Introduction

Despite the perception of courts as reserved institutions that shy away from the public, scholars consistently find that courts worldwide, particularly justices from national high courts, actively reach out to the public through various forms of off-the-bench communication. For example, justices may embark on extensive public-speaking tours (Black, Owens, and Armaly Reference Black, Owens and Armaly2016) or participate in various media events, including televised interviews (Staton Reference Staton2010; Davis Reference Davis2011; Glennon and Strother Reference Glennon and Strother2019). While judicial communication has become more common in public life, two key aspects of this phenomenon remain unclear: First, what motivates judges to engage with the public? Second, how does judicial communication influence public attitudes toward judiciaries?

Much of the existing literature considers that judges engage with the public to garner support, with experimental evidence suggesting that the public responds positively to judges’ off-the-bench communication (e.g., Krewson Reference Krewson2019). However, two tensions complicate this view. First, the idea that judges communicate with the public to garner its support runs counter to the view that judges are incentivized to avoid public communication, as maintaining distance can preserve a judiciary’s reputation for neutrality and unwavering adherence to the rule of law (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998). Second, the positive effect of this judicial communication on public attitudes toward judiciaries tends to be observed in contexts where courts already enjoy high levels of institutional trust, primarily in established democracies. In contexts where courts lack such trust – for example, in countries that have recently transitioned to democracy – the effect of judicial communication is less clear, as communication with the public can evoke negative associations of judicial repression on behalf of authoritarian rule (Shen-Bayh Reference Shen-Bayh2018). To date, there has been little research explicitly examining either judges’ motivations for communicating with the public or the effects of this communication in non-Western contexts, particularly those where a transition from authoritarianism to democracy has taken place.

To better understand judges’ motivations for undertaking communication in a newly democratic state and to evaluate the effects of this communication on public perceptions of a given judiciary, I build on the literature on judicial behavior and political communication. I argue that judges in new democracies, like those in established democracies, seek to maintain their institutional legitimacy, even if they have traditionally kept their distance from the public. They are especially likely to communicate when their legitimacy is at risk. However, in such contexts, citizens may be accustomed to distancing themselves from the judiciary due to the country’s authoritarian past, which necessitates more effort in communication. I consider that the sophistication of judicial messaging influences the judiciary’s approachability. When communication is crafted in a more understandable and accessible manner rather than in a formal or restrained style, it becomes more effective. I refer to the former as a public-oriented communication strategy. When such an approach is adopted, the public is more likely to receive and process judicial information, thereby reacquainting themselves with the judiciary and promoting a positive attitude toward it.

To evaluate this argument, I leverage a unique judicial reform in Taiwan. The reform took shape in 2017 when the government announced the creation of a “people’s court.” Its main function was to enhance the quality of democracy on the island. To achieve this end, the judiciary – acting as the people’s court – would, among other things, initiate a series of public-outreach programs characterized by both clearly-worded judicial messaging and an active use of social media. The government’s goal of deepening the quality of democracy is understandable, but it is unclear why members of the judiciary would embrace judicial communication and how the resulting communication would influence public attitude. These are the two topics on which I focus in the present mixed-methods study. For the first part of the study, I conduct in-depth elite interviews with members of the Taiwanese judiciary to examine their motivations for communication. For the second part of the study, I use a difference-in-differences design to assess how judicial communication influences public trust.

I present two key findings. First, the judiciary’s adoption of communication rested on the desire of individual judges to defend the judiciary’s reputation through the use of communication characterized by clarity and accessibility. Their efforts, combined with growing public discontent, gradually pressured the judiciary to break its silence and adopt active communication as a national policy. Second, the new style of judicial communication, with its clearly-worded judicial messaging, strengthened public trust in the judiciary: the more people were likely to be exposed to this new style of judicial information, the more likely they were to express higher levels of trust in the judiciary.

This study makes two contributions. First, while much scholarly attention focuses on the legitimacy-enhancing function of judicial communication, my study offers a new perspective by emphasizing simplified and accessible language. Judicial information is often challenging for the average citizen to comprehend, creating barriers to effective communication between the public and the judiciary (Grieshofer née Tkacukova, Gee, and Morton Reference Grieshofer née Tkacukova, Gee and Morton2021). My findings have implications for countries where citizens are skeptical about their judiciary, as lowering the barrier to understanding judicial messages is a prerequisite for justices to communicate and garner support effectively. This approach is also relevant for established democracies, where controversial rulings often face criticism due to misinterpretation. By ensuring clear and comprehensible communication, the judiciary can minimize misunderstandings and improve public perception.

Second, my qualitative findings provide evidence for justices’ motivations for communication. Many judges begin to break their judicial silence when they face public scrutiny and hostility. This finding aligns with existing studies arguing that judges care a great deal about the institutional reputation of their judiciary (Hall Reference Hall2014; Garoupa and Ginsburg Reference Garoupa and Ginsburg2019). The nuance is that judges’ strategy is not about aligning judicial opinions with public sentiment but rather about explaining legal reasoning to the public in clear and accessible language. This finding has implications for protecting judicial reputation, as it suggests that enhancing public understanding of legal reasoning can be a key factor in maintaining trust in the judiciary.

Judicial communication

Courts tend to be less visible to the public than elected governmental officials, whose support depends on votes. Some scholars of judicial legitimacy propose that the judiciaries can enhance their legitimacy through a separation of judges from the public. This separation promotes the public perception that judicial decision-making is impartial and guided by the rule of law (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse1995; Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998). However, more than a few judges consistently and actively engage with the public. For example, research on the US Supreme Court shows that justices make frequent speaking appearances at public events. Between 2002 and 2012, Supreme Court justices took an average of eighty trips per year as a unit (Black, Owens, and Armaly Reference Black, Owens and Armaly2016). With at least some judges commonly engaging in communication, one might wonder what prompts them to pursue this line of activity.

The existing literature on judicial communication provides a simple answer: judges engage in public outreach to maintain the institutional legitimacy of their courts. There are at least two variants of this line of argument. The first line of this argument begins with the assumption that judicial communication is motivated by the desire to uphold institutional legitimacy (Glennon and Strother Reference Glennon and Strother2019). Judges from national high courts, in particular, see public relations as a way to foster the citizenry’s faith in judicial legitimacy: the reasoning behind this is that courts lack the authority to guarantee compliance with judicial decisions, depending largely on a voluntarily compliant public (Caldeira Reference Caldeira1986; Hall Reference Hall2014).

Aware of this dependence, judges use legitimacy-enhancing rhetoric to communicate with the public (Glennon and Strother Reference Glennon and Strother2019). This rhetoric can include arguments about how a judiciary is apolitical and how its decisions are achieved through fair and neutral processes (Epstein and Knight Reference Epstein and Knight1997). For example, in their research on televised interviews of US Supreme Court justices, Glennon and Strother (Reference Glennon and Strother2019) find that a significant portion of these interviews had been dedicated to reinforcing the court’s legitimacy. Some of these justices had emphasized the centrality of the judiciary as a neutral arbiter of the law. On other occasions, justices tried to demonstrate the apolitical nature of decision-making by discussing their jurisprudential philosophies and differentiating them from partisan perspectives.

Although Black, Owens, and Armaly (Reference Black, Owens and Armaly2016) establish that an impressive 75% of US Supreme Court trips were for the purpose of public speaking, the study does not focus on why the justices undertook these trips; instead, they speculate that the public speeches had the chief function of enhancing the legitimacy of the Supreme Court. In follow-up research, Krewson (Reference Krewson2019) uses an experimental approach to examine the effect of Supreme Court Justices’ public speeches, and he finds that judges’ speeches are conducive to enhancing public perceptions. Specifically, Krewson (Reference Krewson2019) finds that law students who were exposed to information about a Supreme Court Justice’s public speech improved their favorability toward the Court and the importance of law in judicial decision-making.

The second part of the discussion on judicial communication revolves around the concept that judges are driven by concerns about the media environment, including the media’s lack of attention to the judiciary or potential misinterpretation of judicial decisions (Spill and Oxley Reference Spill and Oxley2003; Davis Reference Davis2011). The underlying idea is that if justices are interested in enhancing their judicial public relations, they should pay attention to how information about the judiciary is conveyed to the public. An apparent concern for the judiciary is how the media portrays the judiciary, given that the media is the primary source of information on political events (Strother Reference Strother2017). However, when examining the relationship between the media and the judiciary, judges may face two types of difficulties that hinder the dissemination of information.

