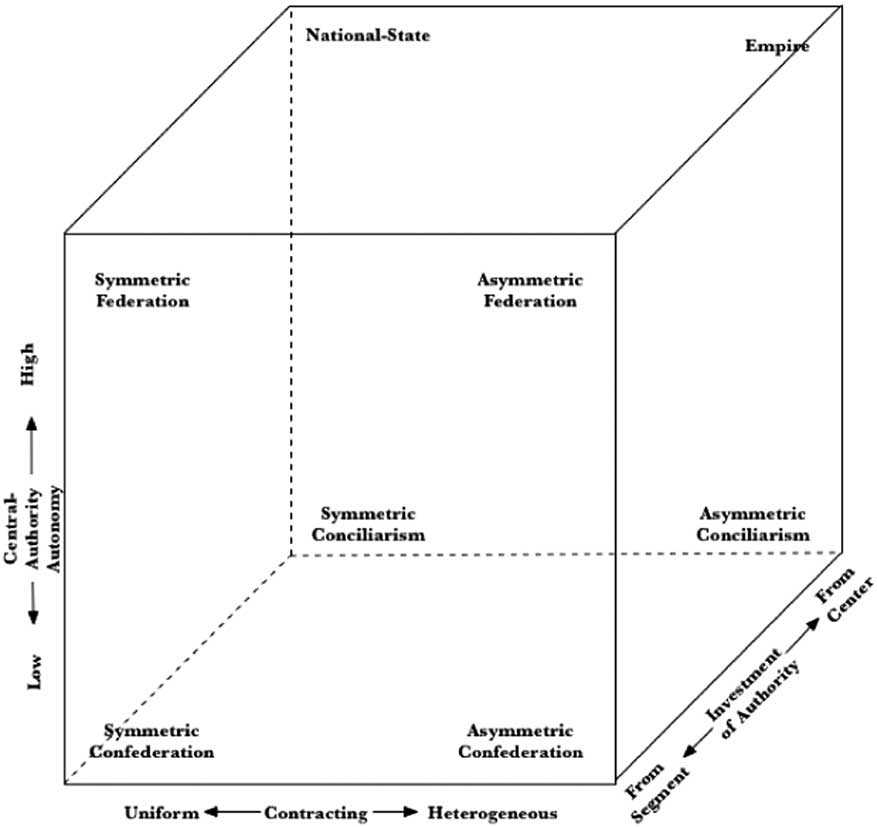

How can scholars incorporate variation in hierarchical, as well as anarchical, governance arrangements into international-relations theory? We argue for an explicitly relational account of governance – or political – structures (see Goddard Reference Goddard2009; Jackson and Nexon Reference Nexon and Neumann2009; and McCourt Reference McDonald2016). Patterns of governance relations assemble to create overlapping and nesting political formations. These operate within, across, and among sovereign states (Mansbach and Ferguson Reference Mansergh1996, 48–9). Moreover, we can parse these in terms of a limited number of ideal-typical forms: national-states and empires, as well as asymmetric and symmetric variants of federations, confederations, and conciliar systems. Real-world governance assemblages – both formal or informal and including those that characterize sovereign states – combine features of these ideal types.Footnote 1

This shift helps rectify a deep bias in international-relations and comparative-politics scholarship that helps perpetuate the states-under-anarchy framework. International-relations scholars tend to follow the lead of comparativists when it comes to, for example, classifying federal and confederal arrangements. Almost all of the cases of federations and confederations that comparativists study, however, are sovereign states. Because the empirical examples used to construct definitions of these forms display not insignificant centralization and enjoy relatively expansive governance authority, the result is a ‘national-state’ bias that leads scholars away from detecting governance hierarchies in more decentralized political communities where central organs – if they even exist – enjoy fairly limited governance authority. In international-relations scholarship, such governance structures often become misidentified as ‘anarchical bargains.’ In comparative politics, they often drop out of the field of view entirely.

Because comparative scholars usually exclude international organizations – such as the United Nations (UN), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the International Monetary Fund – from their universe of political communities, both they and international-relations scholars neglect the degree to which federal, confederal, and conciliar arrangements characterize such organizations and structure relations within them. Put differently, the typological problems that European Union (EU) scholars confront routinely are the leading edge of a better understanding of world politics (see McNamara Reference Ferguson and Mansbach2015). Wedged uncomfortably between a conventional federation and an international organization, the EU appears, as Pufendorf described the German Empire when compared to kingdoms of the 17th century, as an ‘irregular body… like a misshapen monster’ (Kalmo and Skinner Reference Kaufman, Little and Wohlforth2010, 19). This misshapenness, though, derives not from an error in reality but an unfortunate rigidity in theory.

Finally, in the study of international relations, these biases compress the tremendous variation found in the political forms of sovereign states. The states-under-anarchy framework does not prevent opening up the ‘black box’ of the state, but it focuses attention on a limited range of variation, usually related to varieties of democracy and authoritarianism. Thus, international-relations scholarship downplays the ramifications for world politics of, for example, the federative characteristics of the United States or the imperial characteristics of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

International-relations scholarship also has little to say about massive changes to political communities like the British empire, whose transformations from the mid-19th until the mid-20th century birthed literally dozens of currently sovereign states. It seems odd to proceed as if Canada and Belize only emerged as subjects of ‘international-relations’ scholarship once they received juridical sovereignty. Their domestic institutions looked almost exactly the same immediately before and after their independence; their relations with London increasingly resembled ‘foreign policy’ long before then. But that is how international-relations scholars operate. The states-under-anarchy framework logically entails that there must have been a phase shift – from not-state to state – far beyond that which we find in practice. To remedy these problems, students of world politics need a conceptual toolkit that can accommodate a wider range of relations than ‘hierarchy’ and ‘anarchy.’

The rest of this article proceeds as follows. We overview hierarchy-centric scholarship. We elaborate the major pitfalls of that literature: first, its tendency to lump together different types of hierarchy and thereby obscure how ‘hierarchy’ relates to the states-under-anarchy framework; second, the incomplete shift from identifying hierarchy – and governance hierarchy in particular – to studying variations among kinds of hierarchies; and, third, a related emphasis on the content of hierarchy at the expense of variation in formal analysis of its structure in terms of relation and position.

Next, we use the example of international-relations scholarship on empires to illuminate these problems. Scholars studying empires have most forcefully pushed in the direction that we call for. These insights form the basis for, in subsequent sections, the development of our typology of hierarchical forms. We build out our typology, its assumptions, and some of its implications. We illustrate these through a discussion of embedded imperial governance structures in the PRC and the evolution of British transnational governance. We then offer some concluding remarks.

The new hierarchy studies

Many international-relations scholars accept the assumption that anarchy distinguishes their field of study from other branches of political inquiry. This finds expression in Waltz’s (Reference Ward1979, 88) formulation that the ‘parts of domestic political systems stand in relations of super- and subordination. Some are entitled to command; others are required to obey. Domestic systems are centralized and hierarchic.’ In contrast, ‘the parts of international-political systems stand in relations of coordination. Formally, each is the equal of all the others. None is entitled to command; none is required to obey. International relations are decentralized and anarchic.’

Critics offer a number of problems with this formulation. It conflates distinct concepts of centralization and governance. It defines anarchy with reference to relations of authority despite also claiming that authority hardly matters to international processes. It downplays how most international systems, both past and present, involve ordered arrangements dominated by powerful actors – such as spheres of influence, informal empires, and patron-client relations (see Wendt and Friedheim Reference Weinberg1995; Krasner Reference Lake1999; Sylvan and Majeski Reference Sylvan and Majeski2009). And it wrongly implies that ‘hierarchy’ and ‘anarchy’ are opposites when the concepts occupy different dimensions. The opposite of hierarchy is equality; the opposite of anarchy is governance. As Barder (Reference Barder2016) writes, theorizing on that erroneous basis precludes ‘the possibility of multiple hierarchical social arrangements embedded within global anarchy.’

