INTRODUCTION

The potential impact of a changed climate on crop production has become an important issue (Ceccarelli et al. Reference Ceccarelli, Grando, Maatougui, Michael, Slash, Haghparast, Rahmanian, Taheri, Al-Yassin, Benbelkacem, Labdi, Mimoun and Nachit2010; Eitzinger et al. Reference Eitzinger, Orlandini, Stefanski and Naylor2010; Calanca et al. Reference Calanca, Bolius, Weigel and Liniger2011), although there are other challenges (Barnes et al. Reference Barnes, Wreford, Butterworth, Semenov, Moran, Evans and Fitt2010) such as the need to use food more efficiently through reducing post-harvest losses in the food chain (Hodges et al. Reference Hodges, Buzby and Bennett2011). Insect pests, plant pathogens and weeds (hereafter collectively termed ‘pests’) represent a major constraint to crop production (Oerke Reference Oerke2006), and the incidence and effects of pests are driven to a large extent by weather conditions and the climate. Thus, pests play a key role in the potential impacts of long-term climate change on crop productivity. However, assessments of climate change effects on crops have focused on potential impacts on yields. Yield limiting factors such as pests have been neglected in most of these studies and therefore there is a risk that future crop yields might be overestimated if compromising effects from pests are ignored (Gregory et al. Reference Gregory, Johnson, Newton and Ingram2009). In general, the interactions between crops and pests, their respective natural enemies and competitors are complex and poorly understood in the context of climate change (Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Macfadyen and Hoffmann2010). Another concern is how climate change might affect the synchrony among species that provide benefits to crop plants, such as timing of spring bloom and arrival of insect pollinators (Wolfe et al. Reference Wolfe, Ziska, Petzoldt, Seaman, Chase and Hayhoe2008), or the presence and activity of beneficial antagonists of crop pests (Klapwijk et al. Reference Klapwijk, Gröbler, Ward, Wheeler and Lewis2010); although the regulation of pests by natural enemies is often unnoticed by humans (Gutierrez et al. Reference Gutierrez, Ponti, d'Oultremont and Ellis2008).

Depending on future emission scenarios, atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration might increase from the current global concentration of c. 390 ppm to between 500 ppm (A1B emission scenario according to The Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES; Watson Reference Watson2001)) and 1000 ppm CO2 (the A1FI emission scenario) at the end of the 21st century (Sanderson et al. Reference Sanderson, O'Neill, Kiehl, Meehl, Knutti and Washington2011). The projected average global warming of surface air at the end of the 21st century relative to 1980–99 is dependent on the emission scenarios and climate models used, among many more factors (Knutti et al. Reference Knutti, Allen, Friedlingstein, Gregory, Hegerl, Meehl, Meinshausen, Murphy, Plattner, Raper, Stocker, Stott, Teng and Wigley2008). For example, a global temperature increase of c. 1·1–3·5°C, until the end of the 21st century was projected by Meehl et al. (Reference Meehl, Washington, Collins, Arblaster, Hu, Buja, Strand and Teng2005). However, all climatic and atmospheric projections that exist at present include significant uncertainties. Future changes in cloud development and distribution are the single largest source of uncertainty in climate projections (Karl & Trenberth Reference Karl and Trenberth2003), suggesting that it will be very difficult to project future precipitation patterns on a regional and local scale. Frost days and snow cover are likely to decrease, because warming promotes rain rather than snow (Karl & Trenberth Reference Karl and Trenberth2003). One of the major concerns with potential climate change is that the frequency of extreme weather and climate events may increase, including heat and cold waves, droughts, heavy precipitation, flooding and storms (Easterling et al. Reference Easterling, Meehl, Parmesan, Changnon, Karl and Mearns2000); however, these projections on a regional and local scale are even more uncertain than those of future precipitation patterns.

Ecological responses to recent climate change are already visible and are mainly associated with a temperature increase of c. 0·5–1·0°C during the past few decades in certain parts of the world (Walther et al. Reference Walther, Post, Convey, Menzel, Parmesan, Beebee, Fromentin, Hoegh-Guldberg and Bairlein2002; Hulle et al. Reference Hulle, Coeur d'Acier, Bankhead-Dronnet and Harrington2010). For example, warmer mean air temperatures in Germany, especially since the end of the 1980s, have led to the advancement of phenological phases of the natural vegetation, fruit trees (earlier beginning of blossoming) and field crops (earlier beginning of stem elongation), particularly in early spring (Chmielewski et al. Reference Chmielewski, Müller and Bruns2004). Therefore, in the present review, most examples are related to potential effects of temperature on pests; although the interactions with precipitation/humidity and CO2 atmospheric content are also considered.

Increasing temperature is a climate change factor that affects, for example, length of the growing season, seasonal temperature patterns, snow cover duration, frost severity and frequency, minimum and maximum day- and night-time temperatures, and extreme weather events. For example, in regions with a temperate climate, where the seasonal variation of temperature is often large, development typically starts slowly in early spring, progresses more rapidly as the season advances, and may be temporarily suspended in the heat of midsummer (Drake Reference Drake1994). Changes in both mean temperature and its variability are equally important in predicting the potential impact of warming on pests (Scherm & van Bruggen Reference Scherm and van Bruggen1994). Minimum and maximum temperature extremes can be particularly important (Seem et al. Reference Seem, Magarey, Zack and Russo2000; Sinclair et al. Reference Sinclair, Vernon, Klok and Chown2003; Terblanche et al. Reference Terblanche, Hoffmann, Mitchell, Rako, le Roux and Chown2011). During colder periods of the year, warming may relieve plant stress, whereas during hotter seasons stress may increase. This will certainly also affect plant–pest relationships, although the final outcome is difficult to predict due to complex interactions that may exist (Garrett et al. Reference Garrett, Dendy, Frank, Rouse and Travers2006).

At a given location, a shift in warming and other climate and atmospheric conditions may result in direct and indirect (e.g. mediated through the host plant) effects on insect, pathogen and weed species, changing several of their characteristics. Possible changes include (1) geographical distribution (e.g. range expansion or retreat, and increased risk of pest invasion, finally influencing species composition and most ecosystem processes and services), (2) seasonal phenology (e.g. start of spring activity, synchronization of pest life-cycle events with their host plants and natural enemies) and (3) population dynamics (e.g. over-wintering and survival; changes in population growth rates, changes in the number of generations of polycyclic species) (e.g. Coakley Reference Coakley1988; Patterson & Flint Reference Patterson, Flint, Kimball, Rosenberg and Allen1990; Porter et al. Reference Porter, Parry and Carter1991; Harrington & Stork Reference Harrington and Stork1995; Morimoto et al. Reference Morimoto, Imura and Kiura1998; Runion Reference Runion2003; Harrington et al. Reference Harrington, Clark, Welham, Verrier, Denholm, Hulle, Maurice, Rounsevell and Cocu2007; Thuiller et al. Reference Thuiller, Richardson, Midgley and Nentwig2007; Tiedemann & Ulber Reference Tiedemann, Ulber, von Tiedemann, Heitefuss and Feldmann2008; Legreve & Duveiller Reference Legreve, Duveiller and Reynolds2010; Ziska & Dukes Reference Ziska and Dukes2011; Edler & Steinmann Reference Edler and Steinmann2012; Pautasso et al. Reference Pautasso, Döring, Garbelotto, Pellis and Jeger2012; Peters & Gerowitt Reference Peters and Gerowitt2012; Siebold & Tiedemann Reference Siebold and Tiedemann2012; West et al. Reference West, Holdgate, Townsend, Edwards, Jennings and Fitt2012a,Reference West, Townsend, Stevens and Fittb). For insects, less intensively investigated and therefore least understood are the potential effects of changing climate on population dynamics, compared to the likely effects on phenology and range shifts (Rodenhouse et al. Reference Rodenhouse, Christenson, Parry and Green2009). This may also be true for plant pathogens and weeds: Dukes (Reference Dukes and Richardson2011) reported that the potential future distribution of species was particularly investigated by researchers.

