INTRODUCTION

To advance the study of officialdom in late imperial China, we are constructing the China Government Employee Database—Qing (CGED-Q). We hope the CGED-Q will become a major resource for research on the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), and the dynamics of bureaucracies and other large organizations more generally. The core of the database consists of transcriptions of detailed rosters of government offices and the officials who occupied them. These rosters were compiled every three months from at least the middle of the eighteenth century to the end of the dynasty in 1912. These data are useful for macro-level historical studies of overall patterns and trends in the composition of Qing officialdom and micro-level prosopographical studies of the career dynamics of officials, and as a supplementary resource for case studies of particular families, government offices, and places that employ more traditional methods and sources. We have already released a portion of the CGED-Q covering the period from 1900 to 1912 along with documentation and have long-term plans to make the entire database public.Footnote 1

As a detailed record of nearly all the employees of a large bureaucracy over a long period, this dataset is unique not only for late imperial China, but for any historical setting. Most historical big data are collected from census and household registration records.Footnote 2 Historical studies of government officials and their careers are mostly limited to high officials, because complete records of entire national bureaucracies are rare.Footnote 3 Studies of the careers of officials in contemporary China and elsewhere mostly focus on the upper tiers of central or provincial government or on specific time periods or places.Footnote 4

We construct the CGED-Q from surviving editions of the Jinshenlu 縉紳錄, a roster of government personnel (hereafter Roster) that was published every three months during the Qing. The Jinshenlu recorded officials at all ranks, from low-level officials in county offices all the way up to high officials in the central government. The quarterly nature of this source and the accessibility of surviving editions in libraries and archives make it ideal for constructing a large, longitudinal dataset. As of February 2020, the CGED-Q comprises 3,817,219 records from 243 quarterly Jinshenlu editions between 1760 and 1912.

The CGED-Q is part of our much larger, long-term effort to study the social history of China from the Qing to the present by the construction and analysis of databases from large volumes of individual-level archival data. For more than three decades, the Lee-Campbell group has sought out archival sources that we transcribe into tabular databases amenable to quantitative analysis, and then take an exploratory and inductive approach to discover basic facts about the Chinese past that are not readily apparent from traditional approaches in history, and compare China's experience to that of other societies.Footnote 5 We initially focused on family and population but in recent years have focused on intellectual, social, and political elites, of whom the officials recorded in the CGED-Q are one example.

In the remainder of this article we introduce the origins, history, and future of the CGED-Q, the sources on which it is based, the procedures by which it was constructed, its contents, and its potential applications. We emphasize the many developments that have taken place in the four years since we published our first paper introducing the CGED-Q project and our understanding of the Jinshenlu as a source.Footnote 6 In the first part, we describe the origins and history of the CGED-Q and our plans for expansion and public release. In the second part, we introduce the Jinshenlu and other sources from which we construct the CGED-Q. For the Jinshenlu, we provide an extended discussion of differences between the official government editions and the commercial editions that we use. In the third part, we describe the procedures for the transcription of the Jinshenlu and the nominative linkage of the records of the same official in different editions and different sources. We also describe additional variables that we have constructed to support analysis. In the fourth part, we present results on the composition of the civil service, including changes over time between 1830 and 1912, to showcase the potential for analysis of the CGED-Q to yield new insights into Qing officialdom not available from traditional approaches.

ORIGIN, CURRENT STATUS AND FUTURE PLANS OF THE CGED-Q

Cameron Campbell, Yuxue Ren and James Lee originally conceived of the CGED-Q in summer 2013, when Campbell learned about Ren's ongoing of study of officials in northeast China by transcription and analysis of Jinshenlu records of officials who served in that region. Based on his experience working with Lee to create population databases from northeast Chinese household registers, Campbell suggested to Ren that a database consisting of the entire contents of all available editions of the Jinshenlu would allow for a broad range of topics to be studied. Most importantly, it would make possible the study of almost the entire Qing bureaucracy and the individual officials in it over an extended period. The resulting database would be a resource for historians of China and social scientists interested in the study of careers and organizations. We began work on the CGED-Q soon afterward, initially relying on the editions in the already published Tsinghua University Library collection of Jinshenlu that were the basis for Ren's data entry.Footnote 7

We initially prioritized the entry of data for the period from 1834 to 1912 because, according to our review of editions available at different locations, that is the period for which the most surviving editions were available. Starting in spring 2016 we began to create a master list of Jinshenlu editions that eventually identified 2,843 editions held at thirty-one different libraries. After accounting for overlap where editions for the same season are held at different locations, these represent a total of 493 unique seasons.Footnote 8 Based on our review of this list, we found that we could achieve nearly complete coverage of the period between from 1834 to 1912 by supplementing the 200 editions in the Tsinghua University Library Qingdai Jinshenlu Jicheng with twenty-eight publicly accessible digital editions from the Harvard Yenching Library and forty-five digital editions in the Columbia University Library.Footnote 9

Construction of the dataset proceeded in two phases. In the first phase, from November 2014 to January 2016, all the data entry was done by three coders who already had extensive experience transcribing historical household registers from northeast China for Lee's and Campbell's group.Footnote 10 In the second phase, which began in January 2016, we added four more coders, including one to replace a coder who retired, and increased supervision of the data entry process.Footnote 11 From April 2016 to September 2016, Xiaowen Hao managed the data entry process. In September 2016, Bijia Chen took over supervision of data entry. As a result of these efforts, the CGED-Q grew rapidly from 276,904 observations from twenty-one editions entered in fourteen months by January 2016, to 989,168 observations by January 2017, 2,254,192 observations in January 2018, 3,133,958 observations by January 2019, and 3,817,219 observations from 243 editions by February 2020.

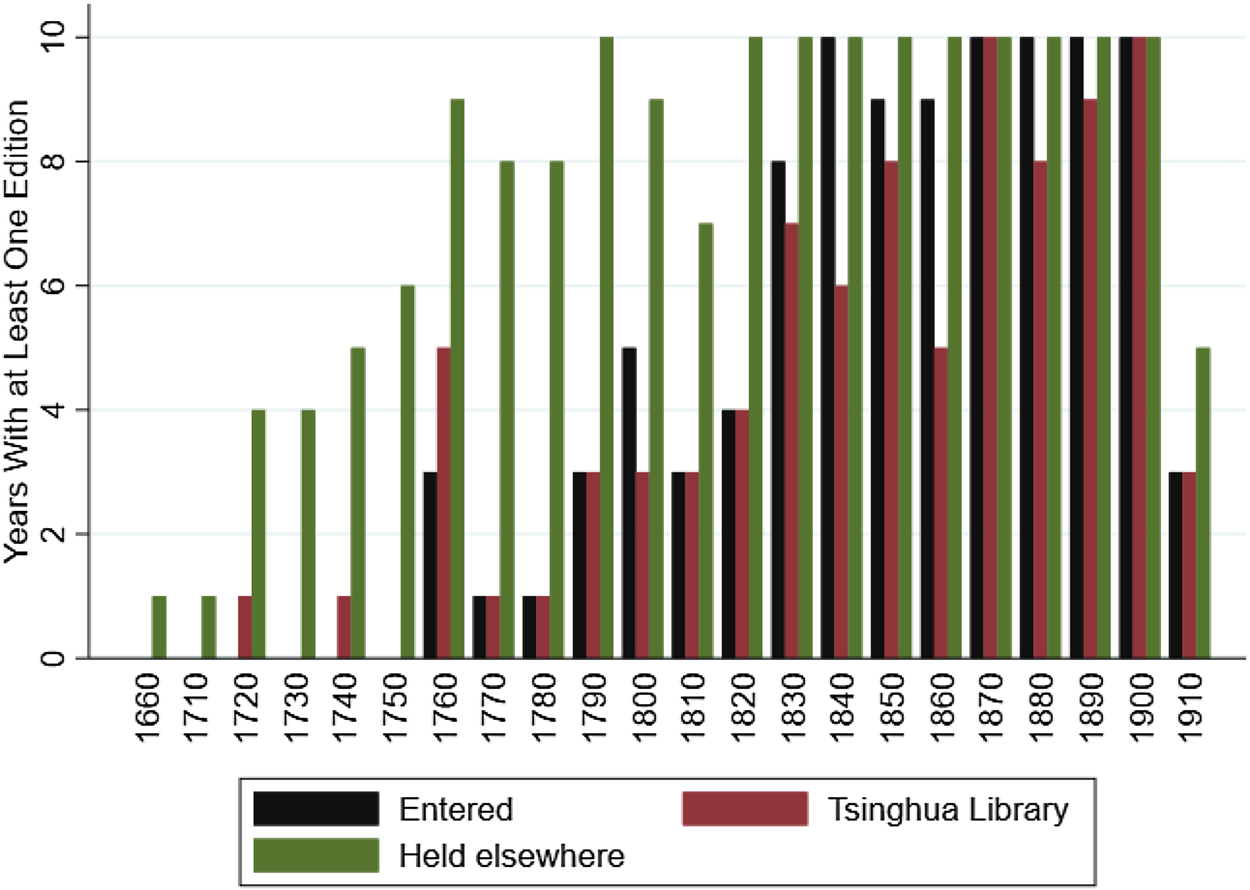

As of spring 2020, our entry of available editions for the period from 1830 to 1912 is close to complete. Figure 1 summarizes existing and entered Jinshenlu editions by decade. It presents counts of the numbers of years in each decade for which at least one edition has been entered, at least one edition is available in the Tsinghua Library collection, or at least one edition is available elsewhere. We have also entered some editions from the Qianlong (1735–1796) and Jiaqing (1796–1820) eras.Footnote 12 We continue to expand the CGED-Q. Our current priority is filling in remaining gaps for the period from 1834 to 1912 and entering editions from before 1834. Should we gain access to the collections of Jinshenlu at Peking University Library and elsewhere, we will substantially improve coverage in the last half of the eighteenth century and first third of the nineteenth century.