Renewed attention to the limits of an anarchy-centered approach has produced a new wave of scholarship to insist that hierarchy matters in world politics. This new hierarchy studies is marked by intellectual and substantive diversity. For some, hierarchy supplies the organizing principle of international-relations scholarship (Hobson Reference Hobson and Sharman2014). Others contend that anarchy remains a centrally important concept, but that we neglect significant ‘zones of hierarchy’ – how various dimensions of hierarchical stratification profoundly shape world politics.

It is challenging, to say the least, to weave a common research program from strands including standards of civilization, asymmetries in military and economic capabilities, compliance with international norms, regulatory arrangements, international institutions, and forms of interstate control. Some attempt to map the approaches of the new hierarchy studies. Mattern and Zarakol (Reference McCourt2016, 624), for instance, divide the field into approaches that stress a ‘logic of tradeoffs’ and those that advance ‘logics of productivity.’ However such efforts to understand the new terrain play out, we see two problematic tendencies in this scholarship: first, an emphasis on diagnosing the existence of hierarchy and, second, focusing on variation in its content rather than its form.

Studying the brute fact of hierarchical control produces important insights, such as McDonald’s (Reference McGregor2015) finding that the democratic peace is likely an artifact of great-power spheres of influence (see also Barkawi and Laffey Reference Barkawi and Laffey2002).Footnote 2 Nor do we dismiss the importance of, for example, studying hierarchy in terms of how cultural content stratifies world politics, or how actors navigate such stratifications (see Towns Reference Towns2009). But we agree with Donnelly (Reference Donnelly2015, 419–20), who argues that ‘hierarchy provides almost as poor an account of the structure of international (and national) systems as anarchy. It simply states that the pattern of stratification is not flat’. Replacing anarchy with hierarchy tells us little about ‘how a system is stratified – or anything else about the (many and varied) ways in which international systems are structured.’

Varieties of vertical stratification

Within the new hierarchy studies, we find five major categories of stratification relevant to world politics: socio-cultural hierarchy, defined by markers of status, prestige, and symbolic priority; class hierarchy, defined by positions in international systems of economic exchange and production; military-capabilities hierarchy, defined by latent and realized military capabilities; economic-capabilities hierarchy, often defined by aggregate share of global economic output or the size of markets (Drezner Reference Doyle2014, Ch. 5); and, finally, governance (or political) hierarchy, defined by patterns of political super- and subordination among social sites.

Much of the action in the empirical study of hierarchy focuses on relations among different patterns of super- and subordination in world politics. Some claim that discrepancies between status (socio-cultural) and capabilities (military and economic) hierarchies incline states toward revisionism or finding alternative ways to enhance their status (Wohlforth Reference Wohlforth2009; Larson and Shevchenko Reference Larson, Welch and Shevchenko2010; Ward Reference Waltz2017). Others seek to understand how an actor’s position in one kind of hierarchy influences its position in another. For example, socio-cultural hierarchies imply patterns of social dominance, which can beget political control and hence governance relationships. In contexts where status derives from possessing superior military capabilities or enjoying a large economy, military-capabilities and economic-capabilities hierarchies also manifest in socio-cultural terms. Hegemonic-order theories take for granted that both kinds of hierarchy may translate into governance hierarchies (Musgrave and Nexon Reference Neumann2018; Nexon and Neumann Reference Nexon and Wright2018).Footnote 3

Yet of these types, only governance hierarchy contravenes theories centered on international anarchy.Footnote 4 Governance hierarchies imply the presence of common authority, however strained, attenuated, jointly produced, or ultimately reliant on asymmetric coercive capability that authority may be. Governance hierarchies may manifest as de jure (formal) or de facto (informal) rule of one political community over another. Relevant actors may include states, international institutions, multi-national corporations, or any other relatively bounded social site.Footnote 5 These fundamentally contradict the assumption of no-rule essential for anarchy.

Some accounts of hierarchy stress this point. Lake’s (Reference Lake1999) relational-contracting approach develops a typology of dyadic security relationships. It ranges from anarchical alliances, in which the two parties retain all residual rights, to empires, in which one party gives up all residual rights to the other. Lake (Reference Lake2009) provides a theory of hierarchy as a more generalized social contract in which states accept the authority of a powerful actor so long as its leadership remains preferable to a return to anarchy. He measures the degree of hierarchy using multiple indicators, such as independent alliances and trade dependency, that also combine into unidimensional accounts of ‘more’ and ‘less’ hierarchy.

Lake misses important facets of governance hierarchy. Reducing variation in governance hierarchy to a unidimensional account of ‘degree of control’ may seem plausible if we remain wedded to a states-under-anarchy framework that assumes bright lines dividing ‘domestic’ from ‘international’ politics. But on Lake’s own terms there is no reason to exclude hierarchical relations within states from study. If that is the case, those bright lines should be erased. And if we think that relations vary on other dimensions besides the degree of control, then we need to specify these dimensions and their implications (see Cooley Reference Cooley2005).

Relationalism and governance hierarchy

To understand formal variation in the structure of governance hierarchies that appear at varying scales, we adopt a relationalist approach focusing on structural assemblages. Relationalism provides a productive way of theorizing international political structures (Jackson and Nexon Reference Kalmo and Skinner1999; Goddard Reference Goddard2009; Pratt Reference Finnemore2017). The kind of relational theory we deploy takes the transactions that constitute both agents and structures as the fundamental unit of analysis. Classic approaches define structures as ‘relative stabilities in patterns of interaction.’ Some scholars parse these in terms of practices and fields, others in terms of processes and figurations (McCourt Reference McDonald2016). These relative stabilities create opportunities and constraints for actors; they also play a role in constituting actors themselves (Goddard and Nexon Reference Goddard and Nexon2005, 36).

In this framework, anarchy obtains when a relation ‘between two actors’ or social sites is characterized by the ‘absence of relevant authoritative ties, either between one another or with a third social site’ (Nexon Reference Nexon and Neumann2009, 52–55, 14). Anarchical relations may emerge at any scale and in any space of political life. But so also may other political formations, including hierarchical ones. If hierarchical relations may attain at scales often described as ‘international,’ while anarchy may equally emerge at scales considered ‘domestic,’ then international-relations scholarship needs to exercise caution about treating anarchy as a boundary marker between them. It also means constructing theories of world politics that incorporate hierarchical arrangements.

We borrow from Tilly’s (Reference Tilly1998, Reference Tilly2003) ‘relational realism.’ Transactions create social ties between one or more social sites, such as individuals, corporate actors, or even social spaces. Social ties may prove fleeting or durable, but their patterns resolve into relative stabilities in patterns of interaction which appear as structures taking the form of networks of ties. Consequently, we can define those structures, including political formations, in terms of their network properties (Nexon and Wright Reference Parent2007; Nexon Reference Nexon and Neumann2009).

A relational approach calls attention to how political formations of various kinds may embed within, and even co-constitute, one another. We might identify a particular political formation – a social site at one level of aggregation – as having imperial network characteristics, but also find that its constituent social sites have, say, federative or national-state network characteristics. The boundaries of networks arise when ‘only a limited number of actors enjoy the right to form specific kinds of exchange relationships with actors outside of the network – to act as brokers between sites within one network and sites outside of it.’ When only a few sites ‘within each network “has the right to establish cross-boundary relations that bind members of internal ties,” then each network constitutes a discrete’ unit. Once boundaries are established, ‘every member of the network is distinguished from every other actor outside of it by virtue of a particular marker – a categorical identity,’ such as being the subject of an empire or the citizen of a national-state (Nexon Reference Nexon and Neumann2009, 45–46).

