Introduction

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are a distinct group of countries within the Pacific, the Caribbean and the Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Mediterranean and South China Sea (AIMS) which exhibit unique vulnerabilities. Although the 58 defined SIDS comprise less than 1% of the world’s population, they represent a huge diversity of unique populations, contexts and cultures. 1 In addition to experiencing developmental and economic challenges, which are characteristic of many developing countries, SIDS are distinctive in terms of their small population size, remoteness and susceptibility to natural disasters. 2 Typically, these island states have economies that are vulnerable to external shocks, which are further exacerbated by the effects of climate change. The average annual losses due to climate change as a percentage of GDP is considerably higher in SIDS compared with the rest of the world. Globally, it is estimated to be 0.5%, compared with examples from SIDS such as the Solomon Islands (3%), Tonga (4.2%) and approximately 6.5% in Vanuatu. 3 The wide range of pressing issues affecting these states can therefore hinder their progress in sustainability, health and finances.

Alongside these restraints, SIDS are burdened by some of the highest non-communicable disease (NCD) rates in the world. Table 1 outlines the demographics, chronic conditions and health indicators for SIDS within the Pacific region. The countries listed in Table 1 have an average rate of adult obesity of 40%. This burden is considerably greater than high-income, developed countries in the same region, such as New Zealand and Australia, where the average obesity rate is 26%. 4 Data from the World Health Organization (WHO) also shows that this obesity rate within Pacific SIDS is high compared with SIDS in other regions: 24% in Caribbean SIDS and only 13% in the AIMS region (excluding high-income countries). 4 This highlights that globally, Pacific SIDs experience some of the worst rates of NCDs and related risk factors. Table 1 also demonstrates that this burden is more pronounced in those states with smaller populations, such as the Cook Islands, Nauru and Niue, that have less than 20,000 people and exhibit much higher rates of obesity, diabetes and raised blood pressure levels. Therefore, the unique combination of environmental, financial and health issues presents a challenge. Despite international recognition of these disadvantages, SIDS continue to be largely ignored and not given ‘island-specific support’ that considers each unique context. 5 This lack of international response and support for SIDS-based research and innovation continues to be a barrier that is stalling progress in these nations. 5 In order to address these issues and improve health outcomes, SIDS need to be adequately represented in global research priorities.

The context of early-life environment in SIDS

Nutrition transitions are another commonality for SIDS, particularly in the Pacific, with changing trade policies and increases in imported goods coinciding with high NCD rates.Reference Thow, Heywood and Schultz 6 As a result of this transition from traditional diets to more processed foods, there is concern over the mismatch between humans’ evolved physiology and the unhealthy environments they are increasingly exposed to.Reference Gluckman and Hanson 7 While this mismatch can impact individuals’ own susceptibility to metabolic diseases, it can also negatively influence the development of future generations. Developmental programming in offspring can occur as a result of adverse early-life environmental exposures, including poor maternal diet and stressors, and negatively influences health outcomes in later life.Reference Hanson and Gluckman 8 While a poor early-life environment can predispose these individuals to later disease, exposure to an unhealthy postnatal environment can provide a second hit, exacerbating risk.Reference Hanson and Gluckman 8 Moreover, the effects of such programming have been shown to be trans-generational in nature, thus perpetuating the cycle of NCDs across generations.Reference Aiken and Ozanne 9 A life-course approach is thus essential to highlight the importance of early-life stages for preventing chronic diseases and acknowledges the social determinants of health, such as nutrition transitions.

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) paradigm explores these ideas of how early-life environmental factors influence later health outcomes, particularly chronic disease risk, in adolescence, adulthood and inter-generationally.Reference Hanson and Gluckman 8 It addresses the significance of not only the pregnancy and infancy life stages in determining later health, but also emphasizes preconception, paternal health and inter-generational health outcomes.Reference Hanson and Gluckman 8 Therefore, current health interventions which focus on changing adult diet and physical activity may be less effective than prevention strategies targeted earlier in the life course. There is increasing recognition for the relevance of DOHaD in low- and middle-income countries, where very few studies have been undertaken.Reference Hanson, Gluckman, Ma, Matzen and Biesma 10 , Reference Uauy, Kain and Corvalan 11 Although not extensive, there has been some research in these contexts identifying links between early-life exposures and later disease risk, such as in African nations.Reference Hanson, Gluckman, Ma, Matzen and Biesma 10 , Reference Norris, Daar and Balasubramanian 12 The application of DOHaD concepts could therefore be relevant for research in other developing nations and potentially critical for the development of effective trans-generational prevention strategies.