Figure 1. Entered or Existing Jinshenlu Editions by Decade

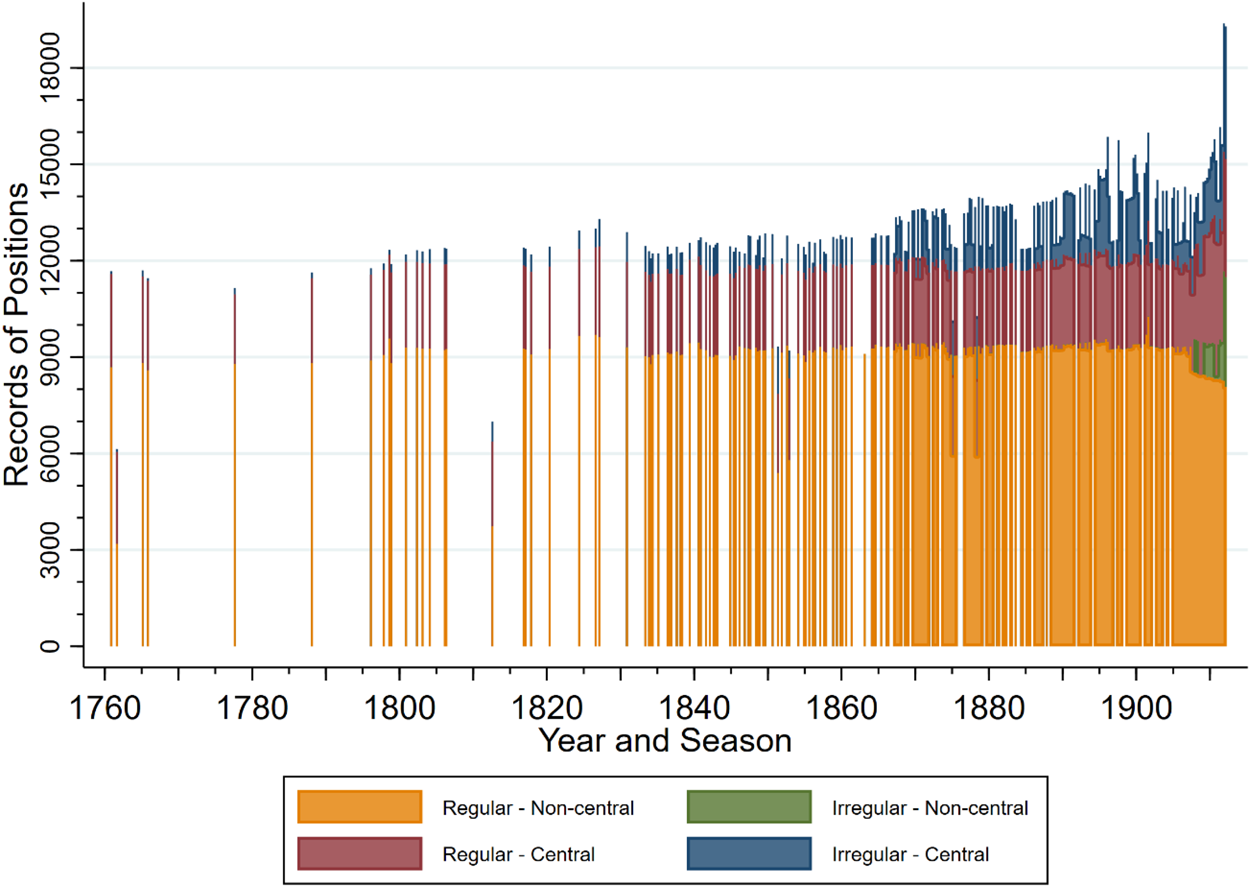

Each Jinshenlu edition recorded approximately 2,500 regular positions in the central government, 10,000 regular positions in provincial, prefectural, and count administrations, and a highly variable number of irregular positions, almost all of which were in the central government. Figure 2 summarizes the current numbers of records entered on a quarterly basis for the Jinshenlu as of February 2020. It distinguishes between records of regular positions with formal quotas (shique 实缺) that were recorded in all editions and irregular positions that were only recorded in some editions. We discuss these irregular positions in more detail below. According to Figure 2, the time coverage of the entered data for the period from 1834 to 1912 is nearly quarterly.Footnote 13 The number of regular positions was stable until the final years of the Qing, when the number outside the central government dipped and number inside the central government increased.

Figure 2. Numbers of Positions in Each Quarterly Jinshenlu Edition According to Whether They Are Regular and/or in the Central Government

We supplement the information on positions and qualifications held by officials in the jinshenlu with information from other sources. We initially prioritized information on the exam performance, age, and family background of officials with national jinshi 進士 and provincial juren 舉人 examination degrees available in same year lists (tongnian chilu 同年齒綠), provincial exam lists (xiangshi lu 鄉試綠) and jinshi exam lists (timing lu 题名綠).Footnote 14 We describe these sources and report our progress in acquiring and entering them below.

In spring 2016, we began to collaborate with other researchers and exchange data. Groups with whom we have exchanged data include the China Biographical Database (CBDB) at Harvard and the Database of Names and Biographies (renming quanxian renwu zhuanji ziliao ku 人名權威:人物傳記資料庫) at Academia Sinica. To prepare for the public release of the CGED-Q, in January 2018 we formally initiated a collaboration with the Renmin University Institute of Qing History.Footnote 15 We have also shared extracts of the CGED-Q with individual researchers on an ad hoc basis. Mostly these have been researchers conducting studies of specific locations or lineages who sought information about officials who served in or were from those locations or were members of those lineages.

Our first public release from the CGED-Q was in May 2019, when we made 638,152 Jinshenlu records of civil officials between 1900 and 1912 available for download at HKUST and Renmin University.Footnote 16 For this initial release, we provided data exactly as transcribed from the original editions, without any of the constructed variables that we use in our own analysis. Because our constructed variables depend on an understanding of the sources that is still evolving and procedures for record linkage that we are still fine tuning, we decided to release them in 2020 or later. Afterwards, we plan to release the remaining data in stages. Our current plan is for the next release of original data to be in 2021 and consist of records from 1850 to 1870, that is, the era during and immediately following the era of the Taiping Rebellion.

We also made available documentation to accompany the data. By 2015 we had a first draft of the User Guide originally produced by Yuxue Ren and co-authored by other team members. Xiaowen Hao and Bijia Chen edited and updated this in winter and spring 2016. We reviewed it at biannual meetings of all Lee-Campbell Group coders and researchers. Xiaowen Hao led these discussions in the first half of 2016 and Bijia Chen has led them since the second half of 2016. We have been revising and updating the User Guide in response to feedback from users and to reflect improvements in our own understanding of the data. When we release the constructed variables, the documentation will describe the assumptions we made for them. Users will be able to assess our assumptions and, if they have a different understanding, construct their own variables.

We and others are proceeding with studies based on the CGED-Q. Bijia Chen used the CGED-Q in a PhD dissertation that compared the characteristics and careers of officials in the Qing civil service according to whether they held exam degrees or purchased degrees or were bannermen.Footnote 17 We used the CGED-Q to examine changes in the role of banner officials in the central government between 1900 and 1912.Footnote 18 Hu Xiangyu used the publicly released CGED-Q to study judicial officials during the period from 1900 to 1912.Footnote 19 With help from Bijia Chen, Hu Heng incorporated calculations based on the CGED-Q in his study of county magistrates.Footnote 20

THE JINSHENLU AND OTHER SOURCES

The CGED-Q is composed of multiple sources linked to a core consisting of quarterly Jinshenlu records of offices and the officials who held them. As we describe below, some of the editions are official editions produced by the government and others are commercial editions produced by private publishers. Linked auxiliary sources provide additional details about the background and characteristics. Exam classmate lists Tongnian chilu provide information about the family background, exam rank, and age of a subset of officials who held jinshi and juren examination degrees. Degree Holder Lists Timing lu provide information about the exam rank of jinshi degree holders, while provincial exam lists xiangshi lu provide information about the exam rank and age of juren degree holders. Résumés (lüli) allow for case studies of individual officials and provide information on office purchase and other details related to appointment and promotion not available elsewhere. We are also acquiring county-, prefectural- and provincial-level data on conditions in these administrative units in the hope of examining how they influence the careers of officials who serve there.

PRODUCTION OF THE JINSHENLU

Rosters of government offices and personnel can be traced back to government publications such as the banchaolu 班朝錄 in the Southern Song.Footnote 21 However, the earliest surviving editions of Jinshenlu are Ming-dynasty private reprints from 1583.Footnote 22 The earliest surviving editions of the Jinshenlu that we are aware of date back to the late seventeenth century. Systematic collections of surviving Jinshenlu are available only from the middle or late eighteenth century onwards. Based on our review of library catalogues, continuous collections that include editions from nearly every year if not every quarter only become available in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. These include official editions produced by the government and commercial editions sold by publishers.