Importantly, boundaries – and social sites – may exist even if the sphere of authority remains limited. For instance, NATO only polices security relations among its members that are designated by its membership as alliance issues. Thus, Turkey recently exercised its veto to block NATO cooperation with Austria. That still leaves Germany and the United States free to engage in bilateral security relationships with Austria, but not as NATO cooperation.Footnote 6

Our approach stresses the analytical distinction between ‘form’ and ‘content.’ Simmel argues that, ‘In any given social phenomenon, content and societal form constitute one reality’ (Reference Simmel1971, 25). As Erikson notes, ‘Forms can be, on the one hand, types of associations (e.g., competition, domination, and subordination) or, on the other hand, geometric abstractions like the dyad or triad’ (Reference Emont2013, 226). While these different uses point to analytic tensions, they both wager that we can abstract from the specific content of relations – the meanings associated with them – to more general patterns. These patterns recur across time and space. The way that they position actors, and their overall forms, provides a basis for identifying similarities and differences in structural arrangements. They also allow for the theoretical elaboration of dynamics that follow from these similarities and differences (see Nexon Reference Nexon and Neumann2009, 64–65).

We agree with many relationalists that the analysis of the abstract properties of social relations provides only incomplete explanations of causal processes and outcomes, and that the ‘duality of tie and content’ often needs to be relaxed, if not overcome, in specific empirical analysis (Erikson Reference Emont2013, 228). At the very least, content generates the very properties of the relations that provide the basis for formal abstraction. Nonetheless, the distinction matters a great deal for theorizing governance hierarchies and for identifying structural variation in their relational structures.

Many hierarchy-centric scholars pay little attention to variation in the formal, abstract properties of social hierarchies – the number of levels of stratification, the distance between them, and how many social sites occupy positions at each rung – and how that might shape world politics. None that we know of, for example, take seriously variation along the continuum of linear and non-linear hierarchies (Chase 1980). When we do find attention to variation, it often concerns a single dimension of stratification – such as the number of great powers – and neglects the ties and networks that position those social sites in broader hierarchical structures.

Viewing structures in network terms allows us to conceptualize broader patterns of super- and subordination. For example, relational ties may place two actors in positions of relative equality in a larger network even if they never interact with one another. Two employees in a large corporation may occupy the same location in the overall hierarchy even if they work in different offices located in different countries. If we only consider the hierarchical ties between those two employees and their supervisors, we would misread the structure of the corporation. This highlights a major problem with strictly dyadic approaches to hierarchy, whether applied to corporate structures or to political communities.

Relational approaches to social structure provide a way of tackling variation in hierarchical formations and of identifying political forms that operate across traditional levels of analysis. They therefore allow us to treat the distinction between ‘domestic’ and ‘international’ levels of analysis as products of particular network configurations rather than an ex ante analytical categories. In short, they answer the challenge posed by Donnelly (Reference Donnelly2015, 419–20) about how to think about structure within hierarchy. Instead of treating world politics as characterized by a singular overall or deep structure, like anarchy, we should embrace the complexity of nested governance relations – and develop theoretical tools that allow us to identify and analyze them.

Hierarchical assemblages

We thus understand governance heterarchy in terms of ‘assemblages.’ We do not mean to incorporate the full theoretical infrastructure associated with assemblage theory (see Acuto and Curtis Reference Acuto and Curtis2014). Rather, we use the term to capture two sensibilities.

∙ Various political formations in world politics exist in mutually constitutive relationships that scale as networks of networks. Thus, asymmetric alliances among states may create an emergent political system with imperial properties, but relatively equal political communities may combine to produce a state with confederal properties. Empires, for instance, are often fractal arrangements superimposed on heterogeneous political formations of many different kinds, from principalities to bishoprics to confederations to city-states (Nexon Reference Nexon and Neumann2009).

∙ Despite how aggregation produces nested political forms, those political forms still ‘retain a level of autonomy’ such that they may ‘be detached and plugged into a different assemblage’ (Bousquet and Curtis Reference Bousquet and Curtis2011, 53). We think that unlike alternative terms, such as ‘configuration’, the notion of assemblage highlights the simultaneously autonomous, but interdependent, character of nested governance hierarchies (see also Sassen Reference Sassen2006, 4–6).

The term also highlights how many governance arrangements are assembled – intentionally or not – by the interactions of constituents. Many of the hierarchical forms that emerge in international and transnational relations are informal rather than formal, de facto rather than de jure. Any form of governance may combine informal and formal aspects. Efforts to better understand how indirect governance functions through moving beyond ‘delegation’ to include a notion of ‘orchestration’ suggest that logics often regarded as ‘informal’ may be present in both putatively international and domestic contexts (Abbott et al. Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2016).

Coupled with the fact that many of these relations involve only restricted domains of hierarchical authority, the lack of a declared hierarchy gives the states-under-anarchy framework a superficial validity. Doing so risks mistaking the distinction between ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ for one between consequential and inconsequential (see Lake Reference Lake2009, Chs. 1, 2). The important thing is the assemblage itself, regardless of whether it advertises its hierarchical status.

Lessons from theorizing empires

We argue that the procedures adopted by international-relations scholars of empire lay the basis for more general procedures for studying governance hierarchies. Moreover, some of the tensions we identify in existing scholarship on empire stem from its incomplete break from the states-under-anarchy framework – a problem that could be remedied with the tools we provide.

Empires fit poorly into the states-under-anarchy framework. For some international-relations scholars, the term describes a state form. Many of the ‘states’ involved in the 19th-century European concert system, such as Russia and the United Kingdom, were organized along imperial lines. But international-relations scholars also identify ‘empire’ as obtaining among states (see Savage Reference Savage2011). From one vantage point, theories of system-wide balancing failures – which often lead to empires – resemble the very currency of traditional security studies (see Hui Reference Hutchings2004; Kaufman, Little, and Wohlforth Reference Krasner2007). From another, those theories supply accounts of state transformation by describing the emergence of imperial polities.

Moreover, international-relations theorists interested in the question of contemporary empire face a fundamental problem: prevailing contemporary norms associated with the sovereign-territorial state system render ‘empire’ an illegitimate form of rule. Any contemporary empire, whether in the form of sovereign states or interstate relations, will therefore likely manifest as ‘informal.’ Consequently, only those who want to undermine a relationship will term it ‘imperial’ (as with critics of American alliance systems, Moscow’s actions in Russia’s near abroad, or the West’s relations with the developing world).

Thus, the most common procedure for identifying informal imperial relations among juridically autonomous political communities depends on blurring the distinction between comparative and international relations (Doyle Reference Donnelly1986, 11). In order to define empires, scholars often start by looking at recognized imperial polities, such as the Romans or the Ottomans. They then extract defining characteristics of empire, and try to determine if these obtain in interstate contexts.

Sometimes these characteristics are presented as categorical attributes, but some recent approaches, following Galtung (Reference Galtung1971, 89), associate empires with a relational structure: a rimless hub-and-spoke system in which a core exercises rule over peripheries, ‘interaction between’ peripheries is ‘missing,’ and ‘interaction with the outside world is monopolized’ by the core. Like all relational accounts of political organization, Galtung’s understanding of empire scales across multiple levels of aggregation. In principle, it applies to corporate offices, political parties, trade unions, regional governments, structures of control in some sovereign states, steppe nomadic empires, and relations among sovereign states (Motyl Reference Motyl1999; Nexon and Wright Reference Parent2007).