The first challenge is media inattention. Research indicates that news outlets exhibit a high degree of selection bias, tending to report on eye-catching issues at the expense of important but less dramatic topics (Soroka Reference Soroka2006; Soroka et al. Reference Soroka, Daku, Hiaeshutter-Rice, Guggenheim and Pasek2018). Media inattention can contribute to an uninformed public, with the subsequent consequence of reducing not only the public’s commitment to judicial decisions but also, and in turn, the cost of executive noncompliance with judicial decisions (Staton Reference Staton2010). The second challenge is the possible misinterpretation. Although the press frequently communicates judgments accurately, such as who wins and who loses a case, there is a tendency for reporters to misconstrue jurisprudential rationales – a source of frustration for judges themselves (Davis Reference Davis2011). Existing research in judicial politics suggests that judges use opinion writing to shape public perception; in other words, to craft a self-image for public consumption (Baum Reference Baum2009). The media’s inaccurate reporting on the reasoning of a court or a particular judge underscores why some judges actively engage in communication concerning their rationales in a given case. For this reason, the judiciary adopts public outreach to establish its own information dissemination channel. Simply put, since the media is not an arm of the judiciary, judges are motivated to proactively engage in communication to maximize the dissemination of information.

Overall, while the literature emphasizes different motivations for judges’ participation in communication, there is general agreement that this outreach is primarily geared toward promoting the institutional legitimacy of a judiciary, yet this proposition has not been empirically confirmed. Therefore, I propose the following hypothesis for empirical examination.

Hypothesis 1: Members of the judiciary engage in public-oriented communication to foster an environment conducive to maintaining institutional legitimacy.

Judicial communication and public perception

If members of a judiciary are motivated to engage in communication, how does it influence public perception of the judiciary? Existing studies have explored how judges’ on-the-bench activities, such as legal-opinion writing (Baird and Gangl Reference Baird and Gangl2006), and off-the-bench activities, such as public speeches (Krewson Reference Krewson2019), influence public attitudes toward the judiciary. While the influence that judicial communication has on public attitudes may vary according to its form, there seems to be a consensus that judicial communication is positively associated with favorable public perception of the judiciary.

According to the existing literature, there are two possible pathways by which judicial communication influences public views of a judiciary. The first pathway centers on visibility: the more visible a judiciary’s engagement in public-oriented communication is, the more positive the public perception of the judiciary will be. This concept is similar to previous research findings from studies on high courts in the United States and Western European countries, suggesting that public awareness of a judiciary bolsters public support for the courts (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998). In simpler terms, “to know courts is to love them” (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998:344). A central aspect of visibility, I argue, is accessibility.

The second pathway by which judicial communication influences public views of a judiciary centers on rhetoric: many judges who engage in communication focus rhetorically on the apolitical nature of courts and on the fair, neutral processes of judicial decision-making (Tyler Reference Tyler1990; Tyler and Rasinski Reference Tyler and Rasinski1991; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003). Research on US courts highlights the crucial role of rhetorical style in communication, particularly when a judicial decision runs counter to public sentiment. In such an instance, judges writing an opinion may use the rhetorically appealing tool of clear language to justify their decision and frame their decision-making in a manner that underscores the centrality of the law (Baird and Gangl Reference Baird and Gangl2006). The aim here would again be to strengthen public trust in the judiciary.

The above reasoning suggests that judicial communication, when it adheres to the two pathways of visibility and rhetoric, can cultivate a citizenry that is aware of, understands, and trusts its judiciary. The existence of the two pathways seems to be taken for granted in the contexts where the above studies were conducted (i.e., established Western democracies with high judicial independence). However, in countries transitioning to democracy, additional considerations are necessary. This point is important because individuals in such countries may harbor negative perceptions about the judiciary. Consequently, a judiciary with high visibility may evoke in the citizenry a negative reaction rooted in memories of pro-authoritarian judicial propaganda. Garoupa and Magalhães (Reference Garoupa and Magalhães2020) remind us that public awareness of a judiciary and public trust in the judiciary might vary from one context to the next, especially with respect to the institutional dependence or independence of the judiciary. In this paper, I propose that judiciaries in new democracies must invest extra effort into building public trust through judicial communication, and that this communication must be oriented toward the public in ways that effectively acquaint the people with courts’ newly productive roles in a democratic society.

Effective judicial communication, social media, and judicial trust

To explore how a judiciary’s communication strategies foster public trust, I turn to the literature on political communication. Existing literature suggests that there are two broad strategies that political actors can employ to facilitate effective communication with the public. The first strategy emphasizes information clarity. Political actors may simplify their messages to facilitate communication with a broad audience. For example, research on parliamentary communication demonstrates that legislators tend to reduce the linguistic complexity of their speech to promote effective communication with their constituents. Spirling (Reference Spirling2016) finds that British Members of Parliament (MPs) used simpler linguistic expressions to appeal to a broader electorate after a period of governmental reforms. Similarly, Lin and Osnabrugge (Reference Lin and Osnabrugge2018) find that German MPs integrated simpler wording into their parliamentary speeches in a bid to connect with the electorate directly and effectively. The guiding principle here is that policy statements often contain technical terms, making it difficult for average citizens to understand. To promote representative-constituency linkage, politicians shed these terms in favor of simpler wording that conveys messages to voters in everyday language, a particular political agenda, or a process.

Research suggests that this same communication strategy – information clarity – surfaces in judicial contexts. In their study of the US Supreme Court, Owens and Wedeking (Reference Owens and Wedeking2011) observe that justices tended to write more clearly when crafting dissenting opinions than when crafting majority opinions. They further note that the most clearly worded majority opinions emerged from minimum-winning coalitions.

The second communication strategy adopted by political actors focuses on accessibility. In today’s digital world, accessibility often translates into the adoption of Internet platforms as avenues for the dissemination of information. Social media platforms, in particular, have become an indispensable source of information exchange for citizens seeking to receive and share news and for politicians seeking to control the various narrative strands in this public engagement. One key advantage lies in the immediacy and directness of communication, allowing politicians to share their messages instantaneously and interact with citizens in real time. Social media platforms serve as dynamic spaces where politicians can humanize their image, offering glimpses into their personal lives and showcasing authenticity (McGregor Reference McGregor2017; McGregor, Lawrence, and Cardona Reference McGregor, Lawrence and Cardona2017). While different studies focus on the various roles played by social media in political communications, the general view is that social media constitutes a powerful tool with which politicians can disseminate both general and targeted messages to select audiences.

A key point that we can reasonably derive from the research on these two communication strategies is that the clearer and more accessible a public-oriented judicial message is, the more likely the public will be to receive, understand, and even concur with the message. Consequently, we should expect to observe differences in public attitudes toward a judiciary when it prizes clear and accessible messaging over unclear and inaccessible messaging. Hence, I propose the present study’s second hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: Clear and accessible public-oriented judicial communication is positively associated with public trust in the judiciary compared to a more reserved communication approach.

The case of Taiwan

I test my theoretical expectation by leveraging a judicial reform in Taiwan that allows me to examine the causal effect of communication on attitudes toward courts. This particular judicial reform is appropriate for testing my theoretical claim because it includes a major change in how the judiciary communicates with the public, especially regarding their adoption of social media. In 2016, the Taiwanese government launched preparatory meetings for the National ConferenceFootnote 1 on Judicial Reform, which aims to improve the public’s trust in the judiciary by implementing revolutionary changes in the judicial system. Following the conclusion of the National Conference in 2017, the Judicial Yuan, the judicial branch, created a special task force called the Judiciary-Society Dialogue Enhancement Group, whose function was to improve judicial trust by enhancing the communication between the judiciary and the public. On the advice of the task force, the Judicial Yuan implemented a series of communication strategies that significantly improved the flow of information from the judiciary to the public.

It is important to note that the Judicial Yuan is Taiwan’s highest judicial authority, overseeing the entire court system, including the Supreme Court, High Courts, and District Courts. At its core is a designated Constitutional Court, which is responsible for interpreting the Constitution and providing uniform legal interpretations. The court is comprised of fifteen Grand Justices, nominated by the president and confirmed by the legislature, each serving an eight-year term. The Chief and Vice Grand Justices also serve as the president and vice president of the Judicial Yuan, respectively, giving the leadership of the Judicial Yuan a dual role as both judges and administrative officials. Therefore, when the executive branch convenes a National Conference on judicial reform, the leadership of the Judicial Yuan plays a crucial role in managing judicial administrative tasks and shaping the agenda for judicial policy.

Background of Taiwan’s 2017 judicial reform

In the late 1980s, Taiwan began transitioning from authoritarianism to democracy – a transition that culminated, in 1996, in the country’s first direct presidential elections. However, during the roughly four decades preceding this transition, Taiwan was governed by the authoritarian Nationalist Party, known as the Kuomintang (KMT). Although the KMT had ruled much of mainland China following the defeat of imperial Japan in 1945, communist forces in China quickly routed the KMT armies and forced the KMT government and its supporters to relocate, in exile, to Taiwan in 1949. To rule on this island, the KMT government relied on the judiciary to legitimize its rule and a vote-buying form of clientelism to mobilize voters in local sham elections. Under these circumstances, the judiciary exercised little independence and, thus, was deployed as an instrument of governance in support of the KMT rulership. For example, the judiciary masked the corrupt activities of clientelist elites and provided legal cover to the KMT government for its vote-buying schemes (Wang and Kurzman Reference Wang and Kurzman2007).