During the Qing, production of each new official edition of the jinshenlu began with the preparation for review by the emperor of initial lists of offices and their holders by the Department of Selection (文選司) under the Ministry of Personnel (吏部).Footnote 23 The information on posts and personnel changes for each new edition was gathered via a system of dichao 邸抄. Under this system, the titang officials (提塘官) from each province who were responsible for document delivery provided updates on personnel changes. There was approximately a three-month lag before the changes they reported appeared in the official jinshenlu.Footnote 24 The resulting official editions of jinshenlu have titles like juezhi quanlan 爵秩全覽 or Da Qing juezhi quanlan 大清爵秩全覽. They may also be referred to generically as guankeben 官刻本.Footnote 25 The emperor and the officials in the ministries used them when conducting their routine business.Footnote 26

The CGED-Q also includes editions produced and sold by commercial publishers. They are referred to generically as fangkeben 坊刻本.Footnote 27 While we have identified a total of twenty-four different commercial publishers, the three most common and important were Ronglu Tang 榮録堂, Ronglu Tang 榮祿堂, and Rongjin Zhai 榮晉齋. The publishing houses released each new commercial edition for sale after the official list of offices and officeholders had been reviewed by the emperor and approved for public release.Footnote 28 Commercial editions were based on the same sources as the official editions but often included additional content to differentiate themselves and attract customers.Footnote 29 Some purchasers sought to locate vacancies or decide on positions to purchase, while others sought to keep current on the holders of certain positions for the purpose of networking. Families or friends of officials may have purchased the Jinshenlu to find out where these officials had been posted.Footnote 30

Differences between commercial and official editions came to our attention as the entry of data for the CGED-Q proceeded and we noticed that adjacent official and commercial editions sometimes had very different numbers of records.Footnote 31 To understand these differences, we compared the official juezhi quanlan and a commercial jinshen quanshu for the same season. We also compared pairs of adjacent editions where one was an official edition and the other was commercial.Footnote 32 We found that the commercial editions often included 1,500 to 2,800 more records than adjacent official editions. By contrast, variation from one season to the next in the number of records in editions that were both commercial or both official rarely exceeded a few hundred. Such routine variation was often attributable to pages being missing or illegible.

This variation in the number of records between editions was partly because commercial editions often included many officials who held temporary appointments. Whereas official editions only included civil officials with regular appointments, the commercial editions typically also included officials who held temporary appointments. Comparison of a commercial and an official edition from the spring of Guangxu Year 7 (1881) revealed that 3,115 officials out of 14,967 only appeared in the commercial edition. Most of them held temporary positions annotated as ewai siyuan 額外司員.Footnote 33 71.2 percent (2,218 records) were listed under ministries or agencies in the central government. Almost every office in the central government had a few of them.

Commercial editions also provided more detail on positions and the qualifications of the officials who held them. Additional details available for a position in a commercial editions could include a more detailed title, the civil service rank of a position, the sumptuary standards for this position and rank, the distances from the national capital Jingshi for each county or province as well as notes on each province or counties on the geographical ranges, cultures and customs, schools, staging posts, taxes, and supplemental salaries (yanglian yin 養廉銀). Whereas for juren and jinshi degree holders the official editions simply record the name of the degree, commercial editions often recorded the year in which the degree was obtained. This was likely intended to appeal to purchasers who wanted to locate classmates who had taken the exam at the same time.Footnote 34

Some commercial editions listed military officials in fifth and sixth volumes titled zhongshubeilan 中樞備覽. The zhongshubeilan recorded all the military officials of the Qing government. It usually consisted of 7,000 to 8,000 records. The information included for each official resembles that in the jinshenlu. The names of the positions differ, and many more officials have wuju 武舉 degrees. We have not yet begun systematic analyses of these records.

Some commercial editions included as appendices listings of temporary or acting lower level officials from the fenfa 分發 allocation or assignment of certain categories of officials to specific positions or jobs. These were never included in official editions. The term fenfa literally means ‘distribute and assign’ and was a category of office purchase.Footnote 35 People paid to be listed in the fenfa. The fenfa lists in the commercial editions are irregular in terms of content. Many of them are named for rounds of sale of temporary offices by the government and list the names of purchasers along with the positions they were allocated and the provinces they were sent to. Sometimes the fenfa lists described the allocation of qualified jinshi candidates to county magistracies.

CONTENTS OF THE JINSHENLU

The CGED-Q organizes the information in the original jinshenlu editions into approximately forty variables structured to be amenable to quantitative analysis while at the same time adhering as much as possible to the content of the original.Footnote 36 We began with an initial specification of variables based on the template Yuxue Ren developed for her work on officials in northeast China using the jinshenlu and then adjusted later as we deepened our understanding of the source. The main categories of variables are 1) publication information, 2) ministry, agency, department, and/or office, 3) the given name of the officeholder, 4) for non-bannermen and Han Martial Bannermen, their surname, province, and county of origin, and if different from county of origin, province and county of exam, and 5) for bannermen, their banner affiliation or title, if any. If an officeholder had a hereditary status, that was recorded as well.

The organization of the records followed the structure of the Qing government system, with a division between the central government in the capital Jingshi 京師, the auxiliary capital Shengjing 盛京 and the provinces. The central government consisted of the Six Ministries (Personnel, Revenue, Rites, War, Punishments, Works), the Court of Judicial Review (dalisi 大理寺), the Office of Transmission (tongzhengshi si通政使司), the Censorate (duchayuan 都察院), the Hanlin Academy (Hanlinyuan 翰林院), the Grand Council (junji chu 軍機處), and some other officials.Footnote 37 Additional agencies and departments focused on matters related to the Imperial Household and Lineage.Footnote 38 There were five ministries in Shengjing, the same as in the primary capital Jingshi except that there was no Board of Personnel. As for the provinces, each was subdivided into several prefectures (fu 府) and each of these in turn was subdivided into departments (zhou 州) and counties (xian 縣). There were anywhere between 180 and 245 prefectures and between 1,220 and 1,260 counties listed in each edition, with the larger numbers appearing after 1900 in both cases.

The CGED-Q region (diqu 地區) and jigou 機構 variables that collectively specify the geographic location of a position and the ministry or province (機構_1), agency or prefecture (機構_2), and department or county (機構_3) are derived from headers in the original source that separate the information for groups of positions. Figure 3 illustrates how diqu and jigou are organized in the jinshenlu for central government offices. Diqu is always listed in the middle of two facing pages. For the central government, diqu is Jingshi or Shengjing. Below diqu, the names of the ministries or courts are in black boxes, starting from the Imperial Clan Court in Jingshi. For all the officials listed within an administrative unit, the diqu and jigou variables are the same.

Figure 3. Sample Page Describing Central Government Office (Juezhi Quanlan, Guangxu 25, Autumn). Collection from Harvard Yenching Library

For the central government the jigou_1 variable usually includes the yamen, which was specified in a header. Jigou_2 are usually the sub-offices or departments under yamen in the central government. Jigou_3 were officials grouped under a header like ewai siyuan or bitieshi. Because in assigning jigou_1 and jigou_2 we rely on the formatting in the printed edition rather than the organizational chart specified in formal administrative rules, the offices specified in the CGED-Q as jigou_2 are not always subsidiary to jigou_1.

Records for non-banner officials included information about their qualification for office (chushen 出身) and province and county place of origin. In principle, all appointees in the civil service had to have an official qualification. For non-bannermen, an exam or purchased degree was the most common qualification. This typically consisted of an exam degree such as jinshi or juren, or a purchased degree such as jiansheng 監生. Originally, we had a single variable for qualification. Coders reported that for some officials, more than one qualification was recorded, so we divided the variable into chushen_1 and chushen_2.Footnote 39 Records of non-banner officials also indicate the province and county where they received their degree, jiguan sheng (籍貫省) and jiguan xian (籍貫縣). In cases where officials earned their degree in a location other than their province and county of origin, records provided the information separately.Footnote 40 We entered it as separate variables yuanji sheng 原籍省 and yuan jixian 原籍县. Non-banner officials who were descendants of Confucius or who had another hereditary status had that information recorded under shenfen 身份.

The background information recorded for bannermen differed. They had their banner affiliation (qifen 旗分) recorded instead of their province and county of origin.Footnote 41 We divided this into two variables, qifen_1 and qifen_2. The former specifies whether they were identified as Manchu, Mongol, or Han Martial, and the latter specifies which of the eight banners under these broad categories they were affiliated with. Bannermen may also have a hereditary status (shenfen) as a member of the Imperial Lineage or a noble title (juewei 爵位) recorded. Bannermen had additional channels for entering the system thus not all of them had a qualification recorded.

The records of civil officials in provincial, prefectural, and county governments are organized jinshenlu first by province and then by prefecture and county. Figure 4 presents an example of a page listing county officials. Diqu specifies the province, jigou_1 usually specifies the prefecture (fu 府 or zhili zhou 直隸州), and jigou_2 usually records the county (xian 縣, or zhili ting 直隸廳). For each prefecture or county, there was a prefect or magistrate (zhifu 知府 or zhixian 知縣), such educational positions as instructors of Confucian Schools jiaoshou 教授, jiaoyu 教諭, and xundao 訓導, and other low-level officials. There is also information on the place itself, including the importance of the location (quefen 缺分) and the magistracy (guanque 官缺).