Of course, this describes an ideal type. Most of the relations among great-powers and clients that might qualify as imperial will usually involve more restricted domains of authority; informal interstate empires will almost never monopolize the external diplomacy of their subordinates or preclude inter-periphery relations. But these conditions also obtain in many historical empires (Nexon and Wright Reference Parent2007). The line between imperial hierarchy and anarchical relations often proves difficult to discern. For example, what if, as often happened in early modern Europe, a magnate in the French composite state mobilizes his military retainers, in alliance with a foreign monarch, against a centralizing core? Would we consider that anarchical balancing or violent political contention under empire (see Nexon Reference Nexon and Neumann2009, Ch. 3 and, especially, Deudney Reference Deudney1995, Reference Deudney2007; Boucoyannis Reference Boucoyannis2007)?

International-relations scholarship on empire, then, already employs relational analysis to identify a particular structural form of governance hierarchy and treat it as an assemblage. We contend that there is nothing special about investigating imperial governance structures in this regard. Scholars should be able to employ similar procedures with reference to federations, confederations, or other forms. Yet few in the new hierarchy studies discuss other forms of ‘domestic’ relations – for example, symmetric and asymmetric federations – at the international level (but see Weber Reference Weber1997; Skumsrud Andersen Reference Skumsrud Andersen2016), although we often find such references in attempts to understand the EU (e.g. Menon and Schain Reference Milne2006; McNamara Reference Ferguson and Mansbach2015).

Only in a few cases do domestic federative logics appear juxtaposed to international empires (e.g. Deudney Reference Deudney2007). But other ideal-types describe a host of informal governance arrangements within, among, and across sovereign states. Contemporary international-relations scholars pay inadequate attention to how such arrangements appear in more formal manifestations – whether as states or international organizations – as well as the implications that follow for understanding international politics (but see Deudney Reference Deudney1995; Rector Reference Rector2009; Parent Reference Parent2011; Weber Reference Weber1997).

Relationalist approaches to empire also highlight problems with conceiving of hierarchy as simply ‘more or less’ domination. Relational-contracting approaches, as noted earlier, treat hierarchy as a continuum based on the degree of residual rights held by the superordinate actor, with empire as the most hierarchical form (see Lake Reference Lake1999, especially 275). But the centers of federations, let alone national-states, may reserve more ‘residual rights’ with respect to their administrative units than empires. Empires certainly can exercise less intrusive and less effective hierarchical control than those two kinds of polities (see MacDonald Reference MacDonald2009). Reducing hierarchy to a question of ‘more’ or ‘less’ simply cannot account for sufficient variation in governance arrangements (Nexon and Wright Reference Parent2007, 259).

The residual hold of the states-under-anarchy framework also gets some relationalist accounts of empire into trouble. For example, Nexon and Wright (Reference Parent2007) differentiate between informal empire and hegemony based on the degree of ‘rule’ exercised by the core over subordinate units. In this, they follow a strategy that dates back to classical understandings in which ‘empire’ is a step beyond ‘hegemony’: ‘Control of both foreign and domestic policy characterizes empire; control of only foreign policy, hegemony’ (Doyle Reference Donnelly1986, 40). This renders distinguishing between informal interstate empires and hegemonies difficult, a problem that gives the ‘hegemony or empire’ debate about American foreign policy its intractable character.

Reflecting on empire leads to three analytic points. First, scholars could avoid the ‘hegemony or empire’ quagmire by breaking out of a convention that seeks to fit ‘hierarchy’ into a unidimensional space. Hegemony, ultimately, provides a useful way of reconciling interstate governance hierarchy with the states-under-anarchy framework. As Barder (Reference Barder2016) argues, hegemony ‘describes the mobilization of leadership’ to order relations among actors, not the forms that this ordering takes. Hegemony supplies one set of mechanisms for ordering politics. In itself, it tells us very little about the forms that result.Footnote 7 Important variation, both within hegemonic orders and between different hegemonic systems, involves the extent that actors establish governance relations that are more imperial, federative, confederative, or conciliar in nature (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2001, Reference Immerwahr2004). Thus, we submit that hierarchy-centric scholars ought to abandon attempts to think about hegemony as a distinct form of governance.

Second, scholarship on empire highlights the harms of conceiving of separable levels of analysis. The assumption of a demarcation between international systems and domestic politics as objects of analysis depends on a boundary created by states as containers of hierarchical governance – an ‘inside’ of political hierarchy separated from an ‘outside’ of political anarchy. But this assumption misleads, as the example of ‘informal’ empire suggests. Imperialized polities exist at a similar scale of political aggregation as autonomous states, but their relations with the core differ from both those found within national-states and those under anarchy. Moreover, since polities in informal interstate empires still enjoy diplomatic relations with their autonomous counterparts, we cannot simply declare the empire itself a state under anarchy.

Third, scholars should abandon the presumption that international-relations constitute a fundamentally distinctive area of inquiry relative to other fields of political science. Scholars who downplay anarchy in favor of complex interdependence already make this point (Farrell and Newman Reference Fabbrini and Brunazzo2014), but it takes on new urgency if transnational governance hierarchies play a more central role in theories of world politics. If some actors in the ‘international system’ exist in relations of political super- and subordination, then theories developed to handle relations among actors in other contexts can apply to international settings (see Cooley Reference Cooley2005). ‘Mechanisms and processes that hold within polities may also operate among and across them’ (McNamara Reference Ferguson and Mansbach2015; Musgrave and Nexon Reference Neumann2018).

Toward conceptualizing forms of governance hierarchy, international, or otherwise

We have established that governance hierarchies can be analyzed at different levels of aggregation; that they can be studied in terms of their network properties; and that a unidimensional scale is unlikely to capture the distinctions among them. Specifying how different forms of hierarchies relate to each other requires identifying salient dimensions along which they vary.

We contend that scholars can usefully categorize governance hierarchies along three dimensions. First, the degree that contracting among segments is uniform or heterogeneous. Second, the extent that central authorities enjoy autonomy with respect to constituent segments. Third, the direction of investment of authority – from center to segment or segment to center – which we might also think of, in a restricted sense, in terms of the division of ‘residual control’ (Lake Reference Lake1996, 7) between central authorities and segments.

We consider these dimensions useful in distilling much of what scholars already say – and do – in categorizing hierarchies. The typological space proves useful in resolving contradictions in scholarly practice, such as when theorists employ concepts analogous to one or two dimensions but not the third. The typology produces eight ideal-typical political formations at the vertices of these dimensions. These ideal types prove flexible because they do not assume levels of analysis ex ante; no form is essentially domestic or international. We thus enable a productive conversation among international-relations scholarship, comparative politics, and other disciplines in studying the dynamics and tensions of different hierarchical structures (see Barkey and Godart Reference Barkey and Godart2013; MacDonald Reference MacDonald2014).

These dimensions originated through an engagement with international-relations theories of empires. Nexon and Wright (Reference Parent2007) use variants of two of them – central-authority autonomy and heterogeneity in contracting – to generate the understanding of empire discussed in the previous section. That is, empires are governance assemblages (1) composed of segmented political communities (2) ruled from a core via local intermediaries on the basis of (3) distinctive compacts that set expectations about the terms of each core-periphery relationship (see also Barkey Reference Barkey2008, 9; Burbank and Cooper Reference Burbank and Cooper2010).Footnote 8

With an important addition and amendment, we can locate empires in the ideal-typical typological space presented in Figure 1. Empires display heterogeneous contracts between core and periphery and feature high central autonomy. But note that without a third dimension we cannot distinguish between an empire and an asymmetric federation using this definition (see Butcher and Griffiths Reference Butcher and Griffiths2017, 5n11). In some ways, that is correct: asymmetric federations resemble ideal-typical empires more than they do symmetric federations with respect to the status, rights, and privileges of constituent units (Stepan Reference Stepan1999, 21).Footnote 9 And yet common usage and intuition suggest an important difference between an ‘empire’ and a ‘federation.’ We argue that this third dimension should be understood as ‘investiture’: in ideal-typical terms, the claim that segments exist at the sufferance of the core in empires, but help to constitute the core in a federative body. This example motivates our discussion of why we think three dimensions prove necessary to capture variations in governance hierarchy.