At the start of the 1990s, Taiwan was gradually democratizing, and as part of this process, the judiciary was gradually gaining independence from the executive branch. This process of independence was marked by two movements: The first, occurring in 1993, was led by reform-minded lower-court judges who demanded changes to case-assignment protocols and personnel control – two channels through which the KMT had traditionally imposed its authoritarian rule on the judiciary. The second movement was initiated in 1998 by a group of maverick prosecutors who insisted on investigating corruption cases and rejected any interference from their superiors – these investigations later led prosecutors to organize coordinated acts of resistance against undue political influence (Wang Reference Wang2006).

As a result of these movements, judges and prosecutors successfully reduced political influence on the judiciary, leading to judicial independence post-1990s. According to V-dem data, the indicator for Taiwan’s judiciary constraint on the executive, which ranges from 0 to 1, rose from 0.59 before 1990 to 0.83 by 2000, and the figure remains above 0.8 as of 2024, indicating sustained independence. Despite the judiciary’s high degree of independence, public trust in the institution remained low: a 2017 national survey revealed that 58% of respondents did not trust judges.Footnote 2

Amid low public trust in the judiciary, demands for reform followed. In response, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which defeated the KMT in presidential elections in 2016, began enacting reform. During the 2017 National Conference, the DPP President Tsai asserted that Taiwan must restore judicial trust through “openness, transparency, and public participation.” To embody these principles, the leadership at the Judicial Yuan invited participants from various social groups to committees, including representatives from the Judicial Reform Foundation, academics, and practitioners such as representatives from lawyer, prosecutors, and judges. The National Conference report reiterated that trust in the judiciary is crucial for a strong democracy.

Changes in judicial communication

One of the most significant changes stemming from the 2017 judicial reform involved the judiciary’s communication with the public. Before the reform, the judiciary maintained a more restrained approach in its interactions with the public. This pattern was due to an established norm stipulating that “judges remain silent”: judges should communicate with the public primarily through their written legal opinions and, outside the judiciary, should maintain a reserved stance. For this reason, judges seldom appeared in public during the pre-reform era, even after Taiwan had democratized. Although the judiciary has a website containing information on cases, jurisdictions, and members, the pre-reform judiciary rarely publicized such information. The primary channels for the judiciary’s dissemination of information to the public were occasional press releases and news coverage. However, journalists quite often deemed the judiciary unworthy of news coverage, and when judges did make headlines, it was typically in connection with controversial issues, like cases involving political scandals. In public appearances, judges would use complex legal terms to describe nuanced legal ideas, thereby hampering the ability of average citizens to comprehend the messaging. In short, before the 2017 reform, neither individual judges nor the judiciary made a tangible effort to bridge the gap between it and the public. This pattern of reticence likely contributed to the widespread public perception of distance and non-transparency.

After the 2017 judicial reform, the judiciary shifted its communication approach from the aforementioned reserved manner to a much clearer and accessible one. A central objective of this judicial reform was to make “the values and principles of justice, as well as the spirit of the rule of law, become visible, audible, and accessible to the public” (Lin, Hung-Ming Reference Lin2017). To achieve this objective, the judiciary modernized its communication by three strategies: first, actively engage the public across various media platforms; second, simplify complicated legal language; and third, promptly address any attacks on the judiciary. The Judicial Yuan instituted two internal organizational divisions to promote communication: (1) the Judiciary-Society Dialogue Enhancement Group (known as the Dialogue Group) and (2) the Spokesperson Office of the Judicial Yuan.

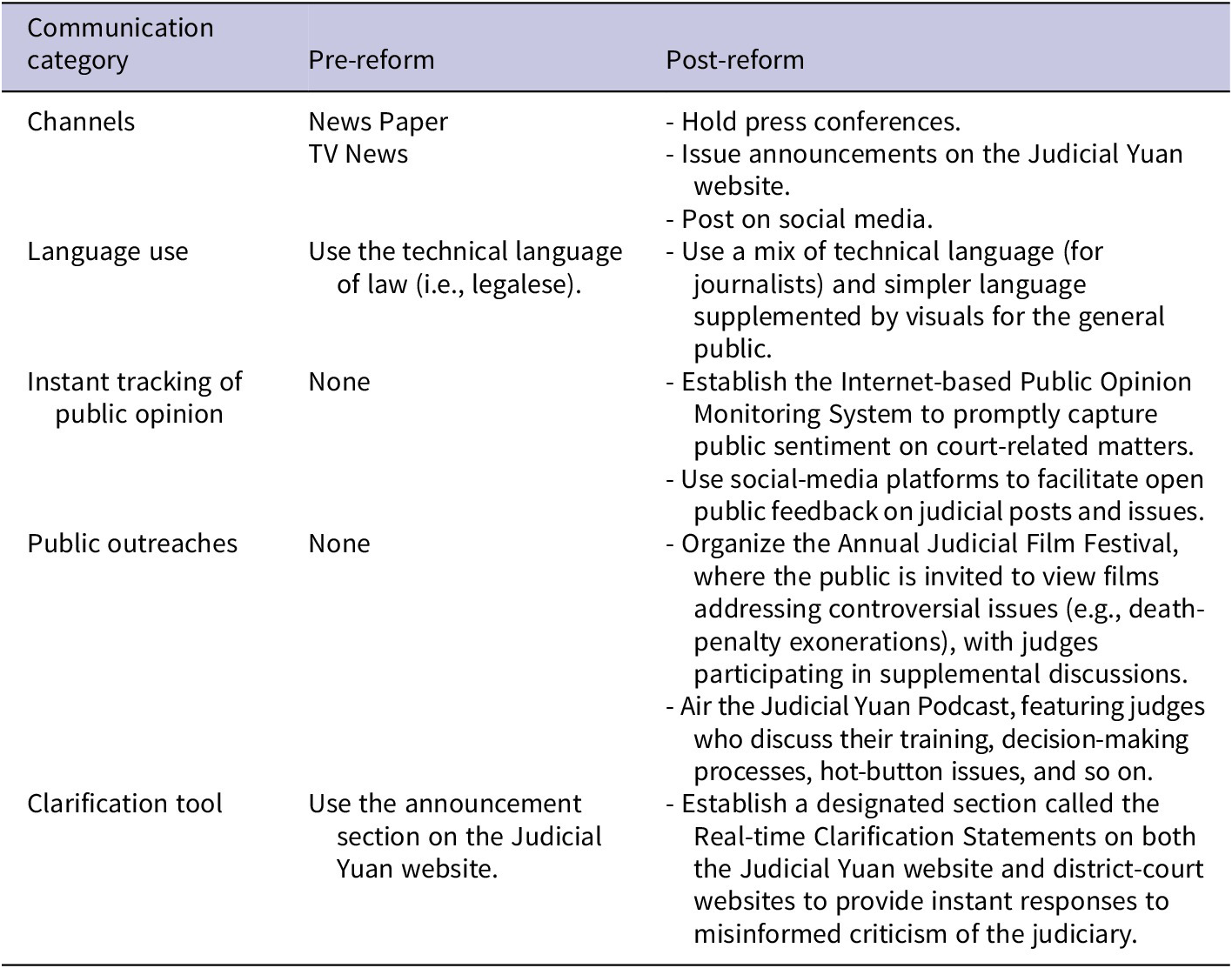

Established in 2017, the Dialogue Group, which has since served as a specialized task force dedicated to improving communication through innovative programs, pursued six initiatives that heavily rely on social media: (1) a redesigned Judicial Yuan website featuring an inquiry-submittal section for the public and a section designated for up-to-date clarifying news; (2) an Internet Information Response Team tasked with studying public opinion and swiftly responding to misinformation; (3) official Facebook and Instagram pages for the Judicial Yuan; (4) an account on the messaging app Line for the dissemination of information to followers; (5) a podcast channel that discusses topics related to law and the judiciary; and (6) collaborations with movie producers to create documentaries about individuals in the judiciary and to hold annual judicial film festivals. More specific examples of differences between the pre- and post-reform communication approach are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of Judicial Communication Approaches Pre- and Post-Reform in Taiwan

The Judicial Yuan’s adoption of social media has transformed judicial communication in two ways: greater clarity in the form of simplified language and greater accessibility in the form of an expanded online presence. Regarding clarity on social media, the judiciary now uses shorter, more comprehensible text supplemented with visual aids to attract a broader audience than had existed during the pre-reform era. Regarding accessibility, judicial posts can be read and shared by citizens and cited by news media, thus amplifying the reach of clearly worded messaging. An interesting exponent of this effort is the Internet Information Response Team, which combats misinformation with accessible clarifications. The team detects misinformation by harnessing the Internet Public Opinion Monitoring System: it collects web pages containing keywords related to the judiciary, particularly concerning controversial issues, which often give rise to inaccurate sensationalistic assertions.