The tremendous increase of publications on climate change biology (Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, Menon and Li2010) forces researchers to continuously catch up on climate change biology literature. There is a strong need to develop appropriate working frameworks, for example, to guide the planning and prioritization of research related to crop pests. The present overview provides background information on climate change biology research including (1) research approaches, (2) challenges, (3) appropriate model species and study locations, (4) a summary of previously published review articles, (5) research gaps, (6) selected examples of recent key studies, and finally presents information on (7) theoretical frameworks to guide climate change research concepts. The literature survey started on 1 April 2009 and ended 24 January 2012. During this time period the literature databases Web of Knowledge and Google scholar were visited each month and the following key words and phrases were entered: ‘climate change and insect pest’, ‘climate change and insect’, ‘climate change and plant pathogen’, ‘climate change and plant disease’, ‘climate change and weed’ and ‘climate change and invasive plant’. The records retrieved were screened for their relevance, and more references were often found in the relevant review articles and original research articles. Nevertheless, it is possible that some important studies are missing. Many more articles could be found related to temperate climatic conditions compared to subtropical and tropical conditions (see also below). Therefore, more examples in the present review are related to temperate climatic conditions. This is also true for insects and fungal pathogens, which are investigated more often compared to weeds and plant bacteria and viruses. The focus of the literature search was on agriculture; however, as interdependencies between various plant ecosystems exist, several articles on pests and other species (e.g. beneficial and/or with no known economic effect) in horticulture, forestry and unmanaged plant ecosystems were also included in order to establish an interdisciplinary approach in the present review, which contributes to knowledge exchange across disciplines.

APPROACHES IN CLIMATE CHANGE BIOLOGY RESEARCH

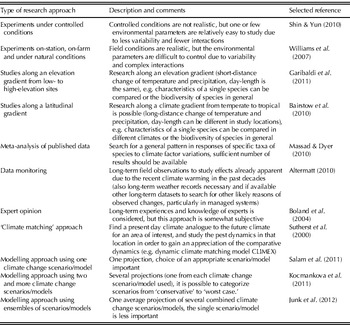

Climate change biology research approaches (Table 1) include in general (1) experimental work that deals with one or few weather parameters or atmospheric constituents in controlled or field conditions, (2) ‘theoretical’ research approaches such as meta-analysis of published results and analysis of various long-term datasets, (3) expert opinion and (4) generation of models that predict how projected changes in climate and/or atmospheric composition will alter distribution, prevalence, severity and management of pests and other organisms (Sutherland Reference Sutherland2006; Chakraborty et al. Reference Chakraborty, Luck, Hollaway, Freeman, Norton, Garrett, Percy, Hopkins, Davis and Karnosky2008).

Table 1. Examples of experimental and theoretical approaches in climate change biology research

The selected references were subjectively chosen.

For example, one approach includes research along an elevation gradient from low to high elevation sites (Garibaldi et al. Reference Garibaldi, Kitzberger and Chaneton2011). There are also research attempts in different habitats along a latitudinal gradient (e.g. c. 1000 km long) which includes, for example, subtropical, temperate and semi-arid climatic conditions (Bairstow et al. Reference Bairstow, Clarke, McGeoch and Andrew2010). In Europe, Glemnitz et al. (Reference Glemnitz, Radics, Hoffmann and Czimber2006) studied the land use impact on the weed flora along a climate gradient from southern Italy to Finland and found that in general weed species richness is greater in the south than in the north of Europe. Such studies can help to identify if a certain species is limited to a specific climate or if it is widely occurring and may invade locations which are getting warmer.

Meta-analyses of published datasets have been performed to search for a general pattern in responses of specific taxa of pests to climate factor variations (Massad & Dyer Reference Massad and Dyer2010). In addition, long-term datasets from field observations have been used to study effects already apparent due to the recent climate warming in the past decades (Altermatt Reference Altermatt2010). Such long-term datasets can serve as a suitable baseline for future studies (Robinet & Roques Reference Robinet and Roques2010) because they can assist in discriminating climate change impacts from other factors that may also influence distribution and prevalence of pests (Moraal & Jagers Op Akkerhuis Reference Moraal and Jagers op Akkerhuis2011). In addition, they may have an advantage to overcome the limitations of modelling approaches (Jeger & Pautasso Reference Jeger and Pautasso2008); although not all limitations can be addressed, such as future unknown evolutionary processes of crops and pests (Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2010; Clements & Ditommaso Reference Clements and Ditommaso2011).

One modelling approach, for example, refers to ‘climate matching’, assigning a present-day geographic climate analogous to the future climate in an area of interest, and studying the pest dynamics in that assigned location from which future developments in certain regions can be extrapolated (Sutherst et al. Reference Sutherst, Maywald and Russell2000). In general, the use of data series and simulation models can assist in projecting future climate change impacts on pests (Wittchen & Freier Reference Wittchen and Freier2008). It is particularly important to collect long-term datasets for weather parameters, crop development and pest distribution and prevalence to be able to develop and validate linked ‘pest-crop-climate’ models (Madgwick et al. Reference Madgwick, West, White, Semenov, Townsend, Turner and Fitt2011). Most previous studies that focused on plant pests and climate change used simplistic climate change scenarios with uniform changes of temperature in space and time (e.g. Collier et al. Reference Collier, Finch, Phelps and Thompson1991) or ‘synthetic’ scenarios (e.g. Kriticos et al. Reference Kriticos, Sutherst, Brown, Adkins and Maywald2003), because global climate modelling had not developed enough to be able to run regional climate models with sufficient confidence to apply future climate scenarios to biophysical models (Kriticos et al. Reference Kriticos, Alexander, Kolomeitz, Preston, Watts and Crossman2006). When climate modelling had developed enough to run regional climate models with sufficient confidence, different pest models (in a few cases also linked to e.g. crop growth models) have been linked to climate change scenarios from one or several different climate models, each providing its own projection output (insects: e.g. Stephens et al. Reference Stephens, Kriticos and Leriche2007; Estay et al. Reference Estay, Lima and Labra2009; pathogens: e.g. Bergot et al. Reference Bergot, Cloppet, Perarnaud, Deque, Marcais and Desprez-Loustau2004; Salinari et al. Reference Salinari, Giosue, Tubiello, Rettori, Rossi, Spanna, Rosenzweig and Gullino2006; weeds: e.g. McDonald et al. Reference McDonald, Riha, DiTommaso and DeGaetano2009; Chejara et al. Reference Chejara, Kriticos, Kristiansen, Sindel, Whalley and Nadolny2010). A few more recent examples of modelling studies that have been published in 2011 are listed in Table 2. These considered different parameters such as changes in the number of generations of insect pests, changes in timing of plant anthesis and related disease severity, and potential changes in the global distribution of weeds. Meanwhile, researchers are also using ensemble forecasting approaches (Hirschi et al. Reference Hirschi, Stoeckli, Dubrovsky, Spirig, Calanca, Rotach, Fischer, Duffy and Samietz2011) with e.g. six different climate models providing a single average output (Junk et al. Reference Junk, Eickermann, Görgen, Beyer and Hoffmann2012). For example, the modelling study by Junk et al. (Reference Junk, Eickermann, Görgen, Beyer and Hoffmann2012) projected that the onset of stem elongation of oilseed rape (Brassica napus) in Luxembourg may occur 3·0 days earlier per decade until the end of the 21st century. The emergence of the cabbage stem weevil (Ceutorhynchus pallidactylus) in oilseed rape may occur between 3·0 and 3·3 days earlier per decade. Thus, coincidence of pest occurrence with the onset of stem elongation of oilseed rape will not be considerably influenced. However, the possible migration period of the cabbage stem weevil may be about 30 days longer under future climate scenarios, presumably leading to more difficulties in managing this insect pest in oilseed rape in Luxembourg by the end of the 21st century. Using ensemble forecasting has advantages over single-model forecasts, such as improved accuracy through combining different models that otherwise, when used singly, can have considerably different outputs, compromising their usefulness for guiding policy decisions (Araujo & New Reference Araujo and New2006). However, the use of several outputs from different climate models side-by-side can help in understanding the range of likely effects that may occur in the future (Kocmankova et al. Reference Kocmankova, Trnka, Eitzinger, Dubrovsky, Stepanek, Semeradova, Balek, Skalak, Farda, Juroch and Zalud2011, see section ‘Selected Examples of Recent Key Studies’ in the present paper). These different outputs can then be categorized as a ‘worst-case’ or ‘conservative’ scenario. In addition, Buisson et al. (Reference Buisson, Thuiller, Casajus, Lek and Grenouillet2010) pointed out that the interpretation of outputs from ensemble-based models will be one of the main challenges for forthcoming research. However, this is not the only challenge in climate change research, as illustrated in the following section.