Figure 1 Major governance forms salient to multiple levels of aggregation.

The three dimensions of governance hierarchy

Contracting: We use ‘bargain’ or ‘contract’ to refer to implicit or explicit understandings of the allocation of duties and obligations in a relationship (Nexon and Wright Reference Parent2007, 257). Some governance bargains are written in constitutions or sanctified by tradition, others amount to routine practices that constitute relations. They may be ‘entered into voluntarily or as a result of coercion’ (Lake Reference Lake1996, 7). Hegemonic bargains, for example, often mix coercion and mutual accommodation. But the fact that they result from significant power differentials accounts for why even the federative and confederative elements of order that result often take asymmetric forms (see Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2001).

Both international-relations and comparative scholarship appreciate the degree of heterogeneity of contracting between the center and segments. But the dimension of contracting is orthogonal to the difference between federations and empires. Thus, we incorporate not only ideal-typical empires’ differential bargains among constituent segments but also the debate between those who view federations as constituted by a common set of rights and responsibilities (Elazar Reference Ebbinghaus1987, 4) and those who see federalism as accommodating differential bargains (Tarlton Reference Tarlton1965; Watts Reference Watts1996, Reference Watts1998; Agranoff Reference Agranoff1999).Footnote 10

At the ‘uniform’ extreme, all segments enjoy the same bargains in their relationship to the central authority – as, for instance, states do in the federal bargain of the United States or as departments do in their relationship to France. At the ‘heterogeneous’ extreme, segments enjoy different rights and duties. Depending on context, these bargains may manifest as privileges granted to autonomous administrative units, constitutional carve-outs to benefit particular peripheries, or exceptions to particular features of international agreements. In practice, for instance, Quebec enjoys a distinctive relationship with Ottawa, and the United States is first among equals in NATO. Such distinctions often – but not always – derive from differential bargaining power.

The typology, of course, describes ideal-typical arrangements. Real political formations locate within the overall property space, not at its extremes. Thus, for instance, the bargains for (some or all) segments in polities we label empires may share common features, while asymmetric federation may manifest as choices on a menu nominally available equally to all segments but tailored to the preferences of only a subset.

Central authority autonomy: The second axis represents the degree to which central authorities act as independent political forces rather than as an agent of segmentary decision-making. It helps illuminate, for example, the differences between ideal-typical federations and confederations. Consider a collection of nomadic tribes whose leaders meet as equals to make common decisions about grazing rights, raiding parties, or making war. Having made these decisions, they abide by them (or not) without an administrative apparatus with independent authority. Such examples do exist: the Hanseatic League acted in concert despite usually lacking a strong central apparatus (Spruyt Reference Spruyt1996, Ch. 6). As a formation moves away from that extreme, the center takes on growing prerogatives over administrative, decision-making, and enforcement responsibilities. At the upper limit of central authority to act independently, a fully autonomous center makes decisions that bind the units – as in an ideal-typical federation or national-state.

In most contemporary national-level political units, central authorities may make final decisions without the express acquiescence of segments in at least some areas. In arrangements with comparatively low central-authority autonomy, some political mechanisms – such as legislative votes, a multiplicity of veto points exercised by segmentary authorities, voluntaristic funding mechanisms, and so on – restrict the center’s ability to act without consent of the segments. In intermediate arrangements, central authorities may enjoy independent authority to act subject to ex-post checks by segments, or central authorities must consult with segments before acting, even if they retain an ability to act on that advice independently.

We develop this line of argument throughout the rest of this article, but here we stress an important point of our quasi-hypothetical nomadic confederation illustration. International-relations scholars and comparativists might code such an assemblage as anarchical. Yet it does involve governance hierarchy via the expected constraints and opportunities generated through joint decision-making. MacDonald (Reference McNamara2018) argues that strategies of orchestration often deployed to generate compliance in such arrangements predominate under anarchy. But because such tools are mechanisms of governance, we therefore question the utility of calling such arrangements anarchical, particularly in the presence of more-or-less routine practices of joint decision-making of one form or another.

Investiture of authority: The final dimension deals with the ultimate locus of authority. Consider two ideal-typical systems that display autonomous central authorities making asymmetric bargains with constituent units. So far, this equally describes asymmetric federations and empires. In ideal-typical empires, however, the rights and duties of segments are, de facto or de jure, granted by – and limited by – the center. In ideal-typical federations, by contrast, the rights and duties of the center are, de facto or de jure, granted by the segments.Footnote 11 Resolving this tension highlights the need for a third dimension. In contemporary political theory, we might call this dimension ‘sovereignty.’Footnote 12 It is also analogous to understandings of the holder of residual rights in relational contracting theories (cf. Lake Reference Lake1999, 7). We consider the concept more general than either usage captures. The critical point is who has the ability to invest political actors with legitimate and final authority. Hence, we use the term ‘investiture’ to capture this balance of authority.

Failing to account for the question of who invests whom leads to conceptual problems. As we argued earlier, Nexon and Wright (Reference Parent2007) would define both asymmetric federations and imperial formations as ‘empire.’ That is an error. In federations, the center autonomously exercises a great many contractual rights, but ‘residual rights’ remain with the segments. In empires, the segments may enjoy a variety of contractual rights, but ‘residual rights’ remain with the center. The distinction between the voluntaristic nature of federalism and the, well, imperialistic nature of empire serves as our inspiration for capturing why these forms must be distinguished (e.g. Lake Reference Lake1999, 275).

Once again, we stress that we are dealing with ideal types and that real-world units will lie within these spaces, not at the vertices. The United States, for example, has seen de jure, as well as even more significant de facto, shifts in the balance of ‘investment’ from the states to the central government that have layered national-state properties onto a federative architecture. Such a narrative explains why the shift from the Articles of Confederation to the Constitution, or from the pre-Civil War to the post-Civil War period, changed how investiture in the US government is understood.

Concrete cases illustrate the ideal-typical dimension of investiture. In Russia, for example, the center has combined and rearranged provincial boundaries (Goode Reference Goode2004), suggesting central investiture of authority. A similar process in the United States would be nearly unthinkable (e.g. Levy Reference Long2007). Such a distinction suggests that, regardless of constitutional niceties, the United States remains relatively federative while Russia remains more imperial.

Attention to the investment of authority helps us break from the straightjacket of blunt distinction between anarchy and hierarchy. In sovereign state systems, the right of investiture remains de jure tied to the governments of sovereign states – except, not insignificantly, in the procedures and implications of receiving UN recognition as a sovereign polity. Thus, many realists claim that the existence of treaties and many international organizations does not alter the fundamentally anarchical character of relations among states. After all, ‘nothing’ really precludes states from revoking those concessions – other than economic, normative, or military costs. And, unlike most domestic political formations, international arrangements usually include a right of exit, usually specified in legal terms and certainly in practice. If ‘hierarchy’ requires the sorts of assumed-to-be-indissoluble relations scholars assume hold within states, then such features serve as evidence of anarchy. Yet this argument produces absurdities. Taken to its extreme, such a perspective would lead us to conclude that the EU is not a governance assemblage because states (like the United Kingdom) can trigger Article 50. It also produces yet stranger anomalies: if secessionists in Quebec or Scotland gain independence through legal means, that outcome cannot reasonably imply that relations among constituent segments in Canada and Britain were previously anarchical. Adopting a perspective of broader types of hierarchical relations, however, shows that the problem lies in an artificial distinction.

