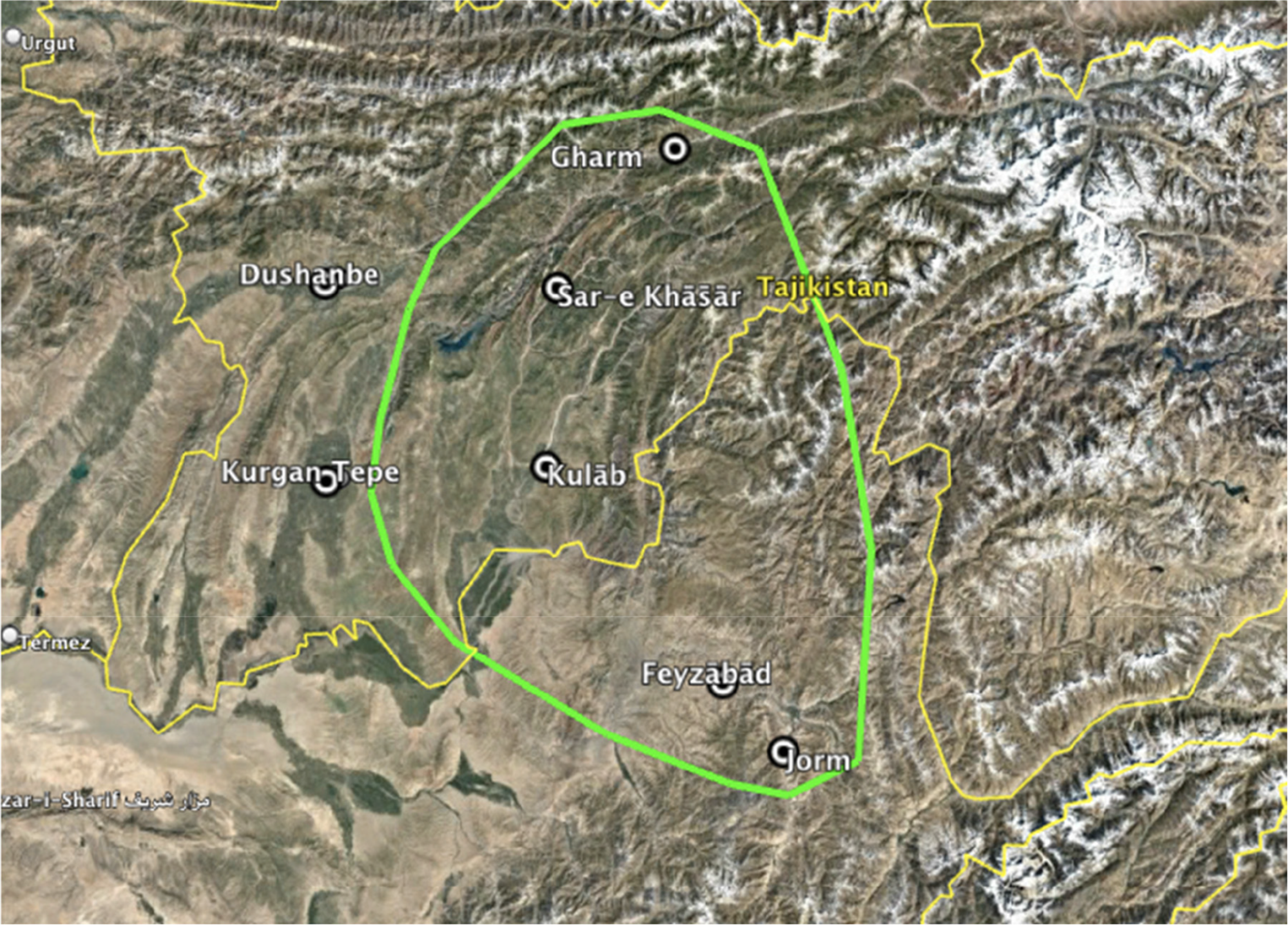

The epic Gurughli, popular among the Tajiks of the upper Oxus (Amu Darya), was derived from Turkic sometime in modern history and remained a dominant folk genre well into the second half of the 20th century. It was most popular in rural Gharm and Kulāb in central and southern Tajikistan, as well as in adjoining Badakhshān in northeastern Afghanistan (Figure 1). Tajik Gurughli (Гӯрӯғлӣ, Gū̆rūḡlī in Tajik orthography), literally translates as “son of the grave” (from Persian gōr “grave” and Turkic oğlu “son of”), is more commonly known as Gurghuli (Гӯрғӯлӣ, Gūrḡūlī), comprised of gōr “grave” and ḡul “giant” (whence English ghoul).Footnote 2

Figure 1. The geographic realm of Tajik Gurughli, which extends northward to the Zarafshān Valley, about which very little is known.

The Tajik Gurughli epic has likely been performed by rural bards since the late 18th century. Scholarly documentation of these performances began in the early 1930s, pioneered by Aleksandr N. Boldyrev and Iosif S. Braginskij. This documentation grew steadily until the 1960s, when it reached its most productive phase and Gurughli stories gained national fame in Soviet Tajikistan. At least fourteen variants were recorded, and several were transcribed, edited, and published in print. A compendium with Russian translation appeared in Gurugli: Tadžikskij narodnyj èpos, introduced and translated into Russian by I. S. Braginskij. Moscow: Nauka, 1987. The archives of the Rudaki Institute of Language and Literature at the Tajikistan Academy of Sciences are said to possess a rich audio collection of performances by various storytellers. The condition of these old audio tapes is unknown to me.

In Tajikistan, before the tradition of storytelling faded away, Gurughli singers were often itinerant, travelling from one settlement to another, to perform their repertoires. These performances were always accompanied by either the dotār or the dambura, long-necked lutes of the tanbur family. A typical recital would last several hours and was especially popular during the long winter nights, sometimes continuing until dawn for several nights in tandem until the bard's entire repertoire was exhausted. These performances took place in teahouses and, especially, during wedding or circumcision feasts upon invitation. The singer interacted with the audience and sang additional episodes when requested. On occasion, he would theatrically mimic the gestures and movements of heroes in battles. The art remained predominantly rural.