Table 2. Selected studies published in 2011 where pest models (in few cases also crop models) were linked to outputs from regionalised climatic scenarios derived from one or several global circulation model(s) (GCM). Two examples each of insects, pathogens and weeds

* The respective time span(s) is/are compared to a baseline (e.g. 1961–90, 1971–2000).

† Respective emission scenario(s) that were used.

Note: the selected references were subjectively chosen.

CHALLENGES IN CLIMATE CHANGE BIOLOGY RESEARCH

Climate change biology research approaches should consider a region's characteristics; therefore decisions must be taken about the parameter(s) on which to focus. For example, in the tropics climate warming may cause temperature increases which are near to the current upper lethal limit of many species (Deutsch et al. Reference Deutsch, Tewksbury, Huey, Shelton, Ghalambor, Haak and Martin2008) and therefore this parameter may deserve special attention under tropical conditions. Drake (Reference Drake1994) assumed that in countries with mild winters such as Australia, climatic fluctuations (especially drought) and wind-borne migration processes (especially the initiation of insect outbreaks) are appropriate research topics, whereas in countries with harsh winters such as Canada, mortality factors and pest survival in particular are of special interest. However, complex interactions may occur. For example, apple scab (caused by Venturia inaequalis) can change the usual over-wintering strategy. Under continental climates, most inoculum sources come as ascospores from infested fallen leaves, but if the winter is mild, most primary inoculum may derive from buds as over-wintered conidia (Holb et al. Reference Holb, Heijne and Jeger2005).

In addition, the characteristics of a species and its developmental stages deserve consideration. For example, milder winter conditions such as in the British Isles may result in increased populations of species which are active during the winter, such as anholocyclic aphids, and may promote species with low frost resistance (Netherer & Schopf Reference Netherer and Schopf2010). However, mild winters are not beneficial for species that require low temperatures to increase their frost resistance or manifest their diapause (Netherer & Schopf Reference Netherer and Schopf2010). For species sensitive to low summer temperatures and rainfall, warm and dry summers will be more favourable (Cannon Reference Cannon1998; Jewett et al. Reference Jewett, Lawrence, Marshall, Gessler, Powell and Savage2011).

The effects of temperature on pests can be modified, for example by adaptation processes (Clements & Ditommaso Reference Clements and Ditommaso2011) and by environmental factors such as precipitation and snow cover (Matter et al. Reference Matter, Doyle, Illerbrun, Wheeler and Roland2011). Some observations indicate that winter rain increases the lethal effects of winter cold on many insects, whereas snow cover usually provides protection against lethal air temperatures (Bale & Hayward Reference Bale and Hayward2010). The temperature requirement can also be different during the same day. For example, insects that oviposit only at night are mainly dependent on nocturnal temperatures for oviposition, whereas daytime temperatures are less important. The same is true for pathogens. For foliar fungi, both infection and sporulation often require close to 100% relative humidity. Such moist conditions occur most commonly during overnight dewfall. Therefore, an optimal temperature for biological activity in this specific time period is particularly important (Harvell et al. Reference Harvell, Mitchell, Ward, Altizer, Dobson, Ostfeld and Samuel2002); although optimal temperature conditions may compensate for reduced canopy humidity and vice versa. Temperature and water supply are critical drivers for seed dormancy (both induction and breaking), germination, seedling establishment, population dynamics and thus species composition and competitive ability (Walck et al. Reference Walck, Hidayati, Dixon, Thompson and Poschlod2011). However, many weeds have a wide environmental tolerance, and a high level of phenotypic plasticity and evolution potential (Clements & Ditommaso Reference Clements and Ditommaso2011). They are able to adapt to different environmental conditions such as temperature. For example, weed species located at the expanding northern edge of their range must adapt to cooler conditions and a shorter growing season. Adaptive traits include for example heavier seeds, earlier growth, larger leaf size, earlier maturation and genotypes with lower temperature thresholds for leaf growth (Clements & Ditommaso Reference Clements and Ditommaso2011). These examples illustrate that the projections of future pest distribution and prevalence can be influenced by many different factors such as evolution and adaptation processes, which are in general not understood today.

Adaptive responses of host plants to environmental factors such as heat and drought stress can also be expected, which will increase the complexity of future ecosystem responses to climate change (Jump & Penuelas Reference Jump and Penuelas2005; Travers et al. Reference Travers, Tang, Caragea, Garrett, Hulbert, Leach, Bai, Saleh, Knapp, Fay, Nippert, Schnable and Smith2010). Global warming may shift the cultivation zones of important crops such as wheat and maize considerably further north (northern hemisphere) or south (southern hemisphere). Pest populations usually migrate with their displaced host plants, which makes major changes in plant protection problems less likely (Tiedemann Reference Tiedemann1996; Naylor & Lutman Reference Naylor, Lutman and Naylor2002); although there is a risk that pests may find new host species (Sutherst et al. Reference Sutherst, Constable, Finlay, Harrington, Luck and Zalucki2011). However, the question remains whether these geographical range shifts of crops and pests will also affect the potential of a pest to damage the crop severely. For example, McDonald et al. (Reference McDonald, Riha, DiTommaso and DeGaetano2009) reported that the damage niche of the weed Chenopodium album in U.S. maize production is narrower than its overall geographic range.

Even when a single factor such as temperature is investigated and therefore interactions with other environmental parameters not considered, the response of a particular pest species is difficult to determine because the various life stages of the pest may respond differently to warming. For example, in an experiment where winter warming was simulated under field conditions, egg hatch and the termination of nymphal hibernation of leaf, plant and frog hoppers (Auchenorrhyncha) occurred earlier, whereas the rate of nymphal development remained unaffected (Masters et al. Reference Masters, Brown, Clarke, Whittaker and Hollier1998). Often, the overall outcome of countervailing effects of a single factor such as temperature is unknown (Goudriaan & Zadoks Reference Goudriaan and Zadoks1995) and some species may be less sensitive to temperature changes, at least in a certain range of temperatures. This aspect leads to a challenging question: which of the many pest species and other organisms worldwide are appropriate to study potential effects of climate change and which locations might be particularly well suited to conduct such studies?

APPROPRIATE MODEL SPECIES AND LOCATIONS TO STUDY THEM

The economic importance of a pest species might be a good criterion to use for climate change risk assessments (Sutherst et al. Reference Sutherst, Constable, Finlay, Harrington, Luck and Zalucki2011), whereas in conservation planning, for example, endangered species might be of particular interest. The vulnerability of a species to climate change can also be considered. For example, Rodenhouse et al. (Reference Rodenhouse, Christenson, Parry and Green2009) concluded that the species most likely to be affected by climate change are (1) habitat-restricted species (e.g. living at high elevations, inhabiting small isolated patches of habitat), (2) species that are highly specialized (e.g. dependent on a single host plant species) and (3) those that are relatively immobile and therefore less able to escape warming through migration. For future pest risk assessments the opposite may be true. Species may be more problematic and thus deserve more attention in research (1) which are mobile, such as wheat rust pathogens whose spores are transported across great distances, even continents, via storms, (2) species that can live on/from several host plants such as generalists among insects and (3) species that are not restricted to a certain habitat such as weeds that are widely distributed, for example, Ambrosia artemisiifolia which shows great germination success over highly variable conditions in China (Sang et al. Reference Sang, Liu and Axmacher2011).

Cammell & Knight (Reference Cammell and Knight1992) recommended model species that show measurable changes in dynamics as a result of very small changes in temperature and moisture, whereas Scherm & Coakley (Reference Scherm and Coakley2003) suggested that the most promising candidates for identifying potential climate change effects are species that are less dependent on moisture and which occur naturally in unmanaged ecosystems, because the confounding effects of management factors can be excluded.

Thus, not only are the species characteristics important but also the location of the study deserves consideration. Porter et al. (Reference Porter, Parry and Carter1991) mentioned that it can be important to identify potentially sensitive regions in which to target more detailed climate change research in the future. For example, a useful point of study is to understand and map the likely change in areas of different voltinism patterns (the number of broods or generations in a year) of insect pests as a way of understanding climate change sensitivity. For this method, appropriate datasets are necessary and these should be coupled, for example, to process-based population dynamic models (e.g. Kriticos et al. Reference Kriticos, Sutherst, Brown, Adkins and Maywald2003). Coley (Reference Coley1998), who referred to tropical forests, suggested studying organisms at the edges of their ranges, because species may already experience abiotic conditions that match projected long-term changes. This is in agreement with Tiedemann (Reference Tiedemann1996), who suggested considering the warmer and colder edges of a certain crop range for climate change research related to pests.