More generally, the brute fact that states change and die highlights the perils of fixating on the ‘formal-legal’ dimensions of sovereignty when thinking about governance assemblages (see Lake Reference Lake2009, 24–8). Yes, governments are ‘jealous’ of their sovereignty. An expansive web of international regimes work to reinforce the rights and responsibilities of enjoying status as a sovereign, even as it exerts governance over those rights and responsibilities (Boli and Thomas Reference Boli and Thomas1999). This means that, ceteris paribus, we should expect interstate governance assemblages to tend toward segmentary investment. But it does not mean those relationships are purely anarchical.

Forms of governance in world politics

These three axes produce eight basic ideal-typical forms of hierarchical systems: empires and national-states, along with symmetric and asymmetric versions of federations, confederations, and conciliar arrangements.

Empires and national-states, the most commonly considered forms in international-relations scholarship, share high levels of central authority autonomy and investiture which flows from the center to the units. They differ, however, on the level of uniformity in contracting. While empires engage in heterogeneous contracting, juggling different relationships with different segments, national-states’ uniform contracting allow segments to essentially collapse into administrative units of the center. In France, often cited as close to an ideal-typical national-state, the central government enjoys essentially unfettered authority to act in any government domain. Its segments offer little resistance: although its regions elect councils, any ability they have to act is based on the acquiescence of the center (Le Gales Reference Le Gales2008). With high central authority to act autonomously, intermediate authority that is simply an extension of central authority, and a lack of differentiation among the segments, national-states take on a unitary character.

Compare those dynamics to a federation. While federations also exhibit high levels of central authority autonomy, the fact that investiture flows from segments to the center creates a system where central authorities and segments each possess areas over which they maintain final authority, often divided based on territorial demarcations (Riker Reference Riker1964; Wildavsky Reference Wildavsky1967; Bednar Reference Bednar2008). As a consequence, it is much harder for Washington to tell Arizona what to do than for Paris to instruct Normandy. Symmetric and asymmetric federations are likely to have different points of tension, as both uniformity and heterogeneity can prove troublesome given differences in bargaining power. However, these tensions will often involve multilateral bargaining among the segments and center, rather than the bilateral bargaining that predominates in empires.

In systems defined by low central authority autonomy, segments limit the center’s independent decision-making. These hierarchies invert conventional understandings of the term; they expose the variety of possible hierarchical relationships. Confederation combines low central authority autonomy with investment of authority that flows from the segments. This creates a political formation likely limited in its activity but effective when segments can agree on a course of action. In confederal forms, it is central authority that is an outgrowth of the segments’ authority. Confederative elements exist in systems as diverse as the Helvetic Confederation (Switzerland), the United Arab Emirates, NATO, and the WTO. Sovereign state systems tend to produce interstate governance hierarchies, in both ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ varieties, with significant confederative elements. This implies more explicit attention to how these features appear, and configure differently, in alliances, leagues, and intergovernmental organizations.

The full range of combinations of attributes indicated by this typology also reveals the possibility of conciliar forms of hierarchy, where central authority autonomy is low and investiture flows from the center to the segments. Since this form is (we think) unfamiliar, we have borrowed the terminology to describe it, perhaps problematically, from models of papal authority that became influential in the medieval period in order to term these ‘conciliar’ polities (Sigmund Reference Sigmund1962). Conciliar systems are not merely logical possibilities. They reflect arrangements and processes in the real world. Some university administrations may approximate conciliar systems, as when the university president, vice-chancellor, or provost invests department chairs but can themselves be removed via the coordinated actions of such intermediaries. Similarly, constitutional monarchies in which the crown invests a prime minister but can only ‘act’ on ministerial advice resemble conciliar forms.

However, conciliar political formations are probably rare in world politics. Thinking through the problem of effective decision-making in such organizations suggests why. Such formations are not structured to facilitate dynamic leadership or flexible responses to new situations. In a competitive international system, failing to allow for effective governance may place polities at risk of extinction. But even if pure conciliar systems are scarce, we think it helpful to consider governance arrangements that contain elements of conciliarism – such as processes by which systems with confederal or federal properties add members. This is, after all, the system used in the UN, and informally via coordinated recognition by multiple states, to admit new sovereign states into the international order. Being invested as a sovereign state by other sovereign states is no small matter, as it opens up a wide range of perquisites and opportunities.Footnote 13

Dynamics of governance assemblages

Thinking through the relationships among polities in this dimensional space helps contrast the political tensions, dynamics, and recurrent outcomes of different polities. For instance, segments disadvantaged in bargains both in imperial formations and in asymmetric federations may harbor similar grievances toward the central authority. But differences in the source of investiture in these systems helps explain why these grievances often play out differently. An empire’s core might decide to rearrange, replace, or combine troublesome peripheries, but such strategies will not be available to an ideal-typical federative core.Footnote 14 In a federal arrangement, the greater authority of segments means that contracts are more likely to reflect the existing concerns and priorities of the segments. When those contracts no longer satisfy, there are more likely to be institutionalized collaborative mechanisms for segments to renegotiate deals.

The typology also suggests why features associated with each form may arise naturally from their structure. Many scholars describe the structure of empires as ‘rimless hub-and-spokes,’ for instance. The typology suggests that such structures could emerge organically from the logic of the three dimensions presented here. Empires, asymmetric federations, confederations, and even asymmetric conciliar systems share heterogeneous bargains that disproportionately benefit (or penalize) some members. Unlike other cores, however, imperial cores should have a direct interest in preventing segments from forming inter-peripheral arrangements. Allowing such connections to form in empires would raise the possibility of coordinated revolt and diminishing of the core’s privileges within the system (Motyl Reference Motyl1999).

By contrast, asymmetric federal and confederal systems also possess a hub-and-spoke system, but in such systems lateral connections are not merely tolerated but often inscribed into the compact. Many real-world confederations develop some degree of central-authority autonomy, but the existence and prerogatives of the central authority remain, in an important sense, the manifestation of the lateral connections that exist among segments enabling them to empower the center. Federations, both symmetric and asymmetric, also permit fora through which lateral connections may be forged (Rodden Reference Rodden2004, 491; Wibbels Reference Wibbels2005, 7). The fact that investiture is already presumed to run from segment to core in such relations may help explain these differences, and implies dynamics that might lead, for example, confederative arrangements to become more federative, such in the replacement of the Articles of Confederation to the American Constitution.

More generally, this approach allows theorists to normalize regularities that might appear as pathologies if we simply assume that one form or another is ‘natural.’ If we assume that a national-state formation’s efficiency and uniformity makes it normatively more desirable than other forms, then the heterogeneous contracting of an empire or the bounded central power of a federation will look deviant. But this schema does not array political formations along a continuum from better to worse; it simply describes the sorts of dimensions along which governance assemblages may differ.

World politics as nested governance assemblages

Once we think about world politics in terms of assemblages of relational political structures, then the international system looks, per Donnelly, heterarchical. Polities with imperial characteristics, for instance, may themselves be segments within confederal or conciliar arrangements. Some empires take polycentric forms, such that something like a confederacy exists among multiple segments that, jointly, rule an empire, as in the case of the Triple Alliance – the ‘Aztec Empire’ (Trigger Reference Trigger2003, 390–92). Such ‘nesting’ (Ferguson and Mansbach Reference Mansergh1996, 393–98) of political forms matters a great deal to theorizing governance hierarchy in world politics.