Figure 4. Sample Page for Provincial, Prefectural or County Offices (Juezhi Quanlan, Guangxu 25, Autumn). Collection from Harvard Yenching Library

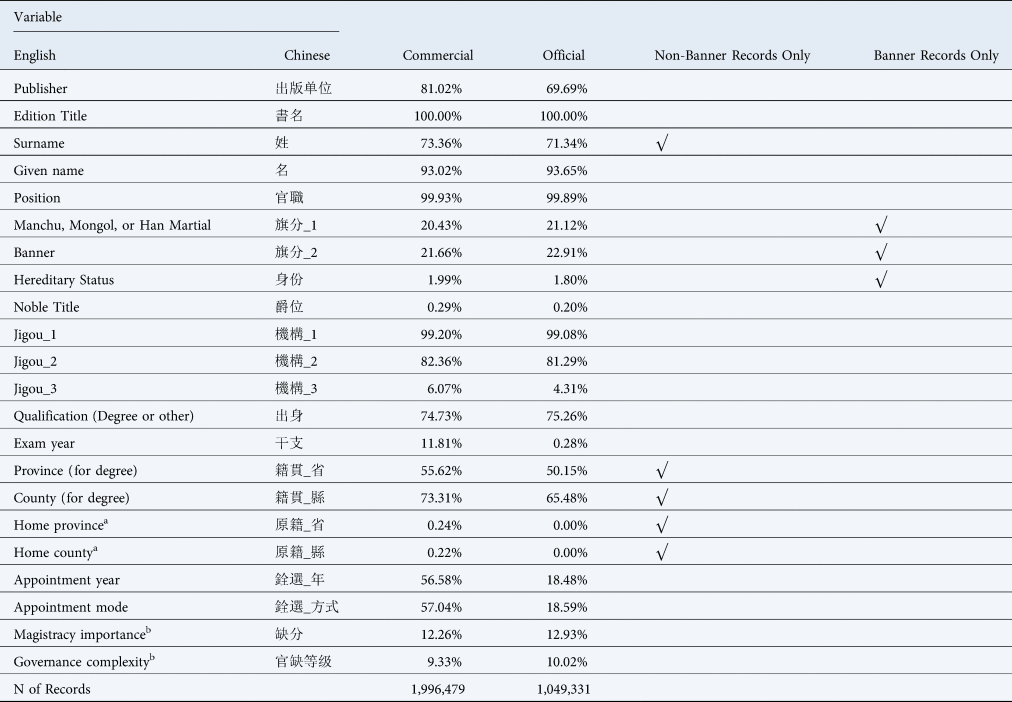

The contents of records depended on whether a position was in the central government or not, whether the official was a bannerman or not, and whether it was a commercial or official edition. Table 1 summarizes the availability and completeness of key variables by whether the edition was commercial or official and whether an official was banner or non-banner. Surname was recorded only for officials who were not bannermen or were Han Martial bannermen. Given name was blank if a position was vacant. Quanxuan 銓選 was the selection and appointment system managed by the Board of Personnel during the Qing. Commercial editions have much higher proportions of records (56 percent) that include quanxuan information, including year of appointment to the current position and the basis for their selection. In government editions, only about 15 percent of records have quanxuan. Commercial editions were also more likely to record exam year ganzhi.

Table 1. Contents of Jinshenlu Records in the CGED-Q

a Only recorded if an official took the exam in a location other than their home province.

b Only recorded for county magistrates, prefects and other head of local governance at each level.

Each CGED-Q record includes publication information from the front of the edition that identifies the publisher and the season that it covers. The reign (banben_nianhao 版本年號), year (banben_niandai版本年代), and season of publication (banben_jijie 版本季節) specify the date of each edition. The publication name (shuming 書名) and publisher (chuban_danwei 出版单位) help distinguish between official and commercial editions and between commercial editions produced by different publishers.

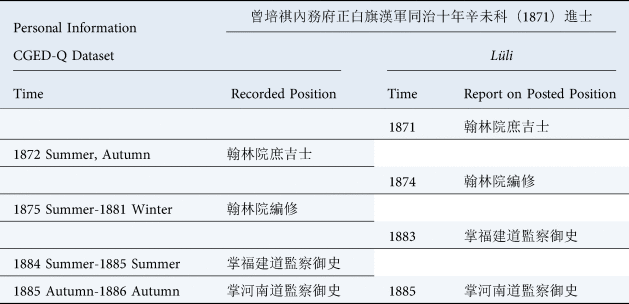

By comparison of career information recorded in the jinshenlu to career histories in the lüli (résumé) archives, we have concluded that the details in the two sources are largely consistent, though there was a time lag of a few months before changes in position were reflected in the jinshenlu. Lüli were the official résumés of candidates who were introduced to the emperor for interview before they received a formal appointment by the Board of Personnel.Footnote 42Table 2 presents an example from the comparison of the information in the CGED-Q and lüli for Zeng Peiqi, who earned the jinshi degree in 1871. He entered the Hanlin Academy as a shujishi 庶吉士, and after three years of study, he was appointed as Hanlin Academy bianxiu 編修. After nine years of service in the Hanlin Academy, he was promoted to the Supervision Bureau in Fujian in 1883 and transferred to Henan in 1885. The appointment information on Zeng were mostly consistent in CGED-Q and lüli. The only difference was that there was a time lag before changes were reflected in the jinshenlu. The lag was typically three to six months. This does not affect our analysis if the time lag is consistent. At present we are not doing any analyses where the precise calendar date of change is important.

Table 2. Comparison of Career Information Recorded in the Jinshenlu and Lüli

TONGNIAN CHILU

Through linkage to the jinshenlu, Same Year Lists tongnian chilu provide such additional information as age and family background for officeholders with national jinshi and provincial juren degrees. Tongnian chilu were compiled privately by graduates who earned their degrees in the same year. The contents and level of detail varied. Almost all records include surname, name, year of birth, province and county of origin, exam rank, and official positions held by the exam degree holder along with the names, degrees held, and official positions held by father, grandfather, and great-grandfather.Footnote 43 Surname, name, and province and county of origin allow for linkage to the CGED-Q. Publication information includes the name of the source, the year of publication, and the page number. Tongnian chilu for classes of jinshi typically list 200 to 300 holders of exam degrees. For juren, they may list anywhere between fifty and 150 holders of exam degrees, each from the same class in the same province.

Because tongnian chilu were compiled and distributed privately by graduates of specific sittings of national or provincial exams, the temporal coverage of surviving editions is uneven. Thus far we have entered data on ancestry from tongnian chilu for 2,548 holders of national-level exam degrees (jinshi) at one of 12 sittings of the exam in 1835, 1856, 1865, 1868, 1871, 1876, 1877 1880, 1886, 1889, 1890, and 1895. We have also acquired xiangshi tongnian chilu data for 6,395 holders of the provincial exam degree (juren) from sittings of the exam in different years in a variety of provinces. At present, Anhui and Jiangsu are overrepresented in our juren data, accounting for one-third of juren in our dataset. The remaining juren are distributed evenly across the remaining provinces.

TIMING LU AND XIANGSHI LU

Timing lu and xiangshi lu are official documents that list exam degree holders who earned their degrees at specific sittings of the exam. They typically include only the surname, given name, province and county of origin, and exam rank of the degree holder. For jinshi, the information on exam rank in the timing lu includes their exam tier jiadi 甲第. Xiangshi lu typically include age at time of degree. While these sources are not as detailed as tongnian chilu, they are more widely available and have broader temporal and spatial coverage. A version of the jinshi timing lu that includes all jinshi for the Qing is already available from the China Biographical Database Project. We initially experimented with the jinshi timing lu from the CBDB but currently use a jinshi timing lu dataset entered by a research assistant supervised by Yuxue Ren.Footnote 44

Timinglu were officially published lists of the successful candidates of the civil service examination at the provincial and national level, namely xiangshi timing lu (sometimes xiangshi lu) and the jinshi timing lu. The most complete collection of the surviving timing lu are those from national (Metropolitan) examinations that awarded the jinshi degree, the Huishi (or Jinshi) Timing Lu. The Jinshi Timing Lu dataset that we use was entered by Yuxue Ren from Shanghai Jiaotong University, based on the published collection edited by Jiang (2007).Footnote 45 We have also been accumulating data from xiangshi lu and now have 29,985 records of juren from various provinces and years that include their exam rank, surname, given name, and province and county of origin.

CONSTRUCTION OF THE CGED-Q

TRANSCRIPTION

Our process for transcription of the raw data from the original jinshenlu editions into Excel spreadsheets is straightforward. Coders produce one Excel file per jinshenlu edition. Initially, coders used a template developed by Yuxue Ren for entry of the data on officials serving in northeast China. The coders enter the contents of the edition on the first page of the spreadsheet and record details about the entry process, including start date and end date, on the second sheet. On the first sheet, each row corresponds to one entry in the edition and each column contains one variable. We sought to minimize the number of judgments that coders had to make. Each item in the original source was transcribed to a variable according to rules that we specified. We instructed coders to enter the original data as is and not ‘correct’ any mistakes that clearly existed in the original source, for example replacement of a character in a name with a homonym or a character that looked similar.

The coders’ approach to entering a new edition was to copy over the nearest already entered edition and then update it, inserting new records for newly appeared officials, deleting those of officials who had exited, and modifying those of officials who continued. By coding adjacent editions, an individual coder is typically able to code one edition per month, and our team was able to enter anywhere between six and ten editions every month. Because we focused on the last half of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth, data entry was especially rapid. In most cases, coders entering a new edition could do so by updating an already entered edition from an adjacent season. New editions separated from already entered ones by longer time gaps take more time to enter.

We minimized the number of judgments and subjective interpretations made by the coders by specifying that the information on jigou, that is the ministry, agency, and department, follows the format and structure of the content in the original source. This may differ from what would be suggested by the formal organizational hierarchy. After entering several editions as a trial, as described above we decided to code the jigou into three separate variables according to the format of the original source instead of asking the coders to assign contents based on the actual locations of departments in the official organizational chart.