To summarize, the effects of climate warming are probably easier to predict for pests whose geographic ranges or activities are affected mainly by temperature. Prediction is more difficult in the case of pests whose reproduction and dispersal is strongly related to water availability and management factors. This is also true for pests that are strongly affected by interactions with other organisms such as vectors or protective mycorrhizal fungi (Lonsdale & Gibbs Reference Lonsdale, Gibbs, Frankland, Magan and Gadd1996), unless their interactions are well studied and predictable. However, the development of appropriate models that consider the range defining climatic factors can assist in understanding future vulnerabilities and adaptation options for many species. Process-oriented niche models and process-based population dynamics models have been used to assess climate change impacts considering a multiplicity of range-constraining factors such as temperature, soil moisture and relative humidity (e.g. Stephens et al. Reference Stephens, Kriticos and Leriche2007; Watt et al. Reference Watt, Kriticos, Potter, Manning, Tallent-Halsell and Bourdot2010).

More information related to model species and appropriate traits of them can be found in the section ‘Theoretical Frameworks to Guide Climate Change Research’ (see below) and among many other aspects in numerous original research papers and the related review articles that have summarized them.

COMPILATION OF REVIEW ARTICLES

During the past 20 years, a large body of literature on climate change biology has accumulated (Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, Menon and Li2010). As a result, an increasing number of opinions, commentaries and review articles are available which focus on potential climate change effects on plant pests including insects, pathogens and weeds, or various combinations of these pest groups. The original focus of the present paper was on review articles in agriculture; however, as interdependencies between different plant ecosystems exist, review articles on pests and other species (e.g. beneficial and/or with no known economic effect) in horticulture, forestry and unmanaged habitats were also included, mainly because of two aspects. First, in the present review an interdisciplinary approach should be established, because the knowledge gained in different disciplines can complement each other and should be exchanged and used across disciplines (Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Grant, Green, Hunter, Jeger, Lowe, Medley, Mills, Phillipson, Poppy and Waage2011). Second, many pest species, especially mobile generalists and those not restricted to a certain habitat, live in both managed and unmanaged ecosystems. Interdisciplinary approaches are particularly important if pest species do change their host range across the boundary between unmanaged and managed ecosystems with the result of new emerging pest species in a crop and vice versa (Jones Reference Jones2009).

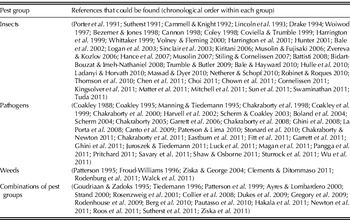

Table 3 considers review articles including a few opinions, commentaries and meta-analyses, which have been published since 1988 (until December 2011) in peer-reviewed journals. This is the time period where climate change research on pests started to become visible. However, it must be noted that some reviews are missing. Review articles that deal with climate and weather in general have not been considered in Table 3, for example, the early review articles by Uvarov (Reference Uvarov1931) and Messenger (Reference Messenger1959) on insects or the reviews by Hepting (Reference Hepting1963) and Colhoun (Reference Colhoun1973) on plant pathogens. However, there is no doubt that information provided in these earlier publications is helpful for understanding and modelling distribution and prevalence of pests with regard to potential climate change effects. Potential effects on pests due to changing climate and atmosphere are also discussed in review articles that focus on other topics such as potential future effects of climate and atmospheric change on crop yield and quality (e.g. Bender & Weigel Reference Bender and Weigel2011; Hatfield et al. Reference Hatfield, Boote, Kimball, Ziska, Izaurralde, Ort, Thomson and Wolfe2011), illustrating again the interdisciplinary character of the topic. The review articles are mostly qualitative (based mainly on assumptions and speculations); only four of them quantitatively use meta-analytical techniques to search for a general pattern in response of specific taxa of insects to climate and atmosphere factor variations (Bezemer & Jones Reference Bezemer and Jones1998; Zvereva & Kozlov Reference Zvereva and Kozlov2006; Stiling & Cornelissen Reference Stiling and Cornelissen2007; Massad & Dyer Reference Massad and Dyer2010). More of these quantitative reviews are needed in the future.

Table 3. Review articles published from 1988 until 2011 in peer-reviewed journals which focus on global climate and atmospheric change and potential effects on pests (insects, pathogens, weeds and various combinations of pest groups). Plant ecosystems in agriculture, horticulture, forestry and unmanaged natural habitats are considered

Review articles on other organisms such as beneficial species and species with no known economic effect are also included, particularly in the group of insects (e.g. Bale et al. Reference Bale, Masters, Hodkinson, Awmack, Bezemer, Brown, Butterfield, Buse, Coulson, Farrar, Good, Harrington, Hartley, Jones, Lindroth, Press, Symrnioudis, Watt and Whittaker2002; Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Macfadyen and Hoffmann2010). In 2012, few more review articles have been published (e.g. Chakraborty et al. Reference Chakraborty, Pangga and Roper2012; Pautasso et al. Reference Pautasso, Döring, Garbelotto, Pellis and Jeger2012, Siebold & Tiedemann Reference Siebold and Tiedemann2012, West et al. Reference West, Holdgate, Townsend, Edwards, Jennings and Fitt2012a,Reference West, Townsend, Stevens and Fittb), which deserve to be included in an up-dated summary table, that considers the complete year 2012.

In climate change research, insects and pathogens have received more attention than weeds (Table 3). Forty-four review articles could be found in peer-reviewed journals which focus solely on insects. Thirty-three review articles were found which focus solely on plant pathogens and the diseases they cause. In addition, 17 review articles address various combinations of different pest groups including insects, pathogens and weeds. Nevertheless, only six review articles could be found in peer-reviewed journals which focus solely on weeds in agriculture with respect to climate change (Table 3); although weeds worldwide have the highest yield loss potential (Oerke Reference Oerke2006) and more than half of the plant protection products used worldwide are for weed control (Gressel Reference Gressel2011). However, there are also a few book chapters that focus solely on weeds in agriculture (Patterson & Flint Reference Patterson, Flint, Kimball, Rosenberg and Allen1990; Bunce & Ziska Reference Bunce, Ziska, Reddy and Hodges2000; Bunce Reference Bunce and Riches2001) and on invasive plants in different ecosystems (Thuiller et al. Reference Thuiller, Richardson, Midgley and Nentwig2007). In addition, many review articles in peer-reviewed journals considered, among other aspects, potential climate change effects on invasive unwanted plants (‘weeds’) in managed and unmanaged ecosystems (e.g. Dukes & Mooney Reference Dukes and Mooney1999; Hellmann et al. Reference Hellmann, Byers, Bierwagen and Dukes2008; Tylianakis et al. Reference Tylianakis, Didham, Bascompte and Wardle2008; Walther et al. Reference Walther, Roques, Hulme, Sykes, Pysek, Kühn, Zobel, Bacher, Botta-Dukat, Bugmann, Czucz, Dauber, Hickler, Jarosik, Kenis, Klotz, Minchin, Moora, Nentwig, Ott, Panov, Reineking, Robinet, Semenchenko, Solarz, Thuiller, Vila, Vohland and Settele2009; Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Blumenthal, Wilcove and Ziska2010). Weeds are also discussed in the context of human health, as increased weed growth and development may increase the risk of humans of being exposed to plants that may cause contact dermatitis and/or incite allergies through pollen (Ziska et al. Reference Ziska, Epstein and Schlesinger2009). Recently, a few informative studies on weeds have been published in which the roles of climate and land use on plant distributions were investigated (e.g. Hulme Reference Hulme2009; Hanzlik & Gerowitt Reference Hanzlik and Gerowitt2011; Hyvönen et al. Reference Hyvönen, Glemnitz, Radics and Hoffmann2011). Finally, one recent book is devoted to weeds in the context of climate change (Ziska & Dukes Reference Ziska and Dukes2011), suggesting that work on weeds is catching up. However, if there are fewer review articles available, for example related to weeds, it might be easier and quicker for non-experts and beginners in climate change biology research to perform a literature survey.