Moreover, recognizing multidimensional typologies of hierarchy matters for how we think about international change. For instance, Long’s (Reference MacDonald2015, 222) survey of Latin American responses to US dominance provides insight into how segments within governance hierarchies may influence the core’s policies and outcomes. Such investigations of hierarchy recognize more complicated behavior than Lake’s (Reference Lake2009) assumption that states trade sovereignty to receive benefits from the more powerful state. However, Long’s framing of this issue solely in terms of acceptance or rejection of hierarchy risks confusing the relational dynamics within governance hierarchies for a lack of hierarchy. Although ‘changes in the terms of asymmetrical relationships’ initiated by weaker states could include a ‘rejection of hierarchy’ (Long Reference MacDonald2015, 223), they could also result in the maintenance of hierarchy while reducing central-authority autonomy or asserting that segments, not the core, invest authority.

Similarly, paying attention to the full variation in heterogeneity of bargaining makes sense of systems that largely appear as national-states yet display heterogeneous bargaining. Even despite recent federalizing reforms, for example, the Italian government’s interactions with most regions closely track those of a national state. By contrast, Italy’s relations with autonomous regions more closely resemble those of an asymmetric federation (Fabbrini and Brunazzo Reference Erikson2003, 104). In the contemporary United Kingdom, Westminster manages several types of relationships with Britain’s constituent parts, some of which look much like asymmetric federation (Bogdanor Reference Bogdanor2001). This variety is likely only greater in systems that resemble federal or confederal forms in non-domestic contexts, such as among states or transnational actors.

Thus, we agree with Donnelly (Reference Dickovick and Eaton2009, 2015) that we can generate many of the same dynamics associated with anarchy – such as bandwagoning, problems of credible commitment and ways of overcoming them, principal-agent problems, and so forth – from governance heterarchy. Even balancing behavior has no special relationship with anarchy (Deudney Reference Deudney1995; Boucoyannis Reference Boucoyannis2007). This should not surprise anyone. Virtually the entire toolkit of international-relations theory deploys mechanisms and theories from hierarchical contexts to make sense of the putative politics of anarchy. All of these dynamics exist in, and even borrow from the study of, domestic politics (compare Wagner Reference Wagner2007).

Indeed, many of the dynamics we associate with anarchy may follow from the overlapping of different governance assemblages – including states – which complicate the exercise of governance without meaning that governance is absent. Recognizing such overlapping areas, identifying their constitutive political structures, and theorizing about how they might interact should help us to detangle world politics into its multiple and complex hierarchies (Donnelly Reference Dickovick and Eaton2009, Reference Donnelly2015).

If we are correct, then the boundaries between comparative politics and international relations do significant damage to our understandings of political formations, particularly ideal-typical federations and confederations. Comparativists’ understanding of these forms have been shaped by the fact that ideal-typical federal and confederal political communities resemble international heterarchy (or anarchy) more than they do contemporary domestic arrangements. In our typological space, then, most recognized ‘federal’ and ‘confederal’ states are already shifted toward national-states, distorting our understanding of what can be attributed to their federal or confederal nature.Footnote 15

Consequently, international-relations scholarship has missed the degree of the applicability of the concept of federation to international communities (although see Deudney Reference Deudney1995, Reference Deudney2007). This is, as we argued earlier, even more the case with confederations. At the extreme, as the typology makes clear, confederal arrangements may involve nothing immediately recognizable as a central administration, but feature instead meetings among representatives of otherwise independent segments that invest an organization with the ability to act. Comparatively few treat military alliances, leagues, and concerts as governance arrangements. Far fewer explicitly study them as variations of political formations that exist across time and space.

Armed with incomplete definitions, scholars mistake the objects of their study. International-relations scholars overestimate the degree of ‘anarchy’ in world politics (Donnelly Reference Dickovick and Eaton2009; Lake Reference Lake2009; Donnelly Reference Donnelly2015). They conflate the presence of exit options, coordinative decision-making, or governance-via-orchestration with the absence of political hierarchy. Comparative-politics scholars sometimes assume that relatively high levels of central-authority autonomy constitute confederations or require too much central investment of authority to recognize federative relations (Weber Reference Weber1997, 35). We think that a more proper ideal-typical typological space helps provide a more productive and generalizable foundation for analysis.

Consider NATO as a security confederation. Seen in this light, its persistence long past the extinction of its original threat (NATO has outlasted the German Democratic Republic) should prove much less puzzling than if studied simply through the lens of balance-of-threat theory. This also suggests that its dynamics, evolution, and impact on its members should be analyzed with reference – implicit or explicit – to comparable governance assemblages.

Moreover, the logic involved in those comparisons that we do make tend to run in one direction: from domestic governance arrangements to international ones. Students of domestic and other non-international spheres rarely borrow from the international-relations literature, aside from the claim that states sometimes ‘descend into anarchy.’ Comparativists risk making the same mistake from the other direction by excluding a variety of federative and confederative relations that take place at the ‘international level’ from their universe of cases (Rodden Reference Rodden2004, 492). That perspective ignores state-like governance structures that may exist between or across states (Elazar Reference Ebbinghaus1987, 38–60; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hui2003). Yet national and transnational labor confederations clearly exist (Ebbinghaus Reference Drezner2003), as do imperial structures within bureaucracies and multi-national corporations (Cooley Reference Cooley2005) and even variations in the organization of fashion houses (Barkey and Godart Reference Barkey and Godart2013). These political formations are part of the comparative universe of governance assemblages.

Research trajectories and illustrations

In this section, we sketch out some implications for research and, inter alia, provide illustrations of what this approach to complex political hierarchies entails. However, before doing so we wish to stress that while we think our typology fruitful, it does not preclude the use or development of others with application at multiple scales of political life, as with Cooley’s (Reference Cooley2005) organizational hierarchies.

Comparative dynamics

Comparing hierarchical governance assemblages is not simply a matter of categorizing a broad number of political formations by constituent institutional isomorphisms. Instead, comparisons should also lead to better-specified insights about how variation in governance hierarchies – in features, scale, and configuration with other governance arrangements – alters the dynamics of political formations. By the same token, recognizing similarities at different levels of aggregation should help us understand what can be attributed to general classes of systems and what needs investigation at a specific level.

This kind of analysis is, as prior sections emphasized, probably most developed in the study of empires and ‘informal’ empires. Examples abound Lake (Reference Lake1999) compares the Soviet Union’s relationship to the Warsaw Pact to imperial formations; Lanoszka (Reference Lanoszka2013) argues a key difference between NATO and the Pact involved whether the units or the superpower was understood as having the balance of residual authority (what we call ‘investiture’). Cooley and Nexon argue of the US basing network that:

The overall structure of the U.S. basing network looks like what John Ikenberry calls a ‘neo-imperial logic’ that ‘take[s] the shape of a global “hub and spoke” system’ based on ‘bilateralism, “special relationships”, client states, and patronage-oriented foreign policy.’ Within this structure, though, are arrangements that more closely resemble ‘liberal’ and ‘multilateral’ hegemonic orders—such as those among the United States and NATO members—where states retain their sovereignty but their relations are informed by a common security purpose, shared values, multilateral agreements, and coordinating mechanisms (Reference Cooley and Nexon2013, 1035).