The complexity of DOHaD in SIDS

Under the DOHaD framework, NCD development is viewed as a complex process influenced by many gene-environment interactions across a multitude of life stages. As SIDS already experience a unique set of constraints, the issue of chronic disease development is arguably even more complex. An NCD risk factor perhaps more relevant to low- and middle-income countries is stunting or impaired growth – commonly observed in children as a result of malnutrition. 13 In the Pacific region, several SIDS have high rates of stunting: 33% in the Solomon Islands, 26% in Nauru and 24% in Vanuatu. 14 This impaired growth early in childhood can lead to the development of obesity later in life and can cause complications during pregnancy and childbirth. 14 It is important to recognize that malnutrition can include children who have access to an abundance of food that lacks nutritive content. Thus, the rise of imported goods and Westernized diets in many Pacific SIDS presents yet another challenge of wider societal factors influencing individual health and, as the DOHaD concept identifies, intergenerational health. Research must recognize this idea of complexity in relation to NCDs and shift the focus from individual behaviours and choices.

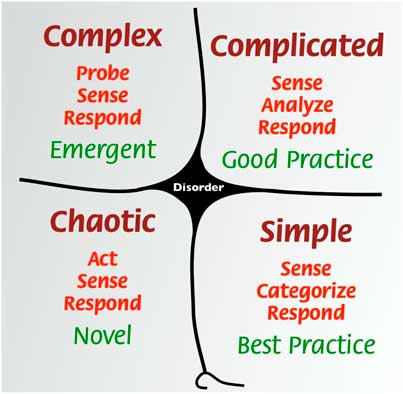

The complex socio-ecological factors influencing NCD risk necessitate that it should not be viewed solely as a health problem, but rather a multisectoral concern. NCDs and the SIDS environment are both complex, dynamic systems that together, present an even more multifaceted set of issues.Reference Bay, Morton and Vickers 15 , Reference Unwin, Samuels, Hassell, Brownson and Guell 16 The Cynefin model of decision-making (Fig. 1) highlights that is not enough to consider ‘best practice’ strategies in complex adaptive systems, as such strategies specify a simple cause and effect pathway, encouraging a reductionist view of complex issues, such as NCDs.Reference Bay, Morton and Vickers 15 Rather, strategies should acknowledge the complex nature of NCDs as a societal issue and recognize the contextual differences between countries. Classified as unordered, the complex domain in Fig. 1 identifies non-linear relationships influenced by multiple factors, from which unpredictable patterns can emerge.Reference Van Beurden, Kia, Zask, Dietrich and Rose 17 The decision-making process is thus to ‘probe’ in order to identify these patterns, sense the approaches that can be useful and thus respond to the complex issue.Reference Van Beurden, Kia, Zask, Dietrich and Rose 17 This emphasizes that there is not a ‘one size fits all’ solution for NCD prevention. Strategies should be relevant to the context, and collaboration between sectors is necessary. This results in emergent practice to address the issue.

Fig. 1 Cynefin model by Snowden addresses complex problems in a way that avoids misframing them in a reductionist manner, ultimately to create effective strategies and policies. Source: Cynefin framework Feb 2011.jpeg [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

A case study: the Cook Islands

The Cook Islands is a SIDS located in the Western Pacific region with a population of approximately 15,000. 18 The WHO reports that 80% of deaths in the Cook Islands are attributed to NCDs, 36% of which occur before the age of 60 years. 19 As outlined in Table 1, 29% of the Cook Islands population is diagnosed with diabetes, 65% have insufficient physical activity levels and 22% have raised blood pressure – some of the highest rates not only in the Pacific, but globally. 4 The burden of NCD-related risk factors is also becoming increasingly present in younger age groups. The WHO Global School-Based Health Survey reported that 64% of 13–17 year olds in the Cook Islands were overweight in 2015, 36% of which were classified as obese. 20 In addition, the survey showed that 55% of students had consumed a soft drink at least once a day in the past month. 20 This trend of poor nutritive diets associated with NCD risk is also observed in the adult population, with the WHO STEPS report identifying that 82% of adults consumed less than five servings of fruit and/or vegetables per day. 21 The majority of women giving birth in the Cook Islands are aged between 20–24 years old. 22 While it is estimated that more than 85% of pregnant women have at least six antenatal hospital visits, there is currently limited data on maternal health and nutrition during pregnancy. Thus, the increase in low-quality diets, linked closely with adverse later-life and intergenerational health outcomes, remains a key area of concern for this population.