Most authors focused on temperate climates, mainly referring to the northern hemisphere because most research was undertaken there; however, the authors increasingly also consider subtropical and tropical climatic conditions (e.g. Coley Reference Coley1998; Trumble & Butler Reference Trumble and Butler2009; Bale & Hayward Reference Bale and Hayward2010; Ghini et al. Reference Ghini, Bettiol and Hamada2011; Rodenburg et al. Reference Rodenburg, Meinke and Johnson2011; Savary et al. Reference Savary, Nelson, Sparks, Willocquet, Duveiller, Mahuku, Forbes, Garrett, Hodson, Padgham, Pande, Sharma, Yuen and Djurle2011).

Some authors focused on a particular region or country such as Finland (Table 4), but presumably these may also have relevance to other temperate regions in the world, whereas other authors of review articles used worldwide available research outcomes in order to discuss possible climate change effects on pests (Table 4). However, researchers must be careful when extrapolating results. For example, in a simulation study, the impact of increasing temperature varied with the agro-ecological zone (Luo et al. Reference Luo, TeBeest, Teng and Fabellar1995). An increased risk of rice blast disease (Magnaporthe grisea) was predicted for cool, subtropical rice growing zones such as Japan, whereas in the humid tropics such as the Philippines rice blast development would be inhibited by increasing temperatures (Luo et al. Reference Luo, TeBeest, Teng and Fabellar1995). Therefore, results related to a specific climatic zone cannot be simply transferred to other climatic zones. This holds true also for regions within the same climate zone. For example, climate change may reduce disease risk in Scotland, whereas the risk of the same disease in the same crop may be increased in southern England (Butterworth et al. Reference Butterworth, Semenov, Barnes, Moran, West and Fitt2010). Thus, the degree of exposure of each host–pest system will vary with both the climatic factor involved and with the geographical location. However, it would be extremely helpful to generalize at least basic responses of pest types to future climate change across different ecosystems and regions. Potential approaches have been suggested, for example, for insects looking at attributes such as cold hardiness strategy, life-cycle type, feeding guild, thermal sensitivity of metabolic rate and associated life-history and dispersal traits such as movement ability of species (e.g. Harrington et al. Reference Harrington, Fleming and Woiwod2001; Bale et al. Reference Bale, Masters, Hodkinson, Awmack, Bezemer, Brown, Butterfield, Buse, Coulson, Farrar, Good, Harrington, Hartley, Jones, Lindroth, Press, Symrnioudis, Watt and Whittaker2002; Berg et al. Reference Berg, Kiers, Driessen, van der Heijden, Kooi, Kuenen, Liefting, Verhoef and Ellers2010). More information on generalization of basic responses is provided below in the section ‘Theoretical Frameworks to Guide Climate Change Research’.

Table 4. Selected review articles published in 2011 in peer-reviewed journals which focus on global climate and atmospheric change and potential effects on pests (except for weeds, five examples each of insects, pathogens and various pest groups combined)

* Occasionally it was difficult to exactly identify the geographical scope.

† A=agriculture including range land, forage, etc.; F=forestry; H=horticulture including grape production; N=natural plant systems; note: occasionally it was difficult to exactly identify the plant ecosystem(s) in focus.

‡ T=air temperature increase (warming), P=precipitation patterns (mainly rainfall, but also snowfall) and any other parameter of humidity, CO2=atmospheric carbon dioxide increase, E=extreme weather events (mainly frosts and droughts, but also one or more other extremes included such as heat spells, floods/water logging, storms, etc.).

§ Responses of host plants and host–pest interactions in each review article also discussed, but not mentioned in Table 4 due to space limitations.

** The focus in each review article is on fungal plant pathogens (diseases).

Note: In general, the selected references were subjectively chosen. However, the selection process aimed at providing a broad overview on available information in the literature. In addition, review articles on tropical and subtropical conditions and on below-ground organisms were preferred, because these are rare.

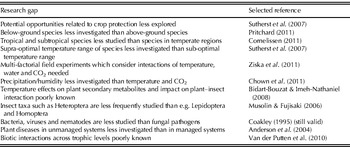

The large number of published review articles suggests that a lot of data and knowledge is already available on climate change and potential responses of plant pests and other organisms; however, there are still considerable research gaps (Table 5).

Table 5. Selected examples of gaps in climate change research related to plant pests (insects, pathogens and weeds)

In general, the selected references were subjectively chosen; however, recently published articles were preferred in order to demonstrate that research gaps are still prevalent.

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH GAPS

It is generally claimed that insect pests are likely to become more abundant as a result of climate change, whereas biodiversity and conservation are generally suggested to be endangered (Harrington et al. Reference Harrington, Fleming and Woiwod2001; Sutherst et al. Reference Sutherst, Baker, Coakley, Harrington, Kriticos, Scherm, Canadell, Pataki and Pitelka2007). The more recent literature on plant diseases has also a strong focus on increasing disease problems; although many diseases may also be less prevalent under future climate (Burdon et al. Reference Burdon, Thrall and Ericson2006). These statements suggest that researchers tend to focus more on the associated risks than on the potential opportunities related to future changing climate and its potential impacts on organisms. However, identifying potential opportunities also deserves full attention in research such as the potential retreat of troublesome invasive plant species which will create restoration opportunities (Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Oppenheimer and Wilcove2009).

Most research related to potential climate change effects on pests has been performed with above-ground pests, whereas below-ground pests and other organisms have received little attention in research (Pritchard Reference Pritchard2011); although it is very important to understand potential effects of climate change on below-ground processes including soil-borne pests (Chakraborty et al. Reference Chakraborty, Pangga and Roper2012).

Cornelissen (Reference Cornelissen2011) pointed out that research on herbivores has been mainly performed under temperate climatic conditions, whereas research related to tropical species is almost completely absent. This may be true to some extent for pathogens and weeds as well. However, in recently published original research articles (e.g. De Jesus Júnior et al. Reference De Jesus Júnior, Valadares Júnior, Cecilio, Moraes, Do Vale, Alves and Paul2008; Brenes-Arguedas et al. Reference Brenes-Arguedas, Coley and Kursar2009; Jaramillo et al. Reference Jaramillo, Muchugu, Vega, Davis, Borgemeister and Chabi-Olaye2011; Musolin et al. Reference Musolin, Tougou and Fujisaki2011; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zeng, Peng, Chen, Liang and Xin2011) and reviews (see above), tropical conditions are increasingly considered, suggesting that researchers are aware of this research gap and have started to address it. Therefore, it can be assumed that in the near future even more information will be available on potential effects of climate change on pest distribution and prevalence under tropical conditions.

Most authors focus on the expected climate impact at the cool end of the temperature range. Although this is a common practice, this perspective hinders attempts to properly discuss projected biophysical and ecological impacts. At the cold end of its range, warming may increase species abundance, whereas at the warm end, further warming is likely to increase the range-limiting stress, either directly or through biotic factors such as competition (Sutherst et al. Reference Sutherst, Baker, Coakley, Harrington, Kriticos, Scherm, Canadell, Pataki and Pitelka2007). Researchers have also focused on the cool end of the temperature range when investigating the potential effects on crops. Challinor & Wheeler (Reference Challinor and Wheeler2008) concluded that responses above the optimum temperature for crop development have not been investigated as intensively as those below; therefore, more experimental studies at supra-optimal temperatures are needed.

Until recently, most of the available data that assessed the impact of environmental conditions on pest biology were based on studies in controlled conditions, usually using a single factor approach (Ziska et al. Reference Ziska, Blumenthal, Runion, Hunt and Diaz-Soltero2011). However, especially, under higher emission scenarios and to reach a higher precision of projections, research will have to address interactions among the main driving variables such as temperature, precipitation/humidity and CO2 (Zvereva & Kozlov Reference Zvereva and Kozlov2006). For example, the effects of CO2 and nutrients on plant nutritional quality and defence compounds have been intensively investigated (Massad & Dyer Reference Massad and Dyer2010), whereas little is known about the effects of the temperature on plant secondary metabolites and how these may impact plant–insect interactions (Bidart-Bouzat & Imeh-Nathaniel Reference Bidart-Bouzat and Imeh-Nathaniel2008). In contrast to temperature and CO2, impacts of altered precipitation patterns (in most cases rainfall, but also snowfall) have been largely neglected in research on climate change (Bale et al. Reference Bale, Masters, Hodkinson, Awmack, Bezemer, Brown, Butterfield, Buse, Coulson, Farrar, Good, Harrington, Hartley, Jones, Lindroth, Press, Symrnioudis, Watt and Whittaker2002); although water availability is an important factor (Chown et al. Reference Chown, Sorensen and Terblanche2011). One reason might be the fact that sufficiently precise projections of future precipitation patterns, particularly on a small-scale regional level, are not available as compared to projections of air temperature and atmospheric CO2 content. Nevertheless, in almost all review articles, especially on forestry, drought stress of trees is considered since it is an important factor for predisposition to disease and insect pest attack (Ayres & Lombardero Reference Ayres and Lombardero2000). However, it may be of relevance to consider that insect pests of different feeding guilds may respond differently to plants exposed to stress, for example, to water stress. A meta-analysis by Koricheva & Larsson (Reference Koricheva and Larsson1998) showed that, in general, boring and sucking insects performed better on stressed plants, whereas gall-makers and chewing insects were adversely affected by plant stress. Also, pathogens react differently to forest tree water status (Desprez-Loustau et al. Reference Desprez-Loustau, Robin, Reynaud, Deque, Badeau, Piou, Husson and Marcais2007). This shows again that generalization of results can be misleading. Finally, with few exceptions (Zavaleta et al. Reference Zavaleta, Shaw, Chiariello, Thomas, Cleland, Field and Mooney2003; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Wills, Janes, Van der Schoor, Newton and Hovenden2007, see also section ‘Selected Examples of Recent Key Studies’ in the present paper), multi-factorial field experiments related to plant competition relationships are rare (Dukes Reference Dukes and Richardson2011).