In our framework, what Cooley and Nexon describe as ‘liberal’ and ‘multilateral’ hegemonic ordering involves (generally asymmetric) federative and confederative governance hierarchies. But, like many others, they only nod toward trying to analyze non-imperial hegemonic ordering through comparison with non-imperial forms. Scholars who come closer, such as Ikenberry (Reference Ikenberry2001) in his discussion of ‘constitutional orders,’ do so non-systematically, while Weber (Reference Weber1997) compares confederations to alliances mostly in terms of why states might opt for them.

However, international-relations theory’s assumption that informal interstate empire is the only kind of empire that matters today obscures the importance – and even the existence – of domestic imperial formations. Despite claims that empires are dead, we think imperial formations do exist, and some are passing as sovereign states. At least two of the UN Security Council’s permanent five members – the Russian Federation and the PRC – display imperial characteristics in their domestic organization. A third – the United States – maintains a formal empire in its overseas insular possessions (like Guam) and Caribbean possessions (like Puerto Rico).Footnote 16 And Smith (Reference Smith1991) argues that Canada’s confederal arrangements reflects the ongoing influence of imperial arrangements between the Crown and the peripheries.

To illustrate why the existence of domestic empire matters for international-relations theory, we sketch the implications of revisiting the PRC through the lens of our typology. The PRC has long engaged in classic colonial imperialism in at least two major regions: Tibet and Xinjiang.Footnote 17 In its struggle to govern these regions, Beijing has employed every imperial tactic at its disposal, including replacing native elites with newly recruited intermediaries closely monitored by trusted functionaries and limiting each region’s contact with the outside world (Terrill Reference Terrill2004, 3).

PRC governance hierarchies resemble imperial structures in more ways than their relations with ethnic-minority areas (or the special autonomous regions of Hong Kong and Macau). In its ordinary operation the PRC government – especially as mediated through the Communist Party of China – often resembles more a series of negotiated accommodations, indirect rule, and differential contracting with provincial authorities, local governments, and commercial enterprises that approximate hub-and-spoke arrangements (McGregor Reference McIntyre2010; Shirk Reference Shirk2007, Reference Shirk2014). This should not come as a surprise: Motyl (Reference Musgrave and Nexon2001, 18, 47–52) suggests a structural isomorphism between centralized one-party political systems and imperial formations.

The degree of heterogeneous contracting, the fact that investiture remains with (and is jealously guarded by) the center, and the degree of central-authority autonomy point to the conclusion that much of the Chinese political hierarchy not only resembles imperial rule but, in one sense, is an imperial organization of intersegment relations. (We note that our conclusion is descriptive, and in no way pejorative.)

With the tools to recognize imperial formations disguised as national-states, like the PRC, we can productively pose questions that the states-under-anarchy framework render difficult, including whether imperial cores behave differently than national-states in international relations, and whether these differences vary based on whether the empire is formally internal or external. Doing so will help scholars identify and answer questions that are obscured so long as the PRC is understood as a Westphalian state with pathologies rather than a looser, more disaggregated form of government (Hameiri and Jones Reference Hobson2016). These shifts in perspective help illuminate probable tensions in particular cases. For example, in the long term the PRC’s differential treatment of Uighurs, for instance, may complicate Chinese relations with other Muslim societies – an outgrowth of the PRC’s imperial structure that will at the least require delicate handling (Emont Reference Elazar2016).

Thinking about China’s hierarchy as imperial might also open new ways of understanding regime change and political transformation. While comparative scholars apply general models of democratization and authoritarian stability when considering possibilities for regime change in China, the tensions facing autocratic leaders in imperial formations are likely different than in national-states. Chinese leaders may have additional opportunities for manipulating the bargains between the center and segments in ways that are reminiscent of imperial strategies of dividing-and-ruling. However, regime change in China could entail a continuation of fundamentally imperial relations with a new ruling class – or could conceivably entail a shift toward a more national-state or federal political arrangement, or even imperial disintegration.

State transformation

The study of state formation – more properly, transformation – is perhaps one of the greatest victims of distortions induced by insisting on an anarchy-based distinction between international and comparative politics. Once we see world politics as an arena of complex hierarchies, it becomes clear that ‘state formation’ is not a process limited to the consolidation of national-states and subsequent evolution in those forms. International and transnational ‘states’ are, and always have been, everywhere (Mansbach and Ferguson Reference Mansergh1996), and so state transformation has always entailed interactive processes of governance transformation at multiple scales – from Latin Christendom (Bartlett Reference Bartlett1993) to the evolution of the Ottoman Empire and its ‘periphery’ (Barkey Reference Barkey2008) to contemporary globalization (Cerny Reference Cerny1995).

Once we break out of the states-under-anarchy framework, the study of state transformation is more properly understood as the study of transformations in governance. The ideal types we specify are historically ubiquitous and appear at many scales. They also likely contain tendencies that help explain their transformation and persistence, as scholars of empire have long explored. While hierarchy-centric understandings of state transformation exist – as in Ziblatt’s (Reference Ziblatt2006) comparisons of trajectories toward federal and national-state formation in 19th-century Germany and Italy – more careful considerations of how types of hierarchical arrangements change would help formalize such inquiries.

The explicit recognition that new political entities are inevitably formed from the transformation – or detritus – of existing political structures should encourage scholars to follow different forms and political entities across levels of analysis. For instance, it might help scholars understand that ‘international relations’ do not end when conquest leads to the formation of an empire or comparativists to view processes of international confederation as akin to confederal dynamics in a ‘domestic’ sphere. As an illustration, we follow the mutual transformations of the British Empire and its constituent polities to demonstrate how using explicit, structured comparisons of governance hierarchies adds to our understanding of state transformation.

London’s original contract with settler colonies in British North America and the antipodes displayed basic imperial logics: the core invested the segments, core-segment bargains were heterogeneous, and the peripheries could not bind the core. Yet over the late 19th and early 20th centuries, agitation for a revision of that bargain emerged (Bell Reference Bell2007, 160), leading first to London’s granting certain settler colonies – what later became Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa – ‘responsible self-government’ (McIntyre Reference Menon and Schain2009, 73–76) and then Dominion status (McIntyre Reference Menon and Schain2009, 76–81).

By the beginning of the First World War, relations between core and these privileged segments had shifted toward asymmetric federalism as Dominion parliaments gained substantial prerogatives over home issues. However, in crucial areas of war, peace, and trade, they remained subject to Westminster, which could act without their input in matters that nevertheless bound them. For example, in 1914, the UK government’s decision to take up arms against Germany bound the whole empire to enter the conflict, Dominions included. The fact that the imperial core retained the prerogative to invest segments meant that despite substantial shifts toward autonomy the system maintained an imperial character.

The nationalizing effects of the First World War on the settler colonies, as well as the emergence of an independent Irish Free State under the guise of a Dominion, provoked a series of negotiations over the segments’ relations with the core during the 1920s. The principal issue concerned what we term ‘investiture’ (Mansergh Reference Mattern and Zarakol1952; McIntyre Reference Menon and Schain2009). Records of Imperial Conferences in the 1920s and 1930s are replete with lengthy discussions over seemingly recondite issues such as the divisibility of the Crown (would there be one Crown ruling several Dominions or several Crowns personified in one human body?). More concretely, the Dominions and the UK government negotiated over imperial defense and trade, including issues such as how much consultation the Dominions were entitled to on questions of the Empire’s relations with other powers. Ultimately, the question was whether the Dominions were fundamentally extensions of a larger whole or whether they were instead to be independent entities that invested the UK government to act on their behalf in certain matters. The Dominions increasingly (and increasingly effectively) demanded the latter interpretation and through successive agreements (including the Balfour Report and the Statute of Westminster) shifted the relationship between the United Kingdom and the Dominions to something resembling a confederal arrangement.