To illustrate in concrete terms how the post-reform judiciary has increased the clarity and the accessibility of its messaging, I detail how the Judicial Yuan announces constitutional rulings. Typically, in the lead-up to a constitutional ruling, the Judicial Yuan begins its coverage of the event by posting a live-stream preview on social media, informing the public of the following day’s ruling. On the day of the ruling, various websites associated with the judiciary release three types of information. First, the Constitutional Court website posts a publicly accessible archived document detailing the ruling. The archive features tabs for access to the details (e.g., a “Cause of Action” tab or an “Opinion Brief” tab). Second, the Spokesperson Office issues a succinct one-page press release outlining the Constitutional Court’s decision and lists the justices involved in the majority and dissenting opinions (if any). Third, on its Facebook account, the Judicial Yuan posts a simplified version of the ruling tailored for public outreach. Figure 1 presents screenshots of a post concerning an actual 2020 Constitutional Court ruling.

Figure 1. Example of How the Judicial Yuan Uses Social Media to Introduce Its New Rulings.

Overall, these three types of information preceding and following a Constitutional Court ruling cater to different audiences with varying levels of language sophistication. The comprehensive archived document on the ruling and the one-page press release use formal language for scholars and journalists, whereas the social-media posts use simplified language to ensure that citizens without a legal background can understand the general contours of the ruling. The Facebook post uses concise, straightforward language, as shown in Figure 1(a) (“Can the state enforce compulsory blood tests for drivers involved in traffic accidents?”) and in Figure 1(c) (“infringe upon personal privacy”). The Facebook post also includes a visual aid presenting headshots of the majority- and the dissenting-opinion justices, as shown in Figure 1(b).

To combat misinformation, the Judicial Yuan established the Spokesperson’s Office in 2020. It reports directly to the President of the Judicial Yuan. Its primary mission is to monitor public opinion, address concerns promptly, manage media relations, disseminate news on judicial policies, and coordinate communication across lower-level courts. In 2022, the Judicial Yuan created the Public Information Department, resulting from a merger between the Dialogue Group and the Spokesperson’s Office. This new department now handles all responsibilities previously assigned to the two entities.

Simply put, the post-reform judicial communication shows that the Judicial Yuan takes both the public and media seriously. In contrast to the highly reserved pre-reform communication, the new approach shows a clear shift toward openness and improved public engagement through better accessibility and clarity of information.

Data, methods, and results

Overview of studies

The present study rests on a mixed-methods research design and consists of two studies: first, in-depth elite interviews to explore the motivations behind individual judicial actors’ embrace of communication. Second, a difference-in-differences design compares the public’s digital usage habits affected differently by the 2017 judicial reform to evaluate the impact of judicial communication on public trust.

Study 1: Why judicial communication?

Tracing the emergence of judicial communication

Before investigating why the judiciary engages in public-oriented communication, I first trace its historical evolution. As I will demonstrate, judicial communication first emerged not as a national policy but as an unofficial effort undertaken by a handful of individual judges who independently formed several autonomous groups that expressed their judicial and legal views on Internet-based platforms.

The first appearance of public-oriented judicial communication took place in 2014, with the launch of the online platform “Let’s Read the Verdict Together.” A self-labeled legal-education platform, it “translates” court verdicts from the complicated legalese of courts to the plain language. The platform quickly garnered significant attention: within two years of going live, it boasted more than 100,000 subscribers. Since then, whenever there is a high-profile judicial decision or constitutional ruling, many members of the public and scholars shared and posted explanations from “Let’s Read the Verdict Together” on social media. Later on, the author of “Let’s Read the Verdict Together” launched another new page called “One Minute Law,” providing even more simplified explanations of legal matters by summarizing them in just one minute.

The second period of judicial communication took place between 2016 and 2018, in and around the 2017 reform. This period saw a noticeable surge in the emergence of online resources dedicated to communication. Perhaps best described as a “marketplace of ideas,” these channels, web pages, and social media accounts offered a greater diversity of perspectives than had ever been available in judicial discourse. There were two common forms of communication: op-eds written by judges for major news outlets (many of which were online) and social media channels created by organized groups of judges. Several judges began voicing their opinions in op-eds. Although these individuals became familiar names in the media, public outspokenness of judges remained uncommon because most judges, even those in favor of reform, recoiled at any public-oriented communication that would bring them unwanted attention. As a result, many of these judges opted for a lower-profile approach, which led to the second common form of communication at the time, social media channels created by organized groups of judges. By sharing their views through organized groups, member judges could maintain their anonymity. Four judge-led public outreach platforms emerged during this time: the Association of Judges (2015), Judges for Judicial Reform (2016), Daily Life in the Courtrooms of Cat Judges (2017), and Judges Overturning the Judiciary (2018).

A closer look at these groups reveals that they represented various communities within the judiciary, each aiming to convey a unique message not necessarily congruent with the messaging of the other groups. Take, as an example, the group known as Daily Life in the Courtrooms of Cat Judges: it was created in 2017 by junior judges who shared their work realities and thoughts on legal issues in whimsical posts on a social media account. It introduces itself as a modern story of introspective judges who engage with society while unraveling legal complexities. Many of the posts feature cartoon art to illustrate the text-based accounts of courtroom events. The name “Cat Judges” reflects the judges’ love of cats and dogs, in an amusing contrast with the stereotype of “dinosaur judges.” Diverging sharply in tone and content from Daily Life in the Courtrooms of Cat Judges was the group Judges Overturning the Judiciary. Formed in 2018 by mid-career judges, it takes a critical stance, highlighting areas in the judicial system that need improvement, such as judicial overload.

The third period of judicial communication, as described earlier in this paper, centered on the government-driven reform, which initially took shape in 2017 and evolved over the next several years. The Judicial Yuan, having embraced the idea of public-oriented communication at the 2017 National Conference, began to pour resources into communication efforts. The resulting national policy pivoted on the desire to restore public trust in the judiciary. President Tsai highlighted that the judiciary must end its decades-old commitment to silence to achieve this goal: “The practice of ‘Judges Remain Silent’ is no longer suitable for today’s democratic society.” She went on to emphasize the need for a public-oriented form of judicial communication that would use a technical-to-vernacular translation mechanism.

Following the conference, the Judicial Yuan established the Judiciary-Society Dialogue Group to take the initiative. Early on in the process, senior judges understandably had little sense of how they should engage in such communication. To make it happen, Grand Justice Tzong-Li Hsu and Tai-Lang Lu, the then president and secretary-general of the Judicial Yuan, respectively, invited two segments of the judicial community to join the Dialogue Group: first, junior judges who, in some cases since 2014 had accumulated considerable experience in public outreach; and second, young administrative staffers from diverse backgrounds. Thus, a deputy director of the Dialogue Group was also a leading contributor to the Cat Judges social media account. This fact suggests that old-school elements within the judiciary were open-mindedly keen to learn from the recent experiences of public-oriented, technologically savvy junior judges.

Despite this open-mindedness, the Dialogue Group’s earliest initiatives reveal at least a shadow of judicial reticence. When the Judicial Yuan began contemplating the reform agenda, most considerations were confined to formal announcements on government websites or messaging apps. Officers deliberately refrained from using social media such as Facebook and Twitter because, from the conventional perspective, government websites and messaging apps offered a more controlled environment in which the public could leave messages or submit inquiries without broadcasting them to the world. This communication approach afforded the Judicial Yuan considerable latitude in its communications. Simply put, many traditional judges preferred this mode of communication as it was cautious.

Around 2019, the judiciary transitioned from hesitancy to decisiveness, embracing social media in the form of a Facebook page, an Instagram account, a podcast channel, and, topping it all off in 2020, the Internet-oriented Spokesperson’s Office. Through these and other resources, the Judicial Yuan grew more adept at articulating complex legal ideas in clear, plain language, drawing the public closer to formal and informal aspects of the judiciary, and combating misinformation.

Empirical strategy

Because much of the judicial decision-making process is veiled from the public, I employ elite interviews to identify the motivations behind individual judges and the Judicial Yuan adopting communication. Interview data were collected by meeting with judges and judicial officers from different levels of courts to understand when and why they and the judicial branch adopted communication. Interviews were conducted in Mandarin and in Taiwan.