Some insect taxa, such as Lepidoptera and Homoptera, have been intensively studied and their potential responses to climate warming have been particularly explored and understood, whereas far less is known about the responses of other taxonomic groups such as the Heteroptera, a large taxon with c. 37000 described species worldwide, including many species of economic importance (Musolin & Fujisaki Reference Musolin and Fujisaki2006). Research related to plant pathogens deals much more with fungal pathogens than viruses, bacteria or nematodes, as reported by Coakley (Reference Coakley1995). However, plant viruses and their vectors (Canto et al. Reference Canto, Aranda and Fereres2009; Habekuß et al. Reference Habekuß, Riedel, Schliephake and Ordon2009; Jones Reference Jones2009), bacteria (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Cunningham, Patel, Morales, Epstein and Daszak2004; Boland et al. Reference Boland, Melzer, Hopkin, Higgins and Nassuth2004) and nematodes (Neilson & Boag Reference Neilson and Boag1996) might be particularly responsive to temperature as the following two examples demonstrate. In a 3-year field experiment in maize (Zea mays) under tropical climatic conditions, Reynaud et al. (Reference Reynaud, Delatte, Peterschmitt and Fargette2009) showed that vector numbers (planthoppers Cicadulina mbila and Peregrinus maidis) and viral disease incidence (maize streak virus, maize stripe virus and maize mosaic virus) were closely associated with temperature, both increasing quickly above a threshold temperature of 24°C, whereas relationships with rainfall and relative humidity were less consistent, suggesting that global warming might promote many insect vectors and the virus diseases they transmit, at least within a certain temperature range, because the same study showed that temperatures of 30°C and above might be detrimental for the virus vector C. mbila and related virus transmission (Reynaud et al. Reference Reynaud, Delatte, Peterschmitt and Fargette2009). Also, bacteria can respond very strongly to temperature increase. A growth chamber experiment (Shin & Yun Reference Shin and Yun2010) where temperature and CO2 were elevated (30°C and 700 ppm CO2v. 25°C and 400 ppm CO2) demonstrated that temperature strongly influenced bacterial disease progress (Ralstonia solanacearum and Xanthomonas campestris) in chilli pepper (Capsicum annuum). Temperature was more important than the concurrent increase of CO2, illustrating the overriding and direct effect of temperature on pathogen development. Interestingly, in the same experiment fungal diseases (phytophthora blight caused by Phytophthora capsici, anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum acutatum) were not significantly promoted. Therefore, the Shin & Yun (Reference Shin and Yun2010) study suggests that in a warmer world bacterial diseases may gain in relative importance. Nevertheless, in tropical countries many fungal diseases are currently economically important (Ghini et al. Reference Ghini, Bettiol and Hamada2011), suggesting that warming will support any plant pathogen responsive to temperature increase, as long as its species-specific upper temperature threshold is not reached and susceptible host plants are available among other disease promoting factors.

Interactions between species are not considered in most experiments; although the final outcome of a species response to changing environmental conditions can be dependent on ecosystem processes such as competition, predation, mutualism and symbiosis (Van der Putten et al. Reference Van der Putten, Macel and Visser2010). For example, weeds are components in managed ecosystems and the inter-relationships between the component species are important (e.g. Marshall Reference Marshall and Naylor2002).

According to Massad & Dyer (Reference Massad and Dyer2010) relatively few studies on environmental change and related alterations of nutritional quality and plant defence compounds affecting herbivory were related to agriculture. However, plant diseases were investigated much more in agricultural or forestry settings than in unmanaged plant systems (Harvell et al. Reference Harvell, Mitchell, Ward, Altizer, Dobson, Ostfeld and Samuel2002; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Cunningham, Patel, Morales, Epstein and Daszak2004). Both examples again highlight the need for multidisciplinary collaboration, coordination and knowledge exchange (Scherm et al. Reference Scherm, Sutherst, Harrington and Ingram2000; Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Grant, Green, Hunter, Jeger, Lowe, Medley, Mills, Phillipson, Poppy and Waage2011).

These are some examples showing that research has focused on a limited number of taxa and aspects mainly under temperate climatic conditions in the northern hemisphere, whereas other important aspects have been less studied or even neglected. Therefore, a systematic approach would be of great value to guide climate change research on pests in crops, as recently suggested by Sutherst et al. (Reference Sutherst, Constable, Finlay, Harrington, Luck and Zalucki2011). Nevertheless, the following few selected examples of recently published key studies indicate that climate change research related to pests and other species is advancing qualitatively.

SELECTED EXAMPLES OF RECENT KEY STUDIES

The following studies related to insects, pathogens and weeds were selected mainly because they highlight few important aspects worth considering in future research, and they demonstrate the progress in climate change biology research being made in recent years. Long-term datasets have documented changes in voltinism of herbivorous European butterflies and moths due to recent warming, which in general confirms the high flexibility and adaptability of insects to climate change (Altermatt Reference Altermatt2010). Many insects with plastic voltinism have more generations per time period as temperature increases, confirming earlier theoretical studies which hypothesized that climate change may promote future outbreaks of many insect pest species. This is in agreement with projections by Kocmankova et al. (Reference Kocmankova, Trnka, Eitzinger, Dubrovsky, Stepanek, Semeradova, Balek, Skalak, Farda, Juroch and Zalud2011), whose projections suggest that in many parts of Europe the European corn borer (Ostrinia nubilalis) and the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) will probably increase their habitats, colonize higher altitudes, and increase their annual number of generations in the years to 2050 due to a projected temperature increase (when using the HadCM climate model and a high emission scenario). On the other hand, climate warming may cause temperature increases which are near to the current upper lethal limit of some insect species, particularly in the tropics (Deutsch et al. Reference Deutsch, Tewksbury, Huey, Shelton, Ghalambor, Haak and Martin2008) and during the summer in temperate climates (Bale & Hayward Reference Bale and Hayward2010) as the following studies will show.

In an experiment in Japan, simulated warming (+2·5°C above ambient) favoured the life cycle of southern green stink bug (Nezara viridula) in the spring, early summer, autumn and winter, but strongly suppressed development in mid-summer, the hottest part of the year (Musolin et al. Reference Musolin, Tougou and Fujisaki2010). Therefore, the influence of warming on the life cycle of a specific pest will also depend on the season and the related developmental stage, rendering the response to climate change rather complex in temperate regions where hot summers may prevail (Musolin et al. Reference Musolin, Tougou and Fujisaki2010). This is in agreement with experimental results demonstrating that increased temperatures can have negative effects on grasshopper survival, especially at high population densities, suggesting that species responses to climate change may need to be evaluated over a range of population densities (Laws & Belovsky Reference Laws and Belovsky2010). This is also in agreement with the projections by Kocmankova et al. (Reference Kocmankova, Trnka, Eitzinger, Dubrovsky, Stepanek, Semeradova, Balek, Skalak, Farda, Juroch and Zalud2011, see above), which suggest that temperature increase in an already relatively warm region of northern Serbia will probably result in a reduction of the number of generations per year (one instead of two generations) of the Colorado potato beetle by 2050 (when using ECHAM climate model and a high emission scenario). This is a ‘worst-case scenario’ for the pest, but possibly also for the related potato crop due to increased heat stress in the future in this specific region.