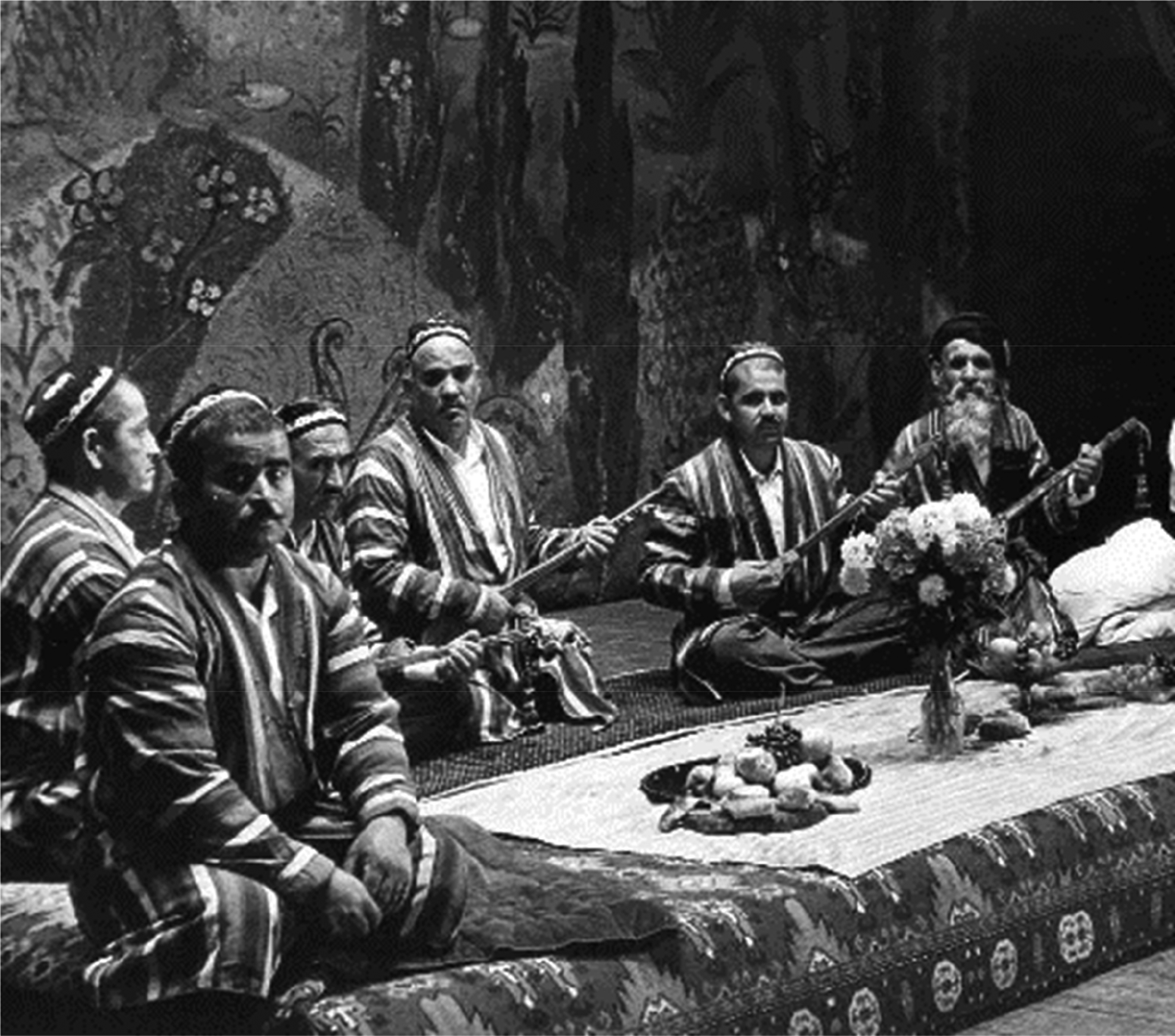

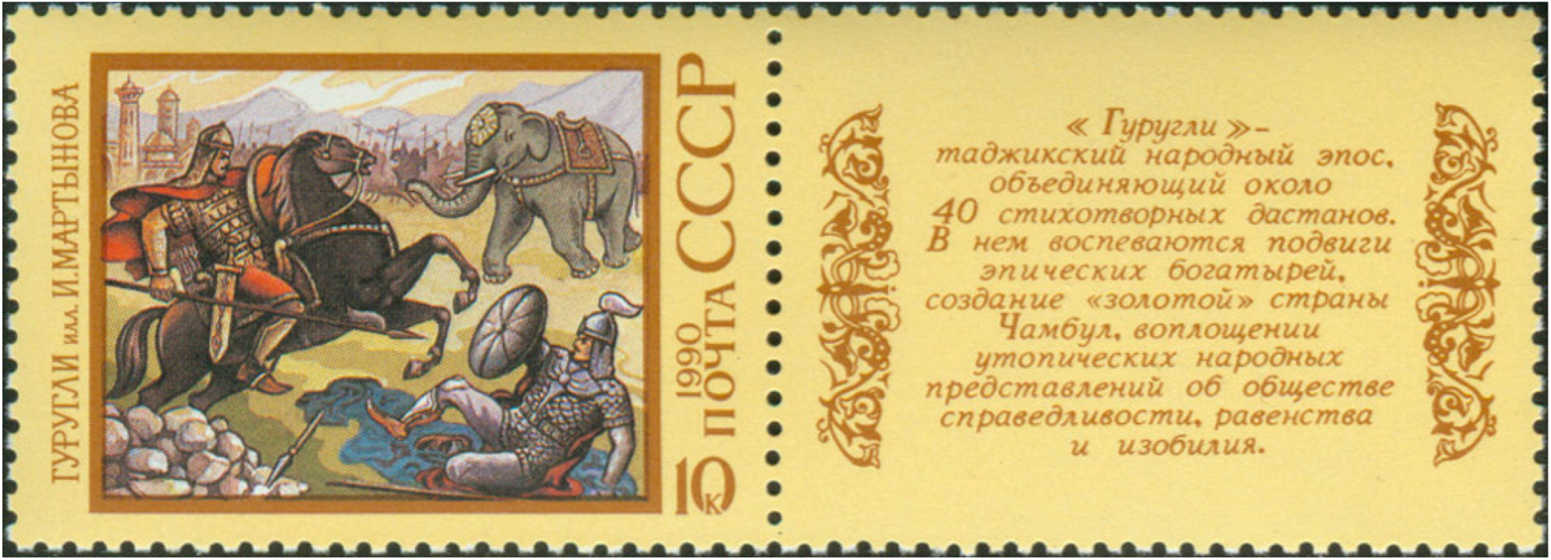

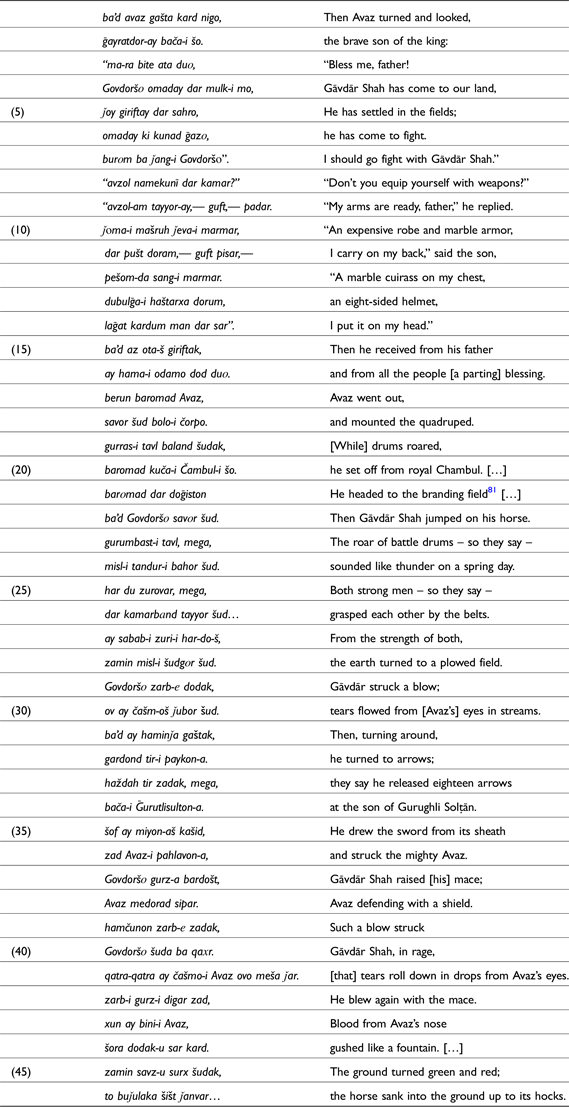

The expansion of mass media in Tajikistan brought Gurughli performances to the attention of urban dwellers, gradually leading to the art's recognition as a national treasure. Official recognition peaked at a nationwide recital competition (Festival-konkursi guruḡlixonhoi Toǰikiston) in Dushanbe in 1969, which featured seventy minstrels of various ages and origins dressed in stripped robes and quilted skullcaps (Figure 2). During this time, Radio Dushanbe had a weekly program dedicated to gūrūḡlī-xoni (Gurughli singing). Yet there is no evidence that the state ever became a patron of the bards or that Gurughli tales were adapted by modern preforming arts, as seen in the Azerbaijani opera Köroğlu, composed in 1932–36 by Üzeyir Hacıbäyli. In Tajikistan, the stories of the Shahnama had much higher national importance.

Figure 2. Gurughli performers, Dushanbe 1969.

Source: Intangible Cultural Heritage in Tajikistan. From left (identified by the author): Zarif Šarifov, Teša Niyozov (facing the camera), Qurbonalī Raǰab (or Burhon Xalilov?), Haqnazar Kabūd, Azizbek Ziyoef, and Hikmat Rizo.

Across the border in Afghanistan, Gurughli is poorly studied and remains largely obscure outside Badakhshān. There was some scholarly attention during the late 1960s and 1970s, when the country became a hub for Western hippies, Peace Corps volunteers, and anthropologists. Ethnomusicologists Hiromi Sakata and Mark Slobin studied Gurughli as a genre of Badakhshāni music, and certain cycles were summarized in standard Persian prose by ʿEnāyatollāh Shahrāni in the periodicals Fōlklōr and Lmar. During the same period, Soviet Tajik folklorists active in Afghanistan also published a piece from the Badakhshāni storyteller Ṣafar-Moḥammad (Reference Ṣafar-Moḥammad, Obidov and Fathulloev1972).

