No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 January 2009

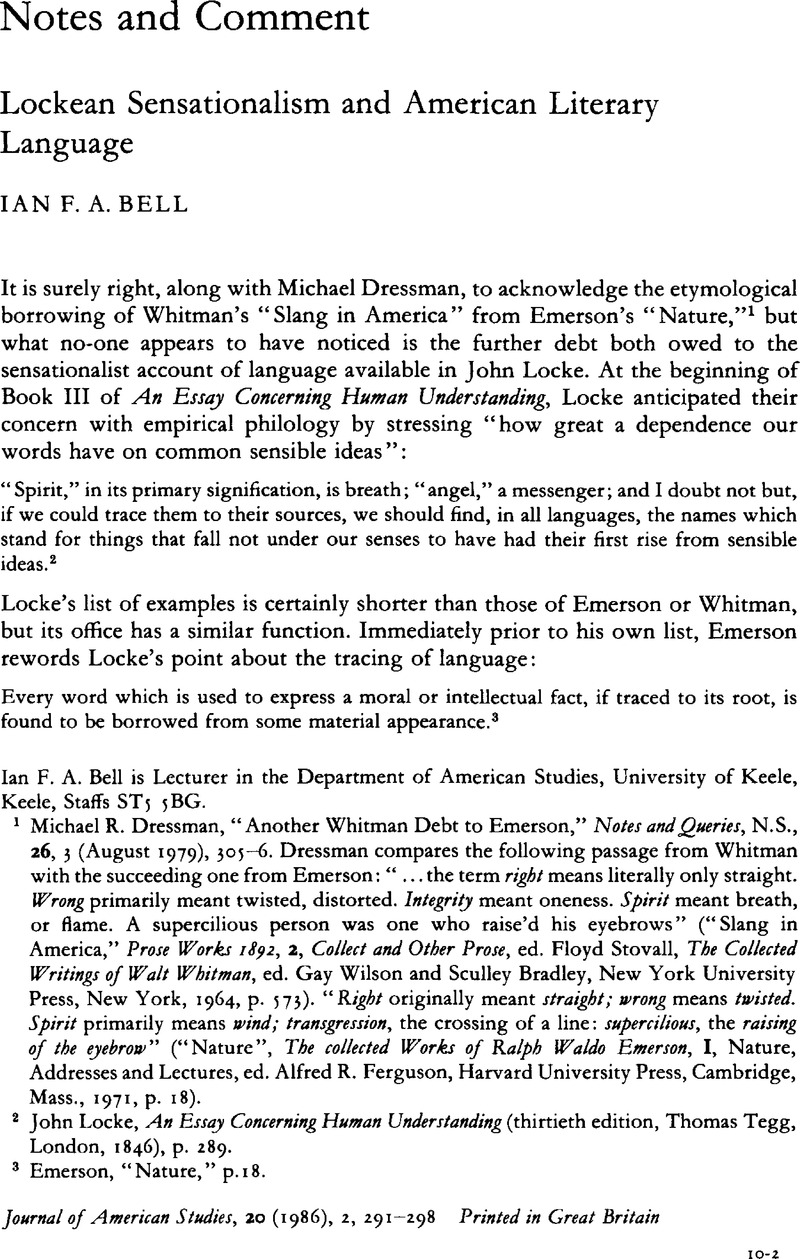

1 Dressman, Michael R., “Another Whitman Debt to Emerson,” Notes and Queries, N.S., 26, 3 (08 1979), 305–6CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Dressman compares the following passage from Whitman with the succeeding one from Emerson:“ …the term right means literally only straight. Wrong primarily meant twisted, distorted. Integrity meant oneness. Spirit meant breath, or flame. A supercilious person was one who raise'd his eyebrows” (“Slang in America,” Prose Works 1892, 2, Collect and Other Prose, ed. Floyd Stovall, The Collected Writings of Walt Whitman, ed. Wilson, Gay and Bradley, Sculley, New York University Press, New York, 1964, p. 573)Google Scholar. “Right originally meant straight; wrong means twisted. Spirit primarily means wind; transgression, the crossing of a line: supercilious, the raising of the eyebrow” (“Nature”, The collected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1, Nature, Addresses and Lectures, ed. Ferguson, Alfred R., Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1971, p. 18)Google Scholar.

2 Locke, John, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (thirtieth edition, Thomas Tegg, London, 1846), p. 289Google Scholar.

3 Emerson, “Nature,” p. 18.

4 Whitman, “Slang in America,” p. 573.

5 Locke, p. 381.

6 Ibid.

7 Whitman, p. 577.

8 Emerson, p. 18.

9 “Because of this radical correspondence between visible things and human thoughts, savages, who have only what is necessary, converse in figures. as we go back in history, language becomes more picturesque, until its infancy, when it is all poetry; or, all spiritual facts are represented by natural symbols” (Ibid., p. 19).

10 Ibid., p. 20.

11 Fenollosa, Ernest. The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry, ed. Pound, Ezra (1920), City Lights Books, San Francisco, n.d., p. 22Google Scholar.

12 Ibid., p. 25.

13 Ibid.