Due to changing food availability, policies and globalization, the Cook Islands have experienced a transition to diets with low nutritional value.Reference Ulijaszek 23 Typical traditional diets in Rarotonga, the main island of the Cook Islands, were low in fat and high in dietary fibre and complex carbohydrates, including foods such as bananas, breadfruit, taro and seafood.Reference Ulijaszek 23 A two-fold increase in food imports over the latter half of the 20th century influenced an increase in availability of processed food.Reference Ulijaszek 23 Currently, the Cook Islands is 82% dependent on food imports. This has dramatically changed the types of food available to the population and has influenced a shift away from diets based around local foods. 24 Studies have shown that in 1952, 100% of families surveyed had consumed coconut over a period of 7–10 days and 95% ate fresh fish, whereas, in 1996, only 39% had eaten coconut and 37% fresh fish over the same time period.Reference Ulijaszek 23 , Reference Fry 25 , Reference Ulijaszek 26 Thus, broader environmental factors have influenced a change in diet as more traditional foods have been foregone and consumption of imported foods has risen. This trend is common to several other remote communities such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia for which the integration of non-traditional foods has similarly led to a disproportionately high NCD burden.Reference Ferguson, Brown and Georga 27 Nutrition transition, alongside declining physical activity, has been acknowledged as one of the key drivers contributing to obesity and NCD development in the Cook Islands and other vulnerable settings. 21 Therefore, more country-specific research into the impact of early-life nutrition is needed in order to provide an evidence base for health interventions.

A need for more research

In order to create these opportunities to reduce the complex burden of NCDs, adequate evidence is needed to inform guidelines. Currently in SIDS, there is a lack of research focusing on early-life nutrition and DOHaD concepts. Although well-researched in several developed nations, it would be problematic to implement approaches in other settings purely based on this evidence. Researchers have recognized that health prevention strategies cannot be separated from cultural factors specific to the context and the success of interventions may rely on integrating these complex considerations.Reference Airhihenbuwa, Ford and Iwelunmor 28 It is critical that each nation has their own research data available to ensure policies and interventions are contextually based. Failure to do so might result in these complex issues being wrongly viewed within the simple domain as shown in Fig. 1. Treating NCDs as a simple cause and effect relationship that can be dealt with by best practice in any context could be harmful as interventions would likely be ineffective and wasteful of valuable resources. With some of the highest NCD rates in the world, it is critical that early-life nutrition research is promoted in SIDs in order that approaches are specific to the context, based on local evidence and ultimately, effective.

However, there are challenges in small populations, such as those of Pacific SIDS, for research to be recognized as ‘valid’ when sample sizes are small.Reference Etz and Arroyo 29 , Reference Korngiebel, Taualii, Forquera, Harris and Buchwald 30 Traditionally, large sample sizes are sought in order to adequately represent the population of interest and increase statistical power. However, this is not always possible for research within smaller populations that might have a relatively small sample, but which could capture a high proportion of the target population. Some of the most at-risk groups and nations in health statistics are smaller communities, therefore ethically and morally, this research should not be discounted.Reference Etz and Arroyo 29 , Reference Korngiebel, Taualii, Forquera, Harris and Buchwald 30 Strong population numbers can also direct priorities and policies which means that smaller communities are often overlooked.Reference Korngiebel, Taualii, Forquera, Harris and Buchwald 30 As underrepresented, vulnerable groups, it is even more critical that research should be conducted, despite the limitations of sample size. ‘Data borrowing’, from similar, neighbouring groups (as identified by the community themselves), is one method that has been previously suggested to increase statistical power when conducting research in small populations.Reference Korngiebel, Taualii, Forquera, Harris and Buchwald 30 Another avenue could involve pooling several years of data from the target community in order to gain a larger sample size from which to make meaningful inferences. It is clear that different, creative ways are required to increase sample sizes and perhaps redefining what constitutes a valid, vigorous research study is necessary.Reference Etz and Arroyo 29 , Reference Korngiebel, Taualii, Forquera, Harris and Buchwald 30 Therefore, if the NCD burden is to be reduced in high-risk nations such as Pacific SIDS, there needs to be more research to inform evidence-based approaches, acknowledgement of the specific contextual issues and constraints and perhaps a shift in perception of what comprises ‘valid’ research.

Conclusion

SIDS face unique difficulties such as rising impacts of climate change, vulnerable economies and often a double burden of both NCDs and communicable diseases. Particularly, SIDS in the Pacific region have some of the highest rates of NCDs, premature mortality and related risk factors. Despite international recognition of early-life nutrition for later NCD risk and the complex challenges SIDS face, the DOHaD concept continues to be understudied, particularly in the Pacific region. A key challenge to supporting research for these states concerns the prevailing view that small sample sizes, as available due to the small population, may not be regarded as scientifically valid. However, due to the high NCD rates, there is even more reason to conduct health research within these at-risk populations in order to promote contextual-based prevention strategies. It is crucial that research within this area of need is encouraged and supported, which may require innovative ways to increase sample size or changes in perception about what constitutes a valid study. For small states such as the Cook Islands, this could be critical for furthering research of NCD prevention strategies, in order to influence healthier lives for families and future generations.

Acknowledgement

None.

Financial Support

This work was supported by a grant by the Health Research Council of New Zealand grant number 17/479.

Conflicts of Interest

None.