Coders handled the black box heading for clerks (bitieshi 筆帖式) in a similar fashion. According to the format of the source, bitieshi is assigned to the third jigou level under jingshi and the Imperial Clan Court. Some coders decided to put it under variable jigou_3, because it was in a black box typically used for offices, and some of them put it under position (guanzhi) because it may be interpreted as a job title. The officials listed together under bitieshi were treated as a group and did not have a position (guanzhi) listed separately before each name. For the sake of consistency, we asked the coders to follow the structure of the source in order to reflect the original contents of jinshenlu, and we therefore had the coders enter bitieshi under jigou_3 and leave the position (guanzhi) blank. When we carry out analysis, we rearrange the contents of the fields or create new ones on the fly to suit our needs.

There are two sets of circumstances under which coders revised editions they had entered previously. The first is when they were unable to enter information for a variable on the first pass because the characters in the original were too unclear to be certain about the contents. When that happened, they were instructed to enter question marks rather than leave the field blank, so that the contents of the field would reflect that the original had unreadable content but was not empty.Footnote 46 The second was when we changed our coding rules based on new information. This was most common when we learned that previous assumptions about the format of the content in the editions was incorrect and that information that we had been putting in one field should be elsewhere. When coders revise an edition, they add the revision time and other comments to the second sheet of the Excel file.

We developed a system for assigning editions to coders and tracking their progress. To decide which editions coders should enter, we maintained a catalogue that listed every available edition in time order, indicated whether it had been coded and the accessibility of the yet to be coded editions. We used this spreadsheet to map out the order of entry for coders, identifying blocks of adjacent unentered editions that could be assigned to a coder. When assigned a new block, coders would start with one of the editions at the beginning or end and then work forward or backward. When an edition was available from the Tsinghua Collection and the Harvard or Columbia collections, coders entered the edition from the Tsinghua Collection. When both a commercial and official edition were available for the same season, coders were instructed to enter the official edition on the assumption that the data would be more reliable.Footnote 47 We collected completed Excel files from coders once a month, integrated the new files into the CGED-Q, and updated the work record of the coders.

For our interaction with the coders we relied on messaging and in-person meetings. First Xiaowen Hao and then Bijia Chen organized all six coders and Yuxue Ren, James Lee, and Cameron Campbell into a Wechat discussion group. We also met with the coders in person in Beijing or Shanghai once or twice a year for more detailed discussions. This allowed us to resolve coding issues as they arose. Examples included situations when coders encountered novel content or format or noticed discrepancies. We revised coding rules based on questions and feedback from the coders and our own analysis of the already entered data.

The key challenge as we encountered new format or contents was how to maintain procedures to structure the data that was input in such a fashion that it could be used in analysis and in the meantime keep all or almost all of the information in the raw materials without misunderstanding or misinterpretation, or imposing the coders’ or our assumptions on it. Meanwhile, our ongoing analysis as the dataset expanded identified discrepancies across editions that required attention.

Feedback from coders identified several issues that required adjustment of coding rules, revision of previously entered data, and caution when analyzing data. The systematic differences between the format and contents of official editions guankeben and commercial editions fangkeben came to our attention because of feedback from our coders. The coders also alerted us to problems inferring the structure and hierarchy of the offices from the arrangement of the text in the original sources, the discrepancy in the details provided for bannermen and non-bannermen, and the differences in format and content according to whether offices were in the central government or out in the provinces.

We collect and process newly entered data every month and integrate it into our master database. The processing is conducted by a program written by Cameron Campbell in the statistical software package STATA. Monthly processing includes a variety of steps including confirmation that the names and content of variables align with our standards, consolidation of different versions of the same character, creation of identifiers that link observations of the same official in different editions, linkage between the jinshenlu data and tongnian chilu, timing lu, and xiangshi lu, and transfer of supplementary information such as age and exam rank from these sources into the main file. Processing also produces flag and other variables that we use in our analysis.

NOMINATIVE LINKAGE

To construct career histories for officials to use in our analysis, we assigned unique identifiers to each official through nominative linkage of their records in adjacent editions. We are still modifying the code and will release it along with documentation later; here we will introduce the issues that we have faced so far. Linkage of elite Han males in late imperial China was easier than nominative linkage in historical Western populations because the combination of surname, given name, province and county was generally unique. When there were apparent duplicates within the same edition, it was almost always because an official had more than one position and a separate record for each position. Families selecting names for their sons and adult males selecting names for themselves chose names to showcase erudition and ambition. Within a lineage, using the same name as an ancestor, relative, or famous figure was considered inappropriate. Many families followed a practice of choosing a character to be included in the given names of all the males in a generation, precluding repetition of given names across generations in the same lineage. According to our analysis of the names of non-banner and Han Martial banner officials in the CGED-Q, the combination of surname, given name, and province and county of origin within a specific time period was almost always unique. Within editions, 95.14 percent of records of non-banner officials had a unique surname and given name, and 98.31 percent had a unique combination of surname, given name, and province and county of origin.

Linkage of the records of Manchu and Mongol bannermen to produce unique identifiers requires caution because bannermen almost never had a surname recorded, their given names were often transliterations of their original Manchu or Mongol names and could vary across editions, the same characters could be used in the transliteration of different names, and they didn't have a province and county of origin recorded. For linkage of banner officials, Campbell's program also relies on given names, their banner affiliation qifen and Imperial lineage affiliation or other hereditary status (shenfen) and/or noble title (juewei). In any given edition the combination of given name and banner was unique for 86.6 percent of records. Only 11.33 percent of records had a given name and banner in common with one record in the same edition. Many of these were the same person with two different posts and therefore two different records. Because of the challenges associated with linking bannermen we generally analyze them separately and are more cautious in drawing conclusions about them.

To prepare for linkage of records of the same official across editions and between sources, we consolidated character variants. Without such consolidation, programs that link and analyze the data would treat the different versions of the same character as different characters. Examples of characters that have variants include 溫 and 温. The variants existed in the original sources and coders entered characters exactly as they appeared, even when they noticed that an orthography had changed since the previous edition. Because manual consolidation of variants would be too time consuming, for the purpose of linkage Cameron Campbell developed routines that rely on specifications in the existing and widely-used Unicode standard to consolidate variants of the same character.Footnote 48 As an example of how common variants were, about 10 percent of given names (375,962 of 3,598,201) were adjusted before linkage by replacing one or more characters.Footnote 49 The replacement of characters was only for linkage and did not represent an effort to specify a variant as the ‘correct’ one, thus we preserved the original characters as entered for all uses other than nominative linkage.

For non-bannermen, the main challenge for linkage was not that records of different people might be linked together, but that records of the same person might not be linked because of differences in the characters in the name recorded for them. The issues that had to be addressed for nominative linkage, whether across editions of the jinshenlu or between the jinshenlu and other sources, were situations where for one reason or another, a character in one of the elements used for linkage changed between one edition and the next, or between the jinshenlu and other source. The consolidation discussed earlier took care of situations where different orthographies of the same character were used in successive editions, or where a simplified version of a character appeared in one or more records but not in others. Even after addressing those scenarios, however, there were still occasions where a character in a surname, given name, or in some cases a county name was replaced with a homonym in the next edition or a character with a different pronunciation but a very similar appearance, either because of an inconsistency in the original source or a keying error by a coder.

To address this, the process of nominative linkage across editions of the jinshenlu and between the jinshenlu and other sources had multiple stages. It began with a first pass using strict criteria requiring a match on given name and banner for bannermen and a match on surname, given names, and province and county for everyone else. Subsequent passes relaxed the criteria and allowed for unmatched records to be matched to record earlier editions if they only differed in terms of one character in the given name or surname but were the same on other elements. A small number of records that were still unmatched after this pass were linked with looser criteria on surname, given name, and county and province or banner, but a strict match on position.

CONSTRUCTED VARIABLES

Actual analysis requires the construction of additional variables based on the ones transcribed from the original sources. Here we introduce some of the most important ones as examples of what must be done to prepare the data for analysis. We will release these constructed variables later along with documentation. Their construction typically involves processing of the raw data and integration with information available in other sources. One of the best examples is bureaucratic rank (pinji 品級), which is crucial to the analysis of appointment and promotion. Positions recorded in the jinshenlu rarely specified their bureaucratic rank. To assign to each position a bureaucratic rank between 1 and 9 and a grade zheng 正 and cong 從 or in some cases the status of unranked (weiruliu 未入流) we distilled the positions in the jinshenlu into a master list in which each position appeared once. We created separate tables of positions and pinji from other sources such as the Collected Institutes of the Great Qing (Daqing huidian 大清會典) and then merged these into the master list of positions as a first pass to assign pinji. If a position already specified a pinji, we would not override it. Even after merging with information from the Daqing huidian, many positions had no pinji. For those positions, we assigned pinji manually.

The positions that required manual assignment of pinji can be divided into three groups. The first is mismatch due to the arrangement of information across the relevant variables. In some cases, part of the position information was included in the jigou variables. Second, some of the officials who held several titles or positions at the same time had those all listed together in a single record rather than being listed in separate records, precluding an exact match in our ranking list. This required manual assignment by reviewing the list of positions to identify the one that had the highest bureaucratic rank. The third group consists of titles or positions which do not have a civil service ranking. Examples include instructors of banner schools (baqi guanxue jiaoxi 八旗官學教習), and titang from each province.

We also group the original qualification into a manageable number of meaningful categories that are amenable to analysis. The exam and purchased degrees and other statuses recorded in the original data were diverse: there were originally 837 different types of entries in the chushen field. There were multiple degrees that were forms of jiansheng or gongsheng (貢生). We categorized the various gongsheng into regular (zhengtu 正途) or purchased (yitu 異途). We created a table that mapped the different chushen that appeared in the original data into a limited number of categories, including jinshi, juren, jiansheng, purchased gongsheng, regular gongsheng, military degree (wuju 武舉), other, and missing. Merged into the CGED-Q, this is the basis for the analysis of the influence of qualification on career trajectories. We also created a variable with the Western year of exam degree based on the ganzhi variable.