Performers

Gurughli reciters were semi-professional storyteller-musicians called gūrūḡlī-xon, gūrūḡlī-guy, or gūyanda. They were itinerant minstrels or bards (hofiz, ḥāfeż) who often performed other folk genres as well.Footnote 3 The narrators were typically peasants and artisans with little if any literacy, yet possessed with exceptional memories capable of retaining thousands of verses and captivating audiences for hours. Apprentices underwent rigorous training in vocal techniques, rhyming and improvisation skills, and musical harmonization. Novice bards enriched their repertoires through apprenticeships with master performers, accompanying them across different locales. Through these networks of mentorship, stories were orally transmitted, maintaining some level of consistency, at least over the half a century (1930s–1980s) of documentation in Tajikistan. However, variations emerged; for example, Hikmat Rizo and Haqnazar Kabūd stayed relatively faithful to their original teachings, whereas Qurbon J̌alil and Qurbonalī Rajab made significant alterations due to their poetic inclinations.

Major narrative inconsistencies and alternative scenarios often arise from diverse transmission lines and storytellers' individual tastes and creative impulses. Each bard developed a unique imagination, style, and repertoire distinct in both form and content. Improvisation played a significant role, as bards had no fixed texts. They learned the basic elements of a story, including its plot structure, main characters, setting, motivation, and ending, and then improvised events and scenes during performances to fill the gaps, drawing from many episodes in their memory. Consequently, Hikmat Rizo's telling of the same story varied substantially in different recordings, as analyzed by Braginskij. Rizo maintained the sequence and connections in each cycle, but each time the story varied in execution, artistic framing, length, and motivation. As Braginskij aptly noted, the Gurughli singer was not merely a narrator of someone else's text, he was a creator, an “original poet.”Footnote 4

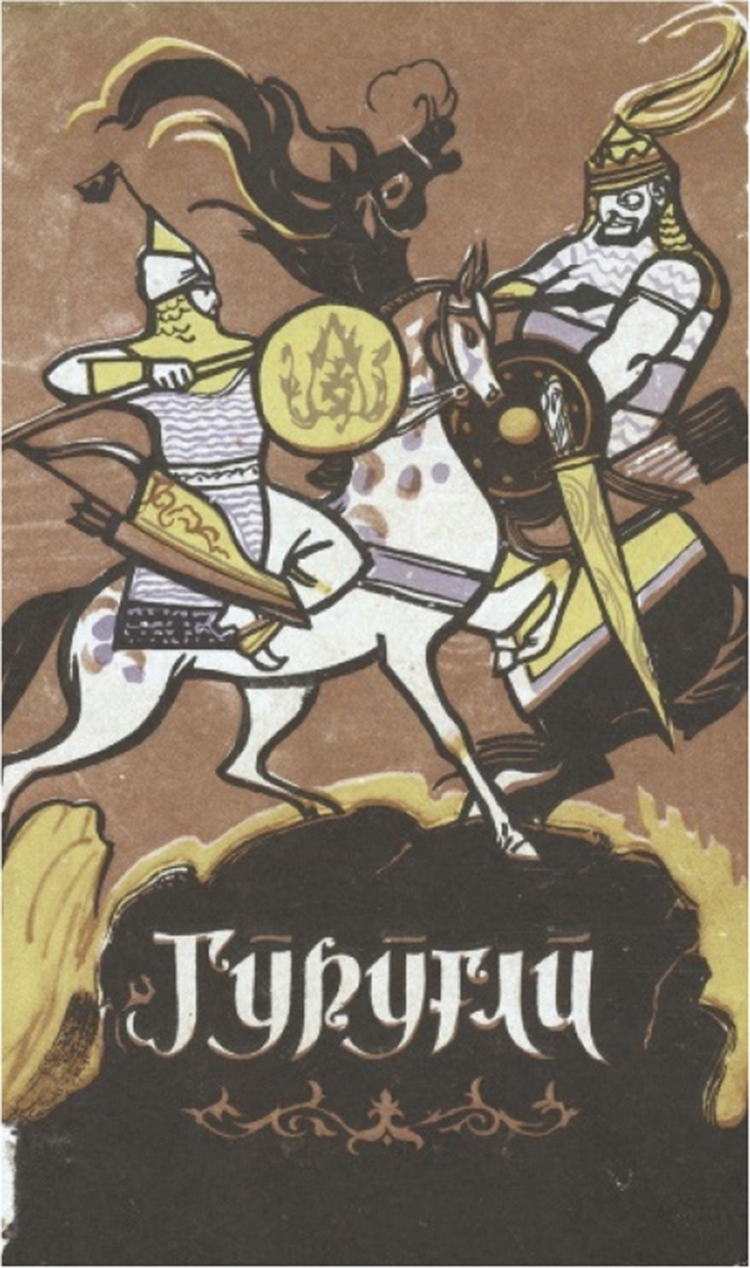

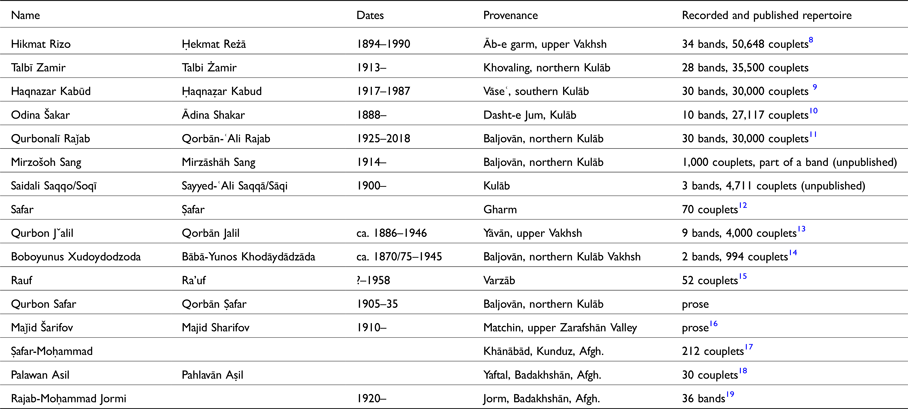

Most prominent bards of Tajikistan (Table 1) hailed from the southern province of Kulāb, with a nucleus in the mountainous valleys along the upper course of the rivers Qezelsu and Vakhsh.Footnote 5 A pioneer of the profession, Boboyunus Xudoydodzoda, is credited with passing on his Gurughli stories to twenty-five pupils, including Haqnazar Kabūd, Qurbonalī Raǰab, Sodiq Razzoq (Ṣādeq Razzāq), Mirzoali Hasanov (Mirzā-ʿAli Ḥasanov), and Karim Mahmadov.Footnote 6 The Rudaki Institute in Dushanbe houses the repertoires of Qurbon J̌alil, Xudoydodzoda, Hikmat Rizo, Odina Šakar (recorded in the 1940s), Qurbonalī Raǰab, Haqnazar Kabūd, and Talbi Zamir (recorded in the 1960s), among others.Footnote 7 As listed in Table 1, only a fraction of this recorded material has been transcribed and published (Figure 3). The civil war (1992–97) and collapse of Tajikistan's cultural institutions marked the end of traditional Gurughli performances, notwithstanding recent efforts to revitalize the tradition.

Figure 3. The front cover of Gūrūḡlī: Dostoni bahoduroni Čambuli maston, Vol. 1, 1962. Narrated by Qurbonalī Raǰab, transcribed by M. Xolov and Q. Hisomov, and edited by Q. Hisomov and R. Amonov, Dushanbe: Našriyoti davlatii Toǰikiston.

From historical Badakhshān, there are at least three documented singers: Ṣafar-Moḥammad, from Khānābād, in the present province of Kunduz, which borders Badakhshān province to the west; and Pahlavān Aṣil (Text 3) and Rajab-Moḥammad Jormi, from Upper Yaftal and Jorm respectively, along the upper Kokcha River, south of Faizabad, the capital of Badakhshān province. The Kolcha River flows north from the lofty Hindu Kush range, passing through the highland districts of Yamgān, Yaftal, and Jorm, which are situated only a few miles apart. No available study provides details on this secluded part of the world, where Naser Khosrow found refuge as a hermit in the last decades of his life.