Recently, plant pathogens and the diseases they cause were studied under field conditions considering various environmental factors such as temperature in free air carbon dioxide enrichment (FACE) facilities (e.g. Percy et al. Reference Percy, Awmack, Lindroth, Kubiske, Kopper, Isebrands, Pregitzer, Hendrey, Dickson, Zak, Oksanen, Sober, Harrington and Karnosky2002; Kobayashi et al. Reference Kobayashi, Ishiguro, Nakajima, Kim, Okada and Kobayashi2006; Eastburn et al. Reference Eastburn, Degennaro, Delucia, Dermody and McElrone2010; McElrone et al. Reference McElrone, Hamilton, Krafnick, Aldea, Knepp and DeLucia2010; Melloy et al. Reference Melloy, Hollaway, Luck, Norton, Aitken and Chakraborty2010). For example, McElrone et al. (Reference McElrone, Hamilton, Krafnick, Aldea, Knepp and DeLucia2010) showed in a 5-year experiment under field conditions that the incidence and severity of Cercospora leaf spot on redbud trees (Cercis canadensis) and sweetgum trees (Liquidambar styraciflua) were greater in years with above average rainfall, probably because wet weather and humidity enhanced production and spread of conidia for secondary infections. In years with above average temperatures, disease incidence for L. styraciflua decreased significantly, presumably due to supra-optimal temperature conditions for the pathogen. FACE studies that focus on elevated CO2 allow realistic disease assessment because plants are exposed to natural pathogen loads and microclimatic conditions. They provide valuable data to evaluate the relative importance of each environmental factor involved. This allows researchers to assess the concurrent effects of temperature and precipitation variability (McElrone et al. Reference McElrone, Hamilton, Krafnick, Aldea, Knepp and DeLucia2010), and the results can also be used to develop and validate disease models, which sometimes might have unexpected projections.

The impacts of warming (canopy temperature +2 °C higher than ambient) and elevated CO2 (370 v. 550 ppm during daytime) on the population growth of four plant species important in the Australian temperate grasslands were investigated under field conditions, also in a FACE facility (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Wills, Janes, Van der Schoor, Newton and Hovenden2007). A demographic approach was found to be very useful in understanding the variable responses of plants to warming and elevated CO2 in elucidating the life cycle stages that are most responsive, including germination, establishment, survival and reproduction. In general, the impact of warming and elevated CO2 was dependent on the species. In Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Wills, Janes, Van der Schoor, Newton and Hovenden2007), warming reduced the population growth of two invasive weeds, Hypochaeris radicata and Leontodon taraxacoides. The population growth of the perennial C3 grass Austrodanthonia caespitosa was decreased by elevated CO2. Population growth of the perennial C4 grass Themeda triandra was largely unaffected by either factor. However, T. triandra was the only species in the Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Wills, Janes, Van der Schoor, Newton and Hovenden2007) study where population growth rate was slightly increased by the combination of both warming and elevated CO2 (potential future climate), whereas population growth of the other three species was greatly reduced. This might have been related to the higher water use efficiency of T. triandra. Drought can alter the competition between plants under elevated CO2 conditions such as recently shown by Valerio et al. (Reference Valerio, Tomecek, Lovelli and Ziska2011) under controlled conditions. Under well-watered conditions the C3 tomato crop (Lycopersicon esculentum) benefitted more from elevated CO2 relative to the C4 weed Amaranthus retroflexus, whereas under water stress A. retroflexus significantly increased plant height and biomass relative to tomato. In summary, the results of Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Wills, Janes, Van der Schoor, Newton and Hovenden2007) and Valerio et al. (Reference Valerio, Tomecek, Lovelli and Ziska2011) suggest that plant responses to high CO2 conditions are not predictable on the basis of the type of photosynthetic pathway of plants, as previously suggested by Dukes & Mooney (Reference Dukes and Mooney1999).

In addition, Engel et al. (Reference Engel, Weltzin, Norby and Classen2009) have shown in their ‘Old Field Community Climate and Atmosphere Manipulation Experiment’ using open-top-chambers that the effects of warming (+3·5°C higher than ambient) and soil moisture (wet v. dry) were much more influential on individual plant species and community-level responses than the effects of elevated CO2 (+300 ppm higher than ambient). The study of Engel et al. (Reference Engel, Weltzin, Norby and Classen2009) suggests that the effect of the projected elevated CO2 atmospheric content will be relatively small compared to the potential effects of the projected co-occurring global temperature increase (see also introduction for further evidence related to ecological changes observed in the past few decades). This is in agreement with Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Wills, Janes, Van der Schoor, Newton and Hovenden2007). Therefore, it might be wise to focus more on the effects of temperature and water availability than on the effects of CO2 in future climate change research experiments related to weeds; although elevated CO2 does directly affects plants (e.g. so-called CO2 fertilization effect, improved plant water use efficiency). This may also be true for insect pests and pathogens, because these are mainly indirectly influenced by elevated CO2, for example through morphological, physiological and biochemical changes in host plants, whereas temperature and humidity directly affect these kinds of pests, presumably leading to greater effects on pest distribution and prevalence. However, it cannot be completely ruled out that in certain host–pest relationships and locations, especially under future higher emission scenarios (roughly 500–1000 ppm CO2 atmospheric content at the end of the 21st century projected, see Introduction), research will have to address interactions among the main driving variables such as temperature, precipitation/humidity and also CO2, as suggested by Newman (Reference Newman2005) and Zvereva & Kozlov (Reference Zvereva and Kozlov2006). For example, a study by Dukes et al. (Reference Dukes, Chiariello, Loarie and Field2011) found that growth of the weed Centaurea solstitialis was up to six times greater in response to elevated CO2.

In spite of these general aspects on the relative importance of a single environmental factor, these selected examples of recent research studies demonstrate that the number of experimental field studies is increasing, which address combined effects of changing climatic and atmospheric factors on pests and their respective host plants. Therefore, the research gap highlighted by many authors (e.g. Ziska et al. Reference Ziska, Blumenthal, Runion, Hunt and Diaz-Soltero2011) is increasingly being addressed. However, the results achieved so far indicate that the interactions are complex and the future challenge will be to integrate this large amount of information, which cannot be easily generalized, in an easy to handle and less complex working framework, for example, to make projections of future ecological processes more robust and to suggest appropriate adaptation and mitigation strategies.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS TO GUIDE CLIMATE CHANGE RESEARCH

Proposals on how to develop working frameworks to prioritize planning in climate change biology research have been provided by several authors (e.g. Williams et al. Reference Williams, Shoo, Isaac, Hoffmann and Langham2008; Gilman et al. Reference Gilman, Urban, Tewksbury, Gilchrist and Holt2010), also specifically related to crop pests (e.g. Scherm et al. Reference Scherm, Sutherst, Harrington and Ingram2000; Sutherst Reference Sutherst, Mooney and Hobbs2000; Garrett et al. Reference Garrett, Forbes, Savary, Skelsey, Sparks, Valdivia, van Bruggen, Willocquet, Djurle, Duveiller, Eckersten, Pande, Vera Cruz and Yuen2011; Savary et al. Reference Savary, Nelson, Sparks, Willocquet, Duveiller, Mahuku, Forbes, Garrett, Hodson, Padgham, Pande, Sharma, Yuen and Djurle2011; Sutherst et al. Reference Sutherst, Constable, Finlay, Harrington, Luck and Zalucki2011).