We create variables that identify irregular positions that are not recorded consistently, allowing them to be excluded in analysis of time trends and careers. This exclusion produces a subset of records covering positions that are recorded consistently in both official and commercial editions across all time periods. One variable identifies temporary positions without formal quota that only appeared in commercial editions. Another identifies positions that were only recorded in a limited number of editions, whether commercial or official. One example are the officials who served in the huidian guan 會典館, which only existed from 1895 to 1899. Another example is Hanlin Academy bianxiu. These were regular positions with shique but their numbers varied dramatically from one edition to the next, producing substantial fluctuations in record counts. In all the calculations in this article that are specified as being restricted to regular officials, all these restrictions are applied.

Other variables identify subsets of data for specific analyses. Flag variables identify subsets of records relevant for specific types of analysis. These include flag variables to identify bannermen, records of officials serving in the central government, and records in military editions zhongshubeilan. Banner officials were flagged as such if they were recorded as Manchu, Mongol, or Han Banner (qifen_1 and qifen_2), or had an Imperial Lineage affiliation or other noble title (shenfen). We also assumed an official was a bannerman if they had a given name recorded but no surname. We flagged officials as working in the central government if their location was Jingshi or Shengjing. For the latter, they had to be employed in one of the Five Ministries.

DESCRIPTIVE RESULTS

In this section we present descriptive results of the composition of the civil service, time trends, and career lengths. Such results illustrate how even simple tabulations yield new insight into late Qing officialdom. Table 3 presents the shares of officials after 1830 who are civilian, banner, and Imperial Lineage for five categories of posts defined by geographic location. During this period, the difference between central and local government is quite clear: bannermen dominated in the central government, but non-bannermen accounted for most of the officials out in the provinces (93.86 percent) and even in Fengtian prefecture in northeast China, the homeland of the bannermen and the location of Shengjing.

Table 3. Distribution of Banner/Lineage/Minren Civil Officials by Location, 1830–1912

Note: The records of Imperial Household, irregular positions, and other records that only show up in commercial editions are not included, and records with blank given names are also excluded.

The distributions of bureaucratic ranks of officials differed according to whether they were non-bannermen, bannermen, or members of the Imperial lineage. Table 4 presents the distribution of ranks for each category of official. Members of the Imperial Lineage, while numerically the fewest, were the most privileged: 13.57 percent of Lineage Members who were officials were rank 1 and 7.37 percent were rank 2. The shares with rank 5 or 6 were also much higher. Next in terms of privilege were officials affiliated with the banners. The share with ranks 1 through 6 was much higher than the corresponding share for officials who were not affiliated with the banners. A large share of banner officials also held rank 9 positions. Most of them were clerks (bitieshi).Footnote 50 The distribution and pattern in Table 4 is consistent with existing understandings of the privileges of banner officials in the civil service system.Footnote 51

Table 4. Civil Service Ranks (品級) According to Status as Non-Banner, Banner, or Member of the Imperial Lineage, 1830–1912

Note: The records of Imperial Household, irregular positions, and other records that only show up in commercial editions are not included, and records with blank given names are also excluded. Within each numeric rank we have combined grades zheng and cong to save space.

Table 5 presents the distribution of methods of qualification in the CGED-Q, distinguishing officials according to whether they were bannermen and whether they served in the central government or out in the provinces. Examination of subtotals reveals that most officials in the provinces were non-bannermen, while bannermen accounted for 75.27 percent of the officials with regular positions in the central government. Differences between the central government and the provinces in the share without methods of qualification were driven mainly by differences in the share of officials who were bannermen and therefore less likely to have a methods of qualification recorded.Footnote 52

Table 5. Distribution of Methods of Qualification by Central Government Versus Provinces in CGED-Q, 1830–1912

Note: The records of Imperial Household, irregular positions, and other records that only show up in commercial editions are not included, and records with blank given names are also excluded.

Among the degree-based methods of qualification, purchased jiansheng degrees were the most common, accounting for 28 percent of records overall (25 percent non-banner and 3 percent banner officials). Most jiansheng served in local government. They accounted for 34 percent of officials outside the central government but only 11 percent of the officials in the central government. The second largest group of degree holders serving in the system were juren (16.4 percent). Again, juren were more common outside the central government than inside. One-fifth of civil officials outside the capital had a juren degree, while in the central government in the capital, only 2.91 percent of officials held a juren degree. Jinshi, regular gongsheng, and irregular (purchased) gongsheng each accounted for approximately seven percent of officials. Ten percent of the civil officials in the central government had a jinshi degree, while only 6.21 percent of officials elsewhere held one.Footnote 53

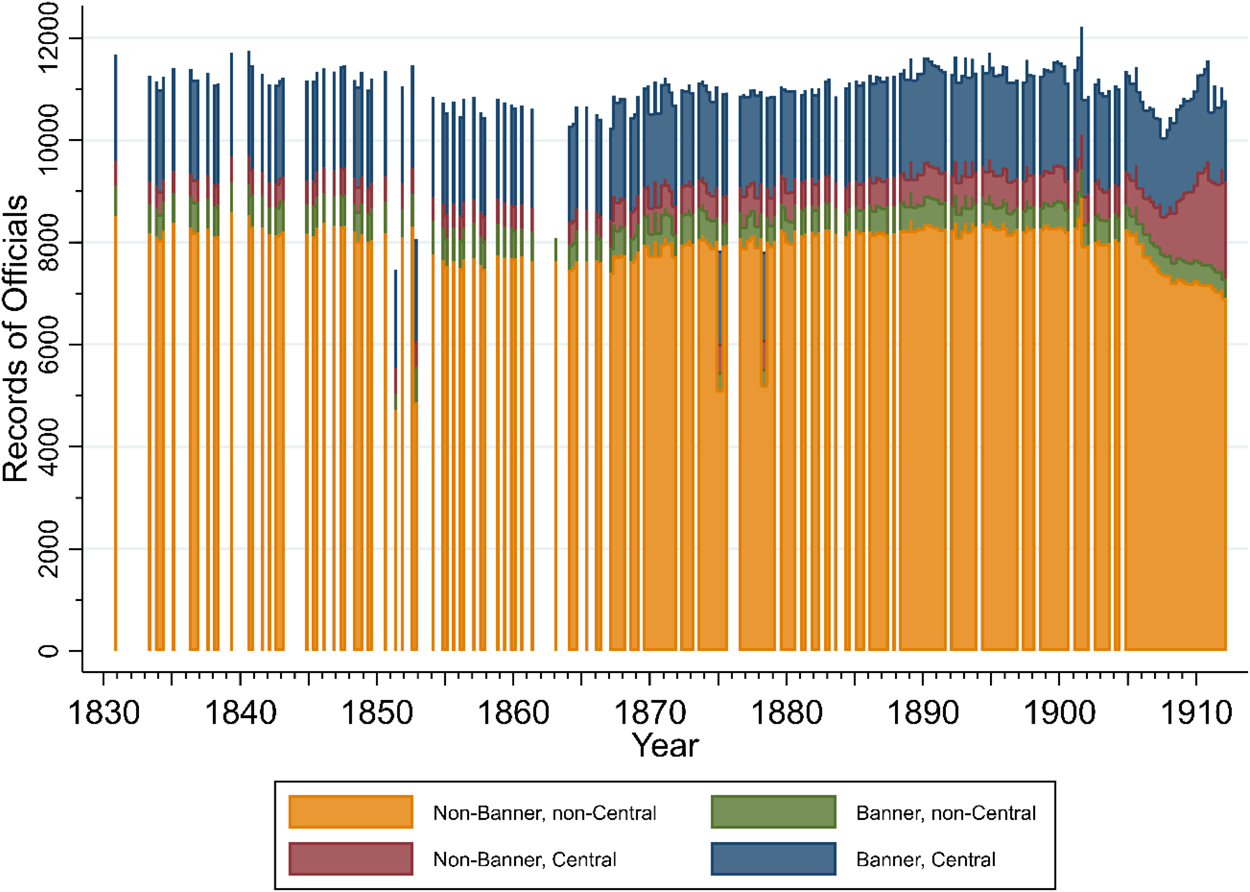

The shares of bannermen and non-bannermen inside and outside of the central government were stable over time. Figure 5 presents the numbers of officials who held regular positions in each edition according to whether they were in the capital and whether they were bannermen. The numbers of officials are slightly lower than the numbers of offices in Figure 2 because Figure 5 excludes vacant offices. The numbers of officials serving outside the capital declined slightly after 1850, possibly because of the Taiping Rebellion, and then began recovering after 1865. The numbers outside the capital fell again after 1905 and the share of those who were bannermen also fell. Meanwhile, in the capital, non-banner officials consistently accounted for only a small share of officials overall until 1905. After 1905 their numbers expanded rapidly while the numbers of banner officials stayed the same.