Table 1. Performers and Documentation

Structure and performance

In the upper Oxus valleys, which serves as a focal point of Gurughli singers spanning Tajikistan and Afghanistan, these tales are invariably recounted in verse. In contrast, prose versions, like Uzbek versions, dominate the Zarafshān and Farghāna valleys of northern Tajikistan, where a Turko-Iranic symbiosis has shaped cultural expression for centuries.

Each mastersinger possessed a distinct repertoire, with up to fifty identified among various Tajik Gurughli bards.Footnote 20 A typical Gurughli repertoire consists of several “cycles,” known in Tajik as band or šoxa (shākha; analogous to Azerbaijani qowl or majles). A cycle is also referred to as doston (dāstān), signifying its broader reach in Central Asia folk literature. While each band stands independently, they are loosely interconnected within the broader repertoire.

A typical band consists of up to 2,000 couplets (beyts), delivered in full over eight to ten hours, though it can be condensed into three to four hours depending on the audience.Footnote 21 Each band is divided into episodes (bābs) marked by a new melody, poetic meter, and syllabic prosody, ending with the utterance hī… hī… hī… (Texts 3 and 5). To adjust the meter, syllabic elision and expansion are permitted, and the insertion of meaningless utterances is common (shown underlined in Text 3). Couplets are loosely rhymed, with predominant tale-rhyme -on/-ān, and an abundance of -or/-ār, -o/-ā, and -ar. These “easy” rhymes are attributed to the need for improvising a large number of verses.Footnote 22

The language of the performance, while Tajik, adopts a vernacular tone, particularly in the dialect of Kulāb.Footnote 23 But there is more: one can detect a kind of koine specific to local folk literature, characterized by recurring words and phrases such as the polysemic stem xam(b)-, “to get off or down, dismount, go, come, gather.”Footnote 24 Turkic words are paramount in the stories, especially in pastoralist contexts, reflecting a cross-language Sprachbund governing the region's oral literature. In the process of memorizing an enormous number of verses and improvising many more during a recital, the fluidity of pronunciation is prioritized over the soundness of expression to achieve a well-rounded performance. Formulaic similes and conventional expressions, typical of popular storytelling, punctuate all repertoires, with each bard incorporating personalized clichés throughout his performance.Footnote 25 Furthermore, literary Persian words and phrases, albeit modified and disregarding the prosodic meters of classical Persian, enrich the narration. Proverbs, parables, and lyrical songs further embellish the tale.Footnote 26

The singers typically employ a distinctive vocal style characterized by tense, guttural intonations, reminiscent of Altaic bakhshis of Inner Asia. To maintain the guttural voice, the singer drinks milk or takes ghee during breaks.Footnote 27 The musical accompaniment, broadly categorized as falak, aligns with the prevalent folk song style in the upper Oxus region.Footnote 28 Together, narration and music render a Gurughli performance an auditory experience, best appreciated through listening rather than silent reading. Consequently, published Gurughli cycles, while informative, lack the immersive impact of live performances, although familiar readers can still derive enjoyment from them.

The plot and theme

Summarizing the entirety of Tajik Gurughli cycles presents a challenge due to their varied number and content. Central to all versions is the frame-story set in the utopian city of Chambul, often referred to as Chambul-e Mastān, or the city of euphoric revelers, where heroes and beauties live in harmony. Ruled by Gurughli Solṭān (Shāh and Shāhanshāh in some versions), whose synthetic name Gūr-ūḡlī translates to “son of the grave,” due to his miraculous birth during his mother's burial (see Text 1), Chambul thrives under his just and wise leadership. Gurughli delights in the music, dance, and courtly ceremonies characterizing the blissful life in Chambul. However, Gurughli's prowess in battle often takes a backseat, with the defense of Chambul from external threats left to a group of warriors (bahādorān), mostly relatives of Gurughli.Footnote 29 The chief hero of Chambul is Avaz Khan/Shah, Gurughli's adopted or biological son in various renditions, who leads the knightly adventures, with his sons Nur-ʿAli and Shir-ʿAli (see Text 5) prominently featured. While these three generations mark the chronology of most repertoires, the great-grandsons Shirafkan and Ja(hā)ngir also join the rank of heroes in certain versions.

The antagonists, or sworn enemies (doshmanān) of Chambul, typically include foreign invaders, above all Reyḥān-ʿArab, but also Tork-e Baghlānshāh, Qaflānshāh (or Qatlānshāh), Ārmān, Landahur, and Torāb. Periodically, Chambul faces siege, sometimes aided by internal traitors, leading to its temporary fall and the capture of its heroes. Attacks and counterattacks, kidnappings and counter-kidnappings, trickery, and negotiations form the bulk of the plot. Ultimately, good triumphs over evil, Chambul is restored, and minstrels celebrate its heroes through their tambour performances. The narratives also feature comic characters such as Ḥasan Bahādor, whose origins trace back to folktales such as Kal Ḥasan and Divāna Ḥoseyni, according to Raǰab Amonov.Footnote 30

Women play significant roles in the stories. When not hunting or defending their homeland, heroes pursue beauties from distant lands. The sought-after girl is typically a princess or of noble birth, the fame of whose beauty has reached Chambul, or a fairy (parizād) imprisoned in the talisman of a demon (div). Seduction dynamics vary, initiated by either party. While heroes attract girls with their agility, strength, or flirtatious language, it is more often the woman who first reveals herself, luring the hero into a challenge to win her (as in Text 3). For instance, Gurughli's wife, Shirmāh, originally a parizād, entices the young champion into conquering her homeland and claiming her hand. In every case, elopement marks the culmination of the quest. The narratives are rich with descriptions of banquets and feasts where heroes are entertained by scores of graceful dancers and served by the master musician (sāqi), depicted in Texts 4 and 5. Hedonism pervades the tales of Chambul-e Mastān.Footnote 31

While the overarching theme pits good against evil, shades of gray are found in characters such as Gurughli himself, who transitions from a revered warrior in his youth to a vulnerable king.Footnote 32 In one version, Gurughli's decision to yield to Tork-e Baghlānshāh's demand to hand over his son Avaz Khan in chains highlights Gurughli's weakness – reminiscent of Goshtāsp, Esfandiār, and Rostam in the Shahnama.Footnote 33 There are other ambiguous characters with both good and evil features. Chambul leaders Aḥmad Khan and Yusof Khan, Gurughli's maternal uncles in certain cycles, are envious of Avaz Khan and occasionally go as far as colluding with the enemy. “Treason is implanted in their aristocratic blood,” according to the Soviet Tajik folklorist Raǰab Amonov.Footnote 34

Supernatural elements add vivid colors to the narrative. The very wives of Gurughli, Shirmāh and Aḡa-Yunos/Nus, who are conflated in some versions are fairies from the legendary Mount Qāf. Avaz possesses a winged steed. Characters transform into animals or plants such as doves, falcons, ducks, and even roses.Footnote 35 The bards skillfully invoke mythical creatures such as gāv-māhi, a mythical cow standing on the back of a giant fish and carrying the earth on its horns:

These elements enrich the narrative, weaving a tapestry of wonder and mysticism that aligns with the traditional lore and epic themes of Persian literature.

Geographical spaces in the Tajik Gurughli have largely gone unnoticed in scholarship. The Turkmen grasslands often serve as the backdrop for the local pastoralist economy (Text 1), betraying the borrowed nature of the stories. Within the repertoire of each bard, one finds scores and hundreds of toponyms, many of which are fictitious, though most are real. The selection of these toponyms is often random, sometimes disrupting the natural flow of the narrative (Text 2, line 21). Nonetheless, certain place names appear frequently, allowing for a rough cyclic pattern to be deduced from the texts: Turkestan (Text 3, lines 27, 33), apparently the greater Balkh region, along with Sistān, i.e., the Helmand basin, are encountered in introductory episodes.Footnote 37 Mount Qāf (Qafqāz, the Caucasus) is the abode of the fairy wife of Gurughli. His hero son, Avaz, who is highly ambulant and frequently engaged in military excursions, predominantly acts in Sistān. One of the many beauties Avaz seeks is the princess of Gholghola, a folk name given to archaeological ruins in both Sistān and Bāmiān. Avaz also undertakes a long quest to Zangebār to win the love of its princess. During the third generation of Chambul heroes, Yemen becomes a center of events, marking another far-reaching locality in the storytellers’ imaginations.Footnote 38 This rough sketch can be greatly refined in a future systematic study.