I selected interviewees based on their experiences related to judicial communication. Interviewees needed to satisfy one of three initial criteria: the interviewees needed to have (1) experience in the Dialogue Group, (2) experience engaging in communication on behalf of the judiciary, or (3) knowledge of the 2017 National Conference, particularly with respect to its role in the creation of the Dialogue Group. However, as my interviews progressed, I learned that other actors had been playing roles in the Judicial Yuan’s development of communication. Among these actors were members of the Spokesperson’s Office at the Judicial Yuan and members of various judge-organized groups focusing on public outreach. Therefore, I reached out to them as well.

To identify potential interviewees, I relied on a snowball sampling process. At the start of this process, I contacted three Taiwan-based friends with connections with the judiciary: a senior professor, a former judicial officer, and a former judge. I contacted the former judicial officer first, expressed my intention to understand the development of judicial communication in Taiwan, and asked if she knew anyone working in the Dialogue Group. She generously helped connect me with a deputy director of the Dialogue Group, thus initiating the snowball sampling process. Soon after, the other two friends introduced me to judges who either worked at the Dialogue Group or the Spokesperson’s Office.

The snowballing process is crucial because judicial officers and judges form a very closed group. Their contact information is confidential, making it difficult to reach them directly. Therefore, gaining access often requires peer introductions. For example, after interviewing the deputy director of the Dialogue Group, I asked him to introduce me to his predecessor. I relied on interviewees to make these inquiries on my behalf. Once a prospective interviewee agreed, I received their contact information, such as an email address or Line handle. With their consent, I could then proceed with arranging the next interview.

When it came to scheduling interviews, judges in Taiwan operate much like professors with set teaching schedules. Judges often have trials scheduled on specific days of the week and days without trials that they use for studying precedents and writing legal opinions. Therefore, I typically asked them if I could meet them at their office on days free of trials. For this study, I visited courts in different locations, including the High Court and Supreme Court in Taipei, the capital, district courts, and branches of the High Court in the central and southern areas of Taiwan. The interviews usually lasted about 1.5 hours and were recorded.

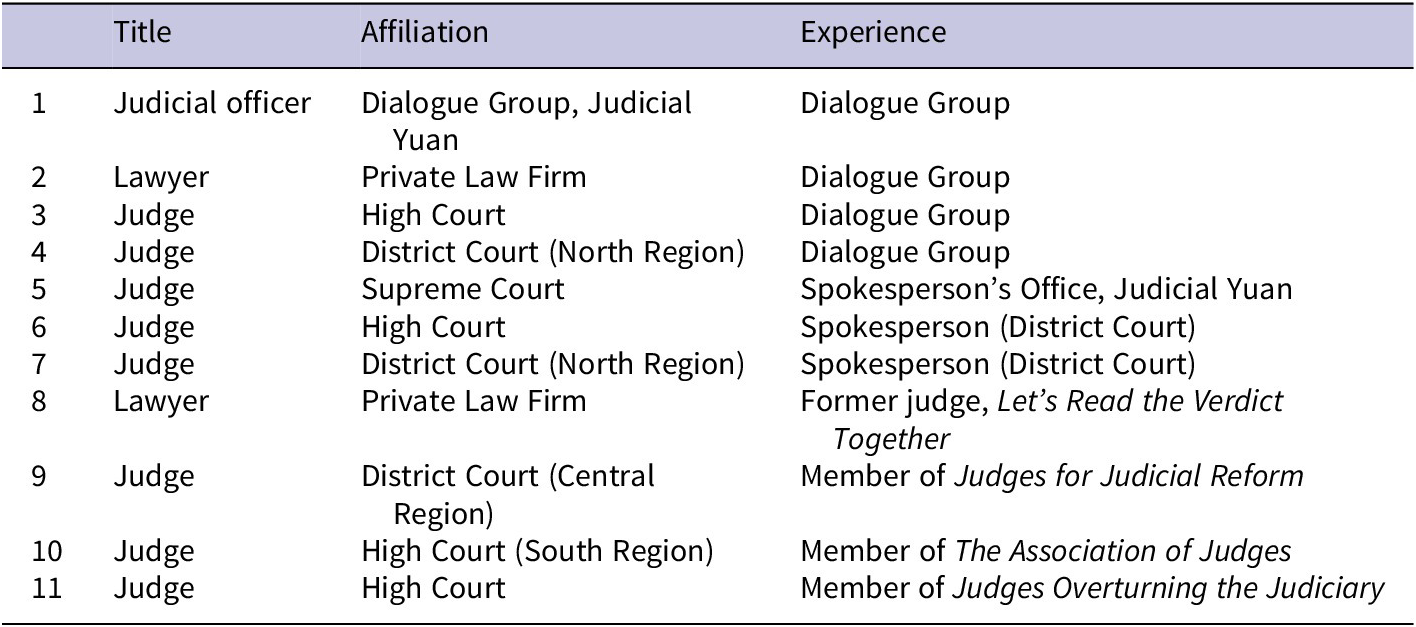

Between the fall of 2023 and the spring of 2024, I conducted in-depth interviews with eleven legal professionals: two lawyers, eight judges, and one judicial officer from the Judicial Yuan. Table 2 summarizes the backgrounds of the eleven interviewees.

Table 2. Interviewee

My goal is to test the hypothesis that members of the judiciary are motivated by safeguarding the legitimacy of the judiciary. If so, the empirical implication would be that these judicial actors would have been initiating communication upon perceiving a threat to the judiciary’s image. Therefore, I focused the interview questions on two topics: the timing of their initial engagement in communication and the self-ascribed motivations underlying this engagement. Two additional topics I covered extensively in the interviews were the background of the Judicial Yuan’s adoption of communication and their strategies. My interview questions were tailored slightly to each interviewee, as roles in the judiciary can vary. Throughout this process, I looked for similarities and differences between their accounts.

Interview findings

Judicial politics scholars have long pointed out that the judiciary differs from the elected branch of government in its relation to the public. For elected politicians, the desire to maintain good public relations through communication is intuitive, as dominating the ballot box constitutes the primary incentive for being responsive to the public; in contrast, judges, not being elected officials, may not share the same inclination to engage with the public. For this reason, judicial actors’ incentive for engaging in communication remains less evident.

Across my interviews, most judges stated that, at first, they considered engaging in public communication unthinkable. This response makes sense in light of the previously discussed institutional norm known in Taiwan as “Judges Remain Silent.” This norm does not mean that judges should be completely mute; rather, its original definition suggests that judges should not comment on ongoing cases (Code of Conduct for Judges, Number 17). Over time, the norm has been interpreted to mean that judges should communicate with the public primarily through written legal opinions and that, outside the realm of the judiciary, judges are expected to maintain a more reserved stance.

As I discussed in greater detail above, this norm no longer holds sway over the judiciary. Over the past decade, judicial actors have become far more active in their public-oriented communication. A consensus I noted across my interviews is that the shift from judicial reticence to judicial openness has been driven by a desire to defend judicial reputation. My interviewees frequently mentioned two specific incidents that threatened this reputation: first, the stigmatization of “Dinosaur Judges” following the White Rose Movement in 2010, and second, the barrage of attacks targeting judges before the 2017 National Conference. Notably, several judge-initiated communication platforms emerged on the heels of these two incidents.

The first incident centered on the White Rose Movement, a significant social campaign that arose in 2010 in response to perceived injustices within the judicial system. The movement gained momentum after a controversial court ruling on a case involving the alleged sexual assault of a six-year-old female minor: the court’s decision was criticized for lacking an empathetic understanding of the victim’s situation. In that ruling, the court determined that the defendant had not violated the will of the young girl, sparking public outrage that evolved into the White Rose Movement. It initially gained traction online, gathering 300,000 signatures on a petition calling for the removal of incompetent judges, and later extended to a mass protest in front of the Presidential Office. The movement is named after the white roses carried by protesters, symbolizing the innocence of minors who are victims of sexual assault. At that time, the public and journalists coined the term “dinosaur judge” to mock those members of the judiciary whose rulings rested on outdated perspectives: it was these judges who, according to protestors, needed to be removed.

As described by my interviewees, the White Rose movement and the emergence of the pejorative label “dinosaur judges” were pivotal moments that convinced them and many of their peers to break away from judicial silence. This movement was unique owing to its bipartisan nature. Unlike the 1990s, criticism of court rulings in cases involving corrupt politicians had revealed political divisions, often along the fault line separating the traditionally authoritarian holders of power, the KMT, and the opposition party, the DPP: when judges ruled KMT politicians corrupt, their supporters criticized the judges for politicizing the issue; the same occurred when judges ruled DPP politicians corrupt. As described by one interviewee: “The White Rose movement marked the first instance where society expressed its frustration with the judiciary in a non-partisan manner. It significantly impacted our [judges’] morale and placed immense pressure on individuals within our profession.”