Figure 5. Regular Officials By Whether They Were Banner and/or Central Government, 1830–1912

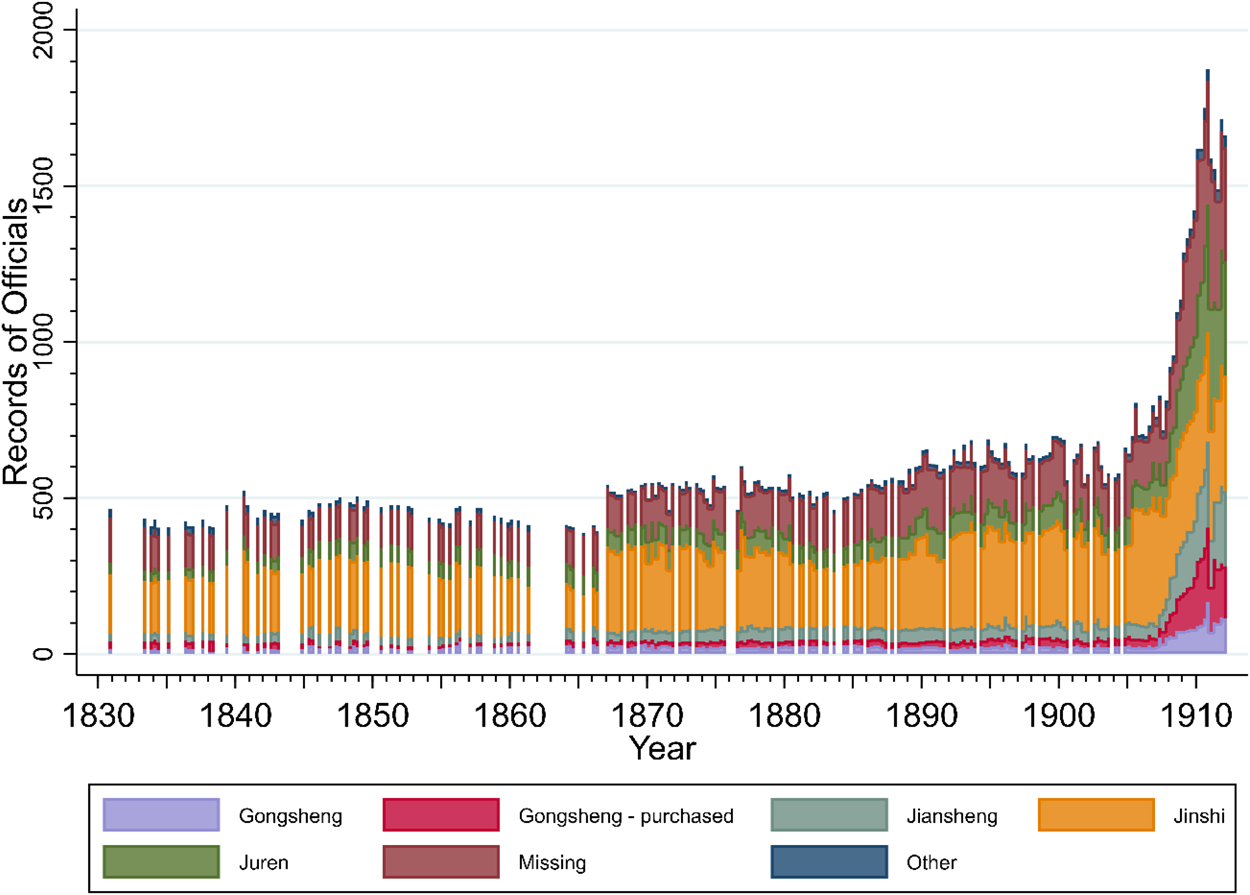

Figure 6 presents the methods of qualification of non-banner officials serving in the central government by time.Footnote 54Jinshi consistently accounted for 40 percent of the non-banner officials serving in the central government and their numbers were very stable. 64 percent of the jinshi in the central government held ranks between 4 and 6, and the remainder were evenly divided between ranks 1–3 and 7–9. One-quarter of the non-banner officials had no chushen recorded. Two-thirds of them held positions with ranks 7 to 9 and another one-fifth held positions for which we have not yet identified ranks. Forty percent were in the Imperial Medical Department and another 27 percent were in the Directorate of Astronomy. There were few regular gongsheng and even fewer jiansheng. After 1907, the numbers of non-banner officials serving in the central government exploded, mainly as a result of an increase in minor capital officials (xiao jingguan 小京官).Footnote 55 The numbers of juren, jiansheng, and regular and purchased gongsheng increased dramatically while the numbers of jinshi remained stable. The stability in the numbers of jinshi after 1905 and the increase in the number of juren is notable considering that the examination system was abolished in 1905.

Figure 6. Chushen of Non-Banner Regular Officials Serving in the Central Government, 1830–1912

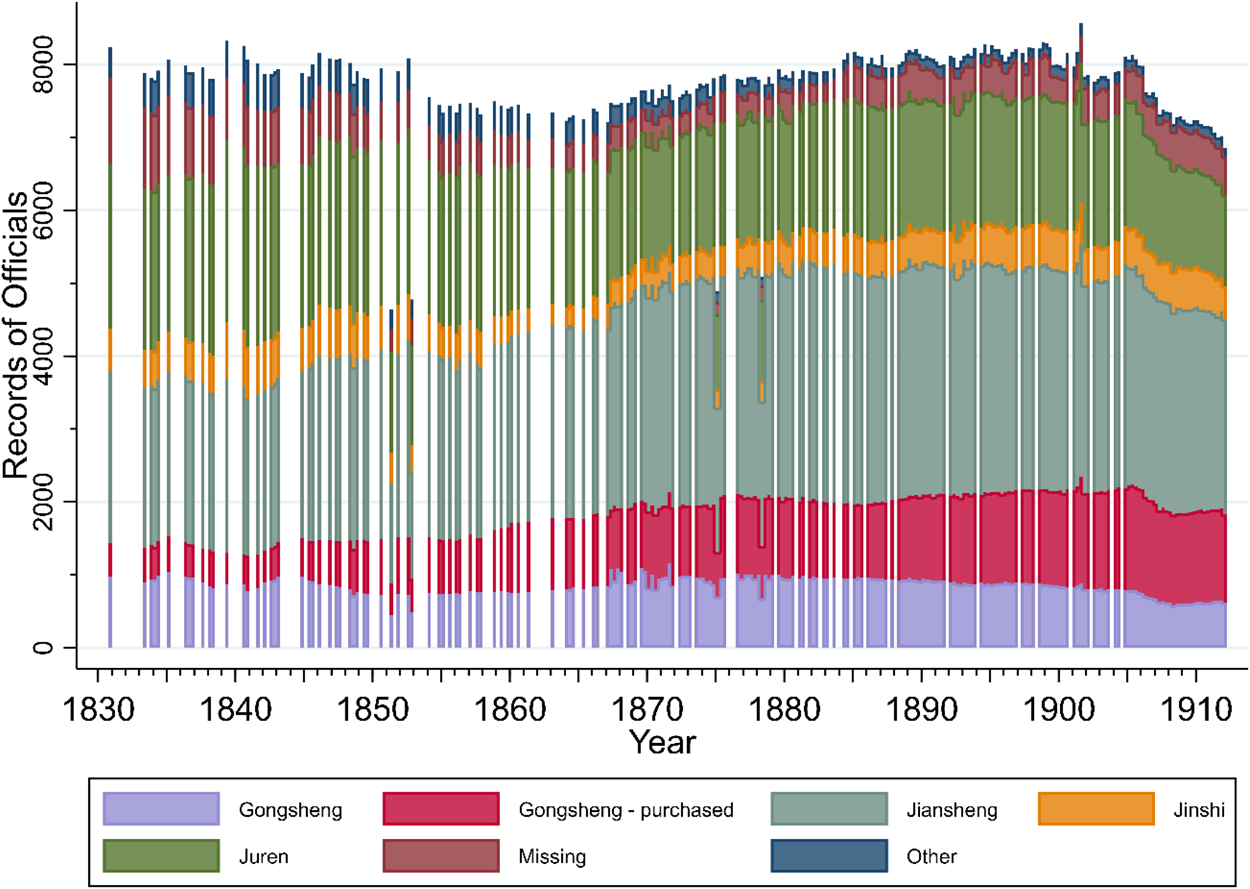

Outside the central government, the numbers of holders of purchased degrees increased between 1830 and 1912. Figure 7 shows the share of different chushen of non-banner civil officials serving outside the provinces over time. Jiansheng accounted for a plurality of officeholders and their numbers increased until 1880. Purchased gongsheng were initially uncommon but their share increased over time, at least until 1905. As a result of these trends, the holders of jiansheng and purchased gongsheng degrees went from accounting for only 30 percent of officials outside the capital in 1830 to accounting for 50 percent of them by 1869. Their share remained stable until 1895, when it began creeping upward once more, reaching 55 percent by 1911. Of the examination degrees, juren was the next most common qualification. Initially there were nearly as many juren as jiansheng, but their share declined over time.