The stories in Tajik Gurughli are linear and open-ended, often lacking internal cohesion. Cycles and episodes are loosely strung together, with no flashbacks to previous events, creating a narrative flow that prioritizes action over introspection. The emotional depth is minimal; the characters’ inner lives are revealed solely through their actions rather than their thoughts, hopes, or worries. Romantic affairs, a staple of popular romances, frequently unfold without expressing the inner feelings of either party. This absence of psychological insight in Tajik Gurughli is not surprising, as it draws its expressive style from medieval literature,Footnote 39 contrasting with modern fiction, which delves deeply into characters' psyches.

From Köroğlu to Tajik Gūrūḡlī

The multiethnic Köroğlu/Gurughli tales have long drawn the attention of scholars of folk literature, particularly comparativists tracing the origins and transmission of epic cycles in a vast geographical expanse. The exact origins of the legend are obscure. What is certain is that the oral traditions developed in early modern times, based on historical events, among Turkish speakers of Azerbaijan, the Caucasus, and Anatolia, as Köroğlu (“son of the blind”), thence travelled eastward to Turkmen tribes, who call it Görogly (“son of grave”), and was eventually adopted by Uzbeks as Göroḡly and by Tajiks as Gūrūḡlī or Gūrḡūlī. There is also a consensus regarding major differences in form and content between western and eastern versions, which also differ in name: kōr “blind” versus gōr “grave,” both Persian words. The Caspian Sea serves as a rough boundary between these two groups.

Judith Wilks's seminal study compares three versions: Azerbaijani, Turkmen, and Tajik.Footnote 40 As a fundamental criterion distinguishing the versions of the stories, she focuses on the occupation of the hero Köroğlu, which transforms from a bandit in the Azerbaijani version to a kingly character in the Turkmen and Tajik versions. She suggests that the Turkmen version played a major role in the stories’ eastward transition by absorbing significant elements of the Persian epic tradition, while the Tajik version best reflects Persian influence.Footnote 41

Soviet scholars, examining literature through a class-based sociopolitical lens, identified the Tajik Gurughli as a reinterpretation of the story by a settled, feudal society, in contrast to the tribal Turkic context. Braginskij portrayed Chambul as an idealized, just, and orderly kingdom, favored by peasants.Footnote 42 Czech Iranist Jiří Cejpek, in his essay on Iranian folk literature, underscored the differences between the western and eastern versions, concluding that while Köroğlu's followers in the Azerbaijani version are adventurers rebelling against an unsympathetic society, the Uzbek and Tajik versions depict a feudal and unromantic entourage.Footnote 43

The relationship between the Uzbek and Tajik versions of the Gurughli epic is poorly studied. The Uzbek version, Göroḡly, shares its name and plot outline with the Tajik version: Chambul (from Azeri Çenlibel “misty slopes”) is the capital city; Gurughli is born in his mother's grave; he adopts Avaz, son of a butcher; the arch-enemy is Rayḥān-ʿArab; and there are repeating motifs of kidnapping women and stealing horses. Cejpek found little contrast between the Uzbek and Tajik versions, except that the latter is nearly exclusively in verse, in line with Persian epics.Footnote 44 However, other scholars have observed significant differences between the Turkic and Tajik versions. Folklorists Chadwick and Zhirmunsky highlight the unique characteristics of the Tajik Gurughli in both form and content, viewing it as a national creation of the Tajik people with only loose connections to the Turkic versions.Footnote 45 Wilks suggests that “in the creation of the Tajik version, the Uzbek influence hardly goes beyond providing the characters” names; it is much less important than the powerful influence of the Persian epic tradition in the region.”Footnote 46

The Uzbek Göroḡly was popular not only in Uzbekistan but also among the outlying Laqay tribe in the Kulāb province of Tajikistan.Footnote 47 There is a consensus that the Tajik villagers of highland Kulāb adopted the Gurughli from the semi-nomadic Uzbek Laqay, who established themselves in the region from the 18th century and are distributed in the southern plains of Kulāb.Footnote 48 However, an overlooked study by Marhabo Mirkamolova suggests that the process of acculturation may have been in the opposite direction. The Laqay version holds a unique position between the Uzbekistani and Tajik versions. First and foremost, Laqay Göroḡly is entirely in verse, suggesting its derivation from or assimilation with the Tajik version.Footnote 49 Even in later times, Laqay Göroḡly was further influenced by Tajik due to national radio and television broadcasting, and while the art was in the decline in Uzbekistan, it prospered among the Laqay.Footnote 50 In terms of performance practices, Mirkamolova finds that Laqay and Tajik practices were quite similar.Footnote 51 Regarding the stories’ form and content, she notes their general agreement but highlights certain differences, the most eye-catching being the central role of Gurughli in battles, even in old age, in the Laqay (and Uzbekistani) versions, as opposed to his minor heroic role in the Tajik version.Footnote 52

The Laqay version suggests that the differences between various ethnic renditions of Gurughli are less about ethnolinguistic distinctions and more about geographical distribution. This raises the question of why the Tajik Gurughli emerged in the upper Oxus region rather than in the Fergana Valley in northern Tajikistan, where the Uzbekization of Tajiks has been far more intense. A clue to this question might be found in Mark Slobin's seminal study on the ethnomusical traditions of Central Asia. Slobin divides the region into five broad Uzbek-Tajik musical zones, demonstrating that the upper Oxus area exhibits a high degree of acculturation between these two ethnic groups in terms of musical tradition.Footnote 53 Although Slobin does not discuss Tajik Gurughli in detail, it is plausible that a similar close correlation existed between Uzbeks and Tajiks regarding this specific musical genre.

All these observations notwithstanding, we remain in the dark about the exact relationship between the Laqay and Uzbekistani versions. How did the Tajiks acquire their Gurughli tales if not from the Laqay Uzbeks? Would it be too conjectural to propose this two-step scenario: first, Tajiks learned the art from the Laqay, and then the Laqay relearned it from Tajiks in verse form? Alternatively, did the Tajiks learn this oral tradition from Uzbeks living on the left banks of the Oxus? Is there a possibility that the Tajik version was initially acquired from the Turkmen nomads of Afghanistan and then spread across the Oxus into Kulāb? Are there such shared features between the Turkmen and Tajik versions that rule out the putative intermediary role of Uzbek? A rigorous comparative study among the Turkmen, Uzbek, and Tajik versions is needed to clarify these questions, though the language barrier makes this challenging.

The influence of Soviet ideology on the Gurughli stories published in Tajikistan has largely gone unnoticed in scholarship. Compared to the limited data available from Badakhshān in northern Afghanistan, the infrequency of religious elements in Soviet versions stands out.Footnote 54 This absence could have resulted from performers’ own self-censorship or editorial deletions in published texts.Footnote 55 Another notable difference is the sociopolitical overtone present in Soviet versions. Themes such as social justice, the toiling masses (xalqi kambaḡal), and oppressive kings were likely influenced by contemporaneous ideology.Footnote 56 The sample below is the concluding verse of an episode in which the singer alludes to Tajiks as a heroic people.

It may be concluded that Soviet society and culture imposed a superstratum on the dāstān genre, especially that of Gurughli in Tajikistan.

Persian elements

Even before reaching the Tajiks, the oral stories contained many Persian elements. In the Azerbaijani Köroğlu, to say the least, personal names such as Rowshan (Köroğlu's real name) and his wives Negār and Parizād are distinctly Persian compared to the future eastern versions. As the stories were transmitted, more Persian elements were absorbed into the eastern versions, as previously noted. This is unsurprising, as both the original Azerbaijani version and other Turkic versions developed within the Persianate literary domain, which stretched from Anatolia to India. Given the limited knowledge of interethnic developments, only the Tajik version can be commented on with certainty. It is only natural that the Tajik version, while retaining a nomadic pastural background, added recollections from the Persian literary past.

Researchers have identified numerous pre-existing subjects, images, characters, and motifs in classical Persian literature, with the Shahnama standing out as a significant source. The Shahnama serves as a crucial point of reference for two primary reasons: it is an early and influential work that has shaped many subsequent literary creations, and it is widely read by scholars.