As the stigmatization of “dinosaur judges” intensified, a few judges who regarded it as misguided began to consider communicating with the public. The launch of “Let’s Read the Verdict Together” was the first unofficial response to the attack on the judiciary. The author of this platform is a young judge who initially remained anonymous due to the low-key culture in the judiciary. He later shifted professional directions, leaving his judgeship to run a law firm. Now outside public office, he felt more comfortable shedding his anonymity. In my interview, he explained that the White Rose Movement and the stigmatization of so-called “dinosaur judges” had motivated him to communicate. “I had just become a judge not long before the White Rose Movement erupted. As a young judge, I felt that there were some misunderstandings about us in society. All I’ve been able to do in response is to articulate court decisions clearly and to let the public judge [each decision] for themselves…”

Similarly, several judges stated that the White Rose Movement had been the first event to instill in them a sense that the public misunderstood the judiciary. The second pivotal moment interviewees frequently cited as a major factor in their decision to break silence was a barrage of attacks against the judiciary in the months preceding the 2017 National Conference. By 2016, various calls for reform had already surfaced in activist segments of Taiwanese society. Voices, particularly from the Judicial Reform Foundation, consisting predominantly of lawyers, emerged as the primary source of criticism targeting judges. According to one interviewee, judges felt that they had become “the objects of judicial reform rather than its initiators.” Many judges felt uneasy about this dynamic and argued they should have a voice in the conversation and a role in shaping the reform agenda.

As with the White Rose Movement, the criticism of judges leading up to the 2017 National Conference motivated judges to regard reticence as a liability and judicial openness as a tool for good. For example, in response to my questions about their initial motivation to engage in public outreach, one interviewee, one of the authors of “Judges for Judicial Reform,” cited a desire to reduce public misperception through communication. “…with the label of “Judges Remain Silent” hanging over them. Judges hope to handle each case well and to explain their decisions persuasively. However, understanding a court decision requires a certain threshold of knowledge….People lacking it may start attacking [court decisions] without fully understanding the legal reasoning [behind the decisions].”

In line with the above views, several contributors to the “Cat Judges” posted a statement that their chief reason for communication was to reduce misunderstandings:

Because of their strict adherence to this principle [the “Judges Remain Silent” norm] and their minimal interaction with the media, cat judges were often misunderstood and misrepresented. The repeated circulation of misinformation led to misconceptions about the judiciary…. However, times are changing, and cat judges are adapting. How we can adjust the “Judges Remain Silent” principle in ways that forge a connection between the judiciary and the outside world has become an important issue…

This observation aligns with my expectation that judges’ initial engagement in communication has been driven by a desire to protect the reputation of the judiciary. This is further evidenced by the timing of judges’ voluntary engagement, which occurred before two key moments: when members of society criticized judges as being “dinosaurs” and when they became the focus of reform efforts. Their response, as reflected in the content they presented on their platforms, was simply an attempt to explain legal reasoning and the role of judges to the public.

In line with their motivation to protect the judiciary, my interviewees cited a similar motivation: a desire to protect the information environment. When the Judicial Yuan first created the Dialogue Group, judicial officials were hesitant about turning to social media to get the message out. This hesitation stemmed from the distinct challenges posed by social media. Its immediate and dynamic nature was a source of concern for judges. One interviewee highlighted that certain individuals within the judiciary genuinely worry about potential cyberbullying if the judiciary becomes actively involved in social media. “We were worried that things can easily escalate once you dive into it [the world of social media]. Any post or any statement could go viral. Once you enter such a platform, you might be inviting a lot of criticism.”

However, throughout my interviews, there is a shared concern about social media becoming a new battlefield. Judges expressed that the media has not been entirely favorable to them, and the misinformation disseminated on social media seems to bother them very much. To prevent the spread of misinformation online, one prominent action taken by the Judicial Yuan is establishing a team capable of promptly responding to misinformation. The judiciary set up an Internet Public Opinion Monitoring System, which sifts through news websites, forums, and social media pages in search of keywords related to the judiciary. Once an instance of misinformation is identified, the judiciary will take action to clarify if it is being misunderstood. One interviewee stated: “If we face an onslaught from the populism that arises on social media platforms, we have a right to respond to it with an equivalent amount of force.” One interviewee emphasized that the judiciary acknowledges the inevitability of using social media. Specifically, they aim to use social media properly to provide accurate information and promptly address any misinformation.

The establishment of a Spokesperson’s Office in 2020 is further evidence of the judiciary’s determination to combat misinformation. The mission of the Spokesperson’s Office is to reclaim control over the discourse in the unfriendly media environment and effectively convey messages from the judiciary. One interviewee who formerly worked at the Spokesperson’s Office revealed that their office would routinely attend weekday morning meetings with the President and Vice President of the Judicial Yuan to discuss public sentiment. During these sessions, staff prepared summary reports on public opinion as gathered from assessments of relevant trending Internet topics. Discussions focused on identifying potential misinformation circulating online. If they decided to issue a clarification announcement, responses needed to be made quickly, typically before 10:30 a.m., to ensure coverage on the noon news.

In sum, my interviews reveal that the core motivation behind their adoption of communication lay in their desire to defend the judicial reputation and, hence, to restore public trust in the judiciary. In many cases, the actors’ initial engagement in this communication reflected their personal initiative, not a directive from the Judicial Yuan. Indeed, the interviews suggest that these personally initiated efforts, combined with the growing pressure of public discontent, not only preceded by several years but also laid the groundwork for the Judicial Yuan’s eventual decision to break its silence and to embrace communication as a national policy. A further finding from the interviews is that judicial actors who were key contributors to the early extra-judiciary public outreach either later worked for or served as consultants for the Judicial Yuan’s official communication program. In short, judicial actors’ early informal endeavors in communication rested on a desire to protect the judiciary’s reputation. They played a pivotal role in the judiciary’s subsequent adoption of communication, in which many of these same actors were participants, still motivated by a commitment to shielding the judiciary from harmful misinformation.

Study 2: Examining the effect of judicial communication

Data and measures

To examine the effect of judicial communication on the public’s trust in the judiciary, I use 2006, 2010, 2014, and 2018 data from the Asian Barometer Survey (ABS) combined with the 2021 survey data from the Taiwan Election and Democracy Studies (TEDS). Both the ABS and the TEDS are nationally representative surveys involving respondents aged 18 years and older. I focus on these five waves because they include common questions on judicial trust, and measure respondents’ digital usage habits. Most importantly, the time range of the five waves includes the period before and after the judiciary initiated a new style of communication.

My hypothesis requires an outcome variable that measures trust toward the judicial branch. My dependent variable, Judicial Trust, captures the extent to which respondents report their trust in the judiciary. This variable is based on a survey question that asks respondents to indicate their levels of judicial trust. It is coded on a scale from 1 to 4, where higher values indicate a higher trust in courts.

To capture judicial communication, I use a binary variable, Post-Reform, which equals 1 if respondents were in the post-judicial reform era and 0 if the respondents were in the pre-judicial reform eraFootnote 3. Digital Usage Habits is a binary variable that measures the difference in the intensity with which judicial communication is consumed. It equals 1 if respondents self-identified as frequent Internet users and 0 if they identified themselves as seldom using the Internet and not having a social media account. As I discussed, I do not expect the effect of judicial communication to be the same for all respondents. This is because the new style of judicial communication in the post-reform era widely adopts online communication, particularly the use of social media to disseminate information. For this reason, frequent Internet users are likely to have more exposure to judicial communication than those who rarely or do not use social media.

In addition to these variables of interest, I include a number of demographic controls: gender, college education, political party, age group, and political engagement. Male and College Degree are dichotomous variables, where 1 indicates male and having a college degree or higher, respectively. Pro-KMT is a binary variable where 1 indicates whether the respondents identified themselves as supporters of the Kuomintang party,Footnote 4 and 0 otherwise. Age Group has seven levels, ranging from the oldest (above 80 years old) to the youngest (age between 18 to 30)Footnote 5.

Political Engagement is a categorical variable that measures respondents’ past voting experience. It is coded as follows: 1 for respondents who indicated they voted in the most recent election, 2 for those who reported they did not vote, and 3 for those who had not yet reached the voting age of 20 during the most recent election. Additionally, I include another control variable that captures respondents’ trust in the legislature. This variable is based on a question asking respondents to indicate their level of trust in this political institution. It is coded on a scale from 1 to 4, with higher values indicating greater trust in the legislature.