Figure 7. Chushen of Non-Banner Regular Civil Officials Serving in Provinces, 1830–1912

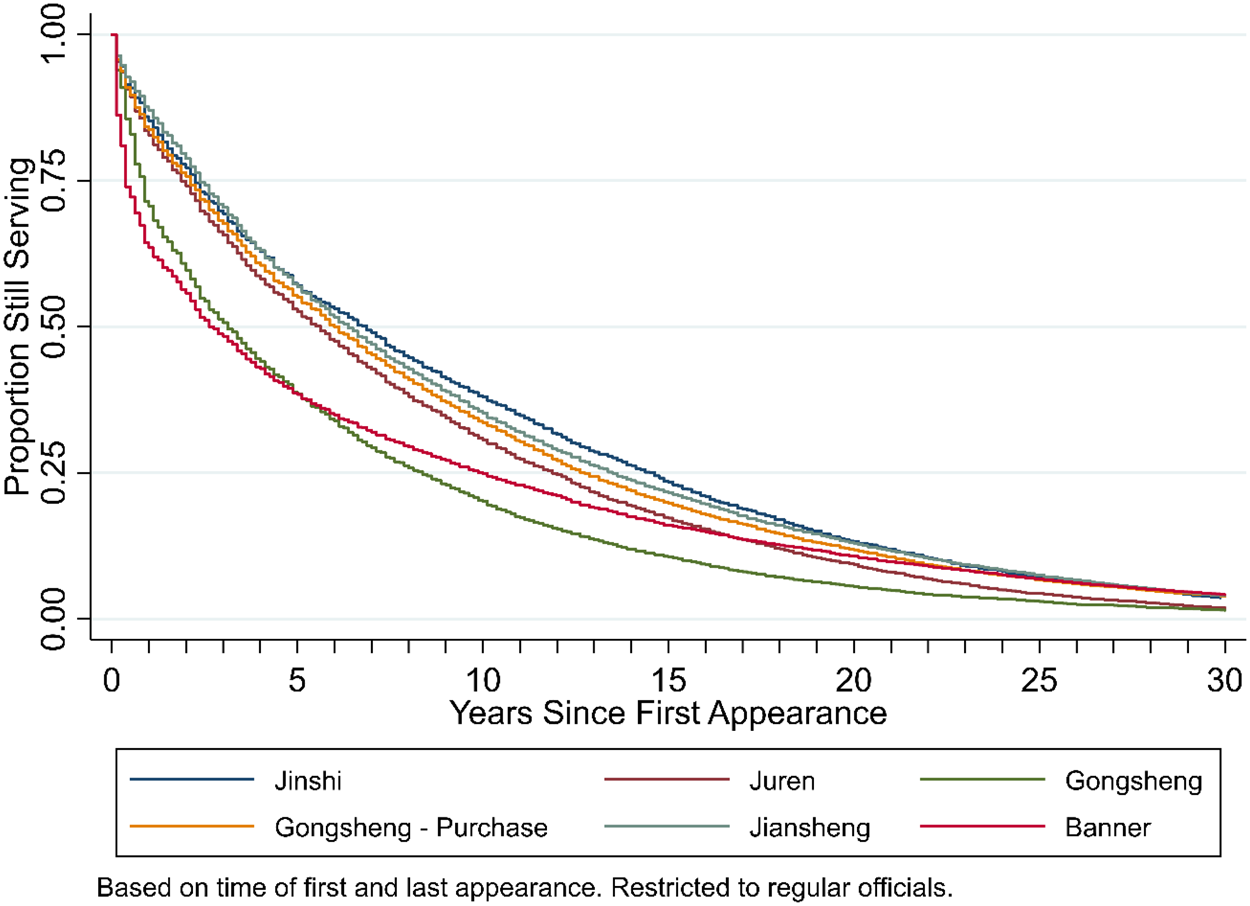

Career lengths differed according to methods of qualification. Figure 8 presents the proportions still serving in a regular position by years since first appointment and qualification for appointment or chushen. The calculations are based on career histories constructed by nominative linkage of officials from one edition to the next. All banner affiliates in a separate category regardless of their recorded chushen. Regular gongsheng and bannermen were the most likely to leave soon after appointment, with only half of them remaining for three or more years. Bannermen who lasted for six or more years were more likely to persist, so that their total proportions still in office were the same as everyone except jinshi and regular gongsheng by sixteen years after first appointment. The remaining categories of officials had similar career lengths. Approximately half served for seven more years. Jinshi had slightly higher rates of persistence while juren had slightly lower rates of persistence.

Figure 8. Proportion Still Serving by Years Since First Appointment by Chushen

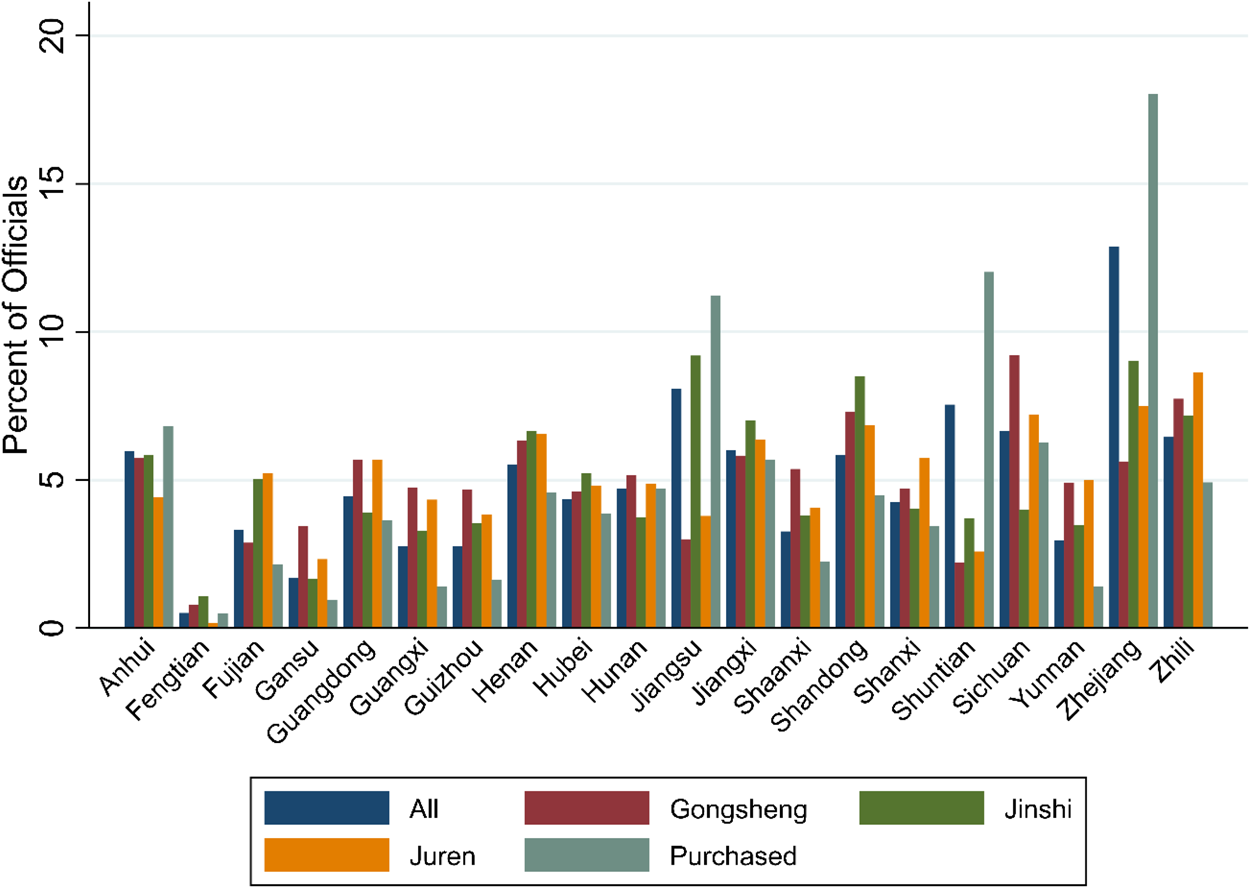

Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Shuntian are the top three provinces of origin for civil officials with regular appointments, accounting for nearly 30 percent of all non-banner civil officials. Figure 9 presents the percent of officials from each province for all officials combined and then separately for each of four categories of chushen.Footnote 56 The overall distribution of officials by province of origin broadly resembles the distribution of provincial quotas for jinshi even though, according to Table 5, jinshi accounted for only 7 percent of officials. Zhejiang accounted for 12.95 percent of officials, Jiangsu accounted for 8.16 percent, and Shuntian accounted for 7.75 percent. Jiangsu and Zhejiang together accounted for more than 20 percent of officials, even though they accounted for only 11.85 percent of the population of China at the end of the Qing.Footnote 57 Shuntian was overrepresented because of its special status in the civil service exam. A disproportionate number of candidates took their exams there and they had priority in quota allocation according to the civil exam rules.

Figure 9. Provinces of Origin for Regular Non-Banner Officials, Overall and by Chushen

Some deviation from the overall pattern was apparent in the provinces of origin for specific categories of chushen. The most striking was for purchased degrees. Two provinces, Zhejiang and Jiangsu, accounted for close to one-third of the officials who held purchased degrees: Zhejiang accounted for 18.04 percent and Jiangsu accounted for 11.19 percent. When offices were being sold, candidates from Zhejiang accounted for the largest shares of purchasers.Footnote 58 As for jinshi serving as officials, Jiangsu and Zhejiang did especially well, accounting for 9.41 and 9.69 percent of the regular officials who held that degree, respectively. Their combined total, 19.1 percent, was higher than the percentage of jinshi degree holders who came from those provinces, 16 percent, implying that degree holders from those provinces were more likely to be appointed or had longer careers.Footnote 59

CONCLUSION

The CGED-Q is a major new source for the study of Qing officialdom and Qing history more generally. The institutional context and procedures for the compilation of the jinshenlu editions that are the basis of the CGED-Q are now relatively well understood, as are the key differences between the official and commercial editions. The process for transcription of jinshenlu editions into the CGED-Q was straightforward, and as much as possible it emphasized preserving intact the contents of the original sources and avoiding judgments or subjective interpretations on the part of the coders. Additional information on a subset of officials who were examination degree holders has been drawn from auxiliary materials such as tongnian chilu and xiangshi lu. For the purpose of analysis, we have constructed variables that link together records of the same official in different editions, categorized positions according to their bureaucratic rank, and grouped chushen and other variables into a manageable number of categories. We have shown that the data are already amenable to analysis of the sort that is common in historical and social scientific studies. We have publicly released the data for the period 1900–1912, and we plan eventually to release all the data. Because of its longitudinal depth, size, and detail, we hope that the CGED-Q will be used not only by Qing historians, but by social scientists more generally.