A remarkable parallel is the archetypal father-son battle between Avaz and Nur-ʿAli, who do not recognize each other, which resembles the confrontation between Rostam and Sohrāb, although the Gurughli version lacks a tragic end. However, as Wilks points out, the presence of this motif in Gurughli may not be due to the Shahnama influence, although it very well could be, in light of other parallels.Footnote 58 This judgement can hold for other parallels as well, such as the fairy living in Mount Qāf who leaves Avaz a braid of her hair to burn when he is in trouble, akin to the Shahnama myth of Simorgh and Zāl. The battle between Zarrina (daughter of Soghdun Shah) and Avaz mirrors that of the heroine Gordāfarid and Sohrāb. The game of polo (chowgān) is replaced by bozkashi.

In the wobbly geography of the Gurughli tales, Zangebār evokes Zaranj/Sistān, the abode of the Sistāni cycle in the all-Iranian national epic.Footnote 59 Zangebār's arch-hero, Ruyin-tan, carries the epithet of the Shahnama's brazen-bodied Esfandiār, who dies in battle with Rostam in Sistān. Avaz Khan singing under the wall of the royal castle where the princess of Gholghola (near Sistān) resides recalls a well-known episode in the story of Zāl and Rudāba. Nur-ʿAli's adventurous quest to Yemen to kill a giant lion parallels Rostam's Seven Ordeals in his long campaign to slay the White Demon in Māzandarān, a mythical land sometimes associated with Yemen. Yemen also recalls Hāmāvarān during Kay Kāvus's reign in Iranian national history.

Many other parallels can be evoked from the Shahnama as well as Persian secondary epics and popular romances (see below), reflecting how folklore freely draws from formal literature. Specific similes include Simorgh, Div-e Sefid, Rakhsh, and of course Rostam:

However, these similes and metaphors are not as numerous as one might expect. In Gurughli repertoires, there is likely no mention of Sām, Zāl, Żaḥḥāk, Kāva, Fereydun, Sohrāb, Giv, Gudarz, Pashang, Bizhan, Manizha, Rudāba, Sudāba, Tahmina, and many others who would serve well as allegories. Is this because the Shahnama was not well known in rural Transoxiana or because the Tajik Gurughli, being relatively young, had not matured enough to draw in the old heroes of Persian literature?

A younger generation of Tajik academics continued to show interest in the study of Gurughli cycles, especially as classical Persian literature became more accessible in Tajikistan from the 1960s. Having examined Persian romance works, these academics drew parallel patterns with Tajik Gurughli, even if some of the motifs are universal rather than specifically Iranian. More concrete thematic similarities have been identified by Sobira Aminova, who likens Avaz Khan to Pahlavān ʿEvaż in ʿObeyd Zākāni's Resāla-ye delgoshāy and associates Gurughli with gheyb-zād (“hidden born”) in the 15th-century divān of ʿAbdollāh Hātefi Kharagerdi.Footnote 61 Fayzalī Murodov found gur-zād and pur-e gur in archaic Tajik folklore.Footnote 62

Position in Persian literature

The Tajik Gurughli is classified by Russian scholars as a “folk epic” (narodnyj èpos) or “oral epic” (ustnyj èpos) and by Tajik scholars as a “popular epic” (èposi xalqī), “heroic epic” (èposi qahramonī), or “tale of heroes” (dostoni bahoduron).Footnote 63 Indeed, heroic deeds constitute a good part of the Gurughli tales. Detailed accounts of numerous battles, including those involving heroines such as Zarrina and Qarakuz, reinforce the epic nature of these stories. The composition in verse, extensive length, and cyclic nature of the repertoires all align with the epic genre. However, there are challenges in this rigid classification; strictly speaking, the Gurughli story does not meet the criteria of Persian epics due to its lack of meter, formal language, discourse, and imagery, features outlined by William Hanway in his study of secondary Persian epics Garshāsp-nāma, Kush-nāma, Sām-nāma, and Borzu-nāma.Footnote 64 Judith Wilks posits that neither the western nor eastern groups of Köroğlu stories should be considered epics by conventional Western standards, but both should be viewed as dāstāns, a native term for long stories.Footnote 65

It may be more relevant to assess the Tajik Gurughli within the Persian popular romance genre, which generally evolved from the earlier epic genre. Hanaway, in another study, outlines the characteristics of the Persian romances Dārāb-nāma, Eskandar-nāma, Firuzshāh-nāmā, Qessa-ye Hamza, and Samak-e ʿayyār, all of which were originally transmitted orally before later being written down: “The Persian popular romances are heroic tales, focused on one individual and recounting his exploits both military and romantic.”Footnote 66 The Tajik Gurughli aligns closely with the formal characteristics and narrative elements of this genre, including the use of informal language to make the story accessible to a broader audience. There are also shared antagonist names such as Landahur, Qatlān, and Ashqar. Notably, female names in the Gurughli reflect the taste of the popular and formal romances of Nezami and Fakhroddin Asʿad Gorgāni. Examples include Shirmāh (Gurughli's wife),Footnote 67 Kherman-gol (Reyhān's daughter in Text 1 and Avaz's daughter in Text 5), Gol-āim (Avaz's mother as well as one of his wives), Qeymatgol-māh, Zarnegār-pari, Golbahār-pari (princesses of Sarandib),Footnote 68 Nownehāl (princess of Zangebār), and Golchehra (in Jomri's version). There is also a few Turkmen names such as Aḡa Yunos or Aḡanus (Gurughli's wife) and Qarakuz (Avaz's wife in Text 5).

While the Tajik Gurughli shares many features with Persian heroic and romantic traditions, it also possesses unique elements. The underlying herder society is evident in its pastoralism, nomadic camps, tents, shepherds, khans, begs, and frequent themes of horse racing (bozkashi), horse theft, and elopement, which are rare or absent in formal Persian literature.

Profound differences emerge in performance. Surviving Persian epic and romance literature is not only written but also orally transmitted. Until recently, professional storytellers – called naqqāls, shamāyel-gardāns, and Shāhnāma-kh wāns – moved from place to place, gathering crowds in streets, markets, and coffeehouses. However, two major differences in performance are notable: the urban audience of the naqqāls versus the rural setting of Gurughli bards, and the fact that while naqqāls told their stories in prose, Gurughli was performed in verse with musical accompaniment, which is otherwise nonexistent in contemporary Persian culture. The glottal voice used in performances, common among Altaic peoples, also sounds unfamiliar to Iranian-speaking rural and urban communities of the Iranian Plateau. While there were pre-Islamic bards called gōsāns, only their name has reached us. Tajik Gurughli performance is most comparable to those of Azerbaijani ashiqs who also sing Köroğlu, from which the Tajik Gurughli originates. In historical terms, the Turkification of Transoxiana is comparable to that of Azerbaijan since the early modern era.

Therefore, Tajik Gurughli does not fit neatly into any well-known Persianate tradition. It represents a distinctive form of folklore that thrived for a relatively short period in a remote fringe of the Plateau. This unique blend of heroic and romantic elements, combined with its pastoral and nomadic themes, sets it apart from the more urban and prose-centered Persian popular traditions.

Going beyond Persian, I cannot help but draw a brief comparison between the Tajik Gurughli and the Ossetic Nart epic, another Iranian literary tradition with which I am currently engaged. There are numerous parallels between the two oral traditions, including a cyclic structure with three generations of heroes acting within a pastoralist economy, as well as certain aspects in themes, narrative structures, and cultural contexts. However, what makes the Nart saga enduring is its roots in Ossetic culture. The Narts are deeply embedded in Scytho-Alanic Iranian mythology and reflect the social structure of prehistoric Indo-European society. This deep cultural connection has kept the Narts very much alive among the Ossetians, who associate the stories and heroes with local monuments and cherish this literary tradition by creating sculptures, cartoons, and animations of the stories. In contrast, the Tajik Gurughli, despite its rich narrative, had a relatively short lifespan and has now almost fallen into oblivion. Unlike the Nart saga, the Gurughli epic lacks the same depth of cultural integration and contemporary representation, contributing to its decline in prominence.