Identification strategy

I identify the effect of judicial communication on judicial trust with a difference-in-differences design that uses the fact that exposure to the new style of judicial communication varied by time and respondents’ digital usage habits. The first source of variation, the year of survey taking, determines who was exposed to judicial communication. The second source of variation comes from the respondents’ Internet and social media usage habits. Frequent digital users are more likely to be exposed to extensive judicial communication. Using this variation, I estimate the change in judicial trust by different Internet usage groups before and after judicial reform.

Since the empirical distribution of pretreatment confounders between the treated and control observations is often unbalanced, rendering model dependence in the statistical estimation of causal effects (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Imai, King and Stuart2007). To improve causal inference in observational data, scholars have increasingly used matching methods for preprocessing data to improve the similarity between the treated and comparison groups (Chabé-Ferret Reference Chabé-Ferret2015). In line with this, I use Mahalanobis distance matching to pair the treated units with the closest control units based on respondents’ key individual attributes (gender, age, education, and partisanship), with replacement. This adjustment with matching creates a dataset where individuals in treated and control groups have a similar chance of receiving the treatment based on the key covariates.

Results

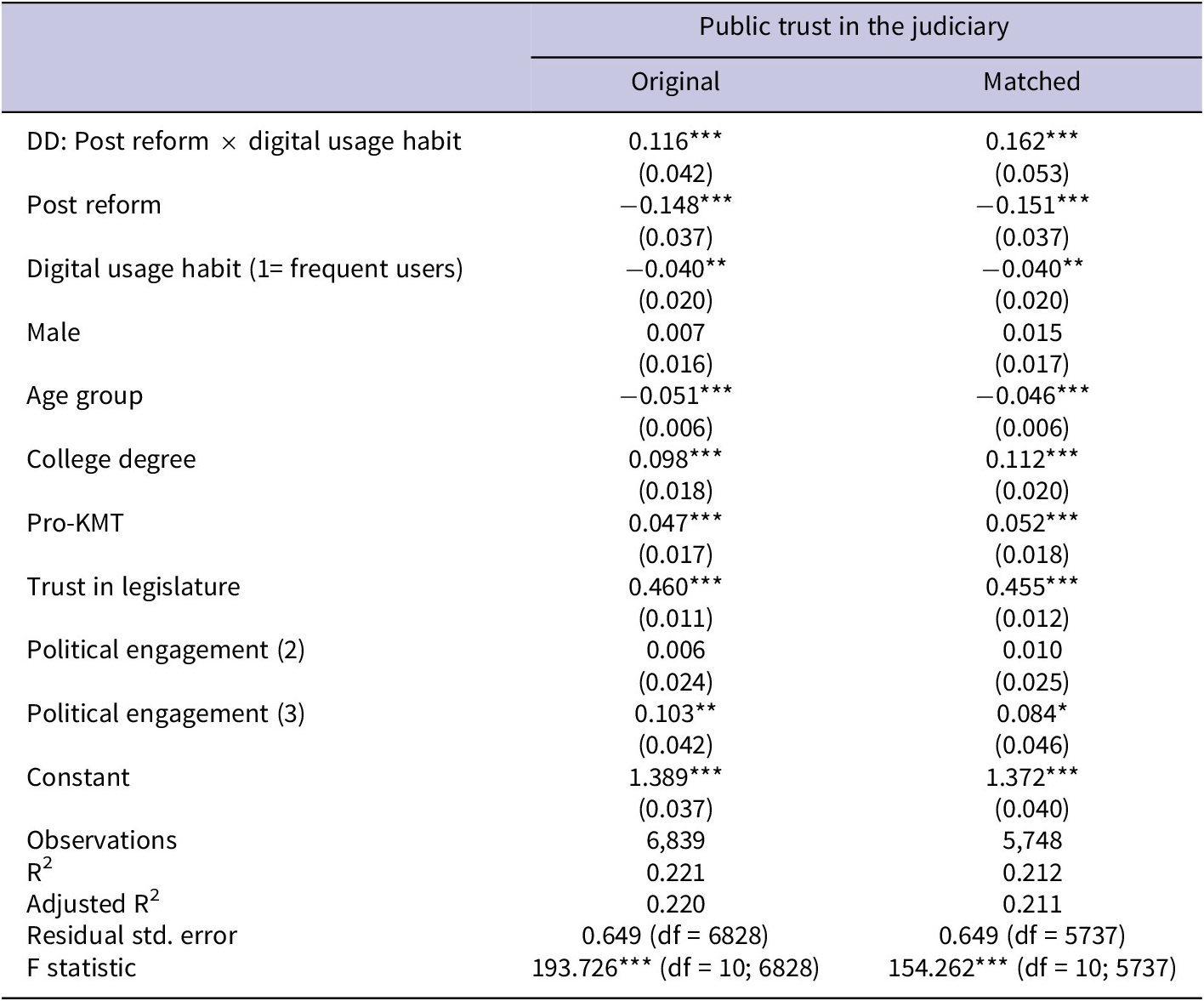

Table 3 presents the results from my analysis using the original and matched datasets. The main estimate of interest is the coefficient on the interaction term between Internet usage habit (Digital Usage Habits) and the respondents who experienced the new style of judicial communication (Post-Reform). This is shown in the first row of Table 3.

Table 3. Effect of Judicial Communication on Trust Toward Courts

Note: * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01

As predicted, the coefficient on the interaction term is positive and statistically significant in both models. The results based on the original dataset suggest that exposure to the new style of judicial communication results in a 0.11 point increase in public trust in the judiciary. This increase amounts to

![]() $ 15\% $

of standard deviation; or put differently, it increases by

$ 15\% $

of standard deviation; or put differently, it increases by

![]() $ 2.9\% $

in terms of the answer scale on the dependent variable. The results are similar for the matched data set. The coefficient for the interaction term remains positive and statistically significant. Exposure to and experience of the new style of judicial communication increases public trust in the judiciary by 0.16 points. This amounts to an increase of

$ 2.9\% $

in terms of the answer scale on the dependent variable. The results are similar for the matched data set. The coefficient for the interaction term remains positive and statistically significant. Exposure to and experience of the new style of judicial communication increases public trust in the judiciary by 0.16 points. This amounts to an increase of

![]() $ 22\% $

of a standard deviation, or by

$ 22\% $

of a standard deviation, or by

![]() $ 4\% $

on the answer scale for Judicial Trust.

$ 4\% $

on the answer scale for Judicial Trust.

The substantive magnitude of the effect of judicial communication is noteworthy, given that public attitudes toward the judiciary reflect a form of institutional trust that is not easily cultivated. Generalized trust in institutions is referred to as the diffuse support for political institutions, and fostering such support entails a cumulative process known as the “rally tally,” which requires the acquisition of experience over time (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse1995). For example, scholars find that older courts associate with a higher degree of diffuse support as older courts accumulate satisfaction over time (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998). In this vein, my findings regarding the positive effect of active judicial communication on bolstering judicial trust are encouraging, as they suggest a potential for continued growth in judicial trust as the public continues to be exposed to judicial communication over time.

To further validate my argument, I use a placebo test. To argue that the new judicial communication strategy increased public trust in the judiciary, there should be no significant difference between frequent and infrequent digital users before the Judicial Yuan adopted active communication through social media in 2019. To check this possibility, I plot the coefficients on the treatment term Post-Reform

![]() $ \times $

Digital Usage Habit based on the model used in Table 3 by shifting the introduction year of Judicial Yuan’s online platforms. To do so, I consider only individuals from survey years before 2019 and assign a hypothetical treatment as if the judicial communication had been adopted in the year

$ \times $

Digital Usage Habit based on the model used in Table 3 by shifting the introduction year of Judicial Yuan’s online platforms. To do so, I consider only individuals from survey years before 2019 and assign a hypothetical treatment as if the judicial communication had been adopted in the year

![]() $ t $

rather than in 2019, where the year

$ t $

rather than in 2019, where the year

![]() $ t $

is between 2006 and 2018. No respondents were actually exposed to the new style of judicial communication under the placebo reform years, as the Judicial Yuan did not set up online platforms until after 2019; hence, we should observe no significant judicial communication effect. I also assign the placebo adoption year after 2019 to show how the treatment effect changes over time. Figure 2 shows that the judicial communication effect only appears in 2021, not before. The estimated coefficients before 2019 are not statistically different from zero, indicating no significant communication effect before the Judicial Yuan adopted active communication. After introducing the new communication style, the differences in attitudes toward judicial trust between the two groups become significant.