Theoretical frameworks for climate change research with respect to multi-trophic interactions of insects have been proposed by many authors (e.g. Harrington et al. Reference Harrington, Fleming and Woiwod2001; Bale et al. Reference Bale, Masters, Hodkinson, Awmack, Bezemer, Brown, Butterfield, Buse, Coulson, Farrar, Good, Harrington, Hartley, Jones, Lindroth, Press, Symrnioudis, Watt and Whittaker2002; Helmuth Reference Helmuth2009; Berg et al. Reference Berg, Kiers, Driessen, van der Heijden, Kooi, Kuenen, Liefting, Verhoef and Ellers2010; Gilman et al. Reference Gilman, Urban, Tewksbury, Gilchrist and Holt2010; Pelini et al. Reference Pelini, Keppel, Kelley and Hellmann2010; Soberon Reference Soberon2010). For example, Berg et al. (Reference Berg, Kiers, Driessen, van der Heijden, Kooi, Kuenen, Liefting, Verhoef and Ellers2010) advocated a theoretical framework (1) to define strategic species groups, (2) to identify key species and their interactions within these groups and (3) to select appropriate traits of species to be studied. In general, it is important to understand if and how the different environmental variables are influencing physiological responses of organisms, such as body temperature and food capture, and these must be finally connected with parameters such as adult movement and dispersal of reproductive growth stages of the organisms (Helmuth Reference Helmuth2009). For example, Rall et al. (Reference Rall, Vucic-Pestic, Ehnes, Emmerson and Brose2010) found two predator groups (beetles and spiders) which exhibit increased metabolic rates due to warming, whereas effects of temperature on ingestion rates were weak, suggesting that warming has complex effects on predator–prey interactions and food-web stability. In addition, a better understanding of the species distribution across spatial scales is important for projections (Hortal et al. Reference Hortal, Roura-Pascual, Sanders and Rahbek2010). Soberon (Reference Soberon2010) suggested that abiotic conditions are fundamental at large spatial scales, whereas biotic interactions become increasingly important as spatial scales decrease.

Theoretical frameworks are also specifically developed for pathogens. For example, attempts have been made to discriminate responses of necrotrophs and biotrophs to atmospheric change (Manning & Tiedemann Reference Manning and Tiedemann1995). However, recent FACE and open-top-chamber studies continue to support earlier findings that responses to elevated CO2 levels vary with the host–pathogen system (Eastburn et al. Reference Eastburn, McElrone and Bilgin2011). Therefore, it remains impossible to generalize pathogens’ likely responses to CO2 atmospheric changes based on their mode of nutrition. Garrett et al. (Reference Garrett, Forbes, Savary, Skelsey, Sparks, Valdivia, van Bruggen, Willocquet, Djurle, Duveiller, Eckersten, Pande, Vera Cruz and Yuen2011) proposed guidelines that will help to estimate the appropriate system complexity for a particular host–pathogen model in a specific region. Savary et al. (Reference Savary, Nelson, Sparks, Willocquet, Duveiller, Mahuku, Forbes, Garrett, Hodson, Padgham, Pande, Sharma, Yuen and Djurle2011) suggested that it might be helpful to distinguish between chronic, acute and emerging plant diseases among other relevant parameters in order to better identify research priorities.

Sutherst (Reference Sutherst, Mooney and Hobbs2000) developed a conceptual framework that can be used for pests, including weeds. One major suggestion was to consider important management factors in addition to the host–pest–environment interactions, in order to assess the risk from invasive species due to changing climate. Crossman et al. (Reference Crossman, Bryan and Cooke2011) suggested integrating habitat distribution patterns and dispersal processes in order to develop an invasive plant and climate change threat index for weed risk management, noting that this approach will help to better understand weed species responses to climate change.

In summary, there are many theoretical frameworks available in the literature. Some of them are specifically related to plant pests including insects, pathogens and weeds. These can help researchers, for example, to conceptualize and prioritize planning in climate change biology research in managed and unmanaged ecosystems.

CONCLUSIONS

The tremendous increase in publications on climate change biology (Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, Menon and Li2010) each year forces researchers to continuously catch up on climate change biology literature. Therefore, the present review has been written in order to summarize the state of knowledge of potential climate change effects on insects, pathogens and weeds. However, only four reviews could be found which quantitatively used meta-analytical techniques to search for a general pattern in the responses of specific taxa of insects to climate and atmosphere factor variations. More of these quantitative reviews are needed in the future. The reader of the present review is guided through and referred to recently published review articles (see Tables 3 and 4) in this vigorously emerging research field. A virtual up-to-date synthesis and suggestions for future progress in climate change research related to plant pests is provided, for example, in the review by Sutherst et al. (Reference Sutherst, Constable, Finlay, Harrington, Luck and Zalucki2011). Nevertheless, few suggestions that might be relevant for consideration in future research are also provided in the following paragraphs.

The focus of the present review is on potential climate change effects on pest distribution and prevalence; however, a few researchers have also considered mitigation possibilities to reduce the potential future impacts of a changing climate on crop protection. For example, particularly in high-input production systems, a healthy and therefore productive crop maintained with fungicides or by using resistant cultivars can help to decrease greenhouse gas emissions (Berry et al. Reference Berry, Kindred and Paveley2008; Mahmuti et al. Reference Mahmuti, West, Watts, Gladders and Fitt2009; Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, West, Atkins, Gladders, Jeger and Fitt2011). The background is that the nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions can be reduced by a healthy crop due to more efficient use of N in organic and synthetic fertilizers. In general, farmers can contribute to improved N use efficiency by using appropriate management practices (e.g. crop rotation, tillage method, use of healthy seed, etc.) that help establish and maintain a robust, healthy and productive crop. Smith & Olesen (Reference Smith and Olesen2010) concluded that there appeared to be a large potential for synergies between mitigation of, and adaptation to, climate change within agriculture.

It should be kept in mind that climate change and related impacts on organisms are dynamic processes. For example, Fabre et al. (Reference Fabre, Piou, Desprez-Loustau and Marcais2011) reported that over the last 15 years the climate in France has become more favourable for Diplodia shoot blight of different Pinus tree species caused by Diplodia pinea and Diplodia scrobiculata; however, they assume that future climate changes in France projected for the coming 40 years should have far less impact on the disease occurrence. Thus, risk assessments should include, whenever possible, several time spans (baseline compared to e.g. 2050s, 2080s, etc.) in order to acknowledge the dynamic nature of a potential climate change effect on pests and other organisms. This might help to identify when a peak of a potential impact will be reached, and might facilitate planning of adaptation and mitigation strategies including appropriate allocation of resources.

There is a strong need to develop appropriate working frameworks, for example, to guide planning and prioritization of climate change research related to crop pests. This leads to a difficult question: which of the many pest species (and e.g. their host plants and enemies) worldwide are appropriate to study potential effects of climate change and which locations and methodologies (see Table 1) might be particularly well suited? For example, the economic importance of a pest species might be a good criterion for consideration (Sutherst et al. Reference Sutherst, Constable, Finlay, Harrington, Luck and Zalucki2011), or the vulnerability of a species to climate change (Rodenhouse et al. Reference Rodenhouse, Christenson, Parry and Green2009). It might be equally important to identify potentially sensitive regions in which to target more detailed climate change research in the future. For example, a sensitive region might be one where agriculture is at the margin of its cultivation area (Tiedemann Reference Tiedemann1996; Sutherst Reference Sutherst, Mooney and Hobbs2000) and thus potentially more vulnerable to climate change than the central part of the cultivation area, or where the adaptation capacity of farmers is relatively low due to poor resource availability, such as in many developing countries (Ceccarelli et al. Reference Ceccarelli, Grando, Maatougui, Michael, Slash, Haghparast, Rahmanian, Taheri, Al-Yassin, Benbelkacem, Labdi, Mimoun and Nachit2010). This does not necessarily mean that agricultural systems in developed countries should be neglected, because they might also be sensitive to climate change. In addition, in developed countries excellent facilities are already established to conduct long-term climate change research projects. Therefore, it might be wise to develop strong partnerships between developed and less developed countries in order to make use of complementary and synergistic effects that can be generated through international research collaborations.

A general characterization of potential climate change effects on specific taxa of species would be quite useful in order to reduce the overall experimental workload. However, generalization to date has been impossible (e.g. responses of C3 plants v. C4 plants to elevated CO2), because the interaction of temperature, water and CO2 mean that ecological processes such as the outcome of competition between members in a community may often be unexpected under changed environmental conditions. Thus, a risk assessment needs to be performed on a pest-by-pest and location-by-location basis (Sutherst et al. Reference Sutherst, Baker, Coakley, Harrington, Kriticos, Scherm, Canadell, Pataki and Pitelka2007). Nevertheless, the workload and complexity must be reduced somehow in future climate change biology research; although this might increase the risk of creating research gaps such as those highlighted in the present review (see Table 5). In addition, stakeholders require simpler, easy to handle information for decision-making (Tylianakis et al. Reference Tylianakis, Didham, Bascompte and Wardle2008). This will require courage on the part of researchers to simplify complex processes, as already demonstrated in the field of modelling (see Table 2). There is a lively debate about how to reduce complexity in climate change research without heavily compromising the reliability of projections and a few useful suggestions are already available such as those highlighted in the present review. However, their usefulness needs to be finally approved in future research strategies, preferably under field conditions.