Biography of a bard

Perhaps the most prominent minstrel of the Gurughli cycles is Qurbonalī Raǰab.Footnote 69 Born in 1925, he attended school up to the fifth grade in his native village of Pārvār, located in the highland district of Sar-e Khāsār on the northern fringes of Tajikistan's Kulāb province. In his youth, Qurbonalī experienced a typical life as a Soviet Tajik villager, working as a farmer in the kolkhoz until he was drafted into World War II. After spending twenty-two days on the front lines, his right hand was wounded and he was allowed to return to his village. In 1949, following the Soviet policy of forced migration, the inhabitants of Pārvār and neighboring villages were relocated to the cotton collective farms in the Vakhsh basin of Kurgan Tepe province.Footnote 70 Qurbonalī eventually managed to free himself from kolkhoz duties and settled in the town of Kulāb, where he earned a living as a musician. Despite his official Soviet surname, Raǰabov, he remained known as Qurbonalī Raǰab in Tajikistan's artistic and literary circles.

Sar-e Khāsār was a stronghold of Gurughli singers, and Qurbonalī was exposed to the art from an early age. He acquired singing and rhyming abilities from his mother, Jānāna, a hofiz (“singer”) who performed regularly in female circles. An impressive event in his artistic life was a Gurughli performance by the eminent minstrel Xudoydodzoda at a wedding ceremony in Pārvār. This inspired novice Qurbonalī to memorize two Gurughli bands and excel in improvisation with his dotār (Figure 5). To become a professional bard required great effort, and Qurbonalī further enriched his repertoire by apprenticing under other senior bards, Šarifi Šex, Šerali Alimov, Murodi Sang, Mahmarasul Šarif, and Haqnzar Kabūd. Through these internships, Qurbonalī developed his own characteristic style. He had a keen appetite for composing verses, which allowed his repertoire to evolve significantly beyond what he learned from his masters. During his professional career, Qurbonalī would often commemorate his teachers by informing his audience of the master who taught him the cycle he was performing that night.Footnote 71 Qurbonalī held the highest regard for Xudoydodzoda, Šukurmast (Shokurmast), and Haqnazar Xol (Kholov).

Figure 4. USSR postal stamp, 1990 (illustrated by I. Martynova), devoted to Gurughli: “The Tajik national epic verse brings together some 40 works. In it are exploits of epic heroes, the establishment of the ‘golden’ land Chambul, personification of national utopian ideas about society, justice, and abundance.”

Figure 5. Qurbonalī Raǰab. Courtesy of Yusufī, “Dostoni umri gurughlisaro.”

In a 1950 expedition to Pārvār, the Tajik folklorist Raǰab Amonov recorded samples of Qurbonalī's repertoire. Ten years later, the singer traveled to Dushanbe at the invitation of the Tajikistan Academy of Sciences, where eighteen cycles (bands or dāstāns) of his Gurughli repertoire were documented, totaling approximately 30,000 couplets or 60,000 lines. Of these, twelve cycles were transcribed in Cyrillic Tajik by Xolov and Hisomov and published under Amonov's supervision as Gūrūḡlī: Dostoni bahoduroni Čambuli maston in two volumes, with a special edition for the blind.Footnote 72 This publication ranks Qurbonalī as the most published Tajik Gurughli singer. The length of the published cycles varies between 360–1,940 couplets (with an average of 1,130 couplets per cycle), totaling 13,500 couplets in my calculation. Possessing an enormous wealth of orally transmitted folk literature, Qurbonalī Raǰab ranked second, after Hikmat Rizo, senior by age, among seventy minstrels who performed in a national recital competition in Dushanbe in 1969.

Although Qurbonalī's heritage is his precious Gurughli repertoire, he was a masterful singer of other epic dāstāns, folkloric quatrains, and ghazals. He composed many folk poems, mostly comic and satirical (hajv) about interesting events he witnessed. He also showed an interest in rhyming pieces meshed with Soviet ideology; for instance, he wrote Šūriši Vose’ (Shuresh-e Vāseʿ), in the epic genre of dāstān, to pay homage to the glorified peasant riot against the Amir of Bukhara.Footnote 73 Thus, one must weigh the extent to which Qurbonalī's published Gurughli repertoire was influenced by Soviet dogma. His work was published in the local periodical Haqiqati Kūlob, various collections, or separately: Taronai dil (Tarāna-ye del; 1976), Surūdi zamin (Sorud-e zamin, 1982), Šaršara: Maǰmūi še'ru dostonho (Majmuʿ-e sheʿr o dāstānhā, 1986), Fayzi zamin (Feyż-e zamin, with Sattor Šokirzoda, 1991), Dili firorī (Del-e farāri, with Odian Mirak, 1996).Footnote 74 Despite his pro-Soviet works, Qurbonalī was not as decorated with medals as one might expect. He pursued his profession in his later years (Figure 5), long after the heyday of gūrūḡlī-xoni had passed. He died on October 10, 2018, in the city of Kulāb at the age of ninety-three.

Conclusion

Our understanding of the Tajik Gurughli owes much to its documentation during the Soviet era in Tajikistan. Without the intervention of Russian scholars, we might know as little about the Tajik Gurughli as we do about its counterpart on the Afghan side of the Oxus, which received only minimal study when on the verge of extinction. Comprehensive recording, written documentation, and scholarly research on the Gurughli only began in the 1930s. Consequently, the full scope of the Gurughli epic and its various cycles remains uncertain. It is likely that some versions have already been lost to history in the non-literate society that originally produced these tales. This situation may be reflective of other local genres within the Persian cultural domain that have similarly been buried in history without leaving substantial traces.

While Tajik and Russian publications are crucial to our understanding, only a portion of the collected Tajik repertoires has been published in print (see Table 1). To my knowledge, also very few audio recordings have been released. Scholarly attention was concentrated during Tajikistan's prosperous half-century period from the 1930s to the 1980s, but the outbreak of civil war (1992–97) in independent Tajikistan abruptly halted scholarly interest; an interest not yet revived with the same enthusiasm or rigor as in the Soviet era.

Performance of the Gurughli epic, originally rooted in the Kulāb province, was popularized through radio broadcasts and evolved into a national art form in Tajikistan. However, the civil war and subsequent collapse of the nation's cultural institutions led to a sudden decline in the art's prominence. Ever since, the Gurughli epic has fallen into obscurity, with little hope for its revival or preservation in the near future.

Sample Texts

The excerpts below are from the renowned Kulābi bards Qurbon J̌alil (Text 1), Xudoydodzoda (Text 2), Qurbonalī Raǰab (Texts 4 and 5), and Badakhshāni singer Pahlavān Aṣil (Text 3). These excerpts include key motifs of the Gurughli tales: the miraculous birth of Gurughli, the future king of Chambul; the heroic deeds of the arch-hero Avaz Khan; his elopements with noble girls; and vivid descriptions of Chambul during its prosperous and joyous times.

The texts’ transcriptions differ significantly. Text 3 is my direct transcription from the available audiotape, while other texts are Roman transliterations of published Cyrillic Tajik texts, with hyphens added to mark essential morphemes for ease of reading. These published texts are not precise transcriptions of audio recordings: Kulābi-specific sounds, such as ı and w, are normalized into standard Tajik phonology, and some contractions and elisions are repaired to make the texts accessible to the general Tajik reader. The texts have been abridged by the editors using ellipses and further shortened by me using brackets “[…].”

Text 1. The birth of GurughliFootnote 75

Qurbon J̌alil was born in the village Khochak, in the district of Yāvān on the upper Vakhsh Valley, in Qurgan Tepe. In the 1920s, he worked as a laborer in Samarkand, Bukhara, and Qoqand. He worked in the kolkhoz from 1935 and became a folk singer, standing out as one of the earliest published Gurughli singers (see Table 1), published in the early 1940s and in Gurugli: Tadžikskij narodnyj èpos in 1987. Other works of his include Kūli Hasan, Čaman, and Gašti namoyon on the themes of social progress. Details of his biography remain scarce.Footnote 76 Sources vary on his birth, ranging from 1870 to 1886, and his death is similarly recorded between 1946 and 1957.

The following selected excerpts are from the introductory episode titled “Dostoni Rayhonarab podšoh, az modar omadani Gūrūḡlī ba dunyo, va bino mondani Čambuli Maston.” This episode introduces two pivotal characters with significant roles throughout future cycles. It features the formidable King Reyḥān-ʿArab, later an enemy of Chambul, and Aḥmad Khan, a Turkmen tribal chieftain who rises to prominence after his nephew, Gurughli, founds the city of Chambul.