$ t $

is between 2006 and 2018. No respondents were actually exposed to the new style of judicial communication under the placebo reform years, as the Judicial Yuan did not set up online platforms until after 2019; hence, we should observe no significant judicial communication effect. I also assign the placebo adoption year after 2019 to show how the treatment effect changes over time. Figure 2 shows that the judicial communication effect only appears in 2021, not before. The estimated coefficients before 2019 are not statistically different from zero, indicating no significant communication effect before the Judicial Yuan adopted active communication. After introducing the new communication style, the differences in attitudes toward judicial trust between the two groups become significant.

Figure 2. Placebo Judicial Reform Shows the Effect of New Style Judicial Communication Using Hypothetical Years of Adoption.

In sum, the findings suggest that adopting public-oriented communication helps improve public trust in the judiciary. Given that the new style of judicial communication heavily focuses on social media, this effect is especially pronounced among frequent Internet users.

Conclusion

Research on judicial communication suggests judges are incentivized to communicate with the public to gain public support. While these studies consider that judges value public perception (Baum Reference Baum2009) and that judicial communication positively influences public attitudes, few studies examine judges’ motivations, nor do they examine the effects of communication beyond experimental contexts. My study contributes to existing research by employing valuable elite interviews and an empirical design that allows me to examine judges’ motivations for engaging in public outreach and the effect of judicial communication on public attitudes toward the judiciary. Furthermore, this paper expands its scope by examining the strategy of judicial communication. A communication strategy focused on bridging the gap between the public and the judiciary – mainly through simplified legal language and greater information accessibility – can enhance public understanding and foster a more favorable perception of the judiciary.

Drawing on a unique judicial reform in Taiwan that promotes public-oriented communication, I examine why the judiciary embraces this approach and how such communication influences public attitude. My findings reveal that individual judges are motivated by their frustration with low public trust and the concern of misinformation in the media environment. Importantly, I find that judges began to communicate when the judiciary faced attacks, such as during the “Dinosaur Judges” period or the year before the National Conference when judges frequently encountered negative attacks in the media. During these times, judges felt misunderstood and recognized that maintaining silence alone was insufficient for preserving judicial reputation, prompting them to initiate active communication efforts. Similarly, the judiciary’s adoption of communication as a national policy was driven by restoring its reputation, and notably, many of the communication strategies were directly inspired by individual judges’ initiatives.

The communication strategy adopted by the Judicial Yuan focuses on simplifying legal language and reconnecting the public with the judiciary. My findings show that this approach enhances public trust in the judiciary. Individuals who are more likely to be exposed to this new form of judicial communication, particularly frequent digital users, demonstrate increased trust in the institution. This finding suggests that making judicial communication more understandable and accessible plays a key role in rebuilding trust between the judiciary and the public.

These findings have important implications for courts in countries seeking to build judicial trust. While the need to reacquaint the public with the judiciary may be unique to transitional democracies where authoritarian legacies often distance judges from the public, the need to simplify legal information is likely universal. In many countries, the use of complicated legal language presents a significant barrier for the average citizen to comprehend, and this gap can easily lead to misinterpretation. This is particularly evident when national high courts deliver controversial decisions, as criticisms may follow, some of which may stem from misinterpretation.

Acknowledgments

I thank all my interviewees willing to share their valuable experiences with me. I also thank Brad Epperly, Tobias Heinrich, Jessica Schoenherr, and the Law and Court Junior Women Writing Group participants for providing feedback on my writing at different stages. I am grateful to the JLC team and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback.

Data availability statement

All replication materials are available on the Journal of Law and Courts Dataverse archive.

Financial support

No funding was received for this project.

Appendices

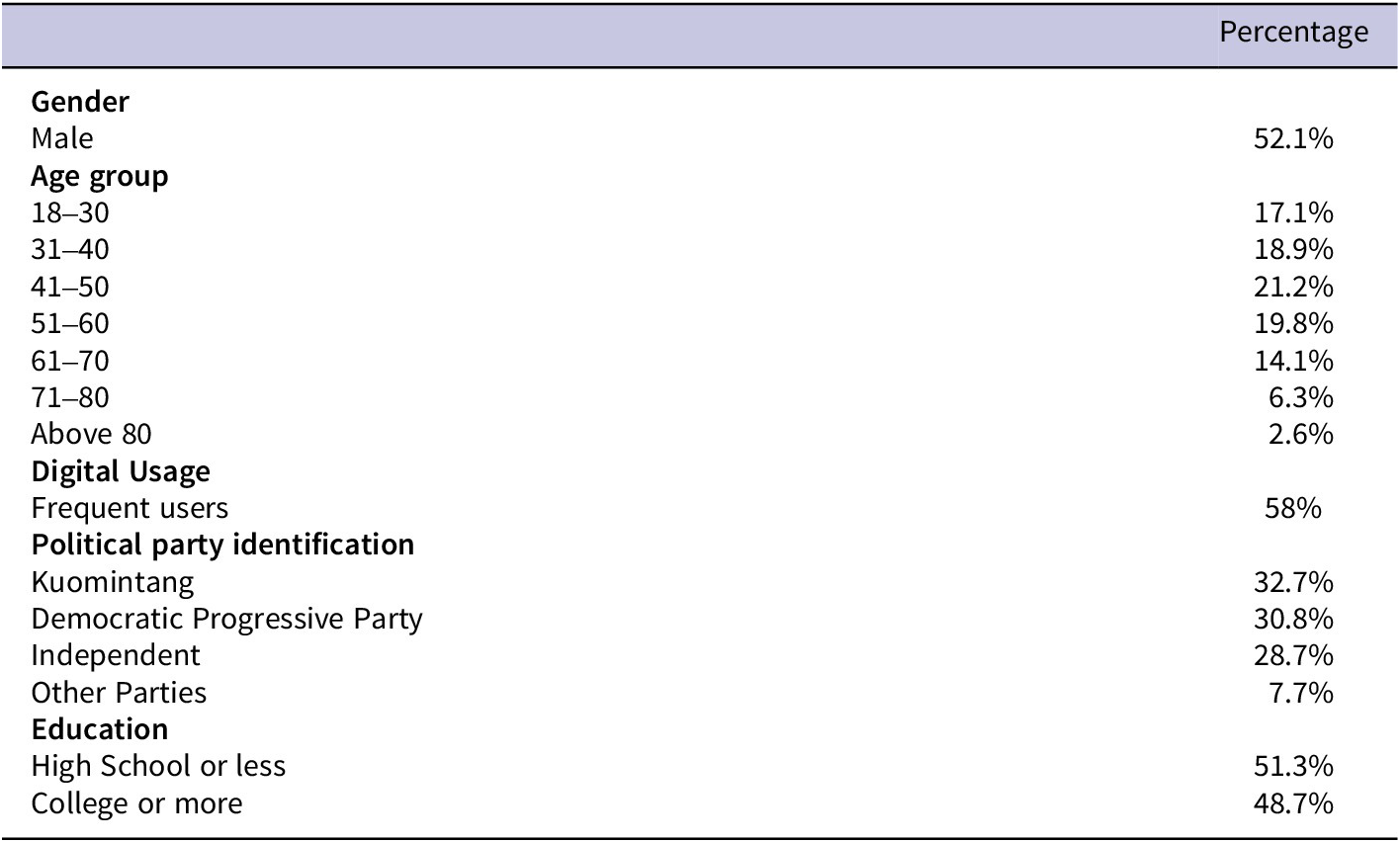

Descriptive statistics

Table 4 Sample Characteristics

Note: Descriptive statistics based on respondents with complete data on all variables.

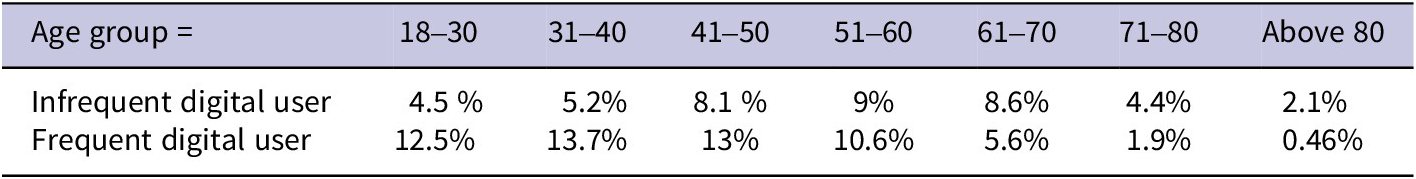

Table 5. Age Group | Digital Usage

Notes: In this table, the rows indicate digital usage, with 0 for infrequent users and 1 for frequent users, while the columns represent different age groups, from the youngest group (aged 18 to 30) to the oldest group (aged 80 and above). These percentages are calculated by dividing the count in each cell by the total number of observations and multiplying by 100. The general pattern shows that younger people are more likely to use social media. However, there is a more balanced mix for the middle-aged to senior groups. For example, in the 51–60 age group, 9% are infrequent users compared to 10.6% who are frequent users.