Reyḥān learns about Helāl, Aḥmad Khan's beautiful sister, and demands her hand in marriage. Aḥmad, unable to resist, agrees with much hesitation and requests a high bride price, which the king fulfills. An elaborate wedding ceremony is arranged, but Helāl, unhappy with the arrangement, flees into the desert, where she gives birth and subsequently dies. Aḥmad then marries his daughter to Reyḥān.

Aḥmad Khan owns a mare gifted to him by Reyḥān. One day, while grazing, the mare's hoof sinks into a grave, revealing a newborn orphan. The mare nurses the baby briefly. Herders report the situation to Aḥmad Khan, who brings the baby to his pavilion and hosts a banquet. An elder, chosen by the guests, names the child Gurughli, recognizing that the baby was found in Aḥmad Khan's sister's grave.

A notable variation between the Kulābi and Badakhshāni versions of the tale lies in the explanation of Helāl's pregnancy. In Qurbon J̌alil's published narration, Helāl's pregnancy remains unexplained (lines 55–61 below). According to Rajab Moḥammad Jormi's Badakhshāni narrative, Māh-e Helāl, sister of Aḥmad Khan, is sitting by his castle door when a passing pir (holy man) causes her to become pregnant with just a look. Fearing her brother's wrath, she prays for death and later gives birth in her grave to Gurughli, who is nourished daily by a horse on divine instruction.Footnote 77

Text 2. The battle of Avaz with GāvdārFootnote 79

This excerpt is from the episode titled “J̌angi Avaz bo pahlavoni Salmon Podšoh — Govdoršoh.” The singer Xudoydodzoda stands out among Gurughli bards as a master of narrating heroic battles, clearly influenced by the conventional battle descriptions in Persian literature: a full portrayal of the hero's horse and armor, the beating of drums, and a detailed account of the single combat.Footnote 80

The young Avaz, Gurughli's son, prepares for battle with the daring Gāvdār Shah, who has encroached on the grazing lands of Chambul. Receiving his father's blessing and the people's support, Avaz dons his armor and rides out, accompanied by the roar of drums. Encountering eighty fighters, he boldly confronts them, dismissing their taunts and demands a match. Avaz asserts his identity and strength, promising to defeat Gāvdār Shah without resorting to gifts or tricks.

In the ensuing battle, Avaz and Gāvdār clash with enormous force, shaking the earth with their might. Avaz remains resilient, defending against the challenger's powerful blows. Ultimately, Avaz's skill and strength prevail. Admiring his valor, Gāvdār acknowledges defeat and offers to ally with the heroes of Chambul. Avaz accepts.

Text 3. Avaz meeting Khāl PariFootnote 82

The singer of this episode, Pahlavān Aṣil, whose biography and other songs are unknown to me, was reportedly from the Yaftal settlement of “Surun,” a place I have been unable to identify.

The text transcription is from an audio recording, with filler sounds underlined. Some words in this text are obscure to me, as the vanishing Persian dialects of the Kokcha Valley in Badakhshān have yet to be studied.

The episode starts with a quatrain (chārbeyti) in the form of a classical Persian robāʿi; singing a didactic prelude is typical in Gurughli stories.Footnote 83 This episode of an unknown cycle depicts an elopement with erotic overtones. The champion, Avaz Khan, son of Gurughli (here Gōrḡoli), rides his horse Qir into the market at night. He sees a slender coquette sitting alone in a shop. Struck by her beauty, he learns she is Khāl Pari, sister of Aḥmad Khan and daughter of the vizier of “Turkestan.” Avaz approaches her, praises her beauty, and questions her solitary presence. Khāl Pari, who has been waiting for him, greets him. Avaz Khan lifts her onto his horse and they ride off to the Turkmen bazaar.

Text 4. The utopian city of ChambulFootnote 85

The master-bard Qurbonalī Raǰab possessed a rare talent for depicting banquets and ceremonies, where dance and music flourished, and the joys of eating and drinking were celebrated in a utopian city devoid of illness, crime, cruelty, and all that makes life miserable. In this episode, he glorifies idyllic Chambul, with its verdant fields and blooming gardens on a radiant day. Numerous beauties grace the scene as the festivities commence at dawn. Avaz sits on the throne, accompanied by his great uncle Aḥmad Khan. Always present at Chambul ceremonial events is the court musician Sāqi Baba, a title that also applies to the storytelling bard himself. This shared title encourages the audience to envision the bard within the story, thereby enhancing the vividness of the recited narrative. Note textual clichés, such as line 6 in this text with line 7 of Text 5.

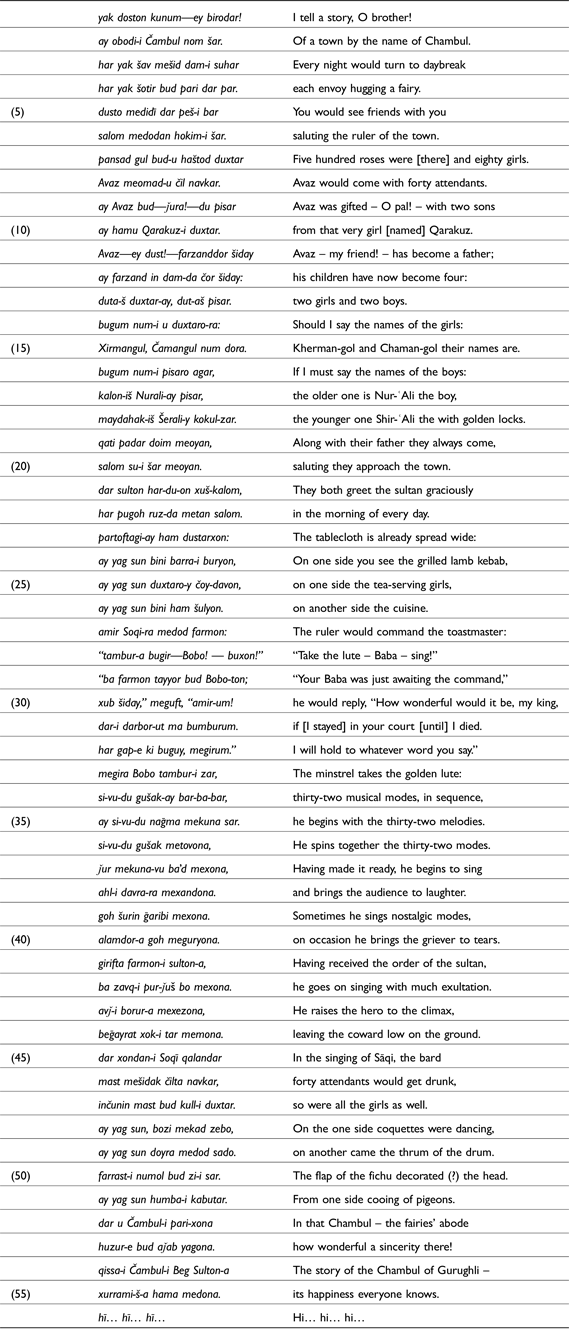

Text 5. A musical festivityFootnote 87

This episode narrates a royal reception in Chambul, a town where night seamlessly turns to daybreak, with envoys embracing fairies and friends saluting the town's ruler. The arch-hero of Chambul, Avaz Khan, arrives with forty attendants, all graciously greeting his father, Gurughli the king. Avaz and his heroine wife, Qarakuz, the princess of Sarandib, now have two sons, Nur-ʿAli and Shir-ʿAli, and two daughters, Kherman-gol and Chaman-gol. The tablecloth is spread wide with grilled lamb kebab, tea-serving girls, and various cuisines. The ruler commands the master of ceremonies, Sāqi Baba, to sing. Joyfully, Sāqi plays the golden lute with thirty-two musical modes, entertaining the audience by making them laugh and cry. The tambur, joined by drums, intoxicates the attendants, while dancers move and pigeons coo. Chambul, a fairies' abode, is renowned for its happiness and sincerity.

Acknowledgement

In translating the texts, I benefited from the guidance of the late Bukharan poet Asad Gulzoda Bukhoroi (1935–2023). I am indebted to Professor Lois Beck for her invaluable comments on this paper. I am grateful of Professor Stephen Blum of the CUNY Graduate Center music department for generously sharing Gurughli recordings from Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Special thanks to Dr. Wolfgang Holzwarth for sharing the material on the Laqay version of Gurughli. Extensive comments by one of the anonymous reviewers significantly improved the quality of this paper.